The Sustainable Personality in Entrepreneurship: The Relationship between Big Six Personality, Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy, and Entrepreneurial Intention in the Chinese Context

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Development and Hypotheses

2.1. Big Six Personality Related to Entrepreneurial Intention

2.2. Big Six Personality Related to Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy

2.3. Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy Related to Entrepreneurial Intention

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Collection and Sample

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Control Variables

3.2.2. Research Variables

3.3. Reliability and Validity

3.4. Common Method Bias

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Analyses

4.2. Analyses of Structural Model

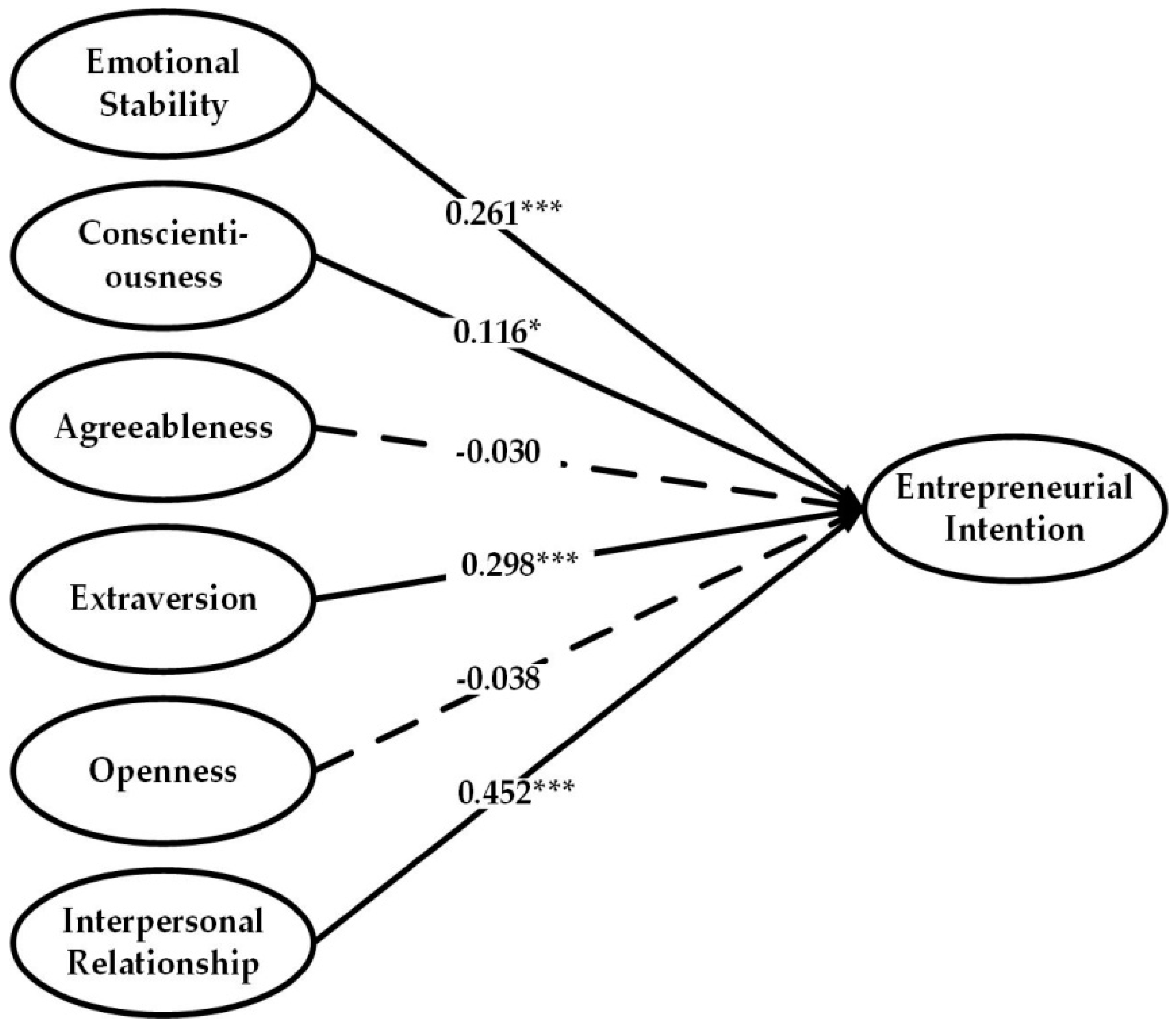

4.2.1. Testing for Total Effect

4.2.2. Testing for Mediated Effect

5. Discussion

5.1. Implications

5.1.1. Implications for Research

5.1.2. Implications for Practice

5.1.3. Limitations

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Krueger, N.F.; Reilly, M.D.; Carsrud, A.L. Competing models of entrepreneurial intentions. J. Bus. Ventur. 2000, 15, 411–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, B.J.; Brush, C.G. A Gendered Perspective on Organizational Creation. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2003, 26, 41–65. [Google Scholar]

- Faylolle, A.; Liñán, F. The future of research on entrepreneurial intentions. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 663–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirokova, G.; Osiyevskyy, O.; Bogatyreva, K. Exploring the intention–behavior link in student entrepreneurship: Moderating effects of individual and environmental characteristics. Eur. Manag. J. 2016, 34, 386–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchflower, D. Self-employment in OECD Countries. Labour Econ. 2000, 7, 471–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, W.; Wang, Z. The study of entrepreneurial intention and its determinants. Psychol. Sci. 2004, 124, 1213–1216. [Google Scholar]

