Characterizing the Surface Grain Size Distribution in a Gravel-Bed River Using UAV Optical Imagery and SfM Photogrammetry

Highlights

- Surface roughness metrics derived from UAV-SfM point clouds effectively characterize grain-size distributions in gravel-bed rivers.

- A reach-scale grain size–roughness relation was established for riverbeds with wide grain-size variability.

- The integrated relation enables rapid estimation of riverbed grain-size distributions using UAV-SfM-derived roughness.

- Applicability tests indicate more reliable grain-size estimation for coarser grains than for finer grains in heterogeneous gravel beds.

Abstract

1. Introduction

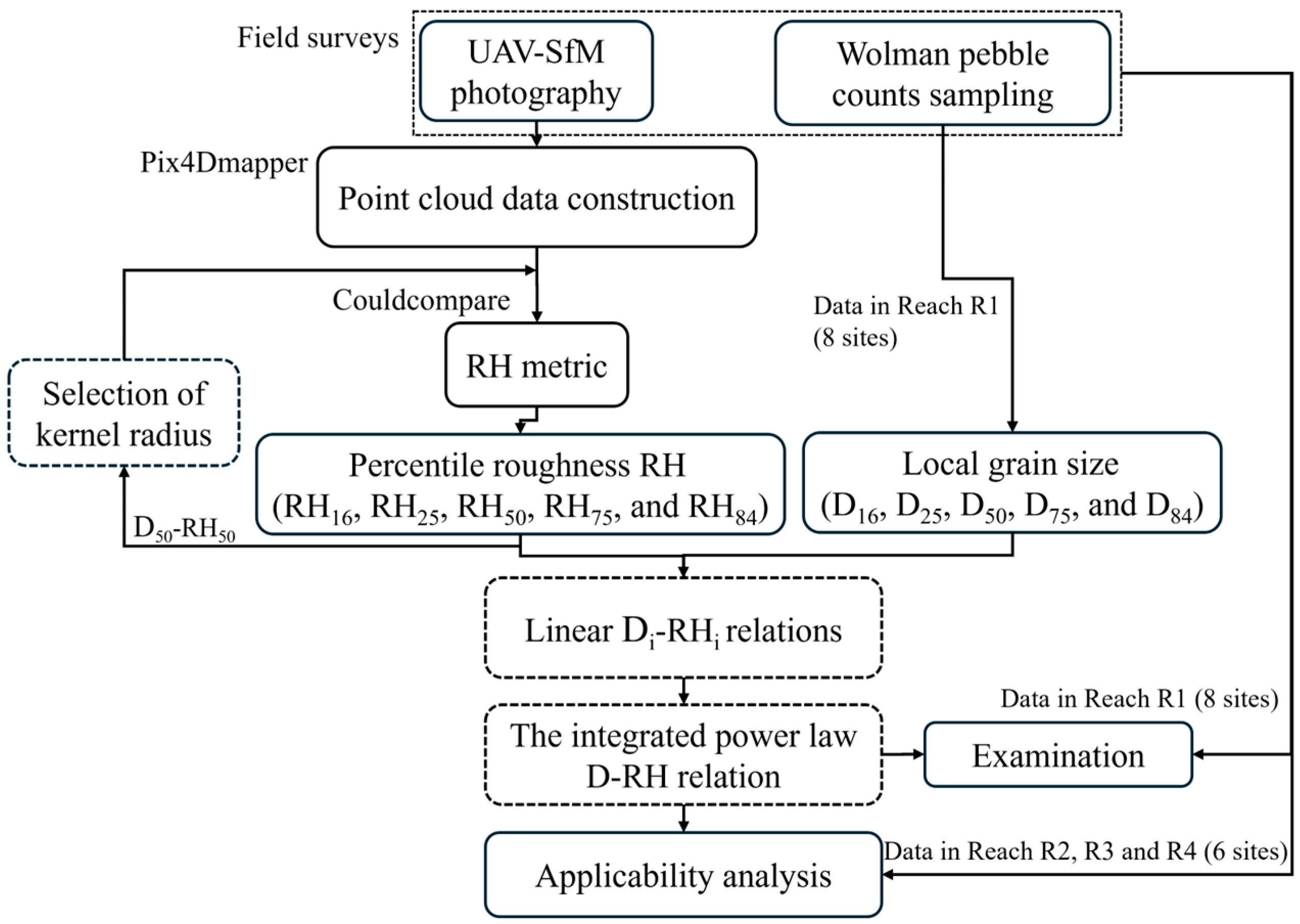

2. Materials and Methods

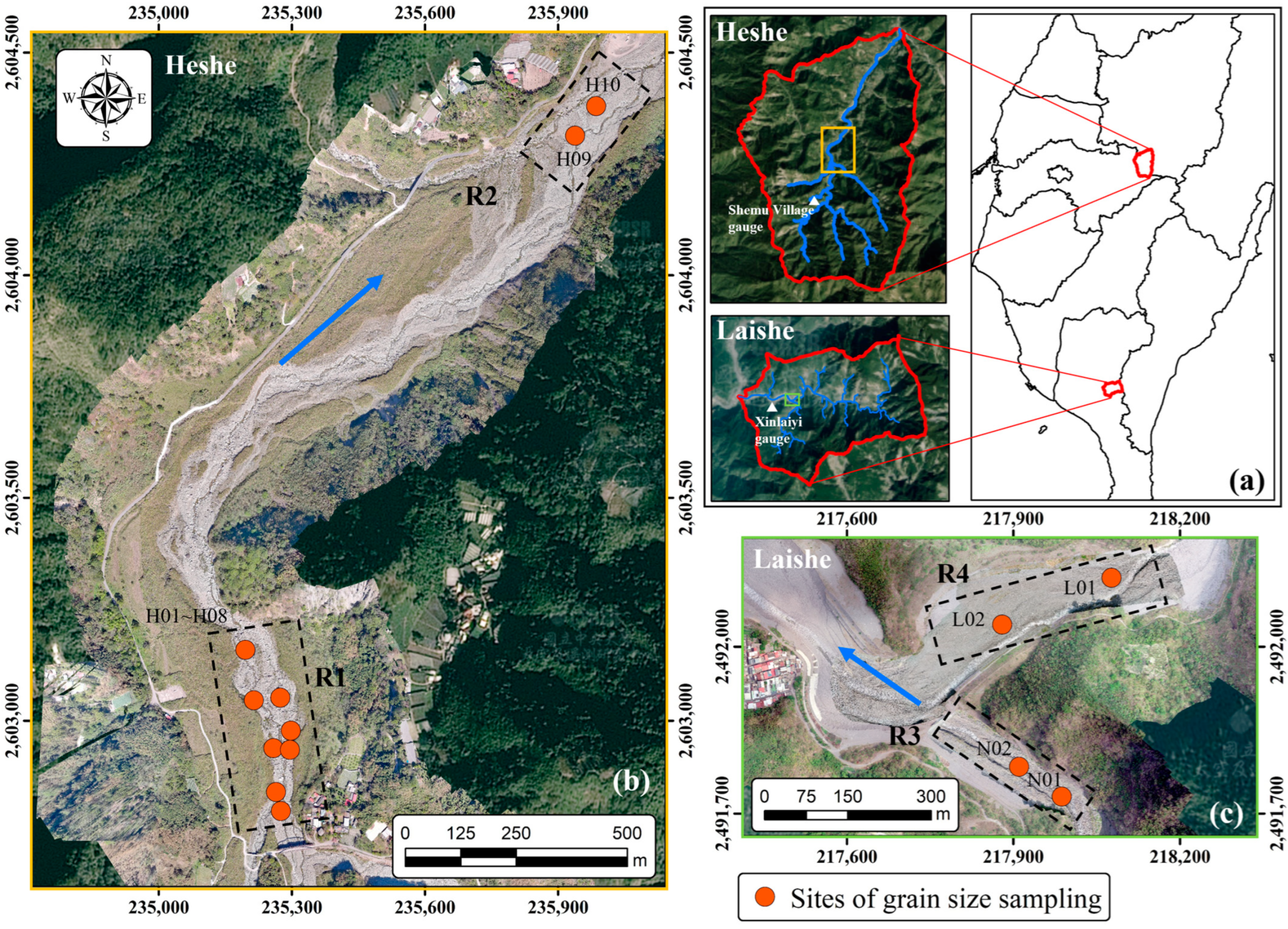

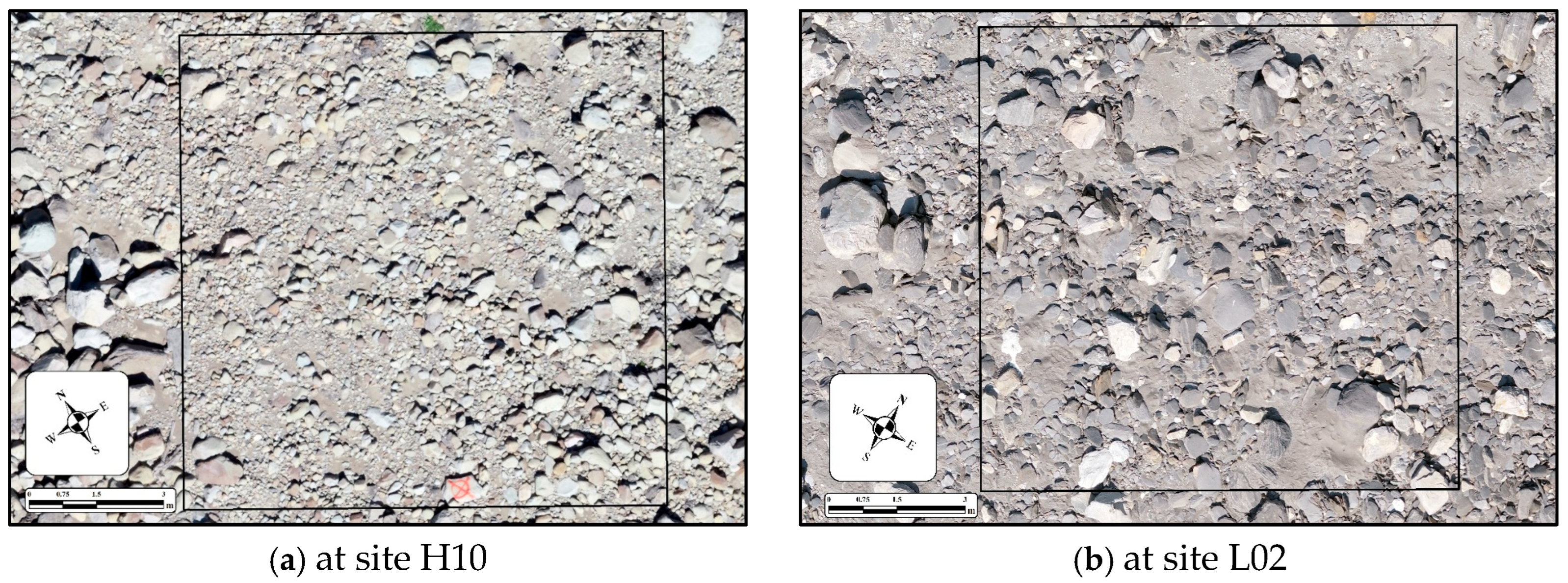

