Dynamic Changes and Sediment Reduction Effect of Terraces on the Loess Plateau

Highlights

- By combining remote sensing imaging principles with machine learning techniques, we produced 30 m terrace maps (1990–2020) for the Loess Platea, revealing significant spatiotemporal variations in terrace expansion.

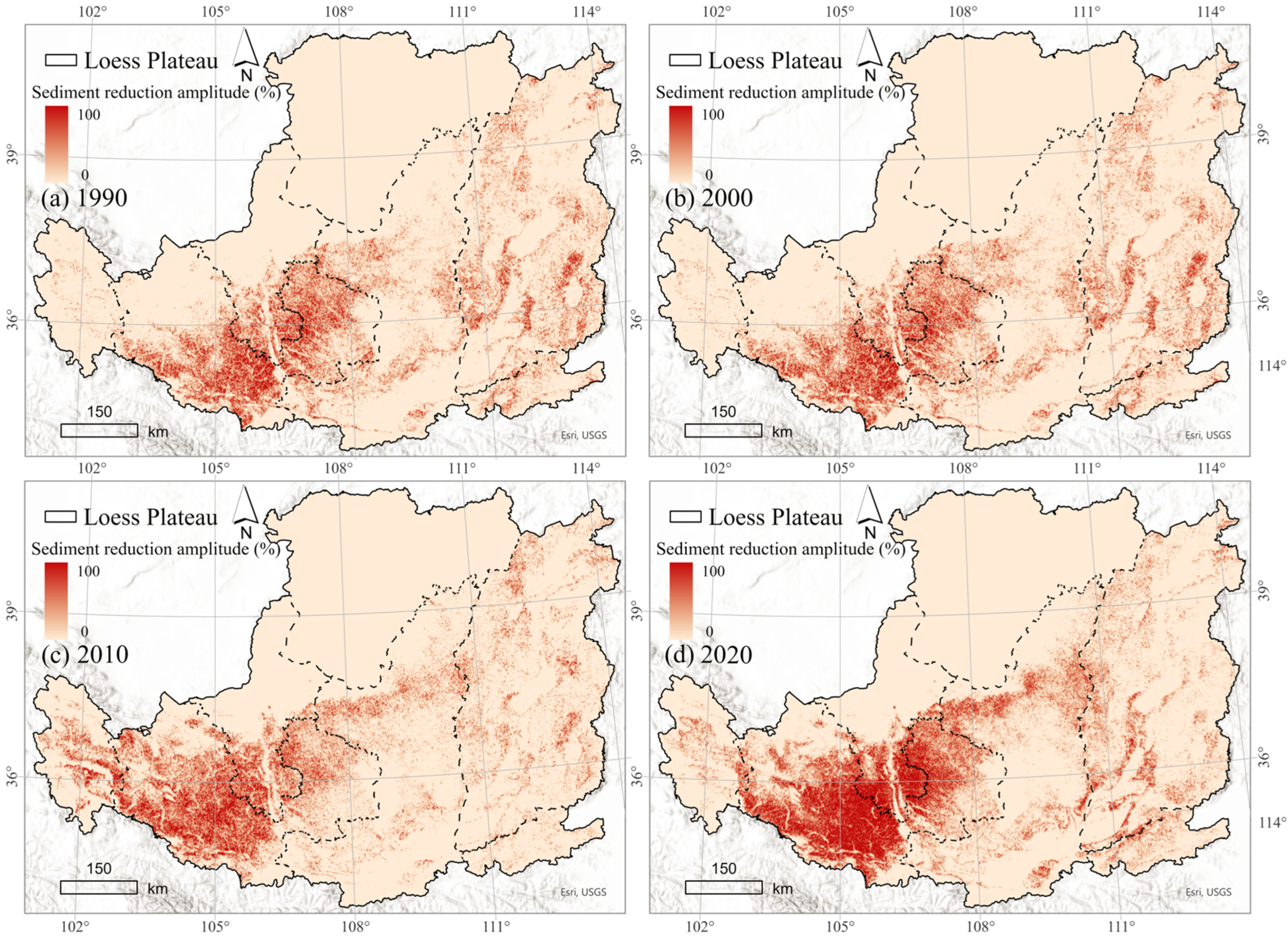

- We quantified the sediment reduction resulting from terrace construction, revealing an average 49.75% decrease in soil erosion across the Loess Plateau.

