1. Introduction

Soybean, as a globally important crop with combined roles in food, economic, and oil production systems, plays a fundamental and strategic role in safeguarding national food security, supporting oil and feed supply chains, and stabilizing agro-industrial systems [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Although China is the world’s largest soybean consumer and the fourth largest producer, its long-term self-sufficiency remains low, and heavy dependence on imports persists [

5]. In the face of international trade fluctuations and growing geopolitical uncertainties, establishing a multi-scale, spatiotemporal monitoring and assessment system has become imperative. Such a system must deliver continuous, fine-grained, and comparable mapping of soybean cultivation patterns to support decision-making in grain and oil security, optimize production layouts, and enable the early warning of agricultural risks [

6].

Remote sensing, with its wide spatial coverage and high revisit frequency, has become a major technical pathway for crop information extraction and mapping [

7,

8,

9]. However, optical imagery alone suffers from cloud contamination and shadow effects, compromising the temporal completeness and class separability of key phenological stages. Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR), in contrast, provides all-weather and all-day observations that capture backscattering variations related to surface roughness and dielectric properties, thereby complementing optical features and enhancing the robustness of crop discrimination [

10,

11]. Multi-source, multi-temporal fusion has repeatedly been shown to improve mapping accuracy and stability [

11,

12,

13]. For example, Kuang et al. [

14] achieved high-accuracy crop-area identification using a convolutional neural network (CSCNN) and multi-sensor satellite imagery, while Yu et al. [

12] combined Landsat, Sentinel-2, and MODIS data to realize near-real-time, multi-resolution land-cover mapping. In scenarios where large numbers of candidate features accumulate rapidly, filter-based feature selection becomes critical for alleviating the curse of dimensionality. Separability-driven metrics can effectively construct compact and physically interpretable feature subsets [

15,

16]. Among these, the Jeffries–Matusita (JM) distance exhibits high stability and robustness in assessing crop discriminability [

17]. Das et al. [

18] applied JM-based selection combined with field spectroradiometry for precise rice identification, and Yan et al. [

19] selected maize phenological features from Sentinel-1/2 imagery using JM distance and achieved accurate mapping with TWDTW, Random Forest (RF), and LSTM models.

In the deep learning domain, crop mapping has evolved from single-modality convolutional models toward a new paradigm of multi-modal, multi-temporal, and lightweight joint modeling [

20,

21,

22]. Classical CNN/FCN architectures, with their encoder–decoder design and skip connections, effectively preserve parcel-scale textures and boundaries. However, their limited receptive fields and local inductive bias constrain their ability to model long-range dependencies and cross-parcel semantic consistency [

23,

24]. Transformer architectures enhance long-distance interactions via global self-attention and perform well in large-area scene understanding, but their quadratic complexity increases sharply with spatial resolution and temporal depth, leading to high memory and latency costs and reduced stability in noisy agricultural environments with limited training data [

25]. Recently, Selective State-Space Models (SSM) and the Mamba framework have emerged as efficient alternatives, achieving long-sequence modeling with linear-time updates. These models exhibit superior trade-offs between performance and computational efficiency on wide-swath, long-temporal remote-sensing imagery, making them ideal for mid- and deep-level temporal–global representation learning [

26]. Consequently, hybrid architectures have become a new trend in crop-mapping research. Typically, the shallow layers employ depthwise separable convolutions (to reduce computation) and windowed self-attention (to enhance local texture and boundary awareness); the middle and deep layers integrate SSM/Mamba modules to capture long-range spatial dependencies (e.g., contiguous cropland patterns) and cross-temporal consistency (e.g., phenological evolution across stages). Multi-scale decoding and skip fusion further achieve semantic alignment, striking a robust balance between accuracy and efficiency [

27,

28,

29]. Zhu et al. [

30] proposed an improved Mamba-based U-Net that reduced parameters by 40% and computation by 35% while enhancing global context modeling and improving parcel-integrity accuracy by 8%. Wu et al. [

31] developed the MV-YOLO framework centered on Mamba, demonstrating improved small-object detection and edge fidelity under complex field conditions. Multi-source fusion studies further validate this paradigm: Jamali et al. [

32] achieved wetland classification by integrating Sentinel-1/2 and LiDAR using VGG-16; Chroni et al. [

33] fused multispectral and airborne LiDAR data within a U-Net for land-cover segmentation; Dedring et al. [

34] applied CGAN to enhance Sentinel-2 land-use/land-cover (LULC) classification; and Chen et al. [

35] verified the superiority of UNet++ for urban vegetation discrimination. Overall, the combination of multi-modal inputs and integrated local–global–temporal design, together with separability-driven feature–phase selection, provides a robust solution for soybean mapping in regions with frequent cloud cover, pronounced speckle effects, and fragmented landscapes.

Motivated by the above analysis, this study focused on three interrelated challenges in applying a hybrid multi-source and feature-selection-enhanced deep learning framework to high-resolution soybean mapping: (1) constructing cloud-robust and phenology-sensitive multi-temporal Sentinel-1/2 stacks in regions with frequent cloud cover and strong speckle noise; (2) deriving compact yet discriminative optical–SAR feature subsets from high-dimensional and redundant predictors while preserving phenological separability; and (3) designing a lightweight segmentation architecture that can simultaneously maintain small-field boundary fidelity and long-range contextual consistency under constrained computational resources. To address these challenges, this study focused on Biyang County, a representative soybean-producing region in the Huang-Huai-Hai Plain, China. Using multi-temporal Sentinel-1/2 imagery from four key phenological stages in 2023, we established a high-resolution mapping framework. At the data level, a standardized preprocessing and temporal-compositing workflow was implemented in Google Earth Engine (GEE) to integrate optical and SAR imagery. At the feature level, candidate sets encompassing raw spectral bands, vegetation indices, textures, and polarimetric metrics were subjected to JM-based feature–phase joint selection, producing compact, phenologically interpretable subsets with reduced redundancy. At the model level, we designed a lightweight APM-UNet architecture that integrated local–global coordination: an Attention Sandglass Layer (ASL) in the shallow encoder enhances fine-scale textures and boundaries, while Parallel Vision Mamba Layers (PVML) in the mid/deep stages and bottleneck capture long-range dependencies and global context with near-linear complexity. This design significantly improves boundary fidelity and semantic consistency under limited parameter and computational budgets.

