Cross-Validation of GEMS Total Ozone from Ozone Profile and Total Column Products Using Pandora and Satellite Observations

Abstract

Highlights

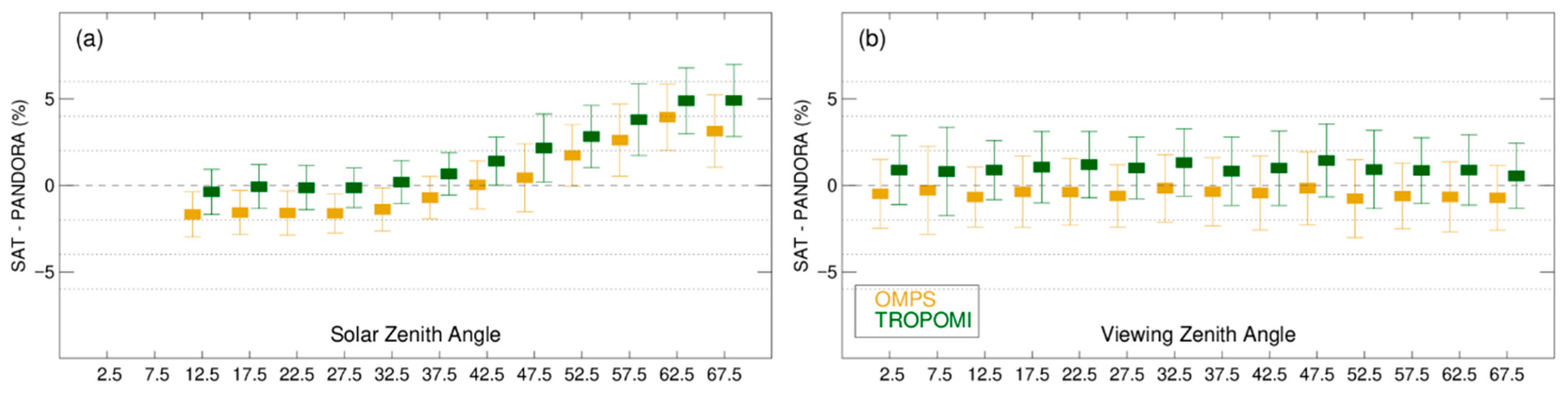

- The reprocessed GEMS v3.0 ozone profile (O3P) product outperforms TROPOMI and OMPS in terms of consistency with Pandora ground-based ozone measurements.

- The reprocessed GEMS v2.1 total ozone (O3T) product still exhibits abnormal geometry-dependent biases.

- The improved O3P performance highlights the effective implementation of corrections addressing calibration uncertainties.

- The remaining biases in O3T point to issues in the L1C radiance and irradiance products that need further investigation.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Satellite Ozone Products

