Research on Multi-Source Precipitation Fusion Based on Classification and Regression Machine Learning Methods—A Case Study of the Min River Basin in the Eastern Source of the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau

Highlights

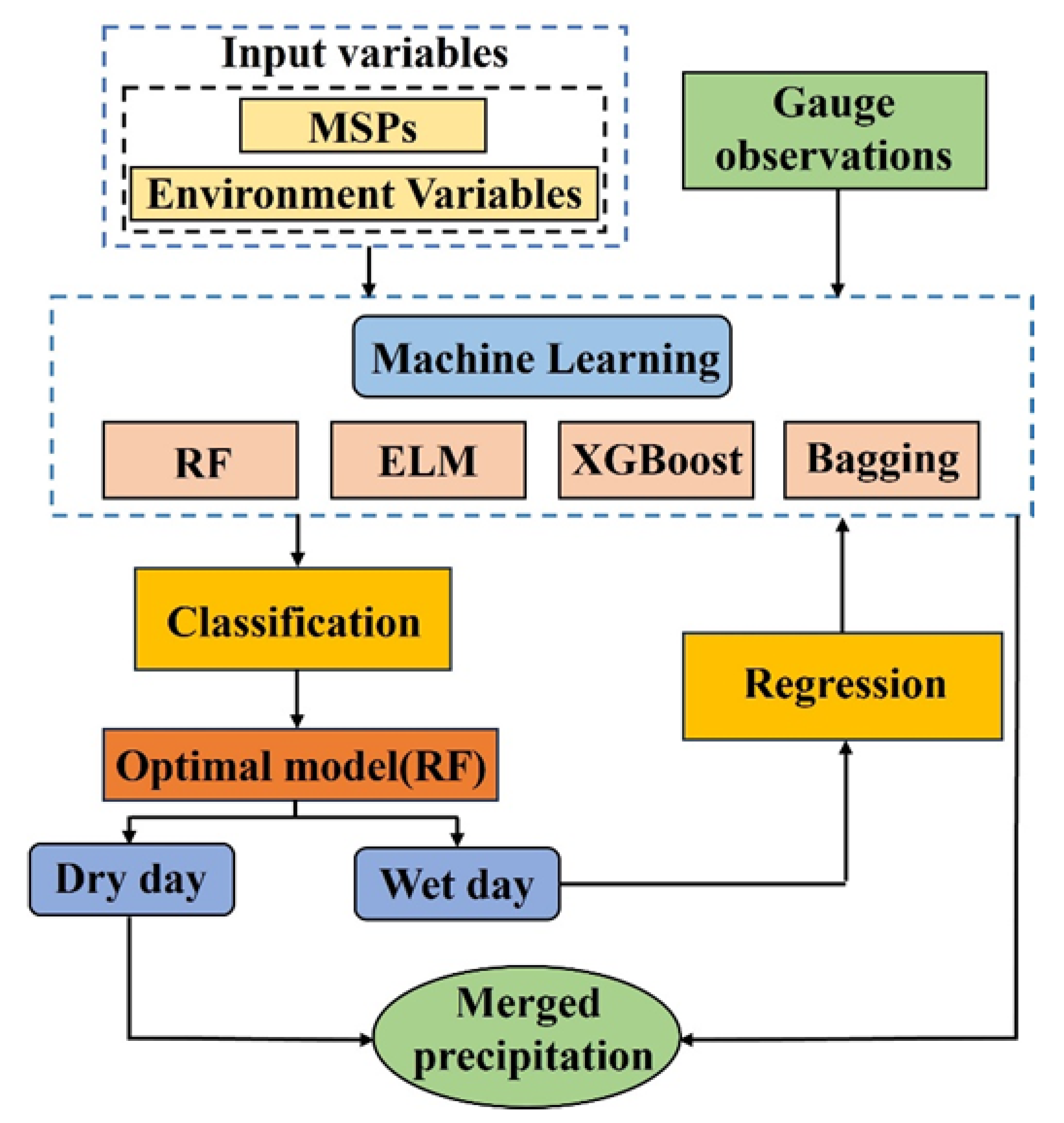

- A two-step machine learning fusion framework integrating precipitation event identification and quantitative intensity estimation is proposed, addressing the inaccuracy of satellite precipitation products in complex terrain like the MRB.

- Double Machine Learning (DML) models outperform Single Machine Learning (SML) models and original products, with RF-Bagging being the optimal model—daily-scale Correlation Coefficient (CC) is over 50% higher than original data, while RMSE and MAE are reduced by more than 40% and 35%, respectively.

- RF-Bagging and RF-RF models exhibit strong stability: Critical Success Index (CSI) remains stable at ~0.7 under moderate-to-heavy precipitation, and Probability of Detection (POD) approaches 1 in high-altitude areas of the MRB.

