Research on Forest Fire Smoke and Cloud Separation Method Based on Fisher Discriminant Analysis

Highlights

- The spectral responses of smoke and clouds vary significantly under different underlying surfaces. The study found that for dark underlying surfaces (vegetation and water), smoke and cloud spectra in the short-wave infrared show significant overall differences, while for bright underlying surfaces (soil), smoke and cloud spectra show the opposite trend from the near-infrared to the short-wave infrared.

- Based on the screening of sensitive bands and the distribution patterns of smoke and clouds in spectral space, the Fisher discriminant analysis was used to construct the FSCRI model, which is suitable for vegetation, soil, and water underlying surfaces, achieving high discrimination accuracy with just a few bands.

- The analysis of the spectral response differences in smoke and clouds under different underlying surfaces provides a theoretical basis for the construction of index models, thereby improving the accuracy of smoke and cloud discrimination.

- The FSCRI model can effectively suppress the interference of clouds on smoke identification, provide strong technical support for early warning of forest fires, and improve the overall effectiveness of fire monitoring systems.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Principles and Methods

2.1. Theoretical Basis of Remote Sensing Scattering for Smoke and Clouds

2.1.1. Smoke Aerosol

2.1.2. Cloud Aerosol

- (1)

- Water cloud remote sensing scattering mechanism

- (2)

- Ice cloud remote sensing scattering mechanism

2.1.3. Comparison of Scattering–Absorption Mechanisms for Smoke and Clouds in Remote Sensing

- In the visible spectrum, clouds exhibit weaker absorption but stronger scattering compared to smoke particles. The reflectance of clouds is primarily determined by their optical thickness—both water and ice clouds show increased reflectance with greater optical thickness [44]. In contrast, smoke reflectance increases with aerosol concentration. Because the radius of cloud particles is much larger than that of smoke particles, their scattering ability is much stronger than that of smoke. Additionally, smoke particles exhibit a strong absorption effect in the visible light band. In the visible light range, for thick clouds, the particle radius is large, and the clouds are relatively thick. Incident electromagnetic waves are largely unable to penetrate the entire cloud layer, with most of the energy being scattered or reflected. As a result, the reflectivity of thick clouds is much higher than that of smoke. Within the visible light band, the reflectance variation patterns of smoke and clouds are similar, as both increase with an increase in their respective thickness or concentration. Consequently, the reflectance of thinner clouds and smoke becomes difficult to distinguish, leading to confusion between the two.

- The short-wave infrared is a key spectral range for distinguishing smoke from clouds, with significant differences in their reflectance characteristics. Smoke particle radii are typically smaller than or close to the wavelength in this band, and their optical radiation is primarily Rayleigh and Mie scattering, resulting in a relatively weak overall scattering effect. Combined with strong absorption by components such as black carbon, smoke reflectance decreases significantly with increasing wavelength and remains generally low. Cloud particles are typically larger than the wavelength in this band, and radiation is primarily influenced by Mie scattering. Although their reflectance decreases with increasing wavelength, it can remain relatively high due to greater optical thickness. This effect is particularly pronounced in ice clouds, where multiple scattering by non-spherical particles helps maintain higher reflectance levels.

2.2. Research on Band Sensitivity Analysis Methods

2.2.1. Sensitive Bands for Smoke Concentration and Cloud Thickness

2.2.2. Sensitive Bands for Smoke and Cloud Detection

2.3. Research on Smoke and Cloud Identification Methods

2.3.1. Threshold Method

2.3.2. Spectral Index Method

2.3.3. Fisher Discriminant Analysis (FDA)

3. Study Area and Data Sources

3.1. Overview of the Study Area

- (1)

- New South Wales, Australia (28°~37°S, 141°~153°E)

- (2)

- Victoria, Australia (34°~39°S, 141°~150°E)

- (3)

- British Columbia, Canada (48°~60°N, 115°~140°W)

3.2. Data Source

3.2.1. Basis for Data Source Selection

3.2.2. Smoke and Cloud Sample Selection and Gradation Standards

- (1)

- Sample gradation standards

- (2)

