1. Introduction

The level of trust in government can be increased by promoting collaborative values between government and citizens, which eventually enhances the level of government effectiveness. Public institutions have been granted legitimacy due to the confidence of the citizens, because they gain strength for carrying out the policy [

1] (p. 1130), [

2]. When the level of trust is gradually increased, the government can actively implement the planned polices based on legitimacy, and it is possible to obtain wider support and consensus in the policy decision-making process. However, when the level of trust is decreased, the government is unable to implement the policies effectively, which may eventually lead to a vicious circle of mistrust.

Despite its significant contribution to the maintenance and development of the country, the level of trust in government by citizens as a whole appears to be very low in polls conducted all over the world since the 1990s. This phenomenon is a common trend in most Western democracies and is not confined to developing countries. Each country may be seen to be reflecting the same trend, which is a recognition of the failure of government to promote government reform, according to previous studies [

3]. Even developed countries, such as the United States and the United Kingdom, are making greater efforts to open up the government (Open Government), which ultimately enhances government transparency through the disclosure of the decision-making processes, as well as involving citizens in it.

Now, a new code is required to handle the social networking services (SNS) era with trust and moral ethics, based on the flow of undistorted and accurate information in which people are assessing the government through visible policies and practice experiences, with appropriate feedback for government services. If governments or political parties fail to show the specific route of the decision-making processes based on factual information, citizens may not trust in them, because the cross-check mechanism is becoming remarkably more sophisticated than in the past. It is not an exaggeration to say that the traditional hierarchies and social capital that were formed in regionalism, school relations and kinship are now in the process of being dismantled by a new social network capital [

4].

Previous studies initially focused on the communication aspects of individual and collective social capital, while since the 1990s, there has been an increasing interest in research that shows how social capital affects the whole of society, including democracy, economic development, country’s competitiveness [

5], policy non-compliance [

6] and organizational performance [

7]. Social capital can be divided into bonding and a bridging social capital; the former is a confidence in face-to-face relationships (thick trust) and the latter, a shallow reliance on non-face-to-face relationships (thin trust). Korea is generally reported as a more kinship-oriented society, which mainly relies on informal relationships [

2,

8].

This study asks whether such assumptions and empirical findings in previous studies are indeed still valid, even if it is obvious that a solidarity-based society attribute, such as traditional social relationships, has been a driving force for national development. However, IT powerhouse Korea has changed dramatically in various ways regarding communication and building social relationships through IT revolutions, in that bridging social capital may have a stronger influence on the level of trust in government. Choi [

9] stated that sustainability is a major subject of interest in the field of governance and e-governance in response to environments. Choi and Lee [

10] emphasized the importance of long-term sustainability in Korea’s regional innovation system and suggested that the governance approach can address sustainability. This suggests a new perspective for looking at how social capital is related in reality to the level of trust in government, which can facilitate sustainable governance or e-governance. This study, therefore, will examine to what extent the bonding and bridging social capital affects the level of trust in government. It will also examine the variances of the perception of different groups based on the degree of social cohesion and the level of trust in government. In this research, the interests, conceptual relationships between the level of trust in government and types of social capital, including a bonding social capital and a bridging social capital, will be discussed, as well as examining the possible predictor of social capital in the level of government trust. In addition, the study will examine the variances of the perception of each group based on the degree of social cohesion on the level of trust in government.

4. Analysis Results and Discussion

4.1. Results of a Multiple Regression Analysis

Table 7 shows the multiple regression results, with the independent variable and the control variable. The coefficient of determination in the regression model was 39.3 percent, indicating the model to be significant (

F-value = 11.930,

p < 0.001).

Firstly, as shown in

Table 7, bonding social capital (

B = −0.112,

p < 0.05) has a negative relationship with trust in government, while active bridging social capital (

B = 0.311,

p < 0.001), and passive bridging social capital (

B = 0.501,

p < 0.001) have a positive relationship with trust in government.

Secondly, in terms of the control variable, Female (B = 0.207, p < 0.05) in sex was positively related with trust in government, while the ages of 20s (B = −0.583, p < 0.01) and 40s (B = −0.379, p < 0.05) were negatively related to trust in government at the level of significance. In terms of the level of income, respondents between 1 to 2 million KRW (B = 1.163, p < 0.05), 3 to 4 million KRW (B = 1.389, p < 0.01), 4 to 5 million KRW (B = 1.418, p < 0.01), 5 to 6 million KRW(B = 1.501, p < 0.01), 6 to 7 million KRW (B = 1.182, p < 0.05) and 7 million KRW and over (B = 1.683, p < 0.01) were positively related to trust in government. This study involved exploratory research, and we categorized ages and incomes as narrower than traditional survey studies, because they may show different patterns of relations in an SNS society, which are more complicated and dynamic, depending on age groups and incomes.