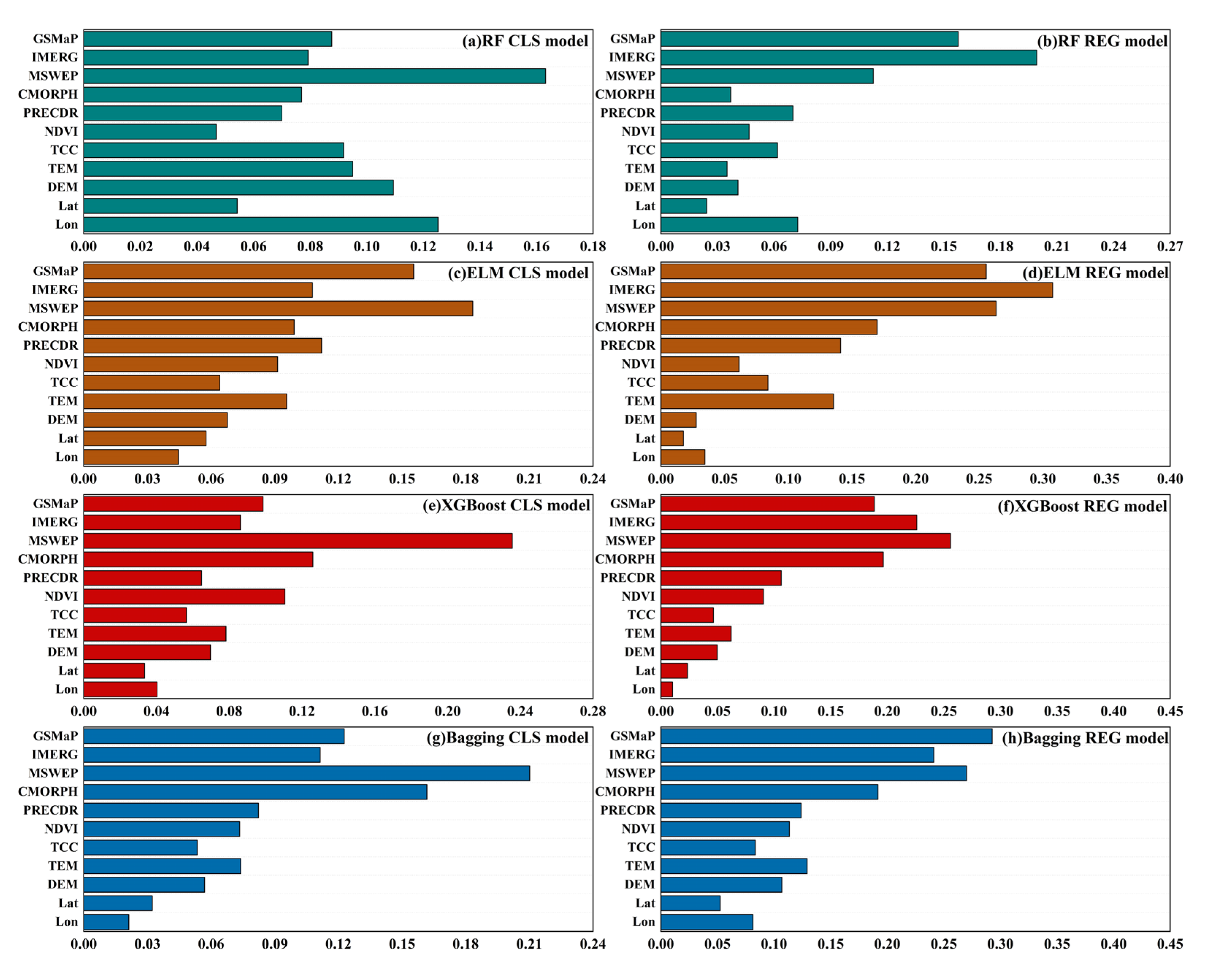

- GSMaP, IMERG, and MSWEP serve as core input variables for all models; RF/ELM rely more on environmental variables (NDVI, TCC, DEM), while XGBoost/Bagging depend more on satellite precipitation data, reflecting distinct variable sensitivity characteristics.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