2.2. Pandora Observations

2.3. Comparison Methodology

2.4. Validation Metrics

3. Results

3.1. Intercomparison of Reference Datasets

3.2. Dependence of GEMS Ozone Products on Viewing Geometry

3.3. Dependence of GEMS Products on Temporal Variations

3.4. Validation Metrics for GEMS Total Ozone Relative to Pandora

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Isaksen, I.S.A.; Granier, C.; Myhre, G.; Berntsen, T.K.; Dalsøren, S.B.; Gauss, M.; Klimont, Z.; Benestad, R.; Bousquet, P.; Collins, W.; et al. Atmospheric composition change: Climate–Chemistry interactions. Atmos. Environ. 2009, 43, 5138–5192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monks, P.S.; Archibald, A.T.; Colette, A.; Cooper, O.; Coyle, M.; Derwent, R.; Fowler, D.; Granier, C.; Law, K.S.; Mills, G.E.; et al. Tropospheric ozone and its precursors from the urban to the global scale from air quality to short-lived climate forcer. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2015, 15, 8889–8973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, S. Stratospheric ozone depletion: A review of concepts and history. Rev. Geophys. 1999, 37, 275–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chipperfield, M.P.; Bekki, S.; Dhomse, S.; Harris, N.R.P.; Hassler, B.; Hossaini, R.; Steinbrecht, W.; Thiéblemont, R.; Weber, M. Detecting recovery of the stratospheric ozone layer. Nature 2017, 549, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chipperfield, M.P.; Bekki, S. Opinion: Stratospheric ozone—Depletion, recovery and new challenges. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2024, 24, 2783–2802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weatherhead, E.C.; Andersen, S.B. The search for signs of recovery of the ozone layer. Nature 2006, 441, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levelt, P.F.; Joiner, J.; Tamminen, J.; Veefkind, J.P.; Bhartia, P.K.; Stein Zweers, D.C.; Duncan, B.N.; Streets, D.G.; Eskes, H.; van der A, R.; et al. The Ozone Monitoring Instrument: Overview of 14 years in space. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2018, 18, 5699–5745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPeters, R.D.; Frith, S.; Labow, G.J. OMI total column ozone: Extending the long-term data record. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2015, 8, 4845–4850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, M.; Arosio, C.; Coldewey-Egbers, M.; Fioletov, V.E.; Frith, S.M.; Wild, J.D.; Tourpali, K.; Burrows, J.P.; Loyola, D. Global total ozone recovery trends attributed to ozone-depleting substance (ODS) changes derived from five merged ozone datasets. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2022, 22, 6843–6859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bak, J.; Liu, X.; Kim, J.H.; Chance, K.; Haffner, D.P. Validation of OMI total ozone retrievals from the SAO ozone profile algorithm and three operational algorithms with Brewer measurements. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2015, 15, 667–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balis, D.; Kroon, M.; Koukouli, M.E.; Brinksma, E.J.; Labow, G.; Veefkind, J.P.; McPeters, R.D. Validation of Ozone Monitoring Instrument total ozone column measurements using Brewer and Dobson spectrophotometer ground-based observations. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2007, 112, D07307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garane, K.; Koukouli, M.-E.; Verhoelst, T.; Lerot, C.; Heue, K.-P.; Fioletov, V.; Balis, D.; Bais, A.; Bazureau, A.; Dehn, A.; et al. TROPOMI/S5P total ozone column data: Global ground-based validation and consistency with other satellite missions. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2019, 12, 5263–5287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chehade, W.; Weber, M.; Burrows, J.P. Total ozone trends and variability during 1979–2012 from merged data sets of various satellites. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2014, 14, 7059–7074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Fleming, E.L.; Newman, P.A.; Liang, Q.; Daniel, J.S. The Impact of Continuing CFC-11 Emissions on Stratospheric Ozone. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2020, 125, e2019JD031849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Jeong, U.; Ahn, M.-H.; Kim, J.H.; Park, R.J.; Lee, H.; Song, C.H.; Choi, Y.-S.; Lee, K.-H.; Yoo, J.-M.; et al. New era of air quality monitoring from space: Geostationary environment monitoring spectrometer (GEMS). Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2020, 101, E1–E22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, K.; Kim, J.H.; Bak, J.; Haffner, D.P.; Kang, M.; Hong, H. Evaluation of total ozone measurements from Geostationary Environmental Monitoring Spectrometer (GEMS). Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2023, 16, 5461–5478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bak, J.; Keppens, A.; Choi, D.; Hong, S.; Kim, J.-H.; Kim, C.-H.; Lee, H.-J.; Jeon, W.; Kim, J.; Koo, J.-H.; et al. GEMS ozone profile retrieval: Impact and validation of version 3.0 improvements. EGUsphere 2025. under review. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, K.; Bak, J.; Kim, J.H.; Park, S.S.; Haffner, D.P.; Lee, W. Validation of geostationary environment monitoring spectrometer (GEMS), TROPOspheric Monitoring Instrument (TROPOMI), and Ozone Mapping and Profiler Suite Nadir Mapper (OMPS) using pandora measurements during GEMS Map of Air Pollution (GMAP) field campaign. Atmos. Environ. 2024, 324, 120408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, J.; Evans, R.; Cede, A.; Abuhassan, N.; Petropavlovskikh, I.; McConville, G. Comparison of ozone retrievals from the Pandora spectrometer system and Dobson spectrophotometer in Boulder, Colorado. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2015, 8, 3407–3418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, J.; Evans, R.; Cede, A.; Abuhassan, N.; Petropavlovskikh, I.; McConville, G.; Miyagawa, K.; Noirot, B. Ozone comparison between Pandora #34, Dobson #061, OMI, and OMPS in Boulder, Colorado, for the period December 2013–December 2016. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2017, 10, 3539–3545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L.-S.; Kim, D.; Hong, H.; Kim, D.-R.; Yu, J.-A.; Lee, K.; Lee, H.; Kim, D.; Hong, J.; Jo, H.-Y.; et al. Evaluation of correlated Pandora column NO_2 and in situ surface NO_2 measurements during GMAP campaign. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2022, 22, 10703–10720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, L.; Long, C.; Wu, X.; Evans, R.; Beck, C.T.; Petropavlovskikh, I.; McConville, G.; Yu, W.; Zhang, Z.; Niu, J.; et al. Performance of the Ozone Mapping and Profiler Suite (OMPS) products. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2014, 119, 6181–6195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veefkind, J.P.; Aben, I.; McMullan, K.; Förster, H.; de Vries, J.; Otter, G.; Claas, J.; Eskes, H.J.; de Haan, J.F.; Kleipool, Q.; et al. TROPOMI on the ESA Sentinel-5 Precursor: A GMES mission for global observations of the atmospheric composition for climate, air quality and ozone layer applications. Remote Sens. Environ. 2012, 120, 70–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schenkeveld, V.M.E.; Jaross, G.; Marchenko, S.; Haffner, D.; Kleipool, Q.L.; Rozemeijer, N.C.; Pepijn Veefkind, J.; Levelt, P.F. In-flight performance of the Ozone Monitoring Instrument. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2017, 10, 1957–1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhartia, P.K.; Wellemeyer, C. TOMS-V8 Total O3 Algorithm, in OMI Algorithm Theoretical Basis Document, vol. II, OMI Ozone Products, ATBD-OMI-02, Edited by P. K. Bhartia, pp. 15–31, NASA Goddard Space Flight Cent., Greenbelt, Md. 2002. Available online: https://eospso.nasa.gov/sites/default/files/atbd/ATBD-OMI-02.pdf (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- Spurr, R.; Loyola, D.; Heue, K.-P.; Van Roozendael, M.; Lerot, C. S5P/TROPOMI Total Ozone ATBD. S5P-L2-DLR-ATBD-400A, Issue 2.4. 2022. Available online: https://sentiwiki.copernicus.eu/ (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- Birk, M.; Wagner, G. ESA SEOM-IAS—Measurement and ACS database O3 UV region (I). Zenodo 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serdyuchenko, A.; Gorshelev, V.; Weber, M.; Chehade, W.; Burrows, J.P. High spectral resolution ozone absorption cross-sections—Part 2: Temperature dependence. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2014, 7, 625–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brion, J.; Chakir, A.; Daumont, D.; Malicet, J.; Parisse, C. High-resolution laboratory absorption cross section of O3. Temperature effect. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1993, 213, 610–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daumont, D.; Brion, J.; Charbonnier, J.; Malicet, J. Ozone UV spectroscopy I: Absorption cross-sections at room temperature. J. Atmos. Chem. 1992, 15, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malicet, J.; Daumont, D.; Charbonnier, J.; Parisse, C.; Chakir, A.; Brion, J. Ozone UV spectroscopy. II. Absorption cross-sections and temperature dependence. J. Atmos. Chem. 1995, 21, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Jeong, U.; Lee, H.; Jung, Y.; Kim, J.H. Assessments of the GEMS NO2 Products Using Ground-Based Pandora and In-Situ Instruments over Busan, South Korea. Korean J. Remote Sens. 2024, 40, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, J.; Cede, A.; Spinei, E.; Mount, G.; Tzortziou, M.; Abuhassan, N. NO2 column amounts from ground-based Pandora and MFDOAS spectrometers using the direct-sun DOAS technique: Intercomparisons and application to OMI validation. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2009, 114, D13307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romahn, F.; Pedergnana, M.; Loyola, D.; Apituley, A.; Sneep, M.; Veefkind, J.P. Sentinel-5 Precursor/TROPOMI Level 2 Product User Manual: O3 Total Column. S5P-L2-DLR-PUM-400A, Issue 2.4.0. 2022. Available online: https://sentinels.copernicus.eu/documents/247904/2474726/Sentinel-5P-TROPOMI-Level-2-Product-User-Manual-Ozone-profiles.pdf (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- Herman, J.; Mao, J.; Huang, L.; Cede, A. Validation of DSCOVR-EPIC Total Column O3 Retrievals Using Ground-Based Pandora as well as OMPS, OMI, and TEMPO Satellite Data. Front. Remote Sens. 2025, 6, 1623828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bak, J.; Kim, J.H.; Spurr, R.J.D.; Liu, X.; Newchurch, M.J. Sensitivity study of ozone retrieval from UV measurements on geostationary platforms. Remote Sens. Environ. 2012, 118, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klenk, K.F.; Bhartia, P.K.; Kaveeshwar, V.G.; McPeters, R.D.; Smith, P.M.; Fleig, A.J. Total ozone determination from the Backscattered Ultraviolet (BUV) Experiment. J. Appl. Meteor. Climatol. 1982, 21, 1672–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Yang, K. Algorithm theoretical basis for ozone and sulfur dioxide retrievals from DSCOVR EPIC. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2022, 15, 5877–5915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Satellite Products | GEMS (O3P) | GEMS (O3T) | OMPS | TROPOMI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Platform | GK-2B | Suomi-NPP | Sentinel-5p | |

