1. Introduction

With the widespread use of smartphones, location-based services (LBS) have become widely available to the public [

1]. A location-based service provides various information based on the location of a moving object, such as vehicle navigation using the Global Positioning System (GPS) and emergency route guidance applications for pedestrians. However, LBS can provide appropriate information only when the exact locations of pedestrians are identified. Therefore, localization technology is a core component of these services. Localization technology has been applied to various industries. Owing to the COVID-19 infectious disease that began in 2020, the localization of human positions has become increasingly crucial [

2]. An indoor localization system typically uses GPS-based location recognition. GPS-based localization is a method that involves the use of a satellite signal for calculating the location of an object. As most smartphones have a built-in GPS capability, this approach has the advantage of ease of use without any additional cost. However, if a pedestrian is indoors or in a densely populated area, satellite signals may not reach the space inside the building but instead be reflected [

3]. GPS cannot, therefore, be used indoors. Accordingly, there is an urgent need for research into accurate indoor pedestrian localization.

Indoor localization technologies may be divided into three categories. The first is an indoor localization technology based on wireless signals. Representative wireless communication technologies that employ wireless signals for indoor localization include Wi-Fi, Bluetooth, and Zigbee, which analyze transmitted signals and use received signal strength indicators (RSSI) through the trilateration, triangulation, and fingerprinting methods. When the mathematical formula or infrastructure used in a technique is well established, a high performance and a distance estimation error of less than 1 m are provided. Recently, research on indoor positioning using ultra-wide band (UWB) technology has been actively conducted to improve the performance of the time of arrival (TOA)-based approach in NLOS environments. This approach utilizes the time difference of arrival (TDOA) measurement between the UWB transmitters (anchors) and receivers (tags) to estimate the positions of tags. Multiple anchors and tags are used to measure the time differences between all devices, and the position of the tag is estimated based on this information. Alarifi [

4] proposed a UWB-based indoor positioning technology considering an industrial context. Two solutions based on UWB radio (Pozyx) and ultrasound (GoT) installed in an industrial manufacturing laboratory were compared and analyzed. The experiments were conducted in static and dynamic environments, and Pozyx showed a distance error performance within 40 cm, while GoT showed a performance within 20 cm. Yang [

5] introduced deep learning technology to address the problem of the degraded performance of UWB-based indoor positioning systems in NLOS environments. The input to the deep learning model is composed of 10 consecutive wireless signals’ RSSI and distance information measured from a single UWB anchor, which are used as a single sample for the model. The model was evaluated in various environments and showed a higher performance than the existing methods. However, various problems are related to the use of wireless signals. Owing to the characteristics of radio waves, wireless signals undergo irregular attenuation within their dynamic surroundings. Maintaining a high and consistent performance when using such attenuated wireless signals for positioning can be difficult.

The second method is image-based localization technology. In this approach, images are collected using a smartphone camera, a localization model is generated through deep learning, and images entering the input are analyzed to return the closest position coordinates. These techniques show a high localization performance in cases in which the learning data and infrastructure are well established, although performance degradation can occur depending on the environment [

2].

Another sensor-based localization technology is known as pedestrian dead reckoning (PDR). PDR involves the estimation of the next position of an object from the prior position based on data from the sensor. The PDR method may be divided into inertial navigation systems (INS) and step and heading systems (SHS). An INS is a system that estimates the entire 3D trajectory of a sensor at a specific moment and tracks its location. SHS is a system that estimates location by accumulating vectors that represent steps or stride lengths [

6]. INS is used to track objects, such as airplanes and missiles, and SHS is used to estimate pedestrian locations [

7]. The PDR employed in this study uses SHS.

SHS involves three steps: the number of steps detected, stride length estimation, and heading direction estimation. First, sensor data can be used to estimate the moving object’s distance by multiplying the number of steps and stride length, and the relative position of the pedestrian can be estimated by combining the estimated moving object distance and heading direction [

8]. The use of SHS with PDR has the advantage of being easily distributed, because it does not rely on infrastructure, and there are already sensors built into smartphones. A PDR-based indoor localization system that uses sensors built into smartphones offers the advantage of being very practical from the pedestrian’s perspective, as it does not require additional infrastructure or cost, unlike the conventional methods that use wireless signals or video data. Therefore, the PDR method is free from the effects of NLOS environments, walls, and obstacles, as it does not use wireless signals. This approach also works well under dark conditions, because it does not use visual data (i.e., camera or video data) when positioning [

9]. However, it is difficult to reflect the speed of moving pedestrians in real time, and various errors can occur depending on the posture of the pedestrian using a smartphone. To address these shortcomings, speed estimation using a deep learning method instead of a formula has been proposed. Deep learning reflects a pedestrian’s state in real time, because it can estimate both the posture of the pedestrian using a smartphone and the moving object distance. However, because there are restrictions, such as having to walk at a certain stride length when collecting data, a new method of estimating the final moving object distance using GPS speed estimation instead of the stride has emerged. This method alleviates the constraints of the existing deep learning techniques by using data collected while walking freely outdoors. However, a data collection time of at least 1 h and 20 min is required, which is impractical from a pedestrian perspective. Therefore, this study proposes a GPS-based PDR with a similar performance and a significantly lower data collection time, which focuses on practical moving pedestrian distance estimation. The contributions to the field of this study are as follows.

Improving practicality: transfer learning techniques are applied to achieve consistent high estimation performances, even in cases in which the moving object distance estimation model receives small amounts of data for new pedestrians (i.e., system users). The data collection time is significantly reduced to increase practicality.

