Education for Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR): Linking Theory with Practice in Ghana’s Basic Schools

Abstract

:1. Introduction

| Techniques | Description |

|---|---|

| Interactive | Engages students in brainstorming and discussion on a given topic |

| Surrogate experiential | Uses proxies of real life events e.g., film making, role play |

| Field experiential | Undertaking practical activities outside the classroom e.g., hazard mapping |

| Affective | Students share their feelings and experiences of disaster events |

| Inquiry | Obtaining information from outside the classroom e.g., internet enquiries |

| Action | Active involvement of students in practical sessions |

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area Information

Basic School System in Ghana

| Community | Gender | Kpalgun | Yoggu | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name of School | Kpalgun Primary & JHS | Yoggu D/A Primary & JHS | |||||

| Lower Primary | Upper Primary | JHS | Lower Primary | Upper Primary | JHS | ||

| No. of students | Male | 81 | 95 | 89 | 80 | 44 | 86 |

| female | 41 | 66 | 47 | 51 | 32 | 38 | |

| Total | 122 | 161 | 136 | 131 | 76 | 124 | |

| No. of teachers | Male | 4 | 3 | 10 | 3 | 3 | 8 |

| Female | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | |

| Total | 4 | 3 | 10 | 3 | 3 | 9 | |

2.2. Data Collection and Field Work

2.2.1. Questionnaires

2.2.2. Focus Group Discussions and Key Informant Interviews

2.3. Data Analysis

2.3.1. Content Analysis Process

- (1)

- Core words within the DRR discourse, such as hazard, disaster, vulnerability, risk, and resilience, were obtained from literature and web-based resources from various institutions, such as United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction (UNISDR terminologies) [41] and Department of Community Safety, State of Queensland [42].

- (2)

- Five words found within the scope of the DRR, which are: cause, effects, prevention, recovery, and management of disasters which are found in UNISDR terminologies and other literature.

- (3)

- Common disaster events in Ghana, particularly in the study communities. Examples include floods, droughts, windstorm, and fires.

| No. | Upper Primary Subjects | Title of Syllabus | Year of Publication | Total No. of Pages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Citizenship Education | Teaching syllabus for Citizenship Education (Primary 4–6) | September, 2007 | 44 |

| 2 | Integrated Science | Teaching syllabus for Integrated Science (Primary 4–6) | September, 2012 | 35 |

| 3 | English Language | Teaching syllabus for English Language (Primary 4–6) | September, 2012 | 80 |

| 4 | Creative Arts | Teaching syllabus for Creative Arts (Primary 4–6) | September, 2007 | 93 |

| 5 | Information and Communications Technology | Teaching syllabus for Information and Communications Technology (Primary 1–6) | September, 2007 | 37 |

| 6 | Ghanaian Language and Culture | Teaching syllabus for Ghanaian Language and Culture (Primary 4–6) | September, 2012 | 93 |

| 7 | Religious and Moral Education | Teaching syllabus for Religious and Moral Education (Primary 1–6) | September, 2008 | 76 |

| 8 | Mathematics | Teaching syllabus for Mathematics (Primary 1–6) | September, 2012 | 160 |

| 9 | Physical Education | Teaching syllabus for Physical Education (Primary 1–6) | September, 2007 | 91 |

| No. | Junior High School Subjects | Title of Syllabus | Year of publication | Total No. of Pages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Integrated Science | Teaching syllabus for Integrated Science (JHS 1–3) | September, 2012 | 65 |

| 2 | Social Studies | Teaching syllabus for Social Studies (JHS 1–3) | September, 2007 | 51 |

| 3 | Music and Dance | Teaching syllabus for Music and Dance (JHS 1–3) | September, 2008 | 29 |

| 4 | Building Design and Technology | Teaching syllabus for Building Design and Technology (JHS 1–3) | September, 2007 | 132 |

| 5 | English Language | Teaching syllabus for English Language (JHS 1–3) | September, 2012 | 118 |

