Leaf Segmentation Based on k-Means Algorithm to Obtain Leaf Angle Distribution Using Terrestrial LiDAR

Abstract

1. Introduction

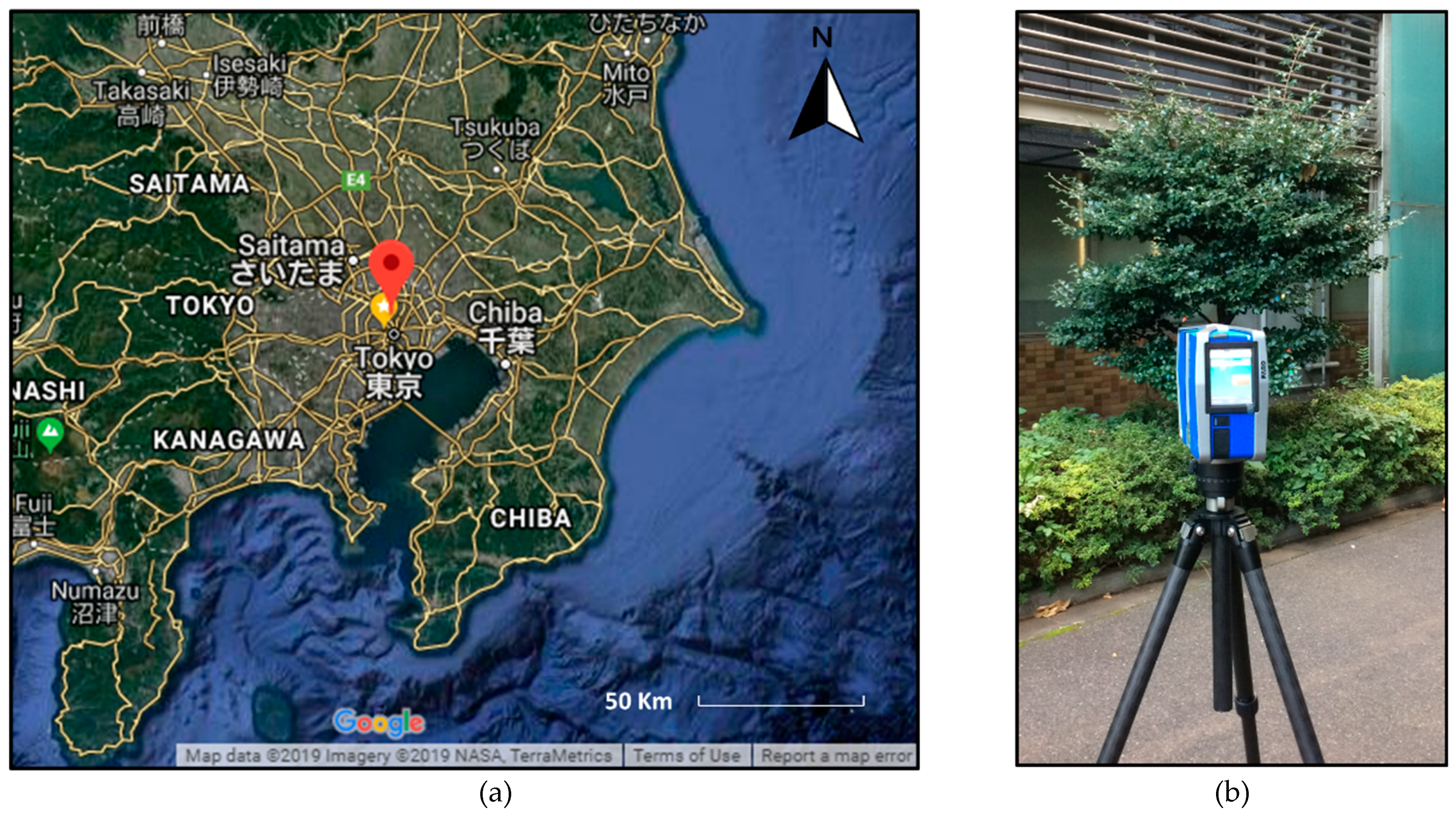

2. Materials and Methods

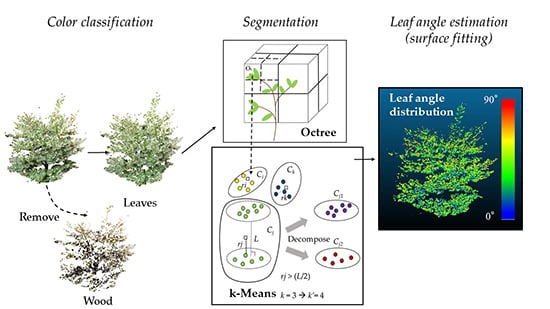

2.1. Study Site and Materials

2.2. Data Collection/Preprocessing

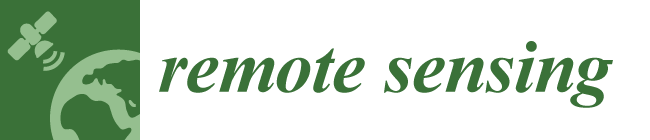

2.3. Leaf Segmentation

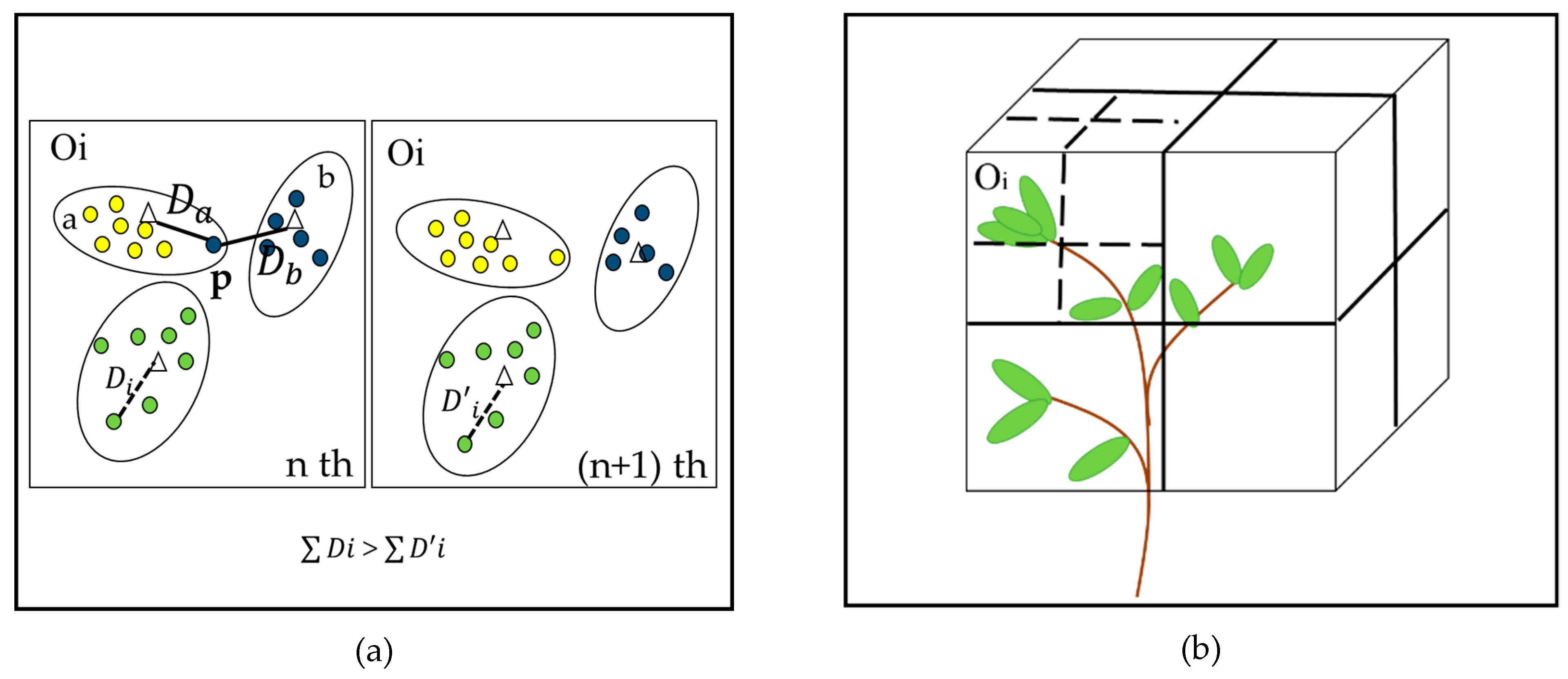

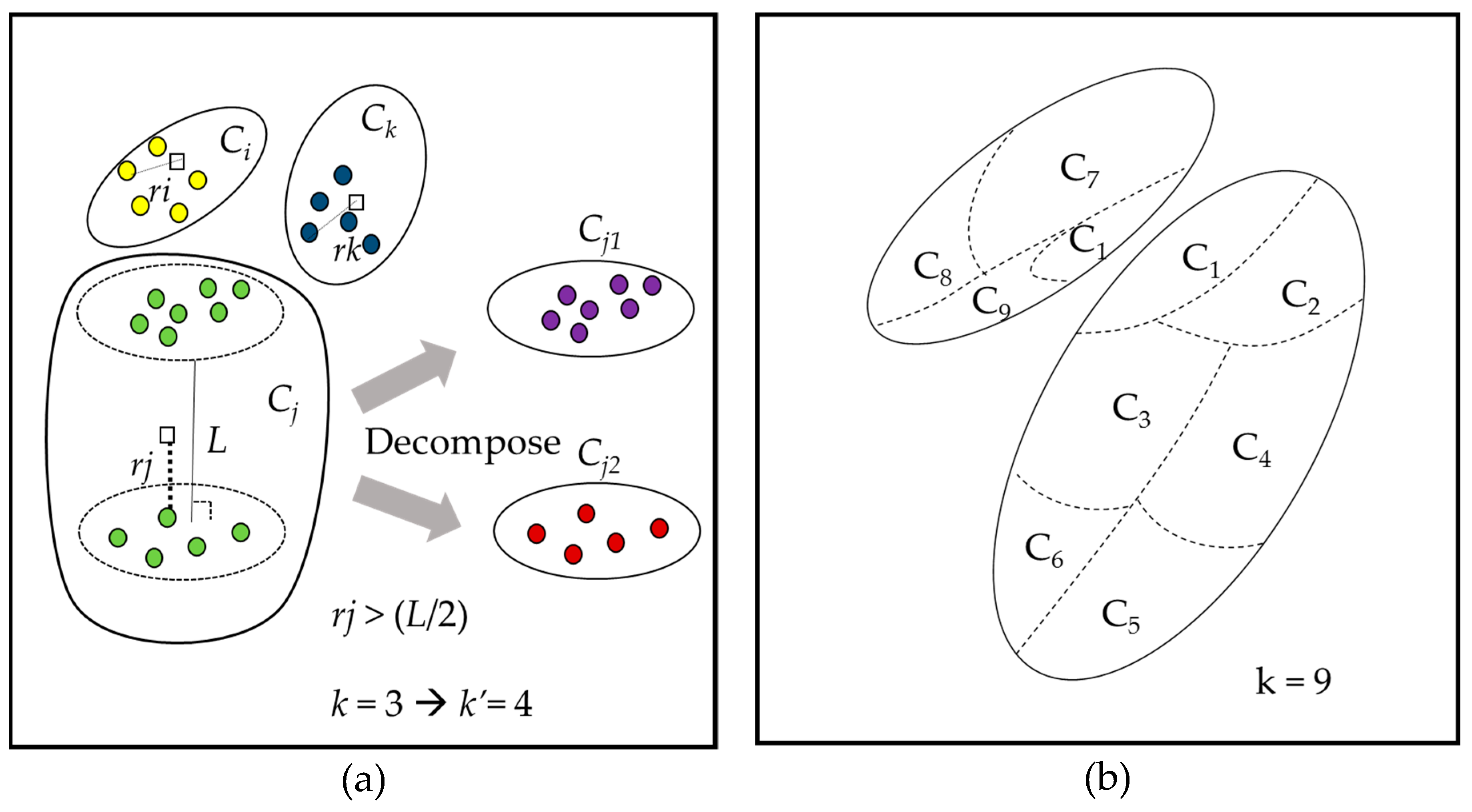

2.3.1. k-Means

2.3.2. Octree

2.3.3. k-Value for k-Means

2.4. Leaf Angle Calculation

Definition and Calculation

3. Results and Discussion

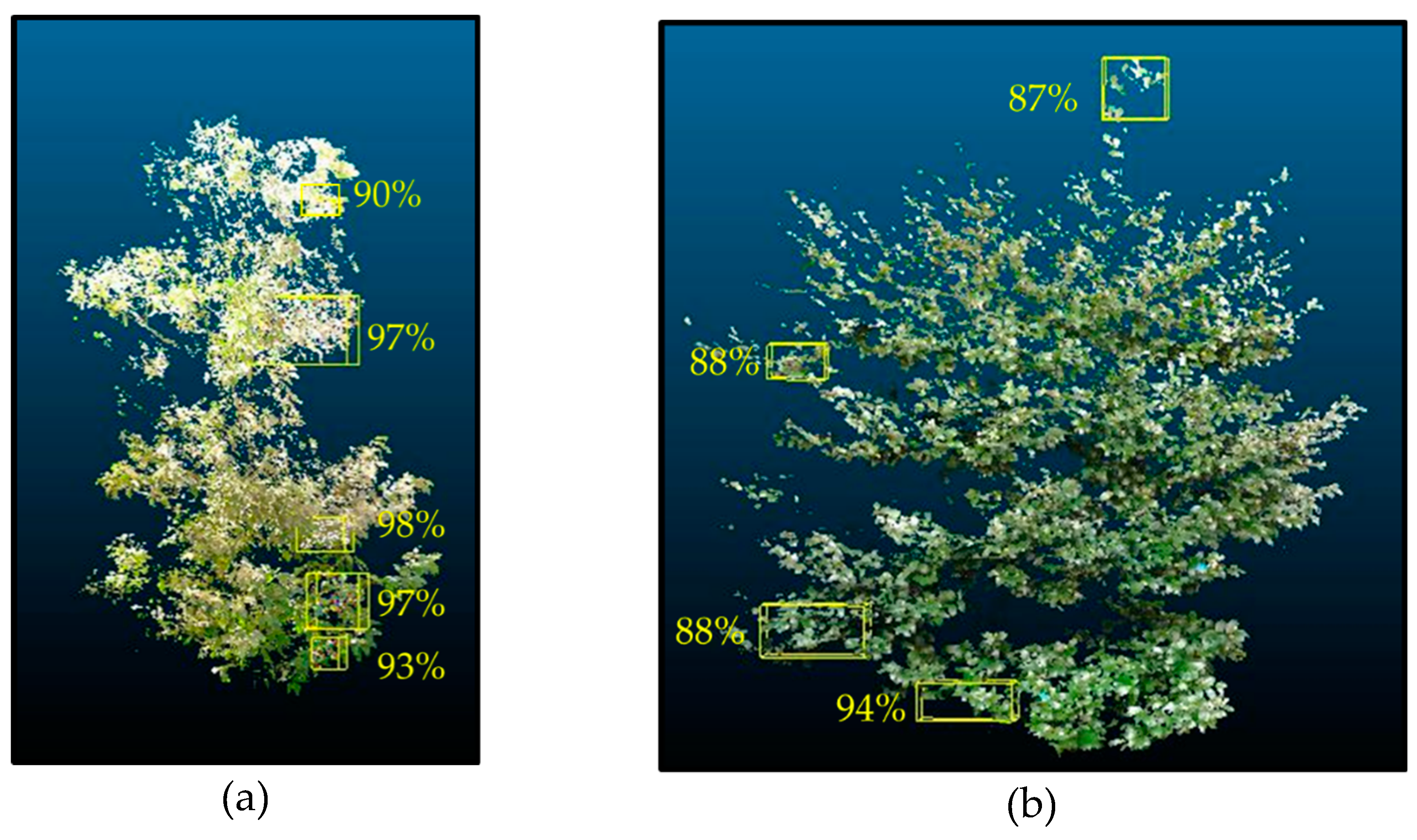

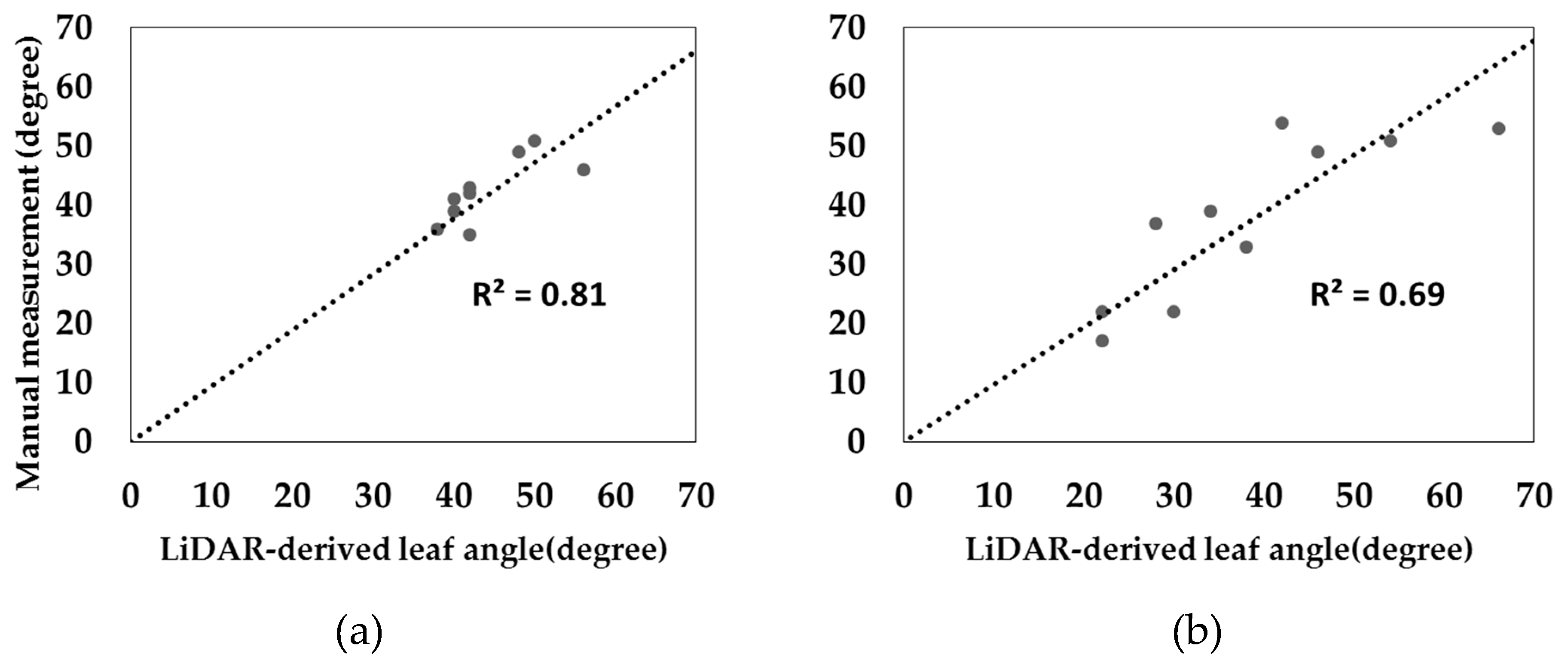

3.1. Validation

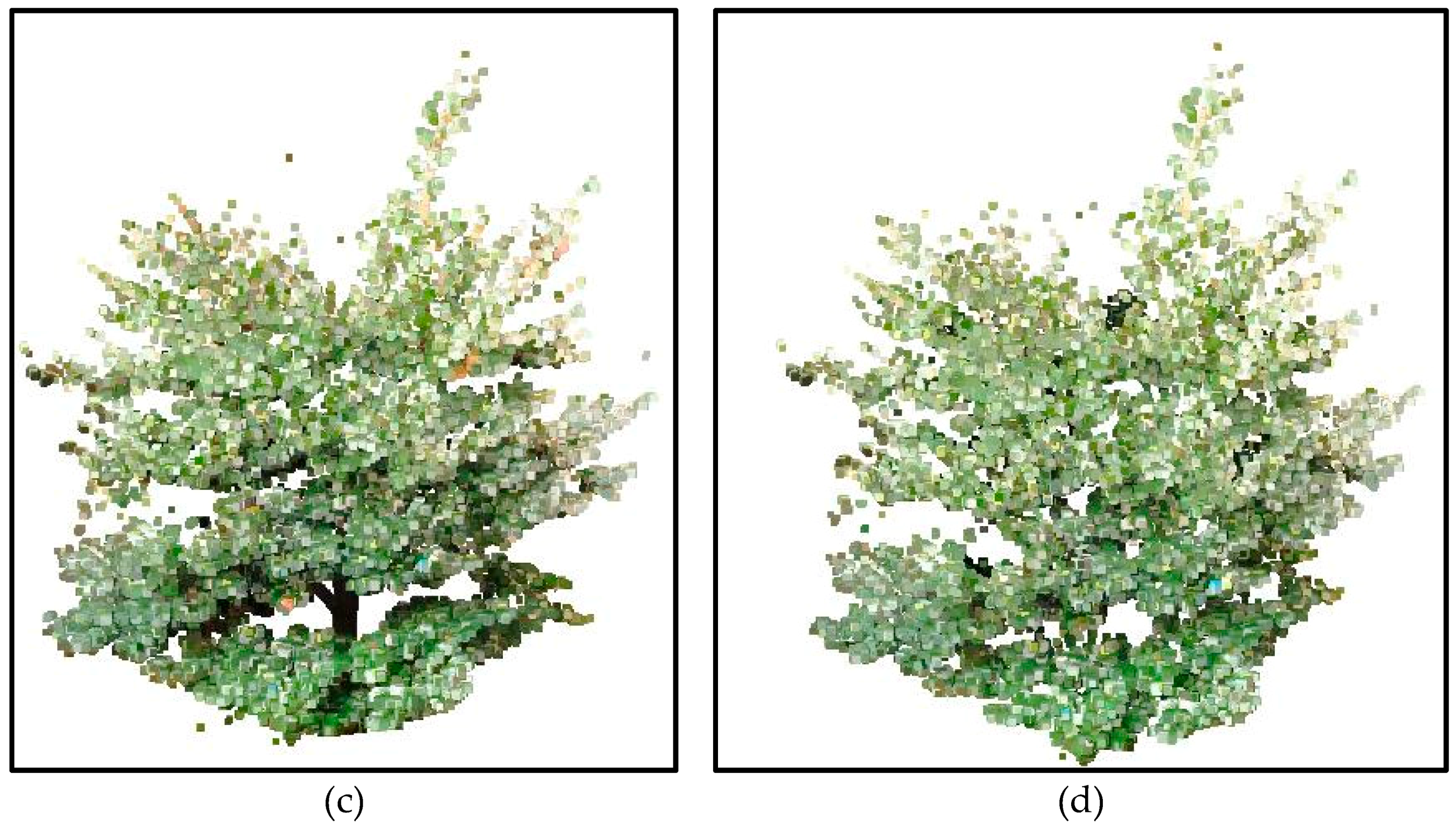

3.1.1. Removal of Non-Photosynthetic Wood

3.1.2. Segmentation of Leaves

3.1.3. Leaf Angle Estimates Based on Plane-Fitting Method

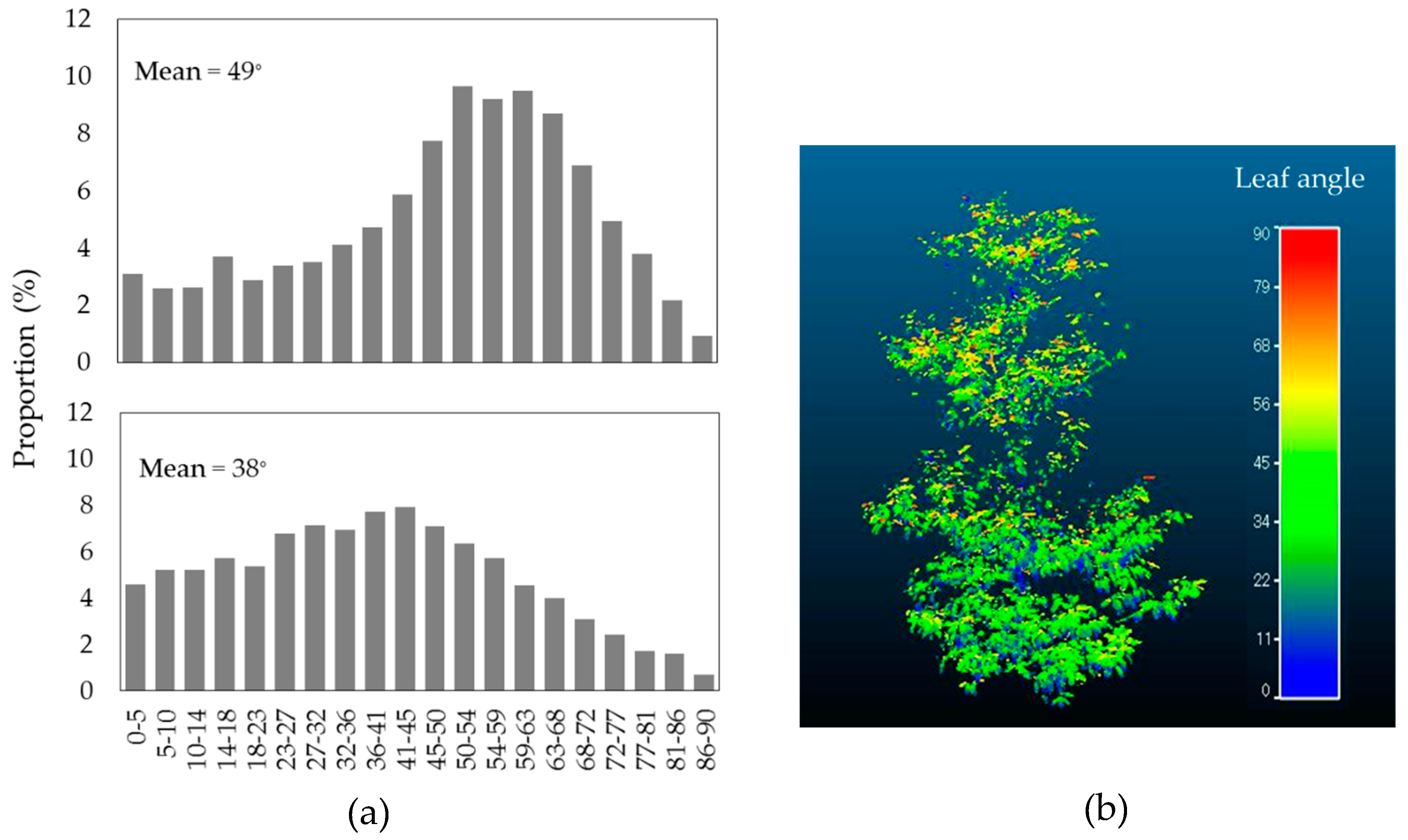

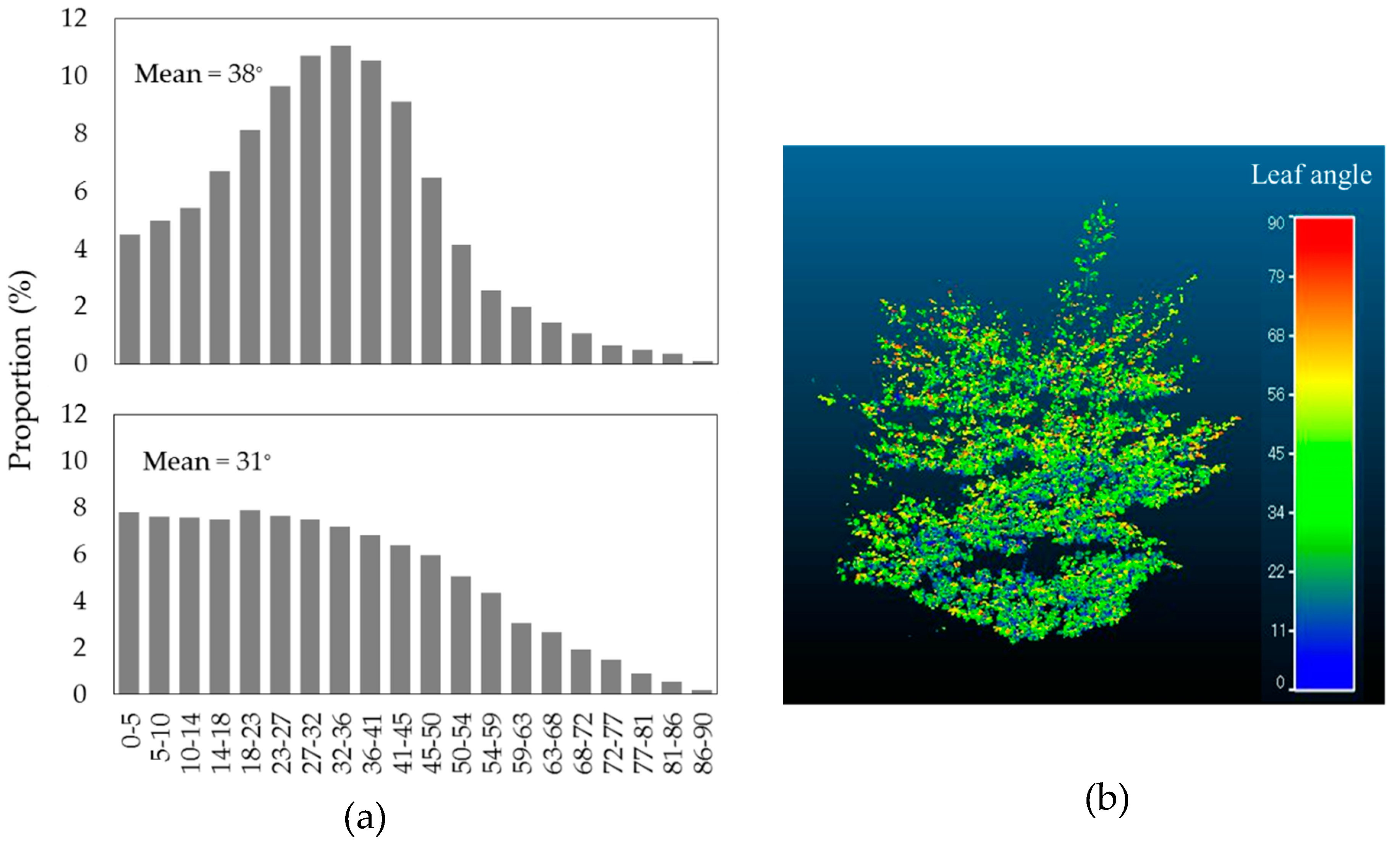

3.2. Leaf Angle Distribution (LAD)

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Welles, J.M. Some indirect methods of estimating canopy structure. Remote Sens Rev. 1990, 5, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falster, D.S.; Westoby, M. Leaf size and angle vary widely across species: What consequences for light interception? New Phytol. 