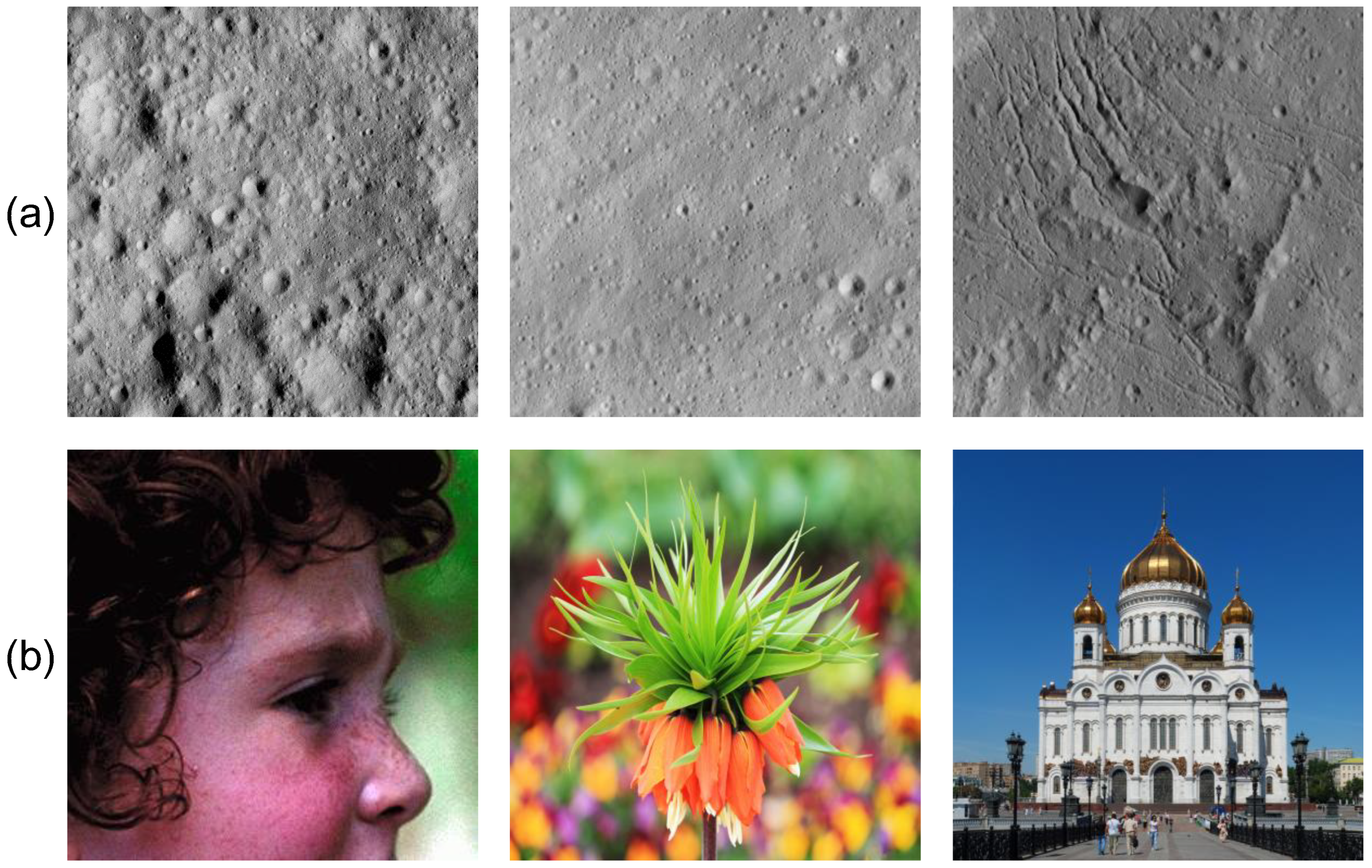

Figure 1.

Examples of Ceres images (a) and natural images (b), demonstrating their different context distributions. These context distinct distributions necessitate domain-specific feature learning mechanisms, as generic natural image priors in natural images may degrade SR performance on planetary remote sensing images.

Figure 1.

Examples of Ceres images (a) and natural images (b), demonstrating their different context distributions. These context distinct distributions necessitate domain-specific feature learning mechanisms, as generic natural image priors in natural images may degrade SR performance on planetary remote sensing images.

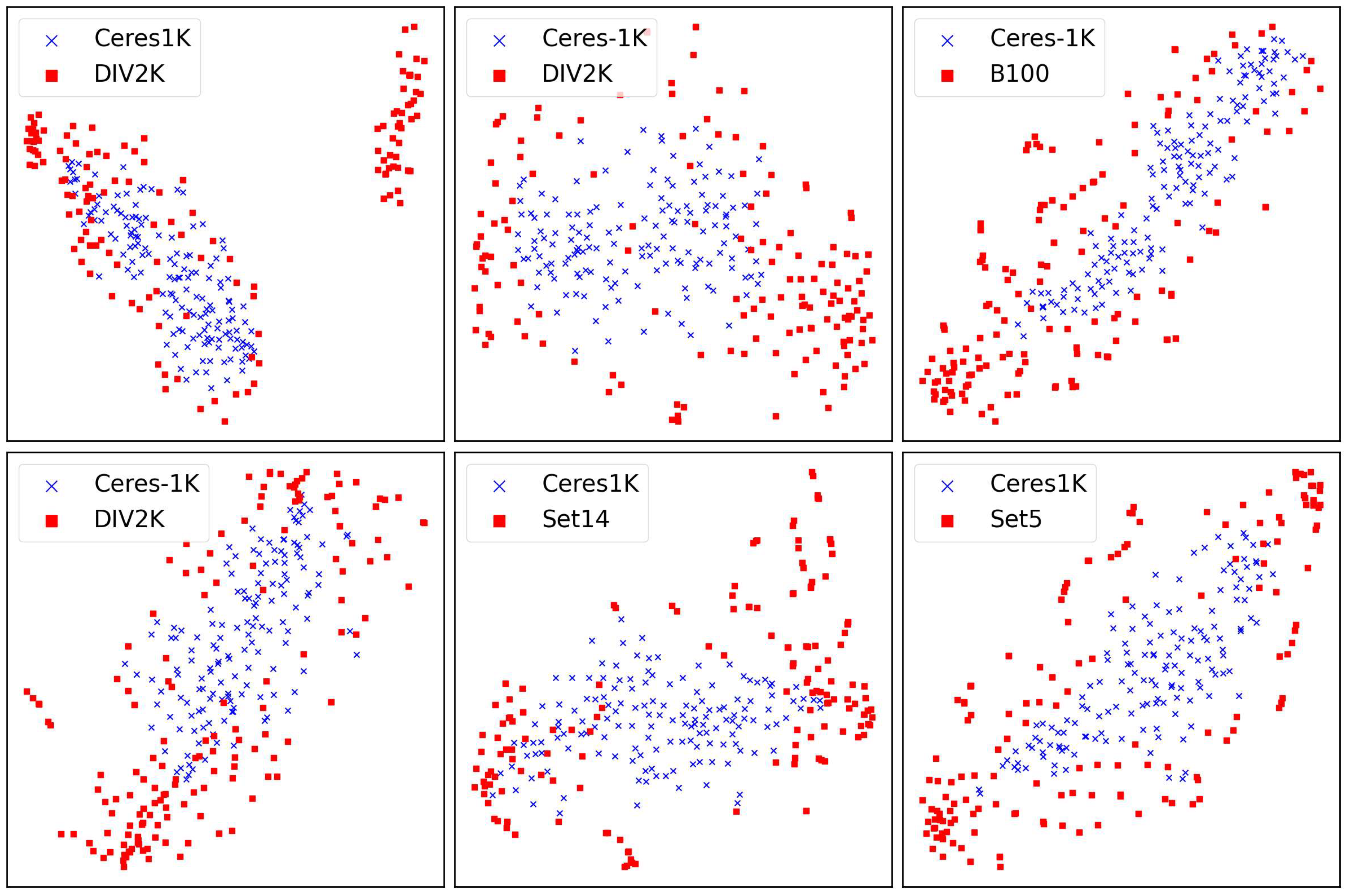

Figure 2.

