Physics-Constrained Deep Learning with Adaptive Z-R Relationship for Accurate and Interpretable Quantitative Precipitation Estimation

Highlights

- A hybrid framework integrates physical knowledge with deep learning models.

- An adaptive Z-R branch is built by extending the squeeze-and-excitation network.

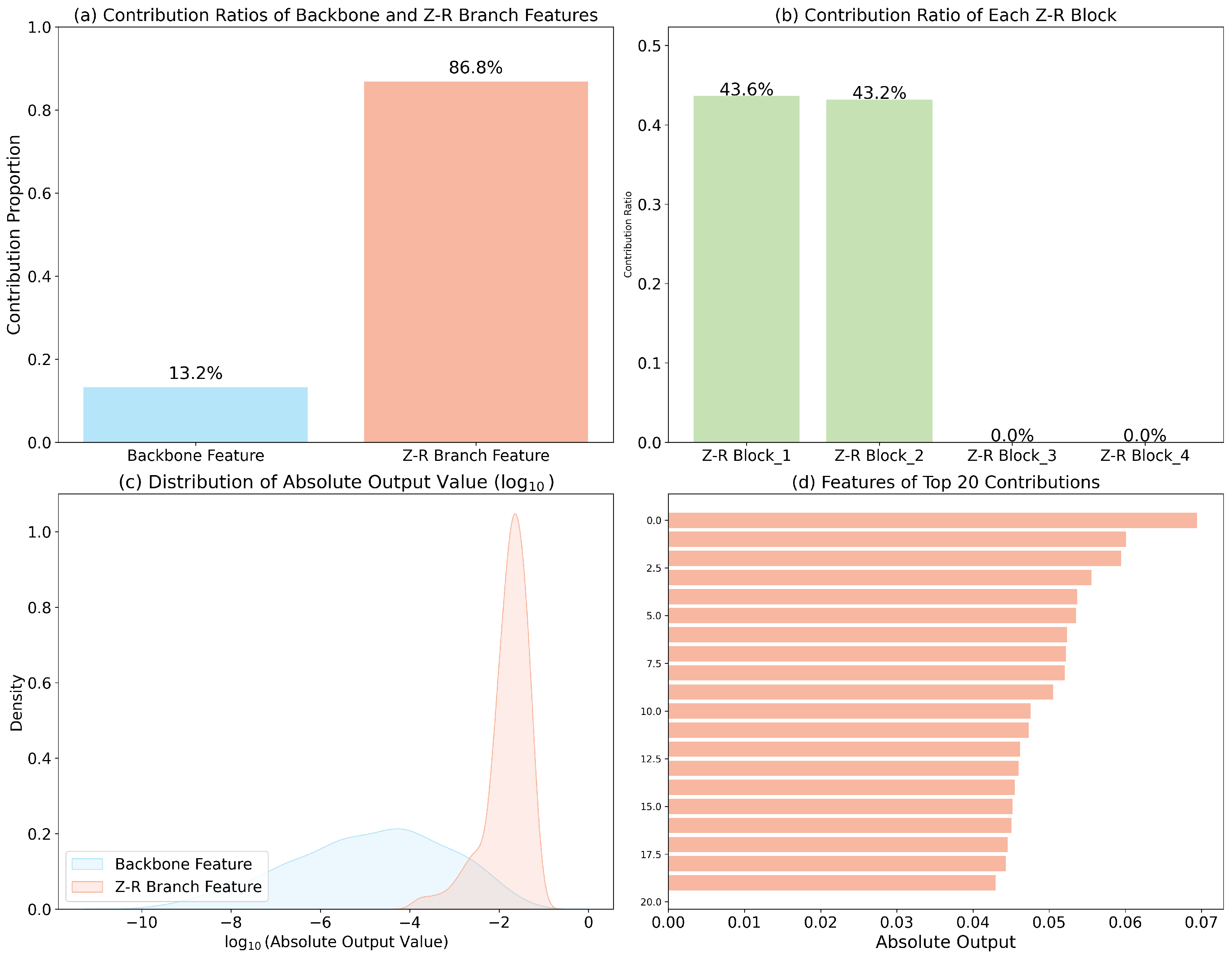

- FusionQPE’s explainability is shown by comparing contributions of DL and Z-R branches.

- FusionQPE is trained and tested using real radar and rainfall observations.

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Physics-constrained fusion framework: A novel and effective hybrid framework is proposed to tightly integrate physical knowledge with DL models. The FusionQPE framework fully leverages both physical Z-R relationship and data-driven feature extraction, providing a generalizable strategy for developing hybrid physics–AI hybrid models in other scientific and engineering domains.

- Adaptive Z-R branch: An adaptive Z-R branch is developed by extending the SE network. This branch automatically learns the two parameters of the Z-R relationship through a channel-wise attention mechanism applied to each dense block, enabling dynamic adjustment across various precipitation patterns.