Data imbalance: a new data augmentation method is applied to address the fact that most of the training data used for indoor localization with deep learning are concentrated on labels within a certain range. Moving object distance errors are reduced.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 introduces other studies related to indoor pedestrian localization technology.

Section 3 describes the problems addressed in this study.

Section 4 introduces the system proposed in this study, and

Section 5 describes the performance of the proposed system. Finally, a discussion of the results and their significance is presented in

Section 6.

3. Research Problem to Be Addressed

Conventional PDR methods that employ deep learning have achieved high moving object distance estimation performances. However, various constraints that may be considered impractical from a pedestrian perspective were applied, depending on the purpose of each study. This has led to the emergence of GPS-based PDR methods, which mitigate the constraints arising when collecting the data required for deep learning. For example, J. Kang et al. [

18] proposed a new technique for learning pedestrian walking patterns and estimating speeds indoors using the GPS coordinates and sensor data collected outdoors by smartphones. The walking speed of pedestrians calculated by GPS coordinates collected in real time was automatically set as a label for the deep learning model, and acceleration sensor data were used as the input data. This study addresses the problem of walking at a fixed speed when data collection is performed by estimating the moving object distance using the average speed of pedestrians. In this study, the performance of 60-m-long movement data is evaluated when data are collected over 14 h, and the results show high accuracy, with an error of approximately 1 m. However, the system user (pedestrian) must collect more than 14 h of data to achieve the above performance. Furthermore, to show a valid distance estimation error of approximately 3.4 m, the data must be collected for at least 1 h and 20 min. From a pedestrian perspective, an indoor localization system that requires such lengths of time for data collection is extremely impractical. In this study, we aim to reduce the data collection time while retaining a similar performance.

The size and quality of the training data affect the performance of the deep learning model, because it extracts features or patterns from the training dataset and learns to predict the outcome desired by pedestrians. Therefore, it is important to secure high-quality and appropriate data so that the deep learning model can extract the desired features or patterns from the input training data.

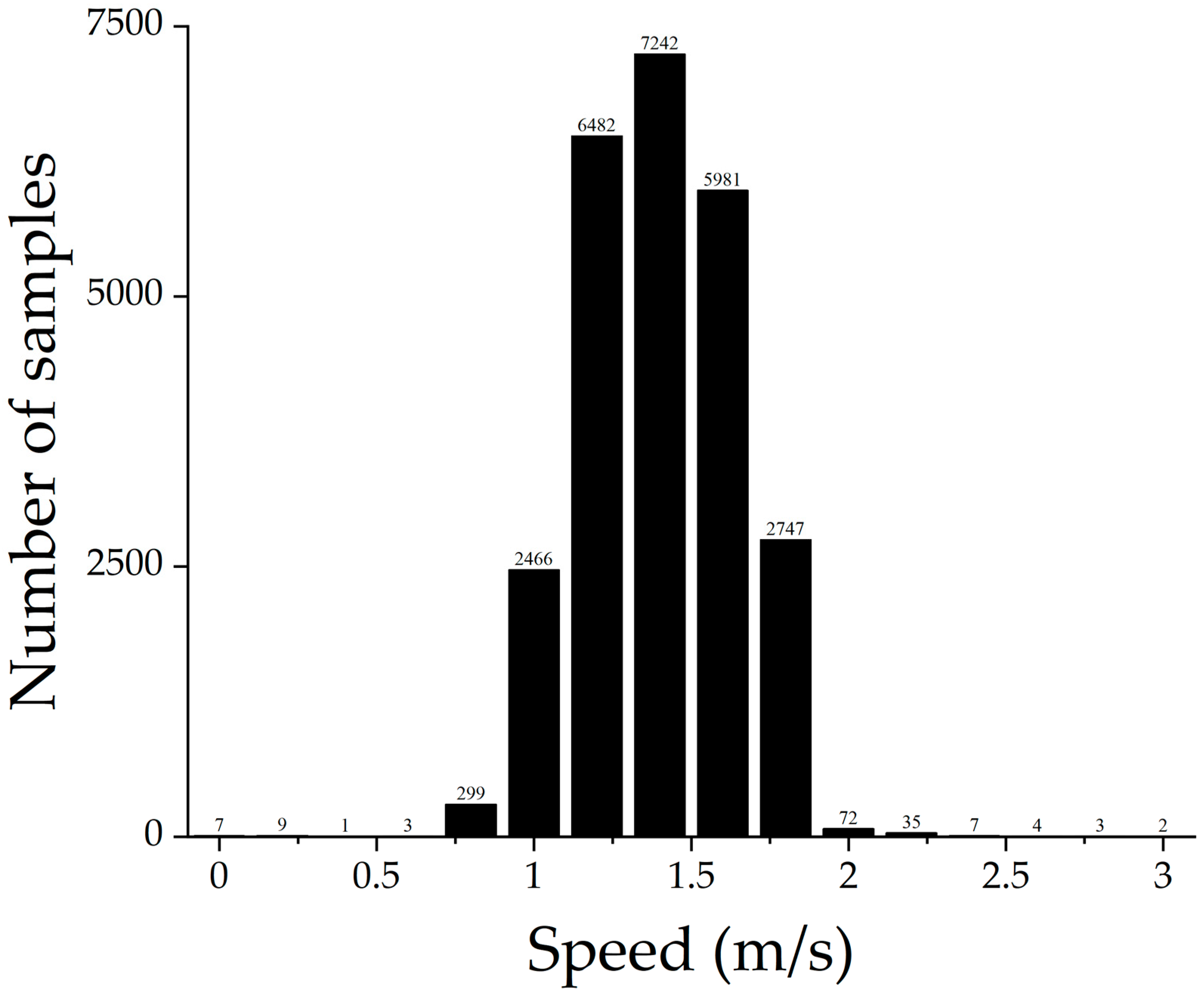

Figure 1 shows the

x-axis values of the acceleration sensor data collected in this study while walking outdoors for approximately 5 min as a distribution of the walking speed. At the time of data collection, the pedestrians in this study only walked at an average speed. Therefore, data collected for speeds between 1.2 and 1.6 m/s were the most common. The problem of imbalance during the data collection makes it difficult to provide a consistent performance, as, in this case, pedestrians cannot accurately estimate their speed if they walk too slowly or quickly, significantly impacting speed estimation systems using deep learning models. The second purpose of this study is to resolve this data imbalance.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Overview

