Inter-Korean Forest Cooperation 1998–2012: A Policy Arrangement Approach

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Policy Arrangement Approach: Research Design and Method

| Type of Documents | Title of Documents |

|---|---|

| Books | Unification White Papers (1998–2012) |

| Declarations & Agreements | June 15 Joint Declaration (2000) |

| The 15th Inter-Korean Ministerial Talks (2005) | |

| First round of Inter-Korean Agricultural Cooperation Committee (2005) | |

| Declaration on the Advancement of South-North Korean Relations, Peace and Prosperity (2007) | |

| First South-North Prime Ministerial Talks (2007) | |

| Acts | Inter-Korean Exchange & Cooperation Act (1990) |

| Inter-Korean Cooperation Fund Act (1990) | |

| Ordinances | Ordinance on South-North Gangwon Province’s Exchange and Cooperation Committee (1989) |

| Ordinance on South-North Gangwon Province’s Cooperation Fund (1989) | |

| Ordinance on South-North Gyeonggi Province’s Exchange and Cooperation (2001) | |

| Ordinance on Gyeonggi Province’s Exchange and Cooperation Committee (2002) | |

| Ordinance on South-North Gyeonggi Province’s Cooperation Fund |

3. Results

3.1. Discourse

| South Korean Administration | Policy Focus toward North Korea | Forest Project Activities |

|---|---|---|

| Kim Dae Jung (1998–2002) | Reconciliation and cooperation | Creation |

| Roh Moo Hyun (2003–2007) | Peace and Prosperity | Vitalization |

| Lee Myoung Bak (2008–2012) | Denuclearization and Openness | Stagnation |

| Title | Signed Date | Contents | South Korean Administration |

|---|---|---|---|

| June 15 Joint Declaration | 15 June 2000 | Cooperation and exchanges in the environmental field | Kim Dae Jung (1998–2002) |

| The 15th Inter-Korean Ministerial Talks | 23 June 2005 | Inter-Korean agricultural cooperation | Roh Moo Hyun (2003–2007) |

| First round of Inter-Korean Agricultural Cooperation Committee | 19 August 2005 | Forestry projects: protection of lands and ecosystems through the construction of tree nurseries and control of diseases and insect pests | Roh Moo Hyun (2003–2007) |

| Declaration on the Advancement of South-North Korean Relations, Peace and Prosperity | 4 October 2007 | Cooperation projects in the sector of agriculture and environmental protection | Roh Moo Hyun (2003–2007) |

| First South-North Prime Ministerial Talks for implementing Declaration on the Advancement of South-North Korean Relations, Peace and Prosperity | 16 November 2007 | Cooperation projects on reforestation and prevention of diseases and insect pests | Roh Moo Hyun (2003–2007) |

