Thinning Methods and Assimilation Applications for FY-4B/GIIRS Observations

Highlights

- Wavelet transform modulus maxima (WTMM) is an effective method for FY-4B/GIIRS observation thinning in data assimilation systems.

- FY-4B/GIIRS observation assimilation can improve the accuracy of analysis and forecast fields.

- Retain “useful and effective” observational information from infrared hyperspectral atmospheric sounder for the assimilation system.

- Improve the quality of the analysis fields, as well as enhance the accuracy of numerical weather prediction.

Abstract

1. Introduction

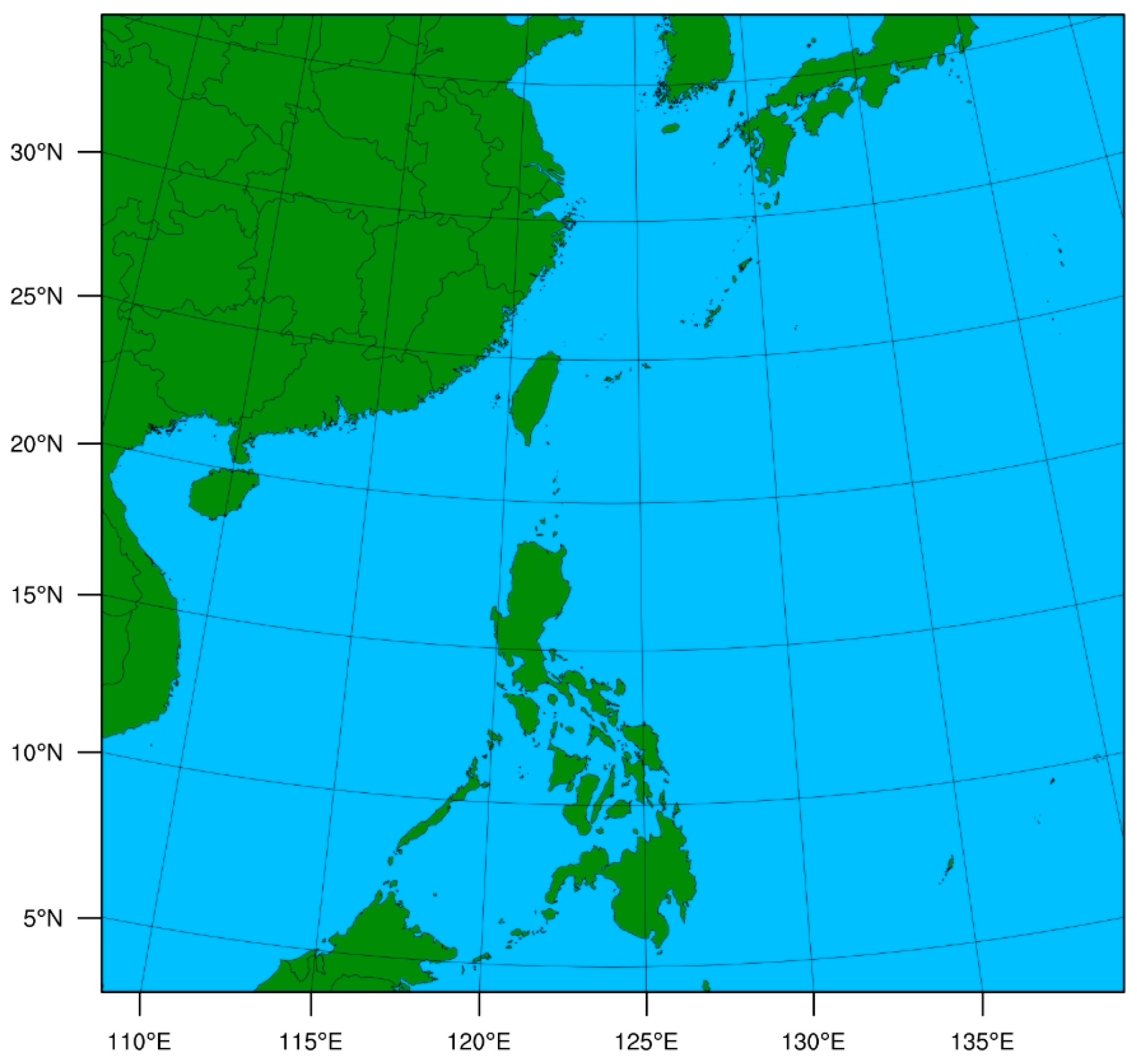

2. Data and Model

2.1. FY-4B/GIIRS Observations

2.2. Data Used for Evaluation