3. Research Methods

As illustrated in

Figure 1, the workflow comprises two tightly coupled stages. (1) Data & feature pipeline. Guided by crop phenology, multi-temporal Sentinel-1/2 imagery is retrieved from GEE and subjected to orbit, radiometric, and topographic corrections, Refined-Lee speckle filtering, cloud/shadow masking, and sub-pixel co-registration to an S2 reference, yielding a temporally aligned fusion stack on a uniform 10 m grid. From this stack, we derive a candidate feature set spanning raw spectral bands, vegetation indices, textures, and polarimetric terms. We then perform Jeffries–Matusita (JM) distance-based feature–phase joint selection: for each phenological stage and each candidate feature, the JM distance is computed between soybean and all non-soybean land-cover classes, the feature-level JM value at that stage is taken as the maximum of these pairwise distances, features with a maximum JM ≥ 1.8 are retained, and the final multi-temporal subset (feature set D4) is obtained as the union of all retained feature–stage combinations (see

Section 3.1 for details). Based on the selected features, stratified random sampling with spatial balancing was used to construct class-balanced, spatially disjoint training/validation sets. (2) Model stage. We built a lightweight semantic-segmentation network, APM-UNet, that integrates state-space modeling. In the U-shaped backbone, the Attention Sandglass Layer (ASL) is inserted in the shallow encoder to enhance fine-grained texture and boundary representation via a DW-Conv → PW down/expand + windowed attention pathway. The mid/deep encoder employs Parallel Vision Mamba Layers (PVML): features are Layer-Normalized, channel-partitioned, and processed in parallel Mamba/SSM branches with residual scaling and linear projection, enabling near-linear-complexity global-context modeling without increasing the overall channel budget. At the bottleneck, 2-D feature maps are serialized and updated by SSM to strengthen long-range dependencies. The decoder uses cascaded up-sampling and skip connections to achieve multi-scale semantic alignment and detail recovery, delivering high boundary fidelity and cross-parcel consistency under constrained parameters and memory. Prepending JM-driven feature selection and coupling it with the local–global coordination of APM-UNet jointly improve the discriminability and spatial consistency of soybean mapping while keeping computational and memory costs in check.

3.1. Feature Selection

A comprehensive feature library was constructed using Sentinel-1/2 imagery acquired at four key phenological stages of soybean growth. The library integrates four major feature categories: (1) raw spectral bands, (2) vegetation indices, (3) texture features, and (4) polarimetric parameters. In total, 136 features were compiled, including 48 spectral bands, 48 vegetation indices, 32 texture metrics obtained by first performing PCA on all original bands at each phenological stage to retain the first principal component (PC1) as a fused gray-level image and then computing gray-level co-occurrence matrix (GLCM) statistics from these PC1 images, and 8 polarimetric features. Given the large number of features and the need for reproducibility and interpretability, all features were systematically renamed and indexed following a unified coding scheme. The detailed naming convention and corresponding feature definitions are summarized in

Table 3.

In deep learning-based remote sensing tasks, appropriate feature selection plays a crucial role in improving model accuracy, suppressing overfitting, and reducing computational and storage costs [

41,

42]. In this study, the Jeffries–Matusita (JM) distance was employed to quantitatively evaluate the class separability of multi-temporal and multi-modal candidate features. Features were ranked according to their discriminative capability, and those with high separability and low redundancy were retained to form a compact, physically interpretable subset for model training and inference. This approach significantly enhances the classification and segmentation accuracy, accelerates convergence, and stabilizes the training process without increasing model parameters or computational overhead [

19]. Considering the pronounced spatial heterogeneity and intra-class variability typically observed in soybean mapping, the JM-based feature selection strategy effectively identifies a subset of features that maintain strong class separability while achieving dimensionality reduction and information compression. The resulting optimal feature set is subsequently used for model training and prediction, yielding notable improvements in both accuracy and convergence stability under limited parameter budgets. The JM distance, originally proposed by Harold Jeffries and David Matusita [

15,

43], quantifies the statistical separability between two classes in the feature space. It is defined as:

where

JM represents the Bhattacharyya distance, and

JM denotes the Jeffries–Matusita (JM) distance between classes

i and

j.

mi and

mj are the mean feature vectors of classes

i and

j, respectively, while

δi and

δj are their corresponding standard deviations. The value of

JM ranges from 0 to 2, where a higher value indicates a greater degree of separability between the two classes [

29]. Following common practice in separability-driven band and feature selection,

JM values above approximately 1.8–2.0 are generally regarded as indicating good to excellent class separability [

15,

19,

29]. In this study, we therefore adopted

JM < 1.8 as an empirical criterion for insufficient separability: features with

JM ≥ 1.8 were retained as strongly separable candidates.

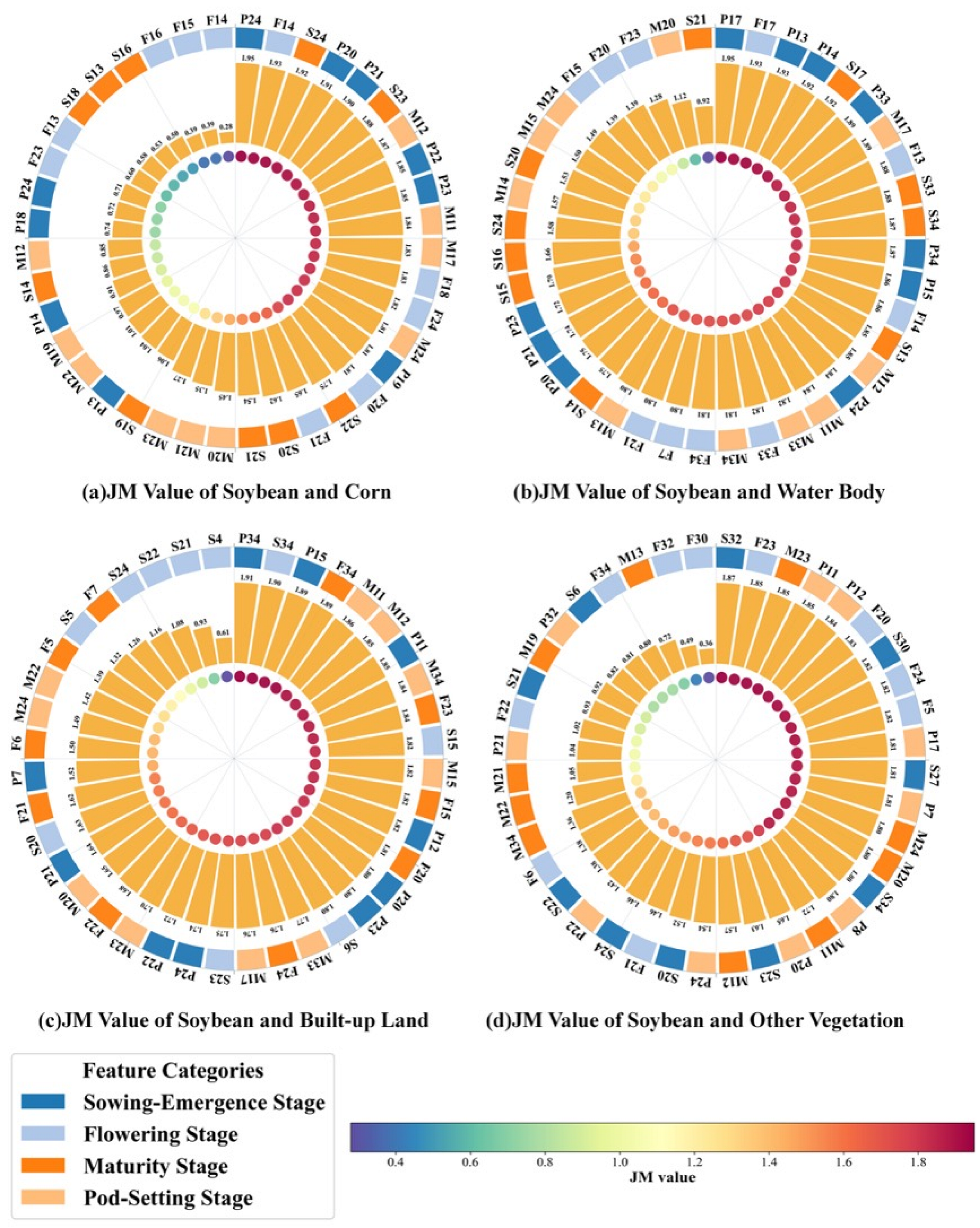

In the multi-class setting of this study, soybean was treated as the target class, and the JM distance was computed between soybean and each non-soybean land-cover class (corn, water body, built-up land, and other vegetation). For a given candidate feature at a specific phenological stage, this yielded four pairwise JM distances. Consistent with our selection strategy, the feature-level JM value was defined as the maximum of these four distances, so that a feature is retained if it exhibits strong separability for at least one soybean vs. non-soybean class pair. Features with a maximum JM value ≥ 1.8 were kept, and all others were discarded. This JM-based filtering yielded a compact, phenology-aware feature subset (feature set D4) that was subsequently used for model training and evaluation.

