Inter-Organisational Coordination for Sustainable Local Governance: Public Safety Management in Poland

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methodology Research Method and Context

- (1)

- coordinating actions taken within collaboration with other units prior to, during, and after the threat

- (2)

- enterprises in each unit within common action coordination

- (3)

- the course of the common action coordination process using a random example

3. Theoretical Background

3.1. Sustainable Public Safety Management

- Local government

- Response and rescue units, including: a core unit where taking actions in response to a specific type of hazard fall into its competences; basic units which mostly respond collectively and mutually collaborate in public safety management; ancillary units which supplement actions taken by a core unit and basic units, and their knowledge and competences are critical in a specific situation

- Society: local communities and enterprises operating in a given territory

- Media: radio, television, press, Internet

- Non-governmental organisations

- Research and development units

3.2. Coordination as a Factor of Inter-Organisational Collaboration

| Characteristics | Antecedents | Features | Modes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Collaboration | Interdependence; need for resources and risk sharing; resource scarcity; previous history of efforts to collaborate; situation in which each partner has resources that other partners need [49]; trust, trustworthiness [11] | Managing resource dependencies, sharing risk [12]; Conflict management [67] | Environment (history of collaboration, collaborative group seen as a legitimate leader in the community, favourable political and social climate); membership characteristics (mutual respect, understanding, trust, ability to compromise); process and structure (members share a stake in both process and outcome, multiple layers of participation, flexibility, development of clear roles and policy guideness, adaptability, appropriate pace of development); communication (open and frequent, established informal relationships and communication links); purpose (concrete , attainable goals and objectives, shared vision; resources (sufficient funds, staff, materials, and time, skilled leadership) [48] |

| Coordination | Information [11]; perception of common objects, communication, group decision-making [58] | Regulating and managing interdependencies [68] managing uncertainties [12]; Goal decomposition [58] | Impersonal (plans, schedules, rules, procedures); personal (face-to-face communication); group (meetings) [69]; communication and decision procedures; mutual monitoring or supervisory hierarchy; group decision making; Mutual monitoring or property-rights sharing; programming; Hierarchical decision making; Integration and liaison roles; authority by expectation and residual arbitration [68]; formal (departmentalization or grouping of organizational units; centralization or decentralization of decision making; formalization and standardization; planning; output and behaviour control) and informal (lateral relations; informal communication; socialization) [70] |

3.3. Basics of Inter-Organisational Coordination in Public Safety Management

| Specification | General Theory of Coordination | Coordination in Public Safety Management |

|---|---|---|

| Substance of inter-organisational agreement | Ways of shaping interactions | Ways of shaping interactions between autonomous organizations |

| Motivation | More effectively managing task interdependencies and uncertainties | More effectively managing task interdependencies in order to identify and remove the sources and consequences of hazards |

| Concern/risks | Operational risk: inability to coordinate across organizational boundaries | Operational and situational risks: inability to coordinate joint actions of autonomous organisations in dynamic and uncertain circumstances |

| Typical positive results | Efficiency, effectiveness, flexibility/adaptiveness of joint action | Effectiveness, flexibility, adaptiveness of joint action in unique and rapidly changing situations |

| Typical failures | Omission, incompatibilities, misallocation | Inadvertent omissions leading to chaos, incompatibilities in rescue procedures, inadequate response, insufficient prevention of accumulation of hazards, increasing number of victims, additional damages |

| Remedies against failures | Hierarchies, authority, and formalisation; institutions and conventions; inter-personal linkages and liaisons | Changing hierarchical positions, integrated authority structures, improvement of rescue procedures, shared organising of training and simulations of events during the stabilisation phase, progressive adapting of regulations, advancing communication systems, creating good formal and informal relationships based on trust and organisational concern |

