Highlights

What are the main findings?

- Development of the HYDRUS-1D for soil moisture estimation.

- CHRS-CCS verified as optimum remote sensing precipitation data for the soil moisture estimation.

What are the implications of the main findings?

- Model developed by incorporating comprehensive uncertainty analysis based on the measured data can be confidently used to understand the long-term soil moisture dynamics in a region with well-drained and highly permeable soils.

- Understanding the soil water balance dynamics in the absence of long-term measured data using publicly available remotely sensed data.

Abstract

Soil moisture plays a key role in the critical zone of the Earth and has extensive value in the understanding of hydrological, agricultural, and environmental processes (among others). Long-term (in situ) monitoring of soil moisture measurements is generally not practical; however, short-term measurements are often found. Limited soil moisture measurements can be employed to develop a numerical model for long-term and accurate soil moisture estimations. A key input variable to the model is precipitation, which is also not easily accessible, particularly at a finer spatial resolution; hence, publicly available remote sensing data can be used as an alternative. This study, therefore, aims to develop a numerical model HYDRUS-1D to estimate soil moisture in the data-scarce state of the Northern Territory, Australia, with a land cover of shrubland and a Tropical-Savannah type climate. The HDYRUS-1D is based on the numerical solution of Richards’ equation of variably saturated flow that relies on information about the soil water retention characteristics. This study utilized the van Genuchten model parameters, which were optimized (against measured soil moisture) through parameter optimization with initial estimates obtained from the HYDRUS catalogue. Initial estimates from different sources can differ for the same soil texture (e.g., loamy sand) and can induce uncertainties in the calibrated model. Therefore, a comprehensive uncertainty analysis was conducted to address potential uncertainties in the calibration process. The HYDRUS-1D was calibrated for a period between March 2012 and February 2013 and was independently validated against three different periods between March 2013 and October 2016. Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), Pearson’s correlation coefficient (R), and Mean Absolute Error (MAE) were used to assess the efficiency of the model in simulating the measured soil moisture. The model exhibited good performance in replicating measured soil moisture during calibration (RMSE = 0.00 m3/m3, MAE = 0.005 m3/m3, and R = 0.70), during validation period 1 (RMSE = 0.035 m3/m3 and MAE = 0.023 m3/m3, and R = 0.72), validation period 2 (RMSE = 0.054 m3/m3 and MAE = 0.039 m3/m3, and R = 0.51), and validation period 3 (RMSE = 0.046 m3/m3 and MAE = 0.032 m3/m3, and R = 0.61), respectively. Remotely sensed precipitation data were used from the CHRS-PERSIANN, CHRS-CCS, and CHRS-PDIR-Now to assess their capabilities in estimating soil moisture. Efficiency evaluation metrics and visual assessment revealed that these products underestimated the soil moisture. The CHRS-CCS outperformed other products in terms of overall efficiency (average RMSE of 0.040 m3/m3, average MAE of 0.023 m3/m3, and an average R of 0.68, respectively). An integrated approach based on numerical modelling and remote sensing employed in this study can help understand the long-term dynamics of soil moisture and soil water balance in the Northern Territory, Australia.

1. Introduction

Soil moisture is an integral part of the soil water balance; however, its long-term determination has often been challenging. Multiple methods are available for determining soil moisture, including drying methods, sensor techniques, remote sensing technologies, and geophysical approaches [1,2]. Drying methods and sensor methods are often used owing to their high precision; however, time and labour costs often outweigh their benefits [3]. Remote sensing technologies offer the advantage of obtaining soil moisture distribution characteristics at large scales, albeit constrained by resolution and detection depth limitations [4,5], their local-scale applications are also limited because of their coarse spatial resolutions. Although soil moisture sensors are considered a good overall tool in determining accurate soil moisture [6], challenging aspects associated with their use (such as cost, calibration, maintenance, and spatial variability) often limit their extensive and long-term deployment [7].

In some instances, short-term in situ soil moisture measurements are carried out (mostly as part of the research projects), and after a certain period, these measurements cease to exist, while the recorded measurements are either made public (such as through the International Soil Moisture Network, ISMN), personal or institutional depositories, or can be requested (if the source is known, guaranteed access is not promised). The ISMN [8,9] is one of such initiatives; it is a global database of in situ soil moisture measurements which are provided by numerous networks hosted on the ISMN database. While for some regions many locations are covered by ISMN’s networks, other regions have a scarcity of in situ measurements. One such example is the state of Northern Territory, Australia, where there is only one site offering in situ soil moisture measurements from the ISMN database.

These limited soil moisture measurements can be effectively used to extend their temporal availability (through numerical modelling, for instance). Numerous models (based on the Richards equation of variably saturated flow [10]) have been developed to represent vadose zone processes (e.g., soil moisture movement in the subsurface). One of the most widely used models to analyse flow within the unsaturated zone is the HYDRUS-1D [11], which numerically solves the Richards equation [11,12,13]. Solution of the Richards equation requires knowledge of the soil properties and soil water retention characteristics, which are typically depicted by different empirical models of soil water retention characteristics; the most used is the one from van Genuchten [14].

While knowledge of the parameters representing the soil-water retention characteristics is integral to vadose zone modelling, their field or laboratory measurements are tedious and costly [15,16]. In the absence of such measurements, other (indirect) methods are often used to obtain unsaturated soil hydraulic properties and the hydraulic conductivity functions (input parameters hereafter). Reference values reported in the literature are often used [17]; however, this is also not the case for many study regions. Therefore, other indirect methods, such as soil catalogues, pedotransfer functions (PTFs) [15,18] such as Rosetta [19], and parameter optimization approaches are often used instead.

Soil catalogues can be used to estimate the input parameters, given the soil texture is known (e.g., sand, clay, loam). In the HYDRUS-1D, the input parameters of selected soils are included in a catalogue (HYDRUS catalogue hereafter) taken from Carsel and Parrish, Ref. [20] for the van Genuchten model. For PTFs, the HYDRUS-1D was coupled with Rosetta DLL (Dynamically Linked Library), developed independently [19]. Rosetta implements PTFs which predict the input parameters in a hierarchical manner from soil textural class information (sand, clay, loam, etc.) (ROSETTA catalogue hereafter), the soil textural distribution (percentage of sand, silt, and clay, bulk density), and one or two water retention points as input. Parameter optimisation (or inverse solution) typically minimises an objective function, which exhibits the discrepancy between the measurements and the predicted system response (estimated and measured soil moisture, for instance). Reasonable initial estimates are required for parameter optimization, which are then iteratively improved (using different methods) during the minimisation process until a certain degree of precision is achieved.

If the model is to be developed in the absence of any measurement data (e.g., soil moisture, pressure heads), then soil catalogues can be used. However, if the measurement data are available and parameter optimization is to be used to achieve the optimum input parameters, then the initial estimates become critical. Different initial parameters can lead to uncertainties in the final model outputs. For instance, the initial estimates from the HYDRUS catalogue or ROSETTA catalogue for the same soil type (e.g., sand) may be different. This is why the HYDRUS-1D does not accept unreasonable (out-of-range) initial estimates, and the developer of the model has laid the responsibility of selecting reasonable initial estimates on the user. Therefore, the knowledge (as much as available) of the study area, its soil types and their characteristics (e.g., if they are well drained and highly permeable, indicating a higher value of hydraulic conductivity), plays a key role in overall uncertainty reduction associated with the model development.

