Efficiency of Data Clustering for Stratification and Sampling in the Two-Phase ALS-Enhanced Forest Stock Inventory

Highlights

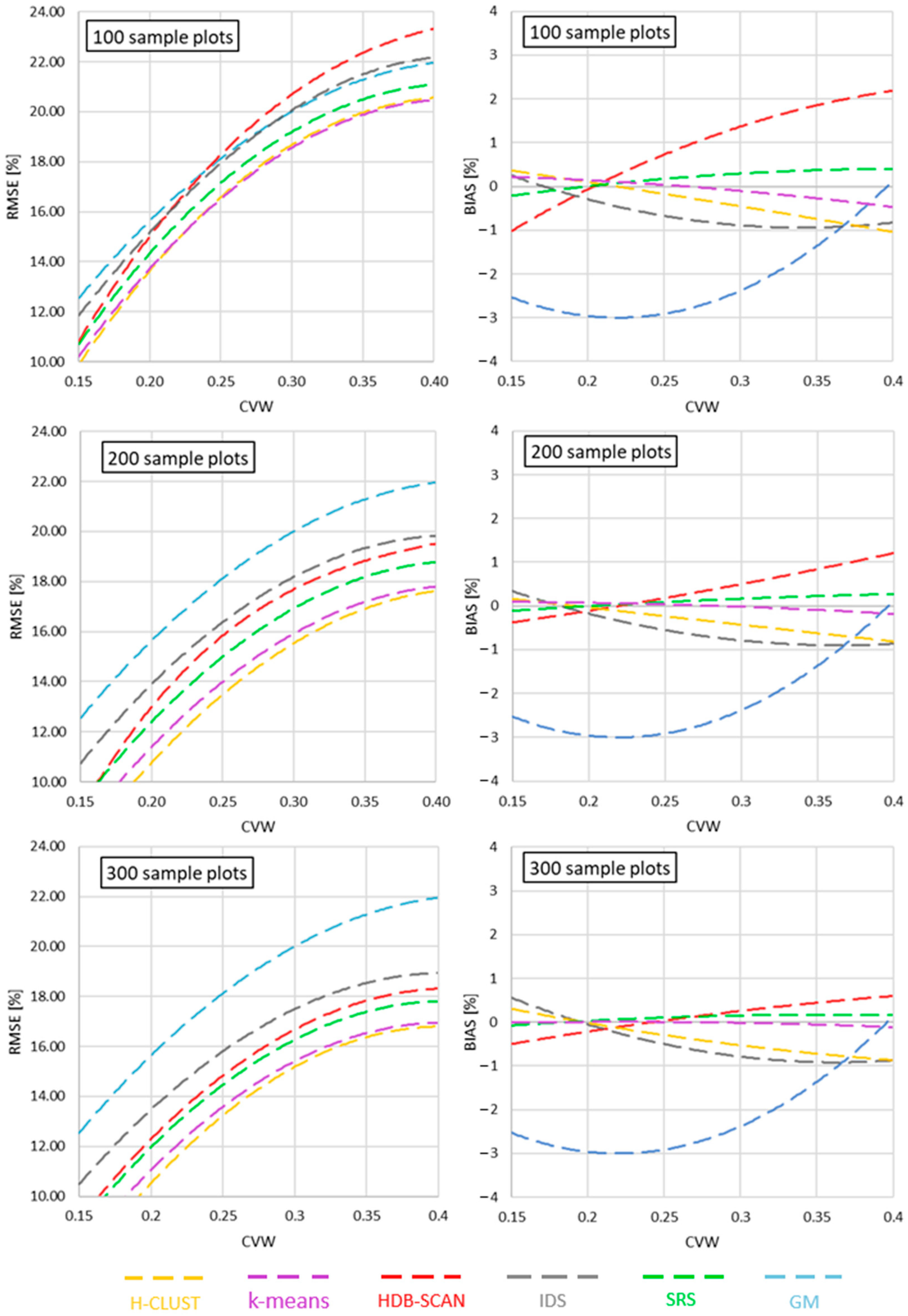

- Ward’s clustering was advantageous over other data clustering methods.

- Inconsiderable reduction in RMSE observed above around 200 sample plots.

- Complex stands benefit more from increased sample size than homogeneous ones.

- Data clustering methods can aid more optimal forest inventory stratification.

- Structurally guided sampling can be effectively performed with the data clustering.