The result shows that bonding social capital negatively affects trust in government, and it is contrary to the results of the previous studies [

2,

5]. Park

et al. [

2] and Park and Kim [

5] found that bonding social capital positively influences trust in government. We assumed that the reason for our result differing from previous studies is that we employed measurement items for indicating trust in government based on civil services. On the other hand, it supports the arguments by Putnam [

44] and Fukuyama [

17], since they found that bonding social capital, including regionalism, school relations and kinship, has a negative relationship with formal trust. Putnam [

44] argued that the critical factor responsible for the low level of Southern Italy’s social integration, compared to that of the North, is their strong blood ties and lack of horizontal relations in local communities.

Thirdly, the result shows that the two bridging social capitals are positively related to trust in government. This supports the results of previous studies, which reported the positive effects of bridging social capital [

29,

32,

35]. The bridging social capital enables people to make wide networks, join horizontal associations and evaluate government services. As Putnam [

44] mentioned, thin trust and joining horizontal associations, like bridging social capital, may provide more of a visible ground of networking and communication paths for deliberation in the process of consensus building. Interestingly, the passive bridging social capital was more positively related to the level of trust in government than the active social capital. It can be explained that the activities through citizen groups and political parties that participated as active bridge social capital may depend on their own ideologies and belief systems, which are not strongly relevant to the formation of trust in government. They act according to judgments based on ideology and belief systems, which hinders the correct evaluation of government services based on the facts and data gathered in an everyday life cycle.

