The Future of Sustainable Urbanism: Society-Based, Complexity-Led, and Landscape-Driven

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Aims

- A second element consists of enforced uncertainties. Several sustainability transitions, such as the transition towards a green economy [6] or a low-carbon energy system [7,8] are deliberately enforced by international agreements and national policies. This type of uncertainties will impact the urban system. In order to accommodate these transitions the city itself needs to transform;

- Thirdly, there is uncertainty that stems from being exposed to the aforementioned two elements: exposure to uncertainties. For instance, the urbanisation of the global population continues [9], which means an increasing number of people live in cities. At the same time, most cities worldwide are located in vulnerable, exposed areas [10]. Together, this means that the number of people that will have to deal with uncertainties is rapidly increasing.

1.2. Methods

1.3. Findings

- (1)

- Close cycles at the lowest possible scale;

- (2)

- Build redundancy in the design;

- (3)

- Create anti-fragility;

- (4)

- See citizens as (design) experts;

- (5)

- Use the landscape as the basis for urban growth;

- (6)

- Develop innovative, rule-breaking designs.

1.4. Conclusions

2. Methods

3. Results

3.1. Review of the History of Sustainability in Urbanism

3.2. Review of Eco-Initiatives in the Built Environment

3.2.1. Drivers for Green, or ‘Ecological’, Urbanism

3.2.2. Urban Design Principles

3.2.3. Eco-City Typologies

- Self-reliant cities: intensive internalization of economic en environmental activities, circular metabolism, bioregionalism, and urban autarky;

- Redesigning cities and their regions: planning for compact, energy efficient city regions;

- Externally dependent cities: excessive externalization of environmental cost, open systems, linear metabolism, and buying in additional carrying capacity;

- Fair Share cities: balancing needs and rights equitably with regulated flows of environmental value and compensatory systems;

- The sustainable city, which has a self-sufficient economic, social, and environmental system;

