1. Introduction

Hyperspectral imagery (HSI), acquired by remote sensing platforms, captures a wealth of diagnostic information by integrating hundreds of contiguous spectral bands with spatial details [

1,

2,

3,

4]. This rich joint spectral–spatial data cube has become indispensable for a diverse range of applications, including mineralogical mapping, precision agriculture, environmental monitoring, and defense surveillance [

5]. A critical task within HSI analysis is hyperspectral anomaly detection (HAD), which aims to identify pixels that exhibit significant spectral and spatial deviations from the surrounding, often complex, background materials [

1]. Given that anomalies are, by definition, rare, spectrally distinct, and occur without prior knowledge, developing robust unsupervised detectors is a long-standing and challenging research problem.

The benchmark algorithm for HAD is the Reed–Xiaoli (RX) detector [

6]. It operates under the statistical assumption that the background can be modeled by a singular multivariate Gaussian distribution, quantifying anomalies using the Mahalanobis distance. However, this assumption is frequently violated in real-world scenarios, where HSI backgrounds are characterized by highly non-linear and multi-modal distributions [

7]. Consequently, the RX detector’s performance degrades significantly in complex environments, often suffering from a high false-alarm rate.

To address the limitations of linear statistical models, representation-based methods were proposed, including those founded on sparse representation (SR) and low-rank representation (LRR) [

8,

9,

10]. The core hypothesis of these methods is that background pixels, which form the dominant subspace, can be accurately represented by a background dictionary or neighboring pixels, whereas anomaly pixels, which lie outside this subspace, cannot [

8]. While these approaches provide improved background modeling, they are still fundamentally constrained by their reliance on linear representation models. This makes it difficult to capture the highly non-linear joint spectral–spatial features inherent in complex HSI data.

In recent years, deep learning (DL) has emerged as the dominant paradigm for HAD, owing to its potent non-linear feature extraction and abstract representation capabilities [

5]. The majority of unsupervised DL methods, such as Autoencoders (AEs) [

11] and Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) [

12], are predicated on the “background reconstruction hypothesis” [

1]. This hypothesis posits that a network trained on the entire unlabeled HSI cube will preferentially learn the dominant, high-frequency background patterns. Anomalies, being sparse and statistically divergent, are expected to be poorly reconstructed, allowing their identification via a high reconstruction error. However, a critical limitation arises from the model’s inherent generalization capability: the network’s powerful capacity inadvertently allows it to learn to reconstruct anomalies, a phenomenon known as the “over-reconstruction” problem [

13]. To mitigate this, advanced regularization strategies have been introduced. Notably, DeCNN-AD [

14] proposed a “plug-and-play” prior framework, integrating a denoising Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) to explicitly regularize the background representation and suppress anomaly contamination.

Driven by the need for more discriminative feature extraction, the architectural landscape of HAD has evolved rapidly beyond standard Autoencoders. Hybrid architectures like HTC-HAD [

15] have been developed to reconcile the trade-off between local and global information, employing dual-branch designs that combine CNNs for local texture with Transformers for long-range dependencies. More recently, the field has witnessed the rise of State Space Models (SSMs), particularly the Mamba architecture, which offers global modeling capabilities with linear computational complexity. MMR-HAD [

16] represents a pioneering application of this architecture to HAD, utilizing a multi-scale Mamba reconstruction network with random masking strategies to efficiently model long spectral sequences. Despite these advancements, the standard Vision Transformer (ViT) architecture still exhibits a critical flaw when applied to HAD: “uniform processing” [

17]. The standard self-attention mechanism applies the exact same global feature extraction operation to all tokens in the image. This approach is suboptimal, as homogeneous background regions and regions containing subtle anomalies possess vastly different information entropy and feature scales [

18]. Applying indiscriminate computation to both leads to a poor trade-off between compressing global background redundancy and extracting local anomaly details, motivating a shift toward differentiated processing [

19].

Beyond this architectural limitation, a more fundamental, microscopic flaw persists across all existing deep HAD models—including AEs, CNN–Transformers, and Mamba networks. Their non-linear transformations rely on Multi-Layer Perceptrons (MLPs), or Feed-Forward Networks (FFNs), which in turn depend on fixed non-linear activation functions (e.g., ReLU, GELU, or SiLU). Theoretically, HSI spectral signatures are continuous physical functions governed by electronic transitions and molecular vibrations, characterized by highly complex and smooth absorption features. A single, pre-defined function like ReLU (piecewise linear) is mathematically insufficient to serve as the optimal basis for approximating these continuous, high-order spectral curves. The rigid basis functions of MLPs limit the network’s ability to efficiently capture the subtle high-frequency oscillations and smooth gradients typical of hyperspectral signatures without excessive parameter expansion.

Currently, Kolmogorov–Arnold Networks (KANs), introduced by Liu et al. [

20], offer a revolutionary paradigm. Inspired by the Kolmogorov–Arnold representation theorem, KANs replace the fixed, node-based activation functions of MLPs with learnable, edge-based activation functions parameterized as B-splines. This design grants KANs superior function approximation capabilities, allowing them to adaptively “discover” the optimal non-linear shape required to model complex spectral distributions. While KACNet [

21] has successfully pioneered the integration of KANs into a convolutional framework for HAD, demonstrating the efficacy of KAN-based convolution for local feature extraction, the application of KANs within the Transformer architecture to enhance global dependency modeling remains an unexplored frontier.

In this paper, we propose the Synergistic Kolmogorov–Arnold Networks and Fidelity-Gated Transformer (KANGT), a novel architecture that simultaneously addresses the macro-level “uniform processing” and the micro-level “fixed activation” limitations. Our model achieves this through a synergistic design of two independent innovations. First, to address “uniform processing” at the architectural level, we design the Fidelity-Gated Context-Aware Transformer (GCAT). The GCAT features two specialized streams—a Local Anomaly Recognition Branch (LARB) and a Global Background Recognition Branch (GBRB)—routed by a Contextual Feature Matching Module (CFMM). Unlike prior methods, the CFMM employs an explicit, fidelity-based gating mechanism that dynamically separates background and anomaly streams based on reconstruction quality. Second, to solve the “fixed activation” problem at the component level, we are the first to systematically introduce a KAN-MLP module into the HAD Transformer architecture. Distinct from the convolutional KAN implementation in KACNet [

21], we design a KAN-MLP to replace the traditional FFN in the Transformer block. By utilizing learnable spline-based activation functions, the KAN-MLP can adaptively and precisely model the continuous, subtle non-linear spectral relationships that fixed-activation MLPs fail to capture.

By organically combining these two innovations, KANGT achieves a new state of the art in HAD. The main contributions of this paper are summarized as follows:

We propose the GCAT, a novel dual-branch architecture that addresses the “uniform processing” limitation of standard Transformers. Its core innovation, the CFMM, provides an explicit, fidelity-based gating mechanism that achieves a pure separation of background and anomaly processing paths.

We are the first to design a KAN-MLP module for the HAD Transformer, replacing the traditional FFN. This novel component addresses the “fixed activation” limitation by employing learnable spline-based functions, offering a theoretically superior method for approximating continuous hyperspectral signatures compared to fixed activations.

We present the complete KANGT framework, a synergistic integration of the GCAT and KAN-MLP, which simultaneously addresses both architectural and component-level limitations of current SOTA models.

