1. Introduction

Supercooled liquid water (SLW)—liquid water droplets persisting at temperatures below 0 °C—is a critical component of mixed-phase clouds. Its formation and persistence are governed by complex interactions among temperature, atmospheric dynamics, and aerosol content [

1], leading to significant spatiotemporal heterogeneity. SLW plays a pivotal role in precipitation processes and the Earth’s radiative balance, yet its representation remains a major source of uncertainty in climate models. Furthermore, the concentration and distribution of SLW directly influence aviation safety through aircraft icing and determine the efficacy of weather modification operations, such as cloud seeding and hail suppression [

2]. Accurate identification and quantitative retrieval of SLW’s microphysical properties and distribution are therefore central to advancing both atmospheric science and applied meteorology.

Currently, observations of SLW primarily rely on three approaches: satellite remote sensing, airborne measurements, and ground-based remote sensing, each offering distinct advantages and limitations in terms of spatial coverage, temporal continuity, and accuracy. Satellite remote sensing, with its wide-area coverage, is well-suited for identifying the spatial distribution of SLW over large scales [

3]. Roskovensky et al. [

4] utilized Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) cloud products in combination with a cloud vertical parameterization model to extrapolate two-dimensional remote sensing observations into cloud vertical structure information, thereby retrieving the global-scale distribution of SLW. However, this method is highly dependent on assumptions in cloud physical parameterization and is limited by MODIS’s relatively low temporal resolution (typically only two overpasses per day), resulting in considerable uncertainties in SLW estimates. In recent years, geostationary satellites, with their high temporal resolution (up to 10-min intervals), have provided new opportunities for dynamic monitoring of SLW. Xu et al. [

5] developed an SLW identification algorithm applicable to East Asia based on multispectral observations from the Fengyun-4A satellite, combining cloud-top brightness temperature, RGB true-color composite imagery, and K-means clustering algorithms, with validation using airborne observations and CALIPSO vertical profile data. Wang et al. [

6,

7] focused on differences in microphysical properties between liquid water clouds and ice clouds, developing an SLW identification method based on the Himawari-8/9 Advanced Himawari Imager (AHI). They exploited the sensitivity of cloud effective radius (CER) to cloud particle phase evolution stages and incorporated cloud phase prior information, which significantly enhances the capability to identify mixed-phase clouds. They further leveraged the differential radiative responses of liquid water and ice particles in visible and shortwave infrared bands to retrieve the liquid water fraction in mixed-phase clouds, with calibration using CALIPSO cloud products, substantially improving the accuracy of phase partitioning. Nevertheless, the aforementioned satellite remote sensing approaches primarily rely on cloud-top radiative information and cannot penetrate cloud bodies to obtain detailed information about their internal vertical structure and microphysical processes. Consequently, they are unable to directly provide the occurrence frequency or temporal evolution characteristics of SLW at different height levels.

In contrast, airborne in situ observations can directly measure key microphysical parameters such as particle size distributions and liquid water content (LWC), representing the most accurate and direct approach for studying SLW. This method achieves direct measurements of key cloud microphysical parameters by deploying various cloud microphysical probes on aircraft platforms. The detection typically utilizes a Fast Cloud Droplet Probe (FCDP-100) to measure the size distribution of small cloud droplets in the 1–50 μm diameter range, combined with a Cloud Imaging Probe (CIP) and a High Volume Precipitation Spectrometer (HVPS-3) to obtain size and concentration information for ice crystals and large droplets above 50 μm, thereby constructing complete cloud particle size distributions. By integrating the particle size distribution and incorporating environmental temperature, humidity, and wind fields, LWC and ice water content (IWC) can be retrieved. In airborne in situ observations, there is no single “ground-truth” instrument for the identification of SLW; instead, SLW detection generally relies on a combination of multiple observational constraints. Among these, icing detectors such as the Rosemount Icing Detector (RICE) provide a direct indication of the presence of supercooled liquid water through measurements of icing rate [

8]. In addition, based on integrated analyses of multiple aircraft campaigns, previous studies have proposed and demonstrated the feasibility of identifying SLW using cloud particle number concentration in conjunction with ambient temperature. These results indicate that, in the absence of imaging probes or icing detectors, cloud particle number concentration and temperature characteristics can provide useful constraints for SLW identification to a certain extent [

9]. In recent years, multiple airborne observation campaigns have been conducted over North China, accumulating abundant in situ cloud microphysical observation data and revealing the cloud physical characteristics of SLW in this region [

10,

11,

12]. Furthermore, regarding airborne remote sensing observations of supercooled water, Wang et al. [

13] developed a supercooled liquid water path (SLWP) retrieval algorithm based on a backpropagation neural network, which, combined with airborne microwave radiometer (GVR) observations, enabled real-time estimation of SLWP during flight operations, achieving a root mean square error of only 0.2 g m

−2 under low-SLWP conditions. Overall, airborne observations can accurately resolve the coexistence of liquid droplets and ice crystals within clouds and their precise microphysical properties, providing high-precision data for in-depth understanding of SLW. However, limited by high flight costs, short operational periods, and restricted spatial coverage, airborne observations are mostly confined to case studies or short-term campaigns and are unable to achieve long-term continuous monitoring. Consequently, they exhibit significant deficiencies in regional climate statistics, interannual variability analysis, and large-scale long-term distribution studies.

Ground-based observation techniques, owing to their long-term continuity, high vertical resolution, and low maintenance costs, play an important role in the quantitative retrieval of SLW, studies of microphysical characteristics, and climate feature analysis. Sassen [

14], utilizing polarization lidar and microwave radiometer, conducted a preliminary climatological analysis of SLW over southern Utah, revealing that SLW cloud base heights exhibited a bimodal distribution, corresponding to convective clouds (approximately 3.0 km above sea level) and frontal stratiform clouds (approximately 4.5 km above sea level), respectively. Osburn et al. [

15,

16], based on three years of microwave radiometer observations in the Snowy Mountains region of Australia, combined with MODIS products and WRF numerical simulations, revealed the occurrence frequency of SLW, total liquid water amount, and their relationships with weather systems. Hu et al. [

17] proposed a novel algorithm for identifying supercooled water in mixed-phase clouds based on the multi-spectral peak characteristics in cloud radar power spectra, combined with radar reflectivity factor and mean Doppler velocity. Through retrieval analyses of two stratocumulus cases in spring over northeastern China, the results showed that supercooled water in stratocumulus clouds over the northeastern region is widespread, with

LWC of approximately 0.1 ± 0.05 g/m

3 and particle sizes not exceeding 10 µm.

In summary, although satellite remote sensing provides large-scale spatial coverage and airborne observations can provide high-precision in situ microphysical information, satellite image sensors cannot directly resolve vertical SLW structure [

18], and airborne observations are mostly limited to case studies, making them insufficient to support climatological analysis. In contrast, ground-based remote sensing, with its advantages of high temporal resolution, high vertical resolution, and long-term continuous operation, plays an irreplaceable role in revealing the vertical structure, occurrence frequency, seasonal variability, and microphysical properties of SLW. However, a comprehensive understanding of its vertical structure has been hampered by a lack of sustained, vertically resolved observations over the North China Plain. Therefore, this study, based on long-term continuous ground-based cloud radar, microwave radiometer and cloud ceilometer observation data from North China, combined with fuzzy logic phase identification and LWC retrieval algorithms, systematically analyzes the spatiotemporal distribution characteristics, seasonal variation patterns, and microphysical structure of SLW in this region. The research aims to fill current observational gaps, enhance understanding of cold cloud physical processes in North China, and provide robust data support and theoretical foundation for the scientific design of weather modification operations, optimization of cloud microphysical parameterization schemes in numerical models, and assessment of regional climate effects. The organization of this paper is as follows:

Section 2 introduces the observational data sources and retrieval methods;

Section 3 analyzes the cloud macroscopic characteristics and spatiotemporal distribution of SLW in North China and investigates the microphysical properties of SLW;

Section 4 summarizes the main conclusions and discussion.