2003, 158, 509–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bréda, N.J.J. Ground-based measurements of leaf area index: A review of methods, instruments and current controversies. J. Exp. Bot. 2003, 54, 2403–2417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogunbadewa, E.Y. Tracking seasonal changes in vegetation phenology with a SunScan canopy analyzer in northwestern England. For. Sci. Technol. 2012, 8, 161–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moorthy, I.; Miller, J.R.; Hu, B.; Chen, J.; Li, Q. Retrieving crown leaf area index from an individual tree using ground-based lidar data. Can. J. Remote Sens. 2008, 34, 320–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, M.; Baret, F.; Smith, G.J.; Jonckheere, I.; Coppin, P. Review of methods for in situ leaf area index (LAI) determination Part II. Estimation of LAI, errors and sampling. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2004, 121, 37–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goudriaan, J. The bare bones of leaf-angle distribution in radiation models for canopy photosynthesis and energy exchange. Agric. For. Meteorol. 1988, 43, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, J.M.; Campbell, G.S. Canopy structure. In Plant Physiological Ecology: Field Methods and Instrumentation; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1989; pp. 301–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welles, J.M.; Cohen, S. Canopy structure measurement by gap fraction analysis using commercial instrumentation. J. Exp. Bot. 1996, 47, 1335–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, B.N.; Mahaffee, W.F. Rapid measurement of the three-dimensional distribution of leaf orientation and the leaf angle probability density function using terrestrial LiDAR scanning. Remote Sens. Environ. 2017, 194, 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.M.; Li, Z.L.; Su, H.B. Comparison of leaf angle distribution functions: Effects on extinction coefficient and fraction of sunlit foliage. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2007, 143, 106–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, G.S. Extinction coefficients for radiation in plant canopies calculated using an ellipsoidal inclination angle distribution. Agric. For. Meteorol. 1986, 36, 317–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, G.S. Derivation of an angle density function for canopies with ellipsoidal leaf angle distributions. Agric. For. Meteorol. 