Random Cross-Validation Produces Biased Assessment of Machine Learning Performance in Regional Landslide Susceptibility Prediction

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Datasets

2.3. Methods

2.3.1. Cross-Validation Approaches

2.3.2. Machine Learning Algorithms

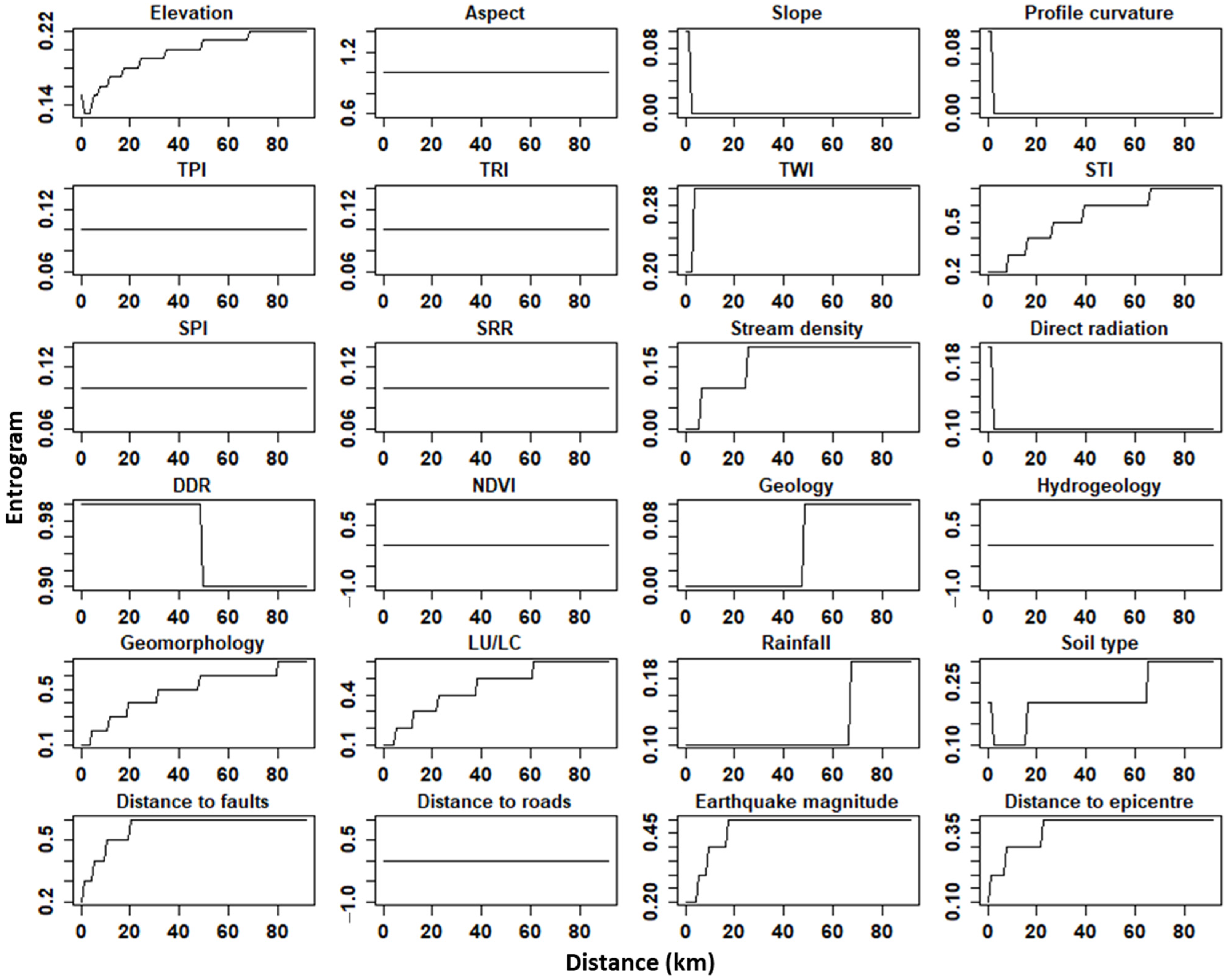

2.3.3. Computation of SAC

2.3.4. Performance Metrics

2.3.5. Learning Curve Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Hyperparameter Tuning

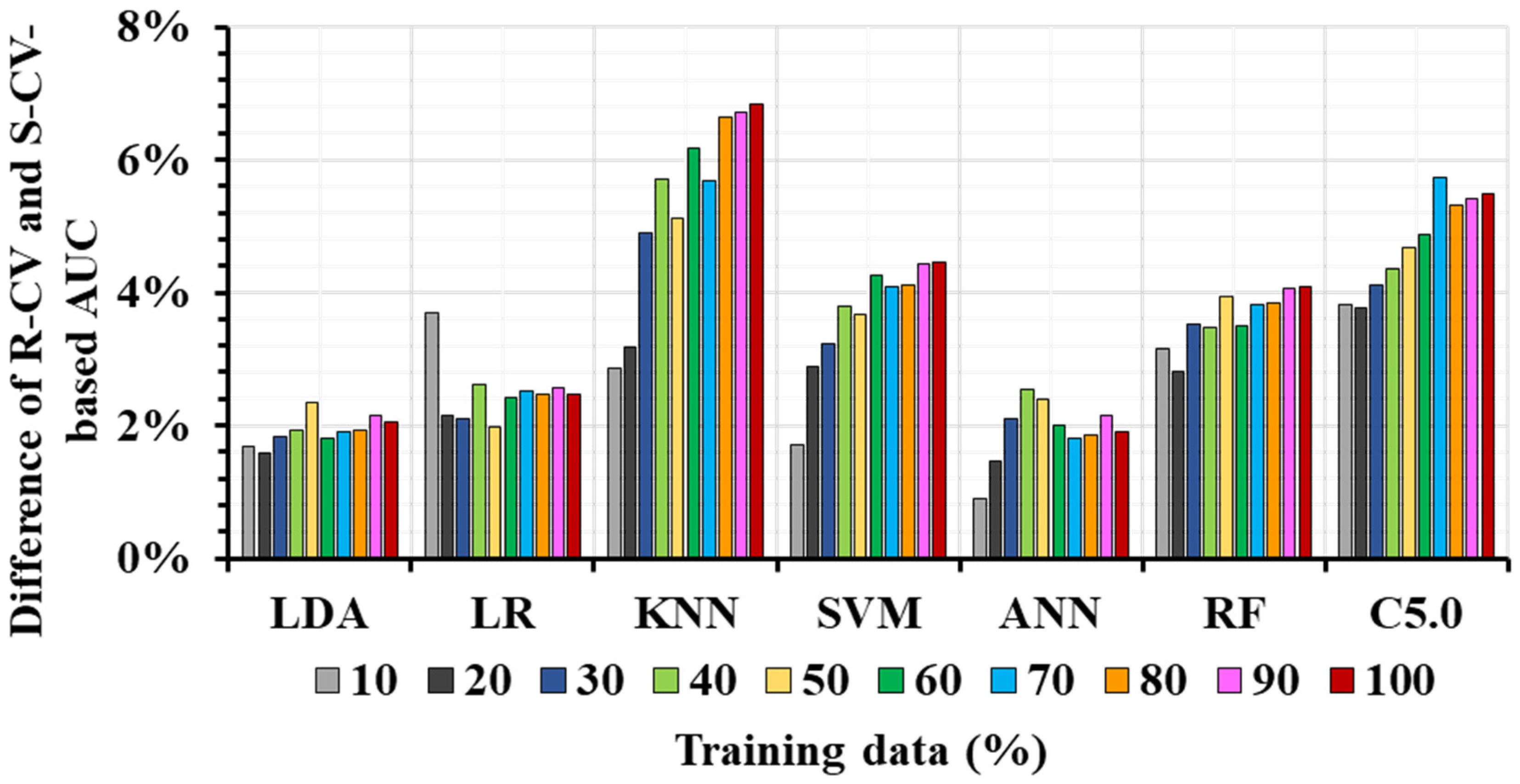

3.2. ML Performance Assessment

3.3. Learning Curve Analysis

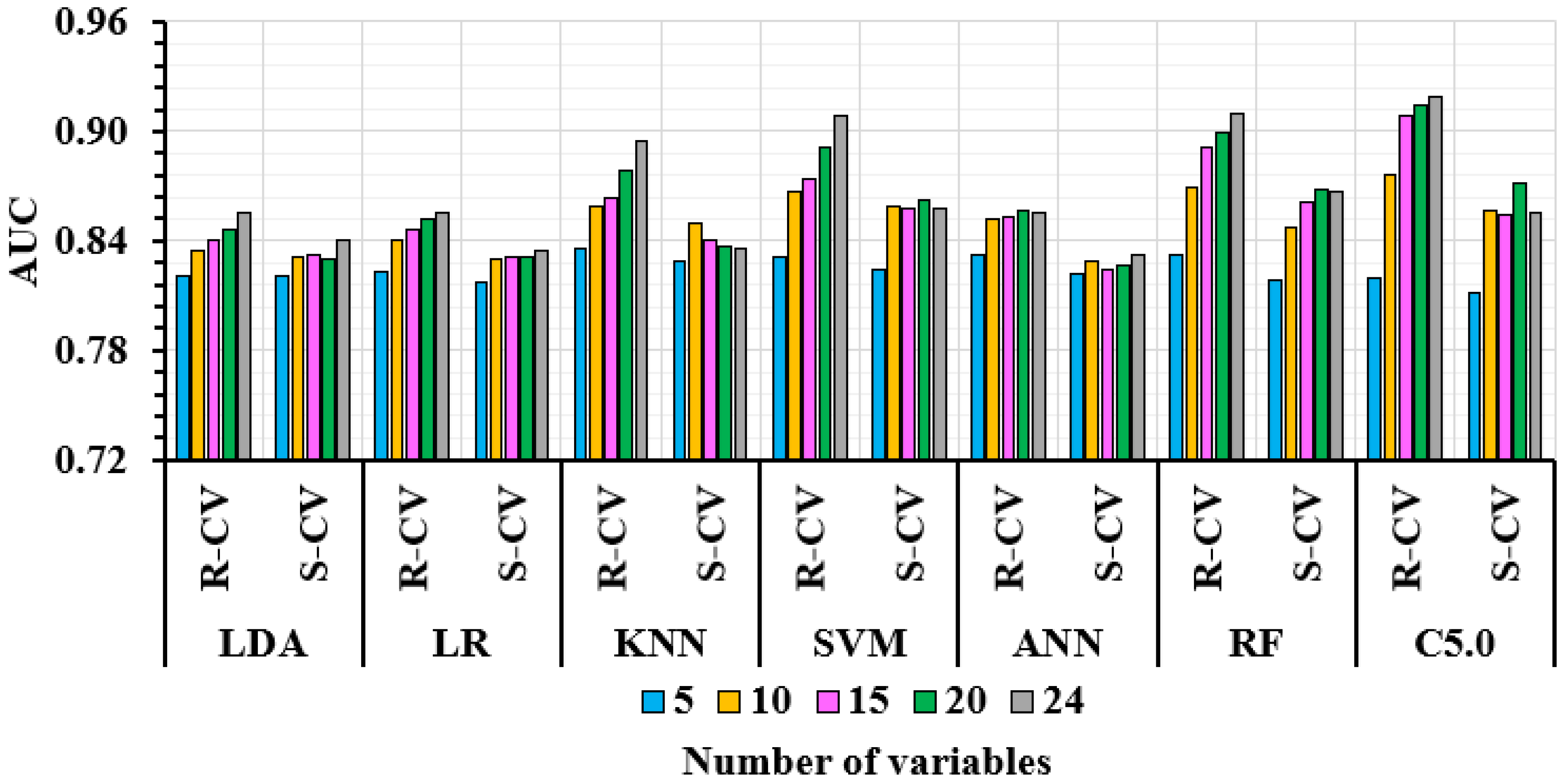

3.3.1. Number of Variables and ML Performance

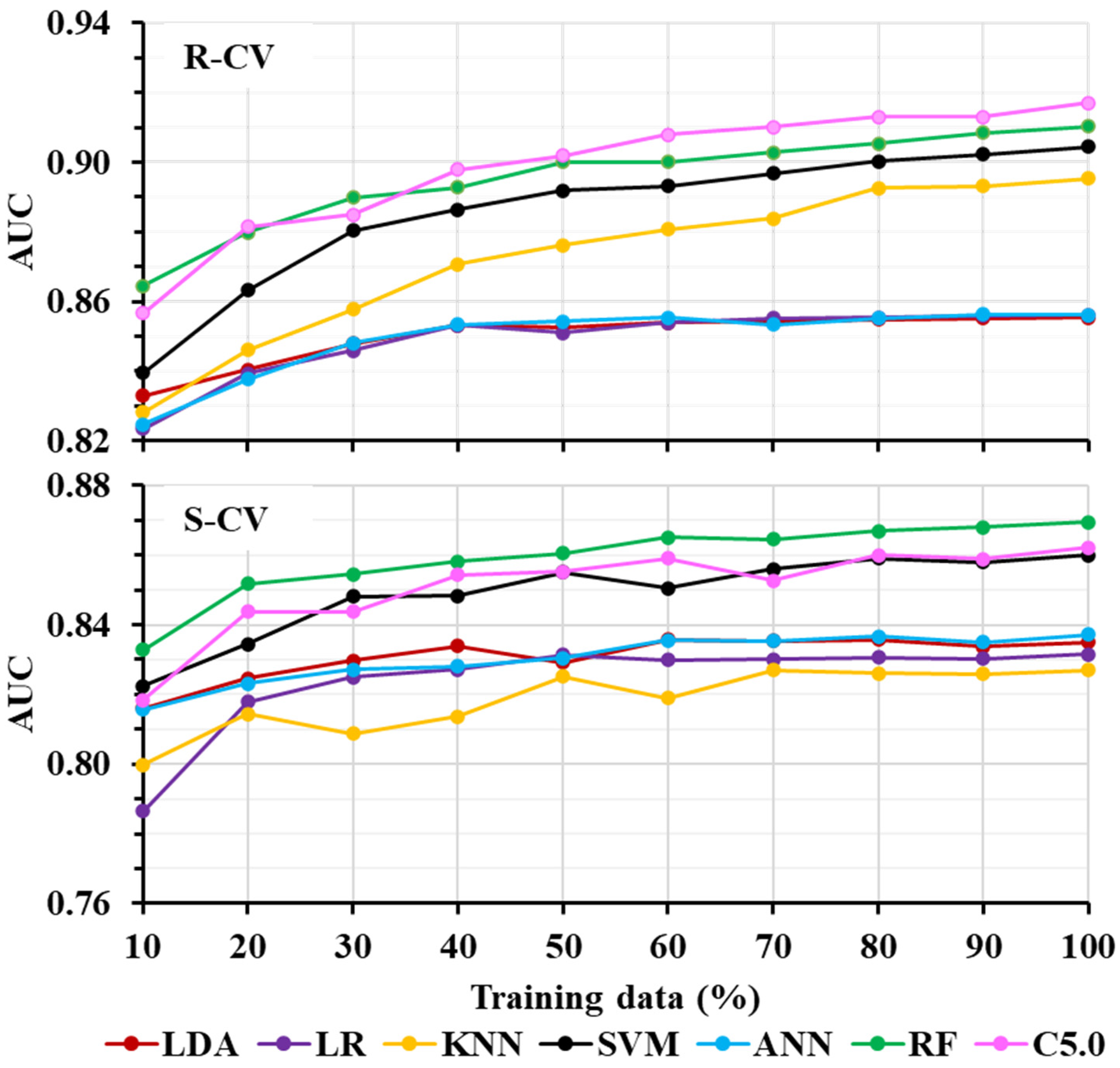

3.3.2. Training Data Quantity and ML Performance

4. Discussion

4.1. Hyperparameter Tuning

4.2. ML Performance and SAC

4.3. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ANN | Artificial neural networks |

| ASTER | Advanced Spaceborne Thermal Emission and Reflection Radiometer |

| AUC | Area under curve |

| DDR | Direct duration radiation |

| DEM | Digital elevation model |