| 6 | Information and Communications Technology | Teaching syllabus for Information and Communications Technology (JHS 1–3) | September, 2007 | 50 |

| 7 | Religious and Moral Education | Teaching syllabus for Religious and Moral Education (JHS 1–3) | September, 2008 | 56 |

| 8 | Mathematics | Teaching syllabus for Mathematics (JHS 1–3) | September, 2012 | 84 |

| 9 | Physical Education | Teaching syllabus for Physical Education (JHS 1–3) | September, 2007 | 73 |

| 10 | French | Teaching syllabus for French (JHS 1–3) | September, 2007 | 88 |

| 11 | Ghanaian Language and Culture | Teaching syllabus for Ghanaian Language and Culture (JHS 1–3) | September, 2007 | 57 |

| Key Words | Synonyms | Key Words | Synonyms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard | Menace , threat | Recover(y) | Recuperate, get well |

| Disaster | Calamity, tragedy | Response | React, handle |

| Risk | Danger, exposure | Manage(ment) | Control, cope |

| Vulnerability | Prone to, predisposed to | Capacity | Ability, aptitude |

| Climate change | - | Flood | Inundation, overflow |

| Resilience | Overcome | Drought | Lack of water |

| Causes | Sources, reasons | Fire | - |

| Effects | Consequence, result of | Earthquake | Earth tremor, vibration in the earth |

| Prevent | Avoid, stop | Pests | Vermin, parasite |

| Protect | Safeguard, keep | Diseases | Ailment, infection |

| Safety | Secure, welfare | Epidemics | - |

| Adapt | Adjust, cope | Windstorm | Rainstorm, whirlwind |

2.3.2. Questionnaire and Interview Data Analysis

- (1)

- Scope and content of disaster themes and topics taught in the classroom

- (2)

- Teaching, learning, and evaluation activities employed in the classroom

- (3)