Figure 2 shows an overview of the proposed pedestrian moving object distance estimation system. The part inside the red dotted line in

Figure 2 represents the data preprocessing process that is explained in detail in

Section 4.2. The proposed method consists of offline and online phases. First, data are collected for use in pretrained models. The data are the values for pedestrian speed obtained using the acceleration sensor and GPS coordinates collected outdoors. The collected data are used as a training dataset, employed when learning a pretrained model. After collecting the sensor data to estimate the speed in the same way, a data preprocessing stage consisting of data augmentation techniques and oversampling techniques is performed. Finally, weights are obtained from the pretrained model and applied to the transfer learning model, and the training data that have undergone preprocessing are then learned. When the learned transfer learning model receives minimal data from a new pedestrian, it is possible to learn and estimate the moving object distance. These methods are described in detail in the following sections.

4.2. Data Preprocessing

The data used in the proposed pedestrian moving object distance estimation system consist of acceleration sensor data and the speeds of pedestrians obtained by calculating their GPS coordinates. In this case, the acceleration data are collected at a sampling rate of 100 Hz, and the speed is collected at a sampling rate of 1 Hz. In this study, GPS was used to gain the objects’ moving speed, which is used as a label for the deep learning model. The reason for calculating the moving speed through GPS coordinates, not mathematical formulas or models that convert acceleration values to speed, is that it is relatively easy and accurate to obtain [

19]. In particular, there is no significant difference between walking outdoors and walking indoors, so we collect data outdoors where we can receive the GPS signals and construct a training dataset. Pedestrians collect data freely, without any restriction on their speed, and Kalman filters are applied to sensor data to reduce cumulative sensor errors. The orientation and position of a smartphone affect the collected sensor data values. Therefore, a preprocessing step is required to ensure that the same values are collected, regardless of the orientation and location of the smartphone. To collect sensor data at a constant value, regardless of the placement state of the smartphone, the device-oriented coordinate system is converted into an Earth-oriented coordinate system by multiplying the accelerometer value by the rotation matrix. As the Earth-oriented coordinate system has the same value regardless of the orientation of the screen, it is possible to collect constant data regardless of the direction of the smartphone [

20].

The moving speeds of pedestrians obtained using GPS coordinates vary widely. If the deep learning model is labeled with the speed of movement calculated by GPS coordinates, the number of labels will be very high, and accordingly, there will be more data to be learned per label. Therefore, in this study, we label a speed class within a certain range as pretrained and transfer learning models. To determine the appropriate number of speed classes (i.e., the number of labels), repeated experiments are conducted.