- Interpretable fusion mechanism: A linear fusion layer is introduced to integrate the outputs of the adaptive Z-R branch and the DenseNet backbone. The learned linear weights and Z-R parameters provide quantitative interpretability, revealing the relative contribution of physical and data-driven components as well as the learned relationship between radar reflectivity and rainfall in precipitation estimation.

- Validation on real-world data: FusionQPE is trained and evaluated on real radar and rain gauge observational datasets collected from actual weather events, demonstrating its practicality and strong potential for integration into operational weather forecasting systems.

2. Related Work

2.1. Empirical Z-R Relationship

2.2. DL-Based QPE Method

2.3. Squeeze-and-Excitation Network

3. Materials and Methods

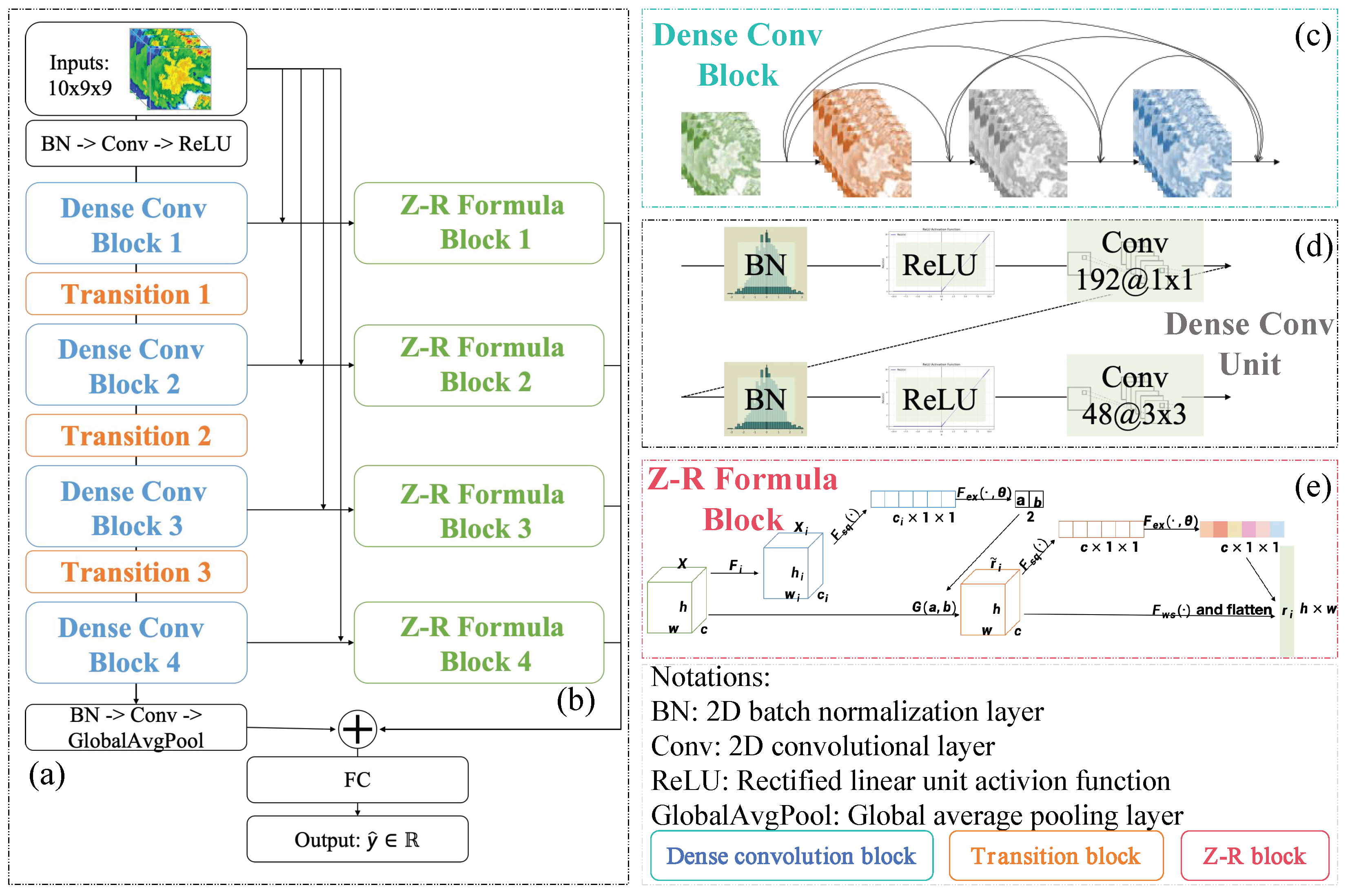

3.1. FusionQPE Framework

3.2. Backbone Network

3.2.1. Initial Head

3.2.2. Dense Convolutional Block

3.2.3. Transition Block

3.2.4. Vectorization Block

3.3. Adaptive Z-R Branch

3.3.1. Z-R Formula Block

3.3.2. SE-Based Parameter Learner

3.3.3. SE-Based Temporal Relationship Capturer

3.4. Fusion Layers

3.5. Interpretability of FusionQPE

4. Results

4.1. Dataset

4.1.1. Study Region

4.1.2. Data Quality Control

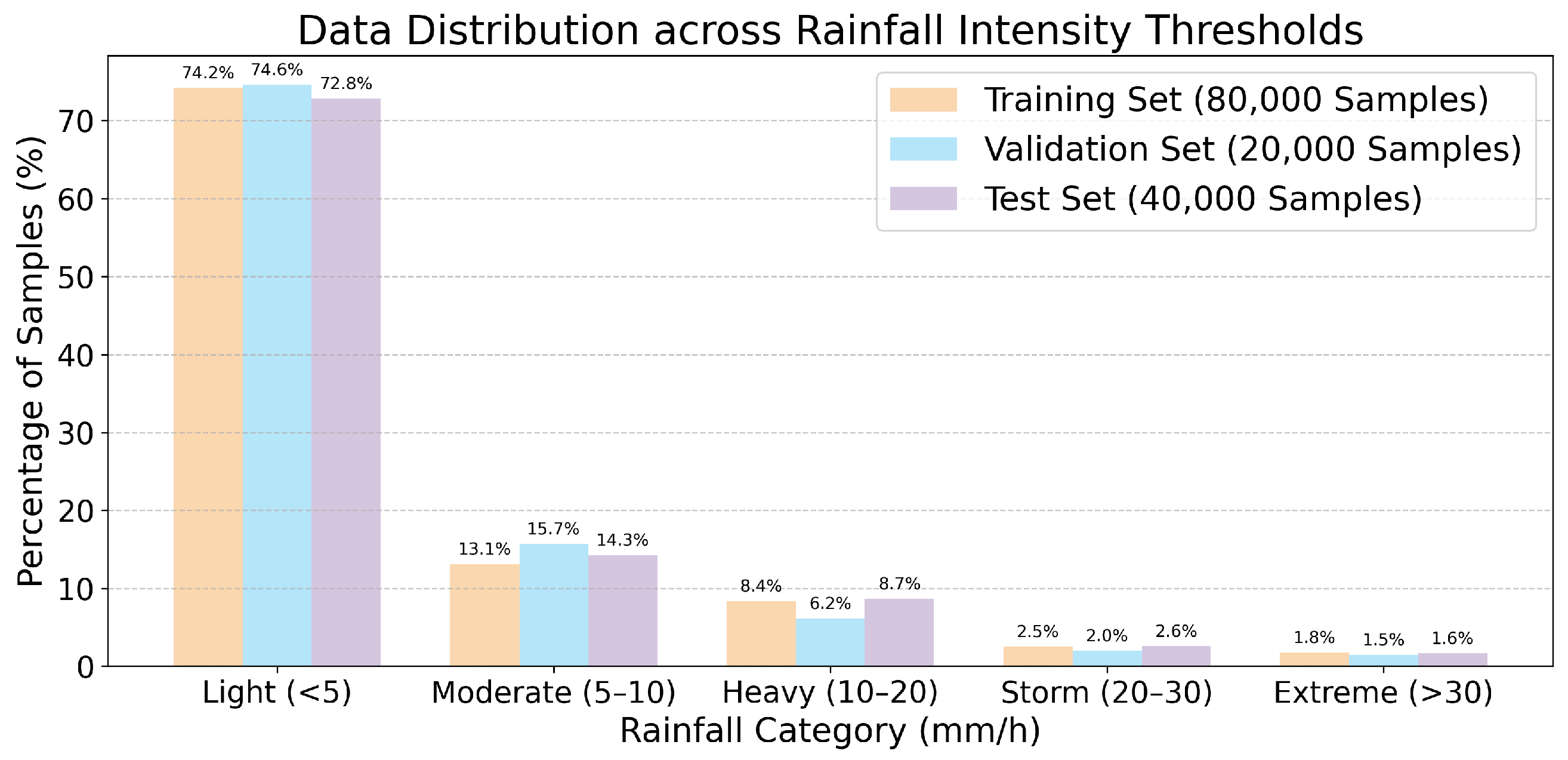

4.1.3. Rainfall Category Distribution

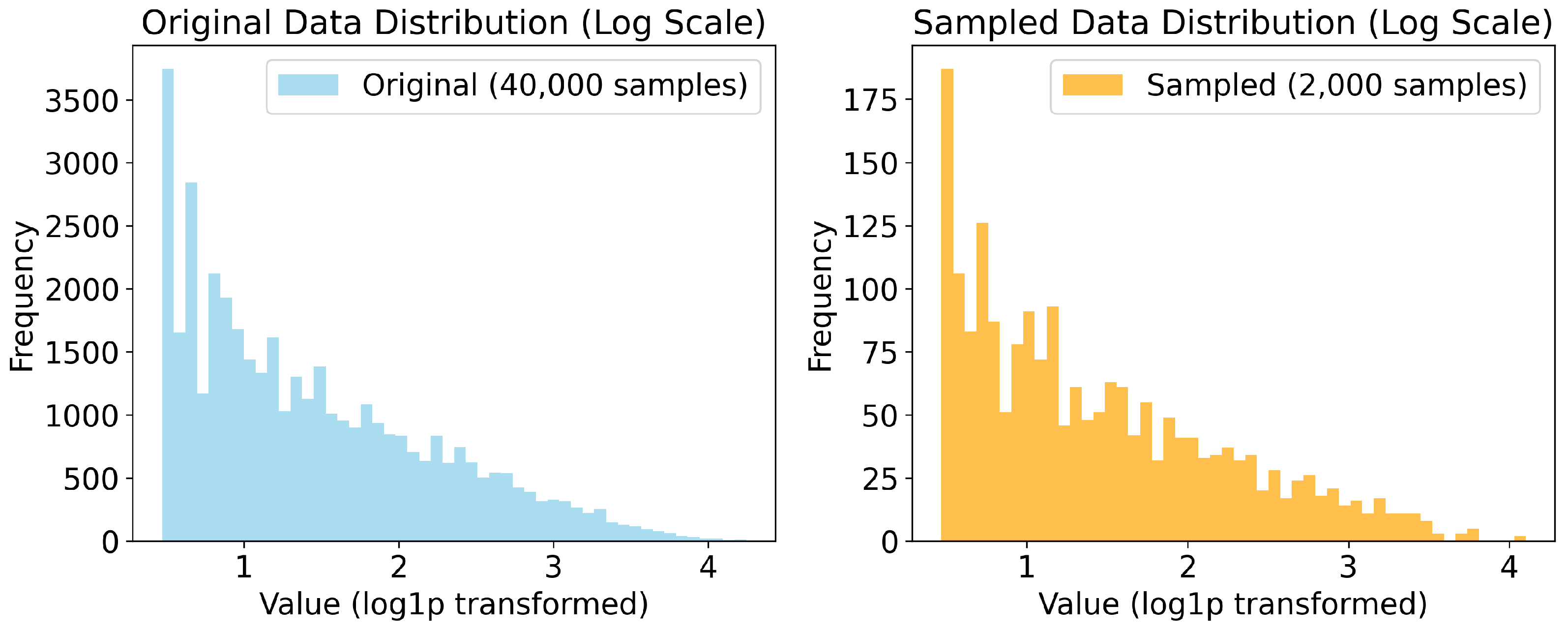

4.1.4. Data Preprocessing

4.2. Comparison Methods

4.2.1. Convective Relation

4.2.2. Stratiform Relation

4.2.3. ZRDL

4.2.4. RQPENet

4.2.5. StarNet

4.3. Experimental Setup