Abstract

1. Introduction

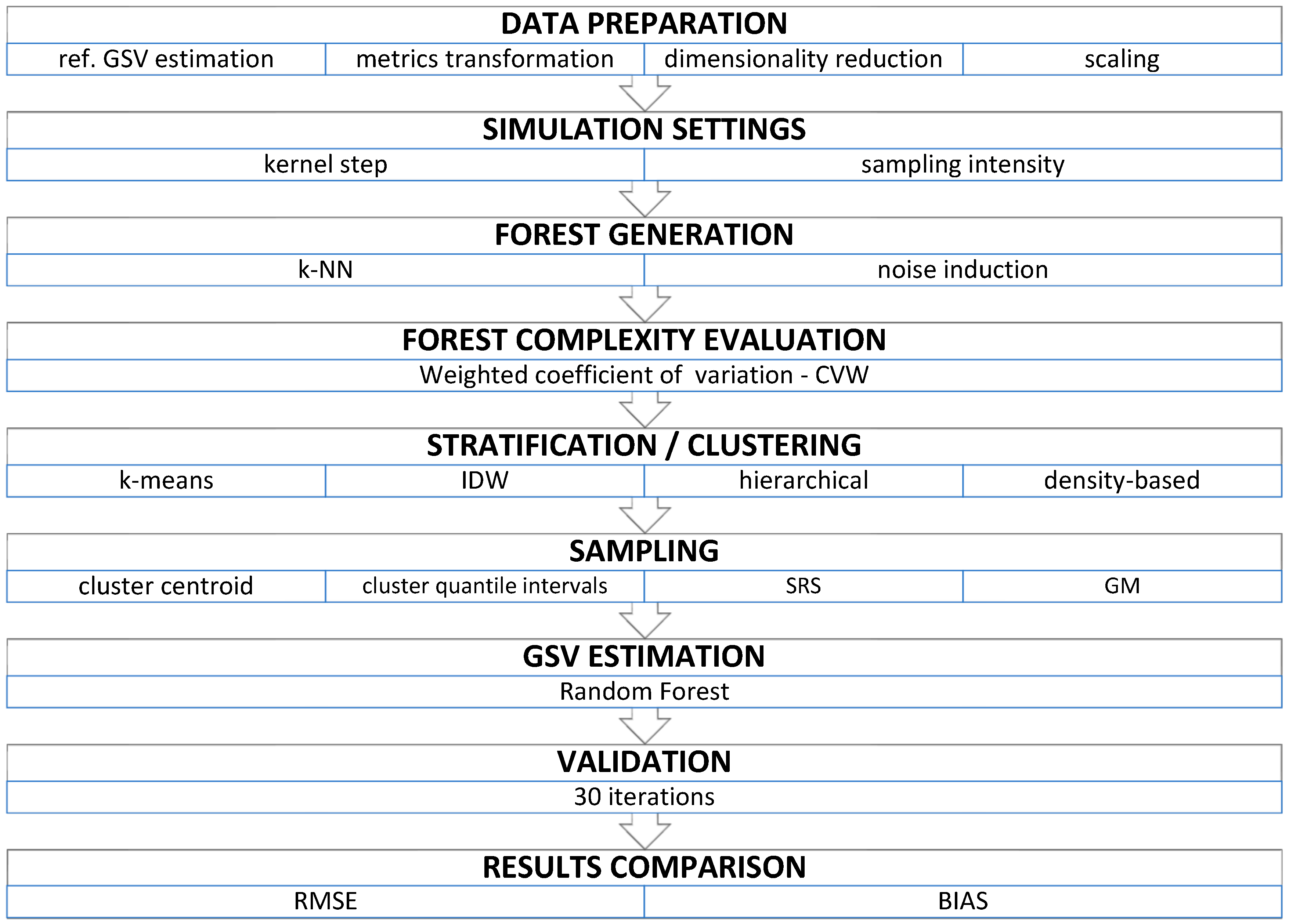

2. Methods

2.1. Input Data

2.2. Forest Generation

2.3. Clustering/Stratification and Sampling

2.4. GSV Estimation and Validation

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Næsset, E. Geographical information systems in long-term forest management and planning with special reference to preservation of biological diversity: A review. For. Ecol. Manag. 1997, 93, 121–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurteau, M.D. The role of forests in the carbon cycle and in climate change. In Climate Change, 3rd ed.; Letcher, T.M., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 561–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochmalová, M.; Purwestri, R.C.; Yongfeng, J.; Jarský, V.; Riedl, M.; Yuanyong, D.; Hájek, M. Demand for forest ecosystem services: A comparison study in selected areas in the Czech Republic and China. Eur. J. For. Res. 2022, 141, 867–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, F.; Bruijnzeel, L.A.; Meli, P.; Martin, P.A.; Zhang, J.; Nakagawa, S.; Miao, X.; Wang, W.; McEvoy, C.; Peña-Arancibia, J.L.; et al. The biodiversity and ecosystem service contributions and trade-offs of forest restoration approaches. Science 2022, 376, 839–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banaś, J.; Janeczko, E.; Zięba, S.; Utnik-Banaś, K.; Janeczko, K. Which forest type do visitors find most attractive? Integrating management activities with the recreational attractiveness of forests at a landscape level. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2025, 259, 105367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daryaei, A.; Trailovic, Z.; Sohrabi, H.; Atzberger, C.; Hochbichler, E.; Immitzer, M. Optimal integration of forest inventory data and aerial image-based canopy height models for forest stand management. For. Ecosyst. 2025, 13, 100299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulverhill, C.; Coops, N.C.; White, J.C.; Tompalski, P.; Achim, A. Evaluating the potential for continuous update of enhanced forest inventory attributes using optical satellite data. Forestry 2025, 98, 253–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, L.; Lynam, A.; Bradshaw, C.; He, F.; Bickford, D.; Woodruff, D.; Bumrungsri, S.; Laurance, W. Near-Complete Extinction of Native Small Mammal Fauna 25 Years After Forest Fragmentation. Science 2013, 341, 1508–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, N.; Brudvig, L.; Clobert, J.; Davies, K.; Gonzalez, A.; Holt, R.; Lovejoy, T.; Sexton, J.; Austin, M.; Collins, C.; et al. Habitat fragmentation and its lasting impact on Earth ecosystems. Sci. Adv. 2015, 1, e1500052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO; UNEP. The State of the World’s Forests 2020. Forests, Biodiversity and People; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations & United Nations Environment Programme: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNFCCC. United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change; Secretariat of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change: Bonn, Germany, 1992; p. 24. [Google Scholar]

- Mohren, G.M.J.; Hasenauer, H.; Köhl, M.; Nabuurs, G.-J. Forest inventories for carbon change assessments. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2012, 4, 686–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Climate Change and Land: An IPCC Special Report on Climate Change, Desertification, Land Degradation, Sustainable Land Management, Food Security, and Greenhouse Gas Fluxes in Terrestrial Ecosystems; Shukla, P.R., Skea, J., Calvo Buendia, E., Masson-Delmotte, V., Pörtner, H.-O., Roberts, D.C., Zhai, P., Slade, R., Connors, S., van Diemen, R., et al., Eds.; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sandker, M.; Carrillo, O.; Leng, C.; Lee, D.; d’Annunzio, R.; Fox, J. The Importance of High–Quality Data for REDD+ Monitoring and Reporting. Forests 2021, 12, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, E.S.; Coulston, J.W.; Domke, G.M.; Finley, A.O.; Green, E.J.; Stovall, A.E.L.; Woodall, C.W. Leveraging National Forest Inventory Data to Estimate Forest Carbon Density Status and Trends for Small Areas. Environ. Res. Lett. 2025, 20, 104001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinn, C. New technologies and methodologies for national forest inventories. Forstwiss. Cent. 2002, 53, 10–15. [Google Scholar]

- Kangas, A.; Astrup, R.; Breidenbach, J.; Fridman, J.; Gobakken, T.; Korhonen, K.T.; Maltamo, M.; Nilsson, M.; Nord-Larsen, T.; Næsset, E.; et al. Remote sensing and forest inventories in Nordic countries–roadmap for the future. Scand. J. For. Res. 2018, 33, 397–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luigui, A.; Renaud, J.-P.; Vega, C. How reliable are remote sensing maps calibrated over large areas? A matter of scale? arXiv 2024, arXiv:2408.03953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freese, F. Elementary Forest Sampling; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Handbook No. 232; Southern Forest Experiment Station: New Orleans, LA, USA, 1962.

- Chojnacky, D.C. Double Sampling for Stratification: A Forest Inventory Application in the Interior West; USDA Forest Service Research Paper RMRS-RP-7; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station: Fort Collins, CO, USA, 1998.

