1. Introduction

Competitiveness often depends on the successful development of innovations and their introduction to the market. This applies to companies, business sectors and certain regions, as well. In addition, due to sustainability issues raised by regional developments, innovations are becoming more important [

1,

2]. This can be described as innovation-based regional development and applies to both industrialized countries and emerging states [

3,

4,

5]. Currently, innovation is a key issue in regional development programs, such as the European RIS (Regional Innovation Strategies)/RITTS (Regional Innovation and Technology Transfer Strategies and Infrastructure) and LEADER (Liaison Entre Actions de Développement de l’Économie Rurale) and the German federal program, INNOregio (Unternehmen Regionen) [

6,

7,

8,

9]. Since the launch of RIS and RITTS in the early 1990s, the idea of innovation as a regional necessity and motor for sustainable development has been recognized. In numerous European regions, the European Commission aimed for the regions to develop their own innovation strategies and improve their innovation support infrastructure under the terms of “appropriate innovations”. Thus, the link to recent programs, initiatives and projects on regional innovations was provided, which also incorporated a strategic and analytic approach and the inclusion of a broad range of stakeholders. Generally, safeguarding the development and introduction of inventions on the market (innovating as an implementation process) requires systematic approaches, such as project planning, participatory rural appraisal or regional foresight. Nowadays, foresight has become an established instrument of regional policy [

10] and RIS [

11]. Foresight is defined as “a systematic, participatory, future intelligence gathering and medium-to-long-term vision building process aimed at present-day decisions and mobilizing joint actions” [

12] (p. 3). To this end, many foresight projects use a kind of “knowledge triangle”, meaning the cooperation of the representatives of the research, education and innovation spheres [

13]. In the EU, regional foresight is used frequently for regional development, e.g., for exploring capacities and identifying needs (U.K., North West region) [

14], identifying societal needs and patterns of the evolution of emerging technologies (Italy, Lombardy) [

15], analyzing social change and its impacts (Germany, Rhineland Palatinate) [

16], stimulating regional innovation and strengthening the regional economic system against global competition (Italy, Trento) [

17]. Lately, the European Commission has made efforts for a more comprehensive use of foresight approaches within the EU. Under the Research Framework 7 program, the European Foresight Platform (EFP) aims at supporting future decision making [

18].

From a foresight point of view, technology roadmapping (TRM) can be seen as a means to transact regional innovation or foresight projects, as depicted by Kindras

et al. [

10] in their example of the Samara region (Russia). TRM derives from a business- and technology-driven perspective, being a tool that supports the planning and coordination of development processes and the introduction of innovations to the market [

19,

20,

21,

22]. TRM is a flexible technique that can be used for a wide range of situations. It provides a structured and often graphical means for exploring and communicating the relationship between evolving and developing markets, products and technologies over time [

23,

24,

25]. In a broader sense, TRM covers the whole range of roadmapping that addresses technology, products, processes, market drivers, technical skills, projects,

etc. [

23]. Even though it is frequently used by a broad spectrum of firms and business sectors, the research in this field is relatively sparse [

26]. Furthermore, it has not been widely applied to geographical issues and regional sustainability. Only a few studies have dealt with the elements of TRM in urban or regional contexts. Van den Bosch

et al. [

27] applied a bottom-up approach to generate a roadmap for the Rotterdam case study of the transition to a fuel cell transport system. Another study by Lee

et al. [

28] introduced an integrated service-devices-technology roadmapping process for smart city development in Korea. In the Samara case study, scenarios were integrated into a roadmap to identify innovation potentials for strategic decisions [

10]. The adoption of TRM for open regional development strategies with a strong consideration of the region’s potentials does not yet exist. This gap has not been identified in the TRM literature nor TRM review papers (

cf. [

29]). In addition, Caetano and Amaral [

30] found that there are only a few proposals for partner selection and participation methods in roadmapping.

The openness of innovation processes for external expertise, which includes the broad participation of stakeholders, is part of the open innovation (OI) approach. Opening up innovation processes purposely for additional knowledge and ideas from outside has become an important strategy for leading industries to cope with changing environmental conditions and to compete effectively in the market [

31,

32]. The OI approach can be defined as “…the use of purposive inflows and outflows of knowledge to accelerate internal innovation, and expand the markets for external use of innovation” [

33]. It includes not only the opening of external knowledge at the initial stages of the innovation process, but also the continual participation of internal and external stakeholders at all stages. OI is closely connected with establishing and using organizational networks and benefits from cooperation with customers, suppliers, research institutes and teaching institutions to enhance the innovation capability of an organization [

32].

In addition to the main focus of OI on a single firm level, some studies have focused on OI in a regional setting. Schaffers

et al. [

34] explored business models to launch living labs for rural and regional development. Due to the close cooperation of users and technology providers, the living lab concept is strongly linked to the OI approach. In EURIS (European Collaborative and Regional Open Innovation Strategies) [

35], a recent European project, OI strategies are used to open regional innovation systems and to enhance the innovation ecosystems of various European regions. Belussi

et al. [

36] investigated the existence of an Open Regional Innovation System in Emilia Romagna (Italy) to show how firms adopt the OI strategy in order to overcome firm and regional boundaries.

One proposal to merge TRM and OI has been recently elaborated by Caetano and Amaral [

30]. The authors adapt roadmapping to open innovation environments by building a method that is applicable for organizations (primarily SMEs) that pursue technology to push innovation strategies. However, this paper assumed that the integration of the open innovation strategy and the TRM approach could be powerful for seeking sustainable open regional development. From the benefits of integrating the two approaches, the INNOrural project created the methodological framework, Regional Open Innovation Roadmapping (ROIR). ROIR is designed to utilize the innovation potentials of a region for its sustainable development and to maximize the prospect of innovation success.