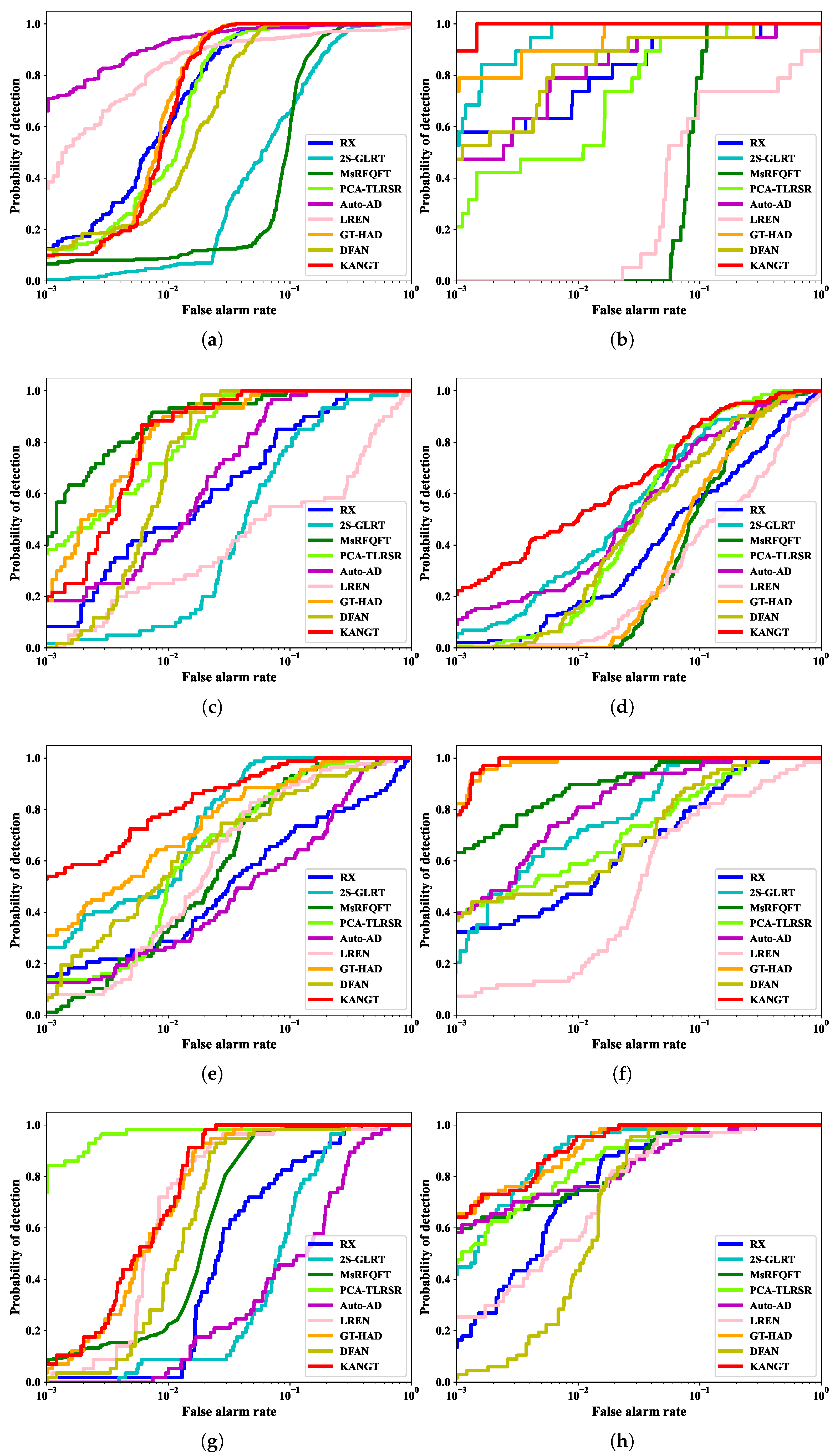

Extensive experiments conducted on eight challenging real-world HSI datasets demonstrate that KANGT significantly outperforms existing classical and deep learning-based HAD methods, validating the effectiveness of our dual-innovation design.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 reviews related work in HAD.

Section 3 details the proposed KANGT framework.

Section 4 presents the comparative experiments, ablation experiment settings, and results.

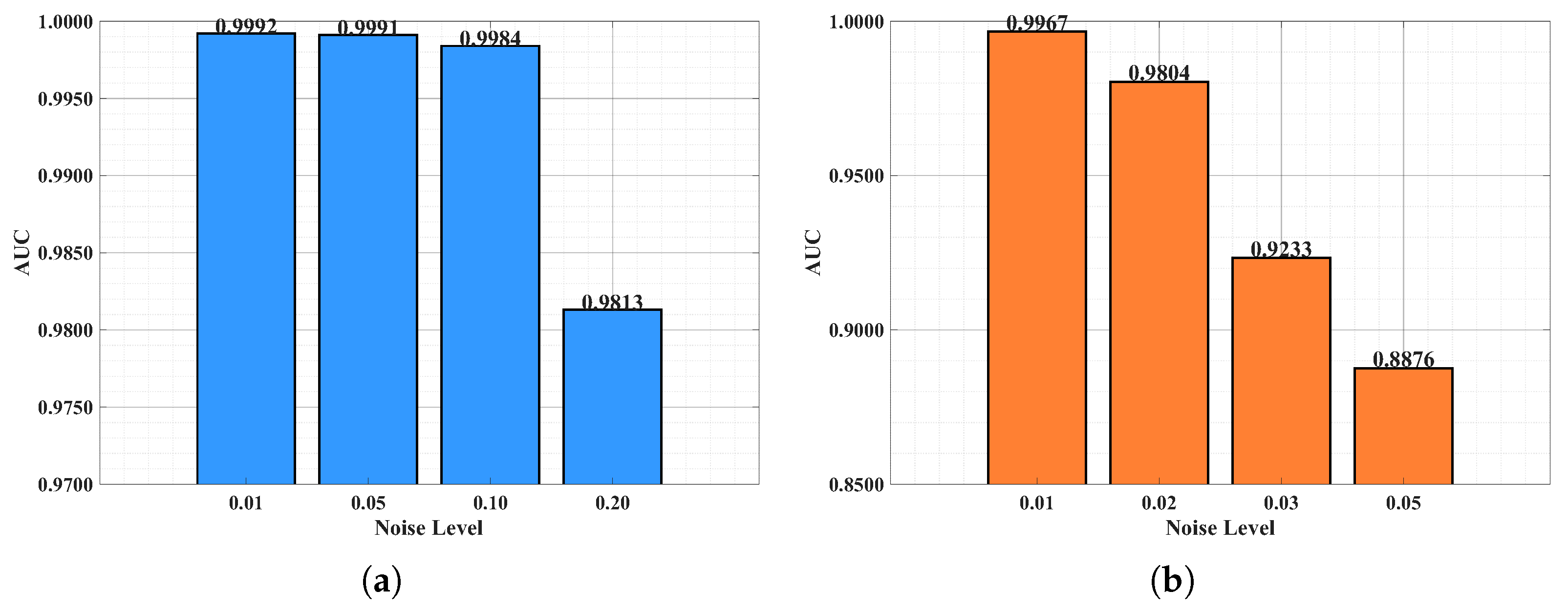

Section 5 further discusses and analyzes the model’s generalization and anti-interference capabilities.. Finally,

Section 6 concludes this paper.

2. Related Work

HAD aims to identify minority pixels that exhibit significant spectral deviations from the surrounding background [

1]. Early HAD methods predominantly relied on statistical modeling and conventional representation theories. The most representative of these is the RX detector [

6], which assumes that the background follows a singular multivariate Gaussian distribution and employs the Mahalanobis distance to measure anomaly. However, HSI scenes often possess highly non-linear and multi-modal complex backgrounds, causing the Constant False-Alarm Rate (CFAR) characteristic of the RX detector to be difficult to maintain in complex environments, resulting in a high false-alarm rate [

22].

To overcome the stringent assumptions of the RX algorithm regarding the background model, representation-based learning methods were subsequently proposed. The core assumption of these methods is that background pixels can be effectively represented by a background dictionary or neighboring pixels, whereas anomaly pixels cannot. This category includes models based on SR [

23] and LRR [

8,

9,

10]. For instance, methods such as prior-based tensor approximation (PTA) [

8] and tensor low-rank sparse representation based on principal component analysis (PCA-TLRSR) [

9] leverage global and local structural priors of HSI to enhance background modeling capabilities to some extent. Despite this progress, these methods largely depend on linear representation models and shallow optimization, making it difficult to capture the highly non-linear joint spectral–spatial features inherent in HSI [

24].