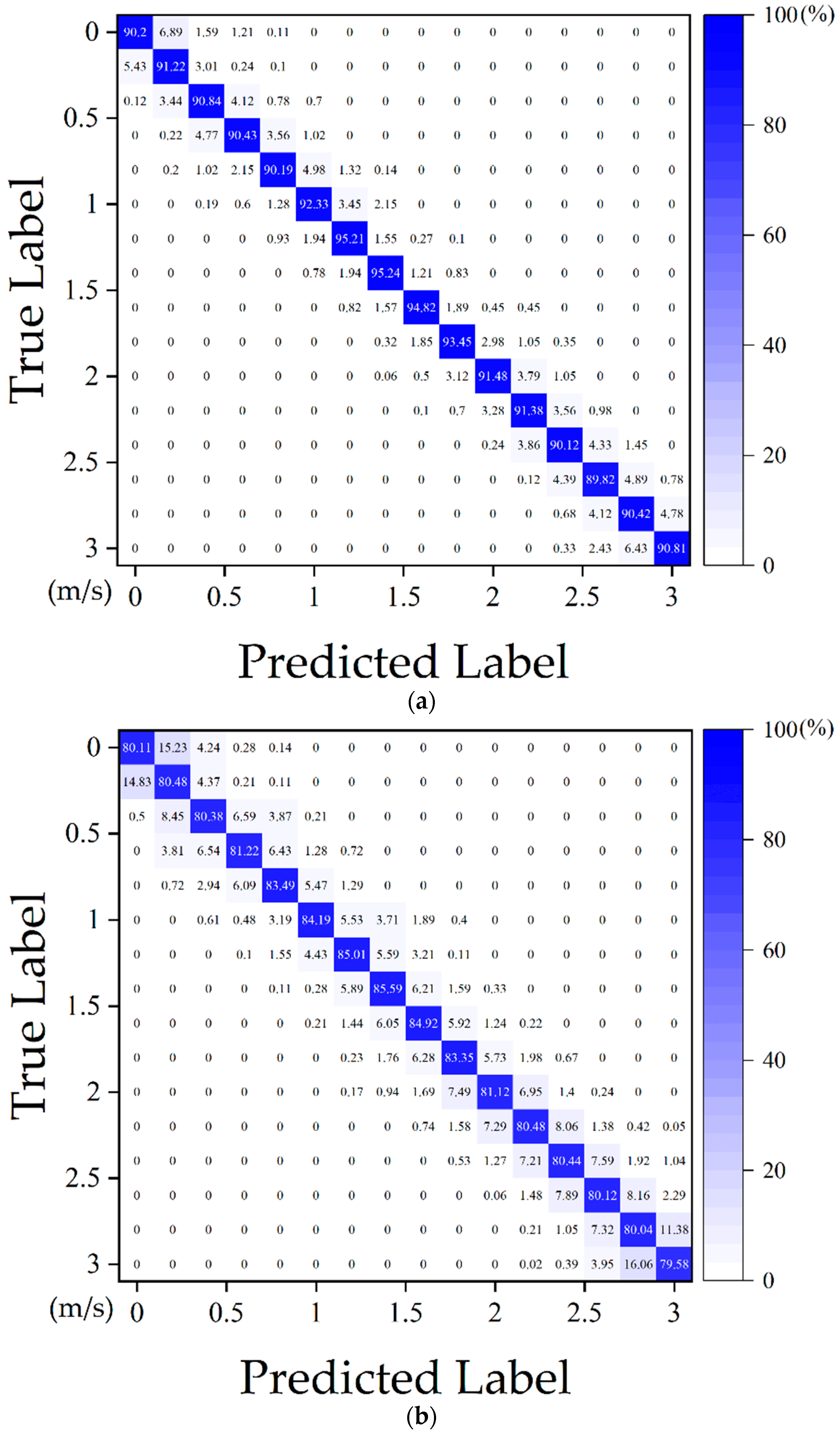

Table 1 lists the results of the experiment to determine the optimal number of classes. Experiments show the results of the moving distance estimation for indoor 60-m-long paths after training a set of approximately 58 h of training data collected outdoors on a CNN model, which is a pretrained model. The greater the number of classes, the lower the accuracy of the CNN pretrained model speed estimation, although the distance error gradually decreases. Since the proposed moving distance estimation system is required to estimate the pedestrian moving object distance, this study focuses on errors in the estimated moving object distances obtained using a deep learning model. Based on the experimental results, the optimal number of classes is set to 16.

Figure 1 shows the data collected outdoors. Almost all the data are distributed between approximately 1.2 and 1.6 m/s. The phenomenon of uneven data collection also occurs when subjects walk for a short time. If such unbalanced data are used for learning in this type of deep learning model, maintaining a consistent performance is difficult. In other words, deep learning models show a high estimation performance for data collected by pedestrians walking at average speeds; however, they cannot estimate accurate speeds for data collected by subjects walking quickly or slowly. This data imbalance affects the model performance; therefore, it is necessary to apply data augmentation methods to obtain sufficient data at all speeds.

Methods for augmenting time-series data include window warping [

21] and scaling [

22]. Window warping is a method for changing the

x-axis of the data by increasing or decreasing the interval based on the time axis. Scaling is a method that involves changing the scale of the

y-axis by multiplying it by an arbitrary scalar. In this study, two data augmentation methods were fused to create new data augmentation techniques.