4. Research Results

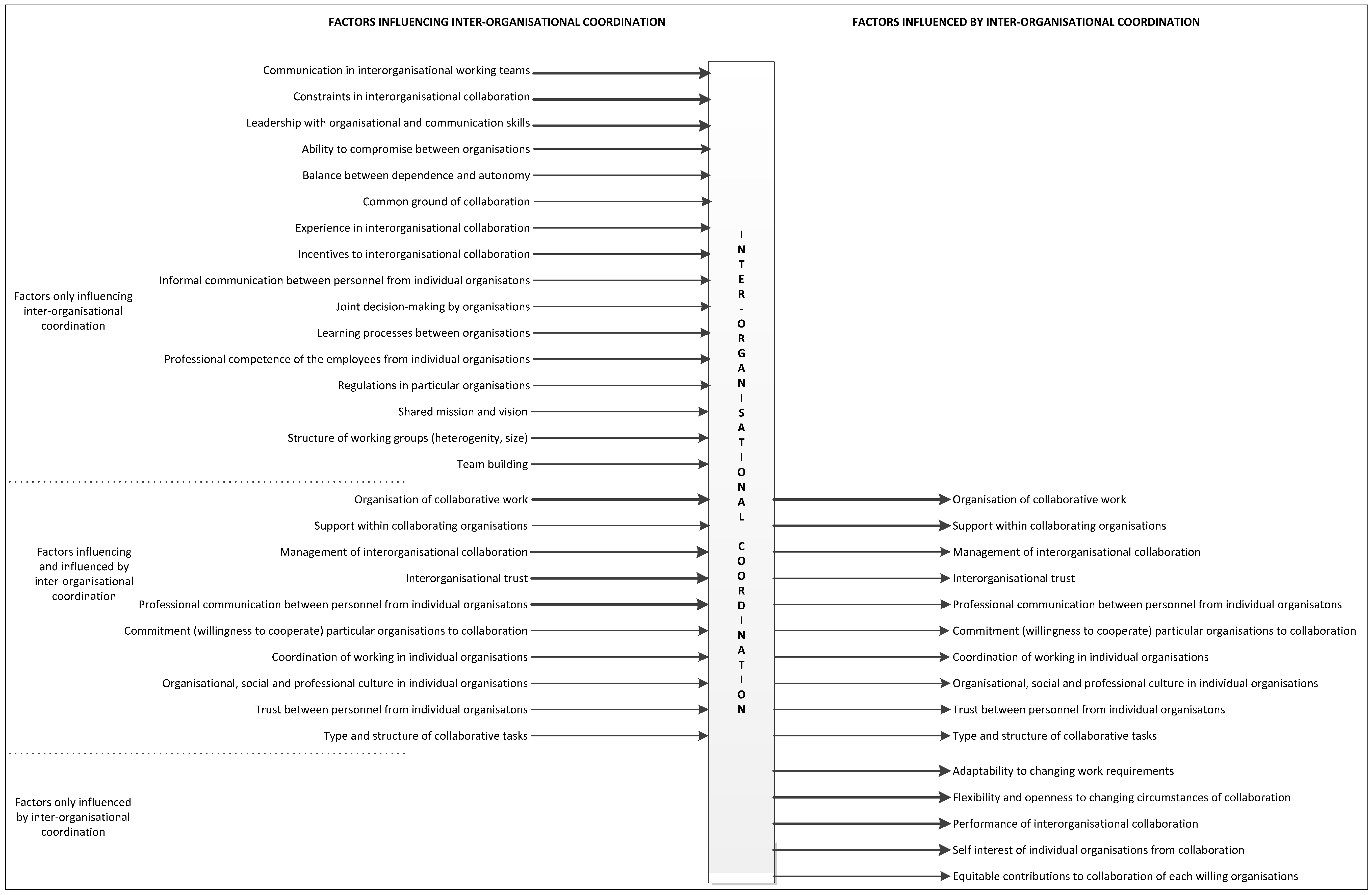

4.1. Relations between Coordination and other Instruments of Inter-Organisational Collaboration

- only impact the course of inter-organizational coordination

- both impact and are a result of inter-organizational coordination

- are only a result of inter-organizational coordination

- communication in inter-organisational working teams,

- constraints in inter-organisational collaboration,

- leadership with organisational and communication skills,

- organisation of collaborative work (e.g., time pressured, competitive, rapidly changing, stability),

- management of inter-organisational collaboration (e.g., styles, transparency of decisions and guidance),

- inter-organisational trust,

- professional communication between personnel from individual organisations.

