Distributed Leadership in a Low-Carbon City Agenda

Abstract

:1. Introduction

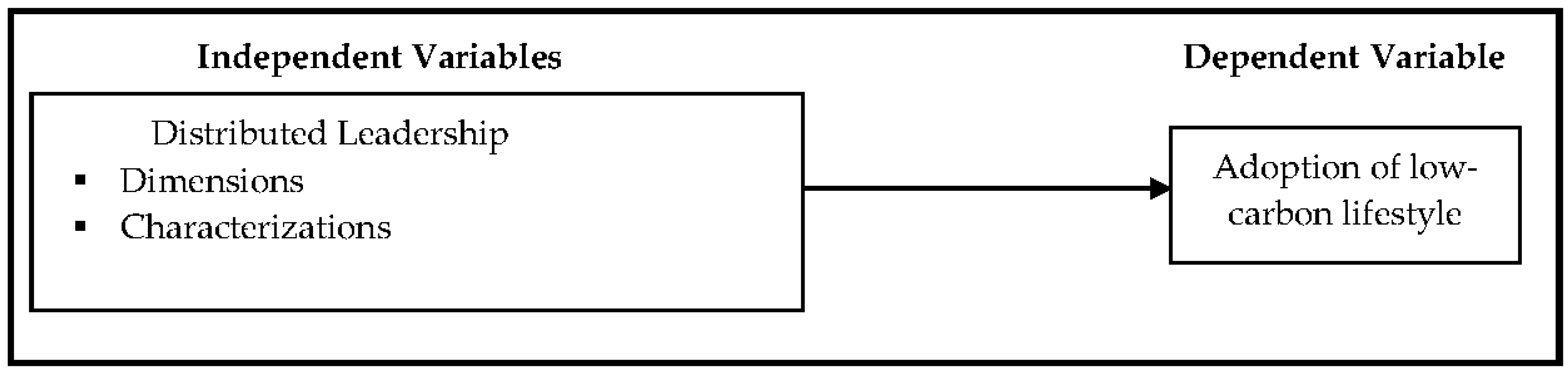

- multiple levels of involvement in decision-making

- it focuses on improving practice or instruction

- it encompasses both formal and informal leaders

- it links vertical and lateral leadership structures

- it is flexible and versatile

- it is fluid and interchangeable.

- The development of a culture within the organization that embodies collaboration, trust, professional learning and reciprocal accountability.

- Strong consensus regarding the important problems facing the organization.

- A need for rich expertise with approaches to improving knowledge and skills among members of the organization.

2. Distributed Leadership in Practice: Putrajaya Low-Carbon City Initiatives

- Low-Carbon Putrajaya: To reduce GHG emission intensity related to energy use by 60%;

- 3R Putrajaya: To reduce the final disposal of solid waste and GHG emission per waste generation by 50%; and

- Cooler Putrajaya: To reduce peak temperature by 2 °C.

3. Method

3.1. Focus Group Discussion

3.2. Structured Interviews

3.3. Survey

3.3.1. Sample

3.3.2. Sample Size

3.3.3. Sampling

3.3.4. Research Instrument

- Vision: Survey items in this dimension refer to the collective beliefs of the community leaders concerning the low-carbon city agenda. Community leaders provide input in setting the low-carbon city’s vision, and goals. Community leaders can articulate the city’s vision. The RAC’s goals are aligned with the city’s goals.

- Organizational Framework: Organizational framework refers to the structure of the low-carbon city framework which includes the agencies, RACs and individuals associated with it and the structural connections between them. The attributes in this dimension relate to opportunities for RACs and community leaders to assume leadership roles and participate in decision making as well as make meaningful contributions to the low-carbon city initiatives.

- Organizational culture: Organizational cultures are the intangible principles that define the low-carbon community climate. Attributes in this dimension relate to community leaders being encouraged by the low-carbon city administration to take up leadership roles in the community’s low-carbon initiatives, community members collaborate to solve problems and discuss instructional strategies with one another and the agencies governing the low-carbon city agenda. The attributes also relate to community leaders feel respected by their peers and the administrator.