The HYDRUS-1D has been used for a variety of applications. Davies et al. [21], Fournel et al. [22], and Usman et al. [23] successfully developed and applied the HYDRUS-1D in Germany, France, and Australia, respectively. The accuracy of the developed model was verified against the in situ measurements, e.g., soil moisture (water content), while initial soil parameter values were derived from soil catalogues using different levels of input data.

One of the key variables for successfully developing a numerical model to estimate soil moisture is precipitation. While rainfall gauging stations provide reliable precipitation data, it is often not publicly available (at a finer resolution) or is not available for a period long enough to coincide with the period of limited availability of soil moisture data. In these instances, remotely sensed precipitation data fills in the gap. Owing to the immense potential of satellite precipitation products, research has been conducted [24,25,26,27,28,29,30] to assess and validate these products. Different satellite-based products offering precipitation data (among many, but with finer temporal resolution) include CHRS-PERSIANN, CHRS-CCS, and CHRS-PDIR-Now, which have been extensively used [31,32,33] and have the potential to be used in the understanding of the hydrological cycle and soil water balance.

This study, therefore, has twofold objectives: (i) to utilize the limited ISMN soil moisture measurements to develop the HYDRUS-1D by incorporating comprehensive uncertainty analysis in the model calibration process; (ii) to explore the potential of remotely sensed precipitation data from three different products, including CHRS-PERSIANN, CHRS-CCS, and CHRS-PDIR-Now, integrated with the previously developed numerical model to estimate soil moisture. This study will ensure the continuity of research in the public domain (in the absence of long-term in situ measurements) and will help understand the dynamics of soil moisture and the soil water balance in the Northern Territory, Australia.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Datasets

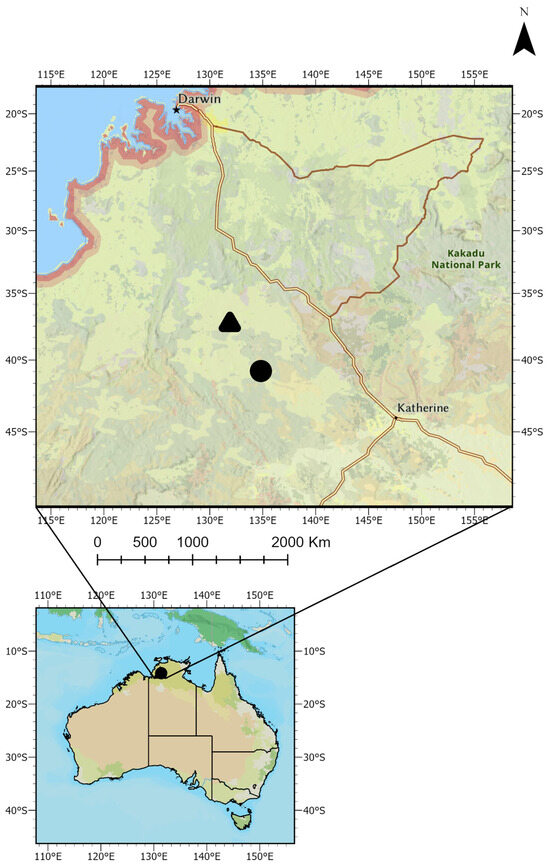

The study area is located in the state of Northern Territory (NT), Australia (Figure 1). Precipitation data (hourly) were obtained from the Bureau of Meteorology (BoM), Australia, while evapotranspiration data (daily) were obtained from SILO climate data services provided by the Queensland Government, Australia, through the following website https://www.longpaddock.qld.gov.au/silo/ (accessed on 25 October 2025). These data were obtained for the period between 2012 and 2017, measured at a BoM monitoring station “Douglas River Research Farm” which is located in the BoM district named “Darwin-Daly” in the state of NT.

Figure 1.

Study area location. Black dot representing the soil moisture station (Daly) and black triangle represents BoM’s meteorological station i.e., Douglas River Research Farm.

Soil moisture data (saturation, m3/m3) were obtained from the ISMN database, https://ismn.earth/en/dataviewer/# (accessed on 25 October 2025). The COSMOS (Cosmic-Ray Soil Moisture Observing System) is one of the networks providing soil moisture data for the ISMN, which utilizes a probe known as the “Cosmic-ray probe” to measure soil moisture [34,35]. “The cosmic-ray soil moisture probe measures the neutrons that are generated by cosmic rays within air and soil and other materials, moderated by mainly hydrogen atoms located primarily in soil water, and emitted to the atmosphere where they mix instantaneously at a scale of hundreds of meters and whose density is inversely correlated with soil moisture” [35]. The measured intensity (cosmic-ray neutron) is then converted to soil moisture using a calibration function given elsewhere [36], see Zreda et al. [35] and Desilets et al. [36] for further details.

The in situ soil moisture data were obtained for Daly station (ISMN soil moisture hereafter) for a depth of 0–55 cm, and only values with a quality flag of “good” were used. These data for Daly Station were further subjected to curation, and periods with substantial missing values were excluded from the analysis. Average depth below ground near Daly is greater than 50 m (from a nearby well number RN025288, The NT Water Data WebPortal v2025.2.52 (accessed on 25 October 2025)). Vegetation in the region is shrubland (ESA CCI Land Cover (CCI_landcover_2010, v1.6.1) or open woodland (grass with trees, usually eucalyptus) (Native vegetation in the NT, factsheet, Department of Land Resource Management, https://environment.nt.gov.au/ (accessed on 25 October 2025)), while the climate is Tropical—Savannah (Version 2017 Koeppen-Geiger Climate Classification).

2.1.1. Remotely Sensed Data

Remotely sensed precipitation data were used from three remote sensing products, which are explained below.

2.1.2. Precipitation Estimation from Remotely Sensed Information Using Artificial Neural Networks (PERSIANN)

The Center for Hydrometeorology and Remote Sensing CHRS-PERSIANN (Precipitation Estimation from Remotely Sensed Information using Artificial Neural Networks) system uses neural network function classification/approximation procedures to compute an estimate of rainfall rate at each 0.25° × 0.25° pixel of the infrared brightness temperature image provided by geostationary satellites. An adaptive training feature facilitates updating of the network parameters whenever independent estimates of rainfall are available. The CHRS-PERSIANN system was based on geostationary infrared imagery and later extended to include the use of both infrared and daytime visible imagery. The PERSIANN algorithm used here is based on the geostationary longwave infrared imagery to generate global rainfall. Rainfall product covers 50°S to 50°N globally. The system uses grid infrared images of global geosynchronous satellites (GOES-8, GOES-10, GMS-5, Metsat-6, and Metsat-7) provided by CPC, NOAA to generate accumulated rainfall.