The t-SNE visualization of image patches from Ceres-1K and widely used natural image datasets. Each scatter plot represents the t-SNE visualization of patches from a randomly selected image. The analysis demonstrates higher regional context homogeneity in Ceres-1K patches compared to natural image patches, quantifying the distinct contextual characteristics of planetary remote sensing images.

Figure 2.

The t-SNE visualization of image patches from Ceres-1K and widely used natural image datasets. Each scatter plot represents the t-SNE visualization of patches from a randomly selected image. The analysis demonstrates higher regional context homogeneity in Ceres-1K patches compared to natural image patches, quantifying the distinct contextual characteristics of planetary remote sensing images.

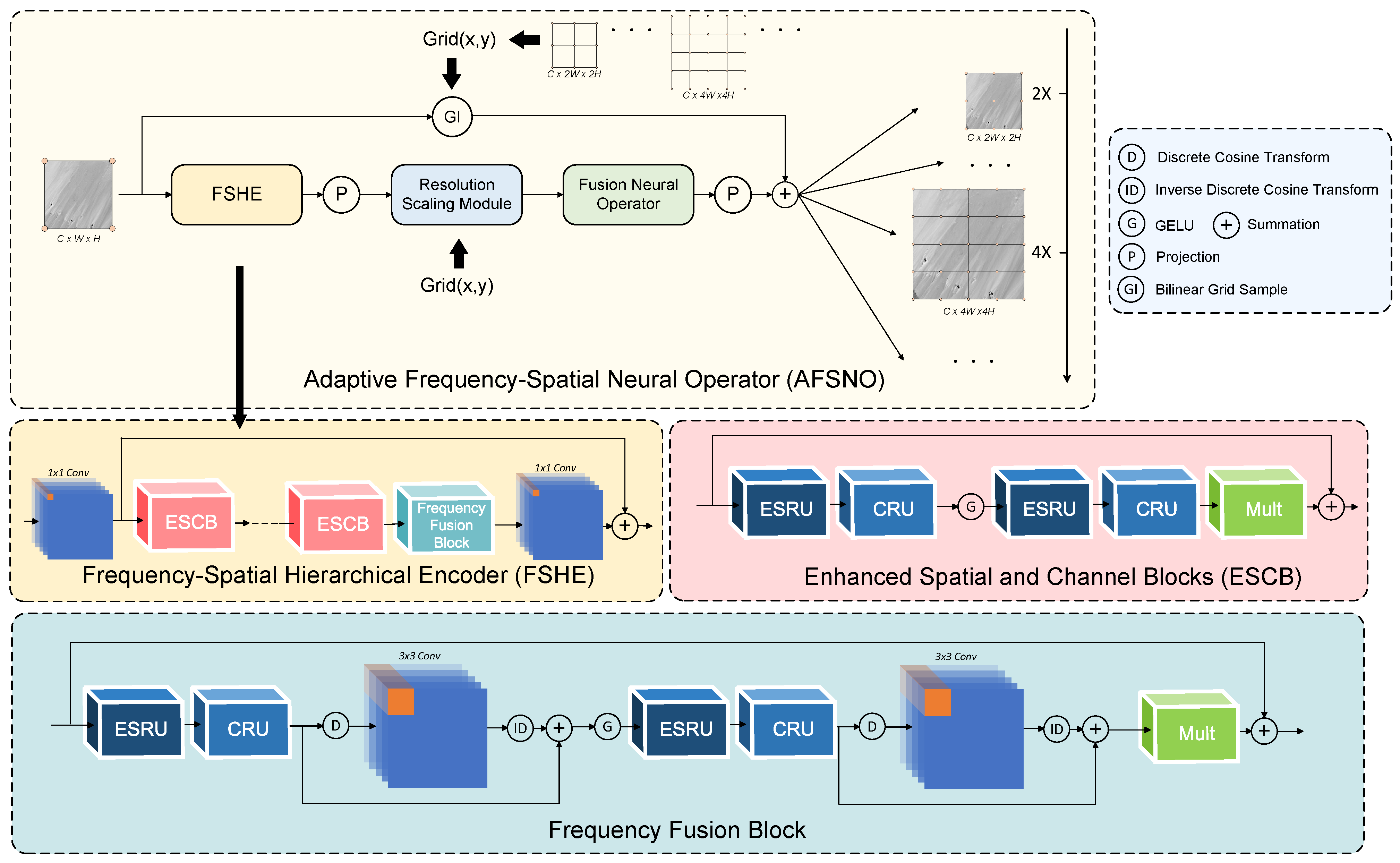

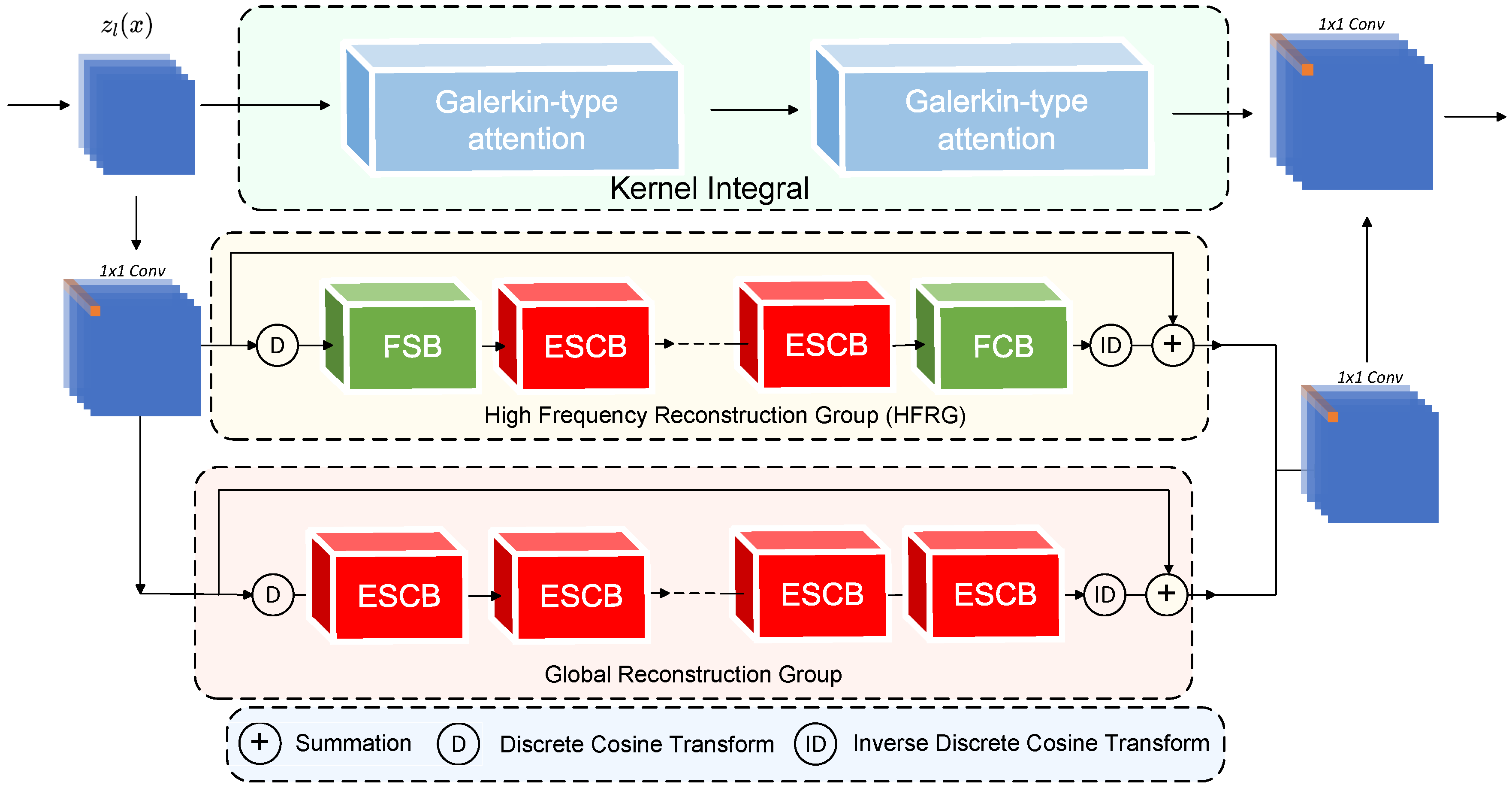

Figure 3.