- Consensus: Consensus means that the administrator and community leaders are in agreement in the programs. The attributes in this dimension relate to community leaders role in the decision making process.

- Instructional program: Instructional program refers to guidelines and instructions pertaining to the implementation of low-carbon initiatives. The attributes in this dimension relate to community leaders’ involvement in setting the guidelines for their community and authority of community leaders to make instructional changes based on the specific needs and suitability in their respective community.

- Expertise: Expertise refers to the skilled and knowledgeable individuals in the RACs to lead the community’s low-carbon initiatives. The attributes in this dimension relate to how expertise is managed and coordinated in order to leverage its potential.

- Team leader leadership: Team leader refers to the program administrator specifically the local authority and other related agencies in the low-carbon city implementation framework. The attributes in this dimension demonstrate the level of leadership by the team leader, the team leader’s participation in RAC meetings and RAC activities, the team leader’s knowledge about the program, and the team leader’s leadership in improving the program outcomes.

- Team member leadership: Team member refers to members of residents’ association committees. Team member leadership refers to leadership demonstrated by team members. The survey items in this dimension relates to team members’ interest to serve in low-carbon city leadership roles, opportunities for team members or other members of the community to influence improvement in the program outcomes.

- Authorized distributed leadership: Authorized distributed leadership takes place when formal leaders distribute work and work is accepted as a means of empowerment [86]. This type of leadership is evident in a hierarchical structure such as in teams and committees. The attributes in this leadership practice relate to team members receiving instructions from team leader to make decisions and have control on specified areas. Team leader allows members to initiate collaborations with one another and also with other RACs but team leader maintains the ultimate power to lead.

- Dispersed distributed leadership: This characterization refers to leadership activity that happens without the formal working of hierarchy, where leadership is more bottom-up, team members and skilled individuals work as empowered and self-led teams. The attributes in this leadership practice relate to relative freedom to interact and lead, where knowledgeable and skilled individuals either individually or collaboratively lead the practice.

3.3.5. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Exploratory Data Analysis

4.2. Descriptive Statistics

4.3. Correlation Analyses

4.4. Multiple Regression Analyses

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- IPCC. Summary for policymakers. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. In Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Stocker, T.F., Qin, D., Plattner, G.K., Tignor, M., Allen, S.K., Boschung, J., Nauels, A., Xia, Y., Bex, V., Midgley, P.M., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Pittock, A.B. Climate Change: Turning up the Heat; CSIRO Publishing: Collingwood, Australia, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Diffenbaugh, N.S.; Field, C.B. Changes in ecologically critical terrestrial climate conditions. Science 2013, 341, 486–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pittock, A.B. Climate Change: The Science, Impacts and Solutions; CSIRO Publishing: Collingwood, Australia, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, J.; Oreskes, N.; Doran, P.T.; Anderegg, W.R.L.; Verheggen, B.; Maibach, E.W.; Carlton, J.S.; Lewandowsky, S.; Skuce, A.G.; Green, S.A.; et al. Consensus on consensus: A synthesis of consensus estimates on human-caused global warming. Environ. Res. Lett. 2016, 11, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, S.C.; Karoly, D.J. Anthropogenic contributions to Australia’s record summer temperatures of 2013. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2013, 40, 3705–3709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schipper, L.; Bartlett, S.; Hawk, D.; Vine, E. Linking lifestyle and energy use: A matter of time? Ann. Rev. Energy 1989, 14, 273–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutzenhiser, L. A cultural model of household energy consumption. Energy 1992, 17, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutzenhiser, L.; Hackett, B. Social stratification and environmental degradation: Understanding household CO2 production. Soc. Probl. 1993, 40, 50–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capstick, S.; Lorenzoni, I.; Corner, A.; Whitmarsh, L. Prospects for radical emissions reduction through behavior and lifestyle change. Carbon Manag. 2014, 5, 429–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allan, C.; Kerr, S.; Will, C. Are We Turning Brighter Shade of Green? The Relationship between Household Characteristics and Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Consumption in New Zealand; Motu Economic and Public Policy Research: Wellington, New Zealand, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, P.; Dutta, M. Trends in per capita household expenditure and its implications on carbon emissions in developed versus developing countries. Int. J. Manag. Soc. Sci. 2015, 4, 81–92. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Oosterveer, P.; Spaargaren, G. Promoting sustainable consumption in China: A conceptual framework and research review. J. Clean. Prod. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, K.E.; Schor, J.B.; Abrahamse, W.; Alkon, A.H.; Axsen, J.; Brown, K.; Shwom, R.L.; Southerton, D.; Wilhite, H. Consumption and climate change. In Climate Change and Society: Social Perspectives; Dunlap, R.E., Brulle, R.J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 93–126. [Google Scholar]