- Sampling method

4. Spectral Characteristics and Band Sensitivity of Smoke and Clouds

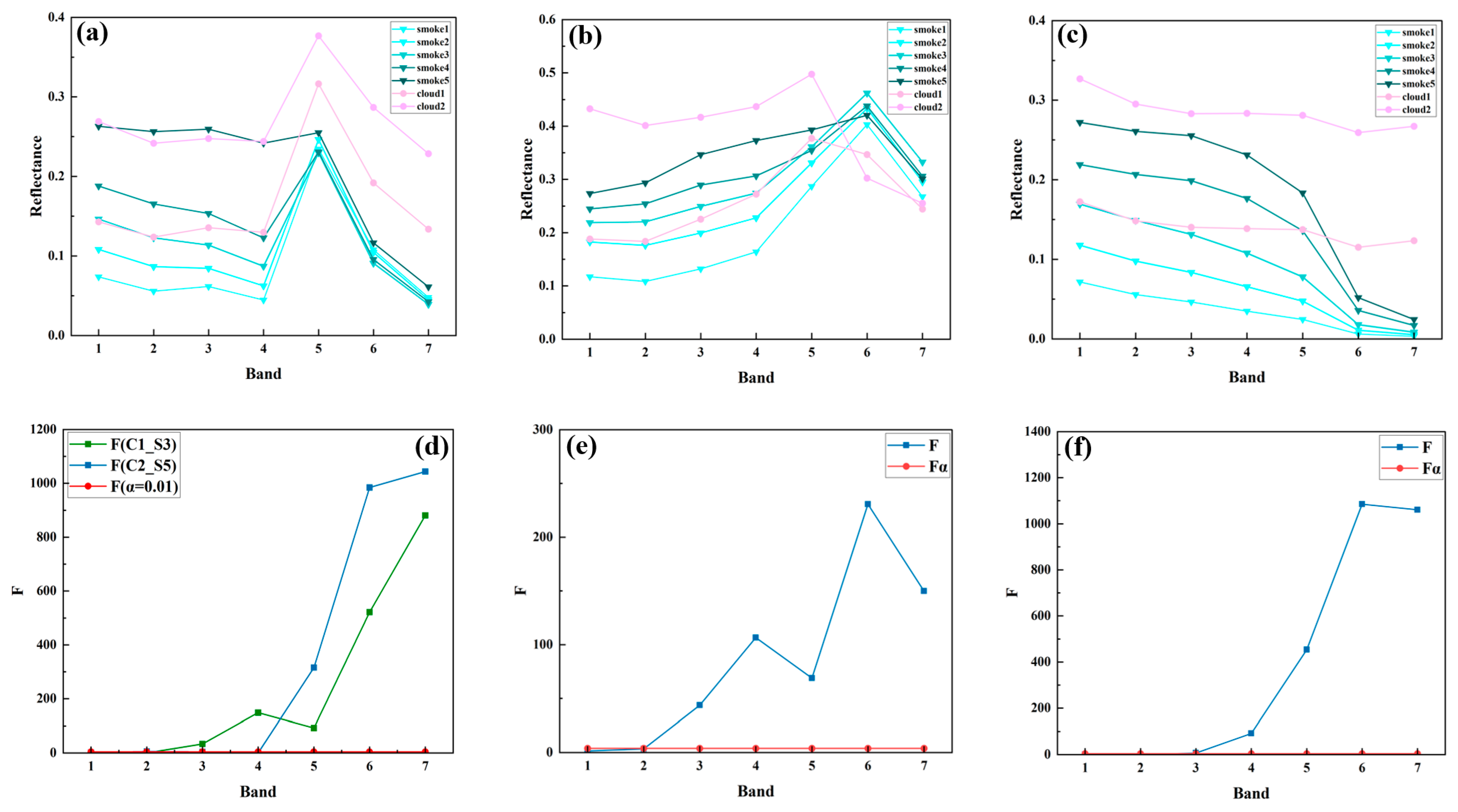

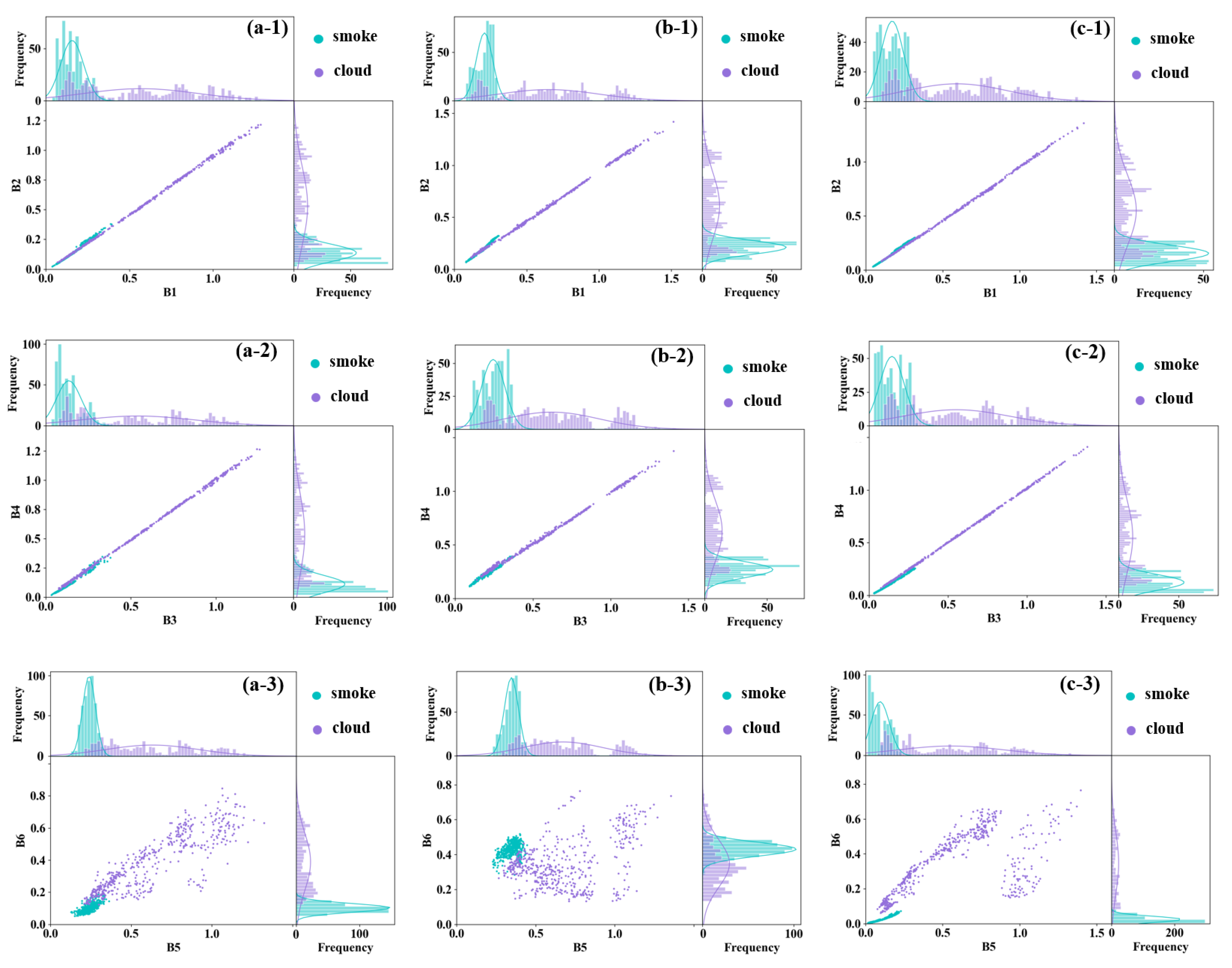

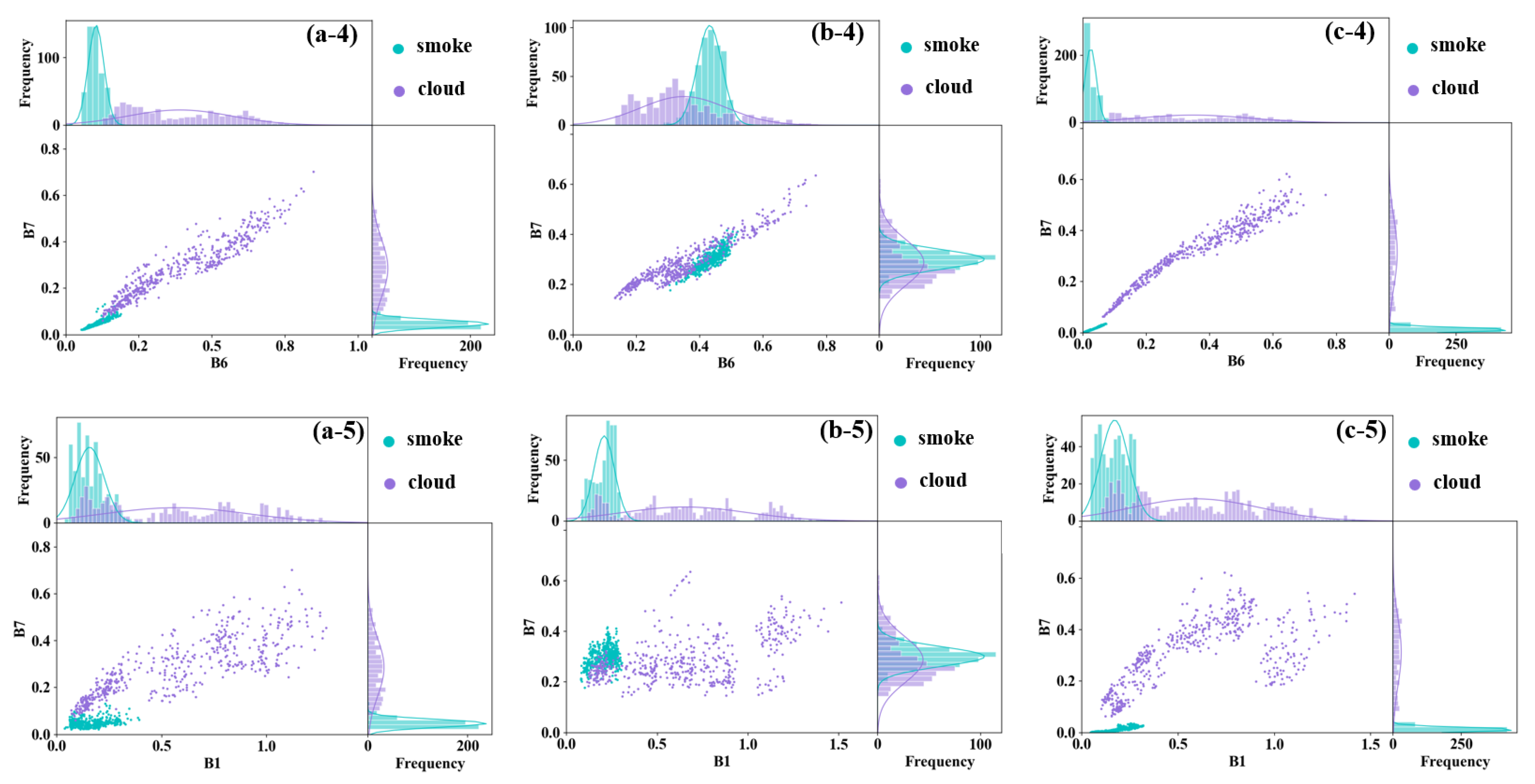

4.1. Spectral Characteristics of Smoke and Clouds

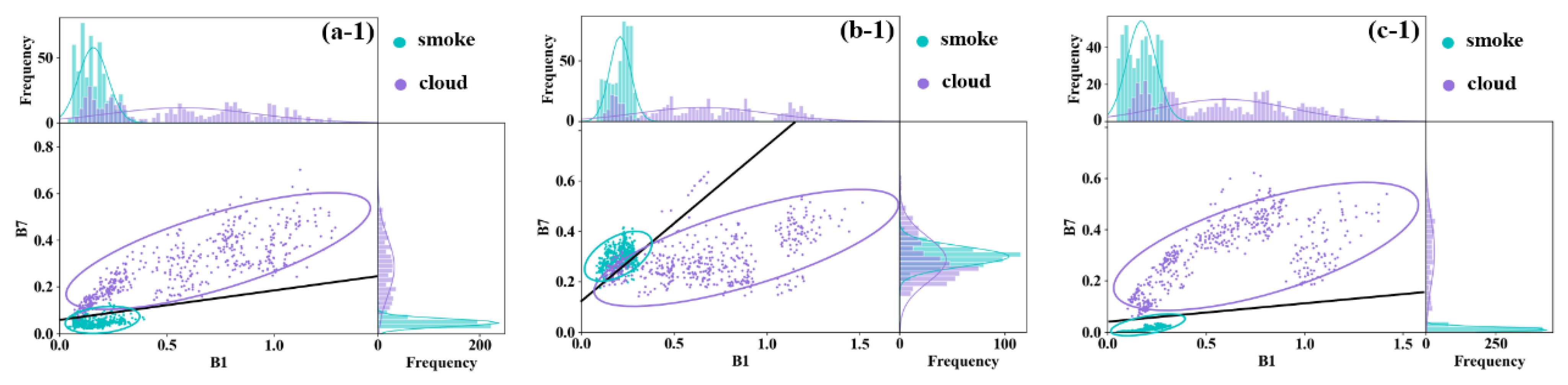

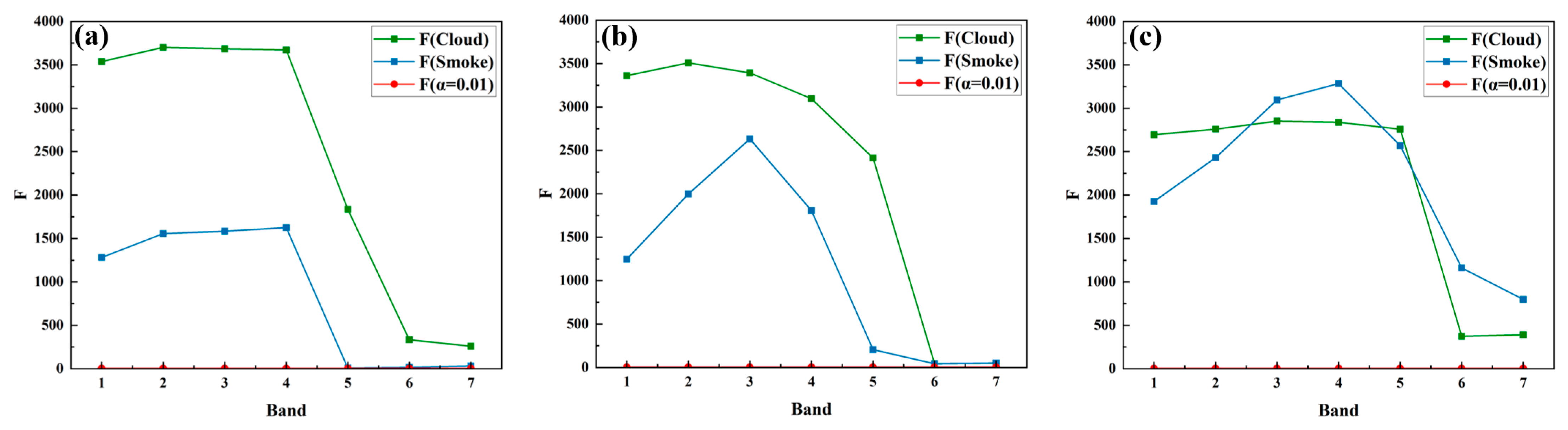

4.2. Overall Sensitivity Analysis of Smoke and Clouds over Different Underlying Surfaces

4.3. Sensitivity Analysis of Smoke and Clouds over the Same Underlying Surface

5. Construction and Verification of Smoke and Cloud Recognition Models

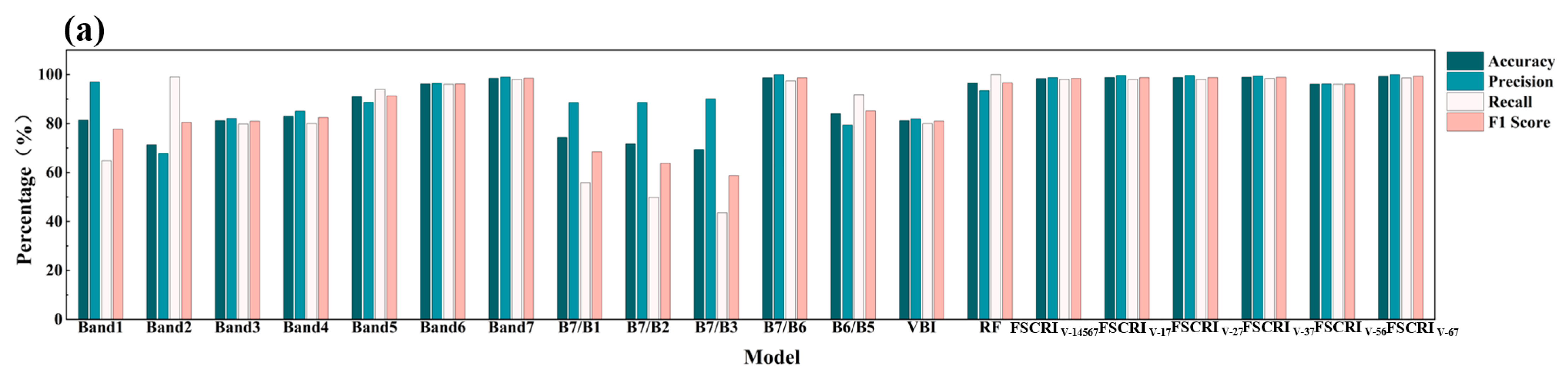

5.1. Single-Band Threshold Model

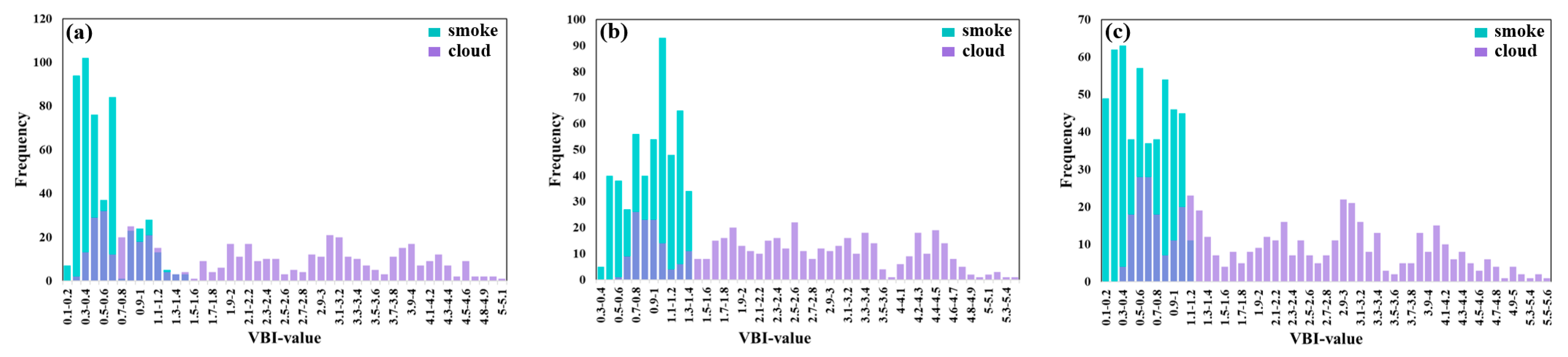

5.2. Visible-Band Index (VBI) Model

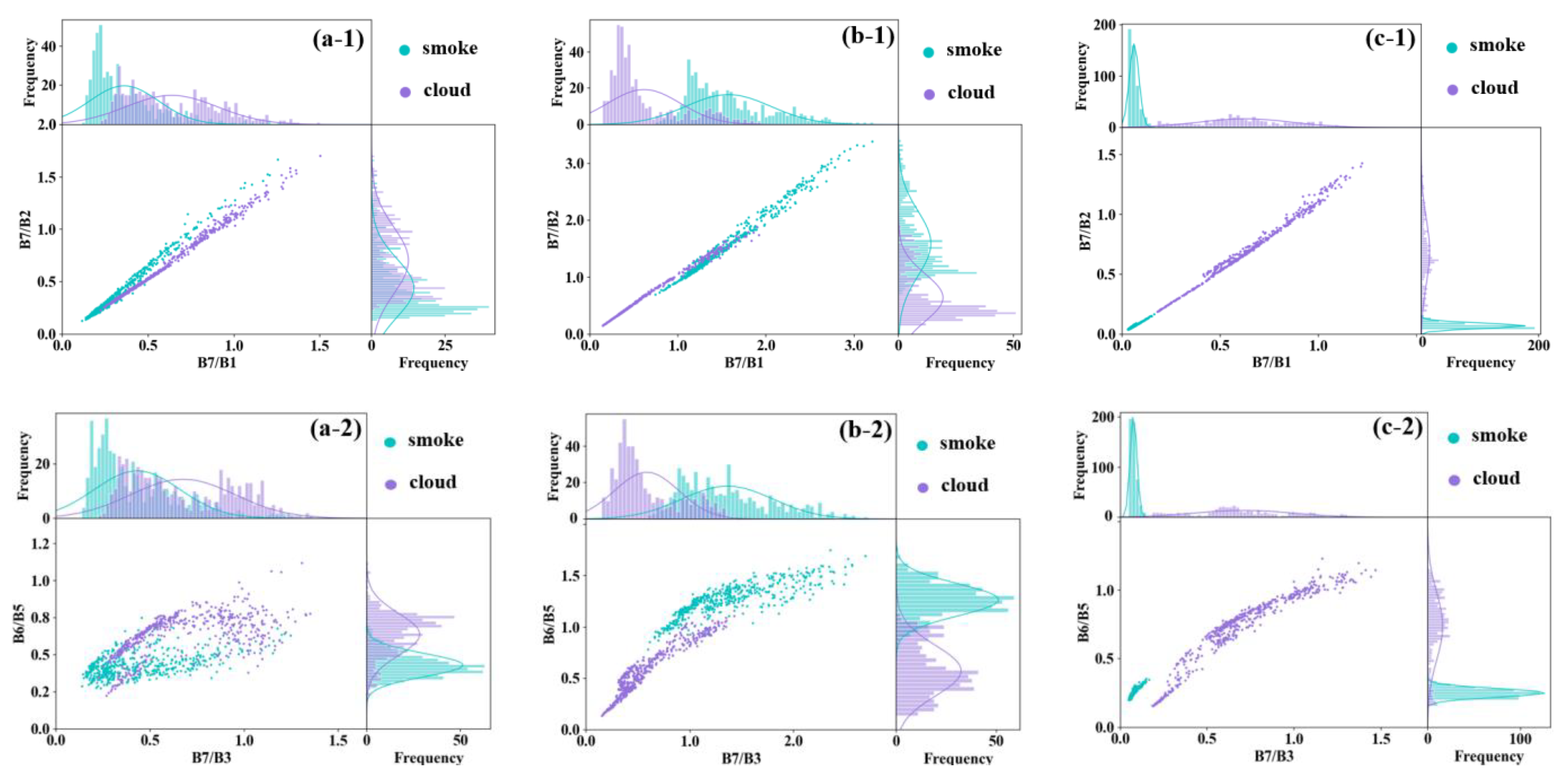

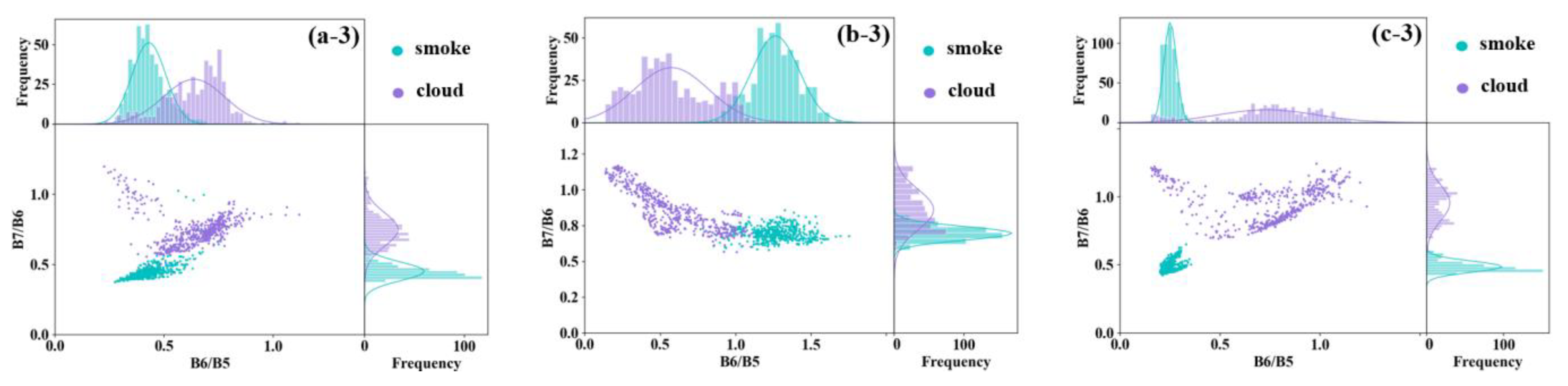