4.2. ANOVA Results

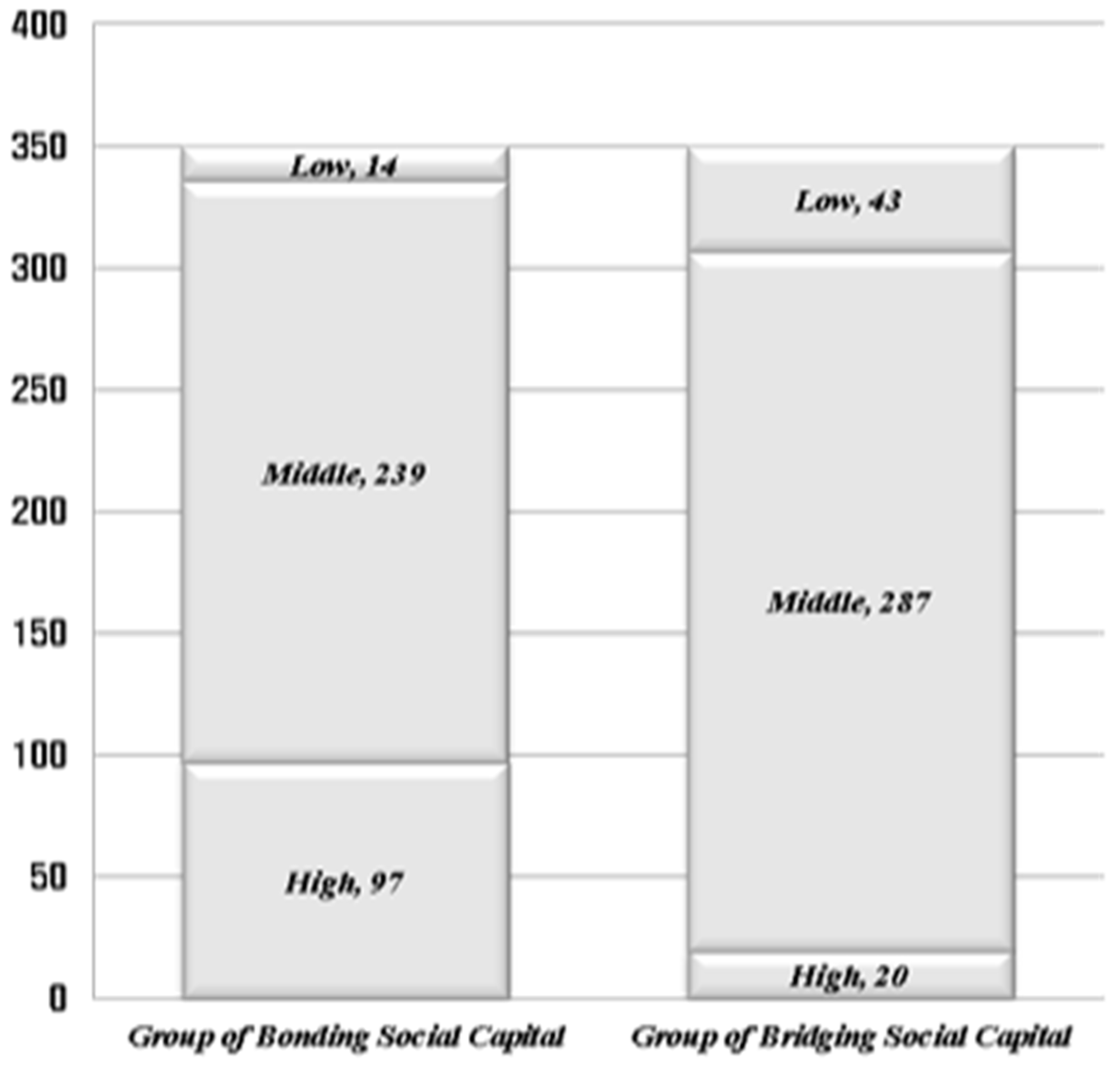

Table 8 shows the differences in the perception of trust in government among two types of social capital groups. Also

Figure 2 shows Distribution chart along with each social capital group type.

Firstly, even if in bonding social capital groups, the high group (3.28) showed the highest level of trust in government, followed by middle (3.19) and low (2.87), it is not acceptable at the level of significance (F = 2.674).

Secondly, in terms of bridging social capital groups, the high group (3.76) showed the highest level of trust in government, followed by middle (3.25) and low (2.59), and it is significantly different among bridging social capital groups (F = 32.473, p < 0.001). Additionally, to find which groups were significant, we conducted a Scheffe post hoc comparison. All three groups are significantly different in their perception of trust in government.

As shown by the ANOVA results, bonding social capital has no influence on trust in government, while bridging social capital is a determinant factor in causing a difference of trust in government, similar to the results of the multiple regression analysis above.

5. Policy Implication and Conclusions

As shown in the previous chapter, a low level of trust in government that is not rooted in the bridging or the weak-tie social capital may weaken the government’s authority to efficiently implement or deliver civic services in the era of the SNS society. If people’s low level of trust in government policies is caused by a lack of ability in government to read people’s minds and eventually resulted in blocking the normal process of feedback with support, it might cause a so-called vicious cycle of a low trust society [

45] (p. 2). This phenomenon serves to demonstrate that the traditional policy-making processes have neglected to listen to citizens’ voices and to recognize a deliberative stage in the policy-making process.

This study validates the effectiveness of government social capital of trust and helps to derive the policy implications for trust in government. In particular, by separating the social capital into two different types, it evaluates the impact on confidence in the government’s social capital.

Firstly, the regression results show that passive bridging social capital has a stronger influence on the level of trust in government, compared to groups in active social capital. We assume that active forms of bridging social capital, including volunteering in non-governmental organizations and political activities, may represent social interests in a traditional democratic society. As mentioned above, ideologies and belief systems may have more influence on the level of trust in government, as they have been developed in more closed relations, with observance and experiences, especially in relations with government institutions and political parties. The facts and data may help to increase the level of government trust when they support good governance and services with evidence. Otherwise, the development of not only institutional trust, but also trust in a whole society is prevented. If citizens trust governments less, based on the past experiences and discrimination, then they might not actively use IT-based information and data, even if the government makes great efforts to show its well-organized and sophisticated government portals and mobile content.

Secondly, the results of the multiple regression analysis imply that bonding social capital negatively influences trust in government, while bridging social capital factors have a significant impact on trust in government. Thus, the second hypothesis (H2) could be accepted. In addition, the ANOVA results showed no statistically-significant differences for the case of bonding social capital on trust in government. On the other hand, the high group has the highest level of trust in government in bridging social capital, implying that government may need to pay more attention to the groups of bridging social capital, who are more sociable, communicative and active in gathering information made available by government efforts to provide a bridging ground or platform. In that public-oriented or citizen-oriented platform, which is operated by the factual data and big data analysis, citizens may experience a new type of government service, moving away from the traditional top-down and rule-driven structures [

35].

