Abstract

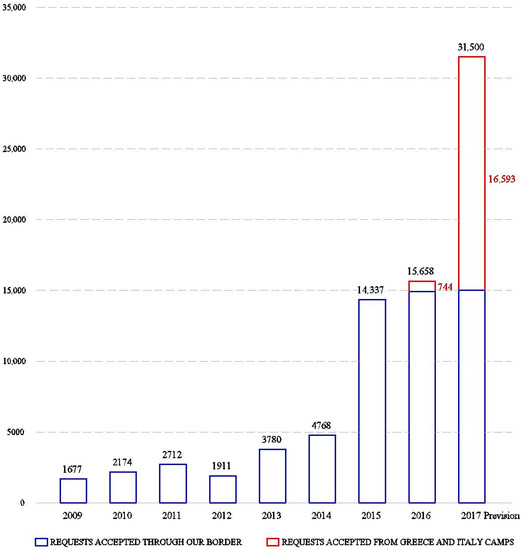

The migration crisis affecting Europe since the war in Syria began is the greatest challenge facing our continent since the Second World War. In the last three years, the number of applicants for international protection in Spain has grown exponentially. Our refugee system has been unable to scale up its supply at the same rate and 20,000 requests have accumulated without response. In addition, the EU has set up a mechanism to relocate 160,000 asylum seekers from Greece and Italy in the rest of the member states (hotspot approach). Of the 17,337 refugees Spain pledged to offer asylum before September 2017, only 744 have been received so far. This article analyzes the strategy the Spanish government has followed to increase the housing capacity of our refugee system. The main conclusion drawn from this case study is that the strategy of expanding supply based on outsourcing the refugee system via subsidies to NGOs is ineffective and, therefore, unsustainable. If the Spanish government wants to solve this problem it will have to launch a program to build new public refugee centers in the short to medium term. This article develops recommendations for the sustainable planning of this plan in the construction system (prefabrication) and in terms of the need to set minimum standards for the centers.

1. Introduction

Everyone has the right to seek and to enjoy in other countries asylum from persecution (Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Article 14.1). However, neither the Refugee Convention (Geneva 1951) nor its additional Protocol (New York 1967) nor any other standard of international law deals with how this should be done. It is the responsibility of sovereign states to regulate based on the obligations acquired at the international level as included in the Spanish Constitution of 1978 (art. 149.1.2). In this way, both the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (adopted in September 2015) [1] and the New Urban Agenda (adopted in December 2016, which sets a new global standard for sustainable urban development) [2] specifically recognize, in their 29th and 28th bullet points, respectively, refugees as actors and subjects of sustainable development and make leaders responsible for the achievement of its objectives, by establishing measures that help migrants, refugees and IDPs make positive contributions to societies “at the global, regional, national, subnational and local levels”.

There is today a clear consensus that migration contributes to the development of countries of origin and destination. The New Urban Agenda states that “although the movement of large populations into towns and cities poses a variety of challenges, it can also bring significant social, economic and cultural contributions to urban life” (28th bullet point), which obviously impact on the sustainable development of cities. The results of the OCDE project “Interrelations between Public Policies, Migration and Development: Case Studies and Policy Recommendations (IPPMD)” [3], also confirm this statement and evidence that the potential of migration is not yet fully exploited because “policy makers do not sufficiently take migration into account in their policy areas”, in such a way that there is an urgent need “to integrate migration into development strategies, improve co-ordination mechanisms and strengthen international co-operation”.

Despite the existence of an international legislative framework and the interest of international bodies in developing a global refugee policy [4], the way each state advances its internal policy is quite different [5]. Jacobsen [6] argues that multiple political, economic, and social factors may influence the development of national policies that are more or less in line with international recommendations. Betts and Orchard [7] found that, depending on the context, the same international standard may be applied in different ways. Yoo & Koo [8] note how different states continue to prioritize the principle of sovereignty in refugee matters more than with any other global policy, putting forth arguments of national security, cultural integrity, and economic success.

The European Union is not immune to this controversy. Neumayer [9] describes the major variations and lack of alignment among Western European countries as they develop their formal responsibilities towards those pursuing asylum and how the political and economic conditions can result in unjust and discriminatory treatment. Since the Treaty of Amsterdam and the monetary union came into effect in 1999, the EU has been attempting to unify member state criteria on asylum and immigration. In the same year, there was an agreement to create the Common European Asylum System (CEAS), and the right to asylum was included in the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights of 2000 (Article 18).

Despite the attempt to standardize community policies by passing directives, the varying interpretations states have made of their obligations and responsibilities has meant the European Court of Human Rights has had to legally intervene to define the collective responsibility of all of the member states [10].

The Treaty of Lisbon coming into effect in 2009 and the new Treaty of the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) were major drivers to create CEAS with a common asylum procedure and uniform regulations for people with international protection (Article 78 of the TFEU). This serves to ensure minimum benefits in access to jobs, education, healthcare, and accommodations. The Stockholm Program was adopted with this goal and several EC directives on asylum were recast. Directive 2013/33/EU [11], which establishes standards for applicants for international protection, sets the minimum common standards to adequately receive protected people and protection seekers and reach an appropriate standard of living (Art 17.2). This first refugee phase is when seekers are the most vulnerable and accommodations is one of the most important concerns, a cross-cutting issue that touches on social integration and inclusion, health, and employment [12,13]. If sufficient institutional support is lacking, seekers may end up in overcrowded houses or sleeping on the street. Their lack of cultural and language skills means they face enormous difficulties in finding housing [14].

Despite the interest in creating common standards, the directive’s application is quite flexible and allows for different housing methods to make applying it in each country easier, adapting to its circumstances and legislation [15]. This results in an extremely heterogeneous system [16]. First, there is no single benefits model. It may be in kind, though there are different accommodation models, initial reception centers, temporary refugee centers, private homes, apartments, hotels, or other adapted locations. If no accommodation is available, benefits may be provided through economic allowances for rent fixed by the minimum income established at the national level [17]. Second, the reception processes do not have the same structure or set duration. Every state establishes different stages and processes and estimates the time a person will spend in each phase. Third, reception centers or premises are not categorized. Naming is not common and reception centers do not respond to standardized models or specific locations. They may be intended for involuntary detention, control, or return in single or multi-functional buildings. They may be open or closed according to different degrees of freedom. Management and staff have very diverse backgrounds and living conditions inside are very diverse. Consequently, how standards are applied varies widely from one state to the next. On top of this, reception capacity, poorly sized by many states, is insufficient, resulting in an inability to provide proper living standards [18].

The current refugee crisis is an enormous challenge for the European Union. This is not about how to respond to individual asylum requests as laid out in the Dublin System. It is about how to manage the mass influx of displaced persons. The European Commission’s proposal in 2015 to set up distribution quotas to relocate refugees from the most affected states to other member states is not having the expected results [19]. As of 6 December 2016, of the 160,000 asylum seekers agreed to by the member states to be relocated from Italy and Greece, only 1950 have been relocated from Italy and just 6212 from Greece [20].

The failure of the EU’s common policy is prompted by the failure of the different national polices of its member states. Without a coordinated strategy, the system is inefficient and the situation unsustainable.

This article analyzes how the Spanish refugee system operates with respect to housing supply in the first stage, especially the policy developed by the Spanish government, a policy that is not working, to increase the amount of accommodation to assimilate the spikes in demand over the last three years due to the conflict in Syria.

The purpose of this article is to understand the causes behind the failure of these policies and develop recommendations to resolve today’s system meltdown. The study’s limitations should be borne in mind, however, since housing is just one factor in the overall international protection seeker integration and reception system. Several players and different circumstances play a part in how the system operates and exert influence at the same time: political predisposition; request, requirement, and procedure management; massive peak arrivals; reception conditions; social integration services; etc. Although this article focuses on accommodation in the first stage of reception as a key factor in seekers’ future integration, any future reform will have to contemplate the system globally.