Architecture of the Adaptive Frequency–Spatial Neural Operator (AFSNO).

Figure 3.

Architecture of the Adaptive Frequency–Spatial Neural Operator (AFSNO).

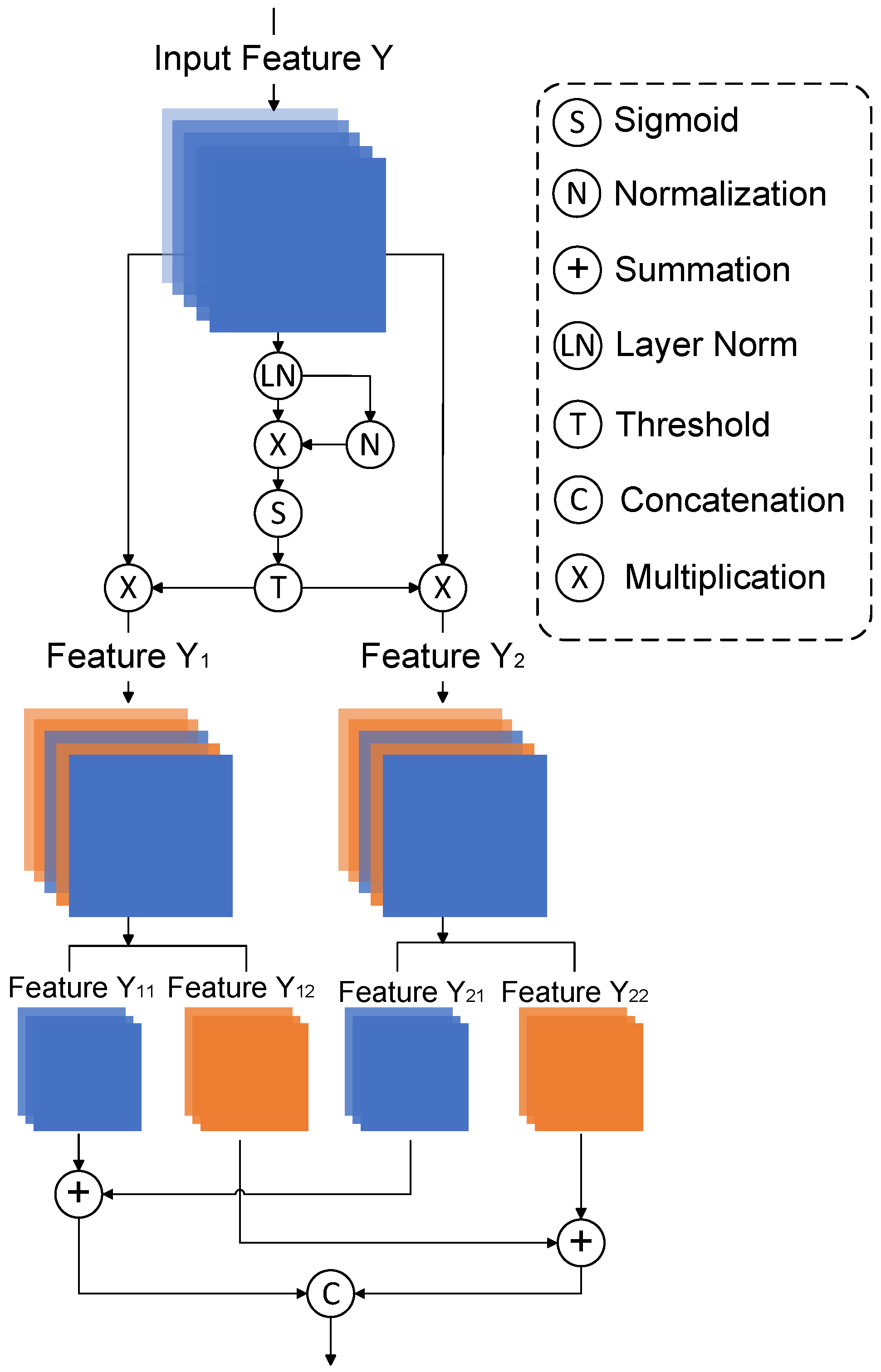

Figure 4.

The architecture of ESRU. The ESCB consists of the CRU and ESRU.

Figure 4.

The architecture of ESRU. The ESCB consists of the CRU and ESRU.

Figure 5.

The architecture of Fusion Neural Operator.

Figure 5.

The architecture of Fusion Neural Operator.

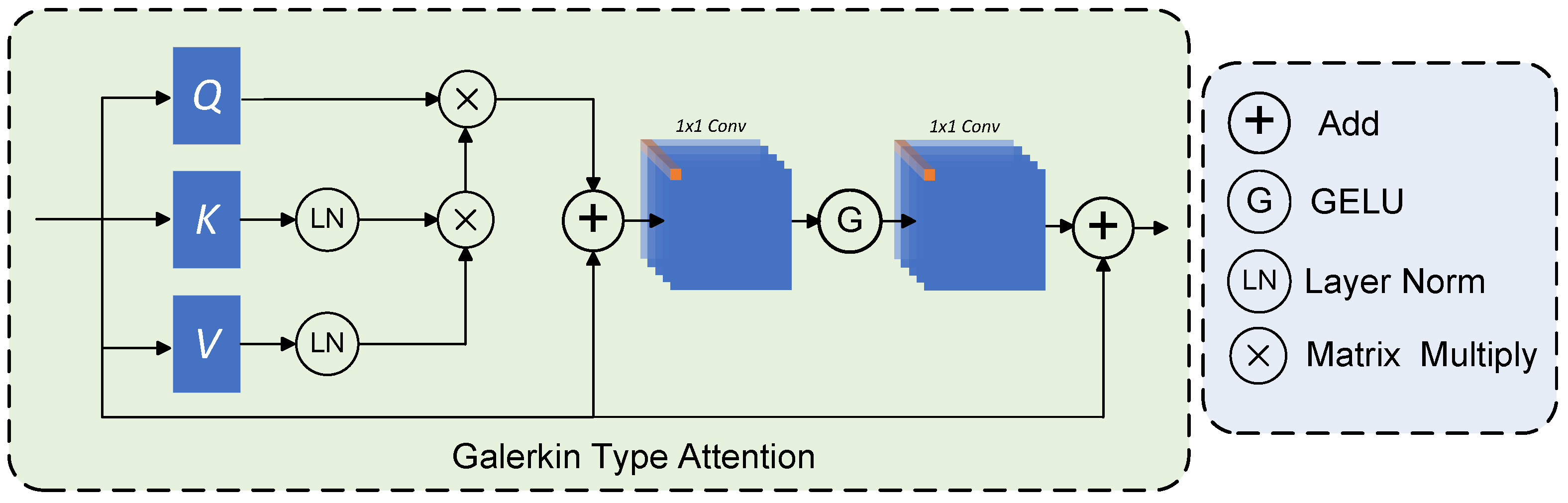

Figure 6.

The architecture of Galerkin-Type Attention.

Figure 6.

The architecture of Galerkin-Type Attention.