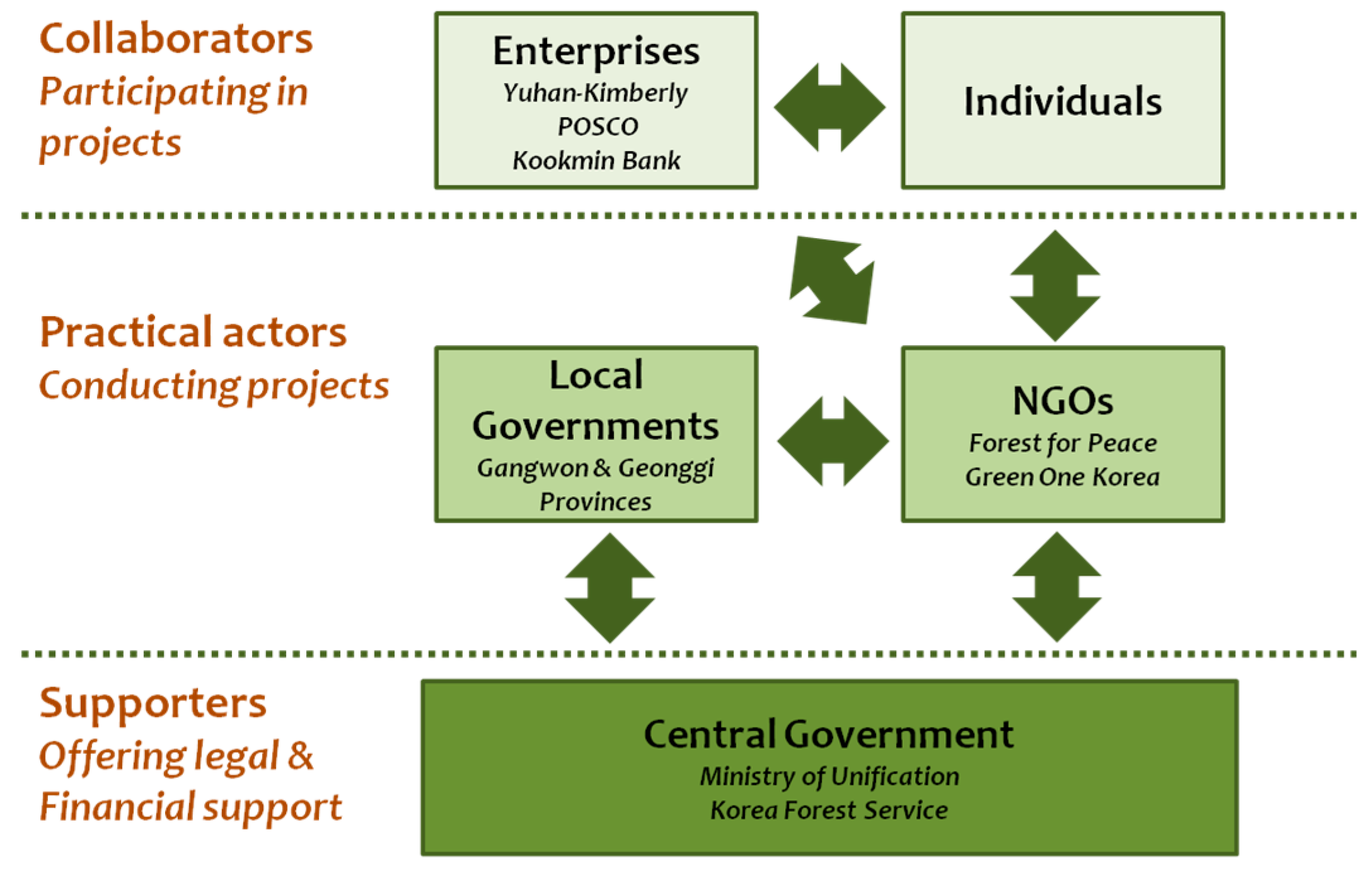

3.2. Actors

3.3. Rules

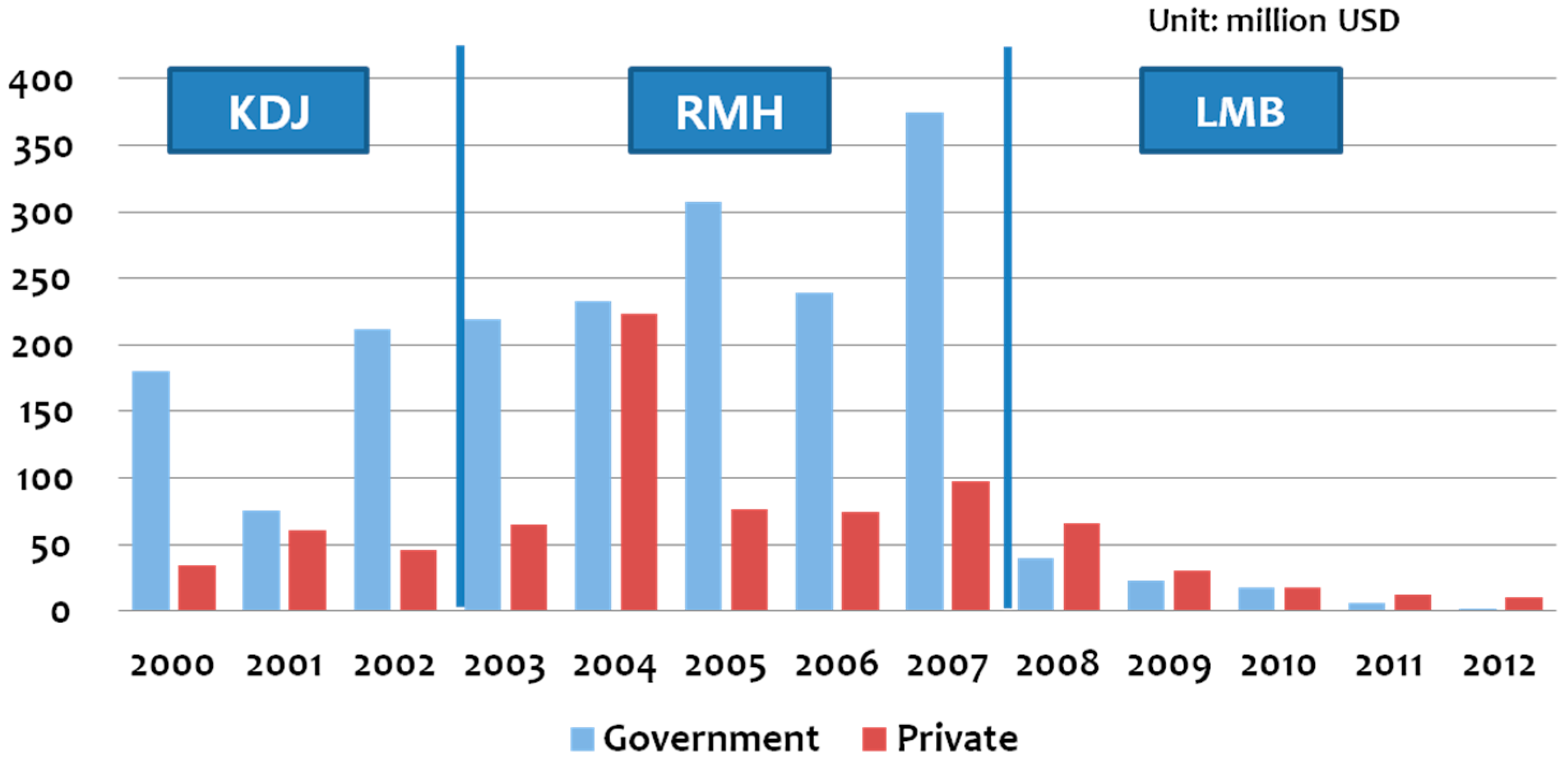

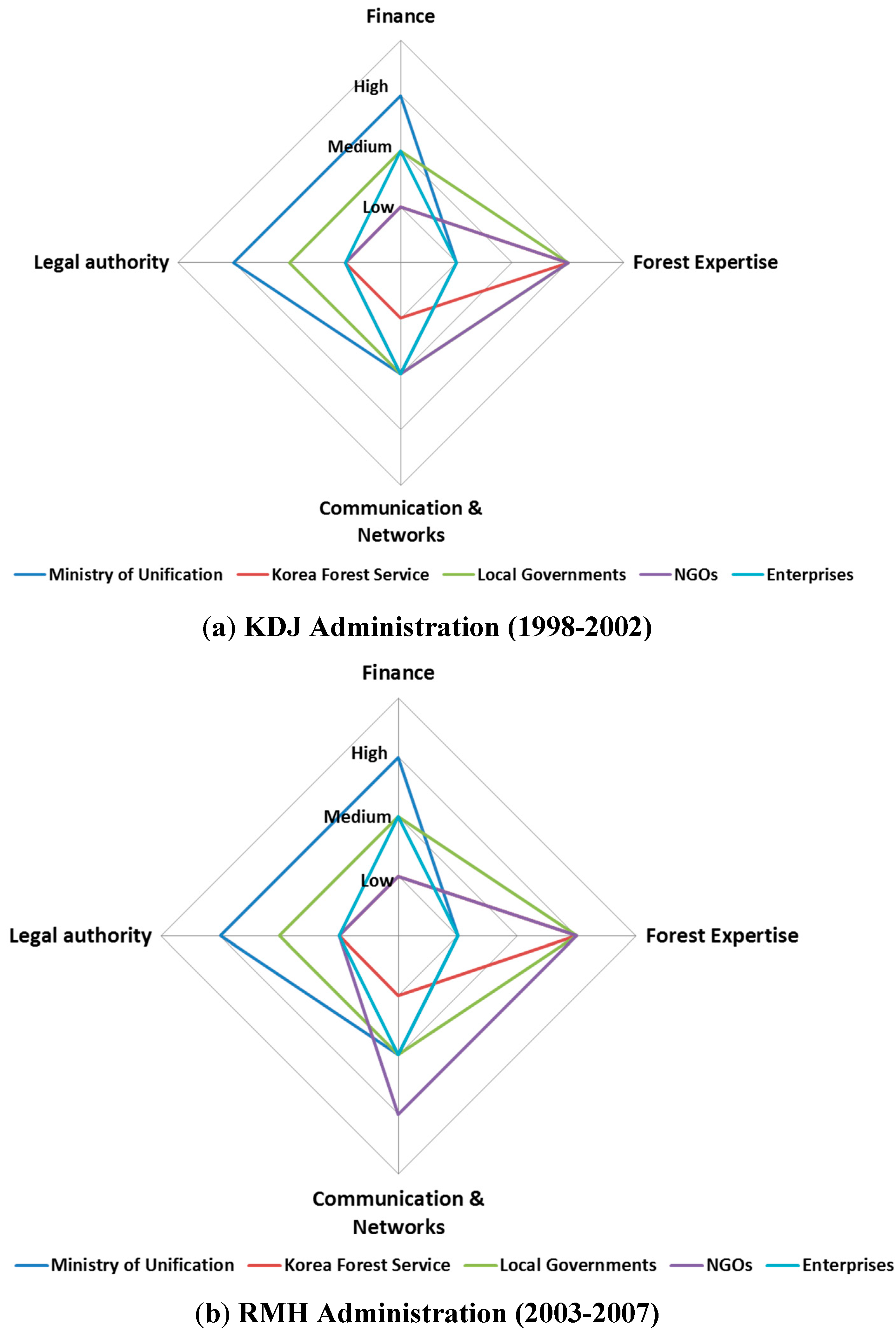

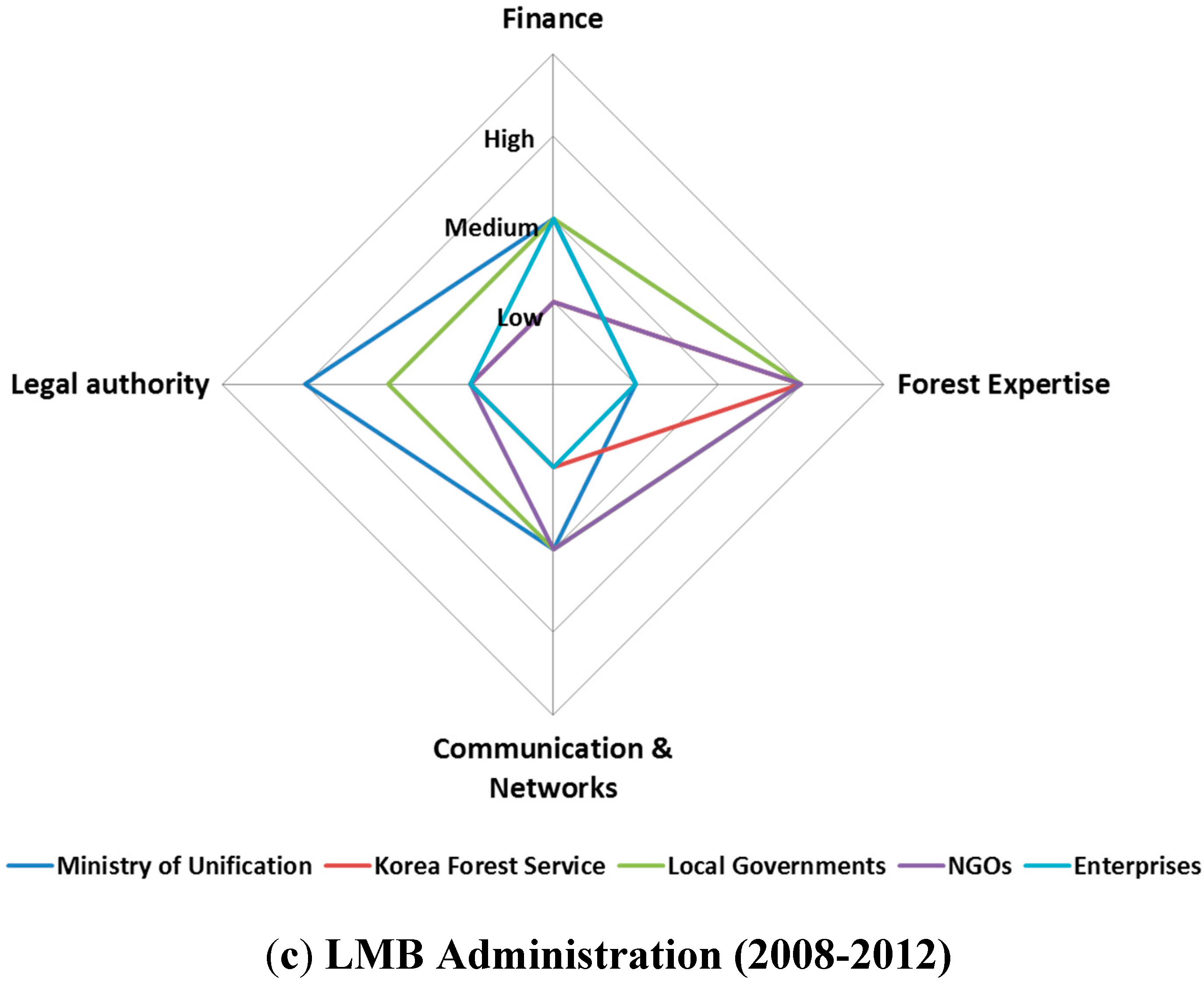

3.4. Power

| The Financed Private Organizations | Year | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | ||

| Administration | |||||||

| RMH | LMB | ||||||

| Forest for Peace | 46 | 75 | 87 | 160 | 22 | - | 390 |

| Korean Council for Reconciliation and Cooperation | - | - | - | - | 1399 | - | 1399 |

| Green One Korea | - | - | 338 | 338 | |||

| Total | 46 | 75 | 87 | 160 | 1421 | 338 | 2127 |

4. Discussion and Conclusions

| Dimensions of power | Attributes | Levels | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | Medium | High | ||