| FN | False negative |

| FP | False positive |

| FR | Frequency ratio |

| GIS | Geographic information system |

| GPM | Global precipitation measurement |

| KNN | K-nearest neighbor |

| LDA | Linear discriminant analysis |

| LIFs | Landslide influencing factors |

| LSM | Landslide susceptibility mapping/modeling |

| LULC | Land use/land cover |

| NDVI | Normalized difference vegetation index |

| OA | Overall accuracy |

| RF | Random forest |

| ROC | Receiver operating characteristic |

| SPI | Stream power index |

| STI | Sediment transportation index |

| SVM | Support vector machine |

| TN | True negative |

| TP | True positive |

| TPI | Topographical position index |

| TRI | Topographical ruggedness index |

| TWI | Topographical wetness index |

| USGS | United States Geological Survey |

| VIF | Variance inflation factor |

References

- Highland, L.M.; Bobrowsky, P. The Landslide Handbook—A Guide to Understanding Landslides; U.S. Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 2008.

- EM-DAT, C. Em-Dat: The Ofda/Cred International Disaster Database; Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters, Universidad Católic a de Lovaina: Ottignies-Louvain-la-Neuve, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Keefer, D.K.; Larsen, M.C. Assessing landslide hazards. Science 2007, 316, 1136–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.; Zhang, S.; Li, R.; Shahabi, H. Performance evaluation of the GIS-based data mining techniques of best-first decision tree, random forest, and naïve Bayes tree for landslide susceptibility modeling. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 644, 1006–1018. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Adnan, M.S.G.; Rahman, M.S.; Ahmed, N.; Ahmed, B.; Rabbi, M.F.; Rahman, R.M. Improving spatial agreement in machine learning-based landslide susceptibility mapping. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 3347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Napoli, M.; Carotenuto, F.; Cevasco, A.; Confuorto, P.; Di Martire, D.; Firpo, M.; Pepe, G.; Raso, E.; Calcaterra, D. Machine learning ensemble modelling as a tool to improve landslide susceptibility mapping reliability. Landslides 2020, 17, 1897–1914. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, S.A.; Parvin, F.; Vojteková, J.; Costache, R.; Linh, N.T.T.; Pham, Q.B.; Vojtek, M.; Gigović, L.; Ahmad, A.; Ghorbani, M.A. GIS-based landslide susceptibility modeling: A comparison between fuzzy multi-criteria and machine learning algorithms. Geosci. Front. 2021, 12, 857–876. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, C.; Walton, G.; Santi, P.; Luza, C. An Ensemble Approach of Feature Selection and Machine Learning Models for Regional Landslide Susceptibility Mapping in the Arid Mountainous Terrain of Southern Peru. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalantar, B.; Ueda, N.; Saeidi, V.; Ahmadi, K.; Halin, A.A.; Shabani, F. Landslide susceptibility mapping: Machine and ensemble learning based on remote sensing big data. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Lin, Q.; Wang, Y. Landslide susceptibility mapping on a global scale using the method of logistic regression. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2017, 17, 1411–1424. [Google Scholar]