2.1. Deep Reconstruction Architectures

In recent years, deep learning (DL), by virtue of its powerful non-linear feature extraction and abstract representation capabilities, has become the mainstream paradigm in the HAD field [

5]. In unsupervised HAD tasks, the vast majority of DL methods are based on the “background reconstruction hypothesis” [

1,

5]. The core idea is that a deep neural network (such as an AE or GAN) trained only on HSI data will preferentially learn the dominant, high-frequency background patterns. Due to the sparsity and statistical divergence of anomalies, the model will struggle to accurately reconstruct these anomalous pixels [

5]. Therefore, anomalies can be effectively identified by calculating the residual between the original input and the reconstructed output.

Under this framework, AEs and their variants [

11] and GANs [

12] have become two primary implementation paths. For example, Auto-AD [

11] employed a Fully Convolutional Autoencoder (FCAE) with skip connections. However, a critical limitation arises from the model’s inherent generalization capability: the network’s powerful capacity inadvertently allows it to learn to reconstruct anomalies, a phenomenon known as the “over-reconstruction” problem [

13]. Early approaches attempted to address this contamination through specialized loss functions. Auto-AD introduced an “adaptive-weighted loss function” to suppress anomaly reconstruction by dynamically reducing the weight of potential anomaly pixels during training [

11]. Similarly, models based on Deep Belief Networks (DBNs) utilized adaptive weights derived from reconstruction errors to mitigate background contamination [

25].

Despite these efforts, research indicates that such monolithic network architectures, based on global modeling, are inevitably contaminated by anomaly pixels during training [

17]. This architectural limitation prevents the network from learning a pure background prior, thereby limiting background–anomaly separability. This fundamental challenge has motivated researchers to explore more specialized and discriminative network backbones, particularly those capable of differentiated feature processing, such as the Transformer [

26].

2.2. Generative Probabilistic Models and Diffusion Paradigms

While deep reconstruction-based architectures such as AEs and GANs have fundamentally advanced the field of HAD, they are often constrained by the “over-generalization” phenomenon—where high-capacity networks inadvertently reconstruct anomalies—and the training instabilities inherent in adversarial learning. Recently, Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models (DDPMs) [

27] have emerged as a revolutionary paradigm, offering superior capabilities in modeling complex data manifolds and estimating probability densities. Unlike deterministic models that map inputs directly to latent representations, diffusion models learn the background distribution by iteratively reversing a gradual noise-addition process (typically modeled as a Markov chain). This probabilistic framework allows anomalies to be rigorously defined as low-likelihood events within the learned background density, theoretically mitigating the identity mapping problem.

Pioneering research has begun to adapt this generative paradigm to the unsupervised nature of HAD. Ma et al. introduced the Background Suppression Diffusion Model (BSDM) [

28], which conceptually inverts the traditional denoising logic. Instead of treating anomalies as noise, the BSDM learns a “pseudo-background noise” distribution; during inference, the iterative denoising process reconstructs the high-probability background features while suppressing the statistically divergent anomalies. Bridging the gap between classical representation theory and modern generative AI, Wu et al. proposed the Diffusing Background Dictionary (DBD) framework [

29]. DBD integrates diffusion models with tensor low-rank representation (LRR) [

9], employing the diffusion model to generate a high-fidelity, manifold-constrained background dictionary tensor, thereby preventing the leakage of anomalous signals into the background subspace. Furthermore, addressing the specific spatial–spectral dependencies of HSI, Chen et al. developed Dual-Window Spectral Diffusion (DWSDiff) [

30]. By incorporating a dual-window guard strategy into the spectral diffusion process, DWSDiff effectively mitigates the contamination of local background estimates by adjacent anomalies, achieving precise iterative background reconstruction.

Despite their theoretical elegance and effectiveness in density estimation, diffusion-based methods inherently incur high computational latency due to the requirement of multi-step iterative sampling during inference. In this context, our proposed KANGT framework seeks to achieve comparable or superior background–anomaly separability through a deterministic, single-pass architecture. By leveraging the explicit fidelity-based gating of the GCAT and the adaptive, continuous non-linear approximation of KANs, KANGT offers a computationally efficient alternative that circumvents the iterative burden of probabilistic sampling while maintaining robust background suppression capabilities.

2.3. Adaptive Differentiated Feature Modeling

The Transformer architecture, with its self-attention mechanism, has demonstrated significant advantages in capturing global long-range dependencies and has been rapidly applied to HSI feature extraction [

31,

32]. Unlike the local receptive fields of CNNs [

33], the Transformer [

34] can effectively model the complex joint spectral–spatial correlations in HSI. However, the standard Vision Transformer (ViT) architecture exhibits a critical flaw when applied to HAD: “uniform processing” [

17].

The standard self-attention mechanism applies the exact same global feature extraction operation to all tokens in the image. Yet, in HSI scenes, homogeneous background regions and regions containing subtle anomalies possess vastly different information entropy and feature scales [

18]. Applying indiscriminate global computation to both is not only computationally inefficient but also leads the model to a suboptimal trade-off between extracting local anomaly details and compressing global background redundancy.

To overcome the uniformity issue, the latest architectural trend is shifting toward differentiated processing, employing dual-branch [

35] or gated architectures [

36] that specialize in feature extraction. This principle is validated in the advanced HSI literature. For instance, in related feature extraction tasks, dual-branch architectures have been utilized to separate global and local information: the Dual-Branch Transformer Encoder (DTE) framework incorporates a dedicated global Transformer branch and a locally enhanced branch, often utilizing an adaptive fusion strategy via learnable weights [

19]. Similarly, other dual-window Transformer frameworks have been designed to fuse local information with global feedback from a pyramid structure [

32], corroborating the necessity of tailored processing paths.