- Goodall, C. How to Live a Low-Carbon Life? Earthscan: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Howell, R. It’s not (just) “the environment, stupid!” Values, motivations, and routes to engagement of people adopting lower-carbon lifestyles. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2013, 23, 281–290. [Google Scholar]

- Dietz, T.; Gardner, G.T.; Giligan, J.; Stern, P.C.; Vandenbergh, M.P. Household actions can provide a behavioral wedge to rapidly reduce US carbon emissions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 18452–18456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barr, S.; Gilg, A.W. Sustainable lifestyles: Framing environmental action in and around the home. Geoforum 2006, 37, 906–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, S.; Gilg, A.W. A conceptual framework for understanding and analyzing attitudes: Towards environmental behavior. Swed. Soc. Anthropol. Geogr. 2007, 89B, 361–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, S.; Gilg, A.W.; Ford, N.J. A conceptual framework for understanding and analyzing attitudes towards household waste-management. Environ. Plan. A 2001, 33, 2025–2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, S.; Shaw, G.; Coles, T. Times for (Un)sustainability? Challenges and opportunities for developing behaviour change policy. A case-study of consumers at home and away. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2011, 21, 1234–1244. [Google Scholar]

- Barr, S.; Gilg, A.W.; Shaw, G. Helping People Make Better Choices: Exploring the behaviour change agenda for environmental sustainability. Appl. Geogr. 2011, 31, 712–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA). A Framework for Pro-Environmental Behaviours; DEFRA: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Whitmarsh, L.; O’Neill, S. Green identity, green living? The role of pro-environmental self-identity in determining consistency across diverse pro-environmental behaviours. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 305–314. [Google Scholar]

- Heiskanen, E.; Johnson, M.; Robinson, S.; Vadovics, E.; Saastamoinen, M. Low-carbon communities as a context for individual behavioural change. Energy Policy 2010, 38, 7586–7595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moloney, S.; Horne, R.E.; Fien, J. Transitioning to low carbon communities-from behaviour change to systemic change: Lessons from Australia. Energy Policy 2010, 38, 7614–7623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, G. The Role for ‘Community’ in Carbon Governance. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Chang. 2011, 2, 777–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, S.J.; Coffey, S. Building a sustainable energy future, one community at a time. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 60, 867–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shove, E. Converging conventions of comfort, cleanliness and convenience. J. Consum. Policy 2003, 26, 395–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guy, S. Designing urban knowledge: Competing perspectives on energy and buildings. Environ. Plan. C Gov. Policy 2006, 24, 645–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollock, P. Social dilemmas: The anatomy of cooperation. Am. Rev. Sociol. 1998, 24, 183–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutzenhiser, L. Social and behavioral aspects of energy use. Ann. Rev. Energy Environ. 1993, 18, 247–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, T. Motivating Sustainable Consumption: A Review of Models of Consumer Behaviours and Behavior Change; The Sustainable Development Research Network: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Thogersen, J. How may consumer policy empower consumers for sustainable lifestyles? J. Consum. Policy 2005, 28, 143–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyre, N.; Flanagan, B.; Double, K. Engaging people in saving energy on a large scale: Lessons from the programmes of the Energy Saving Trust in the UK. In Engaging the Public with Climate Change: Behaviour Change and Communication; Whitmarsh, L., O’Neill, S., Lorenzoni, I., Eds.; Earthscan: London, UK, 2011; pp. 139–159. [Google Scholar]