- Pandey, V.K.; Pourghasemi, H.R.; Sharma, M.C. Landslide susceptibility mapping using maximum entropy and support vector machine models along the Highway Corridor, Garhwal Himalaya. Geocarto Int. 2020, 35, 168–187. [Google Scholar]

- Pourghasemi, H.R.; Sadhasivam, N.; Amiri, M.; Eskandari, S.; Santosh, M. Landslide susceptibility assessment and mapping using state-of-the art machine learning techniques. Nat. Hazards 2021, 108, 1291–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, B. A comparative study on the predictive ability of the decision tree, support vector machine and neuro-fuzzy models in landslide susceptibility mapping using GIS. Comput. Geosci. 2013, 51, 350–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanyu, B.F.; Abbaspour, A.; Alimohammadlou, Y.; Tecuci, G. Landslide susceptibility analyses using Random Forest, C4.5., and C5.0. with balanced and unbalanced datasets. Catena 2021, 203, 105355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Fang, Z.; Wang, M.; Peng, L.; Hong, H. Comparative study of landslide susceptibility mapping with different recurrent neural networks. Comput. Geosci. 2020, 138, 104445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobler, W.R. A computer movie simulating urban growth in the Detroit region. Econ. Geogr. 1970, 46, 234–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, D.; Kim, A.Y. A permutation test and spatial cross-validation approach to assess models of interspecific competition between trees. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0229930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieske, D.; Bender, D. A Robust Test of Spatial Predictive Models: Geographic Cross-Validation. J. Environ. Inform. 2011, 17, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, D.R.; Bahn, V.; Ciuti, S.; Boyce, M.S.; Elith, J.; Guillera-Arroita, G.; Hauenstein, S.; Lahoz-Monfort, J.J.; Schröder, B.; Thuiller, W. Cross-validation strategies for data with temporal, spatial, hierarchical, or phylogenetic structure. Ecography 2017, 40, 913–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weidner, L.; Walton, G. The influence of training data variability on a supervised machine learning classifier for Structure from Motion (SfM) point clouds of rock slopes. Eng. Geol. 2021, 294, 106344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weidner, L.; Walton, G.; Kromer, R. Generalization considerations and solutions for point cloud hillslope classifiers. Geomorphology 2020, 354, 107039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Journel, A.G.; Huijbregts, C.J. Mining Geostatistics. 1976. Available online: https://www.osti.gov/etdeweb/biblio/5214736 (accessed on 15 March 2022).

- Pawluszek-Filipiak, K.; Oreńczak, N.; Pasternak, M. Investigating the effect of cross-modeling in landslide susceptibility mapping. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 6335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ploton, P.; Mortier, F.; Réjou-Méchain, M.; Barbier, N.; Picard, N.; Rossi, V.; Dormann, C.; Cornu, G.; Viennois, G.; Bayol, N.; et al. Spatial validation reveals poor predictive performance of large-scale ecological mapping models. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 4540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pohjankukka, J.; Pahikkala, T.; Nevalainen, P.; Heikkonen, J. Estimating the prediction performance of spatial models via spatial k-fold cross validation. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2017, 31, 2001–2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schratz, P.; Muenchow, J.; Iturritxa, E.; Richter, J.; Brenning, A. Hyperparameter tuning and performance assessment of statistical and machine-learning algorithms using spatial data. Ecol. Model. 2019, 406, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Airola, A.; Pohjankukka, J.; Torppa, J.; Middleton, M.; Nykänen, V.; Heikkonen, J.; Pahikkala, T. The spatial leave-pair-out cross-validation method for reliable AUC estimation of spatial classifiers. Data Min. Knowl. Discov. 2019, 33, 730–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, T.P.; Parmezan, A.R.; Batista, G.E. A graph-based spatial cross-validation approach for assessing models learned with selected features to understand election results. In Proceedings of the 2021 20th IEEE International Conference on Machine Learning and Applications (ICMLA), Pasadena, CA, USA, 13–16 December 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, M.; Cavieres, J.; Moraga, P. A Comparison of Spatial and Nonspatial Methods in Statistical Modeling of NO 2: Prediction Accuracy, Uncertainty Quantification, and Model Interpretation. Geogr. Anal. 2023, 55, 703–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deppner, J.; Cajias, M. Accounting for spatial autocorrelation in algorithm-driven hedonic models: A spatial cross-validation approach. J. Real Estate Financ. Econ. 2022, 68, 235–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Althuwaynee, O.F.; Pradhan, B.; Lee, S. A novel integrated model for assessing landslide susceptibility mapping using CHAID and AHP pair-wise comparison. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2016, 37, 1190–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, A.-X.; Miao, Y.; Wang, R.; Zhu, T.; Deng, Y.; Liu, J.; Yang, L.; Qin, C.-Z.; Hong, H. A comparative study of an expert knowledge-based model and two data-driven models for landslide susceptibility mapping. Catena 2018, 166, 317–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devkota, K.C.; Regmi, A.D.; Pourghasemi, H.R.; Yoshida, K.; Pradhan, B.; Ryu, I.C.; Dhital, M.R.; Althuwaynee, O.F. Landslide susceptibility mapping using certainty factor, index of entropy and logistic regression models in GIS and their comparison at Mugling–Narayanghat road section in Nepal Himalaya. Nat. Hazards 2013, 65, 135–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magliulo, P.; Di Lisio, A.; Russo, F.; Zelano, A. Geomorphology and landslide susceptibility assessment using GIS and bivariate statistics: A case study in southern Italy. Nat. Hazards 2008, 47, 411–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, H.-J.; Pradhan, B. Application of a neuro-fuzzy model to landslide-susceptibility mapping for shallow landslides in a tropical hilly area. Comput. Geosci. 2011, 37, 1264–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, J.P.; Gallant, J.C. Terrain Analysis: Principles and Applications; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Riley, S.J.; DeGloria, S.D.; Elliot, R. Index that quantifies topographic heterogeneity. Intermt. J. Sci. 1999, 5, 23–27. [Google Scholar]