This paper demonstrates how TRM and elements of OI were combined to form the approach ROIR. It examines the hypothesis that ROIR is able to provide a suitable framework for safeguarding innovation-based regional development projects. The application of ROIR and the development of its processes are illustrated by two case studies in the German region of Märkisch-Oderland (MOL), which tested the approach in practice and examined its advantages and difficulties. Both roadmapping processes concern non-technical or so-called social innovations in order to promote regional sustainability, in which the first addresses the development and certification of a supply chain for wood fuel and the second addresses the implementation of a competence center for precision farming technology (PF) for the state of Brandenburg in the same region. Both innovation examples are often seen as promoters for the sustainable use of natural resources, such as wood fuel, e.g., saving non-renewable energy sources and reducing greenhouse gas emissions [

37,

38], and PF, e.g., reducing the application amount of chemical fertilizer by adapting fertilization to local field conditions [

39,

40,

41,

42]. Furthermore, this paper shows the added value offered by ROIR for sustainable regional development.

2. Methodological Framework

The integration of open innovation elements in technology roadmapping (TRM) in the context of sustainable regional development is called Regional Open Innovation Roadmapping (ROIR). This framework was designed and tested in the INNOrural project. Its emphasis shifts from the roadmap as a graphical product for the developing process of the roadmap [

29]. In terms of the organization, communication work during the roadmapping process is usually a more important output than the final roadmap [

26,

27].

Following Chesbrough

et al. [

33] on OI and Phaal

et al. [

23] on TRM, ROIR can be defined as a strategic innovation planning process (“strategic roadmapping”) (

cf. [

21]) in which a roadmap for future innovation opportunities or a specific innovation is developed. Thus, the planning process describes in advance all phases of the entire innovation development chain, including R&D, prototype, implementation/mass production and market introduction in detail and usually in diagrammatic form. ROIR uses purposive in- and out-flows of knowledge to increase the internal innovation capability of the organization and to expand markets for the external use of innovation. The roadmap chart (the outcome of the process) is a time-based chart, covering a number of layers and including both commercial and technological perspectives (“multi-layer roadmap”) [

23]. Both the planning process, as well as the roadmap incorporate the following three groups of contributors (

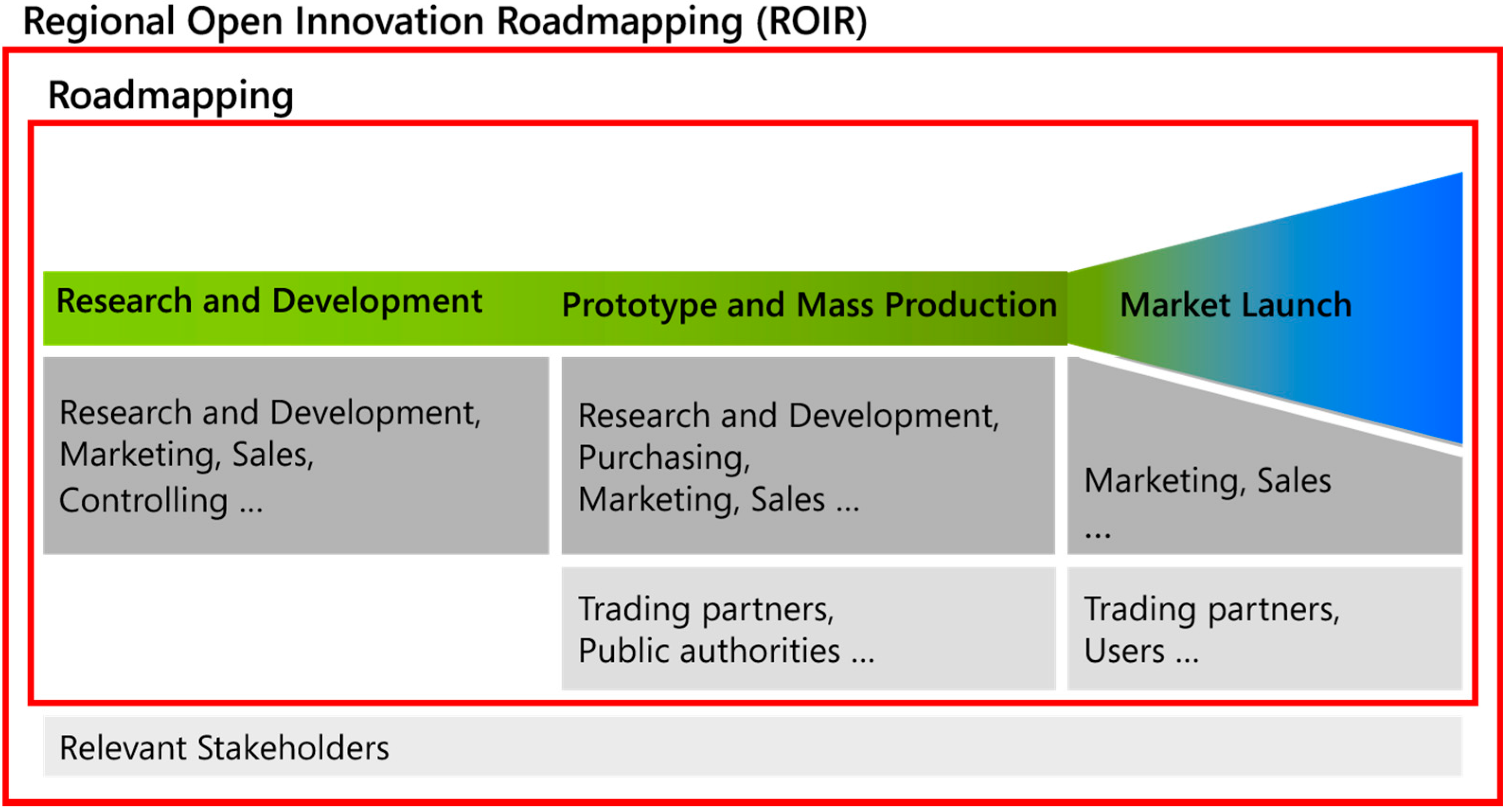

Figure 1):

- (1)

Internal contributors, which are in-house departments, like R&D, marketing, sales, controlling;

- (2)

External contributors, which are partner organizations, like trading partners, public authorities;

- (3)

Relevant stakeholders, such as single citizens and interest groups, which could be affected directly or indirectly to some extent by the development and/or market introduction of innovation.

