Vegetation Changes and Its Driving Factors in the Three-River Headwaters Region from 1990 to 2022

Highlights

- Vegetation coverage in Three-River Headwaters rose, with high coverage areas up 10.3%.

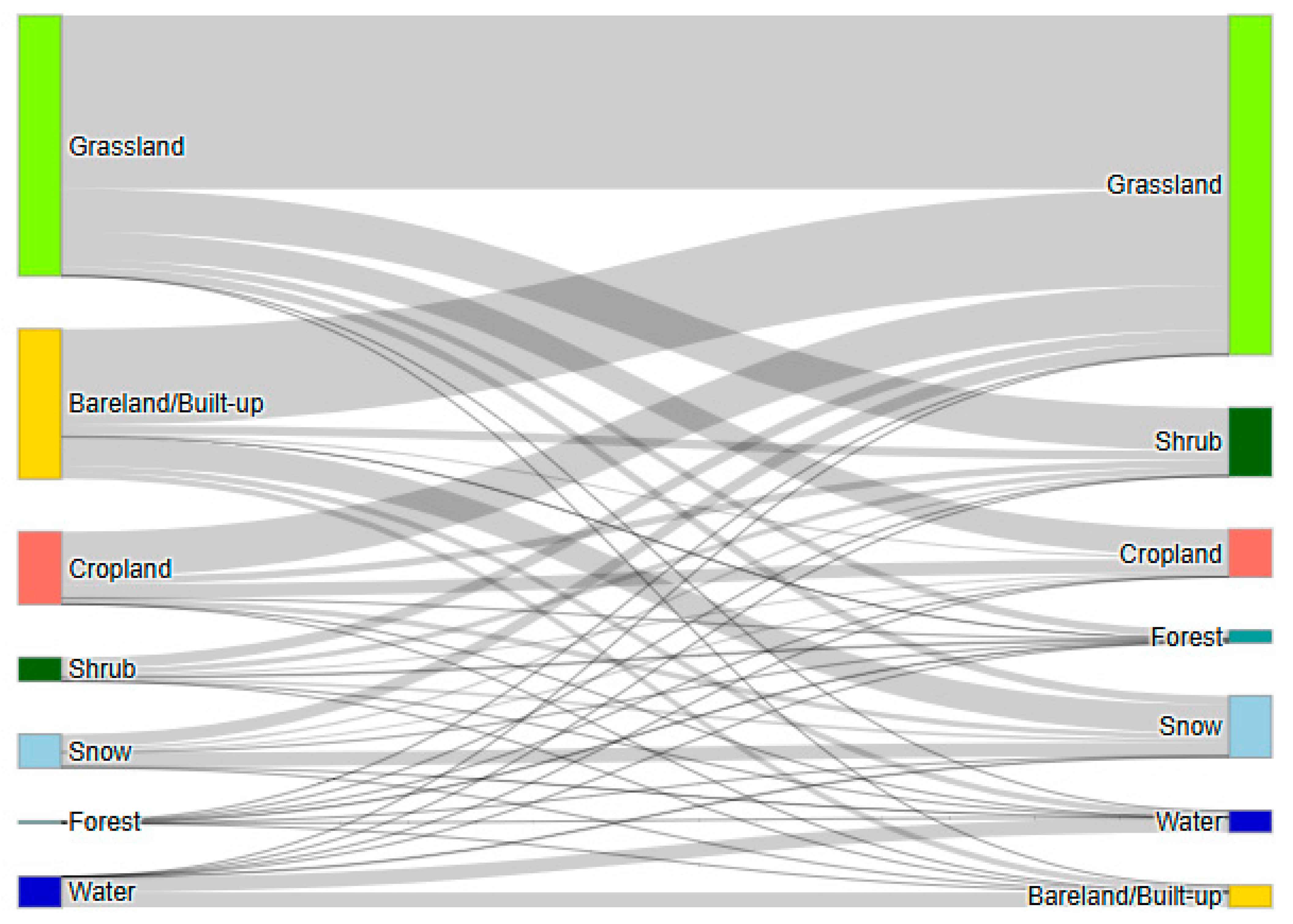

- Bare land down-shifted to grassland and shrubs, forests, and grassland significantly upshifted.

- This study offers a scientific foundation for monitoring and ecological conservation.