The incredibly high percentage of denials for requests registered in the Spanish refugee system until 2009 was one of the reasons behind the creation of our current asylum law [21], since transforming the European directive—four years after the fact—with procedures in force at the time [22] on application processing. In an analysis included in the request for European funds for the refugees [23], the Ministry of Labor expressed the need to increase the number of places that our refugee system offered in 2007 for the first integration phase as well as to have a reserve on hand to respond to a potential massive influx of displaced people. The current meltdown of the refugee system has been denounced by some of the NGOs that participate in its operation [24,25] and by other NGOs outside of our management system [26]. Regarding accommodations, the existing literature on the Spanish reception system is fundamentally descriptive and has been drafted by the stakeholders that manage it. The organization Aida (Asylum Information Database), coordinated by the ECRE (European Council on Refugees), has been releasing annual reports since 2013 on asylum procedures and reception conditions regarding housing for several EU countries. The first report on Spain [27] in 2016 was drafted by one of the NGOs that manages our reception system, ACCEM. The European Commission, through the EMN (European Migration Network), has released a report [28] on the characteristics or standards for reception centers that analyzes the lack of uniform minimum reception conditions at the European level. This report does not assess how member states’ reception systems work and uses information culled from a questionnaire completed by each of the member states.

This report is thought-provoking in that it brings together the practices applied in standardized situations as well as the exceptional measures adopted by different member countries to handle high-pressure situations (see Tables S1 and S2 in the Supplementary Materials) not just relating to the kind and quality of the facilities but also to how they are managed.

The report also underlines best practice in exceptional measures, prevention strategies, how to have an emergency plan and enough of a buffer capacity, mitigation strategies, how to have an early warning mechanism to monitor capacity, speeding up the decision-making process, having a flexible budget to deal with unexpected situations, and response strategies to scale up capacity and the number of facilities. The system’s efficiency will depend on a balance between the applicant flow through the reception system and the long humanitarian view.

However, according to the European Council on Refugees and Exiles (ECRE) [18], many of the member states’ reception systems are far from fulfilling the Reception Conditions Directive, so that respect for the right to live with dignity cannot be guaranteed as stipulated in the Charter of the EU. Overcrowding in reception centers, a low quality of basic material conditions or destitution during the asylum procedure are serious concerns, especially in the case of vulnerable persons with special needs.

The ECRE also points out that, although the Directive and the Dublin III Regulation restrict the placement of applicants for international protection in detention centers, as a measure of last resort and under special conditions, the majority of states members have detention premises. These are either in special centers, transit zones, police stations, or in prisons, and do not always offer the conditions necessary to safeguard human dignity; they are sometimes overcrowded, long-term destinations, and the detainees have very restricted freedom of movement.

The situation in the emergency camps in Greece and Italy is precarious after asylum seekers have been blocked from continuing to the northern European states [29], and tens of thousands of people have been trapped without access to asylum procedures and refugee protection due to the ineffectiveness of the reception systems in Europe.

Even so, according to Human Rights Watch, the EU Commission Action Plan published in December 2016 recommended a return policy under the assumption that Turkey was a safe country, that they expand detention on the Greek islands, and curb appeal rights [30].

Our reception system has a mixed offering of housing, with public centers and centers managed by NGOs. The strategy followed by the Spanish government to increase the supply of accommodations over the last few years in the first reception stage was based exclusively on increasing places managed by NGOs by raising their subsidies. In this article we critically analyze that strategy and conclude that it is ineffective and unsustainable. As a direct result, today at least 60% of seekers with the right to asylum cannot access housing due to a lack of places; more than 20,000 seekers are waiting for a response to their request, and more than 16,000 refugees from camps in Greece and Italy that Spain pledged to receive—a modest effort in comparison to other European countries—have not been able to reach our country.

To alleviate this bottleneck, we propose a change in policy that includes planning and rolling out a public accommodations program able to cover today’s peaks in demand—including our European commitments—and to scale back to adapt to lower demand in the future. Proper planning should include quantitative (volume to build) and qualitative (minimum standards) estimates for operation, a full end-to-end life cycle study (manufacture, assembly, disassembly, recycling), execution time frame, expense control, etc.

Our hypothesis is that industrialized construction could offer a shelter solution able to leverage the possibilities offered by industrial production methods to cover enormous demand in the least amount of time possible. The efficiency of industrialized systems considerably reduces manufacturing times with respect to traditional building methods, and those systems can mass produce [31]. Despite a slightly negative perception of prefabrication caused by poor practices, lack of knowledge, or lack of awareness [32], the truth is that industrialized construction has the ability to offer excellent conditions of quality, comfort, and durability [33,34], so long as technical viability and production capacity [35] and the sustainability of the process in all of its economic, social, cultural, environmental, and institutional facets are taken into account [36,37].

2. Methods

We are going to use the case study as our methodological research tool to analyze the policies developed by the central Spanish government to provide accommodations for international protection seekers in the first stage of the integration and reception process, especially the strategy developed by the central administration to increase the supply of lodgings to cover the major increase in demand over the past three years. Case studies are a particularly important and useful research tool when analyzing public policy.

We will assess the period spanning the approval of the Treaty of Lisbon, which aims for a common European policy, and the approval of the Spanish law on asylum in effect today, that is from 2009 till the end of 2016, the last year for which final data are available. This is an external assessment not participated in by any of the actors that intervene in the Spanish reception system. It is an ex-post assessment since it will evaluate the effects of the policies once the abovementioned period has finished. The purpose of this assessment is to determine the progress made in these policies’ goals. If our retrospective analysis concludes that the reception system goals have not been met, or only partially, we can recommend that these policies change or propose alternatives to improve the situation [38].

To correctly assess our case study, we need to clearly define beforehand what the goals of the policies we are going to assess are, how we are going to measure progress made towards those goals, and what information sources we are going to use in the process.

2.1. Goals of the Spanish Reception System for International Protection Seekers

The goal of the Common European Asylum System (CEAS) in the first stage is to standardize national legal frameworks by adopting common minimum regulations, materialized in directives related to asylum procedures [22], requirements for recognition [39], and reception conditions [40]. The second stage of CEAS aims to achieve a shared policy, more than just common regulations [41]. These changes materialized in new directives [11,42,43] that replace the initial mandates and must be transferred into member states’ national regulations. Directive 2013/33/EU, laying down standards for the reception of applicants for international protection, establishes that member states must guarantee the following: housing and food, medical and psychological care, schooling for minors, measures to maintain family unity, and other measures for the most vulnerable groups. This directive has not been adapted to our internal law, however, and, as stated by the ombudsman’s report [44] (p. 87): “The reception directive is fully applicable although it has not been added to internal law.”

The law on right to asylum in Spain [21] is a transposition of the first phase of the CEAS. As pointed out by María Valles [45], the law was published after Spain was ordered to transpose the European directives making up the first stage of the CEAS [22,38,39].

Regarding the applicant reception conditions, the law establishes in Article 30 that “all those people seeking international protection, provided that they lack economic resources, will be given the social services, and reception needed to ensure their basic needs are attended decently” [21] (p. 15). Article 31 specifies that reception of applicants for international protection “will be carried out mainly through the competent Ministry’s own centers and those non-governmental organizations centers that are subsided” [21] (p. 16).

Legislation, statutes, and regulations governing internal functioning, benefits, features, and legal framework for the abovementioned reception centers have not yet been developed despite being announced by the asylum law as well as the regulations of the law on foreigners’ rights and freedoms in Spain [46], which governs reception centers for aliens in Spain. This means that the previous specific regulation on Refugees’ Reception Centers [47] and the basic statutes of those centers [48] are still in force.