1990, 49, 173–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisek, J.; Ryu, Y.; Alikas, K. Estimating leaf inclination and G-function from leveled digital camera photography in broadleaf canopies. Trees-Struct. Funct. 2011, 25, 919–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller-Linow, M.; Pinto-Espinosa, F.; Scharr, H.; Rascher, U. The leaf angle distribution of natural plant populations: Assessing the canopy with a novel software tool. Plant Methods 2015, 11, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicari, M.B.; Pisek, J.; Disney, M. New estimates of leaf angle distribution from terrestrial LiDAR: Comparison with measured and modelled estimates from nine broadleaf tree species. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2019, 264, 322–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; García, M.; Liu, S.; Guo, Q.; Chen, G.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, Y.; Meng, X. Terrestrial lidar remote sensing of forests: Maximum likelihood estimates of canopy profile, leaf area index, and leaf angle distribution. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2015, 209–210, 100–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itakura, K.; Kamakura, I.; Hosoi, F. Three-Dimensional Monitoring of Plant Structural Parameters and Chlorophyll Distribution. Sensors 2019, 19, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, G.; Moskal, L.M. Leaf orientation retrieval from terrestrial laser scanning (TLS) data. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2012, 50, 3970–3979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Béland, M.; Widlowski, J.L.; Fournier, R.A.; Côté, J.F.; Verstraete, M.M. Estimating leaf area distribution in savanna trees from terrestrial LiDAR measurements. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2011, 151, 1252–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Dai, L.; Wang, H.; Wang, Y.; He, Z.; Lin, S. Estimating Leaf Area Density of Individual Trees Using the Point Cloud Segmentation of Terrestrial LiDAR Data and a Voxel-Based Model. Remote Sens. 2017, 9, 1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosoi, F.; Omasa, K. Factors contributing to accuracy in the estimation of the woody canopy leaf area density profile using 3D portable lidar imaging. J. Exp. Bot. 2007, 58, 3463–3473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosoi, F.; Omasa, K. Estimating leaf inclination angle distribution of broad-leaved trees in each part of the canopies by a high-resolution portable scanning lidar. J. Agric. Meteorol. 2015, 71, 136–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eitel, J.U.H.; Vierling, L.A.; Long, D.S. Simultaneous measurements of plant structure and chlorophyll content in broadleaf saplings with a terrestrial laser scanner. Remote Sens. Environ. 