- We reveal the dynamic changes of vegetation and environmental driving mechanisms.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Research Data and Methods

3. Results

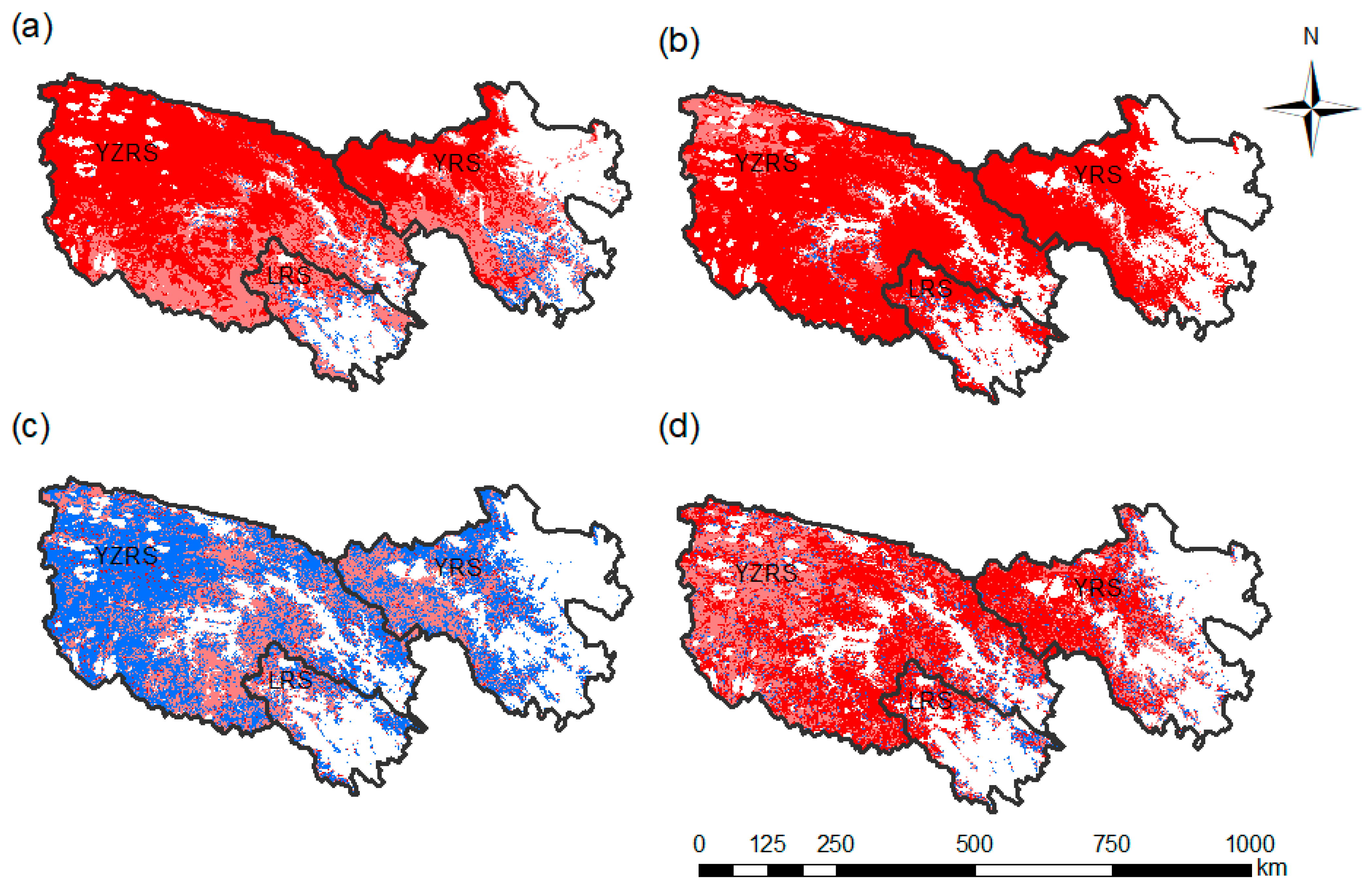

3.1. Vegetation Coverage and Its Recent Changes in the TRH Region

3.2. Land Cover Changes in the TRH Region

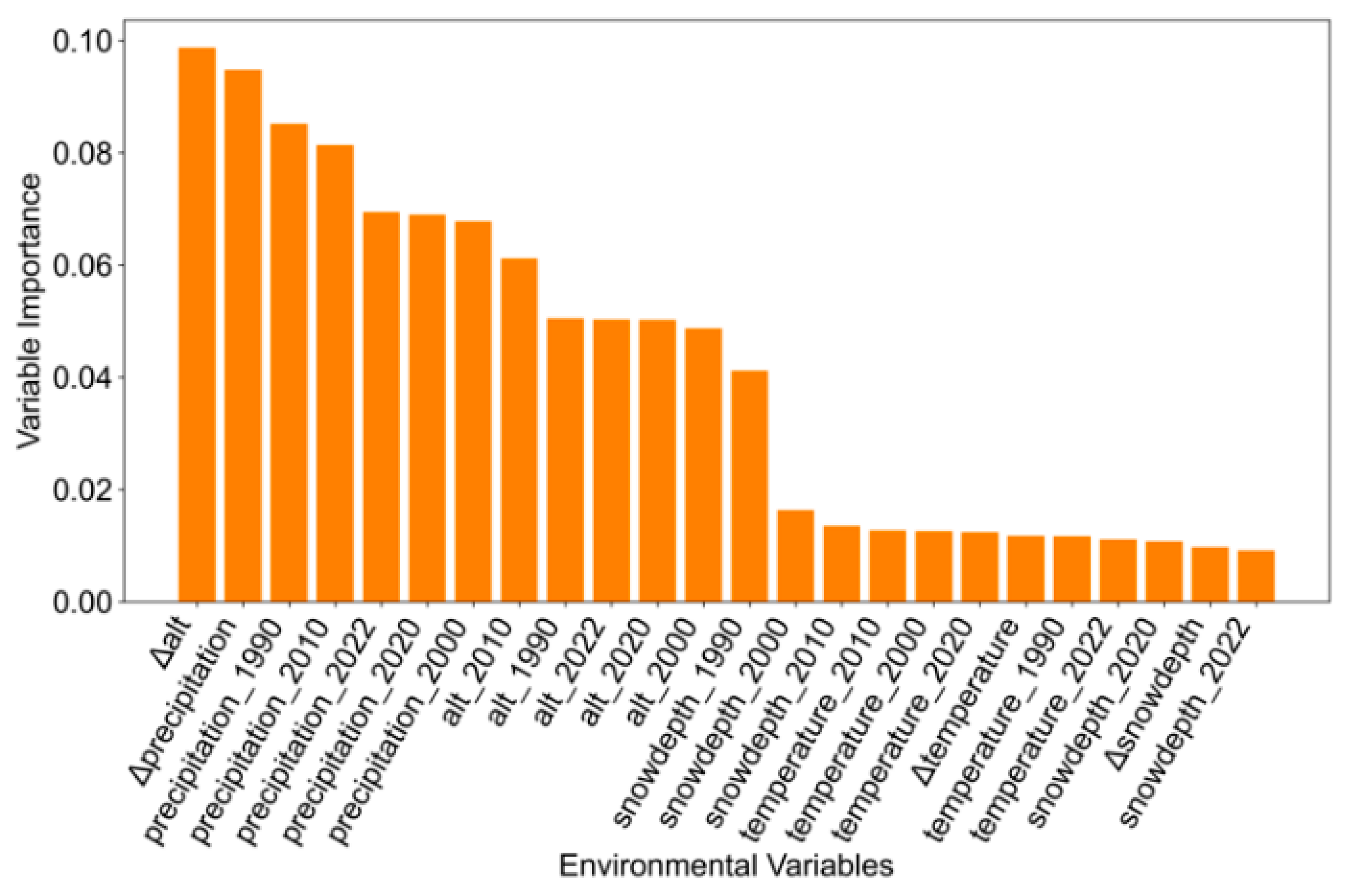

3.3. The Driving Forces Behind Vegetation Coverage

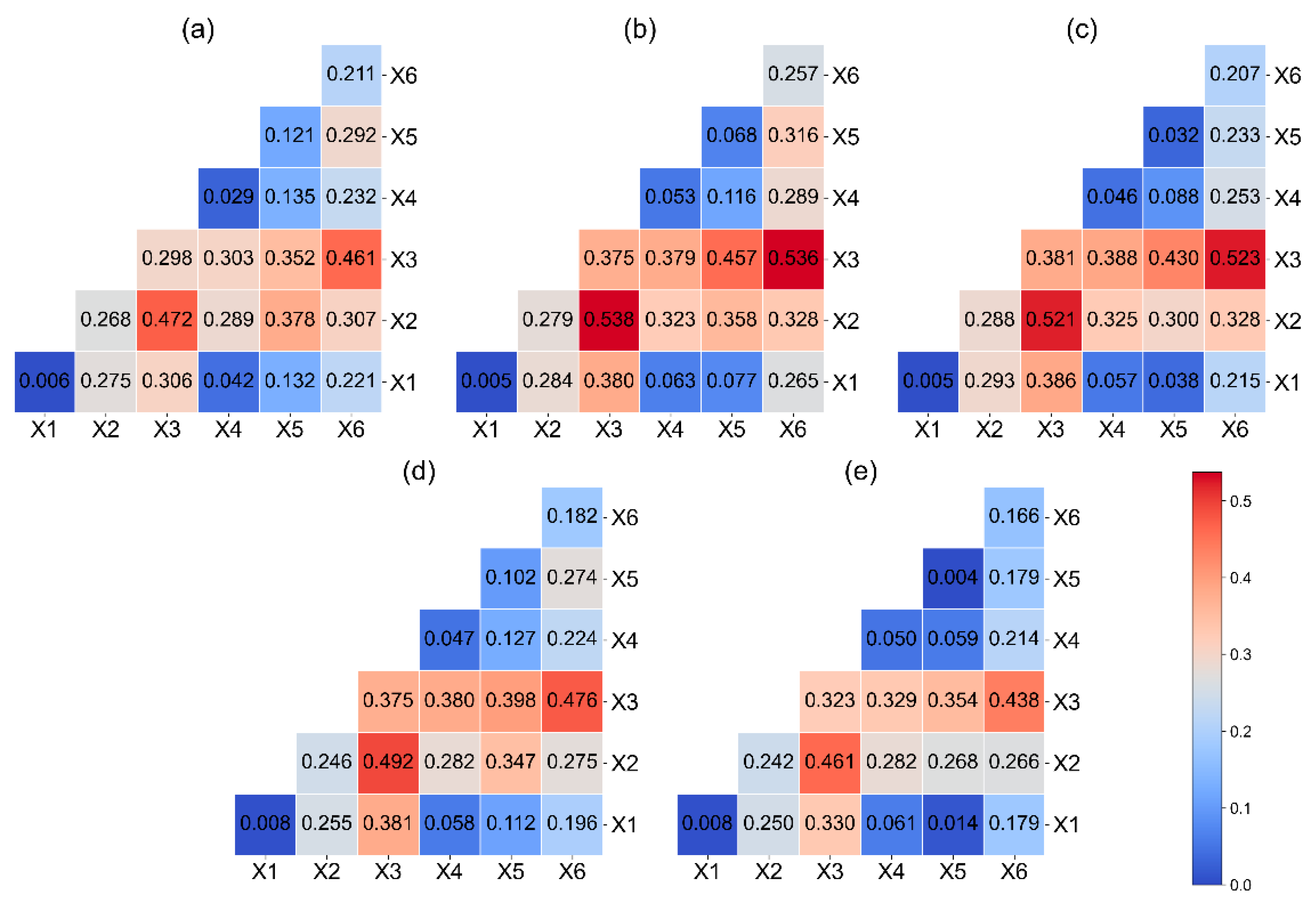

3.4. The Contribution of Environmental Factors to Vegetation Cover Change

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- Overall, the computational performance of Google Earth Engine was satisfactory, clearly revealing the vegetation coverage levels in the TRH region, exhibiting a spatial distribution pattern of “higher in the east and lower in the west”. Vegetation coverage in the TRH region also showed an overall increasing trend. Bare land in the western part of the region has markedly decreased, transforming into grassland, while the areas of forest and shrubland have shown an increasing trend. A 30 m spatial resolution was adopted in the mapping process, enabling more accurate characterization of the spatial distribution and fine-scale dynamics of vegetation, particularly in the topographically complex and vegetation-heterogeneous TRH region.

- (2)

- Based on geographical detector analysis, we reveal that precipitation, elevation, and temperature have considerable influence on the spatial differentiation of vegetation coverage in the TRH region. The thickening of the active layer of the permafrost and precipitation contribute substantially to the increase in vegetation coverage.

