Accuracy Assessment of Shoreline Extraction Using MLS Data from a USV and UAV Orthophoto on a Complex Inland Lake

Highlights

- Both UAV photogrammetry and MLS from USV met the IHO Special Order accuracy requirement for shoreline extraction.

- UAV data provided sub-decimetre shoreline position accuracy (0.05–0.06 m), while MLS achieved 1.16 m, confirming the complementary nature of both methods.

- UAV is suitable for accurate shoreline mapping and identification of hydrotechnical structures, whereas MLS is useful for surveying of vegetated and hard-to-access areas.

- Integration of UAV and MLS data enables a more comprehensive and reliable representation of complex shorelines, supporting hydrographic surveys, environmental monitoring, and water management.

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Importance of Accurate Shoreline Extraction

1.2. Measurement Challenges in the Nearshore Zone

1.3. State of the Art and Research Gaps

- The lack of comprehensive comparisons between MLS and UAV in inland lakes with complex shoreline morphology;

- Insufficient evaluation of MLS performance under challenging environmental conditions, such as dense vegetation and anthropogenic obstacles;

- Limited adaptation of shoreline extraction algorithms developed for ALS, including the method of Xu et al. [44], to MLS data;

- The absence of studies verifying whether MLS and UAV meet the accuracy requirements of the IHO Special Order;

- Limited evaluation of the relative advantages of MLS and UAV for high-precision shoreline determination.

1.4. Rationale and Novelty of the Study

- The use of a modified Xu et al. algorithm [44], originally developed for ALS, specifically adapted to MLS data acquired at low-altitude above the water surface using a USV;

- An assessment of whether MLS and UAV methods meet the accuracy requirements of the IHO Special Order, which is essential for high-precision hydrographic surveying;

- An analysis of the complementary advantages of both sensors, demonstrating that MLS outperforms UAV photogrammetry in shaded or vegetated areas, while UAV imagery provides higher geometric accuracy and improved interpretation of hydrotechnical structures.

1.5. Research Objectives and Article Structure

- To assess the geometric accuracy of shorelines derived from MLS and UAV data;

- To evaluate the performance of the modified shoreline extraction algorithm applied to MLS data;

- To compare the derived shorelines with GNSS RTK reference measurements;

- To determine whether the MLS- and UAV-derived results meet the accuracy requirements of the IHO Special Order;

- To identify environmental and data-related factors affecting the precision of shoreline determination;

- To formulate recommendations for the use of MLS and UAV photogrammetry in the shoreline extraction process.

