Income Diversification: A Strategy for Rural Region Risk Management

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Income Diversification as a Risk Management Strategy

3. Data and Methods

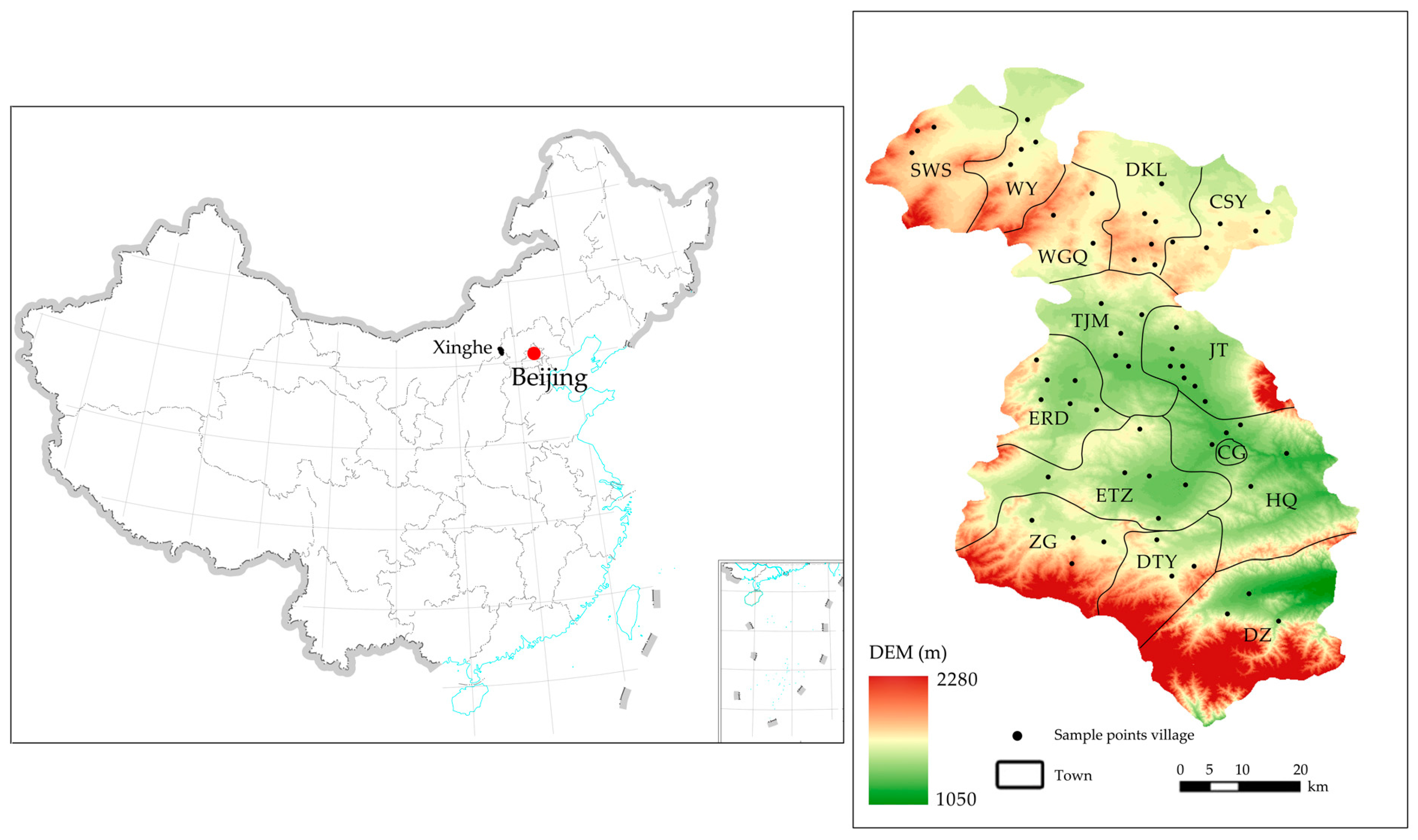

3.1. Study Area

3.2. Data Collection

3.3. Income Diversification Indices (IDIs)

4. Results and Discussion

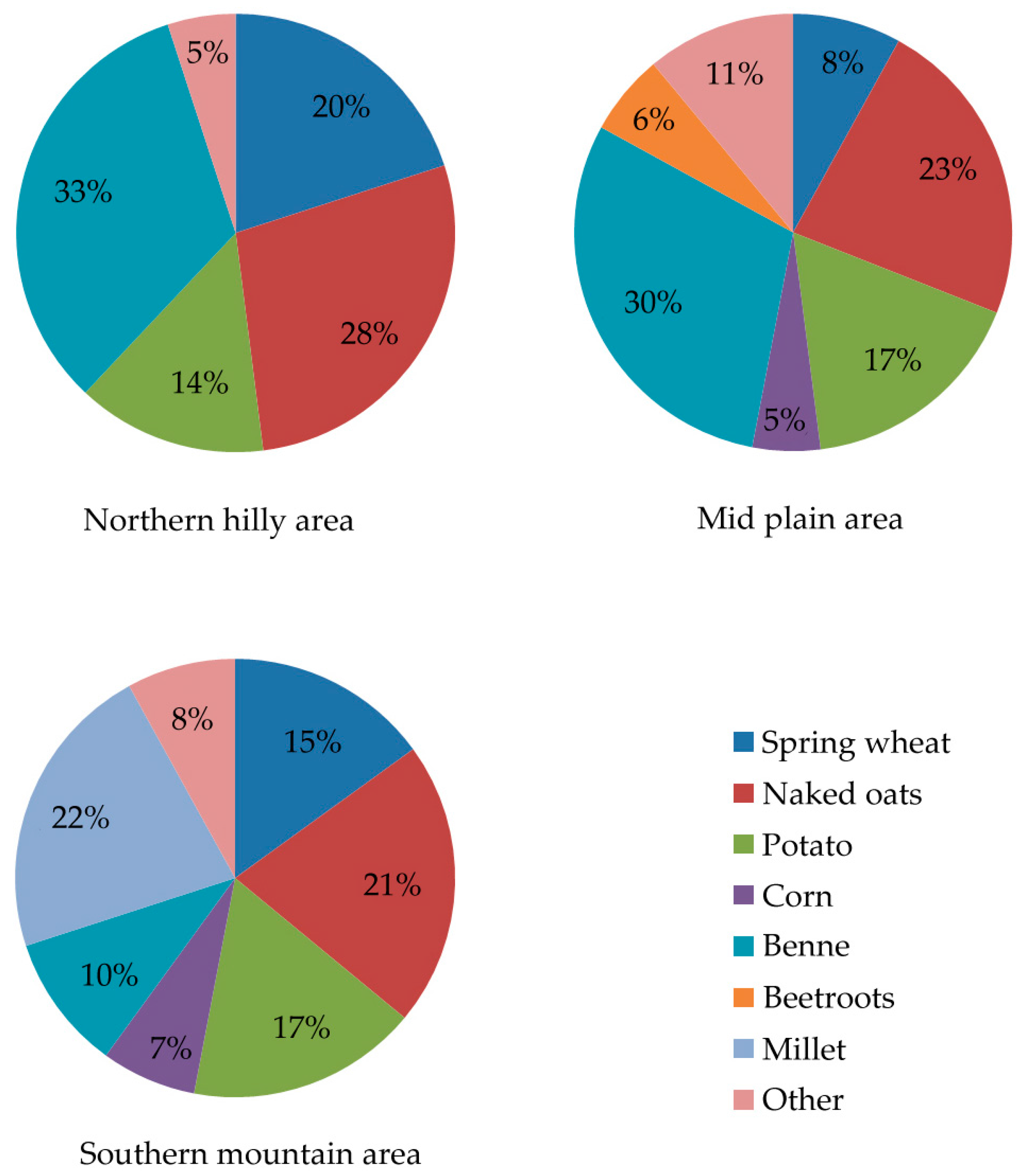

4.1. Farm Household Income Generation Activities

4.2. Determinants of Income Diversity

4.3. Spatial Difference of Income Diversification at The Town Scale

4.4. Why Rural Households Diversify Their Income Sources?

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Agricultural Drought Survey Questionnaire

- No.:

- Location:

- Date:

- Respondents:

- (1)