5.3. Ratio Index Model

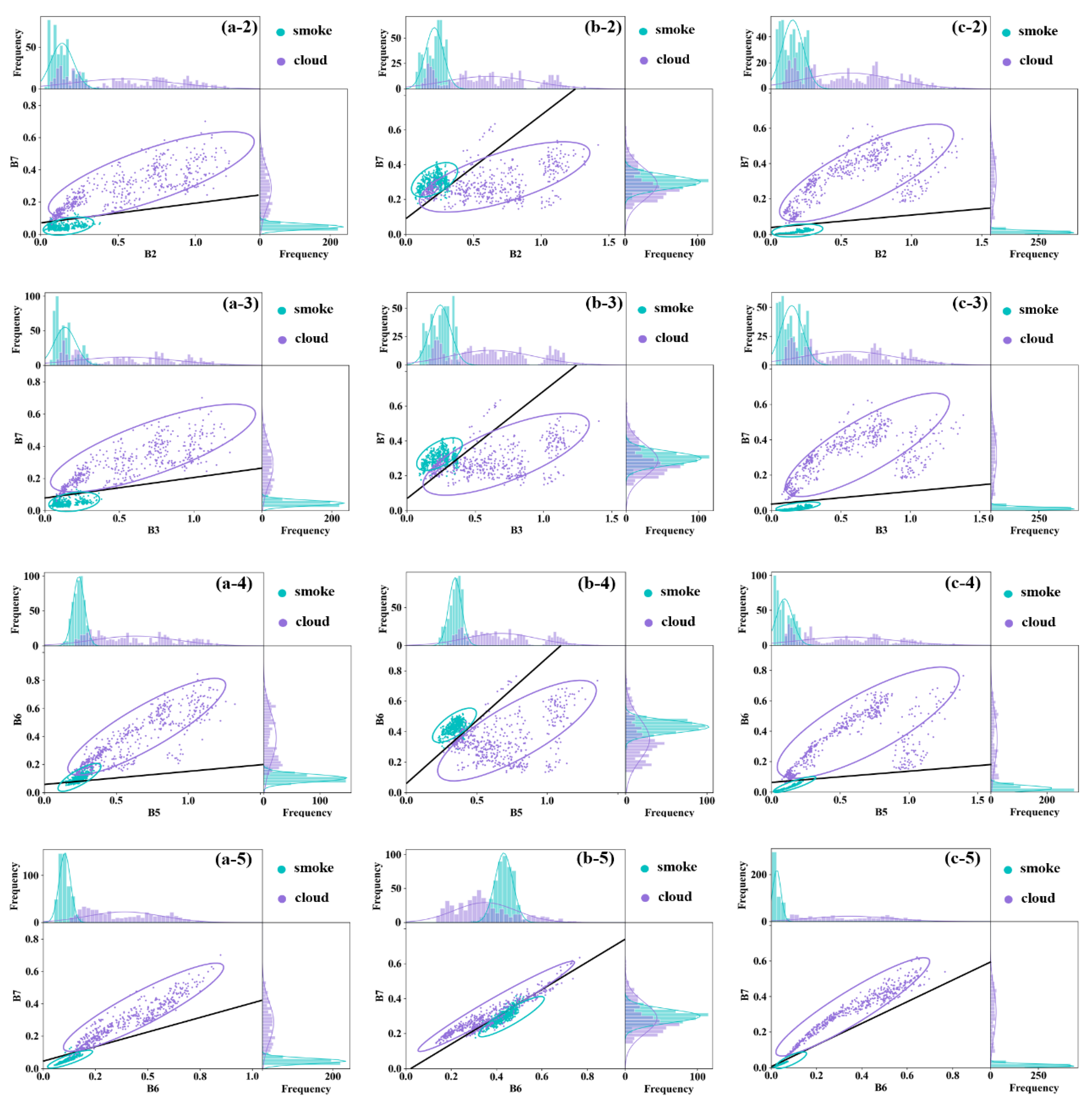

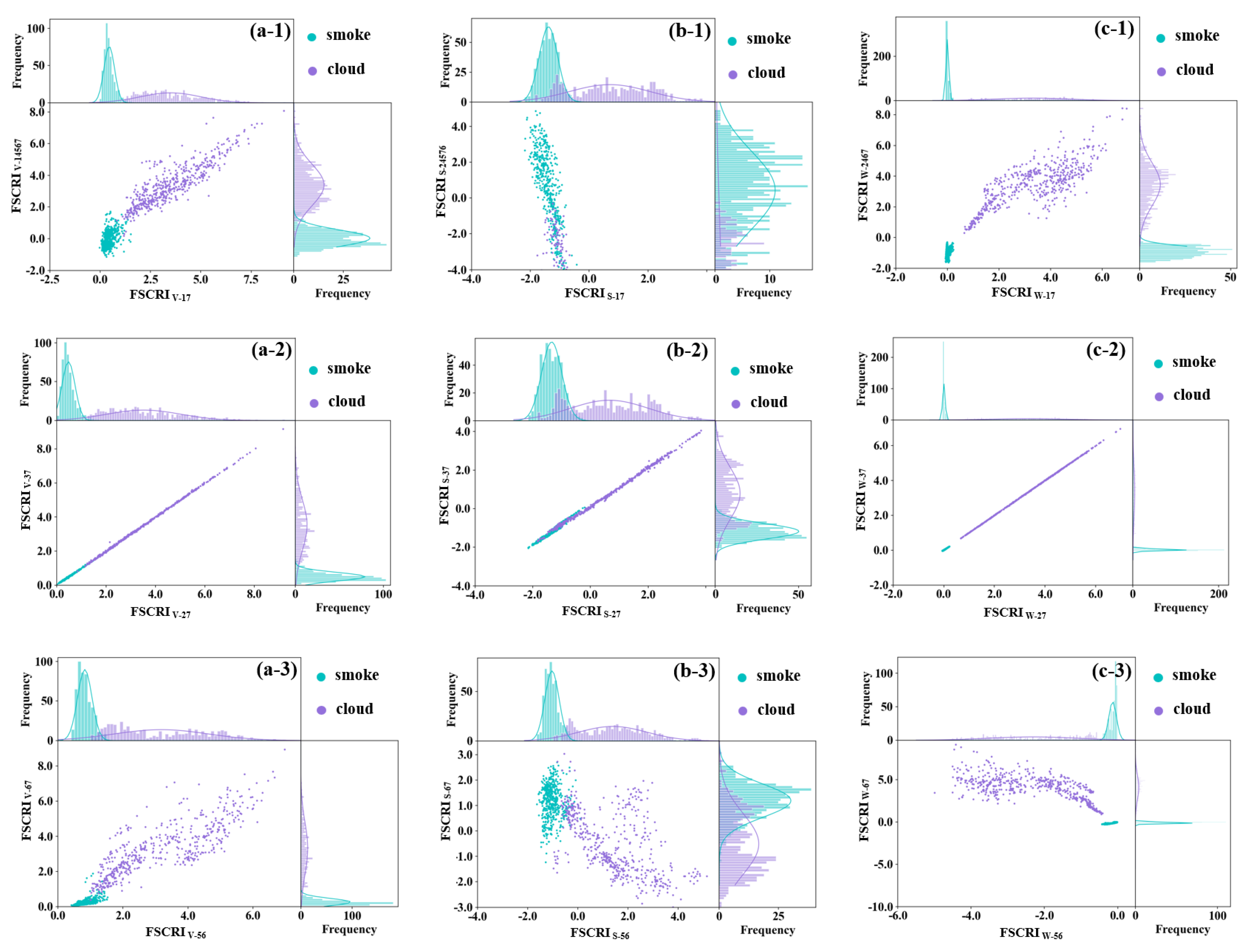

5.4. Fisher Smoke and Cloud Recognition Index (FSCRI) Model

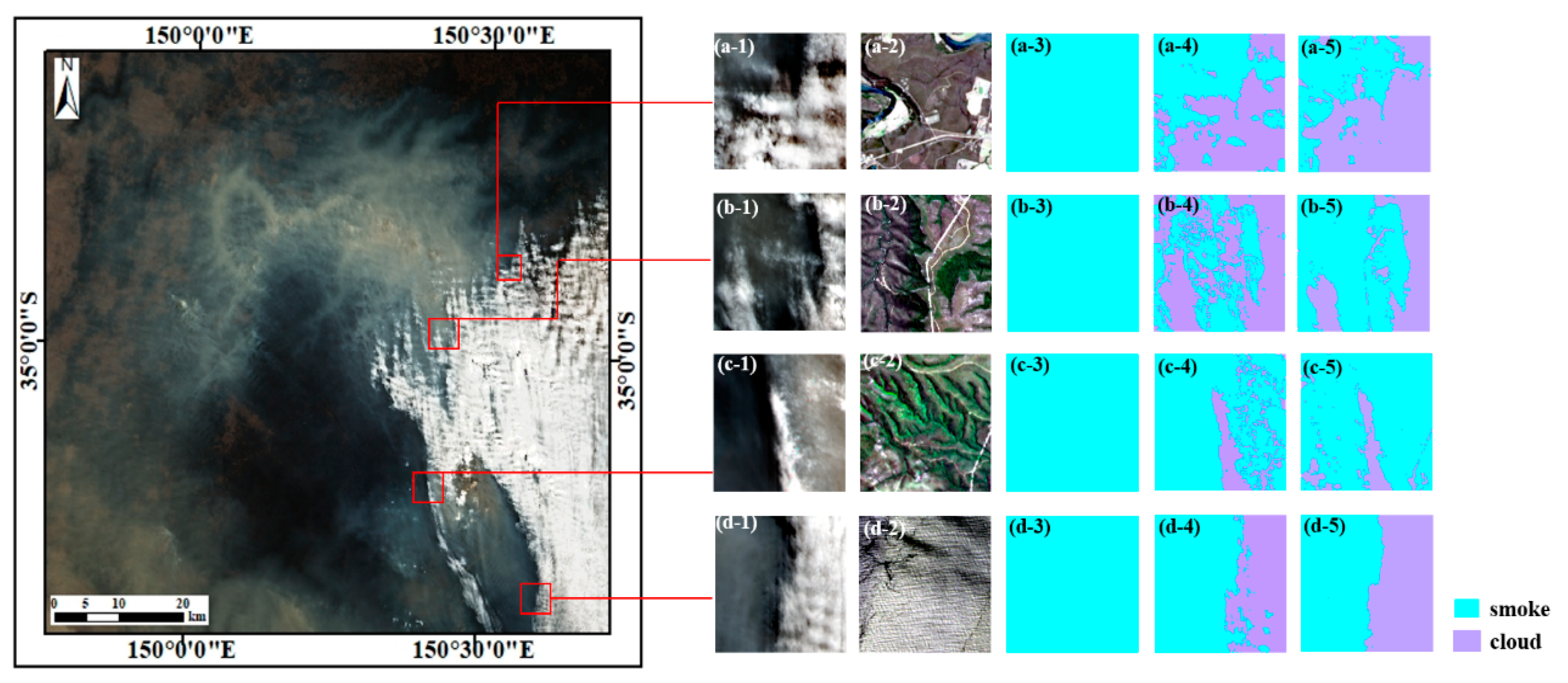

6. Case Study: Verification of Forest Fire Smoke Identification and Cloud Separation

7. Discussion

7.1. Correlation Analysis of Smoke and Cloud Scattering–Absorption Mechanisms with Multi-Spectral Responses

7.2. Impact of Underlying Surfaces on Spectral Characteristics and Identification Models of Smoke and Clouds

7.3. Model and Band Selection Strategies for Different Underlying Surfaces

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, S.; Li, W.; Cao, Y.; Lu, X. Combining the Convolution and Transformer for Classification of Smoke-Like Scenes in Remote Sensing