2.3. WRF Model and GSI Data Assimilation System

3. Method

3.1. WTMM Thinning Scheme

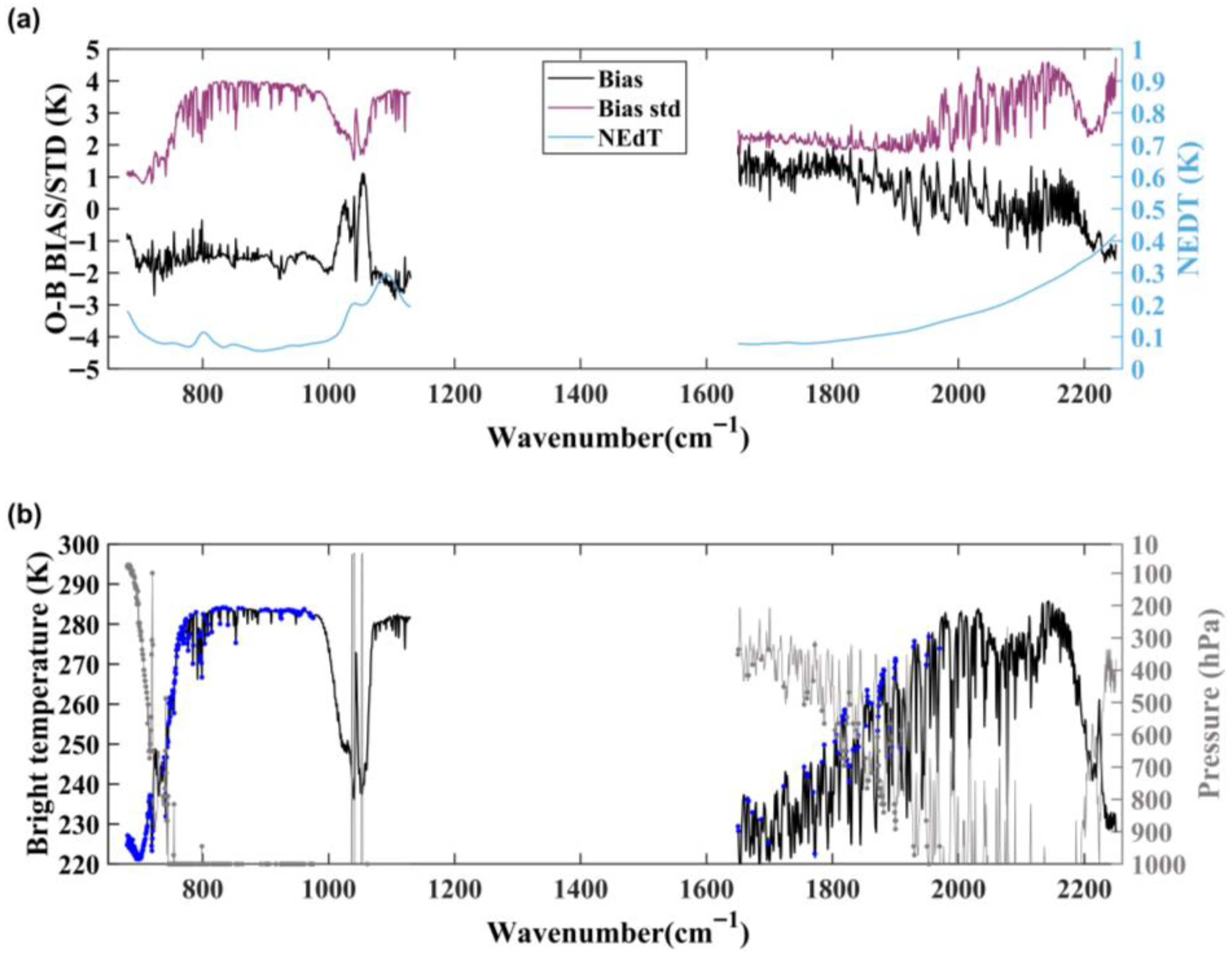

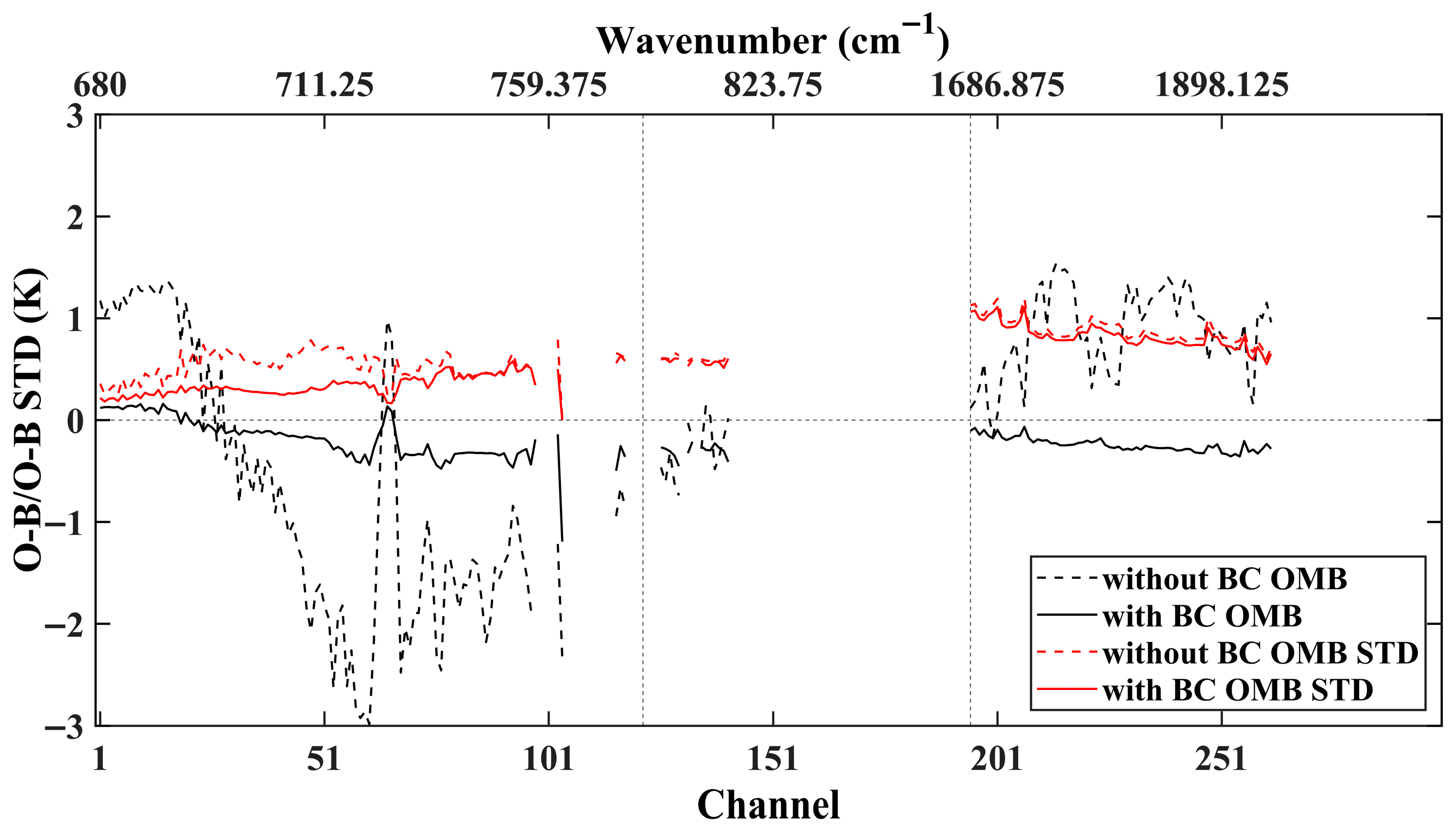

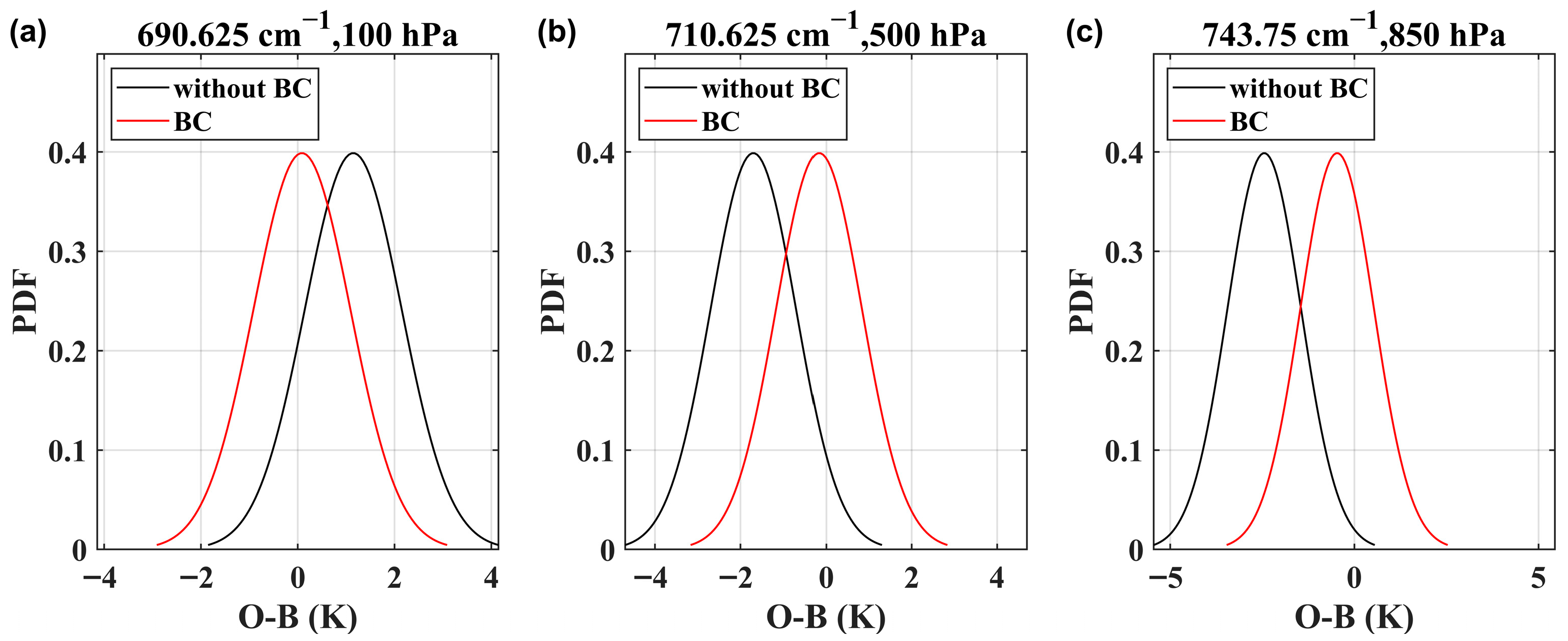

3.2. Bias Correction

3.3. Quality Control

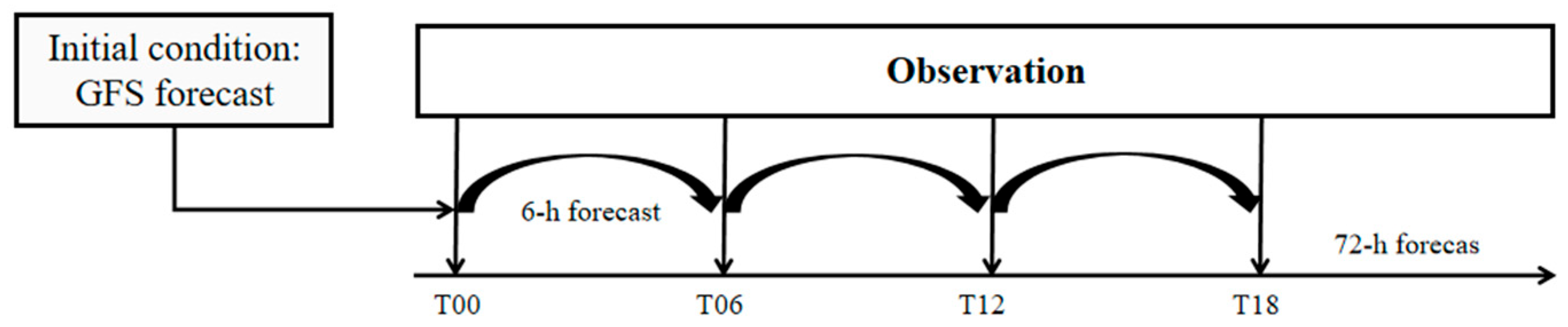

4. GIIRS Data Assimilation Experiment

4.1. Comparison of Thinning Schemes