- Werner, A.; Gast, J.; Kraus, S. The effect of working time preferences and fair wage perceptions on entrepreneurial intentions among employees. Small Bus. Econ. 2014, 43, 137–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Bao, H.; Peng, Y. Which factors affect landless peasants’ intention for entrepreneurship? A case study in the south of the Yangtze river delta, china. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, L.; Wong, P.K.; Foo, M.D.; Leung, A. Entrepreneurial intentions: The influence of organizational and individual factors. J. Bus. Ventur. 2011, 26, 124–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, G.; DeNoble, A. Views on self-employment and personality: An exploratory study. J. Dev. Entrep. 2003, 8, 265. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.H.; Chang, C.C.; Yao, S.N.; Liang, C. The contribution of self-efficacy to the relationship between personality traits and entrepreneurial intention. Higher Educ. 2016, 72, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapero, A.; Sokol, L. The social dimensions of entrepreneurship. Soc. Sci. El. P. 2009, 25, 28. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1497759 (accessed on 3 October 2009).

- Rauch, A.; Frese, M. Born to be an entrepreneur? Revisiting the personality approach to entrepreneurship. In The Psychology of Entrepreneurship; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2007; pp. 41–65. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, G.; Li, J.; Matla, H. Who Are the Chinese Private Entrepreneurs? J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2006, 13, 148–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, S.C. Why do small firms produce the entrepreneurs? J. Socio-Econ. 2009, 38, 484–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, S.; Filser, M.; O’Dwyer, M.; Shaw, E. Social entrepreneurship: An exploratory citation analysis. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2014, 8, 275–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, L.R. Language and individual differences: The search for universals in personality lexicons. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1981, 59, 141–165. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg, L.R. An alternative “description of personality”: The big-five factor structure. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1990, 59, 1216–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldberg, L.R. The development of markers for the Big-Five factor structure. Psychol. Assess. 1992, 4, 26–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.F.; Guo, Y.Y. To view personality from the perspective of interpersonal relationship. Psychol. Explor. 2006, 1, 13–17. [Google Scholar]

