Sector-Based Perimeter Reconstruction for Tree Diameter Estimation Using 3D LiDAR Point Clouds

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Robust Framework for Perimeter-Based DBH Estimation: A unified and robust DBH estimation pipeline that integrates angular sector partitioning, GMM-based clustering, and radial symmetry-guided proxy generation to reconstruct complete trunk perimeters from noisy and irregular point clouds.

- Symmetry-Based Proxy Point Generation for Missing Sectors: Proxy point generation leverages radial symmetry to compensate for missing sectors, enabling complete and consistent trunk reconstruction even under occlusion or sparse observations.

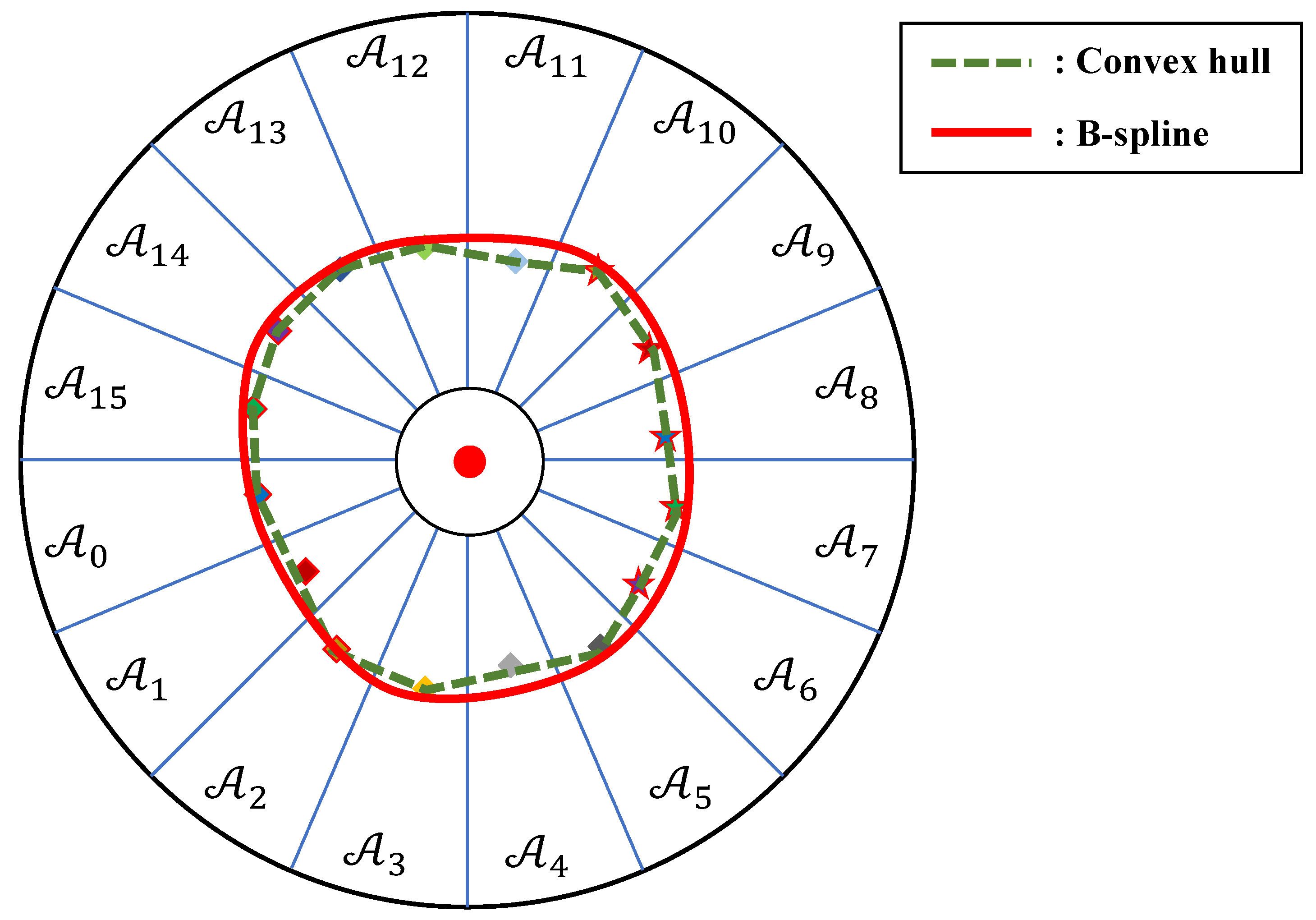

- DBH Computation from Reconstructed Perimeters: Instead of relying on idealized geometric fitting, we estimate DBH from reconstructed trunk perimeters using convex hull modeling over denoised and symmetry-guided points, enabling more accurate and realistic diameter estimation under field conditions.

- Comprehensive Evaluation on Real-World MLS Data: Empirical validation using real-world MLS data, demonstrating improved performance over the baseline method, particularly in the presence of data sparsity and noise.