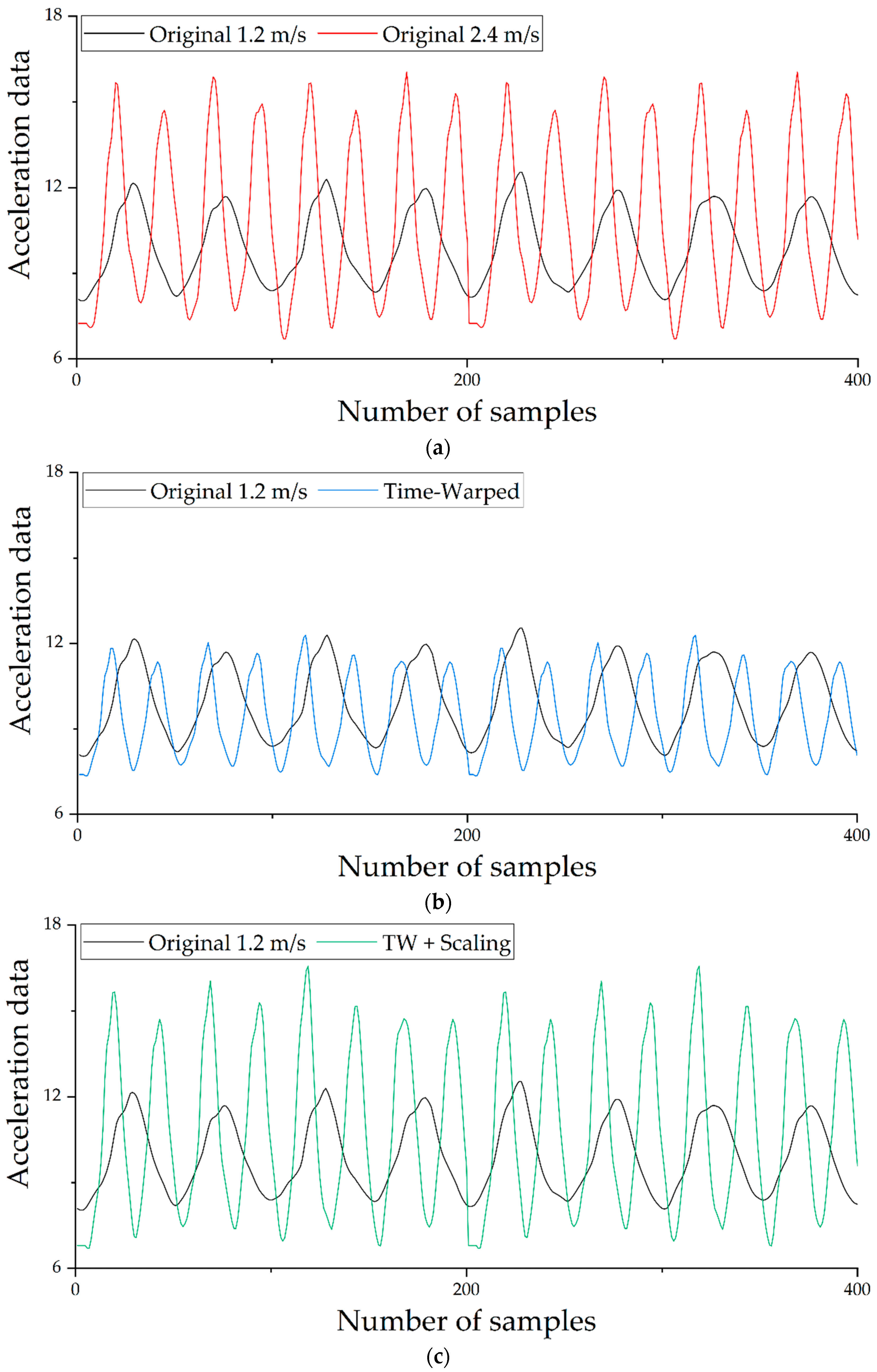

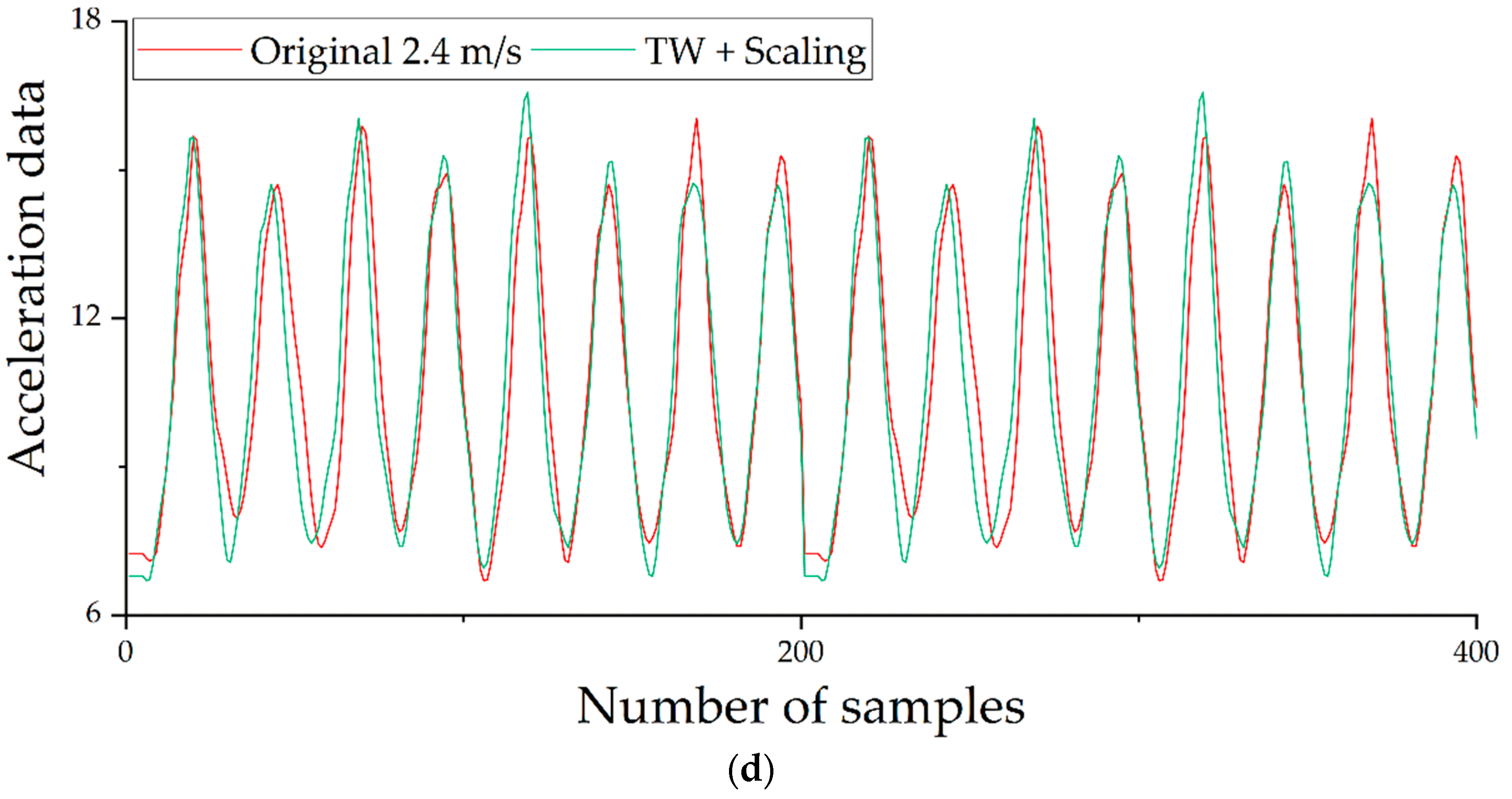

Figure 3 shows the processing of 1.2 m/s acceleration data for approximately 4 s to provide 2.4 m/s acceleration data.