- Brice, J. The Role of Personality Dimensions on the Formation of Entrepreneurial Intentions; Hofstra University: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Hmieleski, K.M.; Corbett, A.C. Proclivity for improvisation as a predictor of entrepreneurial intentions. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2006, 44, 45–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Seibert, S.E.; Lumpkin, G.T. The relationship of personality to entrepreneurial intentions and performance: A meta-analytic review. J. Manag. 2010, 36, 381–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandstätter, H. Personality aspects of entrepreneurship: A look at five meta-analyses. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2011, 51, 222–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Zhang, X.K. The path model of the relationship of personality traits, entrepreneurial self-efficacy, and entrepreneurial intention among college students. Stud. Psychol. Behav. 2014, 12, 806–812. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.H. Research on the relationship of personality traits and entrepreneurial intention among new generation of college students: The mediating role of entrepreneurial self-efficacy. Manag. Admin. 2016, 10, 149–153. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.X.; Zhou, M.J. The exploration of Chinese personality structure: The six factors hypothesis of personality traits. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2006, 14, 574–585. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.F.; Cui, H. The Chinese personality traits: Interpersonal relationship. Psychol. Explor. 2008, 4, 41–45. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, D.B.; Xi, Y.H. The theoretical exploration and philosophy reflection on personality trait in Chinese context. J. Wuhan Univ. Technol. (Soc. Sci. Ed.). 2013, 26, 381–386. [Google Scholar]

- Song, W.Z.; Zhang, J.X.; Zhang, M.Q.; Liang, J. Procedure for development of the Chinese personality assessment inventory and its meaning (CPAI). Acta Psychol. Sin. 1993, 4, 400–407. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung, F.M.; Leung, K.; Fan, R.M.; Song, W.Z.; Zhang, J.X.; Zhang, J.P. Development of the Chinese personality assessment inventory (CPAI). J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 1996, 27, 181–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.X.; Zhang, M.Q.; Liang, J. Clinical utility of the Big Six personality-the relation mode of the Chinese Personality Assessment Inventory (CPAI), the NEO Five-factor Inventory and the clinical scale MMPI-2. In Proceedings of the Fourth Academic Conference of China Mental Health Association, Hangzhou, China, 1 September 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, T. The ERP Study of Interpersonal Relationship as a Personal Trait; Shanghai Normal University: Shanghai, China, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.S. On the sinicization of personality trait research. J. Chongqing Norm. Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.). 2005, 1, 103–108. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, A.H. Chinese Characteristics; People’s Daily Press: Beijing, China, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, Z.T. Chinese Gossip Sayings; Shanghai Literature and Art Publishing CO.: Shanghai, China, 2006; p. 124. [Google Scholar]

- Mischel, W. Toward a cognitive social learning reconceptualization of personality. Psychol. Rev. 1973, 80, 252–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zayas, V.; Shoda, Y.; Ayduk, O.N. Personality in context: An interpersonal systems perspective. J. Pers. 2002, 70, 852–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanfer, R.; Wanberg, C.R.; Kantrowitz, T.M. Job search and employment: A personality-motivational analysis and meta-analytic review. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 837–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pappas, J.B.; Pappas, E.C. The sustainable personality: Values and behaviors in individual sustainability. Int. J. Higher Educ. 2014, 4, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morizot, J.; Blanc, M.L. Continuity and change in personality traits from adolescence to midlife: A 25-year longitudinal study comparing representative and adjudicated men. J. Pers. 2003, 71, 705–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, G.H.; Lu, H.L.; Liu, H.Y. An empirical study of the influence of interpersonal relationship on corporate purchase intention—Based on Chinese cultural context. J. Shanxi Univ. Finance Econ. 2010, 32, 60–67. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, X.H.; Zhang, G.J. An empirical research of the relationship between interpersonal relationship of virtual community and tourism behavior intention. Geogr. Geo-Inf. Sci. 2015, 4, 116–120. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, D.I.; Ehrlich, S.B.; De Noble, A.F.; Baik, K.B. Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy and Its Relationship to Entrepreneurial Action: A Comparative Study between the US and Korea. Manag. Int. 2001, 6, 41–53. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.C.; Greene, P.G.; Crick, A. Does entrepreneurial self-efficacy distinguish entrepreneurs from managers? J. Bus. Ventur. 1998, 13, 295–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthans, F.; Ibrayeva, E.S. Entrepreneurial self-efficacy in central Asian transition economies: Quantitative and qualitative analyses. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2006, 37, 92–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naktiyok, A.; Karabey, C.N.; Gulluce, A.C. Entrepreneurial self-efficacy and entrepreneurial intention: The turkish case. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2010, 6, 419–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.Y. The exploration of mechanism of the mediating effect of entrepreneurial self-efficacy. J. Psychol. Sci. 2011, 34, 911–914. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Guo, F.C. The relationship among Entrepreneurial stress, entrepreneurial self-efficacy and entrepreneurial intention of Higher Vocational College Students. Res. Higher Educ. Eng. 2015, 2, 164–168. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.; Klein, H.J. Relationships between conscientiousness, self-efficacy, self-deception, and learning over time. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 1175–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nauta, M.M. Self-efficacy as a mediator of the relationships between personality factors and career interests. J. Career Assess. 2004, 12, 381–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, E.R.; Whiteman, M.C. “I think I can, I think I can …”: The interrelationships among self-assessed intelligence, self-concept, self-efficacy and the personality trait intellect in university students in Scotland and New Zealand. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2007, 43, 959–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tams, S. Self-directed social learning: The role of individual differences. J. Manag. Dev. 2008, 27, 196–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strobel, M.; Tumasjan, A.; Spörrle, M. Be yourself, believe in yourself, and be happy: Self-efficacy as a mediator between personality factors and subjective well-being. Scand. J. Psychol. 2011, 52, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.L.; Wang, C.K. The relationship between big five personality and life meaning: The mediating role of self-efficacy and social support. In Proceedings of the Abstracts of Fifteenth National Conference on Psychology, Guangzhou, China, 1–2 December 2012; p. 394. [Google Scholar]