2. Data and Methods

2.1. Observation Site and Instruments

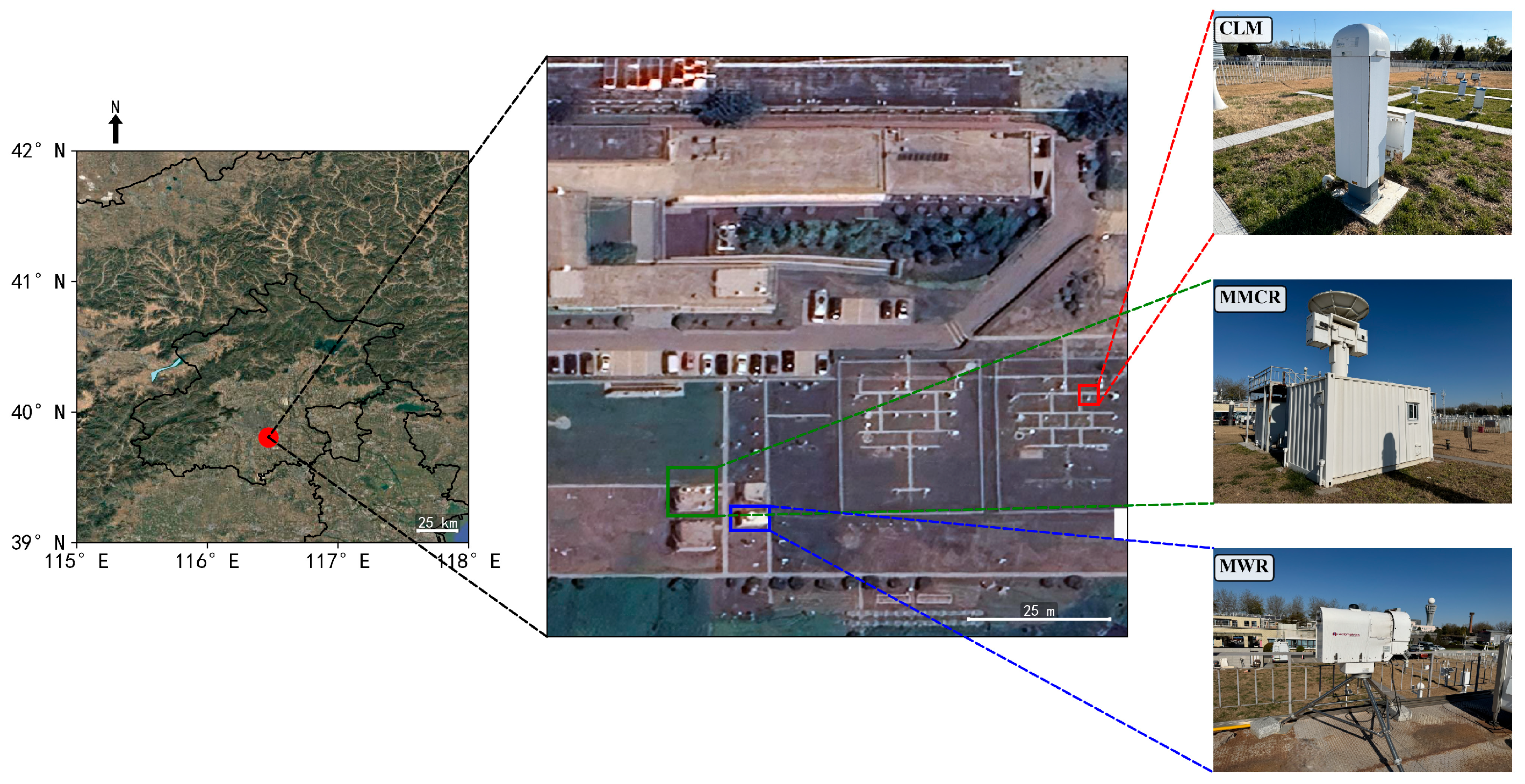

This study utilizes ground-based active and passive remote sensing observation data from the Nanjiao Observatory of the Beijing Meteorological Bureau (39.81°N, 116.47°E, elevation 32.8 m) (

Figure 1). The site is located in the North China Plain and belongs to a temperate monsoon climate zone, characterized by significant seasonal variations in cloud systems, including frequent stratiform and convective cloud systems [

19], making it a representative region for studying cloud microphysical properties in North China.

The data used in this study are from synchronized and collocated observations by a millimeter-wave cloud radar, microwave radiometer, laser ceilometer, and L-band radiosonde system at this site, covering the entire year of 2022 (

Figure 1, middle).

The Ka-band millimeter-wave cloud radar (MMCR; 35 GHz, model HT101; Xi’an Huateng Microwave Co., Ltd. (HTMW), Xi’an, China) is an all-solid-state pulsed Doppler radar that provides Z, Vd, and Wd (Doppler velocity spectrum width) parameters. Operating in vertically pointing mode with a range resolution of 30 m, maximum detection height of 15 km, and temporal resolution of 1 min, it exhibits high detection sensitivity to cloud particles and serves as the primary data source for analyzing cloud vertical structure and retrieving microphysical quantities in this study. The minimum detectable reflectivity factor of the MMCR is −40 dBZ, with a maximum detectable reflectivity of 30 dBZ. The microwave radiometer data (MWR; RPG-HATPRO; RPG Radiometer Physics GmbH, Meckenheim, Germany; 22.2 GHz and 60 GHz) provide products including atmospheric temperature profiles and liquid water path (LWP), with a temporal resolution of 2 min. The vertical resolution is 50 m at 0–0.5 km, 100 m at 0.5–2 km, and 250 m at 2–10 km, with a maximum height of 10 km. This study utilizes the temperature profiles from its Level 2 products to assist in cloud phase determination and combines LWP to constrain the LWC retrieval process. The laser ceilometer (CLM; CL51; Vaisala Oyj, Helsinki, Finland; operating wavelength 910 nm), with a vertical resolution of approximately 5 m, temporal resolution of 1 min, and maximum detection height of approximately 15 km, identifies cloud base height derived from backscatter signals, providing important information for cloud base height determination. Additionally, this study incorporates L-band radiosonde data. The site conducts three routine radiosonde observations daily (at 08:00, 12:00, and 20:00 Beijing Time), continuously measuring meteorological parameters including atmospheric temperature, relative humidity, pressure, wind speed, and wind direction. The temperature and humidity information provided by radiosonde profiles not only ensures vertical continuity and physical consistency of the temperature field during the cloud phase identification process but can also be used to validate the reliability of cloud radar retrieval results.

2.2. Data Preprocessing and Quality Control

To ensure the consistency and reliability of multi-source observation data, this study conducted systematic spatiotemporal matching and quality control processing on millimeter-wave cloud radar, microwave radiometer, and laser ceilometer data prior to retrieval analysis. Due to differences in temporal sampling frequencies among different observation instruments, unified temporal resampling is required. This study employed the nearest-neighbor interpolation method to temporally align the original data with 1-min temporal resolution from the millimeter-wave cloud radar and laser ceilometer, along with the 2-min temporal resolution data from the microwave radiometer, to a uniform temporal resolution of 2 min. All observation instruments are deployed at the same observation site with horizontal separations less than 100 m, which are effectively collocated; thus, spatial mismatch is negligible for this analysis on cloud vertical structure analysis. To achieve vertical structure matching of multi-source data with cloud radar observations, the vertical resolution of all profile data was uniformly resampled to 30 m (i.e., the range gate length of the cloud radar). The original vertical resolution of temperature profile retrieved from the MWR varies with height (approximately 50–250 m), and linear interpolation was applied to resample them to 30 m intervals, ensuring alignment with cloud radar data on the vertical grid. Additionally, because the MWR temperature and humidity profile products extend only to approximately 10 km, while the cloud profile retrievals in this study reach up to 12 km, radiosonde observations nearest in time were incorporated in the 10–12 km layer to ensure the completeness of the temperature field.

To enhance the reliability of MWR retrieval products, quality control procedures were applied. The temperature and humidity profile products used in this study are derived from Fu et al. [

20], which employs a conditional generative adversarial network to achieve high-precision atmospheric temperature profile retrieval, maintaining high accuracy under both clear-sky and cloudy conditions. Quality control for temperature data includes temporal smoothing with an 8-min filtering window to suppress high-frequency random noise and improve retrieval stability [

21]. Additionally, outliers in the LWP product were removed, including positive LWP values under clear-sky conditions and extreme values exceeding 3000 g m

−2 under cloudy conditions, to ensure the reasonableness of LWP retrievals.

MMCR data require noise suppression, precipitation echo identification, boundary layer clear-air clutter removal, and attenuation correction prior to use, in order to enhance the accuracy and physical consistency of cloud signals. For noise removal, first, −41 dBZ was set as the valid echo threshold, and signals below this value were considered noise and removed. Second, image morphological processing methods were introduced to perform erosion operations on the reflectivity factor field, employing rectangular convolution kernels to conduct convolution operations on neighboring grid cells to enhance the spatial continuity of echoes. Subsequently, small connected component removal was executed, where connected regions containing fewer than 30 pixels were identified as isolated noise and set to invalid values. This processing effectively improved the spatial consistency of cloud echoes. Following noise removal, precipitation echo identification and removal were conducted. When continuous echo signals appeared in 10 range gates above the radar blind zone (above 150 m), with a maximum reflectivity factor greater than −5 dBZ and a mean radial velocity less than 0, the profile was identified as a precipitation echo.

