Monthly Convective Boundary Layer Height Study over Brazil Using Radiosonde, ERA5, and COSMIC-2 Data

Highlights

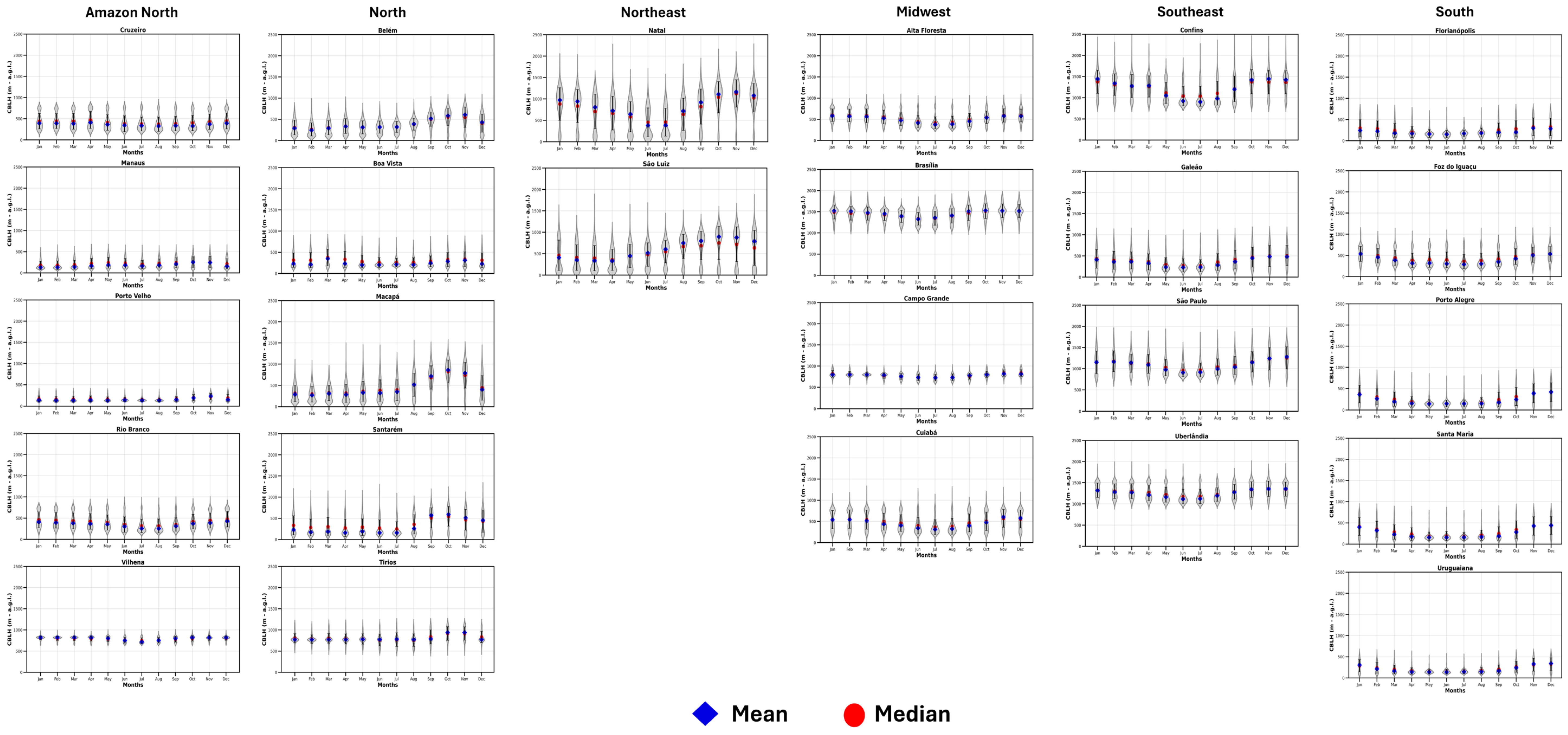

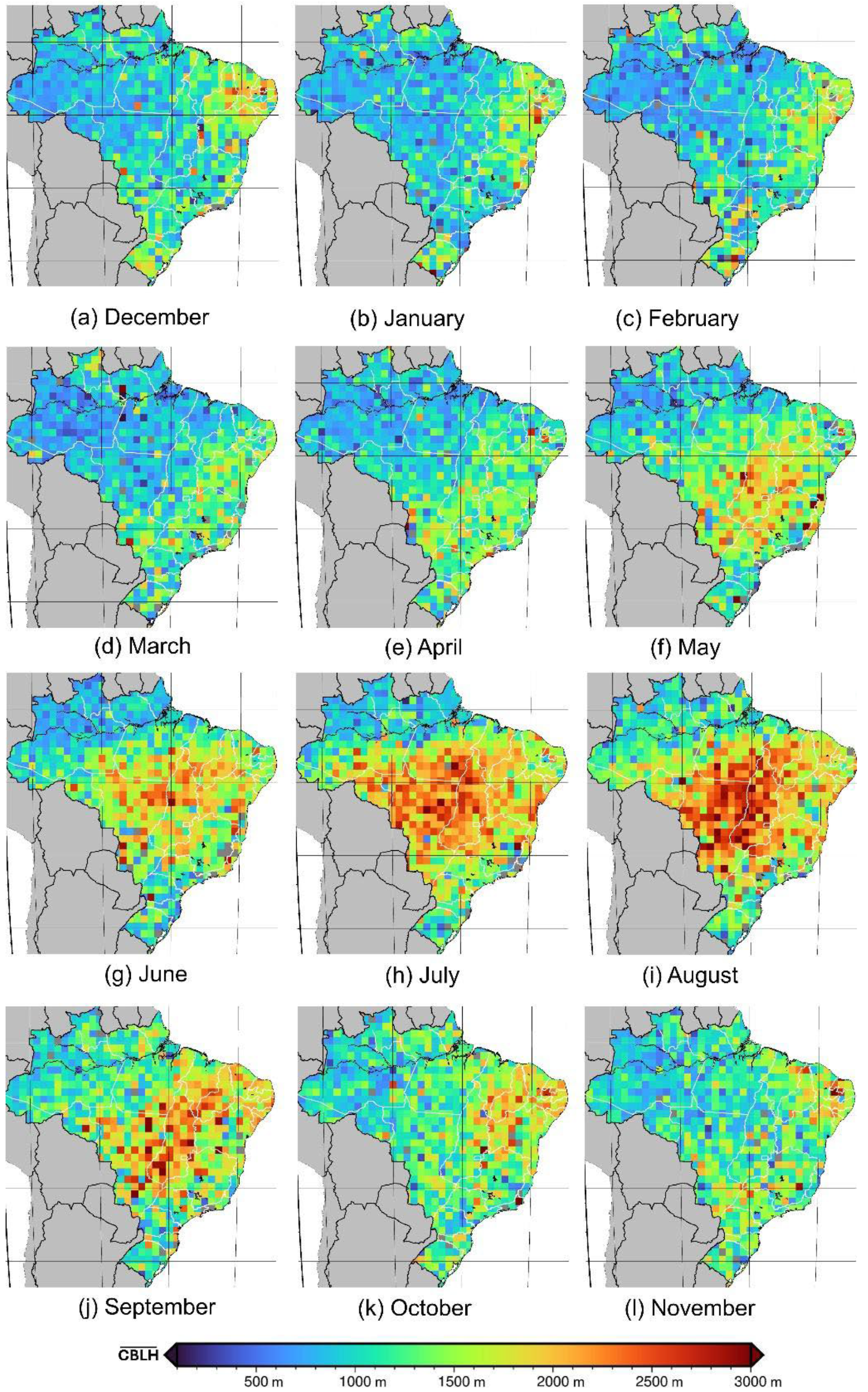

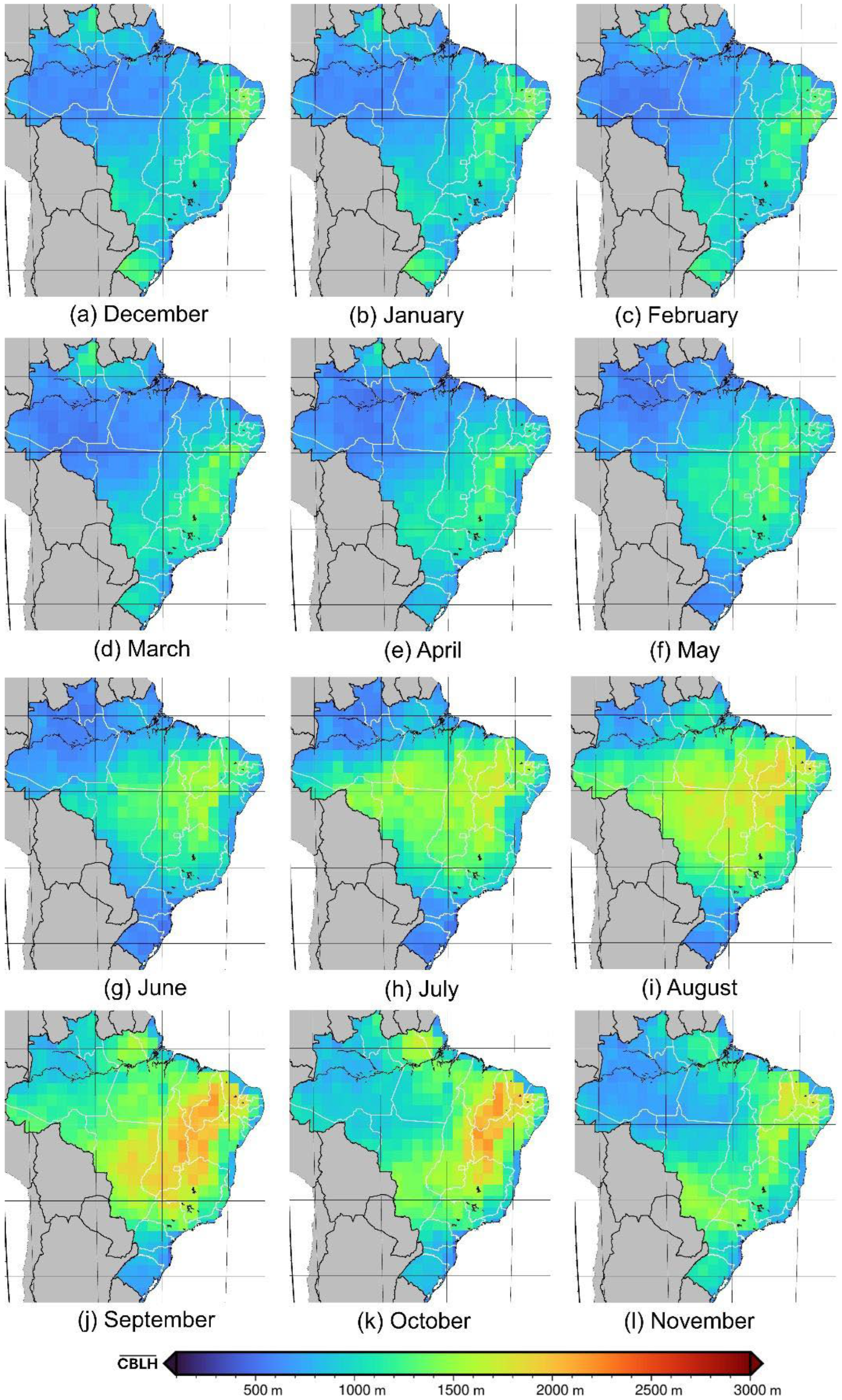

- The Convective Boundary Layer Height (CBLH) exhibits seasonal behavior that varies with the continentality and climate to which it is exposed.