Figure 1.

Contributors to the innovation process.

Figure 1.

Contributors to the innovation process.

ROIR uses a high level of expert knowledge. Experts are defined as individuals possessing an advanced knowledge in limited areas and having the capability to think strategically on a meta-level [

43]. One defining characteristic of the ROIR process is the cooperation between regional experts (representatives of stakeholder groups that provide deep knowledge on all matters concerning the region) and subject experts (individuals qualified to contribute additional expertise to the development and launch of the innovation, who are not necessarily from the region).

OI processes can generally be initiated in two ways: by self-recruitment and by recruitment-by-invitation. For INNOrural, recruitment-by-invitation was chosen, because the aim was to create and test an easy-to-use approach that could be conducted anywhere with minimal resources (time, money and staff). In recruitment-by-invitation, only representatives of stakeholder groups that are relevant to the process are invited to take part. The main advantage is the greater efficiency of gathering a few dozen people instead of a hundred or thousand and building and maintaining a communication process with the participants. The main obstacle is the identification of relevant stakeholder groups, which has led to the opposition of the groups not invited. Failing to identify relevant stakeholders may result in a lack of legitimation. Therefore, particular attention should be made to carefully select representatives of stakeholder groups.

Additionally, the project launched a web-based discussion platform for open innovation processes. This interactive platform was open for all stakeholders and citizens at any time, where people could inform themselves about the current project status and contribute their own ideas.

In the literature, the suggested roadmapping processes differ regarding the number of included phases, which range from three [

25,

44] to eight [

28]. However, at a minimum, most roadmapping processes are composed of the following three main steps: preliminary activity, development of TRM and follow-up activity [

28]. The INNOrural project adopted this proceeding to its specific conditions and requirements by structuring ROIR in four phases: (1) identification of regional experts; (2) selection of regional innovations (The “subject experts” are missing in

Figure 2, because at this stage of the process (Phase 1), the “regional experts” had to decide upon possible innovations. The “subject experts” were invited in Phase 3 to contribute to the specific, now selected innovations); (3) the regional innovation concept; and (4) the roadmap as a product of the process (

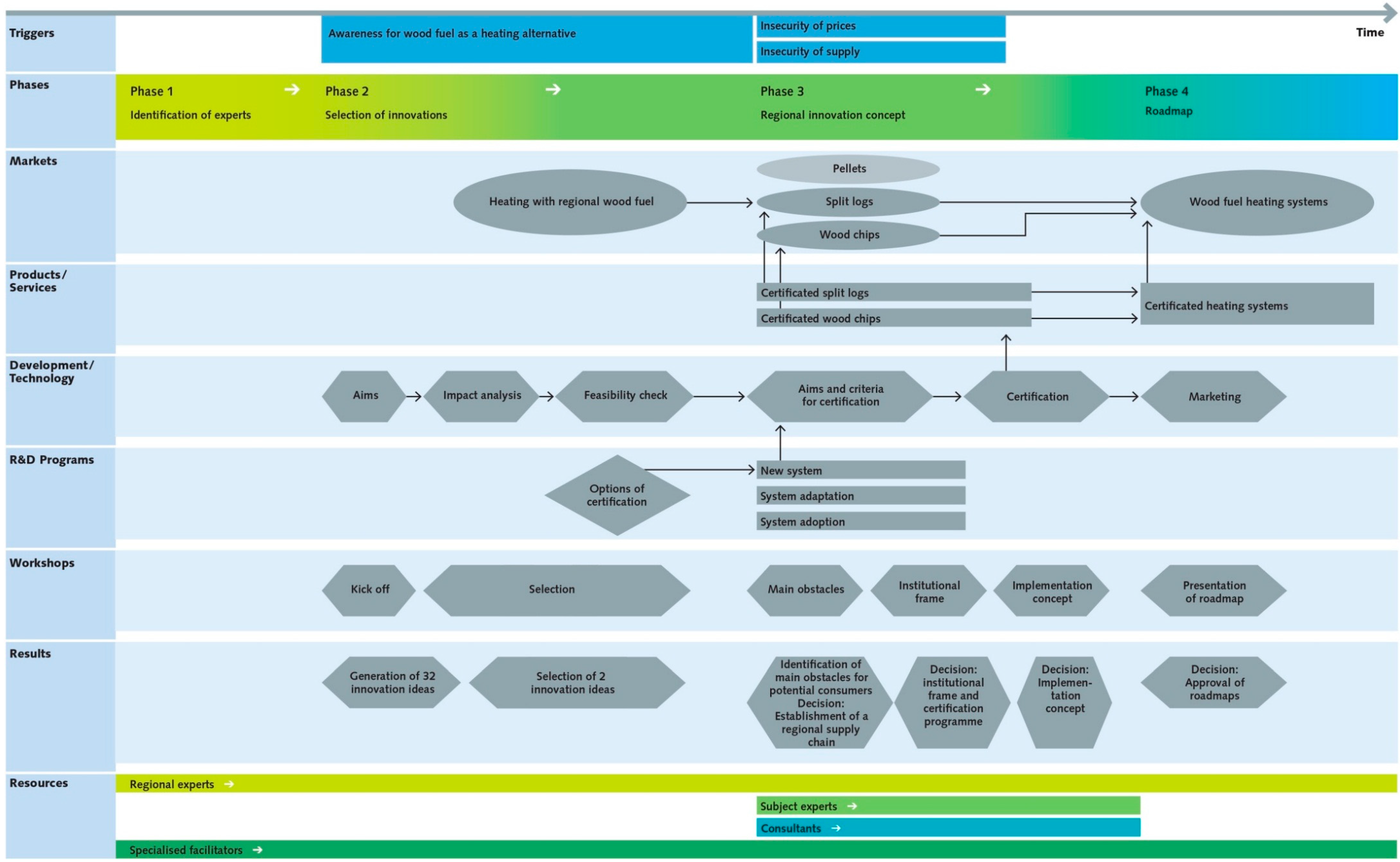

Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The ROIR process.

Figure 2.

The ROIR process.