- organisation of collaborative work,

- support within collaborating organisations,

- adaptability to changing work requirements,

- flexibility and openness to changing circumstances of collaboration,

- performance of inter-organisational collaboration,

- self interest of individual organisations from collaboration.

4.2. Inter-Organisational Coordination during Emergency Situations

- (1)

- prepare scenarios for potential situations, analyses, weather forecasts, collect information, anticipate demand;

- (2)

- calculate forces and resources, assess potential, analyse situations, prepare proposals for disposing forces depending on the demand, examine potential for requesting external forces;

- (3)

- contribute to the formulation of solutions intended to accomplish operations, raise forces, dislocate forces, put forces into operation, continue monitoring the situation and its reporting;

- (4)

- monitor the efficacy of the formulated solutions, participate in the work of military staff and teams, monitor the situation’s progress, collaborate with commanders with regard to specific actions;

- (5)

- control efficacy of operations conducted by operational groups, verify information handed over, e.g., by phone, with the actual situation.

- (1)

- handle alarm reports, excluding fire signalisation systems,

- (2)

- register and store data regarding alarm reports, including phone recordings with the complete alarm report, personal data of the reporting person and other persons indicated when receiving the report, information on the incident site and its type and shortened description of the event for the period of 3 years;

- (3)

- conduct analyses related to functioning of the system in the area handled by the centre and producing statistics with regard to numbers, types, and response time for alarm reports;

- (4)

- collaborate and exchange information with emergency coordination centres;

- (5)

- exchange information and data, excluding personal data, for the purposes of analyses with the Police, National Fire Service, administrators of medical rescue teams, and entities which phone numbers are handled within the system.

- (1)

- Maintaining and operating early warning towers and other early warning dissemination equipments

- (2)

- Dissemination of early warning messages and ensuring reception at remote vulnerable villagers

- (3)

- Coordination of donor assistance to strengthen capacity of technical agencies for early warning

- (4)

- Initiating awareness on activities related to early warning among various agencies and the public

- (5)

- Guiding district disaster management units in coordinating and implementing warning dissemination-related activities in the province, district, and local authority levels.

- integrity of actions: the enterprises of each organisation are coherent and mutually complementary, while efficiency may be achieved only within mutual realisation of tasks;

- interdependence: each organisation is mutually dependent both in the scope of conducting actions, transferring information, as well as managing resources;

- mutuality: mutual enterprises are based on relations between each organisation;

- multiplicity: there are many possibilities of coordinating actions within one enterprise;

- adaptability: methods of coordination are adapted to existing conditions.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

- (1)

- Inter-organisational coordination depends to a large extent on organisational and relational conditions, which occur between collaborating units. They include among other such factors as: communication in inter-organisational working teams, constraints in inter-organisational collaboration, leadership with organisational and communication skills, organisation of collaborative work (e.g., time pressured, competitive, rapidly changing, stability), management of inter-organisational collaboration (e.g., styles, transparency of decisions, and guidance), inter-organisational trust, and professional communication between personnel from individual organisations.

- (2)

- Coordination in public safety management is protean. During stabilization it is carried out by public administration and it involves determination of preventive operations. Some ways of that coordination can be applied in other areas of sustainable local government. However during the realisation phase the person in charge of rescue actions coordinates activities within the incident site. Outside the incident site the coordination function is fulfilled by emergency coordination centres. This solution is the result of complexity embedded in the unique situation and efforts to be undertaken in face of hazard. Such coordination, particularly creation of formal and informal relationships based on trust and organisational concern, can be used in sheer inter-organisational collaboration.

- (3)

- The principal features of inter-organisational coordination considered with regard to collaborated management are: integrity of actions, interdependence, mutuality, complexity, and adaptiveness to unique and rapidly changing situations. At the same time, inter-organisational coordination is a result of legal, organisational, social, and situational conditions. Features of inter-organisational coordination have a considerable impact on the level of sustainable public safety management.