- Whitmarsh, L.; O’Neill, S.; Seyfang, G.; Lorenzoni, I. Carbon Capability: What Does It Mean, How Prevalent Is It, and How Can We Promote It? Tyndall Working Paper; Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research: Norwich, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Middlemiss, M.; Parrish, B.D. Building capacity for low-carbon communities: The role of grassroots initiatives. Energy Policy 2010, 38, 7559–7566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starik, M.; Rands, G. Weaving an integrated web: Multilevel ecologically sustainable organizations. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 908–935. [Google Scholar]

- Tudor, T.; Barr, S.; Gilg, A. A tale of two locational settings: Is there a link between pro-environmental behaviour at work and at home? Local Environ. Int. J. Justice Sustain. 2007, 12, 409–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.; Fudge, S.; Sinclair, P. Mobilising community action towards a low-carbon future: Opportunities and challenges for local government in the UK. Energy Policy 2010, 38, 7596–7603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schelly, C.; Cross, J.E.; Franzen, W.S.; Hall, P.; Reeve, S. Reducing energy consumption and creating a conservation culture in organizations: A case study of one public school district. Environ. Behav. 2011, 43, 316–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skea, J.; Nishioka, S. Policies and practices for a low-carbon society. Clim. Policy 2008, 8, S5–S16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burch, S. In pursuit of resilient, low carbon communities: An examination of barriers to action in three Canadian cities. Energy Policy 2010, 38, 7575–7585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulkeley, H.; Castán-Broto, V.; Maassen, A. Governing urban low carbon transitions. In Cities and Low Carbon Transitions; Bulkeley, H., Castán-Broto, V., Hodson, M., Marvin, S., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2010; pp. 29–41. [Google Scholar]

- Bulkeley, H.; Schroeder, H.; Janda, K.; Zhao, J.; Armstrong, A.; Chu, S.Y.; Ghosh, S. Cities and climate change: The role of institutions, governance and urban planning. In Proceedings of the 5th Urban Research Symposium: Cities and Climate Change—Responding to an Urgent Agenda, Marseille, France, 28–30 June 2009.

- Aiken, G.T. Prosaic state governance of community low carbon transitions. Political Geogr. 2016, 55, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markantoni, M. Low carbon governance: Mobilizing community energy through top-down support? Environ. Policy Gov. 2016, 26, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartley, J.; Allison, M. The modernization and improvement of government and public services: The role of leadership in the modernization and improvement of public services. Public Money Manag. 2000, 20, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Townsend, A. Leading school networks hybrid leadership in action. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2015, 43, 719–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spillane, J.; Diamond, J. Distributed Leadership in Practice; Teachers College Press: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, A.; Leithwood, K.; Day, C.; Sammons, P.; Hopkins, D. Distributed leadership and organizational change: Reviewing the evidence. J. Educ. Chang. 2007, 8, 337–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, A. Distributed School Leadership: Developing Tomorrow’s Leaders; Routledge: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Spillane, J.; Halverson, R.; Diamond, J. Investigating school leadership practice: A distributed perspective. Educ. Res. 2001, 30, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spillane, J. Distributed Leadership; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Spillane, J. Distributed leadership. Educ. Forum 2005, 69, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gronn, P. Distributed properties: A new architecture for leadership. Educ. Manag. Adm. 2000, 28, 317–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gronn, P. Distributed leadership as a unit of analysis. Leadersh. Q. 2002, 13, 423–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, A. Distributed leadership: Current evidence and future directions. J. Manag. Dev. 2011, 30, 20–32. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, N.; Wise, C.; Woods, P.A.; Harvey, J.A. Distributed Leadership: A Review of Literature; National College for School Leadership: Manchester, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hulpia, H.; Devos, G.; Keer, H.V. The relation between school leadership from a distributed perspective and teachers’ organizational commitment: Examining the source of the leadership function. Educ. Adm. Q. 2011, 47, 728–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spillane, J.P.; Halverson, R.; Diamond, J.B. Towards a theory of leadership practice: A distributed perspective. J. Curric. Stud. 2004, 36, 3–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, A. Distributed leadership: Friend or foe? Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2013, 41, 545–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graetz, F. Strategic change leadership. Manag. Decis. 2000, 38, 550–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, A.; Chapman, C. Leadership in schools facing challenging circumstances. Manag. Educ. 2002, 16, 10–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, P.A.; Bennett, N.; Harvey, J.A.; Wise, C. Variabilities and dualities in distributed leadership: Findings from a systematic literature review. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2004, 32, 439–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kets de Vries, M.F.R. High-performance teams: Lessons from the pygmies. Organ. Dyn. 1999, 12, 66–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copland, M.A. Leadership of enquiry: Building and sustaining capacity for school improvement. Educ. Eval. Policy Anal. 2003, 25, 375–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sammons, P.; Qing, G.; Day, C.; Ko, J. Exploring the impact of school leadership on pupil outcomes: Results from a study of academically improved and effective schools in England. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2011, 25, 83–101. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, A. System improvement through collective capacity building. J. Educ. Adm. 2011, 49, 624–636. [Google Scholar]