- Competencies developed and challenges faced through classroom DRR education

2.3.3. Strengths and Limitations of Research Approach

3. Results

3.1. Comparing and Contrasting Subject Syllabus Contents and Classroom Application of DRR

3.1.1. Presence of DRR in Upper Primary and JHS Subjects

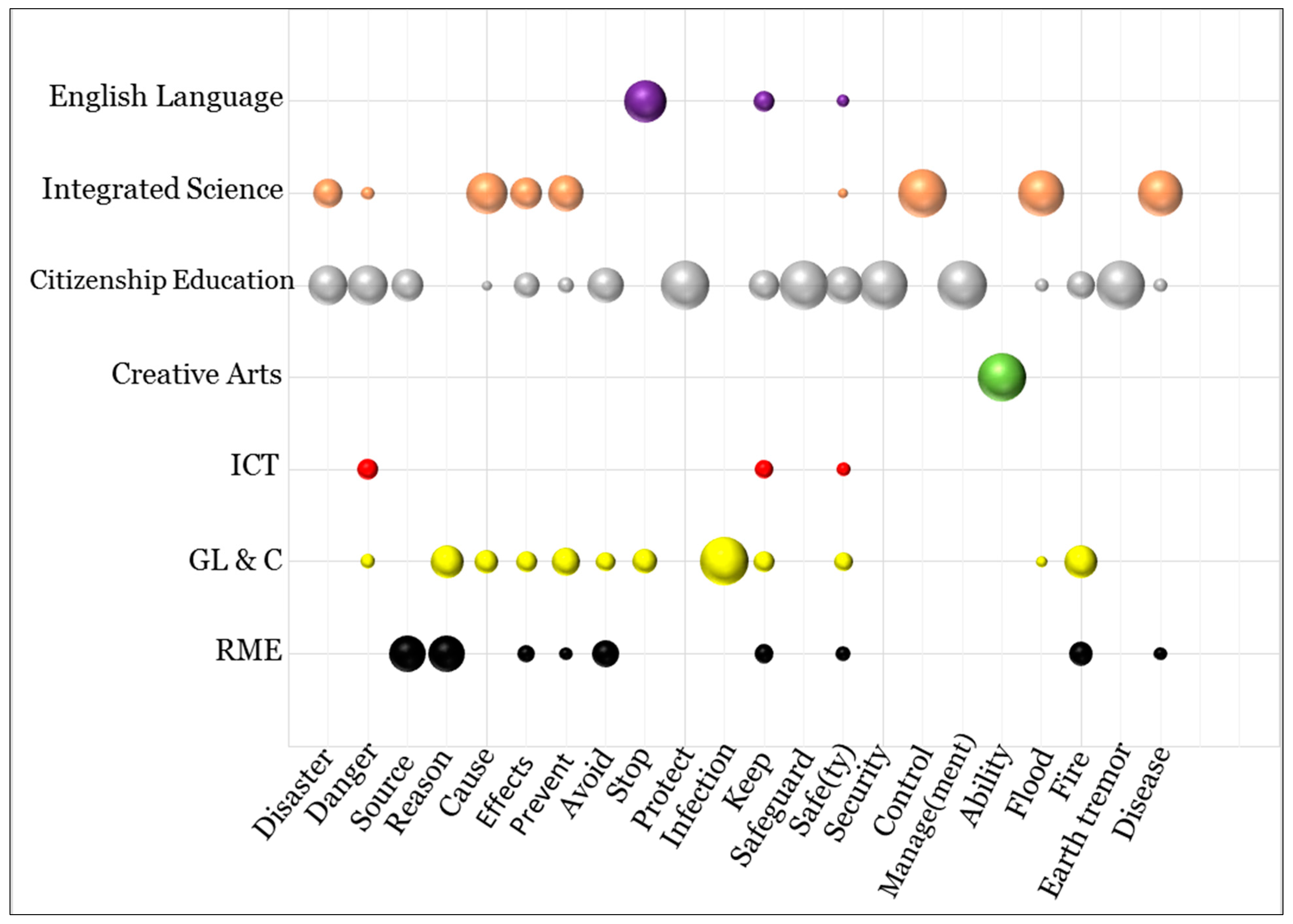

3.1.2. Scope and Content of DRR in Upper Primary and JHS Subjects

3.1.3. Teaching and Learning Activities for DRR

| Teaching and Learning Techniques | Frequency of Use of the Various Types of Teaching and Learning Techniques | |