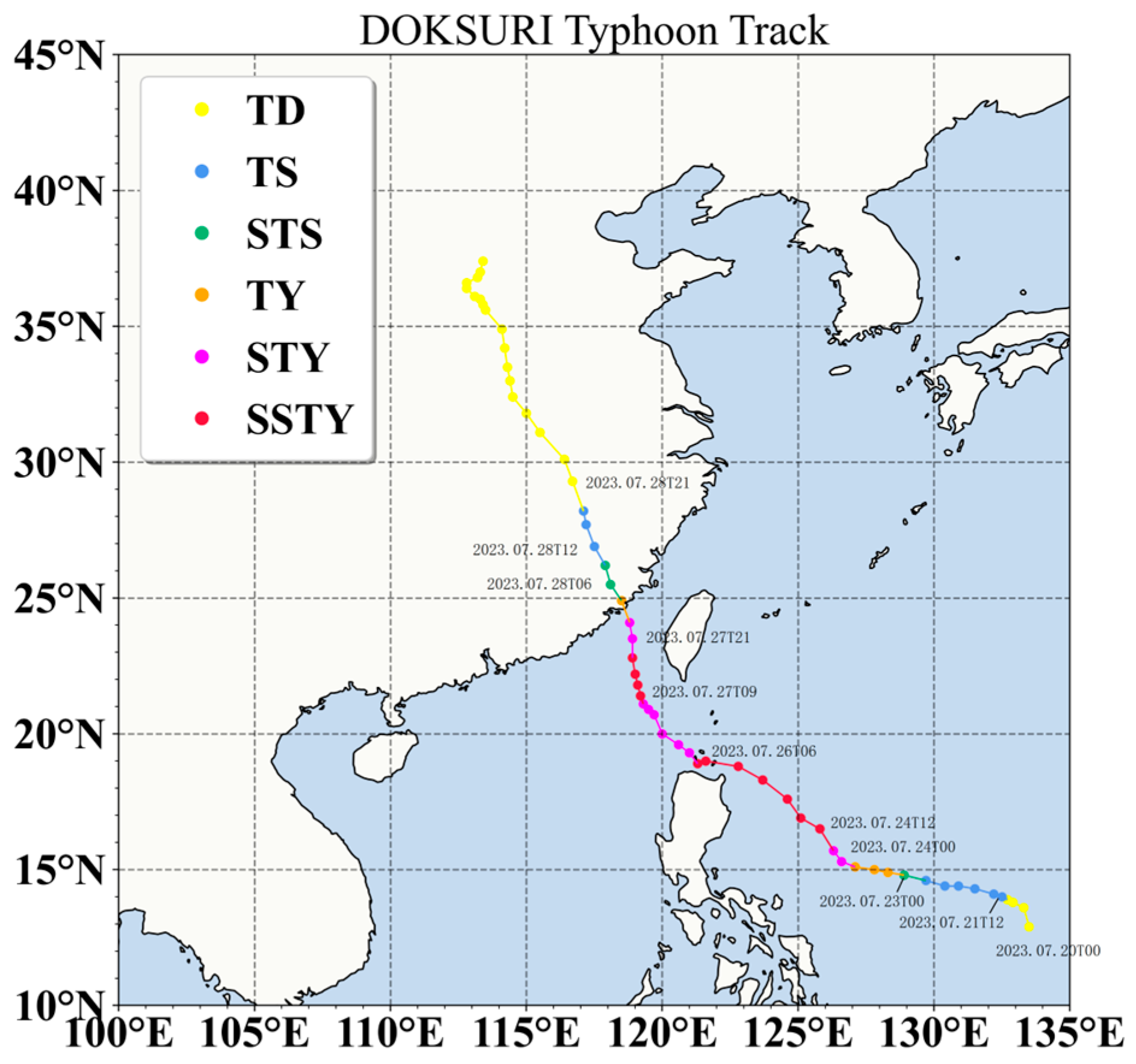

4.2. GIIRS Data Assimilation and Forecast Experiments

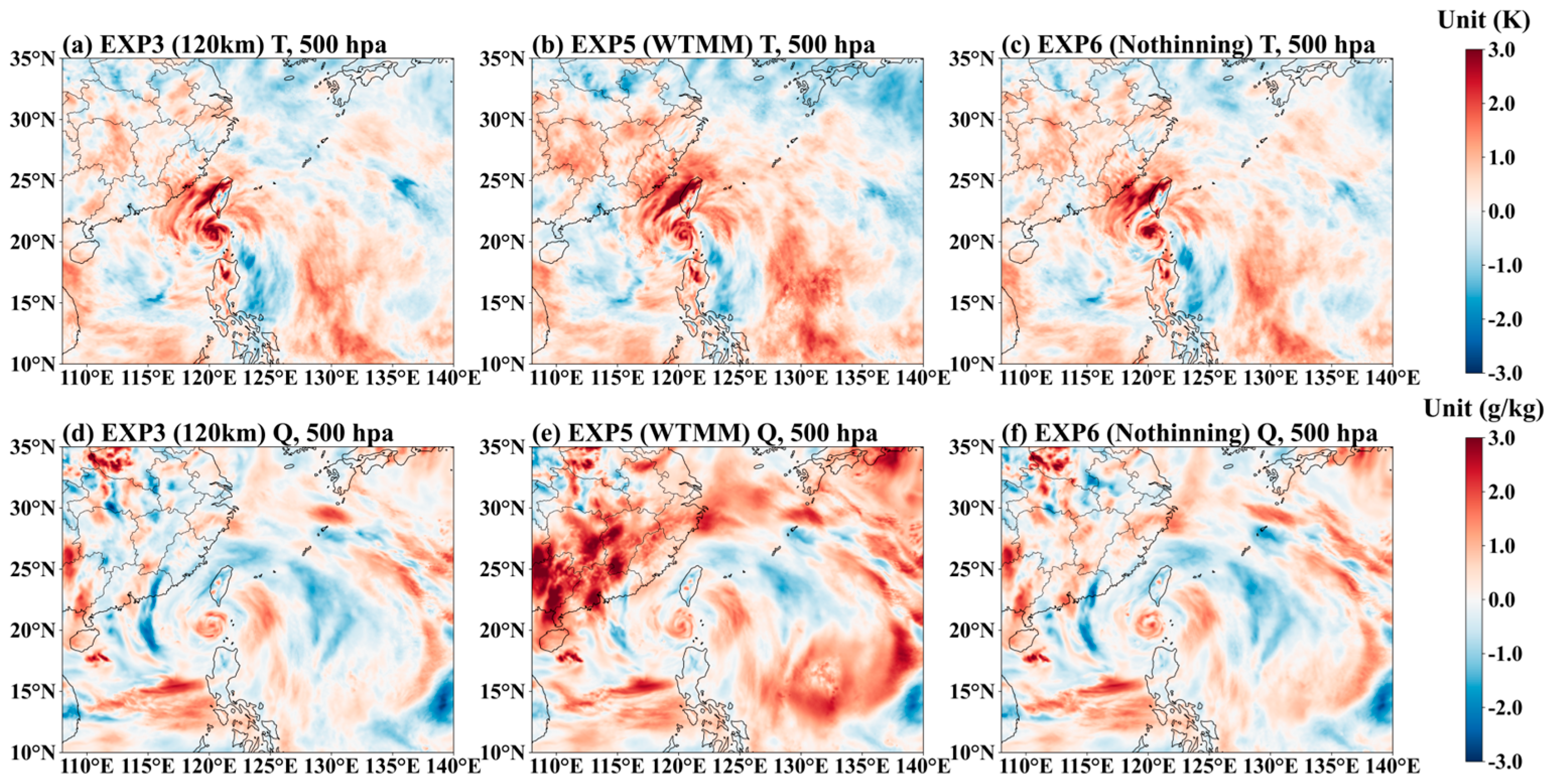

4.2.1. Impact on the Assimilation Analysis Fields

4.2.2. Impact on Forecast Fields of Temperature and Humidity

4.2.3. Impact on Typhoon Track and Intensity Forecasts

4.2.4. Impact on Precipitation Forecasts

5. Conclusions

- (1)

