Highlights

What are the main findings?

- The evolution of the Mars Year 35 anomalous spring dust storm was studied in four phases. The evolution characteristics of the spring dust storm are similar to those of the MY 35 C storm, suggesting that the two storms may have similar evolutionary mechanisms.

- The Mars Year 35 anomalous spring dust storm impacts the atmospheric thermal structures and global circulation. Wind speeds at the surface and at high altitudes increase significantly in specific regions during the storm.

What is the implication of the main finding?

- The study of changes in the wind field during the spring dust storm in the Chryse and Utopia plains can offer necessary environmental parameters related to spring dust storms for China’s Tianwen-3 mission.

Abstract

Dust storms have a significant impact on the Martian atmosphere and climate. Previous studies have found that regional and global dust storms mainly occur in the Mars perihelion season. However, an anomalous spring regional dust storm occurred in the aphelion season of Martian year 35 (MY 35). The occurrence and evolution of this new type of large dust storm and its impact on the Martian atmosphere are not yet fully understood. Using Mars Climate Sounder (MCS) dust observations, this study investigates the evolutionary characteristics of the MY 35 anomalous spring storm during its pre-storm, onset, expansion, and decay phases, by comparing it with other types of regional dust storms. The evolution of the MY 35 anomalous spring dust storm is more similar to that of the MY 35 C storm, showing north–south mirror symmetry relative to the equator, suggesting that the two storms may have similar evolutionary mechanisms. Additionally, we analyze the effects of the anomalous MY 35 storm on the atmospheric thermal and dynamical structures using a combination of MCS temperature observations and LMD-GCM wind simulation results. Eastward winds in the high latitudes of both hemispheres and westward winds in the low-to-mid latitudes are significantly enhanced during the storm, corresponding to the change in the atmospheric thermal structure and the global circulation. Finally, we performed a preliminary analysis of changes in the wind field during the spring dust storm in the Chryse and Utopia plains, which are two potential landing areas for China’s Tianwen-3 Mars sample-return mission. The vertical profiles of the simulated horizonal wind in the two plains show that, during the E storm peak time, the change in daily mean wind speed is significant above 20 km, but relatively small in the atmospheric boundary layer below ~5 km. Within the boundary layer, the horizontal wind speed shows remarkable diurnal variation, remaining relatively low during the midday hours (10:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m.). These results can provide necessary environmental parameters related to spring dust storms for China’s Tianwen-3 mission.

1. Introduction

The spatial and temporal variability of dust is important to Martian weather and climate because it is closely related to the thermal and dynamical structure of the Martian atmosphere [1,2,3,4]. Almost all coupled thermal and dynamical processes on Mars are directly or indirectly affected by the dust cycle [5]. Martian dust storms occur on various scales, ranging from local storms (>102 km2) to regional storms (1.6 × 106 km2) and even global storms that sweep across the planet [6]. They are one of the key processes that control climate evolution on seasonal and interannual timescales, as well as meteorological change on shorter timescales. In addition, large-scale dust storms pose a significant threat to Mars exploration missions [7,8], endangering spacecraft during entry, descent, and landing (EDL) and ground-based operations [9,10].

Dust storms on Mars exhibit clear seasonal patterns, primarily occurring during the fall and winter in the Northern Hemisphere [11,12], when Mars is near perihelion. This period is characterized by intense insolation and frequent dust storms. Previous studies have referred to this period as the ‘dusty season’ [4]. Three types of regional dust storms occur primarily during the dusty season, which are defined as A, B, and C storms in chronological order. Additionally, global dust storms sweep across the entire planet every few years [13,14]. The global storms last for months, have a significant impact, and usually begin at a time and location similar to A storms. Another type of regional dust storm, defined as Z storms [15,16], was observed in MY29 and MY36 at around Ls = 150°. In contrast to the annual recurrence of A, B, and C storms, Z storms do not occur every year. Since Z dust storms are very close to the beginning of the dusty season, their occurrence can also be regarded as an early start of the dusty season in some years [17].

Large-scale regional dust storms do not usually occur in the Northern Hemisphere of Mars during spring and summer because the planet is near aphelion, resulting in weak insolation and reduced energy input into the atmosphere. However, an anomalously large regional dust storm occurred in the spring of MY 35, which is the only regional dust storm observed in the northern spring throughout the past three decades [18]. Previous studies of Martian dust storms have mainly focused on regional and global dust storms during the perihelion season. The characteristics of the anomalous spring dust storm of MY 35, and how it compares with those of other types of regional dust storms, have not yet been systematically investigated.

Furthermore, the northern spring and summer are traditionally considered the best times of year for surface exploration missions on Mars. For instance, China has announced plans to launch a sample-return mission, Tianwen-3, around 2028, which could land on Mars and carry out its primary operations during the northern spring [19]. However, despite occurring during a period of relatively weak insolation, the scale and impact of the MY 35 spring dust storm are comparable to regional dust storms during the dusty season [20]. Should a spring dust storm occur during the Mars sample-return mission, the atmospheric dynamics process could be significantly impacted, thereby posing a threat to the mission’s safety [21,22].

Compared to forecasting dust storms on Earth, accurately predicting the occurrence of dust storms on Mars is more difficult or nearly impossible because there is very little observational data available on key atmospheric parameters of Mars, such as the wind field and dust particle characteristics that support numerical forecasting. The recent boom in machine learning offers the potential to predict Martian airborne dust trends [23]. However, its accuracy and effectiveness are limited by the capabilities of Mars’ atmospheric observations. Moreover, given the limited occurrence of spring dust storms, the availability of data for machine learning is restricted, thus hindering the effectiveness of machine learning methods in predicting this type of regional dust storm. Although spring dust storms are almost impossible to predict, we can use satellite observations in combination with numerical models to conduct preliminary research into important atmospheric parameter changes, such as wind fields, that occur during these storms. This will facilitate a more comprehensive understanding of the potential impact of spring dust storms on future Martian missions, thereby enabling the design of engineering response strategies in advance.

In light of the above considerations, we utilize the Mars Climate Sounder (MCS) observations to present the first detailed investigation of the horizontal and vertical evolution of an anomalous spring dust storm during MY 35, and compare its characteristics with those of typical types of regional dust storms on Mars. Furthermore, we combine simulation results from the Laboratoire de Météorologie Dynamique Martian Global Climate Model (LMD-GCM) to examine changes in the atmospheric wind field during the storm and its potential impact on the future Mars sample-return mission of China. The simulation analyses focus on Chryse and Utopia Plains, which are two important potential candidates for the Tianwen-3 landing site [19,22].

2. Data and Methods

2.1. The MCS Data

The MCS onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) has five mid-infrared channels, three far-infrared channels, and one broadband visible/near-infrared channel. It can provide atmospheric temperature and dust opacity observations in a sun-synchronous polar orbit at relatively constant local times of about 3:00 a.m. and 3:00 p.m. [24]. The MCS measures the Martian atmosphere between 85°N and 85°S from near the surface up to an altitude of 80 km with a vertical resolution of ~ 5 km. Since September 2006, it has been operating for over ten Mars years. Therefore, the MCS can provide observational data with a high spatio-temporal resolution on the global three-dimensional distribution of atmospheric temperature and airborne dust. Previous studies have used MCS data to systematically investigate type A, B, C, and Z dust storms on Mars, as well as global dust storms during MY 28 and MY 34, including their complete evolution cycles from the origin and propagation to the subsequent dissipation [4,12,25,26].

The temperature and dust data used in this study are obtained from the MCS-Derived Data Records Version 5, as released by the NASA Planetary Data System. The MCS data are stored on 105 regular pressure grids. On each pressure level, we bin the temperature and dust data with a latitude interval of 10°, a longitude interval of 30°, and a solar longitude (Ls) interval of 1°, for the daytime and nighttime separately. Note that the dust opacity measured by the MCS represents the extinction of solar radiation within the atmosphere, and is proportional to the volume mixing ratio of dust. However, the volume mixing ratio is not conserved by mixing processes. On the other hand, the dust mass mixing ratio (q), which is proportional to the density-scaled opacity (where is the air density), 1 is conserved and provides a more accurate representation of dust advection [12,27,28]. According to previous studies and under several assumptions, conversions between the dust mass mixing ratio and the density-scaled opacity are straightforward: q (ppm) = 1.2 × 104 [12,28]. The air density can be computed using the MCS pressure and temperature data based on the ideal gas law assumption. In this work, the dust mass mixing ratio is used in the analysis of dust storm evolutions.

2.2. The LMD-GCM

The LMD-GCM is a state-of-the-art Martian general circulation model (now also known as the Mars Planetary Climate Model) that consists of a dynamical core using the finite difference method to solve primitive equations, and a physical core incorporating a variety of comprehensive processes, such as radiative transfer, the carbon dioxide cycle, the dust cycle, and the water cycle [29]. The daily map of the column dust optical depth (CDOD) at 9.3 μm, from MY 24 to MY 36, is used as a forcing by the LMD-GCM to represent the interannual variation in the state of the Martian atmosphere [2,30]. The CDOD data are obtained from the Thermal Emission Spectrometer on the Mars Global Surveyor, the Thermal Emission Imaging System on the Mars Odyssey, and the MCS on the MRO [30]. The gridded CDOD data used in this paper are available on the website http://www-mars.lmd.jussieu.fr/ (accessed on 1 February 2025). Then, the vertical distribution and transport of dust particles in the atmosphere are modeled using a semi-interactive method [31]. The LMD-GCM has been widely used for simulating Martian dust storm dynamics and their influences on the atmosphere [20,32,33]. The results of the LMD-GCM are also used to build the Mars Climate Database (MCD) [29,31]. The simulation results from the MCD agree well with multiple observations, indicating the reliability of the LMD-GCM [34]. In this study, the LMD-GCM adopts the typical 64 × 48 grid as in previous studies [35], which provides a longitude resolution of 5.625° and a latitude resolution of 3.75°. In the vertical direction, we use 54 sigma-pressure levels for the simulation covering the altitude range from near surface to 115 km. The model output is generated at a frequency of every two hours. To investigate the atmospheric response to the MY 35 spring dust storm, we primarily use the CDOD of MY 35 and the multi-year averaged CDOD excluding years with global dust storms, to simulate atmospheric conditions during the MY 35 anomalous spring dust storm and the same period in the climatological year, respectively.

In addition, some distinctions exist in the representation of the atmospheric vertical structure between the MCS and LMD-GCM datasets used in this work. Specifically, the MCS dataset employs pressure as the vertical coordinate, whereas the LMD-GCM dataset utilizes geometric altitude. An approximate correspondence can be established between these two coordinate systems. For instance, near the Martian surface, the atmospheric pressure is approximately 610 Pa; at an altitude of 15 km, it declines to roughly 200 Pa; and at 25 km, it further decreases to around 50 Pa. In contrast to the relatively stable atmospheric pressure observed on Earth, the Martian atmosphere—composed predominantly of condensable carbon dioxide—exhibits pronounced seasonal variability due to the sublimation and condensation of polar ice caps. The diurnal, seasonal, and interannual variations in atmospheric pressure are mainly influenced by solar insolation, atmospheric tides, and dust activity [36].

3. Results

3.1. The Evolution of the MY 35 Spring Dust Storm

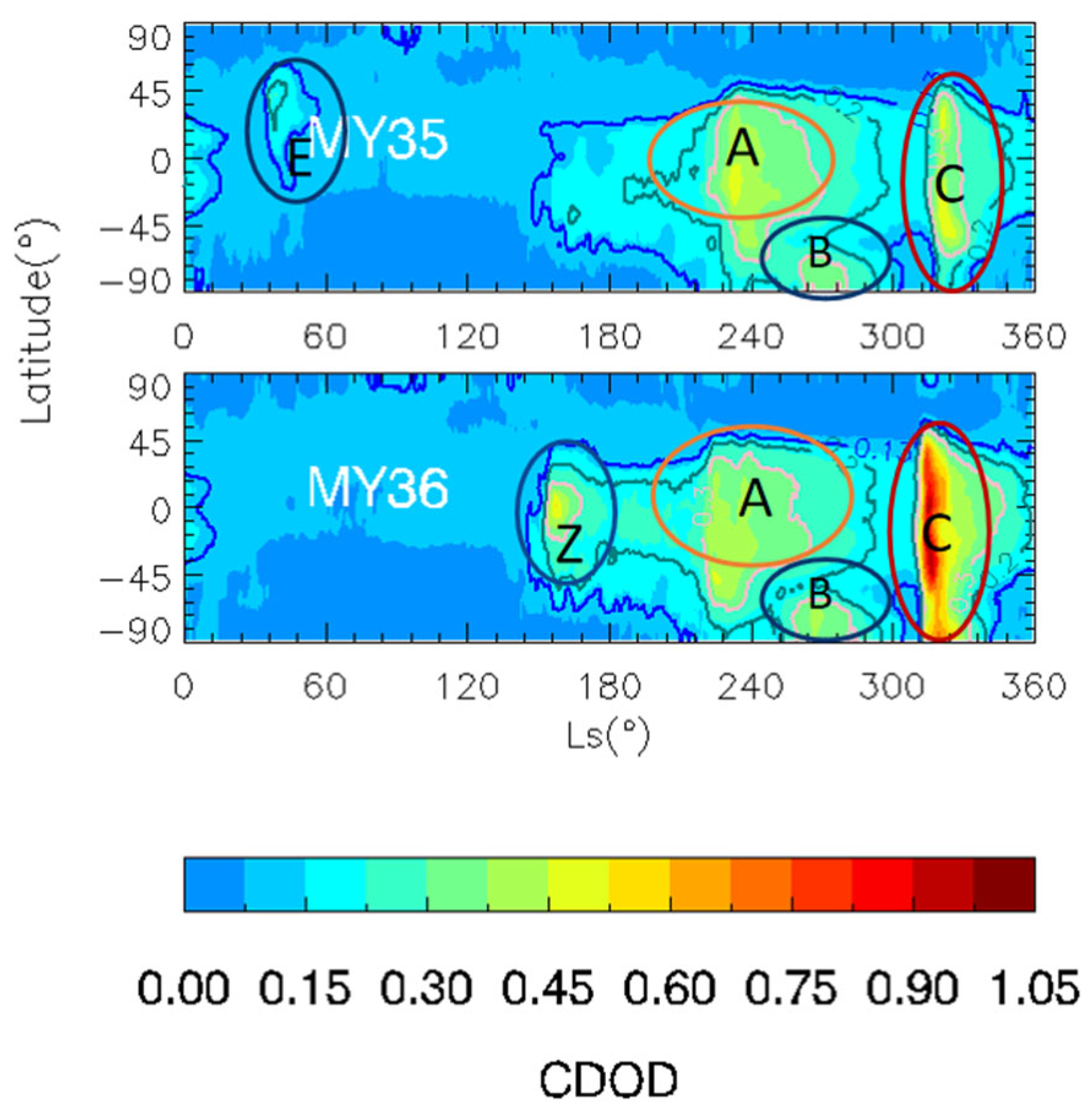

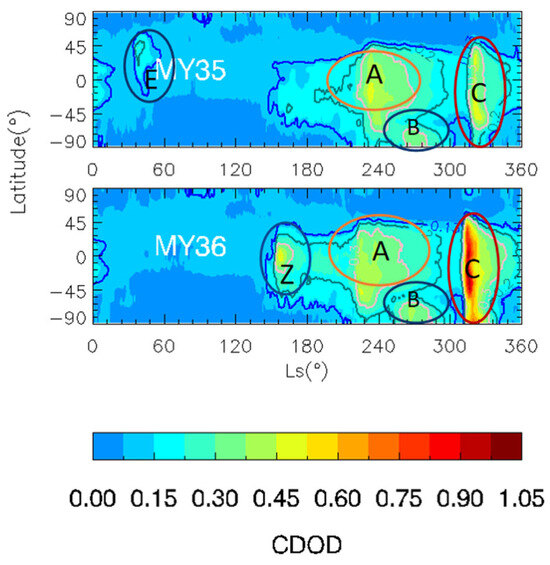

Previous studies have found that the three types of seasonal dust storms (A, B, and C) occur according to certain temporal and spatial distribution patterns during the dusty season [4,17]. As shown in Figure 1, type A storms typically begin in the spring of the Southern Hemisphere (Ls = 205°–235°), last 30°–60° Ls, and end around the summer solstice (Ls = 260°–280°). Their latitudinal range extends from the northern middle latitudes to the southern high latitudes (40°N–90°S). B storms typically start approximately at Ls = 250°–270° after A storms. They have a shorter duration and end near Ls = 270°–285°. Their latitudinal range of influence is small and is confined to the southern high latitudes. C storms begin at Ls = 310°–320°, last 20–40°, and end at Ls = 330°–350°. Their latitudinal range is similar to that of A storms. In addition to the three types of dusty season storms, Z storms begin in some years at approximately Ls = 150°. Martín-Rubio et al. studied the evolution of a Z storm that occurred in MY36 for the first time [12]. As shown in Figure 1, the MY 35 anomalous spring dust storm occurred around Ls = 30°–50°, which is different from all the other storms. In the subsequent discussion, this storm will be referred to as the type E dust storm, in line with previous studies [18,20]. This section focuses primarily on the evolution of the MY 35 E storm, as well as on comparing it with other common types of regional dust storms on Mars.

Figure 1.

Zonal mean CDOD of MY 35 (top) and MY36 (bottom). The type A, B, C, Z, and E storms are marked by circles in different colors.

