Understanding Attitudes and Pro-Environmental Behaviors in a Chilean Community

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Pro-Environmental Attitudes Studies in Latin American Countries

1.2. Attitudinal Factors Influencing Environmental Behaviors

1.3. Socio-Demographic Factors Influencing Environmental Behavior

1.4. Overview

2. Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Materials

| Environmental Behavior Subscales | Mean | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Power Conservation (α = 0.67) (b) | |||

| (a) (c) | PC1. In winter, I keep the heat at such a temperature that I can wear light clothing inside my house. | 3.82 | 1.35 |

| (a) (c) | PC2. In winter, I leave the windows of my house open for long periods of time to air the house. | 2.55 | 1.40 |

| PC3. In winter, I turn off the heat in my house at night. | 4.54 | 0.96 | |

| PC4. In winter, when I leave my house for more than 30 min, I turn off the heat. | 4.53 | 0.94 | |

| PC5. I make the most use out of natural light. | 4.66 | 0.67 | |

| PC6. I turn off any lights I’m not using. | 4.50 | 0.82 | |

| (a) | PC7. I unplug any electrical appliances I’m not using. | 3.55 | 1.43 |

| Ecologically Aware Consumer Behavior (α = 0.68) | |||

| EAC1. I buy biodegradable detergents to wash laundry. | 3.31 | 1.58 | |

| EAC2. I buy organic products. | 2.97 | 1.42 | |

| EAC3. I buy rechargeable batteries. | 3.16 | 1.54 | |

| EAC4. I buy energy-efficient light bulbs. | 4.14 | 1.23 | |

| EAC5. I buy products in reusable or returnable containers. | 3.92 | 1.22 | |

| Biodiversity Protection (α = 0.56) (d) | |||

| (a) | BP1. After spending a day outdoors, I leave the site as clean as it was when I got there. | 4.70 | 0.66 |

| BP2. I visit national parks and/or nature reserves. | 2.90 | 1.40 | |

| BP3. I take my pet to the veterinarian. | 3.66 | 1.62 | |

| (c) | BP4. I collect plants, seeds and organic matter when I visit natural areas. | 3.79 | 1.53 |

| Water Conservation (α = 0.63) (b) | |||

| WC1. I try to repair leaky faucets quickly. | 4.42 | 0.94 | |

| (a) (c) | WC2. I leave the water running in the shower until it reaches the proper temperature. | 2.51 | 1.47 |

| WC3. I try to turn off the faucet when I brush my teeth. | 4.16 | 1.18 | |

| WC4. I wait until I have a full load of laundry before putting it in the washing machine. | 4.36 | 1.01 | |

| WC5. I try to take short showers (less than 5 min). | 3.58 | 1.40 | |

| Rational Automobile Use (α = 0.46) (d) | |||

| RAU1. To travel short distances (less than 10 blocks), I prefer to walk or use a bike. | 3.97 | 1.37 | |

| (a) | RAU2. I share a car. | 3.35 | 1.57 |

| RAU3. I drive in such a way to minimize the amount of gas I consume. | 4.08 | 1.17 | |

| RAU4. I refrain from driving a car on days of high pollution levels. | 3.25 | 1.56 | |

| (a) (c) | RAU5. I honk the horn when I drive. | 3.60 | 1.29 |

| Ecological Waste Management (α = 0.88) (b) | |||

| (a) | EWM1. When I go shopping, I use cloth instead of plastic bags. | 2.55 | 1.54 |

| (a) | EWM2. I reuse plastic bags (from the supermarket). | 4.24 | 1.19 |

| EWM3. I sort leftover food to make compost. | 1.58 | 1.32 | |

| EWM4. I sort papers and cardboard for recycling. | 2.17 | 1.69 | |

| EWM5. I sort soda cans for recycling. | 1.97 | 1.60 | |

| EWM6. I sort glass containers for recycling. | 2.26 | 1.75 | |

| EWM7. I sort batteries for recycling. | 1.83 | 1.51 | |

| EWM8. I sort electrical/electronic appliances for recycling. | 1.94 | 1.59 | |

| Predictor Variables | Mean | SD | B | β | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biospheric Values (α = 0.79) | 0.22 | 0.30 *** | |||

| PV1. A person who believes that everyone must look after the environment. | 4.43 | 0.92 | 1.00 | 0.77 *** | |

| PV2. A person who respects the environment and believes that we should live in harmony with other living beings. | 4.52 | 0.78 | 0.94 | 0.86 *** | |