|---|---|---|

| Upper Primary | Junior High School | |

| Interactive (e.g., Brainstorming) | 54 | 60 |

| Surrogate experiential | 5 | 6 |

| Action (experiments, demonstrations) | 5 | 8 |

| Field experiential (fieldtrips) | 11 | 5 |

| Lecture | 4 | 6 |

| Inquiry | 4 | 3 |

| Affective | 1 | 0 |

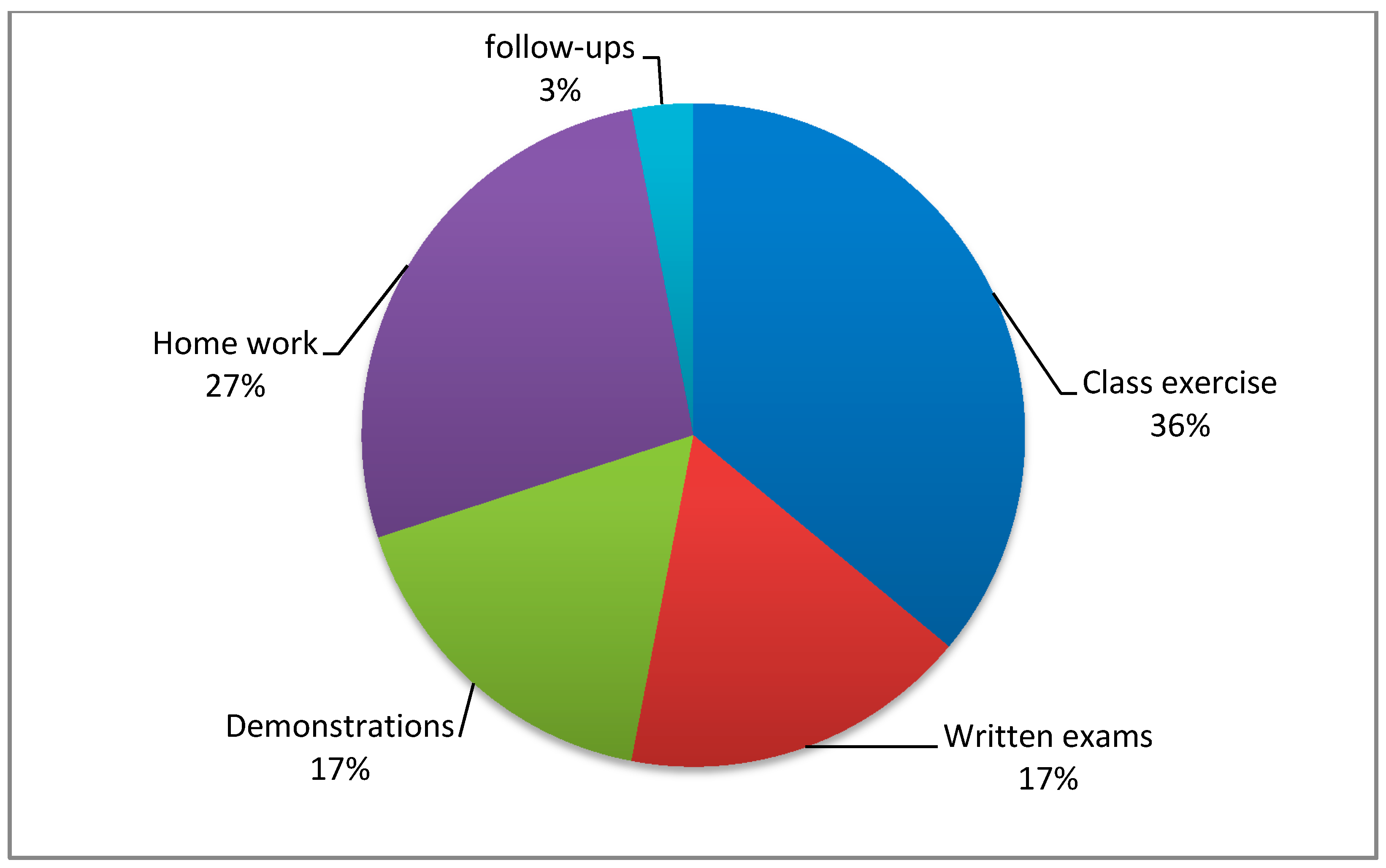

3.1.4. Evaluation Techniques for DRR Lessons

3.2. Skills and Competencies Developed from DRR Education

3.3. Challenges Identified

“When teaching, we have pictures of past disasters that we show to the students in order to help them better understand and perceive what is being taught, but there are no lights in most of the schools and thus our inability to make use of the internet and videos to teach students about disasters.”[44]

“We sometimes organize practical sessions when teaching, especially when the materials needed to carry out the experiments are available but if they are not, we have to teach them in an abstract way.”[45]

“The cost involved in undertaking practical sessions sometimes makes it difficult since some students cannot afford the materials needed for the work.”[46]