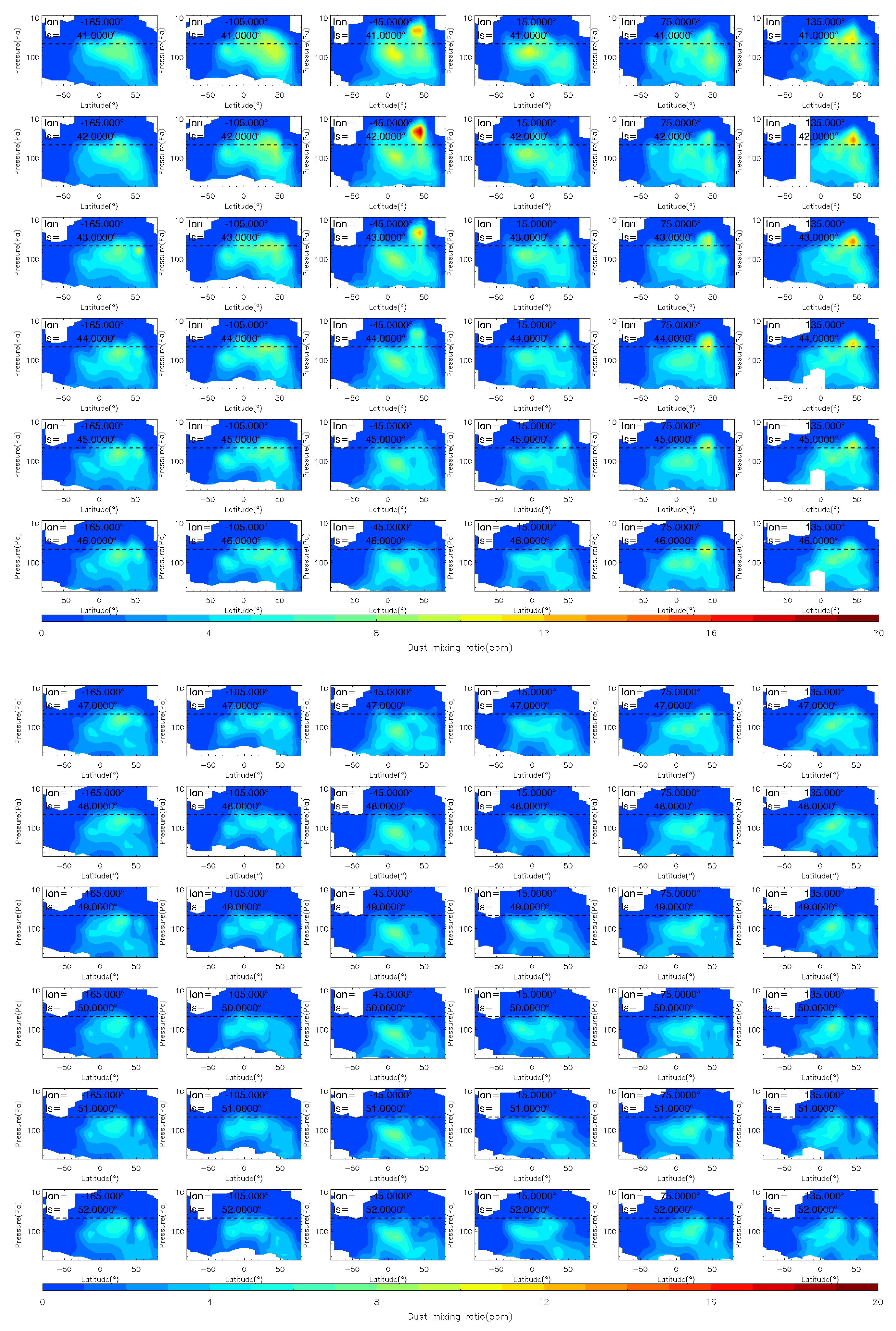

3.1.1. The Horizontal Evolution of MY 35 E Dust Storm

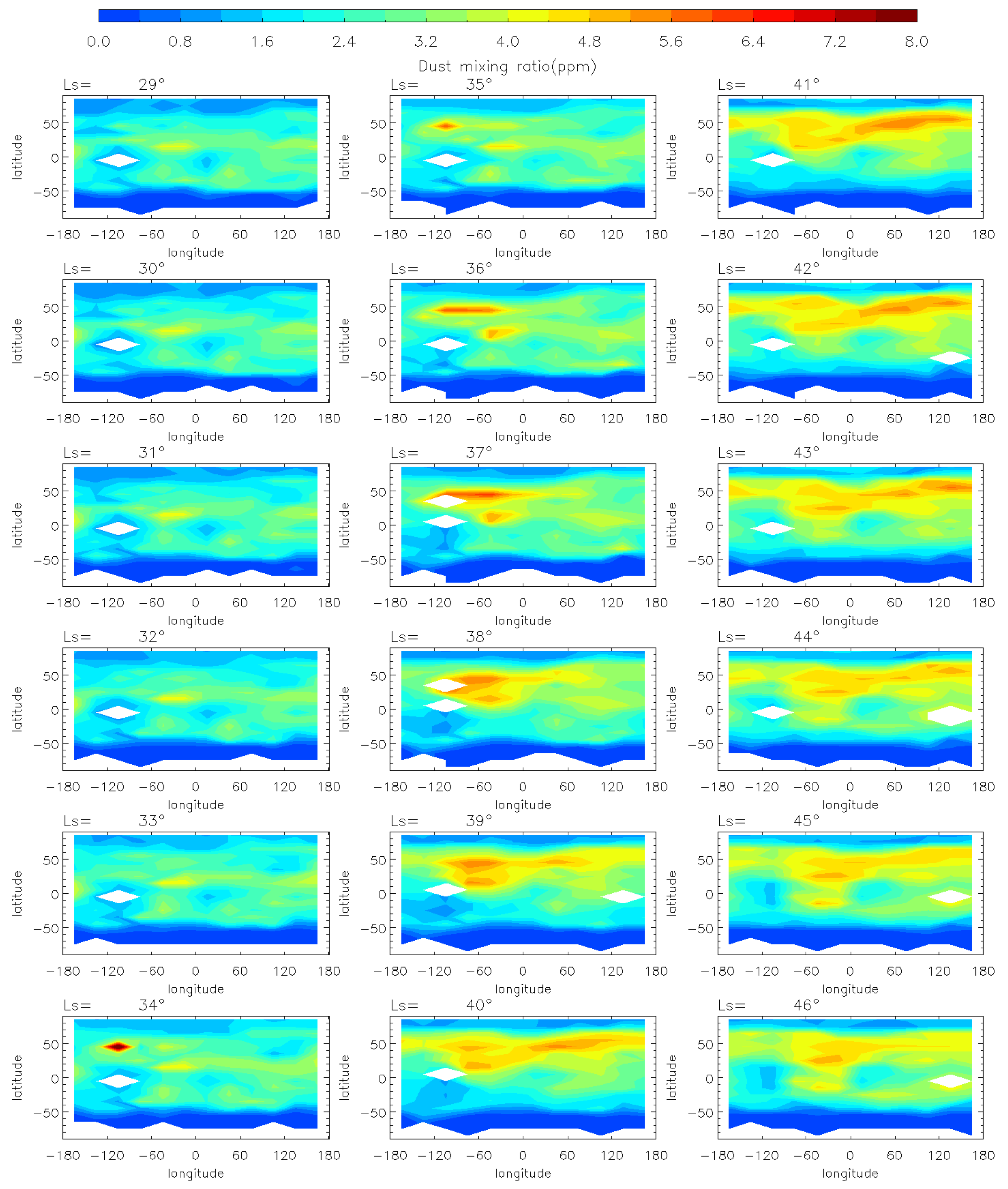

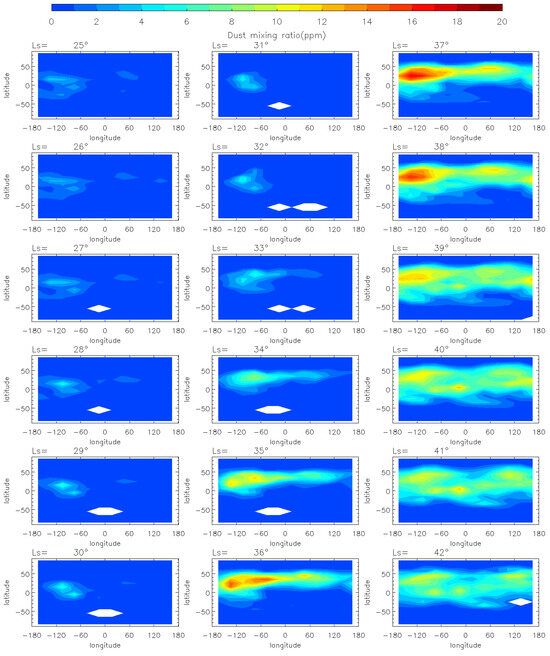

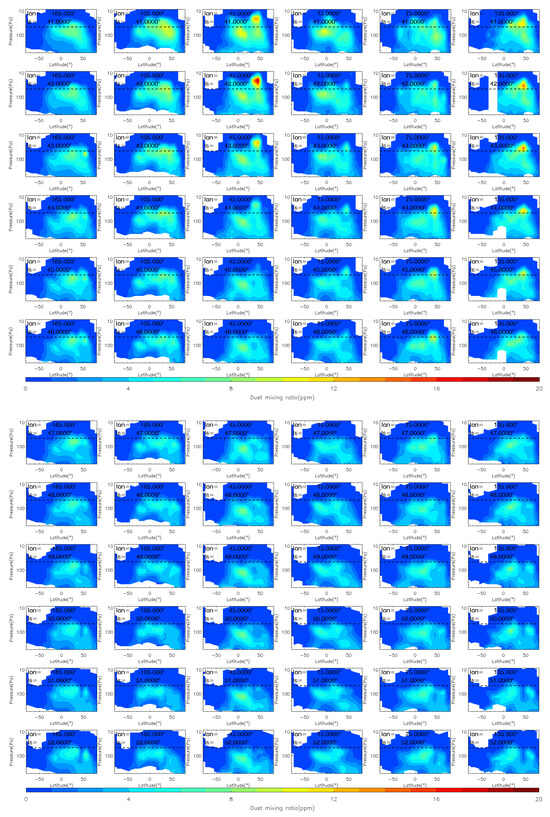

To analyze the evolution of the MY 35 E storm, we show the horizontal distribution of dust mass mixing ratio at 50 Pa (~25 km) at local time 3 a.m. in Figure 2 and Figure 3. The pressure level of 50 Pa has been commonly used to study regional dust storms on Mars because it allows for the detection of significant temperature increases and dust accumulation associated with dust storms [4,12,37]. The data at 3 a.m. is used instead of 3 p.m. because the latter would affect the analysis due to missing values at low latitudes [38]. According to previous studies [12,39], we divide the evolution of the E storm into four phases: pre-storm (Ls = 25°–32°), onset (Ls = 33°–35°), expansion (Ls = 36°–40°), and decay (Ls = 41°–50°) phases. Generally, during the pre-storm phase, dust mass mixing ratio at 50 Pa is globally low (below 5 ppm), with only localized, small-scale dust activity. During the onset phase, the dust mass mixing ratio gradually increases above 8 ppm. During the expansion phase, dust spreads from local areas to a regional scale, reaching maximum latitudinal coverage. Then, it enters the decay phase, during which the dust mass mixing ratio gradually decreases to a lower level similar to that in the pre-storm phase.

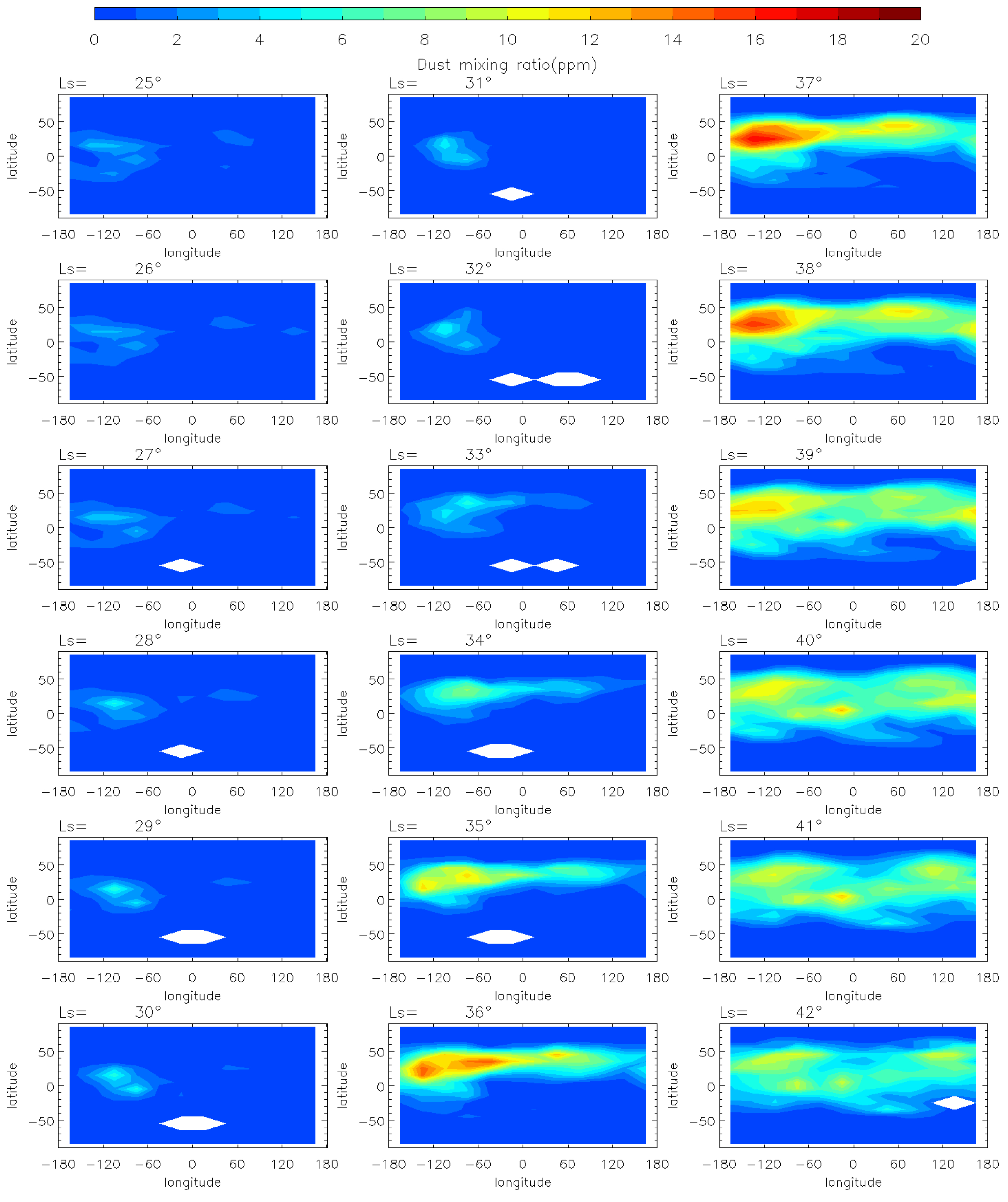

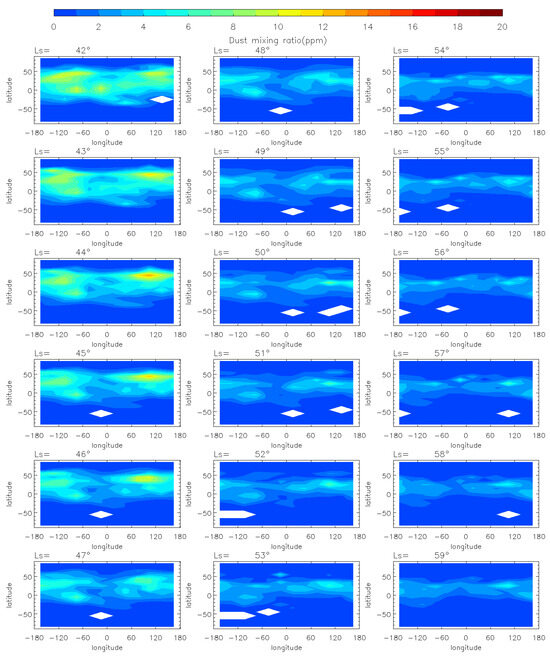

Figure 2.

The MCS dust mass mixing ratio variation at 50 Pa during the pre-storm (Ls = 25°–32°), onset (Ls = 33°–35°), and expansion (Ls = 36°–40°) phases of the MY 35 E storm, the white regions in the figure represent missing values in the observations.

Figure 3.

The MCS dust mass mixing ratio variation at 50 Pa during the decay phase (Ls = 41°–50°) of the MY 35 E storm, the white regions in the figure represent missing values in the observations.

During the pre-storm phase of the MY 35 E storm (Figure 2), dust mass mixing ratio remains low (below 1 ppm) over most of the planet. Small dust clusters are near 100°W at low latitudes in the Northern Hemisphere, but with a low dust mass mixing ratio (approximately 5 ppm), suggesting that small-scale dust activity may have occurred in the region. The onset phase is characterized by an increase in dust mass mixing ratio, with dust originating from 100°W spreading eastward in the middle latitudes (30°N–50°N) and westward in the low latitudes (0°–30°N). The direction of dust spreading is in accordance with the zonal wind field direction simulated by the LMD-GCM, as demonstrated and discussed in Section 3.3 of this paper. This suggests that the zonal wind field plays a substantial role in the dust transport during the evolution of the E storm. At Ls = 35°, the dust has gradually spread across all longitudes in the middle and low latitudes of the Northern Hemisphere. And the dust mass mixing ratio near the origin location increases to over 8 ppm. The E dust storm enters its expansion phase after Ls = 36°. The dust begins to spread southwards, reaching maximum latitudinal coverage at Ls = 40°, the peak time of the MY 35 E storm. The maximum latitudinal coverage ranges from 30°S to 60°N, affecting most of the planet except the North and South Poles and the southern middle latitudes. In the entire evolution period, the dust mass mixing ratio peaks near the origin location at Ls = 37°. The decay phase begins at Ls = 41°, when the dust coverage gradually decreases and the dust mass mixing ratio declines (Figure 3). A new increase in dust mass mixing ratio appears in the 50°N, 100°E region at approximately Ls = 44°, but it is shorter-lived and has a smaller impact area. This increase may have been caused by a small-scale dust event formed during the decay phase of the E dust storm. Subsequently, the dust mass mixing ratio declines globally to below 6 ppm, returning to a level similar to that before the dust storm.