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Van Wassenhove, L.N. Humanitarian aid logistics: Supply chain management in high gear. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 2006, 57, 475–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymczak, M.; Sienkiewicz-Małyjurek, K. Information in the city traffic management system. The analysis of the use of information sources and the assessment in terms of their usefulness for city routes users. LogForum 2011, 7, 37–50. [Google Scholar]

- Slabbert, A.D.; Ukpere, W.I. Poverty as a transient reality in a globalised world: An economic choice. Int. J. Soc. Econ. 2011, 38, 858–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, N. Economic inequality and poverty: Where do we go from here? Int. J. Sociol. Soc. Policy 2010, 30, 127–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sienkiewicz-Małyjurek, K. Spatial and organisational conditions of public safety in cities. In Current Problems of Regional Development, Proceedings of the International Scientific Conference on Hradec Economical Days 2008: A Strategy for Development of the Region and the State Location, University Hradec Kralove, Czech Republic, 5–6 February 2008; Jedlicka, P., Ed.; pp. 95–99.

- Jabłoński, A. Wieloparadygmatyczność w zarządzaniu a trwałość modelu biznesu przedsiębiorstwa. Studia i Prace Kolegium Zarządzania i Finansów Szkoły Głównej Handlowej w Warszawie 2014, 139, 51–72. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Kozłowski, S. Polska droga do zrównoważonego rozwoju. In Rozwój zrównoważony na szczeblu krajowym, regionalnym i lokalnym—doświadczenia polskie i możliwości ich zastosowania na Ukrainie; Kozłowski, S., Haładyj, A., Eds.; KUL: Lublin, Poland, 2006; pp. 159–166. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Kożuch, B.; Sienkiewicz-Małyjurek, K. Collaborative networks as a basis for internal economic security in sustainable local governance. The case of Poland. In The Economic Security of Business Transactions. Management in Business; Raczkowski, K., Schneider, F., Eds.; Chartridge Books Oxford: Oxford, UK, 2013; pp. 313–328. [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary, R.; Vij, N. Collaborative Public Management: Where Have We Been and Where Are We Going? Am. Rev. Public Adm. 2012, 42, 507–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Himmelman, A.T. On coalitions and the transformation of power relations: Collaborative betterment and collaborative empowerment. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2001, 29, 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feiock, R.C.; Lee, I.W.; Park, H.J. Administrators’ and Elected Officials’ Collaboration Networks: Selecting Partners to Reduce Risk in Economic Development. Public Adm. Rev. 2012, 72, S58–S68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulati, R.; Wohlgezogen, F.; Zhelyazkov, P. The Two Facets of Collaboration: Cooperation and Coordination in Strategic Alliances. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2012, 6, 531–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raposo, A.B.; Fuks, H. Defining Task Interdependencies and Coordination Mechanisms for Collaborative Systems. In Cooperative Systems Design; Blay-Fornarino, M., Pinna-Dery, A.M., Schmidt, K., Zaraté, P., Eds.; IOS Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2002; pp. 88–103. [Google Scholar]

- Leonard, H.B.; Howitt, A.M. Organising Response to Extreme Emergencies: The Victorian Bushfires of 2009. Aust. J. Public Adm. 2010, 69, 372–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, R. All the King’s horses and all the King’s men: Putting New Zealand’s public sector back together again. Int. Public Manag. Rev. 2003, 4, 41–58. [Google Scholar]

- Comfort, L.K. Crisis Management in Hindsight: Cognition, Communication, Coordination, and Control. Public Adm. Rev. 2007, 67, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, H.B.; Howitt, A.M. Katrina as prelude: Preparing for and responding to Katrina-Class Disturbances in the United States—Testimony to U.S. Senate Committee, 8 March 2006. J. Homel. Secur. Emerg. Manag. 2006, 3, 1547–7355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comfort, L.K.; Kapucu, N. Inter-organizational coordination in extreme events: The World Trade Center attacks, 11 September 2001. Nat. Hazards 2006, 39, 309–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharosa, N.; Lee, J.; Janssen, M. Challenges and obstacles in sharing and coordinating information during multi-agency disaster response: Propositions from field exercises. Inf. Syst. Front. 2010, 12, 49–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panday, P.K. Policy implementation in urban Bangladesh: Role of intra-organizational coordination. Public Organ. Rev. 2007, 7, 237–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meek, J.W. Nuances of Metropolitan Cooperative Networks. Public Adm. Rev. 2012, 72, S68–S69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Sharman, R.; Chakravarti, N.; Rao, H.R.; Upadhyaya, S.J. Emergency response information system interoperability: Development of chemical incident response data model. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2008, 9, 1–54. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, R.; Sharman, R.; Rao, H.R.; Upadhyaya, S.J. Coordination In Emergency Response Management, Developing a framework to analyze coordination patterns occurring in the emergency response life cycle. Commun. ACM 2008, 51, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melin, U.; Axelsson, K. Understanding Organizational Coordination and Information Systems—Mintzberg’s Coordination Mechanisms Revisited and Evaluated. Available online: http://aisel.aisnet.org/ecis2005/115/ (accessed on 18 December 2015).