- Junttila, V.; Finley, A.O.; Bradford, J.B.; Kauranne, T. Strategies for minimizing sample size for use in airborne LiDAR-Based forest inventory. For. Ecol. Manag. 2013, 292, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mello, J.; Scolforo, H.; Raimundo, M.; Scolforo, J.; Oliveira, A.; Ferraz Filho, A. Estimating precision of systematic sampling in forest inventories. Ciênc. Agrotec. 2015, 39, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnussen, S.; McRoberts, R.E.; Breidenbach, J.; Nord-Larsen, T.; Ståhl, G.; Fehrmann, L.; Schnell, S. Comparison of estimators of variance for forest inventories with systematic sampling-results from artificial populations. For. Ecosyst. 2020, 7, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finley, A.O.; Doser, J.W. Introduction to Forestry Data Analysis with R; Chapman & Hall/CRC: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- West, P. Tree and Forest Measurement; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herries, D. Forest Inventory Sampling Designs for Plot/Sample Locations. Interpine Blog. 26 March 2014. Available online: https://interpine.nz/forest-inventory-sampling-designs-for-plotsample-locations/ (accessed on 3 August 2025).

- Räty, M.; Kuronen, M.; Myllymäki, M.; Kangas, A.; Mäkisara, K.; Heikkinen, J. Comparison of the local pivotal method and systematic sampling for national forest inventories. For. Ecosyst. 2020, 7, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, W.L.; White, G.C.; Gowan, C. Sampling Designs and Related Topics. In Monitoring Vertebrate Populations; Thompson, W.L., White, G.C., Gowan, C., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1998; pp. 43–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafa, S.; Ahmad, I. Recent Developments in Systematic Sampling: A Review. J. Stat. Theory Pract. 2017, 12, 290–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babcock, C.; Finley, A.O.; Gregoire, T.G.; Andersen, H.-E. Remote sensing to reduce the effects of spatial autocorrelation on design-based inference for forest inventory using systematic samples. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1810.08588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffith, D.A.; Plant, R.E. Statistical Analysis in the Presence of Spatial Autocorrelation: Selected Sampling Strategy Effects. Stats 2022, 5, 1334–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, L. Systematic Sampling: A Step-by-Step Guide with Examples. Scribbr. 2023. Available online: https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/systematic-sampling/ (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- Ahmed, S.K. How to Choose a Sampling Technique and Determine Sample Size for Research: A simplified guide for researchers. Oral Oncol. Rep. 2024, 12, 100662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayaraman, K. Statistical Manual for Forestry Research; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific: Bangkok, Thailand, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- BDL-Bank Danych o Lasach. Instrukcja Wykonywania Wielkoobszarowej Inwentaryzacji Stanu Lasu; PGL Lasy Państwowe: Warsaw, Poland, 2014. Available online: https://www.bdl.lasy.gov.pl/portal/Media/Default/Publikacje/Instrukcja%20WISL_2015.pdf (accessed on 16 August 2025).

- SLU—Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Department of Forest Research Management. About NFI. 2025. Available online: https://www.slu.se/en/about-slu/organisation/departments/forest-resource-management/miljoanalys/nfi/about-nfi/inventory-design (accessed on 4 September 2025).

- Mehtätalo, L.; Räty, M.; Mehtätalo, J. A new growth curve and fit to the National Forest Inventory data of Finland. Ecol. Model. 2025, 501, 111006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bindewald, A.; Miocic, S.; Wedler, A.; Bauhus, J. Forest inventory-based assessments of the invasion risk of Pseudotsuga menziesii (Mirb.) Franco and Quercus rubra L. in Germany. Eur. J. For. Res. 2021, 140, 883–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simons, N.K.; Felipe-Lucia, M.R.; Schall, P.; Ammer, C.; Bauhus, J.; Blüthgen, N.; Boch, S.; Buscot, F.; Fischer, M.; Goldmann, K.; et al. National Forest Inventories capture the multifunctionality of managed forests in Germany. For. Ecosyst. 2021, 8, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bechtold, W.A.; Scott, C.T. The Forest Inventory and Analysis Plot Design. In The Enhanced Forest Inventory and Analysis Program—National Sampling Design and Estimation Procedures; Bechtold, W.A., Patterson, P.L., Eds.; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Southern Research Station: Asheville, NC, USA, 2005; pp. 27–42. [Google Scholar]

- Bontemps, J.-D.; Bouriaud, O. Take five: About the beat and the bar of annual and 5-year periodic national forest inventories. Ann. For. Sci. 2024, 81, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochran, W.G. Sampling Techniques, 3rd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, J. Sampling. In International Encyclopedia of Education, 3rd ed.; Peterson, P., Baker, E., McGaw, B., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010; pp. 390–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Räty, M.; Heikkinen, J.; Korhonen, K.T.; Peräsaari, J.; Ihalainen, A.; Pitkänen, J.; Kangas, A.S. Effect of cluster configuration and auxiliary variables on the efficiency of local pivotal method for national forest inventory. Scand. J. For. Res. 2019, 34, 607–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lister, A.J.; Leites, L.P. Cost implications of cluster plot design choices for precise estimation of forest attributes in landscapes and forests of varying heterogeneity. Can. J. For. Res. 2022, 52, 188–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokola, T.; Shrestha, S.M. Comparison of cluster-sampling techniques for forest inventory in southern Nepal. For. Ecol. Manag. 1999, 116, 219–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grafström, A.; Zhao, X.; Nylander, M.; Petersson, H. A new sampling strategy for forest inventories applied to the temporary clusters of the Swedish national forest inventory. Can. J. For. Res. 2017, 47, 1161–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulston, J. Forest Inventory and Stratified Estimation: A Cautionary Note; Res. Note SRS-16; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Southeastern Forest Experiment Station: Asheville, NC, USA, 2008. [CrossRef]

- OpenGenus IQ. Cluster Sampling. OpenGenus IQ. Available online: https://iq.opengenus.org/cluster-sampling/ (accessed on 22 August 2025).