- Karwowski, M.; Lebuda, I.; Wisniewska, E.; Gralewski, J. Big five personality traits as the predictors of creative self-efficacy and creative personal identity: Does gender matter? J. Creative Behav. 2013, 47, 215–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caprara, G.V.; Vecchione, M.; Alessandri, G.; Gerbino, M.; Barbaranelli, C. The contribution of personality traits and self-efficacy beliefs to academic achievement: A longitudinal study. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2011, 81, 78–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kristof, A.L. Person-organization fit: An integrative review of its conceptualizations, measurement, and implications. Pers. Psychol. 1996, 49, 1–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.A.; Markman, G.D. Person-Entrepreneurship Fit: The Role of Individual Difference Factors in New Venture Formation; Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Méndez-Picazo, M.-T.; Galindo-Martín, M.-A.; Ribeiro-Soriano, D. Governance, entrepreneurship and economic growth. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2012, 24, 865–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Major, D.A.; Turner, J.E.; Fletcher, T.D. Linking proactive personality and the Big Five to motivation to learn and development activity. J Appl. Psychol. 2006, 91, 927–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, H.; Seibert, S.E. The Big Five personality dimensions and entrepreneurial status: A meta-analytical review. J Appl. Psychol. 2006, 91, 259–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rauch, A.; Frese, M. Let’s put the person back into entrepreneurship research: A meta-analysis on the relationship between business owners’ personality traits, business creation, and success. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2007, 16, 353–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.F.; Huang, J. Thinking styles and the five-factor model of personality. Eur. J. Pers. 2001, 15, 465–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.T.; Chia, T.L.; Liang, C. Effect of personality differences in shaping entrepreneurial intention. Int. J. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2015, 6, 166–176. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, B. The Problem of China; Coronet Books: London, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, W.H. Views on humanism in Confucian based on Moral Philosophy. Theory Month 2007, 12, 53–55. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol. Rev. 1977, 84, 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stajkovic, A.; Luthans, F. Self-efficacy and work-related performance: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 1998, 124, 240–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge, T.A.; Bono, J.E. Relationship of core self-evaluations traits-self-esteem, generalized self-efficacy, locus of control, and emotional stability-with job satisfaction and job performance: A meta-analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dormann, C.; Fay, D.; Zapf, D.; Frese, M. A state-trait analysis of job satisfaction: On the effect of core self-evaluations. Appl. Psychol. Int. Rev. 2006, 55, 27–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markman, G.D.; Balkin, D.B.; Baron, R.A. Inventors and new venture formation: The effects of general self-efficacy and regretful thinking. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2002, 27, 149–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markman, G.D.; Baron, R.A.; Balkin, D.B. Are perseverance and self-efficacy costless? Assessing entrepreneurs’ regretful thinking. J. Organ. Behav. 2005, 26, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Noble, A.F.; Jung, D.; Ehrlich, S.B. Entrepreneurial self-efficacy: The development of a measure and its relationship to entrepreneurial action. Available online: https://fusionmx.babson.edu/entrep/fer/papers99/I/I_C/IC.html (accessed on 25 March 2000).