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Field Surveys

2.2.1. UAV Photography and Point Cloud Data

2.2.2. Wolman Pebble Counts Sampling Method

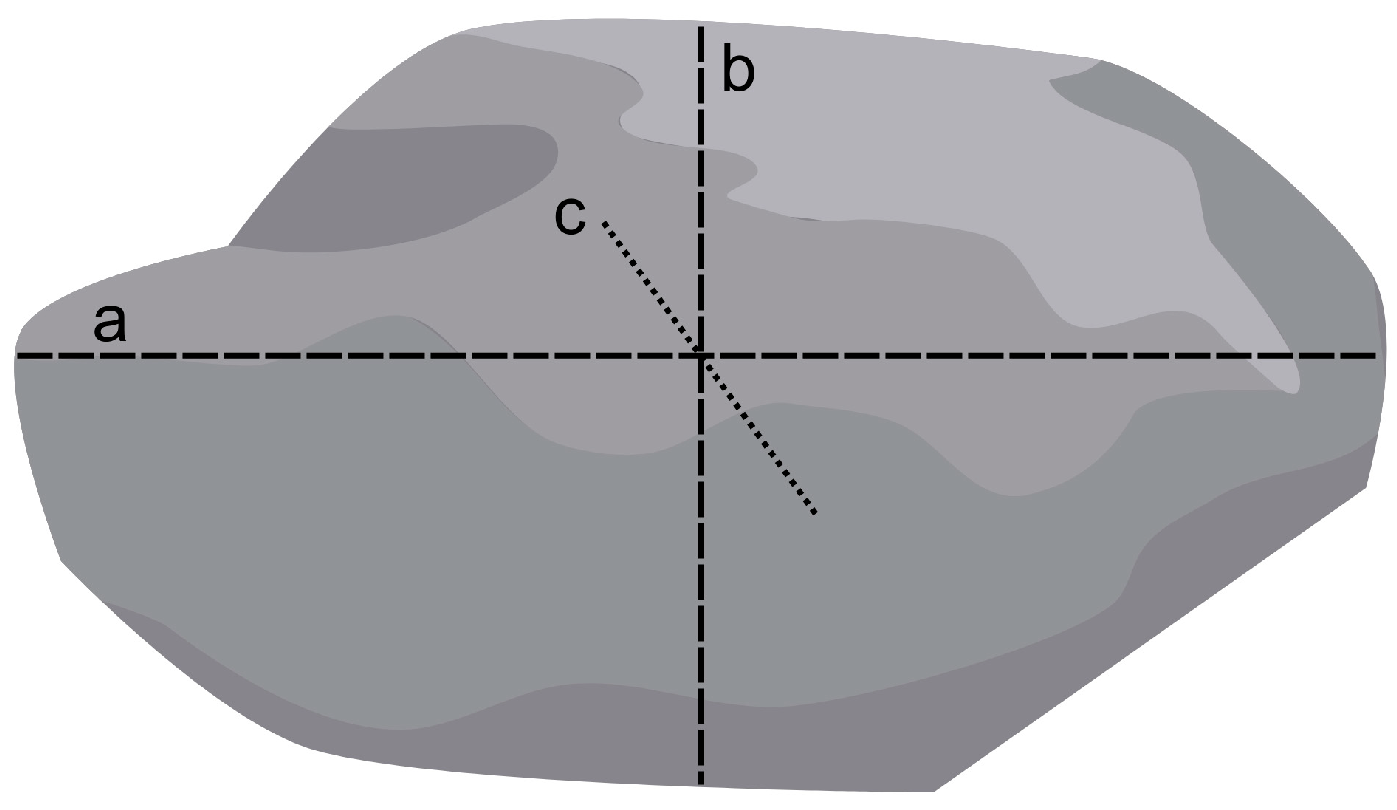

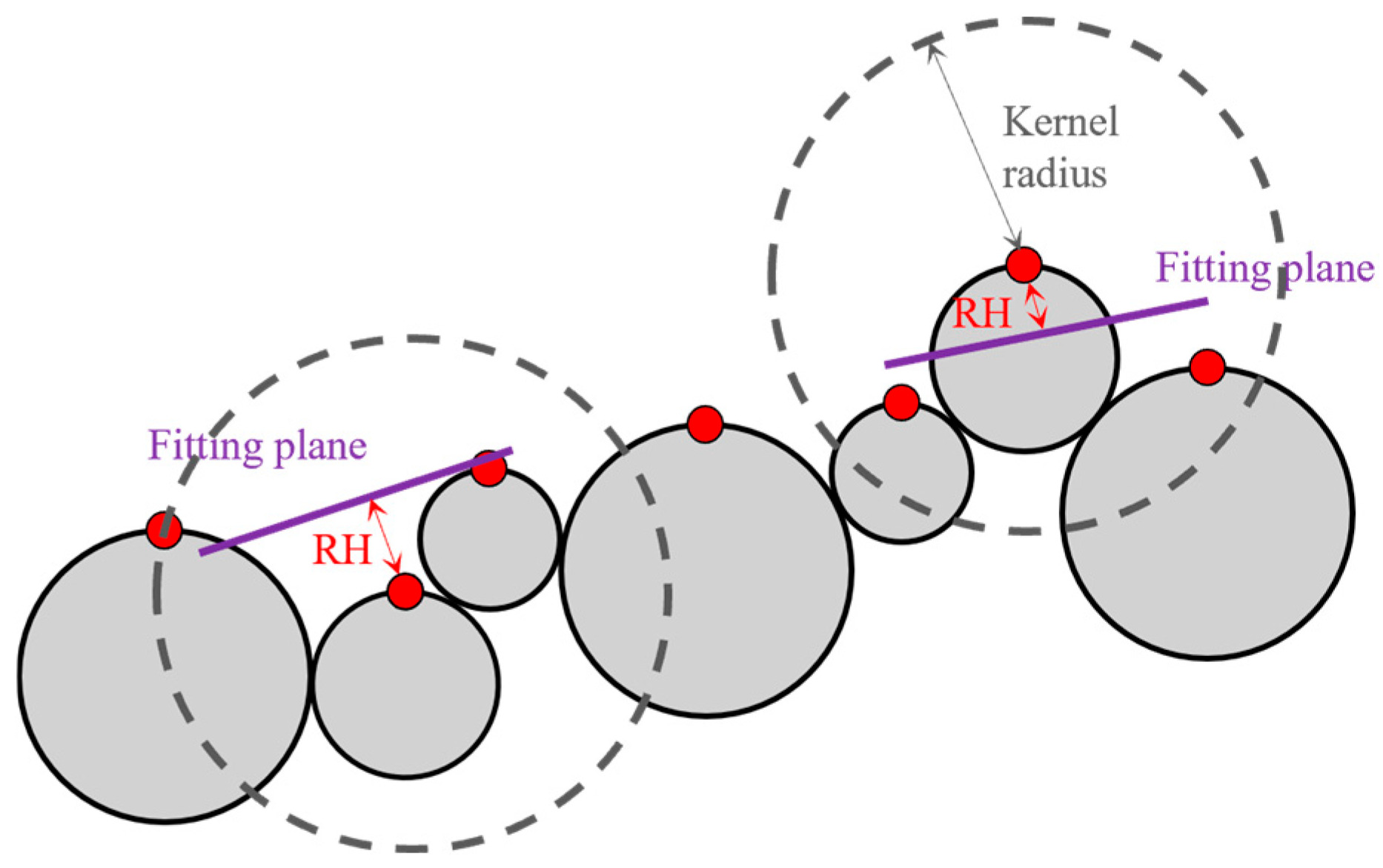

2.3. Roughness Metric

2.3.1. Concept of Roughness Height

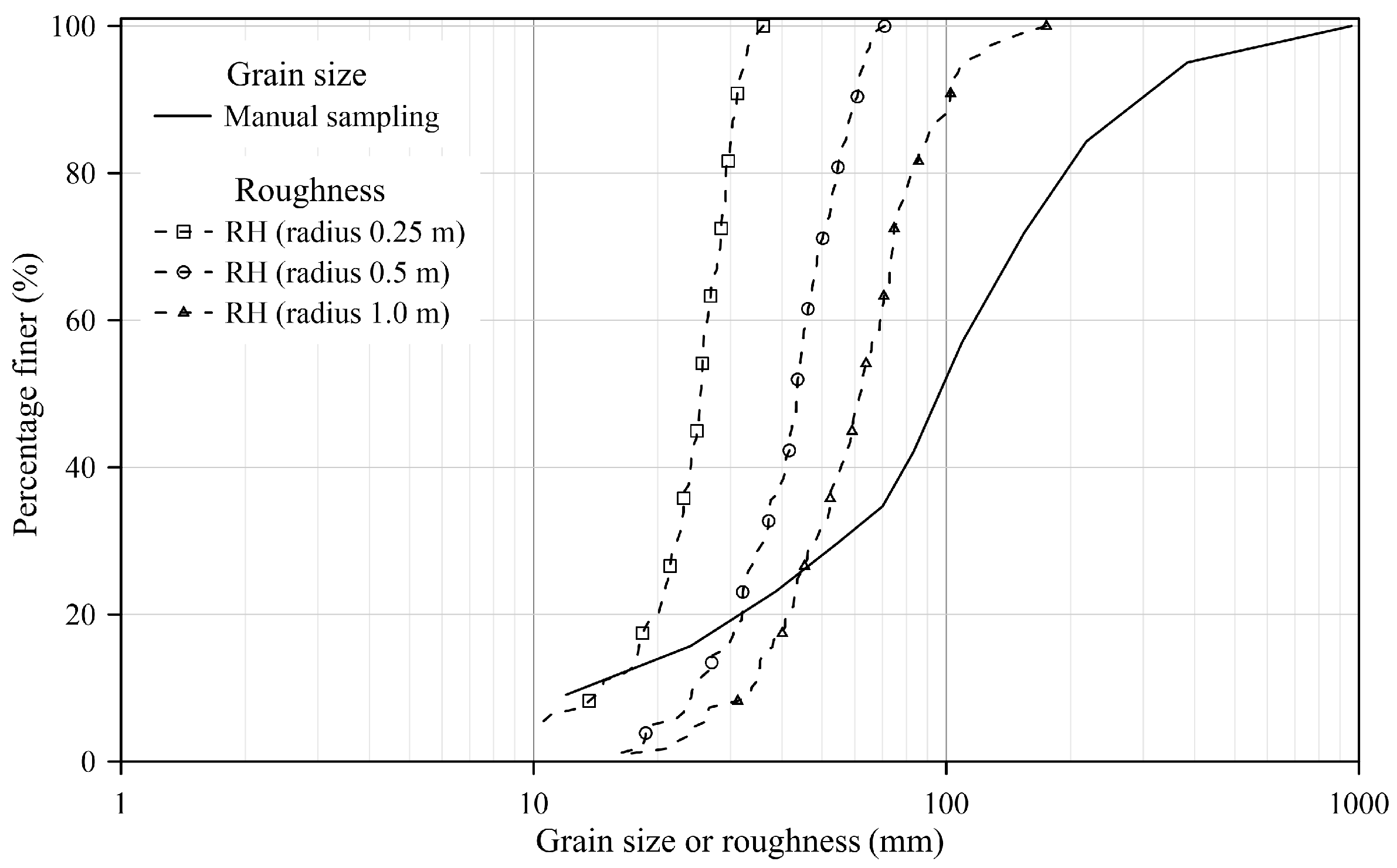

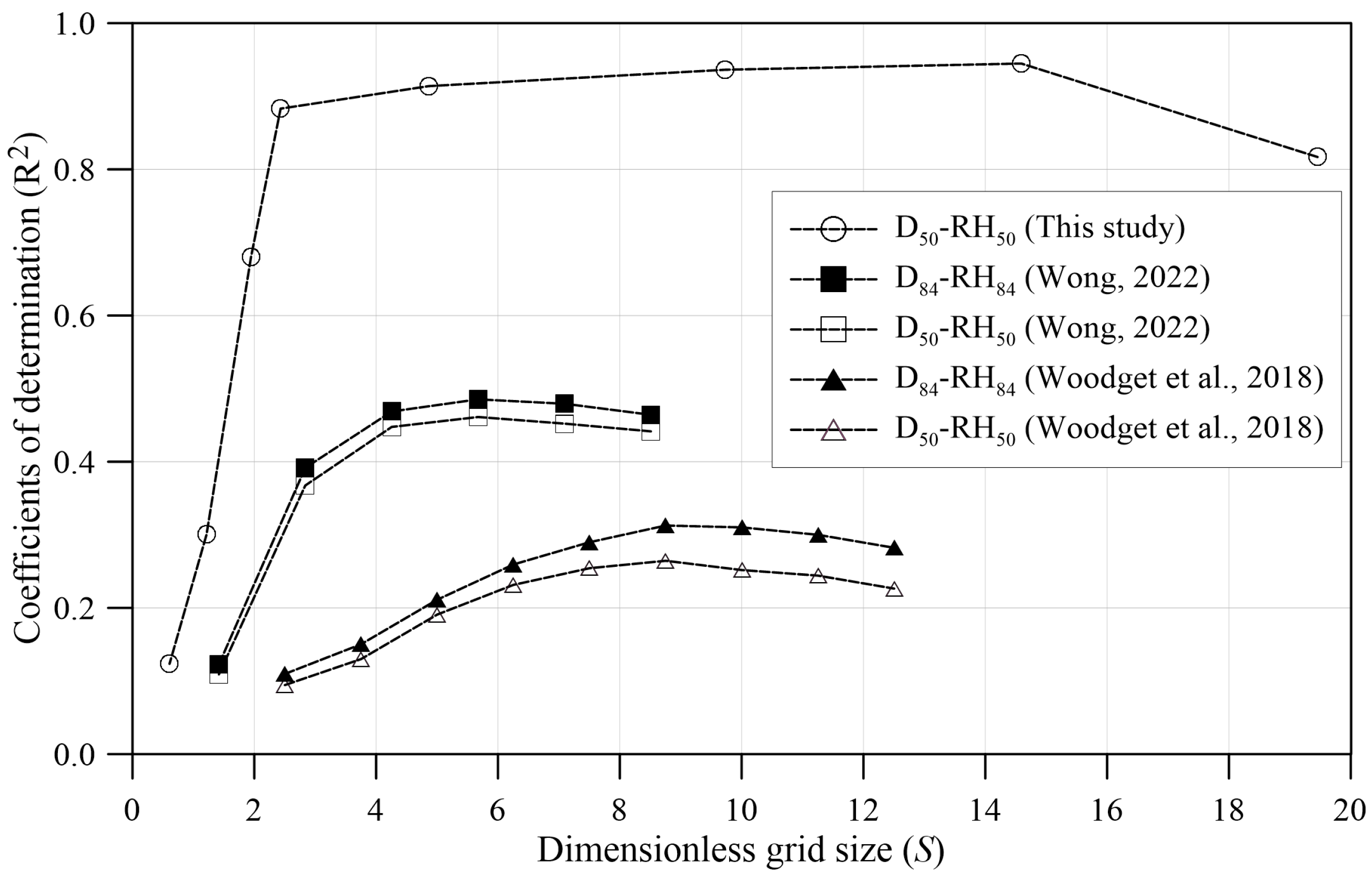

2.3.2. Grid Size for Computing Roughness Metrics