| Altruistic Values (α = 0.70) | 0.04 n.s. | 0.06 n.s. | |||

| PV3. A person who believes it is important to help others around them. | 4.50 | 0.77 | 1.00 | 0.88 *** | |

| PV4. A person who believes in the fair treatment of all people, including persons who are unknown to them. | 4.39 | 0.91 | 0.84 | 0.62 *** | |

| Egoistic Values (α = 0.70) | −0.18 | −0.26 *** | |||

| PV5. A person who makes decisions and likes to be a leader. | 3.28 | 1.35 | 1.00 | 0.55 *** | |

| PV6. A person who believes it is important to have a lot of money. | 2.55 | 1.31 | 1.23 | 0.70 *** | |

| PV7. A person who believes it is important to have influence over people and their actions. | 2.84 | 1.39 | 1.41 | 0.76 *** | |

| Ecological Vision (α = 0.64) (b) | 0.31 | 0.57 *** | |||

| NEP1. In recent times, the human population has grown at a faster rate than the planet can support. | 4.25 | 1.09 | 1.00 | 0.47 *** | |

| NEP2. The earth has limited resources and space (e.g., like a space ship). | 4.13 | 1.23 | 0.64 | 0.27 *** | |

| (a) | NEP3. Human beings have the right to modify the environment as fits their needs. | 3.13 | 1.52 | -- | -- |

| NEP4. Plants and animals have the same right to life as human beings. | 4.31 | 1.08 | 1.13 | 0.54 *** | |

| (a) | NEP5. Nature is sufficiently strong to support the impacts produced as a result of modern life. | 2.63 | 1.45 | -- | -- |

| NEP6. The balance of nature is very fragile and easily disrupted. | 4.26 | 1.05 | 1.24 | 0.60 *** | |

| (a) | NEP7. Most environmental problems can be solved through the application of more and better technology. | 3.59 | 1.39 | -- | -- |

| (a) | NEP8. Human beings will learn enough about how nature works to be able to control it. | 3.12 | 1.43 | -- | -- |

| (a) | NEP9. Environmental degradation is not as bad as people normally say it is. | 1.96 | 1.31 | -- | -- |

| NEP10. If things continue on the current path, we will soon experience a major natural disaster. | 4.14 | 1.20 | 1.29 | 0.56 *** | |

| Awareness of Consequences (α = 0.81) (b) | 0.97 | 0.80 *** | |||

| AC1. Protecting the environment benefits everyone. | 4.85 | 0.48 | 1.25 | 0.75 *** | |

| AC2. Protecting the environment will help to improve the quality of life for everyone. | 4.83 | 0.48 | 1.38 | 0.83 *** | |

| AC3. Protecting the environment will create a better world for me and my family. | 4.82 | 0.49 | 1.29 | 0.85 *** | |

| AC4. Degradation of the environment directly affects my health (e.g., air pollution). | 4.74 | 0.65 | 1.00 | 0.51 *** | |

| (a) | AC5. Environmental degradation caused in my neighborhood will often affect people in other parts of the world. | 4.17 | 1.20 | -- | -- |

| (a) | AC6. In the next 10 years, thousands of animal and plant species will go extinct. | 4.32 | 1.06 | -- | -- |

| Ascription of Responsibility (α = 0.60) (b) | 0.51 | 0.85 *** | |||

| AR1. Every person is responsible for protecting the environment. | 4.75 | 0.68 | 1.00 | 0.57 *** | |

| AR2. The government bears the most responsibility for protecting the environment. | 4.25 | 1.25 | 0.22 | 0.07 * | |

| AR3. Corporations bear the most responsibility for reducing environmental degradation. | 4.66 | 0.84 | 0.45 | 0.21 *** | |

| AR4. My household is responsible for reducing environmental degradation. | 4.50 | 0.91 | 1.04 | 0.45 *** | |

| AR5. All households are responsible for reducing environmental degradation. | 4.67 | 0.72 | 0.96 | 0.53 *** | |

| (a) | AR6. I am unwilling to cooperate to reduce environmental degradation if others do not do same. | 1.88 | 1.39 | -- | -- |

| Personal Norms (α = 0.70) | 0.90 | 0.48 *** | |||

| PN1. I have a moral obligation to protect the environment. | 4.56 | 0.84 | 2.16 | 0.62 *** | |

| PN2. Environmental problems cannot be ignored. | 4.81 | 0.53 | 1.65 | 0.75 *** | |

| PN3. I think it is important that people protect the environment. | 4.86 | 0.43 | 1.40 | 0.77 *** | |

| PN4. The government should require greater environmental protections. | 4.81 | 0.57 | 0.91 | 0.38 *** | |

| PN5. Corporations should reduce their impact in degrading the environment. | 4.85 | 0.53 | 1.00 | 0.45 *** | |