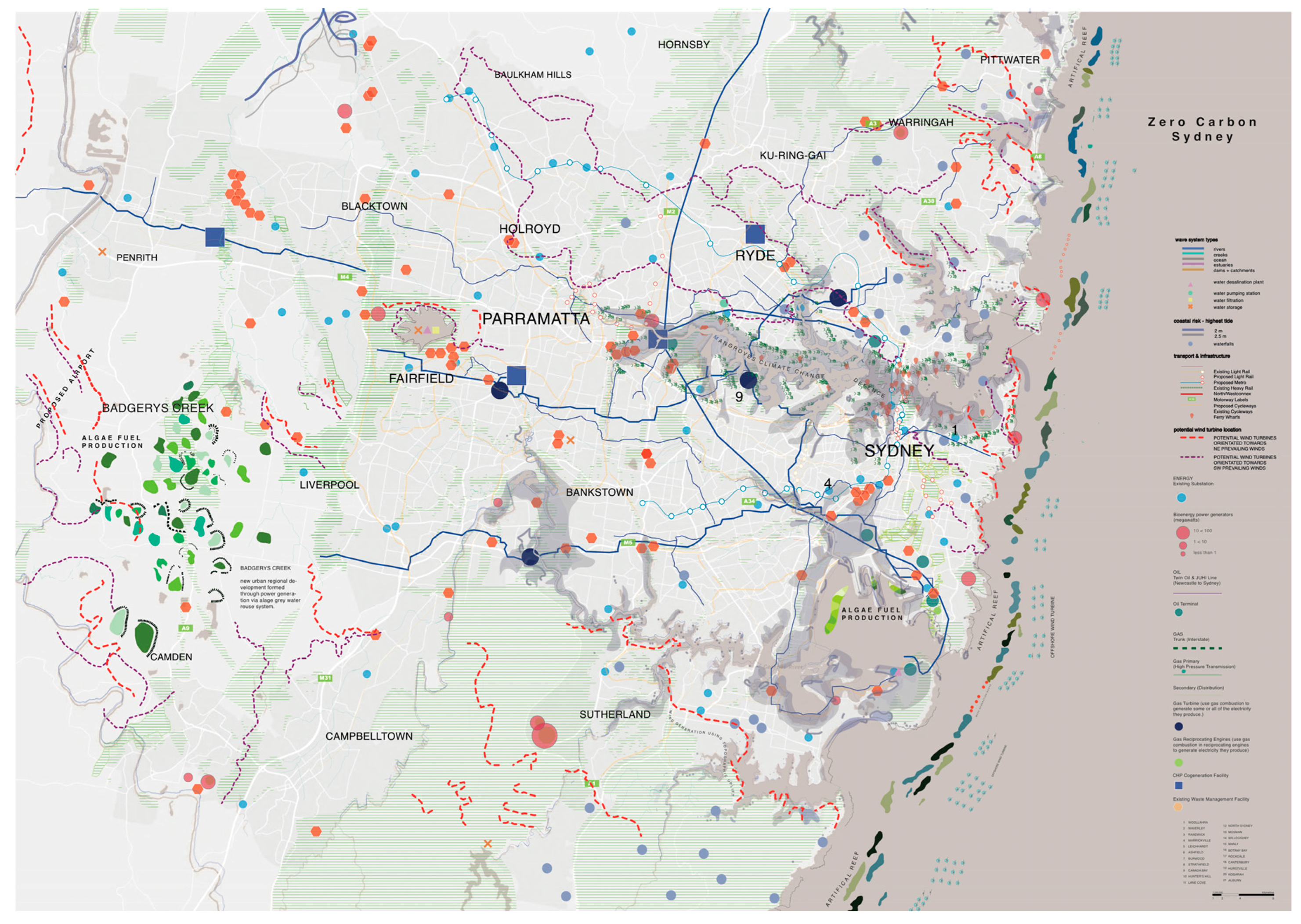

- The low carbon city is minimizing the human-inflicted carbon footprint by reducing or even eliminating the use of non-renewable energy resources;

- The smart city [76], in which investments in human and social capital is coupled with investment in traditional (transport) and modern information and telecommunication infrastructure, generating sustainable economic development and a high quality of life while promoting prudent management of natural resources [77];

- The knowledge city integrates cities that physically and institutionally combine the function of a science park with civic and residential functions [78];

- The resilient city in which a predictive model of urban systems is built through three interconnected components of uncertainty: adaptation, spatial planning, and sustainable urban form (compactness, density, mixed land use, diversity, passive solar, greening, and renewal and utilization) [79], in order to deal with ecological problems, hazards and disasters, and shocks in urban en regional economies, through promoting urban governance and institutions [80];

- The eco-city aims to reconstruct cities in balance with nature, a city built within the principles of living within the means of the environment [81].

- Sustainable development: meet the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs [84];

- Bioregionalism: a region governed by nature not legislature [85];

- Community economic development: communities initiate their own solutions to their common economic problems;

- Appropriate technology: enhance self-reliance of people;

- Social ecology: committed citizenry cutting across class and economic barriers to address dangers;

- Green movement: community self-reliance, quality of life, harmony with nature, and decentralization and diversity [86];

3.2.4. Urban Design Characteristics of Eco-Cities

- Compact mixed use urban form;

- Natural environment permeates the city’s spaces;

- Transit, walking and cycling infrastructure;

- Environmental technologies for water, energy, and waste;

- City centers are human centers, with access other than automobile;

- High quality public realm;

- Legible, permeable, robust varied, rich, visually appropriate, and personalized physical structure;

- Innovation, creativity, and uniqueness create economic performance;

- Visionary planning through ‘debate and decide’.

4. The Future of Sustainable Urbanism

4.1. Principles for Sustainable Urbanism

- Close cycles at the lowest possible scale. When the cycles of water, energy, and materials are closed, no waste streams are produced and the city is clean and has an efficient urban metabolism. The circularity provides abundant opportunities to create economic benefits. However, it is not always technically and financially most feasible to close cycles at the lowest possible scale. As Tillie et al. [94] and Van den Dobbelsteen [95] have pointed out, for energy solutions on different scales, up-scaling from the individual building can also lead to a balanced urban system;

- Create spaces for the unknown. When redundancy becomes a standard part in urban design, the city has the flexibility to ‘host’ unprecedented events. If, for instance, a cyclone hits the city, there is space to temporarily store the accompanying water. Roggema [58] has identified this space as being ‘unplanned’;

- Design anti-fragile spaces. Using this new concept to design places that improve the quality in the city when an event occurs. ‘Ant-fragility is defined as a convex response to a stressor or source of harm (for some range of variation), leading to a positive sensitivity to increase in volatility (or variability, stress, dispersion of outcomes, or uncertainty, what is grouped under the designation “disorder cluster”)’ [65]. Applied in urban environments under stress of climate impacts, anti-fragility is the concept that urban environments become stronger than before through their response to climate events. In urbanism, this concept is ill-researched. However, it could potentially open new design pathways to create urban environments that not only could withstand or bounce back from climate disasters, but, as a result of the hazard, grow stronger;

- Let people own their environment. When residents are part of the design process, they will create ownership over the changes and invest in their environment. Once residents own their environment, they will make sure it is maintained well [96]. The design charrette is a wonderful design method to develop designs in an inclusive way [97].