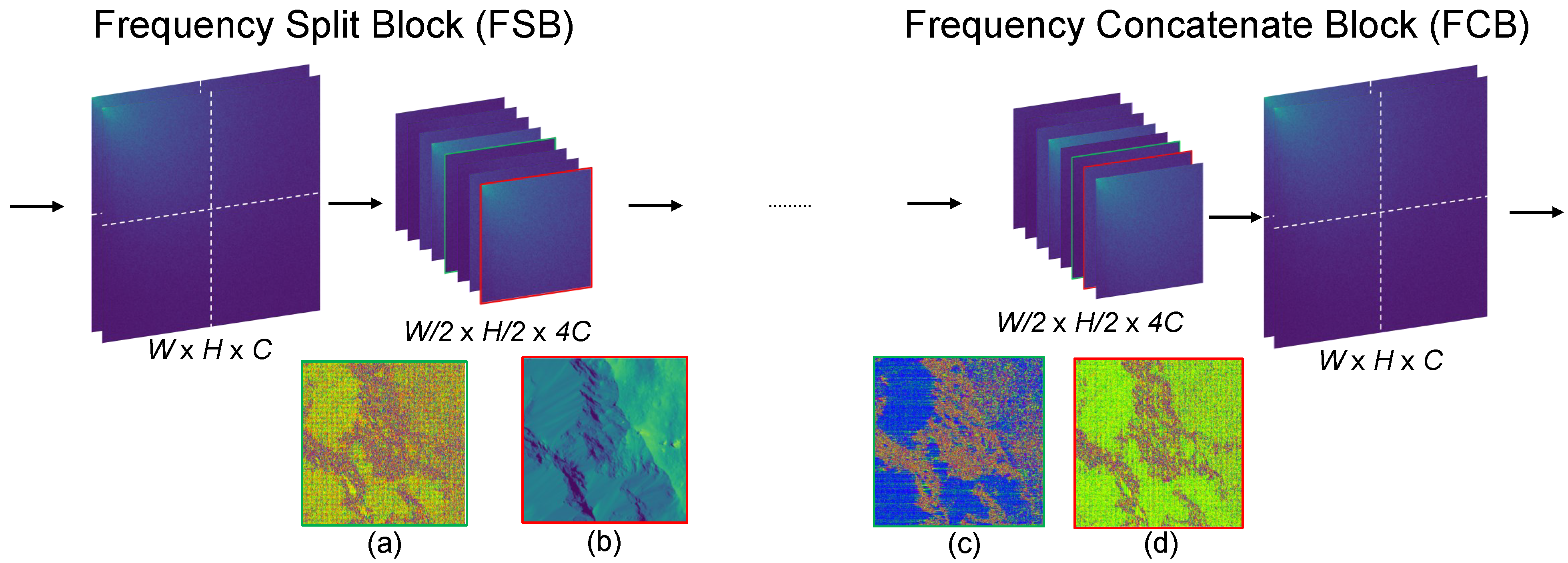

Figure 7.

The architecture of the Frequency Split Block (FSB) and the Frequency Concatenate Block (FCB). These two blocks are designed to separate frequency domain features into high-frequency and low-frequency components by cropping the features. Panels (a–d) illustrate the different frequency information extracted through the frequency split operation.

Figure 7.

The architecture of the Frequency Split Block (FSB) and the Frequency Concatenate Block (FCB). These two blocks are designed to separate frequency domain features into high-frequency and low-frequency components by cropping the features. Panels (a–d) illustrate the different frequency information extracted through the frequency split operation.

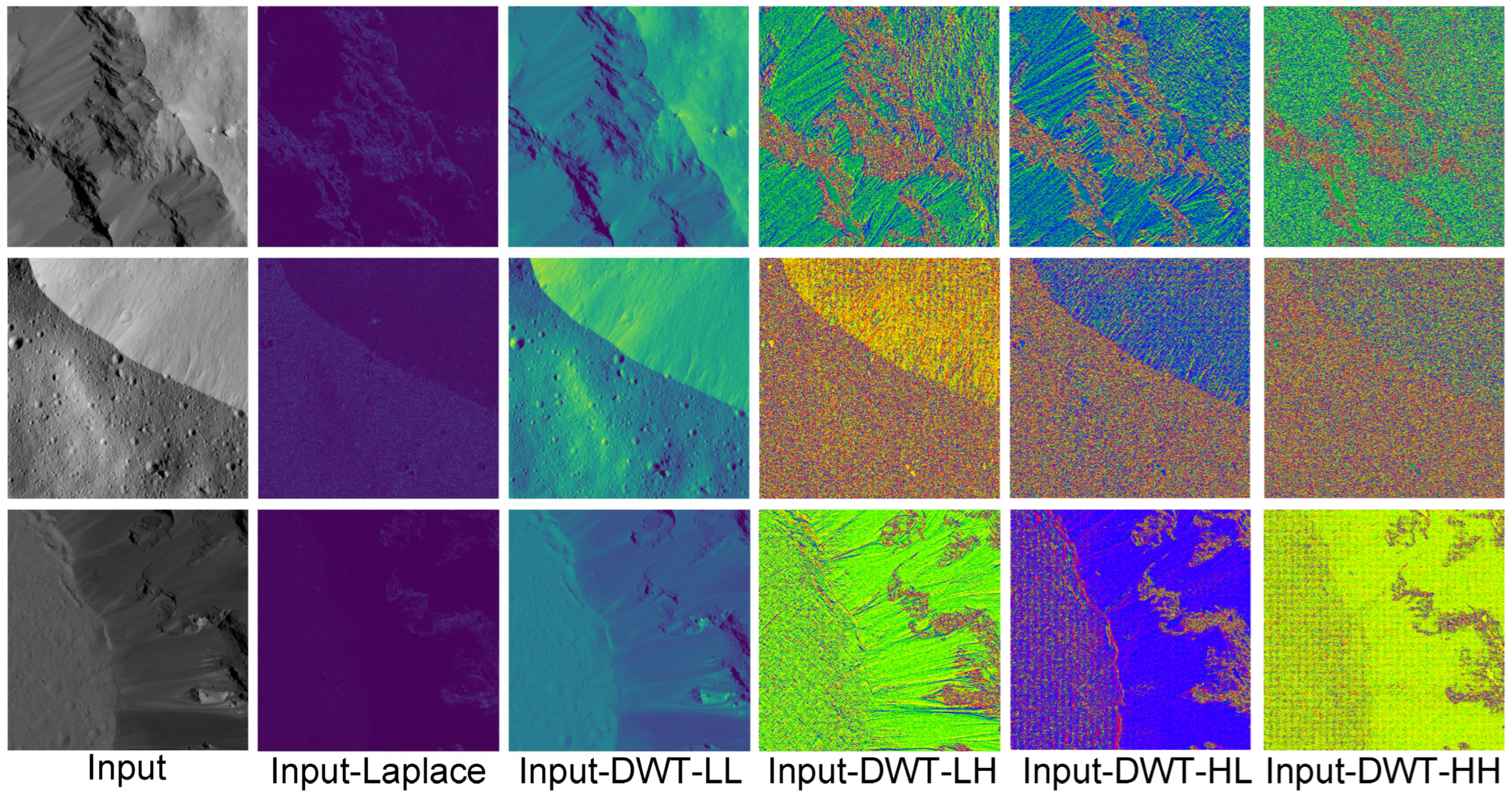

Figure 8.

Visualization of features used in the Frequency Fusion Edge Loss function. Input-Laplace represents input images after applying the Laplace edge operator. The DWT decomposes the input planetary remote sensing image into four subbands: Input-DWT-LL, Input-DWT-HL, Input-DWT-LH, and Input-DWT-HH, all components of the Frequency Fusion Edge Loss Function.

Figure 8.

Visualization of features used in the Frequency Fusion Edge Loss function. Input-Laplace represents input images after applying the Laplace edge operator. The DWT decomposes the input planetary remote sensing image into four subbands: Input-DWT-LL, Input-DWT-HL, Input-DWT-LH, and Input-DWT-HH, all components of the Frequency Fusion Edge Loss Function.

Figure 9.

Examples from the Ceres-1K dataset. The Ceres-1K dataset exhibits rich geological features, such as craters, linear structures, mounds, and domes.

Figure 9.

Examples from the Ceres-1K dataset. The Ceres-1K dataset exhibits rich geological features, such as craters, linear structures, mounds, and domes.

Figure 10.

Qualitative comparison of 4× SR results for different geological features on various planets. (a) Central mound at the south pole on Vesta. (b) Charon’s complexity. (c) Detailed ‘Snowman’ Crater on Vesta. (d) Detailed ’Snowman’ crater on Vesta. (e) Northern hemisphere of Triton, the moon of Neptune. (f) Old and heavily cratered terrain on Vesta. (g–l) Different morphologic features on Ceres. Linear structures are denoted by arrows in (i). Small mound denoted by arrows in (k). The planetary remote sensing images (f–l) were acquired by the framing camera on the Dawn orbiter. The images (a–f) were not included in the training dataset.

Figure 10.