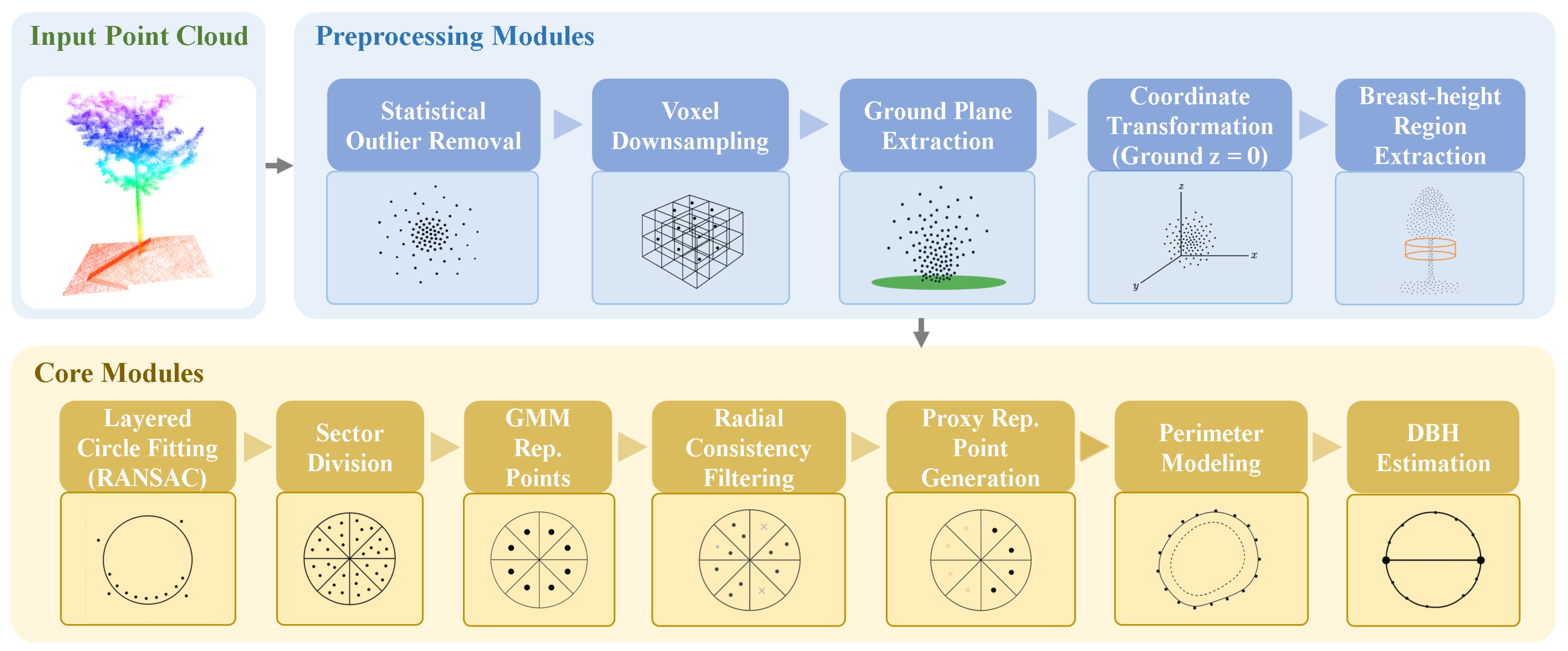

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Description of Datasets

2.1.1. TreeScope Dataset

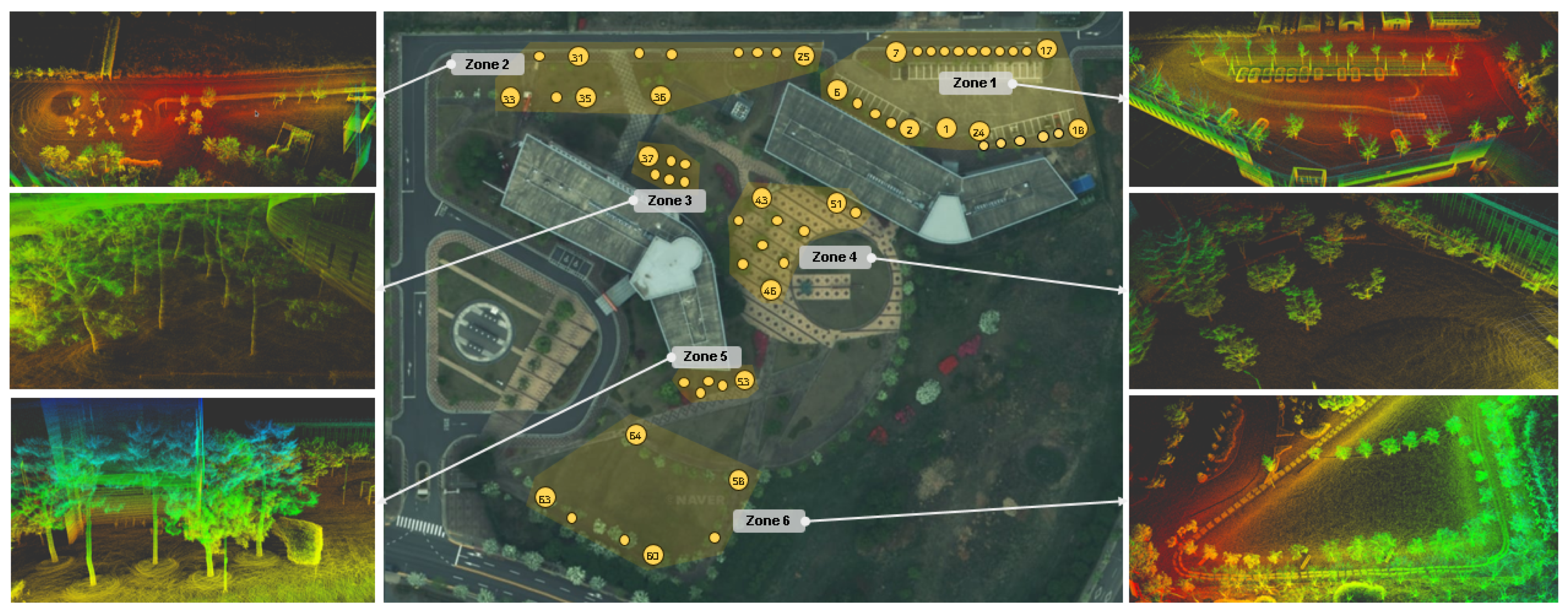

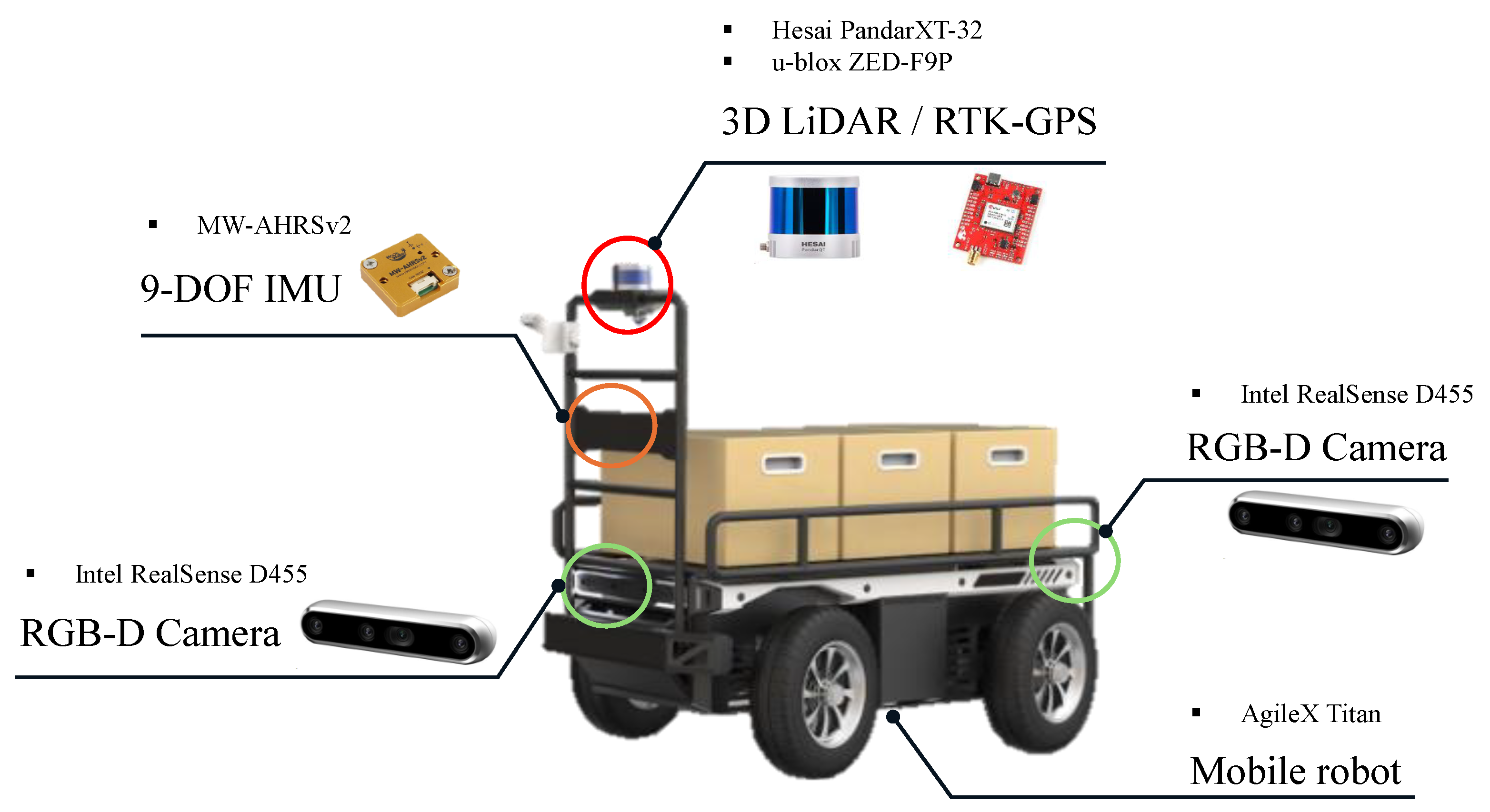

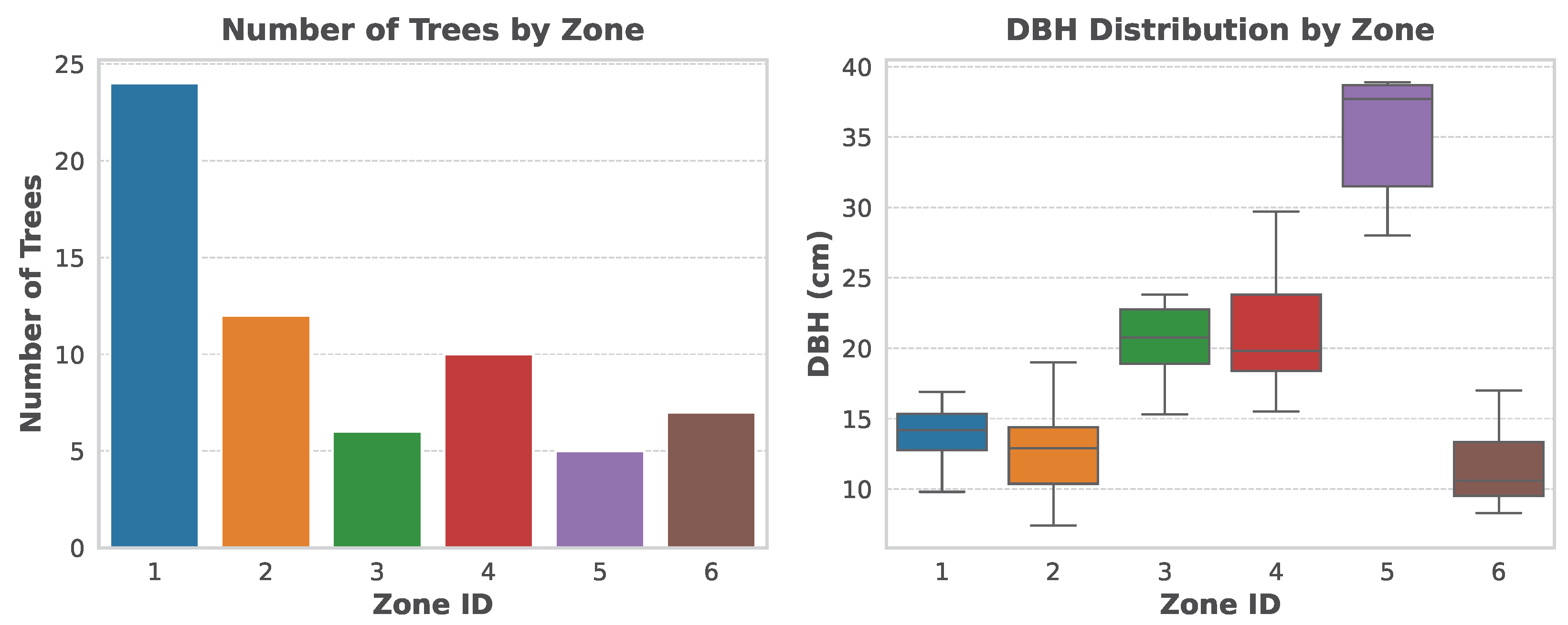

2.1.2. Custom Dataset

2.2. Robust DBH Estimation with Minimal Shape Priors

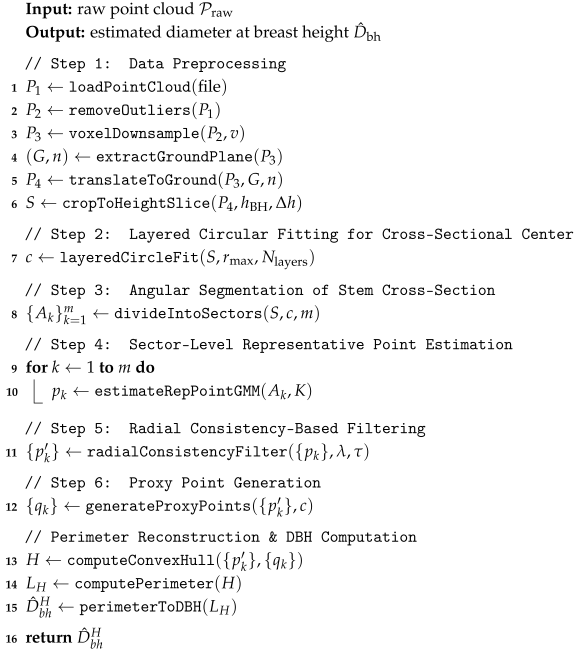

| Algorithm 1: Sector-Based Perimeter Reconstruction Pipeline for DBH Estimation |