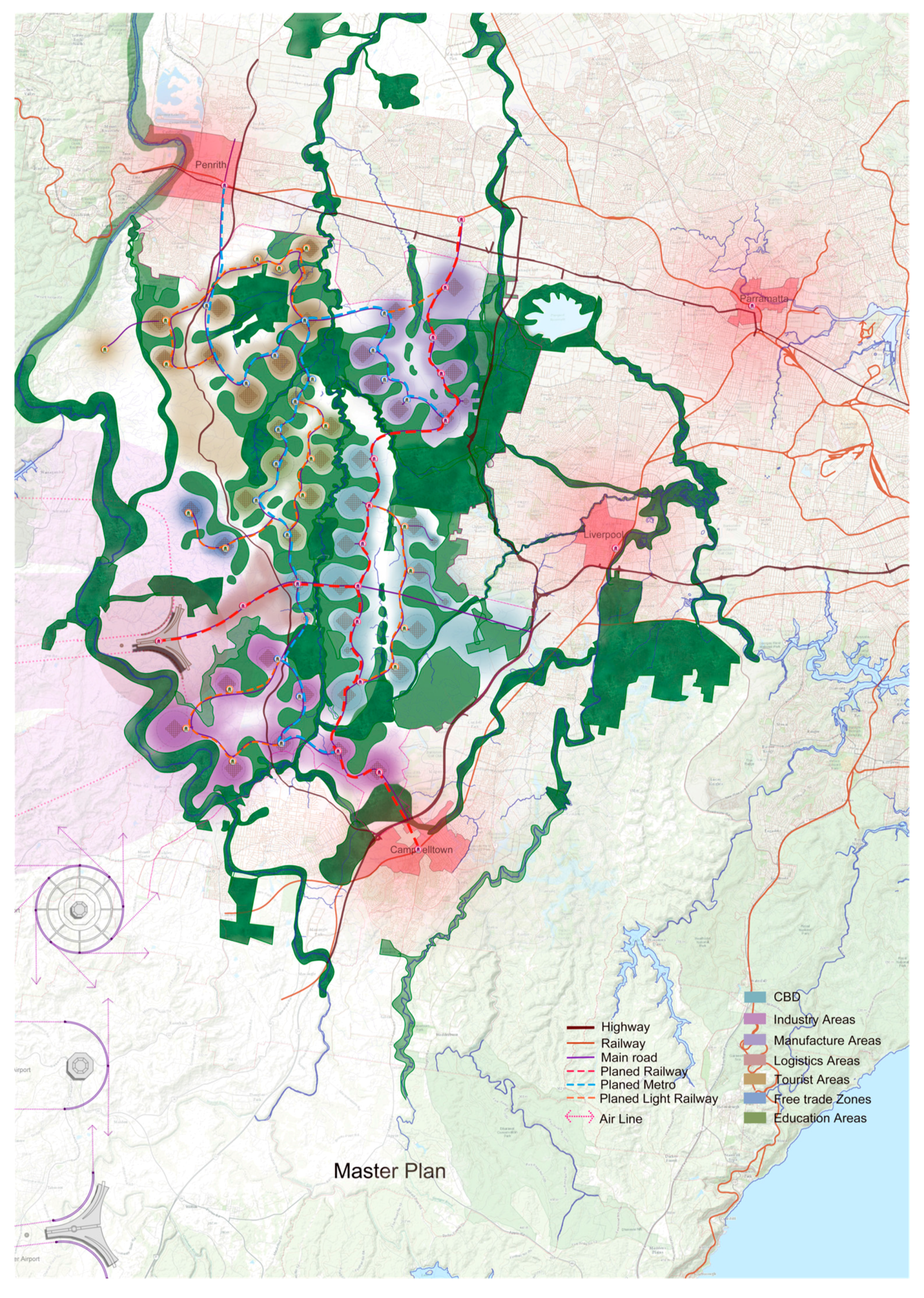

- Use the landscape as the basis for urbanism. Landscape systems, such as the water system, ecology, and soil, create the conditions for urban occupancy. The values in the landscape then will determine the type of urban development. This is contrary to the current situation where the urban development dictates the landscape, e.g., overthrows the existing landscape values to create ordinary residential areas. Even in existing cities, the underlying landscape can be illuminated and brought to the surface to give the city extra ecological qualities.