- Regmi, N.R.; Giardino, J.R.; Vitek, J.D. Modeling susceptibility to landslides using the weight of evidence approach: Western Colorado, USA. Geomorphology 2010, 115, 172–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, I.D.; Wilson, J.P. Length-slope factors for the Revised Universal Soil Loss Equation: Simplified method of estimation. J. Soil Water Conserv. 1992, 47, 423–428. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.-Y.; Yu, F.-C. Morphometric analysis of debris flows and their source areas using GIS. Geomorphology 2011, 129, 387–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumm, S.A. Evolution of drainage systems and slopes in badlands at Perth Amboy, New Jersey. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 1956, 67, 597–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorsevski, P.V.; Jankowski, P. An optimized solution of multi-criteria evaluation analysis of landslide susceptibility using fuzzy sets and Kalman filter. Comput. Geosci. 2010, 36, 1005–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, B.; Sezer, E.A.; Gokceoglu, C.; Buchroithner, M.F. Landslide susceptibility mapping by neuro-fuzzy approach in a landslide-prone area (Cameron Highlands, Malaysia). IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2010, 48, 4164–4177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juliev, M.; Mergili, M.; Mondal, I.; Nurtaev, B.; Pulatov, A.; Hübl, J. Comparative analysis of statistical methods for landslide susceptibility mapping in the Bostanlik District, Uzbekistan. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 653, 801–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Yang, J.; Xu, C.; Xu, C.; Song, C. Local-scale landslide susceptibility mapping using the B-GeoSVC model. Landslides 2019, 16, 1301–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, H.; Hürlimann, M.; Molowny-Horas, R.; González, M.; Pinyol, J.; Abancó, C.; Ma, J. Relation between land cover and landslide susceptibility in Val d’Aran, Pyrenees (Spain): Historical aspects, present situation and forward prediction. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 693, 133557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Wang, R.; Jiang, Y.; Liu, H.; Wei, Z. GIS-based logistic regression for rainfall-induced landslide susceptibility mapping under different grid sizes in Yueqing, Southeastern China. Eng. Geol. 2019, 259, 105147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, J.-Y.; Lee, K.T.; Chang, T.-C.; Wang, Z.-Y.; Liao, Y.-H. Influences of spatial distribution of soil thickness on shallow landslide prediction. Eng. Geol. 2012, 124, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Evangelista, D. Earthquake-induced landslide-susceptibility mapping using an artificial neural network. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2006, 6, 687–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, D.T.; Lofman, O.; Revhaug, I.; Dick, O. Landslide susceptibility analysis in the Hoa Binh province of Vietnam using statistical index and logistic regression. Nat. Hazards 2011, 59, 1413–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regmi, A.D.; Dhital, M.R.; Zhang, J.-q.; Su, L.-j.; Chen, X.-q. Landslide susceptibility assessment of the region affected by the 25 April 2015 Gorkha earthquake of Nepal. J. Mt. Sci. 2016, 13, 1941–1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Dai, F.; Xu, X.; Lee, Y.H. GIS-based support vector machine modeling of earthquake-triggered landslide susceptibility in the Jianjiang River watershed, China. Geomorphology 2012, 145–146, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Chen, C.; Kechadi, T.M.; Sun, L. A comparative evaluation of filter-based feature selection methods for hyper-spectral band selection. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2013, 34, 7974–7990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bommert, A.; Sun, X.; Bischl, B.; Rahnenführer, J.; Lang, M. Benchmark for filter methods for feature selection in high-dimensional classification data. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2020, 143, 106839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHugh, M.L. The chi-square test of independence. Biochem. Medica 2013, 23, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bischl, B.; Lang, M.; Kotthoff, L.; Schiffner, J.; Richter, J.; Studerus, E.; Casalicchio, G.; Jones, Z.M. mlr: Machine Learning in R. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2016, 17, 5938–5942. [Google Scholar]