|

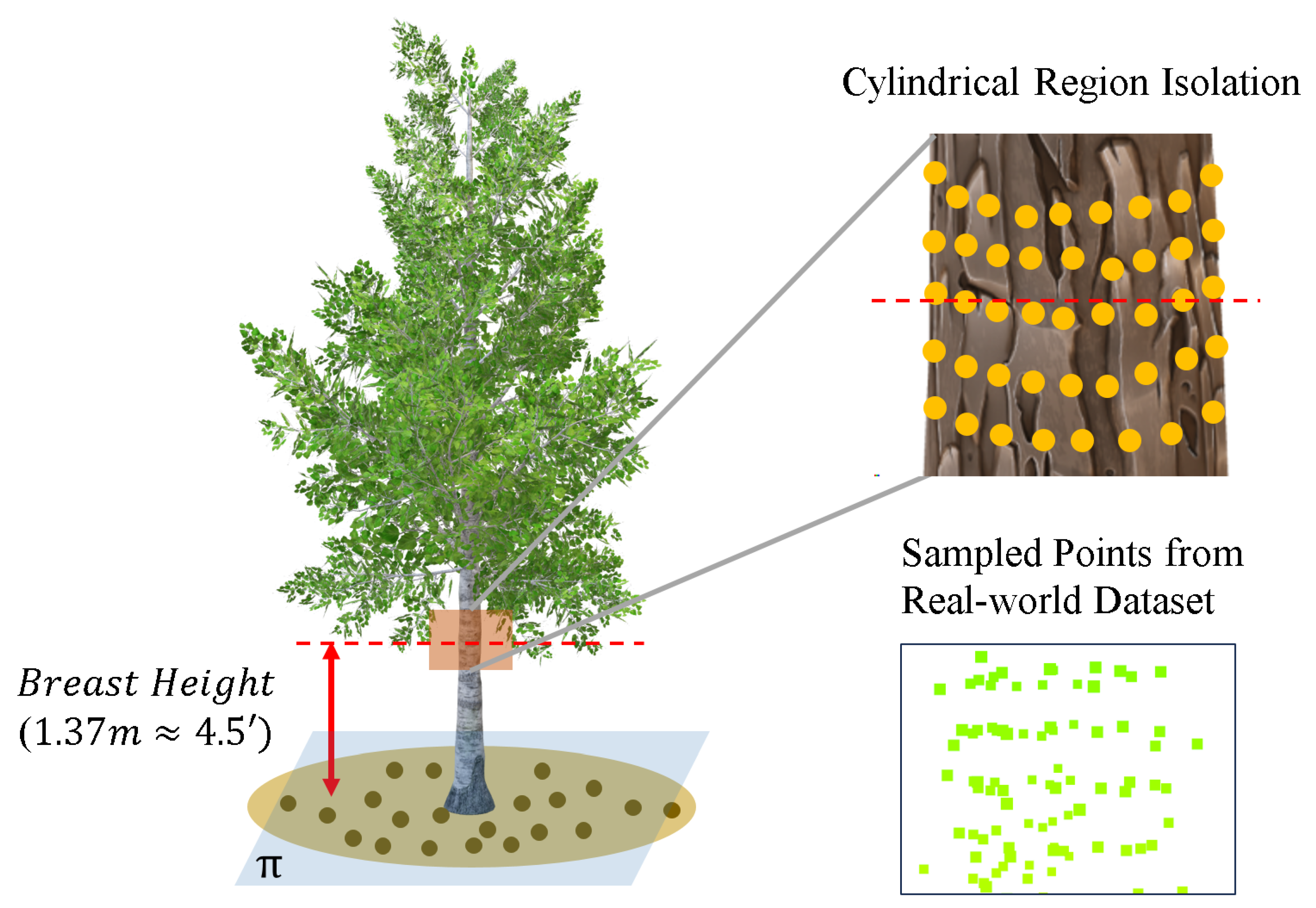

2.2.1. Preprocessing Pipeline for DBH Region Extraction

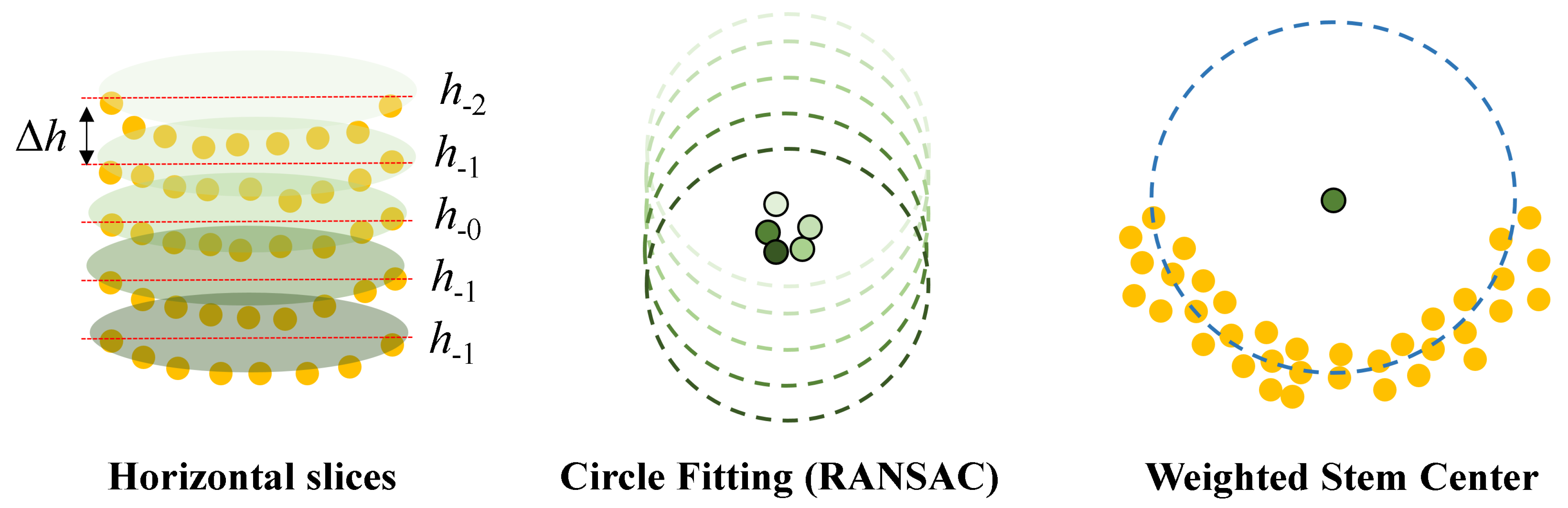

2.2.2. Layered Circular Fitting for Cross-Sectional Center Refinement

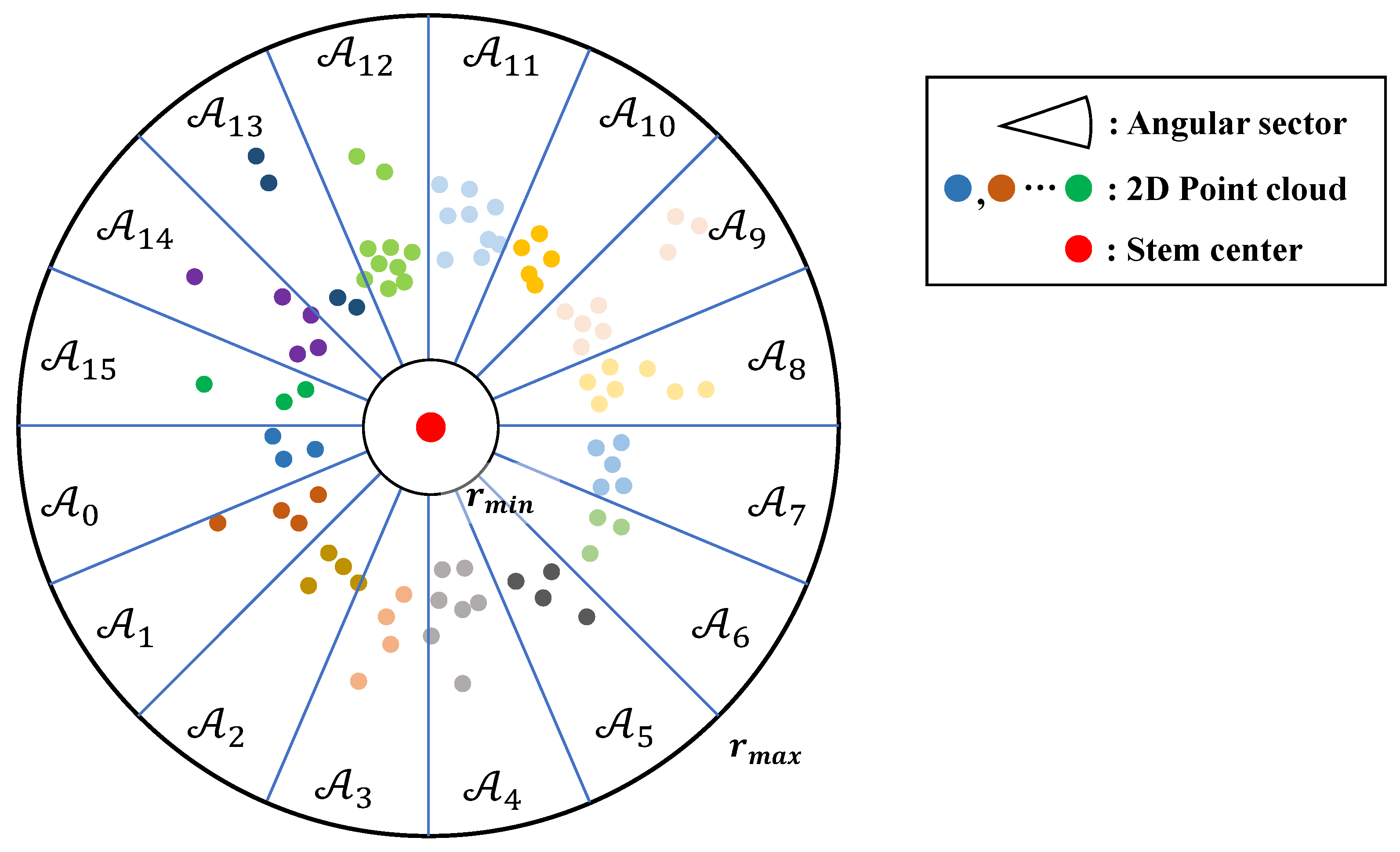

2.2.3. Angular Segmentation of Stem Cross-Section

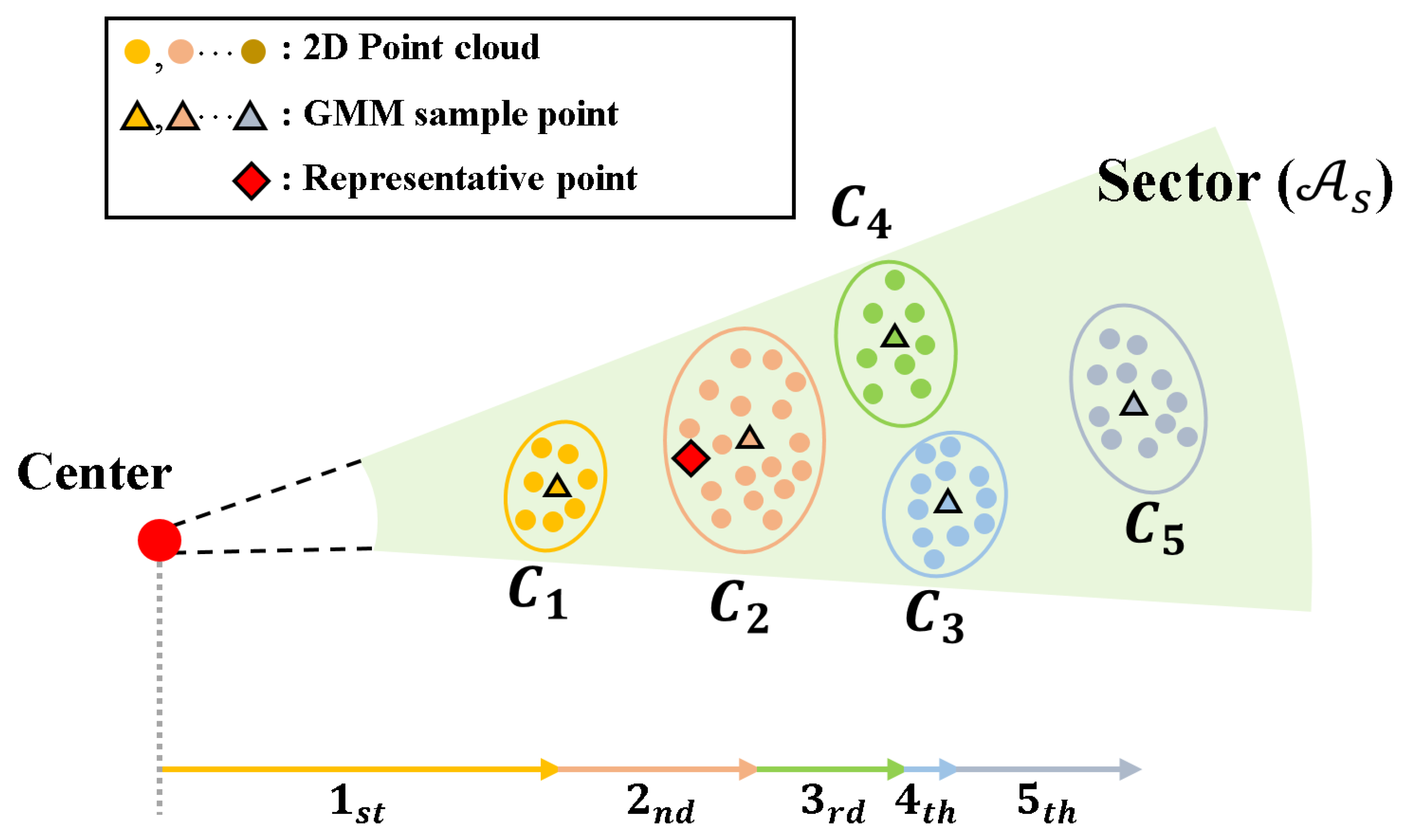