Qualitative comparison of 4× SR results for different geological features on various planets. (a) Central mound at the south pole on Vesta. (b) Charon’s complexity. (c) Detailed ‘Snowman’ Crater on Vesta. (d) Detailed ’Snowman’ crater on Vesta. (e) Northern hemisphere of Triton, the moon of Neptune. (f) Old and heavily cratered terrain on Vesta. (g–l) Different morphologic features on Ceres. Linear structures are denoted by arrows in (i). Small mound denoted by arrows in (k). The planetary remote sensing images (f–l) were acquired by the framing camera on the Dawn orbiter. The images (a–f) were not included in the training dataset.

Figure 11.

Qualitative comparison in 4× SR, where the image depicts the surface of the Ceres. Group (a) denotes the ground truth, input image and SR images. Group (b) denotes the image’s edge feature map extracted by the Canny edge detector. Group (c) denotes the selected area of the image’s edge feature map are detected by the Canny edge detector. Group (d) denotes the select area of the ground truth, input image and SR images. Those images were not included in the training dataset. This edge preservation is essential for crater counting and unit boundary delineation on Ceres. These images were not included in the training dataset. The planetary remote sensing image is acquired by the framing camera on the Dawn orbiter.

Figure 11.

Qualitative comparison in 4× SR, where the image depicts the surface of the Ceres. Group (a) denotes the ground truth, input image and SR images. Group (b) denotes the image’s edge feature map extracted by the Canny edge detector. Group (c) denotes the selected area of the image’s edge feature map are detected by the Canny edge detector. Group (d) denotes the select area of the ground truth, input image and SR images. Those images were not included in the training dataset. This edge preservation is essential for crater counting and unit boundary delineation on Ceres. These images were not included in the training dataset. The planetary remote sensing image is acquired by the framing camera on the Dawn orbiter.

Figure 12.

Visual comparisons of 4× SR in both spatial and frequency domains are presented, where the image depicts the surface of the Ceres. (a) denotes the planetary remote sensing images, (b) shows the frequency domain generated by DCT, and (c) presents the selected areas of the images’s frequency domain. The results demonstrate that AFSNO reduces spectral bias relative to baselines while improving spatial coherence, consistent with its frequency–spatial fusion design. The planetary remote sensing image is acquired by the framing camera on the Dawn orbiter.

Figure 12.

Visual comparisons of 4× SR in both spatial and frequency domains are presented, where the image depicts the surface of the Ceres. (a) denotes the planetary remote sensing images, (b) shows the frequency domain generated by DCT, and (c) presents the selected areas of the images’s frequency domain. The results demonstrate that AFSNO reduces spectral bias relative to baselines while improving spatial coherence, consistent with its frequency–spatial fusion design. The planetary remote sensing image is acquired by the framing camera on the Dawn orbiter.

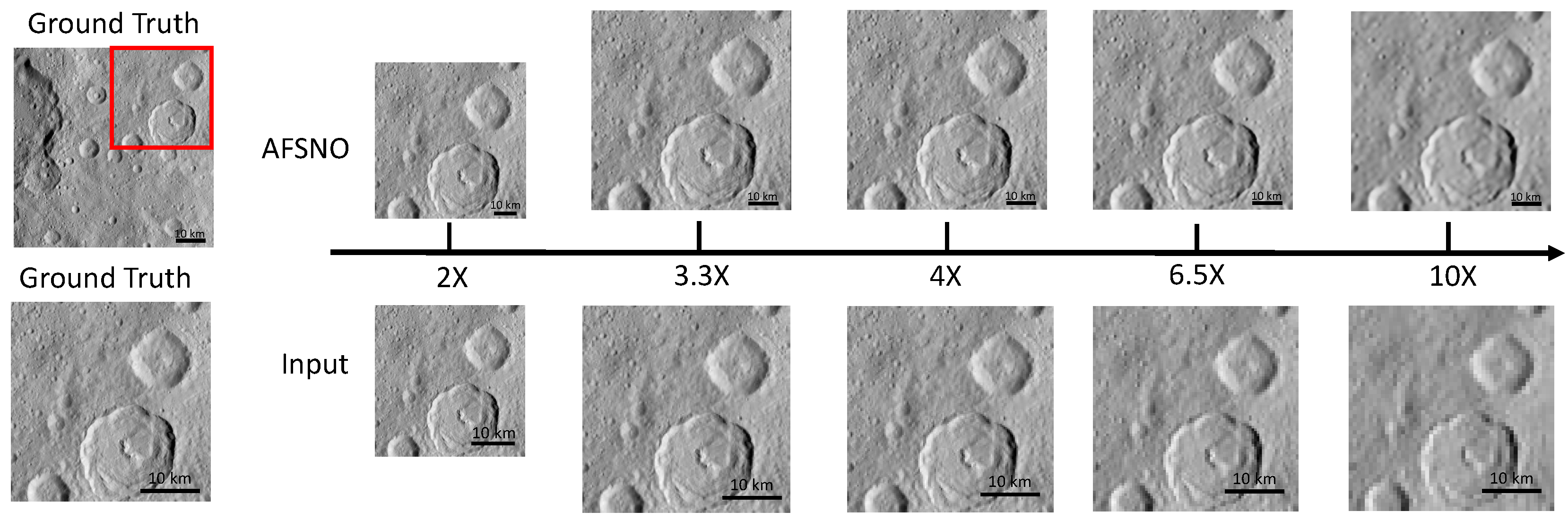

Figure 13.

Visual comparisons of crater images from the southern hemisphere of dwarf planet Ceres from an altitude of 1470 km with different scale factors ranging from 2× to 10×. AFSNO maintains rim integrity and intra-crater texture as magnification increases, indicating robust reconstruction of high-frequency content needed for crater size-frequency distribution (CSFD) analyses. The planetary remote sensing image is acquired by the framing camera on the Dawn orbiter.

Figure 13.

Visual comparisons of crater images from the southern hemisphere of dwarf planet Ceres from an altitude of 1470 km with different scale factors ranging from 2× to 10×. AFSNO maintains rim integrity and intra-crater texture as magnification increases, indicating robust reconstruction of high-frequency content needed for crater size-frequency distribution (CSFD) analyses. The planetary remote sensing image is acquired by the framing camera on the Dawn orbiter.