- Create innovative designs. The current conventions need to be broken if a sustainable city is to be developed. The existing procedures need to be bypassed using creative design approaches. For the development of regional plans, metropolitan spatial visions, district plans, and neighbourhood designs, a sabbatical detour can provide the space to think differently and the time to come up with alternative design propositions. Elements of a sabbatical detour are design competitions, an idea-generating charrette, designers in resident, exhibitions, and many other activities.

4.2. Society Based, Complexity-Led, and Landscape-Driven

4.2.1. Society-Based Urbanism

4.2.2. Complexity-Led Urbanism

4.2.3. Landscape-Driven Design

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report; Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Core Writing Team, Pachauri, R.K., Meyer, L.A., Eds.; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014; p. 151. [Google Scholar]

- Roggema, R. The future of sustainable urbanism: A redefinition. City Territ Archit. 2016, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rittel, H.; Webber, M. Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Policy Sci. 1973, 4, 155–169, Reprinted in Developments in Design Methodology; Cross, N., Ed.; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 1984; pp. 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VROM-raad. De Hype Voorbij, Klimaatverandering als Structureel Ruimtelijk Vraagstuk; advies 060; VROM-raad: Den Haag, The Netherlands, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Commonwealth of Australia. Tackling Wicked Problems; a Public Policy Perspective; Australian government/Australian Public Service Commission: Canberra, Australia, 2007.

- Allen, C.; Clouth, S. A Guidebook to the Green Economy; UNDESA: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Foxon, T.J.; Hammond, G.P.; Pearson, P.J. Developing transition pathways for a low carbon electricity system in the UK. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2010, 77, 1203–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulkeley, H.; Broto, V.C.; Hodson, M.; Marvin, S. (Eds.) Cities and Low Carbon Transitions; Routledge: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. World Urbanization Prospects. The 2007 Revision; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kreimer, A.; Arnold, M.; Carlin, A. (Eds.) Building Safer Cities: The Future of Disaster Risk; The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, B.; Strauss, A. The Discovery of Grounded Theory; Aldine: Chicago, IL, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin, J.; Strauss, A. Basics of Qualitative Research; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Larco, N. Sustainable urban design—A (draft) framework. J. Urban Des. 2016, 21, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girardet, H. The GAIA Atlas of Cities: New Directions for Sustainable Urban Living; Gaia Books Limited: London, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, E. Garden Cities of Tomorrow; S. Sonnenschein & Co., Ltd.: London, UK, 1902. [Google Scholar]

- Wise, E. A gradual awakening: Broadacre city and a new American agrarianism. Berkeley Plan J. 2013, 26, 133–149. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J.-L.; Benton, T. (Eds.) Le Corbusier Le Grand; Phaidon Press Limited: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholls, R.J. Coastal megacities and climate change. GeoJournal 1995, 37, 369–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donatiello, J.E. The world’s population: An encyclopedia of critical issues, crises, and ever-growing countries. Ref. User Serv. Q. 2015, 54, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farr, D. Sustainable Urbanism. Urban Design with Nature; John Wiley and Sons Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Beatley, T. Green Urbanism: Learning from European Cities; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Beatley, T. Biophilic Cities: Integrating Nature into Urban Design and Planning; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Mostafavi, M. Why Ecological Urbanism? Why Now? In Ecological Urbanism; Mostafvai, M., Doherty, G., Eds.; Lars Müller Publishers: Baden, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Waldheim, C. Landscape as Urbanism. In Landscape as Urbanism Reader; Waldheim, C., Ed.; Princeton Architectural Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 21–34. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, P.; Beatley, T.; Boyer, T. Resilient Cities; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Duany, A.; Speck, J.; Lydon, M. The Smart Growth Manual; McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Haas, T. Sustainable Urbanism and Beyond; Rizzoli: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kriens, I.; Klaasen, I.T.; Rooij, R.M. De Kern van Ruimtelijke Planning and Strategie. Ruimte en Maatschappij; Technische Universiteit Delft: Delft, The Netherlands, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, M.H. Vitruvius. The Ten Books on Architecture; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA; Oxford University Press: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerie van Landbouw Natuurbeheer en Visserij. Nota Landschap; Ministerie van LNV: Den Haag, The Netherlands, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Gunder, M. Fake it until you make it, and then…. Plan Theory 2011, 10, 201–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, L. The Tall Office Building Artistically Considered; Lippincott’s Monthly Magazine: New York, NY, USA, 1896. [Google Scholar]