| Finance | Financial dependency Financial scale | Dependent | Independent and small scale | Independent and large scale |

| Forest expertise | Positions of forest experts within organizations | No forest experts | Part-time positions | Full-time positions |

| Communication and networks | Communication activities Coalitions | No publications and no conferences | Publications and conferences | Publications and conferences Coalitions |

| Legal authority | Legislations Administration procedures | No legislations | Establishing and implementing legislations | Establishing and implementing legislations Controlling projects |

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ministry of Unification. Unification White Paper; Ministry of Unification: Seoul, Korea, 1996. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Bae, J.S.; Joo, R.W.; Kim, Y.-S. Forest transition in South Korea: Reality, path and drivers. Land Use Policy 2012, 29, 198–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noronha, R. Why is it so difficult to grow fuelwood. Unasylva 1981, 33, 4–12. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, L.R. Plan B 3.0: Mobilizing to Save Civilization; W.W. Norton: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Park, M.; Lee, Y. Forest policy and law for sustainability within the Korean Peninsula. Sustainability 2014, 6, 5162–5186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, J.H.; Koo, J.C.; Youn, Y.C. Economic feasibility of REDD project for preventing deforestation in North Korea. J. For. Soc. 2011, 100, 630–638. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Maplecroft. Climate Change and Environmental Risk Atlas 2012; Maplecroft: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.; Lee, D. Deforestation in North Korea will Cause Desertification of Korean Peninsula; Story Yoon: Seoul, Korea, 2014. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Myung, S.; Kim, J.; Lim, M.; Whang, S.; Son, K.; Ahn, J.; Kim, M.; Kang, S.; Joo, K.; Sung, S.; et al. A Study on Constructing a Cooperative System for South and North Koreas to Counteract Climate Change on the Korean Peninsula III; Korean Environmental Institute: Seoul, Korea, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ilbo, D.-A. Reforestation of North Korea is precedent for Green Reunification. Available online: http://english.donga.com/srv/service.php3?biid=2014031930648 (accessed on 8 April 2015).