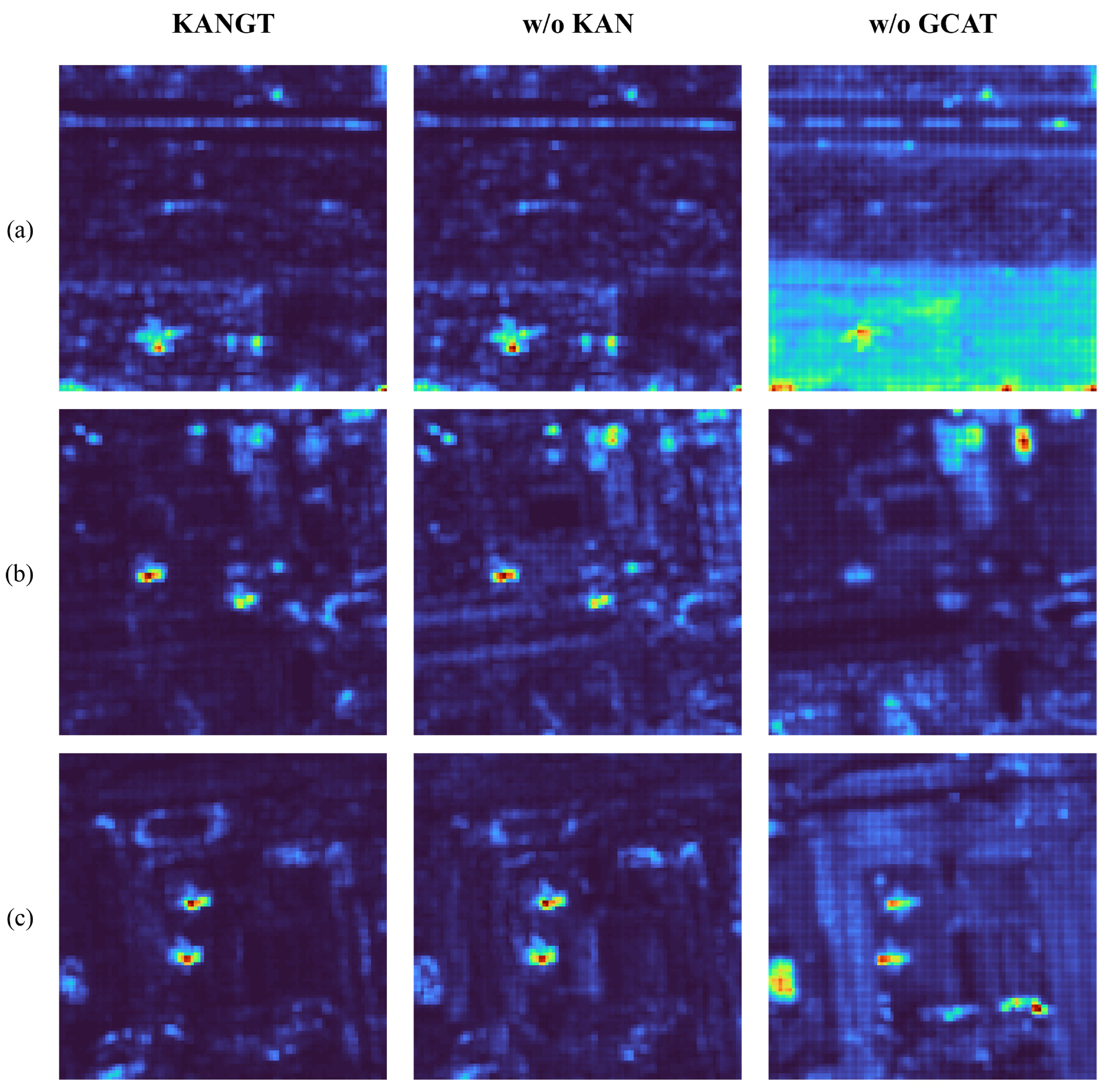

The KANGT model proposed in this paper is a further advancement of this cutting-edge research trend. We construct a Fidelity-Gated Context-Aware Transformer featuring a Local Anomaly Recognition Branch dedicated to anomaly suppression and a Global Background Recognition Branch dedicated to robust background modeling. The core innovation is our proposal of a dynamic, explicit gating mechanism based on reconstruction fidelity—the CFMM. Unlike prior dual-branch approaches that rely on soft attention or static learned weights, the CFMM dynamically determines the data flow path by iteratively evaluating the reconstruction error against the original data. This fidelity-based explicit routing mechanism creates a self-improving loop, achieving a pure separation that fundamentally addresses the “uniform processing” limitation of standard Transformers.

2.4. Kolmogorov–Arnold Networks for Enhanced Non-Linear Representation

Despite the continuous evolution of these architectures, all existing deep HAD models (including AE, GAN, and Transformer) share a common, fundamental limitation at a deeper, microscopic level: they all rely on MLPs [

37] (often called FFNs in Transformers) for non-linear feature transformation. These MLPs, in turn, depend on fixed non-linear activation functions, such as ReLU, GELU, or SiLU [

38].

As we note in our work, this reliance on a fixed activation function fundamentally limits the adaptability of the network to complex spectral–spatial patterns in HSI data. The spectral signatures of HSI are characterized by highly complex and subtle non-linear properties, and a single, pre-defined function (like ReLU) is mathematically insufficient to serve as the optimal non-linear basis.

Currently, Kolmogorov–Arnold Networks (KANs), proposed by Liu et al. [

20,

39], offer a completely new approach to solving this fundamental problem. Inspired by the Kolmogorov–Arnold representation theorem, KANs fundamentally change the design paradigm of neural networks [

20]. Unlike MLPs, which apply fixed activation functions on nodes (“neurons”), KANs apply learnable activation functions on edges (“weights”). These edge-based activation functions are parameterized as 1D splines (e.g., B-splines), allowing their shapes to be adaptively adjusted during training [

40].

Theoretical and empirical studies [

20,

41] have shown that KANs possess superior function approximation capabilities and exhibit faster neural scaling laws and higher parameter efficiency than MLPs [

42]. Furthermore, KANs offer enhanced interpretability, facilitating the decomposition of high-dimensional functions into simpler univariate functions, aiding in the discovery of mathematical and physical laws, a significant benefit for rigorous scientific domains like remote sensing [

43].

As a disruptive technology, the application of KANs in the remote sensing field is still in its nascent stages [

44]. The few published works primarily focus on classification [

45] and segmentation [

46] tasks, such as Wav-KAN for HSI classification [

47] and FloodKAN for land cover segmentation [

48]. However, to the best of our knowledge, currently only pioneering work [

21] has explored the powerful function approximation capabilities of Kolmogorov–Arnold Networks for the unique unsupervised reconstruction task of HAD.

The KANGT proposed in this paper aims to fill this critical gap. We are the first to systematically introduce the KAN philosophy into the core Transformer component of the HAD domain, designing the KAN-MLP module to replace the traditional FFN. By organically combining two independent, cutting-edge innovations—one at the macro (architecture) level, the GCAT, and one at the micro (component) level, the learnable activation function (KAN-MLP)—KANGT simultaneously addresses the two major limitations of existing models: “uniform processing” and “fixed activation”. This synergistic design achieves more precise modeling of complex backgrounds and more sensitive detection of faint anomalies.

3. Methodology

Building upon the powerful representational capabilities of Transformer architectures for hyperspectral content modeling, we introduce KANGT, a novel framework that integrates Kolmogorov–Arnold Networks with gated Transformer mechanisms for enhanced anomaly detection. This section elaborates on the architectural design and operational principles of our proposed approach.