3. Model Region, Märkisch-Oderland District

The district of Märkisch-Oderland (MOL) in Brandenburg State was selected to serve as the study region. This state is located in the eastern part of Germany, surrounding the capital, Berlin. Before reunification in 1990, it was part of the German Democratic Republic. Studies have shown that Brandenburg is stagnating at a low level with respect to R&D activities, patent applications, competitiveness and economic growth [

45,

46,

47]. The district of Märkisch-Oderland (MOL) within this state is located east of Berlin and borders Poland to the east. The peri-urban part of the district next to Berlin is home to business and industry, whereas the eastern rural area is mainly agricultural land. In 2008 (the decision to select MOL as the research area was made in 2009 on the basis of these up-to-date data of that time), the GDP per person was 15,000 EUR, which is approximately half of the average GDP for Germany (28,200 EUR) and below the average level of Brandenburg (19,700 EUR) [

48]; this indicates the rather poor economic situation of the district. MOL has the highest unemployment rate in Brandenburg (in 2008, its rate was 13.5%

versus the national rate of 12.0% [

48]). In the rural part of the district, the unemployment rate in 2008 was nearly three-times higher than the rate in peri-urban Berlin [

49]. The economic potential and future perspectives of the district were estimated to be rather weak. In a 2008 ranking of 439 regions in Germany, MOL held the 379th position, which is a slight increase of 21 ranks compared with a 2004 study [

50]. Using the typology created by Muller

et al. [

51] to describe regional innovation capacities in Europe’s new member states, Märkisch-Oderland can be categorized as an E-region, a lagging agricultural region with a relatively underdeveloped economy and structural problems linked to the loss of systemic integration.

Similar to the rest of Germany, precision farming technology (PF) (Precision farming technology is an information-guided management concept in plant production, which allows a precise and site-specific cultivation. It is based on satellite-supported positioning systems, GPS and sensor technologies. PF includes automatic data collection and processing, track guiding systems, site-specific techniques, fleet management, field robots,

etc.) in MOL failed to penetrate the market, stagnating at approximately 9% of the national market (

cf. [

42,

52]). Compared to the U.S. and other European countries, such as Denmark, the U.K. and Sweden, the adoption rate of precision farming technologies in Germany has been relatively slow [

53,

54,

55]. Experts have stressed the advantages of this technology, but farmers have been difficult to convince.

Another example is the bioenergy region initiative. MOL joined the federal funding program to establish bioenergy within the region based on wood fuel. Despite strong efforts, the region had difficulty convincing consumers of the benefits of wood fuel.

4. The Regional Open Innovation Roadmapping (ROIR) Process in the INNOrural Project

The overall project INNOrural lasted two years. The ROIR process described below took twelve months.

4.1. Phase 1: Identification of Regional Experts (Three Months)

The first phase started with extensive literature research about the study region to understand its socio-economic structure, eminent branches, authorities, organizations/unions, networks, citizens’ initiatives, topics of main discussions in the region and its parliament and existing and failed initiatives of regional development. This preliminary research laid the foundation for over 20 interviews that were conducted to obtain more in-depth insights and understanding. After the first phase, 18 people were selected as regional experts. The number of people selected depended mainly on three factors: (1) size of the region; (2) complexity/heterogeneity of the region, i.e., the number of different stakeholder groups; and (3) the structure and character of the region. Additionally, the decision concentrated on the most legitimate regional experts, either by election or qua office. Due to the rural and agricultural character of MOL, the majority of the regional experts had an agricultural or land use background. The selected regional experts were from the county’s office for agriculture, the department of the state’s ministry for agriculture, the farmers’ association, the horticultural association, the local natural reserve, environmental associations, the chamber of industry and commerce and a federal agricultural research institute located in the region.

4.2. Phase 2: Selection of Regional Innovations (Three Months)

The second phase marked the beginning of roadmapping and consisted of two day-long workshops. The first workshop served as a kick-off to explain and discuss the ROIR approach with the regional experts selected in Phase 1. Following the approach of Phaal

et al. [

19] and Phaal and Muller [

26], INNOrural aimed at answering the following three questions: (1) where are we now; (2) where do we want to go; and (3) how can we get there? The answer to the first question is mostly based on an intensive situation analysis, for instance involving “strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats” (SWOT) [

56]. Because all of our experts were very familiar with the situation of the model region, the situation analysis would have provided only a minor effect in making implicit knowledge explicit. Moreover, it would probably have limited the process to solutions close to the framing conditions. To be more effective and to find more creative innovations, the situation analysis step was skipped. The first workshop included a brainstorming session in which 32 innovation ideas were generated that seemed to be most suitable for MOL (Appendix 1). The innovation ideas covered a wide spectrum, including air boats, theme-oriented tourism, new greenhouse technologies, regional food, green energy, municipal solar collectors, precision farming technology and a wood fuel value chain. Some had been in discussion in the region, but never gained momentum.

Following the first workshop, a so-called inter-phase before the next workshop was used to assess the collected 32 innovation ideas in terms of their contribution to sustainable regional development.

Thus, the regional experts were asked to perform an impact analysis of the suggested 32 innovation ideas in written form, using the EU SENSOR (Sustainability Impact Assessment: Tools for Environmental, Social and Economic Effects of Multifunctional Land Use in European Regions framework and the ex ante Sustainability Impact Assessment Tools (SIAT) [

57].

Table 1 shows this procedure for “wood fuel”.

Table 1.

Sustainability impact factors for the innovation “wood fuel” (n = 18) [

58].

Table 1.

Sustainability impact factors for the innovation “wood fuel” (n = 18) [58].

| Main Goals | Aims | Weighting Factor | Rating of the Inno-Vation | Impact Factor |

|---|

| Economic goals | Positive employment effects

Strengthening the attractiveness of the region as tourist destination

Strengthening the attractiveness of the region as business location

Economic cooperation/networking

Creation of a unique selling proposition (USP)

Advantage in competition

Net value added

Technical feasibility | 4.55 | 0.87 | 3.96 |

| Ecologic goals | Further ecologic development of landscape and agriculture

Cooperation between landowners/land users and nature conservancy

Resource conservation | 2.18 | 0.67 | 1.46 |

| Social goals | Strengthening of identification

Potential for settlement of conflicts

Acceptance

Strengthening the attractiveness as lebensraum

Range of the innovation

Education and training measures

Promotion and maintain the cultural heritage | 2.27 | 0.43 | 0.98 |

First, the 18 regional experts disposed each of the nine points on the three main goals regarding sustainability aspects (economic, ecologic and social), then calculated the arithmetic mean of expert ratings.