3.2. APM-UNet Hybrid Network

To address the limitations of conventional U-Net in modeling long-range spatial dependencies and mitigating boundary ambiguities and cross-parcel confusion in large-scale agricultural scenes, this study proposes an Attention–Parallel-Mamba U-Net (APM-UNet) hybrid architecture [

44,

45]. Built upon the classical encoder–decoder backbone, the model introduces a complementary local–global representation mechanism: shallow layers emphasize fine-grained texture and edge features, while deeper layers capture global contextual consistency across parcels and landscapes. Empirically, we observed that most errors in baseline U-Net predictions arise from (1) blurred or fragmented soybean parcel boundaries and (2) inconsistent predictions within the same field under heterogeneous backscatter and reflectance. Consequently, ASL is deployed in shallow stages to reinforce fine-scale edges and textures, whereas PVML is placed in deeper stages to propagate long-range information and improve parcel-level semantic consistency under a limited computational budget. At the bottleneck, a Selective State Space Model (SSM) is incorporated to efficiently model long-range dependencies with near-linear complexity.

As illustrated in

Figure 1b, the encoder comprises seven stages. The first to third stages embed Attention Sandglass Layers (ASL) to enhance the representation of field textures, crop boundaries, and fragmented objects. The fourth to sixth stages employ Parallel Vision Mamba Layers (PVML) to strengthen global semantic coherence across heterogeneous farmland units while maintaining parameter efficiency. At the bottleneck, the Mamba-SSM captures extended spatial dependencies and fuses multi-scale contextual information in a robust manner. The decoder mirrors this design with six symmetric stages following the same ASL-in-shallow and PVML-in-deep configuration. Through hierarchical skip connections, shallow-level details are integrated with deep semantic features, progressively restoring spatial resolution and producing the final segmentation output.

3.2.1. Attention Sandglass Layer (ASL)

We introduced a lightweight Attention Sandglass Layer (ASL) to jointly enhance local texture/boundary fidelity and cross-neighborhood interaction under a controlled computational budget [

46]. In high-resolution Sentinel-1/2 scenes, most misclassifications concentrate along field boundaries and narrow transition zones, where crop rows, ridges, and mixed vegetation generate complex local textures. Purely convolutional encoders tend to blur these details after repeated down-sampling, whereas global self-attention is computationally prohibitive at shallow, high-resolution stages. The proposed ASL is therefore designed as a boundary- and texture-aware shallow block that reinforces fine-scale edge and row patterns while selectively injecting limited-range context under a controllable complexity. ASL fuses efficient local modeling via depthwise-separable convolutions with long-range dependency modeling via window-based multi-head self-attention (EW-MHSA).

Let

be the input. ASL consists of (i) a sandglass backbone that performs channel compression→expansion and (ii) a parallel EW-MHSA branch. Concretely,

X is processed by a DW-Conv to capture fine-grained spatial patterns, followed by two PW-Convs for dimensionality reduction and restoration; a second DW-Conv further refines local structures. A residual shortcut from the input to the backbone mitigates information loss and gradient attenuation introduced by compression. In parallel, EW-MHSA establishes interactions within each local window and its extended neighborhood, improving cross-strip and cross-parcel semantic coherence. The operator is:

where

and

are two depthwise convolutions,

and

are the expansion/reduction PW-Convs, and

denotes the EW-MHSA branch. LayerNorm/BN and light projection layers can be inserted between branches to stabilize training. Default configuration: DW-Conv kernel

, stride = 1; PW-Conv reduction ratio

; EW-MHSA window size

with shifted windows; activation SiLU or ReLU; Pre-Norm normalization. Compared with global attention, ASL exhibits a more controllable complexity growth, making it well-suited for shallow/mid encoder stages and symmetric placement in the decoder, thereby balancing detail preservation and contextual modeling in high-resolution agricultural scenes. In practice, ASL produces high responses along soybean parcel boundaries and row structures while suppressing noise in homogeneous background regions. As illustrated in