- (3)

- Utilizing a deep neural network to identify land cover conditions, this research clarifies the types and area changes in land cover in the TRH region over the past thirty years and evaluates the applicability of deep neural networks for land cover classification in this area. However, deep neural networks suffer from several limitations, including a heavy reliance on large volumes of labeled training data and poor interpretability. Future studies could employ more advanced algorithms to address these challenges. In addition, relevant Earth system models can be further used to simulate the ecological processes of the TRH region, providing a more scientific basis for ecological protection and restoration in the area.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, X.; Pei, Q.S.; Chen, Y.; Guo, Y.; Hou, Y.; Sun, R. Temporal and Spatial Changes Monitoring of Vegetation Coverage in Qilian County Based on GF-1 Image. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2019, 162, 662–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, J.; Wang, H.; Han, L.; Li, J.; Sun, Z. Vegetation Coverage Prediction for the Qinling Mountains Using the CA-Markov Model. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2021, 10, 679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, D.; Fu, M.; Sun, Y.; Bao, W.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, J. How Large-Scale Anthropogenic Activities Influence Vegetation Cover Change in China? A Review. Forests 2021, 12, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Di, Z.; Yao, Y.; Ma, Q. Variations in water conservation function and attributions in the Three-River Source Region of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau based on the SWAT model. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2024, 349, 109956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Xue, D.; Dai, L.; Wang, P.; Huang, X.; Xia, S. Land cover change and eco-environmental quality response of different geomorphic units on the Chinese Loess Plateau. J. Arid. Land. 2020, 12, 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, D. Fractional vegetation cover extraction based on visible light images of U.A.V. Stand. Surv. Mapp. 2024, 40, 35–43. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.Q.; Wang, G.J.; Liang, S.H.; Du, H.; Peng, H. Extraction and spatio-temporal analysis of vegetation coverage from 1996 to 2015 in the source region of the Yellow River. J. Glaciol. Geocryol. 2021, 43, 662–674. [Google Scholar]

- Yue, Y.; Chen, G.; Wang, L.; Li, X.; Li, T. Analyses of Vegetation Coverage Changes in Zhouqu County from 1998 to 2019 Based on GEE Platform. Acta Agrestia Sin. 2022, 30, 1534–1542. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Yan, D.; Weng, B.; Lai, Y.; Bi, W.; Zhu, L.; Dong, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wang, H. Thickened active layer contribute less to vegetation growth over the Tibetan Plateau. J. Hydrol. 2025, 663, 134221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, T.; Tong, X.; Duan, L.; Jia, T.; Ji, Y. Inversion of vegetation coverage based on multi-source remote sensing data and machine learning method in the Horqin Sandy Land, China. J. Desert Res. 2022, 42, 187–195. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Q.; Yang, X.; Hao, L. Spatio-temporal variation of vegetation cover and its driving factors in Three-River headwaters region during 2001-2020. Bull. Soil Water Conserv. 2022, 42, 202–212. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Q.; Li, B.; Xu, L.; Zhang, T.; Ge, J.; Li, F. Analysis of NDVI change trend and its impact factors in the Three-River Headwater Region from 2000 to 2013. J. Geo-Inf. Sci. 2016, 18, 1707–1716. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, K.; Jiang, W.; Hou, P.; Sun, C.; Zhao, X.; Xiao, R. Spatiotemporal variation of vegetation coverage and its affecting factors in the Three river-source National Park. Chin. J. Ecol. 2020, 39, 3388–3396. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Zhao, H.; Luo, Y.; Yuan, Z. A Review of Deep Learning in Hyperspectral Remote Sensing of Vegetation. Remote Sens. Inf. 2024, 39, 11–22. [Google Scholar]