The reception and integration system for applicants and benefits of international protection in Spain is defined by the competent ministry (Ministry of Employment and Social Security, MEYSS) through a management manual [49] that specifies its goal—that recipients gradually gain independence—and its structure. It has three phases:

- First phase: reception (six months). In reception centers or facilities: The aim is to cover the refugees’ basic needs and help them gain the skills to enjoy an independent life once they leave the center. Includes housing and maintenance, social intervention, psychological care, training, interpretation and translation, and legal assistance.

- Second phase: integration (six months). Aims to promote the refugee’s autonomy, independence, and integration. Preferably in the same province they were received. Mainly carried out with social intervention and aid.

- Third phase: autonomy (six months). Carried out through sporadic economic support in certain areas.

The system includes a prior phase to assess needs and direct the applicant to the abovementioned reception system if needed. This prior phase begins with a request for international protection. If the request goes through the usual channels, the applicant may receive subsidies to stay up to 30 days in provisional accommodations (hotel, hostel, etc.) until they can be referred to a reception center from the first phase. There is also a second route: a request from one of the two Temporary Immigrant Residences (CETI) in Ceuta or Melilla. Until 2015, the administration maintained that the CETI were resources like reception centers (first phase of the reception system) but, as recognized by the ombudsman’s report, “the situation of these centers means they cannot be considered an adequate resource to lodge and attend to asylum seekers” [44] (p. 91). The last report on asylum in Spain by Amnesty International [26] (p. 27) describes the CETIs as a “limbo in the reception system,” which fail to guarantee refugees’ rights included in the European reception directive. Today the CETI are described on the official website of the Ministry they report to (MEYSS) as, “provisional reception devices whose aim is to offer basic social benefits and services to asylum seekers and immigrants” [50].They are not, then, part of the reception system; they are prior to it.

Summing up, the main goal of the Spanish reception system for international protection seekers is to receive, integrate, and achieve the independence of 100% of applicants for international protection, as specified in Article 3 (scope) of directive 2013/33/EU on the standards for receiving international protection seekers. “This Directive shall apply to all third-country nationals and stateless persons who make an application for international protection on the territory”.

2.2. Goal Measurement and Assessment

Our analysis aims to measure progress made towards attaining those goals. The key performance indicators we will design will measure the percentage of applicants for international protection with the right to enter the reception system who actually benefit from the system. The Spanish reception and integration system begins with the reception centers, in which a key first phase for future integration takes place since it guarantees the rights of refugees to the social services and housing that national and European legislation recognizes to be in line with sustainable development objectives, and in particular regarding the social pillar of sustainability, since “[s]ocial equity programs include neighborhood planning, anti-gang programs, affordable housing provisions, homeless prevention programs, etc.” [51].

For the first phase (reception), a free space must be available in the existing reception centers. The second (integration) and the third phase (independence) are based almost exclusively on economic aid for beneficiaries. The reception, integration, and independence process only begins if the seeker can enter one of the centers where the first phase takes place.

We aim to measure the effectiveness of the Spanish reception system and not its efficiency. This is an assessment in terms of policy compliance, which does not include costs [52]. Indirectly, we also measure the sustainability of the system, as it has been proven that social program operation is more socially sustainable when effective [53].

Immigration policies in Europe are designed at the European and the national levels. Variations between the common policy and the priorities that each of the member states have may vary by a wide margin. In 2007–2013, for instance, Europe as a whole invested 1820 million euros in border control and 700 million in refugee care: a ratio of approximately 1 to 3. In that period, Spain invested 289 million euros in border control and only 9.3 million in refugee care: a ratio of approximately 1 to 30 [54]. In the case of budgets that directly affect the Spanish reception system’s funding, the EU co-financed 75 to 90% (through the ERF in 2007–2013 or the AMIF in 2014–2020). There is clearly money available but when the time comes to decide how and where to invest those funds, political factors override economic ones [55].

To be able to measure what percentage of seekers with the right to enter the reception system have actually entered it, we need to know the number of available spaces in the first reception phase and the number of seekers. If the seekers do not enter in this first phase, they have a high possibility of ending up in overcrowded housing or homeless since this group of immigrants is especially vulnerable. If we are able to design an indicator that measures what percentage of seekers does not enter the reception system in the first phase, this KPI will implicitly measure the system in terms of the social and the economic pillars of sustainable development: a high percentage of seekers who do not enter the first phase will negatively affect the attainment of several Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) especially linked to the social pillar: SDG 1: “End poverty”, SDG 3: “Good health and well-being”, and SDG 10: “Reduced inequalities”. Moreover, an inadequate basis for refugees’ integration into the host society will also have a negative impact on the attainment of SDGs, directly connected to the economic pillar: SDG 11: “Sustainable cities and communities” and SDG 8: “Decent work and economic growth”. On the contrary, this indicator with a high percentage of seekers who enter the reception system in this first phase means there is a positive impact on social and economic sustainability, as it has been proven that the recognition and participation of citizens in society are significant for both social and economic sustainability [56,57].

Even if the meaning and associated objectives of the social pillar of sustainability may be vague [51,56,58,59,60,61], there is a general consensus regarding the kinds of social concepts and policy objectives that this social pillar should include: housing, education, health, economic self-sufficiency, and social inclusion [55,56,57,58,59,62]. An effective refugee reception system, one that is sustainable, should comprise these policy objectives.

2.3. Information Sources

Since there are many stakeholders (European as well as local, regional, and national Spanish authorities and NGOs) different kinds of literature have been gathered and analyzed, including primary sources like legislative documents (EU directives and national legislation), official statistics (EU and Spanish government data, statistics, and reports), and secondary sources like reports drafted by NGOs participating in the Spanish system to receive and integrate applicants for international protection .

Information on the number of applicants for international protection, requests accepted, requests resolved, the number resolved for or against, those not resolved, and the accumulated number of requests still unresolved has been collected directly from Eurostat, the European Statistics Office, since after Legislation n° 862/2007 [63] on community statistics in the area of migration and international protection went into effect, EU member countries must send data monthly, quarterly, and annually.

The information on the number of spaces offered by the Spanish system has been gathered from reports published annually by the NGOs that work in the Spanish reception system. To obtain some unpublished data on how places and occupation are managed in reception centers, information was requested, and later received, from the relevant ministry, the Spanish Ministry of Employment and Social Security, through the Bureau of Immigrant Integration (Directorate General of Migrations, General Secretariat of Immigration and Emigration) [64].

2.4. The Study’s Limitations

The study is limited to Spain and we do not intend, nor is it possible, to extract general conclusions for the rest of Europe. The fact that refugee reception policies in the EU are so heterogeneous makes it nearly impossible to generalize the results. That being said, we think that some aspects of the study can transcend the Spanish case and be important in future cases on refugee reception policies as lessons learned have the potential to be applied to reception systems with saturation problems like Spain’s and can be part of a first attempt at developing common KPIs and standardized methods to be able to measure and compare the pressure the different EU reception systems are under.

3. Case Study: Management and Evolution of the Spanish Reception System

3.1. Increase in International Protection Applications in the Last Three Years

The evolution of the Spanish reception system from the time the new law came into effect in 2009 until today can be seen in Table 1, which includes applicants, acceptance, and number of resolutions (in favor or against) as well as the increase in unresolved applications (difference between accepted and resolved applications) and the total: 2009 closed with 3280 unresolved applications [65] and 2016 with 20,365 [66].

Table 1.

Own table with Eurostat data (applicants [67], resolved in favor or against [68], accumulated to end of 2016 [66]), CEAR report 2015 [24] (p. 224, requests accepted), Annual Report on Migration and International Protection Statistics. Spain 2009 [65] (accumulated to end of 2009).