2.3. Procedure and Participants

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Internal Consistency Analysis

3.2. Descriptive Results

| Socio-demographic Variable | Environmental Behavior Subscales | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EBSPC | EBSEAC | EBSWC | EBSEWM | |||||

| Gender | ||||||||

| Male | 4.53 | (0.65) | 3.49 | (0.93) | 4.13 | (0.78) | 1.91 | (1.17) |

| Female | 4.58 | (0.57) | 3.52 | (0.92) | 4.12 | (0.80) | 2.01 | (1.27) |

| Socio-Economic Status (SES) | ||||||||

| High | 4.51 b,c | (0.61) | 3.57 a | (0.92) | 4.07 a | (0.77) | 2.12 a | (1.34) |

| Middle-High | 4.66 a | (0.48) | 3.58 a | (0.92) | 4.24 b | (0.82) | 2.05 a | (1.26) |

| Middle | 4.59 a,b | (0.58) | 3.53 a | (0.92) | 4.14 a,b | (0.84) | 1.93 a,b | (1.19) |

| Middle-Low | 4.48 c | (0.71) | 3.33 b | (0.90) | 4.04 a | (0.74) | 1.78 b | (1.10) |

| Age group | ||||||||

| 18–29 | 4.52 a | (0.60) | 3.39 a | (0.87) | 3.93 a | (0.75) | 1.84 a,b | (1.11) |

| 30–44 | 4.52 a | (0.64) | 3.53 a,b | (0.93) | 4.07 a,b | (0.79) | 1.81 a | (1.16) |

| 45–59 | 4.57 a,b | (0.56) | 3.58 b | (0.92) | 4.17 b,c | (0.80) | 2.06 b,c | (1.31) |

| 60+ | 4.67 b | (0.59) | 3.54 a,b | (0.95) | 4.37 c | (0.79) | 2.27 c | (1.31) |