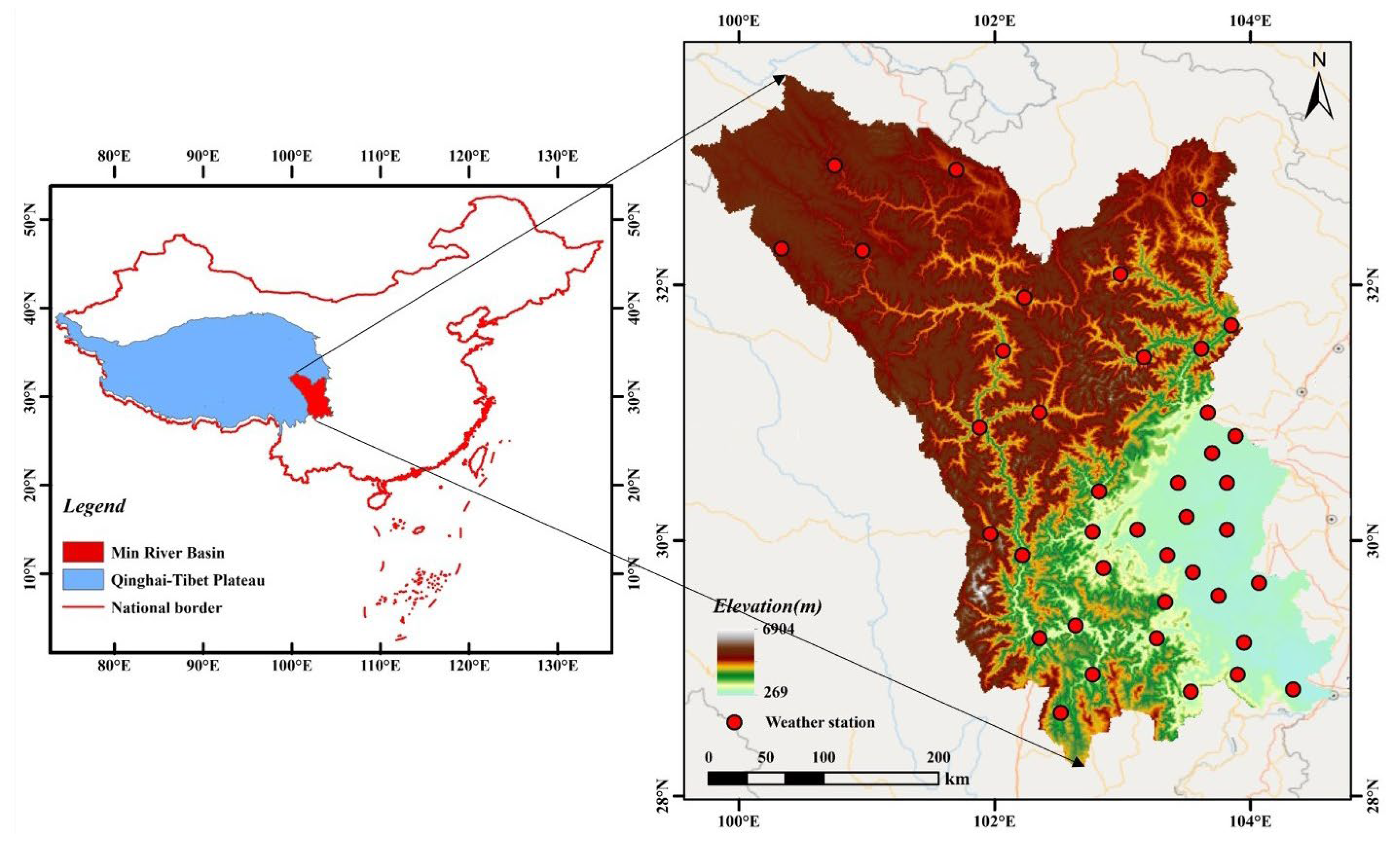

2.1. Materials

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Data Preprocessing

2.2.2. Fusion Method

2.2.3. RF

2.2.4. ELM

2.2.5. XGBoost

2.2.6. Bagging

2.2.7. Model Validation

3. Results

3.1. Applicability Evaluation in Daily Scale Identification and Quantitative Estimation

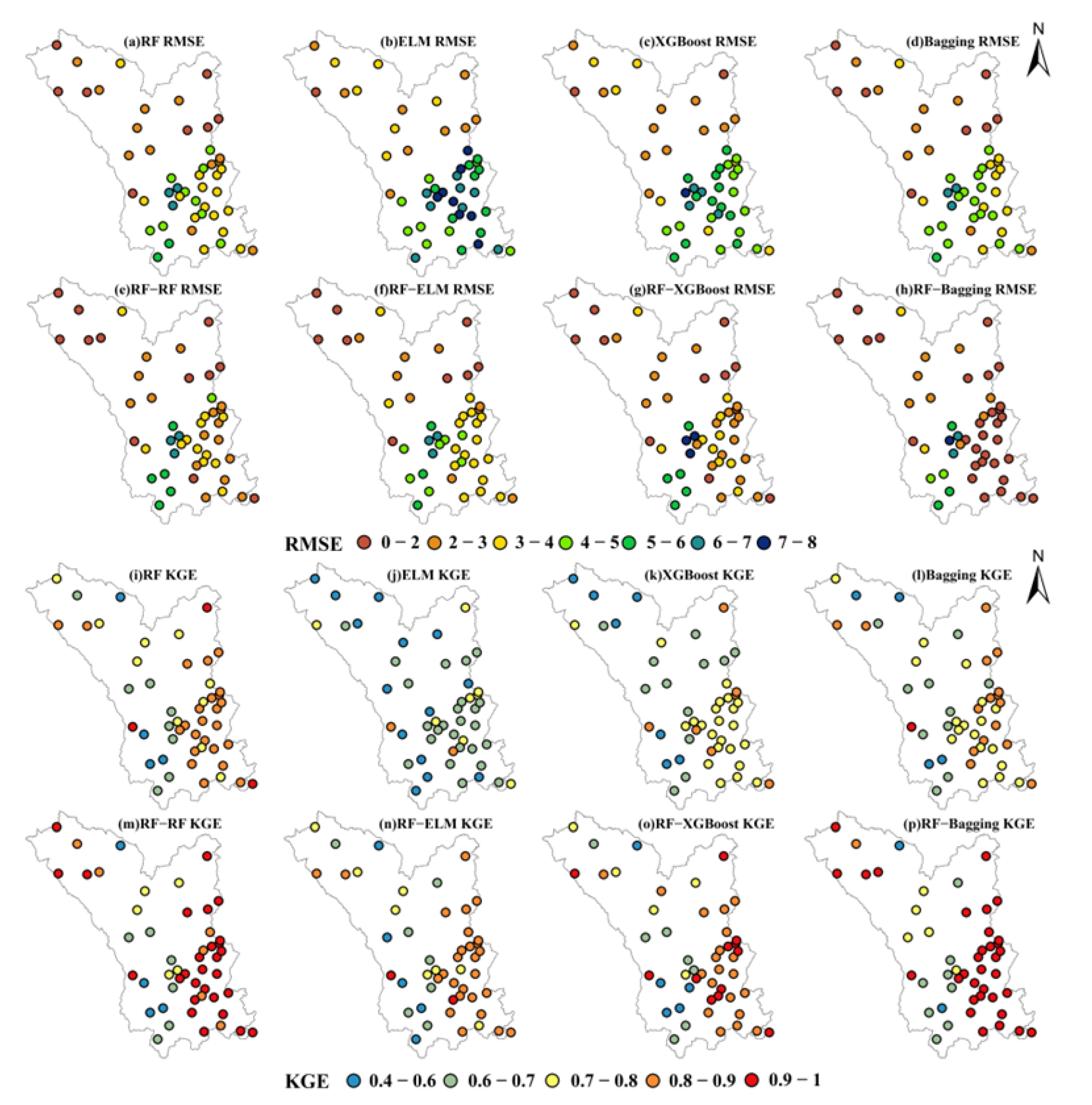

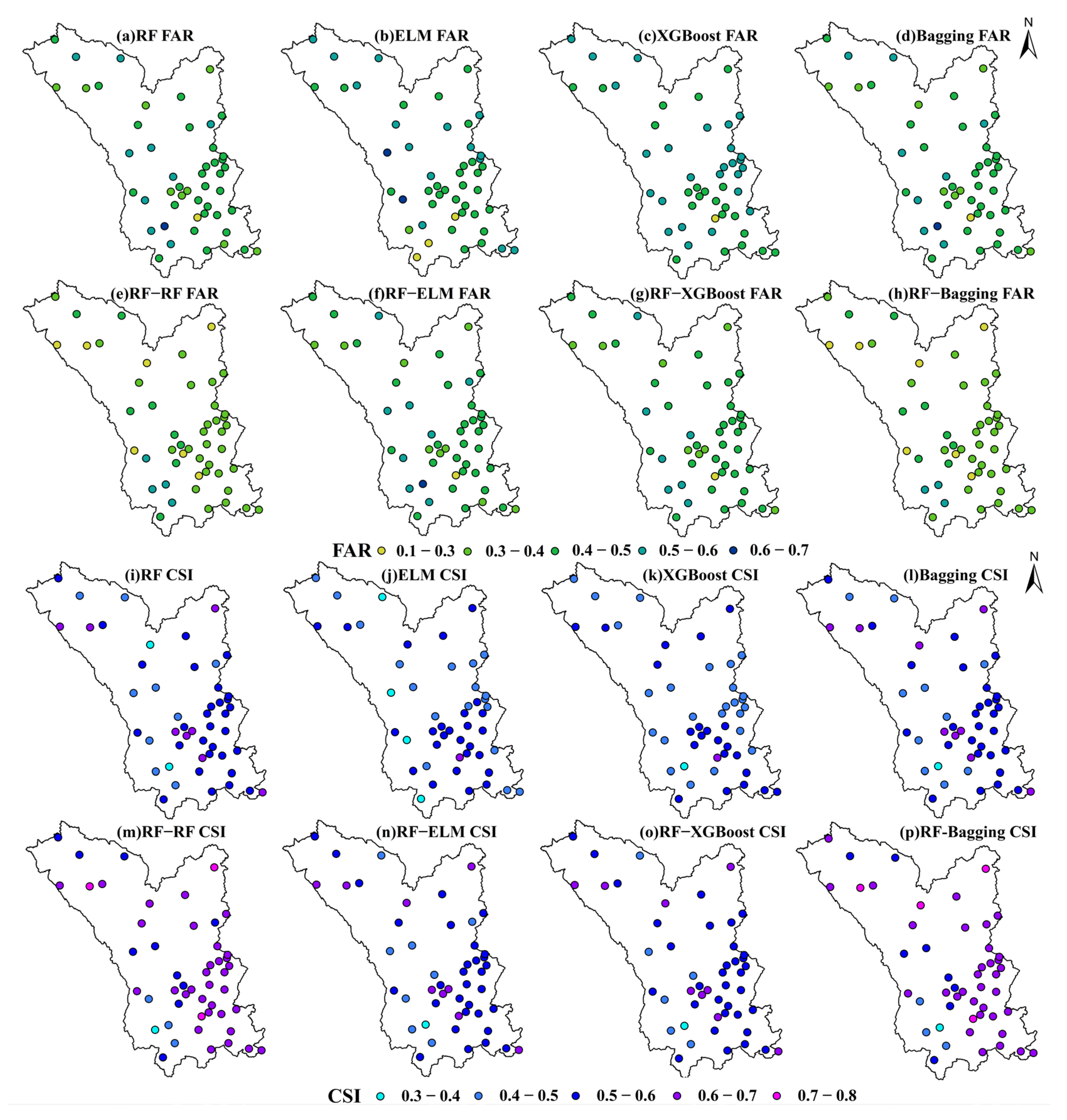

3.2. Evaluation of Spatial Distribution Identification and Estimation Performance at the Daily Scale

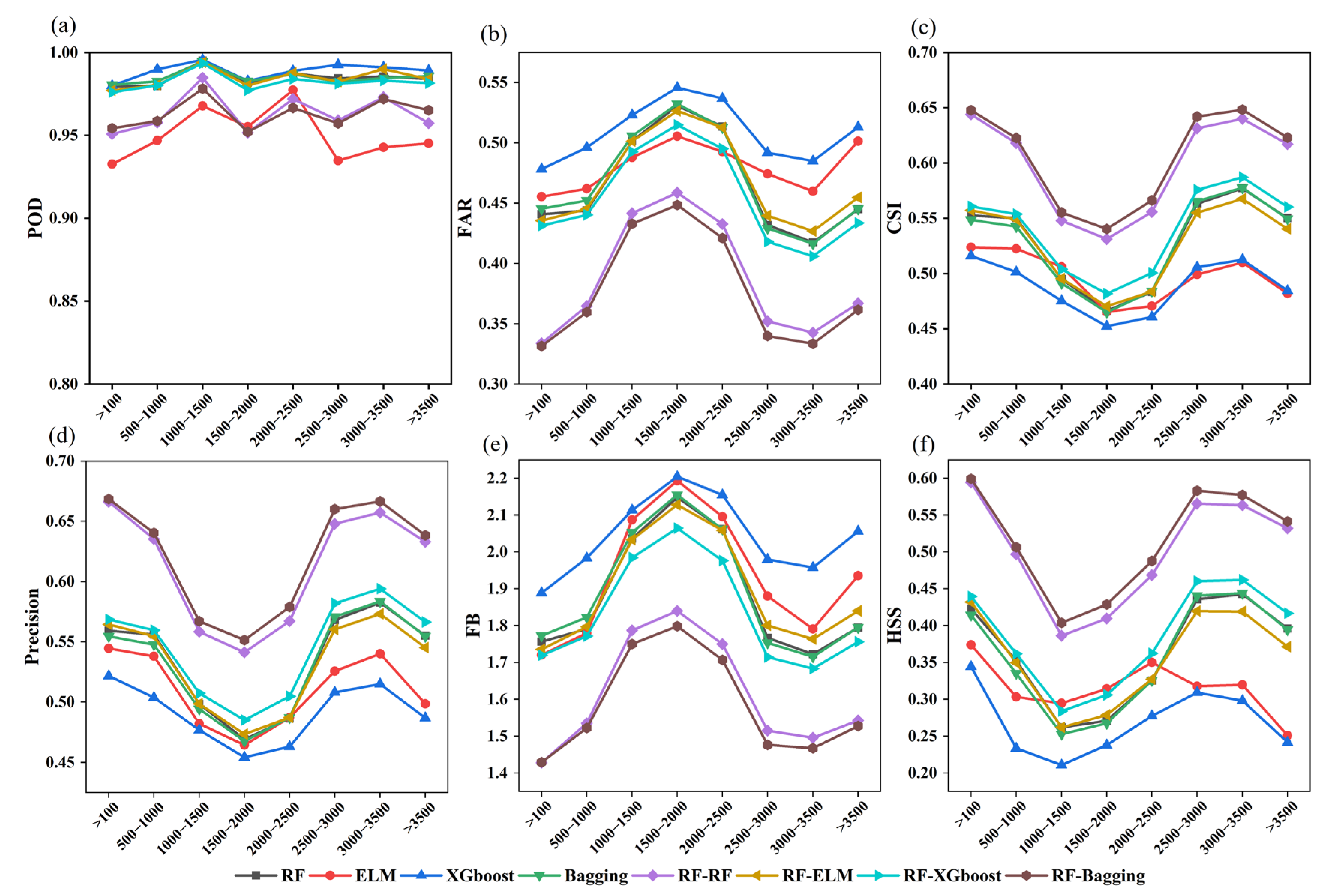

3.3. Performance Characteristics Across Different Precipitation Intensities and Elevation Conditions

3.4. Variable Importance of Precipitation Fusion Algorithms

4. Discussion

4.1. Advantages of Machine Learning Based Multi-Source Precipitation Fusion Frameworks

4.2. Spatial Heterogeneity of Model Performance Under Different Scenarios and Driving Mechanisms