2. Materials and Methods

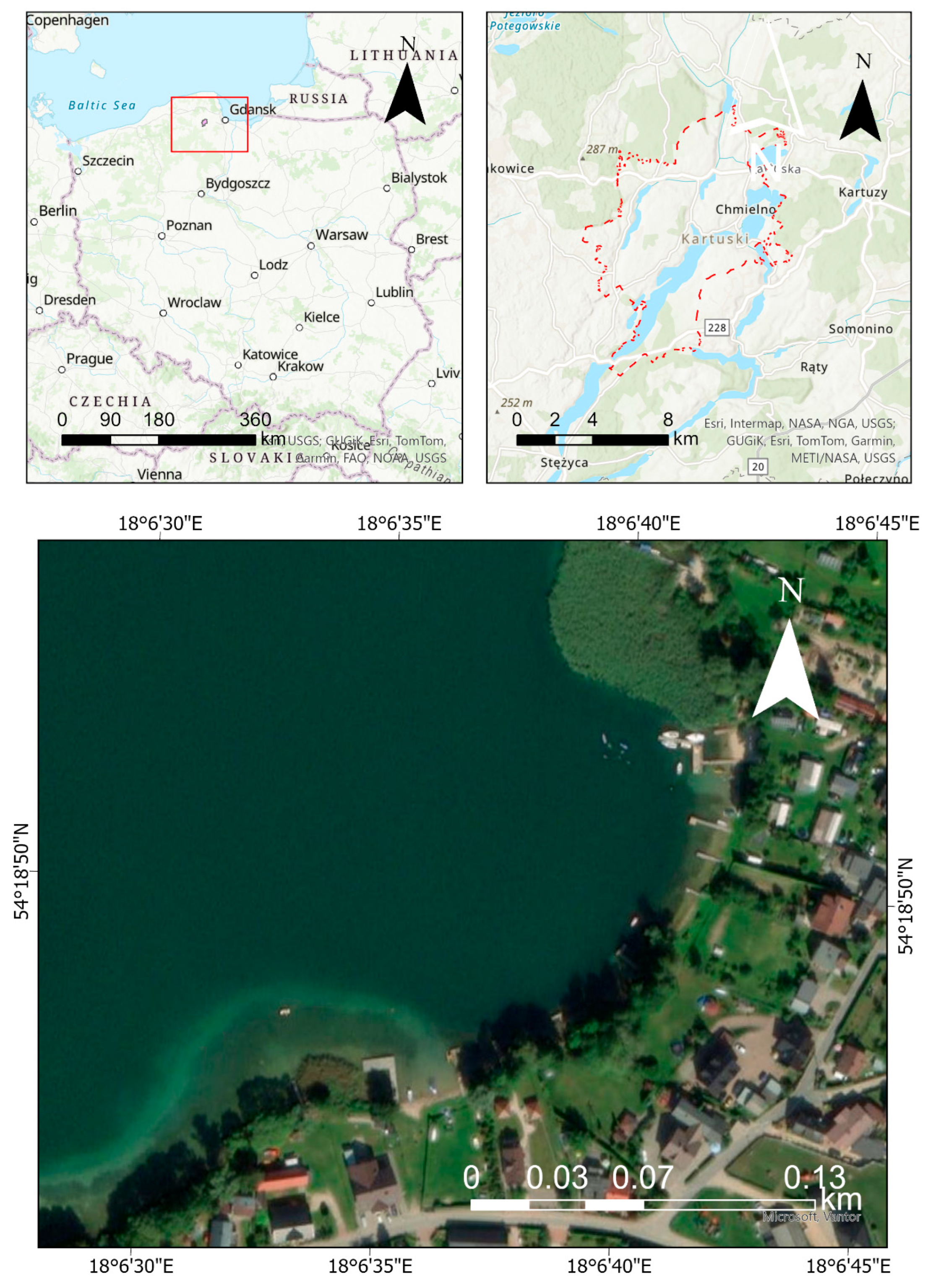

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Measurement Equipment

- USV HydroDron-1—a catamaran measuring 4 × 2 × 0.5 m and weighing approximately 300 kg. It was designed under the supervision of Prof. Andrzej Stateczny as a versatile platform for hydrographic and geodetic tasks. It is equipped with a mast carrying automatically folding navigation sensors, a hydrographic head mounted on a movable actuator, and an SVP deployed via an anchor winch. Additional onboard sensors include rotating and fixed video cameras as well as a meteorological station [45].

- In this study, two devices were essential: the Velodyne VLP-16 Puck laser scanner, mounted on the USV mast and used for mobile laser scanning, and the SBG Ekinox2-U GNSS/INS system, which ensured precise determination of the LiDAR’s position and orientation. The Velodyne VLP-16 provides 16 laser channels, a maximum range of 100 m, a ranging accuracy of ±3 cm, a 360° horizontal field of view, and a scanning frequency adjustable between 5 and 20 Hz. The SBG Ekinox2-U GNSS/INS system offers centimetre-level positioning accuracy and full 3D orientation determination. The HydroDron-1 USV performing MLS measurements is shown in Figure 2a [46].