| Launch Date | 18 February 2020 | 28 October 2011 | 13 October 2017 | |

| Spatial Resolution (km2) | 14 × 30.8 (4 × 4 binned) | 3.5 × 7.7 (no binned) 7.0 × 15.4 (2 × 2 binned) 14 × 30.8 (4 × 4 binned) | 50 × 50 | 3.5 × 5.5 (since August 2019) |

| Number of spatial (cross-track) pixels | 512 | 512, 1024, 2048 (4 × 4, 2 × 2, 1 × 1) | 36 | 450 |

| Temporal Coverage | 07:45–16:45 LT in Korea (geostationary, hourly) | 13:30 LT when crossing equator (sun-synchronous) | ||

| Retrieval algorithm (reference) | Optimal Estimation (Bak et al. [17], under review) | TOMS look-up table (Baek et al. [16]) | TOMS look-up table (Bhartia et al. [25]) | DOAS (Spurr et al. [26]) |

| Ozone cross-section | Birk and Wagner [27] | BDM # | BDM # | Serdyuchenko et al., (2014) [28] |

| No. | Site Name | Country | Latitude, Longitude (deg) | Altitude (m) | Number of Observation Days | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | |||||

| 1 | Dalanzadgad | Mongolia | 43.58, 104.42 | 1466 | 0 | 245 | 365 | 245 |

| 2 | Beijing | China | 40.00, 116.38 | 59 | 166 | 294 | 271 | 0 |

| 3 + | Seoul-KU | South Korea | 37.59, 127.03 | 90 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 275 |