- This study provides a robust framework for long-term monitoring of terrace dynamics, thereby offering a scientific basis for precision terrace management and sustainable land-use planning on the Loess Plateau.

- This study demonstrates the critical role of terrace engineering in soil and water conservation, providing quantitative evidence to support the optimization of erosion control and agricultural productivity strategies on the Loess Plateau.

Abstract

1. Introduction

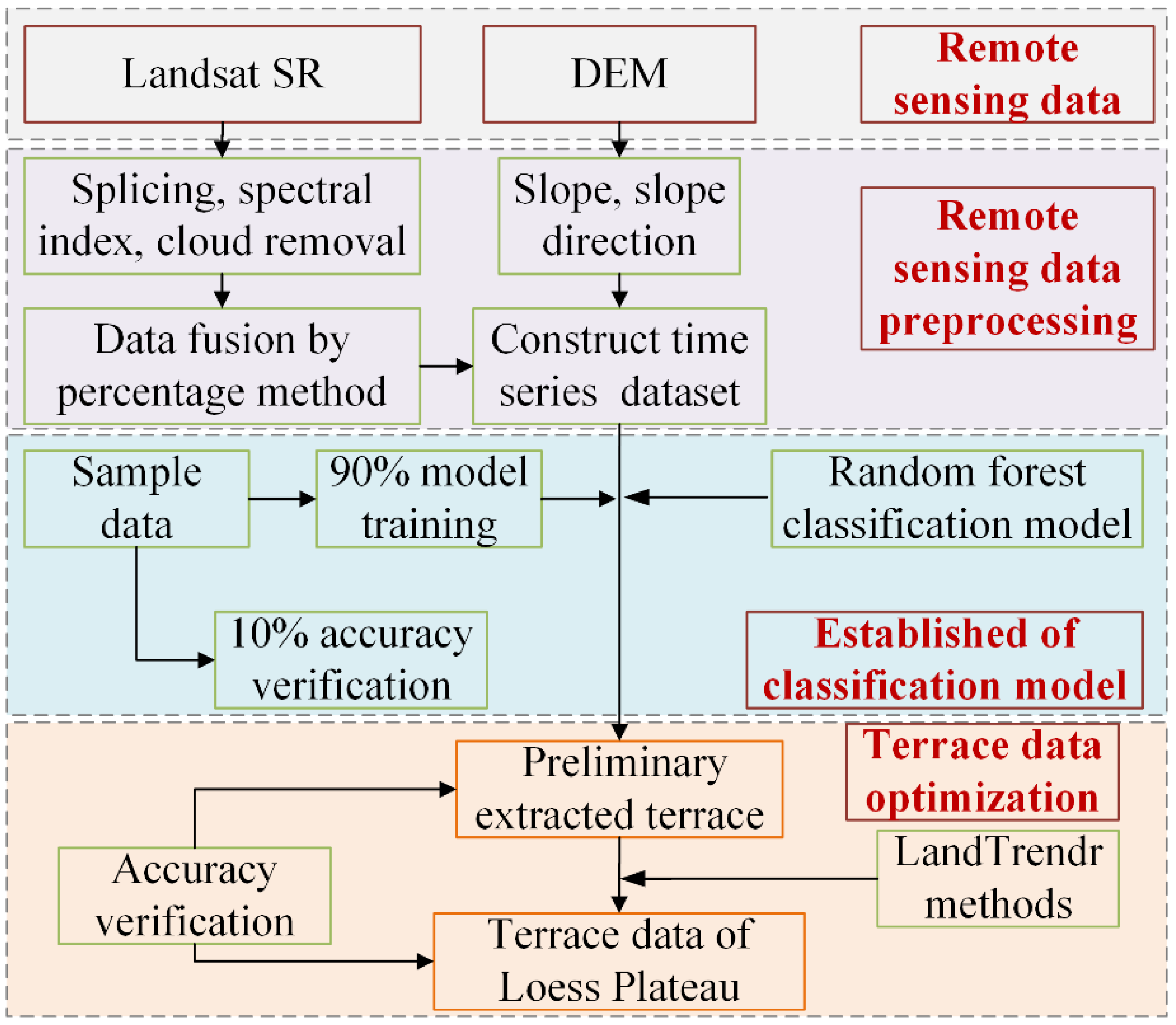