2.3.3. Correlation Analysis of Grain Size-Roughness Relationship

3. Results

3.1. Grid Size for Computing Roughness Metrics

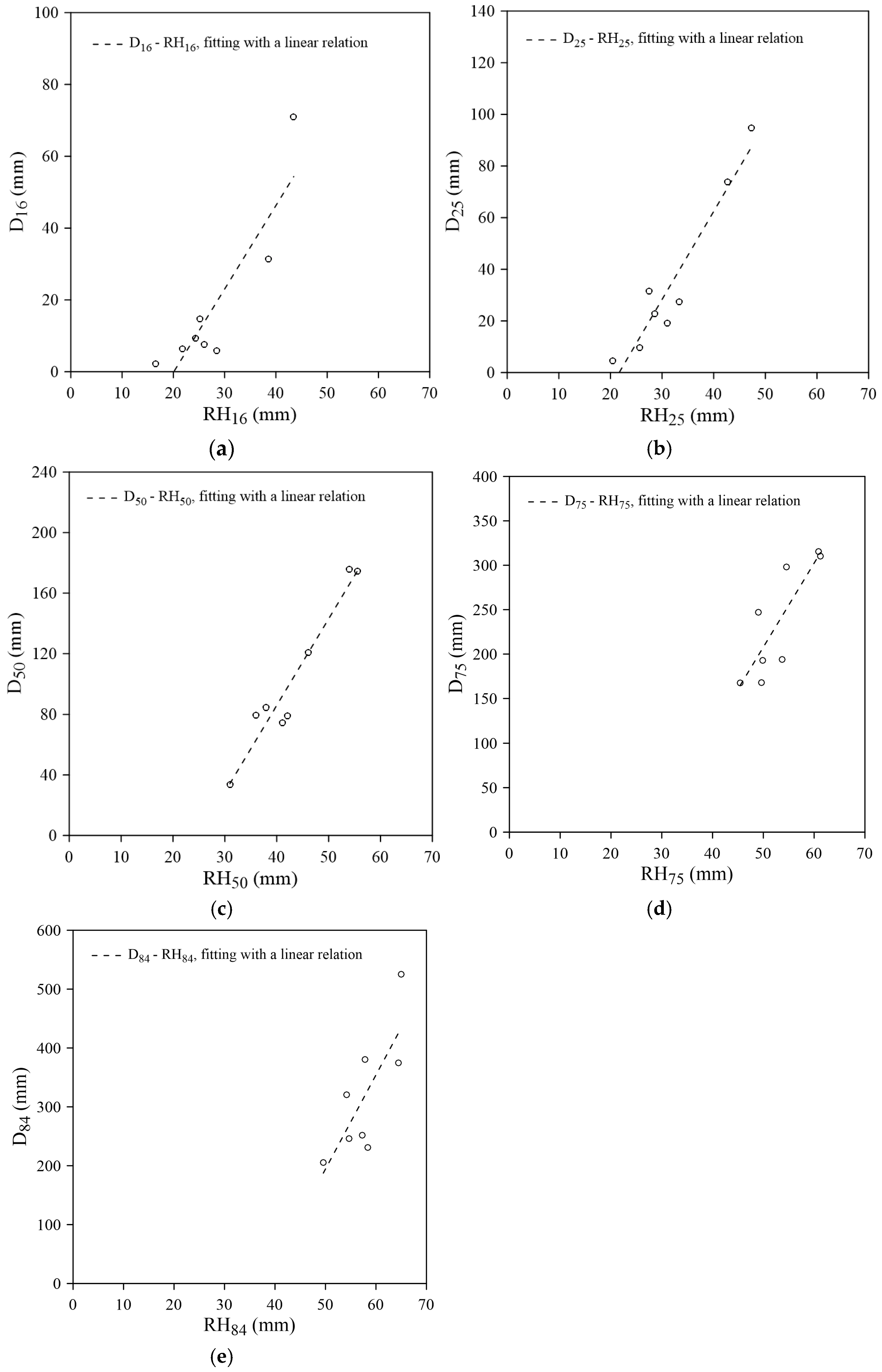

3.2. Linear Correlation Between Grain Size and Roughness Height

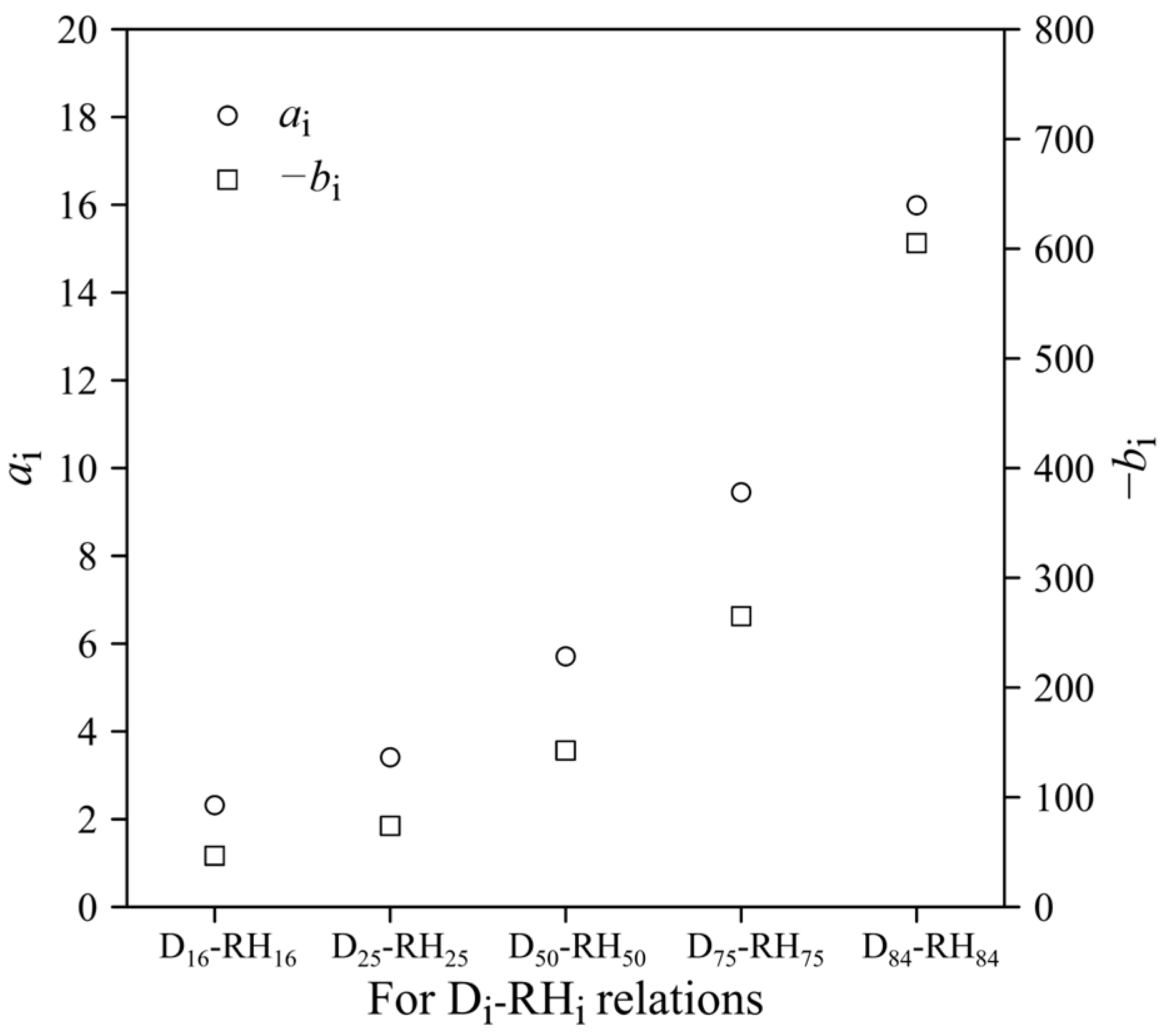

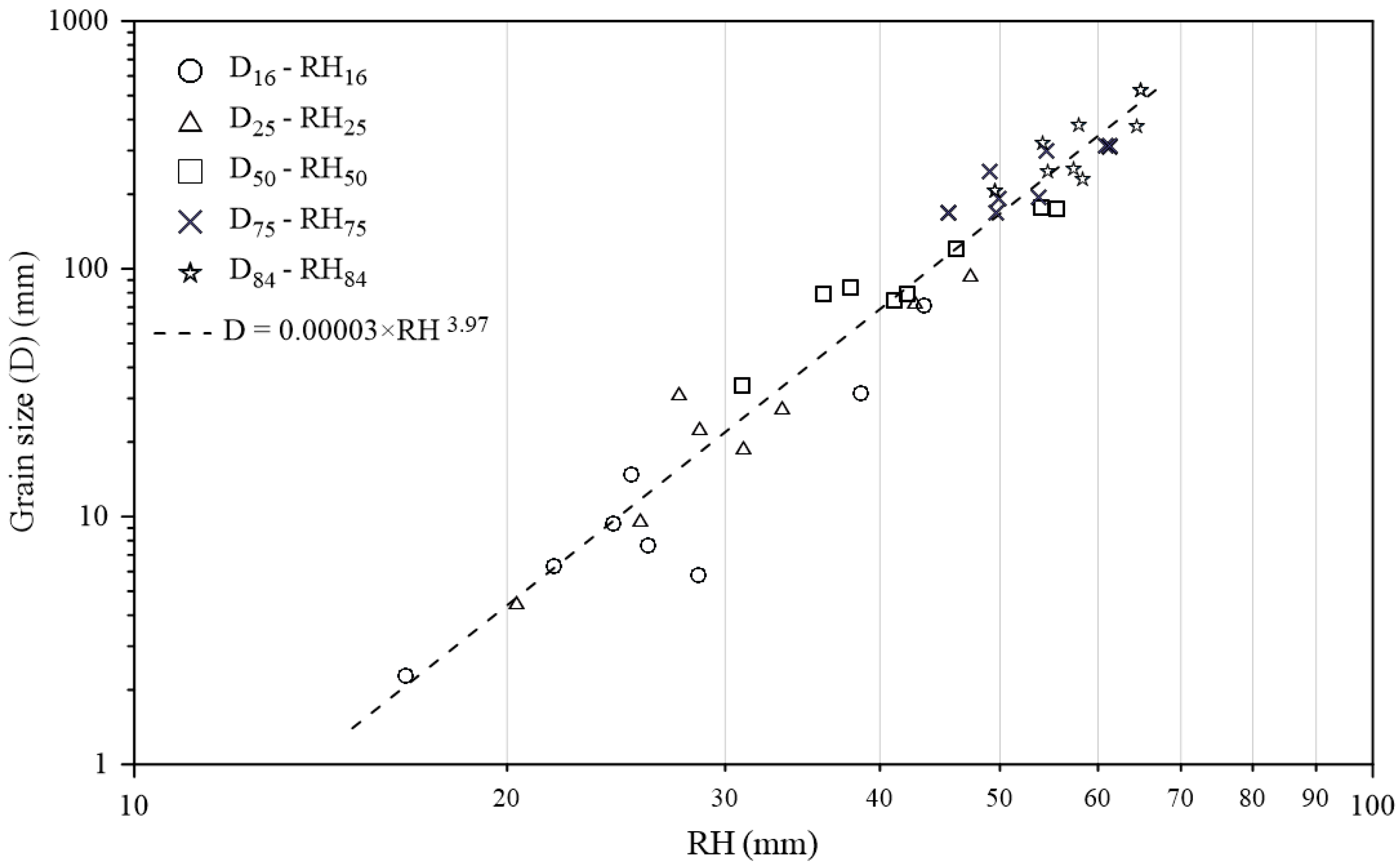

3.3. Integrated Di-RHi Relations by a Power Law

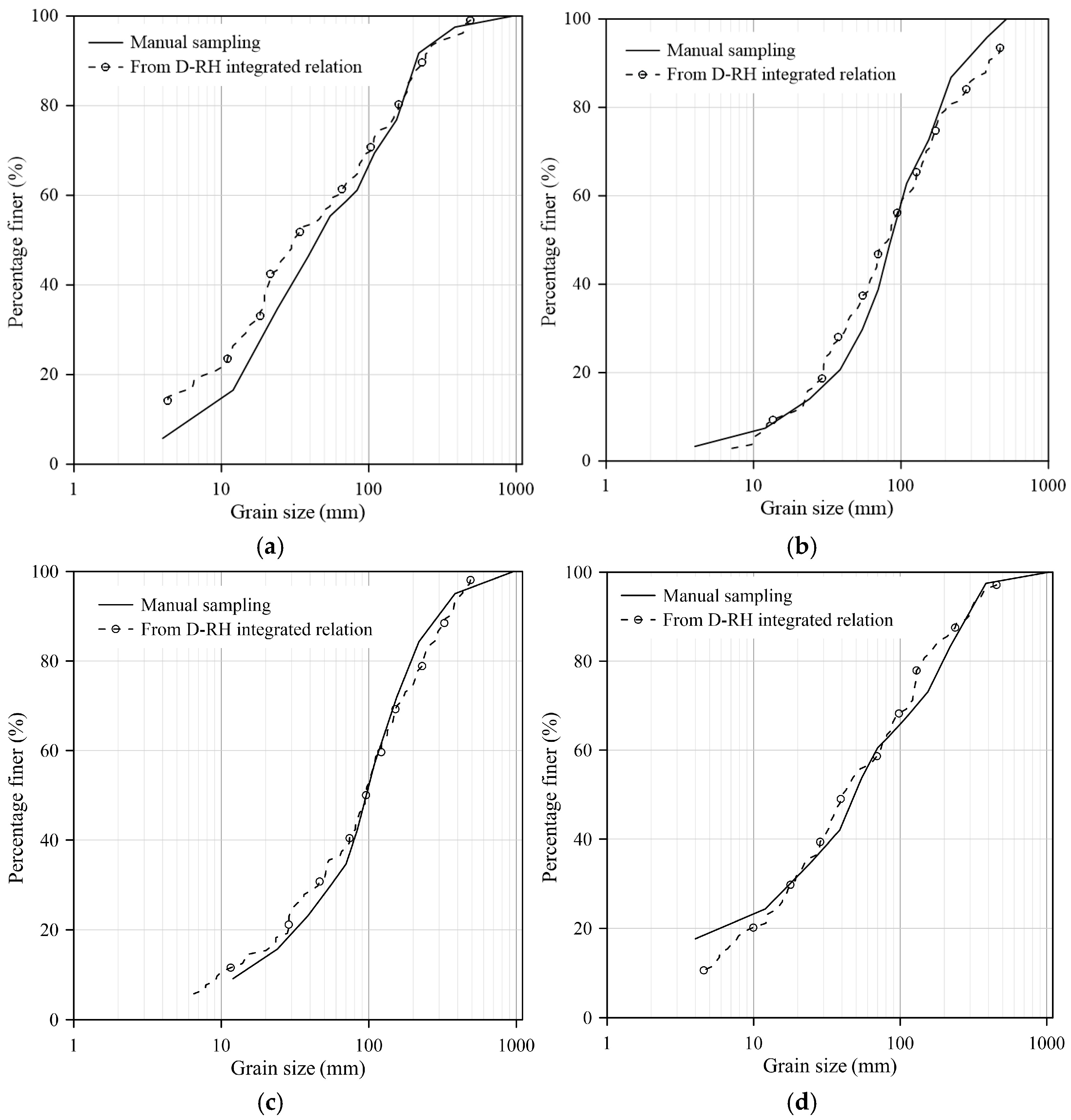