Images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 4512519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barmpoutis, P.; Papaioannou, P.; Dimitropoulos, K.; Grammalidis, N. A Review on Early Forest Fire Detection Systems Using Optical Remote Sensing. Sensors 2020, 20, 6442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Yang, P.; Liang, H.; Zheng, C.; Yin, J.; Tian, Y.; Cui, W. Semantic Segmentation and Analysis on Sensitive Parameters of Forest Fire Smoke Using Smoke-Unet and Landsat-8 Imagery. Remote Sens. 2021, 14, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Zheng, C.; Liu, X.; Tian, Y.; Zhang, J.; Cui, W. Super-Resolution Reconstruction of Remote Sensing Data Based on Multiple Satellite Sources for Forest Fire Smoke Segmentation. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 4180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Cao, Y.; Feng, X.; Lu, X. Global2Salient: Self-Adaptive Feature Aggregation for Remote Sensing Smoke Detection. Neurocomputing 2021, 466, 202–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, S.; Shafiei, N.; Mehlitz, P. Smoke or Cloud: Real-Time Satellite Image Segmentation in a Wildfire Data Integration Application. Comput. Geosci. 2025, 204, 105960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, E.; Dube, T.; Mpakairi, K.S. Progress in the Remote Sensing of Veld Fire Occurrence and Detection: A Review. Afr. J. Ecol. 2023, 61, 541–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Hao, L.; Pan, J.; Jiang, L.; Song, J.; Xu, H.; Chen, X.; Wang, H. Remote Sensing of Optical Properties of Smoke Aerosols: Simulation Experiment and Application Based on Spaceborne Data. J. Appl. Remote Sens. 2022, 16, 044514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Jiang, L.; Pan, J.; Sheng, S.; Hao, L. A Satellite Imagery Smoke Detection Framework Based on the Mahalanobis Distance for Early Fire Identification and Positioning. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2023, 118, 103257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, Y.-S.; Le, H.V. Detection of Forest-Fire Smoke Plumes by Satellite Imagery. Atmos. Environ. (1967) 1984, 18, 2143–2151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagatani, I.; Kudoh, J.; Kawano, K. A New Technique for Visualization of Forest Fire Smoke Plumes Using MODIS Data. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium, Munich, Germany, 22–27 July 2012; pp. 2380–2383. [Google Scholar]