- Hargreaves, A. Sustainable leadership and development in education: Creating the future, conserving the past. Eur. J. Educ. 2007, 42, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leithwood, K.; Mascall, B. Collective leadership effects on student achievement. Educ. Adm. Q. 2008, 44, 529–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leithwood, K.; Seashore-Louis, K.; Anderson, S.; Walstrom, K. How Leadership Influences Student Learning: A Review of Research for the Learning for Leadership Project; Wallace Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Leithwood, K.; Mascall, B.; Strauss, T. (Eds.) Distributed Leadership According to the Evidence; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2009.

- Leithwood, K.; Mascall, B.; Strauss, T.; Sacks, R.; Memon, N.; Yashkina, A. Distributing leadership to make schools smarter: Taking ego out of the system. In Distributed Leadership According to the Evidence; Leithwood, K., Mascall, B., Strauss, T., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 223–252. [Google Scholar]

- Gunter, H.M. Leading Teachers; Continuum: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, A.; Mujis, D. Improving Schools through Teacher Leadership; Open University Press: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- MacBeath, J. Leadership as distributed: A matter of practice. School Leadersh. Manag. 2005, 25, 349–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, L.; Ferlie, E.; McGivern, G.; Buchanan, D. Distributed leadership patterns and service improvement: Evidence and argument from English healthcare. Leadersh. Q. 2013, 24, 227–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, A. Distributed leadership: According to the evidence. J. Educ. Adm. 2008, 46, 172–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, M.W. Distributed Leadership and School Performance. Ph.D. Thesis, George Washington University, Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Heck, R.H.; Hallinger, P. Assessing the contribution of distributed leadership to school improvement and growth in math achievement. Am. Educ. Res. J. 2009, 46, 659–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascall, B.; Leithwood, K.; Straus, T.; Sacks, R. The relationship between distributed leadership and teachers’ optimism. J. Educ. Adm. 2008, 46, 217–228. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, M.B.; Huberman, A.M. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Sourcebook of New Methods; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg, M.E.; Greenberg, M.T.; Osgood, D.W.; Anderson, A.; Babinski, L. The effects of training community leaders in prevention science: Communities that care in Pennsylvania. Eval. Program Plan. 2002, 25, 245–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krejcie, R.V.; Morgan, D.W. Determining sample size for research activities. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1970, 30, 607–610. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, L.; Manion, L.; Morrison, K. Research Methods in Education, 5th ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, S. The Impact of Distributed Leadership Practices on the Functioning of Primary Schools in Johannesburgh South, South Africa. Master’s Thesis, University of South Africa, Gauteng, South Africa, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S. Using Multivariate Statistics, 5th ed.; Allyn & Bacon: Needham Height, MA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Guilford, J.P. Fundamental Statistics in Psychology and Education; McGraw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1956. [Google Scholar]