Under non-precipitating conditions, MMCR can detect clear-air echoes within the atmospheric boundary layer produced by turbulence, insects, birds, or other biological scatterers, with intensities comparable to weak cloud signals, which can easily interfere with cloud identification. Previous studies have primarily relied on cloud radar data with polarimetric observation capabilities, utilizing physical feature discrimination or spectral feature classification methods for the identification and removal of clear-air echoes [

22,

23]. However, the radar data used in this study lack polarimetric information such as linear depolarization ratio, making it difficult to apply the aforementioned methods. Therefore, this study adopts an empirical clear-air echo removal scheme based on joint observations from cloud radar and ceilometer. Due to the shorter operating wavelength of the laser ceilometer (910 nm), it is more sensitive to small cloud particles, and its cloud base detection results exhibit high reliability under low-cloud conditions. Signals located below the ceilometer-detected cloud base and appearing as continuous or strong echoes in the cloud radar are identified as clear-air echoes and removed. For attenuation correction, this study employs the gate-by-gate correction algorithm improved by Huang [

24], which is based on the empirical relationship between radar reflectivity factor

Z and attenuation coefficient k. By dividing echoes into different intervals and applying corresponding correction coefficients, attenuation correction of MMCR echoes is performed to enhance the accuracy of SLW detection and retrieval.

Following the aforementioned noise suppression, precipitation echo identification, and boundary layer clear-air clutter removal, cloud layer boundary identification and cloud mask construction were further conducted. The height at which the radar signal first appears is defined as the cloud base, and the height at which it last appears is defined as the cloud top. Since the laser ceilometer is more sensitive to small cloud particles and exhibits higher detection reliability, the ceilometer identification result is used as the standard for determining the first cloud layer base height at low levels. When multiple cloud layers exist in the same profile, if the height difference between the cloud top of adjacent layers and the cloud base of the upper layer exceeds 180 m, they are identified as multi-layer clouds; otherwise, they are considered a single-layer cloud.