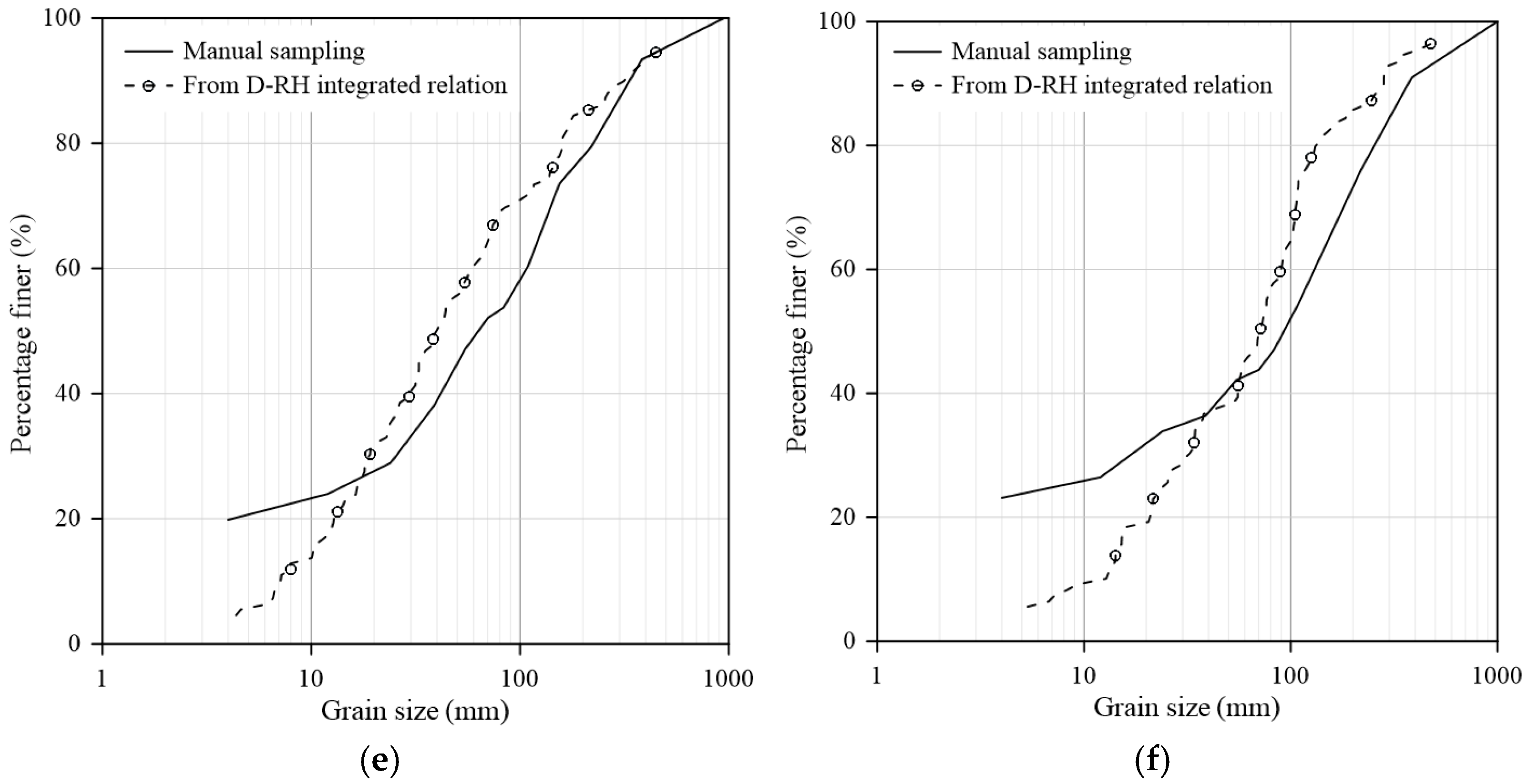

3.4. Examination of the Integrated Grain Size-Roughness Relation

3.5. Applicability of the Integrated Grain Size-Roughness Relation

4. Discussion

4.1. Grid Size Effect on Roughness Evaluation

4.2. Linear Correlation Between Grain Size and Roughness Height

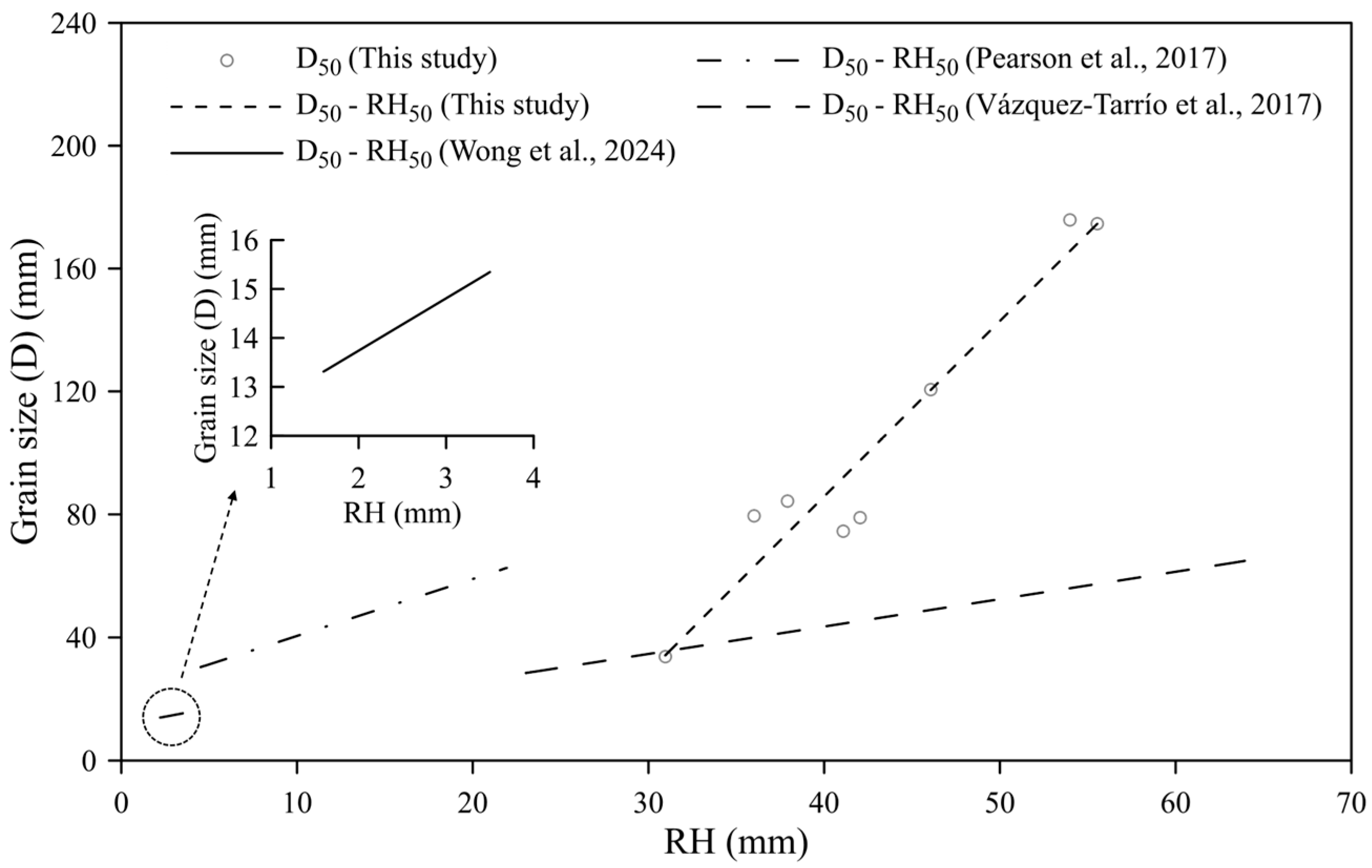

4.3. Integrated Grain Size—Roughness Relation