3.1. Overall Framework

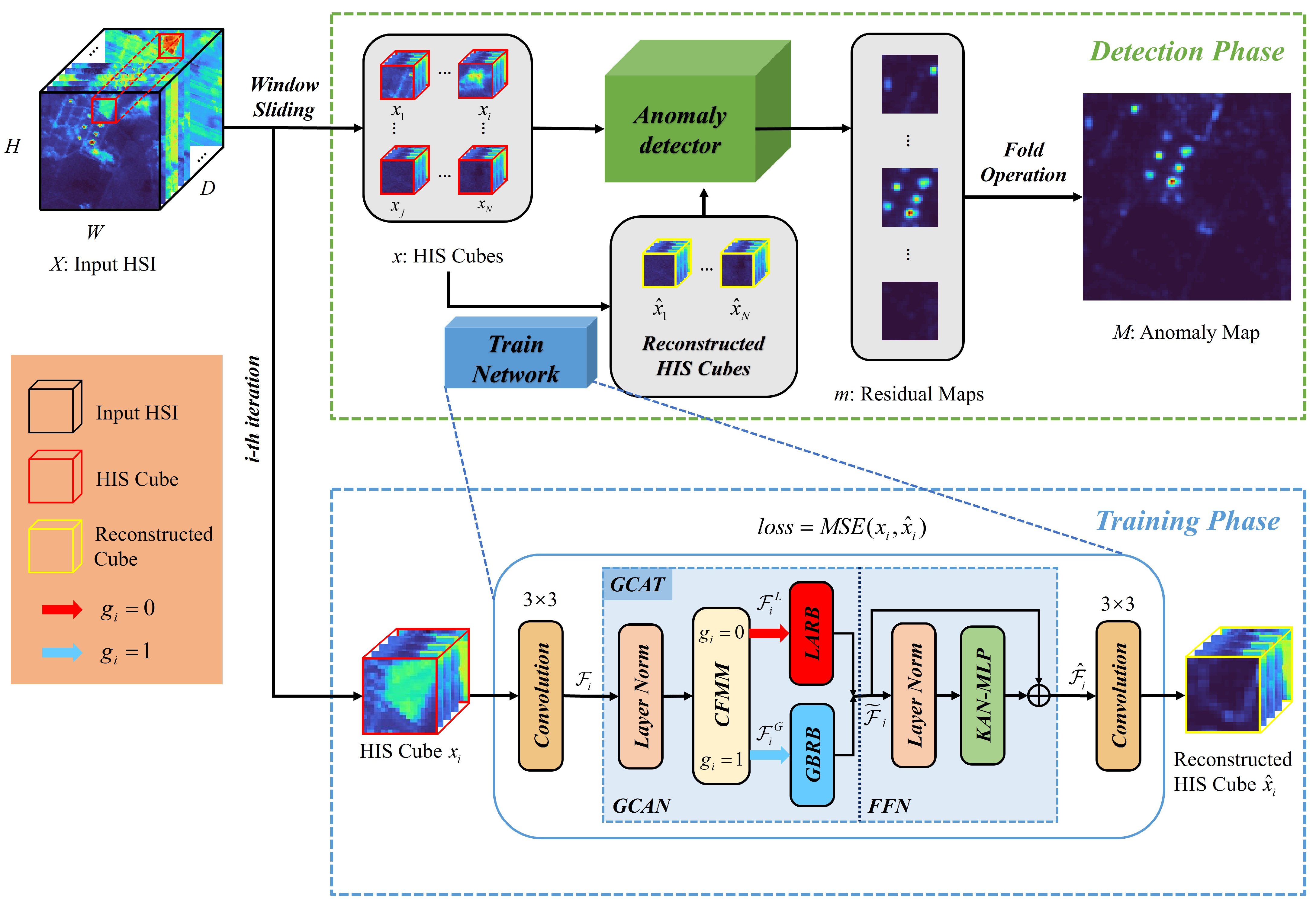

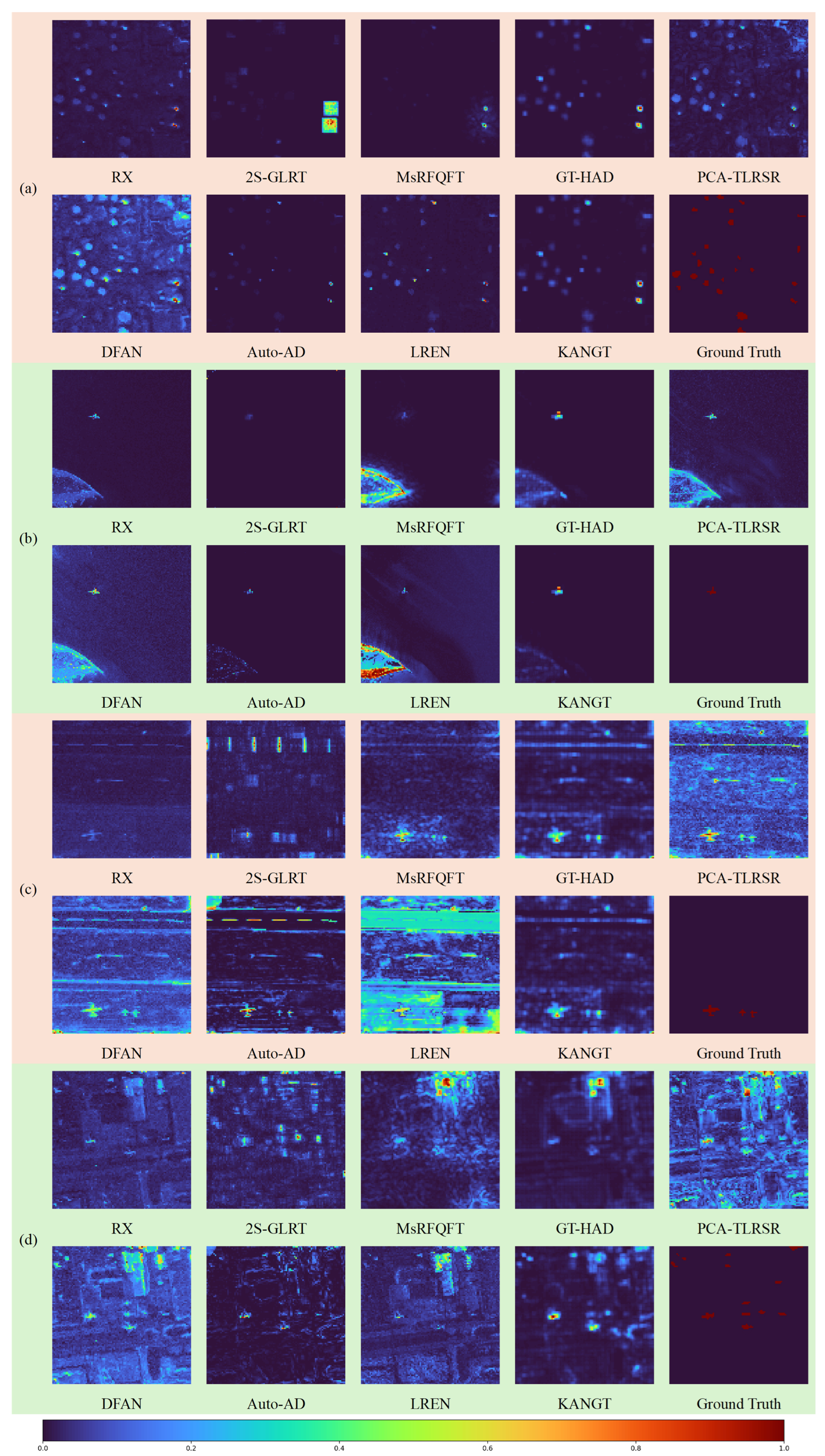

The KANGT framework operates in two phases, as shown in

Figure 1. During the training phase, network optimization is achieved by minimizing reconstruction errors between input and output HSI cubes. Our architecture employs an efficient design philosophy, featuring a Fidelity-Gated Context-Aware Transformer core embedded between convolutional encoding and decoding layers. The GCAT module encompasses two complementary processing streams: the LARB and GBRB, which specialize in handling anomalous and background regions through distinct computational strategies. A dynamic gating mechanism, governed by our CFMM, determines the routing of feature maps between these branches.

Given an input HSI data volume with spatial dimensions and spectral bands D, we first decompose into N overlapping cubes using a sliding window operation. The standard configuration employs spatial patches with a 3-pixel stride. These patches serve as training instances for network optimization.

The processing pipeline initiates with a convolutional encoder that transforms input cube into feature representation , where defines the feature dimensionality. The GCAT module then processes to generate refined features , with branch selection controlled by gating signal . Final reconstruction is produced through a convolutional decoder.

Network parameters

are optimized by minimizing the reconstruction objective:

where

B denotes batch size and

represents the Frobenius norm [

49].

During inference, anomaly scores are derived from residual tensors

, which are spatially aggregated and fused to produce the final detection map

. The proposed KANGT method is described in detail in Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1 KANGT: Training and detection pipeline. |

- Require:

HSI data , patch size , stride , batch size B, max iterations , CFMM search period . - Ensure:

Anomaly map .

Decompose into N overlapping cubes . Initialize parameters , gating states . {Training Phase} for iteration to do Sample mini-batch from . for each in the batch do (using Equation ( 2)) (using Equation ( 5)) end for Compute loss (Equation ( 1)). Update via gradient descent. if and then end if end for {Detection Phase} Initialize empty list for each cube in do Generate reconstruction using trained model . Compute 3D residual . Apply multi-scale diffusion (Equation ( 14)). Aggregate 2D score (Equation ( 15)). Append to . end for Fuse final map (Equation ( 16)). return

|

3.2. Fidelity-Gated Context-Aware Transformer Architecture

The GCAT module forms the computational core of our framework, structured as a sequential composition of a gated context-aware network (GCAN) and KAN-enhanced FFN. The GCAN implements conditional feature processing through dual specialized branches, while the FFN performs non-linear feature enhancement.

3.2.1. Gated Context-Aware Network

The GCAN employs a switching mechanism that directs input features through appropriate processing pathways based on content characteristics. For input feature tensor

, the gating controller generates a binary decision signal

that selects between LARB and GBRB processing:

where

and

represent the transformation functions of the respective branches and LN denotes layer normalization.