- UAV Aurelia X8 Standard LE—an octocopter equipped with a prototype optoelectronic module. The module was developed as part of the INNOBAT project [47] and was intended for the acquisition of geospatial data in coastal zones. The module consisted of a Sony A6500 digital camera with a Sony E 35 mm f/1.8 OSS lens, integrated with a Gremsy T3V3 gimbal and controlled by an AIR Commander Entire controller. In addition, the system included a Velodyne Puck LITE laser scanner integrated with an SBG Ellipse-D GNSS/INS system, an AAEON PICO-WHU-4 onboard computer, an Alcatel LTE modem, and communication and power-supply modules.

- The digital camera was essential in this study, as it enabled the acquisition of a series of aerial images of the nearshore zone. The Sony A6500 features a 24.2 MP APS-C sensor (6000 × 4000 px) and a 35 mm focal-length lens, providing high-resolution nadir imagery suitable for photogrammetric processing. The prototype optoelectronic module mounted on the UAV is shown in Figure 2b.

2.3. Measurement Campaign

2.4. Data Processing

3. Results

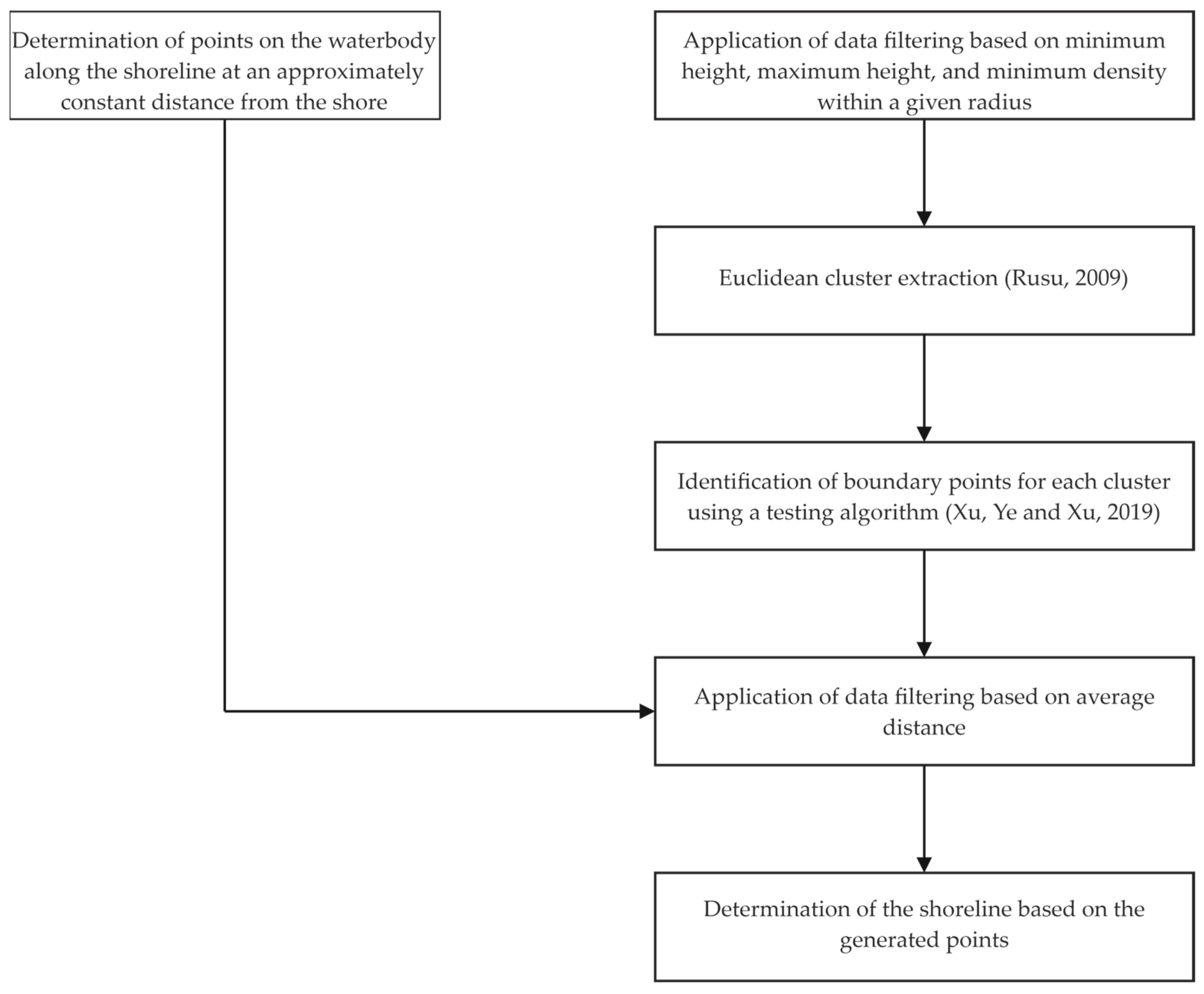

3.1. Shoreline Extraction from MLS Data

3.2. Shoreline Extraction from the UAV Orthophoto

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ALS | airborne laser scanning |

| DSM | digital surface model |

| GCP | ground control point |

| GIOŚ | Chief Inspectorate of Environmental Protection (Poland) |

| GIS | geographic information system |

| GNSS | global navigation satellite system |

| GSD | ground sample distance |

| IHO | International Hydrographic Organization |

| IMGW-PIB | Institute of Meteorology and Water Management—National Research Institute |

| INNOBAT | Innovative Autonomous Unmanned System for Bathymetric Monitoring of Shallow Waterbodies |