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Sources

2.2.1. Landsat Imagery

2.2.2. Sample Data

2.2.3. Slope Data Based on DEM

2.3. Methods

2.3.1. Spectral Index Selection

2.3.2. Machine Learning

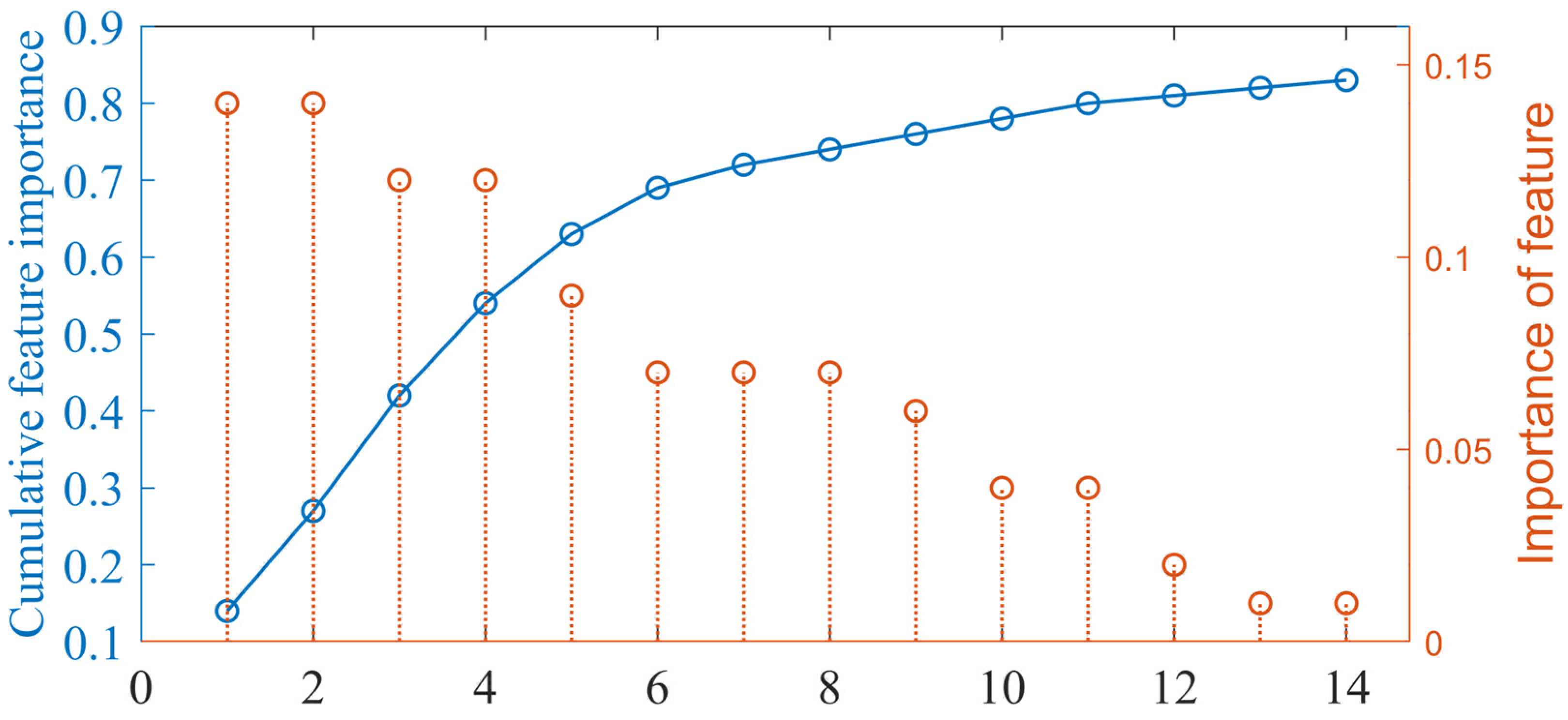

2.3.3. Calculation of Feature Importance

2.3.4. LandTrendr Algorithm and Result Optimization

2.3.5. Accuracy Analysis

2.4. Terrace Sediment Reduction Effect Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Model Parameter Construction and Accuracy Evaluation

