3. Result

The outcome of the project reemphasizes that the meaning of the building and associated collective memories are intrinsically embedded in the process through which the building was conceived, produced, and endured a series of socio-cultural changes [

25]. Hence, the history of our built heritage should be centered on the understanding of human experiences, history, and narratives through historic fabric, structures, and remains [

26]. Being in a telescopic distance, it is always difficult for present day users to be immersed in the past, embodying the memories and meaning of a building, without participating in the performance of rituals and social acts [

27]. Buildings of the past, with their very existence, are attached to collective memories of certain groups [

28]. Thus, architecture becomes the most tangible and durable object of remembrance, though it could be paradoxical and contested when it engages with collective memory [

29].

Virtual heritage has significant implications on non-invasive restoration and preservation of the monuments. It generally provides an immersive multimedia experience through a computer-simulated environment that can simulate physical presence in places in the real world [

30]. It further provides scope for an interdisciplinary research environment by developing a rich database of the digital assets for the conservators, historians, and archaeologists, to restore the historical sites, as well as heritage preservation. Although, for most of the cases, the 3D virtual models contain accurate data and help with restoration, whether they could capture the associated meanings and memories, especially the intangible values, are a big question for an architectural historian. Thus, the concept of building as “place” along with 3D articulation of the lost building comes in front. “Place” through the articulation of space has been at the concern of architectural theory and practice for the last few decades, and a widely discussed topic of architectural history and theory. Place can be understood in relation to space, though it is not created by mere three dimensionality of space. It is rather ‘about the practices and politics of place and identity formation—the slippery ways in which who we are becomes wrapped up with where we are.’ [

31]. While the assumption of ‘place’, in the context of this chapter, is a meaningful interaction to a space where the user, environment, and the memory ‘tell it’s past… [and] contains it like the lines of a hand’ [

32], the 3D model of architectural space generally addresses the metric expression of form, shape, and material physicality.

The discipline of history and theory of architecture traditionally focus on the aspects of visual culture best represented by the most advanced image reproduction technique of that time [

33]. Introduction of virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR) certainly transformed our capacity to understand structures and resolve issues of plausible historic design that no longer exist [

34]. With the incorporation of digital humanities into the mainstream research and dissemination process of architectural history, virtual imagery would certainly dominate the entire architectural realm. However, the question remains, to what degree (and how) virtual imagery should be used to convey meanings and memories, as well as interpret them correctly, particularly due to the heavy reliance and ocular-centric nature of these technologies. While these virtual realities may allow us to investigate and recreate the lost architecture, “…they are not likely to help us experience inhabiting that place, moving through that place, or understanding the dynamic and ever-changing relationship of people and place.” [

35]. The reason may be the overemphasis on the fidelity of the created objects and understanding of ocular engagement in fully understanding “place”. Imagery has always been considered as factual and is used to provide evidence in “… legal cases and in science, photographs operate within the modality of actuality. The photographs [the visual] are meant to allow us to discern what actually occurred” [

31]; however, it could be misleading if we put them in the wrong context. This is no different to evidence of the historical facts. Therefore, when utilizing visual technologies, such as VR and AR to portray architectural history, a place should be understood to its fullest within the context. We know that icons and symbols provide meaning to architectural form, and these meanings are the intangible aspects of the heritage. As Pallasmaa argued, “... technological culture has ordered and separated the senses... Vision and hearing are now the privileged sociable senses, whereas the other three are considered as archaic sensory remnants with a merely private function, and they are usually suppressed by the code of culture” [

36]. This suppression of other senses and the ocular facilities might provide a false sense of place by conveying a different meaning or sometimes creating a new one. By just creating an ocular narrative of a place through virtual and augmented realities, we could ultimately be removing the intangible feelings, emotions, and cultural memories attached to a space. Without the true encompassing narrative “…no matter how indexical, suitable, or numerous the representations of an object are, what is on the screen will always resolutely remain a representation that stands in for something else” [

33]. This re-production of a space becomes its own entity and “establishes their own versions of the past” [

37].