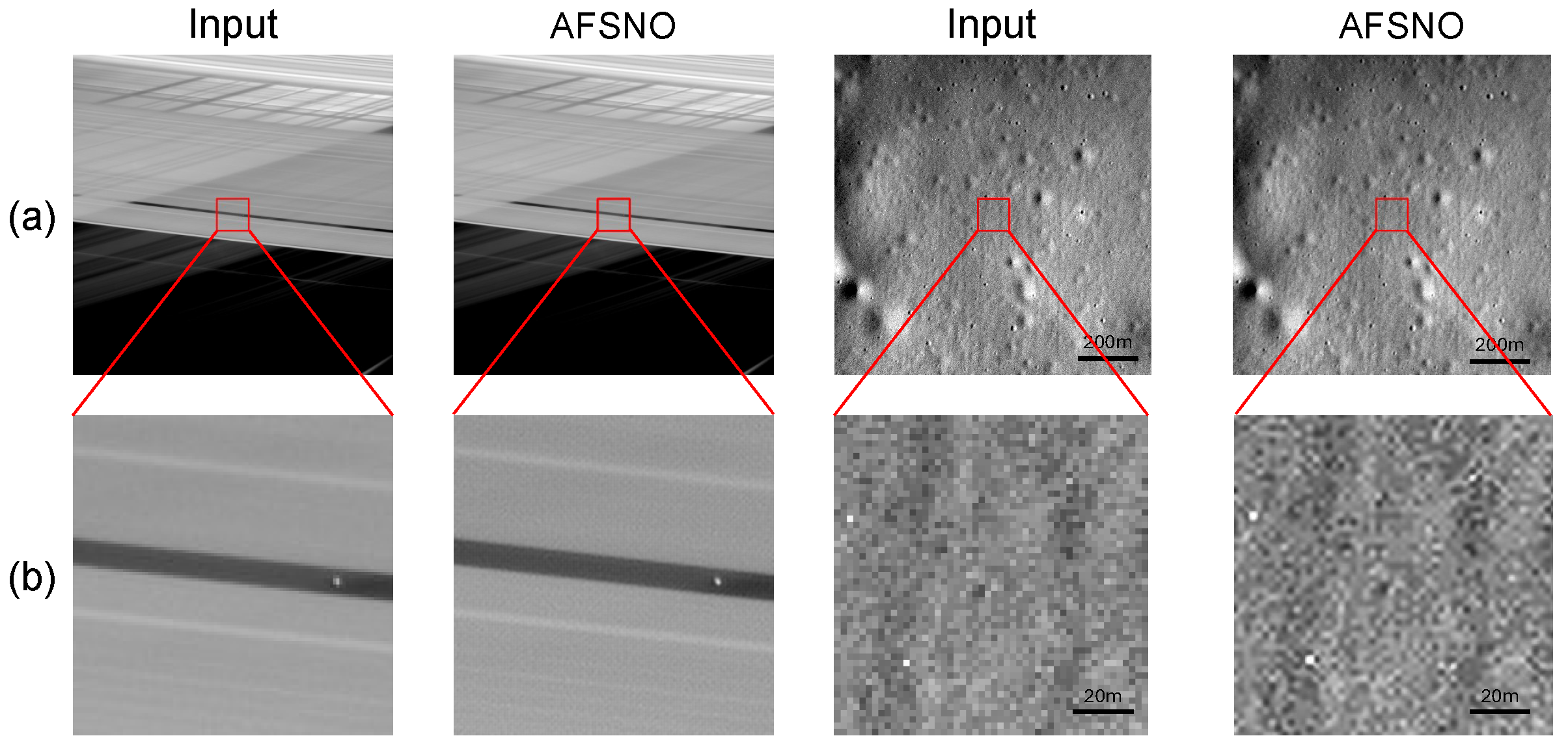

Figure 14.

Qualitative comparison of SR results for real images from various planets. The (a) denotes planetary remote sensing images. The (b) denotes selected regions from the planetary remote sensing images.The image on the left depicts Saturn’s criss-crossed rings, and the one on the right shows the surface of Mercury. Those images were not included in the training dataset and for which no ground truth images are available.

Figure 14.

Qualitative comparison of SR results for real images from various planets. The (a) denotes planetary remote sensing images. The (b) denotes selected regions from the planetary remote sensing images.The image on the left depicts Saturn’s criss-crossed rings, and the one on the right shows the surface of Mercury. Those images were not included in the training dataset and for which no ground truth images are available.

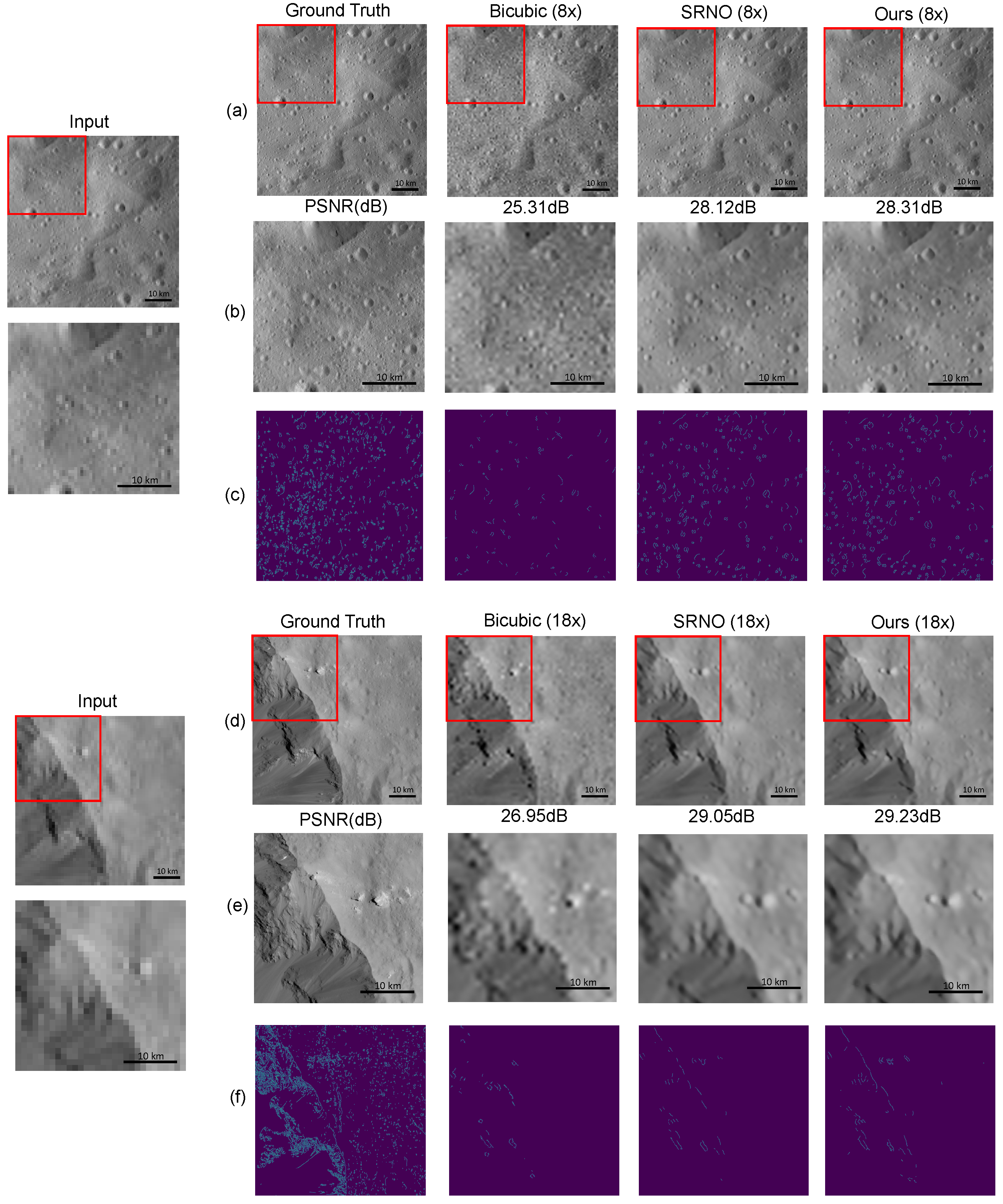

Figure 15.

Qualitative comparison of 8× and 18× SR results. Group (a) denotes the ground truth and SR images in 8× SR. Group (b) denotes the marked area of the ground truth and SR images in 8× SR. Group (c) denotes the image’s edge feature map extracted by the Canny operator in 8× SR. Group (d) denotes the ground truth and SR images in 18× SR. Group (e) denotes the selected area of the ground truth and SR images in 18× SR. Group (f) denotes the image’s edge feature map extracted by the Canny operator in 18× SR. The planetary remote sensing image is acquired by the framing camera on the Dawn orbiter.

Figure 15.

Qualitative comparison of 8× and 18× SR results. Group (a) denotes the ground truth and SR images in 8× SR. Group (b) denotes the marked area of the ground truth and SR images in 8× SR. Group (c) denotes the image’s edge feature map extracted by the Canny operator in 8× SR. Group (d) denotes the ground truth and SR images in 18× SR. Group (e) denotes the selected area of the ground truth and SR images in 18× SR. Group (f) denotes the image’s edge feature map extracted by the Canny operator in 18× SR. The planetary remote sensing image is acquired by the framing camera on the Dawn orbiter.