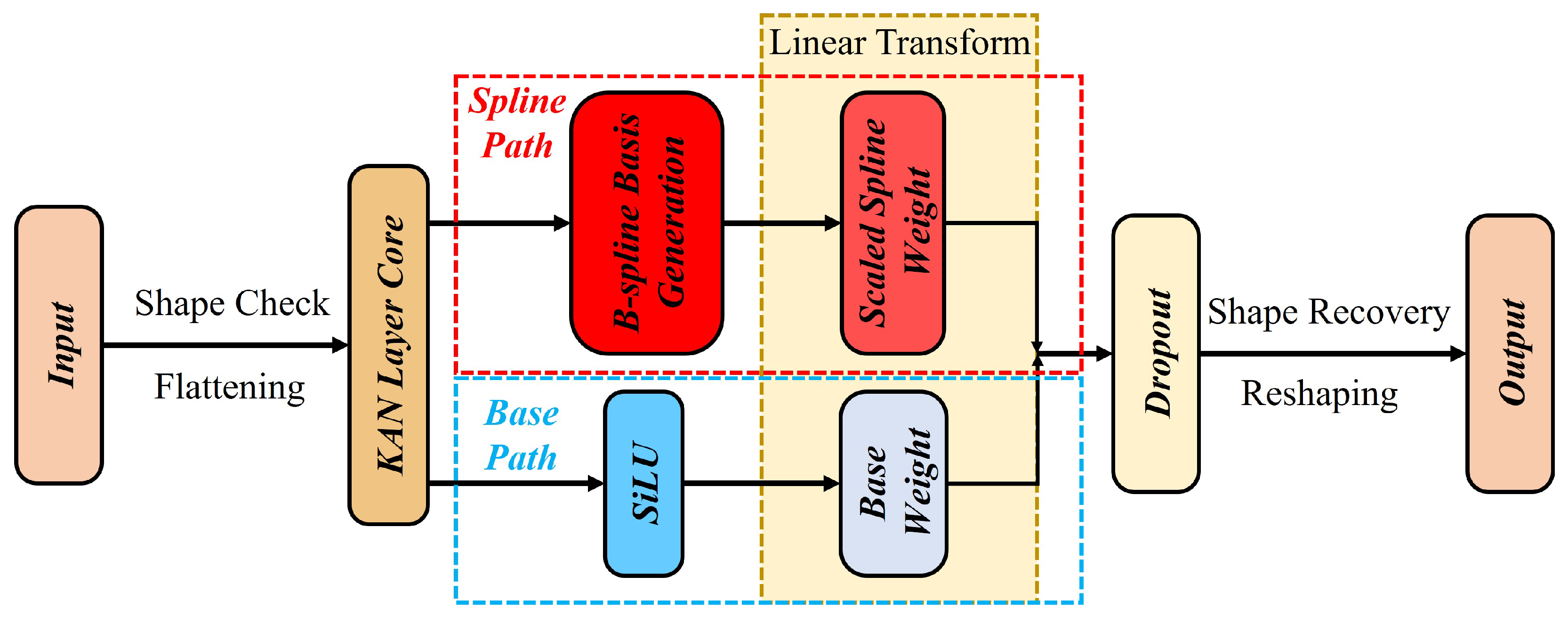

3.2.2. KAN-Enhanced Feature Transformation

Traditional FFNs within Transformer architectures rely on fixed non-linear activation functions (e.g., ReLU or GELU) interleaved with linear projections. This design fundamentally limits the model’s ability to approximate the highly non-linear and continuous spectral signatures inherent in HSI data, as the network is constrained to approximate complex spectral curves using piecewise linear functions. To overcome this limitation and enhance the representation capacity of the GCAT, we introduce the KAN-MLP module, which replaces fixed node-based activations with learnable edge-based activations grounded in the Kolmogorov–Arnold representation theorem.

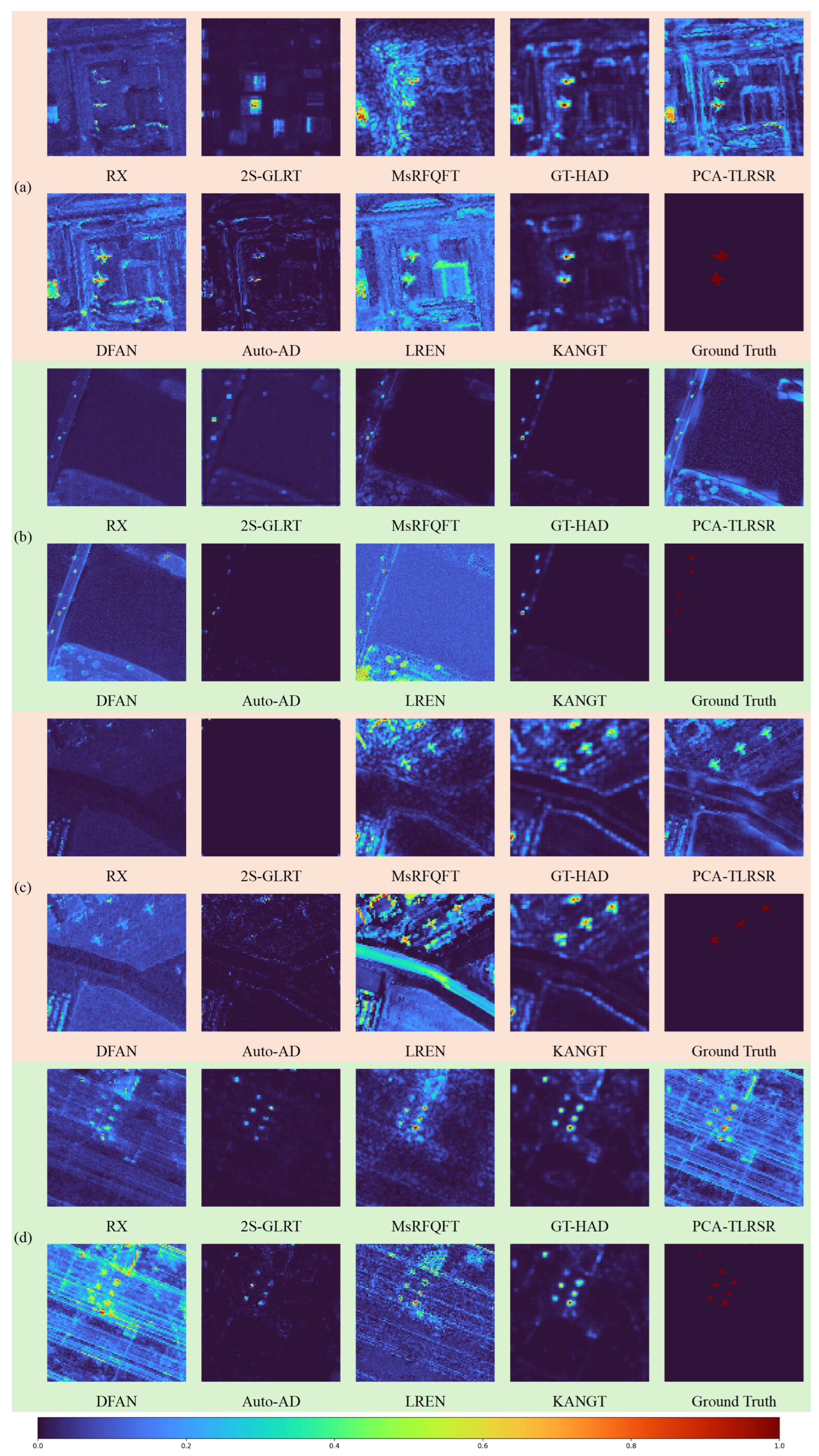

The KAN-MLP module employs a dual-path architecture designed to balance representational plasticity with optimization stability. As illustrated in

Figure 2, for an input feature tensor

, the transformation is decomposed into two parallel processing branches: a base regularization pathand a spline reconstruction path.