2.1.3. CHRS-Cloud Classification System (CHRS-CCS)

CHRS has developed a new version of PERSIANN, i.e., CHRS-CCS. CHRS-CCS enables the categorization of cloud-patch features based on cloud height, areal extent, and variability of texture estimated from satellite imagery. At the heart of CHRS-CCS is the variable threshold cloud segmentation algorithm. In contrast with the traditional constant threshold approach, the variable threshold approach enables the identification and separation of individual patches of clouds. The individual patches can then be classified based on texture, geometric properties, dynamic evolution, and cloud top height. These classifications help in assigning rainfall values to pixels within each cloud based on a specific curve describing the relationship between rain-rate and brightness temperature. Precipitation intensity and distribution of classified cloud patch is initially trained using ground radar and TRMM observations. CHRS-CCS enables recursive (in space and time) data assimilation and system training, allowing for flexibility in the adjustment of the cloud–rain distribution curves as new ground or space-based radar measurements become available.

2.1.4. The Precipitation Estimation from Remotely Sensed Information Using Artificial Neural Networks—Dynamic Infrared Rain Rate near Real-Time (CHRS-PDIR-Now)

The Precipitation Estimation from Remotely Sensed Information using Artificial Neural Networks—Dynamic Infrared Rain Rate near real-time (CHRS-PDIR-Now) is a real-time global high-resolution (0.04° × 0.04°) satellite precipitation product developed by the CHRS. The main advantage of CHRS-PDIR-Now, compared to other near-real-time precipitation datasets, is its reliance on the high-frequency sampled IR imagery; consequently, the latency of CHRS-PDIR-Now from the time of rainfall occurrence is very short (15–60 min). The short latency of CHRS-PDIR-Now renders the dataset well-suited for near-real-time hydrologic applications such as flood forecasting and developing flood inundation maps.

All three datasets mentioned above can be freely accessed from the CHRS data portal at https://chrsdata.eng.uci.edu/ (accessed on 25 October 2025).

2.2. HYDRUS-1D, Setup, and Development

The HYDRUS-1D model was used for the simulation of soil moisture in the vadose zone. The model is based on the Richards equation for variably saturated water flow:

where h is pressure head [L], θ [L3/L3] is the volumetric water content, t is time [T], x is spatial coordinate [L], S(h) is the sink term [L3/L3T], and K is the unsaturated hydraulic conductivity function [L/T]. Many users of the model use the van Genuchten–Mualem constitutive relationship for the numerical solutions of the highly non-linear Richards equation:

where θ(h) is volumetric water content, is the residual water content [L3/L3], is the saturated water content [L3/L3], a is the soil water retention function [1/L], m and n are empirical shape factors, K(h) is the unsaturated hydraulic conductivity [L/T], and is the saturated hydraulic conductivity [L/T], is effective saturation. The pore-connectivity parameter was estimated to be 0.5 as an average for many soils [37].

2.2.1. Transport Domain, Initial and Boundary Conditions

A 150 cm deep soil profile (transport domain) was considered in this study. Soil profile consisted of well-drained sand with a textural class of Sandy loam (0–8 cm), Loamy Sand (8–66 cm), and Clayey sand (66–150 cm). Clayey sand has similar clay content (5% to 10%) as loamy sand and was considered as such in the model setup. Data for soil type was used from the Soil Site Visit Data Report from the Australian National Soil Information System (ANSIS). The transport domain was discretized into 150 nodes. Initial conditions were assigned in terms of water content (from ISMN soil moisture data).

The surface boundary condition was assigned as “Atmospheric BC with Surface Runoff”, with evapotranspiration and precipitation as the inputs to the model. Potential evapotranspiration was divided (within the HYDRUS-1D) into evaporation and transpiration by using leaf area index (LAI) (appropriate for the site’s land cover) and extinction coefficient, while the bottom boundary was considered as free drainage appropriate for locations with deeper groundwater tables [33]. The COSMOS sensors provide soil moisture across the reporting depth (0–55 cm for Daly station), unlike other sensors (e.g., the ones that are capacitance-based or rely on frequency domain techniques), which provide the soil moisture for an exact depth. This aspect was considered in the model development, and an observation node was placed halfway through this depth and was assumed to be the representative of the whole soil moisture measuring depth [35,38].

2.2.2. Model Calibration

Calibrating a model (also referred to as history matching [39] refers to the process of tuning a model for a specific problem (e.g., soil moisture estimation) by adjusting the input parameters (within reasonable ranges) and initial and boundary conditions. The process continues until the simulated model results closely match the observed variables (e.g., pressure heads) [40]. A successfully calibrated model is considered the one that can reproduce the measured data within some subjectively acceptable level of precision [41]. Model calibration is not just to calibrate a model but rather to optimize unknown parameters in that model; this process is generally termed parameter optimization [42].

The HYDRUS-1D needs knowledge of unknown input parameters, specifically consisting of , a, n, and (The pore-connectivity parameter is generally not calibrated; among all these input parameters, Ks depicts higher variability, so it is either measured or used from an existing source, complemented with some knowledge of the study area’s soil characteristics). If all of these properties can be measured (laboratory or field experimentation), model calibration is not required; however, it is often not practical to measure all the input parameters due to the required resources, therefore indirect methods like soil catalogues, PTFs, or parameter optimization methods are used (see Introduction section).

For parameter optimization, initial estimates of the input parameters are required, which are then iteratively improved during the minimization process until a certain degree of precision is achieved. In HYDRUS-1D, minimization of the difference between estimated and measured soil moisture (can be other variables like pressure heads), is accomplished by using the Levenberg–Marquardt nonlinear minimization method (a weighted least-squares approach based on Marquardt’s maximum neighbourhood method) [43]. This method combines the Newton and steepest descent methods and generates confidence intervals for the optimized parameters.

2.2.3. Uncertainty Analysis and Selection of Optimum Input Parameters

In this study , a, and n are the input parameters that are calibrated. A five-step process to determine the optimum input parameters was envisioned in this study, incorporating a comprehensive uncertainty analysis addressing the impact of initial input parameter estimates on model calibration. The five-step process started initially by running the HYDRUS-1D model with input parameters obtained using the HYDRUS catalogue and obtaining the model-simulated output (soil moisture). In the second step, the input parameters were obtained from the ROSETTA catalogue, and the model-simulated soil moisture was obtained. In the third step, the best performing (statistically and visually, see Section 2.2.4) set of input parameters in terms of replicating the ISMN soil moisture out of these two methods (HYDRUS catalogue and ROSETTA catalogue) was chosen for further parameter optimization. In the fourth step, parameter optimization (through the Levenberg–Marquardt method, based on the ISMN soil moisture measurements) was performed (based on the selected initial estimates in the third step) to minimize the discrepancies between the ISMN and the HYDRUS-1D estimated soil moisture. Four initial input parameters estimate , a, and n were optimized in the fourth step. As exhibits the largest variability among all the input parameters for a given soil type, values (from the initial estimates that were not considered for parameter optimization) were used in the fifth step to assess the impact of on the optimized parameters.