- Lv, T.; Zhou, X.; Tao, Z.; Sun, X.; Wang, J.; Li, R.; Xie, F. Remote Sensing-Guided Spatial Sampling Strategy over Heterogeneous Surface Ground for Validation of Vegetation Indices Products with Medium and High Spatial Resolution. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 2674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Ma, L.; Wang, X.; Kim, Y.; Zhang, L. High-Precision population estimates by remote sensing big data and advanced transformer deep learning model. Remote Sens. Appl. Soc. Environ. 2025, 39, 101638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ene, L.T.; White, J.C.; Tompalski, P.; Maltamo, M.; Heiskanen, J.; Saarela, S.-R.; Packalen, P.; Kangas, A.; Tomppo, E. Simulation-Based assessment of sampling strategies for large-area biomass estimation using airborne laser scanning. Remote Sens. 2016, 8, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobakken, T.; Næsset, E.; Nelson, R.; Bollandsås, O.M.; Gregoire, T.G.; Ståhl, G.; Holm, S.; Ørka, H.O.; Astrup, R. Estimating biomass in Hedmark County, Norway using national forest inventory field plots and airborne laser scanning. Remote Sens. Environ. 2012, 123, 443–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papa, D.d.A.; Almeida, D.R.A.; Silva, C.A.; Figueiredo, E.O.; Stark, S.C.; Valbuena, R.; Rodriguez, L.C.E.; Oliveira, M.V.N. Evaluating tropical forest classification and field sampling stratification from lidar to reduce effort and enable landscape monitoring. For. Ecol. Manag. 2020, 457, 117634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisańczuk, M.; Mitelsztedt, K.; Parkitna, K.; Krok, G.; Stereńczak, K.; Wysocka-Fijorek, E.; Miścicki, S. Influence of sampling intensity on performance of two-phase forest inventory using airborne laser scanning. For. Ecosyst. 2020, 7, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, V.S.d.; Silva, C.A.; Mohan, M.; Cardil, A.; Rex, F.E.; Loureiro, G.H.; Almeida, D.R.A.d.; Broadbent, E.N.; Gorgens, E.B.; Dalla Corte, A.P.; et al. Combined Impact of Sample Size and Modeling Approaches for Predicting Stem Volume in Eucalyptus spp. Forest Plantations Using Field and LiDAR Data. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corona, P.; Fattorini, L.; Pagliarella, M.C. Sampling strategies for estimating forest cover from remote sensing-based two-stage inventories. For. Ecosyst. 2015, 2, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupuis, C.; Lejeune, P.; Michez, A.; Fayolle, A. How Can Remote Sensing Help Monitor Tropical Moist Forest Degradation?—A Systematic Review. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köhl, M.; Magnussen, S.; Marchetti, M. Sampling Methods, Remote Sensing and GIS Multiresource Forest Inventory; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Næsset, E. Predicting forest stand characteristics with airborne scanning laser using a practical two-stage procedure and field data. Remote Sens. Environ. 2002, 80, 88–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergseng, E.; Ørka, H.O.; Næsset, E.; Gobakken, T.; Ståhl, G.; Gregoire, T.; Solberg, B. Assessing forest inventory information obtained from different inventory approaches and remote sensing data sources. Ann. For. Sci. 2015, 72, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirici, G.; McRoberts, R.E.; Fattorini, L.; Mura, M.; Marchetti, M. Comparing echo-based and canopy height model-based metrics for enhancing estimation of forest aboveground biomass in a model-assisted framework. Remote Sens. Environ. 2016, 174, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dettmann, G.T.; Radtke, P.J.; Coulston, J.W.; Green, P.C.; Wilson, B.T.; Moisen, G.G. Review and Synthesis of Estimation Strategies to Meet Small Area Needs in Forest Inventory. Front. For. Glob. Change 2022, 5, 813569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyyppä, J.; Yu, X.; Hyyppä, H.; Vastaranta, M.; Holopainen, M.; Kukko, A.; Kaartinen, H.; Jaakkola, A.; Vaaja, M.; Koskinen, J.; et al. Advances in Forest Inventory Using Airborne Laser Scanning. Remote Sens. 2012, 4, 1190–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maltamo, M.; Packalén, P. Species specific management inventory in Finland. In Forestry Applications of Airborne Laser Scanning–Concepts and Case Studies; Maltamo, M., Næsset, E., Vauhkonen, J., Eds.; Managing Forest Ecosystems; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; Volume 27, pp. 241–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, J.; Coops, N.; Wulder, M.; Vastaranta, M.; Hilker, T.; Tompalski, P. Remote Sensing Technologies for Enhancing Forest Inventories: A Review. Can. J. Remote Sens. 2016, 42, 619–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, J.; Tompalski, P.; Vastaranta, M.; Wulder, M.; Saarinen, N.; Stepper, C.; Coops, N. A Model Development and Application Guide for Generating an Enhanced Forest Inventory Using Airborne Laser Scanning Data and an Area-Based Approach, Canadian Forest Service, Canadian Wood Fibre Centre, Information, Report FI-X-018. 2017. Available online: https://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2018/rncan-nrcan/Fo148-1-18-eng.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- White, J.; Penner, M.; Woods, M. Assessing single photon LiDAR for operational implementation of an enhanced forest inventory in diverse mixedwood forests. For. Chron. 2021, 97, 78–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fassnacht, F.E.; White, J.C.; Wulder, M.A.; Næsset, E. Remote sensing in forestry: Current challenges, considerations and directions. Forestry 2023, 97, 11–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IUL. Instrukcja Urządzania Lasu; Państwowe Gospodarstwo Leśne Lasy Państwowe: Warszawa, Poland, 2024. Available online: https://www.lasy.gov.pl/pl/publikacje/copy_of_gospodarka-lesna/urzadzanie/iul/instrukcja-urzadzenia-lasu-2024/instrukcja-urzadzania-lasu-czesc-i.pdf/view (accessed on 8 September 2025).

- Næsset, E.; Bjerknes, K.-O. Estimating tree heights and number of stems in young forests using airborne laser scanner data. Remote Sens. Environ. 2001, 78, 328–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Næsset, E.; Gobakken, T.; Holmgren, J.; Hyyppä, H.; Hyyppä, J.; Maltamo, M.; Nilsson, M.; Olsson, H.; Persson, Å.; Derman, U. Laser scanning of forest resources: The Nordic experience. Scand. J. For. Res. 2004, 18, 482–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stauffer, H.B. A Sample Size Table for Forest Sampling. For. Sci. 1982, 28, 777–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musa, S.; Kassim, A.R.; Yusoff, S.M.; Ibrahim, S. Assessing the status of logged-over production forests: The development of a rapid appraisal technique. In Information and Analysis for Sustainable Forest Management: Linking National and International Efforts in South and Southeast Asia; EC-FAO Partnership Programme 2000–2002, Tropical Forestry Budget Line B7-6201/1B/98/0531, Project GCP/RAS/173/EC; FAO: Bangkok, Thailand, 2003; Available online: https://www.fao.org/4/ac838e/AC838E12.htm#7818 (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Reams, G.; Smith, W.D.; Hansen, M.H.; Bechtold, W.A.; Roesch, F.A.; Moisen, G.G. The Forest Inventory and Analysis Sampling Frame. In The Enhanced Forest Inventory and Analysis Program—National Sampling Design and Estimation Procedures; Gen. Tech. Rep. SRS-80; USDA Forest Service: Asheville, NC, USA, 2005; pp. 11–26. [Google Scholar]