The output feature

of a KAN layer is formulated as the additive fusion of these two paths:

where

and

denote the learnable weight matrices for the base and spline paths, respectively.

- (1)

Base Regularization Path:

The first branch captures the global, low-frequency non-linear trends of the data and acts as a structural prior. It utilizes the Sigmoid Linear Unit (SiLU) as the activation function , defined as . We strictly select SiLU over the conventional ReLU for two theoretical reasons essential to the KAN architecture:

Continuity: Unlike the piecewise-linear ReLU, which is non-differentiable at zero (), SiLU is smooth and continuously differentiable (). This matches the curvature continuity of the cubic B-splines used in the second path, ensuring a consistent gradient field during backpropagation and preventing optimization instability caused by discontinuous derivatives.

Gradient Preservation: In anomaly detection, normalized spectral residuals often center around zero. SiLU’s non-monotonic property and linear approximation near the origin () allow the base path to effectively act as a linear residual connection for small signals. This preserves gradient flow through deep layers and mitigates the “dying ReLU” problem where negative spectral deviations—crucial for identifying absorption features—are zeroed out.

- (2)

Spline Reconstruction Path: The second branch models the fine-grained, high-frequency spectral details (such as subtle anomaly absorption features). It employs a linear combination of B-spline basis functions. The spline transformation

expands each scalar input

x into a set of basis responses:

where

represents the

i-th B-spline basis function of order

(cubic) defined on a grid of size

, and

are the learnable control coefficients implicitly contained within

. This formulation enables the network to learn a custom, non-monotonic activation shape for every spectral feature dimension, effectively creating an adaptive spectral index.

- (3)

Integration and Weighting: The outputs of the two paths are fused via element-wise addition, as shown in Equation (

3). This additive coupling allows the network to automatically weight the contribution of each path during training: the matrix

learns the coarse structural relationships, while

refines the feature space by capturing complex non-linear deviations. Finally, the complete KAN-MLP block within the Transformer is defined as follows:

where

represents the dual-path operations described above and LN denotes layer normalization.

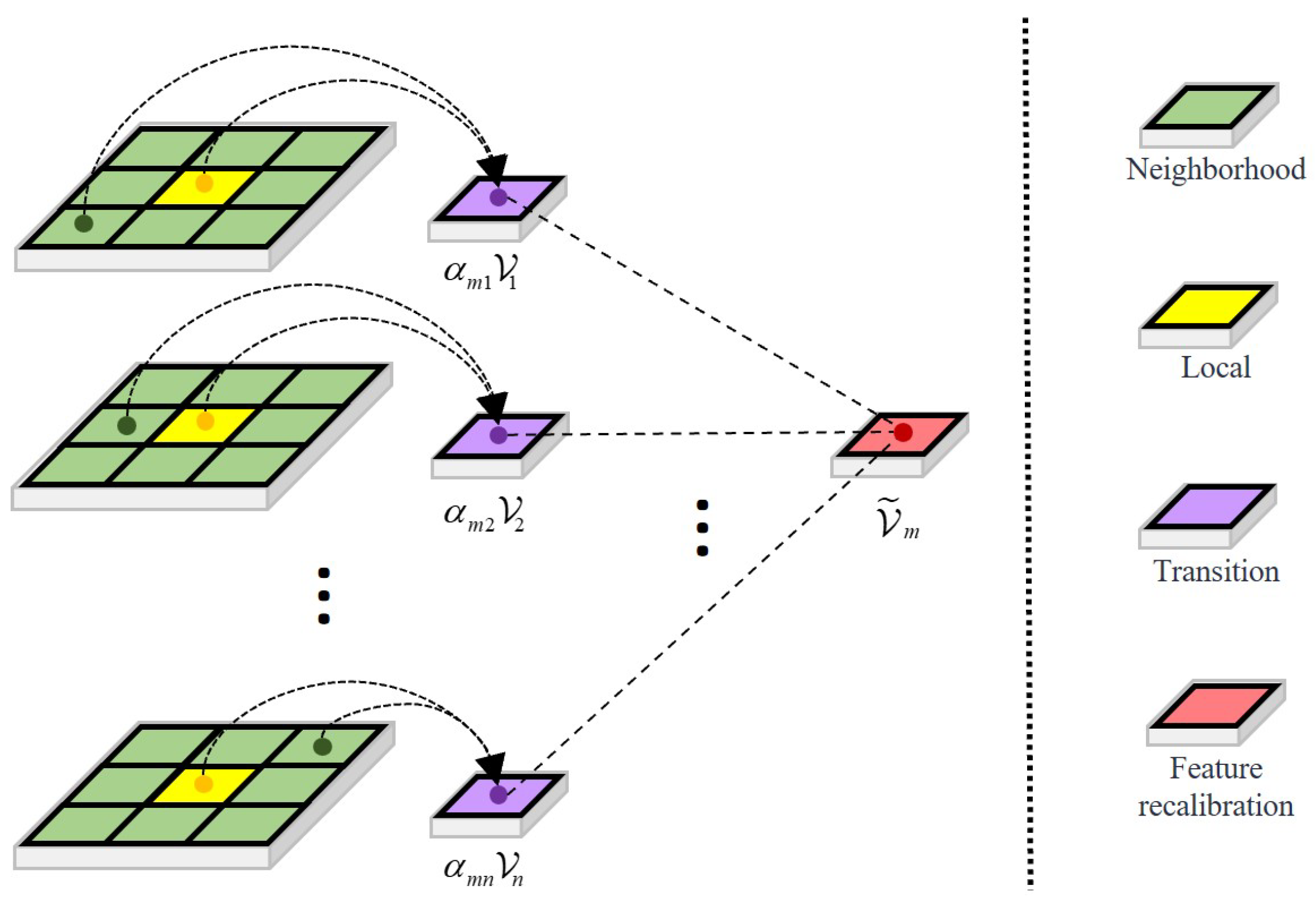

3.2.3. Local Anomaly Recognition Branch

The LARB targets anomalous region suppression through local context analysis and feature recalibration. Input features are decomposed into non-overlapping patches of dimension , with .

Inter-patch affinity computation employs learned projections:

where

implements dimensional reduction.

Normalized attention weights are obtained through the softmax operation:

where

denotes neighborhood indices and

is the selectivity parameter that governs the concentration of the normalized attention weights, effectively adjusting the trade-off between local averaging and sharp feature focusing.

Feature recalibration aggregates contextual information:

The output tensor

is reconstructed by reassembling recalibrated patches. The process of the LARB is shown in

Figure 3.

3.2.4. Global Background Recognition Branch

The GBRB enhances background representation through global attention mechanisms. Input is partitioned into patches and reshaped to .

The self-attention computation employs shared projections:

where

shares parameters with

to maintain consistency.