4. Discussion

4.1. Curriculum Development to Nurture Relevant Skills and Competencies

4.2. Teachers as Transmitters of Disaster Knowledge

4.3. Basic Infrastructure for Effective DRR Education

4.4. Evaluation for Effective DRR Lessons

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UNISDR. Disaster Risk Reduction begins at schools. In World Disaster Reduction Campaign; United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction (UNISDR): Geneva, Switzerland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Gaillard, J.C. Vulnerability, capacity and resilience: Perspectives for climate and development policy. J. Int. Dev. 2010, 22, 218–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelman, I. Understanding Vulnerability to Understand Disasters; Canadian Risk and Hazards Network: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks, N.; Neil Adger, W.; Mick Kelly, P. The determinants of vulnerability and adaptive capacity at the national level and the implications for adaptation. Glob. Environ. Change 2005, 15, 151–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Save the Children UK. Legacy of Disasters: The Impact of Climate Change on Children; Save the Children: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Tarazona, M.; Gallegos, J. Recent Trends in Disaster Impacts on Child, Welfare and Development 1999–2009; The United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Enarson, E.P. Gender and Natural Disasters; Recovery and Reconstruction Department: Geneva, Switzerland, 2000; Available online: http://www.ilo.int/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_emp/---emp_ent/---ifp_crisis/documents/publication/wcms_116391.pdf (accessed on 3 March 2014).

- Mitchell, T.; Haynes, K.; Hall, N.; Choong, W.; Oven, K. The roles of children and youth in communicating disaster risk. Child. Youth Environ. 2008, 18, 254–279. [Google Scholar]

- Izadkhah, Y.O.; Hosseini, M. Towards resilient communities in developing countries through education of children for disaster preparedness. Int. J. Emerg. Manag. 2005, 2, 138–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ESCAP/UNISDR. Reducing Vulnerability and Exposure to Disasters: The Asia-Pacific. Available online: http://www.unisdr.org/we/inform/publications/29288 (accessed on 12 January 2015).

- Baez, J.; de la Fuente, A.; Santos, I. Do Natural Disasters Affect Human Capital? An Assessment Based on Existing Empirical Evidence; IZA DP No. 5164; Institute for the Study of Labor: Bonn, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett, S. Climate change and urban children: Impacts and implications for adaptation in low-and middle-income countries. Environ. Urban. 2008, 20, 501–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, K.N.; Edwards, M.T. Disaster risk reduction and vulnerable populations in Jamaica: Protecting children within the comprehensive disaster management framework. Child. Youth Environ. 2008, 18, 389–407. [Google Scholar]

- Seballos, F.; Tanner, T.; Tarazona, M.; Gallegos, J. Children and Disasters: Understanding Impact and Enabling Agency; Institute of Development Studies: Brighton, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Petal, M.; Izadkhah, Y.O. Concept note: Formal and informal education for disaster risk reduction. In Proceedings of the International Conference on School Safety, Islamabad, Pakistan, 14–16 May 2008.

- Benadusi, M. Pedagogies of the unknown: Unpacking “Culture” in disaster risk reduction education. J. Conting. Crisis Manag. 2014, 22, 174–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Childs, D.; Gordy, M.; Gordon, M. Implementation of the Hyogo Framework for Action, Summary of Reports 2007–2013; United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction (UNISDR): Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Djalante, R.; Thomalla, F.; Sinapoy, S.M.; Carnegie, M. Building resilience to natural hazards in Indonesia: Progress and challenges in implementing the Hyogo Framework for Action. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2012, 62, 779–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wisner, B. Let Our Children Teach Us: A Review of the Role of Education and Knowledge in Disaster Risk Reduction. Available online: http://www.unisdr.org/2005/task-force/working%20groups/knowledge-education/docs/Let-our-Children-Teach-Us.pdf (accessed on 2 July 2015).

- Stanganelli, M. A new pattern of risk management: The Hyogo framework for action and Italian practice. Socioecon. Plan. Sci. 2008, 42, 92–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Disaster Management Organization. Ghana’s Disaster Profile. 2012. Available online: http://www.nadmo.gov.gh/index.php/ghana-s-disaster-profile (accessed on 23 December 2014). [Google Scholar]

- Quansah, H.N.B. Ghana Loses ¢2.43 m to Fire in January–February, 2014. Available online: http://graphic.com.gh/business/business-news/21457-ghana-loses-2-43m-to-fire-in-january-february-2014.html (accessed on 12 August 2014).