Four different models resulted during this process which will be referred to as M1, M2, M3, and M4, corresponding to the first, second, fourth, and fifth steps, respectively. Then, the HYDRUS-1D simulated soil moisture using these four different model versions was assessed using efficiency evaluation metrics (see Section 2.2.4) against the ISMN measurements. Finally, the best performing model with optimum efficiency evaluation metrics values was considered calibrated.

2.2.4. Efficiency Evaluation Metrics and Model Validation

Three different efficiency evaluation metrics, including Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), Pearson’s correlation coefficient (R), and Mean Absolute Error (MAE) were used to assess the performance of the model by comparing the HYDRUS-1D simulated soil moisture against the ISMN soil moisture. RMSE measures total error within a sample set that takes greater influence from large errors [44], and it also quantifies the precision of model predictions for continuous datasets, being the average variance between its predicted values and actual data points (i.e., observed values [45]). R is a statistic quantifying the magnitude of a linear association between two variables.

Performance of the model versions M1, M2, M3, and M4 (during calibration period, Section 2.2.3) in replicating ISMN soil moisture was assessed using RMSE, R, and MAE. The model was calibrated against the ISMN soil moisture for the period 01-Mar-12 to 28-Feb-13 at an hourly temporal scale. The previously calibrated HYDRUS-1D model (see Section 2.2.3) was then used to verify its performance in three independent time periods: the first validation period was from 01-Mar-13 to 31-Oct-13, the second validation period was from 01-Nov-13 to 30-Apr-14, and the third validation period was from 01-Nov-15 to 31-Oct-16, respectively. There were 8760 data points that were considered during the calibration period, 5880 data points during the first validation period, 4344 data points during the second validation period, and 8784 data points during the third validation period, respectively.

2.3. Soil Moisture Estimates Using Remotely Sensed Data

Hourly precipitation data from the CHRS-PERSIANN, CHRS-CCS, and CHRS-PDIR-Now were acquired to run the previously calibrated and validated model to estimate soil moisture. The same periods for calibration and validation were used to assess the remotely sensed precipitation-fed soil moisture estimates (through HYDRUS-1D), using the same statistical measures as earlier. Input precipitation data, including BoM and three remotely sensed sources for the calibration period and three validation periods, is given in the Supplementary Materials (Figures S1–S4).

3. Results

3.1. Model Development

3.1.1. Uncertainty Analysis and Selection of Optimum Input Parameters

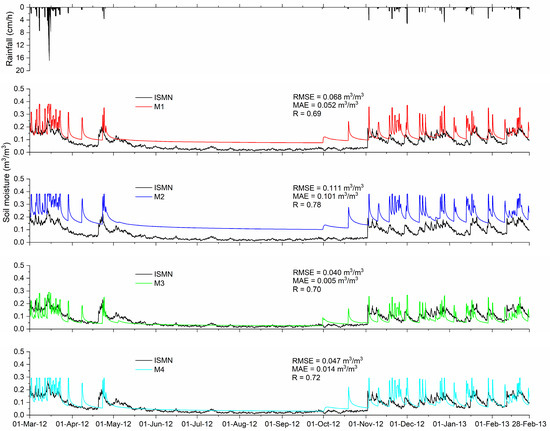

To calibrate the HDRUS-1D model, we used a five-step process (see Section 2.2.3). This section details the results of the five-step process. Initially, we considered the model runs (estimated soil moisture) using the input parameters obtained for the corresponding soil textures in this study (sandy loam and loamy sand). Model results with the input parameter values obtained from the HYDRUS catalogue (M1) and the ROSETTA catalogue (M2) are provided in Figure 2. For initial estimates (no optimization), we found the better (RMSE = 0.068 m3/m3, MAE = 0.052 m3/m3, and R = 0.69, respectively) performance of the model M1 over M2 (RMSE = 0.111 m3/m3, MAE =0.101 m3/m3, and R = 0.78, respectively) in representing the ISMN soil moisture.

Figure 2.

Measure precipitation (BoM) and soil moisture estimates from the four versions (M1, M2, M3, and M4) of the HYDRUS-1D during the calibration period.

Then the initial estimates from M1 were used for parameter optimization, providing the model M3 outputs (Figure 2). A significant improvement was seen in replicating the ISMN soil moisture because of this optimization, as depicted by the efficiency evaluation metrics (RMSE = 0.040 m3/m3, MAE = 0.005 m3/m3, and R = 0.70, respectively) over the model M1. Dynamics of the ISMN soil moisture were well captured by the model M3 using these optimized parameters (Figure 2). To assess the impact of on these optimized parameters, soil moisture was obtained using the model M4 (same optimized parameters for the model M3 except , which was used from model M2). These soil moisture estimates depicted a weaker match against ISMN soil moisture (RMSE = 0.047 m3/m3, MAE = 0.014 m3/m3, and R = 0.72, respectively) as compared to the model M3 (RMSE = 0.040 m3/m3, MAE = 0.005 m3/m3, and R = 0.70, respectively). A key difference between the models M3 and M4 in terms of soil moisture behavior was the overestimation of peak soil moisture values with the model M4. Owing to its superior performance, the model M3 was considered as calibrated and was used for the rest of the analysis.

3.1.2. Model Calibration

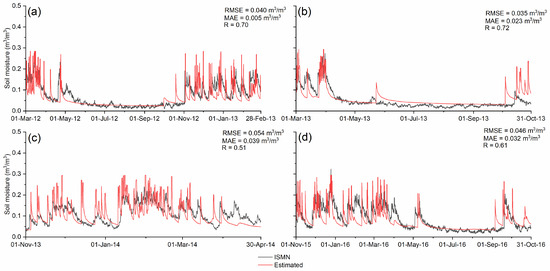

The HYDRUS-1D was able to reproduce the ISMN soil moisture with good accuracy, as depicted by efficiency evaluation metrics values, i.e., RMSE = 0.040 m3/m3, MAE = 0.005 m3/m3, and R = 0.70, respectively (Figure 3) during the calibration period (March 2012 to February 2013). This period consisted of two environmental conditions, i.e., wet and dry, impacting on the soil moisture conditions. During the calibration period, the HYDRUS-1D was able to capture the dynamics of soil moisture in periods with no rainfall (low soil moisture) and in periods depicting episodic rainfall events. Input parameters (optimized) for sandy loam and loamy sand from the model M3 are provided in the Supplementary Materials (Table S1).

Figure 3.

Soil moisture estimates from calibrated HYDRUS-1D model: (a) During calibration period; (b) first validation period; (c) second validation period; (d) third validation period.

3.1.3. Model Validation

The HYDRUS-1D developed during the calibration process was then tested for independent validation periods (Figure 3). Three periods were chosen, representing dry, wet, and a combination (full year) of dry and wet environmental conditions. During the first validation period (dry), the HYDRUS-1D was able to reproduce the ISMN soil moisture with an acceptable accuracy as depicted by the efficiency evaluation metrics (RMSE = 0.035 m3/m3, MAE = 0.023 m3/m3, and R = 0.72, respectively). During the second validation period (wet), the HYDRUS-1D was able to reproduce the ISMN soil moisture with an RMSE value of 0.054 m3/m3, MAE value of 0.039 m3/m3, and R value of 0.51, respectively, and for the third validation period (wet and dry), the HYDRUS-1D was able to reproduce the ISMN soil moisture with an acceptable accuracy as well (RMSE = 0.046 m3/m3, MAE = 0.032 m3/m3, and R = 0.61, respectively).