4.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

5. Conclusions

- Significant application impacts have been attained by the suggested two-step fusion architecture of precipitation event identification-intensity quantitative estimate. The DML models stand out among them, with the RF-Bagging model exhibiting the best estimation accuracy—the daily-scale CC is more than 50% higher than the original precipitation products, and the RMSE and MAE are reduced by more than 40% and 35%, respectively, indicating notable improvements in accuracy and error control.

- The performance of DML models varies significantly in space. The higher and lower reaches of the basin are where the RF-Bagging and RF-RF models function best; however, mid-altitude regions see a minor decline in model performance due to complicated topography and cloud interference. For better estimation stability in the future, targeted optimization for this area’s features is needed.

- The CSI for moderate-to-heavy rainfall is consistently maintained at about 0.7, demonstrating the RF-Bagging and RF-RF models’ high flexibility in precipitation estimate by intensity. The FAR and CSI of these two models are still better than those of other models such as ELM and single XGBoost, making them more dependable in heavy precipitation event estimation even if underestimating still occurs in heavy precipitation situations.

- Forecasting models perform most effectively in high-altitude regions, where the precipitation frequency forecast accuracy is high and the POD is close to 1. Additionally, the HSS is 30–40% greater than that in the middle altitude regions, which has exceptional application in complicated high altitude settings and can effectively adapt to the precipitation estimate requirements of the high altitude terrain on the eastern side of the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau.