- Selby, D.; Kagawa, F. Disaster Risk Reduction in School Curricula: Case Studies from Thirty Countries; United Nations Children Fund: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, R.; Shiwaku, K.; Takeuchi, Y. Disaster Education; Emerald Group Publishing Ltd.: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Darling-Hammond, L. Teacher learning that supports student learning. Strength. Teach. Prof. 1998, 55, 6–11. [Google Scholar]

- Oteng-Ababio, M. “Prevention is better than cure”: Assessing Ghana’s preparedness (capacity) for disaster management. Jamba J. Disaster Risk Stud. 2013, 5, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghana Statistical Survey-GLSS 6 2014. Poverty Profile in Ghana 2005–2013. Available online: http://www.statsghana.gov.gh/docfiles/glss6/GLSS6_Poverty%20Profile%20in%20Ghana.pdf (assessed on 13 January 2015).

- Songsore, J. Regional Development in Ghana: The Theory and Reality; Woeli Publishing Services: Accra, Ghana, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Avtar, R.; Saito, O.; Singh, G.; Kobayashi, H.; Ali, Y.; Herath, S.; Takeuchi, K. Monitoring responses of terrestrial ecosystem to climate variations using multi temporal remote sensing data in Ghana. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium (IGARSS), Quebec City, QC, Canada, 13–18 July 2014.

- Boafo, Y.A.; Saito, O.; Takeuchi, K. Provisioning ecosystem services in rural savanna landscapes of Northern Ghana: An assessment of supply, utilization, and drivers of change. J. Disaster Res. 2014, 9, 501–515. [Google Scholar]

- Boakye-Danquah, J.; Antwi, E.K.; Osamu, S.; Abekoe, M.K. Impact of farm management practices and agricultural land use on soil organic carbon storage potential in the savannah ecological zone of Northern Ghana. J. Disaster Res. 2014, 9, 484–500. [Google Scholar]

- Ghana Districts 2006. Northern-tolon. Available online: http://www.ghanadistricts.com/districts/?r=6&_=88&sa=6610 (accessed on 12 January 2015).

- Antwi, E.K.; Otsuki, K.; Osamu, S.; Obeng, F.K.; Gyekye, K.A.; Boakye-Danquah, J.; Boafo, Y.A.; Kusakari, Y.; Yiran, G.A.B.; Owusu, A.B.; et al. Developing a community-based resilience assessment model with reference to Northern Ghana. IDRiM J. 2014, 4, 73–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghana Statistical Service. 2010 Population and Housing Census Summary Report of Final Results. Available online: http://www.statsghana.gov.gh/docfiles/2010phc/Census2010_Summary_report_of_final_results.pdf (assessed on 2 February 2015).

- Grotberg, E.H. A Guide to Promoting Resilience in Children: Strengthening the Human Spirit; Bernard Van Leer Foundation: The Hague, The Netherlands, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- UNISDR. Global Assessment Report on Disaster Risk Reduction. 2015. Available online: http://www.preventionweb.net/english/hyogo/gar/2015/en/gar-pdf/GAR2015_EN.pdf (accessed on 19 March 2015).

- Mamogale, H.M. Assessing Disaster Preparedness of Learners and Educators in Soshanguve North. Master’s Thesis, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, Free State, South Africa, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- The United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Children Charter: An Action Plan for Disaster Risk for Children by Children. 2011. Available online: http://www.unicef.org/mozambique/children_charter-May2011.pdf (access on 21 January 2014).

- Israel, G.D. Determining Sample Size; Institute of Food and Agriculture Sciences, University of Florida Cooperative Extension Service: Gainesville, FL, USA, 2009; Available online: http://www.soc.uoc.gr/socmedia/papageo/metaptyxiakoi/sample_size/samplesize1.pdf (accessed on 23 July 2014).