- DEFRA. Securing the Future: The UK Government Sustainable Development Strategy; Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- DEFRA. Climate Change: The UK Programme 2006; Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- McColl-Kennedy, J.R.; Anderson, R.D. Impact of leadership style and emotions on subordinate performance. Leadersh. Q. 2002, 13, 545–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conger, J.A. Charismatic and transformational leadership in organizations: An insider’s perspective on these developing streams of research. Leadersh. Q. 1999, 10, 45–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avery, G.S. Understanding Leadership: Paradigms and Cases; Sage: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Rowe, W.G.; Canella, A.A., Jr.; Rankin, D.; Gorman, D. Leader succession and organizational performance: Integrating the common-sense, ritual scapegoating and vicious circle succession theories. Leadersh. Q. 2005, 16, 197–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berson, Y.; Shamair, B.; Avolio, B.J.; Popper, M. The relationship between vision strength, leadership style and context. Leadersh. Q. 2001, 12, 509–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salomon, G. No distribution without individual cognition: A distributed interactionist view. In Distributed Cognition: Psychological and Educational Considerations; Salomon, G., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Timperley, H. Distributed leadership: Developing theory from practice. J. Curric. Stud. 2005, 37, 395–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leithwood, K.; Harris, A.; Hopkins, D. Seven strong claims about successful school leadership. Sch. Leadersh. Manag. 2008, 28, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayrowetz, D. Making sense of distributed leadership: Exploring the multiple usages of the concept in the field. Educ. Adm. Q. 2008, 44, 424–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, K.D. Transformational teacher leadership in rural schools. Rural Educ. 2008, 29, 8–17. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, V.M.J. Forging the links between distributed leadership and educational outcomes. J. Educ. Adm. 2008, 46, 241–256. [Google Scholar]

- Mehra, A.; Smith, B.; Dixon, A.; Robertson, B. Distributed leadership in teams: The network of leadership perceptions and team performance. Leadersh. Q. 2006, 17, 232–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hairudin, M.A.; Yangaiya, S.A. Investigating the influence of distributed leadership on school effectiveness: A mediating role of teachers’ commitment. J. Educ. Soc. Res. 2015, 5, 163–174. [Google Scholar]

- Simkins, T. Leadership in education: ‘What works’ or ‘What makes sense’? Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2005, 33, 9–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petty, M.M.; Beadles, N.A.; Lowery, C.M.; Chapman, D.F.; Connell, D.W. Relationships between organizational culture and organizational performance. Psychol. Rep. 1995, 76, 483–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, J. Organizational Culture: Mapping the Terrain; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Zammuto, R.F. Does Who You Ask Matter? Hierarchical Subcultures and Organizational Culture Assessments; The Business School, University of Colorado: Denver, CO, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron, K.S.; Quinn, R.E. Diagnosing and Changing Organizational Culture: Based on the Competing Values Framework, 3rd ed.; Wiley & Son Inc.: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Linnenlueke, M.K.; Griffiths, A. Corporate sustainability and organizational culture. J. World Bus. 2010, 45, 357–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargreaves, D. Transforming Secondary Schools through Innovation Networks; Demos: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Himmelman, A.T. On the theory and practice of transformational collaboration: From social service to social justice. In Creating Collaborative Advantage; Huxham, C., Ed.; Sage Publications Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1996; pp. 19–43. [Google Scholar]