- Ayodele, T.O. Types of machine learning algorithms. New Adv. Mach. Learn. 2010, 3, 19–48. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, S. The basics of machine learning: Strategies and techniques. In Artificial Intelligence and Deep Learning in Pathology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 13–40. [Google Scholar]

- Jo, T. Machine Learning Foundations. In Supervised Unsupervised Advanced Learning; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Pandya, R.; Pandya, J. C5. 0 algorithm to improved decision tree with feature selection and reduced error pruning. Int. J. Comput. Appl. 2015, 117, 18–21. [Google Scholar]

- Xanthopoulos, P.; Pardalos, P.M.; Trafalis, T.B. Linear discriminant analysis. In Robust Data Mining; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 27–33. [Google Scholar]

- Cervantes, J.; Garcia-Lamont, F.; Rodríguez-Mazahua, L.; Lopez, A. A comprehensive survey on support vector machine classification: Applications, challenges and trends. Neurocomputing 2020, 408, 189–215. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, A.K.; Mao, J.; Mohiuddin, K.M. Artificial neural networks: A tutorial. Computer 1996, 29, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, M. Random forest classifier for remote sensing classification. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2005, 26, 217–222. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn, M.; Johnson, K. Classification trees and rule-based models. In Applied Predictive Modeling; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 369–413. [Google Scholar]

- Naimi, B.; Hamm, N.A.; Groen, T.A.; Skidmore, A.K.; Toxopeus, A.G.; Alibakhshi, S. ELSA: Entropy-based local indicator of spatial association. Spat. Stat. 2019, 29, 66–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, S.; Roy, J.; Pradhan, B.; Hembram, T.K. Hybrid ensemble machine learning approaches for landslide susceptibility mapping using different sampling ratios at East Sikkim Himalayan, India. Adv. Space Res. 2021, 68, 2819–2840. [Google Scholar]

- Baartman, J.E.; Melsen, L.A.; Moore, D.; van der Ploeg, M.J. On the complexity of model complexity: Viewpoints across the geosciences. Catena 2020, 186, 104261. [Google Scholar]

- May, R.; Dandy, G.; Maier, H. Review of input variable selection methods for artificial neural networks. Artif. Neural Netw.-Methodol. Adv. Biomed. Appl. 2011, 10, 19–45. [Google Scholar]

- Bergstra, J.; Bengio, Y. Random search for hyper-parameter optimization. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2012, 13, 281–305. [Google Scholar]

| LIF | Data and Resolution | References |

|---|---|---|

| Elevation | ASTER DEM (30 m) | [31,32] |

| Aspect | [12,33] | |

| Slope | [34] | |

| Profile curvature | [35] | |

| Topographical position index (TPI) | [36] | |

| Topographical roughness index (TRI) | [37] | |

| Topographical wetness index (TWI) | [38] | |

| Stream transportation index (STI) | [39] | |

| Stream power index (SPI) | [40] | |

| Surface relief ratio (SRR) | [41] | |

| Stream/drainage density | [41] | |

| Direct radiation | [7,42] | |

| Direct duration radiation (DRR) | ||

| NDVI | Landsat 8 (30 m) | [43] |

| Geology | Reference maps (1:50,000) | [44,45] |

| Hydrogeology | ||

| Geomorphology | ||

| Land use/land cover | ESRI LULC map, 2020 (10 m) | [46] |

| Rainfall | Averaged GPM data (2010–2020) (10 km) | [47] |

| Soil type | Soil map (250 m) | [48] |

| Distance to major faults | Reference map (1:50,000) | [49] |

| Distance to major roads | Road network (2021) | [50] |

| Earthquake magnitude | USGS historical earthquake data (1973–2021) | [51,52] |

| Distance to epicenter |

| Summary | Pros and Cons | |

|---|---|---|

| LDA | It uses a dimensionality reduction technique to project higher feature spaces to a lower dimension of the input feature set for improved separation of classes [62]. The implemented LDA does not consist of tuning hyperparameters. | Pros: computationally efficient and interpretable. Cons: assumes a normal distribution of data and is sensitive to outliers. |

| LR | It utilizes the logistic function to learn the relationship between binary dependent and input variables. It is frequently used as a baseline model for comparing the effectiveness of other ML models. The implemented LR does not consist of tuning hyperparameters. | Pros: computational effectiveness and interpretable. Cons: requires a large sample size, assumes linearity among dependent and independent variables. |