Hence, in this particular project, visual aspects of the reconstruction, i.e., photo realization, is considered as part of the narrative of the building. It is considered as just the beginning of disseminating heritage value and connecting the user rather than the end product. As discussed earlier, architectural heritage is something more than the physical form. A building is a place for doing different activities in and around. To understand the architecture of this monument, mere virtual reconstruction of the three-dimensional form would not be sufficient. In order to create a virtual environment embodying the essence of place is inevitable. Usually the role of “place” is a virtual environment as a locator of objects [

38]. Thus, the architectural heritage in the collective memory sits intrinsically at the intersection of multiple narratives as palimpsest. Hence, to recover the memories of this building, it is required to identify and examine these narratives along with the virtual modeling. The issue of ‘place’ becomes crucial while reconstructing the past with limited resources in hand, which are fragmentary and inconspicuous in nature. The temporal distance and the lack of understanding between photo realization of the actual architecture and creating an unbiased sense of place remains at the crux of the problem.

From that aspect, the digital narrative of the Bow Truss wool store building opened up new opportunities to the public, to communicate and interact with the state’s heritage significance. The same approach with the 3D model can also be applied to bring back other damaged, unbuilt, or demolished buildings. For future work, it is planned to scale up the project to use a case study research strategy and the content of Geelong’s wool industry heritage to empirically investigate how to communicate architectural buildings with different social values and collective memory (of renovated vs. demolished buildings) among the local community.

4. Discussion

As this particular project had limitations due to the Corona Virus Pandemic (COVID-19) situation, in terms of budget and accessibility, initial aims and objectives were amended later to frame it within the capacity of the project team.

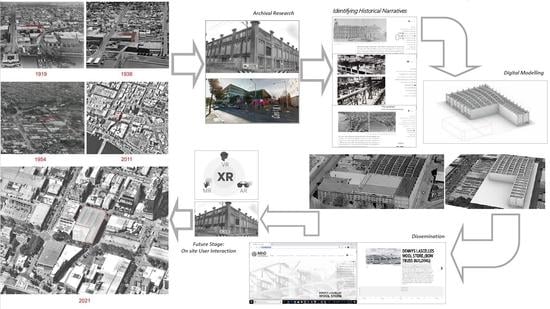

Considering the significant changes of the situation—limitation of budget and limitation of time—the research team decided that, instead of providing an onsite VR/AR experience for public interaction, the amended proposal would aim towards developing a bottom up user based framework for capturing the narrative of the building. Aligned with the changed research focus due to existing limitations of physical movements in public space, the study explored in-depth variations of cross-media storytelling in relation to digital (online) placemaking, in order to understand how different digital/virtual platforms can diversify and expand heritage experience. For this purpose, the project was designed/redesigned/undertaken in the following way with five specific stages illustrated in a flow diagram (

Figure 10).

Stage 1: collection and organization of insufficient heritage data, both tangible and intangible. In this stage, a thorough search was made by the team into all the available digital archives in Australia. Using TROVE (an online database by Australian National Library) as the starting point, the team browsed through different national, state level, and local databases for images, maps, publications, newspaper articles, and any other relevant information regarding the building itself, city of Geelong, and the wool industry in the region. The idea was to collect any fragments of information that might have some kind of connection with the case study building. Hence, a wider and broader search was done to understand the context under which the building was incepted, constructed, and eventually demolished. Since the building was demolished, there was very little visual data available in different online databases. No drawings of the building were found. Major descriptions about the buildings were mainly found in different newspaper articles between 1910 and 1917, describing this awe-inspiring building as an urban landmark. This fragmented information was initially organized chronologically using the online software Sutori, as an online interactive digital platform. Due to the lockdown in Victoria, Australia, the research team members could not meet physically and, hence, Sutori was a very good platform to interact with the information collected by different team members and edit if necessary.