Figure 3a shows acceleration data actually collected at speeds of 1.2 and 2.4 m/s.

Figure 3b shows the results obtained from processing the original 1.2 m/s data using a window warping technique.

Figure 3c shows the results obtained by multiplying the

y-axis of the warped data in

Figure 3b by an arbitrary scalar value.

Figure 3d shows a graph comparing the final augmented data with the data collected at the actual speed of 2.4 m/s.

The sensor data used to estimate the actual moving object distances are collected similarly, as these are employed in the data collection method described in

Section 4.2. The amount of data is increased by applying the data augmentation technique proposed in this study. SMOTE [

23] is subsequently used among the oversampling techniques to match the numbers of all classes equally and apply these as learning data.

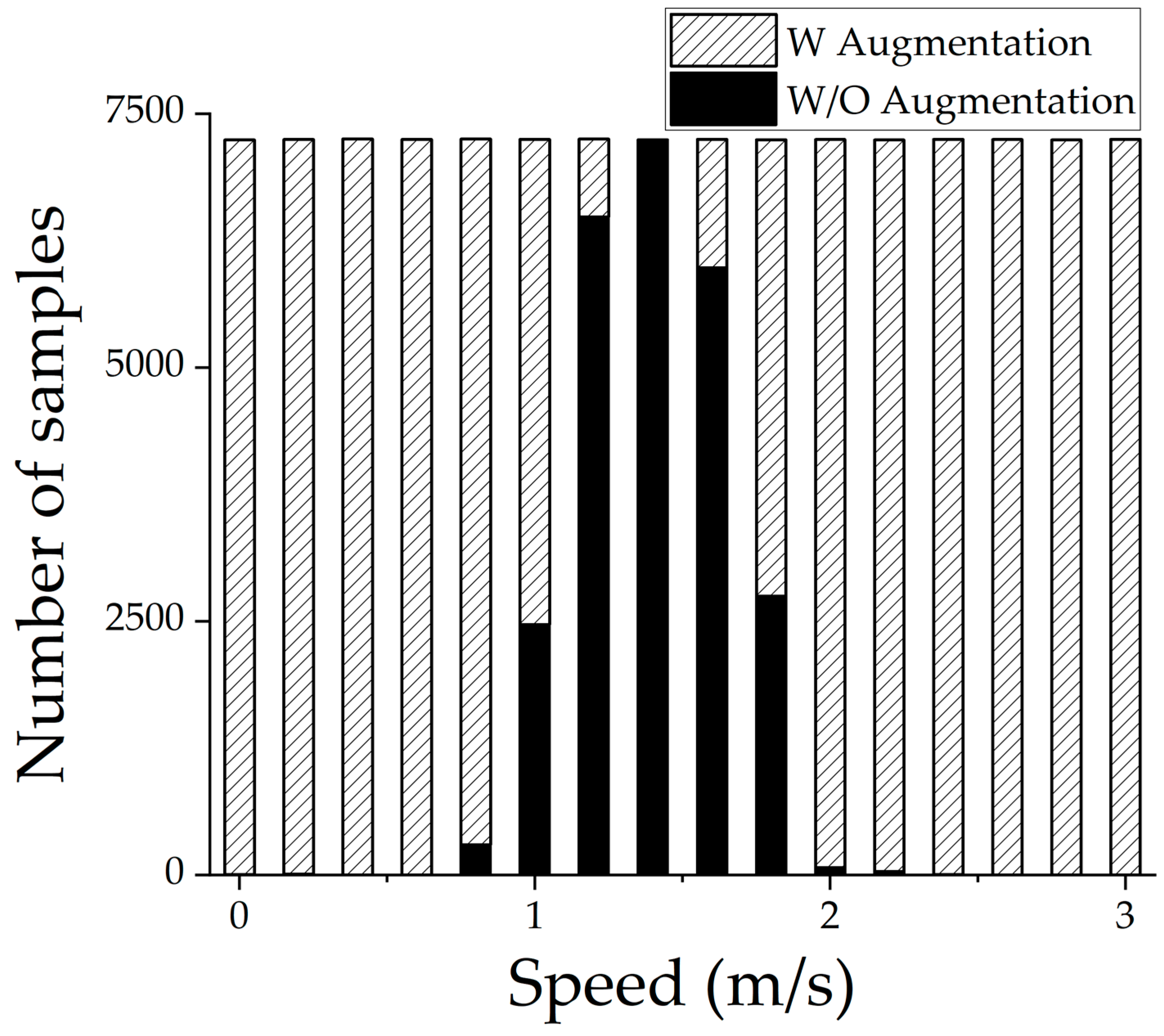

Figure 4 shows the results of augmenting the 15-min-long outdoor data mentioned in

Section 4 using the proposed preprocessing method.

4.3. Pretraining

Deep learning is extremely effective for classifying image data, because machines can automatically extract and learn features from data. However, this approach has recently been proven effective not only for image data but also for time-series data classification [

24]. Representative CNN models that perform well in classification include AlexNet, GoogleNet, ResNet, and DenseNet. Among these, AlexNet [

25] has performed well in various fields since it won the 2012 ImageNet competition. This study employs AlexNet, an effective deep learning model for the current time-series data classification problem [

26]. The structure of AlexNet is not unchanged in this study but instead modified to fit the data. Since there is a small set of input data, the padding for the consistent sizing of each data segment is set to the same value, and the filter size to extract features from the input data is changed. In addition, to prevent overfitting, some fully connected layers are removed, thereby reducing the number of parameters learned and using dropout. Batch normalization allows for experimentally fast and stable learning, although this is eliminated in this study, because it degrades the performance.