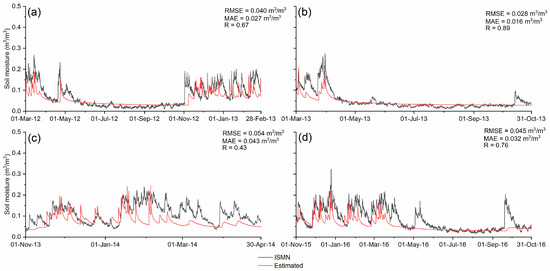

3.2. Estimated Soil Moisture with CHRS-PERSIANN

The previously developed HDYRUS-1D was also used to estimate the soil moisture with the CHRS-PERSIANN precipitation (Figure 4) for the same four periods used earlier. The HDYRUS-1D was able to reproduce the ISMN soil moisture with good accuracy during the calibration period with an RMSE = 0.040 m3/m3, MAE = 0.027 m3/m3, and R = 0.67, respectively. During the first validation period, the model was able to reproduce the ISMN soil moisture with an RMSE value of 0.028 m3/m3, MAE value of 0.016 m3/m3, and R value of 0.89, respectively. During the second validation period, the model was able to reproduce the ISMN soil moisture with an RMSE value of 0.054 m3/m3, MAE value of 0.043 m3/m3, and R value of 0.43, respectively. For the third validation period, the HDYRUS-1D was able to reproduce the ISMN soil moisture with an RMSE value of 0.045 m3/m3, MAE value of 0.032 m3/m3, and R value of 0.76, respectively.

Figure 4.

Soil moisture estimates from the calibrated HYDRUS-1D model with CHRS-PERSIANN inputs: (a) During calibration period; (b) first validation period; (c)second validation period; (d) third validation period.

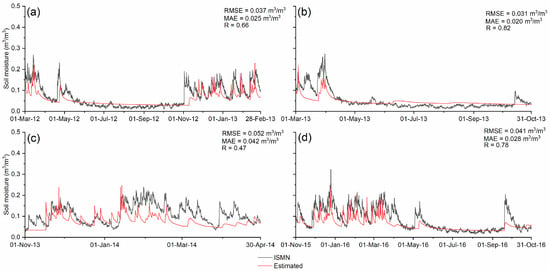

3.3. Estimated Soil Moisture with CHRS-CCS

The HDYRUS-1D was used to estimate the soil moisture with precipitation data from the CHRS-CCS for the same four periods used in model calibration and validation with BoM data (Figure 5). The HDYRUS-1D was able to reproduce the ISMN soil moisture with good accuracy during the calibration period with an RMSE value of 0.037 m3/m3, MAE value of 0.025 m3/m3, and R value of 0.66, respectively. During the first validation period, the HDYRUS-1D was able to reproduce the ISMN soil moisture with an RMSE value of 0.031 m3/m3, MAE value of 0.020 m3/m3, and R value of 0.82, respectively. During the second validation period, the HDYRUS-1D was able to reproduce the ISMN soil moisture with an RMSE value of 0.052 m3/m3, MAE value of 0.042 m3/m3, and R value of 0.47, respectively. For the third validation period, the HDYRUS-1D was able to reproduce the ISMN soil moisture with an RMSE value of 0.041 m3/m3, MAE value of 0.028 m3/m3, and R value of 0.78, respectively.

Figure 5.

Soil moisture estimates from the calibrated HYDRUS-1D model with CHRS-CCS inputs: (a) During calibration period; (b) first validation period; (c) second validation period; (d) third validation period.

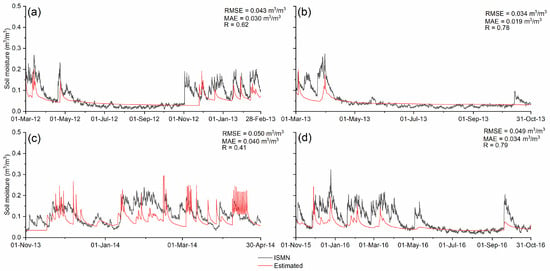

3.4. Estimated Soil Moisture with CHRS-PDIR-Now

The HYDRUS-1D was used to estimate the soil moisture with precipitation data from the CHRS-PDIR-Now for the same four periods used in model calibration and validation with BoM data (Figure 6). The HYDRUS-1D was able to reproduce the ISMN soil moisture with an RMSE value of 0.043 m3/m3, MAE value of 0.030 m3/m3, and R value of 0.62, respectively. During the first validation period, the HDYRUS-1D was able to reproduce the ISMN soil moisture with an RMSE value of 0.034 m3/m3, MAE value of 0.019 m3/m3, and R value of 0.78. During the second validation period, the HDYRUS-1D was able to reproduce the ISMN soil moisture with an RMSE value of 0.050 m3/m3, MAE value of 0.040 m3/m3, and R value of 0.41, respectively. For the third validation period, the HDYRUS-1D was able to reproduce the ISMN soil moisture with an RMSE value of 0.091 m3/m3, MAE value of 0.034 m3/m3, and R value of 0.79, respectively.

Figure 6.

Soil moisture estimates from the calibrated HYDRUS-1D model with CHRS-PDIR-Now inputs: (a) During calibration period; (b) first validation period; (c) second validation period; (d) third validation period.

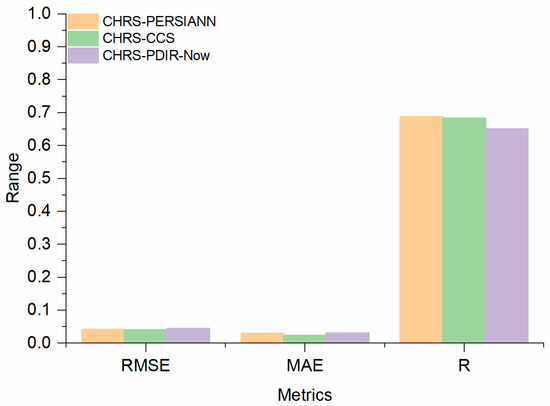

3.5. Overall Performance of the CHRS-PERSIANN, CHRS-CCS, and CHRS-PDIR-Now

There were three remotely sensed products considered in this study to estimate the IMSN soil moisture through the calibrated HYDRUS-1D model. Overall, the CHRS-CCS was found to be the optimum product in terms of estimating the ISMN soil moisture (Figure 5 and Figure 7). During the four analyzed periods (calibration and the three validation periods, see Section 2.2.4), an average RMSE value of 0.040 m3/m3 and an average MAE value of 0.029 m3/m3 between ISMN and the HYDRUS-estimated soil moisture was observed using the CHRS-CCS precipitation data, which was lower than the CHRS-PERSIANN (an average value of RMSE of 0.042 m3/m3 and an average MAE value of 0.030 m3/m3) and the CHRS-PDIR-Now (an average RMSE value of 0.044 m3/m3 and average MAE value of 0.031 m3/m3). In terms of average R across all four analyzed periods, the CHRS-CCS depicted a value of 0.68, which was higher than the CHRS-PDIR-Now (0.65) but slightly lower than the CHRS-PERSIANN (0.69).