- Hargreaves, A. Changing Teachers, Changing Times Teachers’ Work and Culture in the Postmodern Age; Cassell: London, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, C.; Singh, H. Passing the buck: This is not teacher leadership. Perspect. Educ. 2009, 27, 289–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, C.; Sammons, P.; Leithwood, K.; Harris, A.; Hopkins, D. The Impact of Leadership on Pupil Outcomes: Final Report; Department of Children, Families & Schools (DCFS): London, UK; National College of School Leadership: Nottingham, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, S. Human nature and environmentally responsible behavior. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 491–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Environmental Targets | Action |

|---|---|

| Low-Carbon Putrajaya | 1. Integrated City Planning and Management |

| 2. Low-Carbon Transportation | |

| 3. Cutting Edge Sustainable Buildings | |

| 4. Low-Carbon Lifestyle | |

| 5. More and More Renewable Energy | |

| 6. The Green Lungs of Putrajaya | |

| Cooler Putrajaya | 7. Cooler Urban Structure and Buildings |

| 8. Community and Individual Actions to Reduce Urban Temperature | |

| 3R Putrajaya | 9. Use Less Consume Less |

| 10. Think Before You Throw | |

| 11. Integrated Waste Treatment | |

| Cross Category | 12. Green Incentives and Capacity |

| Category | Quotes from Respondents Surveyed |

|---|---|

| (a) Dimension | |

| Vision | “I’m not sure what the local authority hopes to achieve through their low-carbon city agenda, but as far as my RAC’s concern, our only focus is to ensure that our neighborhood is kept clean and litter free. We were not involved in the planning process but I suppose the master plan does include us (RACs).” |

| “They should have included us (in the planning). After all, we (RACs) are the ones who will be conducting the programs in the community.” | |

| “A few of us attended a workshop about this matter a few years ago. A few agencies were also present. We discussed about the programs, we gave our views and suggestions especially on how our community can take part in the program.” | |

| “My RAC Chairman has been involved in the low-carbon city program since it started. He updates us with the latest information.” | |

| Organizational framework | “There should be more RAC representatives in the Low-carbon City Council.” |

| “I’m not sure where my RAC fit in this low-carbon city framework.” | |

| “There are many agencies involved in the low-carbon city program, each has specific focuses and functions but they are all connected in the network.” | |

| Organizational culture | “The low-carbon city agenda should be carried by the whole community, not just the local authority, nor the agencies. Community leaders must be encouraged to take leadership roles in low-carbon initiatives. If community leaders are not empowered, the program will not succeed.” |

| “We are encouraged to collaborate with other RACs. One of our shared projects is the ‘Kitchen Garden’. We have regular meetings to discuss and properly plan for the project. We not only share resources and responsibilities but we also decide together on future projects.” | |

| “We have close relationships with a few RACs. We exchange views and help one another. I like asking for their opinion because we usually face the same problems in our community.” | |

| Consensus | “Sometimes they ask for our opinion, but most of the time we just receive instructions.” |

| “Only the Chairman knows what was discussed or decided in the meetings with the local authority.” | |

| “Most of the time they will call us to inform us of the coming programs.” | |

| Instructional program | “We can propose our own programs to the local authority.” |

| “The agencies gave us instructions to implement the programs in our communities.” | |

| “We sometimes improvise to suit our community.” | |

| Expertise | “We have managers, engineers and many other professionals in our community. They are more than able to lead; perhaps much better than the elected committee, but most say that they are too busy with work.” |

| “There are a few knowledgeable persons in the community. We encourage them to join us in coordinating activities. | |

| “Some households are more diligent than others in the practice of recycling. They are good role models.” | |

| Team leader leadership | “The local authority knows about the problems that we face in implementing the programs.” |

| “They provide us with the budget and materials.” | |

| “Frankly, I have never met with any of the officers. They usually communicate with the Chairman.” | |

| Team member leadership | “Leadership in the RACs is equally important. RACs must be able to unify community members, get them to work together.” |

| “They (RACs) must lead, mentor and inspire others.” | |

| “They should not expect the Chairman to do everything, other RAC members must step up and offer to lead.” | |

| (b) Characterization | |

| Authorized | “As management we decide on certain matters about the programs but we let the RACs take charge of their implementation” |

| “We identify the RAC and approach the Chairman to coordinate these activities.” | |

| Dispersed | “We share materials and discuss strategies with other RACs” |

| “We encourage the community to initiate their own programs.” | |

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Adoption of low-carbon lifestyle | 1.00 | ||||||||