3.2. Management of the Spanish Reception System

The Spanish reception system’s management is mixed. As explained by Article 31 of the asylum law, the itineraries described can be developed:

- “through the competent ministry’s centers” [21] (p. 16). The Public Administration, through the Ministry of Employment and Social Security (MEYSS), manages the entire itinerary and has a network of its own reception centers (Refugee Reception Centers, CARs), created in 1989 [47] for reception’s first phase.

- “non-governmental organizations’ subsidized centers” (NGOs) [21] (p. 16), recognized by the state to cover the entire itinerary. These organizations manage the whole program and have their own housing for the first reception phase.

3.3. Supply of Places in Reception Centers in the First Phase since 2009

Table 2 offers a view of how the supply of places in reception centers in Spain from 2009 to 2016 has evolved.

Table 2.

Own table with ACCEM [69,70,71,72,73,74], CEAR [75,76,77,78,79], SRC [80,81] and Aida (Asylum Information Database) data [27] (pp. 43–44).

Over the last 15 years, the number of places offered by the four public reception centers (CARs) has not changed: a total of 420 places with 82 in Alcobendas, 122 in Mislata, 96 in Sevilla, and 96 in Vallecas [27] (p. 44).

The number of places offered by reception centers managed by NGOs varies and adjusts to demand. Only three organizations (the Spanish Red Cross, SRC, the Spanish Refugee Aid Commission, CEAR, and the Spanish Catholic Migration Commission Association, ACCEM) had been authorized by the Spanish government to manage the reception system.

As shown, the supply of places stayed practically the same from 2009 to 2014 (around 1000 places a year). There have been enormous increases over the last two years.

In 2016, management of the Spanish reception system underwent a major change: the number of NGOs that could manage the reception system was increased. The three NGOs that had managed it from the beginning (ACCEM, CEAR, and SRC) expanded to 10 with the addition of La Merced, Consorcio de Entidades para la Acción Integral con Migrantes (CEPAIM, or Consortium of Bodies for Comprehensive Migrant Action), Dianova, Asociación para la Promoción e Inserción Profesional (Association for Promotion and Employability), and Asociación Cívica de Ayuda Mutua (APIP-ACAM, Civic Mutual Aid Association), Red Acoge, Pro Vivienda, and Adoratrices. The last seven offered 747 places in 2016.

3.4. Features and Control of Reception Centers

The aim of directive 2003/9 [41], on standards for the reception of asylum seekers, was to guarantee minimum standards within the EU, but the description of reception centers (Article 14) is very generic and fails to specify clear qualitative or quantitative standards. The directive that replaces it [11] is even more vague in this area, making it difficult to reach any kind of uniformity in the EU. This was confirmed by the recent study by the EMN for the European Commission [28] that highlights the absence of minimum quality standards in reception conditions in EU member states and even the absence of uniform practice within some states.

When discussing the characteristics of reception centers (the centers themselves or the activities they undertake) included in Spanish regulations, a distinction must be made between public centers and those run by NGOs.

All the information on public Refugee Reception Centers (CARs) is available on the Spanish government’s transparency portal [82]. Of note is the Refugee Reception Center Services Charter [83], which establishes the services the CARs provide: all of those listed in the Management Manual for our reception system [50]. A series of quality standards for these centers are also listed and there are key performance indicators to confirm that these standards have been met. The last assessment is posted on the transparency portal [84]. The successful operation of these public centers was recently confirmed by the ombudsman for its study on “Asylum in Spain” [44].

Reception centers managed by NGOs vary widely since there is no regulation governing what they should be like or what services they should provide. One may find collective reception centers in which refugees may share space with other types of beneficiaries (depending on the different vulnerable groups attended by the NGOs: immigrants, the elderly, etc.) and shared apartments around major Spanish cities leased by the NGO with subsidies received from the state. Management of non-public reception centers is not regulated by any manual [85], which includes the services that should be provided in the centers.

3.5. Increased Budget Earmarked for the Spanish Reception System

The Spanish government’s annual budget for the reception and integration system for seekers and beneficiaries of international protection is divided into several items under the immigration chapter of the budget assigned to the General Secretariat of Immigration and Emigration under the Ministry of Employment and Social Security (MEYSS). Spending on these items in 2007–2013 has been practically constant. Since 2013, as shown in Table 3, all items have grown.

Table 3.

Own table with Spanish government data: 2013 [86], 2014 [87], 2015 [88], 2016 [89], and 2017 [90].

The three main items are:

- (a)

- Maintenance, resizing, and reinforcement of the reception and integration system for seekers and beneficiaries of international protection that included last year (2016) and spending forecasts for 2017 for the Program to Resettle and Relocate Persons Susceptible to International Protection, which includes European aid to receive Spain’s quota of refugees from Italian and Greek camps. That partially explains the incredible upsurge (2522.3%) in this item in 2016 and 2017 in comparison to 2015.

- (b)

- Resources earmarked to maintain reception centers (CARs) and temporary immigrant residences (CETIs).

- (c)

- Subsidies for NGOs that participate in the reception system.

This item had to be expanded exceptionally in 2015 [91] and 2016 [92] so the initial budget of 13.8 million euros was increased with two new subsidies, the first approved in 2015 for 13 million euros and the second in 2016 for 74 million euros.

3.6. Forecast for 2017

The migration crisis affecting Europe since the war in Syria is the greatest challenge facing our continent since the Second World War. The mechanism the EU set up to relocate 160,000 asylum seekers from Greece and Italy to the rest of the member states—the hotspot approach [93,94,95]—is not working. Of the 17,337 applicants for international protection Spain pledged to receive before the agreement’s end (in September 2017), only 744 have been relocated.

Some of the reasons the hotspots are not working were pointed out in the “Building on the Lessons Learned to Make Relocation Schemes Work More Effectively” report [96]. One of the main problems with the hotspots is that the pace at which relocations happen is set by each of the member states [97] (p. 5). Every three months, each member state is required to provide information about how many places it has prepared for relocations to happen. This has allowed Spain, and other countries, to offer places at a clearly insufficient pace. In a year and a half our country has offered 900 places (of which only 744 have arrived, 600 [97] from Greece and 144 [98] from Italy), which means that if we would like to comply with our obligations in the next six months 16,593 refugees from camps in Greece and Italy would arrive in Spain.

Apart from this one-time item, the Spanish government forecasts that the number of international protection applications in 2017 will be similar to 2016 [90], meaning the total number of applicants could exceed 30,000 by the end of 2017 (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Requests accepted in the period 2009–2017.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Selection and Use of KPIs

The study by EMN in 2014 for the EU [28] recommends that, to measure the pressure the EU country reception systems are under, data on the total number of international protection seekers who have the right to enter reception centers in a certain year should be gathered, and that to measure the responsiveness of the system the total number of seekers who actually entered the reception centers that year must be known. Although that information appears easy to obtain, the study concludes that it is so complex it makes it difficult to compare different reception systems at the European level. The recommendation is to develop common KPIs and standardized methods to be able to measure pressure and responsiveness.

Our first KPI will measure the system’s effectiveness (and sustainability) and is supported by the same two variables recommended by EMN: international protection seekers with the right to enter the system and international protection seekers that actually enter the system.

With our second indicator we will measure the changes that have occurred in the Spanish reception system’s management.

4.2. Effectiveness of the Reception System

4.2.1. How Many Seekers Have the Right to Enter the Spanish Reception System Every Year? (P)

An international protection applicant’s entrance in a reception center is governed, so long as the corresponding regulation goes undeveloped, by the “Procedure to manage places in reception and integration programs for seekers and beneficiaries of international protection, of the statute of the stateless and vulnerable immigrants” [99]. According to that document, beneficiaries of places in public (CAR) and outsourced NGO housing in the first phase of the Spanish reception system will be people applying for and benefiting from international protection, applicants and beneficiaries of the statute of the stateless, and people under the temporary protection regime.