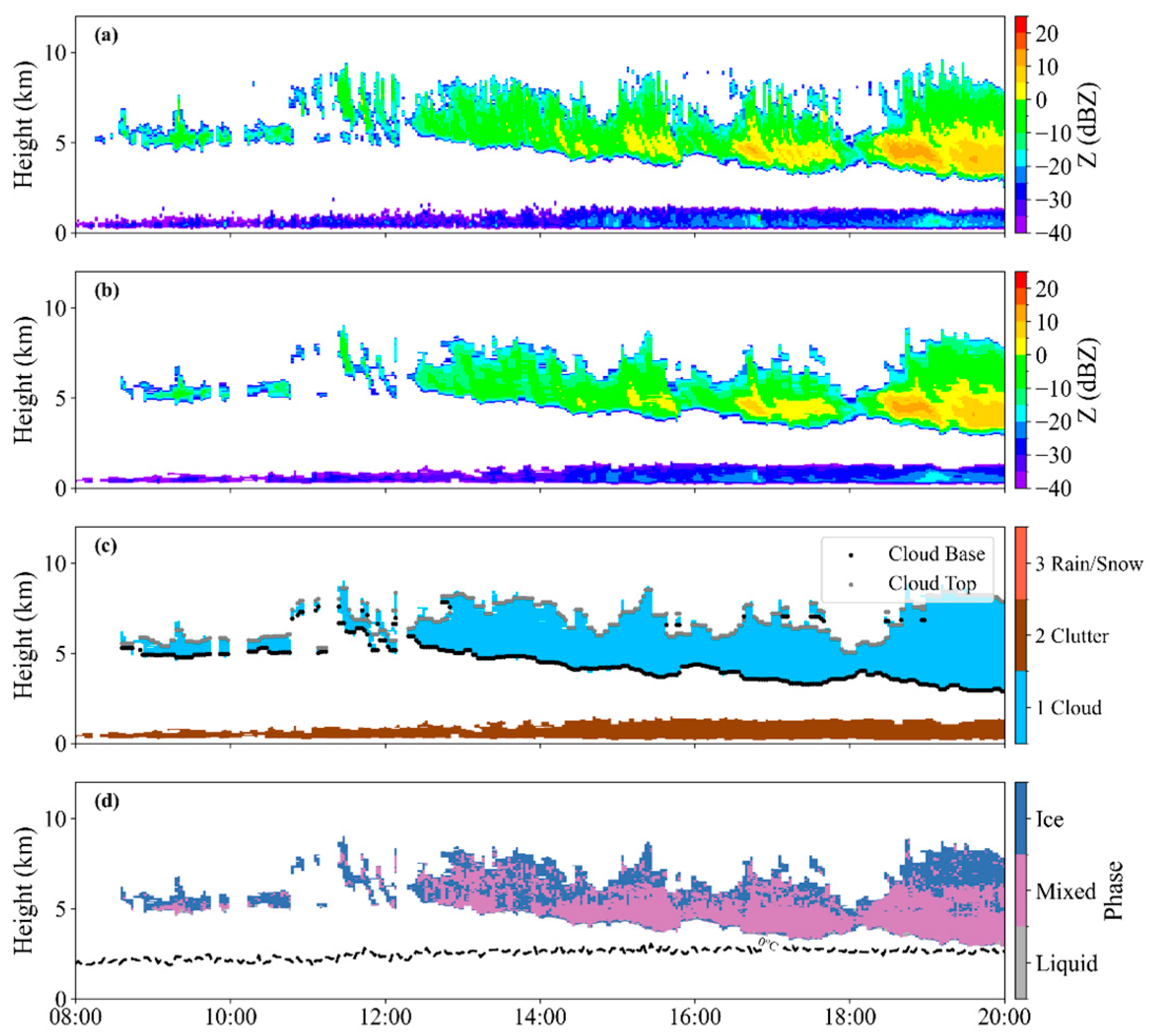

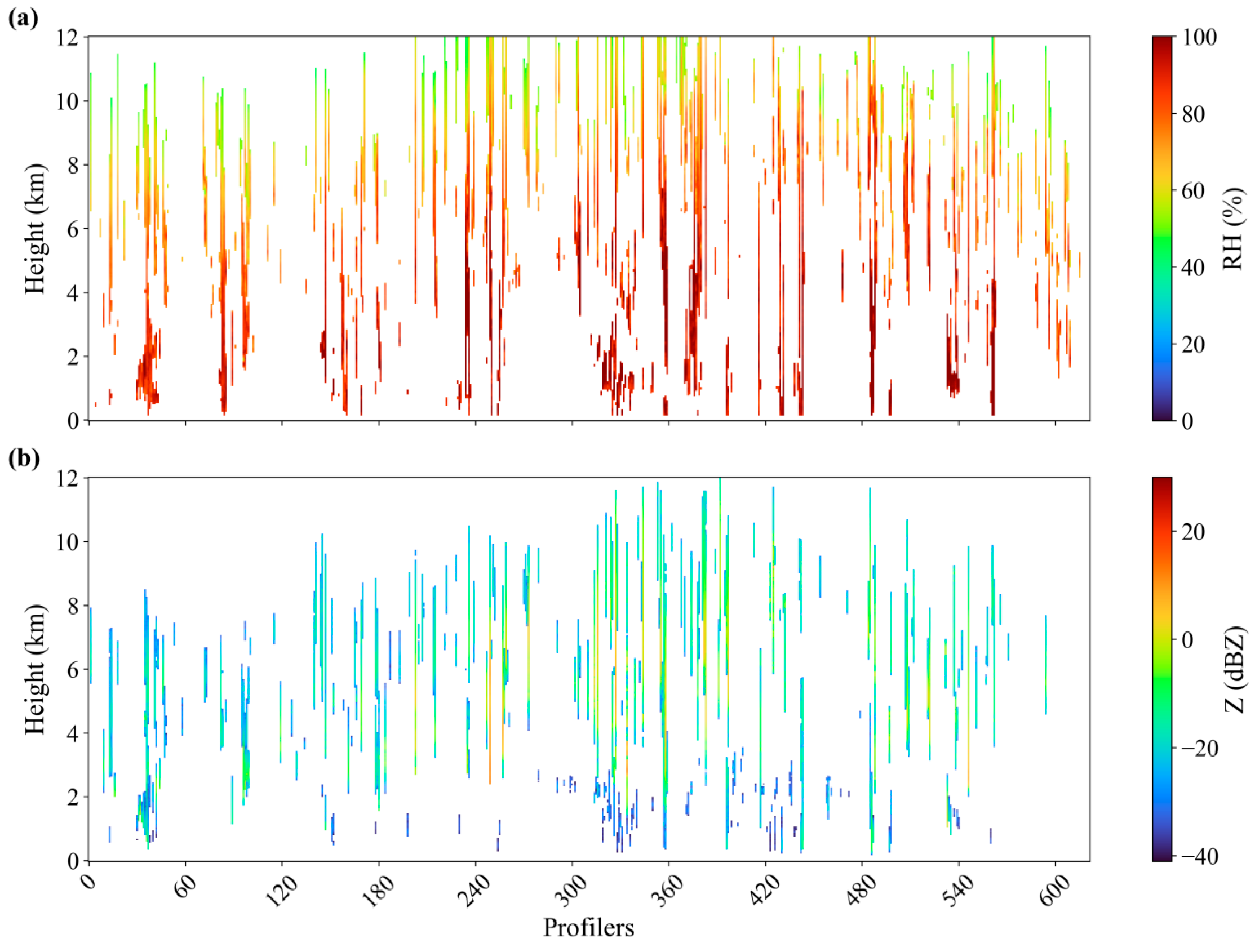

Figure 2 presents a case study of cloud radar quality control and cloud identification results from a typical event on 11 May 2022. This case demonstrates that through the complete data preprocessing procedure, the vertical structure of clouds is clearly presented, cloud boundary identification results are reasonable, and cloud signals are effectively distinguished from non-meteorological echoes, validating the feasibility and robustness of this data processing workflow.

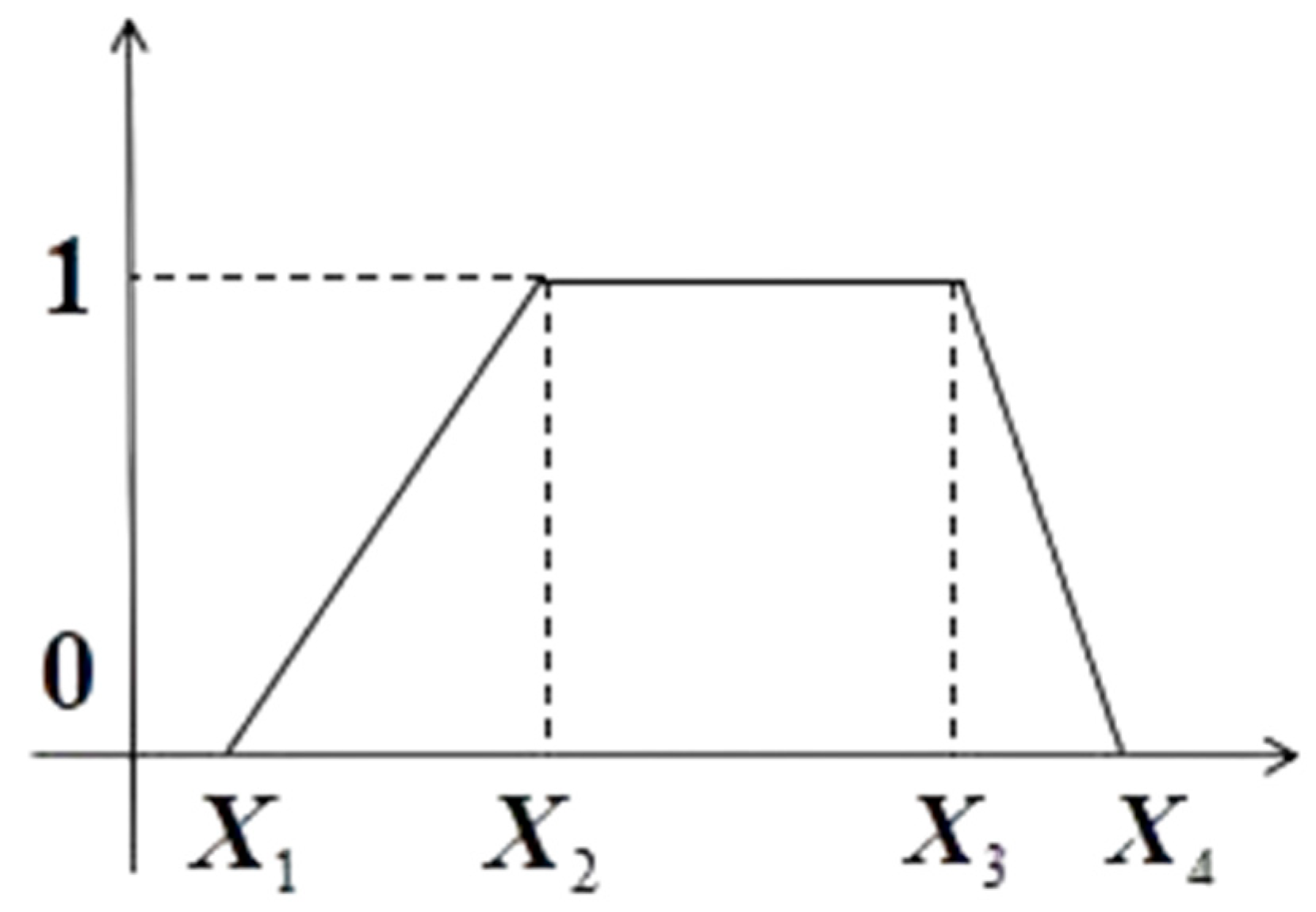

2.3. SLW Identification and Microphysics Retrieval Method

To achieve the identification of SLW in clouds and retrieve its LWC (i.e.,

LWCSLW), this study employs a fuzzy logic algorithm combined with the temperature observation from MWR to conduct SLW identification and microphysical parameter retrieval. Traditional phase identification methods based on single thresholds [

25] are inherently rigid when dealing with continuous phase transitions, and thus fuzzy logic approaches have been widely adopted for cloud particle phase identification [

26,

27]. This study selects

Z,

Vd,

Wd, and

T as input variables to construct a four-dimensional parameter space for discriminating cloud particle phase. Phase identification is divided into three categories: liquid cloud droplets, ice crystals, and mixed phase (

Figure 2d). For the distribution characteristics of each parameter under different phases, asymmetric trapezoidal membership functions are employed. The mathematical definition of the fuzzy logic algorithm and the form of membership functions are provided in

Appendix A.1. The fuzzy logic parameters used in this study are based on previous research [

28] and calibrated with local observational characteristics (

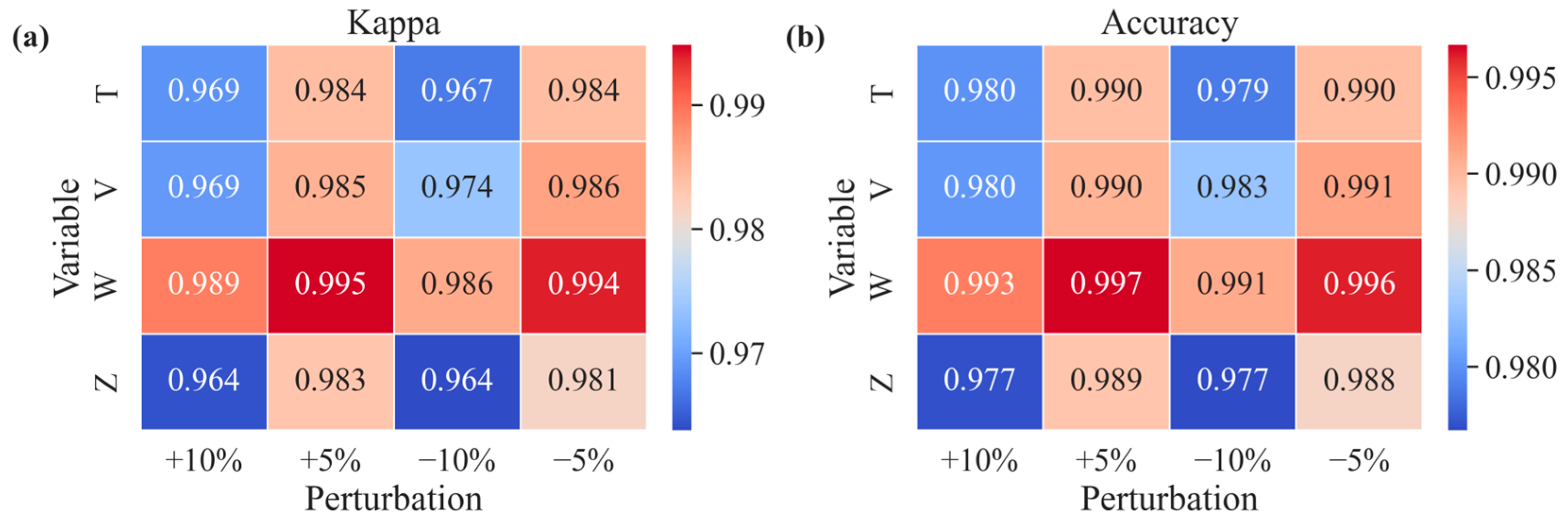

Table 1). To evaluate the impact of parameter selection on phase identification results, we conducted perturbation experiments with ±10% variations in membership function boundary parameters (

Appendix A.2). The results show that the overall classification consistency rates for liquid, mixed, and ice phases remain above 95%, with Kappa coefficients greater than 0.95, indicating that the classification results are insensitive to minor parameter variations. Additionally, since the algorithm integrates multiple independent parameters including reflectivity factor, Doppler velocity, spectrum width, and temperature, uncertainties from individual parameters are effectively suppressed, further enhancing the robustness of identification.