4.4. Experimental Results

4.5. Ablation Study

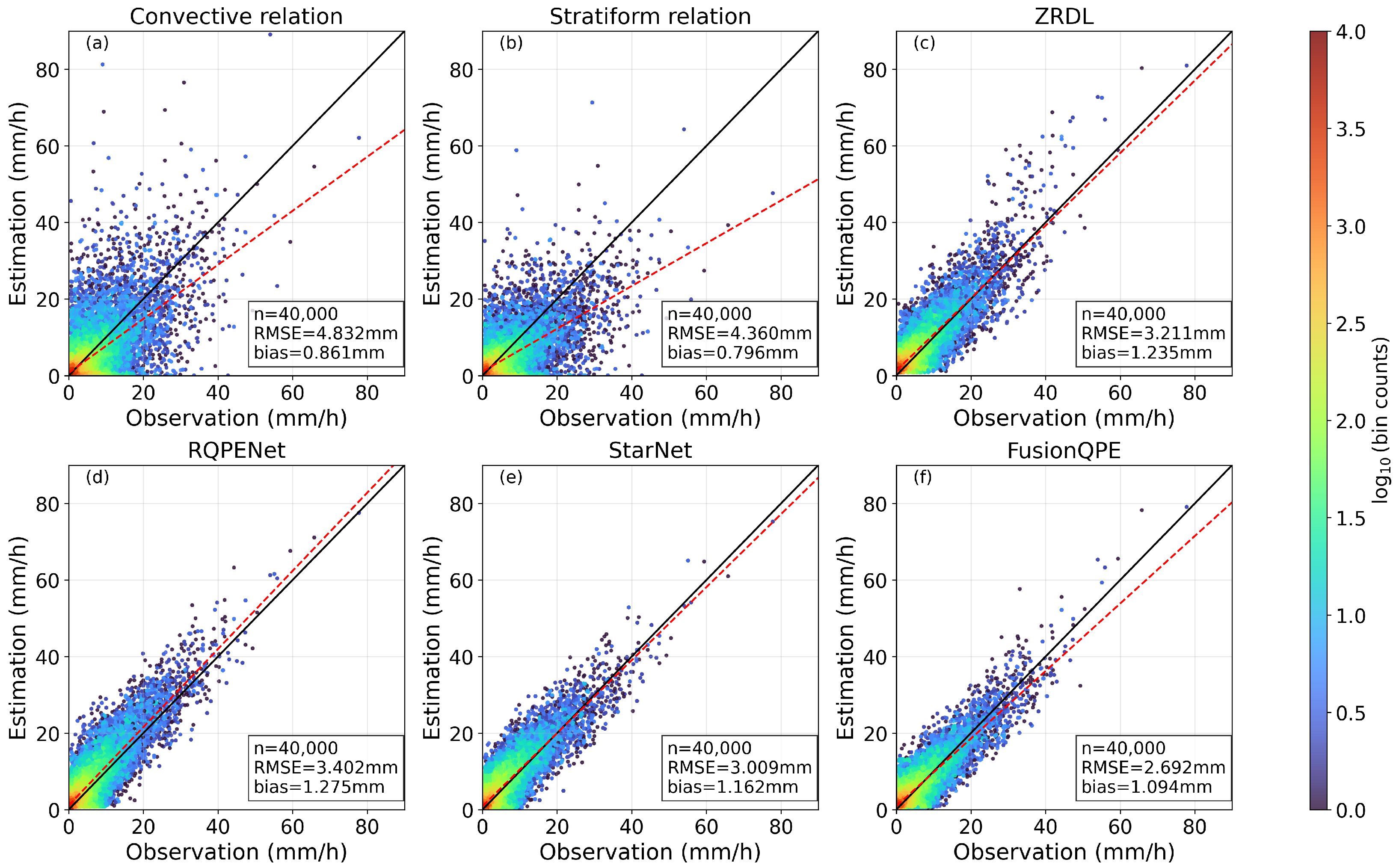

5. Discussion

5.1. Explainability Analysis of FusionQPE

5.2. Event-Based Performance and Operational Relevance

5.3. Comparison with Hybrid Model

5.4. Comparison with Dual-Polarization Architectures

5.5. Computational Efficiency and Operational Feasibility

5.6. Limitations and Future Directions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| QPE | Quantitative Precipitation Estimation |

| DL | Deep Learning |

| FusionQPE | Fusion Model for QPE |

| DenseNet | Dense COnvolutional Neural Network |

| SE | Squeeze-and-Excitation |

| Z | Radar Reflectivity |

| R | Rainfall Rate |

| BN | Batch Normalization |

| Conv | Convolutional Layer |

| ReLU | Rectified Linear Unit |

| AvgPool | Average Pooling Layer |

| GlobalAvgPool | Global AvgPool |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory |

| FC | Fully Connected Layer |

| MAE | Mean Absolute Error |

| RMSE | Root Mean Squared Error |

| BIAS | bias |

| CC | Correlation Coefficient |

| NSE | Normalized Standard Error |

| ACC | Accuracy |

| POD | Probability of Detection |

| FAR | False Alarm Ratio |

| CSI | Critical Success Index |

| HSS | Heidke Skill Score |

| TP | True Positive |

| TN | True Negative |

| FP | False Positive |

| FN | False Negative |

References

- Schmid, F.; Wang, Y.; Harou, A. Nowcasting guidelines—A summary. Bulletin 2019, 68, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Schmid, W.; Mecklenburg, S.; Joss, J. Short-term risk forecasts of heavy rainfall. Water Sci. Technol. 