Not all seekers, however, have the right to submit an application. With Spain’s law as it is today, those applications whose study is not Spain’s responsibility, those that are reiterations of previous applications, or those presented by nationals from another EU country may be denied acceptance. Once the file of accepted requests has been resolved, if the resolution is favorable (column 5, Table 1: In Favor), beneficiaries will stay in the center. If it is not (column 6, Table 1: Against), they have a month to leave.

Requests accepted for processing must be responded to in a maximum of six months (three in urgent cases). However, as the ombudsman reported in 2015 [100], delays (of up to three years in some cases) are the norm. These delays have meant that there were 20,365 unresolved resolutions at the close of 2016.

All applicants for international protection whose request has been accepted and resolved in favor have the right to enter the system, as well as those whose request has not yet been resolved.

P = Pressure on the reception system: total n of seekers with the right to enter the system. Rf = Annual requests with in favor resolutions (column 5, Table 1). Ra = Accumulated annual requests (accumulated requests: column 8, Table 1).

P = Rf + Ra

4.2.2. How Many Seekers Enter the Spanish Reception System Every Year? (C)

The public reception centers (CARs) and those managed by NGOs supply annual information on the spaces they offer but not on how many people fill those spaces every year. Since there is no information published on the number of people that use these spaces each year, we asked the Ministry of Employment and Social Security for information on the relationship between the number of spaces offered and the number of people that use them in a year. MEYSS provided us with information [64] for the last two years (2015 and 2016), which had the most requests: 10,898 people (3151 in 2015 and 7747 in 2016 passed through the 5699 spaces offered (1595 in 2015 and 4104 in 2016, see Table 2), or an average of 1.91 people per space per year. Keeping in mind that the maximum stay in a reception center is six months (nine in cases of extreme vulnerability), we can conclude from this data that applicants for international protection who enter the reception centers stay for the maximum time allowed. We are going to set a value of two people per space per year (higher than the actual numbers, biasing it in favor of a positive assessment for the system) with centers at 100% capacity to calculate the international protection seekers that actually entered the Spanish reception system each year.

NP = Number of total spaces offered each year (column 7, Table 2).

C = NP × 2

4.2.3. KPI 1 (I1)

Indicator 1 (I1, Table 4) measures the evolution during the period studied of the relationship between the number of people that actually enter the Spanish reception system (C) and the number of people with the right to enter that system (P).

I1 = C/P

Table 4.

Indicator 1 (I1).

The value 1 of this indicator means that the number of seekers that enter the reception system is equal to the number of requests accepted. Values over 1 indicate that the system has more capacity than demand; values less than 1 show in what percentage the system is incapable of increasing capacity at the pace of demand.

The difference between the number of people with the right to enter (P) and the number of people that actually enter (C) gives us the annual number of people (P–C) who have the right but do not enter the reception system.

4.3. Evolution and Changes in the Spanish Reception System

The Spanish reception system has not changed its policies or its structure since today’s asylum law was passed in 2009. To respond to the exponential growth in international protection seekers, the government has launched two special programs, one in 2015 [93] and one in 2016 [94], which consisted of approving subsidies so NGOs could increase their offering of spaces for the first phase of the reception system.

These initiatives have not brought about any legislative change since the Spanish asylum law does not specify what the proportion has to be between the spaces managed by the public administration (CARs) and those managed by NGOs. Nor does it specify or describe what those reception centers for the first phase of the system should be like.

4.3.1. KPI 2 (I2)

With this indicator (I2, Table 5) we measure the evolution during the period studied of the relationship between the number of spaces managed by the public administration through CARs (Npp) and the number of spaces managed by NGOs.

Npp = No. of public spaces offered by the system (column 2, Table 2). T: Total no. of spaces (CARs + NGOs) offered by the system (column 7, Table 2).

I2 = Npp/T

Table 5.

Indicator 2 (I2).

4.3.2. KPI 3 (I3)

This indicator (I3, Table 6) measures the evolution during the period studied of the relationship between the number of spaces offered in collective reception centers (Npc) and the number of spaces offered in rented apartments.

Table 6.

Indicator 3 (I3).

At the start of the period studied, in 2009, all of the public spaces and 70% of the spaces managed by NGOs were in collective reception centers. The exponential increase in seekers has meant that the ramping up of the offering of spaces has been achieved exclusively through rented apartments.

Npc = No. of spaces offered in collective centers. T = Total no. of spaces (CARs + NGOs) offered by the system (column 7, Table 2).

I3 = Npc/T

4.4. Forecast and Simulation Model

4.4.1. Forecast for 2017

September 2017 is the deadline for refugees coming from Italy and Greece to arrive in Spain (17,337) as an exceptional influx. In 2016, 744 refugees arrived from Italian and Greek camps. Therefore, there are 16,593 yet to come. Adding this exceptional influx to the standard demand, which is estimated to be similar to 2016’s (15,755 requests), the number of seekers would be over 30,000 (see Figure 1). If the reception system operates like it did in 2016, with 10,250 cases resolved and 5408 accumulated, and with the same percentage of resolutions in favor (6855), the pressure on the reception system would be determined by the addition of: the standard requests resolved in favor (6855) + the exceptional requests made by Italian and Greek refugees (16,593) + the requests accumulated at the end of 2016 (20,365) + the requests that will accumulate at the end of 2017 (5408), which makes a total of 49,221 persons (see Table 7).

Table 7.

Forecast indicator 1 (I1) 2017.

4.4.2. Simulation Model: The Influence of the Time to Resolve Requests on the Effectiveness of the Spanish Reception System

In order to know the influence of the time to resolve the requests on the effectiveness of the Spanish reception system in the period covered, we have developed a simulation model whereby the requests are resolved in six months, as established by the law.

Since the annual increase of the accumulated requests is equal to the difference between the accepted and the resolved requests, if the system’s management were able to resolve all the requests, the number of accepted requests would be equal to those resolved.

IA = Annual increase (column 7, Table 1 and Table 8); Ra = Requests accepted (column 3, Table 1 and Table 8); Rr = Requests resolved (column 4, Table 1 and Table 8).

IA = Ra − Rr

IA = 0; Ra = Rr

Table 8.

Simulation from Table 1.

On the assumption that in 2013 the management system had worked properly, and knowing that that year there were only 1302 accumulated requests and an increase of 1410 (3780 accepted − 2370 resolved), if that year it had been possible to resolve 5082 requests (1302 + 2370 + 1410), the accumulated requests would have been reduced to 0. From that moment on we can assume that the management system functions properly (see Table 8).

As the simulation model shows (see Table 9), when recalculating the management system with the new figures, its effectiveness increases significantly (I1 = 0.71 in 2015, compared to the real figure 0.2, and I1 = 0.78 in 2016, compared to the real figure, 0.3). This means that delays in resolving requests have a decisive impact on the effectiveness of the system.

Table 9.

Simulation of indicator 1 (I1).

However, even with a perfect system management it would not be possible to absorb the additional demand of 16,000 new refugees coming from Greece and Italy in 2017. On the contrary, the forecasted effectiveness drops by 0.31 (that is to say, seven out of 10 seekers would be excluded from the system).

4.5. Analysis of Results

4.5.1. KPI I1

The Spanish reception system was designed from its inception to receive approximately 2000 people: 1000 offered between the CAR (420 spaces) and the NGOs (500 or 600, depending on the demand). In 2000–2008, after the current asylum law came into effect, the average number of international protection seekers was over 6000 a year. In this period, the percentage of applications not accepted oscillated between 41% and 77%, with an overall average of 62%. This extremely high percentage of non-acceptance reduced the number of seekers with the right to enter the reception system from more than 6000 (average total requests over the period) to 2500 (average accepted requests in the period).

One of the main consequences of today’s asylum law is that now there are fewer reasons to reject applications. This has meant that, from 2009 to today, the percentage of applications not accepted has fallen drastically with respect to the previous period, oscillating between 1% and 5%, with an overall average throughout the period of just under 3% [101].