The identification of SLW is defined as follows: when a height level is identified as liquid cloud or mixed-phase cloud and the ambient temperature is below 0 °C, that layer is classified as SLW. For mixed-phase conditions, the relative contribution proportions of liquid water and ice phase are further calculated, using temperature as the distinguishing criterion. In specific processing, the liquid water fraction (

Liq_fraction) is defined as the contribution proportion of liquid water to the radar reflectivity factor in mixed phase, and the ice phase fraction (

Ice_fraction) is defined as the contribution proportion of ice particles to the radar reflectivity factor.

where

T is the temperature in °C, with the value range −40 °C <

T < 0 °C.

Based on the identification of liquid or mixed-phase clouds, the Supercooled liquid water content (

LWCSLW) is further retrieved. An empirical relationship exists between radar reflectivity factor

Z and LWC [

29]:

where

Zliquid is the contribution of the liquid portion to the reflectivity factor at the current layer, and

N0 represents the cloud droplet number concentration constant (units: cm

−3), set to 100 cm

−3 [

29]. Additionally, to enhance the physical consistency of retrieval results, the LWP retrieved from the MWR is introduced as an independent constraint. The MWR

LWP value is taken as the average of non-zero brightness temperature retrieval results within six minutes closest to the cloud radar observation time. The integrated value obtained by vertically integrating the retrieved LWC profile should be close to the MWR-observed LWP. The vertically integrated LWP from the retrieved

LWC profile should be comparable to the MWR-observed LWP value. However, due to factors such as assumptions about cloud droplet number concentration

N0 or differences in representativeness of cloud vertical structure, the integrated LWP (denoted as

LWPretrieved) may exhibit systematic bias from the MWR-observed LWP (denoted as

LWPMWR). Therefore, following the scaling algorithm adopted in the MICROBASE cloud product of the U.S. ARM program [

21], a linear proportional correction is applied to the originally retrieved LWC profile.

where

, and the integration height

H is the cloud top height. This adjustment ensures that the finally retrieved LWC profile is consistent with the independently observed LWP in the sense of vertical integration, enhancing the reliability and energy closure of the retrieval product.

4. Conclusions and Perspectives

Based on the all-year round comprehensive analysis of synergistic ground-based observations in Beijing, this study develops an integrated retrieval framework to identify supercooled liquid water (SLW) layers and quantify their microphysical properties. The main conclusions are summarized as follows.

Our integrated retrieval framework includes cloud boundary detection and SLW retrieval algorithm. The cloud detection algorithm shows good consistency with radiosonde observations. Retrieved microphysical properties of SLW agree well with aircraft in situ measurements reported in the literature, demonstrating the robustness of the combined MMCR–MWR retrieval framework.