- Hmieleski, K.M.; Corbett, A.C. The contrasting interaction effects of improvisational behavior with entrepreneurial self-efficacy on new venture performance and entrepreneur work satisfaction. J. Bus. Ventur. 2008, 23, 482–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, O.P.; Naumann, L.P.; Soto, C.J. Paradigm shift to the integrative Big Five trait taxonomy: History, measurement, and conceptual issues. In Handbook of Personality: Theory and Research, 3rd ed.; John, O.P., Robins, R.W., Pervin, L.A., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 114–158. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd, N.G.; Vozikis, G.S. The influence of self-efficacy on the development of entrepreneurial intentions and actions. Entrep. Theory Pract. 1994, 18, 63. [Google Scholar]

- Neck, C.P.; Neck, H.M.; Manz, C.C.; Godwin, J. “I think I can; I think I can”: A self-leadership perspective toward enhancing entrepreneur through patterns, self-efficacy, and performance. J. Manag. Psychol. 1999, 14, 477–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vesalainen, J.; Pihkala, T. Motivation structure and entrepreneurial intentions. In Proceedings of the Nineteenth Babson College-Kauffman Foundation Entrepreneurship Research Conference, Columbia, SC, USA, 5 May 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Cultivate self-efficacy for personal and organizational effectiveness. In Handbook of Principles of Organization Behavior; Locke, E.A., Ed.; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2000; pp. 120–136. [Google Scholar]

- Piperopoulos, P.; Dimov, D. Burst Bubbles or Build Steam? Entrepreneurship education, entrepreneurial self-efficacy, and entrepreneurial intentions. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2014, 3, 970–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, W.A.; Cooper, S.Y. Enhancing self-efficacy to enable entrepreneurship: The case of CMI’s connections. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=568383 (accessed on 23 July 2004).

- Davidsson, P. Determinants of entrepreneurial intentions. In Proceedings of the RENT XI Workshop, Piacenza, Italy, 23–24 Novermber 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Mei, H.; Zhan, Z.; Fong, P.S.W.; Liang, T.; Ma, Z. Planned behaviour of tourism students’ entrepreneurial intentions in China. Appl. Econ. 2015, 13, 1240–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychology Theory, 2nd ed.; Mcgraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L. Multivariate Data Analysis; Pearson Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2006; Volume 6. [Google Scholar]

- Harman, H.H. Modern Factor Analysis; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, Z.L.; Ye, B.J. Mediating effect analysis: Development of methods and models. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2014, 22, 731–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raja, U.; Johns, G.; Ntalianis, F. The impact of personality on psychological contracts. Acad. Manag. J. 2004, 47, 350–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markus, H.; Cross, S. The interpersonal self. In Handbook of Personality: Theory and Research; Pervin, L.A., Ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1990; pp. 576–608. [Google Scholar]

- Scheler, M. Formalism in Ethics and Non-Formal Ethics of Values; Joint Publishing: Beijing, China, 2004; p. 594. [Google Scholar]

- Xing, Y. On the Personality Value of Ideas of Sustainable Development. Stud. Dialect. Nat. 2001, 1, 53–57. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, D.Y. On the personality disorder of sustainable development and its elimination. Theory Invest. 2000, 1, 25–27. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Q.J. Study on the path to increase college students’ ability for sustainable development from the perspective of demand: Enlightenment from western classical demand theory. Hubei Soc. Sci. 2014, 12, 170–173. [Google Scholar]

- Ismail, M.; Khalid, S.A.; Othman, M.; Jusoff, H.K. Entrepreneurial intention among malaysian undergraduates. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2009, 4, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.F. The impacts of Big Five personality on entrepreneurial self-efficacy and entrepreneurial intention. Harbin Inst. Technol. 2013, 2, 63. [Google Scholar]

- Mcgee, J.E.; Peterson, M. The long-term impact of entrepreneurial self-efficacy and entrepreneurial orientation on venture performance. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social Foundation of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive View; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Kickul, J.; D’Intino, R.S. Measure for measure: Modeling entrepreneurial self-efficacy onto instrumental tasks within the new venture creation process. Available online: http://digitalcommons.sacredheart.edu/neje/vol8/iss2/6/ (accessed on 15 December 2014).