- Gittell, J.H. Relationships between service providers and their impact on customers. J. Sci. Res. 2002, 4, 299–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gittell, J.H. Relational coordination: coordinating work through relationships of shared goals, shared knowledge and mutual respect. In Relational Perspectives in Organisational Studies: A Research Companion; Kyriakidou, O., Özbilgin, M.F., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishers: Cheltenham, UK, 2006; pp. 74–94. [Google Scholar]

- Kożuch, B.; Sienkiewcz-Małyjurek, K. Factors of effective inter-organisational collaboration: A framework for public management. Transylvanian Review of Administrative Sciences, forthcoming.

- Government Centre for Security. Act of 26 April 2007 on the Crisis Management. Available online: http://rcb.gov.pl/eng/wp-content/uploads/2011/03/ACT-on-Crisis-Management-final-version-31-12-2010.pdf (accessed on 25 January 2016).

- Kożuch, B.; Sienkiewicz-Małyjurek, K. Information sharing in complex systems: A case study on public safety management. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 213, 722–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waugh, W.L.; Streib, G. Collaboration and Leadership for Effective Emergency Management. Public Adm. Rev. 2006, 66, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapucu, N.; Arslan, T.; Demiroz, F. Collaborative emergency management and national emergency management network. Disaster Prev. Manag. 2010, 19, 452–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapucu, N. Disaster and emergency management systems in urban areas. Cities 2012, 29, S41–S49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boin, A.; Hart, P. Organising for Effective Emergency Management: Lessons from Research. Austr. J. Public Adm. 2010, 69, 357–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choenni, S.; Leertouwer, E. Public Safety Mashups to Support Policy Makers. In Electronic Government and the Information Systems Perspective, Proceedings of the First International Conference EGOVIS 2010, Bilbao, Spain, 31 August–2 September 2010; Andersen, K.M., Francesconi, E., van Engers, A.G.T.M., Eds.; Springer-Verlag: Berlin Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 234–248. [Google Scholar]

- Sienkiewicz-Małyjurek, K. Rola samorządów lokalnych w kształtowaniu bezpieczeństwa publicznego. Samorz. Teryt. 2010, 7–8, 123–139. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Tomasino, A.P. Public Safety Networks as a Type of Complex Adaptive System. In Unifying Themes in Complex Systems, Proceedings of the Eighth International Conference on Complex Systems, Volume VIII, Boston, MA, 26 June–1 July 2011; Sayama, H., Minai, A., Braha, D., Bar-Yam, Y., Eds.; New England Complex Systems Institute Series on Complexity, NECSI Knowledge Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2011; pp. 1350–1364. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, C.B.; Dias, M.; Fedorowicz, J.; Jacobson, D.; Vilvovsky, S.; Sawyer, S.; Tyworth, M. The formation of inter-organizational information sharing networks in public safety: Cartographic insights on rational choice and institutional explanations. Inf. Polity 2009, 14, 13–29. [Google Scholar]

- Kożuch, B.; Sienkiewicz-Małyjurek, K. Collaborative Performance In Public Safety Management Process. In Transdisciplinary and Communicative Action, Proceedings of the 5th International Conference Lumen 2014, Targoviste, Romania, 21–22 November 2014; Frunza, A., Ciulei, T., Sandu, A., Eds.; Medimond S.r.l.: Bologna, Italy, 2015; pp. 401–409. [Google Scholar]