2.2.4. Sector-Level Representative Point Estimation via Gaussian Mixture Modeling

2.2.5. Radial Consistency-Based Filtering of Representative Points

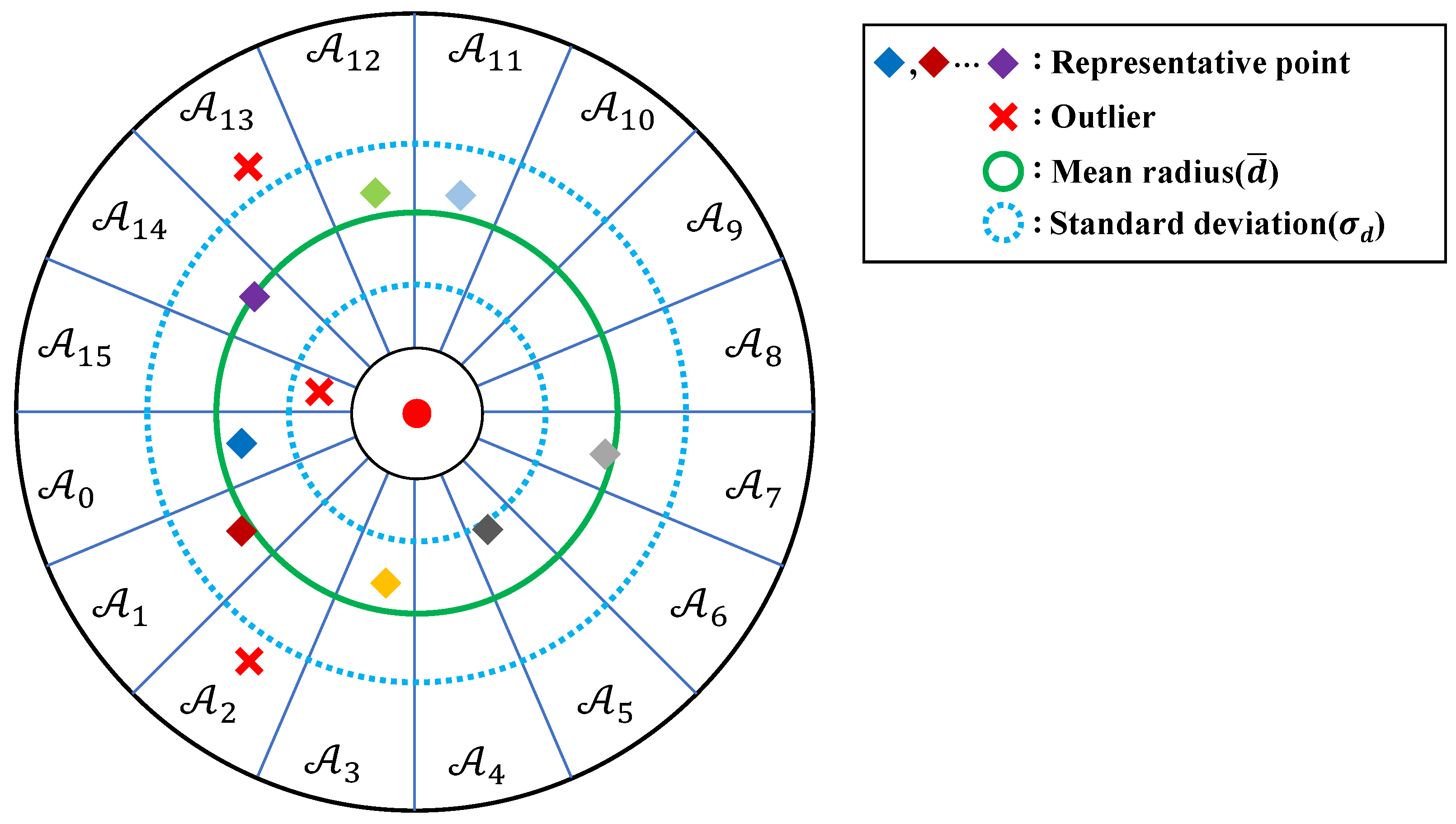

- Neighbor-Gap Test: For each sector , define the maximum radial difference relative to its immediate neighbors,with circular indexing (). A sector is flagged as an outlier if , where is a user-defined threshold.