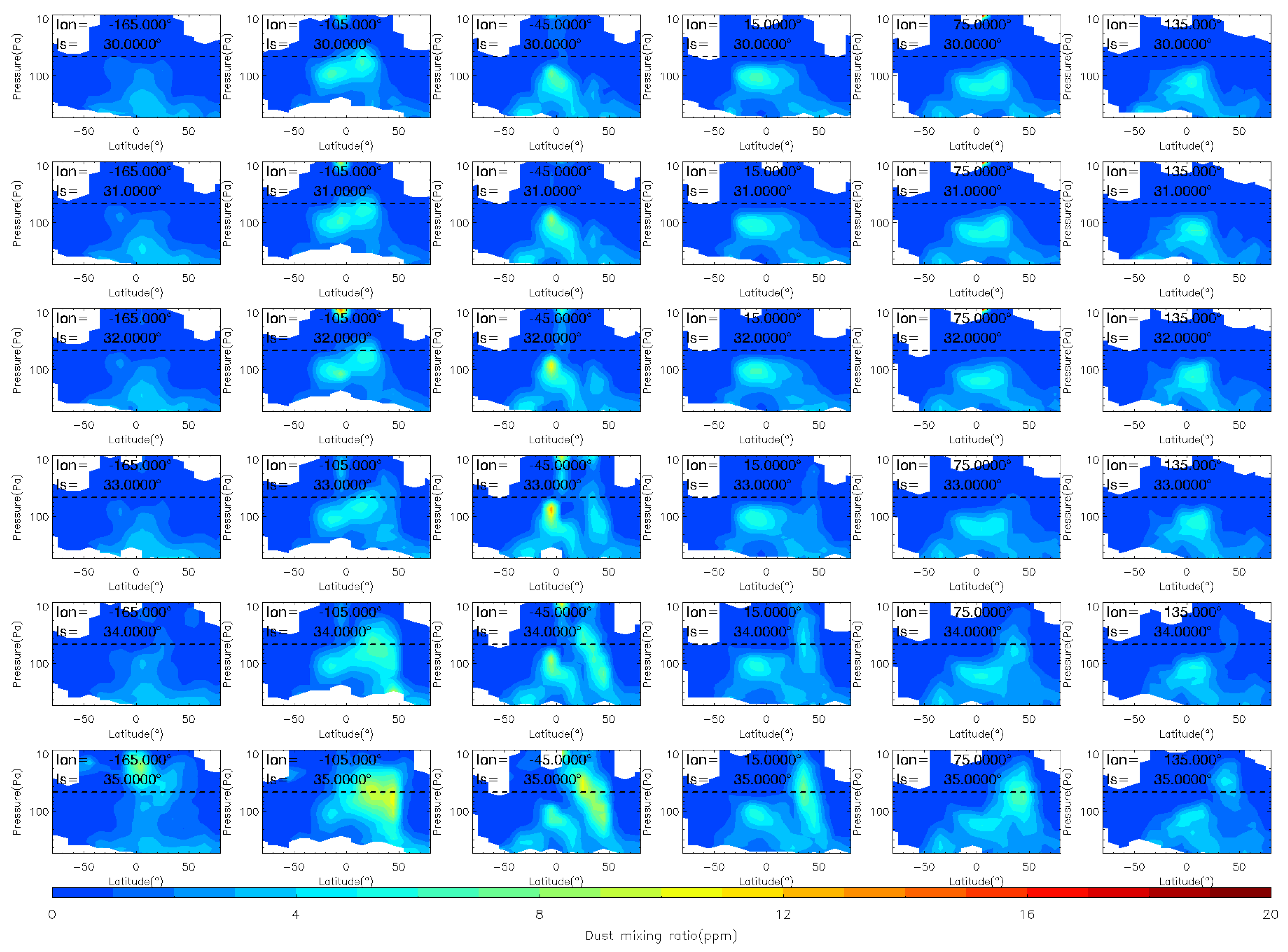

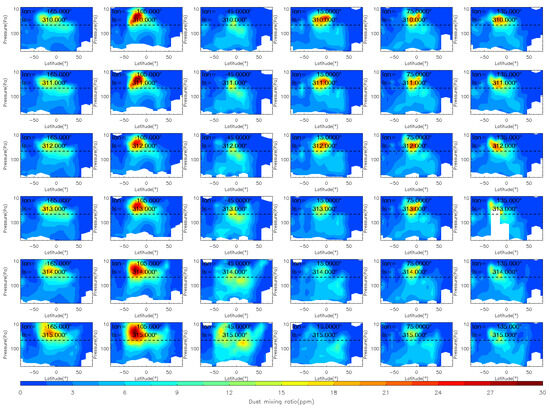

3.1.2. The Vertical Evolution of MY 35 E Storm

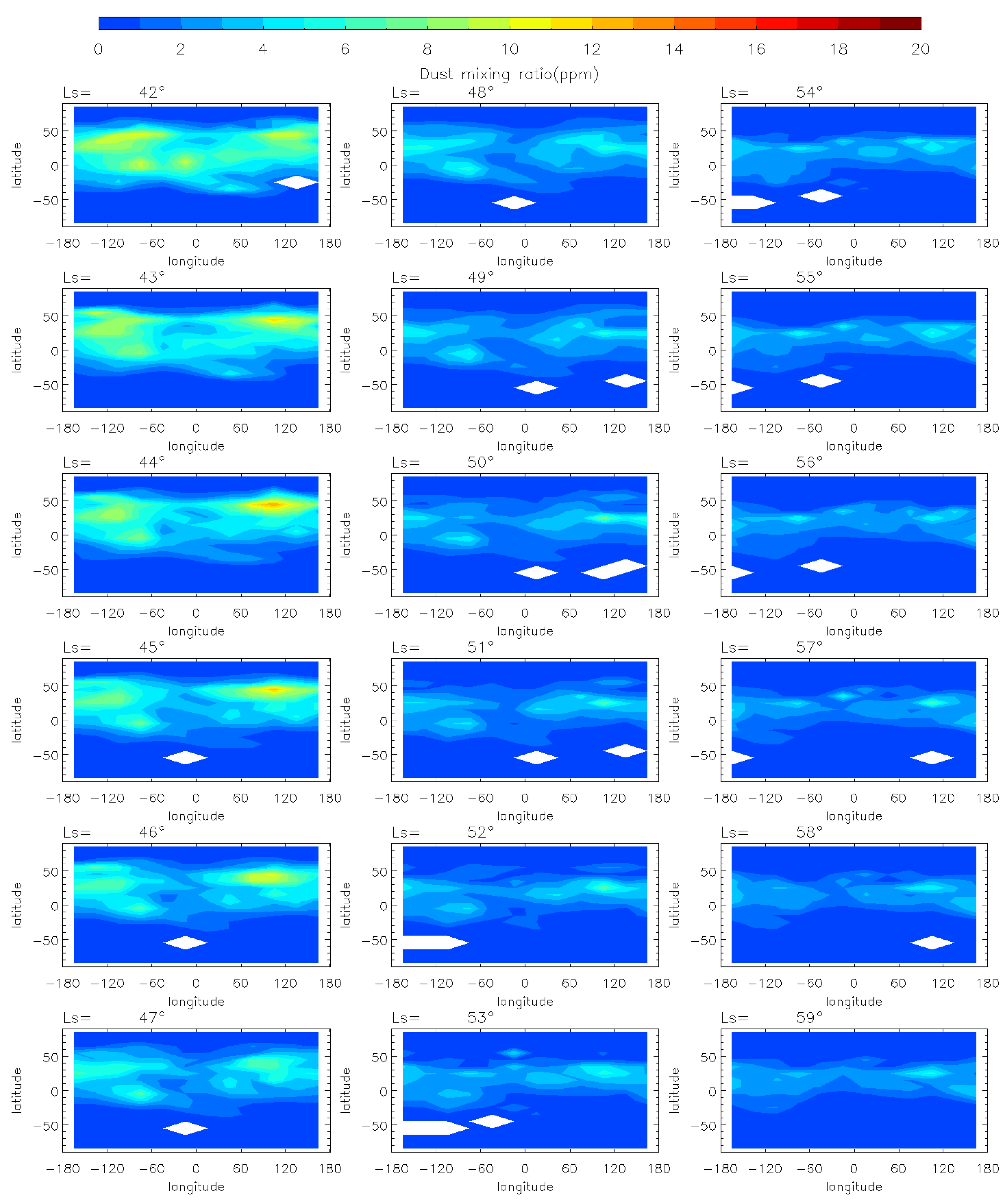

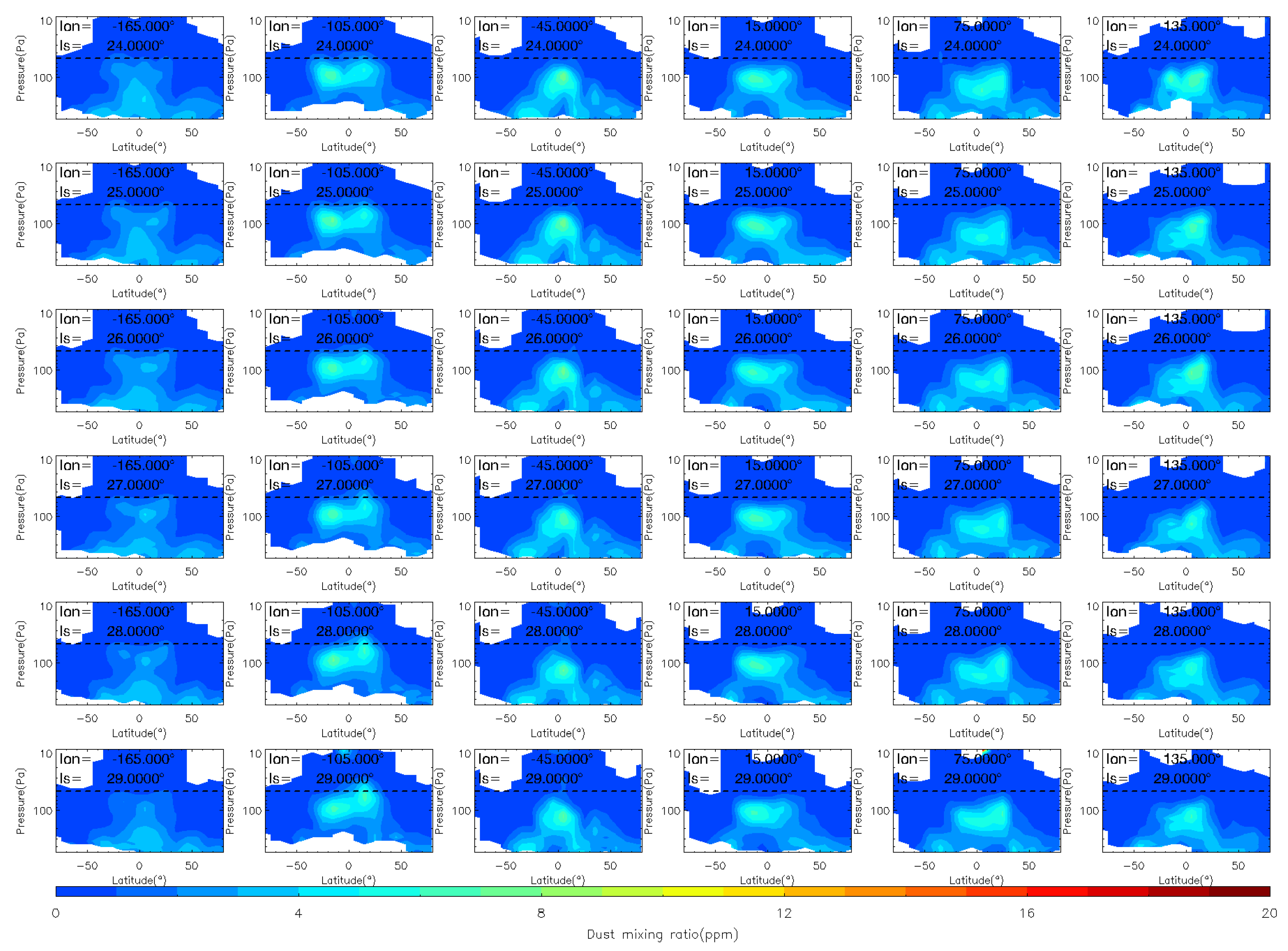

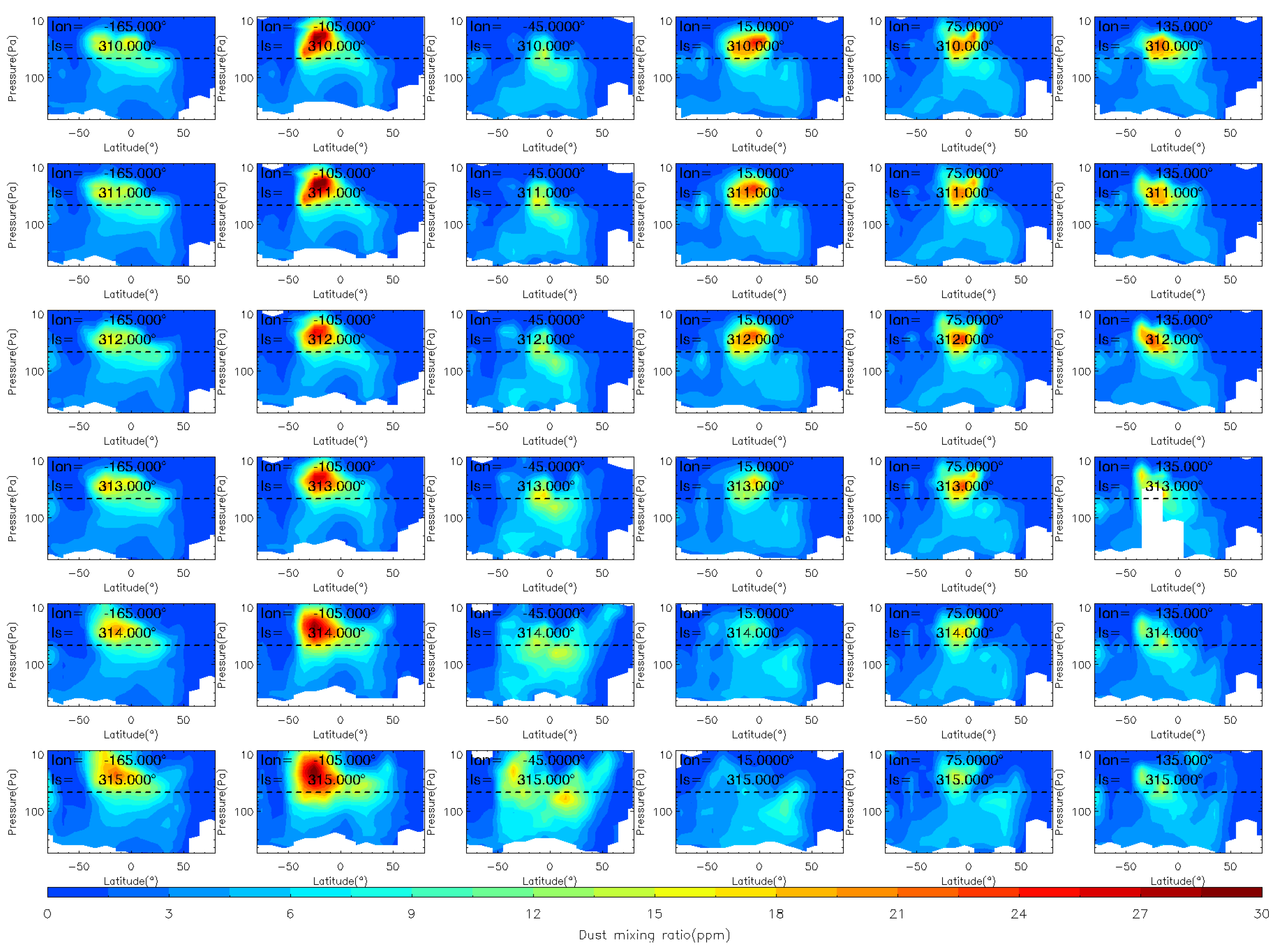

To analyze the evolution of the MY 35 E storm in more detail, we show the dust vertical distribution at six longitude bands (165°W, 105°W, 45°W, 15°E, 75°E, and 135°E) during the storm’s four phases in Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 6, in a similar way as previous studies [12]. The 105°W is located near the origin area of the MY 35 E storm. The dashed horizontal line in the figures indicates a height of 50 Pa (~25 km). Notably, elevated atmospheric dust loading can significantly compromise the quality and completeness of remote sensing analyses [40]. As demonstrated in Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 6, notable data gaps are observed at low altitudes near the surface. These omissions are attributable to the limitations imposed by high dust concentrations, whereby limb measurements were difficult or impossible to retrieve because of the high dust loading [41].

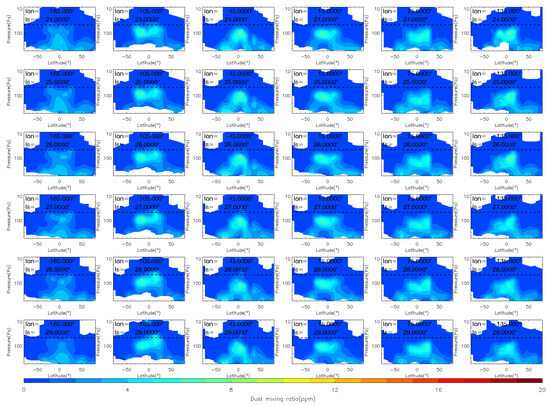

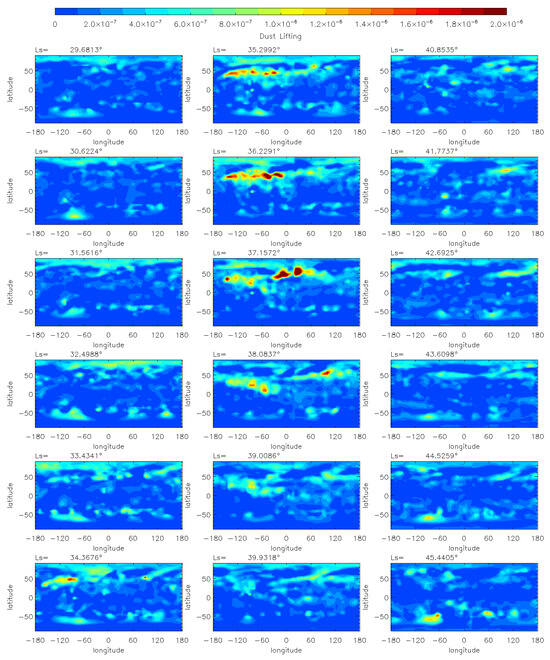

Figure 4.

The vertical distribution of MCS dust mass mixing ratio during the pre-storm (Ls = 25°–32°), onset (Ls = 33°–35°) phases of the MY 35 E storm. The dashed horizontal line in the figures indicates a height of 50 Pa (~25 km), the white regions in the figure represent missing values in the observations.

Figure 5.

The vertical distribution of MCS dust mass mixing ratio during the expansion (Ls = 36°–40°) phase of the MY 35 E storm. The dashed horizontal line in the figures indicates a height of 50 Pa (~25 km), the white regions in the figure represent missing values in the observations.

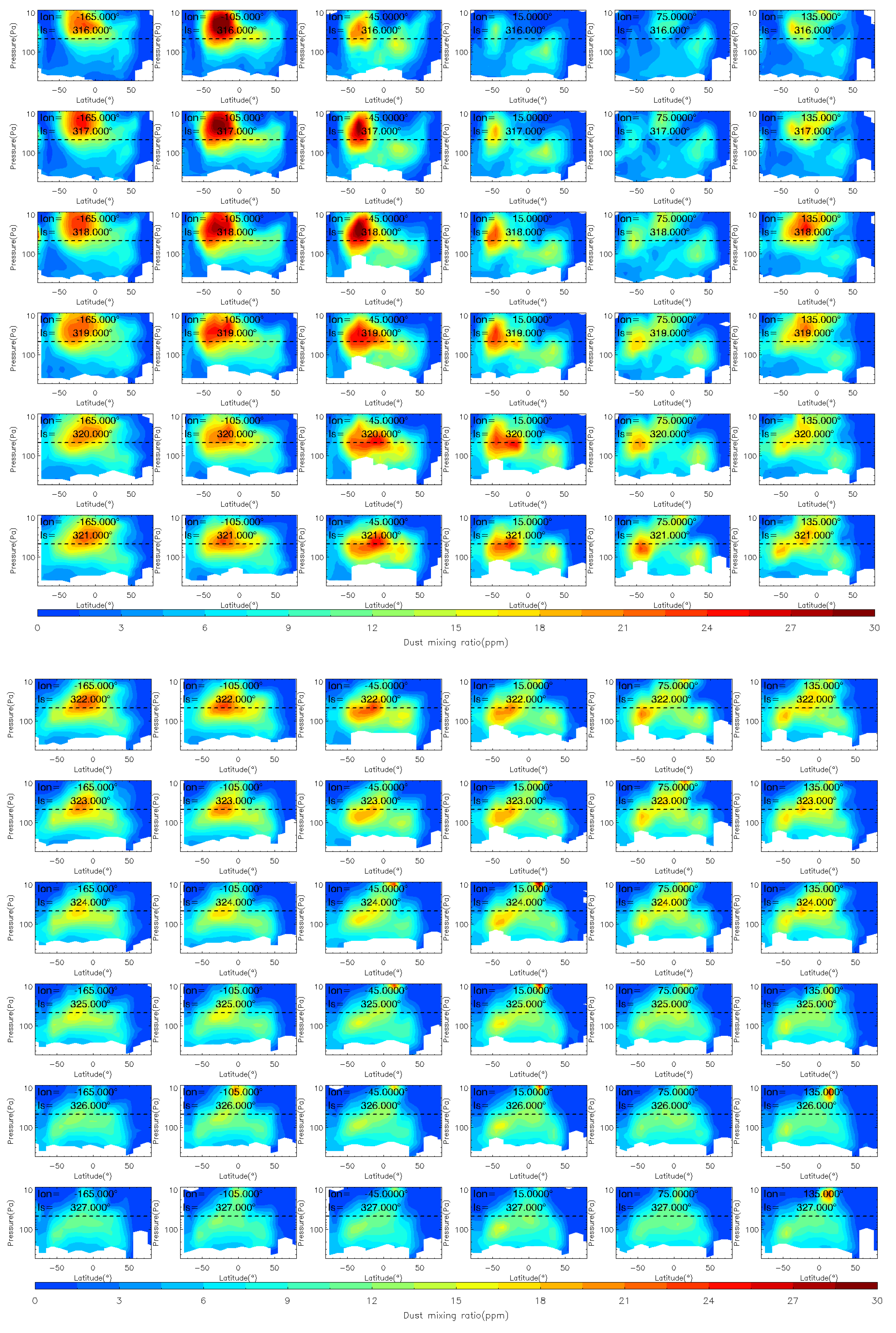

Figure 6.

The vertical distribution of MCS dust mass mixing ratio during the decay (Ls = 41°–50°) phase of the MY 35 E storm. The dashed horizontal line in the figures indicates a height of 50 Pa (~25 km), the white regions in the figure represent missing values in the observations.

During the pre-storm phase Ls = 25°–32°, there are minor vertical changes and no significant dust lifting, which indicates that dust activity in the atmosphere is relatively calm during this period. The distribution of dust across latitudes and altitudes is consistent with the typical characteristics of that during the northern spring season [38]. Specifically, dust is more prevalent in low-latitude regions below an altitude of 50 Pa; in mid-latitude regions, it is distributed below an altitude of 200 Pa; and in high-latitude regions, it is less prevalent. Overall, dust is distributed symmetrically to the north and south of the equator because the meridional circulation is nearly symmetric relative to the equator near the equinoxes [38]. Additionally, the distribution of dust at different longitudes is nearly consistent, suggesting a relatively uniform distribution in the zonal direction. The onset phase is marked by the beginning of dust lifting above 50 Pa, which occurs when Ls = 33°. During this phase, dust is primarily lifted in the region between 105°W and 45°W, near latitudes between 0° and 50°N. At Ls = 35°, dust reaches its maximum altitude in the region between 105°W and 45°W, and then starts to appear in other longitude regions. During this phase, the airborne dust increases primarily in the middle and low latitudes of the Northern Hemisphere (0°–50°N).

At Ls = 36°, the E dust storm enters the expansion phase and begins to spread meridionally. After the E storm begins, dust has accumulated in the northern middle latitudes and heated the atmosphere there. This disrupts the meridional circulation that transports from the equator to the poles, and enhances the cross-equator circulation that transports from the northern to the Southern Hemisphere [20]. Driven by this abnormal meridional circulation, dust gradually spreads from the northern low and middle latitudes to the Southern Hemisphere, and expands to 30°S at Ls = 40°. The airborne dust begins to fall after Ls = 41°, indicating that the dust storm has entered its decay phase. During this phase, the dust mass mixing ratio decreases, and the maximum dust height gradually falls below 50 Pa. However, a dust lifting event is observed above 50 Pa near 45°W, 45°N at Ls = 42°. Unlike events in the onset and expansion phases, this event is short-lived and does not produce large accumulations of dust. This smaller dust accumulation may be produced by deep convection during dusty conditions [15]. The decay phase is typically longer than the other phases, with an overall trend of gradual decrease in dust mass mixing ratio. Eventually, the dust level returns to a calm state similar to that before the onset phase.