- Park, J. Northeast Asian Forest Cooperation in Global Society. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Governance for Reforestation in Korean Peninsula, Seoul, Korea, 13 November 2014; pp. 42–53. (In Korean)

- Park, M.; Youn, Y. The Korean governance: An Inter-Korean Forestry Cooperation. Available online: http://www.iufro.org/download/file/6115/4110/iwc10-abstracts_pdf (accessed on 27 April 2015).

- Lee, J. Reforestation projects in North Korea by Forest for Peace. In Proceedings of Symposium on Inter-Korean Cooperation for Reforestation in North Korea, Seoul, Korea, 9 February 2010. (In Korean)

- Cho, C. Greening North Korea through inter-Korean Exchange and Cooperation. In Proceedings of Symposium on Inter-Korean Cooperation for Reforestation in North Korea, Seoul, Korea, 9 February 2010. (In Korean)

- Ahn, S. Outcomes and Plans of inter-Korea Forest Cooperation Projects by Green One Korea. In Proceedings of Symposium on Inter-Korean Cooperation for Reforestation in North Korea, Seoul, Korea, 9 February 2010. (In Korean)

- Krott, M. Forest Policy Analysis; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Cubbage, F.; Harou, P.; Sills, E. Policy instruments to enhance multi-functional forest management. For. Policy Econ. 2007, 9, 833–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Gossum, P.; Arts, B.; Verheyen, K. “Smart regulation”: Can policy instrument design solve forest policy aims of expansion and sustainability in Flanders and The Netherlands? For. Policy Econ. 2012, 16, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lertzman, K.; Rayner, J.; Wilson, J. Learning and change in the British Columbia forest policy sector: A consideration of Sabatier’s advocacy coalition framework. Can. J. Polit. Sci. 1996, 29, 111–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, C.; Schlaepfer, R. The advocacy coalition framework: Application to the policy process for the development of forest certification in Sweden. J. Eur. Public Policy 2001, 8, 642–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cashore, B.; Vertinsky, I. Policy networks and firm behaviours: Governance systems and firm reponses to external demands for sustainable forest management. Policy Sci. 2000, 33, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krott, M.; Hasanagas, N.D. Measuring bridges between sectors: Causative evaluation of cross-sectorality. For. Policy Econ. 2006, 8, 555–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veenman, S.; Liefferink, D.; Arts, B. A short history of Dutch forest policy: The “de-institutionalisation” of a policy arrangement. For. Policy Econ. 2009, 11, 202–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Gossum, P.; Arts, B.; Wulf, R.; de Verheyen, K. An institutional evaluation of sustainable forest management in Flanders. Land Use Policy 2011, 28, 110–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.; Youn, Y. Development of urban forest policy-making toward governance in the Republic of Korea. Urban For. Urban Green 2013, 12, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liefferink, D. The Dynamics of Policy Arrangements: Turning Round the Tetrahedron. In Insititutional Dynamics in Environmental Governance; Arts, B., Leroy, P., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2006; pp. 45–68. [Google Scholar]