| INS | inertial navigation system |

| LiDAR | light detection and ranging |

| MLS | mobile laser scanning |

| RTK | real time kinematic |

| SVP | sound velocity profiler |

| UAV | unmanned aerial vehicle |

| USV | unmanned surface vehicle |

| σ | standard deviation |

References

- Boak, E.H.; Turner, I.L. Shoreline Definition and Detection: A Review. J. Coast. Res. 2005, 21, 688–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toure, S.; Diop, O.; Kpalma, K.; Maiga, A.S. Shoreline Detection Using Optical Remote Sensing: A Review. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2019, 8, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luijendijk, A.; Hagenaars, G.; Ranasinghe, R.; Baart, F.; Donchyts, G.; Aarninkhof, S. The State of the World’s Beaches. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 6641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicholls, R.J.; Cazenave, A. Sea-Level Rise and Its Impact on Coastal Zones. Science 2010, 328, 1517–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockdon, H.F.; Sallenger, A.H., Jr.; List, J.H.; Holman, R.A. Estimation of Shoreline Position and Change Using Airborne Topographic Lidar Data. J. Coast. Res. 2002, 18, 502–513. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Wang, L.; Feng, S.; Peng, B.; Huang, L.; Fatholahi, S.N.; Tang, L.; Li, J. An Overview of Shoreline Mapping by Using Airborne LiDAR. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K.E.L.; Terrano, J.F.; Pitchford, J.L.; Archer, M.J. Coastal Wetland Shoreline Change Monitoring: A Comparison of Shorelines from High-Resolution WorldView Satellite Imagery, Aerial Imagery, and Field Surveys. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 3030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wantzen, K.M.; Rothhaupt, K.-O.; Mörtl, M.; Cantonati, M.; Tóth, L.G.; Fischer, P. Ecological Effects of Water-Level Fluctuations in Lakes: An Urgent Issue. Hydrobiologia 2008, 613, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adagbasa, E.G.; Samuel, K.J.; Durowoju, O.S.; Obidiya, M.O. Drowning in the Sea: A Digital Shoreline Analysis of Coastline Changes in Ilaje, Nigeria. Pap. Appl. Geogr. 2024, 10, 301–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuleli, T.; Guneroglu, A.; Karsli, F.; Dihkan, M. Automatic Detection of Shoreline Change on Coastal Ramsar Wetlands of Turkey. Ocean Eng. 2011, 38, 1141–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Specht, M.; Specht, C.; Lewicka, O.; Makar, A.; Burdziakowski, P.; Dąbrowski, P. Study on the Coastline Evolution in Sopot (2008–2018) Based on Landsat Satellite Imagery. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2020, 8, 464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yermolaev, O.; Usmanov, B.; Gafurov, A.; Poesen, J.; Vedeneeva, E.; Lisetskii, F.; Nicu, I.C. Assessment of Shoreline Transformation Rates and Landslide Monitoring on the Bank of Kuibyshev Reservoir (Russia) Using Multi-Source Data. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 4214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taveneau, A.; Almar, R.; Bergsma, E.W.J.; Sy, B.A.; Ndour, A.; Sadio, M.; Garlan, T. Observing and Predicting Coastal Erosion at the Langue de Barbarie Sand Spit around Saint Louis (Senegal, West Africa) through Satellite-Derived Digital Elevation Model and Shoreline. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 2454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warrick, J.A.; Buscombe, D.; Vos, K.; Bryan, K.R.; Castelle, B.; Cooper, J.A.G.; Harley, M.D.; Jackson, D.W.T.; Ludka, B.C.; Masselink, G.; et al. Coastal Shoreline Change Assessments at Global Scales. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 2316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christofi, D.; Mettas, C.; Evagorou, E.; Stylianou, N.; Eliades, M.; Theocharidis, C.; Chatzipavlis, A.; Hasiotis, T.; Hadjimitsis, D. A Review of Open Remote Sensing Data with GIS, AI, and UAV Support for Shoreline Detection and Coastal Erosion Monitoring. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 4771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiede, J.; Jordan, C.; Moghimi, A.; Schlurmann, T. Long-Term Shoreline Changes at Large Spatial Scales at the Baltic Sea: Remote-Sensing Based Assessment and Potential Drivers. Front. Mar. Sci. 2023, 10, 1207524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horritt, M.S.; Bates, P.D. Evaluation of 1D and 2D Numerical Models for Predicting River Flood Inundation. J. Hydrol. 2002, 268, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idris, N.H.; Deng, X.; Md Din, A.H.; Idris, N.H. CAWRES: A Waveform Retracking Fuzzy Expert System for Optimizing Coastal Sea Levels from Jason-1 and Jason-2 Satellite Altimetry Data. Remote Sens. 2017, 9, 603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stateczny, A.; Halicki, A.; Specht, M.; Specht, C.; Lewicka, O. Review of Shoreline Extraction Methods from Aerial Laser Scanning. Sensors 2023, 23, 5331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgson, M.E.; Bresnahan, P. Accuracy of Airborne Lidar-Derived Elevation: Empirical Assessment and Error Budget. Photogramm. Eng. Remote Sens. 2004, 70, 331–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, D.; Blaskow, R. Boat-Based Mobile Laser Scanning for Shoreline Monitoring of Large Lakes. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spatial Inf. Sci. 2021, 43, 759–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Stefano, F.; Chiappini, S.; Gorreja, A.; Balestra, M.; Pierdicca, R. Mobile 3D Scan LiDAR: A Literature Review. Geomatics Nat. Hazards Risk 2021, 12, 2387–2429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Pizzo, S.; Angrisano, A.; Gaglione, S.; Troisi, S. Assessment of Shoreline Detection Using UAV Photogrammetry. In Proceedings of the 2020 IMEKO TC-19 International Workshop on Metrology for the Sea (IMEKO 2020), Naples, Italy, 5–7 October 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Vaaja, M.; Kukko, A.; Kaartinen, H.; Kurkela, M.; Kasvi, E.; Flener, C.; Hyyppä, H.; Hyyppä, J.; Järvelä, J.; Alho, P. Data Processing and Quality Evaluation of a Boat-Based Mobile Laser Scanning System. Sensors 2013, 13, 12497–12515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markiewicz, Ł.; Mazurek, P.; Chybicki, A. Coastline Change-Detection Method Using Remote Sensing Satellite Observation Data. Hydroacoustics 2016, 19, 277–284. [Google Scholar]