- Avery, T.E.; Burkhart, H.E. Forest Measurements, 6th ed.; Waveland Press: Long Grove, IL, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Sanjerehei Mousaei, M. Sample Size Calculations for Vegetation Studies. Maced. J. Ecol. Environ. 2021, 23, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wulder, M.; White, J.; Nelson, R.; Næsset, E.; Ørka, H.; Coops, N.; Hilker, T.; Bater, C.; Gobakken, T. LiDAR sampling for large-area forest characterization: A review. Remote Sens. Environ. 2012, 121, 196–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grafström, A.; Saarela, S.; Ene, L.T. Efficient sampling strategies for forest inventories by spreading the sample in auxiliary space. Can. J. For. Res. 2014, 44, 1156–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Yu, Z.; Dai, H.; Zhou, X.; Zhou, M. Effect of sample size on the estimation of forest inventory attributes using airborne LiDAR data in large-scale subtropical areas. Ann. For. Sci. 2023, 80, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinn, C.; Fehrmann, L. Basic forest statistics–Accuracy, precision and bias [Unpublished presentation]. In Proceedings of the Regional Course on REDD+, MRV and Monitoring, Sokoine University of Agriculture, Morogoro, Tanzania, 11–15 July 2011; UN-REDD Programme: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Strimbu, B.M. Comparing the efficiency of intensity-based forest inventories with sampling-error-based forest inventories. Forestry 2014, 87, 249–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latifi, H.; Koch, B. Evaluation of most similar neighbour and random forest methods for imputing forest inventory variables using data from target and auxiliary stands. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2012, 33, 6668–6694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stereńczak, K.; Lisańczuk, M.; Parkitna, K.; Mitelsztedt, K.; Mroczek, P.; Miścicki, S. The influence of number and size of sample plots on modelling growing stock volume based on airborne laser scanning. Drewno 2018, 61, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido de Lera, A.; Gobakken, T.; Ørka, H.; Næsset, E.; Bollandsås, O. Estimating forest attributes in airborne laser scanning based inventory using calibrated predictions from external models. Silva Fenn. 2022, 56, 10695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacherjee, A. 8.2: Probability sampling. In Social Science Research: Principles, Methods, and Practices; LibreTexts: Davis, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS). Sampling Vegetation Attributes; Field Guidance; NRCS: Washington, DC, USA, 2022.

- Hahn, J.T.; MacLean, C.D.; Arner, S.L.; Bechtold, W.A. Procedures to handle inventory cluster plots that straddle two or more conditions. For. Sci. Monogr. 1995, 31, 12–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yim, J.S.; Shin, M.-Y.; Son, Y.; Kleinn, C. Cluster plot optimization for a large area forest resource inventory in Korea. For. Sci. Technol. 2015, 11, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quon, C.; Lam, T.Y.; Lin, H.-T. Designing Cluster Plots for Sampling Local Plant Species Composition for Biodiversity Management. For. Syst. 2020, 29, e002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Ståhl, G.; McRoberts, R.; Li, B.; Tokola, T.; Hou, Z. Generalizing systematic adaptive cluster sampling for forest ecosystem inventory. For. Ecol. Manag. 2021, 489, 119051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazariani, N.; Fallah, A.; Ramezani, H.; Naghavi, H.; Jalilvand, H. Assessing the Optimum Cluster Sampling Plan for Estimating the Quantitative Characteristics of Zagros Forests (Case Study: Watershed Olad Ghobad Forests). Iran. J. For. 2022, 14, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramezani, H.; Lister, A. Effects of cluster plot design parameters on landscape fragmentation estimates: A case study using data from the Swedish national forest inventory. Appl. Geogr. 2023, 159, 103118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, S.; Xu, L.; Yu, J.; Zhou, W.; Yang, Z.; Wang, S.; Guo, C.; Gao, Y.; Xiao, J.; Shu, Q. Sampling Estimation and Optimization of Typical Forest Biomass Based on Sequential Gaussian Conditional Simulation. Forests 2023, 14, 1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, J.; Mills, R.T.; Hoffman, F.M.; Hargrove, W.W. Parallel k-Means Clustering for Quantitative Ecoregion Delineation Using Large Data Sets. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2011, 4, 1602–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melville, G.; Stone, C. Optimising nearest neighbour information—A simple, efficient sampling strategy for forestry plot imputation using remotely sensed data. Aust. For. 2016, 79, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullahi Sahra, M.; Schardt, M.; Pretzsch, H. An unsupervised two-stage clustering approach for forest structure classification based on X-band InSAR data—A case study in complex temperate forest stands. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2017, 57, 36–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgakis, A.; Gatziolis, D.; Stamatellos, G. A Primer on Clustering of Forest Management Units for Reliable Design-Based Direct Estimates and Model-Based Small Area Estimation. Forests 2023, 14, 1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Han, X.; Zhang, J.; Huang, K.; Peng, M.; Qiu, B.; Yang, K. Integrating Ward’s Clustering Stratification and Spatially Correlated Poisson Disk Sampling to Enhance the Accuracy of Forest Aboveground Carbon Stock Estimation. Forests 2024, 15, 2111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maniatis, D.; Mollicone, D. Options for sampling and stratification for national forest inventories to implement REDD+ under the UNFCCC. Carbon Balance Manag. 2010, 5, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hetzer, J.; Huth, A.; Wiegand, T.; Dobner, H.J.; Fischer, R. An analysis of forest biomass sampling strategies across scales. Biogeosciences 2020, 17, 1673–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heikkinen, J.; Henttonen, H.; Katila, M.; Tuominen, S. Stratified, Spatially Balanced Cluster Sampling for Cost-Efficient Environmental Surveys. Environmetrics 2025, 36, e70019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodbody, T.R.H.; Coops, N.C.; Queinnec, M.; White, J.C.; Tompalski, P.; Hudak, A.T.; Auty, D.; Valbuena, R.; LeBoeuf, A.; Sinclair, I.; et al. sgsR: A structurally guided sampling toolbox for LiDAR-Based forest inventories. Forestry 2023, 96, 411–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maltamo, M.; Bollandsås, O.; Næsset, E.; Gobakken, T.; Packalén, P. Different plot selection strategies for field training data in ALS-assisted forest inventory. For. Int. J. For. Res. 2011, 84, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindgren, N.; Christensen, P.; Nilsson, B.; Åkerholm, M.; Allard, A.; Reese, H.; Olsson, H. Using Optical Satellite Data and Airborne Lidar Data for a Nationwide Sampling Survey. Remote Sens. 2015, 7, 4253–4267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagliarella, M.C.; Sallustio, L.; Capobianco, G.; Conte, E.; Corona, P.; Fattorini, L.; Marchetti, M. From one- to two-phase sampling to reduce costs of remote sensing-based estimation of land-cover and land-use proportions and their changes. Remote Sens. Environ. 2016, 184, 410–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luther, J.E.; Fournier, R.A.; van Lier, O.R.; Bujold, M. Extending ALS-Based Mapping of Forest Attributes with Medium Resolution Satellite and Environmental Data. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgakis, A. Stratification of Forest Stands as a Basis for Small Area Estimations, Proceedings of the 33rd Panhellenic Statistics Conference (2021), pp. 233–247. 2022. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/361391008_Stratification_of_Forest_Stands_as_a_Basis_for_Small_Area_Estimations (accessed on 14 September 2025).