4.3.1. Examination and Applicability of the Integrated Relation

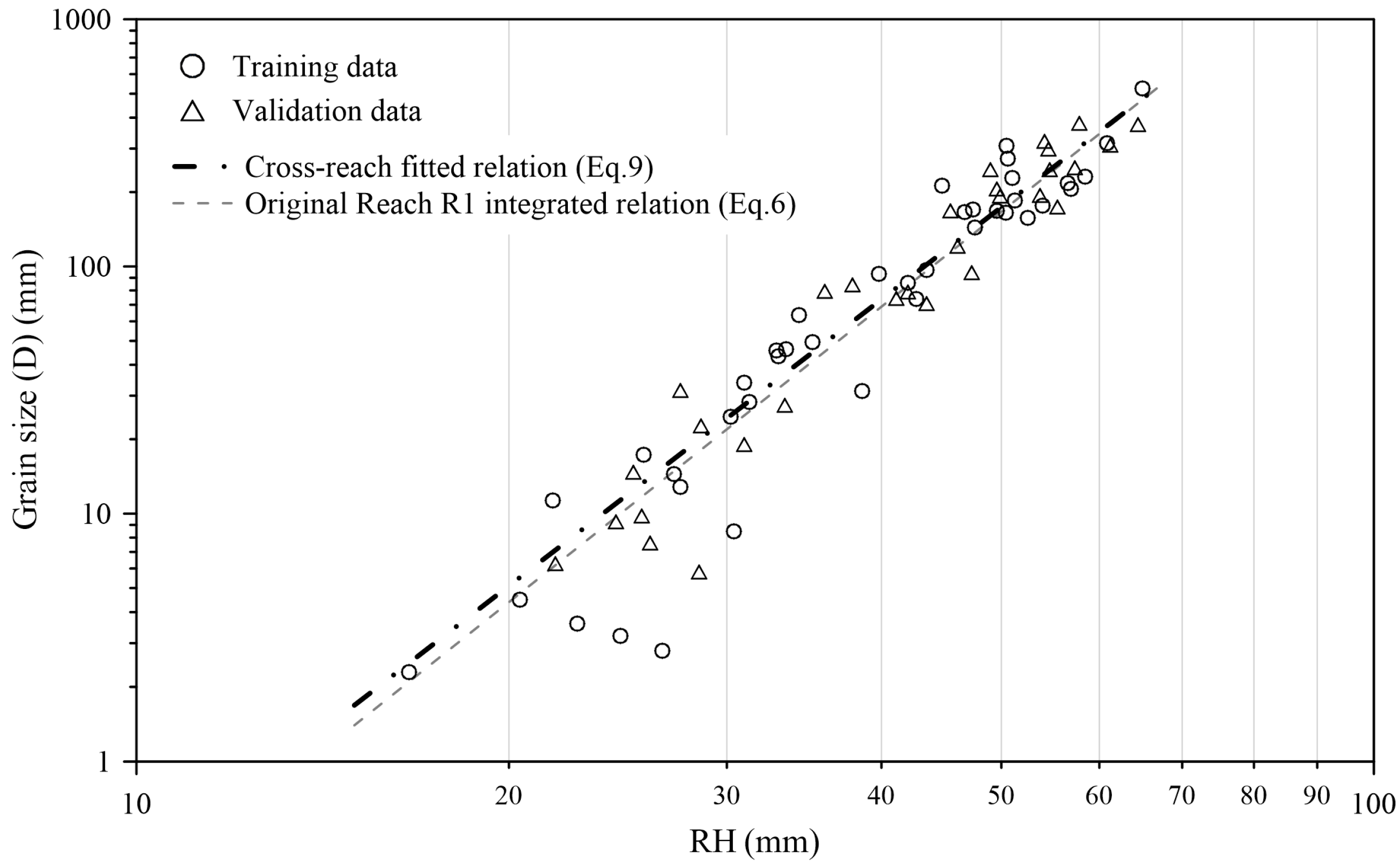

4.3.2. Cross-Reach Validation of the Integrated Relation

4.3.3. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Site | D10 | D16 | D25 | D30 | D50 | D60 | D75 | D84 | D90 | Dmax | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H01 | 3.3 | 14.7 | 31.5 | 40.9 | 84.3 | 104.4 | 167.6 | 205.5 | 303.3 | 1050.0 | 31.6 | 2.3 | 3.7 |