- Pardo-Pascual, J.E.; Almonacid-Caballer, J.; Cabezas-Rabadán, C.; Fernández-Sarría, A.; Armaroli, C.; Ciavola, P.; Montes, J.; Souto-Ceccon, P.E.; Palomar-Vázquez, J. Assessment of Satellite-Derived Shorelines Automatically Extracted from Sentinel-2 Imagery Using SAET. Coast. Eng. 2024, 188, 104426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vos, K.; Splinter, K.D.; Palomar-Vázquez, J.; Pardo-Pascual, J.E.; Almonacid-Caballer, J.; Cabezas-Rabadán, C.; Kras, E.C.; Luijendijk, A.P.; Calkoen, F.; Almeida, L.P.; et al. Benchmarking Satellite-Derived Shoreline Mapping Algorithms. Commun. Earth Environ. 2023, 4, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Specht, O. Spatial Analysis of Bathymetric Data from UAV Photogrammetry and ALS LiDAR: Shallow-Water Depth Estimation and Shoreline Extraction. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Śledziowski, J.; Giza, A.; Terefenko, P. S-LiNE: An Open-Source LiDAR Toolbox for Dune Coasts Shoreline Mapping. SoftwareX 2025, 31, 102261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicens-Miquel, M.; Medrano, F.A.; Tissot, P.E.; Kamangir, H.; Starek, M.J.; Colburn, K. A Deep Learning Based Method to Delineate the Wet/Dry Shoreline and Compute Its Elevation Using High-Resolution UAS Imagery. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 5990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanutta, A.; Lambertini, A.; Vittuari, L. UAV Photogrammetry and Ground Surveys as a Mapping Tool for Quickly Monitoring Shoreline and Beach Changes. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2020, 8, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, D.C.; Davenport, I.J. Accurate and Efficient Determination of the Shoreline in ERS-1 SAR Images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 1996, 34, 1243–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-de la Peña, E.; Coco, G.; Whittaker, C.; Montaño, J. On the Use of Convolutional Deep Learning to Predict Shoreline Change. Earth Surf. Dynam. 2023, 11, 1145–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khurram, S.; Pour, A.B.; Bagheri, M.; Helmy Ariffin, E.; Akhir, M.F.; Bahri Hamzah, S. Developments in Deep Learning Algorithms for Coastline Extraction from Remote Sensing Imagery: A Systematic Review. Earth Sci. Inform. 2025, 18, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, A.S.; Mohamed, S.A.; Helmy, A.K.; Nasr, A.H. BDCN_UNet: Advanced Shoreline Extraction Techniques Integrating Deep Learning. Earth Sci. Inform. 2025, 18, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Z.; Nunez, K.; Brewer, E.; Runfola, D. pyShore: A Deep Learning Toolkit for Shoreline Structure Mapping with High-Resolution Orthographic Imagery and Convolutional Neural Networks. Comput. Geosci. 2023, 171, 105296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seale, C.; Redfern, T.; Chatfield, P.; Luo, C.; Dempsey, K. Coastline Detection in Satellite Imagery: A Deep Learning Approach on New Benchmark Data. Remote Sens. Environ. 2022, 278, 113044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donchyts, G.; Baart, F.; Winsemius, H.; Gorelick, N.; Kwadijk, J.; Van de Giesen, N. Earth’s Surface Water Change over the Past 30 Years. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2016, 6, 810–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstantinou, A.; Scott, T.; Masselink, G.; Stokes, K.; Conley, D.; Castelle, B. Satellite-Based Shoreline Detection along High-Energy Macrotidal Coasts and Influence of Beach State. Mar. Geol. 2023, 462, 107082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halicki, A.; Specht, M.; Stateczny, A.; Specht, C.; Specht, O. Shoreline Extraction Based on LiDAR Data Obtained Using an USV. TransNav Int. J. Mar. Navig. Saf. Sea Transp. 2023, 17, 445–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardemann, H.; Blaskow, R.; Maas, H.-G. Camera-Aided Orientation of Mobile Lidar Point Clouds Acquired from an Uncrewed Water Vehicle. Sensors 2023, 23, 6009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glennie, C. Rigorous 3D Error Analysis of Kinematic Scanning LIDAR Systems. J. Appl. Geod. 2008, 1, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukko, A.; Kaartinen, H.; Hyyppä, J.; Chen, Y. Multiplatform Mobile Laser Scanning: Usability and Performance. Sensors 2012, 12, 11712–11733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Ye, N.; Xu, S. A New Method for Shoreline Extraction from Airborne LiDAR Point Clouds. Remote Sens. Lett. 2019, 10, 496–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stateczny, A.; Burdziakowski, P. Universal Autonomous Control and Management System for Multipurpose Unmanned Surface Vessel. Pol. Marit. Res. 2019, 26, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaszcz, A.; Włodarczyk-Sielicka, M.; Stateczny, A.; Połap, D.; Garczyńska, I. Automated Shoreline Segmentation in Satellite Imagery Using USV Measurements. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 4457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Specht, M.; Stateczny, A.; Specht, C.; Widźgowski, S.; Lewicka, O.; Wiśniewska, M. Concept of an Innovative Autonomous Unmanned System for Bathymetric Monitoring of Shallow Waterbodies (INNOBAT System). Energies 2021, 14, 5370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alesheikh, A.A.; Ghorbanali, A.; Nouri, N. Coastline Change Detection Using Remote Sensing. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2007, 4, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Wang, J.; Zheng, F.; Wang, H.; Yang, H. An Overview of Coastline Extraction from Remote Sensing Data. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 4865. [Google Scholar]