| KNN | It performs classification and regression tasks on new data by measuring the similarity [5]. k is a tuning hyperparameter in implemented KNN, which implies the number of nearest samples. | Pros: non-parametric and computationally efficient. Cons: sensitive to noise and irrelevant variables. |

| SVM | It uses a hyperplane to separate two classes accurately [63]. The developed SVM has two hyperparameters: cost and gamma, controlling the penalty for wrongly classified samples and the complexity of the hyperplane. | Pros: effective in high-dimensional feature spaces, generalization, and availability of various kernel functions. Cons: computationally intensive and lack of interpretability. |

| ANN | A typical ANN architecture consists of an input, hidden, and output layer. It uses mathematical transformation to find patterns of input data [64]. Size and decay are two hyperparameters of implemented ANN, which implies the number of nodes in the hidden layer and the regularization term. | Pros: features learning, scalability, and ability to learn complex patterns. Cons: computational complexity, huge training data requirements, and lack of interpretability. |

| RF | It consists of many decision trees. RF uses the bagging method to obtain accurate results by generating a random training set with the replacement [65]. The used RF model consists of one hyperparameter, i.e., the number of input variables (mtry) at each split of the decision trees. | Pros: efficient in high-dimensional feature handling, robustness to outliers, and inbuilt feature selection. Cons: memory and computationally intensive. |

| C5.0 | It uses boosting and weighing approaches to develop decision trees to improve the model’s accuracy [66]. The developed C5.0 model has one hyperparameter: trials. This is also known as boosting iterations, which control how many models are used in the final model. | Pros: ability to handle mixed data types, robustness to noise, and inbuilt feature selection. Cons: large training data requirement, sensitive to outliers, and can potentially overfit if a complex model is developed. |

| R-CV | S-CV | Grid Search Space | |

|---|---|---|---|

| KNN | k = 27 | k = 241 | k = 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, 13, 17, 21, 27, 31, 33, 41, 49, 55, 61, 69, 79, 99, 111, 119, 129, 139, 149, 169, 189, 211, 229, 241, 259, 279, 301, 331, 351. |

| SVM | cost = 5 gamma = 0.0443 | cost = 5 gamma = 0.0234 | cost = 1, 5, 10, 15, 20, 30, 40, 50, 60, 80, 100; gamma = 0.0135, 0.0234, 0.0443. |

| ANN | size = 1 decay = 0.01 | size = 1 decay = 0.01 | size = 1, 2, 3, 4, 5; decay = 0.0001, 0.00024, 0.00056, 0.0014, 0.0032, 0.0050, 0.0075, 0.01. |

| RF | mtry = 1 | mtry = 5 | mtry = 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10. |

| C5.0 | trials = 90 | trials = 90 | trials = 5, 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, 60, 70, 80, 90, 100. |

| LDA | LR | KNN | SVM | ANN | RF | C5.0 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R-CV | S-CV | R-CV | S-CV | R-CV | S-CV | R-CV | S-CV | R-CV | S-CV | R-CV | S-CV | R-CV | S-CV | |

| AUC | 0.86 | 0.84 | 0.86 | 0.83 | 0.89 | 0.84 | 0.91 | 0.86 | 0.86 | 0.83 | 0.91 | 0.87 | 0.92 | 0.86 |

| OA | 0.78 | 0.77 | 0.79 | 0.77 | 0.80 | 0.76 | 0.82 | 0.79 | 0.79 | 0.77 | 0.82 | 0.79 | 0.83 | 0.77 |

| Recall | 0.69 | 0.63 | 0.71 | 0.65 | 0.77 | 0.66 | 0.78 | 0.68 | 0.76 | 0.70 | 0.78 | 0.66 | 0.81 | 0.63 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kumar, C.; Walton, G.; Santi, P.; Luza, C. Random Cross-Validation Produces Biased Assessment of Machine Learning Performance in Regional Landslide Susceptibility Prediction. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 213. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17020213

Kumar C, Walton G, Santi P, Luza C. Random Cross-Validation Produces Biased Assessment of Machine Learning Performance in Regional Landslide Susceptibility Prediction. Remote Sensing. 2025; 17(2):213. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17020213

Chicago/Turabian StyleKumar, Chandan, Gabriel Walton, Paul Santi, and Carlos Luza. 2025. "Random Cross-Validation Produces Biased Assessment of Machine Learning Performance in Regional Landslide Susceptibility Prediction" Remote Sensing 17, no. 2: 213. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17020213

APA StyleKumar, C., Walton, G., Santi, P., & Luza, C. (2025). Random Cross-Validation Produces Biased Assessment of Machine Learning Performance in Regional Landslide Susceptibility Prediction. Remote Sensing, 17(2), 213. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17020213