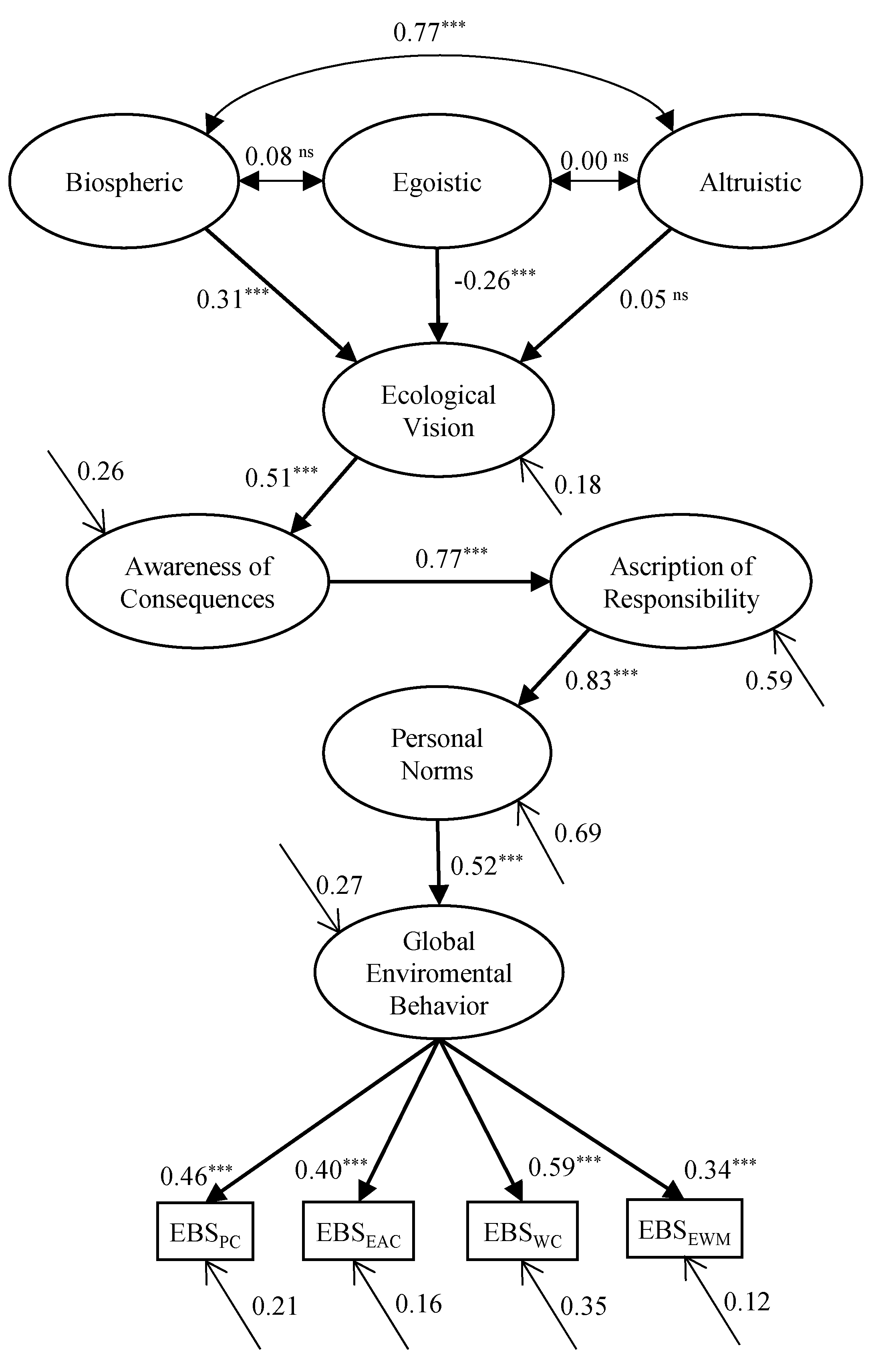

3.3. Structural Equation Model

4. Discussions

Environmental Behavior Subscales

5. Limitations of the Study

6. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References and Notes

- Buttel, F.H. Environmentalization: Origins, Processes, and Implications for Rural Social Change1. Rural Sociol. 1992, 57, 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Brechin, S.R.; Kempton, W. Global environmentalism: A challenge to the postmaterialism thesis? Soc. Sci. Q. 1994, 75, 245–269. [Google Scholar]

- Schultz, P.W.; Zelezny, L.C. Values as predictors of environmental attitudes: Evidence for consistency across 14 countries. J. Environ. Psychol. 1999, 19, 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlap, R.E.; Mertig, A.G. Global concern for the environment: Is affluence a prerequisite? J. Soc. Issues 1995, 51, 121–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, P.W.; Unipan, J.B.; Gamba, R.J. Acculturation and ecological worldview among Latino Americans. J. Environ. Educ. 2000, 31, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, B.D. The garden and the sea: US Latino environmental discourses and mainstream environmentalism. Soc. Probl. 1993, 40, 108–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, P.W.; Zelezny, L.C. Values and Proenvironmental Behavior A Five-Country Survey. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 1998, 29, 540–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Groot, J.I.M.; Steg, L. Value Orientations and Environmental Beliefs in Five Countries Validity of an Instrument to Measure Egoistic, Altruistic and Biospheric Value Orientations. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2007, 38, 318–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milfont, T.L.; Duckitt, J.; Wagner, C. A cross-cultural test of the value-attitude-behavior hierarchy. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 40, 2791–2813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corral-Verdugo, V. A structural model of reuse and recycling in Mexico. Environ. Behav. 1996, 28, 665–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corral-Verdugo, V.; Armendariz, L.I. The “new environmental paradigm” in a Mexican community. J. Environ. Educ. 2000, 31, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menzel, S.; Bögeholz, S. Values, beliefs and norms that foster Chilean and German pupils’ commitment to protect biodiversity. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Educ. 2010, 5, 31–49. [Google Scholar]

- Cordano, M.; Welcomer, S.; Scherer, R.F.; Pradenas, L.; Parada, V. A Cross-Cultural Assessment of Three Theories of Pro-Environmental Behavior A Comparison Between Business Students of Chile and the United States. Environ. Behav. 2011, 43, 634–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, C.F.; Kotchen, M.J.; Moore, M.R. Internal and external influences on pro-environmental behavior: Participation in a green electricity program. J. Environ. Psychol. 2003, 23, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C. Toward a coherent theory of environmentally significant behavior. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heath, Y.; Gifford, R. Extending the Theory of Planned Behavior: Predicting the Use of Public Transportation 1. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2006, 32, 2154–2189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamberg, S.; Ajzen, I.; Schmidt, P. Choice of travel mode in the theory of planned behavior: The roles of past behavior, habit, and reasoned action. Basic Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 25, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, H.W.; Åberg, L. Drivers’ decision to speed: A study inspired by the theory of planned behavior. Transp. Res. Part F 2006, 9, 427–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, F.G.; Hübner, G.; Bogner, F.X. Contrasting the Theory of Planned Behavior With the Value-Belief-Norm Model in Explaining Conservation Behavior. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2005, 35, 2150–2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, R.E.; Dunlap, R.E. The Social Bases of Environmental Concern: Have They Changed Over Time? Rural Sociol. 1992, 57, 28–47. [Google Scholar]