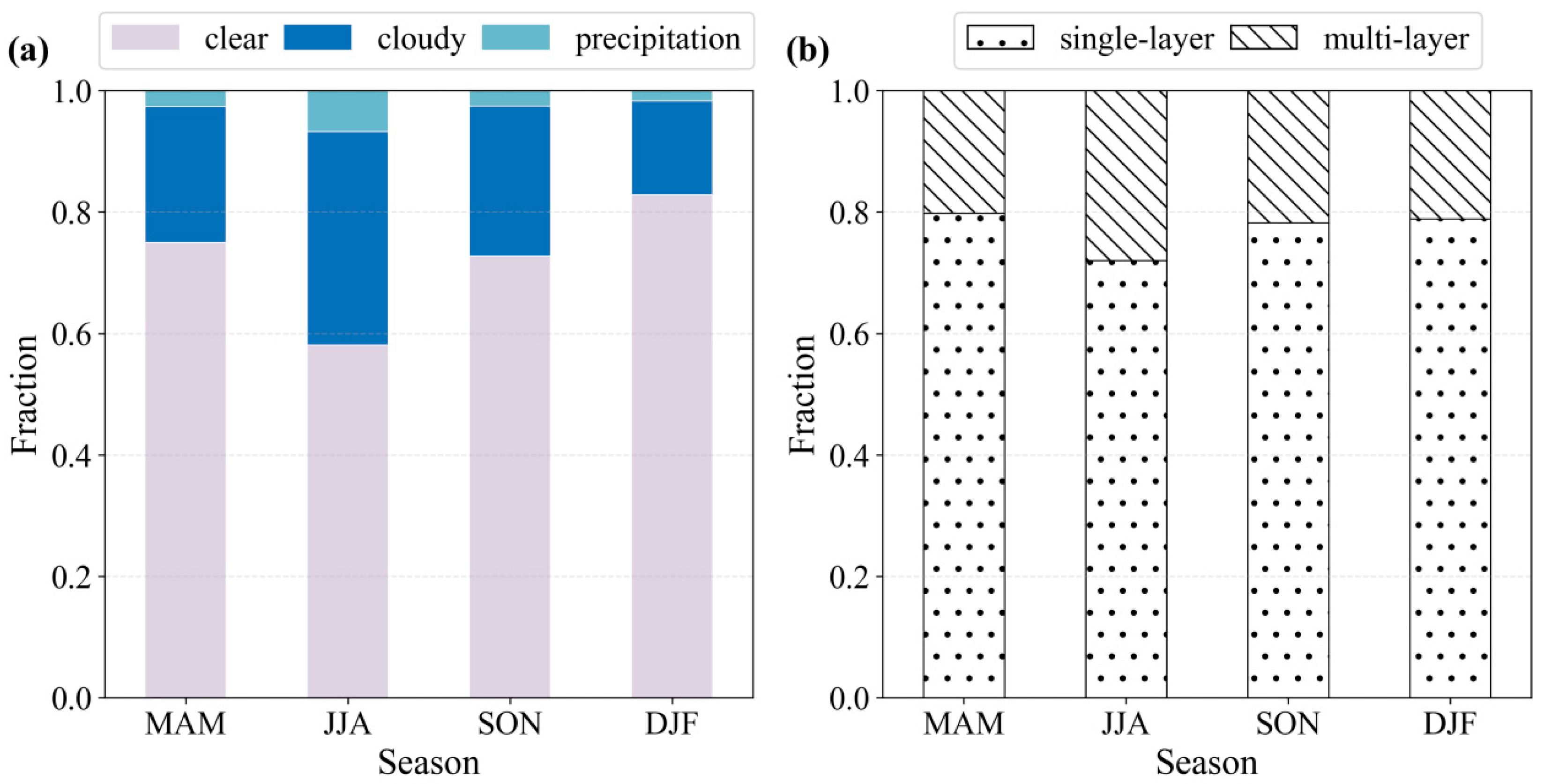

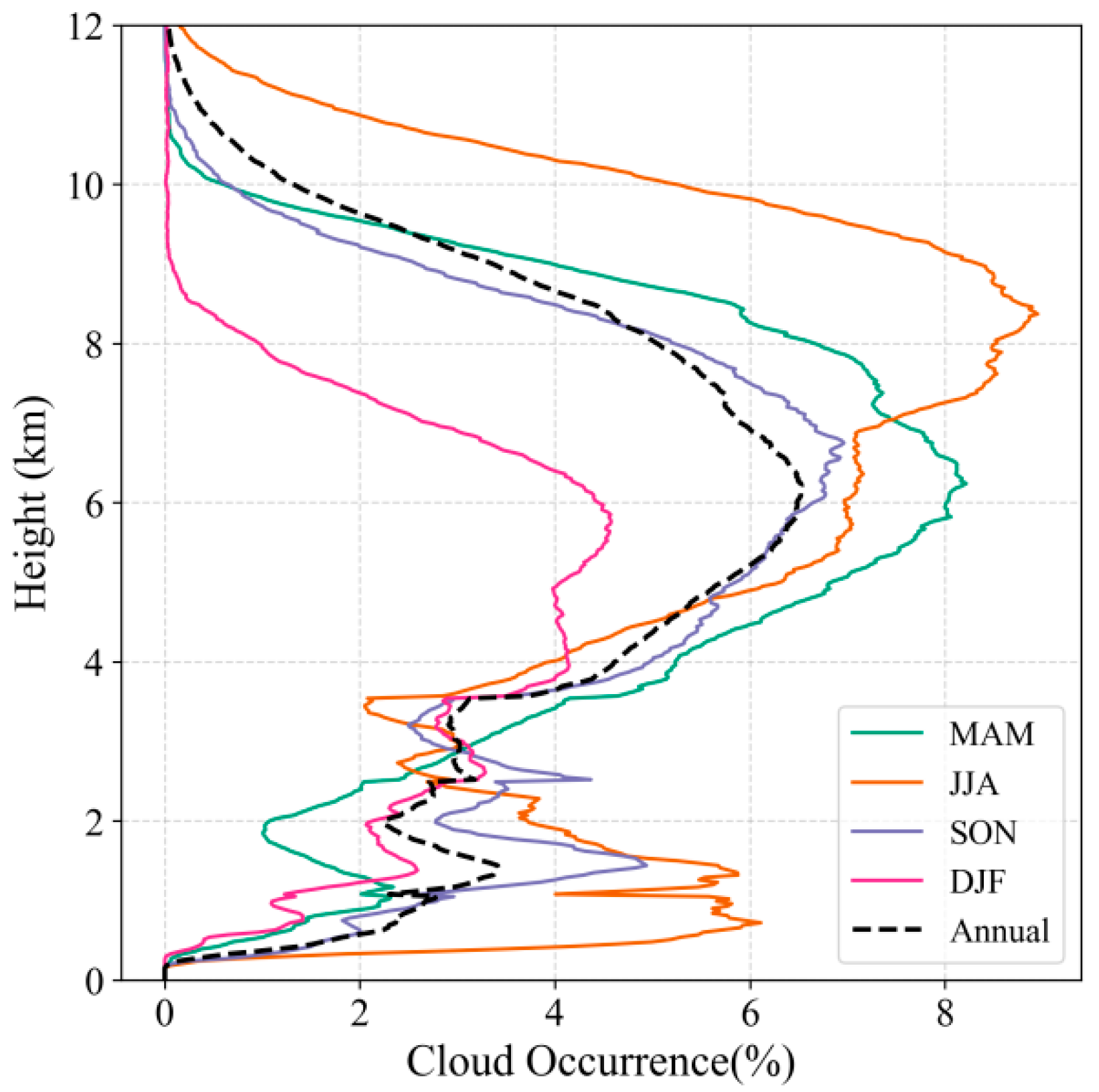

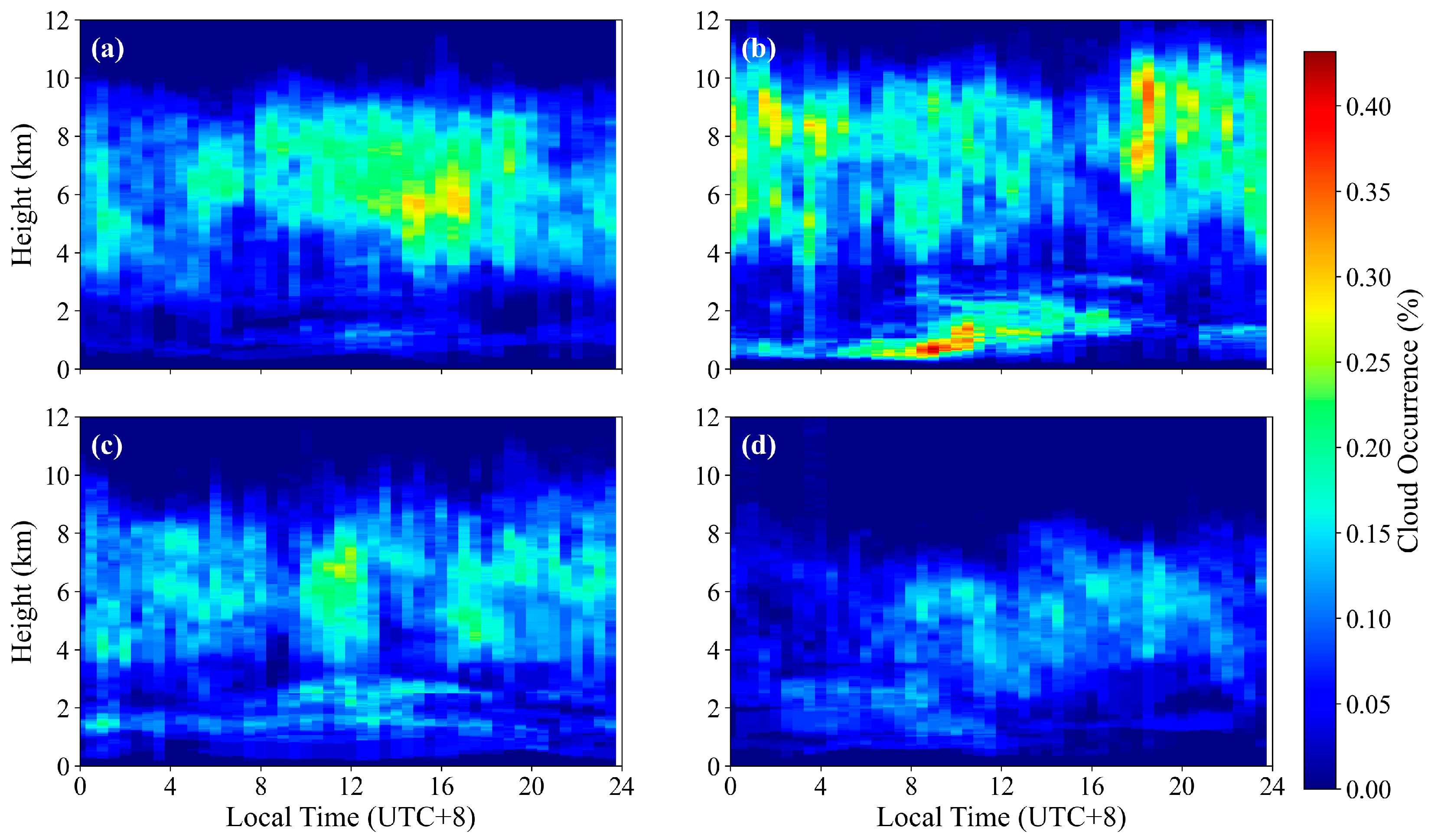

Cloud occurrence exhibits strong seasonal and diurnal variability, with the highest frequency in summer and the lowest in winter. Low-level clouds predominantly occur during daytime, closely linked to boundary layer development, while mid- and high-level clouds show a bimodal diurnal pattern influenced by terrain-induced afternoon convection and nocturnal convective activity.