Figure 7.

Overall performance of CHRS-PERSIANN, CHRS-CCS, and CHRS-PDIR-Now in estimating the soil moisture through the HYDRUS-1D.

4. Discussion

The HYDRUS-1D model was developed by incorporating a comprehensive uncertainty analysis. During the calibration process, parameter optimization is often performed to achieve the best set of input parameters that can reliably replicate measurements (e.g., soil moisture). In the HYDRUS-1D, appropriate initial estimates (of the parameters to be optimized) are required. These estimates are generally acquired from the existing sources of information (databases or literature, for instance). While different databases can be used to get these estimates, it is challenging to select one (as the soil hydraulic properties and hydraulic conductivities in particular can exhibit large differences for the same soil textures). Therefore, we used multiple sources (HYDRUS catalogue and ROSETTA catalogue) to determine initial estimates and found that optimized parameters based on initial estimates of HYDRUS catalogue yielded the highest match between the model estimated and the IMSN soil moisture measurements. Lower performance of initial estimates from ROSETTA catalogue might be attributed to the fact that calibration data set in ROSETTA is based on 2134 samples for water retention and 1306 samples for [46] which were obtained from multiple sources, soils, and climate zones of the northern hemisphere (the USA and Europe) and may not be suitable other locations (e.g., Northern Territory, Australia). Furthermore, for our particular study region, values in the initial estimates from the ROSETTA catalogue were lower as compared to the HYDRUS catalogue, which indicates slower drainage of soils, which is contrary to the characteristics of the soil type in the study region (soils are well drained and highly permeable). Therefore, we recommend the cautious use of initial parameter estimates from the ROSETTA catalogue, particularly the , (only the model where soil texture type is used an input, as other models were not tested in this study) particularly in the NT context. On the other hand, the use of the HYDRUS catalogue is suggested to estimate initial parameter values.

The results of this study (estimated soil moisture from the calibrated HYDRUS-1D model) are in line with the previous findings where similar results were reported. Stafford et al. [47] reported an RMSE value of 0.034 m3/m3 and 0.051 m3/m3 for calibration and validation datasets, respectively. Kodešova et al. [48] similarly reported RMSE values ranging between 0.01 m3/m3 and 0.05 m3/m3. In terms of efficiency evaluation metrics, it was observed in the study that evaluation metrics such as Pearson correlation coefficient (R) should not be relied upon solely; rather, it should be considered in conjunction with other metrics (e.g., RMSE and MAE) and human assessment (visual interpretation).

During the calibration period with BoM precipitation data, while peaks and lows in soil moisture were fairly captured by the model, there were slight overestimations of the soil moisture, particularly before a large spike in soil moisture when it jumped from 0.05 m3/m3 to 0.25 m3/m3 in a short time (May 2012), similar patterns were noticed during the third validation period as well. For the first validation period, peak soil moisture was slightly overestimated, and both overestimations and underestimations were seen in the second validation period.

While overestimation of the ISMN soil moisture was observed with BoM precipitation during calibration, with the CHRS-PERSIANN precipitation data, peak soil moisture was fairly captured by the model. Significant underestimation of the high soil moisture values was observed during the second validation period. While lower values of the soil moisture were fairly replicated by the CHRIS-PERSIANN precipitation, underestimation of high soil moisture continued in the validation periods as well. With the CHRS-CCS precipitation data, the peaks were captured even better than the BoM precipitation and instead, an underestimation of high soil moisture was observed. Better MAE values for the measured and the estimated soil moisture with the CHRS-CCS during the calibration period, as compared to the BoM precipitation might be attributed to this factor. For the CHRS-PDIR-Now precipitation data, there was significant underestimation of the peak soil moisture, and even in instances when the peak soil moisture was captured, it was not as good as with CHRIS-CCS precipitation data. While lower values of the soil moisture were fairly replicated by the CHRIS-PDIR-Now precipitation data, underestimation of high soil moisture continued in the validation periods as well. Results of this study indicate the characteristics underestimation of soil moisture with CHRS-PERSIANN, CHRS-CCS, and CHRS-PDIR-Now precipitation data. This has been shown by other studies as well, where either a mixture of under(over)estimation was shown by PERSIANN family products, or a significant underestimation was exhibited [49].

In terms of statistical measures and visual inspection, the estimated soil moisture with the integration of the HYDRUS-1D model with the CHRS-CCS precipitation data revealed the better overall performance (see Section 3.3 and Section 3.5) in replicating the ISMN soil moisture over the other two data products (CHRS-PERSIANN and CHRS-PDIR-Now). Similar results were reported by [50] where the CHRS-CCS was successfully used for soil moisture modelling in eastern Spain. The CHRS-CCS has also been considered as best for high-resolution and real-time applications [51] and it is also the most in-demand data from CHRS data portal [52] among family of PERSIANN products considering its densest spatial resolution. One of the key qualities of the CHRS-CCS that might be attributed to its better performance in estimating hourly soil moisture is the brief time span between data retrieval to output, which can be crucial for modelling and predictions [52]. While the CHRS-CCS has better performance for the given region, necessary evaluations should be carried out when applying the data to other locations, as geographical, climatological, and environmental conditions in a particular location might impact the accuracy of precipitation data [49].

A key limitation of the study is the absence of measurement data to determine the input parameters for the HYDRUS-1D model. Either complete or partial measurements to determine input soil hydraulic properties can be employed in future which can potentially increase the model’s performance. While the scope of the current study was limited to well-drained and highly permeable soils of the Northern Territory, Australia, the parameters used in the study might be helpful in other areas with similar soil characteristics.