Table 1 shows that the economic goals gained had a mean of 4.55, a much higher rating than mean social goals of 2.27 and mean ecologic goals of 2.18.

Secondly, each expert selected three favorite innovation ideas out of the list of 32 and estimated how likely each idea would meet every single aim (

i.e., minor goals, like “positive employment effects”) using a rating scale from +2 (“very likely to meet aim”) to −2 (“very likely to not meet aim”). The estimations were summed and averaged to determine the result ratings for every assessed innovation idea relating to the three main goals. As the second column of

Table 1 notes, the innovation idea “wood fuel” rates higher economically (0.87) than it does ecologically (0.67) or socially (0.43).

For this work, the impact factor is the product of multiplying the ratings with the weighting factors (

cf. [

26]). Thus, “wood fuel” reached 3.96 in terms of economic goals, 1.46 ecologically and 0.98 socio-economically. Summing up the three impact factors yields the total impact factor for every proposed innovation. This approach gave “wood fuel” an impact factor of 6.4.

All of the results of the impact analysis were re-distributed to the regional experts within the inter-phase to be used to determine their favorite.

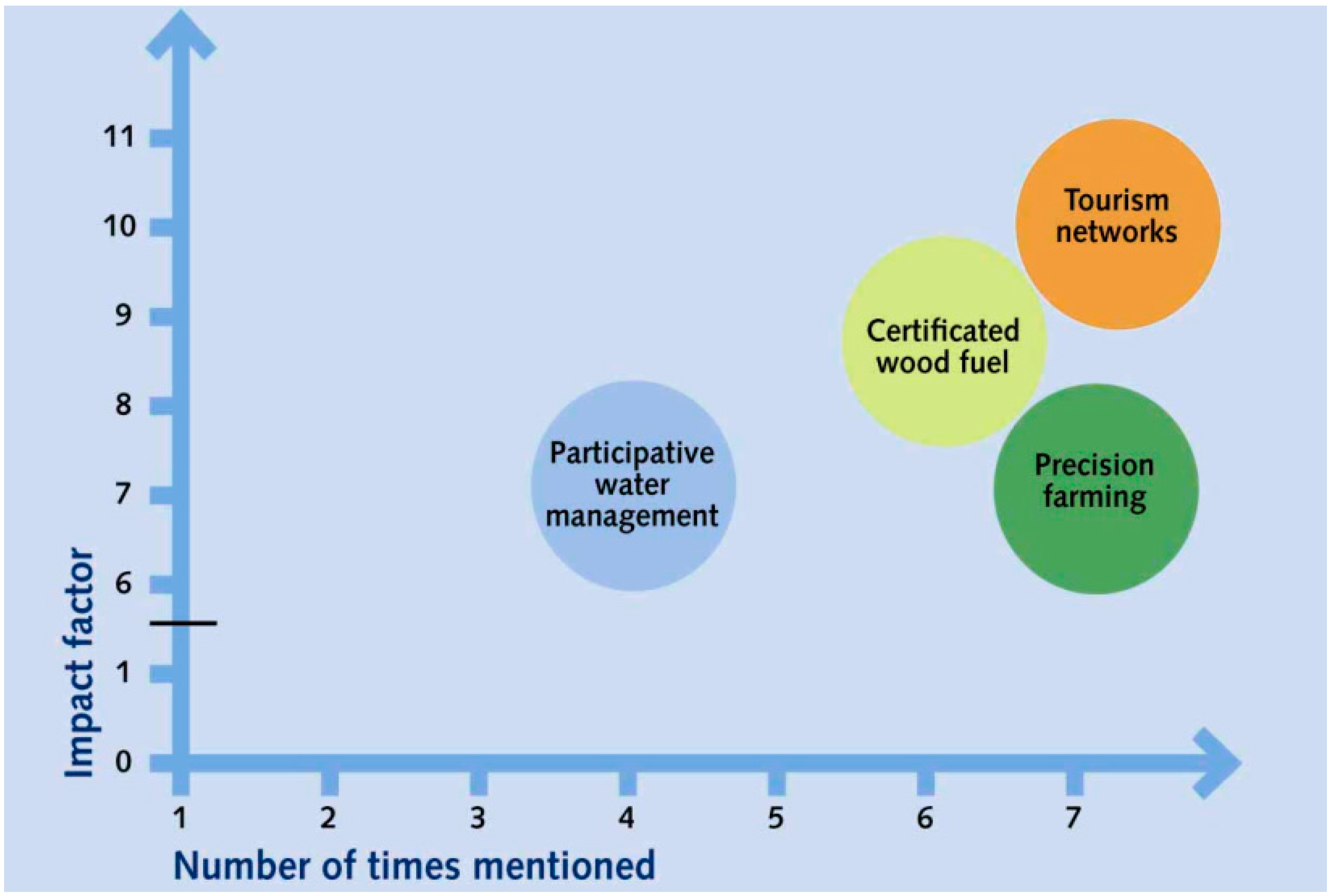

In the second workshop, the stakeholders selected two ideas to be developed in the further roadmapping process. Initially, they decided to concentrate on the four highest ranked ideas (

Figure 3). In an intensive discussion, the pros and cons of every idea were deliberated. After a feasibility check by the regional experts, two ideas were selected for the further roadmapping: (1) “certification of wood fuels”; and (2) the “establishment of a competence center for precision farming technology”. Tourism networks were not considered, because their main representatives were unable to attend the roadmapping process continuously. This exemplifies the importance of stakeholders and their selection for the outcome of the overall process. The fourth innovation idea, participative water management, was dropped due to changing general political conditions regarding the subject.