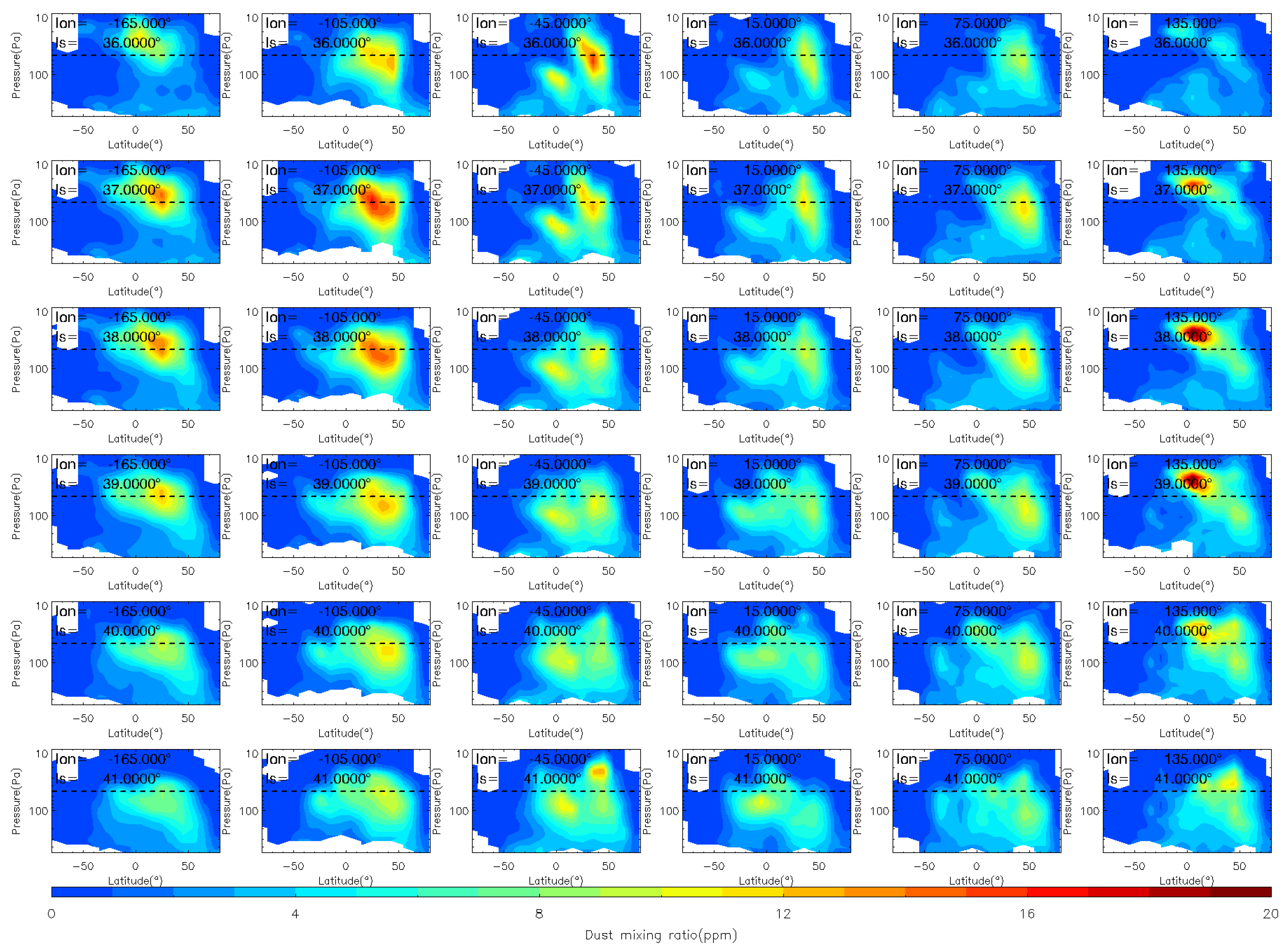

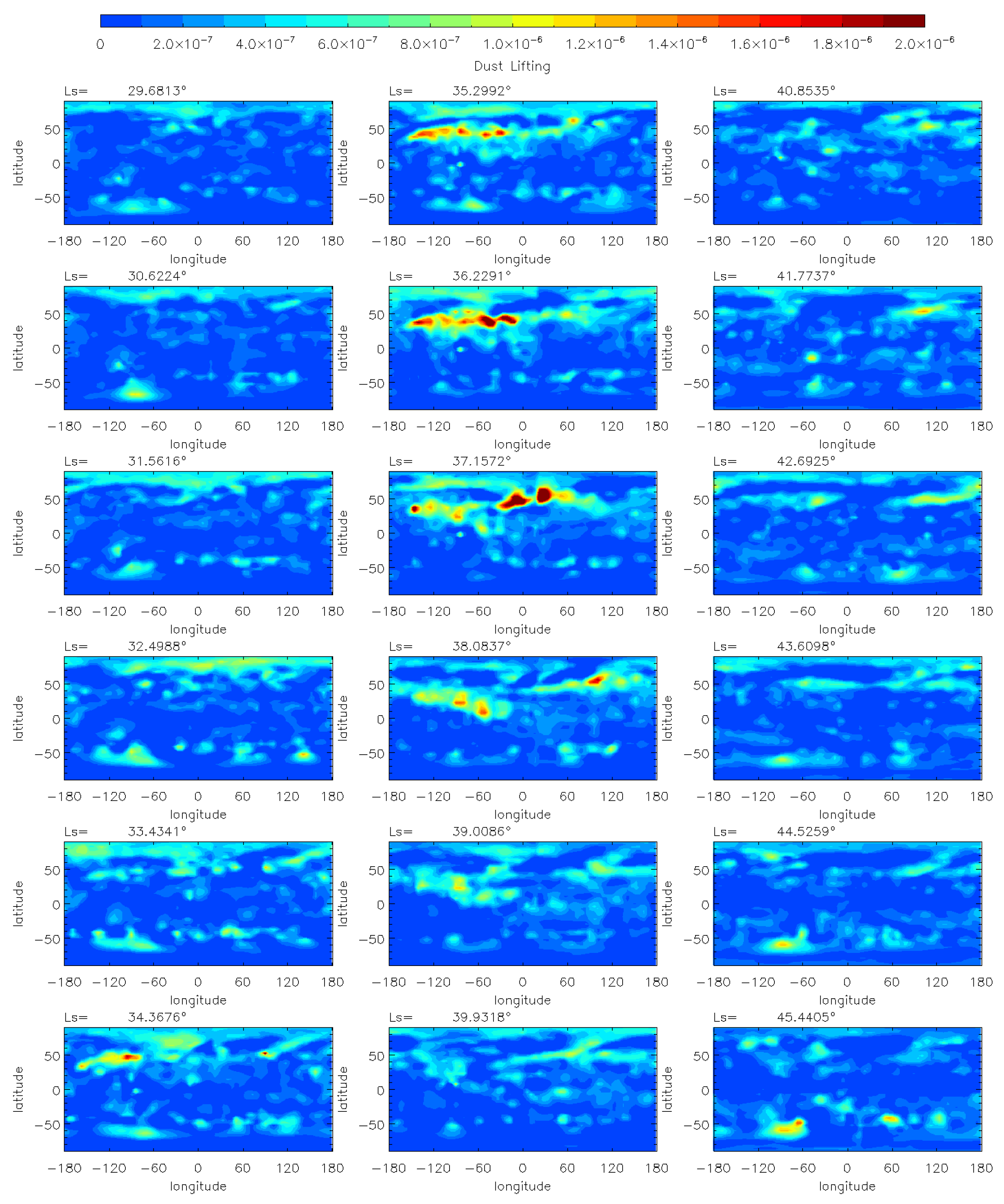

3.1.3. The Surface Dust Source of the MY 35 E Dust Storm

Based on the horizontal and vertical evolution of the dust mass mixing ratio as discussed above, the MY 35 E storm initially originates in the Northern Hemisphere in the low and middle latitudes near 100°W, and then spreads to other longitude and latitude ranges. To investigate the variation in the dust source region during the E storm, this section performs a further analysis combining the dust lifting rate distribution simulated by the LMD-GCM (Figure 7) and the MCS dust mass mixing ratio distribution at a lower altitude of 288 Pa (~8 km) (Figure 8). The 288 Pa level is the lowest altitude at which the MCS data is relatively complete, below which the data is sporadic, especially at low latitudes due to the opacity of the dusty atmosphere.

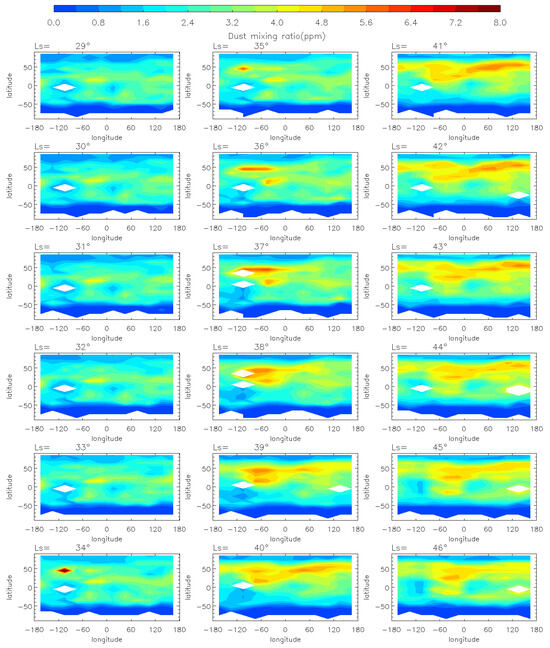

Figure 7.

The LMD-GCM simulated daily mean dust lifting rate (s−1) during the MY 35 E storm.

Figure 8.

The variation in MCS dust mass mixing ratio at 288 Pa during the MY 35 E dust storm, the white regions in the figure represent missing values in the observations.

As shown in Figure 7, during the onset phase of the dust storm (Ls = 33°–35°), there is a significant increase in dust lifting in the region near 100°W, 50°N, corresponding to the origin of the MY 35 E storm. Subsequently, during the period Ls = 35°–38°, there are multiple increases in dust lifting within the range of 0°–70°N and 120°E–120°W, indicating that the dust lifting source gradually expands beyond the origin of the dust storm. As for the MCS observations, there is also evidence of an obvious increase in dust at 288 Pa within the 0°–70°N latitude and 120°E–120°W longitude range during the dust storm’s onset and expansion phase (Ls = 33°–40°), which is consistent with the simulation results. Furthermore, a comparison of the dust distribution at 50 Pa (~25 km) (Figure 2 and Figure 3) and 288 Pa (~8 km) (Figure 8) reveals that the coverage of the dust increase is much larger at 50 Pa than at 288 Pa. This corresponds to the horizontal diffusion process when dust is transported to higher altitudes.

The above simulations and observations suggest that the dust source region also evolves with the E dust storm. The primary dust lifting region begins near the 100°W, 50°N. Then, it gradually extends to cover a range of latitudes between 0° and 70°N and longitudes between 120°E and 120°W. The expansion of the dust lifting region may be due to several factors. After Ls = 30°, the northern polar ice cap retreats to a latitude of around 65°N [42]. The strong temperature gradient at the edge of the ice cap increases the baroclinic instability, which further causes strong surface winds to form in the middle and high latitude regions (50°–70°N) of the Northern Hemisphere [43]. This may explain the source of the dust lifting near 50°N. Additionally, once the dust storm has begun, the airborne dust absorbs solar radiation, heating the atmosphere and increasing the temperature gradient at the edge of the dust storm region. This may also enable the dust lifting region to expand further, extending toward other latitudes.

3.2. Comparison with Other Types of Regional Dust Storms

As an unusual dust storm occurring in the Northern Hemisphere during the spring season, the MY 35 E storm may differ from other types of Martian regional dust storms. This section uses the MCS data to compare the evolution and thermal impact of the E storm with those of other types of regional dust storms on Mars, including the similarities and differences in their respective evolutionary processes. The E storm is a large-scale regional event similar to the typical A, B, and C seasonal storms [4]. Compared to the A storm, the duration of the C storm is closer to that of the E storm (about Ls = 15°). The B storm, however, is limited to the high latitudes of the Southern Hemisphere, quite different from the E storm. In addition to type A, B, and C storms that occur during the perihelion season on Mars, another type of regional dust storm, type Z, occurs during the end of the aphelion season [15], which is similar in size and occurrence time to the E storm. Therefore, this section primarily compares the E storm to the C and Z storms.

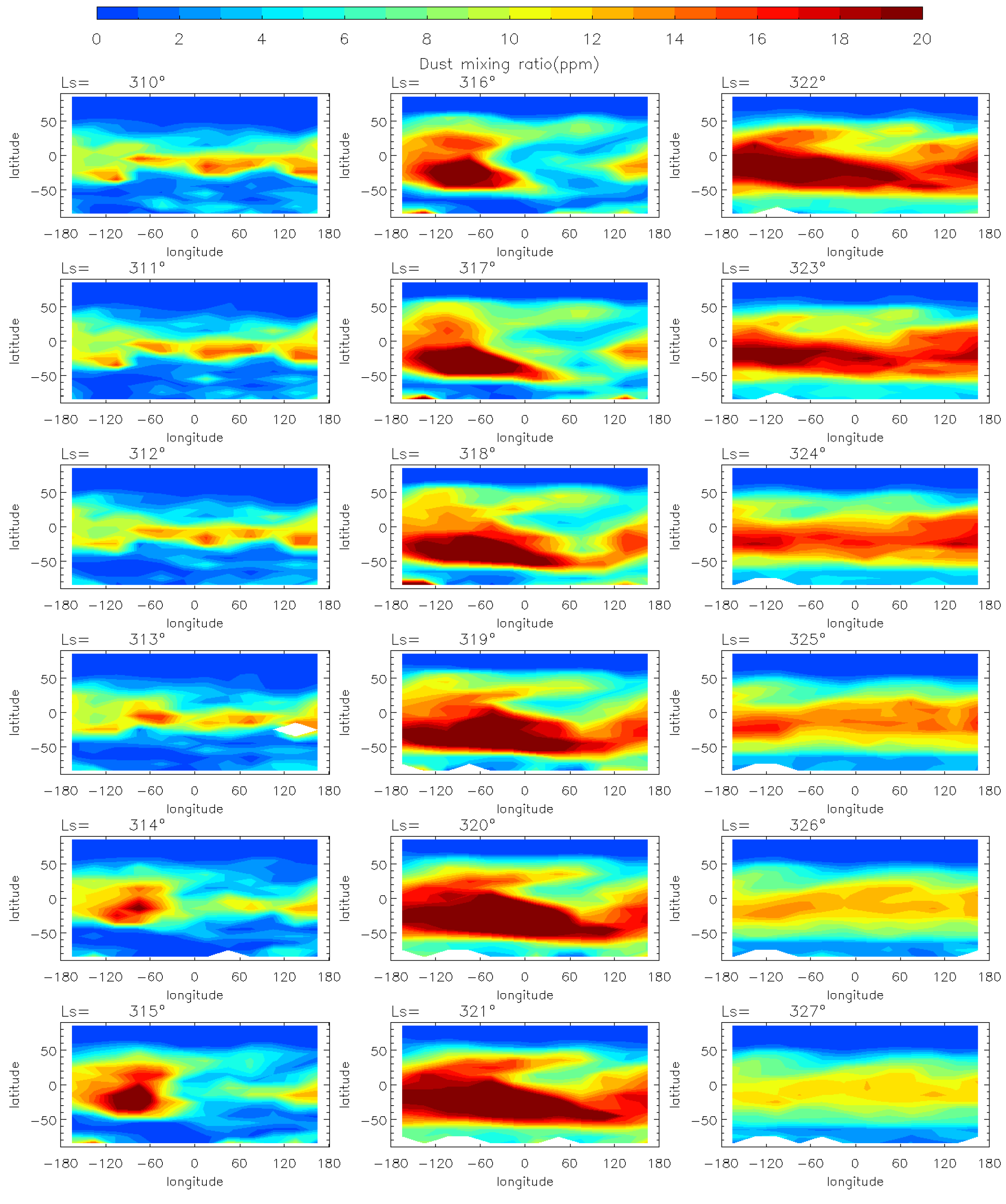

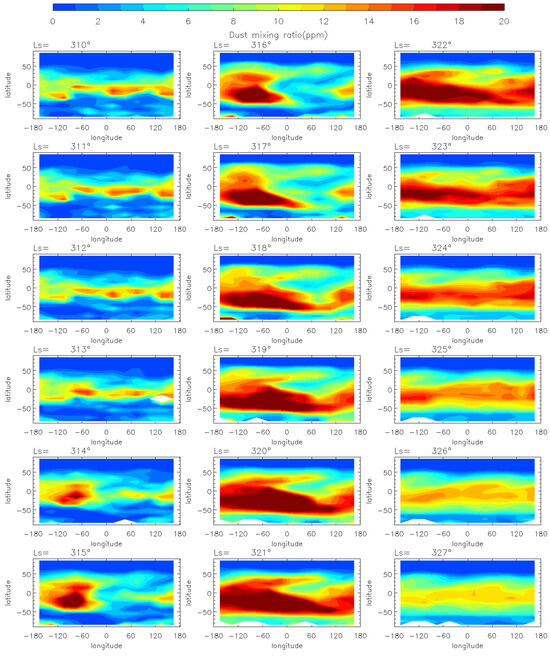

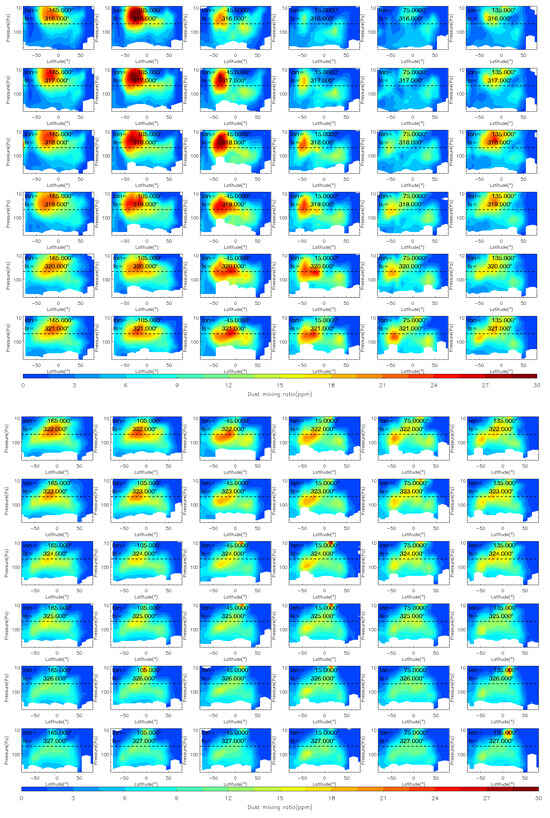

3.2.1. The Comparison of Dust Storm Evolution

As for the comparison with the C Storm, Figure 9 and Figure 10 show the horizontal and vertical evolution of the dust mass mixing ratio during the MY 35 C Storm. The dust mass mixing ratio is higher during the pre-storm phase (Ls = 310°–312°) of the C storm than that of the E storm, which indicates that the background dust content in the atmosphere is higher during the C storm. This is because Mars is in its dusty season at this time, when there is a high concentration of dust in the atmosphere, some of which is lifted to high altitudes. The MY 35 C storm originates near 60°–100°W in the southern middle to low latitudes (0°–50°S). Its origin longitude location is close to that of the MY 35 E dust storm, while its latitude is equatorially symmetric with that of the E storm. The onset phase of the C storm occurs at Ls = 313°–316°. The duration of the onset phase is similar to that of the E storm (Ls = 33°–35°). Similarly, dust spreads primarily westward in the low latitudes and eastward in the middle latitudes, gradually reaching the full range of longitudes. Vertically, the C storm reaches a higher altitude than the E storm. The amount of dust at 50 Pa is greater, partly due to the higher background atmospheric dust content during the C storm compared to the E storm. Additionally, the C storm occurs closer to perihelion when insolation is stronger and atmospheric activity, such as deep convection, is more intense [15].

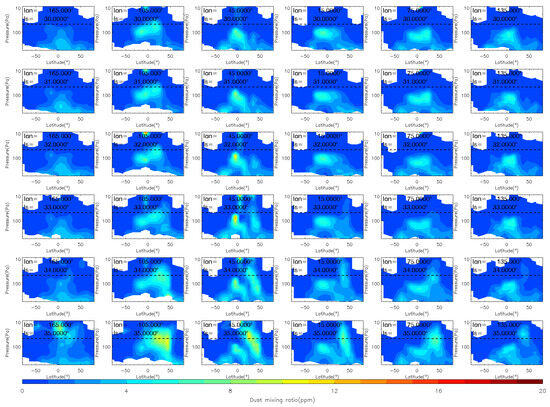

Figure 9.

The MCS dust mass mixing ratio variation at 50 Pa during the MY 35 C storm (Ls = 310°–327°), the white regions in the figure represent missing values in the observations.

Figure 10.

The vertical distribution of MCS dust mass mixing ratio during the MY 35 C storm (Ls = 310°–327°). The dashed horizontal line in the figures indicates a height of 50 Pa (~25 km), the white regions in the figure represent missing values in the observations.

The MY 35 C storm expansion phase is Ls = 317°–321°, similar in duration to that of the E storm. In contrast, the C storm covers a wider latitudinal range than the E storm, with dust spreading northward to other latitudes between 50°N and 50°S during the expansion phase. This is partly because Mars is in its perihelion season when the C storm occurs, resulting in stronger solar radiation and energy input. Additionally, the dichotomy of the terrain between Mars’ northern and Southern Hemispheres leads to stronger meridional circulation, transporting dust from south to north [44]. The decay phase of MY 35 is Ls = 322°–333°, which is slightly longer than that of the E storm. In general, the E storm contains less dust and covers a smaller area than the C storm. However, the spatio-temporal evolution characteristics of the two types of dust storms are similar. The origin and evolution of the two dust storms show north–south mirror symmetry with respect to the equator due to differences in the subsolar position and the direction of the meridional circulation [18]. The two dust storms have similar evolutionary patterns, which indicates that similar dynamical forcing and responses may be triggered by both the E and the C storm.