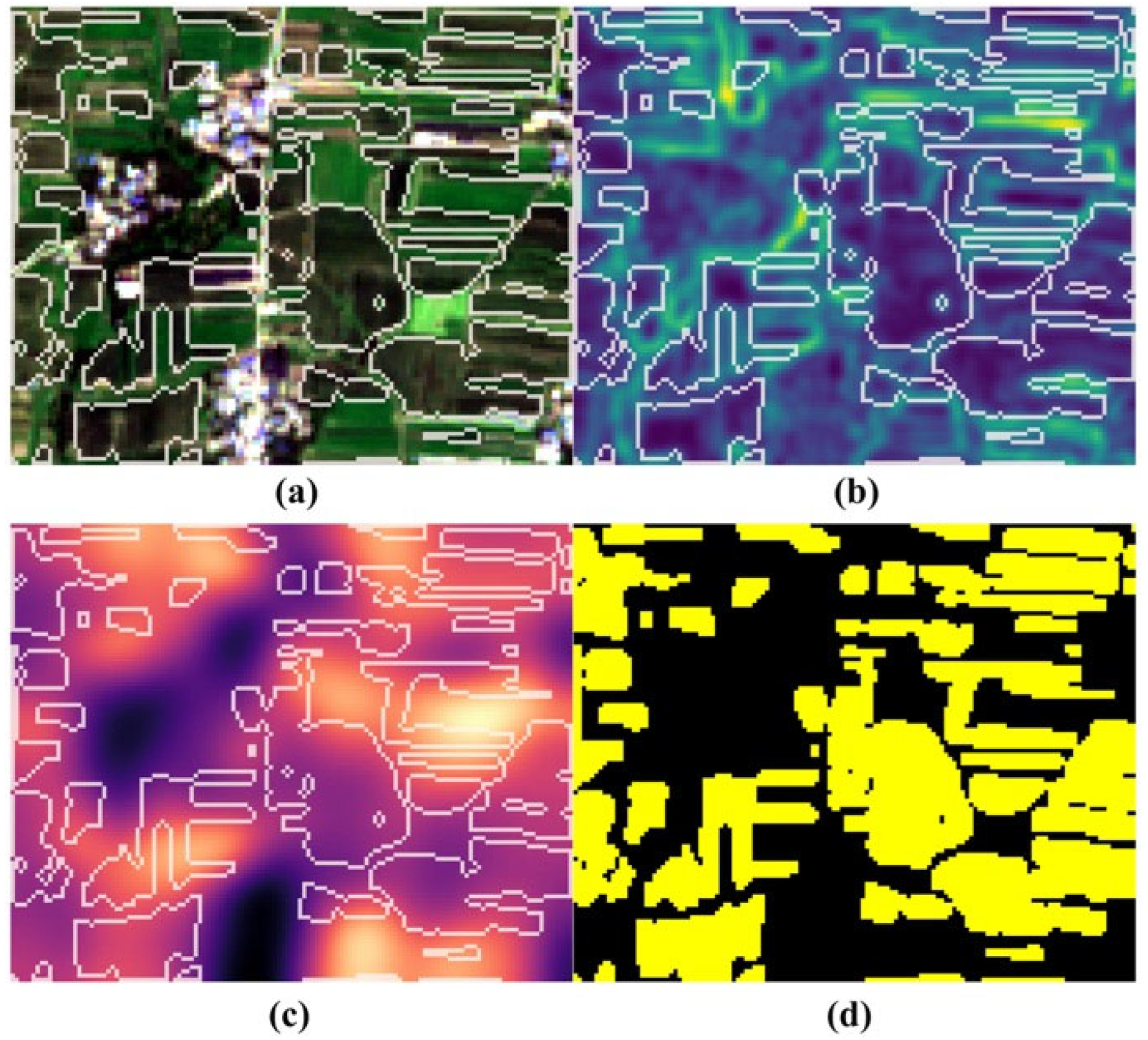

Figure 2b, the ASL-enhanced shallow feature map exhibited intensified activations aligned with the red parcel boundaries and crop-row directions, intuitively confirming its role as a boundary- and texture-enhancement module in the shallow encoder–decoder stages.

3.2.2. Parallel Vision Mamba Layer (PVML)

To effectively capture long-range dependencies and ensure semantic consistency across agricultural parcels, we introduced the Parallel Vision Mamba Layer (PVML) for global spatial representation learning [

47]. Given that the Mamba architecture is highly sensitive to the channel dimension, an increase in the number of channels substantially enlarges both the state dimension and the projection matrices, leading to rapid growth in parameter count and memory consumption [

26,

48].

To address this, PVML adopts a lightweight design based on channel-wise parallelization, residual scaling, and projection fusion. Specifically, the input feature

is first normalized using LayerNorm, then equally divided into four channel groups (each of size

). These sub-features are independently processed by parallel Mamba-SSM branches, which model long-range dependencies in linear time complexity. The choice of four groups provides a practical balance between per-branch width and parallel diversity: each branch retains sufficient channel capacity to learn expressive dynamics, while the total number of branches remains small enough to keep the overall parameter count and memory footprint close to that of the baseline backbone. The outputs of each branch are subsequently residually scaled and fused through additive or concatenation operations, followed by a linear projection to restore the full C channel dimension and align with the main network (

Figure 1b). This design substantially strengthens global contextual perception and cross-parcel semantic coherence while maintaining nearly constant channel and memory budgets. The overall computation can be formulated as follows:

where

LN denotes Layer Normalization,

SP is the Split operation, Mamba is the Mamba operator,

is the residual scaling factor,

is the concatenation, and

Pro is the linear projection. By processing features through PVML in this manner, the total number of channels remains unchanged, enabling high-precision global representation learning while minimizing parameter overhead and maintaining computational efficiency. Consequently, PVML tends to produce smooth and homogeneous activations within soybean parcels while maintaining sharp transitions at parcel boundaries. As shown in

Figure 2c, the PVML-based deep feature map was almost uniform inside the yellow soybean fields and clearly suppressed in surrounding non-soybean areas, providing an intuitive demonstration that PVML improves parcel-level semantic coherence and reduces within-field fragmentation in a way that complements the boundary-focused behavior of ASL. The intermediate feature visualizations in

Figure 2b, c therefore offer an intuitive complement to the mathematical formulations of ASL and PVML.

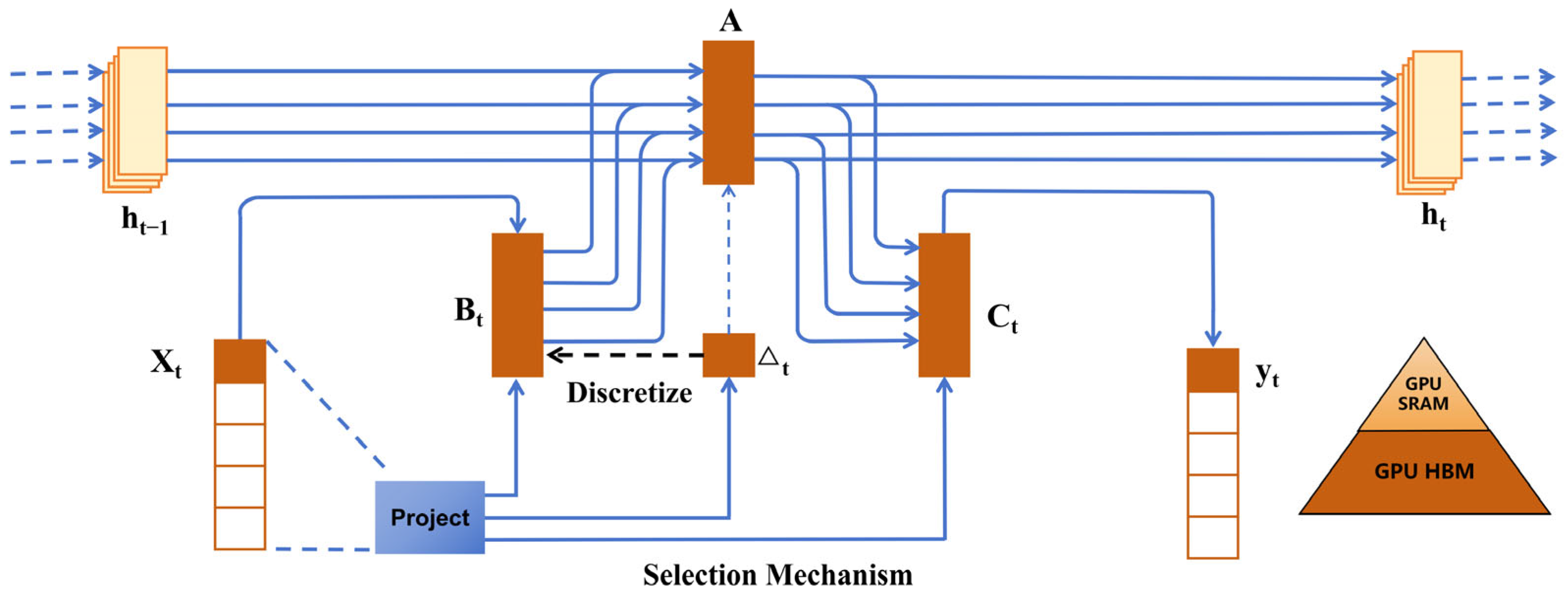

3.2.3. Selective State Space Model (SSM)

The Mamba module, serving as the core component of APM-UNet, is built upon a Selective State Space Model (SSM) [

49]. The SSM follows a fundamental paradigm of state evolution and observation mapping, which efficiently captures long-range dependencies with linear-time complexity. It can be viewed as a unified and extended framework that bridges the temporal modeling capability of recurrent neural networks (RNNs) and the local representation power of convolutional neural networks (CNNs) [

50,

51]. The continuous-time form of the SSM is expressed as follows:

where Equation (8) represents the state transition, and Equation (9) defines the observation mapping. These two equations jointly constitute the mathematical foundation of the SSM, which aims to infer the latent state variable

from a given input

and a set of system parameters, thereby establishing a dynamic and interpretable input–output mapping. Here,

is the state-transition matrix governing interactions among internal states,

is the input matrix defining how the external signal

drives state evolution,

is the output (observation) matrix mapping latent states to the observable outputs, and

is the direct feed-through term describing direct input–output coupling (commonly set to

). A schematic representation of the SSM operational mechanism is illustrated in

Figure 3.