- Steg, L.; Vlek, C. Encouraging pro-environmental behaviour: An integrative review and research agenda. J. Environ. Psychol. 2009, 29, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C.; Dietz, T.; Abel, T.D.; Guagnano, G.A.; Kalof, L. A value-belief-norm theory of support for social movements: The case of environmentalism. Hum. Ecol. Rev. 1999, 6, 81–98. [Google Scholar]

- Dunlap, R.E.; van Liere, K.D. A proposed measuring instrument and preliminary results: The ‘New Environmental Paradigm’. J. Environ. Educ. 1978, 9, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordlund, A.M.; Garvill, J. Value structures behind proenvironmental behavior. Environ. Behav. 2002, 34, 740–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar-Luzón, M.C.; García-Martínez, J.M.A.; Monteoliva-Sánchez, A.; de Lecea, J.M.S. El modelo del valor, las normas y las creencias hacia el medio ambiente en la predicción de la conducta ecológica. Medio Ambient. Comport. Hum. 2006, 7, 21–44. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- López-Mosquera, N.; Sánchez, M. Theory of Planned Behavior and the Value-Belief-Norm Theory explaining willingness to pay for a suburban park. J. Environ. Manag. 2012, 113, 251–262. [Google Scholar]

- Andersson, L.; Shivarajan, S.; Blau, G. Enacting ecological sustainability in the MNC: A test of an adapted value-belief-norm framework. J. Bus. Eth. 2005, 59, 295–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, M.; Rahm, J.; Gyllin, M. Landowners’ Participation in Biodiversity Conservation Examined through the Value-Belief-Norm Theory. Landsc. Res. 2012, 28, 295–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C. Information, incentives, and proenvironmental consumer behavior. J. Consum. Policy 1999, 22, 461–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar-Luzón, M.C.; Monteoliva, A.; García, J.M.A. Influencia de las normas, los valores, las creencias ambientales responsables y la conducta pasada sobre la intención de reciclar. Medio Ambient. Comport. Hum.: Rev. Int. Psicol. Ambient. 2005, 6, 23–36. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Steg, L.; Dreijerink, L.; Abrahamse, W. Factors influencing the acceptability of energy policies: A test of VBN theory. J. Environ. Psychol. 2005, 25, 415–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cottrell, S.P. Influence of sociodemographics and environmental attitudes on general responsible environmental behavior among recreational boaters. Environ. Behav. 2003, 35, 347–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raudsepp, M. Some socio-demographic and socio-psychological predictors of environmentalism. TRAMES J. Hum. Soc. Sci. 2001, 5, 355–367. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, J.; Saijo, T. Reexamining the relations between socio-demographic characteristics and individual environmental concern: Evidence from Shanghai data. J. Environ. Psychol. 2008, 28, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Liere, K.D.; Dunlap, R.E. The social bases of environmental concern: A review of hypotheses, explanations and empirical evidence. Public Opin. Q. 1980, 44, 181–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blocker, T.J.; Eckberg, D.L. Gender and environmentalism: Results from the 1993 general social survey. Soc. Sci. Q. 1997, 78, 841–858. [Google Scholar]