2002, 45, 121–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, P.; Thorpe, A.; Brunet, G. The quiet revolution of numerical weather prediction. Nature 2015, 525, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castorina, G.; Caccamo, M.T.; Colombo, F.; Magazù, S. The role of physical parameterizations on the numerical weather prediction: Impact of different cumulus schemes on weather forecasting on complex orographic areas. Atmosphere 2021, 12, 616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bringi, V.N.; Chandrasekar, V. Polarimetric Doppler Weather Radar: Principles and Applications; Cambridge University Press: Singapore, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, W.; Pang, L.; Sheng, V.S.; Wang, Q. STUNNER: Radar echo extrapolation model based on spatiotemporal fusion neural network. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 5103714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Shu, T.; Zhao, H.; Zhong, G.; Chen, X. TempEE: Temporal–spatial parallel transformer for radar echo extrapolation beyond autoregression. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 5108914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novák, P.; Březková, L.; Frolík, P. Quantitative precipitation forecast using radar echo extrapolation. Atmos. Res. 2009, 93, 328–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryzhkov, A.; Zhang, P.; Bukovčić, P.; Zhang, J.; Cocks, S. Polarimetric radar quantitative precipitation estimation. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Li, J.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Huo, H. Quantitative precipitation estimation in the Tianshan mountains based on machine learning. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 3962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, W.; Si, J.; Zhang, L.; Han, L.; Chen, Y. Enhanced Multimodal-fusion Network for Radar Quantitative Precipitation Estimation Incorporating Relative Humidity Data. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 4107213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyette, J.S. The Z-Relation in Theory and Practice; University of Rochester: Rochester, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Y.Y.; Chang, C.T.; Chen, B.F.; Kuo, H.C.; Lee, C.S. Extracting 3d radar features to improve quantitative precipitation estimation in complex terrain based on deep learning neural networks. Weather Forecast. 2023, 38, 273–289. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Chen, H.; Han, L. Polarimetric radar quantitative precipitation estimation using deep convolutional neural networks. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 4102911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Chen, H.; Han, L.; Lee, W.C. StarNet: A deep learning model for enhancing Polarimetric radar quantitative precipitation estimation. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 4106513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Hu, Z.; Zheng, J.; Wang, L.; Zhu, Y. Study on quantitative precipitation estimation by polarimetric radar using deep learning. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 2024, 41, 1147–1160. [Google Scholar]