- Wu, J.Z.; Li, Y.B. The impact of perceived environment on entrepreneurship of middle-level managers. Chin. J. Manag. 2015, 12, 111–117. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, W.X.; Hu, H.H. The relationship between entrepreneurial self-efficacy, social support and entrepreneurial intention among college students: An empirical study of five colleges in Jiangsu. Jiangxi Soc. Sci. 2016, 36, 244–250. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, Q.; Zhang, C. An Analysis of the Transmission Mechanism from Social Network to Individual Entrepreneurial Intentions. Manag. Rev. 2017, 29, 59–67. [Google Scholar]

- Murugesan, R.; Jayavelu, R. The influence of big five personality traits and self-efficacy on entrepreneurial intention the role of gender. J. Entrep. Innov. Emerg. Econ. 2017, 3, 41–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soriano, D.R.; Roig, S.; Sanchis, J.R.; Torcal, R. The role of consultants in SMEs: The use of services by Spanish industry. Int. Small Bus. J. 2002, 20, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fellnhofer, K.; Kraus, S.; Bouncken, R. The current state of research on sustainable entrepreneurship. Int. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 14, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Perlines, F.; Rung-Hoch, N. Sustainable entrepreneurial orientation in family firms. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mas-Verdu, F.; Soriano, D.R.; Dobon, S.R. Regional development and innovation: The role of services. Serv. Indus. J. 2010, 30, 633–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mas-Tur, A.; Soriano, D.R. The level of innovation among young innovative companies: The impacts of knowledge-intensive services use, firm characteristics and the entrepreneur attributes. Serv. Bus. 2014, 8, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Factors and Items | CFA Loadings | Cronbach’s α | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Emotional Stability (ES) | 0.891 | 0.893 | 0.626 | |

| (ES1) I often feel anxious and worried about my learning state | 0.771 | |||

| (ES2) I would like to try even if the probability of success is very low | 0.796 | |||

| (ES3) No matter what I do, I am always confident in myself | 0.831 | |||

| (ES4) I can control my emotions well, without the influence of mood swings | 0.776 | |||

| (ES5) I always show my leadership skills in team activities. | 0.780 | |||

| 2. Conscientiousness (C) | 0.756 | 0.760 | 0.514 | |

| (C1) I always do well in combining individual goals with organizational goals | 0.680 | |||

| (C2) I make careful arrangement of everything I do | 0.789 | |||

| (C3) I have the ability to do my job on the ground | 0.677 | |||

| 3. Agreeableness (A) | 0.865 | 0.869 | 0.690 | |

| (A1) If one doesn’t complete the given task as my expectation, I won’t blame him. | 0.774 | |||

| (A2) When I get along with others, I am flexible and will not easily offend others | 0.854 | |||

| (A3) I think the family bond is the most important emotion in all kinds of relationships | 0.861 | |||

| 4. Extraversion (E) | 0.718 | 0.888 | 0.566 | |

| (E1) When I get along with others, I always actively communicate with them | 0.695 | |||

| (E2) In group activities, I always do what I want to do | 0.805 | |||

| 5. Openness (O) | 0.771 | 0.772 | 0.531 | |

| (O1) I always think about things with running wild mind | 0.780 | |||

| (O2) I am always keen on using the latest electronic products | 0.673 | |||

| (O3) I often spend excess budget | 0.730 | |||

| 6. Interpersonal Relationship (IR) | 0.905 | 0.905 | 0.577 | |

| (IR1) When I encounter difficulties and setbacks in life, I will also be positive and optimistic to face | 0.779 | |||

| (IR2) I feel tired when I handle things which need much to be considered | 0.671 | |||