In the implementation of the Mamba-SSM module, the two-dimensional feature maps are first serialized following a predefined scanning strategy (e.g., row-wise, column-wise, or selective multi-directional scanning). These serialized sequences are then fed into the Mamba-SSM, which models long-range dependencies and captures global contextual information with linear time complexity. The resulting representations are subsequently aligned and fused with outputs from the local convolutional and window-based attention branches through a gated residual fusion mechanism, achieving an optimal balance between boundary fidelity and cross-parcel semantic consistency. This design significantly improves the accuracy, robustness, and generalization performance of soybean mapping in high-resolution remote sensing imagery, while maintaining nearly constant parameter count and memory consumption.

3.3. Accuracy Evaluation Methods

To comprehensively assess the performance of the proposed network in remote sensing imagery classification and segmentation tasks, six quantitative metrics were employed: Producer’s Accuracy (

PA), Overall Accuracy (

OA), Kappa coefficient (

Kappa),

Recall, Intersection over Union (

IoU), and the F1-score (

F1). Unless otherwise specified, all metrics were computed at the pixel level, and the final scores are reported as macro-averages across all classes to ensure class-balanced evaluation. The corresponding mathematical formulations are as follows:

where

TP (True Positives) denotes the number of pixels correctly classified as the target class,

FP (False Positives) refers to the number of non-target pixels incorrectly predicted as the target class, and

FN (False Negatives) represents the number of target pixels that were not correctly identified by the model. Additionally, the Producer’s Accuracy Weighted Average (

PE) is calculated by applying predefined class weights to individual PA values to account for category imbalance and to better reflect the model’s class-specific reliability.

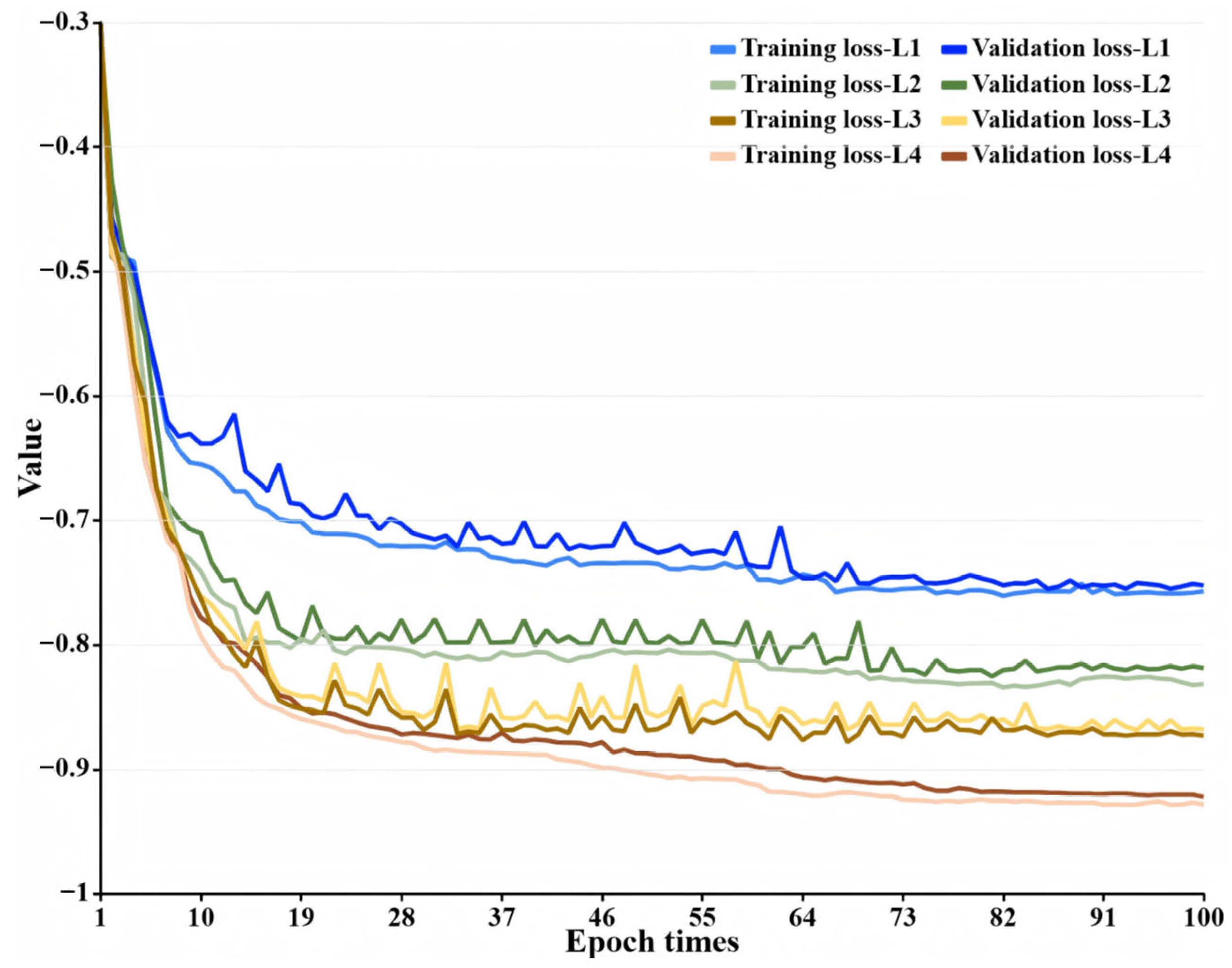

3.4. Experimental Setup and Training Strategy

All experiments were conducted on an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4090 GPU under Ubuntu 20.04, with CUDA 11.3 and cuDNN 8.2.1 configured for GPU acceleration. The deep learning framework used was PyTorch v1.8.1. To ensure reproducibility, random seeds were fixed and deterministic operations were enabled. The input comprised multi-temporal Sentinel-1/2 fused data, with each spectral and polarization channel normalized using z-score standardization. The imagery was partitioned into 512 × 512 training patches (stride = 256 px) to enhance spatial coverage and boundary utilization, with stratified sampling adopted to balance class distribution and spatial heterogeneity. Data augmentation included random rotation and flipping, scale perturbation, random cropping, and mild spectral and speckle noise injection. On the output side, label smoothing (

) was applied to mitigate overfitting and improve generalization. The network was trained end-to-end with a mini-batch size of 16 patches using a compound loss that combined class-balanced cross-entropy and Dice loss with equal weighting. Specifically, the total loss is defined as:

So that lower (and possibly negative) values of L correspond to better agreement between predictions and reference labels. Model optimization was performed using stochastic gradient descent (SGD) with a momentum of 0.9 and the following key hyperparameters: an initial learning rate of 0.0006, weight decay of 0.00025, and 2000 training epochs. To prevent overfitting and accelerate convergence, an early stopping mechanism was adopted: training was terminated if the validation loss failed to decrease for 100 consecutive epochs. Additionally, a learning-rate decay schedule was applied—when the validation loss plateaued for three consecutive epochs, the learning rate was halved. Experimental results demonstrate that the proposed approach achieved high convergence efficiency and training stability in soybean mapping tasks based on multi-temporal remote sensing imagery.