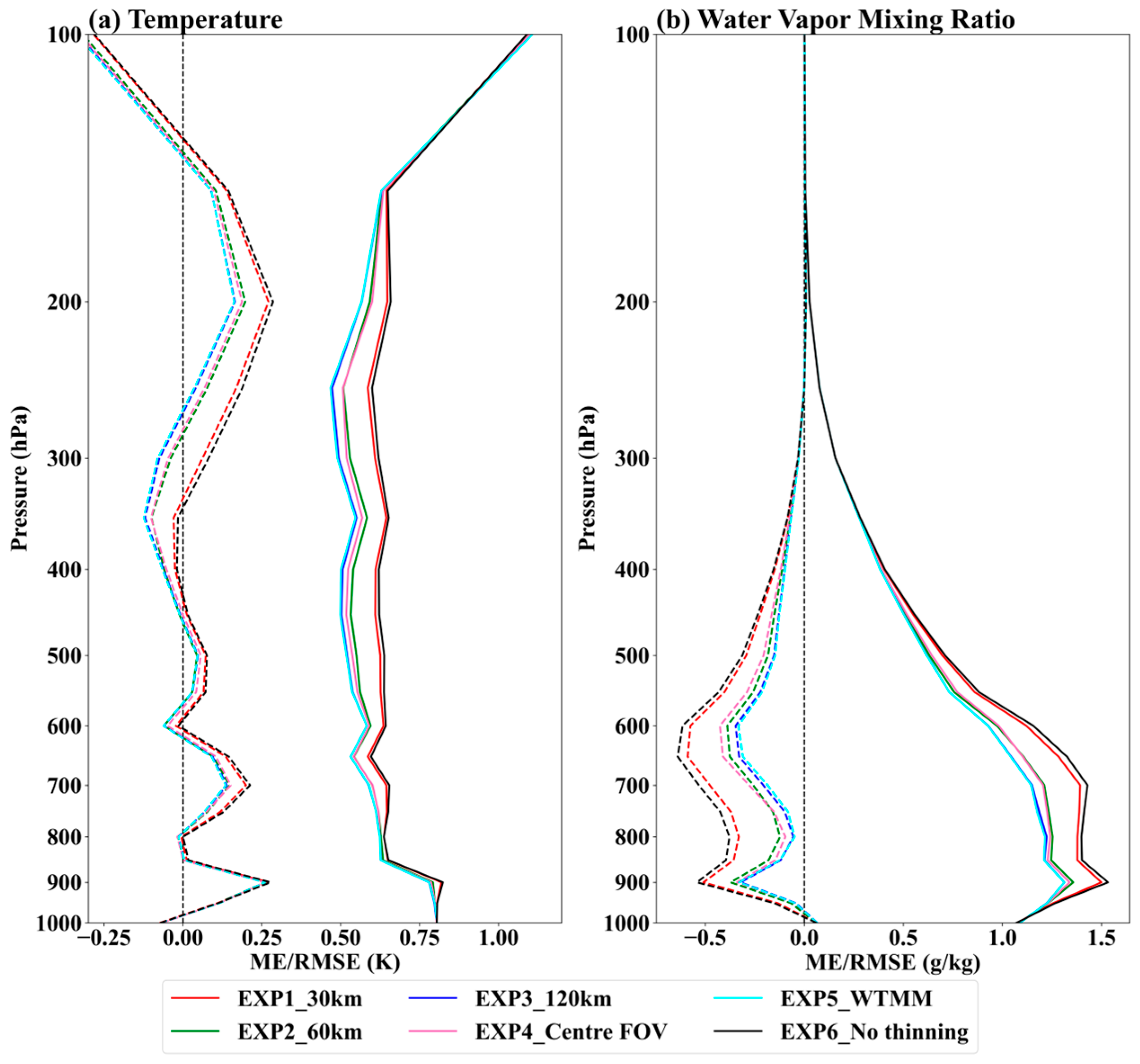

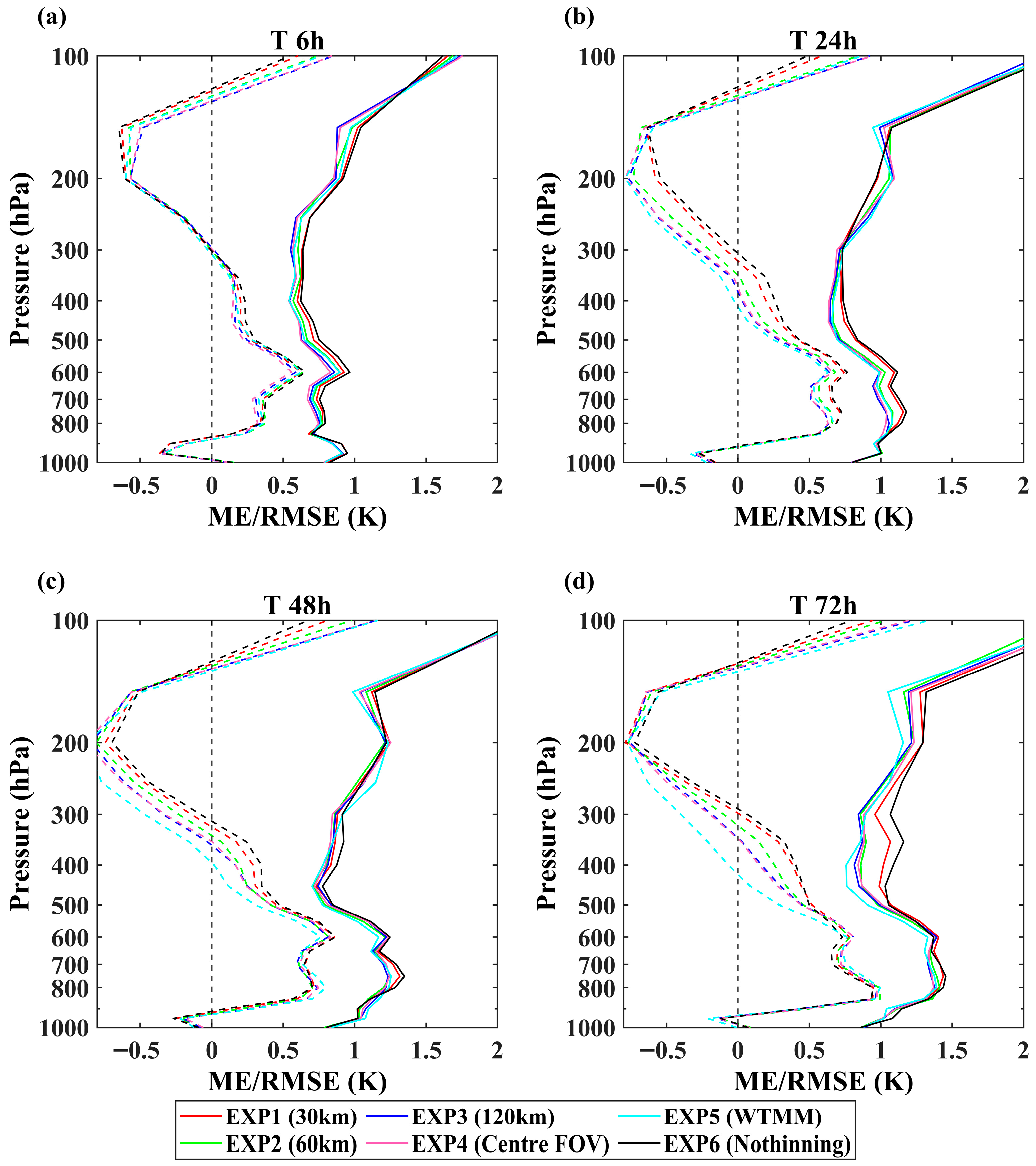

- The statistical averages from assimilation experiences four times (00 UTC, 06 UTC, 12 UTC, and 18 UTC) a day indicate that the WTMM scheme has the smallest mean errors and root mean square errors for both temperature and humidity profiles, followed by the 120 km scheme.

- (2)

- The no thinning scheme has the largest MEs and RMSEs at all pressure levels for temperature and humidity forecast fields at different forecast times, shown by cycling assimilation and forecast experiments. The temperature forecast errors after data thinning are decreased at altitudes below 300 hPa, with similar accuracy between the WTMM and 120 km schemes. The EXP3 (WTMM) scheme is gradually superior, with forecast time increasing.