- Global Deviation Test: Compute a standardized deviation score for each sector,and deem an outlier if , where is a user-defined threshold.

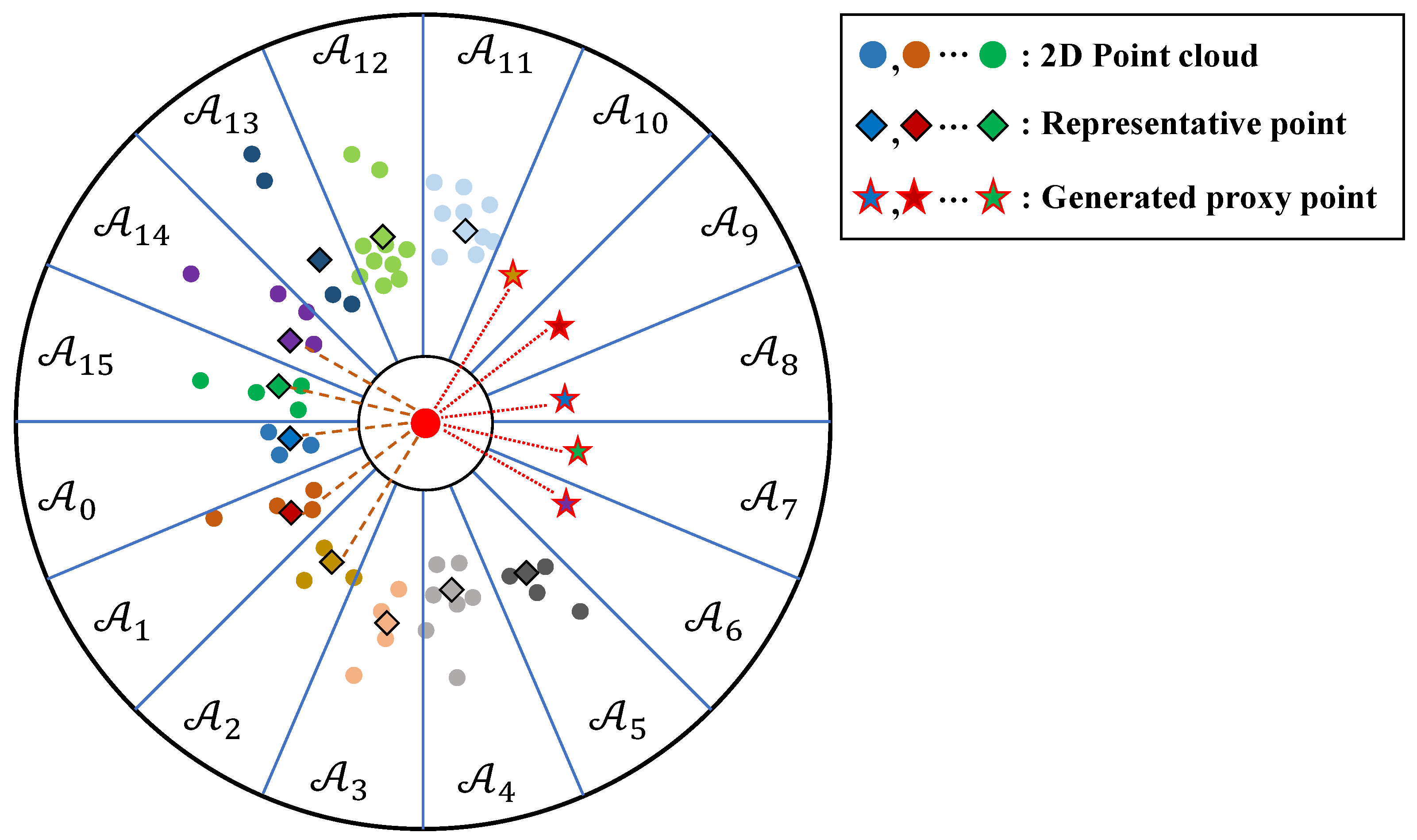

2.2.6. Symmetry-Aware Reconstruction of Missing Representative Points

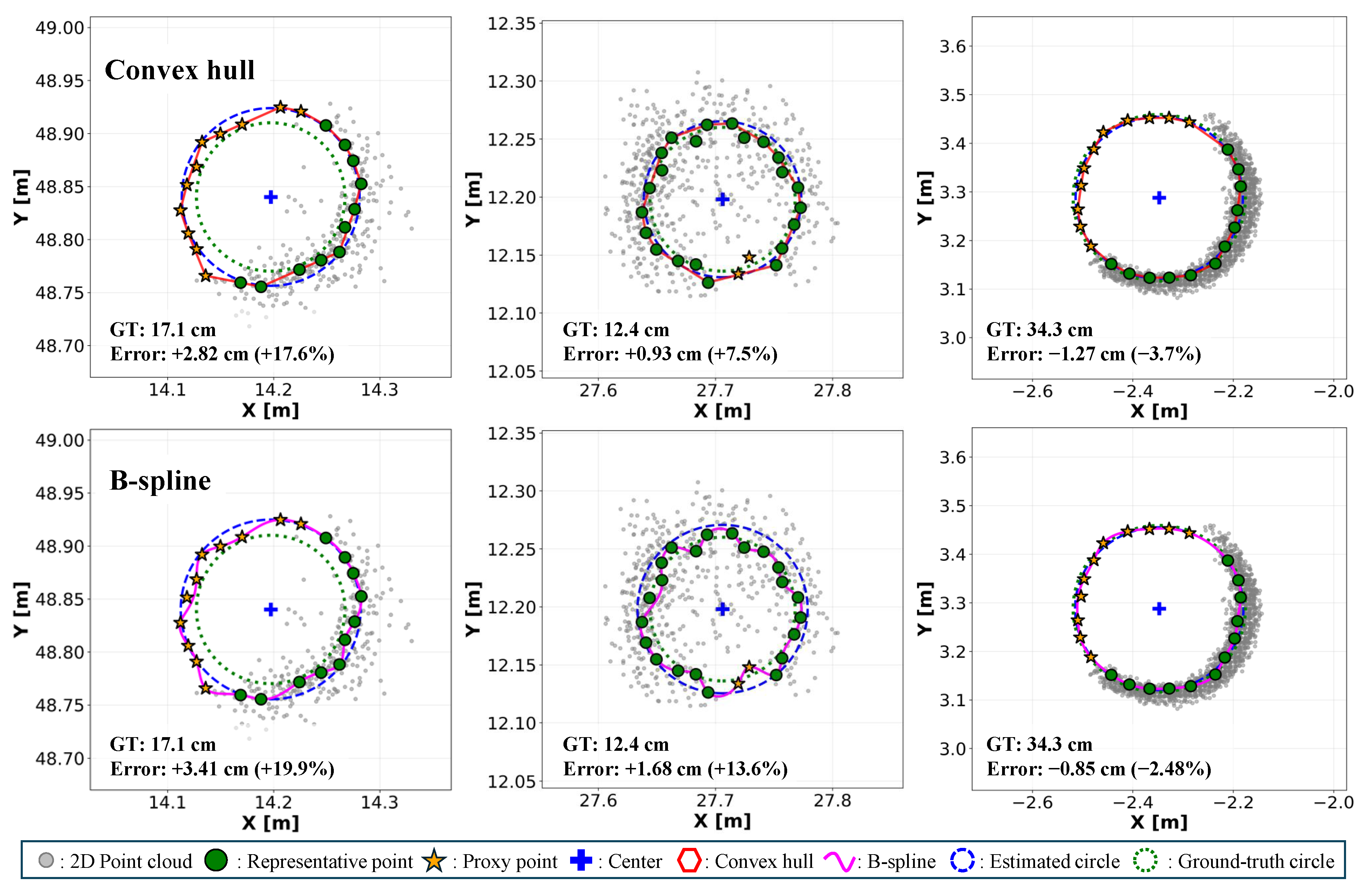

2.2.7. Perimeter and DBH Estimation via Convex Hull and B-Spline Models

3. Results

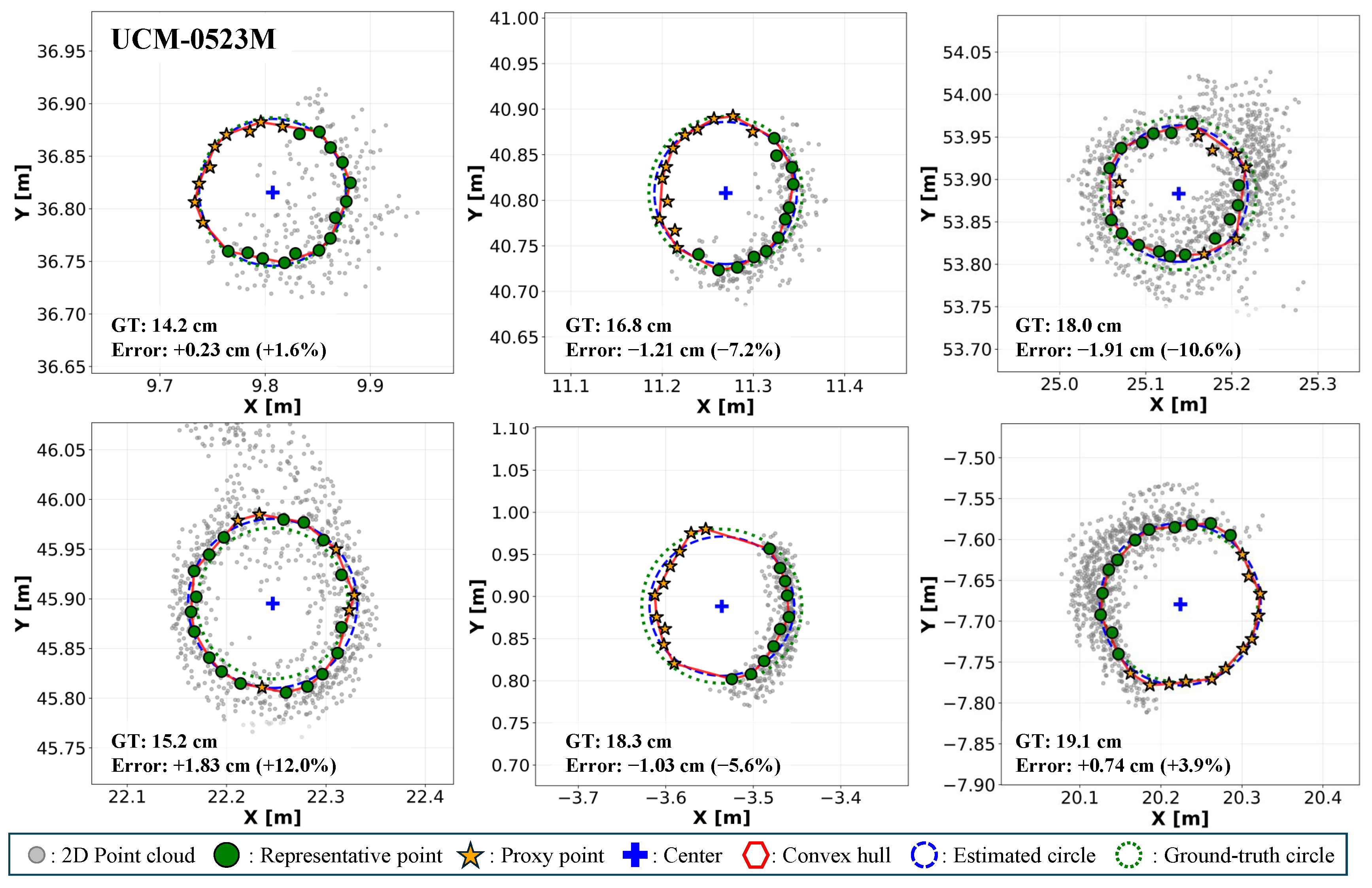

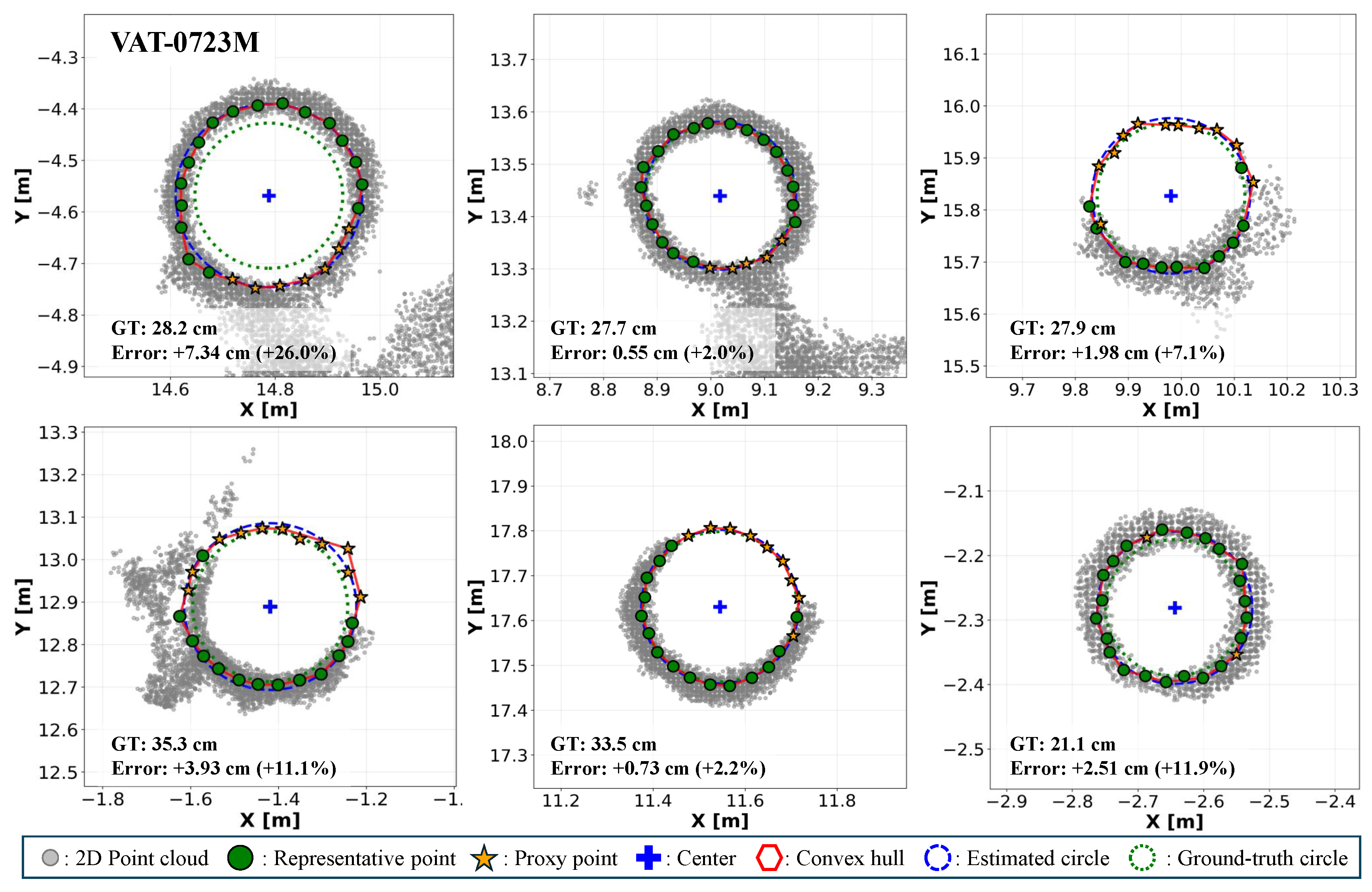

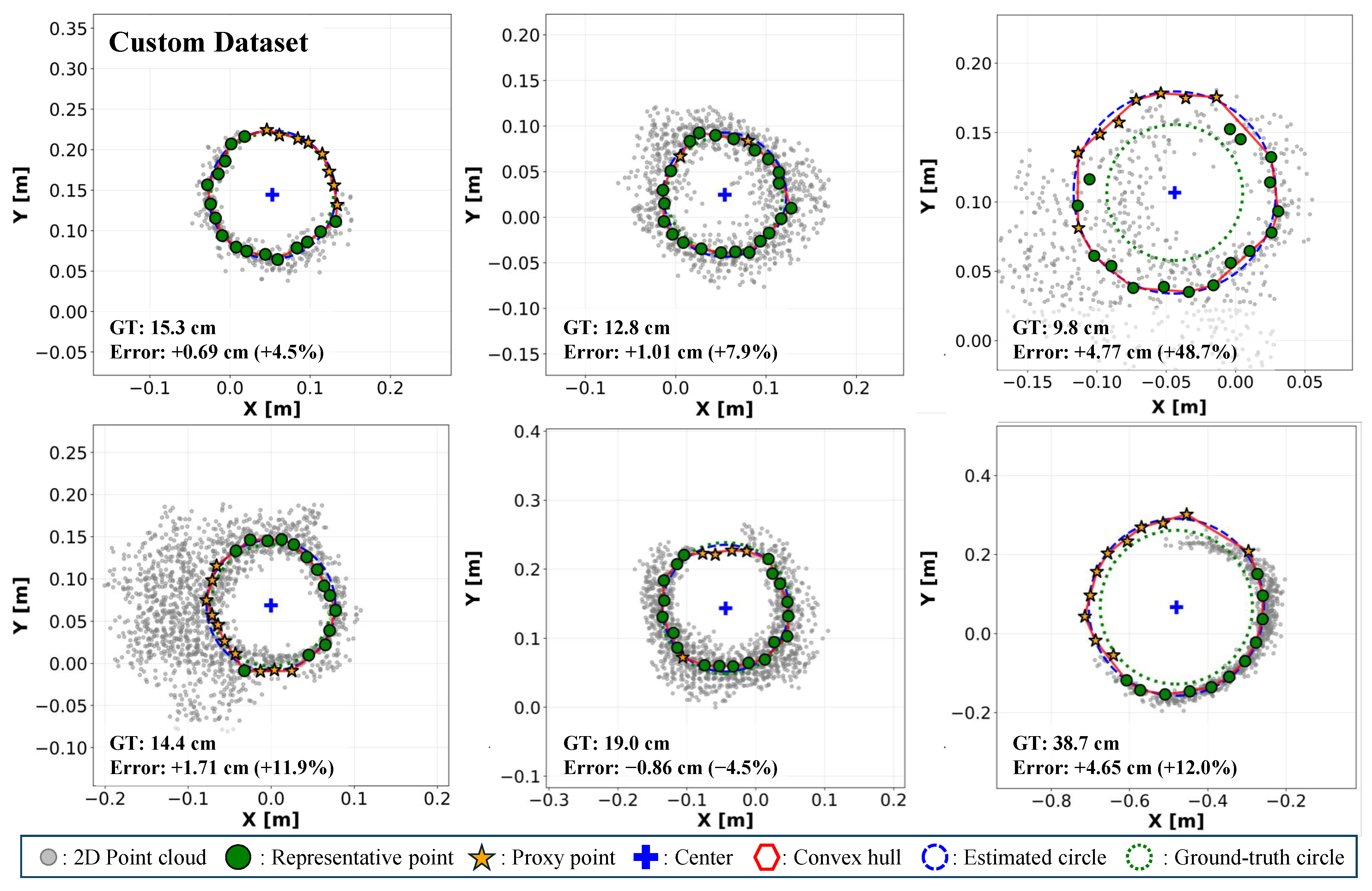

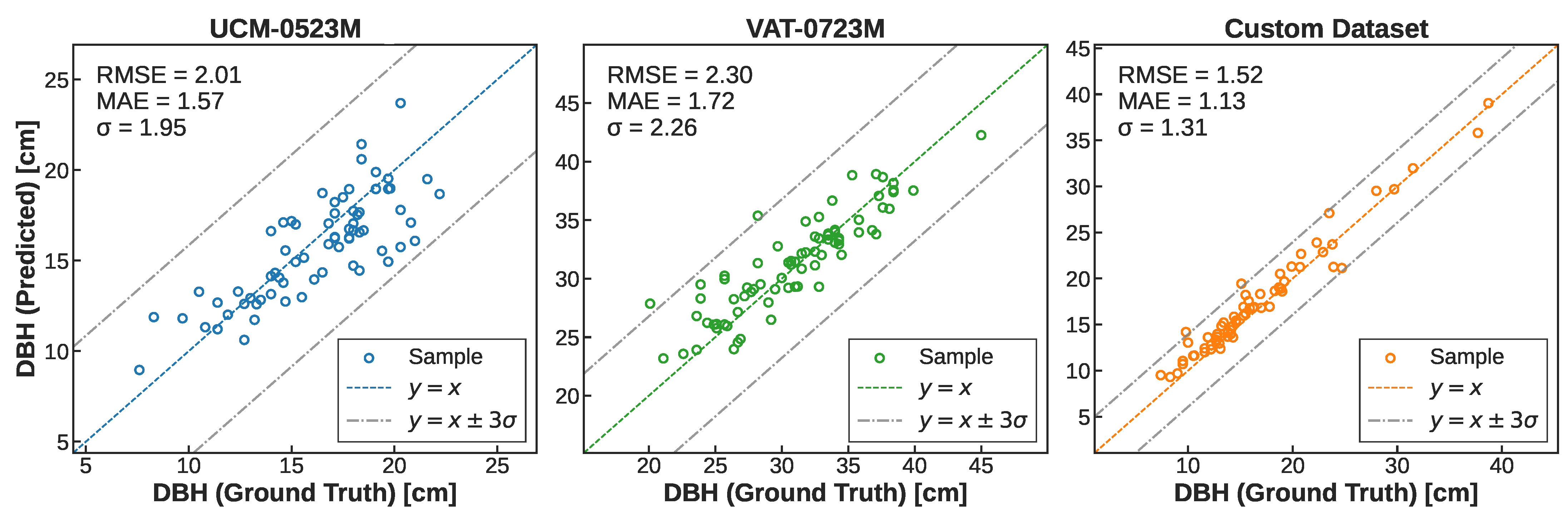

3.1. DBH Estimation Accuracy on Benchmark Datasets

3.2. Comparison of Perimeter Reconstruction Models

3.3. Analysis of Key Parameter Configurations

3.4. Ablation Study: Impact of Individual Core Pipeline Components

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shao, T.; Qu, Y.; Du, J. A low-cost integrated sensor for measuring tree diameter at breast height (DBH). Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 199, 107140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lappi, J. A multivariate, nonparametric stem-curve prediction method. Can. J. For. Res. 2006, 36, 1017–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Kankare, V.; Yu, X.; Hyyppä, J.; Holopainen, M. Automated stem curve measurement using terrestrial laser scanning. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2013, 52, 1739–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalwar, O.P.; Hussin, Y.A.; Weir, M.J.; De Bie, C.; Karna, Y. Deriving forest plot inventory parameters using terrestrial laser scanning in the tropical rainforest of Malaysia. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2021, 42, 884–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, R.; Wu, D.; Zhou, R.; Fang, L.; Zheng, X.; Lou, X. Estimation of DBH at forest stand level based on multi-parameters and generalized regression neural network. Forests 2019, 10, 778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, D.U.; Yirdaw, E. Models for Predicting Tree Diameter at Breast Height from Over and Under Bark Diameter of Stump in Eucalyptus camaldulensis Plantations. Preprints 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, Z.; Lin, L.; Jin, S.; Xia, Y.; Ziggah, Y.Y. A reliable dbh estimation method using terrestrial lidar points through polar coordinate transformation and progressive outlier removal. Forests 2024, 15, 1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravaglia, J.; Fournier, R.A.; Bac, A.; Véga, C.; Côté, J.F.; Piboule, A.; Rémillard, U. Comparison of three algorithms to estimate tree stem diameter from terrestrial laser scanner data. Forests 2019, 10, 599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Wang, X.; Liu, Y.; Yin, X. Tree Diameter at Breast Height Extraction Based on Mobile Laser Scanning Point Cloud. Forests 2024, 15, 590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eliopoulos, N.J.; Shen, Y.; Nguyen, M.L.; Arora, V.; Zhang, Y.; Shao, G.; Woeste, K.; Lu, Y.H. Rapid tree diameter computation with terrestrial stereoscopic photogrammetry. J. For. 2020, 118, 355–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, K.; Yue, S.; Yin, B. DBH Extraction of Standing Trees Based on a Binocular Vision Method. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Instrumentation and Measurement Technology Conference (I2MTC), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 22–25 May 2023; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Q.; Kan, J. Automatic forest DBH measurement based on structure from motion photogrammetry. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Gan, X.; Zhou, Y.; Yuan, X. Estimation of Diameter at Breast Height in tropical forests based on Terrestrial Laser Scanning and shape diameter function. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Pan, S.; Zhang, H.; Li, P. Trunk model establishment and parameter estimation for a single tree using multistation terrestrial laser scanning. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 102263–102277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Zhang, A.; Xiao, S.; Hu, S.; He, N.; Pang, H.; Zhang, X.; Yang, S. Single tree segmentation and diameter at breast height estimation with mobile LiDAR. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 24314–24325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Wang, J.; Dong, P.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Z. Estimating individual tree height and diameter at breast height (DBH) from terrestrial laser scanning (TLS) data at plot level. Forests 2018, 9, 398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.; Wang, J.; Li, H.; Hu, J.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, X.; Liu, X.; Wang, W.; Zhang, W.; Wu, S.; et al. Tree parameter extraction method based on new remote sensing technology and terrestrial laser scanning technology. Big Data Res. 2024, 36, 100460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guenther, M.; Heenkenda, M.K.; Morris, D.; Leblon, B. Tree Diameter at Breast Height (DBH) Estimation Using an iPad Pro LiDAR Scanner: A Case Study in Boreal Forests, Ontario, Canada. Forests 2024, 15, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Gan, X.; Zhang, Q.; Bu, G.; Li, L.; Xu, X.; Li, Y.; Liu, Z.; Xiao, X. Analysis of parameters for the accurate and fast estimation of tree diameter at breast height based on simulated point cloud. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 2707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USDA Forest Service. Forest Inventory and Analysis National Core Field Guide Volume I: Field Data Collection Procedures for Phase 2 Plots, Version 7.0; USDA Forest Service: Arlington, VA, USA, 2011; p. 114.

- Cheng, D.; Cladera, F.; Prabhu, A.; Liu, X.; Zhu, A.; Green, P.C.; Ehsani, R.; Chaudhari, P.; Kumar, V. Treescope: An agricultural robotics dataset for lidar-based mapping of trees in forests and orchards. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Yokohama, Japan, 13–17 May 2024; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 14860–14866. [Google Scholar]

