Community Leadership in Rural Tourism Development: A Tale of Two Ancient Chinese Villages

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and a Theoretical Framework for Community Leadership in Rural Tourism Development

2.1. Leadership Theories: A Brief Review

2.1.1. Leaders

2.1.2. Interaction between Leaders and Followers

2.1.3. Situations

2.2. Community Leadership in Rural Tourism Development: A Theoretical Framework

2.2.1. Community Leadership and Rural Tourism Development

2.2.2. Community Leaders in Rural Tourism Development: A Particular Chinese Context

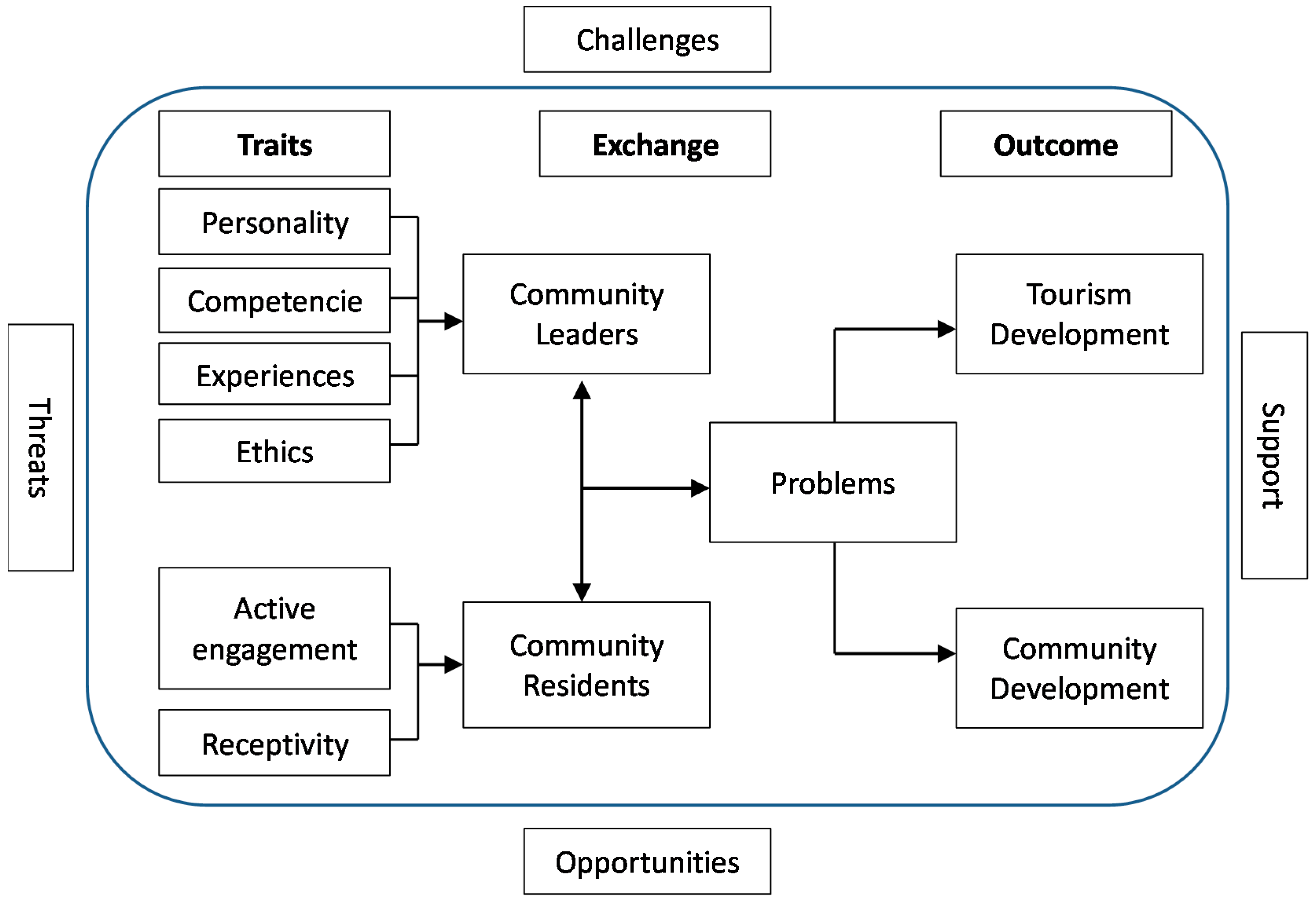

2.3. A Theoretical Framework for Community Leadership in Rural Tourism Development

3. Research Methods and Materials

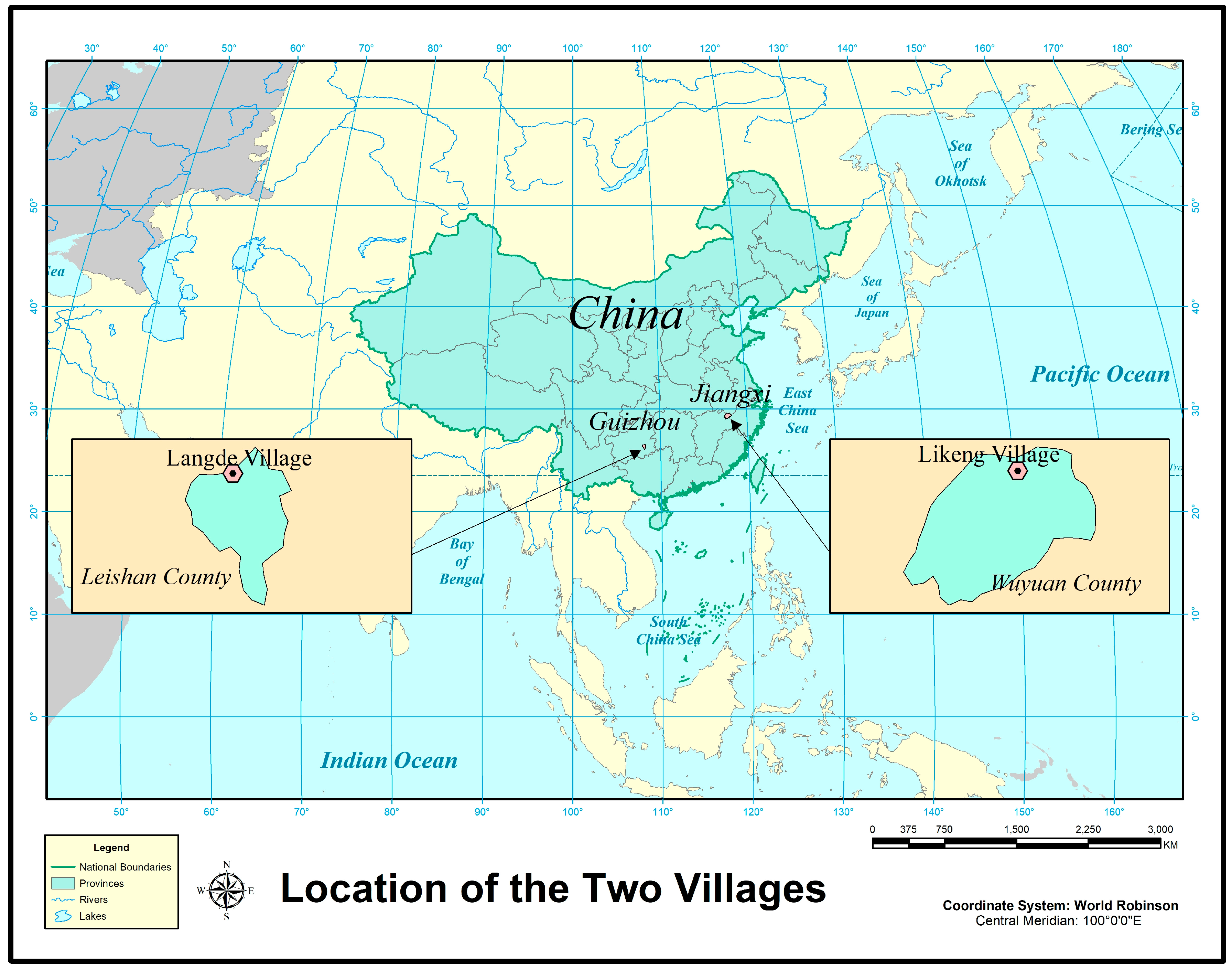

3.1. Langd Village and Likeng Village

3.2. Methods

4. Results

4.1. Community Leadership and Tourism Development in Langde Village

4.1.1. Phase 1 (1985 to 1988): Introducing Tourism into the Community

4.1.2. Phase 2 (2008 to 2016): From Prosperity to Decline

4.1.3. Phase 3 (2016 to Present): Controlled by Outsiders

4.2. Community Leadership and Tourism Development in Langde Village

4.2.1. Phase 1 (1997 to 2002): Start-Up

4.2.2. Phase 2 (2002 to 2016): Controlled by Outside Capital

4.2.3. Phase 3 (2017): Hybrid Development

5. Discussion

5.1. Rebel Leadership: A Key Factor for a Successful Start-Up

5.2. Banal Management and Poor Development

5.3. New Realities: Nurturing Resilient Leadership in the Future

6. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Locke, E.A. The Essence of Leadership: The Four Keys to Leading Successfully; Lexington Books: Lanham, MD, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Antonakis, J.; Day, D.V. The Nature of Leadership; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- April, K.A.; Macdonald, R.; Vriesendorp, S. Rethinking Leadership; Juta and Company Ltd.: Cape Town, South Africa, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bass, B.M.; Stogdill, R.M. Bass & Stogdill’s Handbook of Leadership: Theory, Research, and Managerial Applications; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Beerel, A. Leadership and Change Management; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bryman, A. Charisma and Leadership in Organizations; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Bryman, A. The SAGE Handbook of Leadership; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, B.; Ford, J.; Taylor, S. Leadership: Contemporary Critical Perspectives; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Day, D.V. The Oxford Handbook of Leadership and Organizations; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- DuBrin, A.J. Leadership: Research Findings, Practice, and Skills; Nelson Education: Scarborough, ON, Canada, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, J. On Leadership; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Hickman, G.R. Leading Organizations: Perspectives for a New Era; Sage Pulications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Mumford, M.D. Pathways to Outstanding Leadership: A Comparative Analysis of Charismatic, Ideological, and Pragmatic Leaders; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, Z.A.; Nawaz, A.; Irfanullah, K. Leadership theories and styles: A literature review. J. Resour. Dev. Manag. 2016, 16, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Northouse, P.G. Leadership: Theory and Practice; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Rost, J.C. Leadership for the Twenty-First Century; Greenwood Publishing Group: Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Stogdill, R.M. Handbook of Leadership: A Survey of Theory and Research; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Day, D.V. Leadership development: A review in context. Leadersh. Q. 2001, 11, 581–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snowden, D.J.; Boone, M.E. A leader’s framework for decision making. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2007, 85, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Puccio, G.J.; Mance, M.; Murdock, M.C. Creative Leadership: Skills that Drive Change; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Galli, E.B.; Müller-Stewens, G. How to build social capital with leadership development: Lessons from an explorative case study of a multibusiness firm. Leadersh. Q. 2012, 23, 176–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorensen, T.; Epps, R. Leadership and local development: Dimensions of leadership in four central Queensland towns. J. Rural Stud. 1996, 12, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, M. Engaging the global countryside: Globalization, hybridity and the reconstitution of rural place. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2007, 31, 485–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, J. Impulses towards a multifunctional transition in rural Australia: Gaps in the research agenda. J. Rural Stud. 2006, 22, 142–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, J. Impulses towards a multifunctional transition in rural Australia: Interpreting regional dynamics in landscapes, lifestyles and livelihoods. Landsc. Res. 2008, 33, 211–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, J. Cape York Peninsula, Australia: A frontier region undergoing a multifunctional transition with indigenous engagement. J. Rural Stud. 2012, 28, 252–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilbery, B. The Geography of Rural Change; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Dashper, K. Rural