4.4. Transfer Learning

Deep learning has been applied to various fields and learns by extracting features from large amounts of data. However, there are two problems related to selecting the data used for deep learning. The first issue is that of data dependency. A large amount of data is required to accurately extract the desired features from the training data, therefore creating a high level of dependence on the size of the dataset. Second, data collection is time-consuming and expensive, making it very difficult to build large, high-quality datasets, depending on the data characteristics [

27]. Transfer learning has recently been proposed to solve these problems. The transfer learning method is based on the idea that applying previously learned knowledge can solve new but similar problems faster or with better solutions [

28]. For example, to address the problem of a lack of unstructured data, such as text, in the policy field, one study [

29] improved the accuracy by approximately 10% while reducing the learning time through transfer learning. In another study [

30], the problem of a lack of learning data resulting from difficulties related to data collection and labeling was addressed by transition learning, using pretrained models in medical image classification. The transfer learning method is generally useful for small training data and fast to learn with a pretrained model. As mentioned above, a pretrained model is required to perform transfer learning. A pretrained model refers to a model similar to the data of the problem to be solved that has already learned from a sufficient quantity of data. Pretrained models that are widely used in the image domain include AlexNet, ResNet, GoogleNet, and VGGNet. However, for time-series data, the user must create their own pretrained model. As such, transfer learning is a useful technique in terms of the generalization of deep learning models. With only a sufficiently learned pretrained model, system users can guarantee a high performance with relatively little training data.

There are two types of transfer learning methods: fixed feature extractors and fine-tuning. CNNs are largely composed of convolutional layers and classifiers, and techniques are divided into those that relearn classifiers or relearn parts of the convolutional layers. Fixed feature extraction removes only the last layer of the classifier from the pretrained model, freezing the weights of the remaining layers, and then relearns and performs classification by adding a classifier for the new dataset to be solved. This technique is used when a new dataset is highly similar to the data written on the pretrained model and where there are few data [

31]. Fine-tuning is a technique in which the weights of the desired layers are frozen in the pretrained model layer and the remaining layers are relearned with the newly added layers. This technique is often used for large amounts of data or where there is little similarity to the data written in the pretrained model and there is a risk of overfitting if the layer to be retrained is incorrectly set. In this case, therefore, the freezing range should be appropriately adjusted.

CNN models accumulate weight as they learn. Weight is a parameter that controls the importance of the effect of each input datum on the output. CNN models learn in a direction that classifies pedestrian speed well while continuing to pass weight to the next layer. The learned model can be stored, recalled, and relearned. In this study, a pretrained model pre-learns an approximately 58-h-long training dataset. For transfer learning, the weights of the pretrained model are loaded. At this time, the transfer learning model does not relearn all layers, instead relearning only a part of them. Transfer learning is divided according to the similarity between the data used in the pretrained model and the pedestrian data used for transfer learning and the amount of pedestrian data. This study determined that the data used in the pretrained model and the pedestrian data are highly similar. This is because these are acceleration sensor data that contain pedestrian gait information. However, owing to the very small quantity of pedestrian data, the proposed method involves relearning only up to the second convolutional layer through experiments.

4.5. Moving Distance Estimation

After transfer learning, the pedestrian acceleration data are input, and the pedestrian speed is estimated. Since the proposed model uses the SoftMax function as a classifier, the estimated speed is a probability value for each class, not the actual value. However, because the actual speed value is required, a process for changing the probability value is necessary. Before estimating the moving distance, this is changed to the average value of the speed range for each class. Finally, the pedestrian speed estimated by the model is obtained as the moving object distance of the pedestrian using Equation (1).

where

is the total moving distance of the pedestrian, and

is the estimated speed of the pedestrian with respect to time,

.

4.6. Scenario

The purpose of the moving object distance estimation system proposed in this study is practicality. Pedestrians can construct a personal moving distance estimation system in a very short time exclusively for themselves simply by walking outdoors while using a smartphone. The virtual scenarios for constructing pedestrian-individual systems are as follows.

Accelerometers and GPS data will be collected when pedestrians go outdoors, because GPS signals can be received only outdoors. The accelerometer data collected is converted into an Earth-oriented coordinate system, so pedestrians can place their smartphones anywhere on their bodies. Afterward, when pedestrians enter the indoors from the outdoors and cannot receive GPS signals, data collection is temporarily stopped, but the data collected until then are stored in their smartphones. The collected data goes through data preprocessing so that it can represent the characteristics (i.e., classes) of other moving speeds, except those calculated by GPS coordinates, before being stored on a smartphone. Through this process, construct a balanced training dataset and repeat the data collection for a time of about 15 min. After completing the data collection and preprocessing and completing the construction of a 15-min training dataset, the transfer learning model is trained by inputting the training dataset. At this time, the weight of the pretrained model, which has a sufficient moving speed estimation performance by learning 58 h of training data in the offline phase, is applied to the transfer learning model. After the learning is complete, the pedestrian then collects only accelerometer data to estimate his or her moving distance. The collected accelerometer data is input to the transfer learning model in which the learning is completed and used to calculate the moving distance.