- Miao, S.; Lin, H.; Gao, H.; Dong, L. Strip Smoke and Cloud Recognition in Satellite Image. In Proceedings of the 2016 9th International Congress on Image and Signal Processing, BioMedical Engineering and Informatics (CISP-BMEI), Datong, China, 15–17 October 2016; pp. 303–307. [Google Scholar]

- Baum, B.A.; Trepte, Q. A Grouped Threshold Approach for Scene Identification in AVHRR Imagery. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 1999, 16, 793–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Alexander, K.; Cihlar, J. Automatic Detection of Fire Smoke Using Artificial Neural Networks and Threshold Approaches Applied to AVHRR Imagery. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2001, 39, 1859–1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrysoulakis, N.; Cartalis, C. A New Algorithm for the Detection of Plumes Caused by Industrial Accidents, Based on NOAA/AVHRR Imagery. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2003, 24, 3353–3368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.; Bai, M.; He, Z.; Fan, G.; Tang, M.; Liang, Z. A Technology of Forest Fire Smoke Detection Using Dual-Polarization Weather Radar. Forests 2025, 16, 1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Qu, J.J.; Xiong, X.; Hao, X.; Che, N.; Sommers, W. Smoke Plume Detection in the Eastern United States Using MODIS. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2007, 28, 2367–2374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del-Pozo-Velázquez, J.; Aguiar-Pérez, J.M.; Chamorro-Posada, P.; Pérez-Juárez, M.Á.; Wang, X.; Casaseca-de-la-Higuera, P. Smoke Detection in Images through Fractal Dimension-Based Binary Classification. Digit. Signal Process. 2025, 166, 105346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, D.; Zhang, F.; Yuan, D.; Hong, L.; Zheng, H.; Yang, F. Deep Learning-Based Forest Fire Risk Research on Monitoring and Early Warning Algorithms. Fire 2024, 7, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, L.A.O.; Ghali, R.; Akhloufi, M.A. YOLO-Based Models for Smoke and Wildfire Detection in Ground and Aerial Images. Fire 2024, 7, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Lu, Y.; Hu, C.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, M.; Jiao, J.; Xiong, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Z. Discrimination of Biomass-Burning Smoke From Clouds Over the Ocean Using MODIS Measurements. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 4102010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suo, Z.; Wang, Q.; Lu, Y.; Yao, Y.; Song, Q.; Ding, J.; Ju, W.; Zhang, Z. Satellite-Borne Identification and Quantification of Wildfire Smoke Emissions in North America via a Novel UV-Based Index. Atmos. Environ. 2025, 346, 121069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, J.; Song, W.; Ma, J.; Telesca, L.; Zhang, Y. Automatic Smoke Detection in MODIS Satellite Data Based on K-Means Clustering and Fisher Linear Discrimination. Photogramm. Eng. Remote Sens. 2014, 80, 971–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Song, W.; Lian, L.; Wei, X. Forest Fire Smoke Detection Using Back-Propagation Neural Network Based on MODIS Data. Remote Sens. 2015, 7, 4473–4498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; O’Sullivan, C.; Orlandi, F.; O’Sullivan, D.; Dev, S. Measurement of Industrial Smoke Plumes from Satellite Images. In Proceedings of the IGARSS 2023—2023 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium, Pasadena, CA, USA, 16–21 July 2023; pp. 5680–5683. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, K.; Pan, J.; Jiang, L.; Sun, Y.; Wang, K.; Cao, Y. Research on Remote Sensing Recognition of Forest Fire Smoke Based on Machine Learning. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Image Processing, Computer Vision and Machine Learning (ICICML), Xi’an, China, 28–30 October 2022; pp. 490–495. [Google Scholar]