- Biondi, A.; Facheris, L.; Argenti, F.; Cuccoli, F. Comparison of Different Quantitative Precipitation Estimation Methods Based on a Severe Rainfall Event in Tuscany, Italy, November 2023. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 3985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Xu, M.; Wang, Z.; Li, J.; Zheng, J.; Yuan, M.; Tao, Y.; Shi, L. Spatiotemporal Distribution and Applicability Evaluation of Remote Sensing Precipitation in River Basins Across Mainland China. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Cui, X.; Jiang, N. Modelling the ZR Relationship of Precipitation Nowcasting Based on Deep Learning. Comput. Mater. Contin. 2022, 72, 1939–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Liu, Z.; Van Der Maaten, L.; Weinberger, K.Q. Densely connected convolutional networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 4700–4708. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, J.; Shen, L.; Sun, G. Squeeze-and-excitation networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 7132–7141. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, J.S.; Palmer, W.M.K. THE Distribution of Raindrops with Size. J. Atmos. Sci. 1948, 5, 165–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, S.M. WSR-88D radar rainfall estimation: Capabilities, limitations and potential improvements. Natl. Weather Dig. 1996, 20, 26–38. [Google Scholar]

- Fournier, J.D. Reflectivity-Rainfall Rate Relationships in Operational Meteorology; National Weather Service Technical Memo, National Weather Service: Tallahassee, FL, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Bournas, A.; Baltas, E. Determination of the ZR relationship through spatial analysis of X-band weather radar and rain gauge data. Hydrology 2022, 9, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenfeld, D.; Ulbrich, C.W. Cloud microphysical properties, processes, and rainfall estimation opportunities. Meteorol. Monogr. 2003, 30, 237–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Howard, K.; Langston, C.; Kaney, B.; Qi, Y.; Tang, L.; Grams, H.; Wang, Y.; Cocks, S.; Martinaitis, S.; et al. Multi-Radar Multi-Sensor (MRMS) quantitative precipitation estimation: Initial operating capabilities. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2016, 97, 621–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Liu, L.; Ding, Y. Improvement of radar quantitative precipitation estimation based on real-time adjustments to ZR relationships and inverse distance weighting correction schemes. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 2012, 29, 575–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Liu, H.; Yao, Y.; Ni, T.; Feng, Y. An integrated method of multiradar quantitative precipitation estimation based on cloud classification and dynamic error analysis. Adv. Meteorol. 2017, 2017, 1475029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Hinton, G.E. Imagenet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2012, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioffe, S.; Szegedy, C. Batch normalization: Accelerating deep network training by reducing internal covariate shift. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Lille, France, 7–9 July 2015; PMLR: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2015; pp. 448–456. [Google Scholar]

- Nair, V.; Hinton, G.E. Rectified linear units improve restricted boltzmann machines. In Proceedings of the 27th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML-10), Haifa, Israel, 21–24 June 2010; pp. 807–814. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, K.; Hu, Z.; Tan, H.; Canjin, H.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, J.; Zhi, J. Research on quantitative precipitation estimation using polarimetric radar using convolutional neural networks. J. Trop. Meteorol. (1004-4965) 2024, 40, 64. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, N.; Liu, J.; Kuang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Liao, Q.; Liu, Z. Characteristics and Influences of Precipitation Tendency in Foshan under Environmental Variations. J. Water Resour. Res. 2014, 3, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cressman, G.P. An operational objective analysis system. Mon. Weather Rev. 1959, 87, 367–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Student. The probable error of a mean. Biometrika 1908, 6, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Methods | MAE ↓