5. Conclusions

The HYDRUS-1D was developed to estimate the soil moisture in the state of Northern Territory, Australia. Model development was based on the ISMN soil moisture data (measurement data), and a comprehensive uncertainty analysis was incorporated in the model calibration process. Impact of initial input parameter estimates (from different sources) on the model’s ability to reproduce the IMSN soil moisture was addressed in the model calibration process. The developed model was able to reproduce the ISMN soil moisture with good accuracy, i.e., during the calibration period (RMSE = 0.040 m3/m3, MAE = 0.005 m3/m3, and R = 0.70, respectively), and during the three validation periods, i.e., the first validation period (RMSE = 0.035 m3/m3, MAE = 0.023 m3/m3, and R = 0.72, respectively), the second validation period (RMSE = 0.054 m3/m3, MAE = 0.039 m3/m3, and R = 0.51, respectively), and the validation period (RMSE = 0.046 m3/m3, MAE = 0.032 m3/m3, and R = 0.61, respectively), respectively. The CHRS-CCS, CHRS-CDR, and CHRS-PERSIANN precipitation data were assessed to explore their performance in simulating the ISMN soil moisture. The CHRS-CCS showed the best performance in simulating the ISMN soil moisture with an average RMSE value of 0.040 m3/m3, average MAE value of 0.029 m3/m3, and an average R value of 0.68, respectively. This study will be helpful in long-term estimations of the soil moisture, thus allowing better understanding of the soil moisture dynamics and soil water balance dynamics in the state of Northern Territory, Australia. Results of this study might be helpful in other areas of similar soil characteristics (well drained and highly permeable sandy loam and loamy sand) as well.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/rs17223723/s1, Figure S1: Hourly precipitation from BoM: (a) During calibration period; (b) first validation period; (c) second validation period; (d) third validation period; Figure S2: Hourly precipitation from CHRS-PERSIANN: (a) During calibration period; (b) first validation period; (c) second validation period; (d) third validation period; Figure S3: Hourly precipitation from CHRS-CCS: (a) During calibration period; (b) first validation period; (c) second validation period; (d) third validation period; Figure S4: Hourly precipitation from CHRS-PDIR-Now: (a) During calibration period; (b) first validation period; (c) second validation period; (d) third validation period; Table S1: Input parameters from the model M3.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.U.; methodology, M.U.; software, M.U.; validation, M.U.; formal analysis, M.U. and C.E.N.; investigation, M.U. and C.E.N.; resources, M.U. and C.E.N.; data curation, M.U.; writing—original draft preparation, M.U.; writing—review and editing, M.U. and C.E.N.; funding acquisition, M.U. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data availability is subjected to approval.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Meng, F.; Wang, J.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, Z. Quantification of soil water content by machine learning using enhanced high-resolution ERT. J. Hydrol. 2024, 643, 131994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petropoulos, G.P.; Griffiths, H.M.; Dorigo, W.; Xaver, A.; Gruber, A. Surface soil moisture estimation: Significance, controls, and conventional measurement techniques. In Remote Sensing of Energy Fluxes and Soil Moisture Content; Petropoulos, G.P., Ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2013; pp. 29–48. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy, A.; Foley, J.; Raedts, P.; Hills, J. Field evaluation of automated site-specific irrigation for cotton and perennial ryegrass using soil-water sensors and Model Predictive Control. Agric. Water Manag. 2023, 277, 108098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwevedi, A.; Kumar, P.; Kumar, P.; Kumar, Y.; Sharma, Y.K.; Kayastha, A.M. Soil sensors: Detailed insight into research updates, significance, and future prospects. In New Pesticides and Soil Sensors; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017; pp. 561–594. [Google Scholar]

- Fuentes, I.; Padaran, J.; Vervoort, S.W. Towards near real-time national-scale soil water content monitoring using data fusion as a downscaling alternative. J. Hydrol. 2022, 609, 127705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Q.; Tang, C.-S.; Lin, Z.-Z.; Tian, B.-G.; Shi, B. Measurement of water content at bare soil surface with infrared thermal imaging technology. J. Hydrol. 2022, 615, 128715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasheed, M.W.; Tang, J.; Sarwar, A.; Shah, S.; Saddique, N.; Khan, M.U.; Imran Khan, M.; Nawaz, S.; Shamshiri, R.R.; Aziz, M.; et al. Soil moisture measuring techniques and factors affecting the moisture dynamics: A comprehensive review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorigo, W.; Himmelbauer, I.; Aberer, D.; Schremmer, L.; Petrakovic, I.; Zappa, L.; Preimesberger, W.; Xaver, A.; Annor, F.; Ardö, J.; et al. The International Soil Moisture Network: Serving Earth system science for over a decade. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2021, 25, 5749–5804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorigo, W.A.; Xaver, A.; Vreugdenhil, M.; Gruber, A.; Hegyiová, A.; Sanchis-Dufau, A.D.; Zamojski, D.; Cordes, C.; Wagner, W.; Drusch, M. Global Automated Quality Control of In Situ Soil Moisture Data from the International Soil Moisture Network. Vadose Zone J. 2013, 12, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, L.A. Capillary conduction of liquids through porous mediums. Physics 1931, 1, 318–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šimůnek, J.; van Genuchten, M.T.; Šejna, M. Development and applications of the HYDRUS and STANMOD software packages and related codes. Vadose Zone J. 2008, 7, 587–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šimůnek, J.; Jarvis, N.J.; van Genuchten, M.; Gärdenäs, A. Review and comparison of models for describing non-equilibrium and preferential flow and transport in the vadose zone. J. Hydrol. 2003, 272, 14–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dam, J.C.; Huygen, J.; Wesseling, J.G.; Feddes, R.A.; Kabat, P.; Van Walsum, P.E.V.; Groenendijk, P.; Van Diepen, C.A. Theory of SWAP Version 2.0; Simulation of Water Flow, Solute Transport and Plant Growth in the Soil-Water-Atmosphere-Plant Environment (No.71); DLO Winand Staring Centre: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Van Genuchten, M.T. A closed-form equation for predicting the hydraulic conductivity of unsaturated soils. Soil. Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1980, 44, 892–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, Y.; Ghanbarian-Alavijeh, B.; Liaghat, A.M.; Shorafa, M. Evaluation of pedotransfer functions for estimating soil water retention curve of saline and saline-alkali soils of Iran. Pedosphere 2011, 21, 230–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanzari, S.; Hachicha, M.; Bouhlila, R. Laboratory method for estimating water retention properties of unsaturated soil. Walailak J. Sci. Technol. (WJST) 2012, 9, 361–367. [Google Scholar]