- Melville, G.; Stone, C.; Turner, R. Application of LiDAR data to maximise the efficiency of inventory plots in softwood plantations. N. Z. J. For. Sci. 2015, 45, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queinnec, M.; Coops, N.C.; White, J.C.; McCartney, G.; Sinclair, I. Developing a forest inventory approach using airborne single photon lidar data: From ground plot selection to forest attribute prediction. Forestry 2022, 95, 347–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawbaker, T.; Keuler, N.; Lesak, A.; Gobakken, T.; Contrucci, K.; Radeloff, V. Improved estimates of forest vegetation structure and biomass with a LiDAR-Optimized sampling design. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 2009, 114, G00E03. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deville, J.-C.; Tillé, Y. Efficient balanced sampling: The cube method. Biometrika 2004, 91, 893–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haron, N. Stratified sampling using cluster analysis. AIP Conf. Proc. 2022, 2472, 050012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrd, J. Data Clustering: Intro, Methods, Applications. Encord Blog. 8 November 2023. Available online: https://encord.com/blog/data-clustering-intro-methods-applications/ (accessed on 14 September 2025).

- Abbas, O.A. Comparisons Between Data Clustering Algorithms. Int. Arab J. Inf. Technol. 2008, 5, 320–325. [Google Scholar]

- Ezugwu, A.E.; Ikotun, A.M.; Oyelade, O.O.; Abualigah, L.; Agushaka, J.O.; Eke, C.I.; Akinyelu, A.A. A Comprehensive Survey of Clustering Algorithms: State-of-the-Art Machine Learning Applications, Taxonomy, Challenges, and Future Research Prospects. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2022, 110, 104743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, M.; Comin, C.; Casanova, D.; Bruno, O.M.; Amancio, D.; Rodrigues, F.; da F. Costa, L. Clustering Algorithms: A Comparative Approach. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1612.08388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayashree; Shivaprakash, T. Optimal Value for Number of Clusters in a Dataset for Clustering Algorithm. In Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreopoulos, B.; An, A.; Wang, X.; Schroeder, M. A roadmap of clustering algorithms: Finding a match for a biomedical application. Brief. Bioinform. 2009, 10, 297–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Pei, J.; Tong, H. Data Mining: Concepts and Techniques, 4th ed.; Morgan Kaufmann: Burlington, MA, USA, 2022; pp. 1–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagolewski, M. A framework for benchmarking clustering algorithms. SoftwareX 2022, 20, 101270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Feng, Q.; Huang, J.; Guo, Y.; Xu, J.; Wang, J. A local search algorithm for k-means with outliers. Neurocomputing 2021, 450, 230–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak-Brzezińska, A.; Gaibei, I. How the Outliers Influence the Quality of Clustering? Entropy 2022, 24, 917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garge, N.R.; Page, G.P.; Sprague, A.P.; Gorman, B.S.; Allison, D.B. Reproducible clusters from microarray research: Whither? BMC Bioinform. 2005, 6 (Suppl. S2), S10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Chambers, E., IV. Unreliability of clustering results in sensory studies and a strategy to address the issue. Front. Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 4, 1271193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, Z.-Y.; Ong, L.-Y.; Leow, M.-C. A Review on Clustering Techniques: Creating Better User Experience for Online Roadshow. Future Internet 2021, 13, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacQueen, J.B. Some methods for classification and analysis of multivariate observations. In Proceedings of the Fifth Berkeley Symposium on Mathematical Statistics and Probability; Le Cam, L.M., Neyman, J., Eds.; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1967; Volume 1, pp. 281–297. [Google Scholar]

- Bock, H.H. Origins and extensions of the k-means algorithm in cluster analysis. Electron. J. Hist. Probab. Stat. 2008, 4. Available online: https://www.jehps.net/Decembre2008/Bock.pdf (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Wani, A. Comprehensive analysis of clustering algorithms: Exploring limitations and innovative solutions. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2024, 10, e2286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, A.K.; Murty, M.N.; Flynn, P.J. Data clustering: A review. ACM Comput. Surv. 1999, 31, 264–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabezas, R.; Izbicki, M.; Stern, R. Hierarchical clustering: Visualization, feature importance and model selection. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2112.01372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shetty, S.; Singh, A. Hierarchical clustering: A survey. Int. J. Comput. Appl. 2021, 178, 178–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campello, R.J.G.B.; Moulavi, D.; Sander, J. Density-Based clustering based on hierarchical density estimates. In Advances in Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining; Pei, J., Tseng, V.S., Cao, L., Motoda, H., Xu, G., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 160–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Zhang, L.; Wang, H. An overview of clustering methods with guidelines for practical applications. Inf. Sci. 2023, 630, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HDBSCAN Development Team. HDBSCAN: How HDBSCAN Works. Available online: https://hdbscan.readthedocs.io/en/latest/how_hdbscan_works.html (accessed on 27 September 2025).

- Tompalski, P.; White, J.C.; Coops, N.C.; Wulder, M.A. Demonstrating the transferability of forest inventory attribute models derived using airborne laser scanning data. Remote Sens. Environ. 2019, 227, 110–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IUL. Forest Management Manual; Święcicki, Z., Ed.; Ośrodek Rozwojowo-Wdrożeniowy Lasów Państwowych w Bedoniu: Andrespol, Poland, 2012. (In Polish)