5. Discussion

5.1. Comparative Analysis of Feature Selection Methods

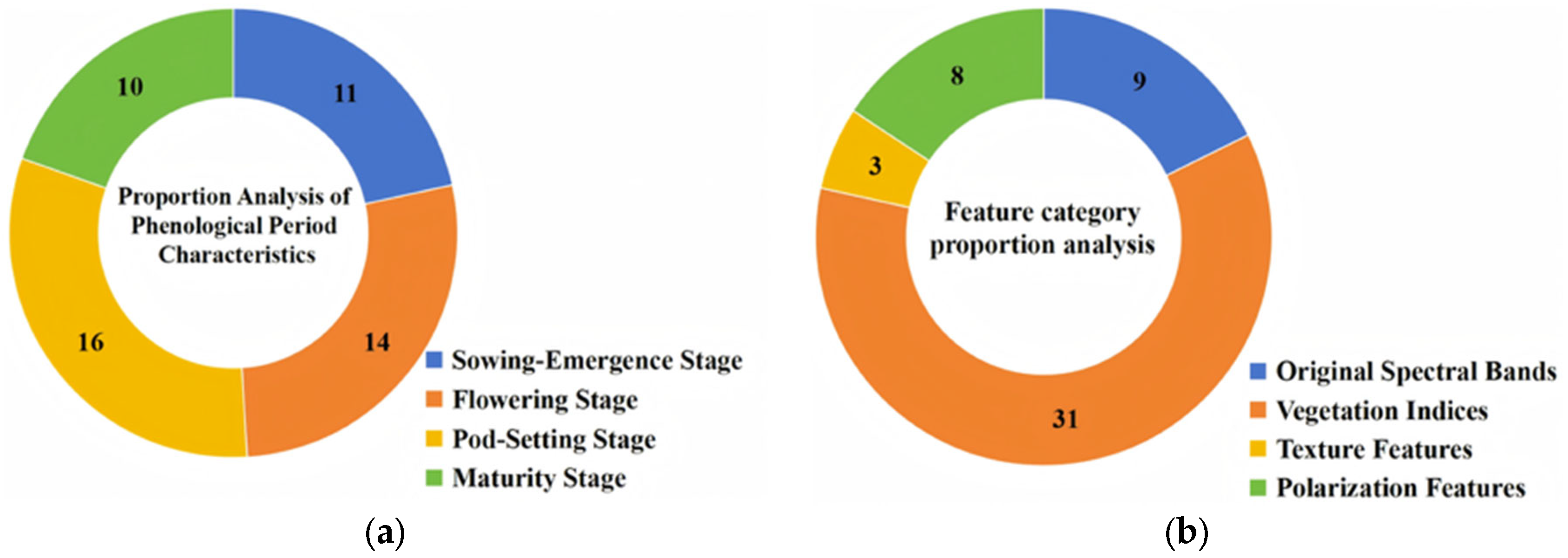

Under unified data preprocessing and training protocols, four types of feature sets were constructed and systematically compared across four representative architectures—U-Net, SegFormer, Vision-Mamba, and APM-UNet—to evaluate the influence of feature construction on classification performance. Feature selection employed a Jeffries–Matusita (JM) distance-based filtering strategy, which simultaneously assessed global separability and inter-channel correlation while incorporating class-specific local separability to prevent the masking of key inter-class differences by global averaging. With a threshold of JM > 1.8, a total of 51 optimal features were retained, and their temporal (month-wise) and categorical distributions were analyzed to trace the sources of discriminative power. The Pod-Setting Stage contributed the largest number of selected features, vegetation indices dominated in feature type, and all Sentinel-1 VV/VH polarization features were retained, underscoring the complementarity between optical and radar modalities. To quantify the marginal contribution of temporal information, a single-phase control group (Pod-Setting Stage only) was designed and compared against multi-temporal feature sets under identical network conditions.

Quantitative evaluations demonstrated that JM-based optimization consistently produced stable and significant improvements across all networks, outperforming both “full-feature” and “single-phase/single-source” schemes. For example, in U-Net, JM optimization (U4) increased OA from 85.53% to 90.16%, IoU from 0.6413 to 0.6704, and F1 from 0.8306 to 0.8451, indicating that enhanced feature separability can systematically improve both pixel-level and boundary-level precision without increasing model complexity. Similar patterns were observed across architectures: JM-optimized configurations (S4, V4, AU4) achieved superior PA, OA, Kappa, IoU, and F1 scores compared to their respective baselines, with AU4 achieving the best overall performance (PA 92.81%, OA 97.95%, Kappa 0.9649, Recall 91.42%, IoU 0.7986, F1 0.9324). Furthermore, multi-temporal features consistently outperformed single-phase inputs, confirming that phenological diversity effectively amplifies inter-class separability.

Mechanistically, the JM-driven filtering criterion, combined with thresholding and correlation constraints, produced a compact yet complementary feature subset that simultaneously emphasized phenological variations and electromagnetic scattering differences among crop types in a multi-source, multi-temporal representation space. This synergy led to concurrent gains in boundary-sensitive metrics (IoU, F1) and overall consistency metrics (OA, Kappa). Contribution analysis revealed that red-edge and water-sensitive vegetation indices enhanced the spectral representation of canopy physiological–structural differences, thereby improving the classification of fragmented parcels and forest–farmland transition zones; meanwhile, Sentinel-1 VV/VH polarization features, complementary to optical spectra, maintained robust discrimination under cloud shadow and speckle interference, enhancing cross-parcel semantic consistency.

In summary, the integration of multi-source (Sentinel-1/2) and multi-temporal data with JM-distance-based feature filtering achieves fine-grained boundary delineation and global spatial consistency without adding computational complexity. This strategy complements the ASL (local feature enhancement) and PVML/SSM (global semantic modeling) modules of APM-UNet, jointly supporting the model’s superior balance among accuracy, boundary fidelity, and spatial consistency. Consequently, the JM-optimized composite feature set is established as the recommended configuration for subsequent experiments and practical applications in multi-temporal remote sensing crop classification.