As for the Z storm, Martín-Rubio et al. (2025) have conducted systematic research on its evolution [12]. We use their results to make a direct comparison between the Z and E storms. Martín-Rubio et al. found that the MY 36 Z storm originates in the southern low latitudes near 45°E–90°E. The onset phase of the MY 36 Z storm is Ls = 150°–156°, which is slightly longer than that of the MY 35 E storm. During the onset phase, the MY 36 Z storm mainly spreads eastward. In contrast, the MY 35 E storm spreads eastward in the mid-latitude region (30°N–50°N) and westward in the low-latitude region (0°–30°N). The difference in the zonal spreading directions of these two dust storms is related to seasonal changes in zonal winds at different latitudes [43]. Significant vertical dust lifting occurs in the 45°E–135°E region at the beginning of the onset phase at Ls = 151°. The lifted dust is higher than that of the MY 35 E storm. The MY 36 Z storm’s expansion phase is Ls = 157°–164°, with symmetrical north–south spread away from the equator, driven by the equatorially symmetric circulation from equator towards the poles. By contrast, the MY 35 E storm mainly spreads southward from its origin. During its peak time, the MY 36 Z storm mainly covers latitudes between 30°N and 30°S, which is a smaller range than that of the MY 35 E storm. Then, the MY 36 Z storm decays at Ls = 165°–180°, which is slightly longer than that of the MY 35 E storm.

In general, regardless of their type, regional dust storms undergo a similar evolutionary process. They typically begin as local dust storms in one or a few locations and progress through three phases: onset, expansion, and decay. During the onset phase, the dust content increases rapidly, accompanied by obvious vertical lifting and zonal spread of the dust. Once the dust has lifted to higher altitudes, it enters the meridional expansion phase, during which the dust begins to spread in north–south directions. Most regional dust storms spread to the full range of longitude but have different latitudinal ranges. After spreading to its maximum extent, the dust begins to gradually settle, and the dust storm enters a decay phase. During this phase, the dust content in the atmosphere slowly decreases until it returns to a state similar to that before the dust storm.

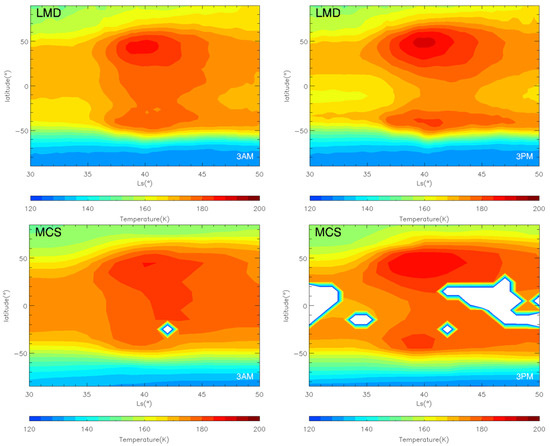

3.2.2. The Comparison of the Thermal Structure During Different Dust Storms

Large regional dust storms can significantly impact atmospheric temperature [4]. We compare the differences in temperature changes during various types of regional dust storms in Figure 11. During the daytime, airborne dust absorbs solar radiation directly, causing an increase in temperature in the dust storm region. Therefore, an increase in atmospheric temperature can be observed during any type of regional dust storm. Compared to regional dust storms during the dusty season, the peak temperature during the MY 35 E storm is relatively low. This phenomenon can be attributed to two primary factors. Firstly, during the aphelion season, Mars receives a comparatively weak amount of insolation, resulting in a lower atmospheric temperature compared to the period during perihelion. Secondly, the E storm occurs during the non-dusty season on Mars, resulting in a lower background dust content in the atmosphere and reduced dust heating compared to the dusty season. Despite an increase in dust content during the E storm, the levels remain significantly lower than those observed during regional dust storms in the dusty season. The low dust levels and relatively weak insolation together result in lower peak temperatures during the MY 35 E storm than during other types of regional dust storms.

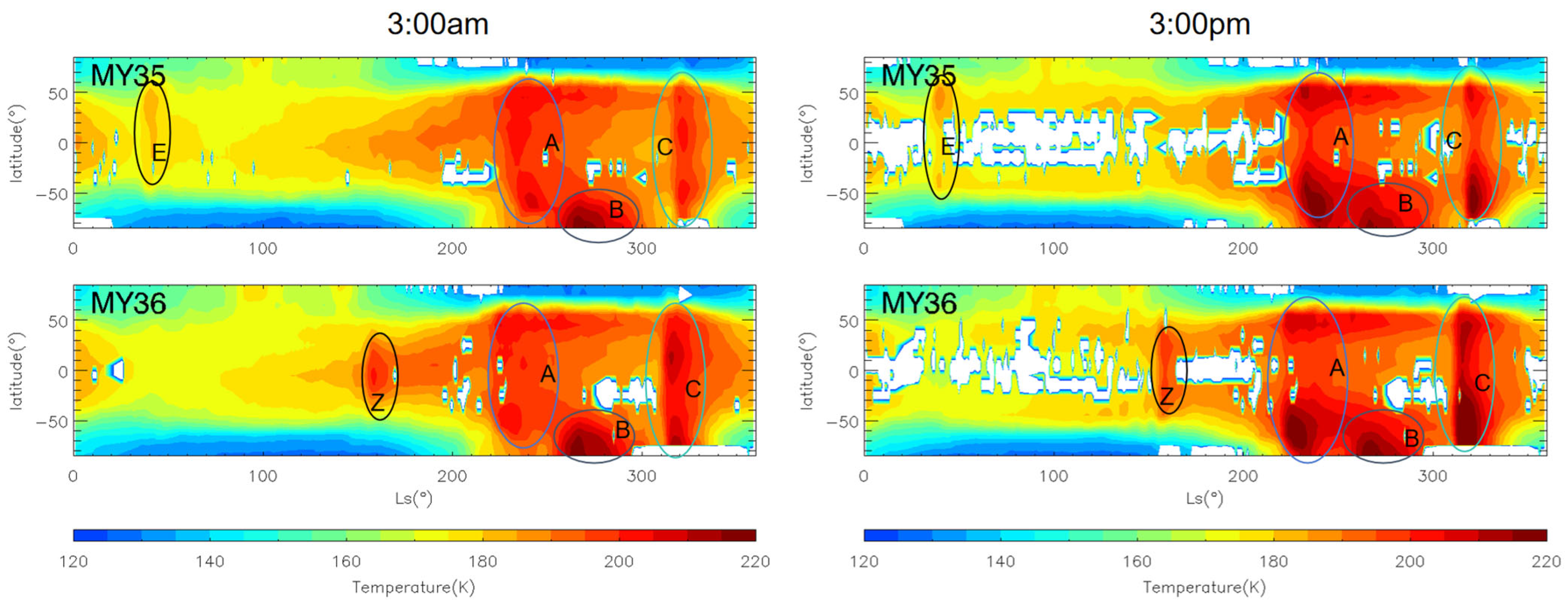

Figure 11.

The nighttime (left) and daytime (right) zonal mean temperature at 50 Pa of MY 35 (top), MY 36 (bottom) observed by MCS. The type A, B, C, Z, and E storms are marked by circles in different colors, the white regions in the figure represent missing values in the observations.

The range of temperature increase for A and C storms spans from the South Pole to 60°N, with a significant increase occurring at 50°N during both daytime and nighttime [4]. This significant Northern Hemisphere response is produced by the adiabatic heating of air in the descending branch of the meridional circulation, which is further enhanced by large dust storms [37]. In contrast, the range of temperature increase during the E storm is from 60°N to 50°S, extending further south than the range of the storm coverage (60°N to 30°S). Specifically, the temperature increases near 40°S, although far lower than the Northern Hemisphere response during A and C storms, indicate an adiabatic heating in the descending branch of the abnormal meridional circulation during the E dust storm [20]. The atmospheric dynamical response during the E storm is weaker than during the A and C storms due to weaker insolation and lower dust content during the aphelion season. As for the MY 36 Z storm, its latitudinal range of temperature increase is between 40°S and 40°N, restricted to low and middle latitudes. The weak atmospheric dynamical response in the high latitudes during the Z storm indicates weaker meridional circulation than during A, C, and E storms.

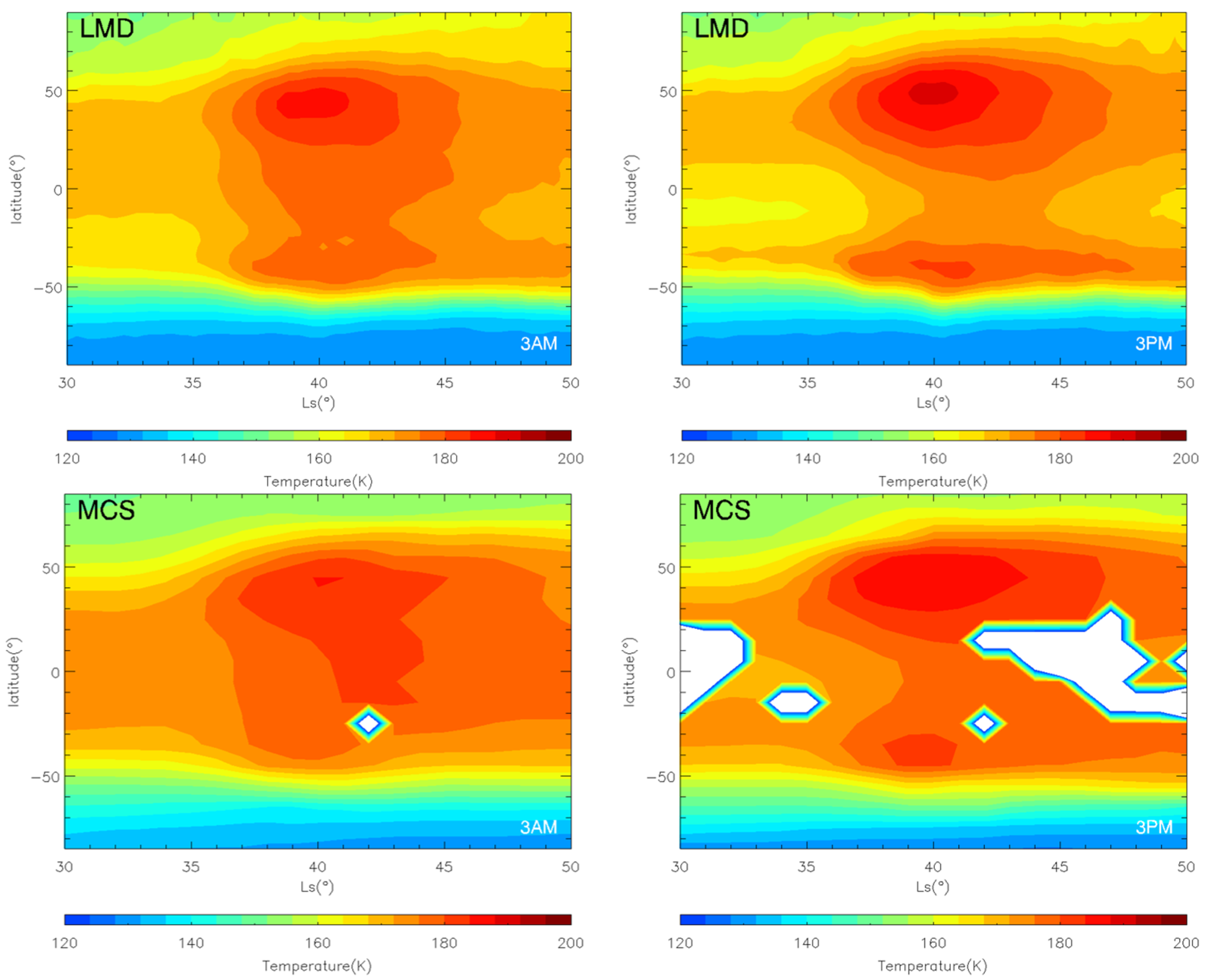

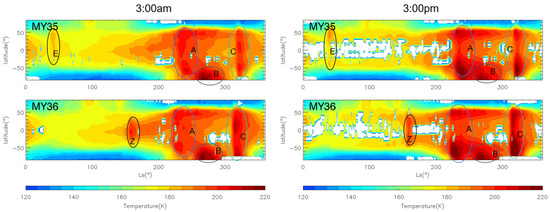

3.3. The Variation in Wind Fields During the MY 35 E Storm

Dust storms can significantly impact large-scale wind fields in the Martian atmosphere, yet there is limited observational data on wind fields [8,32]. Therefore, this section uses simulation results to study wind field changes during the MY 35 E storm. As described in the Data and Methods section of this paper, LMD-GCM is currently one of the most advanced Mars atmospheric models in the world. It uses historical dust observation data to constrain the simulation of atmospheric conditions during large dust storms in specific Martian years. The model’s reliability has been verified using observation data from multiple Mars spacecraft [34]. As an example, Figure 12 shows a comparison between the evolution of global atmospheric temperature during the MY 35 E storm simulated by LMD-GCM and the observed results of MCS. We can see that the LMD-GCM simulation results are in good agreement with the MCS observations. Therefore, we use the LMD-GCM simulation results to investigate wind field changes during the MY 35 E storm hereafter. Due to space limitations, this paper only focuses on changes in the zonal and total wind fields. The meridional wind is much weaker than the zonal wind and is therefore not analyzed specifically. Additionally, the paper focuses on winds in the troposphere below 50 km. This layer has a significant impact on spacecraft landing and takeoff processes due to its greater atmospheric density [8].

Figure 12.

The LMD-GCM simulated (top) and MCS observational (bottom) zonal mean temperature at 50 Pa during the MY 35 E storm; left: 3:00 a.m.; right: 3:00 p.m., the white regions in the figure represent missing values in the observations.

3.3.1. The Zonal Mean Wind Field During the MY 35 E Storm

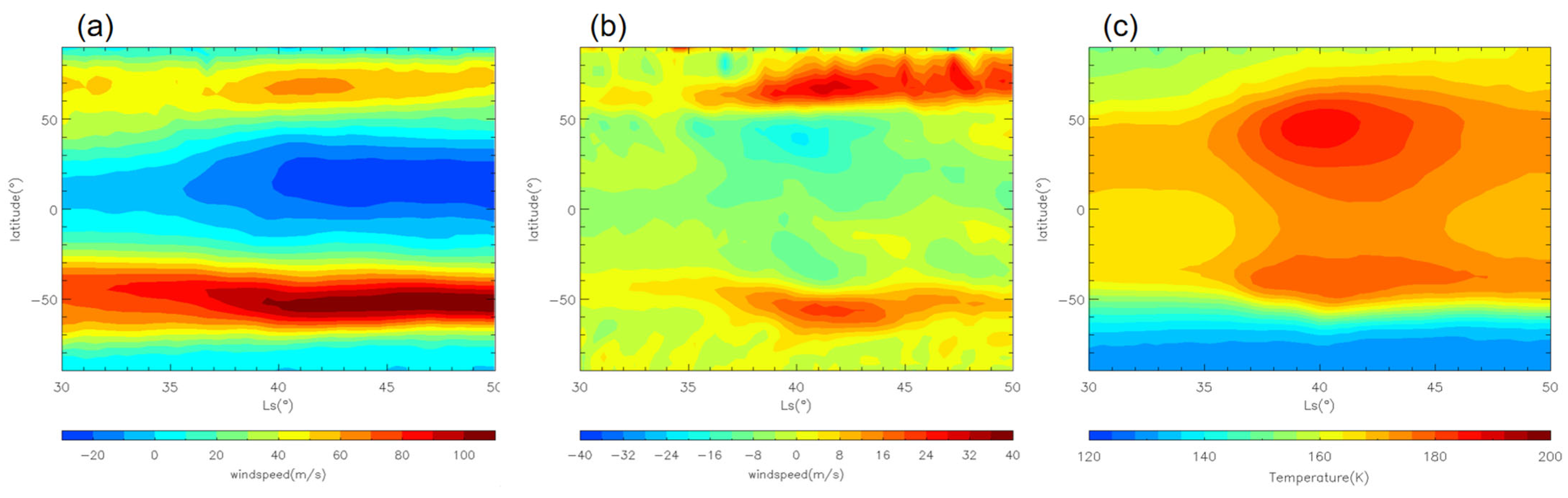

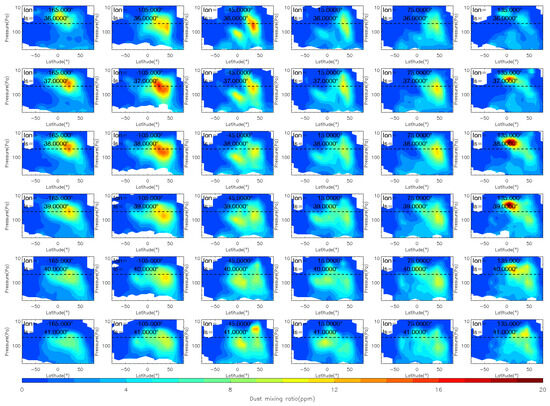

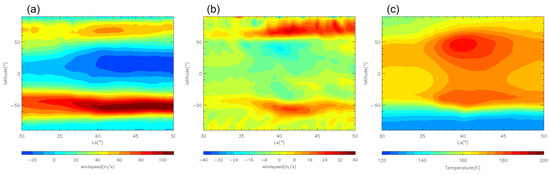

Martian dust storms can alter the thermal structure and affect the entire atmospheric circulation [45]. The atmospheric response to dust is largest at 50 Pa (~25 km) [37]. Therefore, we begin by examining the overall evolution of the tropospheric zonal wind at ~25 km during the E dust storm as an example. As shown in Figure 13a,b, during the MY 35 E storm, eastward winds increase significantly in the northern high latitudes (60°N–90°N) and in the southern middle and high latitudes (50°S–70°S). Zonal winds begin to increase around Ls = 35° in the high latitudes of both hemispheres, corresponding to the end of the onset phase and the beginning of the expansion phase of the MY 35 E storm. The maximum increase in zonal wind speed can reach nearly 40 m/s in the northern high latitudes and nearly 30 m/s in the southern high latitudes. Additionally, westward winds in the mid-to-low latitudes of the Northern Hemisphere increase considerably, with the most significant enhancement reaching 20 m/s. Changes in zonal wind primarily reflect the thermal wind balance and are consistent with changes in the temperature field [32,43]. As shown in Figure 13c, we can see that the daily and zonal mean temperature increases between 50°S and 70°N after Ls = 35°. This leads to an increase in the meridional temperature gradient and thus increased zonal wind in the middle and high latitudes of both hemispheres. Since dust heating is primarily concentrated in the Northern Hemisphere during the MY 35 E storm, the temperature increase is greater there (Figure 13c). Thus, the phenomenon of enhanced eastward winds is more significant in the Northern Hemisphere than in the Southern Hemisphere (Figure 13b).

Figure 13.

The LMD-GCM simulated daily and zonal mean zonal wind (a) and temperature (c) at ~25 km (~50 Pa) during the MY 35 E storm (Ls = 33°–50°). Panel (b) shows the difference in daily and zonal mean zonal wind between MY 35 and the climatological year (defined in the Data and Methods section). In panel (a), positive values represent eastward winds, while negative values represent westward winds.

3.3.2. The Effect of MY 35 E Storm on Surface Horizontal Wind Speeds

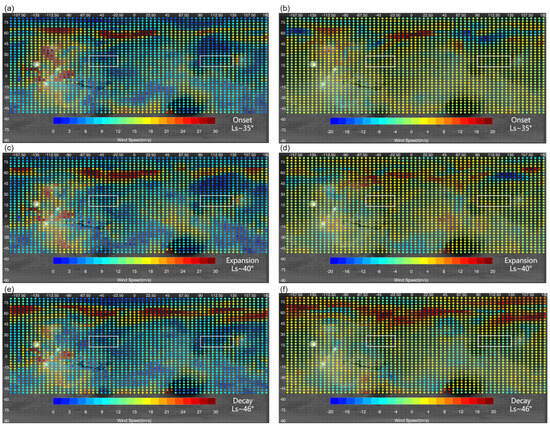

Dust storms can influence not only the wind field at high altitudes but also the wind field at the surface [43]. Changes in surface wind fields are critical to both the process of dust lifting and the safe operation of rovers and landers [8]. To evaluate the effect of the MY 35 E storm on surface winds, the global distribution of the daily maximum horizontal wind speed at 4 m simulated by the LMD GCM is investigated (Figure 14).