| H02 | 1.4 | 2.3 | 4.5 | 5.8 | 33.8 | 62.4 | 167.8 | 231.0 | 265.8 | 1350.0 | 43.6 | 6.1 | 10.0 |

| H03 | 2.9 | 9.3 | 22.7 | 30.1 | 78.9 | 104.5 | 193.0 | 246.1 | 356.9 | 1470.0 | 36.6 | 2.9 | 5.1 |

| H04 | 4.0 | 31.3 | 73.9 | 97.5 | 175.8 | 206.3 | 315.5 | 525.3 | 1134.6 | 2150.0 | 51.6 | 2.5 | 4.4 |

| H05 | 3.6 | 7.6 | 19.0 | 25.3 | 74.5 | 97.5 | 193.8 | 251.6 | 327.3 | 860.0 | 26.8 | 3.2 | 5.7 |

| H06 | 39.0 | 71.0 | 94.7 | 107.8 | 174.6 | 203.3 | 310.4 | 374.6 | 471.2 | 850.0 | 5.2 | 1.8 | 2.3 |

| H07 | 4.0 | 5.8 | 27.4 | 39.5 | 120.6 | 161.0 | 298.0 | 380.3 | 825.0 | 1750.0 | 40.3 | 3.3 | 8.1 |

| H08 | 4.0 | 6.3 | 9.8 | 11.7 | 79.5 | 124.3 | 247.1 | 320.8 | 467.2 | 800.0 | 31.1 | 5.0 | 7.1 |

| H09 | 6.9 | 11.3 | 17.3 | 20.7 | 45.8 | 76.7 | 144.0 | 184.4 | 211.0 | 930.0 | 11.1 | 2.9 | 4.0 |

| H10 | 16.7 | 28.3 | 46.3 | 55.1 | 85.6 | 104.1 | 164.9 | 205.9 | 284.0 | 520.0 | 6.3 | 1.9 | 2.7 |

| N01 | 13.7 | 24.6 | 43.2 | 55.4 | 97.0 | 112.2 | 157.6 | 217.0 | 265.7 | 960.0 | 8.2 | 1.9 | 3.0 |

| N02 | 2.3 | 3.6 | 12.8 | 18.7 | 49.5 | 68.9 | 166.5 | 227.8 | 265.8 | 1030.0 | 30.4 | 3.6 | 7.9 |

| L01 | 2.0 | 3.2 | 14.5 | 25.7 | 63.7 | 108.0 | 170.5 | 273.4 | 312.0 | 950.0 | 53.5 | 3.4 | 9.2 |

| L02 | 1.7 | 2.8 | 8.5 | 17.7 | 93.4 | 109.3 | 212.3 | 307.1 | 343.5 | 1000.0 | 63.2 | 5.0 | 10.5 |

| Site | RH10 | RH16 | RH25 | RH30 | RH50 | RH60 | RH75 | RH84 | RH90 | RHmax |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H01 | 22.5 | 25.2 | 27.5 | 29.3 | 37.9 | 40.9 | 45.5 | 49.6 | 53.6 | 71.2 |

| H02 | 14.5 | 16.6 | 20.4 | 23.5 | 31.0 | 37.9 | 49.6 | 58.4 | 61.8 | 70.3 |

| H03 | 22.0 | 24.4 | 28.6 | 32.4 | 42.0 | 47.3 | 49.9 | 54.7 | 61.5 | 71.7 |

| H04 | 36.1 | 38.6 | 42.7 | 46.0 | 54.0 | 58.9 | 60.9 | 65.0 | 70.6 | 82.1 |

| H05 | 24.0 | 26.0 | 31.0 | 31.9 | 41.1 | 47.7 | 53.7 | 57.3 | 64.8 | 82.8 |

| H06 | 41.1 | 43.5 | 47.3 | 49.2 | 55.5 | 57.7 | 61.2 | 64.5 | 68.9 | 84.4 |

| H07 | 26.4 | 28.5 | 33.4 | 37.7 | 46.1 | 49.0 | 54.6 | 57.8 | 63.7 | 88.6 |

| H08 | 20.2 | 21.8 | 25.6 | 28.8 | 36.0 | 42.8 | 49.0 | 54.2 | 66.3 | 88.6 |

| H09 | 18.9 | 21.7 | 25.7 | 27.4 | 32.9 | 39.6 | 47.6 | 51.3 | 54.8 | 70.2 |

| H10 | 28.4 | 31.3 | 33.5 | 35.4 | 42.0 | 45.1 | 50.4 | 56.9 | 62.1 | 77.8 |

| N01 | 24.9 | 30.2 | 33.0 | 36.2 | 43.5 | 46.2 | 52.5 | 56.6 | 60.5 | 71.0 |

| N02 | 20.4 | 22.7 | 27.5 | 29.0 | 35.2 | 40.7 | 46.7 | 51.0 | 57.7 | 76.9 |

| L01 | 21.8 | 24.6 | 27.2 | 28.2 | 34.3 | 38.0 | 47.4 | 50.6 | 58.8 | 78.5 |

| L02 | 25.5 | 26.6 | 30.4 | 32.5 | 39.8 | 42.3 | 44.8 | 50.5 | 57.0 | 84.6 |

References

- Leopold, L.B.; Wolman, M.G.; Miller, J.P. Fluvial Processes in Geomorphology; Courier Dover Publications: New York, NY, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Rosgen, D.L. A Classification of Natural Rivers. Catena 1994, 22, 169–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bathurst, J.C. Flow resistance estimation in mountain rivers. J. Hydraul. Eng. 1985, 111, 625–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aberle, J.; Smart, G.M. The influence of roughness structure on flow resistance on steep slopes. J. Hydraul. Res. 2003, 41, 259–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamb, M.P.; Brun, F.; Fuller, B.M. Hydrodynamics of steep streams with planar coarse-grained beds: Turbulence, flow resistance, and implications for sediment transport. Water Resour. Res. 2017, 53, 2240–2263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iverson, R.M. The physics of debris flows. Rev. Geophys. 1997, 35, 245–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, T. Debris Flow: Mechanics, Prediction and Countermeasures; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tullos, D.; Wang, H.W. Morphological responses and sediment processes following a typhoon-induced dam failure, Dahan River, Taiwan. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2014, 39, 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajdukiewicz, H.; Wyzga, B.; Mikus, P.; Zawiejska, J.; Radecki-Pawlik, A. Impact of a large flood on mountain river habitats, channel morphology, and valley infrastructure. Geomorphology 2016, 272, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, J.G.; Wang, S.S.Y.; Jia, Y.F. The applications of the enhanced CCHE2D model to study the alluvial channel migration processes. J. Hydraul. Res. 2001, 39, 469–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolman, M.G. A method of sampling coarse river-bed material. EOS Trans. Am. Geophys. Union 1954, 35, 951–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunte, K.; Abt, S.R. Sampling Surface and Subsurface Particle-Size Distributions in Wadable Gravel-and Cobble-Bed Streams for Analyses in Sediment Transport, Hydraulics, and Streambed Monitoring; US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station: Fort Collins, CO, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, D.J.; Rice, S.P.; Reid, I. A transferable method for the automated grain sizing of river gravels. Water Resour. Res. 2005, 41, W07020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.C.; Wang, C.K.; Lo, H.P. FKgrain: A topography-based software tool for grain segmentation and sizing using factorial kriging. Earth Sci. Inform. 2021, 14, 2411–2421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.H.; Shao, Y.C.; Wang, C.K.; Wu, F.C. Analysis of Bed Material Grain Size Distribution Using Digital Photosieving. J. Taiwan Agric. Eng. 2008, 54, 16–32. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Detert, M.; Weitbrecht, V. Automatic object detection to analyze the geometry of gravel grains–a free stand-alone tool. In River Flow 2012, Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Fluvial Hydraulics “River Flow 2012”, San José, Costa Rica, 5–7 September 2012; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2012; pp. 595–600. [Google Scholar]

- Woodget, A.; Fyffe, C.; Carbonneau, P. From manned to unmanned aircraft: Adapting airborne particle size mapping methodologies to the characteristics of sUAS and SfM. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2018, 43, 857–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, T.; Khanal, S.; Zhao, K.; Lyon, S.W. Grain size estimation in fluvial gravel bars using uncrewed aerial vehicles: A comparison between methods based on imagery and topography. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2024, 49, 374–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, D.J.; Rollet, A.J.; Piegay, H.; Rice, S.P. Maximizing the accuracy of image-based surface sediment sampling techniques. Water Resour. Res. 2010, 46, W02508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasington, J.; Vericat, D.; Rychkov, I. Modeling river bed morphology, roughness, and surface sedimentology using high resolution terrestrial laser scanning. Water Resour. Res. 2012, 48, W11519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heritage, G.L.; Milan, D.J. Terrestrial laser scanning of grain roughness in a gravel-bed river. Geomorphology 2009, 113, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodge, R.; Brasington, J.; Richards, K. Analysing laser-scanned digital terrain models of gravel bed surfaces: Linking morphology to sediment transport processes and hydraulics. Sedimentology 2009, 56, 2024–2043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, E.; Smith, M.; Klaar, M.; Brown, L. Can high resolution 3D topographic surveys provide reliable grain size estimates in gravel bed rivers? Geomorphology 2017, 293, 143–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez-Tarrío, D.; Borgniet, L.; Liébault, F.; Recking, A. Using UAS optical imagery and SfM photogrammetry to characterize the surface grain size of gravel bars in a braided river (Vénéon River, French Alps). Geomorphology 2017, 285, 94–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodget, A.S.; Austrums, R. Subaerial gravel size measurement using topographic data derived from a UAV-SfM approach. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2017, 42, 1434–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westoby, M.J.; Brasington, J.; Glasser, N.F.; Hambrey, M.J.; Reynolds, J.M. Structure-from-Motion’ photogrammetry: A low-cost, effective tool for geoscience applications. Geomorphology 2012, 179, 300–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Geological Data Warehouse (Geological Survey and Mining Management Agency in Taiwan). Available online: https://geomap.gsmma.gov.tw/gwh/gsb97-1/sys8a/t3/index1.cfm (accessed on 3 July 2025).