Figure 3.

Selection of innovation ideas by impact factor and mentions (n = 24) [

58].

Figure 3.

Selection of innovation ideas by impact factor and mentions (n = 24) [

58].

4.3. Phase 3: Regional Innovation Concept (Six Months)

The concept phase marks the central unit of the roadmapping process. Since the regional experts chose two innovations, both roadmapping processes were conducted simultaneously during this phase, providing the opportunity to draw comparative conclusions for both. Due to space limitations, only the roadmapping for certification using wood fuel as an example will be described in detail for Phase 3. Additionally, the main differences from roadmapping for “establishing a competence center for precision farming technology” will be discussed in the following section.

Since a roadmapping process aims at responding to the main triggers that obstruct or promote innovations, the concept phase laid out first focuses on the identification of those main triggers for the introduction of certified wood fuel in MOL. To do so, additional knowledge about marketing and market research was needed to complement the expertise of regional experts. This was provided by so-called “subject experts”, who were scientists and consultants on regional development and marketing attending the third workshop. Together with the regional experts, they identified three main obstacles for potential consumers to respond to in a regional market for wood fuel: (1) lack of awareness of wood fuel as a heating alternative; (2) insecurity of the wood supply; and (3) insecurity of prices.

To overcome these problems, the regional stakeholders decided to establish a coordinated regional supply chain and an individual certificate for regional wood fuel from the region of MOL. This was initiated to address the identified triggers in order to provide more reliable information for consumers on all aspects of wood fuel heating, to guarantee a continuous supply of wood and to ensure predictable and stable prices.

For the certification, stakeholders from all stages of the supply chain convened at the fourth workshop, including forest rangers, wood processors and energy consultants. An additional pool of subject experts was provided by the national network for wood fuel. The subject experts contributed their subject-based expertise to the development and launch of the innovation. Together with the regional experts, they provided the core set of expertise for the roadmapping process.

In the beginning, the regional experts decided on the institutional frame for implementing certification at the end of the roadmapping process. This is a crucial turning point during any roadmapping process, because the regional experts need to commit and take responsibility for the outcome of the process. Roadmapping processes will fail inevitably if a formal structure is not created for implementing the roadmap. At this point, key people will develop an eminent role, often serving as the “crystallization point” that the necessary structure will evolve around. Luckily, a key person emerged during this phase. The regional experts of wood fuel agreed to the commission of the existing bioenergy agency of MOL as the organization for the implementation phase.

Now, the main question was whether to join an existing certification program for biomass fuel, such as the “Forest Stewardship Council” (FSC) [

59] or the “Programme for the Endorsement of Forest Certification Schemes” (PEFC) [

60], and to adapt these programs to the region’s purposes or to create an independent label with its own criteria. The situation and the possibilities were discussed, assisted by the input of two certification consultants. The ultimate decision of the experts and supply chain stakeholders was to establish an independent label. Certifying authorities should be the biofuel network, since the energy agency was basically a product of the network and dependent on state funding (the bioenergy region program). The possible objectives of such a label were specified, discussed and ranked by the regional experts using a rating scale from +2 (“very relevant objective”) to zero (“irrelevant objective”) (

Table 2). Thus, the region of origin, the physical quality and the security of supplies were regarded as most essential.

Table 2.

Ranking of objectives for the certification of wood fuels (n = 18) [

58].

Table 2.

Ranking of objectives for the certification of wood fuels (n = 18) [58].

| Rank | Mean | Aims |

|---|

| 1 | 2.0 | Region of origin |

| 2 | 1.8 | Physical quality |

| 3 | 1.7 | Security of supplies |

| 4 | 1.7 | Sustainability (economical) |

| 5 | 1.4 | Sustainability (ecological) |

| 6 | 1.3 | Control and warranty |

| 7 | 1.2 | Sustainability (social) |

| 8 | 1.1 | Publicity of regional products |

| 9 | 1.1 | Transparency |

| 10 | 0.9 | Costs of certification |

The fifth workshop was designed to formulate a more precise concept to implement the objectives. In order to assess the achievements of the objectives, both expert groups (regional and subject experts) set up concrete indicators. The objective “region of origin” was therefore underpinned by the obligation to offer a minimum of 50% region-based raw material. “Physical quality” had to be assured by using legal classification, and the “security of supplies” was provided by long-term contracts and security supply storage. In particular, physical quality, the security of supply and social sustainability evoked controversial discussions. However, all of the issues were successfully resolved by the end of the workshop.

In the following interphase, different expert subgroups developed parts of the certification statutes, applying the set up indicators to different parts of the supply chain, like wood processors or energy consultants, going in-depth to solve the last questions, i.e., how to maintain the security supply storage or how to secure supplies when streets are blocked due to hard winters. Solutions to all questions were then merged in the sixth workshop. Certification consultants accompanied this process with a consistency check to ensure that all parts would work flawlessly together during the implementation. The last step focused on marketing the certificate.

All regional experts then agreed on the final product, a concise roadmap to introduce and communicate the certification of wood fuels in MOL (

Figure 4). The focus was on three products: wood chips, split logs and heating installation. Since a pellet-producing facility does not exist in MOL, this market could not be addressed by individually certified products. The remaining steps concerned the registration at the German Patent and Trademark Office in Munich and certification of the first supply chain members.

4.4. Phase 4: Roadmap (One Week)

The final assembly was under the patronage of the political district administrator and all of the participants of the two INNOrural processes gathered together. Regional experts, subject experts and additional consultants presented both roadmaps for the region of MOL. Hereafter, the organizations commissioned to carry out the implementation of both roadmaps introduced the implementation plan to the public and the press to obtain broader impact, e.g., to convince both consumers and companies of the benefits of certified wood fuel. In the afternoon, the experiences and outcomes of ROIR were discussed. All of the participants agreed that ROIR had helped them select and plan innovations they considered to be highly useful for their region. Without ROIR, the same result would not have been achieved due to the lack of know-how and manpower to organize the process.