3.1.1. Feature Importance

3.1.2. Accuracy Evaluation

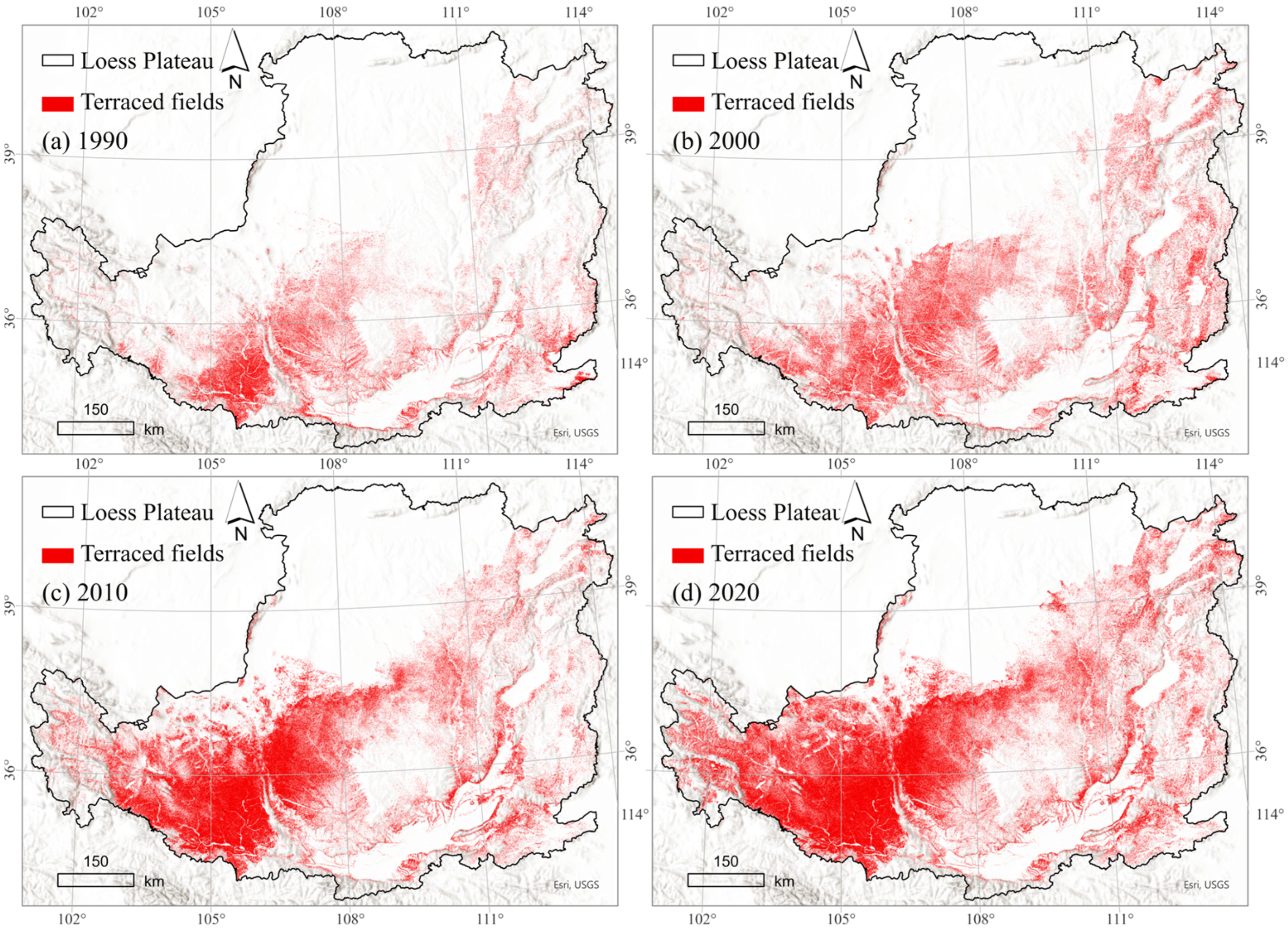

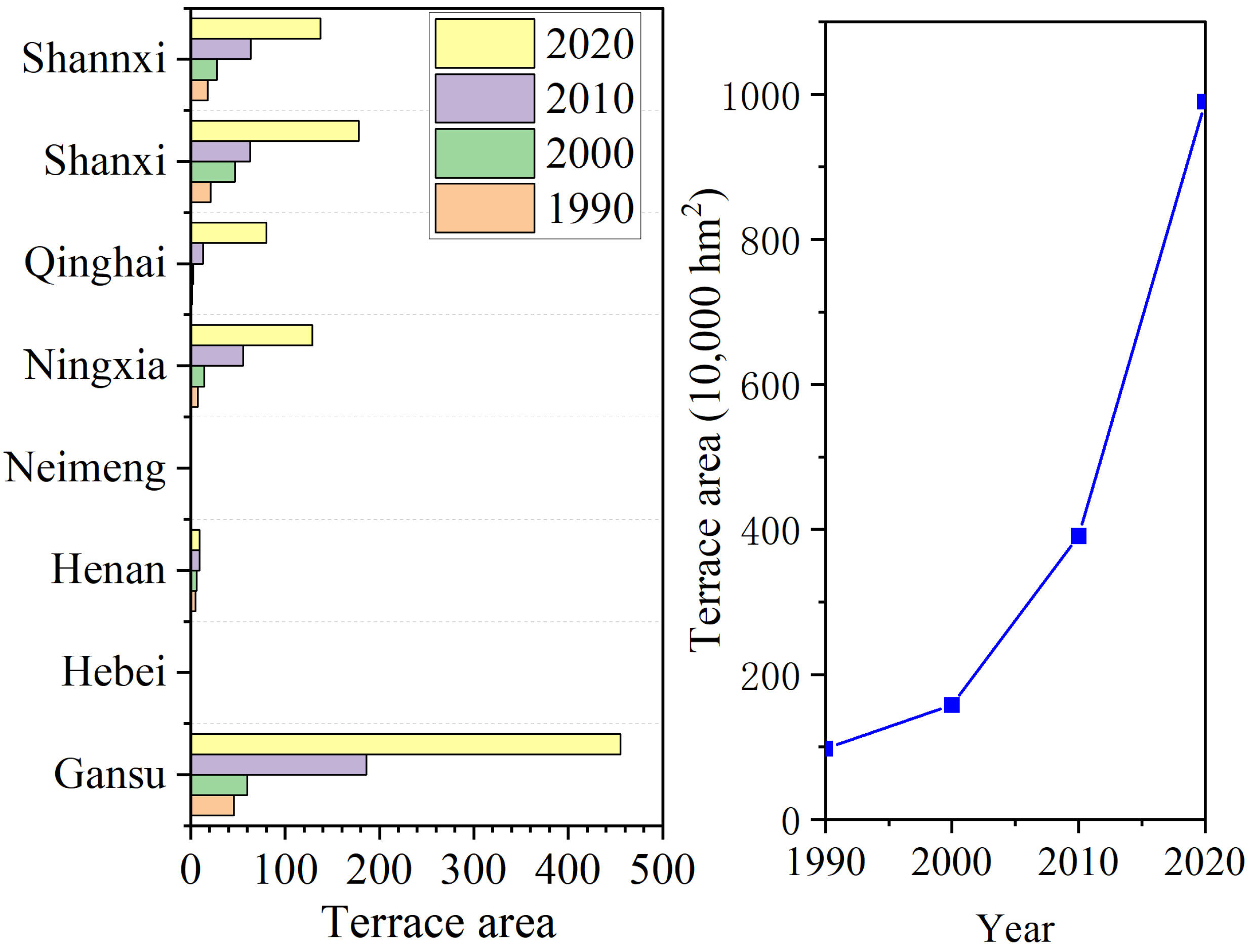

3.2. Terrace Area Change Trends over the Past 30 Years

3.3. Sediment Reduction Effect of Terraces on the Loess Plateau over the Past 30 Years

4. Discussion

4.1. Uncertainty in Long-Term Terrace Monitoring Methods

4.2. Key Findings on Terrace Expansion and Its Environmental Efficacy

4.3. Uncertainty in Quantitative Study of Terrace Sediment Reduction Effects

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- Elevation (Ele.), Red band (R), Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI), Enhanced Vegetation Index (EVI), and NIRv are the key parameters for remote sensing identification of terraces. These five remote sensing variables can explain 88% of the terrace identification variables. Additionally, coupling the Random Forest classification model with the LandTrendr algorithm enables fast time-series mapping of terrace spatial distribution characteristics on the Loess Plateau. The producer’s accuracy for terrace identification is 93.49%, user’s accuracy is 93.81%, overall accuracy is 88.61%, and the Kappa coefficient is 0.87. The LandTrendr algorithm effectively removes terraces impacted by human activities.