tourism: Opportunities and challenges. In Rural Tourism: An International Perspective; Dashper, K., Ed.; Cambridge Scholars Publishing: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2015; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Verbole, A. Actors, discourses and interfaces of rural tourism development at the local community level in Slovenia: Social and political dimensions of the rural tourism development process. J. Sustain. Tour. 2000, 8, 479–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, S.; Fesenmaier, D.R.; Fesenmaier, J.; Van Es, J.C. Factors for success in rural tourism development. J. Travel Res. 2001, 40, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bureau, N.T. Typical Cases of Rural Tourism Development; China Travel Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, S.; Huang, S.; Huang, Y. Rural tourism development in China. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2009, 11, 439–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, B. Rural tourism in China. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 1438–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haven-Tang, C.; Jones, E. Local leadership for rural tourism development: A case study of Adventa, Monmouthshire, UK. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2012, 4, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Ryan, C.; Cave, J. Chinese rural tourism development: Transition in the case of Qiyunshan, Anhui—2008–2015. Tour. Manag. 2016, 55, 240–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X. A phenomenological explication of guanxi in rural tourism management: A case study of a village in China. Tour. Manag. 2017, 63, 383–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, S.-F.; Lo, M.-C.; Songan, P.; Nair, V. Self-efficacy and sustainable rural tourism development: Local communities’ perspectives from Kuching, Sarawak. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2017, 22, 147–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Wu, B. Revitalizing traditional villages through rural tourism: A case study of Yuanjia Village, Shaanxi Province, China. Tour. Manag. 2017, 63, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, D.; Stewart, W.P. Social capital and collective action in rural tourism. J. Travel Res. 2017, 56, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, C.; Page, S. Tourism Management; Routledge: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, R.; Roberts, S. Tourism, Planning, and Community Development; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bao, J.; Sun, J. Differences in community participation in tourism development between China and the West. Chin. Sociol. Anthropol. 2007, 39, 9–27. [Google Scholar]