- The CBLHs can be grouped into six regions (Northern Amazon, North, Northeast, Midwest, Southeast, and South);

- The CBLHs estimated from ERA5 and COSMIC-2 data show considerable agreement for most of the year;

- The large number of forest fires in the Midwest region of Brazil causes an overestimation of the CBLH estimated from COSMIC-2 data.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

Brazilian Topography and Climate

2.2. Instruments and Datasets

2.2.1. Radiosonde

2.2.2. Constellation Observing System for Meteorology Ionosphere and Climate 2 (COSMIC-2)

2.2.3. European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts Reanalysis v5 (ERA-5)

3. Methods

3.1. CBLH Estimated from Radiosonde Data

3.2. ABLH Estimated from COSMIC-2 Data

3.3. ABLH Estimated from ERA5 Data

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Characterization of CBLH from Radiosonde Data

4.2. Comparison Between the CBLH Estimated from COSMIC-2 and ERA5

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ABL | Atmospheric Boundary Layer |

| ABLH | Atmospheric Boundary Layer Height |

| FT | Free Troposphere |

| CBLH | Convective Boundary Layer Height |

| SBLH | Stable Boundary Layer Height |

| RL | Residual Layer |

| GNSS-RO | Global Navigation Satellite System Radio Occultation |

| NOAA | National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration |

| COSMIC-2 | Constellation Observing System for Meteorology, Ionosphere and Climate |