- McHarg, I.L. Design with Nature; Natural History Press: New York, NY, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Van Schaick, J.; Klaasen, I.T. The Dutch layers approach to spatial planning and design: A fruitful planning tool or a temporary phenomenon? Eur. Plan. Stud. 2011, 19, 1775–1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priemus, H. The network approach: Dutch spatial planning between substratum and infrastructure networks. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2007, 15, 667–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sijmons, D. Het Casco-Concept, een Benaderingswijze Voor de Landschapsplanning; Ministerie van LNV, directie NBLF: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Tjallingii, S.P. Ecopolis: Strategies for Ecologically Sound Urban Development; Backhuys Publishers: Leiden, The Netherlands, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Tjallingii, S. Planning with water and traffic networks. Carrying structures of the urban landscape. Res. Urban Ser. 2015, 3, 57–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teeuw, P. Duurzame Ideeën % DCBA Methodiek: Ambitie Stellen Volgens de Viervarianten-Methode; AEneas, Boxtel: Hertogenbosch, The Netherlands, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Sanders, E.B.N.; Stappers, P.J. Co-creation and the new landscape of design. CoDesign 2008, 4, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roggema, R.; Martin, J.; Arcari, P.; Clune, S.; Horne, R. Design-Led Decision Support Process and Engagement; VCCCAR: Melbourne, Australia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Roggema, R.; Vos, L.; Martin, J. Resourcing local communities for climate adaptive designs in Victoria, Australia. Chin. J. Popul. Resour. Manag. 2014, 12, 210–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roggema, R.; Martin, J.; Vos, L. Governance of Climate Adaptation in Australia: Design Charrettes as Creative Tool for Participatory Action Research. In Action Research for Climate Change Adaptation: Developing and Applying Knowledge for Governance; Van Buuren, A., Eshuis, J., van Vliet, M., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; pp. 92–108. [Google Scholar]

- Surowiecki, J. The Wisdom of Crowds: Why the Many Are Smarter Than the Few; Little Brown: Boston, MA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Tomásek, W. Die Stadt als Oekosystem; Űberlegungen zum Vorentwurf Landschafsplan Köln (The city as ecosystem; considerations about the scheme of the Landscape design Cologne). Landsch. Stadt 1979, 11, 51–60. [Google Scholar]

- Wolman, A. The metabolism of cities. Sci. Am. 1965, 213, 179–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newman, P.W.G. Sustainability and cities: Extending the metabolism model. Landsc. Urban Plan. 1999, 44, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, C.; Cuddihy, J.; Engel-Yan, J. The changing metabolism of cities. J. Ind. Ecol. 2007, 11, 43–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, C.; Pincetl, S.; Bunje, P. The study of urban metabolism and its applications to urban planning and design. Environ. Pollut. 2010, 159, 1965–1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shafie, F.A.; Dasimah, O.; Karuppannanb, S. Urban metabolism: A research methodology in urban planning and environmental assessment. In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Research Methodology for Built Environment and Engineering, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 17–18 December 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kristinsson, J. Integrated Sustainable Design; Van den Dobbelsteen, A., Ed.; Delft Digital Press: Delft, The Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Prigogine, Y.; Stengers, I. Order out of Chaos. Man’s New Dialogue with Nature; Bantam Books Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell Waldrop, M. Complexity. The Emerging Science at the Edge of Order and Chaos; Simon and Schuster Paperbacks: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Kauffman, S.A. The Origin of Order: Self-Organisation and Selection in Evolution; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Kauffman, S. At Home in the Universe; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J.; Stewart, I. The Collapse of Chaos: Discovering Simplicity in a Complex World; Penguin Group Ltd.: London, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Portugali, J. Self-Organisation and the City; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Roggema, R. Swarm Planning: The Development of a Spatial Planning Methodology to Deal with Climate Adaptation. Ph.D. Thesis, Delft University of Technology, Delft, The Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Waterman, R.E. Integrated Coastal Policy via Building with Nature. Ph.D. Thesis, Delft University of Technology, Delft, The Netherlands, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, C. Eco-acupuncture: Designing and facilitating pathways for urban transformation, for a resilient low-carbon future. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 50, 189–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, C.; Biggs, C.; Trudgeon, M. Eco-acupuncture and greenaissance: Designing urban interventions for resilient post-carbonaceous futures, from Victoria (Australia) to Florence (Italy). In Proceedings of the State of Australian Cities Conference, Sydney, Australia, 26–29 November 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Roggema, R. Towards enhanced resilience in city design: A proposition. Land 2014, 3, 460–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roggema, R. Three urbanisms in one city: Accommodating the paces of change. J. Environ. Prot. 2015, 6, 946–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, J.S. The Agile City. Building Well-Being and Wealth in an Era of Climate Change; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Taleb, N.N. Antifragile—Things That Gain from Disorder; Random House: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, C. Landscape Urbanism and New Urbanism: A View of the Debate. J. Urban Des. 2015, 20, 303–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, M.E. Green Cities Urban Growth and the Environment; Brookings: Washington, DC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann, S. Green Urbanism: Formulating a Series of Holistic Principles. Sapiens 2010, 3, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, U. Risk Society. Towards a New Modernity; Sage: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Joss, S. Eco-cities: The mainstreaming of urban sustainability—Key characteristics and driving forces. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. Plan. 2011, 6, 268–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapoport, E.; Vernay, A.-L. Defining the Eco-City: A Discursive Approach; International Ecocities Initiative; University of Westminster: London, UK, 2014; Available online: https://www.westminster.ac.uk/file/42096/download (accessed on 15 May 2017).