| 2 | Organizational culture | 0.680 ** | 1.00 | |||||||

| 3 | Expertise | 0.668 ** | 0.748 ** | 1.00 | ||||||

| 4 | Vision | 0.345 ** | 0.364 ** | 0.368 ** | 1.00 | |||||

| 5 | Team member leadership | 0.422 ** | 0.418 ** | 0.555 ** | 0.519 ** | 1.00 | ||||

| 6 | Institutional framework | 0.411** | 0.574 ** | 0.453 ** | 0.356 ** | 0.448 ** | 1.00 | |||

| 7 | Consensus | 0.314 ** | 0.481 ** | 0.325 ** | 0.339 ** | 0.444 ** | 0.585 ** | 1.00 | ||

| 8 | Team leader leadership | 0.274 ** | 0.444 ** | 0.354 ** | 0.464 ** | 0.624 ** | 0.504 ** | 0.572 ** | 1.00 | |

| 9 | Instructional programs | 0.269 ** | 0.448 ** | 0.363 ** | 0.344 ** | 0.451 ** | 0.471 ** | 0.498 ** | 0.717 ** | 1.00 |

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Adoption of low-carbon lifestyle | 1.00 | ||

| 2 | Authorized | 0.273 ** | 1.00 | |

| 3 | Dispersed | 0.435 ** | 0.451 ** | 1.00 |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | B | SE B | B | B | SE B | B | B | SE B | B | B | SE B | B |

| (Constant) | 0.368 ** | 0.139 | 0.326 * | 0.157 | 0.161 | 0.193 | 0.137 | 0.214 | ||||

| Organizational culture | 0.507 | 0.075 | 0.409 ** | 0.550 | 0.078 | 0.444 ** | 0.562 | 0.079 | 0.454 ** | 0.549 | 0.086 | 0.443 ** |

| Expertise | 0.423 | 0.070 | 0.362 ** | 0.362 | 0.077 | 0.310 ** | 0.335 | 0.078 | 0.287 ** | 0.337 | 0.079 | 0.288 ** |

| Team member leadership | 0.124 | 0.060 | 0.105 * | 0.143 | 0.071 | 0.121 * | 0.139 | 0.072 | 0.118 | |||

| Instructional programs | −0.105 | 0.055 | −0.090 | −0.046 | 0.068 | −0.039 | −0.050 | 0.069 | −0.042 | |||

| Team leader leadership | −0.133 | 0.080 | −0.112 | −0.138 | 0.082 | −0.116 | ||||||

| Vision | 0.114 | 0.071 | 0.077 | 0.112 | 0.071 | 0.076 | ||||||

| Organizational framework | 0.031 | 0.075 | 0.023 | |||||||||

| Consensus | 0.004 | 0.080 | 0.003 | |||||||||

| F statistic | 162.752 | 83.943 | 57.241 | 42.698 | ||||||||

| R2 | 0.520 | 0.529 | 0.536 | 0.537 | ||||||||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.516 | 0.523 | 0.527 | 0.524 | ||||||||

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mohamed, A.; Ibrahim, Z.Z.; Silong, A.D.; Abdullah, R. Distributed Leadership in a Low-Carbon City Agenda. Sustainability 2016, 8, 715. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8080715

Mohamed A, Ibrahim ZZ, Silong AD, Abdullah R. Distributed Leadership in a Low-Carbon City Agenda. Sustainability. 2016; 8(8):715. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8080715

Chicago/Turabian StyleMohamed, Azalia, Zelina Zaiton Ibrahim, Abu Daud Silong, and Ramdzani Abdullah. 2016. "Distributed Leadership in a Low-Carbon City Agenda" Sustainability 8, no. 8: 715. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8080715

APA StyleMohamed, A., Ibrahim, Z. Z., Silong, A. D., & Abdullah, R. (2016). Distributed Leadership in a Low-Carbon City Agenda. Sustainability, 8(8), 715. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8080715