Stage 2: identification of the main historical narratives. Once the collected data were initially organized chronologically, the team focused on identifying different historical narratives associated with building. The team identified three major historical narratives: the narrative of wool industry in Geelong region, the narrative of concrete architecture, and the narrative of urban development in Geelong. The initial database in Sutori was then collated according to the three narratives and different research team members were assigned to look into different narratives, focusing on creating a storyline for dissemination.

Stage 3: reconstruction of the digital model based on the archival evidence. Once the draft storyline of the three narratives were created and a case study building was placed on the intersection of the three narratives, all of the information relevant to the building and its architecture was collated, and a 3D virtual model of the building and the site was made based on the available date. The detailed process of the model making, based on the fragmented resources, was described in an earlier section.

Stage 4: collating the narratives into one storyboard. This stage involved collating all three narratives and the virtual model of the building into one storyboard for the general user. The storyboard was designed in a simple and easily accessible way, avoiding all the research related jargon so everyday users could easily grasp the content. However, information of a more complicated nature was linked in such a way that whoever is interested, could also have easy access.

Stage 5: dissemination of the storyboard via an interactive website. The final stage of the research involved developing a bottom up user based web framework for capturing the narrative of the building, available at

www.dennyslascelles.net (

Figure 11). This website is, at this moment, open for user feedback and comments, and contribution through interactive forums. Any user who has memories associated with this building, as well as any images, drawings, or photographs that are relevant, are encouraged to share them through the website. It is anticipated that, after one year of running the website, feedback and contributions will be collated with the main storyline. Hence, a web portal will work in both ways.

After completion of the project, we learnt what it meant to detach the heritage material from the physical location of origin, and consequently, how it could create a novel “digital heritage space” for the user. Throughout this process, the attempt was to understand the advantages and drawbacks of construction of “virtual” versus “physical” space in terms of representation of heritage material, and to understand how both can be utilized in a more creative and efficient way. Hence, the team has focused more on developing the digital model for exploring the storyboard instead of a photo realization of the original building. The key idea was to initiate and demonstrate the process of understanding how digital placemaking can complement physical placemaking, and vice-versa, through utilization and reconstruction of collected heritage material. In other words, the aim was to open the discussion, omitted so far, on construction of memory when the participant’s experience was obtained through engagement with “virtual historical space” compared to traditional means of heritage representation related to specific physical space (traditional museums, galleries, monuments, etc.).

The project made valuable scientific contribution in two aspects. First, it clearly demonstrated that such virtual models could create better narratives of the building and town, which cannot be gained from old pictures and historic material, only those that are currently fragmented. Collation of these fragmented materials into a linked open dataset (LOD) that was developed in the early stage of research using Sutori is an open-ended database that could include newer materials in the future, which could be used later for further study or modeling. The second scientific contribution is the user-based bottom up dissemination method, using the website to include user feedback for the next stage of the research (the 4D interactive narrative). It was mentioned earlier that, due to constraints imposed by the pandemic, the scope of the study was curtailed short. However, this study strongly substantiate the idea of a 4D narrative to fully capture the lost architecture of the building and equally emphasize the need of using different remote sensing tools for that exploration.

Learning from the project necessitates a novel digital heritage interpretation approach [

39] underpinned with the architectural theory, and supported by human-centered design and participatory design processes. That could be explored in the future by upscaling the project for the potential use of cutting-edge immersive extended reality (EX) technologies, such as virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR). The heritage content in XR will be relocated on a digital humanities geographic information system (GIS) platform, providing the general public an engaging experience through time and space as a 4D (3D + time) narrative. The results could be achieved through an interdisciplinary collaboration of researchers from architectural, design, heritage, and engineering areas.