- Kożuch, B.; Sienkiewicz-Małyjurek, K. Mapowanie procesów współpracy międzyorganizacyjnej na przykładzie działań realizowanych w bezpieczeństwie publicznym. Zarządzanie Publiczne, 2015. forthcoming. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Sienkiewicz-Małyjurek, K.; Kożuch, B. System zarządzania bezpieczeństwem publicznym w ujęciu teorii złożoności. Opracowanie modelowe. Bezpieczeństwo i Technika Pożarnicza 2015, 37, 33–43. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Kożuch, B.; Sienkiewicz-Małyjurek, K. New Requirements for Managers of Public Safety Systems. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 149, 472–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grudzewski, W.M.; Hejduk, I.K.; Sankowska, A.; Wańtuchowicz, M. Sustainability w biznesie, czyli przedsiębiorstwo przyszłości, zmiany paradygmatów i koncepcji zarządzania; Wydawnictwo Poltext: Warszawa, Poland, 2010. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Mah, D.N.; Hills, P. Collaborative governance for sustainable development: Wind resource assessment in Xinjiang and Guangdong Provinces, China. Sustain. Dev. 2012, 20, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Røiseland, A. Understanding local governance: Institutional forms of collaboration. Public Adm. 2011, 89, 879–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Considine, M. Governance networks and the question of transformation. Public Adm. 2013, 91, 438–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, I.W.; Feiock, R.C.; Lee, Y. Competitors and Cooperators: A Micro-Level Analysis of Regional Economic Development Collaboration Networks. Public Adm. Rev. 2012, 72, 253–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, R. Collaboration as a Pathway for Sustainability. Sustain. Dev. 2007, 15, 370–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattessich, P.W.; Murray-Close, M.; Monsey, B.R. Collaboration: What Makes It Work; Amherst H. Wilder Foundation: Saint Paul, MN, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Thomson, A.M.; Perry, J.L. Collaboration process: Inside the black box. Public Adm. Rev. 2006, 66, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arya, B.; Lin, Z. Understanding collaboration outcomes from an extended resource-based view perspective: The roles of organizational characteristics, partner attributes, and network structures. J. Manag. 2007, 33, 697–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, M.T.; Nohria, N. How to build collaborative advantage. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2004, 46, 4–12. [Google Scholar]

- Hardy, C.; Phillips, N.; Lawrence, T.B. Resources, Knowledge and Influence: The Organizational Effects of Interorganizational Collaboration. J. Manag. Stud. 2003, 40, 321–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, W.W.; Koput, K.W.; Smith-Doerr, L. Interorganizational collaboration and the locus of innovation: Networks of learning in biotechnology. Adm. Sci. Q. 1996, 41, 116–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berlin, J.M.; Carlström, E.D. Why is collaboration minimised at the accident scene? A critical study of a hidden phenomenon. Disaster Prev. Manag. 2011, 20, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, F.M. Interagency Collaborative Arrangements and Activities: Types, Rationales, Considerations; Congressional Research Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- McGuire, M. Collaborative Public Management: Assessing What We Know and How We Know It. Public Adm. Rev. 2006, 66, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrault, E.; McClelland, R.; Austin, C.; Sieppert, J. Working Together in Collaborations: Successful Process Factors for Community Collaboration. Adm. Soc. Work 2011, 5, 282–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malone, T.W.; Crowston, K. What is coordination theory and how can it help design cooperative work systems. In Proceedings of the Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work, Los Angeles, CA, USA, 7–10 October 1990.

- Hartgerink, J.M.; Cramm, J.M.; Bakker, T.J.E.M.; van Eijsden, R.A.M.; Mackenbach, J.P.; Nieboer, A.P. The importance of relational coordination for integrated care delivery to older patients in the hospital. J. Nurs. Manag. 2014, 22, 248–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hossain, L.; Uddin, S. Design patterns: Coordination in complex and dynamic environments. Disaster Prev. Manag. 2012, 21, 336–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malone, T.W.; Crowston, K. The interdisciplinary study of coordination. ACM Comput. Surv. (CSUR) 1994, 26, 87–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lie, A. Coordination processes and outcomes in the public service: The challenge of inter-organizational food safety coordination in Norway. Public Adm. 2011, 89, 401–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bond, J.B.; Gittell, J.H. Cross-agency coordination of offender reentry: Testing collaboration outcomes. J. Crim. Justice 2010, 38, 118–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.; Hesterly, W.S.; Borgatti, S.P. A General Theory of Network Governance: Exchange Conditions and Social Mechanisms. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1997, 22, 911–945. [Google Scholar]