- Bruchwald, A.; Dudek, A.; Michalak, K.; Rymer-Dudzińska, T.; Wróblewski, L.; Zasada, M. Wzory empiryczne do określania wysokości i pierśnicowej liczby kształtu grubizny drzewa (Empirical formulae for defining height and dbh shape figure of thick wood). Sylwan 2000, 10, 5–13. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Gschwantner, T.; Alberdi, I.; Bauwens, S.; Bender, S.; Borota, D.; Bosela, M.; Bouriaud, O.; Breidenbach, J.; Donis, J.; Fischer, C.; et al. Growing stock monitoring by European National Forest Inventories: Historical origins, current methods and harmonisation. Forest Ecol. Manag. 2022, 505, 119868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobakken, T.; Næsset, E. Assessing effects of positioning errors and sample plot size on biophysical stand properties derived from airborne laser scanner data. Can. J. For. Res. 2009, 39, 1036–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisańczuk, M.; Mitelsztedt, K.; Stereńczak, K. The Influence of the Spatial Co-Registration Error on the Estimation of Growing Stock Volume Based on Airborne Laser Scanning Metrics. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 4709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roussel, J.-R.; Auty, D.; Coops, N.C.; Tompalski, P.; Goodbody, T.R.H.; Meador, A.S.; Bourdon, J.-F.; de Boissieu, F.; Achim, A. lidR: An R package for analysis of Airborne Laser Scanning (ALS) data. Remote Sens. Environ. 2020, 251, 112061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liaw, A.; Wiener, M. randomForest: Breiman and Cutler’s Random Forests for Classification and Regression, R Package Version 4.7-1.2. Computer Software. Comprehensive R Archive Network (CRAN): Online, 2024. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/package=randomForest (accessed on 28 September 2025).

- Næsset, E.; Gobakken, T. Estimating forest growth using canopy metrics derived from airborne laser scanner data. Remote Sens. Environ. 2005, 96, 453–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkitna, K.; Krok, G.; Miścicki, S.; Ukalski, K.; Lisańczuk, M.; Mitelsztedt, K.; Magnussen, S.; Markiewicz, A.; Stereńczak, K. Modelling growing stock volume of forest stands with various ALS area-based approaches. Forestry 2021, 94, 630–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SILP—Biuro Urządzania Lasu i Geodezji Leśnej. System Informatyczny Lasów Państwowych (SILP); 2015, 2020, 2021. Available online: https://www.zilp.lasy.gov.pl/ (accessed on 14 September 2025).

- Silverman, B.W. Density Estimation for Statistics and Data Analysis; Chapman & Hall: London, UK, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Moeur, M.; Stage, A.R. Most similar neighbor: An improved sampling inference procedure for natural resource planning. For. Sci. 1995, 41, 337–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loosmore, N.B.; Ford, E.D. Statistical inference using the G or K point pattern spatial statistics. Ecology 2006, 87, 1925–1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, R.A. Statistical Methods for Research Workers; Oliver & Boyd: Edinburgh, UK, 1925. [Google Scholar]

- Hogg, R.V.; Tanis, E.A.; Zimmerman, D.L. Probability and Statistical Inference, 9th ed.; Pearson: Boston, MA, USA, 2015; ISBN 978-0-321-92327-1. [Google Scholar]

- Mascha, E.J.; Vetter, T.R. Significance, Errors, Power, and Sample Size: The Blocking and Tackling of Statistics. Anesth. Analg. 2018, 126, 691–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraenkel, J.R.; Wallen, N.E. How to Design and Evaluate Research in Education, 7th ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2009; ISBN 978-0-07-352596-9. [Google Scholar]

- Rabosky, D.L.; Grundler, M.; Anderson, C.; Title, P.; Shi, J.J.; Brown, J.W.; Huang, H.; Larson, J.G. BAMMtools: An R package for the analysis of evolutionary dynamics on phylogenetic trees. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2014, 5, 701–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing, version 5.5; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2025; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Probst, P.; Boulesteix, A.-L.; Wright, M. Hyperparameters and Tuning Strategies for Random Forest. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1804.03515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random Forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oshiro, T.; Perez, P.; Baranauskas, J. How Many Trees in a Random Forest? In Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; Volume 7376, pp. 154–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Probst, P.; Boulesteix, A.-L. To tune or not to tune the number of trees in random forest? J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2017, 18, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grafström, A.; Lundstrom, N.L.P.; Schelin, L. Spatially balanced sampling through the Pivotal method. Biometrics 2012, 68, 514–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanungo, T.; Mount, D.M.; Netanyahu, N.S.; Piatko, C.D.; Silverman, R.; Wu, A.Y. An efficient k-means clustering algorithm: Analysis and implementation. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2002, 24, 881–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.; Aryani, A.; Petrie, S.; Nambissan, A.; Astudillo, A.; Cao, S. A Rapid Review of Clustering Algorithms. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.07389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnussen, S.; Næsset, E.; Gobakken, T. An application niche for finite mixture models in forest resource surveys. Can. J. For. Res. 2019, 49, 1453–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.K.H.; Chakraborty, A.; Petris, G.; Wilson, B. Constrained Functional Regression of National Forest Inventory Data Over Time Using Remote Sensing Observations. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 2020, 116, 1168–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, J.; Li, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, R.; Habib, A. Optimization Method of Airborne LiDAR Individual Tree Segmentation Based on Gaussian Mixture Model. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 6167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymkiewicz, B. Tablice Zasobności i Przyrostu Drzewostanów Sosnowych, Świerkowych, Jodłowych, Dębowych i Bukowych; Państwowe Wydawnictwo Rolnicze i Leśne: Warszawa, Poland, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Chen, Z.; Zhao, Z. Assessing the accuracy of forest above-ground biomass and carbon storage estimation by meta-analysis based close-range remote sensing. For. Res. 2025, 5, e017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouret, F.; Morin, D.; Planells, M.; Vincent-Barbaroux, C. Tree Species Classification at the Pixel Level Using Deep Learning and Multispectral Time Series in an Imbalanced Context. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Boonprong, S.; Wang, S.; Zhang, Z.; Liang, W.; Xu, M.; Yang, X.; Wang, K.; Li, J.; Gao, X.; et al. Dominant Tree Species Mapping Using Machine Learning Based on Multi-Temporal and Multi-Source Data. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 4674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, C.; Li, M.; Liu, Z. Influence of Variable Selection and Forest Type on Forest Aboveground Biomass Estimation Using Machine Learning Algorithms. Forests 2019, 10, 1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotze, J.D.F.; Beukes, H.B.; Seifert, T. Essential environmental variables to include in a stratified sampling design for a national-level invasive alien tree survey. iForest 2019, 12, 418–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Li, G.; Lu, D.; Chen, E.; Wei, X. Stratification-Based Forest Aboveground Biomass Estimation in a Subtropical Region Using Airborne Lidar Data. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Liu, X.; Cheng, S.; Yang, C.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Dong, L.; Li, F.; Hao, Y. Evaluating the effectiveness of forest type stratification for aboveground biomass inference. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2025, 143, 104829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köhl, M.; Lister, A.; Scott, C.T.; Baldauf, T.; Plugge, D. Implications of sampling design and sample size for national carbon accounting systems. Carbon Balance Manag. 2011, 6, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; Yang, J. Effects of sampling approaches on quantifying urban forest structure. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2020, 195, 103722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Häbel, H.; Kuronen, M.; Henttonen, H.M.; Kangas, A.; Myllymäki, M. The effect of spatial structure of forests on the precision and costs of plot-level forest resource estimation. For. Ecosyst. 2019, 6, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patummasut, M.; Borkowski, J. Adaptive Cluster Sampling with Spatially Clustered Secondary Units. J. Appl. Sci. 2014, 14, 2516–2522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Cabin, R.J.; Clewell, A.; Ingram, M.; McDonald, T.; Temperton, V. Bridging Restoration Science and Practice: Results and Analysis of a Survey from the 2009 Society for Ecological Restoration International Meeting. Restor. Ecol. 2010, 18, 494–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poudyal, B.H.; Maraseni, T.; Cockfield, G. Scientific Forest Management Practice in Nepal: Critical Reflections from Stakeholders’ Perspectives. Forests 2020, 11, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, T.; Falconer, M.; Hutchen, J.; Westwood, A.R.; Young, N.; Nguyen, V.M. Implementing and evaluating knowledge exchange: Insights from practitioners at the Canadian Forest Service. Environ. Sci. Policy 2023, 148, 103549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fassnacht, F.E.; Latifi, H.; Hartig, F. Using synthetic data to evaluate the benefits of large field plots for forest biomass estimation with LiDAR. Remote Sens. Environ. 2018, 213, 115–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, B.; Ritsos, P.D.; Headleand, C. Virtual Forestry Generation: Evaluating Models for Tree Placement in Games. Computers 2020, 9, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, J.F.; Nunes, R.; Peixoto, P. Procedural Generation of Synthetic Forest Environments to Train Machine Learning Algorithms. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Philadelphia, PA, USA, 23–27 May 2022; pp. 10317–10323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duong, T.H.K.; Vega, C.; Renaud, J.-P.; Chauvet, G.; Bouriaud, O. A large-Scale Artificial Forest Tree Population for Sampling and Estimation Methods Simulations [Data Set]. Zenodo. 2023. Available online: https://zenodo.org/records/10252806 (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Jevšenak, J.; Arnič, D.; Krajnc, L.; Skudnik, M. Machine Learning Forest Simulator (MLFS): R package for data-driven assessment of the future state of forests. Ecol. Inform. 2023, 75, 102115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattaneo, N.; Astrup, R.; Antón-Fernández, C. PixSim: Enhancing high-resolution large-scale forest simulations. Softw. Impacts 2024, 21, 100695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Qi, J.; Liu, S.; Zhao, X.; Huang, H. Evaluating forest aboveground biomass estimation model using simulated ALS point cloud from an individual-based forest model and 3D radiative transfer model across continents. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 372, 123287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AI Sweden. Synthetic Data and AI Are Taking Forestry into the Future. Available online: https://www.ai.se/en/news/synthetic-data-and-ai-are-taking-forestry-future (accessed on 30 September 2025).