6. Conclusions

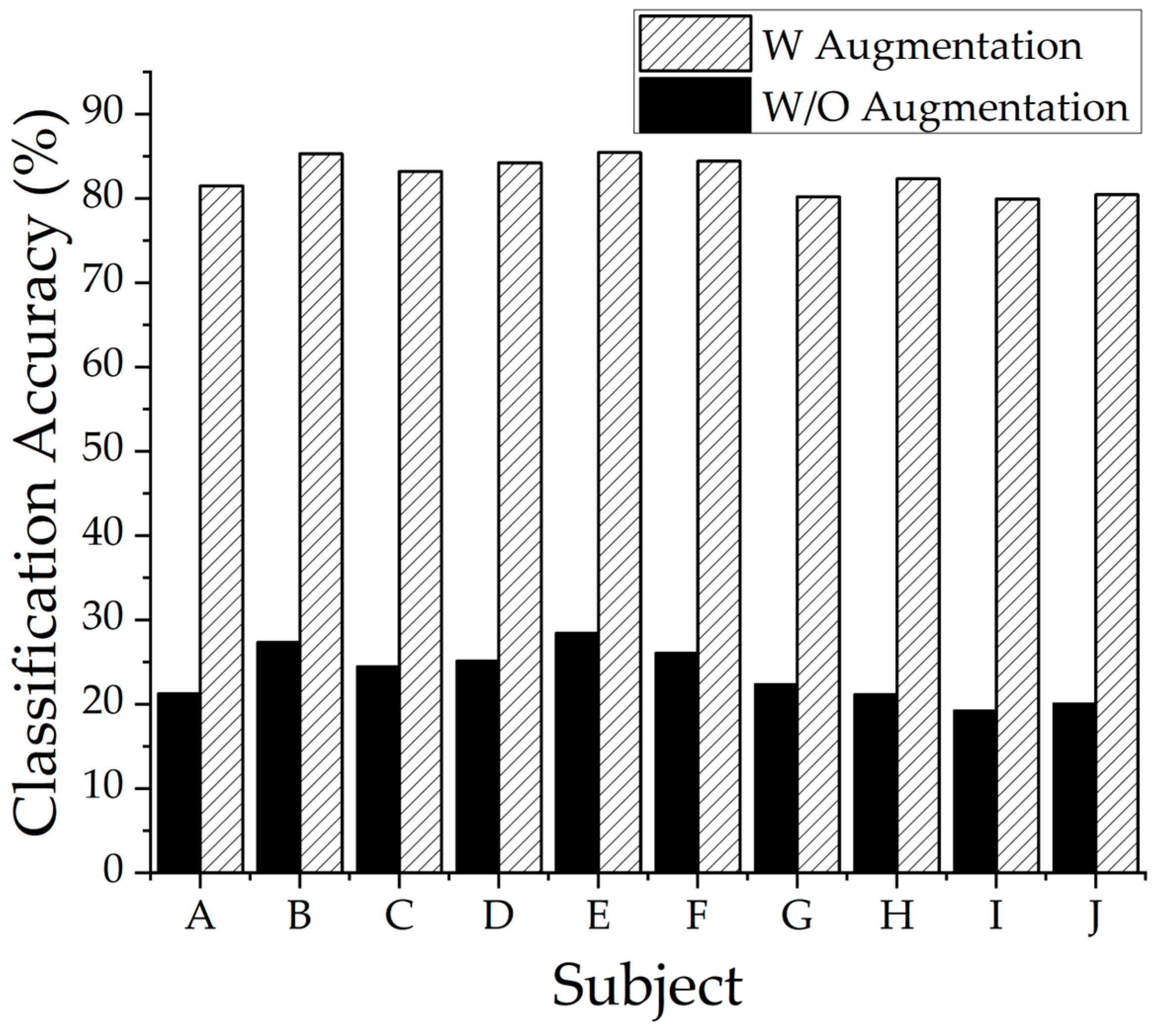

In this study, a new deep learning moving pedestrian distance estimation system is proposed to address the problems of the existing PDR systems. PDR systems that employ deep learning technology exhibit various advantages over other technologies that involve converting sensor data into gait information using mathematical formulas or models. However, a deep learning model requires a large training dataset to achieve a high estimation accuracy and can be impractical, because pedestrians need to collect sensor data directly. In addition, in this study, when the authors and study participants collected data outdoors, large amounts of data were collected at average walking speeds, and relatively limited data were collected at slow or fast moving speeds. This reflects the fact that humans usually walk at an average moving speed most of time much more often than slow or fast moving speeds. This problem of data imbalance makes it difficult for deep learning models to provide consistent performances at various pedestrian walking speeds. To solve this problem, this study proposes a transfer learning technique and a novel data augmentation method that provides a high performance with only a small amount of training data. The transfer learning model receives weight from a pretrained model that learns from a training dataset of approximately 58 h. The usefulness of the transfer learning technique is demonstrated, with a classification accuracy of approximately 83% for a 15-min-test dataset. In addition, to reflect the various pedestrian walking speeds, a range in which the amount of data is relatively insufficient is designated, and a data augmentation method for the corresponding part of the data is applied. Evaluating the data augmentation performance using a test dataset collected while pedestrians walk at various speeds increases the transfer learning model classification accuracy from 25% to 81%. Moreover, the transfer learning model, which employs weight from a pretrained model, shows a similar performance using a training dataset of approximately 17% of the size required by other speed estimation techniques. The limitations of the pedestrian moving object system proposed in this study are very clear. The size of the training dataset used to obtain the weight of the pretrained models that needs to be transferred to achieve a sufficient performance of the transfer learning model must be very large. It is not a concern for pedestrians who use the system, but it is very burdensome for researchers and developers who provide the system. The way of providing large-scale open-source data or appropriate data augmentation methods should be studied. Future research plans include further research into the proposed indoor localization system together with the introduction of a new technology for estimating the heading direction of pedestrians.