2010, 114, 2229–2237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itakura, K.; Hosoi, F. Estimation of leaf inclination angle in three-dimensional plant images obtained from lidar. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.; Tamura, M.; Susaki, J. A new approach to retrieve leaf normal distribution using terrestrial laser scanners. J. For. Res. 2016, 27, 631–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, S.; Guo, Q.; Xu, S.; Su, Y.; Li, Y.; Wu, F. A geometric method for wood-leaf separation using terrestrial and simulated lidar data. Photogramm. Eng. Remote Sens. 2015, 81, 767–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Zheng, G.; Eitel, J.U.H.; Moskal, L.M.; He, W.; Huang, H. Improved Salient Feature-Based Approach for Automatically Separating Photosynthetic and Nonphotosynthetic Components within Terrestrial Lidar Point Cloud Data of Forest Canopies. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2016, 54, 679–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicari, M.B.; Disney, M.; Wilkes, P.; Burt, A.; Calders, K.; Woodgate, W. Leaf and wood classification framework for terrestrial LiDAR point clouds. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2019, 10, 680–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, A.K.; Murty, M.N.; Flynn, P.J. Data clustering: A review. Proc. ACM Comput. Surv. 1999, 31, 264–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meagher, D. Octree Encoding: A New Technique for the Representation, Manipulation and Display of Arbitrary 3-D Objects by Computer; Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute: New York, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Purnima, B.; Arvind, K. EBK-Means: A Clustering Technique based on Elbow Method and K-Means in WSN. Int. J. Comput. Appl. 2014, 105, 17–24. [Google Scholar]

- Hoppe, H.; DeRose, T.; Duchamp, T.; McDonald, J.; Stuetzle, W. Surface reconstruction from unorganized points. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 19th Annual Conference on Computer Graphics and Interactive Techniques-SIGGRAPH’92; Chicago, IL, USA, 26–31 July 1992, pp. 71–78. [CrossRef]

- Mitra, N.J.; Nguyen, A.; Guibas, L. Estimating surface normals in noisy point cloud data. Proc. Int. J. Comput. Geom. Appl. 2004, 14, 261–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, B.N.; Mahaffee, W.F. Rapid, high-resolution measurement of leaf area and leaf orientation using terrestrial LiDAR scanning data. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2017, 28, 064006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itakura, K.; Hosoi, F. Voxel-based leaf area estimation from three-dimensional plant images. J. Agric. Meteorol. 2019, 75, 211–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kuo, K.; Itakura, K.; Hosoi, F. Leaf Segmentation Based on k-Means Algorithm to Obtain Leaf Angle Distribution Using Terrestrial LiDAR. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 2536. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs11212536

Kuo K, Itakura K, Hosoi F. Leaf Segmentation Based on k-Means Algorithm to Obtain Leaf Angle Distribution Using Terrestrial LiDAR. Remote Sensing. 2019; 11(21):2536. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs11212536

Chicago/Turabian StyleKuo, Kuangting, Kenta Itakura, and Fumiki Hosoi. 2019. "Leaf Segmentation Based on k-Means Algorithm to Obtain Leaf Angle Distribution Using Terrestrial LiDAR" Remote Sensing 11, no. 21: 2536. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs11212536

APA StyleKuo, K., Itakura, K., & Hosoi, F. (2019). Leaf Segmentation Based on k-Means Algorithm to Obtain Leaf Angle Distribution Using Terrestrial LiDAR. Remote Sensing, 11(21), 2536. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs11212536