- Household structure

Member Relationship with Respondent Gender Age Education Level Jobs Health Status Relationship with Respondent: 1—Grandparents; 2-Parents; 3—Children; 4—Brothers and sisters; 5—Spouse; 6—Friend; Gender: 1—Male; 2—Female; Education level: 1—illiteracy; 2—Primary School; 3—High School; 4—college; Jobs: 1—Farmer; 2—Wage Worker; 3—Rural Retailer; 4—Local government staff; 5—Student; Health status: 1—good; 2—illness. - (2)

- (3)

- Household income—expenditure

- (a)

- (b)

- (4)

- (5)

References

- Leng, G.; Tang, Q.; Rayburg, S. Climate change impacts on meteorological, agricultural and hydrological droughts in China. Glob. Planet Chang. 2015, 126, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Water Resources of the People’s Republic of China (MWR). Bulletin of Flood and Drought Disaster in China; China Water Power Press: Beijing, China, 2014; pp. 1–2.

- Wilhite, D.A. Drought. In Encyclopedia of Earth System Science; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1992; pp. 81–92. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett, C.B.; Reardon, T.; Webb, P. Nonfarm income diversification and household livelihood strategies in rural Africa: concepts, dynamics, and policy implications. Food Policy 2001, 26, 315–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meert, H.; van Huylenbroeck, G.; Vernimmen, T.; Bourgeois, M.; Van Hecke, E. Farm household survival strategies and diversification on marginal farms. J. Rural Stud. 2005, 21, 81–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niehof, A. The significance of diversification for rural livelihood systems. Food Policy 2004, 29, 321–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, F. Household strategies and rural livelihood diversification. J. Dev. Stud. 1998, 35, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watete, P.W.; Makau, W.K.; Njoka, J.T.; AderoMacOpiyo, L. Are there options outside livestock economy? Diversification among households of northern Kenya. Pastoralism 2016, 6, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guvele, C.A. Gains from crop diversification in the Sudan Gezira scheme. Agric. Syst. 2001, 70, 319–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, F. Rural Household and Diversify in Developing Countries; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2000; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Francis, E. Making a Living, Changing Livelihoods in Rural Africa; Rout ledge: London, UK, 2000; pp. 1–99. [Google Scholar]

- Slater, R. Differentiation and diversification: Changing livelihoods in Qwaqwa, South Africa, 1970–2000. J South. Afr. Stud. 2002, 28, 599–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Démurger, S.; Fournier, M.; Yang, W. Rural households’ decisions towards income diversification: Evidence from a township in Northern China. China Econ. Rev. 2010, 21, S32–S44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ersado, L. Income Diversification in Zimbabwe: Welfare Implications from Urban and Rural Areas; FCND Discussion Paper No. 152; International Food Policy Research Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2003; pp. 1–50. [Google Scholar]

- Berzborn, S. The household economy of pastoralists and wage-laborers in the Richtersveld, South Africa. J. Arid Environ. 2007, 70, 672–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, J.H.; Wang, J.A.; Liu, Z.; Jia, H.C.; Gao, L.; Gao, L.L.; Zhang, F. Drought resilience in view of income diversity of peasant household: A case study on Xinghe County, Inner Mongolia. J. Nat. Disasters 2008, 17, 122–126. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Xinghe County. Available online: http://www.xinghe.gov.cn/channel/xinghe/col23268f.html (accessed on 5 September 2016).

- Zhou, H.J.; Wang, J.A.; Wan, J.H.; Jia, H.C. Resilience to natural hazards: A geographic perspective. Nat Hazards 2010, 53, 21–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Brauw, A.; Rozelle, S. Reconciling the returns to education in off-farm wage employment in rural China. Rev. Dev. Econ. 2008, 12, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Brauw, A.; Huang, J.; Rozelle, S.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Y. The evolution of China's rural labor market during the reforms. J. Comp. Econ. 2002, 30, 353–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Risk Modeling Concepts Relating to the Design and Rating of Agricultural Insurance Contracts. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=625269 (accessed on 1 August 2004).