| 4 | Incheon | South Korea | 37.57, 126.64 | 6 | 158 | 298 | 254 | 366 |

| 5 | Seoul | South Korea | 37.56, 126.93 | 86 | 241 | 271 | 167 | 250 |

| 6 | Seoul-SNU | South Korea | 37.46, 126.95 | 116 | 339 | 357 | 342 | 341 |

| 7 + | Yongin | South Korea | 37.34, 127.27 | 122 | 0 | 0 | 214 | 366 |

| 8 | Seosan | South Korea | 36.78, 126.49 | 25 | 230 | 354 | 333 | 330 |

| 9 | Ulsan | South Korea | 35.57, 129.19 | 38 | 158 | 339 | 298 | 258 |

| 10 | Busan | South Korea | 35.23, 129.08 | 71 | 283 | 356 | 286 | 341 |

| 11 | Fukuoka | Japan | 33.55, 130.37 | 55 | 61 | 364 | 184 | 362 |

| 12 | Dhaka | Bangladesh | 23.73, 90.40 | 34 | 0 | 31 | 365 | 303 |

| 13 | Vientiane | Laos | 18.00, 102.58 | 169 | 0 | 0 | 31 | 366 |

| 14 | Bangkok | Thailand | 13.78, 100.54 | 60 | 243 | 365 | 365 | 366 |

| 15 | Songkhla | Thailand | 7.01, 100.50 | 40 | 0 | 153 | 243 | 92 |

| 16 | Banting | Malaysia | 2.82, 101.62 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 276 | 274 |

| 17 | Singapore | Singapore | 1.30, 103.77 | 77 | 0 | 0 | 214 | 366 |

| 18 | Pontianak | Indonesia | 0.04, 109.34 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 306 |

| 19 | Agam | Indonesia | −0.20, 100.32 | 865 | 0 | 122 | 334 | 149 |

| Mid-Latitude (36.78°N–40.00°N) | ||||

| 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | |

| O3P | N = 820 2.07 ± 5.49 (DU) 0.60 ± 1.88 (%) y = 1.03x − 8.70 R = 0.99, RMS = 1.88% | N = 1083 1.28 ± 5.77 (DU) 0.40 ± 1.79 (%) y = 1.00x + 2.09 R = 0.99, RMS = 1.97% | N = 977 −0.34 ± 5.75 (DU) −0.12 ± 1.79 (%) y = 1.01x − 3.85 R = 0.98, RMS = 1.93% | N = 1391 −0.55 ± 6.98 (DU) −0.16 ± 2.09 (%) y = 1.00x − 0.61 R = 0.98, RMS = 2.28% |

| O3T | N = 820 −7.93 ± 4.35 (DU) −2.42 ± 1.31 (%) y = 0.98x − 2.86 R = 0.99, RMS = 2.77% | N = 1083 −10.77 ± 4.73 (DU) −3.25 ± 1.30 (%) y = 0.94x + 9.25 R = 0.99, RMS = 3.50% | N = 977 −13.76 ± 4.95 (DU) −4.21 ± 1.38 (%) y = 0.93x + 9.19 R = 0.99, RMS = 4.44% | N = 1391 −14.62 ± 5.89 (DU) −4.32 ± 1.53 (%) y = 0.92x + 11.26 R = 0.99, RMS = 4.58% |

| TROPOMI | N = 810 4.72 ± 7.26 (DU) 1.48 ± 2.22 (%) y = 0.98x + 11.17 R = 0.98, RMS = 2.75% | N = 1110 7.90 ± 7.45 (DU) 2.41 ± 2.24 (%) y = 1.02x + 1.92 R = 0.98, RMS = 3.44% | N = 1008 5.71 ± 6.92 (DU) 1.76 ± 2.11 (%) y = 1.02x − 0.32 R = 0.97, RMS = 3.28% | N = 1357 5.50 ± 9.01 (DU) 1.69 ± 2.68 (%) y = 0.99x + 7.56 R = 0.97, RMS = 3.99% |

| OMPS | N = 816 2.33 ± 7.22 (DU) 0.71 ± 2.22 (%) y = 1.01x − 0.37 R = 0.97, RMS = 2.52% | N = 1121 3.10 ± 7.93 (DU) 0.98 ± 2.43 (%) y = 0.99x + 7.72 R = 0.97, RMS = 2.93% | N = 1004 1.21 ± 8.01 (DU) 0.37 ± 2.46 (%) y = 1.00x − 0.18 R = 0.96, RMS = 2.67% | N = 1392 1.63 ± 9.00 (DU) 0.52 ± 2.69 (%) y = 0.99x + 5.71 R = 0.98, RMS = 2.97% |