- (3)

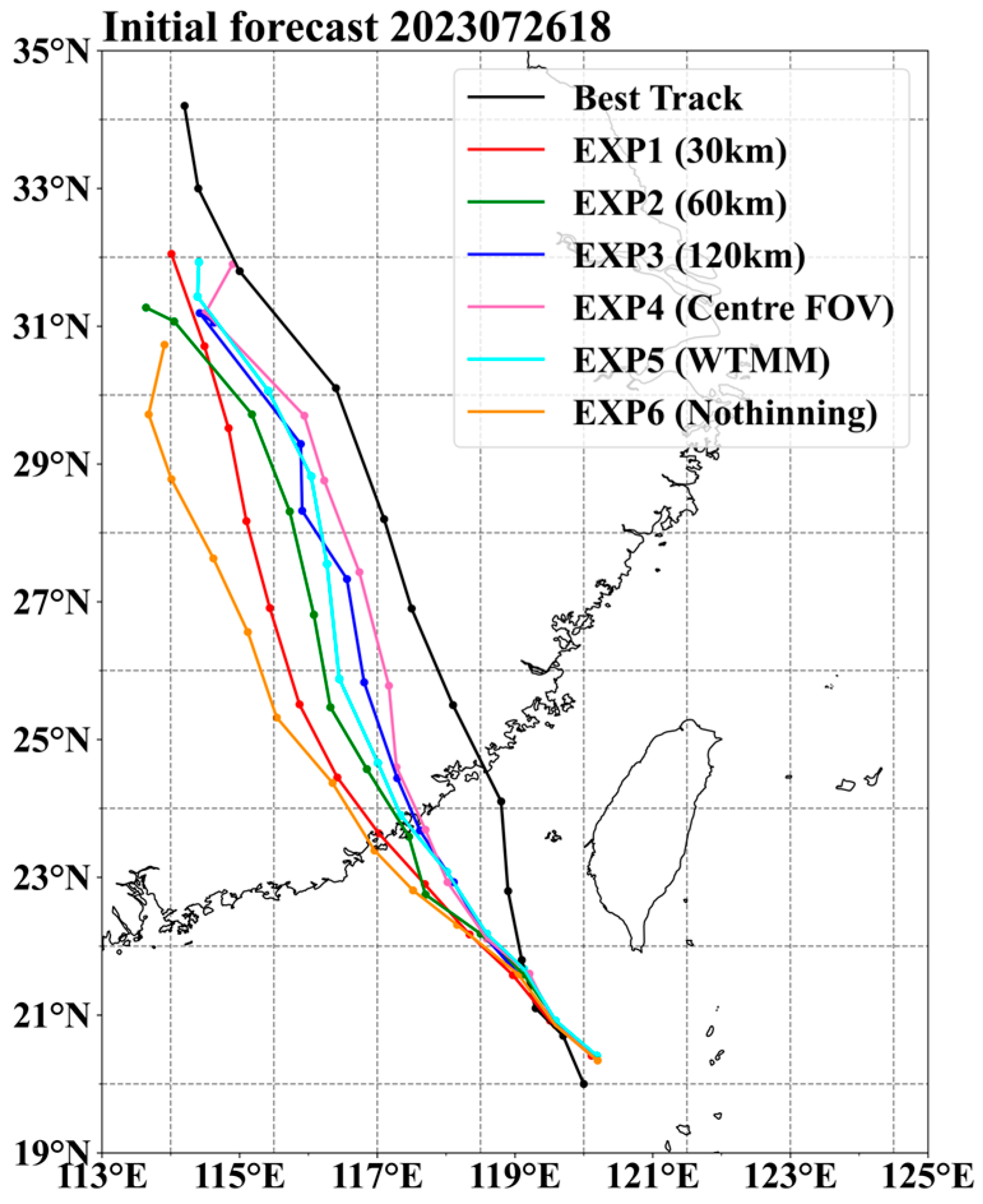

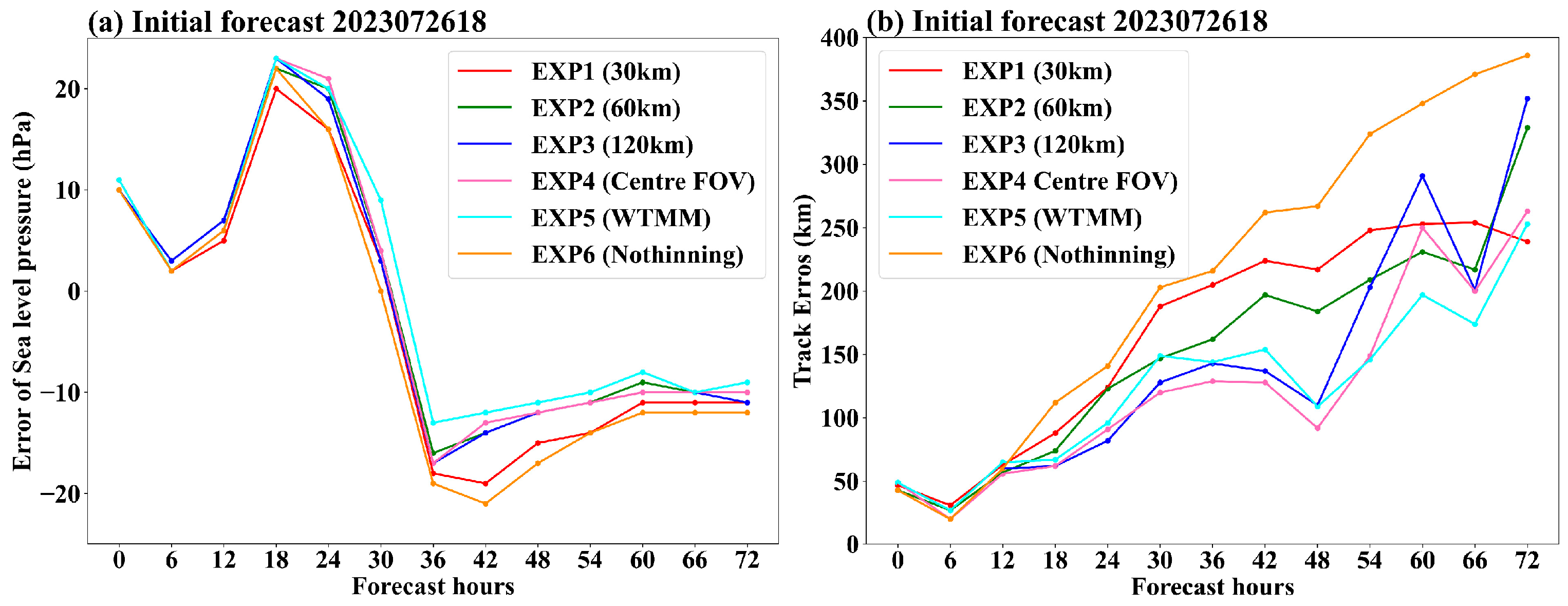

- The intensity forecasts are underestimated before the typhoon landfall but begin to be overestimated after landfall for all schemes. The forecast intensities of the WTMM scheme are closest to the actual observations as the forecast time increases. The typhoon track error forecasted by the no thinning scheme is the largest, and the errors gradually decreased after 48 h by WTMM.