- Blackstock, K. A critical look at community based tourism. Community Dev. J. 2005, 40, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Li, L.; Li, T. The Organizational Evolution, Systematic Construction and Empowerment Significance of Langde Miao’s Community Tourism. Tour. Trib. 2013, 28, 75–86. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Huang, S.S.; Chen, G. Tourism Research in China: Themes and Issues; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W. Community decisionmaking participation in development. Ann. Tour. Res. 2006, 33, 132–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, B.K.; Cheung, L.T.; Hui, D.L. Community participation in the decision-making process for sustainable tourism development in rural areas of Hong Kong, China. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manyara, G.; Jones, E. Community-based tourism enterprises development in Kenya: An exploration of their potential as avenues of poverty reduction. J. Sustain. Tour. 2007, 15, 628–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matarrita-Cascante, D.; Brennan, M.A.; Luloff, A. Community agency and sustainable tourism development: The case of La Fortuna, Costa Rica. J. Sustain. Tour. 2010, 18, 735–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, R.E.; Reid, D.G. Community integration: Island tourism in Peru. Ann. Tour. Res. 2001, 28, 113–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, P.E. Tourism: A Community Approach (RLE Tourism); Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ndivo, R.M.; Cantoni, L. Rethinking local community involvement in tourism development. Ann. Tour. Res. 2016, 57, 275–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyaupane, G.P.; Morais, D.B.; Dowler, L. The role of community involvement and number/type of visitors on tourism impacts: A controlled comparison of Annapurna, Nepal and Northwest Yunnan, China. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 1373–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, D.G. Alternative tourism: Concepts, classifications, and questions. In Tourism Alternatives: Potentials and Problems in the Development of Tourism; Smith, V.L., Eadington, W.R., Eds.; University of Pennsylvania Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1992; pp. 15–30. [Google Scholar]

- Rasoolimanesh, S.M.; Jaafar, M.; Ahmad, A.G.; Barghi, R. Community participation in World Heritage Site conservation and tourism development. Tour. Manag. 2017, 58, 142–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, K. Strategic planning and community involvement as contributors to sustainable tourism development. Curr. Issues Tour. 2001, 4, 3–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, M.C. An integrated approach to assess the impacts of tourism on community development and sustainable livelihoods. Community Dev. J. 2009, 44, 186–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Bao, J. The community participation model of tourism: An empirical study of Yunnan and Guangxi. China Tour. Res. 2006, 2, 130–145. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, J.X.; Bao, J.G. Tourism anthropology analysis on community participation: A case study of Yulong River in Yangshuo. J. Guangxi Univ. Nationalities (Philos. Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2005, 27, 85–92. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Tosun, C. Limits to community participation in the tourism development process in developing countries. Tour. Manag. 2000, 21, 613–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosun, C. Stages in the emergence of a participatory tourism development approach in the Developing World. Geoforum 2005, 36, 333–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laverack, G.; Labonte, R. A planning framework for community empowerment goals within health promotion. Health Policy Plan. 2000, 15, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blackman, A. Perspectives on leadership coaching for regional tourism managers and entrepreneurs. In Building Community Capacity for Tourism Development; Moscardo, G., Ed.; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2008; pp. 142–154. [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza-Ramos, A.; Prideaux, B. Assessing ecotourism in an Indigenous community: Using, testing and proving the wheel of empowerment framework as a measurement tool. J. Sustain. Tour. 2017, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aref, F.; Redzuan, M.; Emby, Z. Assessing community leadership factor in community capacity building in tourism development: A case study of Shiraz, Iran. J. Hum. Ecol. 2009, 28, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, A. Local leadership and rural renewal through festival fun: The case of SnowFest. In Festival Places: Revitalising Rural Australia; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2011; pp. 61–73. [Google Scholar]