| Sub-tropical (13.78°N–23.73°N) | Tropical (0.2°S –2.82°N) | |||

| 2023 | 2024 | 2023 | 2024 | |

| O3P | N = 738 1.52 ± 3.37 (DU) 0.58 ± 1.26 (%) y = 0.95x 15.80 R = 0.97, RMS = 1.53% | N = 702 1.92 ± 3.84 (DU) 0.74 ± 1.44 (%) y = 0.93x + 20.72 R = 0.97, RMS = 1.69% | N = 638 −1.64 ± 4.57 (DU) −0.60 ± 1.73 (%) y = 0.83x +43.19 R = 0.86, RMS = 1.87% | N = 795 −2.09 ± 3.73 (DU) −0.77 ± 1.42 (%) y = 0.89x + 27.47 R = 0.95, RMS = 1.72% |

| O3T | N = 738 −9.71 ± 3.06 (DU) −3.62 ± 1.12 (%) y = 0.97x − 1.44 R = 0.97, RMS = 3.83% | N = 702 −11.43 ± 3.16 (DU) −4.25 ± 1.15 (%) y = 0.97x − 2.88 R = 0.98, RMS = 4.43% | N = 638 −10.22 ± 6.34 (DU) −3.84 ± 2.34 (%) y = 0.62x + 88.75 R = 0.72, RMS = 4.50% | N = 795 −13.05 ± 4.94 (DU) −4.93 ± 1.78 (%) y = 0.77x + 47.27 R = 0.92, RMS = 5.23% |

| TROPOMI | N = 705 1.19 ± 4.31 (DU) 0.47 ± 1.60 (%) y = 0.93x + 21.16 R = 0.95, RMS = 1.73% | N = 701 0.36 ± 4.87 (DU) 0.18 ± 1.83 (%) y = 0.89x + 30.43 R = 0.93, RMS = 2.26% | N = 641 0.83 ± 4.70 (DU) 0.34 ± 1.80 (%) y = 0.79x + 55.27 R = 0.84, RMS = 1.84% | N = 769 −0.27 ± 3.32 (DU) −0.08 ±1.29 (%) y = 0.90x +26.75 R = 0.96, RMS = 1.39% |

| OMPS | N = 685 −1.86 ± 5.81 (DU) −0.67 ± 2.15 (%) y = 0.94x + 14.47 R = 0.92, RMS = 2.31% | N = 702 −3.15 ± 5.85 (DU) −1.14 ± 2.16 (%) y = 0.89x + 27.59 R = 0.92, RMS = 2.59% | N = 608 −4.61 ± 4.51 (DU) −1.74 ± 1.70 (%) y = 0.84x + 38.36 R = 0.86, RMS = 2.43% | N = 740 −5.54 ± 3.53 (DU) −2.11 ± −1.34 (%) y = 0.91x + 18.99 R = 0.96, RMS = 2.53% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hong, S.; Bak, J.; Keppens, A.; Yang, K.; Baek, K.; Liu, X.; Kim, M.; Kim, J.; Chang, L.-S.; Lee, H.; et al. Cross-Validation of GEMS Total Ozone from Ozone Profile and Total Column Products Using Pandora and Satellite Observations. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3249. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17183249

Hong S, Bak J, Keppens A, Yang K, Baek K, Liu X, Kim M, Kim J, Chang L-S, Lee H, et al. Cross-Validation of GEMS Total Ozone from Ozone Profile and Total Column Products Using Pandora and Satellite Observations. Remote Sensing. 2025; 17(18):3249. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17183249

Chicago/Turabian StyleHong, Sungjae, Juseon Bak, Arno Keppens, Kai Yang, Kanghyun Baek, Xiong Liu, Mijeong Kim, Jhoon Kim, Lim-Seok Chang, Hyunjin Lee, and et al. 2025. "Cross-Validation of GEMS Total Ozone from Ozone Profile and Total Column Products Using Pandora and Satellite Observations" Remote Sensing 17, no. 18: 3249. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17183249

APA StyleHong, S., Bak, J., Keppens, A., Yang, K., Baek, K., Liu, X., Kim, M., Kim, J., Chang, L.-S., Lee, H., & Kim, J.-H. (2025). Cross-Validation of GEMS Total Ozone from Ozone Profile and Total Column Products Using Pandora and Satellite Observations. Remote Sensing, 17(18), 3249. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17183249