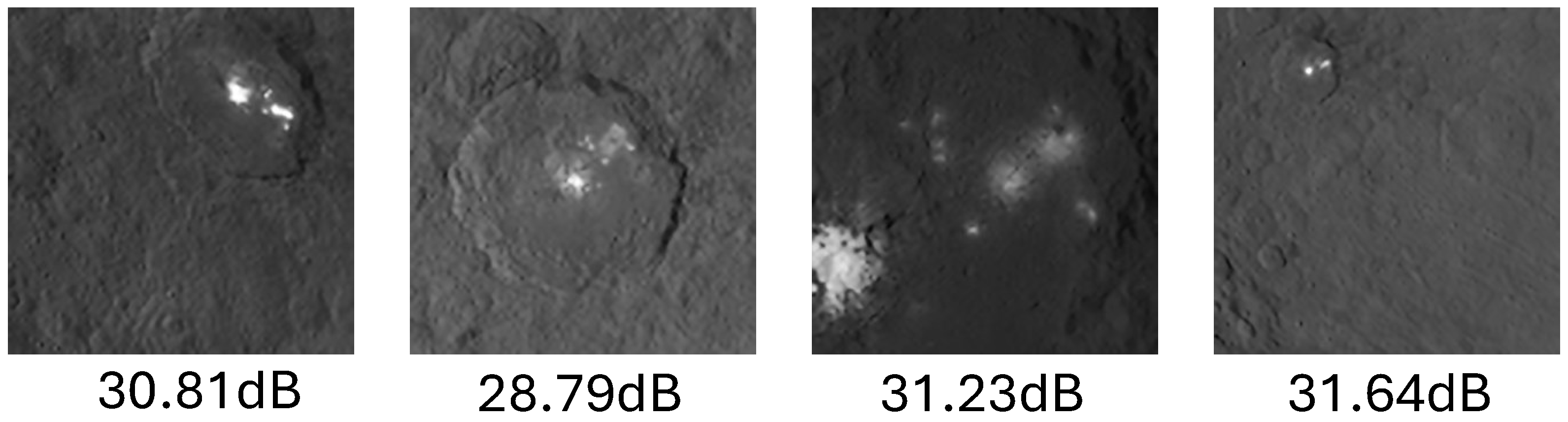

Figure 16.

Visual results for 4× SR on bright-spot images of Ceres using a model trained exclusively on Ceres-1K. These bright spots may be related to a type of salt. These images were not included in the training dataset.

Figure 16.

Visual results for 4× SR on bright-spot images of Ceres using a model trained exclusively on Ceres-1K. These bright spots may be related to a type of salt. These images were not included in the training dataset.

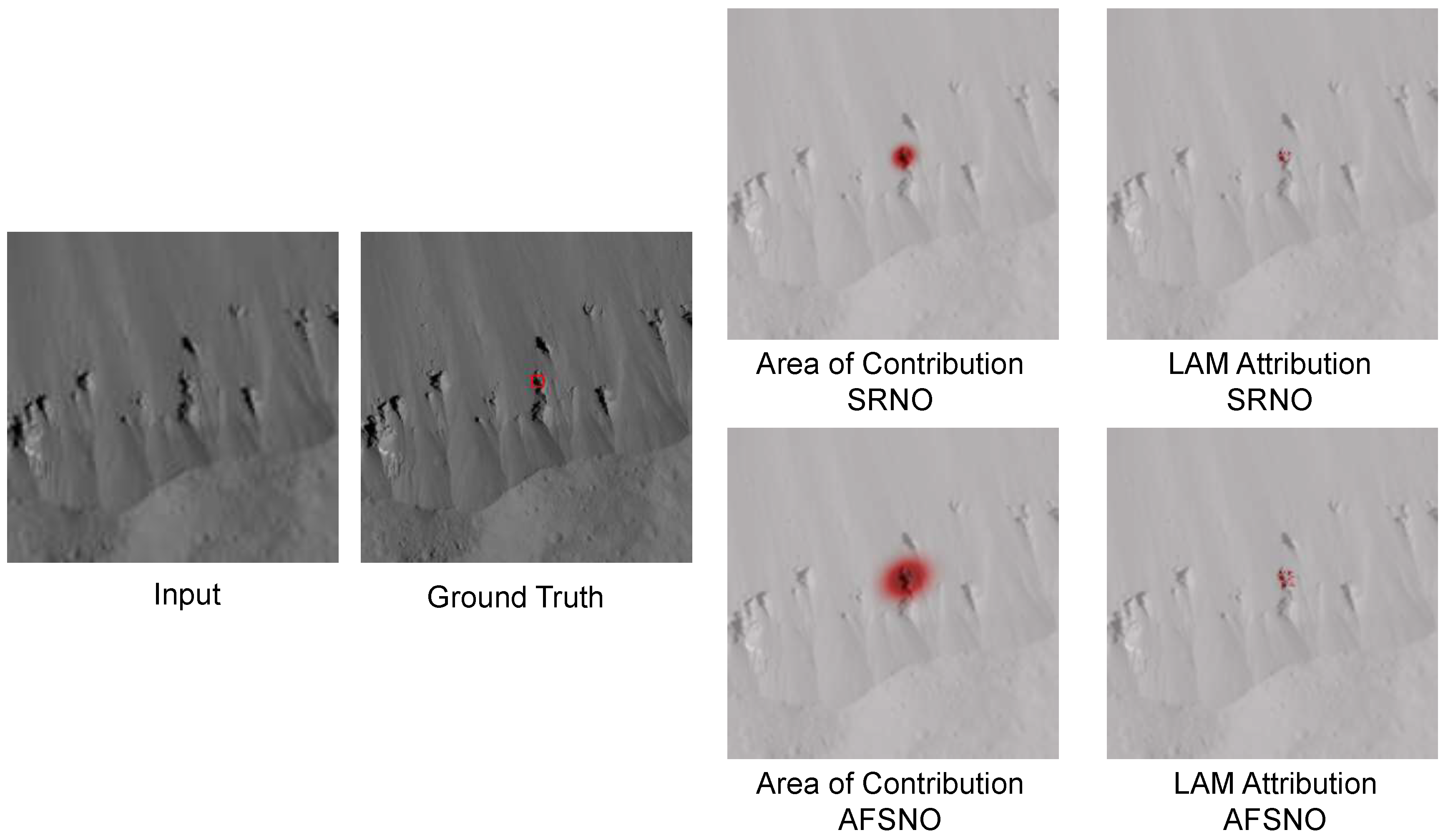

Figure 17.

Attribution results of SRNO and AFSNO in rugged area of Ceres.

Figure 17.

Attribution results of SRNO and AFSNO in rugged area of Ceres.