- Aref, F.; Redzuan, M. Community Leaders’ Characteristic and their Effort in Building Capacity for Tourism Development in Local Communities. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2009, 4, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aref, F.; Ma’rof, B. Barriers to Community Leadership towards Tourism Development in Shiraz, Iran. Eur. J. Soc. Sci. 2008, 7, 172–178. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, C.; Huang, S. The role of tourism in China’s transition: An introduction. In Tourism in China: Destinations, Planing and Experiences; Ryan, C., Huang, S., Eds.; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2013; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, J.; Cai, J.; Han, Y.; Liu, J. Identifying the conditions for rural sustainability through place-based Culture: Applying the CIPM and CDPM models into Meibei ancient village. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, L.; Kerstetter, D.; Hunt, C. Tourism development and changing rural identity in China. Ann. Tour. Res. 2017, 66, 170–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Chan, E.; Song, H. Social capital and entrepreneurial mobility in early-stage tourism development: A case from rural China. Tour. Manag. 2017, 63, 338–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Cheng, I.; Cheung, L. The roles of formal and informal institutions in small tourism business development in rural areas of south China. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Yan, T.; Zhu, X. Commodification of Chinese heritage villages. Ann. Tour. Res. 2013, 40, 415–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, T.; Zhou, Y. Community, governments and external capitals in China’s rural cultural tourism: A comparative study of two adjacent villages. Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 96–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormack, J.; Blair, J.G. Thinking through China; Rowman & Littlefield: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Weng, S.X.; Peng, H. The impact of power relationship on community participation in tourism development: A case from Furong Village at Nanxi River Basin, Zhejiang Province. Tour. Trib. 2010, 25, 51–57. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Y.F. Attractions in Wuyuan County Shut Down Due to Conflict of Interests. Available online: http://zqb.cyol.com/html/2011-08/17/nw.D110000zgqnb_20110817_4-02.htm (accessed on 9 September 2017).

- Yu, J.R. Contentious Politics: Fundamental Isuues in Chinese Political Sociology; People’s Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2010. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Dorfman, P.W.; Hanges, P.J.; Brodbeck, F.C. Leadership and cultural variation: The identification of culturally endorsed leadership profiles. In Culture, Leadership, and Organizations: The GLOBE Study of 62 Societies; Dorfman, P.W., Hanges, P.J., Brodbeck, F.C., Eds.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2004; pp. 669–719. [Google Scholar]

- Mok, K.-H.; Wang, L. Handbook of Contemporary China; World Scientific: Singapore, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Heifetz, R.A. Leadership without Easy Answers; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Heifetz, R.A.; Laurie, D.L. The work of leadership. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1997, 75, 124–134. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kotter, J.P. Force for Change: How Leadership Differs from Management; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg, L.R. An alternative “description of personality”: The big-five factor structure. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1990, 59, 1216–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge, T.A.; Bono, J.E.; Ilies, R.; Gerhardt, M.W. Personality and leadership: A qualitative and quantitative review. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 765–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katz, R. Skills of an effective administrator. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1955, 33, 33–42. [Google Scholar]