| ERA5 | ECMWF Reanalysis v5 |

| IGRA | Integrated Global Radiosonde Archive |

| IFS | Integrated Forecasting System |

| RGM | Refractivity Gradient Method |

| LSGM | Lowest Significant Gradient Method |

References

- Kotthaus, S.; Bravo-Aranda, J.A.; Collaud Coen, M.; Guerrero-Rascado, J.L.; Costa, M.J.; Cimini, D.; O’Connor, E.J.; Hervo, M.; Alados-Arboledas, L.; Jiménez-Portaz, M.; et al. Atmospheric boundary layer height from ground-based remote sensing: A review of capabilities and limitations. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2023, 16, 433–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garratt, J.R. Review: The atmospheric boundary layer. Earth-Sci. Rev. 1994, 37, 89–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stull, R.B. An Introduction to Boundary Layer Meteorology; Atmospheric and Oceanographic Sciences Library; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Guo, J.; Miao, Y.; Liu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhai, P. Planetary boundary layer height from CALIOP compared to radiosonde over China. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2016, 16, 9951–9963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalmus, P.; Ao, C.O.; Wang, K.N.; Manzi, M.P.; Teixeira, J. A high-resolution planetary boundary layer height seasonal climatology from GNSS radio occultations. Remote Sens. Environ. 2022, 276, 113037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garnés-Morales, G.; Costa, M.J.; Bravo-Aranda, J.A.; Granados Muñoz, M.J.; Salgueiro, V.; Abril Gago, J.; Fernández Carvelo, S.; Andújar Maqueda, J.; Valenzuela, A.; Foyo Moreno, I.; et al. Four Years of Atmospheric Boundary Layer Height Retrievals Using COSMIC-2 Satellite Data. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Engeln, A.; Teixeira, J. A Planetary Boundary Layer Height Climatology Derived from ECMWF Reanalysis Data. J. Climate 2015, 26, 6575–6590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.S.; Pan, C.J. Climatology of the Atmospheric Boundary Layer Height Using ERA5: Spatio-Temporal Variations and Controlling Factors. Atmosphere 2025, 16, 573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidel, D.J.; Ao, C.O.; Li, K. Estimating climatological planetary boundary layer heights from radiosonde observations: Comparison of methods and uncertainty analysis. J. Geophys. Res. 2010, 115, D16113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, N.; Wang, R. Diurnal variability of the planetary boundary layer height estimated from radiosonde data. Earth Planet. Phys. 2020, 4, 479–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero-Rascado, J.L.; Landulfo, E.; Antuña, J.C.; Barbosa, H.M.J.; Barja, B.; Bastidas, A.E.; Bedoya, A.E.; da Costa, R.F.; Estevan, R.; Forno, R.; et al. Latin American Lidar Network (LALINET) for aerosol research: Diagnosis on network instrumentation. J. Atm. Solar-Terr. Phys. 2016, 138–139, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antuña-Marrero, J.C.; Landulfo, E.; Estevan, R.; Barja, B.; Robock, B.A.; Wolfram, E.; Ristori, P.; Clemesha, B.; Simonich, D.; Zaratti, F.; et al. LALINET: The first Latin American-born regional atmospheric observational network. Bull. Amer. Meteorol. Soc. 2017, 98, 1255–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, K.J.; Arblaster, J.M.; Alexander, L.V.; Siems, S.T. Spurious trends in high latitude Southern Hemisphere precipitation observations. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2024, 51, e2023GL106994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnamurti, T.N.; Stefanova, L.; Misra, V. Tropical Meteorology: An Introduction. Springer Atmospheric Sciences, 1st ed.; Springer New York: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Carneiro, R.G.; Fisch, G. Observational analysis of the daily cycle of the planetary boundary layer in the central Amazon during a non-El Niño year and El Niño year (GoAmazon project 2014/5). Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2020, 20, 5547–5558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraiva, L.; Krusche, N. Estimation of the Boundary Layer Height in the Southern Region of Brazil. Am. J. Environ. Eng. 2013, 3, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piñero Sánchez, M.; de Oliveira, A.P.; Varona, R.P.; Tito, J.V.; Codato, G.; Ribeiro, F.N.D.; Marques Filho, E.P.; Silveira, L.C.d. Rawinsonde-based analysis of the urban boundary layer in the metropolitan region of São Paulo, Brazil. Earth Space Sci. 2019, 7, e2019EA000781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, G.A.; da Silva Andrade, I.; Cacheffo, A.; da Silva Lopes, F.J.; Calzavara Yoshida, A.; Gomes, A.A.; da Silva, J.J.; Landulfo, E. Influence of a Biomass-Burning Event in PM2.5 Concentration and Air Quality: A Case Study in the Metropolitan Area of São Paulo. Sensors 2021, 21, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreira, G.A.; Oliveira, A.P.D.; Codato, G.; Sánchez, M.P.; Tito, J.V.; Silva, L.A.H.E.; Silveira, L.C.D.; Silva, J.J.D.; Lopes, F.J.D.S.; Landulfo, E. Assessing Spatial Variation of PBL Height and Aerosol Layer Aloft in São Paulo Megacity Using Simultaneously Two Lidars during Winter 2019. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, G.A.; Pereira Oliveira, A.; Piñero-Sánchez, M.; Codato, G.; da Silva Lopes, F.J.; Landulfo, E.; Pereira Marques Filho, E. Performance assessment of aerosol-lidar remote sensing skills to retrieve the time evolution of the urban boundary layer height in the Metropolitan Region of São Paulo City, Brazil. Atmos. Res. 2022, 277, 106290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, G.A.; Amorim Marques, M.T.; da Silva Lopes, F.J.; Andrade, M.F.; Landulfo, E. Analyzing the influence of the planetary boundary layer height, ventilation coefficient, thermal inversions, and aerosol optical Depth on the concentration of PM2.5 in the city of São Paulo: A long-term study. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 2024, 15, 102179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, M.T.A.; Moreira, G.A.; Pinero, M.; Oliveira, A.P.; Landulfo, E. Estimating the planetary boundary layer height from radiosonde and Doppler Lidar measurements in the city of São Paulo—Brazil. EPJ Web Conf. 2018, 176, 06015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Zhang, J.; Yang, K.; Liao, H.; Zhang, S.; Huang, K.; Lv, Y.; Shao, J.; Yu, T.; Tong, B.; et al. Investigation of near-global daytime boundary layer height using high-resolution radiosondes: First results and comparison with ERA5, MERRA-2, JRA-55, and NCEP-2 reanalyses. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2021, 21, 17079–17097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministério de Assuntos Exteriores (Governo do Brasil): Dados Sobre Geografia do Brasil. Available online: https://www.gov.br/mre/pt-br/embaixada-bogota/datos-sobre-brasil/geografia (accessed on 19 August 2024).

- Ministério de Assuntos Exteriores, União Européia e Cooperação (Gobierno de España): Ficha País Brasil. Available online: https://www.exteriores.gob.es/Documents/FichasPais/BRASIL_FICHA%20PAIS.pdf (accessed on 19 August 2024).