(mm/h) | RMSE ↓ (mm/h) | BIAS∼1 | CC ↑ | NSE ↓ | p-Values ↓ | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Convective Z-R relation | 2.7900 | 4.8315 | 0.8615 | 0.6462 | 0.6316 | 0.0 | [4.7165, 4.9343] |

| Stratiform Z-R relation | 2.6362 | 4.3597 | 0.7963 | 0.6511 | 0.5968 | 0.0 | [4.2863, 4.4330] |

| ZRDL | 2.1828 | 3.2110 | 1.2354 | 0.8618 | 0.4942 | 5.0625 × 10−220 | [3.1662, 3.2531] |

| RQPENet | 2.2717 | 3.4024 | 1.2746 | 0.8673 | 0.5143 | 0.0 | [3.3627, 3.4418] |

| StarNet | 2.0356 | 3.0094 | 1.1618 | 0.8713 | 0.4609 | 2.6060 × 10−99 | [2.9771, 3.0423] |

| FusionQPE | 1.8339 | 2.6924 | 1.0935 | 0.8799 | 0.4152 | [2.6644, 2.7222] |

| Threshold | 5.0 mm/h | 10.0 mm/h | ||||||||||

| Method | ACC ↑ | POD ↑ | FAR ↓ | CSI ↑ | HSS ↑ | ETS∼1 | ACC ↑ | POD ↑ | FAR ↓ | CSI ↑ | HSS ↑ | ETS∼1 |

| Convective Z-R relation | 0.8115 | 0.5504 | 0.3061 | 0.4429 | 0.4913 | 0.3257 | 0.9070 | 0.5145 | 0.4023 | 0.3822 | 0.5014 | 0.3346 |

| Stratiform Z-R relation | 0.8090 | 0.5352 | 0.3066 | 0.4328 | 0.4810 | 0.3166 | 0.9097 | 0.4412 | 0.3609 | 0.3532 | 0.4740 | 0.3106 |

| ZRDL | 0.8306 | 0.7901 | 0.3429 | 0.5595 | 0.5980 | 0.4265 | 0.9293 | 0.8019 | 0.3513 | 0.5591 | 0.6773 | 0.5121 |

| RQPENet | 0.8256 | 0.7974 | 0.3545 | 0.5545 | 0.5900 | 0.4185 | 0.9152 | 0.8421 | 0.4162 | 0.5262 | 0.6423 | 0.4731 |

| StarNet | 0.8340 | 0.8049 | 0.3400 | 0.5690 | 0.6080 | 0.4368 | 0.9262 | 0.8484 | 0.3750 | 0.5622 | 0.6784 | 0.5133 |

| FusionQPE | 0.8484 | 0.7749 | 0.2997 | 0.5819 | 0.6298 | 0.4596 | 0.9382 | 0.7695 | 0.2953 | 0.5818 | 0.7007 | 0.5393 |

| Threshold | 20.0 mm/h | 30.0 mm/h | ||||||||||

| Method | ACC ↑ | POD ↑ | FAR ↓ | CSI ↑ | HSS ↑ | ETS ∼1 | ACC ↑ | POD ↑ | FAR ↓ | CSI ↑ | HSS ↑ | ETS∼1 |

| Convective Z-R relation | 0.9685 | 0.4286 | 0.5912 | 0.2646 | 0.4023 | 0.2518 | 0.9897 | 0.4408 | 0.7180 | 0.2077 | 0.3390 | 0.2041 |

| Stratiform Z-R relation | 0.9746 | 0.2961 | 0.4640 | 0.2357 | 0.3696 | 0.2267 | 0.9934 | 0.2041 | 0.5798 | 0.1592 | 0.2718 | 0.1573 |

| ZRDL | 0.9804 | 0.7455 | 0.3962 | 0.5006 | 0.6572 | 0.4894 | 0.9935 | 0.7388 | 0.5212 | 0.4095 | 0.5779 | 0.4064 |

| RQPENet | 0.9758 | 0.8817 | 0.4749 | 0.4905 | 0.6465 | 0.4776 | 0.9933 | 0.9061 | 0.5246 | 0.4531 | 0.6205 | 0.4498 |

| StarNet | 0.9823 | 0.7881 | 0.3675 | 0.5406 | 0.6928 | 0.5299 | 0.9954 | 0.6857 | 0.3869 | 0.4786 | 0.6451 | 0.4761 |

| FusionQPE | 0.9857 | 0.7342 | 0.2727 | 0.5757 | 0.7234 | 0.5666 | 0.9962 | 0.6735 | 0.3038 | 0.5205 | 0.6827 | 0.5183 |