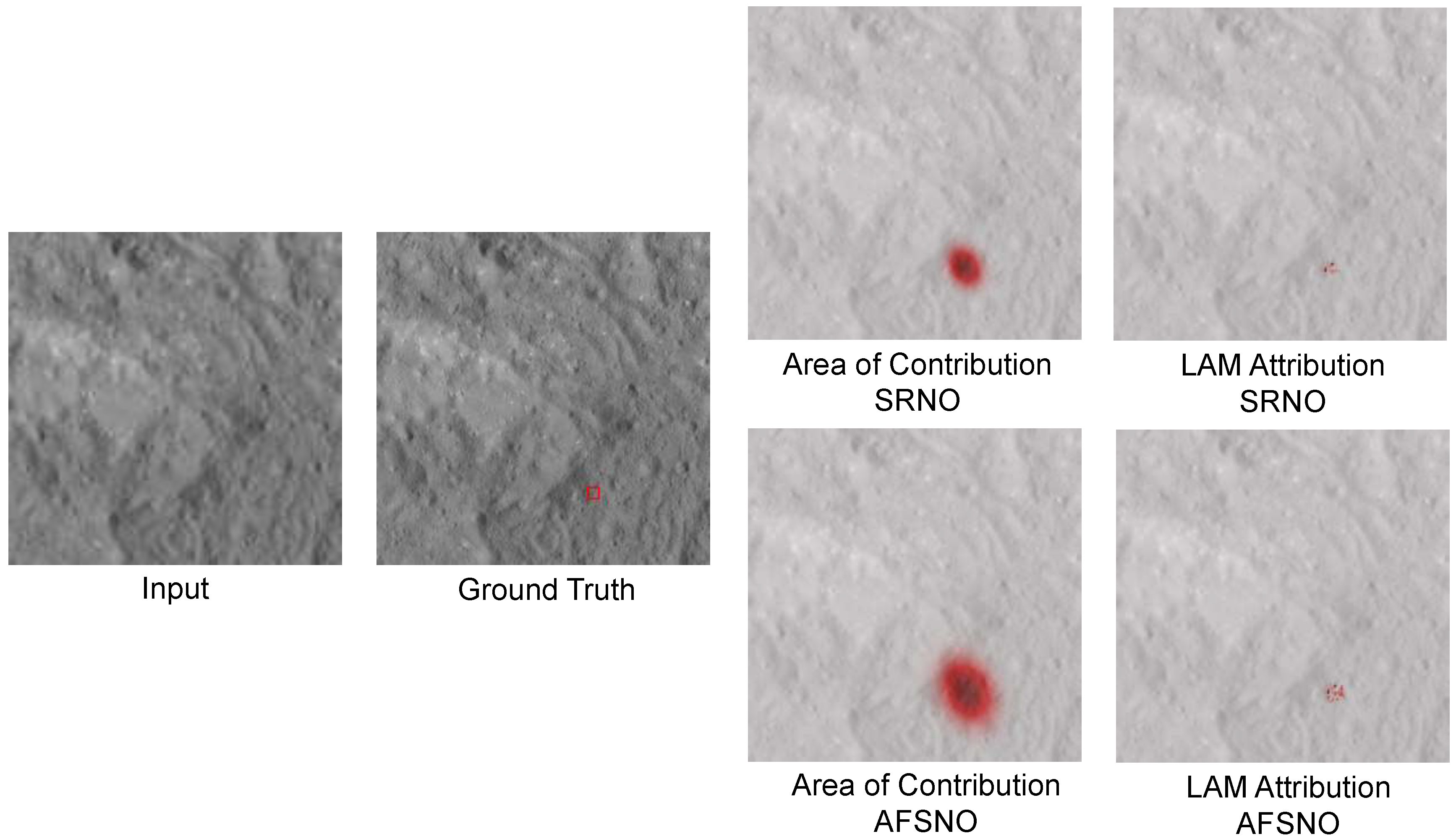

Figure 18.

Attribution results of SRNO and AFSNO in flat area of Ceres.

Figure 18.

Attribution results of SRNO and AFSNO in flat area of Ceres.

Table 1.

Average Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR) on the CERES-1K test set. The best results are emphasized with bold.

Table 1.

Average Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR) on the CERES-1K test set. The best results are emphasized with bold.

| Method | ×2 | ×3 | ×4 | ×6 | ×8 | ×10 | Params. |

|---|

| EDSR-baseline | 36.68 | 32.61 | 31.40 | – | – | – | 1.2 M |

| RDN | 36.86 | 32.73 | 31.53 | – | – | – | 2.2 M |

| HAN | 36.84 | 32.66 | 31.47 | – | – | – | 15.9 M |

| SwinIR | 36.94 | 34.05 | 32.36 | – | – | – | 11.8 M |

| Meta-SR | 36.79 | 34.07 | 32.43 | 30.47 | 29.30 | 28.49 | 1.7 M |

| LIIF | 37.15 | 34.21 | 32.49 | 30.49 | 29.31 | 28.51 | 1.6 M |

| ALIIF | 37.18 | 34.22 | 32.49 | 30.49 | 29.31 | 28.50 | 2.1 M |

| LTE | 37.23 | 34.26 | 32.52 | 30.51 | 29.33 | 28.51 | 1.7 M |

| SRNO | 37.31 | 34.33 | 32.61 | 30.58 | 29.38 | 28.57 | 2.0 M |

| AFSNO | 37.45 | 34.49 | 32.73 | 30.69 | 29.48 | 28.65 | 0.8 M |

Table 2.

Average Structural Similarity Index (SSIM) on the CERES-1K test set. The best results are emphasized with bold.

Table 2.

Average Structural Similarity Index (SSIM) on the CERES-1K test set. The best results are emphasized with bold.

| Method | ×2 | ×3 | ×4 | ×6 | ×8 | ×10 | Params. |

|---|

| EDSR-baseline | 0.911 | 0.793 | 0.731 | – | – | – | 1.2 M |

| RDN | 0.915 | 0.796 | 0.736 | – | – | – | 2.2 M |

| HAN | 0.914 | 0.812 | 0.771 | – | – | – | 15.9 M |

| SwinIR | 0.924 | 0.857 | 0.789 | – | – | – | 11.8 M |

| Meta-SR | 0.931 | 0.868 | 0.804 | 0.702 | 0.637 | 0.596 | 1.7 M |

| LIIF | 0.928 | 0.861 | 0.796 | 0.695 | 0.631 | 0.591 | 1.6 M |

| ALIIF | 0.928 | 0.861 | 0.796 | 0.694 | 0.631 | 0.592 | 2.1 M |

| LTE | 0.929 | 0.862 | 0.796 | 0.694 | 0.631 | 0.591 | 1.7 M |

| SRNO | 0.930 | 0.863 | 0.799 | 0.697 | 0.633 | 0.593 | 2.0 M |

| AFSNO | 0.932 | 0.867 | 0.804 | 0.703 | 0.639 | 0.599 | 0.8 M |

Table 3.

Comparison of model efficiency in FLOPs. The best results are emphasized with bold.

Table 3.

Comparison of model efficiency in FLOPs. The best results are emphasized with bold.

| Method | FLOPs (G) |

|---|

| LIIF | 12.24 |

| ALIIF | 12.02 |

| LTE | 16.98 |

| SRNO | 9.25 |

| AFSNO (ours) | 3.70 |

Table 4.

Ablation study of AFSNO on PSNR (dB). FNO denotes the Fusion Neural Operator component, and Edge denotes the Frequency Fusion Edge Loss. The best results are emphasized with bold.

Table 4.

Ablation study of AFSNO on PSNR (dB). FNO denotes the Fusion Neural Operator component, and Edge denotes the Frequency Fusion Edge Loss. The best results are emphasized with bold.

| Method | ×2 | ×3 | ×4 | ×6 | ×8 | ×10 | Params. |

|---|

| AFSNO(-FNO)(-EDGE) | 37.37 | 34.32 | 32.62 | 30.59 | 29.40 | 28.59 | 0.2 M |

| AFSNO(-FNO) | 37.38 | 34.33 | 32.65 | 30.61 | 29.41 | 28.59 | 0.2 M |

| AFSNO(-EDGE) | 37.42 | 34.47 | 32.72 | 30.68 | 29.47 | 28.64 | 0.8 M |

| AFSNO | 37.45 | 34.49 | 32.73 | 30.69 | 29.48 | 28.65 | 0.8 M |

Table 5.

Comparison of the PSNR and the model parameters of the EDSR-baseline and FSHE in nearest downsample. The best results are emphasized with bold.

Table 5.

Comparison of the PSNR and the model parameters of the EDSR-baseline and FSHE in nearest downsample. The best results are emphasized with bold.

| Method | ×2 | ×3 | ×4 | Params. |

|---|

| EDSR-baseline | 35.28 | 29.86 | 29.37 | 1.2 M |

| FSHE | 35.44 | 30.45 | 29.86 | 0.3 M |

Table 6.

Comparison of the PSNR and the Model Parameters of the EDSR-Baseline and FSHE in Bicubic downsample. The best results are emphasized with bold.

Table 6.

Comparison of the PSNR and the Model Parameters of the EDSR-Baseline and FSHE in Bicubic downsample. The best results are emphasized with bold.

| Method | ×2 | ×3 | ×4 | Params. |

|---|

| EDSR-baseline | 36.68 | 32.61 | 31.40 | 1.2 M |

| FSHE | 36.75 | 32.62 | 31.42 | 0.3 M |

Table 7.

Average PSNR on the Ceres-1K test set using the Anisotropic Gaussian Kernel for degradation. The best results are emphasized with bold.

Table 7.

Average PSNR on the Ceres-1K test set using the Anisotropic Gaussian Kernel for degradation. The best results are emphasized with bold.

| Method | ×2 | ×3 | ×4 | ×6 | ×8 | ×10 | Params. |

|---|

| SRNO | 34.79 | 31.92 | 29.47 | 27.28 | 25.93 | 24.86 | 2.0 M |

| AFSNO | 34.97 | 31.97 | 29.53 | 27.41 | 26.14 | 25.16 | 0.8 M |

Table 8.

Average SSIM on the Ceres-1K test set using the Anisotropic Gaussian Kernel for degradation. The best results are emphasized with bold.

Table 8.

Average SSIM on the Ceres-1K test set using the Anisotropic Gaussian Kernel for degradation. The best results are emphasized with bold.

| Method | ×2 | ×3 | ×4 | ×6 | ×8 | ×10 | Params. |

|---|

| SRNO | 0.890 | 0.803 | 0.690 | 0.579 | 0.524 | 0.493 | 2.0 M |

| AFSNO | 0.891 | 0.806 | 0.691 | 0.582 | 0.529 | 0.498 | 0.8 M |