5.2. Multi-Source Data Analysis

Under ensured experimental comparability, this section evaluates the marginal contributions of data sources (Sentinel-1/2) and temporal information (multi-temporal vs. single-temporal) to classification performance, with mechanistic interpretations supported by

JM-distance-based feature selection results. (1) Multi-source fusion outperformed single-source configurations. The complementary imaging mechanisms of optical and SAR data effectively mitigate interference from shadows, thin clouds, and complex background textures, yielding a systematic improvement in

OA and

Kappa, while substantially enhancing spatial consistency and patch integrity within fragmented parcels and forest–farmland transition zones (see

Figure 6). This advantage is consistently observed across all architectures (U-Net, SegFormer, Vision-Mamba, and APM-UNet), indicating that the benefits of multi-source fusion are architecture-independent. (2) Multi-temporal data outperformed single-phase inputs, with improvements reflected simultaneously in boundary-sensitive metrics (

IoU,

F1) and overall consistency metrics (

OA,

Kappa). Phenological variations amplify class separability along the temporal dimension, particularly in narrow plots, mosaic landscapes, and high-texture regions. Consistent with this finding, JM-based phenological contributions show that the Pod-Setting and Flowering stages exhibited the highest weights (approximately 32.69% and 26.92%, respectively), aligning with regional agricultural practices and phenological rhythms: early spring wilting/regreening and early summer cultivation/growth transitions enhance spectral and scattering contrast between target and non-target classes, thereby improving temporal discriminability.

From the perspective of feature-type contributions, the JM-optimized subset demonstrated a structural preference for spectral/physiological and radar-scattering features while de-emphasizing texture-based descriptors. Vegetation indices dominated (approximately 75%), with red-edge and water-sensitive indices effectively magnifying cross-phenological canopy physiological–structural differences. Following these were Sentinel-1 VV/VH polarization parameters and original optical bands: the former complements optical information through dielectric constant and surface roughness dimensions, effectively mitigating “voids” and cross-parcel adhesion within large-field and strip-shaped landscapes; the latter provides a stable spectral baseline for class discrimination. Texture features, in contrast, were minimally selected due to strong correlations with multi-temporal indices and because JM metrics at the pixel level preferentially retain spectral/polarimetric dimensions that directly enlarge inter-class separability. Overall, JM-distance-based feature optimization, guided by the principle of maximizing inter-class distance while minimizing intra-class variance, preserves compact, low-redundancy, and information-rich variables that emphasize physiological and scattering characteristics. This enables concurrent improvements in boundary-sensitive metrics (IoU, F1) and overall consistency metrics (OA, Kappa) without substantially increasing model complexity.

In summary, the integration of multi-source (Sentinel-1/2) and multi-temporal data with JM-distance-based optimization establishes a data–feature synergy: the former provides modal complementarity and phenological amplification, while the latter suppresses redundancy and correlation interference. Their combined effect enables all architectures—especially APM-UNet—to achieve concurrent gains in quantitative metrics (PA, OA, Kappa, Recall, IoU, F1) and qualitative performance (boundary continuity, patch integrity, and cross-parcel consistency), thus providing a robust foundation for regional scalability and long-term temporal monitoring in agricultural remote sensing applications.

5.3. Comparative Analysis of Classification Methods

The superior performance of APM-UNet under multi-temporal Sentinel-1/2 fusion can be attributed to the synergy between its local–global collaborative modeling and feature–phenology joint optimization strategies. The shallow Attention Sandglass Layer (ASL) enhances edge discrimination and fine-grained texture perception, while the mid-to-deep Parallel Vision Mamba Layer (PVML) (based on the Mamba State Space Model) captures long-range dependencies and cross-parcel semantic consistency with near-linear computational complexity. This dual mechanism effectively alleviates the under-segmentation of small parcels typical of U-Net and over-segmentation of large parcels observed in SegFormer, thereby leading to simultaneous improvements in boundary-sensitive metrics (

IoU,

F1) and global-consistency metrics (

OA,

Kappa). Complementarily, the D4 multi-source and multi-temporal feature subset, constructed via JM-distance-based joint selection, provides a low-redundancy and highly separable input space: Sentinel-1 VV/VH polarizations offer scattering robustness that suppresses salt-and-pepper noise caused by clouds or highly reflective surfaces, while Sentinel-2 red-edge and water-sensitive indices describe canopy physiological–structural dynamics and moisture conditions. Their temporal complementarity significantly enhances the model’s spatial fidelity and classification stability across fragmented landscapes and mixed backgrounds (e.g., forest–farmland ecotones, irrigation networks). Quantitatively, APM-UNet achieved a

PA 90.73%,

OA 96.21%,

Kappa 0.945,

Recall 91.58%,

IoU 0.81, and

F1 0.92, outperforming Vision-Mamba by approximately 2.8 percentage points and 0.024, and yielding visibly sharper boundaries and higher patch connectivity (

Figure 6;

Table 5). Overall, the integrated ASL + PVML × D4 (select-then-learn) paradigm attained a refined balance among accuracy, spatial continuity, and computational efficiency, demonstrating strong potential for within-season updates and large-scale mapping. Nevertheless, the model’s performance remains sensitive to temporal quality, cross-sensor co-registration, and class imbalance; extreme cloud contamination, temporal gaps, or substantial S1/S2 misalignment may degrade boundary sharpness and connectivity, while imbalance can suppress minority-class recall. Future work should focus on adaptive temporal weighting/gating, domain adaptation and cross-regional transfer, and joint regularization of boundary consistency and uncertainty (e.g., energy-functional or Kalman-based confidence propagation), while exploring lightweight coupling with differentiable contour or level-set layers to further improve boundary expressiveness, reliability, and inference robustness without significant increases in model complexity.

In relation to existing soybean-mapping studies, these findings highlight three specific advances of the proposed framework. First, compared with traditional approaches that rely on single-source optical imagery and heuristic feature sets or generic feature-ranking schemes, the JM-guided, phenology-aware pre-filtering in APM-UNet produces a compact and physically interpretable multi-source feature subset while still achieving state-of-the-art accuracy, thereby reducing redundancy and mitigating overfitting in fragmented landscapes. Second, relative to mainstream CNN- and Transformer-based segmentation networks reported in the literature, which typically improve accuracy at the cost of substantially higher parameter counts and quadratic self-attention complexity, the combination of ASL and PVML/Mamba in APM-UNet attains competitive or superior IoU and F1 with comparable model size and near-linear computational complexity, offering a more practical balance between accuracy and efficiency for large-area crop mapping. Third, whereas many previous works are constrained to single-phase or single-sensor configurations, our explicit integration of multi-temporal Sentinel-2 spectral–index information with Sentinel-1 VV/VH backscatter demonstrates clear gains in boundary fidelity, parcel connectivity, and minority-class recall, underscoring the value of a “filter-then-learn” design that jointly optimizes data, features, and architecture for operational soybean monitoring.