- Rusu, R.B. Semantic 3D Object Maps for Everyday Manipulation in Human Living Environments. Ph.D. Thesis, Technische Universität München, München, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- S-44 Edition 6.1.0; IHO Standards for Hydrographic Surveys. International Hydrographic Organization: Monaco, Monaco, 2022.

| Criterion | MLS | UAV Orthophoto |

|---|---|---|

| Shoreline accuracy (95%) | 1.16 m | 0.05 m (natural shoreline); 0.06 m (including piers) |

| Data characteristics | 3D point cloud with variable density | Raster image with very high spatial resolution |

| Object identification | Detailed representation of the coastal zone; limited representation of slender structural elements (e.g., piers) | Clear identification of the land–water boundary and hydrotechnical infrastructure |

| Limitations | Irregular point density, water reflections, lower spatial accuracy | Affected by shadows and reflections on the water surface |

| Advantages | Independence from lighting conditions; ability to capture data in vegetated areas; full 3D information on the coastal zone | Very high accuracy (sub-decimetre); clear visual interpretation |

| Applications | Shoreline determination in hard-to-access areas; supplementing imagery | Accurate shoreline determination and identification of hydrotechnical structures |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Specht, M.; Specht, O. Accuracy Assessment of Shoreline Extraction Using MLS Data from a USV and UAV Orthophoto on a Complex Inland Lake. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3940. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243940

Specht M, Specht O. Accuracy Assessment of Shoreline Extraction Using MLS Data from a USV and UAV Orthophoto on a Complex Inland Lake. Remote Sensing. 2025; 17(24):3940. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243940

Chicago/Turabian StyleSpecht, Mariusz, and Oktawia Specht. 2025. "Accuracy Assessment of Shoreline Extraction Using MLS Data from a USV and UAV Orthophoto on a Complex Inland Lake" Remote Sensing 17, no. 24: 3940. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243940

APA StyleSpecht, M., & Specht, O. (2025). Accuracy Assessment of Shoreline Extraction Using MLS Data from a USV and UAV Orthophoto on a Complex Inland Lake. Remote Sensing, 17(24), 3940. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243940