- Alvares, C.A.; Stape, J.L.; Sentelhas, P.C.; Gonçalves, J.L.d.M. Modeling monthly mean air temperature for Brazil. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2013, 113, 407–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvares, C.A.; Stape, J.L.; Sentelhas, P.C.; de Moraes Gonçalves, J.L.; Sparovek, G. Köppen’s climate classification map for Brazil. Meteorol. Z. 2013, 22, 711–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IGRA Sounding Data for the Full Period of Record. Available online: https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/data/integrated-global-radiosonde-archive/access/data-por/ (accessed on 17 July 2024).

- COSMIC-2 Data. Available online: https://data.cosmic.ucar.edu/gnss-ro/cosmic2/nrt/ (accessed on 17 July 2024).

- ERA5: Download Data. Available online: https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/datasets/reanalysis-era5-single-levels?tab=download (accessed on 17 July 2024).

- Durre, I.; Yin, X.; Vose, R.S.; Applequist, S.; Arnfield, J. Enhancing the Data Coverage in the Integrated Global Radiosonde Archive. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 2018, 35, 1753–1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiner, W.S.; Weiss, J.P.; Anthes, R.A.; Braun, J.; Chu, V.; Fong, J.; Hunt, D.; Kuo, Y.-H.; Meehan, T.; Serafino, W.; et al. COSMIC-2 Radio Occultation Constellation: First Results. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2020, 47, e2019GL086841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Xu, T.; Gao, F.; Wang, S.; Li, S. Analysis of cosmic-2 atmospheric boundary layer detection ability. In China Satellite Navigation Conference (CSNC 2021) Proceedings, Lecture Notes in Electrical Engineering; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 43–53. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, S.; Anthes, R.A.; Ao, C.O.; Healy, S.; Horanyi, A.; Hunt, D.; Mannucci, A.J.; Pedatella, N.; Randel, W.J.; Simmons, A.; et al. The COSMIC/FORMOSAT-3 Radio Occultation Mission after 12 Years: Accomplishments, Remaining Challenges, and Potential Impacts of COSMIC-2. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2020, 101, E1107–E1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, G.A.; Guerrero-Rascado, J.L.; Bravo-Aranda, J.A.; Benavent-Oltra, J.A.; Ortiz-Amezcua, P.; Román, R.; Bedoya-Velásquez, A.; Landulfo, E.; AladosArboledas, L. Study of the planetary boundary layer by microwave radiometer, elastic lidar and Doppler lidar estimations in Southern Iberian Peninsula. Atmos. Res. 2018, 213, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, G.A.; Guerrero-Rascado, J.L.; Bravo-Aranda, J.A.; Foyo-Moreno, I.; Cazorla, A.; Alados, I.; Lyamani, H.; Landulfo, E.; Alados Arboledas, L. Study of the planetary boundary layer height in an urban environment using a combination of microwave radiometer and ceilometer. Atmos. Res. 2020, 240, 104932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santosh, M. Estimation of daytime planetary boundary layer height (PBLH) over the tropics and subtropics using COSMIC-2/FORMOSAT-7 GNSS–RO measurements. Atmos. Res. 2022, 279, 106361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, D.; Leong, W.J.; Fröhlich, Y.; Grund, M.; Schlitzer, W.; Jones, M.; Toney, L.; Yao, J.; Tong, J.-H.; Magen, Y.; et al. PyGMT: A Python Interface for the Generic Mapping Tools, v0.17.0; Zenodo: Genève, Switzerland, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hersbach, H.; Bell, B.; Berrisford, P.; Hirahara, S.; Horányi, A.; Muñoz-Sabater, J.; Nicolas, J.; Peubey, C.; Radu, R.; Schepers, D.; et al. The ERA5 global reanalysis. Q. J. R. Meteorol Soc. 2020, 146, 1999–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Gao, Z.; Li, D.; Li, Y.; Zhang, N.; Zhao, X.; Chen, J. On the computation of planetary boundary-layer height using the bulk Richardson number method. Geosci. Model Dev. 2014, 7, 2599–2611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, S.R. The thickness of the planetary boundary layer. Atmos. Environ. 1969, 3, 519–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.ecmwf.int/sites/default/files/elibrary/2017/17736-part-iv-physical-processes.pdf#section.3.10 (accessed on 17 July 2024).