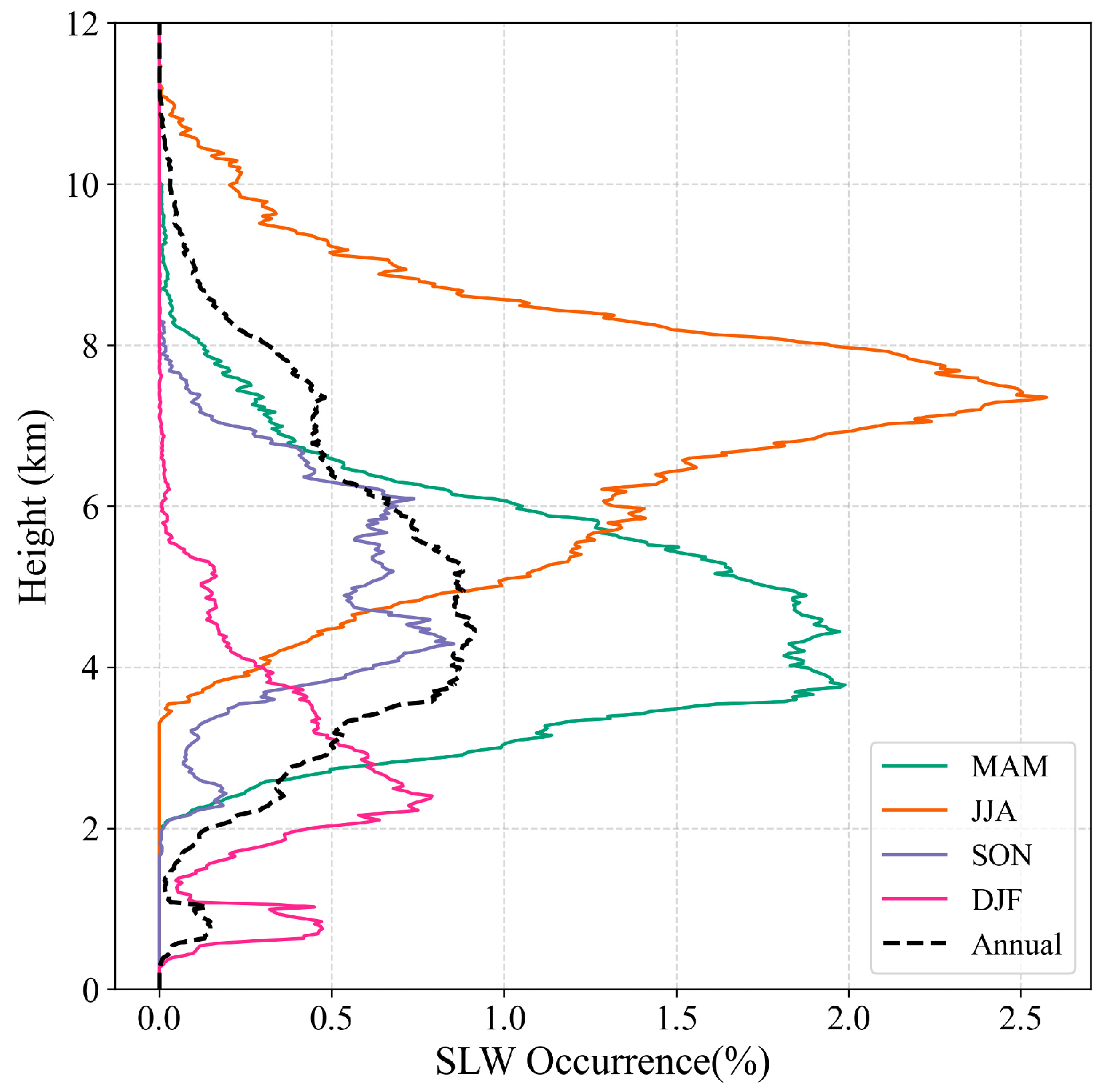

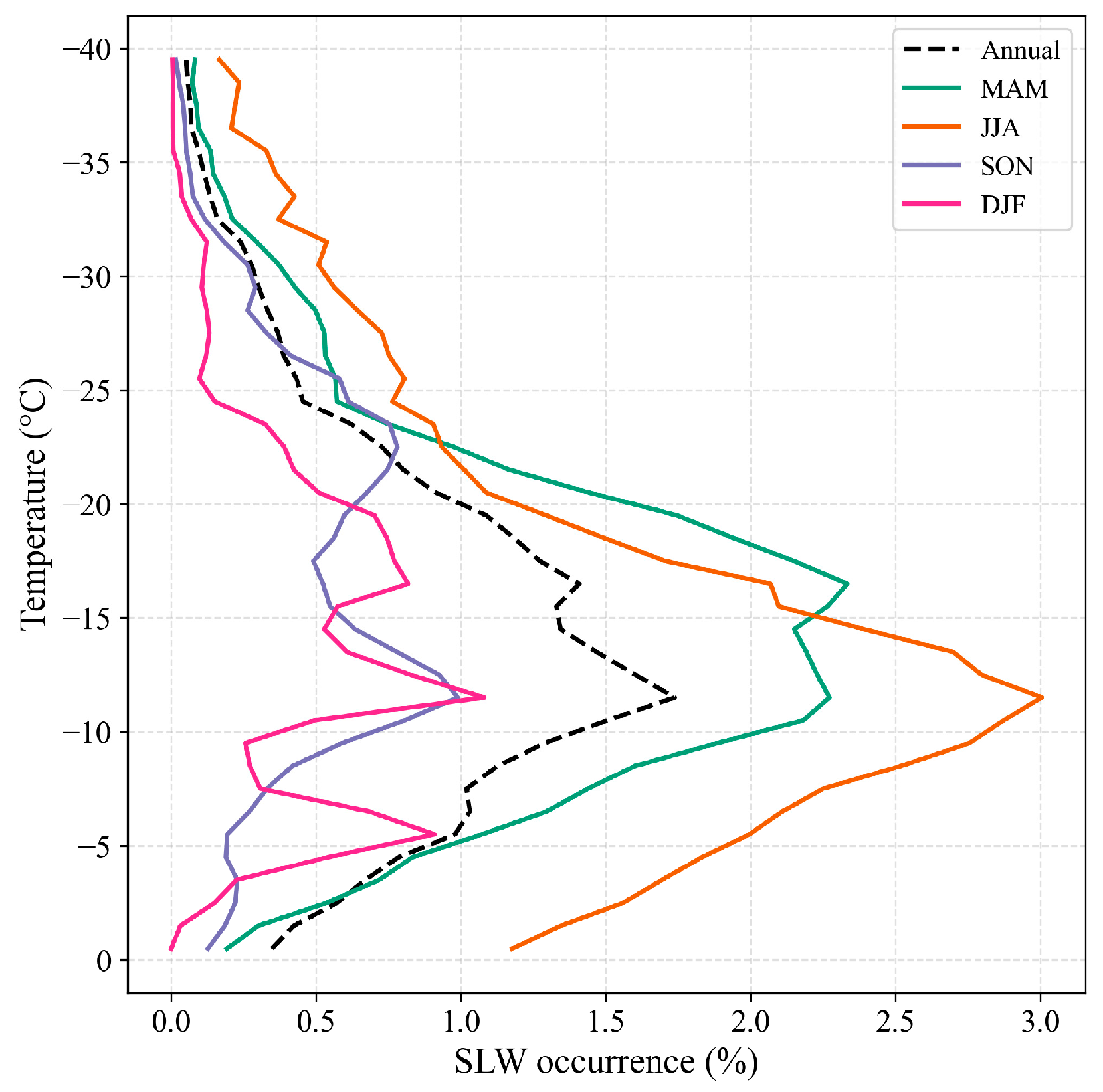

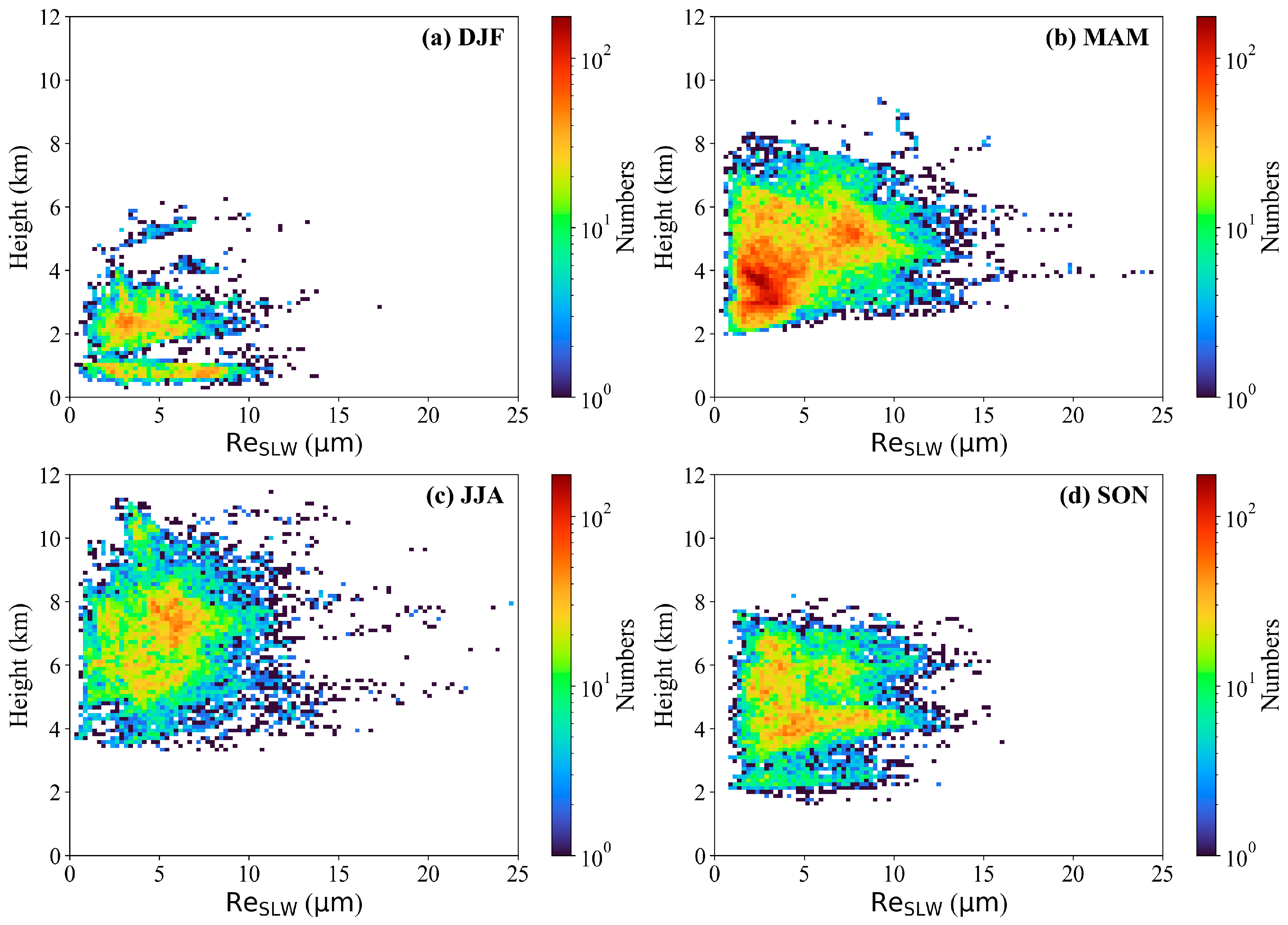

The vertical distribution of SLW is distinctly bimodal and seasonally dependent. A mid- to upper-level maximum (4–7.5 km) prevails in spring and summer, a pattern particularly pronounced near 7.5 km in summer. This reflects the role of deep convective updrafts in transporting liquid droplets above the freezing level, thereby forming mixed-phase cloud tops rich in SLW. In contrast, low-level SLW (1–2 km) occurs almost exclusively in winter, where it is associated with shallow, stable stratiform clouds under subfreezing conditions. The temperature-dependent occurrence probability of SLW clouds has an annual maximum at −12 °C. SLW shows strong seasonal and diurnal variability: dominant in mid-upper levels during spring/summer days, with a secondary night peak in summer; confined to low levels in winter under stable conditions; and weakly variable in autumn.

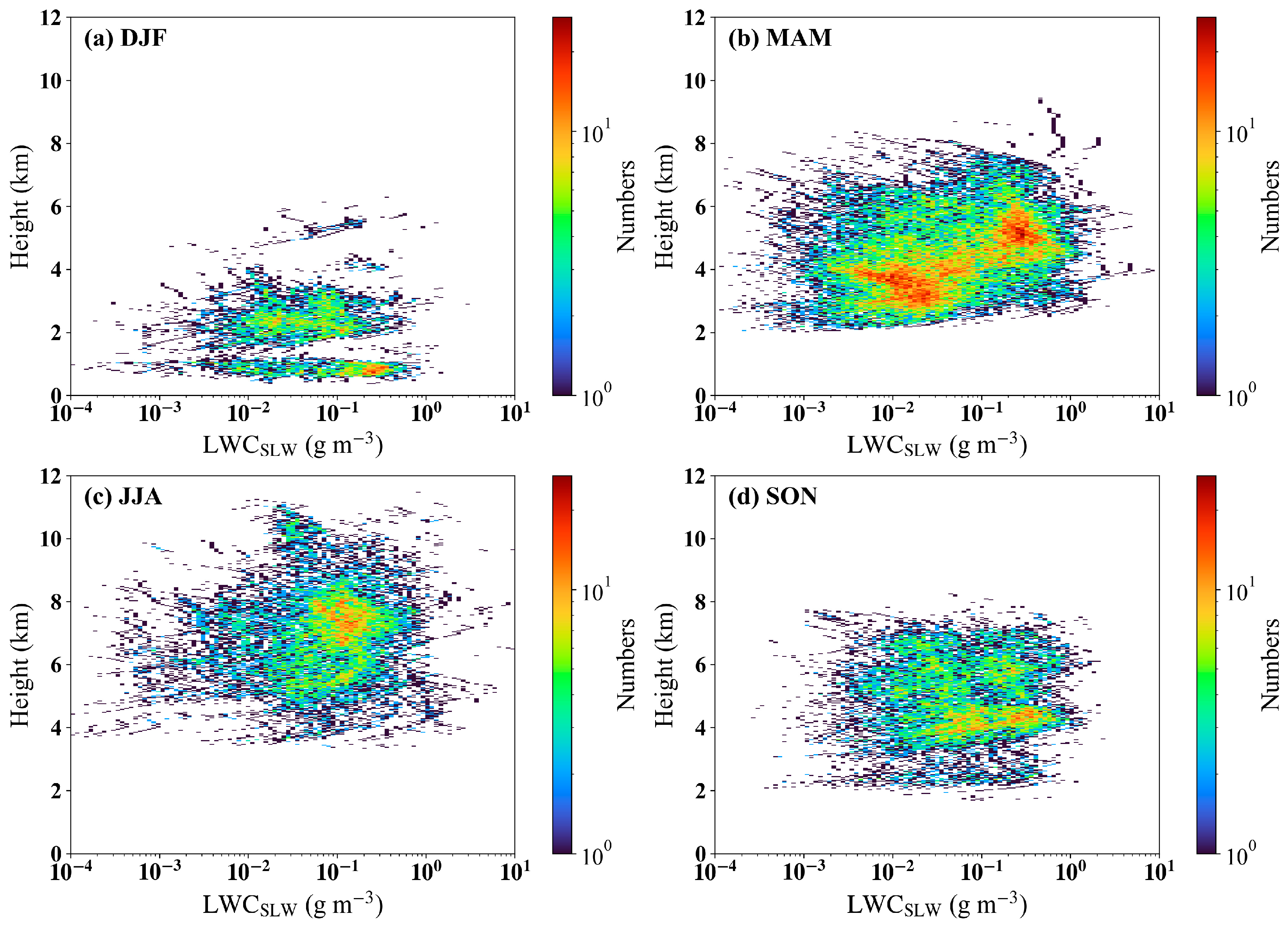

During spring, summer, and autumn, SLW is characterized by effective radii of 5–10 μm and LWCSLW of 0.1–1.0 g m−3, with a secondary mode of smaller droplets and lower LWC. In winter, SLW exhibits relatively larger droplets (6–8 μm) despite lower LWC (0.1–0.2 g m−3), consistent with slow condensational growth under cold, stable conditions.

To our knowledge, this work presents the first ground-based vertically resolved SLW based on synergy of multiple observations over North China Plain. This dataset fills a critical observational gap regarding mixed-phase clouds in mid-latitude continental regions and provides a robust benchmark for evaluating cloud microphysics parameterizations in numerical models [