- De Pablos Heredero, C.; Haider, S.; García Martínez, A. Relational coordination as an indicator of teamwork quality: Potential application to the success of e-learning at universities. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Learn. 2015, 10, 4–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Provan, K.G.; Kenis, P. Modes of Network Governance: Structure, Management, and Effectiveness. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2008, 18, 229–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, E.J. Collaboration and Confrontation in Interorganizational Coordination: Preparing to Respond to Disasters. Available online: https://docs.google.com/viewer?url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.ideals.illinois.edu%2Fbitstream%2Fhandle%2F2142%2F50617%2FElizabeth_Carlson.pdf%3Fsequence%3D1 (accessed on 11 January 2016).

- Grandori, A. An Organizational Assessment of Interfirm Coordination Modes. Organ. Stud. 1997, 18, 897–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van De Ven, A.H.; Delbecq, A.L.; Koenig, R.J. Determinants of coordination modes within organizations. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1976, 41, 322–338. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez, J.I.; Jarillo, J.C. The Evolution of Research on Coordination Mechanisms in Multinational Corporations. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1989, 20, 489–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, L.; Kuti, M. Disaster response preparedness coordination through social networks. Disasters 2010, 34, 755–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mintzberg, H. The Structuring of Organizations; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Drabek, T.E. Community Processes: Coordination. In Handbook of Disaster Research; Rodríguez, H., Quarantelli, E.L., Dynes, R.R., Eds.; Springer Science + Business Media: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 217–233. [Google Scholar]

- Abbasi, A.; Owen, C.; Hossain, L.; Hamra, J. Social connectedness and adaptive team coordination during fire events. Fire Saf. J. 2013, 59, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, J.C.; Morris, E.D.; Jones, D.M. Reaching for the Philosopher’s Stone: Contingent Coordination and the Military’s Response to Hurricane Katrina. Public Adm. Rev. 2007, 67, 94–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comfort, L.; Dunn, M.; Johnson, D.; Skertich, R.; Zagorecki, A. Coordination in complex systems: Increasing efficiency in disaster mitigation and response. Int. J. Emerg. Manag. 2004, 2, 63–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapucu, N. Interorganizational Coordination in Dynamic Context: Networks in Emergency Response Management. Connections 2005, 26, 33–48. [Google Scholar]

- Wise, C.R. Organizing for Homeland Security after Katrina: Is Adaptive Management What’s Missing? Public Adm. Rev. 2006, 66, 302–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolland, J.M.; Wilson, J.V. Three Faces of Integrative Coordination: A Model of Interorganizational Relations in Community-Based Health and Human Services. HSR Health Services Res. 1994, 29, 341–366. [Google Scholar]

- Leung, Z.C.S. Boundary Spanning in Interorganizational Collaboration. Adm. Soc. Work 2013, 37, 447–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, H.; Pettitt, M.; Wilson, J.R. Factors of collaborative working: A framework for a collaboration model. Appl. Ergon. 2012, 43, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ales, M.W.; Rodrigues, S.B.; Snyder, R.; Conklin, M. Developing and Implementing an Effective Framework for Collaboration: The Experience of the CS2day Collaborative. J. Contin. Educ. Health Prof. 2011, 31, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ansell, C.; Gash, A. Collaborative Governance in Theory and Practice. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2007, 18, 543–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B. Antecedents or Processes? Determinants of Perceived Effectiveness of Interorganizational Collaborations for Public Service Delivery. Int. Public Manag. J. 2010, 13, 381–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daley, D.M. Interdisciplinary Problems and Agency Boundaries: Exploring Effective Cross-Agency Collaboration. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2009, 19, 477–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emerson, K.; Nabatchi, T.; Balogh, S. An integrative framework for collaborative governance. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2011, 22, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedorowicz, J.; Gogan, J.L.; Williams, C.B. A collaborative network for first responders: Lessons from the CapWIN case. Gov. Inf. Q. 2007, 24, 785–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, M. Determining factors in the success of strategic alliances: An empirical study performed in Portuguese firms. Eur. J. Int. Manag. 2011, 5, 608–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, C.A.; Balmer, J.T.; Mejicano, G.C. Factors Contributing to Successful Interorganizational Collaboration: The Case of CS2day. J. Contin. Educ. Health Prof. 2011, 31, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raišienė, A.G. Sustainable Development of Inter-Organizational Relationships and Social Innovations. J. Secur. Sustain. Issues 2012, 2, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranade, W.; Hudson, B. Conceptual issues in inter-agency collaboration. Local Gov. Stud. 2003, 29, 32–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The National Headquarters of the State Fire Service of Poland. Biuletyn Informacyjny Państwowej Straży Pożarnej za Rok 2010. Available online: http://www.straz.gov.pl/aktualnosci/biuletyn_roczny_psp_za_rok_2010 (accessed on 26 January 2016). (In Polish)