Thirdly, the result from the female group, which showed higher levels of government trust, is an interesting finding, but it is difficult to say females have a more positive perception of government activities in general. It is also interesting that the age categories of 20s and 40s show a stronger level of distrust in government at the level of significance. As reported in the 2015 Pew survey, the younger generations generally have less confidence in the government’s directions (Pew Research Center, 2015) [

46]. It is still questionable that people of all age groups show a negative perception of government trust, although not statistically significant.

Finally, the result showing the higher the income, the higher the levels of government trust implies that it may have been extracted from the sample of the study population of the metropolitan area of Seoul, Incheon and Gyeong-gi Province. Citizens in this area could get more benefits from the government’s policies and institutions, and the quality of government services is much higher, compared to the other regions. They also have an advantage in the gathering of information and its utilization in a more advanced network environment. These results suggest that government policy for open data and sharing may have a positive impact on the increase in personal income and the development of a local economy. Opportunities for universal services for the poor need to be enlarged in order to reduce the gap between information rich and poor, because the digital divide leads to a welfare gap in a knowledge and information society. As previous studies suggested (Park and Kwon, 2013; Van Dijk, 2006), multidimensional aspects of the digital divide are needed to conceptualize the magnitude of digital gaps in social, economic, cultural and political relationships, going beyond its familiar definition [

47,

48]. They also pointed out that digital divide research has suffered from a lack of theory in the past 10 years, which has remained at a descriptive level, by limitedly emphasizing the demographics of income, education, age, sex and ethnicity. As Stolle and Hooghe (2005) were quoted as having argued in an earlier chapter, even citizens experiencing well-designed government services, who experience a lack of impartiality, will not be confident in those government organizations that discriminate against them [

27]. This raises issues regarding the mechanisms that link interpersonal and institutional trust in future studies.

Based on the above discussion and policy implications, the study provides policy recommendations for decision makers, or public officials in governmental and municipal organizations.

Firstly, governments need to make decisions based on accurate data and procedures that support the norms and legitimacy of policy implementation in a legal system. In order to promote confidence among citizens, governments and communities, policy-making processes need to be changed based on facts and impartial procedures for convincing all members of society to strongly support policy instruments and implementation. In the SNS and big data era, the level of trust in government will be lower if the level of uncertainty is high, regarding what the government is really doing, and it retains all norms and laws that do not work effectively. The capacity of individuals for information management and control has already passed beyond the limit of government, with the use of more sophisticated and customer-oriented private distribution and trading platforms (such as Facebook, Google, Amazon,

etc.). The current cycle of disconnected information flow, caused by each department and silo organization in the government sector, will worsen, if it keeps perpetuating the existing policy processes and operating mechanisms, without examining the rapidly changing environments. As the previous studies argued, even in a nation that has a well-developed e-government, a high level of government trust cannot be guaranteed, although many governments mistakenly expect that e-government services will promote trust in government. Therefore, many governments fail to transform their e-government into e-governance in which a local-based innovation system is needed to develop trust-building mechanisms in retaining users for their online public services (Choi and Lee, 2009; Teo

et al., 2003) [

10,

49].

Secondly, the authoritarian and top-down approaches in the process of policy making and implementation need to be revised. Governments need to find a new mediator or supporter to restore the ecosystem of the local community, as individuals and local communities are now easily able to control the flow of information through which people are assessing government policies, through more visible and data-oriented policy information, as well as a huge volume of cross-check feedbacks and open dialogues. For the sustainability of local communities or municipalities, the role of bridging social capital needs to be carefully examined and studied among researchers and policy communities. Even if it is obvious that bonding social capital has been a driving force for national development, Korea has dramatically changed its methods of building social relationships through advanced network technologies, and therefore, bridging-social capital as a policy middle layer may have a greater influence on the level of trust in government.

Finally, efforts to develop a transparent society through the disclosure of government information and data tailored for building an open government should be continuously expanded. We need to carefully look at the adoption of big data and the technical progress of the Internet of Things (IoT), which is enabling people to visualize the impact of government policies. Therefore, efforts for visualizing the potential of bridging social capital should be continued in order to build a positively-circulating ecosystem for maintaining the sustainability of a nation or a local community.