In a situation where the heritage building is partially or fully lost, the project demonstrates that major interaction with the user is necessary for the experience to be memorable for the participant, which we tried to achieve through “digital storytelling” and creating new “digital narratives.” The literature and research findings from the field of memory studies show that memory of a place and, consequently, place attachment and place identity, can be severely endangered, and even fully erased through time when the physical artifact, including an architectural edifice, disappears/ is destroyed. There are no empirical studies reports published so far on how memory construction and reconstruction occur through engagement with virtual heritage places. Whether it could be done by VR or AR application or through mixed reality is a matter to be investigated further. The finding of the project raises questions about that. As we know, the VR environment and real physical environment, by using AR, often has very different approaches because of the different natures of experience and human–environment interaction. VR provides a total immersion, often of places that are hard to access or do not exist (anymore). Such experience can be accessed from anywhere, anytime, using a head-mounted display (e.g., Oculus Quest). During the global COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, many museums created so-called “museums from home” experiences, including in VR, for visitors who were not able to access physical museum exhibitions [

40]. AR, on the other side, augments physical reality by overlaying 2D or 3D information. The image is then projected on a smartphone, tablet (e.g., Pokémon GO game), or on special glasses (e.g., Hololens or MagicLeap). Current smartphones and tablets enable AR content to be accessed in situ, which is widely used in archaeology for interacting with 3D reconstructions of unpreserved heritage directly at the sites.

Despite the wide use of VR and AR in the heritage field, it is not well known how those technologies can support the representation of built heritage from the recent past, in regards to human engagement, with a place and place experience, particularly how those experiences impact memory construction, place attachment, and construction of identity related to a place. Moreover, how the same technologies can aid us in a process of successful placemaking.

Hence, as the next step, the team plans to take two wool industry heritage buildings in Geelong CBD as case studies to compare the quality of experiences of virtual versus physical engagement. One, the current Dennys Lascelles wool store that was eventually lost through time, and the other, the renovated building of the Dalgety and Co. wool store, which is currently used as the School of Architecture building for Deakin University. Through the planned empirical, qualitative comparative study of the two buildings, one reconstructed through various virtual technologies and the other still physically present on the location, the team will try to understand similarities and differences in human engagement between two places and, furthermore, how memories are constructed and reproduced in relation to each architectural structure.

5. Conclusions

The findings of this project further re-emphasize the need to explore in-depth variations of cross-media storytelling in relation to virtual (online) and physical (on-site) placemaking by application of different digital technologies, in order to understand how different digital/virtual platforms can diversify and expand heritage experience. It necessitates learning what it means to detach/remove the heritage material from the physical location of origin and, consequently, can create a new “digital heritage space” for recalling experience of the placemaking and a sense of place.

In terms of disciplinary contribution, this research will provide significant contribution to re-center our position to look into architecture, engineering, history, and society from a different perspective, as listed below.

- (1)

It will provide opportunities to revisit the ways of seeing the past through software or the design of the interface.

- (2)

It will sustain the information through a linked open database (LOD) for further research

- (3)

It will help us understand the spatial aspects of the built environment through a digital medium.

- (4)

It will test multimodal forms of collecting, storing, and disseminating research data.

- (5)

It will raise a new research question: does virtual immersion presupposes another way of interrogation?

- (6)

It will generate new research knowledge from a paradigm of static databases to a dynamic and interactive field using an immersive environment.

The main issues outlining the scope for recall and reconstruction, in this case, concerns the potential of a digital heritage narrative as a means towards placemaking. While exploring the new and unique capabilities provided by the digital narrative in capturing, simulating, and disseminating ‘lost’ architectural heritage, it will further imbue a sense of place by developing a sense of pride, belonging to the everyday city dweller. It is not only important to understand the past, but also to predict/design the future of the city as well.

In addition to contributing significantly to academia (in terms of knowledge generation), this project, and the discussed method of dissemination, has the potential to make significant social benefits—long-term benefits pertaining to the heritage management of these fragile sites with the use of diachronic end dimensional capturing techniques, to enable this knowledge to be conveyed to both academic and targeted audiences.