| Algorithm | Common Usage | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|---|

| K-means (1) | Partitioning data into k clusters with roughly spherical, equally sized clusters. Market segmentation, image compression, etc. |

|

|

| Hierarchical Clustering (2) (Agglomerative/ Divisive) | Exploratory data analysis for hierarchical structures; used in biology, taxonomy, document clustering, etc. |

|

|

| HDBSCAN (3) (Hierarchical Density-Based Spatial Clustering of Applications with Noise) | Clustering with noise, uneven densities, irregular shapes; used in spatial, astrophysics, geospatial data, etc. |

|

|

| IDS (Individual Dimension Sampling) | Original authors’ algorithm tested in this study | ||

| District | Average Age | GSV [m3/ha] | Moran’s I * | Major Tree Species |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Białowieża | 110 | 401 | 0.012 | Norway spruce, Oak, Black alder, Scotch pine, Hornbeam |

| Głogów | 57 | 309 | 0.066 | Scotch pine, Beech, Silver fir, Oak |

| Gorlice | 64 | 373 | 0.035 | Beech, Silver fir, Scotch pine |

| Herby | 60 | 325 | 0.031 | Scotch pine, Oak |

| Katrynka | 60 | 395 | 0.059 | Scotch pine, Norway spruce |

| Taczanów | 77 | 304 | 0.042 | Scotch pine, Oak |

| Leżajsk | 62 | 354 | 0.012 | Scotch pine, Beech, Oak, Silver fir |

| Milicz | 60 | 379 | 0.013 | Scotch pine, Oak, Beech |

| Pieńsk | 54 | 303 | 0.005 | Scotch pine, Norway spruce, Birch |

| Supraśl | 58 | 400 | 0.002 | Scotch pine, Norway spruce, Oak |

| Group | Variables | Source/Definition |

|---|---|---|

| ALS central tendency | mean height | lidR [142] |

| ALS dispersion | height sd | lidR [142] |

| ALS quantiles | height 1st quartile, 95th height percentile | lidR [142] |

| ALS cumulative histograms | square of the ratio between the number of points above 2nd threshold to all points, square of ratio between the number of points below 7th height threshold to all points | [53,144,145] |

| Species related | coniferous species share, dominant species share, Shannon diversity index | ground inventory [15] |

| Age related | average age, natural logarithm of average age | ground inventory, GIS layers, previous inventories [146] |

| Factors | Levels |

|---|---|

| Kernel plot ID | 1, 10, 20, 30, …, 580 |

| k-neighbours | 100, 250, 500, 1000 |

| Sampling intensity | 100, 200, 300 |

| Repetitions | 1,2,3, …, 30 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lisańczuk, M.; Hycza, T.; Stereńczak, K. Efficiency of Data Clustering for Stratification and Sampling in the Two-Phase ALS-Enhanced Forest Stock Inventory. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3871. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17233871

Lisańczuk M, Hycza T, Stereńczak K. Efficiency of Data Clustering for Stratification and Sampling in the Two-Phase ALS-Enhanced Forest Stock Inventory. Remote Sensing. 2025; 17(23):3871. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17233871

Chicago/Turabian StyleLisańczuk, Marek, Tomasz Hycza, and Krzysztof Stereńczak. 2025. "Efficiency of Data Clustering for Stratification and Sampling in the Two-Phase ALS-Enhanced Forest Stock Inventory" Remote Sensing 17, no. 23: 3871. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17233871

APA StyleLisańczuk, M., Hycza, T., & Stereńczak, K. (2025). Efficiency of Data Clustering for Stratification and Sampling in the Two-Phase ALS-Enhanced Forest Stock Inventory. Remote Sensing, 17(23), 3871. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17233871