- (2)

- Terraces are mainly distributed in the Loess regions of the southeastern part of the plateau, including provinces such as Gansu, Shaanxi, and Ningxia. Between 1990 and 2020, the overall area of terraces showed an increasing trend, from 0.979 million hectares in 1990 to 9.8981 million hectares in 2020. However, the changes vary significantly across different provinces. For example, in Gansu Province, the area increased dramatically between 2010 and 2020, from 1.8617 million hectares in 2010 to 4.5546 million hectares in 2020.

- (3)

- The average sediment reduction across the region is 49.75%, demonstrating that terraces are a key measure for regional soil and water conservation and a crucial approach to enhancing the quality and productivity of arable land. The data provided by this study offers scientific evidence for soil erosion control in the Loess Plateau region and improves the precision of terrace management.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dorren, L.; Rey, F. A review of the effect of terracing on erosion. In Briefing Papers of the 2nd Scape Workshop; Boix-Fayons, C., Imeson, A., Eds.; SCAPE: Cinque Terre, Italy, 2004; pp. 97–108. [Google Scholar]

- Hammad, A.H.A.; Brresen, T.; Haugen, L.E. Effects of rain characteristics and terracing on runoff and erosion under the Mediterranean. Soil Tillage Res. 2006, 87, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.G.; Rui, X.P.; Xie, W.Y.; Xu, X.J.; Wei, W. Research on automatic identification method of terraces on the Loess Plateau Based on deep transfer learning. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 2446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pijl, A.; Wang, W.D.; Straffelini, E.; Tarolli, P. Soil and water conservation in terraced and non–terraced cultivations—A massive comparison of 50 vineyards. Land Degrad. Dev. 2021, 33, 596–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.P.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, J.; Rustomji, P.; Hairsine, P. Responses of streamflow to changes in climate and land use/cover in the Loess Plateau, China. Water Resour. Res. 2008, 44, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Fu, B.J.; Piao, S.L.; Lü, Y.H.; Ciais, P.; Feng, X.M.; Wang, Y.F. Reduced sediment transport in the Yellow River due to anthropogenic changes. Nat. Geosci. 2016, 9, 38–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, L.Y.; Tang, G.A.; Yang, X.; Li, F.Y. Geomorphology–oriented digital terrain analysis: Progress and perspectives. J. Geogr. Sci. 2021, 76, 595–611. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.Q.; Fang, X.; Ding, H.; Josef, S.; Xiong, L.Y.; Na, J.M.; Tang, G.A. Extraction of terraces on the Loess Plateau from high–resolution dems and imagery utilizing object–based image analysis. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2017, 6, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pijl, A.; Quarella, E.; Vogel, T.A.; D’Agostino, V.; Tarolli, P. Remote sensing vs. field–based monitoring of agricultural terrace degradation. Int. Soil Water Conserv. Res. 2021, 9, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Q.; Yu, X.X.; Wang, W.; Xu, M.M.; Ren, R.; Zhang, J.P. Effect of terracing project on temporal–spatial variation of non–point source pollution load in Hujiashan watershed, China. Chin. J. Appl. Ecol. 2017, 28, 1344–1351. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Q.; Chen, Y.; Brêda, J.P.L.; Cui, H.; Duan, H.; Huang, C. Higher-density river discharge observation through integration of multiple satellite data: Midstream yellow river, china. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2025, 137, 104433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez–Casasnovas, J.A.; Ramos, M.C.; Cots–Folch, R. Influence of the EU CAP on terrain morphology and vineyard cultivation in the Priorat region of NE Spain. Land Use Policy 2010, 27, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnoletti, M.; Cargnello, G.; Gardin, L.; Santoro, A.; Bazzoffi, P.; Sansone, L.; Pezza, L.; Belfiore, N. Traditional landscape and rural development: Comparative study in three terraced areas in northern, central and southern Italy to evaluate the efficacy of GAEC standard 4.4 of cross compliance. Ital. J. Agron. 2011, 6, 121–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.Y.; Ma, N.; Yang, J.; Li, Z.H.; Wang, Q.X. Extracting features of soil and water conservation measures from remote sensing images of different resolution levels: Accuracy analysis. Bull. Soil Water Conserv. 2012, 32, 154–157. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Deng, C.X.; Zhang, G.Y.; Liu, Y.J.; Nie, X.D.; Li, Z.W.; Liu, J.Y.; Zhu, D.M. Advantages and disadvantages of terracing: A comprehensive review. Int. Soil Water Conse. Res. 2021, 9, 344–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Wei, W.; Chen, L. Effects of terracing practices on water erosion control in China: A meta-analysis. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2017, 173, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Wei, W.; Pan, D.L. Effects of rainfall and terracing-vegetation combinations on water erosion in a loess hilly area, China. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 261, 110247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, P.; Tian, X.J.; Geng, R.; Zhao, G.J.; Yang, L.; Mu, X.M.; Gao, P.; Sun, W.Y.; Liu, Y.L. Response of soil erosion to vegetation restoration and terracing on the Loess Plateau. Catena 2023, 227, 107103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekuriaw, A.; Heinimann, A.; Zeleke, G.; Hurni, H.; Hurni, K. An automated method for mapping physical soil and water conservation structures on cultivated land using GIS and remote sensing techniques. J. Geog. Sci. 2017, 27, 79–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.L.; Zhou, J.; Tan, M.L.; Lu, P.D.; Xue, Z.H.; Liu, M.Y.; Wang, X.P. Impacts of vegetation restoration on soil erosion in the Yellow River Basin, China. Catena 2024, 234, 107547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.H.; He, B.L.; Li, Z.X.; Zhang, J.L.; Wang, L.; Wang, Z. Influence of land terracing on agricultural and ecological environment in the loess plateau regions of China. Environ. Earth Sci. 2011, 62, 797–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fensholt, R.; Sandholt, I.; Rasmussen, M.S. Evaluation of MODIS LAI, fAPAR and the relation between fAPAR and NDVI in a semi–arid environment using in situ measurements. Remote Sens. Environ. 2004, 91, 490–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakamoto, T.; Yokozawa, M.; Toritani, H.; Shibayama, M.; Ishitsuka, N.; Ohno, H. A crop phenology detection method using time–series MODIS data. Remote Sens. Environ. 2005, 96, 366–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haboudane, D.; Miller, J.R.; Pattey, E.; Zarco-Tejada, P.J.; Strachan, I.B. Hyperspectral vegetation indices and novel algorithms for predicting green LAI of crop canopies: Modeling and validation in the context of precision agriculture. Remote Sens. Environ. 2004, 90, 337–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, T.J.; Chen, D.Y.; Cosh, M.; Li, F.Q.; Anderson, M.; Walthall, C.; Doriaswamy, P.; Hunt, E.R. Vegetation water content mapping using Landsat data derived normalized difference water index for corn and soybeans. Remote Sens. Environ. 2004, 92, 475–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFEETERS, S.K. The use of the Normalized Difference Water Index (NDWI) in the delineation of open water features. Int. J. Remote Sens. 1996, 17, 1425–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, L.; Ryu, Y.; Dechant, B.; Hwang, Y.; Feng, H.; Kang, Y.H.; Jeong, S.; Lee, J.; Choi, C.; Bae, J. Correcting confounding canopy structure, biochemistry and soil background effects improves leaf area index estimates across diverse ecosystems from Sentinel–2 imagery. Remote Sens. Environ. 2024, 309, 114224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briem, G.J.; Benediktsson, J.A.; Sveinsson, J.R. Multiple classifiers applied to multisource remote sensing data. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote. Sens. 2002, 40, 2291–2299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanski, J.; Mack, B.; Björn, W. Optimization of object–based image analysis with random forests for land cover mapping. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2013, 6, 2492–2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, R.E.; Yang, Z.Q.; Cohen, W.B. Detecting trends in forest disturbance and recovery using yearly Landsat time series: 1. LandTrendr–Temporal segmentation algorithms. Remote Sens. Environ. 2010, 114, 2897–2910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen, Z.; Quackenbush, L.J.; Stehman, S.V.; Zhang, L.J. Impact of training and validation sample selection on classification accuracy and accuracy assessment when using reference polygons in object–based classification. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2013, 34, 6914–6930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.Y.; Yang, S.T.; Wang, F.G.; He, X.Z.; Ma, H.B.; Luo, Y. Analysis on sediment yield reduced by current terrace and shrubs–Herbs–Arbor Vegetation in the Loess Plateau. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2014, 45, 1293–1300. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Lu, D.; Su, K.C.; Wang, Z.P.; Hou, M.J.; Li, X.X.; Lin, A.W.; Yang, Q.Y. Patterns and drivers of terrace abandonment in China: Monitoring based on multi-source remote sensing data. Land Use Policy 2025, 148, 107388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Shi, M.C.; Zhao, X.; Wang, X.J.; Luo, Z.D.; Zhao, Y. Methods for automatic identification and extraction of terraces from high spatial resolution satellite data (China-GF-1). Int. Soil Water Conse. Res. 2017, 5, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Guo, X.F.; Han, J.Q.; Sun, P.C. Preliminary estimation of soil carbon sequestration benefits of terrace construction on the Loess Plateau in the past nearly 40 years. J. Soil Water Conserv. 2024, 38, 190–197. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, B.W.; Yu, L.; Victoria, V.; Philippe, C.; Li, W.; Zhao, Y.Y.; Wei, W.; Chen, D.; Liu, Z.; Gong, P. A 30-m terrace mapping in China using Landsat8 imagery and digital elevation model based on the Google Earth Engine. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2021, 13, 2437–2456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slámová, M.; Krcmarova, J.; Hroncek, P.; Kastierova, M. Environmental factors influencing the distribution of agricultural terraces: Case study of Horny Tisovnik, Slovakia. Morav. Geogr. Rep. 2017, 25, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Spectral Index | Abbreviation | Equation | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normalized Difference Vegetation index | NDVI | (NIR − R)/(NIR + R) | [22] |