- Downe, W.B. Content analysis: Method, applications, and issues. Health Care Women Int. 1992, 13, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction (UNISDR). Terminology. Available online: http://www.unisdr.org/we/inform/terminology (accessed on 22 February 2014).

- State of Queensland, Department of Community Safety 2010–2013. Disaster Management. Available online: http://www.disaster.qld.gov.au/About_Disaster_Management/Management_Phases.html (accessed on 28 November 2014).

- Alhassan, I.; Yoggu D/A Junior High School, Tolon District, Ghana. Personal communication, 2014.

- Karim, M.; Kpalgun Zion Junior High School, Tolon District, Ghana. Personal communication, 2014.

- Sulemana, A.; Kpalgun Zion Primary School, Tolon District, Ghana. Personal communication, 2014.

- Abukari, S.; Yoggu D/A Junior High School, Tolon District, Ghana. Personal communication, 2014.

- Houghton, J.T. (Ed.) Climate Change 1995: The Science of Climate Change: Contribution of Working Group I to the Second Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1996.

- Parry, M.L. (Ed.) Climate Change 2007: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability: Contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007; Volume 4.

- Meehl, G.A.; Stocker, T.F.; Collins, W.D.; Friedlingstein, P.; Gaye, A.T.; Gregory, J.M.; Kitoh, A.; Knutti, R.; Murphy, J.M.; Noda, A.; et al. Global climate projections. In Climate Change 2007: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC). The Role of Education for Natural Disaster. Available online: http://www.criced.tsukuba.ac.jp/math/apec/ICME12/Lesson_Study_set/The_Role_of_Education_for_Natural_Disasters.pdf (accessed on 13 January 2015).

- Sensarma, S.R.; Sarkar, A. (Eds.) Disaster Risk Management: Conflict and Cooperation; Concept Publishing Company: New Delhi, India, 2013.

- Ministry of Education. Acts on Education. 2015. Available online: http://www.moe.gov.gh/?moe=Documents§=Acts%20On%20Education (accessed on 13 January 2015). [Google Scholar]

- Shida, M. Education for disaster prevention in elementary school in Japan. In Proceedings of the EGU General Assembly Conference, Vienna, Austria, 7–12 April 2013.

- International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies. Public Awareness and Public Education for Disaster Risk Reduction: Key Messages. 2012. Available online: http://www.preventionweb.net/files/31061_31061ifrckeymessages2012121.pdf (accessed on 11 May 2015).

- Angelo, T.A.; Cross, K.P. Classroom Assessment Techniques. 1993. Available online: http://sloat.essex.edu/sloat/delete/contentforthewebsite/classroom_assessment_techniques.pdf (accessed on 2 January 2015).

© 2015 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Apronti, P.T.; Osamu, S.; Otsuki, K.; Kranjac-Berisavljevic, G. Education for Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR): Linking Theory with Practice in Ghana’s Basic Schools. Sustainability 2015, 7, 9160-9186. https://doi.org/10.3390/su7079160

Apronti PT, Osamu S, Otsuki K, Kranjac-Berisavljevic G. Education for Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR): Linking Theory with Practice in Ghana’s Basic Schools. Sustainability. 2015; 7(7):9160-9186. https://doi.org/10.3390/su7079160

Chicago/Turabian StyleApronti, Priscilla T., Saito Osamu, Kei Otsuki, and Gordana Kranjac-Berisavljevic. 2015. "Education for Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR): Linking Theory with Practice in Ghana’s Basic Schools" Sustainability 7, no. 7: 9160-9186. https://doi.org/10.3390/su7079160

APA StyleApronti, P. T., Osamu, S., Otsuki, K., & Kranjac-Berisavljevic, G. (2015). Education for Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR): Linking Theory with Practice in Ghana’s Basic Schools. Sustainability, 7(7), 9160-9186. https://doi.org/10.3390/su7079160