- Van den Dobbelsteen, A.; Jansen, S.; van Timmeren, A.; Roggema, R. Energy Potential Mapping—A systematic approach to sustainable regional planning based on climate change, local potentials and exergy. In Proceedings of the CIB World Congress, Cape Town, Africa, 14–18 May 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann, S. The Principles of Green Urbanism. Transforming the City for Sustainability; Earthscan: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Haughton, G. Developing sustainable urban development models. Cities 1997, 14, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jong, M.; Joss, S.; Schraven, D.; Zhan, C.; Weinen, M. Sustainable-smart-resilient-low carbon-eco-knowledge cities; making sense of a multitude of concepts promoting sustainable urbanization. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 109, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Townsend, A.M. Smart Cities. Big Data, Civic Hackers, and the Quest for a New Utopia; W.W. Norton Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Caragliu, A.; Del Bo, C.; Nijkamp, P. Smart Cities in Europe. J. Urban Technol. 2011, 18, 65–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yigitcanlar, T.; Velibeyogly, K.; Baum, S. (Eds.) Knowledge-Based Urban Development: Planning and Applications in the Information Era; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Jabareen, Y. Planning the resilient city: Concepts and strategies for coping with climate change and environmental risk. Cities 2013, 31, 220–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leichenko, R. Climate change and urban resilience. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2011, 3, 164–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Register, R. Ecocity Berkeley: Building Cities for a Healthy Future; North Atlantic Books: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Ecobuilders (Undated). What Is an Ecocity? Available online: http://www.ecocitybuidlers.org/what-is-an-ecocity/ (accessed on 12 April 2017).

- Roselund, M. Dimensions of the eco-city. Cities 1997, 14, 197–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED). Our Common Future; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Sale, K. Dwellers in the Land: The Bioregional Vision; Sierra Club: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Capra, F.; Spretnak, C. Green Politics: The Global Promise; Dutton: New York, NY, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Van Timmeren, A.; Henriquez, L.; Reynolds, A. Ubikquity & the Illuminated City; TU Delft: Delft, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Joss, S.; Cowley, R.; Tomozeiu, D. Towards the ‘ubiquitous eco-city’: An analysis of the internationalisation of eco-city policy and practice. Urban Res. Pract. 2013, 6, 54–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howarth, L. Ecopolis, the Emergence of Regenerative Cities. The Ecologist. Available online: http://www.theecologist.org/News/news_analysis/2000416/ecopolis_the_emergence_of_regenerative_cities.html (accessed on 12 April 2017).

- Boselli, F. Cities Must Be Regenerative. But What Kind of Regeneration Are We Actually Talking About? World Future Council. 2016. Available online: https://www.worldfuturecouncil.org/cities-must-regenerative-kind-regeneration-actually-talking/ (accessed on 12 April 2017).

- ReGen Villages Holding. REGENVILLAGES. 2016. Available online: http://www.regenvillages.com (accessed on 18 May 2017).