34]. Our findings offer immediate practical value for guiding operational weather modification. The precise seasonal and diurnal characterizations of SLW vertical distribution, liquid water content, and droplet effective radius provide critical insights for optimizing key operational decisions, including seeding catalyst type, altitude selection, and timing, thereby enhancing the efficiency of artificial precipitation enhancement in this water-stressed region.

Despite these contributions, this study also has some limitations: drizzle or light precipitation contamination was not identified or removed, which may lead to slight biases in low-level LWC.

Building directly on the specific processes revealed in this study, we propose three promising directions for future work:

The algorithm and insights gained here will be applied to a distributed observation network across North China. This will not only help construct a spatially resolved SLW climatology but also allow us to investigate how regional topography and aerosol backgrounds influence the SLW distribution patterns we have identified, particularly the winter low-level and summer deep-convective modes.

To disentangle the physical mechanisms behind the distinct SLW vertical structures, we will integrate our observations with high-resolution WRF model simulations. Controlled sensitivity experiments will be designed to quantitatively assess the relative contributions of dynamical lifting (as implicated in the summer convective peaks) versus ambient thermodynamic conditions (critical for the shallow winter layers) in sustaining SLW.

The observed microphysical properties, especially the secondary mode of small droplets and the seasonally varying effective radius, suggest potential influences from ice-nucleating particles (INPs) and background aerosols. Future work will incorporate co-located aerosol and INP observations to preliminarily investigate how INP concentrations modulate SLW depletion rates and phase transition efficiency, a key uncertainty in climate prediction.