- Tindall, D.B.; Davies, S.; Mauboules, C. Activism and conservation behavior in an environmental movement: The contradictory effects of gender. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2003, 16, 909–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.D.; Peterson, M.N.; Hull, V.; Lu, C.T.; Lee, G.D.; Hong, D.Y.; Liu, J.G. Effects of attitudinal and sociodemographic factors on pro-environmental behaviour in urban China. Environ. Conserv. 2011, 38, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diekmann, A.; Preisendörfer, P. Environmental behavior discrepancies between aspirations and reality. Ration. Soc. 1998, 10, 79–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, C.; Hong, D. Gender differences in environmental behaviors in China. Popul. Environ. 2010, 32, 88–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, C.; McCright, A.M. A Test of the Biographical Availability Argument for Gender Differences in Environmental Behaviors. Environ. Behav. 2014, 46, 241–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, L.M.; Hatch, A.; Johnson, A. Cross-National Gender Variation in Environmental Behaviors. Soc. Sci. Q. 2004, 85, 677–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietz, T.; Stern, P.C.; Guagnano, G.A. Social structural and social psychological bases of environmental concern. Environ. Behav. 1998, 30, 450–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcury, T.A.; Christianson, E.H. Environmental worldview in response to environmental problems Kentucky 1984 and 1988 compared. Environ. Behav. 1990, 22, 387–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, S.E.; Laska, S.B. The Changing Face of the Environmental Coalition A Research Note. Environ. Behav. 1992, 24, 134–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, D.; Willits, F.K. Environmental Attitudes and Behavior A Pennsylvania Survey. Environ. Behav. 1994, 26, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poortinga, W.; Steg, L.; Vlek, C. Values, Environmental Concern, and Environmental Behavior A Study into Household Energy Use. Environ. Behav. 2004, 36, 70–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas. Censo de Población 2012. Available online: www.ine.cl (accessed on 15 October 2015).

- Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas, Cifras Trimestrales de Empleo. 2013. Available online: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=1&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=0CB0QFjAAahUKEwiwnObZ6MTIAhWHHpAKHauMB1I&url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.ine.cl%2Fdescarga.php%3Farchivo%3D384%26codigo%3DYB7HerQb4dCBvUcB&usg=AFQjCNF362Zri14CrAEY0EWlqiZEYsNbbA&sig2=auhqbGO-kb5DcbrjgEaszA (accessed on 15 October 2015).

- Kaiser, F.G. A General Measure of Ecological Behavior. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 28, 395–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, F.G.; Doka, G.; Hofstetter, P.; Ranney, M.A. Ecological behavior and its environmental consequences: A life cycle assessment of a self-report measure. J. Environ. Psychol. 2003, 23, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H. A proposal for measuring value orientations across nations. 2003. Available online: http://www.europeansocialsurvey.org/docs/methodology/core_ess_questionnaire/ESS_core_questionnaire_human_values.pdf (accessed on 15 October 2015).

- Dunlap, R.E.; van Liere, K.D.; Mertig, A.G.; Jones, R.E. New trends in measuring environmental attitudes: Measuring endorsement of the new ecological paradigm: A revised NEP scale. J. Soc. Issues 2002, 56, 425–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gärling, T.; Fujii, S.; Garling, A.; Jakobsson, C. Moderating effects of social value orientation on determinants of proenvironmental behavior intention. J. Environ. Psychol. 2003, 23, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low SES was not considered for the purposes of this study, since it represents extreme poverty.

- Hair, J.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed; Prentice-Hall, Inc: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Schumacker, R.E.; Lomax, R.G. A Beginnerʼs Guide to Structural Equation Modeling; Psychology Press: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bill to Establish Framework for Waste Management and Extended Producer Responsibility, Submitted to Lower House on September 10, 2013. Available online: http://www.camara.cl/pley/pley_detalle.aspx?prmID=9501&prmBL=9094-12 (accessed on 15 October 2015).

© 2015 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bronfman, N.C.; Cisternas, P.C.; López-Vázquez, E.; Maza, C.D.l.; Oyanedel, J.C. Understanding Attitudes and Pro-Environmental Behaviors in a Chilean Community. Sustainability 2015, 7, 14133-14152. https://doi.org/10.3390/su71014133

Bronfman NC, Cisternas PC, López-Vázquez E, Maza CDl, Oyanedel JC. Understanding Attitudes and Pro-Environmental Behaviors in a Chilean Community. Sustainability. 2015; 7(10):14133-14152. https://doi.org/10.3390/su71014133

Chicago/Turabian StyleBronfman, Nicolás C., Pamela C. Cisternas, Esperanza López-Vázquez, Cristóbal De la Maza, and Juan Carlos Oyanedel. 2015. "Understanding Attitudes and Pro-Environmental Behaviors in a Chilean Community" Sustainability 7, no. 10: 14133-14152. https://doi.org/10.3390/su71014133

APA StyleBronfman, N. C., Cisternas, P. C., López-Vázquez, E., Maza, C. D. l., & Oyanedel, J. C. (2015). Understanding Attitudes and Pro-Environmental Behaviors in a Chilean Community. Sustainability, 7(10), 14133-14152. https://doi.org/10.3390/su71014133