- Henning, J.G.; Radtke, P.J. Detailed stem measurements of standing trees from ground-based scanning lidar. For. Sci. 2006, 52, 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabhu, A.; Liu, X.; Spasojevic, I.; Wu, Y.; Shao, Y.; Ong, D.; Lei, J.; Green, P.C.; Chaudhari, P.; Kumar, V. UAVs for forestry: Metric-semantic mapping and diameter estimation with autonomous aerial robots. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2024, 208, 111050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putra, B.T.W.; Ramadhani, N.J.; Soedibyo, D.W.; Marhaenanto, B.; Indarto, I.; Yualianto, Y. The use of computer vision to estimate tree diameter and circumference in homogeneous and production forests using a non-contact method. For. Sci. Technol. 2021, 17, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinkham, W.T.; Swayze, N.C.; Hoffman, C.M.; Lad, L.E.; Battaglia, M.A. Modeling the missing DBHs: Influence of model form on UAV DBH characterization. Forests 2022, 13, 2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumnall, M.J.; Raigosa-Garcia, I.; Carter, D.R.; Albaugh, T.J.; Campoe, O.C.; Rubilar, R.A.; Alexander, B.; Cohrs, C.W.; Cook, R.L. Assessing Methods to Measure Stem Diameter at Breast Height with High Pulse Density Helicopter Laser Scanning. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.; Duan, G.; Ye, Q.; Meng, X.; Luo, P.; Sharma, R.P.; Sun, H.; Wang, G.; Liu, Q. Prediction of individual tree diameter using a nonlinear mixed-effects modeling approach and airborne LiDAR data. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paris, C.; Bruzzone, L. A growth-model-driven technique for tree stem diameter estimation by using airborne LiDAR data. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2018, 57, 76–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proudman, A.; Ramezani, M.; Fallon, M. Online estimation of diameter at breast height (DBH) of forest trees using a handheld LiDAR. In Proceedings of the 2021 European Conference on Mobile Robots (ECMR), Bonn, Germany, 31 August–3 September 2021; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, X.; Litkey, P.; Hyyppa, J.; Kaartinen, H.; Vastaranta, M.; Holopainen, M. Automatic stem mapping using single-scan terrestrial laser scanning. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2011, 50, 661–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Włoch, W.; Iqbal, M.; Jura-Morawiec, J. Calculating the growth of vascular cambium in woody plants as the cylindrical surface. Bot. Rev. 2023, 89, 237–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Jordan, M.I. On convergence properties of the EM algorithm for Gaussian mixtures. Neural Comput. 1996, 8, 129–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, C.B.; Dobkin, D.P.; Huhdanpaa, H. The quickhull algorithm for convex hulls. ACM Trans. Math. Softw. 1996, 22, 469–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eilers, P.H.; Marx, B.D. Flexible smoothing with B-splines and penalties. Stat. Sci. 1996, 11, 89–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Nemiroff, R.; Lopez, B.T. Direct lidar-inertial odometry: Lightweight lio with continuous-time motion correction. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE international conference on robotics and automation (ICRA), London, UK, 29 May–2 June 2023; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2023; pp. 3983–3989. [Google Scholar]