- Kenworthy, J.R. The eco-city: ten key transport and planning dimensions for sustainable city development. Environ. Urban. 2006, 18, 67–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bioregional. The BedZED Story. The UK’s First Large Scale, Mixed-Use Eco-Village; Bioregional Development Group: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Tillie, N.; Van Den Dobbelsteen, A.; Doepel, D.; Joubert, M.; De Jager, W.; Mayenburg, D. Towards CO2 Neutral Urban Planning: Presenting the Rotterdam Energy Approach and Planning (REAP). J. Green Build. 2009, 4, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Dobbelsteen, A.; Wisse, K.; Doepel, D.; Tillie, N. REAP2-new concepts for the exchange of heat in cities. In Proceedings of the 4th CIB Conference Smart and Sustainable Built Environments, Sao Paulo, Brazil, 27–29 June 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Western Australian Planning Commission. Designing out Crime. Planning Guidelines; State of Western Australia: Perth, Australia, 2009.

- Roggema, R. The Design Charrette: Ways to Envision Sustainable Futures; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands; Heidelberg, Germany; London, UK, 2013; p. 335. [Google Scholar]

- Portugali, J. Complexity theory as a link between space and place. Environ. Plan. A 2006, 38, 647–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roggema, R.; Thomas, L. Critical mapping for transformational cities. In Proceedings of the Passive and Low Energy Architecture (PLEA 2017), Edinburgh, UK, 3–5 July 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Roggema, R.; King, L.; van den Dobbelsteen, A. Towards Zero-Carbon metropolitan regions: The example of Sydney. Energies 2017. forthcoming. [Google Scholar]

| Phase | Concept | Principle | Overarching |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aesthetics | |||

| Rationalism | |||

| Negotiatism | Co-design Co-creation | People Innovative design | Society |

| Emergensim | Interventions | Innovative design | |

| Ecosystem based | Metabolism | Close cycles | Complexity |

| Antifragility | Antifragile | ||

| Emergenism | Interventions | Space for the unknown | Landscape |

| Conceptualism | Layers Approach Casco Concept Two Network Strategy | Landscape as basis |

| Phase | Perspective | Means | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1980’s | Grassroots, visions | Normative | Environmental standards |

| 1992–early 2000 | Local and national experimentation | Regulatory, standardised | Standardized models |

| 2000–present | Global expansion, mainstreaming | Innovation, conceptual | Technology and design |

| Principle | Aspects |

|---|---|

| Climate and context | Site’s climate conditions, orientation and compactness, landscape, topography and resources, maintain complexity, own methods, and tailored strategies for every district take advantage of local potentials |

| Renewable energy | Availability of local renewables (energy potentials [72], city district as a producer of energy, distributed energy supply though decentralized systems, local storage, smart grid, energy efficiency, co-gen, cascading exergy principles, intelligent building management. |

| Zero-waste | Circular, closed loop, turn waste into resource, reduce, reuse, recycle, and compost waste to produce energy, remanufacturing, balance in nitrogen cycle |

| Water | Reduce consumption, efficiency of use, water quality, aquatic habitats, city as a water catchment area, storm water retention and flood management, rainwater harvesting, local treatment of waste-water, safe water and sanitation, algae, integrated urban water cycle planning, black and grey water treatment, dual water systems, drought resistant crops |

| Landscape and urban biodiversity | Local biodiversity, habitat, ecology, wildlife rehabilitation, forest conservation, urban vegetation, inner city gardens and urban agriculture, mitigating Urban Heat island effects, tree planting, restoring stream and river banks, de-pavements, carbon storage |

| Sustainable transport and good public space in compact poly-centric cities | Public space network, post fossil mobility, access to public transport, safe bicycle ways, smart vehicles, walkeable city, streetscapes for healthy active lifestyle, medium dense housing typologies |

| Local materials with less embodied energy | Advanced materials technology, local materials, modular prefabrication, lightweight structures, disassembly, resource recovery, reuse building components |

| Density and retrofitting existing districts | Densification of the city, mixed use urban infill, retrofitting inefficient building stock, better land use planning, public space upgrading, adaptive reuse, city above the city, self-sufficiency |

| Passive design for buildings and districts | Low energy, zero-emission design, reduce energy use, compact solar architecture, bioclimatic architecture, design for disassembly, solar architecture, flexibility in plans, energy generating buildings |

| Liveability and mixed use | Affordable housing, healthy community, social inclusion, mixed use, liveable and flexible housing typologies, secure tenure, diversity, integrating a diversity of economic and cultural activities, |