- Chen, S.C.; Wu, C.H.; Chao, Y.C.; Shih, P.Y. Long-term impact of extra sediment on notches and incised meanders in the Hoshe River, Taiwan. J. Mt. Sci. 2013, 10, 716–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, K.J.; Tseng, C.W.; Tseng, C.M.; Liao, T.C.; Yang, C.J. Application of unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV)-acquired topography for quantifying typhoon-driven landslide volume and its potential topographic impact on rivers in mountainous catchments. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 6102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eltner, A.; Kaiser, A.; Castillo, C.; Rock, G.; Neugirg, F.; Abellán, A. Image-based surface reconstruction in geomorphometry–merits, limits and developments. Earth Surf. Dyn. 2016, 4, 359–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahal, S.; Imaizumi, F.; Takayama, S. Spatio-temporal distribution of boulders along a debris-flow torrent assessed by UAV photogrammetry. Geomorphology 2025, 480, 109757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CloudCompare (Version 2.14) [GPL Software]. 3D Point Cloud and Mesh Processing Software Open Source Project. Available online: http://www.cloudcompare.org/ (accessed on 3 July 2025).

- Wong, T. Estimation of Grain Sizes in a River Through UAV-Based SfM Photogrammetry. Master’s Thesis, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, J.M.; Rickenmann, D.; Turowski, J.M.; Kirchner, J.W. Self-adjustment of stream bed roughness and flow velocity in a steep mountain channel. Water Resour. Res. 2015, 51, 7838–7859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Researchers | Sediment Description (Grain Size Range) | Grain Size Sampling | Data | Roughness Metric * (Grid Size) | Grain Size-Roughness Relation (in mm) | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heritage and Milan [21] | Gravel-bed river with discs dominating (D50 = 30–95 mm) | Pebble counts | TLS | 2σ (0.05 m) | D50 = 0.73(2σ50) + 37.0 | 0.37 |

| Hodge et al. [22] | Tabular form and rounded edges (D50 = 18–63 mm) | Pebble counts | TLS | σd (1.0 m) | D50 = 1.42σd50 + 8.51 | 0.65 |

| Brasington et al. [20] | Schistose, cobble-sized grains (D50 = 30–117 mm) | Pebble counts | TLS | σd (1–2 m) | D50 = 2.59σd50 + 11.9 | 0.92 |

| Woodget and Austrums [25] | Cobbles and boulders (D84 = 10–160 mm) | Areal sample & Photosieving | SfM | RH (0.4 m) | D84 = 12.35RH50 − 2.90 | 0.80 |

| Vázquez-Tarrío et al. [24] | Well-rounded and subspherical grains (D50 = 28–65 mm) | Pebble counts | SfM | RH (1.0 m), 2σ (1.0 m) & σd (1.0 m) | D16 = 0.73RH16 + 7.26 | 0.64 |

| D50 = 0.89RH50 + 7.95 | 0.89 | |||||

| D84 = 0.78RH84 + 18.9 | 0.83 | |||||

| Pearson et al. [23] | Oblate (53%), prolate (24%), and sphere (23%) shaped particles. (D50 = 13–72 mm) | Areal sample | SfM | σ (0.2 m) & RH (0.5 m) | Poor sorting D50 = −0.29RH50 + 50.0 | 0.02 |

| Moderately well-sorted D50 = 1.85 RH50 + 22.0 | 0.69 | |||||

| Wong et al. [18] | Sands, gravels, and cobbles (D50 = 13–16 mm) | Photosieving | SfM | σ (0.03 m) RH (0.08 m) | D50 = 1.07RH50 + 11.6 | 0.42 |

| D84= 3.87RH50 + 13.7 | 0.49 |

| Set | Date | Reach | Surveyed Area (ha) | Point Cloud Density (pts/m2) | GSD (mm/px) | Georeferencing Errors (cm) | Sampling Sites |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 15 December 2021 | R1 | 0.77 | 2803.1 | 5.8 | 0.8 | H01 |

| 2 | 24 October 2022 | R1 | 4.20 | 2908.8 | 7.2 | 1.8 | H02, H03, H04, & H05 |

| 3 | 5 January 2023 | R2 | 1.58 | 4948.3 | 4.7 | 2.1 | H09 |

| 4 | 6 July 2023 | R1 | 4.50 | 4176.3 | 7.2 | 2.0 | H06, H7, &H 08 |

| 5 | 24 November 2023 | R3 | 2.37 | 3380.1 | 6.3 | 3.2 | N01 & N02 |

| 6 | 18 January 2024 | R4 | 7.75 | 2944.9 | 6.5 | 2.4 | L01 & L02 |

| 7 | 21 February 2024 | R2 | 2.64 | 3345.2 | 7.1 | 1.6 | H10 |

| Di-RHi | R2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| D16-RH16 | 0.79 | 2.32 | −46.67 |

| D25-RH25 | 0.92 | 3.41 | −73.90 |

| D50-RH50 | 0.94 | 5.71 | −142.58 |

| D75-RH75 | 0.70 | 9.45 | −265.02 |

| D84-RH84 | 0.60 | 15.99 | −605.11 |

| Sites | Reach R1 (%) | Mean (%) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Di | H01 | H02 | H03 | H04 | H05 | H06 | H07 | H08 | ||

| D16 | 21.2 | 15.0 | 20.8 | 115.0 | 85.5 | 36.0 | 362.0 | 79.6 | 91.9 | |

| D25 | 50.0 | 7.6 | 4.2 | 26.1 | 32.8 | 39.1 | 52.4 | 72.1 | 35.6 | |

| D50 | 32.9 | 26.4 | 11.8 | 30.2 | 13.6 | 45.0 | 2.1 | 27.9 | 23.7 | |

| D75 | 31.4 | 0.1 | 0.6 | 20.2 | 27.8 | 22.9 | 16.2 | 4.2 | 15.4 | |

| D84 | 20.6 | 32.3 | 8.0 | 6.5 | 30.7 | 25.9 | 17.5 | 12.7 | 19.3 | |

| Mean | 31.2 | 16.3 | 9.1 | 39.6 | 38.1 | 33.8 | 90.0 | 39.3 | 37.2 | |

| Sites | Reach R2 (%) | Reach R3 (%) | Reach R4 (%) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Di | H09 | H10 | Mean | N01 | N02 | Mean | L01 | L02 | Mean | |

| D16 | 46.3 | 8.4 | 27.3 | 8.2 | 100.9 | 54.5 | 210.6 | 390.7 | 300.7 | |

| D25 | 31.9 | 20.8 | 26.3 | 25.4 | 21.5 | 23.4 | 2.9 | 171.6 | 87.2 | |

| D50 | 31.1 | 2.3 | 16.7 | 1.0 | 16.3 | 8.7 | 41.3 | 27.6 | 34.4 | |

| D75 | 4.8 | 4.6 | 4.7 | 28.5 | 23.5 | 26.0 | 21.1 | 49.1 | 35.1 | |

| D84 | 0.3 | 35.3 | 17.8 | 26.1 | 20.7 | 23.4 | 36.2 | 43.3 | 39.7 | |

| Mean | 22.9 | 14.3 | 18.6 | 17.8 | 36.6 | 27.2 | 62.4 | 136.4 | 99.4 | |

| Sites | Reach R2 (%) | Reach R3 (%) | Reach R4 (%) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Di | H09 | H10 | Mean | N01 | N02 | Mean | L01 | L02 | Mean | |

| D16 | 67.4 | 8.4 | 37.9 | 4.7 | 67.0 | 35.8 | 224.3 | 442.2 | 333.3 | |

| D25 | 21.5 | 13.1 | 17.3 | 10.1 | 55.3 | 32.7 | 30.5 | 249.6 | 140.0 | |

| D50 | 1.5 | 13.8 | 7.6 | 9.1 | 18.1 | 13.6 | 16.2 | 9.1 | 12.7 | |

| D75 | 22.0 | 31.4 | 26.7 | 56.7 | 2.1 | 29.4 | 1.1 | 36.2 | 18.6 | |

| D84 | 10.8 | 52.1 | 31.5 | 42.0 | 12.9 | 27.4 | 30.5 | 38.3 | 34.4 | |

| Mean | 24.6 | 23.8 | 24.2 | 24.5 | 31.1 | 27.8 | 60.5 | 155.1 | 107.8 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jan, C.-D.; Lai, T.-Y.; Lai, K.-C. Characterizing the Surface Grain Size Distribution in a Gravel-Bed River Using UAV Optical Imagery and SfM Photogrammetry. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3890. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17233890

Jan C-D, Lai T-Y, Lai K-C. Characterizing the Surface Grain Size Distribution in a Gravel-Bed River Using UAV Optical Imagery and SfM Photogrammetry. Remote Sensing. 2025; 17(23):3890. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17233890

Chicago/Turabian StyleJan, Chyan-Deng, Tung-Yang Lai, and Kuan-Chung Lai. 2025. "Characterizing the Surface Grain Size Distribution in a Gravel-Bed River Using UAV Optical Imagery and SfM Photogrammetry" Remote Sensing 17, no. 23: 3890. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17233890

APA StyleJan, C.-D., Lai, T.-Y., & Lai, K.-C. (2025). Characterizing the Surface Grain Size Distribution in a Gravel-Bed River Using UAV Optical Imagery and SfM Photogrammetry. Remote Sensing, 17(23), 3890. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17233890