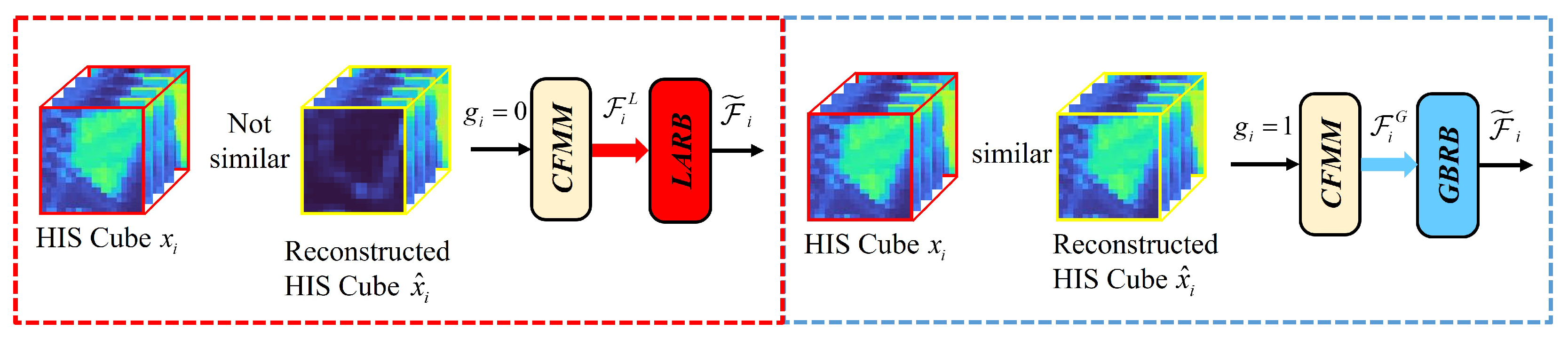

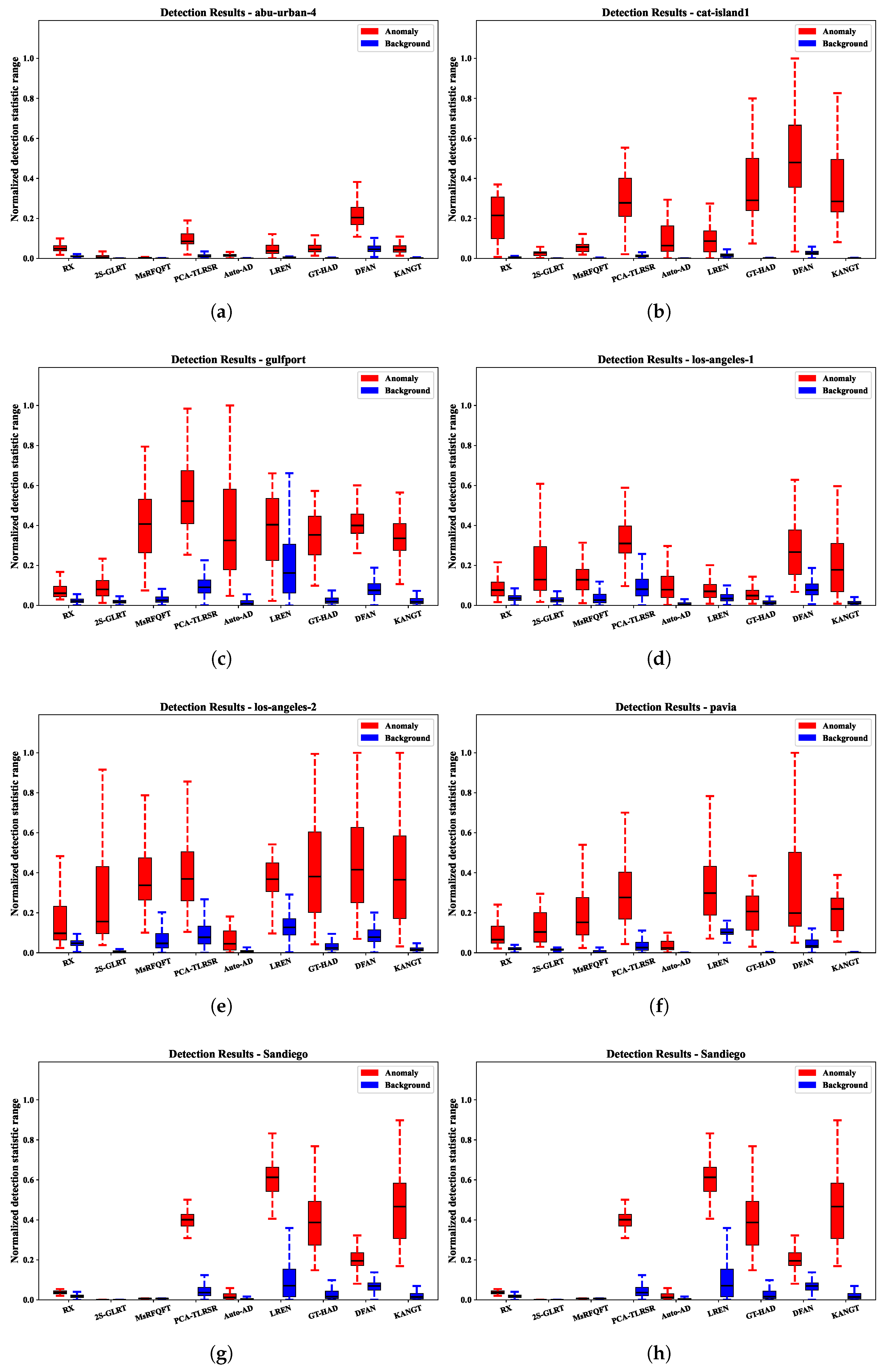

3.3. Contextual Feature Matching Module

The CFMM is a core innovation of KANGT, designed to explicitly address the “uniform processing” limitation inherent in standard Transformer architectures. Its function is to dynamically route input cubes to the branch best suited for their content (background or anomaly) based on an interpretable, data-driven measure of reconstruction fidelity.

Unlike other gated architectures that may rely on learned soft-attention weights or implicit “adaptive gating units,” the CFMM provides an explicit, fidelity-based routing decision. The module operates on the central hypothesis of reconstruction-based HAD: background patches, which constitute the majority of the data, can be reconstructed by the network with high fidelity, whereas anomalous patches, due to their statistical rarity, cannot. The CFMM leverages this disparity to segregate the data streams.

The gating mechanism is not static; it is updated iteratively throughout the training process, as detailed in Algorithm 1. Initially, all gating states in are initialized to zero (), forcing all input cubes through the LARB. This allows the network to first learn a general-purpose representation focused on suppressing hard-to-reconstruct (potentially anomalous) features.

At periodic intervals (e.g., every

iterations), the CFMM re-evaluates the gating state for each training cube

. This evaluation is a direct assessment of reconstruction fidelity. For a given reconstructed cube

, the module computes its Euclidean distance to all original cubes

in the dataset (or a representative subset):

The module then identifies the index

of the nearest neighbor (i.e., the most similar original cube) to the reconstruction

:

The gating signal

is then updated based on a strict fidelity criterion. The gate

is set to 1 (route to the GBRB) if and only if the reconstruction

is closer to its own original input

than to any other original cube

. This indicates that the model has successfully and uniquely identified its background pattern.

where

is the indicator function. A gate value of

signifies high reconstruction fidelity (assumed background), routing the cube to the GBRB. Conversely, a value of

signifies low fidelity (a potential anomaly or highly complex/unique background patch), retaining the cube in the LARB.

This dynamic interaction between the CFMM and the GCAT dual branches creates the “self-improving loop” that is central to our design. As training progresses, the model’s reconstruction quality for background patches improves. The CFMM identifies these high-fidelity cubes and progressively redirects them to the GBRB. This action allows the GBRB to specialize its parameters for modeling a pure, global background. Concurrently, this specialization purges the LARB of simple background patches, enabling it to focus its representational power exclusively on suppressing the reconstruction of challenging, low-fidelity anomalous regions. This explicit, fidelity-based specialization is the key mechanism by which KANGT separates the background and anomaly representations. The specific CMM procedure is illustrated in

Figure 4.

3.4. Anomaly Detection and Residual Enhancement

The anomaly detection process is initiated by analyzing the reconstruction residuals, which capture the pixel-wise squared error between the input cube and its reconstruction . This yields an initial 3D residual tensor .

To mitigate boundary artifacts and enhance detection sensitivity, we first employ a multi-scale residual diffusion strategy on this 3D tensor. This enhanced residual

is computed by averaging 3D average-pooled features across multiple spatial and spectral scales, which improves anomaly localization while suppressing false alarms in homogeneous regions:

Following this 3D enhancement, spectral aggregation is performed on the diffused residual tensor

to collapse the spectral dimension and produce 2D anomaly scores

:

Finally, the composite anomaly map

is generated through the spatial fusion of all overlapping 2D score patches derived from the entire HSI cube:

where

implements an overlapping region averaging strategy to produce the final, coherent detection map.