- Se, S.; Brady, M. Ground plane estimation, error analysis and applications. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2002, 39, 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.Y.; Park, J.; Koltun, V. Open3D: A modern library for 3D data processing. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1801.09847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, D.R. Simple taper: Taper equations for the field forester. In Proceedings of the 20th Central Hardwood Forest Conference, Columbia, MO, USA, 28 March 28–1 April 2016; General Technical Report NRS-P-167. US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Northern Research Station: Newtown Square, PA, USA, 2017; pp. 265–278. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Singh, S. LOAM: Lidar odometry and mapping in real-time. Robot. Sci. Syst. 2014, 2, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Shan, T.; Englot, B.; Meyers, D.; Wang, W.; Ratti, C.; Rus, D. Lio-sam: Tightly-coupled lidar inertial odometry via smoothing and mapping. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/RSJ international conference on intelligent robots and systems (IROS), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 24 October 2020–24 January 2021; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 5135–5142. [Google Scholar]

- Belton, D.; Moncrieff, S.; Chapman, J. Processing tree point clouds using Gaussian Mixture Models. ISPRS Ann. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2013, 2, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Zone | Count | DBH (cm) | Perimeter (cm) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Std | Min | Max | Mean | Std | Min | Max | |||

| 1 | 24 | 14.5 | 2.8 | 9.8 | 20.8 | 45.1 | 7.1 | 30.6 | 65.5 | |

| 2 | 12 | 12.7 | 3.5 | 7.4 | 19.0 | 40.7 | 11.0 | 23.2 | 59.6 | |

| 3 | 6 | 20.4 | 3.4 | 15.3 | 23.8 | 62.4 | 11.8 | 48.0 | 74.9 | |

| 4 | 10 | 21.1 | 4.8 | 15.5 | 29.7 | 69.0 | 14.4 | 48.7 | 93.4 | |

| 5 | 5 | 35.0 | 5.1 | 28.0 | 38.9 | 109.9 | 16.8 | 87.8 | 122.9 | |

| 6 | 7 | 11.6 | 3.1 | 8.3 | 17.0 | 37.9 | 10.4 | 25.9 | 53.1 | |

| Dataset | N | DBH (cm) | Method | RMSE (cm) | RMSE (%) | MAE (cm) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Min | Max | ||||||

| UCM-0523M | 70 | 16.30 | 7.60 | 22.20 | DBCRE [21] | 2.60 | 16.00 | 2.23 |

| Ours * | 2.01 | 9.76 | 1.57 | |||||

| VAT-0723M | 76 | 30.80 | 20.10 | 45.00 | DBCRE [21] | 3.50 | 11.60 | 2.92 |

| Ours * | 2.30 | 5.97 | 1.72 | |||||

| Custom Dataset | 64 | 13.64 | 7.40 | 38.70 | DBCRE [21] | 2.16 | 13.32 | 1.88 |

| Ours * | 1.52 | 4.73 | 1.13 | |||||

| Dataset | N | Method | RMSE (cm) | RMSE (%) | MAE (cm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UCM-0523M | 70 | Convex hull | 2.01 | 9.76 | 1.57 |

| B-spline | 1.98 | 11.9 | 1.55 | ||

| VAT-0723M | 76 | Convex hull | 2.30 | 5.97 | 1.72 |

| B-spline | 2.48 | 14.6 | 1.92 | ||

| Custom Dataset | 64 | Convex hull | 1.52 | 4.73 | 1.13 |

| B-spline | 2.73 | 9.8 | 1.66 |

| Parameter | Setting | UCM-0523M | VAT-0723M | Custom Dataset | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RMSE (cm) | RMSE (%) | MAE (cm) | RMSE (cm) | RMSE (%) | MAE (cm) | RMSE (cm) | RMSE (%) | MAE (cm) | ||||

| aSectors m | 20 | 2.20 | 11.2 | 1.66 | 2.19 | 12.8 | 1.73 | 2.02 | 8.9 | 1.29 | ||

| 24 | 2.01 | 9.76 | 1.57 | 2.30 | 5.97 | 1.72 | 1.52 | 4.73 | 1.13 | |||

| 28 | 2.06 | 11.5 | 1.54 | 2.62 | 15.1 | 1.98 | 1.84 | 9.2 | 1.26 | |||

| bGMM comps. K | 3 | 2.25 | 12.1 | 1.69 | 3.04 | 16.8 | 2.18 | 1.95 | 9.5 | 1.40 | ||

| 5 | 2.01 | 9.76 | 1.57 | 2.30 | 5.97 | 1.72 | 1.52 | 4.73 | 1.13 | |||

| 7 | 2.12 | 11.3 | 1.61 | 2.35 | 13.5 | 1.82 | 1.65 | 7.2 | 1.09 | |||

| cB-spline degree db | 3 | 2.02 | 12.4 | 1.54 | 2.65 | 15.8 | 1.99 | 2.07 | 10.2 | 1.39 | ||

| 4 | 1.98 | 11.9 | 1.55 | 2.48 | 14.6 | 1.92 | 2.73 | 9.8 | 1.66 | |||

| 5 | 2.16 | 12.1 | 1.64 | 2.33 | 14.2 | 1.81 | 2.31 | 10.1 | 1.49 | |||

| Dataset | GMM | Consistency Filter | Proxy | RMSE (cm) | RMSE (%) | MAE (cm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UCM-0523M | – | – | – | 2.72 | 13.07 | 2.01 |

| ✓ | – | – | 2.69 | 13.54 | 2.14 | |

| – | ✓ | – | 2.40 | 11.82 | 1.82 | |

| – | – | ✓ | 2.66 | 13.72 | 2.07 | |

| ✓ | ✓ | – | 2.36 | 11.93 | 1.90 | |

| ✓ | – | ✓ | 2.15 | 10.30 | 1.65 | |

| – | ✓ | ✓ | 2.04 | 11.06 | 1.65 | |

| ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 2.01 | 9.76 | 1.57 | |

| VAT-0723M | – | – | – | 8.38 | 18.78 | 5.39 |

| ✓ | – | – | 4.86 | 11.87 | 3.47 | |

| – | ✓ | – | 2.36 | 6.85 | 1.97 | |

| – | – | ✓ | 8.49 | 19.80 | 5.55 | |

| ✓ | ✓ | – | 2.57 | 6.35 | 1.96 | |

| ✓ | – | ✓ | 5.15 | 12.22 | 3.56 | |

| – | ✓ | ✓ | 2.83 | 8.39 | 2.38 | |

| ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 2.30 | 5.97 | 1.72 | |

| Custom Dataset | – | – | – | 1.99 | 11.37 | 1.56 |

| ✓ | – | – | 1.74 | 7.32 | 1.17 | |

| – | ✓ | – | 2.58 | 12.14 | 1.82 | |

| – | – | ✓ | 3.09 | 15.83 | 2.31 | |

| ✓ | ✓ | – | 1.93 | 8.00 | 1.26 | |

| ✓ | – | ✓ | 1.79 | 9.28 | 1.33 | |

| – | ✓ | ✓ | 3.19 | 15.53 | 2.28 | |

| ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 1.52 | 4.73 | 1.13 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, W.; Son, H.-S.; An, S.-Y. Sector-Based Perimeter Reconstruction for Tree Diameter Estimation Using 3D LiDAR Point Clouds. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 2880. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17162880

Kim W, Son H-S, An S-Y. Sector-Based Perimeter Reconstruction for Tree Diameter Estimation Using 3D LiDAR Point Clouds. Remote Sensing. 2025; 17(16):2880. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17162880

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Wonjune, Hyun-Sik Son, and Su-Yong An. 2025. "Sector-Based Perimeter Reconstruction for Tree Diameter Estimation Using 3D LiDAR Point Clouds" Remote Sensing 17, no. 16: 2880. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17162880

APA StyleKim, W., Son, H.-S., & An, S.-Y. (2025). Sector-Based Perimeter Reconstruction for Tree Diameter Estimation Using 3D LiDAR Point Clouds. Remote Sensing, 17(16), 2880. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17162880