- Abram, N.J.; Henley, B.J.; Sen Gupta, A.; Lippmann, T.J.R.; Clarke, H.; Dowdy, A.J.; Sharples, J.J.; Nolan, R.H.; Zhang, T.; Wooster, M.J.; et al. Connections of climate change and variability to large and extreme forest fires in southeast Australia. Commun. Earth Environ. 2021, 2, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, G.A.; Carbone, S.; Guerrero-Rascado, J.L.; Andrade, I.D.S.; Cacheffo, A.; Vélez-Pereira, A.M.; Zamora-Ledezma, E.; Thielen, D.; Gomes, A.A.; Duarte, E.D.S.F.; et al. Evidence of the consequences of the prolonged fire season on air quality and public health from 2024 São Paulo (Brazil) data. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 28337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basha, G.; Ratnam, M.V. Identification of atmospheric boundary layer height over a tropical station using high-resolution radiosonde refractivity profiles: Comparison with GPS radio occultation measurements. J. Geophys. Res. 2009, 114, D16101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Engeln, A.; Teixeira, J.; Wickert, J.; Buehler, S.A. Using CHAMP radio occultation data to determine the top altitude of the Planetary Boundary Layer. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2005, 32, L06815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Surface | Period | Threshold |

|---|---|---|

| Land | Day | 82% |

| Night | 68% | |

| Transition | 98% | |

| Ocean | All | 99% |

| Brazilian Regions | -) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| JAN | FEB | MAR | APR | MAY | JUN | JUL | AUG | SEP | OCT | NOV | DEC | |

| North | 179 | 171 | 169 | 200 | 290 | 311 | 355 | 285 | 143 | 130 | 178 | 183 |

| Northeast | 416 | 423 | 367 | 328 | 442 | 530 | 533 | 525 | 418 | 382 | 320 | 376 |

| Midwest | 60 | 149 | 111 | 271 | 561 | 634 | 802 | 727 | 230 | 50 | 128 | 63 |

| Southeast | 241 | 270 | 306 | 480 | 646 | 606 | 661 | 537 | 256 | 213 | 274 | 294 |

| South | 288 | 407 | 430 | 516 | 565 | 508 | 757 | 517 | 426 | 420 | 354 | 320 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

de Arruda Moreira, G.; Pérez Herrera, M.J.; Garnés Morales, G.; Costa, M.J.; Cacheffo, A.; Carbone, S.; Lopes, F.J.d.S.; Abril-Gago, J.; Andújar-Maqueda, J.; de Souza Fernandes Duarte, E.; et al. Monthly Convective Boundary Layer Height Study over Brazil Using Radiosonde, ERA5, and COSMIC-2 Data. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3672. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17223672

de Arruda Moreira G, Pérez Herrera MJ, Garnés Morales G, Costa MJ, Cacheffo A, Carbone S, Lopes FJdS, Abril-Gago J, Andújar-Maqueda J, de Souza Fernandes Duarte E, et al. Monthly Convective Boundary Layer Height Study over Brazil Using Radiosonde, ERA5, and COSMIC-2 Data. Remote Sensing. 2025; 17(22):3672. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17223672

Chicago/Turabian Stylede Arruda Moreira, Gregori, María Jesús Pérez Herrera, Ginés Garnés Morales, Maria João Costa, Alexandre Cacheffo, Samara Carbone, Fábio Juliano da Silva Lopes, Jesús Abril-Gago, Juana Andújar-Maqueda, Ediclê de Souza Fernandes Duarte, and et al. 2025. "Monthly Convective Boundary Layer Height Study over Brazil Using Radiosonde, ERA5, and COSMIC-2 Data" Remote Sensing 17, no. 22: 3672. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17223672

APA Stylede Arruda Moreira, G., Pérez Herrera, M. J., Garnés Morales, G., Costa, M. J., Cacheffo, A., Carbone, S., Lopes, F. J. d. S., Abril-Gago, J., Andújar-Maqueda, J., de Souza Fernandes Duarte, E., Pires Salgueiro, V. C., Bortoli, D., & Guerrero-Rascado, J. L. (2025). Monthly Convective Boundary Layer Height Study over Brazil Using Radiosonde, ERA5, and COSMIC-2 Data. Remote Sensing, 17(22), 3672. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17223672