- Three categories of satellite precipitation data are essential input variables that significantly affect the estimation outcomes of all models, according to variable importance analysis. From the standpoint of individual models, there are clear differences in the features of variable dependence: XGBoost and Bagging models rely more on satellite precipitation data, whilst RF and ELM models are more dependent on environmental factors like NDVI and DEM.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Belabid, N.; Zhao, F.; Brocca, L.; Huang, Y.; Tan, Y. Near-real-time flood forecasting based on satellite precipitation products. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, R.B.; Carpenter, S.R.; Dahm, C.N.; McKnight, D.M.; Naiman, R.J.; Postel, S.L.; Running, S.W. Water in a changing world. Ecol. Appl. 2001, 11, 1027–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidd, C.; Bauer, P.; Turk, J.; Huffman, G.J.; Joyce, R.; Hsu, K.L.; Braithwaite, D. Intercomparison of high-resolution precipitation products over northwest Europe. J. Hydrometeorol. 2012, 13, 67–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Wei, J.; Zhang, H.; Xu, Y.; Qin, H. Spatiotemporal deep learning rainfall-runoff forecasting combined with remote sensing precipitation products in large scale basins. J. Hydrol. 2023, 616, 128727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Chandrasekar, V.; Cifelli, R.; Xie, P. A machine learning system for precipitation estimation using satellite and ground radar network observations. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2019, 58, 982–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaelides, S.; Levizzani, V.; Anagnostou, E.; Bauer, P.; Kasparis, T.; Lane, J.E. Precipitation: Measurement, remote sensing, climatology and modeling. Atmos. Res. 2009, 94, 512–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Babel, M.S.; Agarwal, A.; Khadka, D.; Baghel, T. A comprehensive assessment of suitability of Global Precipitation Products for hydro-meteorological applications in a data-sparse Himalayan region. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2023, 153, 263–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCabe, M.F.; Rodell, M.; Alsdorf, D.E.; Miralles, D.G.; Uijlenhoet, R.; Wagner, W.; Lucieer, A.; Houborg, R.; Verhoest, N.E.; Franz, T.E.; et al. The future of Earth observation in hydrology. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2017, 21, 3879–3914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, S.D.; Straka, W., III; Mills, S.P.; Elvidge, C.D.; Lee, T.F.; Solbrig, J.; Walther, A.; Heidinger, A.K.; Weiss, S.C. Illuminating the capabilities of the suomi national polar-orbiting partnership (NPP) visible infrared imaging radiometer suite (VIIRS) day/night band. Remote Sens. 2013, 5, 6717–6766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levizzani, V.; Cattani, E. Satellite remote sensing of precipitation and the terrestrial water cycle in a changing climate. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 2301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheffield, J.; Wood, E.F.; Pan, M.; Beck, H.; Coccia, G.; Serrat-Capdevila, A.; Verbist, K.J.W.R.R. Satellite remote sensing for water resources management: Potential for supporting sustainable development in data-poor regions. Water Resour. Res. 2018, 54, 9724–9758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, M.; Nguyen, P.; Naeini, M.R.; Hsu, K.; Braithwaite, D.; Sorooshian, S. PERSIANN-CCS-CDR, a 3-hourly 0.04 global precipitation climate data record for heavy precipitation studies. Sci. Data 2021, 8, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, J.; Tang, G.; Yang, Y. Continental evaluation of GPM IMERG V07B precipitation on a sub-daily scale. Remote Sens. Environ. 2025, 321, 114690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, P.; Joyce, R.; Wu, S.; Yoo, S.H.; Yarosh, Y.; Sun, F.; Lin, R. Reprocessed, bias-corrected CMORPH global high-resolution precipitation estimates from 1998. J. Hydrometeorol. 2017, 18, 1617–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebrechorkos, S.H.; Leyland, J.; Dadson, S.J.; Cohen, S.; Slater, L.; Wortmann, M.; Ashworth, P.J.; Bennett, G.L.; Boothroyd, R.; Cloke, H.; et al. Global scale evaluation of precipitation datasets for hydrological modelling. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2023, 28, 3099–3118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.H.; Popescu, I.; Jonoski, A.; Solomatine, D.P. Remote sensed and/or global datasets for distributed hydrological modelling: A review. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebregiorgis, A.S.; Hossain, F. Understanding the dependence of satellite rainfall uncertainty on topography and climate for hydrologic model simulation. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2012, 51, 704–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Liu, C.; Tang, Y.; Niu, C.; Fan, Y.; Luo, Q.; Hu, C. Study on runoff simulation with multi-source precipitation information fusion based on multi-model ensemble. Water Resour. Manag. 2024, 38, 6139–6155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nourani, V.; Gökçekuş, H.; Gichamo, T. Ensemble data-driven rainfall-runoff modeling using multi-source satellite and gauge rainfall data input fusion. Earth Sci. Inform. 2021, 14, 1787–1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, W.; Qin, H.; Liu, G.; Yang, X.; Xu, Z.; Jia, B.; Zhang, Q. A method for spatiotemporally merging multi-source precipitation based on deep learning. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 4160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; She, D.; Zhang, L.; Xia, J.; Chen, S.; Wang, G. Quantifying and reducing the uncertainty in multi-source precipitation products using Bayesian total error analysis: A case study in the Danjiangkou Reservoir region in China. J. Hydrol. 2022, 614, 128557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.Y.; Anh, T.N.; Nguyen, H.D.; Dang, D.K. Quantile mapping technique for enhancing satellite-derived precipitation data in hydrological modelling: A case study of the Lam River Basin, Vietnam. J. Hydroinform. 2024, 26, 2026–2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Yuan, Q.; Ma, J.; Wang, L. Improved daily spatial precipitation estimation by merging multi-source precipitation data based on the geographically weighted regression method: A case study of Taihu Lake Basin, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, Y.; Xiong, A.; Hong, Y.; Yu, J.; Pan, Y.; Chen, Z.; Saharia, M. Uncertainty analysis of five satellite-based precipitation products and evaluation of three optimally merged multi-algorithm products over the Tibetan Plateau. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2014, 35, 6843–6858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, Z.; Lin, Q.; He, H. Improvement of a combination of TMPA (or IMERG) and ground-based precipitation and application to a typical region of the East China Plain. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 640, 1165–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, M.; O’Nils, M.; Lundgren, J.; Mousavirad, S.J. A comprehensive review on deep learning-based data fusion. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 180093–180124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sham, F.A.F.; El-Shafie, A.; Jaafar, W.Z.W.; Sherif, M.; Ahmed, A.N. Advances in AI-based rainfall forecasting: A comprehensive review of past, present, and future directions with intelligent data fusion and climate change models. Results Eng. 2025, 27, 105774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichstein, M.; Camps-Valls, G.; Stevens, B.; Jung, M.; Denzler, J.; Carvalhais, N.; Prabhat, F. Deep learning and process understanding for data-driven Earth system science. Nature 2019, 566, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samadzadegan, F.; Toosi, A.; Javan, F.D. A critical review on multi-sensor and multi-platform remote sensing data fusion approaches: Current status and prospects. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2025, 46, 1327–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aderyani, F.R.; Mousavi, S.J.; Jafari, F. Short-term rainfall forecasting using machine learning-based approaches of PSO-SVR, LSTM and CNN. J. Hydrol. 2022, 614, 128463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, B.; Hsu, K.; AghaKouchak, A.; Sorooshian, S. Improving precipitation estimation using convolutional neural network. Water Resour. Res. 2019, 55, 2301–2321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, P.S.; Yang, T.C.; Chen, S.Y.; Kuo, C.M.; Tseng, H.W. Comparison of random forests and support vector machine for real-time radar-derived rainfall forecasting. J. Hydrol. 2017, 552, 92–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gee, K.; Blazauskas, N.; Dahl, K.; Göke, C.; Hassler, B.; Kannen, A.; Leposa, N.; Morf, A.; Strand, H.; Weig, B.; et al. Can tools contribute to integration in MSP? A comparative review of selected tools and approaches. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2019, 179, 104834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padulano, R.; Costabile, P.; Costanzo, C.; Rianna, G.; Del Giudice, G.; Mercogliano, P. Using the present to estimate the future: A simplified approach for the quantification of climate change effects on urban flooding by scenario analysis. Hydrol. Process. 2021, 35, e14436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Zhou, L.; Wang, H.; Lin, J.; Huang, Y.; Zhuo, P.; Ao, T. Development of fractional vegetation cover change and driving forces in the Min River Basin on the Eastern margin of the Tibetan plateau. Forests 2025, 16, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Tian, C.S.; Wang, Y.K.; Liu, Q.; Lu, Y.F.; Shan, W. Impacts of future climate change (2030–2059) on debris flow hazard: A case study in the Upper Minjiang River basin, China. J. Mt. Sci. 2018, 15, 1836–1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Liu, J.; Zhang, L.; Shrestha, U.B.; Luo, D.; Wei, Y.; Wang, J. Assessing Climate and Land Use Change Impacts on Ecosystem Services in the Upper Minjiang River Basin. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Gu, Y.; Wang, H.; Lin, J.; Zhuo, P.; Ao, T. Response of Vegetation Coverage to Climate Drivers in the Min-Jiang River Basin along the Eastern Margin of the Tibetan Plat-Eau, 2000–2022. Forests 2024, 15, 1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, M.; Zhang, W.; Yu, H.; Lu, X.; Feng, J.; Fan, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Chen, D. An overview of the China Meteorological Administration tropical cyclone database. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 2014, 31, 287–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faybishenko, B.; Versteeg, R.; Pastorello, G.; Dwivedi, D.; Varadharajan, C.; Agarwal, D. Challenging problems of quality assurance and quality control (QA/QC) of meteorological time series data. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 2022, 36, 1049–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, C.; Ashouri, H.; Hsu, K.L.; Sorooshian, S.; Duan, Q. Evaluation of the PERSIANN-CDR daily rainfall estimates in capturing the behavior of extreme precipitation events over China. J. Hydrometeorol. 2015, 16, 1387–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Wang, J.; Shi, W.; Chai, R.; Wang, G. Capacity of the PERSIANN-CDR product in detecting extreme precipitation over Huai River Basin, China. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Chen, H.; Cifelli, R.; Xie, P.; Chen, X. Characterizing the uncertainty of CMORPH products for estimating orographic precipitation over Northern California. J. Hydrol. 2024, 643, 131921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, R.K.; Markonis, Y.; Godoy, M.R.; Villalba-Pradas, A.; Andreadis, K.M.; Nikolopoulos, E.I.; Papalexiou, S.M.; Rahim, A.; Tapiador, F.J.; Hanel, M. Review of GPM IMERG performance: A global perspective. Remote Sens. Environ. 2022, 268, 112754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, X.; Guo, H.; Tian, Y.; Meng, X.; Bao, A.; De Maeyer, P. Evaluation of GSMaP version 8 precipitation products on an hourly timescale over mainland China. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, H.E.; Van Dijk, A.I.; Levizzani, V.; Schellekens, J.; Miralles, D.G.; Martens, B.; De Roo, A. MSWEP: 3-hourly 0.25 global gridded precipitation (1979–2015) by merging gauge, satellite, and reanalysis data. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2017, 21, 589–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danso, D.K.; Anquetin, S.; Diedhiou, A.; Lavaysse, C.; Kobea, A.; Touré, N.D.E. Spatio-temporal variability of cloud cover types in West Africa with satellite-based and reanalysis data. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2019, 145, 3715–3731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanasundaram, S.; Baghel, T.; Thakur, V.; Udmale, P.; Shrestha, S. Reconstructing NDVI and land surface temperature for cloud cover pixels of Landsat-8 images for assessing vegetation health index in the Northeast region of Thailand. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2023, 195, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutler, D.R.; Edwards, T.C., Jr.; Beard, K.H.; Cutler, A.; Hess, K.T.; Gibson, J.; Lawler, J.J. Random forests for classification in ecology. Ecology 2007, 88, 2783–2792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.-B.; Zhu, Q.-Y.; Siew, C.-K. Extreme learning machine: Theory and applications. Neurocomputing 2006, 70, 489–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Lu, S.; Wang, S.H.; Zhang, Y.D. A review on extreme learning machine. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2022, 81, 41611–41660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Khorrami, B.; Jehanzaib, M.; Tariq, A.; Ajmal, M.; Arshad, A.; Shafeeque, M.; Dilawar, A.; Basit, I.; Zhang, L.; et al. Spatial downscaling of GRACE data based on XGBoost model for improved understanding of hydrological droughts in the Indus Basin Irrigation System (IBIS). Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Huang, H.; Chen, J.; Yu, Q.; Cai, X. Exploring the Main Driving Factors for Terrestrial Water Storage in China Using Explainable Machine Learning. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 2078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafarzadeh, H.; Mahdianpari, M.; Gill, E.; Mohammadimanesh, F.; Homayouni, S. Bagging and boosting ensemble classifiers for classification of multispectral, hyperspectral and PolSAR data: A comparative evaluation. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 4405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbanpour, A.K.; Hessels, T.; Moghim, S.; Afshar, A. Comparison and assessment of spatial downscaling methods for enhancing the accuracy of satellite-based precipitation over Lake Urmia Basin. J. Hydrol. 2021, 596, 126055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.A.; Yu, B.; Cartwright, N. Assessment and comparison of five satellite precipitation products in Australia. J. Hydrol. 2020, 590, 125474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Shi, Z.; Liu, R.; Xing, M. Evaluating the performance of global precipitation products for precipitation and extreme precipitation in arid and semiarid China. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2024, 130, 103888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Lin, H.; Chen, N.; Chen, Z. Evaluation of multi-source precipitation products over the Yangtze River Basin. Atmos. Res. 2021, 249, 105287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, C.; Lei, X.; Mo, X.; Ruan, R.; Tang, G.; Li, L.; Sun, G.; Jiang, C. Comprehensive evaluation and comparison of ten precipitation products in terms of accuracy and stability over a typical mountain basin, Southwest China. Atmos. Res. 2024, 297, 107116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, L.; Deng, Y.; Wang, S.; Ren, J.; Zhang, K.; Wang, G. Development of a Two-Stage Correction Framework for Satellite, Multi-Source Merged, and Reanalysis Precipitation Products Across the Huang-Huai-Hai Plain, China, During 2000–2020. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 2809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, B.; Chen, X.; Guo, Y.; Liu, L.; Li, P.; Chang, Q. Multi-Source Feature Selection and Explainable Machine Learning Approach for Mapping Nitrogen Balance Index in Winter Wheat Based on Sentinel-2 Data. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Rui, X.; Zou, Y.; Tang, H.; Ouyang, N. Mangrove monitoring and extraction based on multi-source remote sensing data: A deep learning method based on SAR and optical image fusion. Acta Oceanol. Sin. 2024, 43, 110–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, H.; Zhao, H.; Ao, T. A two-step merging strategy for incorporating multi-source precipitation products and gauge observations using machine learning classification and regression over China. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2022, 26, 2969–2995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Lu, J.; Das, P.; Zhang, Z. Machine learning algorithms for merging satellite-based precipitation products and their application on meteorological drought monitoring over Kenya. Clim. Dyn. 2024, 62, 141–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, N.; Ye, J.; Wang, S.; Yang, S.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Yang, X. Bias correction of the hourly satellite precipitation product using machine learning methods enhanced with high-resolution WRF meteorological simulations. Atmos. Res. 2024, 310, 107637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Hsu, C.-Y.; Tedesco, M. Advancing Arctic sea ice remote sensing with AI and deep learning: Opportunities and challenges. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 3764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Zhou, L.; Du, J.; Yue, J.; Ao, T. Accuracy evaluation and comparison of GSMaP series for retrieving precipitation on the eastern edge of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2024, 56, 102017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, Y.; Yong, B. A novel Double Machine Learning strategy for producing high-precision multi-source merging precipitation estimates over the Tibetan Plateau. Water Resour. Res. 2024, 60, e2023WR035643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi, E.; Steinacker, R.; Saghafian, B. Assessment of GPM-IMERG and other precipitation products against gauge data under different topographic and climatic conditions in Iran: Preliminary results. Remote Sens. 2016, 8, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmeister, F.; Graziano, F.; Marcolini, G.; Willems, W.; Disse, M.; Chiogna, G. Quality assessment of hydrometeorological observational data and their influence on hydrological model results in Alpine catchments. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2023, 68, 552–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polz, J.; Graf, M.; Chwala, C. Missing rainfall extremes in commercial microwave link data due to complete loss of signal. Earth Space Sci. 2023, 10, e2022EA002456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, J.; Fang, X.; Ma, Z. Can satellite precipitation estimates capture the magnitude of extreme rainfall Events? Remote Sens. Lett. 2022, 13, 1048–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, T.H.; Stechmann, S.N.; Neelin, J.D. Long temporal autocorrelations in tropical precipitation data and spike train prototypes. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2016, 43, 11472–11480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Hsu, K.; Sorooshian, S.; Xu, X.; Braithwaite, D.; Zhang, Y.; Verbist, K.M. Merging high-resolution satellite-based precipitation fields and point-scale rain gauge measurements—A case study in Chile. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2017, 122, 5267–5284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putra, M.; Rosid, M.S.; Handoko, D. High-Resolution Rainfall Estimation Using Ensemble Learning Techniques and Multisensor Data Integration. Sensors 2024, 24, 5030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, S.; Wang, J.; Shi, F.; Zhuo, P.; Ao, T. Research on Multi-Source Precipitation Fusion Based on Classification and Regression Machine Learning Methods—A Case Study of the Min River Basin in the Eastern Source of the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3982. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243982

Liu S, Wang J, Shi F, Zhuo P, Ao T. Research on Multi-Source Precipitation Fusion Based on Classification and Regression Machine Learning Methods—A Case Study of the Min River Basin in the Eastern Source of the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau. Remote Sensing. 2025; 17(24):3982. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243982

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Shuyuan, Jingwen Wang, Fangxin Shi, Peng Zhuo, and Tianqi Ao. 2025. "Research on Multi-Source Precipitation Fusion Based on Classification and Regression Machine Learning Methods—A Case Study of the Min River Basin in the Eastern Source of the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau" Remote Sensing 17, no. 24: 3982. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243982

APA StyleLiu, S., Wang, J., Shi, F., Zhuo, P., & Ao, T. (2025). Research on Multi-Source Precipitation Fusion Based on Classification and Regression Machine Learning Methods—A Case Study of the Min River Basin in the Eastern Source of the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau. Remote Sensing, 17(24), 3982. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243982