- Mumford, M.D.; Zaccaro, S.J.; Harding, F.D.; Jacobs, T.O.; Fleishman, E.A. Leadership skills for a changing world: Solving complex social problems. Leadersh. Q. 2000, 11, 11–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blake, R.R.; Mouton, J.S. The Managerial Grid; Gulf Publishing Company: Houston, UK, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Zigarmi, P.; Zigarmi, D.; Blanchard, K. Leadership and the One Minute Manager; FontanaCollins: New York, NY, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- House, R.J.; Mitchell, T.R. Path-goal theory of leadership. J. Contemp. Bus. 1974, 3, 81–97. [Google Scholar]

- Bass, B. Leadership and Performance beyond Expectations; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, W.L.; Avolio, B.J.; Luthans, F.; May, D.R.; Walumbwa, F. “Can you see the real me?” A self-based model of authentic leader and follower development. Leadersh. Q. 2005, 16, 343–372. [Google Scholar]

- Liden, R.C.; Wayne, S.J.; Zhao, H.; Henderson, D. Servant leadership: Development of a multidimensional measure and multi-level assessment. Leadersh. Q. 2008, 19, 161–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blake, R.R.; McCanse, A.A. Leadership Dilemmas—Grid Solutions; Gulf Professional Publishing: Houston, TX, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- House, R.J. A path goal theory of leader effectiveness. Adm. Sci. Q. 1971, 16, 321–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graen, G.B.; Uhl-Bien, M. Relationship-based approach to leadership: Development of leader-member exchange (LMX) theory of leadership over 25 years: Applying a multi-level multi-domain perspective. Leadersh. Q. 1995, 6, 219–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions and Organizations across Nations; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bryman, A.; Stephens, M.; a Campo, C. The importance of context: Qualitative research and the study of leadership. Leadersh. Q. 1996, 7, 353–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, L.; O’Loughlin, P.; Salt, A. Community Leadership Programs in New South Wales, UTS Shopfront; The Strengthening Communities Unit, NSW Premier’s Department: Sydney, Australia, 2001.

- Goeppinger, A. The fallacies of our reality: A deconstructive look at community and leadership. Int. J. Leadersh. Educ. 2002, 5, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raik, D.B.; Decker, D.J.; Siemer, W.F. Dimensions of capacity in community-based suburban deer management: The managers’ perspective. Wildl. Soc. Bull. 2003, 31, 854–864. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, B.; Lichtenstein, E.; Corbett, K.; Nettekoven, L.; Feng, Z. Durability of tobacco control efforts in the 22 Community Intervention Trial for Smoking Cessation (COMMIT) communities 2 years after the end of intervention. Health Educ. Res. 2000, 15, 353–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luloff, A.E.; Bridger, J.C.; Graefe, A.R.; Saylor, M.; Martin, K.; Gitelson, R. Assessing rural tourism efforts in the United States. Ann. Tour. Res. 1994, 21, 46–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscardo, G. Tourism and community leadership in rural regions: Linking mobility, entrepreneurship, tourism development and community well-being. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2014, 11, 354–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscardo, G. Building Community Capacity for Tourism Development; CABI: Wallingford, TX, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer, L.; Edwards, D. Sustainable tourism planning. In Understanding the Sustainable Development of Tourism; Liburd, J.J., Edwards, D., Eds.; Goodfellow Publishers Limited: Oxford, UK, 2010; pp. 19–44. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, G.; Palmer, R. Eventful Cities: Cultural Management and Urban Revitalisation; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Pitron, J. The Influence of Exemplary Followership on Organizational Performance: A Phenomenological Approach. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Phoenix, Phoenix, AZ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, B.; Jiang, Y.; Yang, L.; Ma, Y. Stage characteristics and policy choices of China’s outbound tourism development. Tour. Trib. 2013, 28, 39–45. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- House, R.J.; Hanges, P.J.; Javidan, M.; Dorfman, P.W.; Gupta, V. Culture, Leadership, and Organizations: The GLOBE Study of 62 Societies; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, H.; Ryan, C. Hongcun, China—Residents’ Perceptions of the Impacts of Tourism on a Rural Community: A Mixed Methods Approach. J. China Tour. Res. 2010, 6, 216–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, T.J. The Practice of Building New Countryside in China; Wenjin Press: Beijing, China, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Long, H.; Liu, Y.; Li, X.; Chen, Y. Building new countryside in China: A geographical perspective. Land Use Policy 2010, 27, 457–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, J. Linking ICTs to rural development: China’s rural information policy. Gov. Inf. Q. 2010, 27, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pi, C.; Zheng, X. Customers’ Complaints about Bed and Breadfast Based on Online Reviews Analysis: A Case Study of Xiamen. Tour. Forum 2017, 3, 35–44. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, M.F. Likeng: Living Environment in an Ancient Village; China Meteorological Press: Beijing, China, 2008. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Pearce, D.G. Comparative studies in tourism research. In Tourism Research: Critiques and Challenges; Pearce, D.G., Butler, R.W., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 1993; pp. 20–35. [Google Scholar]