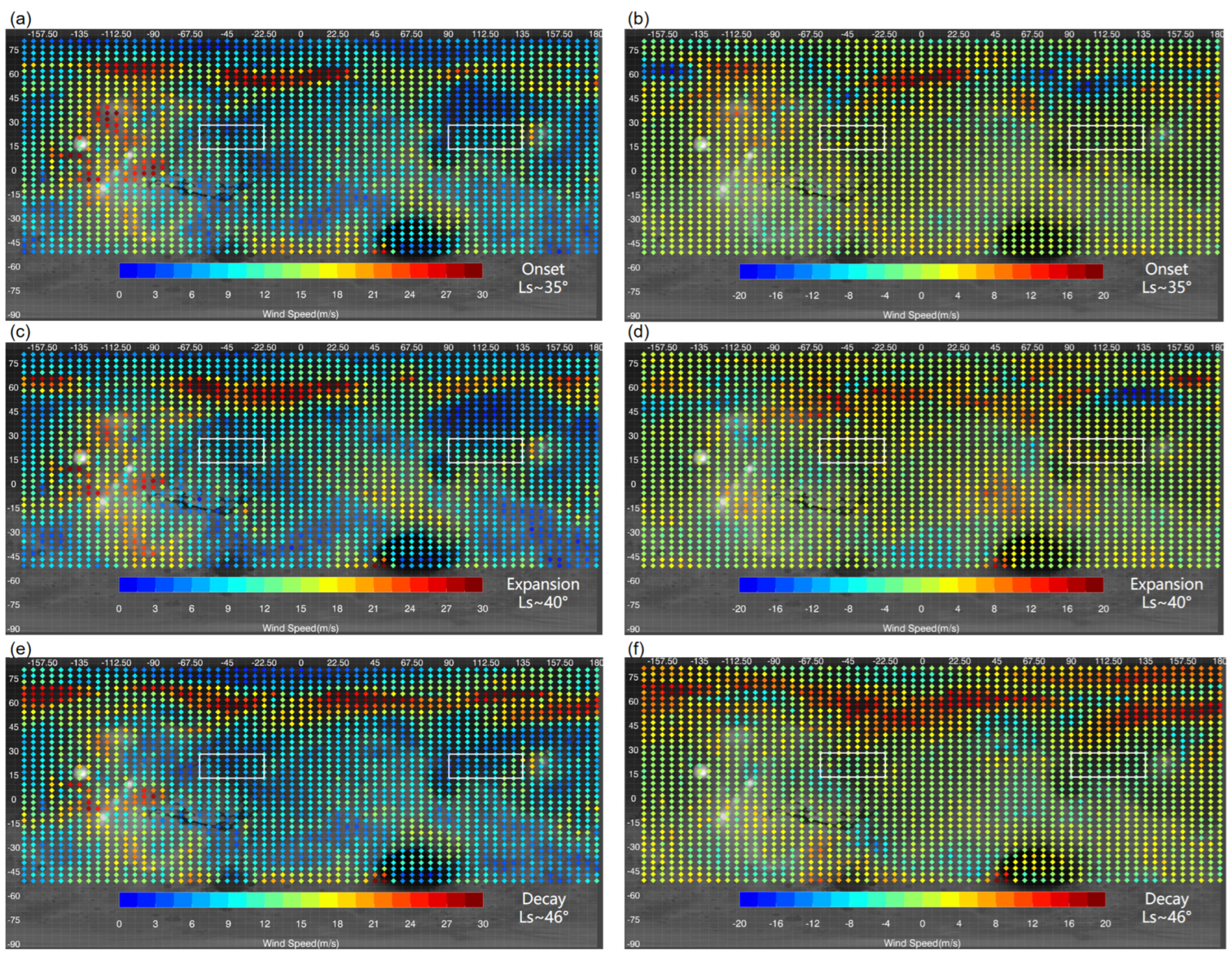

Figure 14.

The daily maximum horizontal wind speed at 4 m above the surface during the onset (top), expansion (middle), and decay (bottom) phase of the MY 35 E dust storm, as simulated by LMD-GCM; left column (panels (a,c,e)): the MY 35; right column (panels (b,d,f): difference between the MY 35 and the climatological year; Panels (a,b) show results for the onset phase (Ls = 35°), panels (c,d) for the expansion phase (Ls = 40°), and panels (e,f) for the decay phase (Ls = 46°); The wind speed (colored points) is overplotted on the global map (grayish shading) of Mars; The two white boxes in each panel indicate locations of the Chryse Plain (left) and Utopia Plains (right).

In general, larger horizontal wind speeds mainly occur within 50°–70°N and in regions with high topographic relief near the Tarsis Plateau within the 80°–135°W in the low latitudes during the entire storm phase, as shown in the left column of Figure 14. Note that in years without the E storm, high topographic relief in mountainous regions also results in strong surface winds, due to its effects on local atmospheric circulations [43]. The comparison of the left and right columns in Figure 14 indicates that the 50°–70°N area is where the surface wind primarily changes during the E storm. This is similar to the wind field changes at 25 km shown in Figure 13, which is associated with the enhancement of meridional temperature gradients in the atmosphere. In addition, changes in the near-surface atmosphere during dust storms may also be related to changes in surface thermophysical properties, topography, the polar ice cap, and weather systems [46]. Mars’s north polar ice cap usually retreats to nearly 65°N after Ls = 30° [42]. The enhanced temperature gradient near the polar ice cap contributes to strong zonal winds between 50° and 70°N in climatological years. As shown in Figure 15, the E dust storm mainly occurs between 60°N and 30°S. The 50°–70°N latitude region is located at the border of the polar ice cap and the E dust storm. The interior dust heating within the dust storm further increases the meridional temperature gradient, thus making the wind in these regions stronger during the E storm. During the storm’s decay phase, zonal wind speeds within the 45°–75°N latitudinal range continue to increase, exceeding those during the storm’s onset and expansion phases. This may be due to the fact that dust begins to settle from higher altitudes to lower altitudes during the decay phase. And the decrease in dust in the higher atmosphere allows more solar radiation to reach the surface, heating the air and increasing the meridional temperature gradient and associated zonal winds in the near-surface atmosphere.

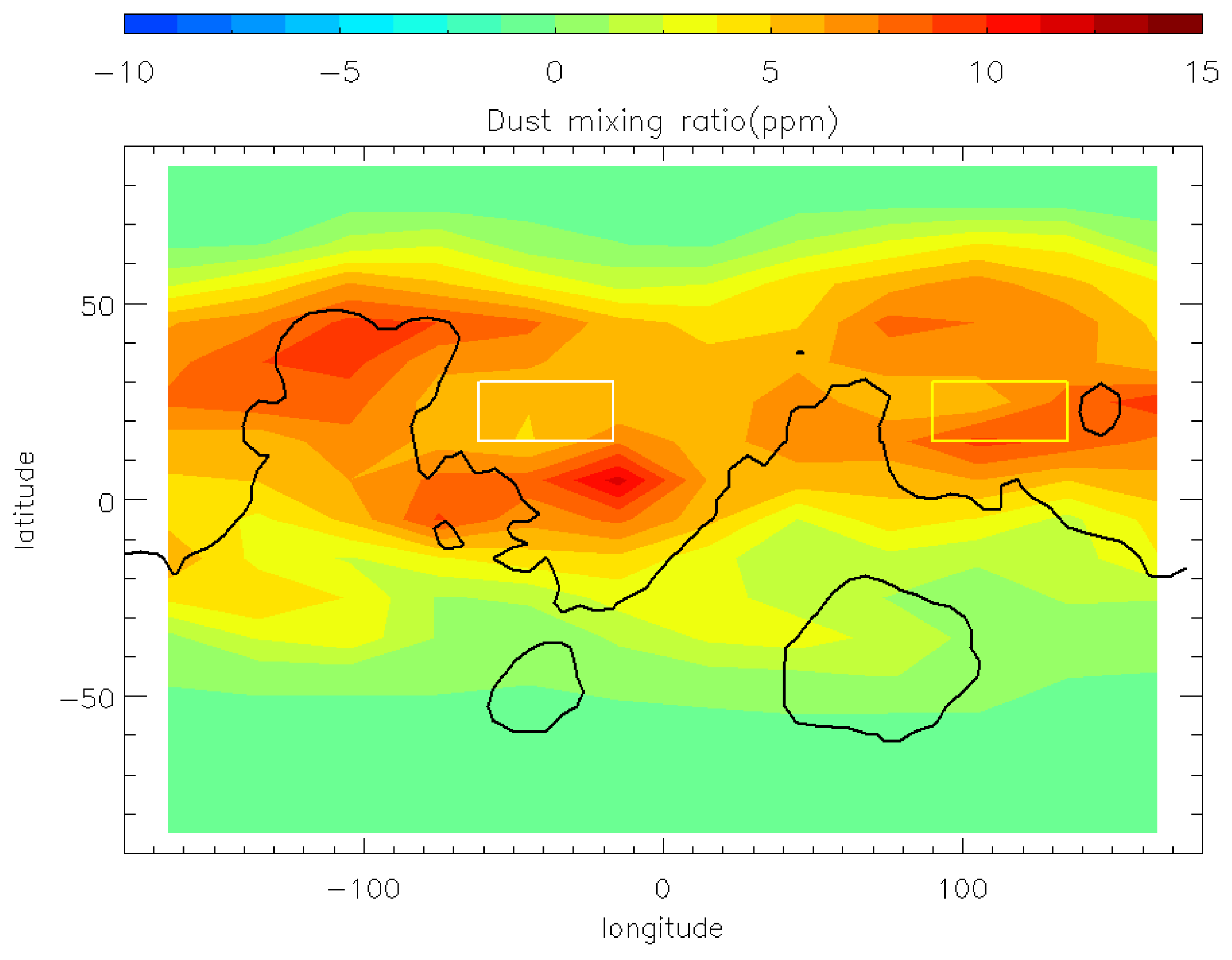

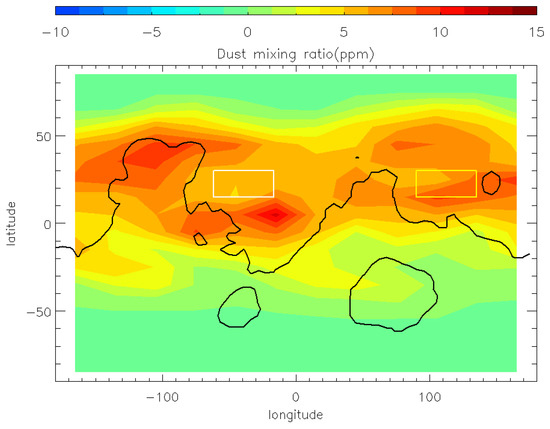

Figure 15.

The difference in dust mass mixing ratio at 50 Pa between MY 35 and the climatological years at local time 3 a.m. at the peak time of the E storm (Ls = 40°); The white box: Chryse plain area; The yellow box: Utopia plain area; The black curve: the contour of the terrain at 0 km.

Note that during the E storm, surface winds only change significantly in the middle and high latitudes, not in the low latitudes. Surface winds in the Chryse and Utopia plains, which are possible landing areas for Tianwen-3 [22], show less change, with variations of ±4 m/s or less. This is due to that, during the dust storm, the two plains are located primarily within the storm’s interior (Figure 15). There, the temperature contrast is smaller than at the storm’s edge, resulting in less enhancement in wind speed. The next section will examine changes in two plain wind fields in detail.

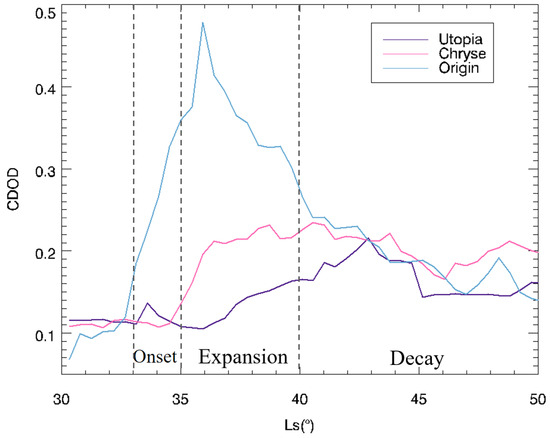

3.4. The Impact of MY 35 E Storm on Near-Surface Wind Fields in the Chryse and Utopia Plains

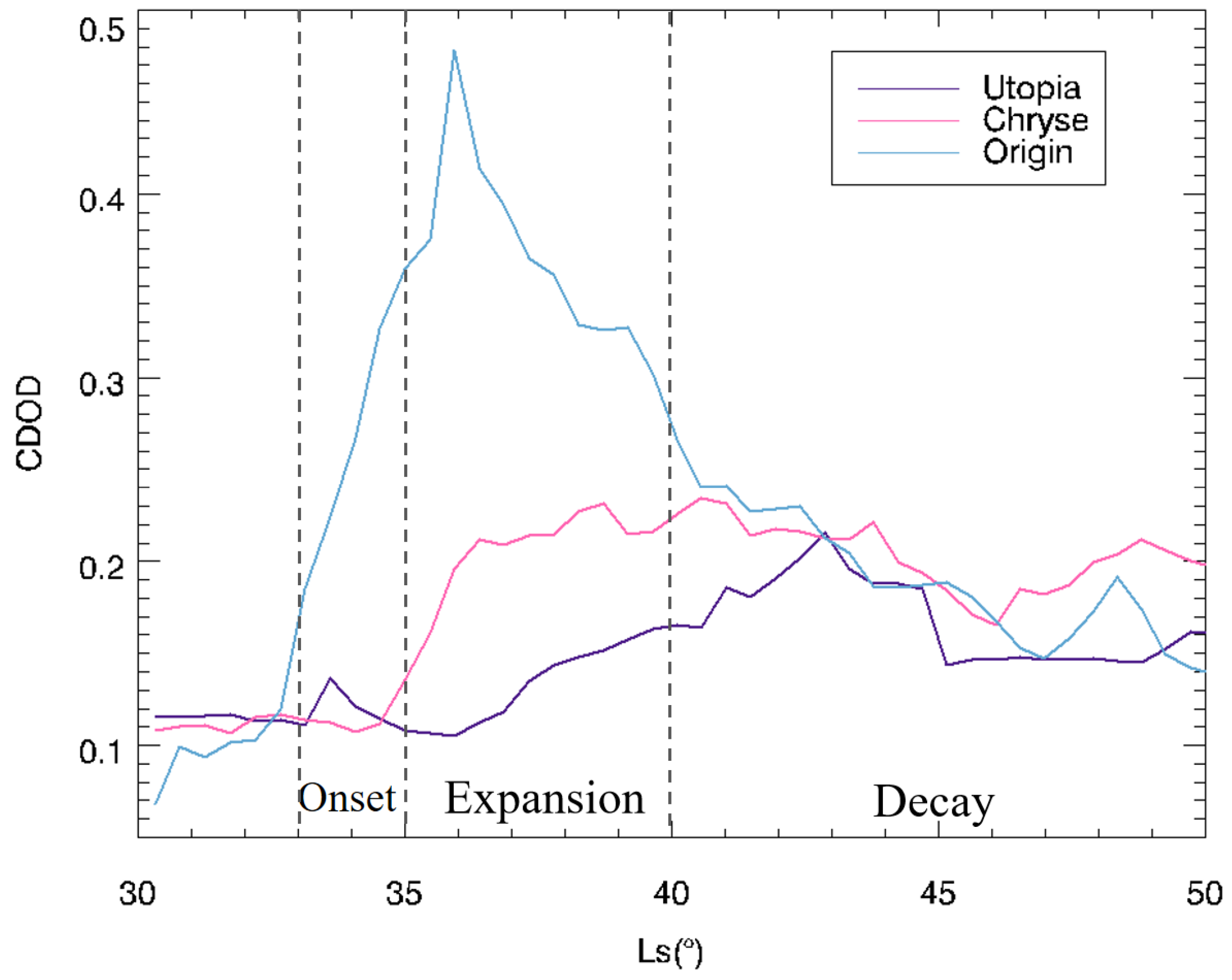

China’s Tianwen-3 mission plans to land on Mars and carry out its primary operations during the northern spring season [19]. The Chryse and Utopia plains are two potential landing areas [10,21,22]. If a large regional dust storm like the MY 35 E storm occurs during the mission, the severe dust conditions and high winds might significantly impact the mission safety [7,8,9,10,47]. Accordingly, the Tianwen-3 mission necessitates continuous monitoring and forecasting of dust activity within the landing zone throughout the mission period. To support this requirement, a preliminary analysis is first conducted to assess the arrival times of the anomalous spring dust storm observed in MY 35 at two key plains (Figure 16). Results indicate that the storm reached the Utopia and Chryse plains approximately 2–4 Ls after its initial onset, thereby offering a temporal buffer for dust storm forecasting.

Figure 16.

Column dust optical depth (CDOD) variations at three locations: the origin of the MY 35 anomalous spring dust storm, and the Utopia and Chryse plains. Dashed lines indicate the onset, expansion, and decay phases of the storm. The purple line corresponds to 111°E, 22.5°N (Utopia Plain); the pink line to 42°W, 22.5°N (Chryse Plain); and the blue line to 102°W, 40.5°N (storm origin).

As for the wind condition, Figure 13 shows that wind changes caused by the E dust storm are most significant during the storm peak time (near Ls = 40°). Therefore, this section focuses on wind field changes in Chryse and Utopia plains at Ls = 40° to study their possible impact on exploration missions.

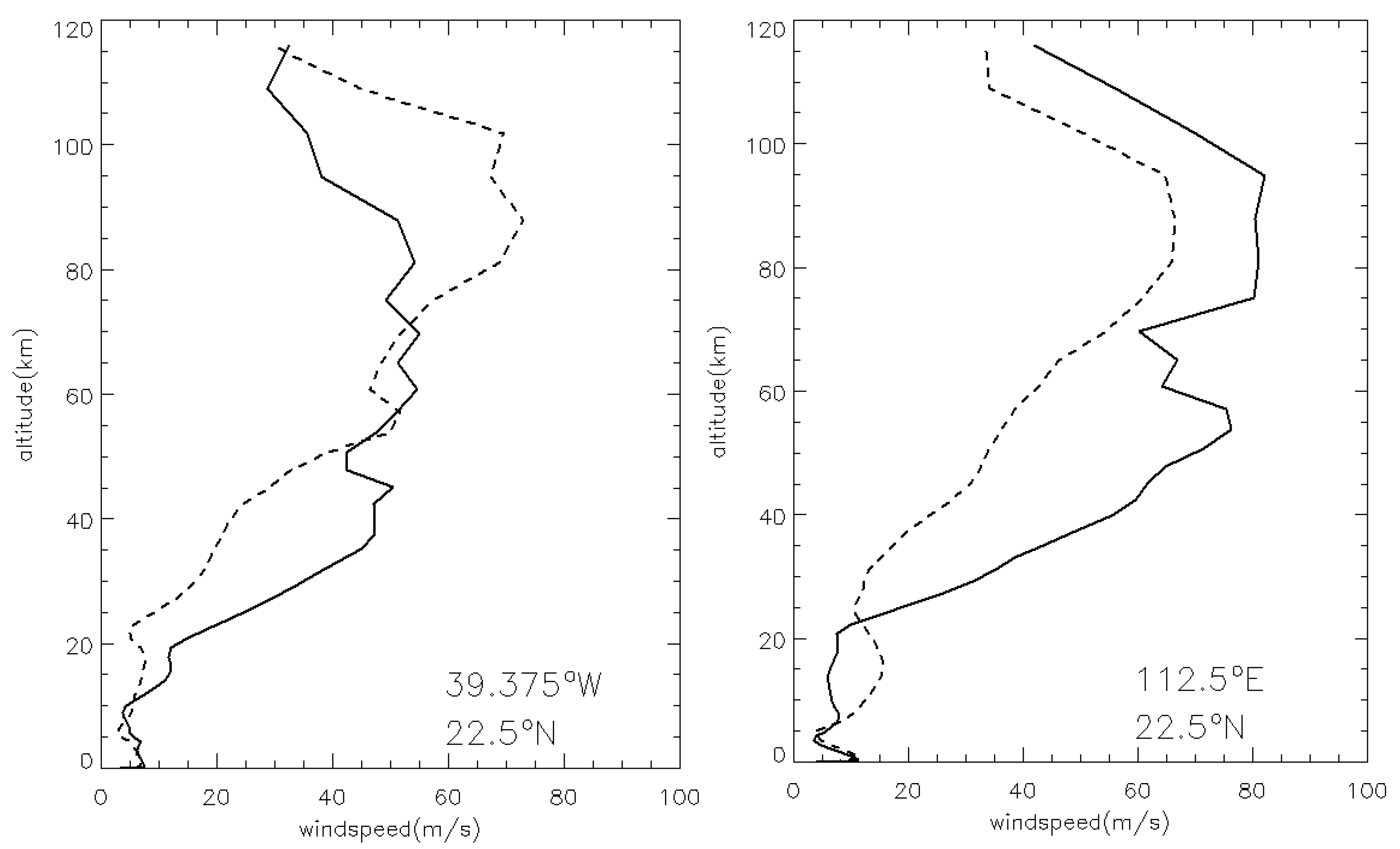

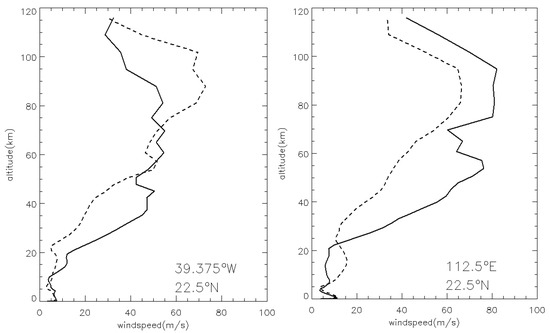

Variations in horizontal wind speed can affect the safety of the entry, descent, and landing (EDL) process for Mars rovers. Uncertainty in the wind field can affect the horizontal drift of the spacecraft, especially during the parachute phase, which may result in the landing site deviating from the target area [8]. Figure 17 shows the vertical profile of horizontal wind speed at two sites in the Chryse and Utopia plains during the peak time of the MY 35 E storm (Ls = 40°). The two sites are located at 39.375°W, 22.5°N in the Chryse Plain and 112.5°E, 22.5°N in the Utopia Plain, respectively. Both points lie near the central regions of the plains. The E dust storm remarkably affects the wind field above ~20 km, with the horizontal wind speed significantly enhanced between 20 and 60 km during the E storm. For example, at 112.5°E, 22.5°N in the Utopia Plain, the horizontal wind speed of MY 35 increases by about 40 m/s at 55 km compared to the climatological year. The change in horizontal wind speeds below 5 km is small during the E dust storm. This can be attributed to the relatively uniform dust distribution within the dust storm below 5 km, which results in minimal thermal gradients. Additionally, the attenuation of incoming solar radiation by the dense dust layer reduces the shortwave flux reaching the surface, thereby further suppressing the activity of the atmospheric boundary layer [48]. These factors contribute to the relatively weak wind fields within the interior of the dust storm at its peak intensity. However, in the upper atmosphere above the storm, more pronounced wind field variations may arise as a result of the dust storm’s influence on the excitation and propagation of atmospheric waves, as well as its modulation of large-scale meridional circulation [49,50,51].