5.4. Regional Pattern and Driving Mechanisms

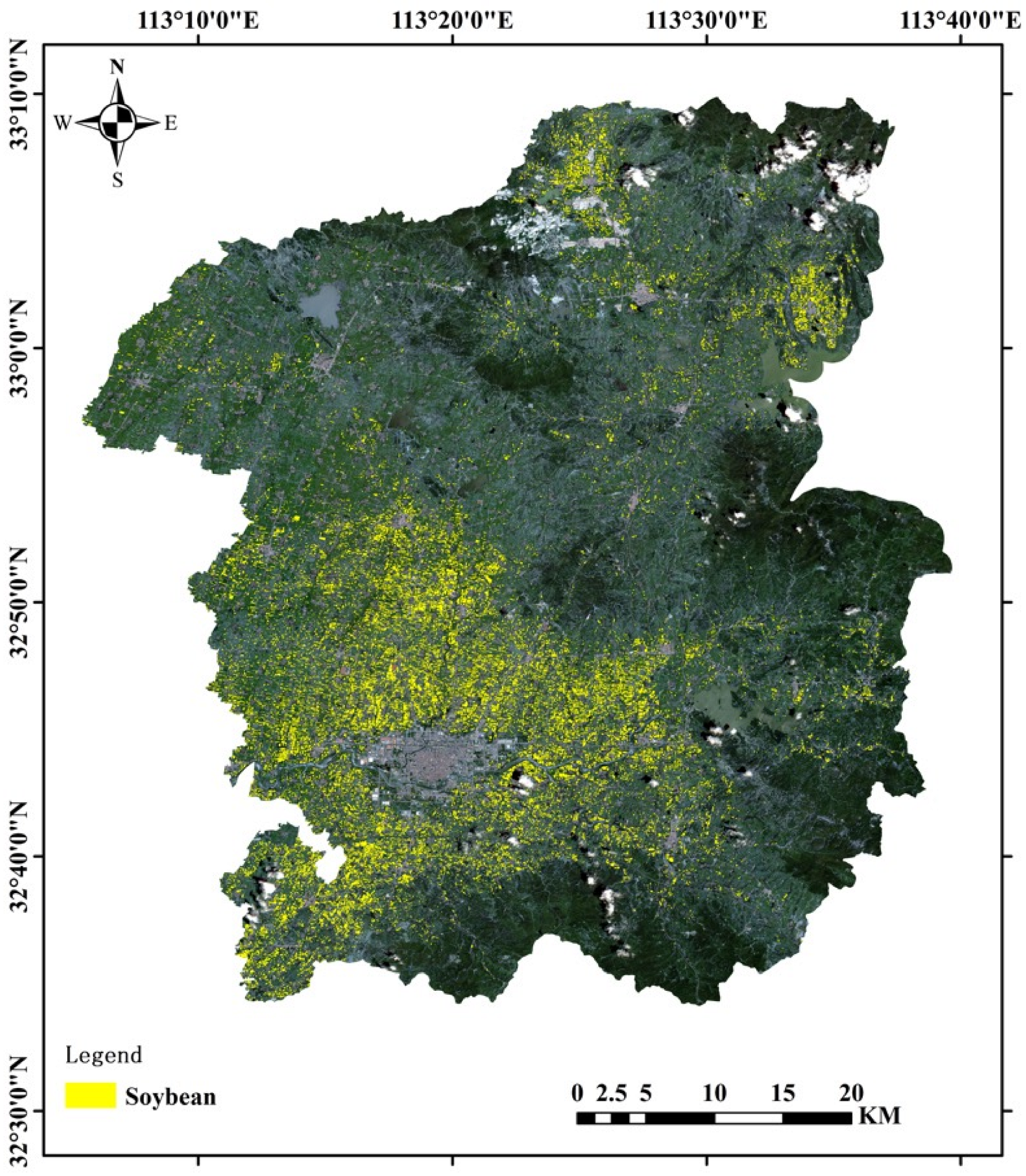

As revealed by the county-wide map in

Figure 8, soybean cultivation is markedly concentrated in the southwestern sector of Biyang County. This pattern emerges from the joint action of topography–soil–irrigation/drainage and industrial–institutional drivers: flatter terrain, gentle slopes, and well-drained soils favor stable mechanization; concentrations of high-standard farmland with regular parcel geometry and dense canal/field-road networks reduce unit operating costs; compared with flood-prone zones, the southwest shows lower waterlogging risk and smaller inter-annual variability, making yields and returns more predictable; denser cooperatives and storage facilities shorten transport distances and strengthen market pull; and long-term rotations (e.g., with maize) utilize soybean biological nitrogen fixation, reinforcing path dependence and diffusion effects. In terms of area consistency, the official soybean area is 29.62 ha, while our algorithm estimates 28.95 ha, i.e., an absolute difference of 0.67 ha (2.26%), indicating close agreement. Methodologically, the APM-UNet × D4 setting (JM-selected multi-source, multi-temporal features) is robust at both local and global scales: as quantified in

Table 6, the D4 configurations (U4, S4, V4, AU4) achieved the highest

OA,

IoU and

F1 among the four feature sets (D1–D4) for all three backbone networks—for example, in U-Net, JM optimization increases

OA from 85.53% (U1) to 90.16% (U4) and

IoU from 0.6413 to 0.6704, while AU4 attained a

PA = 92.81%,

OA = 97.95%,

IoU = 0.7986 and

F1 = 0.9324—indicating that D4 retains highly discriminative phenological and polarization cues while suppressing redundancy and inter-feature correlation, and thus empirically outperforms D1/D2/D3 across models; the ASL × PVML/SSM synergy enhances boundary continuity, parcel integrity, and cross-parcel consistency, which substantiates the spatial coherence and semantic purity observed in the full-coverage map (consistent with

Figure 7 and

Table 6). For broader deployment, we note potential sensitivities: severe cloud contamination or minor S1/S2 misregistration may affect local boundary coherence, while phenological spectral similarity and class imbalance can induce localized confusion; these can be further mitigated under the filter-then-learn paradigm (JM-based pre-filtering) combined with temporal weighting/gating. Overall, the spatial continuity, boundary fidelity, and reliable area estimation achieved by APM-UNet × D4 provide a transferable pathway for county-scale acreage verification, subsidy auditing, and crop-structure monitoring.

6. Conclusions

This study proposed APM-UNet, a lightweight and interpretable segmentation framework that couples JM-distance–guided feature selection with an attention-enhanced encoder–decoder for high-resolution soybean mapping from multi-temporal Sentinel-1/2 data. Under a unified evaluation protocol, the framework achieved field-scale soybean maps with overall accuracy close to 98% and F1 scores above 0.93, consistently outperforming U-Net, SegFormer and Vision-Mamba, and confirming the effectiveness of the proposed “filter-then-learn” strategy.

Methodologically, APM-UNet was designed with generalizability and efficiency in mind. JM-based pre-filtering compresses the original feature space into a compact, physically interpretable subset that preserves stable class separability while reducing redundancy and parameter count, which is expected to facilitate transfer to other crops, seasons and sensor configurations under similar data conditions. The use of state-space modules with near-linear complexity, instead of quadratic-cost attention, supports large-area mapping and repeated updates and, together with the results in

Table 7, points to a promising computational profile for future operational crop-monitoring workflows.

At the same time, several limitations must be acknowledged. All experiments were confined to a soybean-dominated county in southern Henan and to a single growing season, so neither the learned representations nor the marginal contributions of ASL and PVML have yet been validated across different regions, years or cropping systems. The workflow also assumes well-registered, temporally dense Sentinel-1/2 stacks, and the current implementation remains an offline, tile-based GPU pipeline rather than a fully real-time system. Future work will therefore focus on multi-region and multi-year training, domain adaptation and active learning, and on engineering streaming data ingestion, incremental updating and the integration of ancillary data (e.g., DEM and cadastral boundaries), with the goal of evolving APM-UNet into a near-real-time tool for in-season soybean monitoring and broader agricultural and ecological applications.