| Enhanced Vegetation Index | EVI | 2.5 × (NIR − R)/(NIR + 6 × R − 0.75 × B + 1) | [23] |

| Normalized Difference Built-up Index | NDBI | (SWIR − NIR)/(SWIR + NIR) | [24] |

| Normalized Difference Moisture Index | NDMI | (NIR − SWIR)/(NIR + SWIR) | [25] |

| Normalized Difference Water Index | NDWI | (G − NIR)/(G + NIR) | [26] |

| Near-infrared Reflectance of Vegetation | NIRv | (NIR − R)/(NIR + R) × NIR | [27] |

| Year | PA (%) | OA (%) | UA (%) | Kappa | P | Re | F1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1990 | 93.23 | 88.02 | 94.01 | 0.88 | 0.81 | 0.74 | 0.77 |

| 2000 | 93.13 | 87.92 | 93.91 | 0.86 | 0.82 | 0.72 | 0.76 |

| 2010 | 92.37 | 87.35 | 92.98 | 0.82 | 0.86 | 0.78 | 0.82 |

| 2020 | 95.21 | 91.12 | 94.32 | 0.90 | 0.87 | 0.83 | 0.85 |

| Mean | 93.49 | 88.61 | 93.81 | 0.87 | 0.84 | 0.76 | 0.80 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, C.; Wang, X.; Fu, X.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y. Dynamic Changes and Sediment Reduction Effect of Terraces on the Loess Plateau. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 4021. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17244021

Wang C, Wang X, Fu X, Zhang X, Wang Y. Dynamic Changes and Sediment Reduction Effect of Terraces on the Loess Plateau. Remote Sensing. 2025; 17(24):4021. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17244021

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Chenfeng, Xiaoping Wang, Xudong Fu, Xiaoming Zhang, and Yunqi Wang. 2025. "Dynamic Changes and Sediment Reduction Effect of Terraces on the Loess Plateau" Remote Sensing 17, no. 24: 4021. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17244021

APA StyleWang, C., Wang, X., Fu, X., Zhang, X., & Wang, Y. (2025). Dynamic Changes and Sediment Reduction Effect of Terraces on the Loess Plateau. Remote Sensing, 17(24), 4021. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17244021