| Local food and short supply chains | Local food production, regional supply, urban farming and agriculture, community and allotment gardens, roof gardens, urban market garden, paper bags, recycling, organic produce |

| Identity and sense of place | Public health, cultural identity, urban heritage, air quality, distinct environment, grassroots strategies, affordable studio space, creativity of government and citizens, health, activities and safety |

| Urban governance and leadership | Evolutionary and adaptive policies, decision making, and responsibility shared with empowered citizenry, enabling citizens, updating building codes, improve planning participation, integrated public awareness, legislating controls on density and urban sprawl, support high quality densification, finance low-to-no-carbon pathways, eliminate fossil fuel subsidies, certify urban development projects |

| Education, research and knowledge | Up-skilling, knowledge dissemination, primary and secondary school teaching programs, university as a think tank, redefine education of architects, foundation of centre for sustainable urban development |

| Principle | Design |

|---|---|

| Health and happiness | Encouraging active, social, meaningful lives to promote health and wellbeing |

| Equity and local economy | Create safe equitable places to live and work, which support local prosperity and international fair trade |

| Culture and community | Nurturing local identity and heritage empowering communities and promoting a culture of sustainable living |

| Land and nature | Protecting and restoring land for the benefit of people and wildlife |

| Sustainable water | Using water efficiently, protecting local water resources and reducing flooding and drought |

| Local and sustainable food | Promoting sustainable humane farming and healthy diets high in local seasonal organic food and vegetable protein |

| Travel and transport | Reducing the need to travel, encouraging walking, cycling and low-carbon transport |

| Materials and products | Using materials from sustainable sources and promoting products, which help people reduce consumption |

| Zero waste | Reducing consumption re-using and recycling to achieve zero-waste and zero pollution |

| Zero carbon energy | Making buildings and manufacturing energy efficient and supplying all energy with renewables |

| Phase | City | Object | Principle |

|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental standard | |||

| Standardised models | Sustainable city Self-reliant city Resilient city Regenerative city | Renewable energy Low embodied energy Passive design Zero waste Food Water | Flows/close cycles |

| Carrying capacity, metabolism zero-low-carbon city | |||

| Technology and design | Bioregional city Green/Ubiquitous Eco-city | Climate Landscape and biodiversity | Landscape-based design |

| Smart city Redesign of city Knowledge city | Densification Transport and travel | ||

| Fair share/Equity and local economy/Community development | Social ecology Health & happiness Cultural community | Liveability | People, co-creation |

| Local production Identity | Innovative design | ||

| Uber governance | People, co-design | ||

| Education | People |

| Phase | Concept | Principle | Overarching | Principle | Object | City | Phase | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negotiatism | Co-design Co-creation | People Innovative design | Society | People, co-creation | Liveability Local production Identity | Social ecology Health & happiness Cultural community | Fair Share/Equity and local economy/Community development | |

| Innovative design | Urban governance | |||||||

| People, co-design people | Education | |||||||

| Emergenism | Interventions | Innovative design | ||||||

| Ecosystem based | Metabolism | Close cycles | Complexity | Flows/close cycles | Renewable energy Low embodied energy Passive design Zero waste Food Water | Sustainable city Self-reliant city Resilient city Regenerative city | Standardised models | |

| Antifragility | Antifragile | |||||||

| Emergenism | Interventions | Space for the unknown | ||||||

| Conceptualism | Layers, Casco S2N | Landscape as basis | Landscape | Landscape-based design | Climate Landscape and biodiversity | Carrying capacity, metabolism Zero-low-carbon City | ||

| Densification Transport & Travel | Bioregional city Green/Ubiquitous Eco-city Smart city Redesign of cities Knowledge city | Technology and design | ||||||

| Aesthetics | Environmental standard | |||||||

| Rationalism |

© 2017 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Roggema, R. The Future of Sustainable Urbanism: Society-Based, Complexity-Led, and Landscape-Driven. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1442. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9081442

Roggema R. The Future of Sustainable Urbanism: Society-Based, Complexity-Led, and Landscape-Driven. Sustainability. 2017; 9(8):1442. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9081442

Chicago/Turabian StyleRoggema, Rob. 2017. "The Future of Sustainable Urbanism: Society-Based, Complexity-Led, and Landscape-Driven" Sustainability 9, no. 8: 1442. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9081442

APA StyleRoggema, R. (2017). The Future of Sustainable Urbanism: Society-Based, Complexity-Led, and Landscape-Driven. Sustainability, 9(8), 1442. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9081442