| MAE ↓ | RMSE ↓ | BIAS∼1 | CC ↑ | NSE ↓ | |

| Backbone | 2.0047 | 2.9579 | 1.1676 | 0.8662 | 0.4538 |

| 2ZR | 1.9652 | 2.9511 | 1.1597 | 0.8705 | 0.4449 |

| MSE | 2.2059 | 3.2737 | 1.2531 | 0.8649 | 0.4994 |

| FusionQPE | 1.8339 | 2.6924 | 1.0935 | 0.8799 | 0.4152 |

| ACC ↑ | POD ↑ | FAR ↓ | CSI ↑ | HSS ↑ | |

| 5.0 mm/h | |||||

| Backbone | 0.8415 | 0.7791 | 0.3167 | 0.5724 | 0.6169 |

| 2ZR | 0.8433 | 0.7697 | 0.3095 | 0.5722 | 0.6184 |

| MSE | 0.8266 | 0.8046 | 0.3542 | 0.5582 | 0.5938 |

| FusionQPE | 0.8484 | 0.7749 | 0.2997 | 0.5819 | 0.6298 |

| 10.0 mm/h | |||||

| Backbone | 0.9218 | 0.7858 | 0.3820 | 0.5289 | 0.6478 |

| 2ZR | 0.9293 | 0.7724 | 0.3441 | 0.5496 | 0.6694 |

| MSE | 0.9171 | 0.8034 | 0.4041 | 0.5200 | 0.6377 |

| FusionQPE | 0.9382 | 0.7695 | 0.2953 | 0.5818 | 0.7007 |

| 20.0 mm/h | |||||

| Backbone | 0.9835 | 0.7758 | 0.3414 | 0.5533 | 0.7040 |

| 2ZR | 0.9844 | 0.7928 | 0.3258 | 0.5732 | 0.7207 |

| MSE | 0.9795 | 0.8761 | 0.4266 | 0.5304 | 0.6830 |

| FusionQPE | 0.9857 | 0.7342 | 0.2727 | 0.5757 | 0.7234 |

| 30.0 mm/h | |||||

| Backbone | 0.9951 | 0.6980 | 0.4184 | 0.4647 | 0.6320 |

| 2ZR | 0.9946 | 0.7510 | 0.4604 | 0.4577 | 0.6253 |

| MSE | 0.9940 | 0.8245 | 0.4937 | 0.4570 | 0.6245 |

| FusionQPE | 0.9962 | 0.6735 | 0.3038 | 0.5205 | 0.6827 |

| Backbone | Z-R Block1 | Z-R Block2 | Z-R Block3 | Z-R Block4 | Estimation | Observation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case1 | −0.5962 | 0.0283 | 0.0015 | 0 | 0 | −0.5777 | −0.5733 |

| (7.94, 0.59) 1 | (21.22, 0.43) | (0, 0.07) | (0, −0.3) | ||||

| Case2 | 0.1831 | 0.1017 | 0.1437 | 0 | 0 | 0.4172 | 0.4199 |

| (9.35, 0.49) | (22.09, 0.46) | (0, 0.03) | (0, −0.24) | ||||

| Case3 | 0.8411 | 0.245 | 0.2051 | 0 | 0 | 1.2799 | 1.2751 |

| (9.07, 0.56) | (22.17, 0.49) | (0, 0.05) | (0, −0.22) | ||||

| Case4 | 1.4887 | 0.6597 | 0.5887 | 0 | 0 | 2.7258 | 2.7096 |

| (9.10, 0.62) | (22.55, 0.5) | (0, 0.03) | (0, −0.18) | ||||

| Case5 | 3.7583 | 0.4193 | 0.1843 | 0 | 0 | 4.3506 | 4.351 |

| (11.11, 0.56) | (25.03, 0.48) | (0, 0.05) | (0, −0.21) |

| Method | Params (M) | FLOPs (G) | Latency (ms) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ZRDL | 1.97 | 0.16 | 30.20 |

| RQPENet | 51.61 | 1.04 | 24.62 |

| StarNet | 3.58 | 0.20 | 32.55 |

| FusionQPE | 53.05 | 0.25 | 29.90 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Shu, T.; Zhao, H.; Cai, K.; Zhu, Z. Physics-Constrained Deep Learning with Adaptive Z-R Relationship for Accurate and Interpretable Quantitative Precipitation Estimation. Remote Sens. 2026, 18, 156. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010156

Shu T, Zhao H, Cai K, Zhu Z. Physics-Constrained Deep Learning with Adaptive Z-R Relationship for Accurate and Interpretable Quantitative Precipitation Estimation. Remote Sensing. 2026; 18(1):156. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010156

Chicago/Turabian StyleShu, Ting, Huan Zhao, Kanglong Cai, and Zexuan Zhu. 2026. "Physics-Constrained Deep Learning with Adaptive Z-R Relationship for Accurate and Interpretable Quantitative Precipitation Estimation" Remote Sensing 18, no. 1: 156. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010156

APA StyleShu, T., Zhao, H., Cai, K., & Zhu, Z. (2026). Physics-Constrained Deep Learning with Adaptive Z-R Relationship for Accurate and Interpretable Quantitative Precipitation Estimation. Remote Sensing, 18(1), 156. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010156