4.5. Comparison to Precision Farming Roadmapping

The second roadmapping process concerned the “establishment of a competence center for precision farming technology” (

Table 3). The objective was to promote the new farming technologies in Brandenburg State. The installation of a competence center was considered crucial to overcome the following implementation obstacles for farmers: (1) lack of information regarding the range of products, profitability and constraints; (2) lack of practical skills; and (3) lack of support. Due to high investment costs, most farmers had not been introduced to the new technology.

Figure 4.

The complete ROIR process.

Figure 4.

The complete ROIR process.

In contrast to wood fuel roadmapping, an efficient stakeholder network for precision farming did not exist in MOL. Single stakeholders had to be identified and convinced to help build a network of farmers, technology developers, industry representatives, farm consultants and a national agricultural research institute to be located in the region. They agreed on designing a roadmap for a three-year pilot phase. This roadmap laid the basis for a project proposal to request financial support from the European LEADER program for installing the competence center. Its purpose will be to disseminate knowledge about precision farming technologies throughout Brandenburg State. In contrast to the wood fuel process, the implementation of the precision farming roadmap relied on outside funding.

Table 3.

Comparison of both roadmapping processes (“wood fuels” and “precision farming”).

Table 3.

Comparison of both roadmapping processes (“wood fuels” and “precision farming”).

| Criteria | Wood Fuels | Precision Farming |

|---|

| Objective | Promotion of wood fuel as a heating alternative by establishing a regional supply chain certificate for regional wood | Promotion of new farm technologies by establishment of a competence center for precision farming technology |

| Target group | Consumers | Farmers |

| Identified obstacles | Lack of awareness of wood fuel as a heating alternative

Insecurity of prices

Insecurity of supply | Lack of information

Lack of practical skills

Lack of support |

| Initial situation | Stakeholder network existed | No stakeholder network existed |

| Key stakeholders | Forest rangers

Wood processors

Energy consultants | Farmers

Technology developers

Industry representatives

Farm Consultants

National agricultural research institute |

| Workshops | Six

(kick-off, selection, main obstacles, institutional frame, implementation concept, presentation of roadmap) | Six

(kick-off, selection, main obstacles, institutional frame, implementation concept, presentation of roadmap) |

| Implementation obstacles | None | Dependence on outside funding |

| Implementation | Successful | Successful |

In both roadmapping processes, specific key regional experts were essential for their success. These individuals strongly believed in the innovations and were economically connected to the outcome. Their attitude also stimulated others to join the process. A careful identification of stakeholders therefore proved to be one of the major success factors.

Both roadmapping processes were supported by external moderators and scientists with process competence. This helped the stakeholders concentrate on their issues without being side-tracked. The moderators added an outside perspective and addressed neglected topics.

5. Discussion

Generally, the ROIR approach is based on an innovation-oriented regional development perspective, which has a long tradition in the European policy. In the 1990s, the broadly aligned EU programs for innovation-oriented regional development RIS and RITTS were implemented in numerous European regions. The objective of RIS was to build partnerships among key innovation actors and to draw up regional innovation strategies. The early contribution of RIS/RITTS to innovation has been recently extended to EU strategic and funding instruments, such as the Structural Funds under RTDI (Research, Technological Development and Innovation) priorities [

61], as well as in further regional innovation activities and externally founded projects, such as EURIS [

35]. The mentioned objectives of the RIS/RITTS initiative represent a crucial link to the INNOrural project.

Comparing ROIR with regional foresight, many similarities can be found, e.g., regarding objectives, issues and methods. Kindras

et al. [

10] stated that innovation in regional foresight interlinks all types of factors and actors, aiming at creating a network among key actors of regional innovation systems (mainly firms, research organizations, public institutions, financial companies and technology intermediates). This fully applies to ROIR, as well. However, there is also a significant difference between the two approaches. Regional foresight aims at identifying future innovation potentials and development priorities for strategic decisions in regions [

10,

15,

17], whereas the ROIR process is more implementation-oriented by intending to start and realize innovation activities.

Regional foresight studies use different methods, such as expert panels, group discussions, scenarios or, in rare cases, roadmapping [

10,

62]. In the Samara case study, regional experts were involved to build scenarios and integrate these scenarios into a roadmap (

cf. [

10]). In ROIR, the experts not only served to identify regional targets for socio-economic development, but also assessed the sustainability aspects of innovative ideas. The

ex ante sustainability assessment in ROIR determines which innovative idea will be pursued.

An interesting framework that considers open innovation and tries to find solutions to cope with regional problems and to foster regional development is the living labs concept, which was examined in the C@R (Collaboration and Rural) project [

34]. Further similarities between ROIR and living labs are the openness for a broad range of stakeholders, the partnership and network creation and operation across different development stages, the detection of potential future business or innovations and the feasibility analysis of inventions. However, living labs is seen as a more user-centric approach. Furthermore, the living labs approach provides less guidance, such as a business plan for implementation and a standardized methodology. Thus, instruments and forms of participation are not clearly defined. Through the application of the TRM approach, ROIR provides a strategic and structured methodology that is relevant and helpful for the transferability of the approach to other regions

Regardless of its final implementation, the ROIR process and the final roadmap was highly appreciated by the participating stakeholders. It allowed stakeholders to reflect on their respective situation and options regarding sustainable regional development and in the face of new challenges. Van den Bosch

et al. [

27] (p. 1033) stated that their roadmapping approach “facilitated interaction between stakeholders, which not only made it possible to formulate a common vision, but also helped in developing new relationships between different stakeholders.” With ROIR, new cooperation, networks and even a wood supply chain were established. Lee

et al. [

28] also confirmed that roadmapping contributes to the formation of stakeholder networks. Currently, the open innovation strategy is being considered for building and reinforcing strong networks [

35]. What made the INNOrural project special was that it fell back on existing networks. Thus, existing innovation ideas and inventions were continued, refined and, to a certain extent, realized.

Generally, roadmapping offers various opportunities regarding the methodology [

28,

29], but workshops and interviews with experts or stakeholders are very common [

10,

19,

26,

27]. The development of innovation in regional contexts can only be successful with collective action from different stakeholders. Van den Bosch

et al. [

27] confirmed this in their case study and underlined that it is crucial to obtain the commitment of stakeholders.