The main reason for the ineffectiveness at the start of the period (0.54 in 2009) was the number of requests that piled up without resolution (3280). Since then and until 2012 the trend for the I1 indicator has been to grow due to the favorable situation in that period (fewer than 3000 annual requests) and the policy of resolving more than 80% of requests as Against. In 2012, effectiveness was over 1 and almost cleared the backlogged requests, down to 1302. Since 2013, there has been a huge increase in the number of international protection seekers with the right to enter the reception system. This is due to the increase in requests from the Syrian conflict and to the gigantic increase in the percentage of requests resolved in favor (60% in 2013–2016). The trend has been reversed and the system, designed for 2000 applicants, reduced its effectiveness in 2013 (more than 3000 people with the right to enter I1 = 0.55) and in 2014 (more than 5000 people with the right to enter I1 = 0.35). The Spanish government has attempted to handle the spectacular increase in seekers in 2015 and 2016 (around 15,000 a year) by launching two special NGO subsidy programs for them to increase their offering of spaces: 13.8 million euros in 2015 and 74 million in 2016.

The impact of the first program on the downward trend that began in 2013 was not observable (2015: I1 = 0.20; only2 out of 10 entered the system) and the impact of the second program was very limited in relative terms (2016: I1 = 0.30; only three out of 10 entered the system) and has not prevented the number of people with the right to enter our reception system yet who have been left out of it from increasing from 12,787 in 2015 to 19,012 in 2016.

4.5.2. I2 and I3 KPIs

As can be seen in Table 4, for almost the entire period (2009–2014) public centers managed 40–50% of the spaces; those percentages have been the same since they first opened in 1989. The programs rolled out in 2015 and 2016 have had a direct impact on this ratio and have reduced public management down to today’s 10%.

For most of this period (2009–2014) the initial rate the system was designed with was maintained: 75–85% in collective centers, to which general cases were derived, and 15–25% in centers in apartments to provide more personalized attention for exceptional cases. The spike in demand meant that its increase was only through rented apartments and has completely changed the face of the system: now uniform care is in the minority (20% of collective centers in 2016) and 80% of cases are resolved as exceptional.

4.5.3. Forecast and Simulation Model

As can be seen in Table 7, our reception system’s present capacity (8208 places) is insufficient to meet the more than 15,000 standard requests forecasted for 2017 plus the more than 20,000 accumulated requests and the more than 16,000 seekers coming from Italy and Greece. In 2017, more than 35,000 persons will be excluded from our reception system, and effectiveness will drop to 0.24.

As can be seen in Table 9, if the management system had operated as established by law, its effectiveness would be above 0.7 (seven seekers out of 10 would enter the system). This means that the increased capacity of the reception system developed by the government would be reasonable and effective. However, even if the management system operated perfectly, the arrival in 2017 of more than 16,000 seekers coming from Italy and Greece would have collapsed it (see Table 9, I1 = 0.31 in the outlook for 2017).

5. Conclusions

The migratory crisis in Europe has meant a notable increase in the number of international protection seekers with the right to enter the Spanish reception system. The strategy developed by the Spanish government to increase the system’s capacity is ineffective and, therefore, unsustainable. It is ineffective because the impact of the programs launched in 2015 and 2016, based exclusively on increasing spaces that NGOs manage, has not had the desired impact: the percentage of seekers with the right to enter the system who have been left out of it is the highest in the period (80% and 70%).

Because it is ineffective, it is also unsustainable in terms of the social pillars of sustainable development, but also from the economic point of view, because these percentages can be read on the personal scale as 12,787 people in 2015 and 19,012 in 2016 who were not cared for by the system. The majority of one of the most vulnerable immigrant communities was left to their own devices and the almost sure fate of marginality and poverty, which has two specific negative consequences directly related to sustainable development, firstly because reception centers not only provide shelter and food, but also social intervention, psychological care, training, legal advice, interpretation, and translation, tools needed for undertaking the second (integration) and the third (autonomy) phases, without which no sustainable integration is possible. Secondly, because, as is stated in the New Urban Agenda for Sustainable Development, a proper basis for the refugees’ integration into the civic and working life of the host societies is an asset that “can bring significant social, economic and cultural contributions to urban life” [2].

The measures to respond to increased demand over the last two years, besides directly not working, have changed the management model in our reception system. It has gone from one made up mostly of collective centers supported by a reduced percentage of centers in rented apartments to a system in which collective centers are the minority; from being a system composed of almost 50% public centers and subsidized centers managed by NGOs to being a system almost exclusively managed by NGOs; from being a system managed by the state with the collaboration of three NGOs with more than 20 years’ experience in the area to being a system managed by more than 10 NGOS (seven of which have absolutely no experience).

These changes have not come about as the result of a debate between private and public management or between the private and the collective: They are the unplanned product of extending exceptional measures supported exclusively by outsourcing the management of our reception system. Meanwhile the regulations, statutes, and standards that govern the internal operation, benefits, features, and legal regime of the reception centers included in the asylum law go undeveloped. This lack of definition, combined with an increase in the actors who manage the reception system, causes a lack of uniformity in the system and makes it harder to control.

The possibility of increasing the capacity of our reception system through intensifying subsidies to NGOs is showing signs of nearing its end. NGOs are facing enormous problems with increasing their network of apartments (in 2016, the SRC and ACCEM made public calls to encourage citizens to offer their apartments up for lease), since refugees are seen as a risky population by private landlords [12]; and the result has not only been clearly insufficient (747 new places a year from the seven new NGOs combined, some of which have offered a ludicrous number of places: 2, 21, or 31) but it has also uncovered innumerable problems derived from these organizations’ lack of experience (Dianova amassed 18 complaints for putting international protection seekers in the same centers as drug addicts [102]).

The end of the road of outsourcing spaces to increase capacity in the reception system, combined with the certainty that our reception system will experience demand increases in coming years (pressure continues through the usual channels and 16,000 refugees will come from Italy and Greece), forces us to draw the conclusion that the only possible way to increase the system’s effectiveness is for the central administration to undertake an increase in our reception capacity.

Only the state—the central government—has enough political, organizational, and economic power and capacity to develop and coordinate a program with the rest of the regional and local administrations to build reception centers like the one needed today. Some major Spanish city governments (Barcelona, Madrid, Valencia, etc.) are driving initiatives to receive refugees. Despite the political willingness of those city halls and their importance in the area of local administration, these initiatives have been shown to be insufficient (for instance, Madrid, whose town hall has only been able to offer 42 apartments to Syrian refugees).

Delays in resolving international protection requests explain the present collapse of the Spanish system. Any modification of the system will have to lead to the improvement of the management system as the basis for reducing the number of unresolved applications and to avoid new accumulations in the future.

If we continue with our current policies, and do not adopt short-term exceptional measures to increase the system’s capacity, the Spanish government has to assume: First, that by the end of 2017, 70% of applicants for international protection by ordinary procedure will not enter the system; and second, that Spain is refusing to receive refugees from camps in Italy and Greece, despite its commitment to the EU.

The question is: How can the Spanish government respond to an urgent need in a timely manner and in line with the Sustainable Development Agenda and Sustainable Development Goals?

6. Recommendations

6.1. Strategy and Planning

The construction and commissioning of thousands of new reception places by the public administration should be planned correctly. In any shelter solution, the strategy must attempt to avoid making common mistakes and to support aid projects and programs to guarantee an appropriate, coordinated, and sustainable response [36]. The response must be planned beforehand [103], establishing a previous framework for the work to base programs and projects in a coordinated, contextualized, and realistic way. The goals and responsibilities of all the stakeholders, applicable laws, codes, and standards, and the quality, cost, and duration of the housing should all be clearly defined to provide an appropriate solution on time [104].