- Cachier, H.; Liousse, C.; Buat-Menard, P.; Gaudichet, A. Particulate Content of Savanna Fire Emissions. J. Atmos. Chem. 1995, 22, 123–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budhavant, K.; Bikkina, S.; Andersson, A.; Asmi, E.; Backman, J.; Kesti, J.; Zahid, H.; Satheesh, S.K.; Gustafsson, Ö. Anthropogenic Fine Aerosols Dominate the Wintertime Regime over the Northern Indian Ocean. Tellus B Chem. Phys. Meteorol. 2018, 70, 1464871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, W.-H.; Sheng, X.-E.; Wang, S.; Deng, T. Experimental Study on Particle Size Distribution Characteristics of Aerosol for Fire Detection. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 5592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Q.; Zhang, H.; Wan, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Qiao, L. Characteristics of Light Scattering by Smoke Particles Based on Spheroid Models. J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transf. 2007, 107, 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, X.-M.; Fang, J.; Shao, Q.; Yuan, H.-Y.; Fan, W.-C. Fire Smoke Particle Size Measurement Based on the Multiwavelength and Multiangle Light Scattering Method. Chin. Phys. Lett. 2006, 23, 385–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radney, J.G.; Zangmeister, C.D. Comparing Aerosol Refractive Indices Retrieved from Full Distribution and Size- and Mass-Selected Measurements. J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transf. 2018, 220, 52–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.M.; Fiddler, M.N.; Sexton, K.G.; Bililign, S. Construction and Characterization of an Indoor Smog Chamber for Measuring the Optical and Physicochemical Properties of Aging Biomass Burning Aerosols. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 2019, 19, 467–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorchakov, G.I.; Karpov, A.V.; Pankratova, N.V.; Semoutnikova, E.G.; Vasiliev, A.V.; Gorchakova, I.A. Brown Carbon and Black Carbon in the Smoky Atmosphere during Boreal Forest Fires. Izv. Atmos. Ocean. Phys. 2017, 53, 875–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Shine, K.P. Studies of the Radiative Properties of Ice and Mixed-phase Clouds. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 1994, 120, 111–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Shang, H.; Letu, H.; Wei, L.; Chen, F.; Hong, J.; Wang, Z.; Chen, L. Impact of Orbital Characteristics and Viewing Geometry on the Retrieval of Cloud Properties From Multiangle Polarimetric Measurements. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 4107617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Hu, Y.; Stamnes, S.A.; Trepte, C.R.; Omar, A.H.; Baize, R.R. Effect of Partially Melting Droplets on Polarimetric and Bi-Spectral Retrieval of Water Cloud Particle Size. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez, C.; Ansmann, A.; Engelmann, R.; Donovan, D.; Malinka, A.; Schmidt, J.; Seifert, P.; Wandinger, U. The Dual-Field-of-View Polarization Lidar Technique: A New Concept in Monitoring Aerosol Effects in Liquid-Water Clouds—Theoretical Framework. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2020, 20, 15247–15263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baran, A.J. A Review of the Light Scattering Properties of Cirrus. J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transf. 2009, 110, 1239–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P.; Liou, K.-N.; Bi, L.; Liu, C.; Yi, B.; Baum, B.A. On the Radiative Properties of Ice Clouds: Light Scattering, Remote Sensing, and Radiation Parameterization. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 2015, 32, 32–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, B.A.; Yang, P.; Heymsfield, A.J.; Bansemer, A.; Cole, B.H.; Merrelli, A.; Schmitt, C.; Wang, C. Ice Cloud Single-Scattering Property Models with the Full Phase Matrix at Wavelengths from 0.2 to 100 µm. J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transf. 2014, 146, 123–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Diedenhoven, B.; Ackerman, A.S.; Fridlind, A.M.; Cairns, B.; Riedi, J. Global Statistics of Ice Microphysical and Optical Properties at Tops of Optically Thick Ice Clouds. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2020, 125, e2019JD031811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Letu, H.; Peng, Y.; Ishimoto, H.; Lin, Y.; Nakajima, T.Y.; Baran, A.J.; Guo, Z.; Lei, Y.; Shi, J. Investigation of Ice Cloud Modeling Capabilities for the Irregularly Shaped Voronoi Ice Scattering Models in Climate Simulations. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2022, 22, 4809–4825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Saito, M.; Yang, P.; Loeb, N.G.; Smith, W.L.; Minnis, P. On the Scattering-Angle Dependence of the Spectral Consistency of Ice Cloud Optical Thickness Retrievals Based on Geostationary Satellite Observations. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 4108012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terra, L.R.; Queiroz, S.C.N.; Terao, D.; Ferreira, M.M.C. Detection and Discrimination of Carica papaya Fungi through the Analysis of Volatile Metabolites by Gas Chromatography and Analysis of Variance-principal Component Analysis. J. Chemom. 2020, 34, e3244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeodato, P.; Melo, S. A Geometric Proof of the Equivalence between AUC_ROC and Gini Index Area Metrics for Binary Classifier Performance Assessment. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), Padua, Italy, 18–23 July 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, S.; Ma, Y.; Zou, H. Enhanced Youden’s Index with Net Benefit: A Feasible Approach for Optimal-threshold Determination in Shared Decision Making. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2020, 26, 551–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, A.; Cheng, Q.; Peng, H.; Altan, O.; Li, Y.; Ara, I.; Huq, E.; Ali, Y.; Saleem, N. Review of Spectral Indices for Urban Remote Sensing. Photogramm. Eng. Remote Sens. 2021, 87, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Tian, C.; Jin, G.; Han, K. Principal Component Analysis and Fisher Discriminant Analysis of Environmental and Ecological Quality, and the Impacts of Coal Mining in an Environmentally Sensitive Area. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2020, 192, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, F.; Khan, S.I.; Munawar, H.S.; Qadir, Z.; Qayyum, S. UAV Based Spatiotemporal Analysis of the 2019–2020 New South Wales Bushfires. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driscoll, D.A.; Macdonald, K.J.; Gibson, R.K.; Doherty, T.S.; Nimmo, D.G.; Nolan, R.H.; Ritchie, E.G.; Williamson, G.J.; Heard, G.W.; Tasker, E.M.; et al. Biodiversity Impacts of the 2019–2020 Australian Megafires. Nature 2024, 635, 898–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, S.; Niu, X.; Pan, J.; Jiang, L.; Sun, Y.; Wang, H.; Wang, K. Research on Smoke Relative Concentration Identification Method Based on Landsat8-OLI Multispectral Data and Multivariate Analysis. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2023, 44, 3550–3571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, S.; Liu, C.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Sohn, B.; Yung, Y.L. Retrieval of Ice-over-water Cloud Microphysical and Optical Properties Using Passive Radiometers. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2020, 47, e2020GL088941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Vegetation | Soil | Water | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level | Smoke | Smoke-free | Smoke | Smoke-free | Smoke | Smoke-free |

| 1 |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| 2 |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| 3 |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| 4 |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| 5 |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Vegetation | Soil | Water | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level | Cloud | Cloud-free | Cloud | Cloud-free | Cloud | Cloud-free |

| 1 |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| 2 |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| 3 |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| 4 |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| 5 |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Underlying Surfaces | Fisher Smoke and Cloud Recognition Index | Threshold (T) |

|---|---|---|

| Vegetation | FSCRIV-14567 = −18.621 × b1 − 13.948 × b4 + 6.780 × b5 − 15.566 × b6 + 28.874 × b7 | 1.2506 |

| FSCRIV-17 = −1.95 × b1 + 16.077 × b7 | 1.1821 | |

| FSCRIV-27 = −2.032 × b2 + 16.095 × b7 | 1.1912 | |

| FSCRIV-37 = −1.915 × b3 + 15.914 × b7 | 1.2434 | |

| FSCRIV-56 = −0.17 × b5 + 8.434 × b6 | 1.2812 | |

| FSCRIV-67 = −7.503 × b6 + 21.779 × b7 | 0.8787 | |

| Soil | FSCRIS-24567 = −6.479 × b2 − 11.065 × b4 + 25.226 × b5 − 19.043 × b6 + 17.534 × b7 | −4.208 |

| FSCRIS-17 = 4.477 × b1 − 7.693 × b7 | −0.9624 | |

| FSCRIS-27 = 4.741 × b2 − 7.792 × b7 | −0.7251 | |

| FSCRIS-37 = 4.961 × b3 − 7.943 × b7 | −0.56 | |

| FSCRIS-56 = 5.699 × b5 − 6.94 × b6 | −0.4750 | |

| FSCRIS-67 = 25.757 × b6 − 32.996 × b7 | 0.608 | |

| Water | FSCRIW-2467 = −22.572 × b2 + 21.358 × b4 − 20.575 × b6 + 35.569 × b7 | 0.0043 |

| FSCRIW-17 = −0.823 × b1 + 12.13 × b7 | 0.4394 | |

| FSCRIW-27 = −0.879 × b2 + 12.157 × b7 | 0.4448 | |

| FSCRIW-37 = −0.875 × b3 + 12.152 × b7 | 0.4514 | |

| FSCRIW-56 = 0.47 × b5 − 7.387 × b6 | −0.4404 | |

| FSCRIW-67 = −21.695 × b6 + 37.114 × b7 | 0.4746 |

| Vegetation | Soil | Water | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actual Labels | Actual Labels | Actual Labels | |||||||

| Predicted Labels | Smoke | Cloud | Total | Smoke | Cloud | Total | Smoke | Cloud | Total |

| Smoke | 98 | 7 | 105 | 98 | 11 | 109 | 100 | 2 | 102 |

| Cloud | 2 | 93 | 95 | 2 | 89 | 91 | 0 | 98 | 98 |

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, J.; Pan, J.; Sun, Y.; Jiang, L.; Liu, K. Research on Forest Fire Smoke and Cloud Separation Method Based on Fisher Discriminant Analysis. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3880. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17233880

Zhang J, Pan J, Sun Y, Jiang L, Liu K. Research on Forest Fire Smoke and Cloud Separation Method Based on Fisher Discriminant Analysis. Remote Sensing. 2025; 17(23):3880. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17233880

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Jiayi, Jun Pan, Yehan Sun, Lijun Jiang, and Kaifeng Liu. 2025. "Research on Forest Fire Smoke and Cloud Separation Method Based on Fisher Discriminant Analysis" Remote Sensing 17, no. 23: 3880. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17233880

APA StyleZhang, J., Pan, J., Sun, Y., Jiang, L., & Liu, K. (2025). Research on Forest Fire Smoke and Cloud Separation Method Based on Fisher Discriminant Analysis. Remote Sensing, 17(23), 3880. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17233880