- Reddy, M.C.; Paul, S.A.; Abraham, J.; McNeese, M.; DeFlitch, C.; Yen, J. Challenges to effective crisis management: Using information and communication technologies to coordinate emergency medical services and emergency department teams. Int. J. Med. Inf. 2009, 78, 259–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Commission; Humanitarian Aid and Civil Protection. Emergency Response Coordination Centre, ECHO Factsheet. Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/echo/files/aid/countries/factsheets/thematic/ERC_en.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2015).

- Internetowy System Aktów Prawnych. Ustawa z Dnia 22 Listopada 2013 r. o Systemie Powiadamiania Ratunkowego (Dz.U. 2013 poz. 1635). Available online: http://isap.sejm.gov.pl/DetailsServlet?id=WDU20130001635 (accessed on 27 January 2016). (In Polish)

- Asees, M.S. Tsunami Disaster Prevention in Sri Lanka. Available online: http://www. jamco.or.jp/en/symposium/21/3/ (accessed on 28 September 2015).

- Sienkiewicz-Małyjurek, K. The Flow of Information About the Actions Required in Emergency Situations: Issues in Urban Areas in Poland. Int. J. Soc. Sustain. Econ. Soc. Cult. Context 2013, 8, 61–71. [Google Scholar]

- Aedo, I.; Díaz, P.; Carroll, J.M.; Convertino, G.; Rosson, M.B. End-user oriented strategies to facilitate multi-organizational adoption of emergency management information systems. Inf. Process. Manag. 2010, 46, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.B.; Wang, Y.; Wang, W.M.; Cheung, C.F. An unstructured information management system (UIMS) for emergency management. Expert Syst. Appl. 2012, 39, 12743–12758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juan, L.J.; Li, Q.; Liua, C.; Khana, S.U.; Ghani, N. Community-based collaborative information system for emergency management. Comput. Oper. Res. 2014, 42, 116–124. [Google Scholar]

- Grandori, A.; Soda, G. Inter-firm networks: Antecedents, mechanisms and forms. Organ. Stud. 1995, 16, 183–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardet, E.; Mothe, C. The dynamics of coordination in innovation networks. Eur. Manag. Rev. 2011, 8, 213–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gittell, J.H.; Weiss, L. Coordination Networks Within and Across Organizations: A Multi-level Framework. J. Manag. Stud. 2004, 41, 127–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons by Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kożuch, B.; Sienkiewicz-Małyjurek, K. Inter-Organisational Coordination for Sustainable Local Governance: Public Safety Management in Poland. Sustainability 2016, 8, 123. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8020123

Kożuch B, Sienkiewicz-Małyjurek K. Inter-Organisational Coordination for Sustainable Local Governance: Public Safety Management in Poland. Sustainability. 2016; 8(2):123. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8020123

Chicago/Turabian StyleKożuch, Barbara, and Katarzyna Sienkiewicz-Małyjurek. 2016. "Inter-Organisational Coordination for Sustainable Local Governance: Public Safety Management in Poland" Sustainability 8, no. 2: 123. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8020123

APA StyleKożuch, B., & Sienkiewicz-Małyjurek, K. (2016). Inter-Organisational Coordination for Sustainable Local Governance: Public Safety Management in Poland. Sustainability, 8(2), 123. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8020123