- (4)

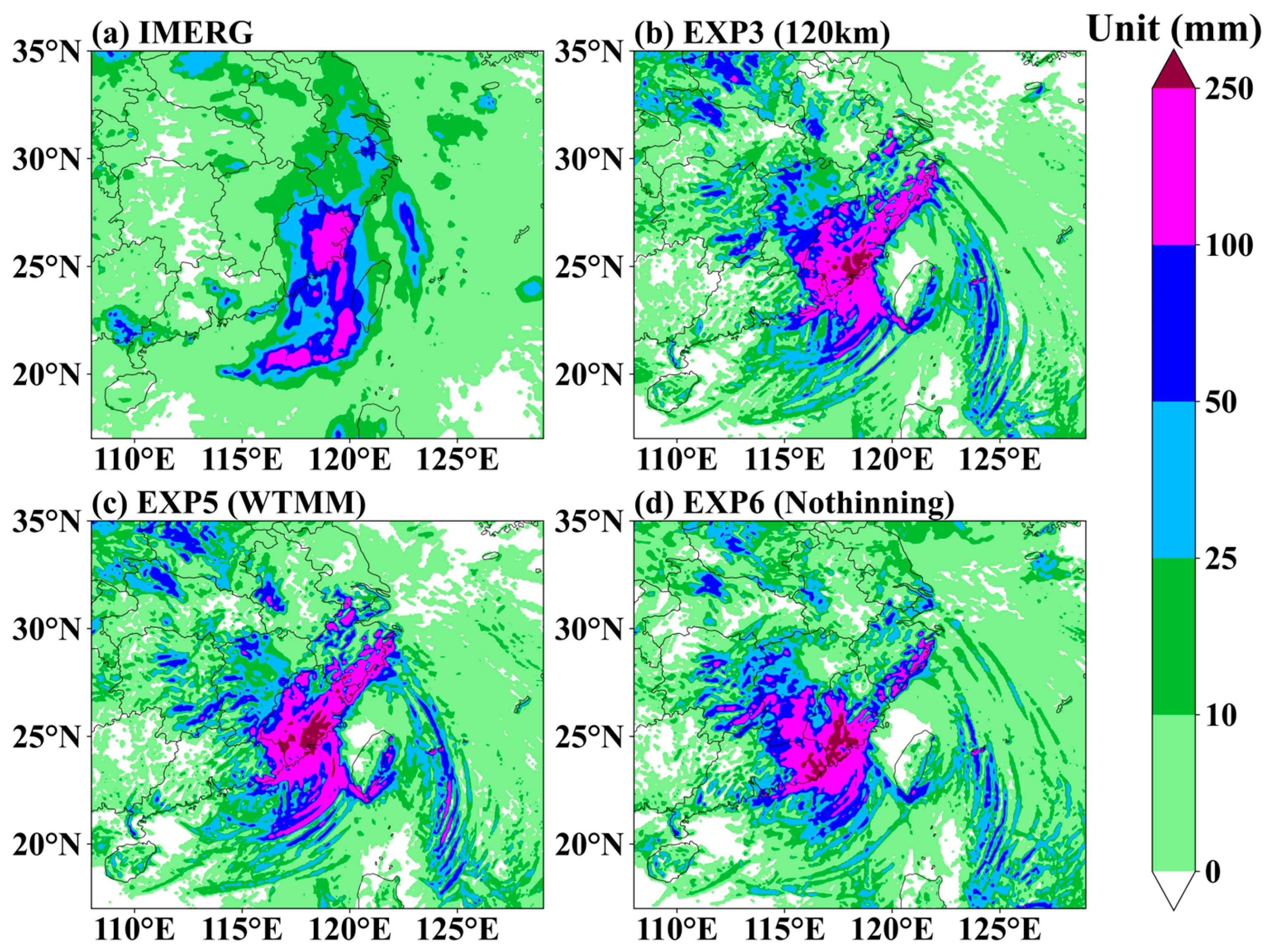

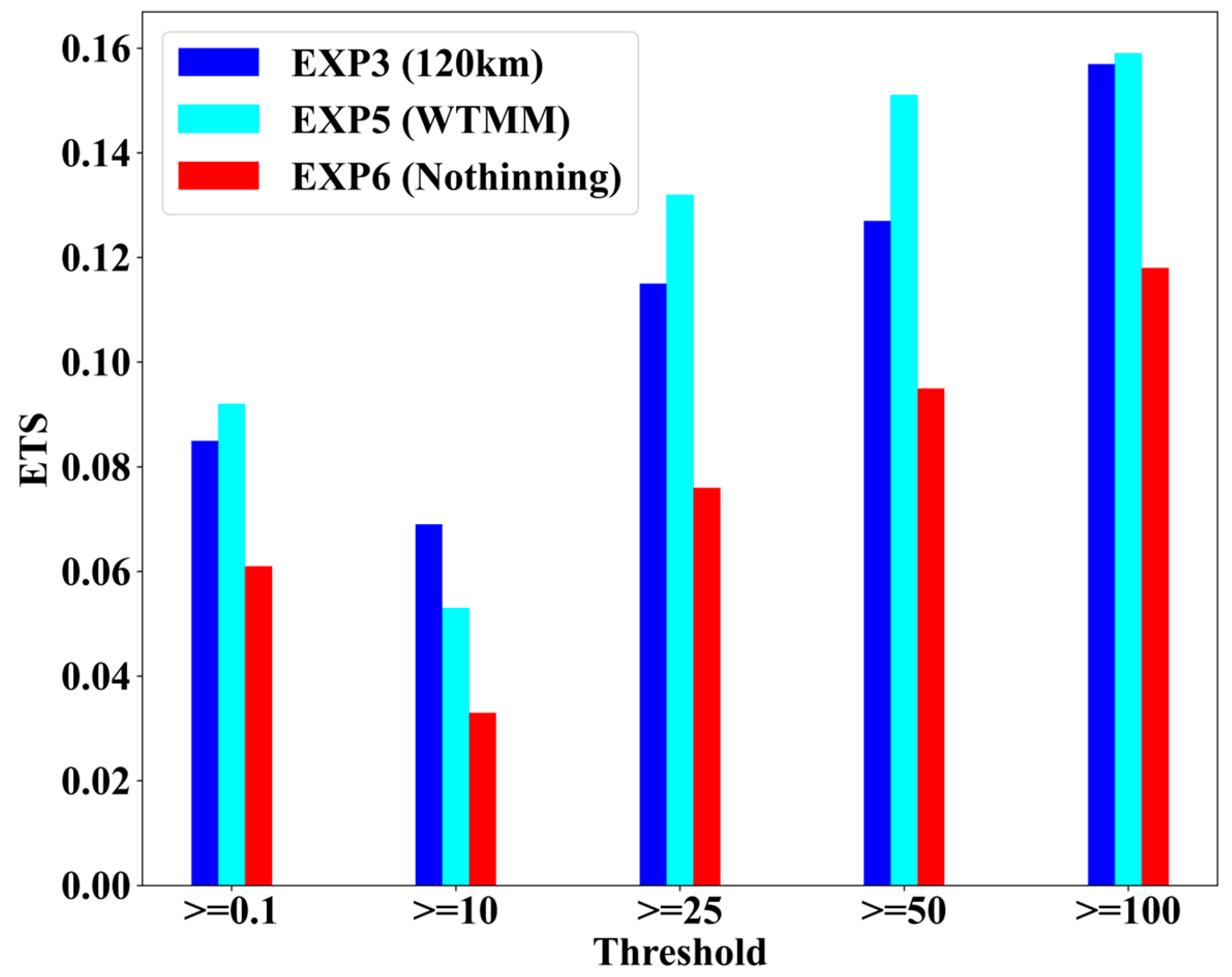

- The location of precipitation simulated by the no thinning scheme is more westward overall compared with the IMERG Final precipitation products and is improved after data thinning. Precipitation forecasts over land are all overestimated after typhoon landfall. The forecast accuracy of the locations and intensities of severe precipitation cores and the typhoon’s outer spiral rain bands over the South China Sea have been improved after data thinning. The Equitable Threat Scores (ETSs) of the WTMM thinning scheme are the highest for most precipitation intensity thresholds.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cardinali, C. Monitoring the observation impact on the short-range forecast. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2009, 135, 239–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNally, A.P.; Watts, P.D.; Smith, J.A.; Engelen, R.; Kelly, G.A.; Thépaut, J.N.; Matricardi, M. The assimilation of AIRS radiance data at ECMWF. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2006, 132, 935–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collard, A.D.; McNally, A.P. The assimilation of infrared atmospheric sounding interferometer radiances at ECMWF. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2009, 135, 1044–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNally, T.; Bonavita, M.; Thépaut, J.N. The role of satellite data in the forecasting of Hurricane Sandy. Mon. Weather Rev. 2014, 142, 634–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Liu, H. Improved hurricane track and intensity forecast using single field-of-view advanced IR sounding measurements. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2009, 36, L11813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Li, J.; Li, J.; Li, Z.; Schmit, T.J.; Bai, W. Advanced infrared sounder subpixel cloud detection with imagers and its impact on radiance assimilation in NWP. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2014, 41, 1773–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Liu, Z.; Huang, X.Y.; Min, J.; Wang, H. Impact of assimilating IASI radiance observations on forecasts of two tropical cyclones. Meteorol. Atmos. Phys. 2013, 122, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, W.; Yin, R.; Li, J.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; Li, Y.; Qin, X.; Zhang, Z.; Shen, X. Targeted sounding observations from geostationary satellite and impacts on high impact weather forecasts. Sci. China Earth Sci. 2025, 68, 963–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Min, M.; Li, J.; Sun, F.; Di, D.; Ai, Y.; Li, Z.; Qin, D.; Li, G.; Lin, Y.; et al. Local severe storm tracking and warning in pre-convection stage from the new generation geostationary weather satellite measurements. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Li, Z.; Li, J.; Schmit, T.J. Added-value of GEO-hyperspectral infrared radiances for local severe storm forecasts using the hybrid OSSE method. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 2021, 38, 1315–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.; Han, W.; Gao, Z.; Wang, G. A study on longwave infrared channel selection base on estimates of background errors and observation errors in the detection area of FY-4A. Acta Meteorol. Sin. 2019, 77, 898–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.; Han, W.; Gao, Z.; Di, D. The evaluation of FY4A’s Geostationary Interferometric Infrared Sounder (GIIRS) long-wave temperature sounding channels using the GRAPES global 4D-Var. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2020, 146, 1459–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.; Han, W.; Gao, Z.; Li, J. Impact of high temporal resolution FY-4A Geostationary Interferometric Infrared Sounder (GIIRS) radiance measurements on Typhoon forecasts: Maria (2018) case with GRAPES global 4D-Var assimilation system. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2021, 48, e2021GL093672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Niu, Z.; Weng, F.; Dong, P.; Huang, W.; Zhu, J. Impacts of direct assimilation of the FY-4A/GIIRS long-wave temperature Sounding Channel data on forecasting typhoon In-fa (2021). Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Q.; Li, D.; Yang, Y.; Ma, Y.; Pan, X.; Chen, M. Impact of assimilating atmospheric motion vectors from Himawari-8 and clear-sky radiance from FY-4A GIIRS on binary typhoons. Atmos. Res. 2023, 282, 106550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Huang, P.; Xu, N.; Li, J.; Di, D.; Zhang, Z.; Gao, L.; Ji, Z.; Min, M. Evaluating the first year on-orbit radiometric calibration performance of GIIRS onboard Fengyun-4B. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2024, 21, 1002905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Z.; Zhang, L.; Han, Y.; Dong, P.; Huang, W. Performances between the FY-4A/GIIRS and FY-4B/GIIRS long-wave infrared (LWIR) channels under clear-sky and all-sky conditions. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2023, 149, 1612–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Rabier, F. The potential of high-density observations for numerical weather prediction: A study with simulated observations. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. Spec. Issue 2003, 129, 3013–3035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran, R.; Li, X.; Movva, S.; Graves, S.; Greco, S.; Emmitt, D.; Terry, J.; Atlas, R. Intelligent data thinning algorithm for earth system numerical model research and application. In Proceedings of the 21st International Conference on Interactive Information Processing Systems (IIPS) for Meteorology, Oceanography, and Hydrology, San Diego, CA, USA, 9–13 January 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ochotta, T.; Gebhardt, C.; Saupe, D.; Wergen, W. Adaptive thinning of atmospheric observations in data assimilation with vector quantization and filtering methods. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2005, 131, 3427–3437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, S.; Splitt, M.; Lueken, M.; Zavodsky, B. Evaluation of data reduction algorithms for real-time analysis. Weather Forecast. 2010, 25, 837–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Zhang, H.; Yang, Y. Research progress of quality control for AIRS data. Adv. Earth Sci. 2017, 32, 139–150. Available online: http://www.adearth.ac.cn/CN/10.11867/j.issn.1001-8166.2017.02.0139 (accessed on 25 December 2025).

- Yin, R.; Han, W.; Wang, H.; Wang, J. Impacts of FY-4A GIIRS Water Vapor Channels Data Assimilation on the Forecast of “21· 7” Extreme Rainstorm in Henan, China with CMA-MESO. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 5710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huffman, G.J.; Bolvin, D.T.; Joyce, R.; Kelley, O.A.; Nelkin, E.J.; Tan, J.; Watters, D.C.; West, B.J. Integrated Multi-Satellite Retrievals for GPM (IMERG) Technical Documentation; IMERG: Boulder, CO, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman, R.N.; Alcala, C.; Leidner, S.M. Thinning Satellite Data Using Wavelets for Weather Forecasting. In Proceedings of the Earth Science Technology Conference, the University of Maryland Inn and Conference Center, College Park, MD, USA, 27–29 June 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Eyre, J.R.; Menzel, W.P. Retrieval of cloud parameters from satellite sounder data: A simulation study. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 1989, 28, 267–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yao, S.; Guan, L. Thinning Methods and Assimilation Applications for FY-4B/GIIRS Observations. Remote Sens. 2026, 18, 119. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010119

Yao S, Guan L. Thinning Methods and Assimilation Applications for FY-4B/GIIRS Observations. Remote Sensing. 2026; 18(1):119. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010119

Chicago/Turabian StyleYao, Shuhan, and Li Guan. 2026. "Thinning Methods and Assimilation Applications for FY-4B/GIIRS Observations" Remote Sensing 18, no. 1: 119. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010119

APA StyleYao, S., & Guan, L. (2026). Thinning Methods and Assimilation Applications for FY-4B/GIIRS Observations. Remote Sensing, 18(1), 119. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010119