Figure 17.

The LMD-GCM simulated vertical profile of daily mean horizontal wind speed at Ls = 40° in Chryse (left) and Utopia (right) Plains. Solid lines: the MY 35. Dashed lines: the climatological year.

However, situations above 60 km are more complicated. As shown in Figure 17, the wind decreases significantly at the Chryse site but increases at the Utopia site above 60 km. In fact, even in the absence of the E storm, the latitudinal band encompassing both plains displays significant zonal variations in wind velocity. Notably, peak wind speeds are observed at specific locations, and the two plains under investigation are situated near two such wind maxima. During the E storm, the spatial positions of these wind peaks remain largely unchanged; however, their magnitudes are altered. Specifically, the peak wind near Chryse is substantially weakened, whereas the peak near Utopia shows an enhancement, leading to the distinct results between the two plains above 60 km shown in Figure 17. These wind maxima appear to lack a clear correlation with surface topography. According to previous studies, such zonal anomalies in wind, temperature, or density within the middle and upper atmosphere are typically attributed to atmospheric wave activity, such as thermal tides and gravity waves [5]. However, the influence of dust storms on atmospheric waves is highly complex, involving changes in both the excitation sources and the propagation conditions. Given the diversity of wave types and the distinct mechanisms governing their generation and propagation, a comprehensive and systematic investigation is required—an endeavor beyond the scope of the present study and meriting future research.

A spacecraft’s speed during the entry phase usually ranges from hundreds to thousands of m/s and thus is tolerant to the expected uncertainties in wind speed at altitudes above 30 km [8]. In contrast, wind at lower altitudes (especially below 10–15 km) has a more significant impact on landing safety due to the increased air density and the decreased spacecraft’s speed. Additionally, strong surface winds may impact ground missions of landers or rovers. Therefore, also due to space limitations, this section focuses more on the wind fields in the atmospheric boundary layer, which corresponds to a depth of 5–10 km above the surface on Mars.

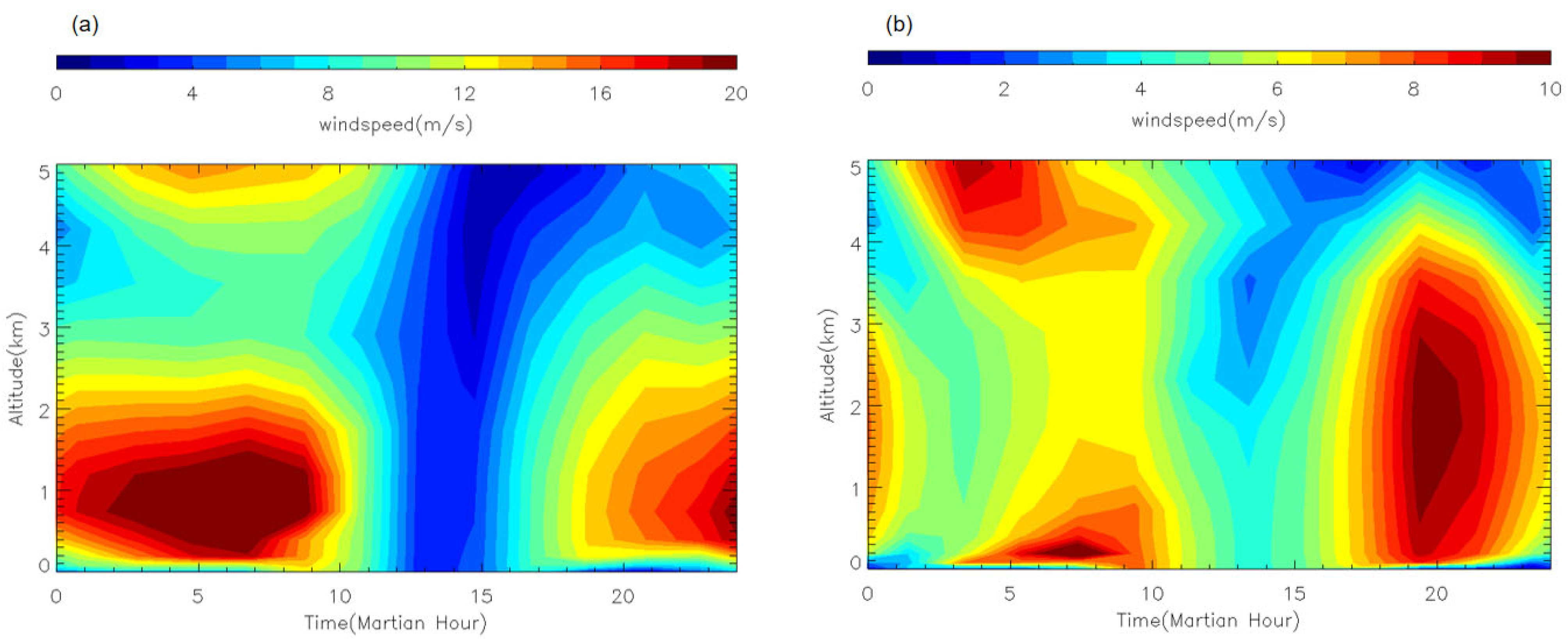

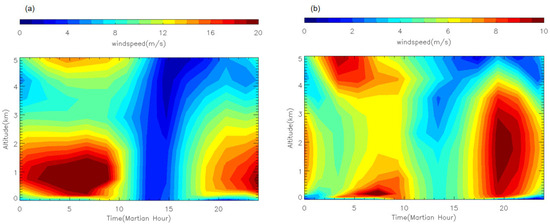

As shown in Figure 17, the change in daily mean horizontal wind speeds below 5 km is small during the E dust storm. This is consistent with Figure 14 and seems to suggest that the E dust storm has limited effects on changes in the near-surface wind field in the two plains. Although Figure 17 shows that the daily mean wind field does not change significantly, this does not reflect conditions at different local times. Previous studies have shown that, due to its thin atmosphere and low thermal inertia, Mars experiences extremely dramatic diurnal changes in its atmosphere. For instance, a diurnal pattern of horizontal wind variation dominates near the surface of Mars [43,52]. Therefore, we investigated diurnal variations in the horizontal wind speed within the atmospheric boundary layer at various locations in the Chryse and Utopia Plains. The results show that horizontal wind speeds are generally higher at night and lower during the day (see Figure 18 for example). These diurnal variations are primarily influenced by atmospheric tides and topography [53]. It has been found that large-scale dust storms can impact the amplitude and phase of atmospheric tides [54]. To study the impact of the MY 35 E storm on diurnal variations in horizontal wind speeds within the atmospheric boundary layer, we statistically analyzed the daily maximum horizontal wind speeds and their occurrence time in the simulated wind fields for the two plains (see Figure 19 and Figure 20).

Figure 18.

The LMD-GCM simulated diurnal variation in horizontal wind speed in the atmospheric boundary layer at Ls = 40° of MY 35 at (a) 101.25°E, 18.75°N, (b) 39.375°W, 18.75°N.

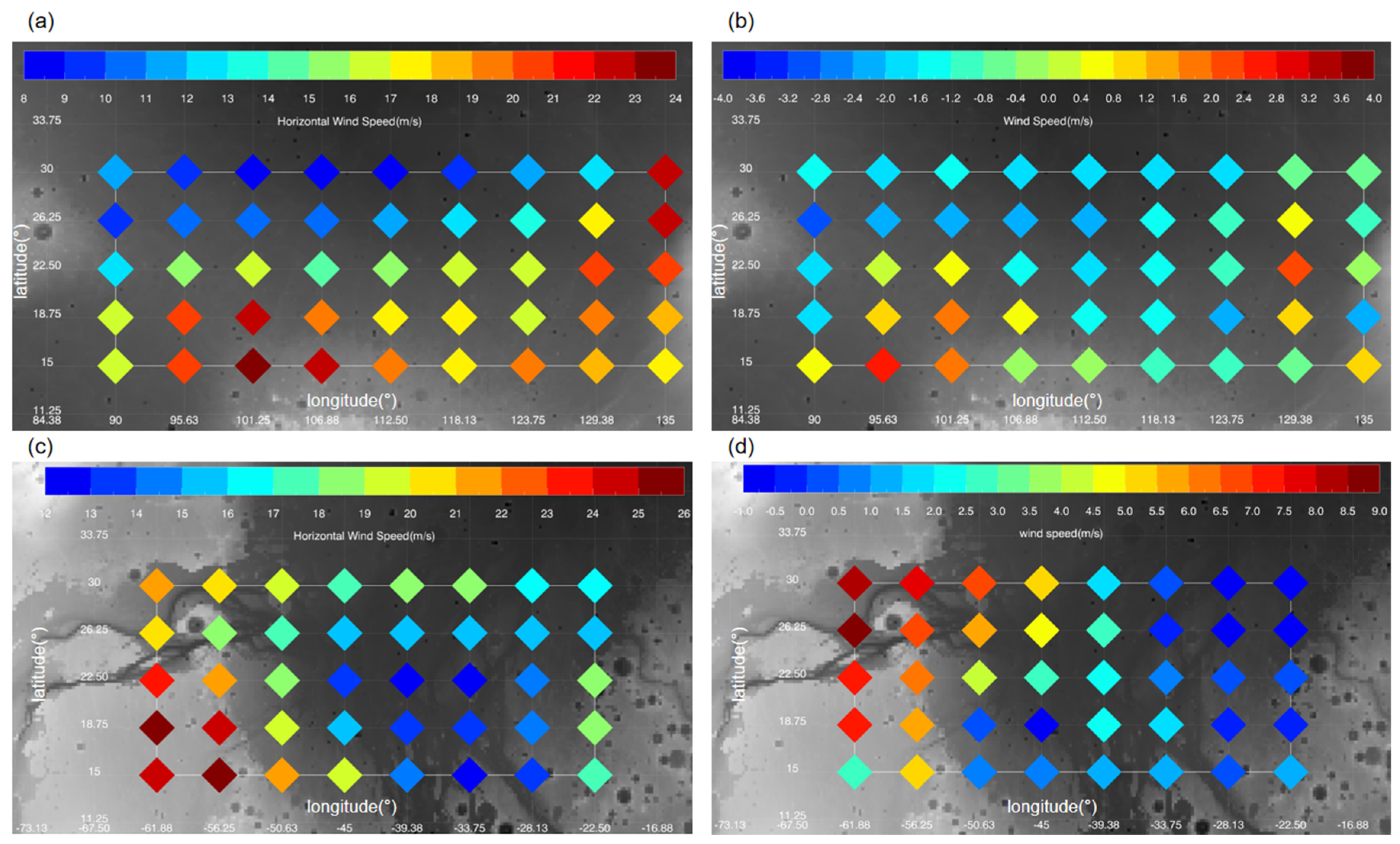

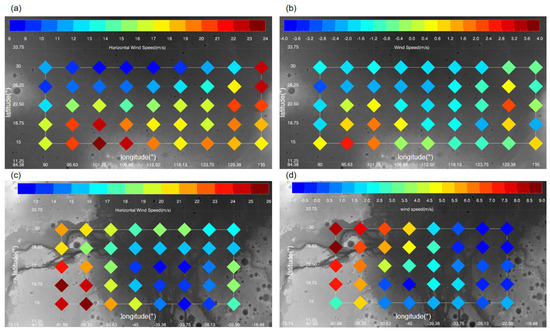

Figure 19.

The daily maximum horizontal wind speeds within the atmospheric boundary layer (below 5 km) at model grid points in the Utopia (panels (a,b)) and Chryse (panels (c,d)) Plains during the peak time of the E storm (Ls = 40°); left column (panels (a,c)): the MY 35; right column (panels (b,d)): difference between MY 35 and the climatological year.

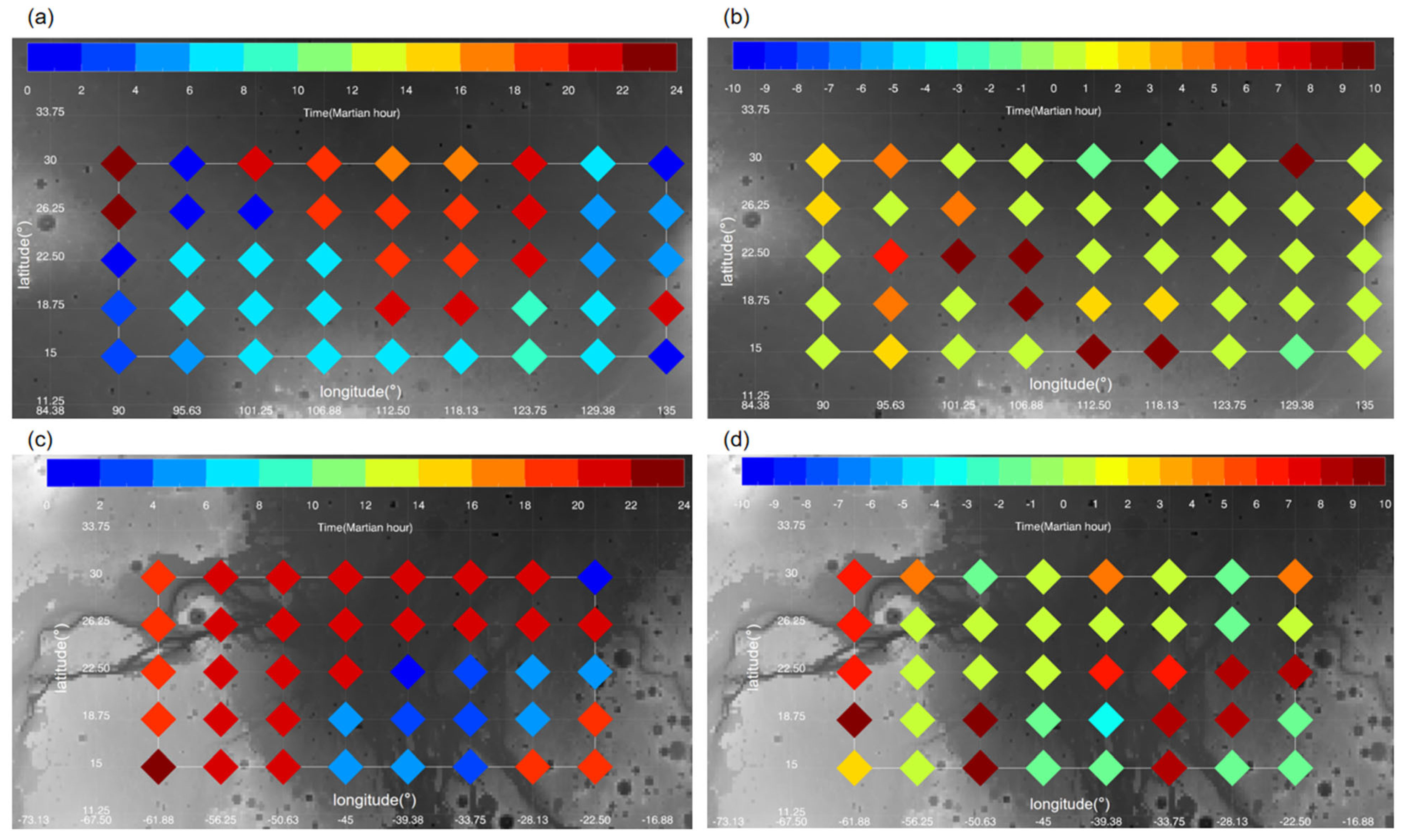

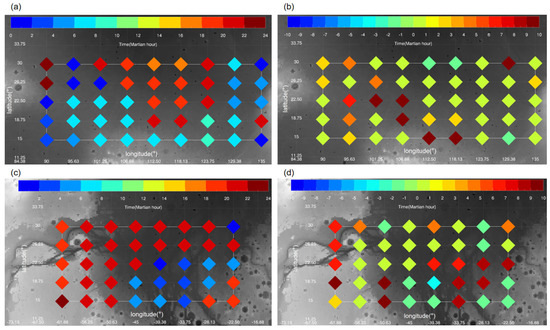

Figure 20.

The local time at which the maximum horizontal wind speed occurs within the atmospheric boundary layer (below 5 km) at model grid points in the Utopia (panels (a,b)) and Chryse (panels (c,d)) Plains during the peak time of the E storm (Ls = 40°); left column (panels (a,c)): the MY 35; right column (panels (b,d)): difference between MY 35 and the climatological year.

Figure 18 illustrates the daily maximum horizontal wind speeds within the atmospheric boundary layer at different locations in the Utopia and Chryse plains. Generally, during the peak time of the E storm, the daily maximum horizontal wind speed in the Utopia Plain varies from 8 to 24 m/s, with differences from the climatological year ranging from −4 to 4 m/s. In the Chryse plain, the daily maximum horizontal wind speed varies from 12 to 26 m/s, with differences from the climatological year ranging from −1 to 9 m/s. As has been discussed in Section 3.3, the two plains are located primarily within the E storm’s interior (Figure 15). Previous studies have suggested that large dust storms can block solar radiation from reaching the surface. This, in turn, leads to a weakening of thermal differences within the dust storm, resulting in a relative stable atmospheric condition [55]. This may explain that the overall wind speed in the two plains during the E storm peak time is not significant enhanced comparable to the climatological year, except for some locations with complicated topography. We can see that while the maximum daily horizontal wind speed at most locations in the Utopia Plain is comparable to the climatological year, the situation in the Chryse Plain is more complicated. The maximum wind during storm time is slightly lower than the climatological year in the eastern part of the Chryse Plain, but shows significant enhancement up to 9 m/s at some western locations with complicated topography (18.75°N–30°N, 62°W–50°W). Local topography strongly influences near-surface wind variations [43], so the variations in wind speed at different locations may be related to topographic induced local circulation, under different dust loading conditions. Previous studies have also suggested that large dust storms, such as A and C seasonal dust storms and global dust storms, can strengthen surface wind fields by enhancing large-scale, meridional circulation [53]. However, this situation did not occur during the E storm in the Utopia and Chryse Plains. This may be due to the differences in location and intensity of the atmospheric circulation enhanced by the E storm, as compared to that of traditional, large dust storms.

Figure 20 illustrates the local time when the wind speed reaches its maximum at different locations in the Utopia and Chryse Plains. The results indicate that the maximum horizontal wind speed primarily occurs from dusk to dawn in the two plains during the E storm peak time, with a greater focus on midnight in the Chryse Plain. The difference in local time between the MY 35 and the climatological year at most locations is minimal, suggesting that the MY 35 E storm does not significantly impact the timing of maximum horizontal wind speeds. In general, horizontal wind speeds within the boundary layer are relatively low between 10 a.m. and 4 p.m., making this potentially a good time for landing and takeoff operations.

4. Discussion

The MY 35 anomalous spring dust storm is unique in terms of its occurrence time during the aphelion season, when dust activity is thought to be weak, despite its shorter duration and lower peak dust mass mixing ratio. However, as a type of regional dust storm, it is comparable to other traditional types of large dust storms.