- Tamiminia, H.; Salehi, B.; Mahdianpari, M.; Quackenbush, L.; Adeli, S.; Brisco, B. Google Earth Engine for geo-big data applications: A meta-analysis and systematic review. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2020, 164, 152–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dezfooli, F.P.; Zoej, M.J.V.; Mansourian, A.; Youssefi, F.; Pirasteh, S. GEE-based environmental monitoring and phenology correlation investigation using Support Vector Regression. Remote Sens. Appl. Soc. Environ. 2025, 37, 101445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sowrav, S.F.F.; Debsarma, S.K.; Das, M.K.; Ibtehal, K.M.; Rahman, M.; Hridita, N.T.; Broty, A.A.; Hoque, M.S.A. Developing a semi-automated technique of surface water quality analysis using GEE and machine learning: A case study for Sundarbans. Heliyon 2025, 11, e42404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, L.; Li, B.; Zhu, S.; Yuan, Q.; Shen, H. A fully automatic and high-accuracy surface water mapping framework on Google Earth Engine using Landsat time-series. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2023, 16, 210–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, X.; Pan, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, D.; Lin, Z. Spatiotemporal changes in vegetation coverage and its driving factors in the Three-River Headwaters Region during 2000–2011. J. Geogr. Sci. 2014, 24, 288–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, F.; Yao, Y.; Li, Y.; Yu, R.; Fan, J.; Zhang, X.; Kan, Y.; Liu, L.; Xie, Z.; Ning, J.; et al. Satellite-Derived Spatiotemporal Dynamics of Vegetation Cover and Its Driving Factors in the Three-River Headwaters Region from 2001 to 2022. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Jia, N. Patterns, Trends, and Causes of Vegetation Change in the Three Rivers Headwaters Region. Land 2023, 12, 1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z.; Brahney, J.; Kang, S.; Elser, J.; Wei, T.; Jiao, X.; Shao, Y. Aeolian dust transport, cycle and influences in high-elevation cryosphere of the Tibetan Plateau region: New evidences from alpine snow and ice. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2020, 211, 103408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.; Fan, W.; Shan, Y.; Gao, Y.; Liu, C.; Nie, R.; Zhang, D.; Li, W.; Zhang, L.; Sun, X.; et al. LAI-based phenological changes and climate sensitivity analysis in the Three-River Headwaters Region. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 3748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, M.; Yu, D.; Dong, W.; Huang, T.; Li, X. Shift regime of multiphase water in the Three-River-Source Region. J. Hydrol. 2025, 661, 133582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Wang, J.; Zhang, M.; Tang, Q. Characterizing and attributing the vegetation coverage changes in North Shanxi coal base of China from 1987 to 2020. Resour. Policy 2021, 74, 102331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulaby, F.T.; Kouyate, F.; Brisco, B.; Williams, T.H.L. Textural Information in SAR Images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 1986, 24, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woebbecke, D.M.; Meyer, G.E.; Von Bargen, K.; Mortensen, D.A. Color indices for weed identification under various soil, residue, and lighting conditions. Trans. ASAE 1995, 38, 259–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, G.E.; Hindman, T.W.; Laksmi, K. Machine vision detection parameters for plant species identification. Precis. Agric. Biol. Qual. 1999, 3543, 327–335. [Google Scholar]

- Guijarro, M.; Pajares, G.; Riomoros, I.; Herrera, P.J.; Burgos-Artizzu, X.P.; Ribeiro, A. Automatic segmentation of relevant textures in agricultural images. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2011, 75, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.J.; Meng, J.J.; Zhu, L.K. Applying Geodetector to disentangle the contributions of natural and anthropogenic factors to NDVI variations in the middle reaches of the Heihe River Basin. Ecol. Indic. 2020, 117, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Xu, C. Geodetector: Principle and prospective. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2017, 72, 116–134. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, D.; Zheng, X.; Feng, M.; Liang, S.; Hu, Z.; Kuang, X.; Feng, Y. Frozen Ground Change Data Set in the Tibetan Plateau (1961–2020). National Tibetan Plateau/Third Pole Environment Data Center. 2023. Available online: https://data.tpdc.ac.cn/zh-hans/data/e03ae441-0af2-4f57-b5b0-0a4f368f4015 (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Wang, B.; Si, J.; Jia, B.; He, X.; Zhou, D.; Zhu, X.; Liu, Z.; Ndayambaza, B.; Bai, X. Monitoring Spatial-Temporal Variability of Vegetation Coverage and Its Influencing Factors in the Yellow River Source Region from 2000 to 2020. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 4772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Feng, Z. Analysis of cause mechanism of desertification in headwater area of Yellow River. J. Nat. Disasters 2009, 18, 45–52. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, Q.; Cao, W.; Fan, J.; Lin, H.; Xu, X. Effects of an ecological conservation and restoration project in the Three-River Source Region, China. J. Geogr. Sci. 2017, 27, 183–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yao, X.; Zhou, S.; Zhang, D. A glacier vector dataset in the Three-River Headwaters region during 2000–2019. Sci. Data Bank 2021, 6, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, X.; Liang, X.; Yan, C.; Xing, X.; Jia, H.; Wei, X.; Feng, K. Vegetation dynamic changes and their response to ecological engineering in the Sanjiangyuan Region of China. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 4035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Zhao, D.; Zhang, G.; Wu, X.; Yi, Y.; Wang, Z. Using SPOT VEGETATION for analyzing dynamic changes and influencing factors on vegetation restoration in the Three-River Headwaters Region in the last 20 years (2000–2019), China. Ecol. Eng. 2022, 183, 106742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zhang, W.; Yi, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Chao, S. Long Time-Series Glacier Outlines in the Three-Rivers Headwater Region From 1986 to 2021 Based on Deep Learning. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2022, 15, 5734–5752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Jin, X. Vegetation dynamics and responses to climate change and anthropogenic activities in the Three-River Headwaters Region, China. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 131, 108223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.L.; Cao, X.Q.; Ji, Q. Glacier monitoring studies of Dongkemadi basin from 1990-2020. Bull. Surv. Mapp. 2024, 4, 61–68. [Google Scholar]