- Wesseling, J.G.; Ritsema, C.J.; Stolte, J.; Oostindie, K.; Dekker, L.W. Describing the soil physical characteristics of soil samples with cubical splines. Transp. Porous Media 2008, 71, 289–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanbarian-Alavijeh, B.; Liaghat, A.; Huang, G.H.; Van Genuchten, M.T. Estimation of the van Genuchten soil water retention propertie from soil textural data. Pedosphere 2010, 20, 456–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaap, M.G.; Leij, F.J.; Van Genuchten, M.T. Rosetta: A computer program for estimating soil hydraulic parameters with hierarchical pedotransfer functions. J. Hydrol. 2001, 251, 163–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carsel, R.F.; Parrish, R.S. Developing joint probability distributions of soil water retention characteristics. Water Resour. Res. 1988, 24, 755–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, M.F.; Dietrich, O.; Gerke, H.H.; Merz, C. Modeling water flow and volumetric water content in a degraded peat comparing unimodal with bimodal porosity and flux with pressure head boundary condition. Vadose Zone J. 2024, 23, 20328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fournel, J.; Forquet, N.; Molle, P.; Grasmick, A. Modeling constructed wetlands with variably saturated vertical subsurface-flow for urban stormwater treatment. Ecol. Eng. 2013, 55, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, M.; Chua, L.H.; Irvine, K.N.; Teang, L. Numerical modelling of vadose zone flow for a shallow groundwater wetland using HYDRUS-1D. Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 2025, 11, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, M.; Ndehedehe, C.E.; Ahmad, B.; Manzanas, R.; Adeyeri, O.E. Modeling streamflow using multiple precipitation products in a topographically complex catchment. Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 2022, 8, 1875–1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsumaiti, T.S.; Hussein, K.; Ghebreyesus, D.T.; Sharif, H.O. Performance of the CMORPH and GPM IMERG Products over the United Arab Emirates. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huffman, G.; Bolvin, D.; Braithwaite, D.; Hsu, K.-L.; Joyce, R.; Kidd, C.; Nelkin, E.J.; Sorooshian, S.; Tan, J.; Xie, P. NASA Global Precipitation Measurement (GPM) Integrated Multi-SatellitE Retrievals for GPM (IMERG); Global Precipitatoin Measurement; NASA: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; pp. 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, P.; Ombadi, M.; Sorooshian, S.; Hsu, K.; AghaKouchak, A.; Braithwaite, D.; Ashouri, H.; Thorstensen, A.R. The PERSIANN Family of Global Satellite Precipitation Data: A Review and Evaluation of Products. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2018, 22, 5801–5816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; Huffman, G.J.; Bolvin, D.T.; Nelkin, E.J. IMERG V06: Changes to the Morphing Algorithm. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 2019, 36, 2471–2482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, M.; Ndehedehe, C.E.; Farah, H.; Ahmad, B.; Wong, Y.; Adeyeri, O.E. Application of a conceptual hydrological model for streamflow prediction using multi-source precipitation products in a semi-arid river basin. Water 2022, 14, 1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joyce, R.J.; Janowiak, J.E.; Arkin, P.A.; Xie, P. CMORPH: A Method That Produces Global Precipitation Estimates from Passive Microwave and Infrared Data at High Spatial and Temporal Resolution. J. Hydrometeorol. 2004, 5, 487–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorooshian, S.; Hsu, K.-L.; Gao, X.; Gupta, H.V.; Imam, B.; Braithwaite, D. Evaluation of PERSIANN System Satellite-Based Estimates of Tropical Rainfall. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2000, 81, 2035–2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashouri, H.; Hsu, K.-L.; Sorooshian, S.; Braithwaite, D.K.; Knapp, K.R.; Cecil, L.D.; Nelson, B.R.; Prat, O.P. PERSIANN-CDR: Daily Precipitation Climate Data Record from Multisatellite Observations for Hydrological and Climate Studies. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2015, 96, 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, K.; Gao, X.; Sorooshian, S.; Gupta, H.V. Precipitation Estimation from Remotely Sensed Information Using Artificial Neural Networks. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 1997, 36, 1176–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zreda, M.; Desilets, D.; Ferre, T.P.A.; Scott, R.L. Measuring soil moisture content non-invasively at intermediate spatial scale using cosmic-ray neutrons. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2008, 35, L21402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zreda, M.; Shuttleworth, W.J.; Zeng, X.; Zweck, C.; Desilets, D.; Franz, T.; Rosolem, R. COSMOS: The COsmic-Ray Soil Moisture Observing System. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2012, 16, 4079–4099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desilets, D.; Zreda, M.; Ferre, T. Nature’s neutron probe: Landsurface hydrology at an elusive scale with cosmic rays. Water Resour. Res. 2010, 46, W11505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mualem, Y. A new model for predicting the hydraulic conductivity of unsaturated porous media. Water Resour. Res. 1976, 12, 513–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirmeyer, P.A.; Wu, J.; Norton, H.E.; Dorigo, W.A.; Quiring, S.M.; Ford, T.W.; Santanello, J.A., Jr.; Bosilovich, M.G.; Ek, M.B.; Koster, R.D.; et al. Confronting weather and climate models with observational data from soil moisture networks over the United States. J. Hydrometeorol. 2016, 17, 1049–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simůnek, J.; van Genuchten, M.T.; Sejna, M. The HYDRUS-1D Software Package for Simulating the One-Dimensional Movement of Water, Heat and Multiple Solutes in Variably-Saturated Media, 4th ed.; HYDRUS Software Series 3; Department of Environmental Sciences, University of California: Riverside, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Šimůnek, J.; Hopmans, J.W. 1.7 parameter optimization and nonlinear fitting. In Methods of Soil Analysis: Part 4 Physical Methods; American Society of Agronomy: Madison, WI, USA, 2002; Volume 5, pp. 139–157. [Google Scholar]

- Konikow, L.F.; Bredehoeft, J.D. Ground-water models cannot be validated. Adv. Water Resour. 1992, 15, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šimunek, J.; De Vos, J.A. Inverse optimization, calibration and validation of simulation models at the field scale. In Modelling of Transport Processes in Soils 1999; Wageningen Academic: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 1999; pp. 431–445. [Google Scholar]

- Marquardt, D.W. An algorithm for least-squares estimation of nonlinear parameters. SIAM J. Appl. Math. 1963, 11, 431–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, E.K.; Roberts, W.; Nelsen, B.; Williams, G.P.; Nelson, E.J.; Ames, D.P. Introductory overview: Error metrics for hydrologic modelling—A review of common practices and an open source library to facilitate use and adoption. Environ. Model. Softw. 2019, 119, 32–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zha, X.; Zhu, W.; Han, Y.; Lv, A. Enhancing root-zone soil moisture estimation using Richards’ equation and dynamic surface soil moisture data. Agric. Water Manag. 2025, 312, 109460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaap, M.G.; Leij, F.J. Database Related Accuracy and Uncertainty of Pedotransfer Functions. Soil Sci. 1998, 163, 765–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stafford, M.J.; Holländer, H.M.; Dow, K. Estimating groundwater recharge in the assiniboine delta aquifer using HYDRUS-1D. Agric. Water Manag. 2022, 267, 107514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodešová, R.; Fér, M.; Klement, A.; Nikodem, A.; Teplá, D.; Neuberger, P.; Bureš, P. Impact of various surface covers on water and thermal regime of Technosol. J. Hydrol. 2014, 519, 2272–2288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, H.; Sadeghi, M.; Golian, S.; Nguyen, P.; Murphy, C.; Sorooshian, S. The application of PERSIANN family datasets for hydrological modeling. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 3675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juglea, S.; Kerr, Y.; Mialon, A.; Lopez-Baeza, E.; Braithwaite, D.; Hsu, K. Soil moisture modelling of a SMOS pixel: Interest of using the PERSIANN database over the Valencia Anchor Station. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2010, 14, 1509–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, K.; Behrangi, A.; Imam, B.; Sorooshian, S. Satellite Rainfall Applications for Surface Hydrology; Gebremichael, M., Hossain, F., Eds.; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany; Tsinghua University Press: Beijing, China, 2010; Chapter 4. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, P.; Shearer, E.J.; Tran, H.; Ombadi, M.; Hayatbini, N.; Palacios, T.; Huynh, P.; Braithwaite, D.; Updegraff, G.; Hsu, K.; et al. The CHRS Data Portal, an easily accessible public repository for PERSIANN global satellite precipitation data. Sci. Data 2019, 6, 180296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).