Adequate standards must be defined before starting construction. Undoubtedly, having those standards at the European level would be preferable. The abovementioned EMN report [28] demonstrate the lack of uniformity of reception centers around Europe. UNHCR is the competent body that should have led the definition of minimum parameters and standards for reception centers for EU member countries (just like IASC, the Inter Agency Standing Committee, does in the case of natural disasters). Since those standards do not exist, Spain has to set its own parameters like Germany has, although they vary depending on the Land. The standards should be adapted to the reality of the context, in all of its aspects, be they physical, political, economic, social, cultural, or legal [105]. The absence of adequate planning can be a plan’s fatal error, like in the last emergency housing program in Spain—prefabricated housing in Lorca in response to the earthquake in 2011—which failed because standards far removed from our context were applied, the same that IASC had laid down for the 2010 earthquake in Haiti [106].

6.2. Prefabrication

All of the prior conditions—construction volume, tight deadlines for execution, expense containment, etc.—lead us to prefab building solutions. The industrialization of construction, known as “prefabrication” or “prefab,” is a streamlined and automated building process, including design, production, manufacture, and management using industrial organization methods and mass production techniques with a high degree of technological involvement to increase productivity and product quality [107].

The prefabricated manufacturing system is not associated with a specific building typology, either collective or individual; with this system it is possible to build both collective and dispersal centers.

Since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, industrialized manufacturing methods have been developed to pragmatically respond to urgent needs created by unusual circumstances [108]. Industrialized construction could offer a shelter solution able to leverage on the possibilities afforded by industrial production methods to cover enormous demand in the least amount of time possible [31]. Prefabrication is an adequate option to temporarily cover one-time demand like in the case of responding to certain shortages or needs that in the long term will call for a more durable solution. As a provisional response, it is a resource used especially for medical and hospital care facilities, schools, or religious centers, military camps, or camps for displaced workers, vacation establishments, and offices and services on a work site [32]. This is the preferred system throughout Europe for building reception centers, mainly in Germany [109]. They may be designed to be easily disassembled once their use has come to an end, as well as comply with portability conditions so they can be set up in a new location [32].

The relative success of temporary post-war programs meant that in the following decades prefabricated housing was seen as a particularly useful solution in accommodations for refugees and displaced people with urgent housing needs [110].

However, most of these programs have proven themselves to be inadequate and unsustainable due to failed strategy, misunderstandings about the beneficiaries’ needs, and mistaken concepts about conditions and available resources [111]. To avoid making the same mistakes, industrialization must be understood as requiring a high degree of coordination and adequate planning before the fact to increase control over costs, time frames, and volume of production, as well as over product quality, ensuring that the process is reliable and predictable [34].

Industrialized construction should not aim for a one-size-fits-all response [112]; it should adapt to each context and situation. The different needs of each project should be assessed correctly in conjunction with the advantages and disadvantages of the different solutions.

The capacity of Spanish industry to prefabricate in normal market conditions and to organize itself and face unusual situations with their resources should be kept in mind. To assess these capacities, an up-to-date and detailed market study and a prior analysis must be on hand before decisions can be made [113].

Prefabricated construction of reception centers could obtain the following advantages:

- Faster delivery. Execution times are shortened since much of the work and preassembly can be done simultaneously. Since construction is carried out off-site, choosing the site and developing it can be planned at the same time as construction is going on, making execution time frames much shorter than in traditional construction.

- Expense containment. With correct planning, transportation expenses can be cut back operating in local areas with smaller radii of action. Costs can also be reduced by anticipating decisions and more efficiently taking advantage of resources [114]. Prior planning and standardization allow establishing tighter production costs: economies of scale and the stability of material prices not subject to variations due to exceptional demand can be leveraged. Deviations from initial budgets are much less noticeable than in traditional construction.

- Positive impact on the local economy. Although evidently a reception center program like the one proposed implies a major initial outlay of funds, in the medium term the impact on the local economy can be substantial. Shelter, understood as a process, can result in economic benefits for the community and strengthen its development. This may be at the local level, as amortized capital [115] through reuse, sale, or lease of the units [116], or as part of a macroeconomic strategy focused on developing the construction industry [117].

- Control over the life cycle. From the environmental point of view, the way in which shelters can be maintained, repaired, implemented, and adapted to future changes and how they can be taken down at the end of their life cycle must be taken into consideration [118]. Materials, components, and systems must be designed flexibly enough to be able to be replaced, adapted to changes, or, in the end, recovered to go back to the productive cycle, incorporating new concepts like “from birth to the grave,” “from cradle to cradle,” or “Design for Disassembly” [119].

Other aspects related to later integration and autonomy phases, as possible later studies, should be considered. The lack of a legitimate social housing policy that guarantees access to decent accommodations should be studied, not just for refugees but also for the most disadvantaged and vulnerable sectors of the population at risk of exclusion today.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/9/8/1446/s1. Table S1: Standard reception strategies; Table S2: Strategies for increasing the capacity of reception.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the Higher Technical School of Engineering and Industrial Design (ETSIDI), Technical University of Madrid (UPM) for covering part of the costs to publish in open access.

Author Contributions

The paper was produced with close collaboration between the authors Pablo Bris and Félix Bendito. Pablo Bris drafted the initial version of the paper, with Félix Bendito providing a detailed description and analysis of all the aspects of the paper. The primary research at the Spanish refugee system was designed and conducted by Pablo Bris, with input from Félix Bendito. The ideas and themes in the paper come from joint discussions and analysis of the context, literature review and evaluation of the primary data from the case study by both Pablo Bris and Félix Bendito. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- United Nations (UN). Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, Resolution Adopted by the General Assembly on 25 September, 2015. Available online: http://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/RES/70/1&Lang=E (accessed on 4 April 2017).

- UN. New Urban Agenda, Resolution Adopted by the General Assembly on 23 December 2016. Available online: http://habitat3.org/wp-content/uploads/New-Urban-Agenda-GA-Adopted-68th-Plenary-N1646655-E.pdf (accessed on 25 May 2017).

- OECD. Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) 2017 Report (Interrelations between Public Policies, Migration and Development); OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, S.D. Global Refugee Policy: Varying Perspectives, Unanswered Questions; Background Paper for the Refugee Studies Centre 30th Anniversary Conference. 2012. Available online: http://www.rsc.ox.ac.uk/files/publications/other/dp-global-refugee-policy-conference.pdf (accessed on 7 August 2015).

- Milner, J. Introduction: Understanding Global Refugee Policy. J. Refug. Stud. 2014, 27, 477–494. Available online: http://jrs.oxfordjournals.org/content/early/2014/10/30/jrs.feu032.full.pdf?keytype=ref%2520&ijkey=CcbhCsDFpOK0mIB (accessed on 31 May 2017). [CrossRef]

- Jacobsen, K. Factors Influencing the Policy Responses of Host Governments to Mass Refugee Influxes. Int. Migr. Rev. 1996, 30, 655–678. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2547631?seq=2#page_scan_tab_contents (accessed on 31 May 2017). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Betts, A.; Orchard, P. Introduction: The normative Institutionalization—Implementation Gap. In Implementation in World Politics: How International Norms Change Practice; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014; pp. 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Yoo, E.; Koo, J.-W. Love Thy Neighbor: Explaining Asylum Seeking and Hosting, 1982–2008. Int. J. Comp. Sociol. 2014, 55, 45–72. Available online: http://cos.sagepub.com/content/55/1/45.abstrac (accessed on 31 May 2017). [CrossRef]

- Neumayer, E. Asylum Recognition Rates in Western Europe—Their Determinants, Variation and Lack of Convergence. J. Confl. Resolut. 2005, 49, 43–66. Available online: http://www.lse.ac.uk/geographyAndEnvironment/whosWho/profiles/neumayer/pdf/Article%20in%20Journal%20of%20Conflict%20Resolution%20%28Asylum%29.pdf (accessed on 31 May 2017). [CrossRef]

- Guild, E. The Europeanization of Europe’s Asylum Policy. Int. J. Refug. Law 2006, 18, 630–651. Available online: http://ijrl.oxfordjournals.org/content/18/3-4/630.full (accessed on 31 May 2017). [CrossRef]

- European Parliament, Council of the European Union. Eur-lex, Directive 2013/33/EU of 26 June 2013 on Laydown standards for the reception of applicants for international protection (recast). Off. J. Eur. Union 2013, L180, 96–116. Available online: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32013L0033&from=en (accessed on 4 April 2017).