Table 1 summarizes the origin locations, propagation directions, latitudinal ranges, and evolution periods of the MY 35 E and C storms and the MY 36 Z storm, based on the results of Section 3.2. The origin locations of the MY 35 E and C storms are close to each other in longitude and are symmetrical in latitude with respect to the equator. In contrast, the origin location of the MY 36 Z storm differs significantly from the MY 35 E and C storms. MY 35 E and C storms propagate in the same zonal direction but in an antisymmetric direction meridionally relative to the equator. Unlike the E storm, the MY 36 Z storm mainly propagates eastward in the zonal direction and poleward from the equator in the meridional direction. The propagation direction of a dust storm is primarily influenced by the horizontal wind field [43]. For example, the onset phase of the MY 35 E storm is Ls = 33°–35°. At that time, the zonal wind at 50 Pa consists of an eastward wind in the northern middle latitudes and a weaker westward wind in the low latitudes. Consequently, the dust spreads eastward in the northern middle latitudes and westward in the low latitudes, and the spreading speed is faster in the middle latitudes than in the low latitudes. The onset phase of the C storm is Ls = 313°–316°. During this period, the wind is eastward in the southern middle latitudes and westward in the low latitudes, which is approximately north–south-symmetric with the wind field during the E storm. Similarly, the dust’s spreading in the meridional direction is mainly driven by the Martian meridional circulation [43]. During the E storm, the abnormal cross-equator circulation transports dust from the northern to the Southern Hemisphere [20]. During the C storm, which is near the southern summer, the meridional circulation transports dust from southern to Northern Hemisphere. Therefore, the E storm mainly spreads southward, whereas the C storm mainly spreads northward. During the MY 36 Z storm, the circulation shows north–south symmetry from the equator to the poles. Consequently, the dust spreads symmetrically in the meridional direction. The three dust storms have quite different latitudinal ranges, mainly due to the different seasons and positions of the subsolar point. The subsolar point is in the Northern Hemisphere during the MY 35 E storm and in the Southern Hemisphere during the C storm, and near the equator during the Z storm. Therefore, the E storm covers more in the Northern Hemisphere, the C storm covers more in the Southern Hemisphere, and the Z storm is concentrated near the equator. In terms of the storm evolution cycle, the three dust storms are almost identical. The E storm has the shortest evolution time and the lowest peak dust mass mixing ratio, probably due to the lower background dust levels and the weaker input of solar radiation during the aphelion season [4]. Overall, the E storm shares more similarities with the C storm than with the Z storm, implying that the E storm may also be associated with baroclinic waves, in a similar way that the C storm is [56].

Table 1.

The evolution characteristics of MY 35 E storm, C storm, and MY 36 Z storm.

At present, the precise triggers and underlying causes of this anomalous spring dust storm remain undetermined; however, several hypotheses have been proposed [18]. For example, MY 35 may have experienced unusually strong baroclinic activity in the Northern Hemisphere. Baroclinic activity is a key driver of seasonal dust storms [4,56]. Although localized dust storms are commonly observed in the Northern Hemisphere during this season in other years, they are typically confined to polar regions. The enhanced baroclinic activity in MY 35 may have contributed to the development of a larger-scale regional dust storm. Also, the MY 35 E storm may represent a residual effect of the MY 34 global dust storm. After the MY 34 global dust storm, an intense C storm occurred [26], potentially leading to an anomalously concentrated dust distribution, with substantial accumulation near the source region of the MY 35 anomalous spring dust storm. Subsequent strong surface winds may have mobilized this dust, giving rise to a regional dust storm. On the other hand, the particle size distribution of dust is also one of the key parameters influencing the dust lifting and development processes of dust storms. Previous studies suggested that the vertical profile of dust effective radius exhibits a smooth decrease with altitude, with particle sizes ranging from approximately 0.1 to 3.5 μm. Near the surface, dust particles tend to be larger, with typical radii between 1.4 and 1.8 μm below 10 km. The mean particle size decreases with height, reaching around 1 μm at ~20 km altitude and further declining to 0.3–0.7 μm above 40 km [1,57]. During dust storm events, however, larger particles near the surface can be lofted to higher altitudes [58]. The number density of dust particles below 10 km typically ranges from 1 to 3 cm−3 and decreases with increasing altitude. Nevertheless, dust storms can enhance vertical transport, resulting in elevated particle number densities at higher altitudes [59]. Despite these findings, the relationship between dust properties, such as particle size and number density, and dust storm dynamics remains poorly understood due to a lack of Martian observations. In the future, it would be worthwhile to investigate the relationships between dust particle characteristics and storm evolution with more observations and simulations, thereby providing further insight into the mechanisms underlying the anomalous dust storm formation.

As for the influence of the E storm on the wind field, this work briefly examines diurnal variations in the wind field during the MY 35 anomalous spring dust storm. To understand the full impact of the spring dust storm on the atmosphere, a more in-depth study of atmospheric tidal activity and its influence on wind fields during the E dust storm is necessary. Note that the wind field simulation results in this study are limited by the model’s resolution and are expected to differ from the actual situation. Specifically, wind fields—especially near-surface wind fields—simulated using low-resolution grids are typically smaller than those simulated using high-resolution grids. On the one hand, this is somewhat like smoothing the data with a coarse grid; on the other hand, a coarser model grid cannot capture the forcing of subgrid terrain on the atmosphere. Therefore, the simulated wind field results presented in this paper should be considered the lower limit of wind speeds generated during dust storms. It cannot reflect the strong, instantaneous gusts that may occur during dust storms. Additionally, due to space limitations, this paper focuses more on the impact of the E storm on near-surface wind fields in the two plains. Although the middle and upper atmosphere have relatively low densities, significant changes in wind speed can also affect the ascent or descent processes of a spacecraft. Due to the complexity of these changes, they are not discussed in detail in this paper. Overall, this work only provides a preliminary exploration of the impact of the E dust storm on wind fields. The factors mentioned above that are not considered in this paper will require more targeted and detailed simulations and research in the future to better support future Mars missions.

5. Conclusions

This paper investigates the evolution of the MY 35 anomalous spring dust storm and its impact on the atmosphere using observational data from MCS and simulation results from LMD-GCM.

We divide the evolution process of the MY 35 anomalous spring dust storm into four phases: pre-storm, onset, expansion, and decay phases. During the pre-storm phase (Ls = 25°–32°), the global dust mass mixing ratio remains low, with only small-scale dust activities observed. After entering the onset phase (Ls = 33°–35°), the dust mass mixing ratio increases significantly, exceeding 8 ppm. Dust spreads from the origin area in an east–west direction, and an obvious vertical uplift phenomenon occurs, exceeding 50 Pa (about 25 km). In the expansion phase (Ls = 36°–40°), the E dust storm rapidly expands, reaching its maximum latitudinal coverage of 30°S–60°N. The decay phase (Ls = 41°–50°) is characterized by the dust gradually settling and the dust mass mixing ratio decreasing, eventually returning to a calm state similar to that before the dust storm. The MY 35 anomalous spring dust storm originates in the northern low and middle latitudes near 100°W. Then, the source of dust lifting gradually expands to a latitudinal range of 0°–70°N and longitudinal range of 120°E–120°W. The MY 35 anomalous spring dust storm has a shorter duration and lower peak dust mass mixing ratio and temperature compared to the A, B, C, and Z storms. This may be due to weak insolation conditions and low background airborne dust levels during the aphelion season. The evolution of the MY 35 anomalous spring dust storm is similar to that of the MY 35 C storm, showing mirror symmetry relative to the equator, suggesting that the two storms may have similar evolutionary patterns.

During the MY 35 anomalous spring dust storm, significant eastward wind enhancement occurs at 50 Pa in the northern high latitudes (60°N–90°N) and the southern mid-to-high latitudes (50°S–70°S), while westward wind enhancement occurs in the low-to-mid latitudes. The change in the wind field is related to the change in atmospheric temperature structure caused by the dust storm. Additionally, the analysis of the daily maximum horizontal wind speed at 4 m above the surface reveals strong surface winds in the 50°–70°N latitude range. This region is the southern edge of the northern polar ice cap and the northern edge of the E dust storm. The interior dust heating within the dust storm further increases the meridional temperature gradient between the middle latitudes and the northern polar ice cap, thus making the wind in these regions stronger during the E storm. In contrast, horizontal wind speeds in the Chryse and Utopia Plains, which are located inside the dust storm, show fewer changes during the E dust storm peak time.

To evaluate the possible impacts of the anomalous spring dust storm on future Mars exploration missions, we focus on the variation in the wind field in the Chryse and Utopia Plains, two potential landing areas of China’s Tianwen-3 Mars sample-return mission. The vertical profiles of the LMD-GCM simulated horizontal wind in the two plains show that, during the E storm peak time, the change in daily mean wind speed is significant above 20 km, but relatively small in the atmospheric boundary layer below 5 km. In the 20–50 km altitude range, wind speeds increase significantly by up to 40 m/s in the Utopia Plain during the spring dust storm compared to the climatological year, which may impact the landing and takeoff process of the spacecraft. Horizontal wind speeds within the boundary layer are very low compared to horizontal wind speeds at high altitudes. However, their variations and response to dust storms are more important due to the increased density of the lower atmosphere and the slower speed of spacecraft. Simulation results indicate that horizontal winds within the boundary layer of the Chryse and Utopia Plains exhibit significant diurnal variation, with the daily maximum wind speed (up to 26 m/s) typically occurring from dusk to dawn. In contrast, horizontal wind speeds are relatively low during the midday hours (10:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m.), making this period potentially a good time for landing and takeoff operations. This pattern remains almost unchanged during the anomalous spring dust storms of MY 35.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.W.; methodology and investigation, H.H. and Z.W.; software, H.H.; validation, J.G., Y.W. (Yuqi Wang) and X.C.; writing—original draft preparation, H.H. and Z.W.; writing—review and editing, Z.R., F.H. and Y.W. (Yong Wei). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China through grants 42375119; Key Technology Research Project of TW-3 (TW3006); the Key Research Program of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Grant ZDBS-SSW-TLC00103 (Z. J. Rong); and the Key Research Program of the Institute of Geology and Geophysics, CAS, Grant IGGCAS-202102 (Z. J. Rong).

Data Availability Statement

The MCS data used in this study are available for download from NASA Planetary Data System: The Planetary Atmospheres Node at https://pds-atmospheres.nmsu.edu/data_and_services/atmospheres_data/MARS/atmosphere_temp_prof.html (accessed on 27 January 2025). The CDOD data used in this study are available for download from the Mars Climate Database at https://www-mars.lmd.jussieu.fr/mars/dust_climatology/index.html (accessed on 1 February 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MY | Martian year |

| MCS | Mars Climate Sounder |

| MRO | Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter |

| LMD-GCM | Laboratoire de Météorologie Dynamique Martian Global Climate Model |

| MCD | Mars Climate Database |

| CDOD | Column dust optical depth |

| Ls | solar longitude |

References

- Kahre, M.A.; Murphy, J.R.; Newman, C.E.; Wilson, R.J.; Cantor, B.A.; Lemmon, M.T.; Wolff, M.J. The Mars Dust Cycle. In The Atmosphere and Climate of Mars; Haberle, R.M., Clancy, R.T., Forget, F., Smith, M.D., Zurek, R.W., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2017; pp. 295–337. ISBN 978-1-139-06017-2. [Google Scholar]

- Montabone, L.; Spiga, A.; Kass, D.M.; Kleinböhl, A.; Forget, F.; Millour, E. Martian Year 34 Column Dust Climatology from Mars Climate Sounder Observations: Reconstructed Maps and Model Simulations. JGR Planets 2020, 125, e2019JE006111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.D.; Pearl, J.C.; Conrath, B.J.; Christensen, P.R. Thermal Emission Spectrometer Results: Mars Atmospheric Thermal Structure and Aerosol Distribution. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 2001, 106, 23929–23945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kass, D.M.; Kleinböhl, A.; McCleese, D.J.; Schofield, J.T.; Smith, M.D. Interannual Similarity in the Martian Atmosphere During the Dust Storm Season. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2016, 43, 6111–6118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Li, T.; Heavens, N.G.; Newman, C.E.; Richardson, M.I.; Yang, C.; Li, J.; Cui, J. Earth-Like Thermal and Dynamical Coupling Processes in the Martian Climate System. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2022, 229, 104023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Richardson, M.I. The Origin, Evolution, and Trajectory of Large Dust Storms on Mars During Mars Years 24–30 (1999–2011). Icarus 2015, 251, 112–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzewich, S.D.; Lemmon, M.; Smith, C.L.; Martínez, G.; De Vicente-Retortillo, Á.; Newman, C.E.; Baker, M.; Campbell, C.; Cooper, B.; Gómez-Elvira, J.; et al. Mars Science Laboratory Observations of the 2018/Mars Year 34 Global Dust Storm. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2019, 46, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasavada, A.R.; Chen, A.; Barnes, J.R.; Burkhart, P.D.; Cantor, B.A.; Dwyer-Cianciolo, A.M.; Fergason, R.L.; Hinson, D.P.; Justh, H.L.; Kass, D.M.; et al. Assessment of Environments for Mars Science Laboratory Entry, Descent, and Surface Operations. Space Sci. Rev. 2012, 170, 793–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Saidel, M.; Richardson, M.I.; Toigo, A.D.; Battalio, J.M. Martian Dust Storm Distribution and Annual Cycle from Mars Daily Global Map Observations. Icarus 2023, 394, 115416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Li, B.; Rong, Z.; Qu, S.; Chen, S. Martian Dust Storm Spatial-Temporal Analysis of Tentative Landing Areas for China’s Tianwen-3 Mars Mission. Earth Space Sci. 2024, 11, e2024EA003634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battalio, M.; Wang, H. The Mars Dust Activity Database (MDAD): A Comprehensive Statistical Study of Dust Storm Sequences. Icarus 2021, 354, 114059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Rubio, C.; Vicente-Retortillo, A.; Martínez-Esteve, G.; Gómez, F.; Rodríguez-Manfredi, J.A. Global Characterization of the Early-Season Dust Storm of Mars Year 36. Icarus 2025, 426, 116369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillespie, H.E.; Greybush, S.J.; Wilson, R.J. An Investigation of the Encirclement of Mars by Dust in the 2018 Global Dust Storm Using EMARS. JGR Planets 2020, 125, e2019JE006106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzewich, S.D.; Fedorova, A.A.; Kahre, M.A.; Toigo, A.D. Studies of the 2018/Mars Year 34 Planet-Encircling Dust Storm. JGR Planets 2020, 125, e2020JE006700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heavens, N.G.; Kass, D.M.; Shirley, J.H.; Piqueux, S.; Cantor, B.A. An Observational Overview of Dusty Deep Convection in Martian Dust Storms. J. Atmospheric Sci. 2019, 76, 3299–3326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zurita-Zurita, S.; De La Torre Juárez, M.; Newman, C.E.; Viúdez-Moreiras, D.; Kahanpää, H.T.; Harri, A.-M.; Lemmon, M.T.; Pla-García, J.; Rodríguez-Manfredi, J.A. Mars Surface Pressure Oscillations as Precursors of Large Dust Storms Reaching Gale. JGR Planets 2022, 127, e2021JE007005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Wu, Z.; Rong, Z.; He, F.; Li, B.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.; Gao, J.; Fan, K.; Wei, Y. A Statistical Study of the Interannual Variability of the Dusty Season on Mars Based on Column Dust Optical Depth. Quat. Sci. 2025, 45, 882–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kass, D.M.; Kleinböhl, A.; Shirley, J.; Cantor, B.A.; Heavens, N.G. Observations of the Mars Year 35 E (Early) Large-Scale Regional Dust Event. 2022. Available online: https://www-mars.lmd.jussieu.fr/paris2022/abstracts/oral_Kass_David.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Hou, Z.; Liu, J.; Pang, F.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Xu, M.; Gong, J.; Jiang, K.; Kang, Z.; Lin, Y.; et al. In Search of Signs of Life on Mars with China’s Sample Return Mission Tianwen-3. Nat. Astron. 2025, 9, 783–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Yang, C.; Li, T.; Lai, D.; Fang, X. The Atmospheric Response to an Unusual Early-Year Martian Dust Storm. JGR Planets 2025, 130, e2024JE008694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Qu, S.; Ling, Z.; Chen, S. A Preliminary Study on the Identification and Spatio-Temporal Characteristics of Martian Atmospheric Eddies. JGR Planets 2024, 129, e2023JE007937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, P.; Tian, Y.; Li, B.; Qu, S. Establishment of Safety Evaluation Factors for Dust Storms in the Landing Area Selection for Tianwen-3 Mission. Earth Space Sci. 2025, 12, e2024EA003994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Li, Z.; Yu, T.; Xia, C. Temporal and Spatial Prediction of Column Dust Optical Depth Trend on Mars Based on Deep Learning. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCleese, D.J.; Schofield, J.T.; Taylor, F.W.; Calcutt, S.B.; Foote, M.C.; Kass, D.M.; Leovy, C.B.; Paige, D.A.; Read, P.L.; Zurek, R.W. Mars Climate Sounder: An Investigation of Thermal and Water Vapor Structure, Dust and Condensate Distributions in the Atmosphere, and Energy Balance of the Polar Regions. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 2007, 112, 2006JE002790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Rubio, C.; Vicente-Retortillo, A.; Gómez, F.; Rodríguez-Manfredi, J.A. Interannual Variability of Regional Dust Storms Between Mars Years 24 and 36. Icarus 2024, 412, 115982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kass, D.M.; Schofield, J.T.; Kleinböhl, A.; McCleese, D.J.; Heavens, N.G.; Shirley, J.H.; Steele, L.J. Mars Climate Sounder Observation of Mars’ 2018 Global Dust Storm. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2020, 47, e2019GL083931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Li, T.; Dou, X. What Causes Seasonal Variation of Migrating Diurnal Tide Observed by the Mars Climate Sounder? JGR Planets 2017, 122, 1227–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heavens, N.G.; Richardson, M.I.; Kleinböhl, A.; Kass, D.M.; McCleese, D.J.; Abdou, W.; Benson, J.L.; Schofield, J.T.; Shirley, J.H.; Wolkenberg, P.M. The Vertical Distribution of Dust in the Martian Atmosphere During Northern Spring and Summer: Observations by the Mars Climate Sounder and Analysis of Zonal Average Vertical Dust Profiles. J. Geophys. Res. 2011, 116, E04003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forget, F.; Hourdin, F.; Fournier, R.; Hourdin, C.; Talagrand, O.; Collins, M.; Lewis, S.R.; Read, P.L.; Huot, J. Improved General Circulation Models of the Martian Atmosphere from the Surface to Above 80 km. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 1999, 104, 24155–24175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montabone, L.; Forget, F.; Millour, E.; Wilson, R.J.; Lewis, S.R.; Cantor, B.; Kass, D.; Kleinböhl, A.; Lemmon, M.T.; Smith, M.D.; et al. Eight-Year Climatology of Dust Optical Depth on Mars. Icarus 2015, 251, 65–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madeleine, J.-B.; Forget, F.; Millour, E.; Montabone, L.; Wolff, M.J. Revisiting the Radiative Impact of Dust on Mars Using the LMD Global Climate Model. J. Geophys. Res. 2011, 116, E11010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Said, A. Quantifying the Atmospheric Impact of Local Dust Storms Using a Martian Global Circulation Model. Icarus 2020, 336, 113470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Forget, F.; Bertrand, T.; Spiga, A.; Millour, E.; Navarro, T. Parameterization of Rocket Dust Storms on Mars in the LMD Martian GCM: Modeling Details and Validation. JGR Planets 2018, 123, 982–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millour, E.; Forget, F.; Spiga, A.; Pierron, T.; Bierjon, A.; Montabone, L.; Vals, M.; Lefèvre, F.; Chaufray, J.-Y.; Lopez-Valverde, M.; et al. The Mars Climate Database. In Proceedings of the Europlanet Science Congress 2022, Granada, Spain, 18–23 September 2022; p. EPSC2022-786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almatroushi, H.; AlMazmi, H.; AlMheiri, N.; AlShamsi, M.; AlTunaiji, E.; Badri, K.; Lillis, R.J.; Lootah, F.; Yousuf, M.; Amiri, S.; et al. Emirates Mars Mission Characterization of Mars Atmosphere Dynamics and Processes. Space Sci. Rev. 2021, 217, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Li, T.; Cui, J.; Yang, C.; Rong, Z.; He, F.; Li, J.; Cheng, X.; Wei, Y. Global Seasonal Variations of Martian Atmospheric Pressure and Density from Mars Climate Sounder. JGR Space Phys. 2025, 130, e2025JA034148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolkenberg, P.; Giuranna, M.; Smith, M.D.; Grassi, D.; Amoroso, M. Similarities and Differences of Global Dust Storms in MY 25, 28, and 34. JGR Planets 2020, 125, e2019JE006104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCleese, D.J.; Heavens, N.G.; Schofield, J.T.; Abdou, W.A.; Bandfield, J.L.; Calcutt, S.B.; Irwin, P.G.J.; Kass, D.M.; Kleinböhl, A.; Lewis, S.R.; et al. Structure and Dynamics of the Martian Lower and Middle Atmosphere as Observed by the Mars Climate Sounder: Seasonal Variations in Zonal Mean Temperature, Dust, and Water Ice Aerosols. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 2010, 115, 2010JE003677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantor, B.A. MOC Observations of the 2001 Mars Planet-Encircling Dust Storm. Icarus 2007, 186, 60–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciazela, M.; Ciazela, J.; Pieterek, B. High Resolution Apparent Thermal Inertia Mapping on Mars. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 3692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]