ROIR provides a framework for communication within the region and across regional boundaries by allowing actors and stakeholders of a region who had rarely met to now get together to recognize and find ways to solve their problems. External experts bring specific subject expertise and experiences from other regions into the discussion. Regarding smart city development, Lee

et al. [

28] stated that with the integration of participation methods (e.g., workshops, interviews and surveys), the roadmapping process becomes a communication platform for knowledge exchange on the city and inter-city levels.

Often, roadmapping processes are regarded as time-consuming and expensive, especially when using participatory methods. Nonetheless, strategic planning, like TRM, aims at saving the time and resources of companies and organizations in the long run. Within the wide range of TRM approaches, some use more basic and easy-to-adopt methods, like the fast start method [

23]. ROIR is also designed as a lean, easy-to-use and manageable process for conducting expert workshops as a key method within the roadmapping process. The use of less complex methods, such as expert panels and group discussions, is also seen as beneficial in regional foresight studies (

cf. [

10]).

The ROIR framework may appear to be rather simple, but this simplicity is one of its advantages: it helps to increase transparency about the process and the results among all participants; and it can be used by non-experts, which is a precondition for a wider application in other regions. It is theoretically an interdisciplinary effort placed into the context of its primary concept, TRM. Nonetheless, most applications still remain confined to a specific sector [

20] and/or companies [

29]. ROIR, however, overcomes these limitations, because it is interdisciplinary, trans-sectoral and, to a certain extent, trans-regional. On the one hand, this offers different “cultures” to approach challenges, which can complement each other. On the other hand, cultural differences can cause difficulties, especially in the starting phase. All participants need to find their role within the process and to agree on norms and rules [

63]. Stakeholders of a larger region are by far more heterogeneous than those of any particular business sector. Therefore, these first phases are crucial for overall roadmapping and require much more attention. TRM is mainly about technological innovations for technological problems. In contrast, ROIR for sustainable regional development also addresses non-technical, so-called “social innovations”,

i.e., the build-up of networks or supply chains under consideration of sustainability aspects. These mainly focus on transactions [

64,

65]. Such transactions require special explanatory efforts, because they are intangible (as opposed, for instance, to the construction of an engine or a building). This intangibility is one reason for the widespread underestimation of social innovation potentials and for the difficulties in funding those approaches.

To gain legitimacy within the region, ROIR must provide transparency, comprehensibility and rationality about (1) the procedure and methodology within the roadmapping process and (2) the selection of stakeholders and experts:

- (1)

Regarding the procedure, INNOrural used a clear and reasonable method to assess the sustainability of innovation ideas, which consider ecological, economic and social aspects. This method was applied in alignment with the

ex ante Sustainability Impact Assessment Tools (SIAT) for land use in European regions [

57].

- (2)

Regarding the selection of stakeholders, the process must also be open to supplemental stakeholders and recommendations from outside during the process. In INNOrural, this was achieved by integrating external experts (so-called subject experts) and providing a web-based communication platform. Supporting staff (e.g., external moderators and scientists) should be on hand for at least some time during the implementation phase to provide continuity.

In regards to the role of the researcher in this study, the developed project methodology can be seen as a form of action research, in which the researcher facilitates the roadmapping processes. Van den Bosch

et al. [

27] also conducted action research and stated that the researcher therefore has influence on the process. From this finding, the authors conclude “that there might be a role for universities and other independent knowledge institutes in mobilizing stakeholders in early stages of innovation processes.” [

27] (p. 1035).

6. Conclusions

TRM and OI are broadly used to safeguard the development and market introduction of company innovations. ROIR merges the benefits of both approaches and applies them to the regional scale as a tool to provide innovation-based regional development that includes an ex ante sustainability assessment of innovation ideas. This approach was used to identify promising innovation ideas with regard to sustainable regional development and to test these in two parallel roadmapping processes in the economically stagnating region of Märkisch-Oderland (MOL) in Germany. The two roadmapping processes are the certification of wood fuel and the establishment of a competence center for precision farming technology. Both processes lasted twelve months each.

Methodologically, ROIR provided a systematic approach to overcome obstacles in the innovation process for the implementation and diffusion of innovations. It helped to address high complexity in an easy-to-use procedure, even by stakeholders not familiar with this process. Some of the main aspects of ROIR to support success are the inclusion of all relevant stakeholder groups early on in the process to portray the heterogeneity of the region and the cooperation between regional and subject experts to provide the core set of expertise that is indispensable for an open roadmapping process to succeed. Furthermore, the identification and inclusion of key individuals, the use of existing networks and structures and the use of external facilitators to support the process were helpful in the RIOR process.

From the case study perspective, both ROIR processes seem to be successful. The certification of wood fuel value chain and the installation of a precision farming competence center for Brandenburg State both made the step from plan (roadmap) to reality within three years. The wood fuel value chain has been attracting a rising number of participants. Now, a majority of companies concerned with wood fuel within the study area hold certificates, gaining a market coverage from 25% (wood sticks) to more than 50% (energy consultants and installation). Following the ROIR, the establishment of a competence center for precision farming technology was provided with an EU LEADER program fund, supporting the competence center and twelve demonstration farms for five years.

Generally, a broader adaptation of ROIR for additional regions will be useful, e.g., the ROIR framework was applied by the ZFARM project (Zero Acreage Farming—Städtische Landwirtschaft der Zukunft) [

66] in an urban agriculture context.

Nevertheless, the ROIR processes need to be evaluated in depth to develop a better understanding and to provide evidence of the benefits and limitations of the ROIR approach. Carvalho

et al. [

29] (p. 13) already identified a gap in TRM research, in which the benefits of TRM were described “primarily on the basis of the perceptions of the stakeholders who were involved” and were not measured quantitatively. With the outcome of this evaluation, further research is recommended in regards to larger and more complex regions or for more controversial innovations. The proposed evaluation, the transfer to broader contexts and the generalizability demonstrate that ROIR may be a powerful tool for sustainable regional development. On a case study level, the positive impact of ROIR was visible and perceptible.