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). A New Beginning. Refugee Integration in Europe. Available online: http://www.unhcr.org/protection/operations/52403d389/new-beginning-refugee-integration-europe.html (accessed on 4 April 2017).

- Ager, A.; Strang, A. Indicators of Integration; Home Office Development and Practice Report; Home Office: London, UK, 2004; p. 15. Available online: http://goo.gl/GoRhy9 (accessed on 4 April 2017).

- Garcin, S. Infos Migrations: La Mobilité Résidentielle des Nouveax Migrants. Available online: http://www.immigration.interieur.gouv.fr/content/download/38845/296183/file/IM_21_022011.pdf (accessed on 4 April 2017).

- Poptcheva, E.-M.; Tuchlik, A. Work and Social Welfare for Asylum-Seekers and Refugees. Selected EU Member States. Available online: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/IDAN/2015/572784/EPRS_IDA(2015)572784_EN.pdf (accessed on 4 April 2017).

- STEPS. The Conditions in Centres for Third Country National (Detention Camps, Open Centres as well as Transit Centres and Transit Zones) with a Particular Focus on Provisions and Facilities for Persons with Special Needs in the 25 EU Member States. Available online: http://www.schipholwakes.nl/Europarlement-vr-detentie-EN.pdf (accessed on 4 April 2017).

- Application for Interim Federal Health Program (IFHP). Housing Refugees Report. Available online: http://www.ifhp.org/sites/default/files/staff/IFHP%20Housing%20Refugees%20Report%20-%20final.pdf (accessed on 4 April 2017).

- European Council on Refugees and Exiles (ECRE). Reception and Detention Conditions of Applicants for International Protection in Light of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the EU. Available online: http://www.refworld.org/pdfid/5506a3d44.pdf (accessed on 4 April 2017).

- Bordignon, M.; Moriconi, S. The Case for a Common Refugee Policy. Bruegel. 20 March 2017, p. 13. Available online: http://bruegel.org/2017/03/the-case-for-a-common-european-refugee-policy/ (accessed on 31 May 2017).

- Carrera and Guild. Offshore Processing of Asylum Applications: Out of Sight, out of Mind? CEPS. Available online: https://www.ceps.eu/publications/offshore-processing-asylum-applications-out-sight-out-mind (accessed on 31 May 2017).

- Law 12/2009, of October 30, which regulates the right of asylum and subsidiary protection. Available online: https://www.boe.es/buscar/pdf/2009/BOE-A-2009-17242-consolidado.pdf (accessed on 4 April 2017).

- European Parliament, Council of the European Union. Eur-lex, Council Directive 2005/85/EC of 1 December 2005 on Minimum Standards on Procedures in Member States for Granting and Withdrawing Refugee Status. Off. J. Eur. Union 2005, L326, 13–34. Available online: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2005:326:0013:0034:EN:PDF (accessed on 4 April 2017).

- Spanish Ministry of Labor and Immigration. ERF Multiannual Plan, 2008–2013. General Programme on Solidarity and Management of Migration Flows. Available online: http://extranjeros.empleo.gob.es/es/Fondos_comunitarios/programa_solidaridad/refugiados/pdf/FER_Plan_Plurianual_2008_2013_MTIN.pdf (accessed on 4 April 2017).

- Comisión Española de Ayuda al Refugiado, CEAR (Spanish Refugee Relief Commission). CEAR’s 2015 Report; Las Personas Refugiadas en España y Europa (Refugees in Spain and Europe); CEAR: Madrid, Spain, 2015; Available online: https://www.cear.es/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/Informe-2015-de-CEAR2.pdf (accessed on 4 April 2017).

- Comisión Española de Ayuda al Refugiado, CEAR (Spanish Refugee Relief Commission). CEAR’s 2016 Report; Las Personas Refugiadas en España y Europa (Refugees in Spain and Europe); CEAR: Madrid, Spain, 2016; Available online: https://www.cear.es/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/Informe_CEAR_2016.pdf (accessed on 4 April 2017).

- Amnesty International. El Asilo en España: Un Sistema de Acogida Poco Acogedor (Asylum in Spain: An Unwelcoming Reception); Spanish Section of Amnesty International: Madrid, Spain, 2016; Available online: https://doc.es.amnesty.org/cgi-bin/ai/BRSCGI.exe/Un_sistema_de_acogida_poco_acogedor?CMD=VEROBJ&MLKOB=35286283535 (accessed on 4 April 2017).

- Asylum Information Database (Aida). Country Report: Spain, 2016 Update, Second Report. Available online: http://www.asylumineurope.org/reports/country/spain (accessed on 4 April 2017).

- European Migration Network (EMN). The Organisation of Reception Facilities for Asylum Seeker in Different Member States. European Migration Network Study 2014. Available online: http://emn.ie/files/p_20140207073231EMN%20Organisation%20of%20Reception%20Facilities%20Synthesis%20Report.pdf (accessed on 6 June 2017).

- Reading Researcher Development Programme (RRDP). Life in Limbo. Filling Data Gaps Related to Refugees and Displaced Persons in Greece. Refugees Rights Data Project. Available online: http://refugeerights.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/RRDP_LifeInLimbo.pdf (accessed on 4 April 2017).

- Human Rights Watch (HRW). Greece: A Year of Suffering for Asylum Seekers. EU-Turkey Deal Traps People in Abuse and Denies Them Refuge. Available online: https://www.hrw.org/news/2017/03/15/greece-year-suffering-asylum-seekers (accessed on 4 April 2017).

- Barakat, S. Housing Reconstruction after Conflict and Disaster; Humanitarian Practice Network (HPN), Overseas Development Institute: London, UK, 2003; Available online: http://www.ifrc.org/PageFiles/95751/B.d.01.Housing%20Reconstruction%20After%20Conflict%20And%20Disaste_HPN.pdf (accessed on 4 April 2017).

- Gibb, A. Off-Site Fabrication: Prefabrication, Pre-Assembly and Modularisation; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1999; p. 288. [Google Scholar]

- Stephen Kieran, S.; Timberlake, J. Refabricating Architecture: How Manufacturing Methodologies Are Poised to Transform Building Construction; McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 2003; p. 192. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, R.E. Prefab Architecture: A Guide to Modular Design and Construction; John Wiley & Sons Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2010; p. 366. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, C.; Lizarralde, G.; Johnson, C. Myths and realities of prefabrication for post-disaster reconstruction. In Proceedings of the 4th International i-Rec Conference Building resilience: Achieving effective post-disaster reconstruction, Christchurch, New Zealand, 30 April–2 May 2008; Available online: http://www.resorgs.org.nz/images/stories/pdfs/iRec_2008/postdFinal00004.pdf (accessed on 4 April 2017).

- UNHCR. Global Strategy for Settlement and Shelter. A UNHCR Strategy 2014–2018. Available online: http://www.unhcr.org/530f13aa9.pdf (accessed on 4 April 2017).

- Tavanti, M.; Sfeir-Yunis, A. Human Rights Based Sustainable Development: Essential Frameworks for an Integrated Approach. Int. J. Sustain. Policy Pract. 2013, 8, 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, W.N. Public Policy Analysis: An Introduction; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]