- Charpentier, A. Insurability of climate risks. Geneva Pap. Risk Insur. Issues Pract. 2008, 33, 91–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.J.; Wang, W.Y.; Wang, X.M. Adapting agriculture to the drought hazard in rural China: Household strategies and determinants. Nat. Hazards 2016, 82, 1609–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.J.; Liu, Y.; Bai, W.; Liu, B.C. Evaluation of the crop insurance management for soybean risk of natural disasters in Jilin Province, China. Nat. Hazards 2015, 76, 587–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, M.; Routray, J.K.; Saeed, M. Determinants of farmers’ choice of coping and adaptation measures to the drought hazard in northwest Balochistan, Pakistan. Nat. Hazards 2014, 73, 1451–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makate, C.; Wang, R.; Makate, M.; Mango, N. Crop diversification and livelihoods of smallholder farmers in Zimbabwe: Adaptive management for environmental change. Springerplus 2016, 5, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Landform Types | Survey Towns | Number of Sample Villages | Number of Sample Rural Households |

|---|---|---|---|

| North hilly area | Saiwusu (SWS) | 3 | 14 |

| Wuyi (WY) | 4 | 19 | |

| Wuguquan (WGQ) | 3 | 14 | |

| Dakulian (DKL) | 6 | 20 | |

| Caosiyao (CSY) | 5 | 21 | |

| Mid plains area | Taijimiao (TJM) | 5 | 27 |

| Tuanjie (TJ) | 7 | 34 | |

| Eerdong (ERD) | 6 | 27 | |

| South mountain area | Ertaizi (ETZ) | 6 | 25 |

| Haoqian (HQ) | 5 | 21 | |

| Zhanggao (ZG) | 4 | 37 | |

| Datongyao (DTY) | 3 | 14 | |

| Dianzi (DZ) | 3 | 18 |

| Category | Types | Number of Samples |

|---|---|---|

| Farm income | Crop income | 195 |

| Potato income | 111 | |

| Vegetable income | 36 | |

| Livestock income | 151 | |

| Off-farm income | Non-farm wage income | 155 |

| State grants | 185 |

| Variable | Coefficient | Std Error | t |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age of household head | −0.007 | 0.011 | −0.482 |

| Education of household head (years) | 0.024 | 0.008 | 2.985 ** |

| Household size | 0.134 | 0.017 | 7.528 ** |

| Proportion children of household | −0.008 | 0.002 | −3.093 ** |

| Proportion older of household | −0.006 | 0.006 | −2.072 * |

| Farm size | 0.273 | 0.062 | 1.986 * |

| Share of land irrigated | −0.459 | 0.118 | −3.022 ** |

| Landform Types | Surveyed Towns | Idiv | Idep | Average Number of Income Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| North hilly area | Saiwusu (SWS) | 0.572 | 0.643 | 2.286 |

| Wuyi (WY) | 0.685 | 0.563 | 2.421 | |

| Wuguquan (WGQ) | 0.605 | 0.630 | 2.429 | |

| Dakulian (DKL) | 0.664 | 0.602 | 2.550 | |

| Caosiyao (CSY) | 0.507 | 0.685 | 1.952 | |

| Mid plains area | Taijimiao (TJM) | 1.172 | 0.366 | 4.037 |

| Tuanjie (TJ) | 0.834 | 0.513 | 2.912 | |

| Eerdong (ERD) | 0.826 | 0.510 | 2.815 | |

| South mountain area | Ertaizi (ETZ) | 0.564 | 0.662 | 2.286 |

| Haoqian (HQ) | 0.725 | 0.564 | 2.640 | |

| Zhanggao (ZG) | 0.931 | 0.475 | 3.351 | |

| Datongyao (DTY) | 1.189 | 0.361 | 4.000 | |

| Dianzi (DZ) | 0.721 | 0.584 | 2.833 |

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wan, J.; Li, R.; Wang, W.; Liu, Z.; Chen, B. Income Diversification: A Strategy for Rural Region Risk Management. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1064. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8101064

Wan J, Li R, Wang W, Liu Z, Chen B. Income Diversification: A Strategy for Rural Region Risk Management. Sustainability. 2016; 8(10):1064. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8101064

Chicago/Turabian StyleWan, Jinhong, Ruoxi Li, Wenxin Wang, Zhongmei Liu, and Bizhen Chen. 2016. "Income Diversification: A Strategy for Rural Region Risk Management" Sustainability 8, no. 10: 1064. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8101064

APA StyleWan, J., Li, R., Wang, W., Liu, Z., & Chen, B. (2016). Income Diversification: A Strategy for Rural Region Risk Management. Sustainability, 8(10), 1064. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8101064