| (IR3) I am flexible in dealing with conflicts in Interpersonal Relationship | 0.762 | |||

| (IR4) I always try to maintain harmony in communication | 0.793 | |||

| (IR5) When I encounter setbacks and difficulties, I always comfort myself with “winner” attitude | 0.713 | |||

| (IR6) I will do things in order to gain appreciation or favor from others | 0.815 | |||

| (IR7) When my mood is swing, I may do something irrational | 0.776 | |||

| 7. Entrepreneurial Self-efficacy (ESE) | 0.868 | 0.867 | 0.686 | |

| (ESE1) I can identify the potential value of an idea | 0.785 | |||

| (ESE2) I can effectively convince people who have different ideas with me | 0.840 | |||

| (ESE3) It is a pleasure to cooperate with others | 0.858 | |||

| 8. Entrepreneurial Intention (EI) | 0.859 | 0.861 | 0.608 | |

| (EI1) I will create venture in the future | 0.830 | |||

| (EI2) If I could freely make occupational decision, I will create venture | 0.739 | |||

| (EI3) Considering the various restrictions such as funds shortage or less family support), I will still choose entrepreneurship first | 0.784 | |||

| (EI4) It is most likely that I will create venture in the next five years | 0.762 |

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Emotional Stability | 0.791 | |||||||

| 2. Conscientiousness | 0.315 ** | 0.717 | ||||||

| 3. Agreeableness | 0.016 | 0.005 | 0.831 | |||||

| 4. Extraversion | 0.548 ** | 0.335 ** | 0.030 | 0.752 | ||||

| 5. Openness | 0.090 | 0.075 | −0.068 | 0.135 * | 0.729 | |||

| 6. Interpersonal Relationship | 0.674 ** | 0.460 ** | 0.051 | 0.614 ** | 0.094 | 0.760 | ||

| 7. Entrepreneurial Self-efficacy | 0.632 ** | 0.507 ** | −0.033 | 0.636 ** | 0.175 ** | 0.712 ** | 0.828 | |

| 8. Entrepreneurial Intention | 0.728 ** | 0.497 ** | 0.018 | 0.677 ** | 0.084 | 0.821 ** | 0.792 ** | 0.780 |

| Mean | 2.951 | 2.443 | 3.145 | 2.927 | 2.890 | 2.703 | 2.896 | 2.585 |

| SD | 0.796 | 0.688 | 0.859 | 0.725 | 0.719 | 0.720 | 0.782 | 0.805 |

| Mediating Effect | 95% CI |

|---|---|

| ES → EI | [0.002, 0.156] |

| C → EI | [0.038, 0.283] |

| A → EI | [−0.085, 0.008] |

| E → EI | [0.050, 0.422] |

| O → EI | [−0.005, 0.079] |

| IR → EI | [0.008, 0.226] |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mei, H.; Ma, Z.; Jiao, S.; Chen, X.; Lv, X.; Zhan, Z. The Sustainable Personality in Entrepreneurship: The Relationship between Big Six Personality, Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy, and Entrepreneurial Intention in the Chinese Context. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1649. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9091649

Mei H, Ma Z, Jiao S, Chen X, Lv X, Zhan Z. The Sustainable Personality in Entrepreneurship: The Relationship between Big Six Personality, Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy, and Entrepreneurial Intention in the Chinese Context. Sustainability. 2017; 9(9):1649. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9091649

Chicago/Turabian StyleMei, Hu, Zicheng Ma, Shiwen Jiao, Xiaoyu Chen, Xinyue Lv, and Zehui Zhan. 2017. "The Sustainable Personality in Entrepreneurship: The Relationship between Big Six Personality, Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy, and Entrepreneurial Intention in the Chinese Context" Sustainability 9, no. 9: 1649. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9091649

APA StyleMei, H., Ma, Z., Jiao, S., Chen, X., Lv, X., & Zhan, Z. (2017). The Sustainable Personality in Entrepreneurship: The Relationship between Big Six Personality, Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy, and Entrepreneurial Intention in the Chinese Context. Sustainability, 9(9), 1649. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9091649