- Getz, D. Residents’ attitudes towards tourism: A longitudinal study in Spey Valley, Scotland. Tour. Manag. 1994, 15, 247–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, J.M.; Noguchi, L.M.; Harder, M.K. Understanding the Process of Community Capacity-Building: A Case Study of Two Programs in Yunnan Province, China. World Dev. 2017, 97, 122–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.Y. On the labor-scoring system for participation in minority tourism communities: A case study of Langde upper village. J. Guizhou Univ. Natly. 2010, 30, 189–193. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yu, K. Globalization and Changes in China’s Governance; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Wall, G. Planning for Ethnic Tourism; Farnham: Ashgate, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bennis, W.; Nanus, B. Leaders: The Strategies for Taking Charge; Harper and Row: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Ding, P.; Bao, J. Patron–client ties in tourism: The case study of Xidi, China. Tour. Geogr. 2009, 11, 390–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colliers, P. Complexity and Postmodernism; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Mumford, M.D.; Marks, M.A.; Connelly, M.S.; Zaccaro, S.J.; Reiter-Palmon, R. Development of leadership skills: Experience and timing. Leadersh. Q. 2000, 11, 87–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heifetz, R.; Grashow, A.; Linsky, M. The Practice of Adaptive Leadership; Harvard Business Press: Boston, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

| Location | Year | Stakeholders | Interview Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Langde | 2007 | The former village head, 2 township officers, the director of the county tourism bureau, an officer from the provincial government, 10 residents participating in tourism, 4 tourists, 3 volunteers (college students) | Face-to-face interview |

| 2008 | The former village secretary, 4 college students from the village, 4 inn operators | Face-to-face interview | |

| 2012 | 1 township officer, 2 village officers, 1 inn operator, 2 residents (1 female, 1 male) | Face-to-face interview | |

| 2017 | 6 young residents (3 males and 3 females) | Online interview | |

| Likeng | 2007 | The former village head, one local township officer, one officer in the county tourism bureau, one manager of the tourism company, the seller of the company, 5 residents participating in tourism (1 tour guide, 2 persons operating rural inns, 2 persons selling goods to tourists), 7 residents not participating in tourism (3 females and 4 males) | Face-to-face interview |

| 2017 | 7 residents participating in tourism (the seller of the tourism company, 1 tour guide who was re-interviewed, 2 couples operating rural inns, 1 young female and one old male selling goods to tourists) the village secretory, 2 residents not participating in tourism (1 female and 1 male) | Face-to-face interview |

| Roles | Points | Types of National Costume | Points |

|---|---|---|---|

| Table leader | 1 | Gown | 10 |

| Greeter | 1 | Ordinary clothes | 9 |

| Lusheng player | 9 | Holiday costumes | 11 |

| Attendant | 6 | Holiday costumes with silver shawl | 15 |

| Singer and dancer | 4 | Holiday costumes with silver shawl and headdress | 20 |

| Students of different ages | 1–5 | ||

| Manager | 18 |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xu, K.; Zhang, J.; Tian, F. Community Leadership in Rural Tourism Development: A Tale of Two Ancient Chinese Villages. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2344. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9122344

Xu K, Zhang J, Tian F. Community Leadership in Rural Tourism Development: A Tale of Two Ancient Chinese Villages. Sustainability. 2017; 9(12):2344. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9122344

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Keshuai, Jin Zhang, and Fengjun Tian. 2017. "Community Leadership in Rural Tourism Development: A Tale of Two Ancient Chinese Villages" Sustainability 9, no. 12: 2344. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9122344

APA StyleXu, K., Zhang, J., & Tian, F. (2017). Community Leadership in Rural Tourism Development: A Tale of Two Ancient Chinese Villages. Sustainability, 9(12), 2344. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9122344