- Van Tatenhove, J.P.M.; Arts, B.; Leroy, P. Political Modernization and the Environment: The Renewal of Environmental Policy Arrangements; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dorerecht, The Netherlands, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Arts, B.; Leroy, P. Insititutional Dynamics in Environmental Governance; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Dryzek, J.S. The Politics of the Earth: Environmental Discourses; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Hajer, M.A. The Politics of Environmental Discourse: Ecological Modernization and the Policy Process; Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Unification. Peace and Cooperation: White Paper on Korean Unification 2001; Ministry of Unification: Seoul, Korea, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Unification. Unification White Paper; Ministry of Unification: Seoul, Korea, 2006. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Unification. Unification White Paper; Ministry of Unification: Seoul, Korea, 2008. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Unification. White Paper on Korean Unification 2010; Ministry of Unification: Seoul, Korea, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, J. Sunshine over a barren soil: The domestic politics of engagement identity formation in South Korea. Asian Perspect. 2010, 34, 115–138. [Google Scholar]

- Moon, C.I. The Sunshine Policy and the Korean Summit: Assessments and Prospects. In The Future of North Korea; Akaha, T., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2013; pp. 26–46. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Unification. Unification White Paper; Ministry of Unification: Seoul, Korea, 2005. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Unification. Available online: http://eng.unikorea.go.kr/content.do?cmsid=1826 (accessed on 22 January 2015).

- Ganwon Province. Available online: http://uni.provin.gangwon.kr/cb/fd00.html (accessed on 22 January 2015). (In Korean)

- Ganwon Province. A Giant Step toward the Bright Future: The Ten Year Course of Exchange and Cooperation between Southern and Northern Gangwon Province; Gangwon Province: Chunchen, Korea, 2010. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Forest for Peace. Available online: http://www.peaceforest.or.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=002_bbs2 (accessed on 22 January 2015). (In Korean)

- Green One Korea. Available online: http://www.greenonekorea.or.kr (accessed on 22 January 2015). (In Korean)

- Chung, J.Y.; Youn, Y.C.; Cho, D.S. Evolutionary governance choice for corporate social responsibility: A forestry campaign case in South Korea. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2012, 19, 339–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, H. Euhan Kimberly: Greening and greening in the region of Mount Kumgang, Hankoolilbo. Available online: http://news.naver.com/main/read.nhn?mode=LSD&mid=sec&sid1=101&oid=038&aid=0001944819 (accessed on 27 April 2015). (In Korean)

- Lee, S. A new paradigm for trust-building on the Korean Peninsula: Turning Korea’s DMZ into a UNESCO World Heritage site. Asia Pac. J. 2010, 35, 2–10. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Enhanced local law and regulations information system, Korean Ministry of Security and Public Administration. Available online: http://www.elis.go.kr (accessed on 22 January 2015). (In Korean)

- Ministry of Unification. Major statistics in Inter-Korean relations. Available online: http://eng.unikorea.go.kr/content.do?cmsid=1822 (accessed on 29 January 2015). (In Korean)

- Ministry of Unification. White Paper on Inter-Korean Cooperation Fund; Ministry of Unification: Seoul, Korea, 2008. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Jang, M. Urging aid to North Korea in the sector of agriculture, forestry and animal husbandry by civil associations and scientists. Voice of the People. 10 December 2009. Available online: http://www.vop.co.kr/A00000275042.html (accessed on 8 April 2015). (In Korean)

- Geist, H.J.; Lambin, E.F. Proximate causes and underlying driving forces of tropical deforestation: Tropical forests are disappearing as the result of many pressures, both local and regional, acting in various combinations in different geographical locations. BioScience 2002, 52, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2015 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Park, M.S. Inter-Korean Forest Cooperation 1998–2012: A Policy Arrangement Approach. Sustainability 2015, 7, 5241-5259. https://doi.org/10.3390/su7055241

Park MS. Inter-Korean Forest Cooperation 1998–2012: A Policy Arrangement Approach. Sustainability. 2015; 7(5):5241-5259. https://doi.org/10.3390/su7055241

Chicago/Turabian StylePark, Mi Sun. 2015. "Inter-Korean Forest Cooperation 1998–2012: A Policy Arrangement Approach" Sustainability 7, no. 5: 5241-5259. https://doi.org/10.3390/su7055241

APA StylePark, M. S. (2015). Inter-Korean Forest Cooperation 1998–2012: A Policy Arrangement Approach. Sustainability, 7(5), 5241-5259. https://doi.org/10.3390/su7055241