- Nan, Y.; Tian, F.; McDonnell, J.; Ni, G.; Tian, L.; Li, Z.; Yan, D.; Xia, X.; Wang, T.; Han, S.; et al. Glacier meltwater has limited contributions to the total runoff in the major rivers draining the Tibetan Plateau. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 2025, 8, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; He, S.; Yi, H.; Zheng, Z. Study on the spatial and temporal changes of the vegetation cover and the driving factors in Panzhihua City from 1990 to 2020. J. Soil Water Conserv. 2025, 39, 368–376. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, B.; Li, X.; Zhang, D.; Shen, Y. Study on spatiotemporal changes of the freeze-thaw status of seasonally frozen ground and influencing factors in the Three Rivers Source Region from 1961 to 2019. J. Glaciol. Geocryol. 2023, 45, 382–394. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, M.; Pang, W.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, C.; Zhang, L. Spatio-temporal variation of freezing-thawing state of near surface soil in the Three-Rivers HeadWater region of Tibetan Plateau, China. Mt. Res. 2024, 42, 347–358. [Google Scholar]

- Long, D.; Li, X.; Wu, Y.; Cui, Y.; Tian, F.; Duan, X.; Xu, X. Spatial disparity in runoff variability between Southwestern China’s River Basin headwaters during 1981–2020. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2024, 69, 3821–3830. [Google Scholar]

| 1990 | 2000 | 2010 | 2020 | 2022 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Accuracy | 87.86% | 91.09% | 88.64% | 90.00% | 86.08% |

| Potential Driving Factor | 1990 | 2000 | 2010 | 2020 | 2022 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| q-Statistic | p-Value | q-Statistic | p-Value | q-Statistic | p-Value | q-Statistic | p-Value | q-Statistic | p-Value | |

| temperature | 21.06% | <0.001 | 25.75% | <0.001 | 20.66% | <0.001 | 18.20% | <0.001 | 16.56% | <0.001 |

| snow depth | 12.09% | <0.001 | 6.79% | <0.001 | 4.20% | <0.001 | 10.16% | <0.001 | 6.35% | <0.001 |

| precipitation | 29.84% | <0.001 | 37.52% | <0.001 | 38.06% | <0.001 | 37.54% | <0.001 | 32.31% | <0.001 |

| elevation | 26.81% | <0.001 | 27.86% | <0.001 | 28.79% | <0.001 | 24.58% | <0.001 | 24.17% | <0.001 |

| slope | 2.85% | <0.001 | 5.29% | <0.001 | 4.57% | <0.001 | 4.67% | <0.001 | 4.98% | <0.001 |

| aspect | 0.62% | <0.001 | 0.49% | <0.001 | 0.50% | <0.001 | 0.82% | <0.001 | 0.82% | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, C.; Wang, J.; Dong, Z.; Wang, S.; Jiao, X. Vegetation Changes and Its Driving Factors in the Three-River Headwaters Region from 1990 to 2022. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3947. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243947

Wang C, Wang J, Dong Z, Wang S, Jiao X. Vegetation Changes and Its Driving Factors in the Three-River Headwaters Region from 1990 to 2022. Remote Sensing. 2025; 17(24):3947. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243947

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Chen, Junbang Wang, Zhiwen Dong, Shaoqiang Wang, and Xiaoyu Jiao. 2025. "Vegetation Changes and Its Driving Factors in the Three-River Headwaters Region from 1990 to 2022" Remote Sensing 17, no. 24: 3947. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243947

APA StyleWang, C., Wang, J., Dong, Z., Wang, S., & Jiao, X. (2025). Vegetation Changes and Its Driving Factors in the Three-River Headwaters Region from 1990 to 2022. Remote Sensing, 17(24), 3947. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243947