Do Dietary Changes Increase the Propensity of Food Riots? An Exploratory Study of Changing Consumption Patterns and the Inclination to Engage in Food-Related Protests

Abstract

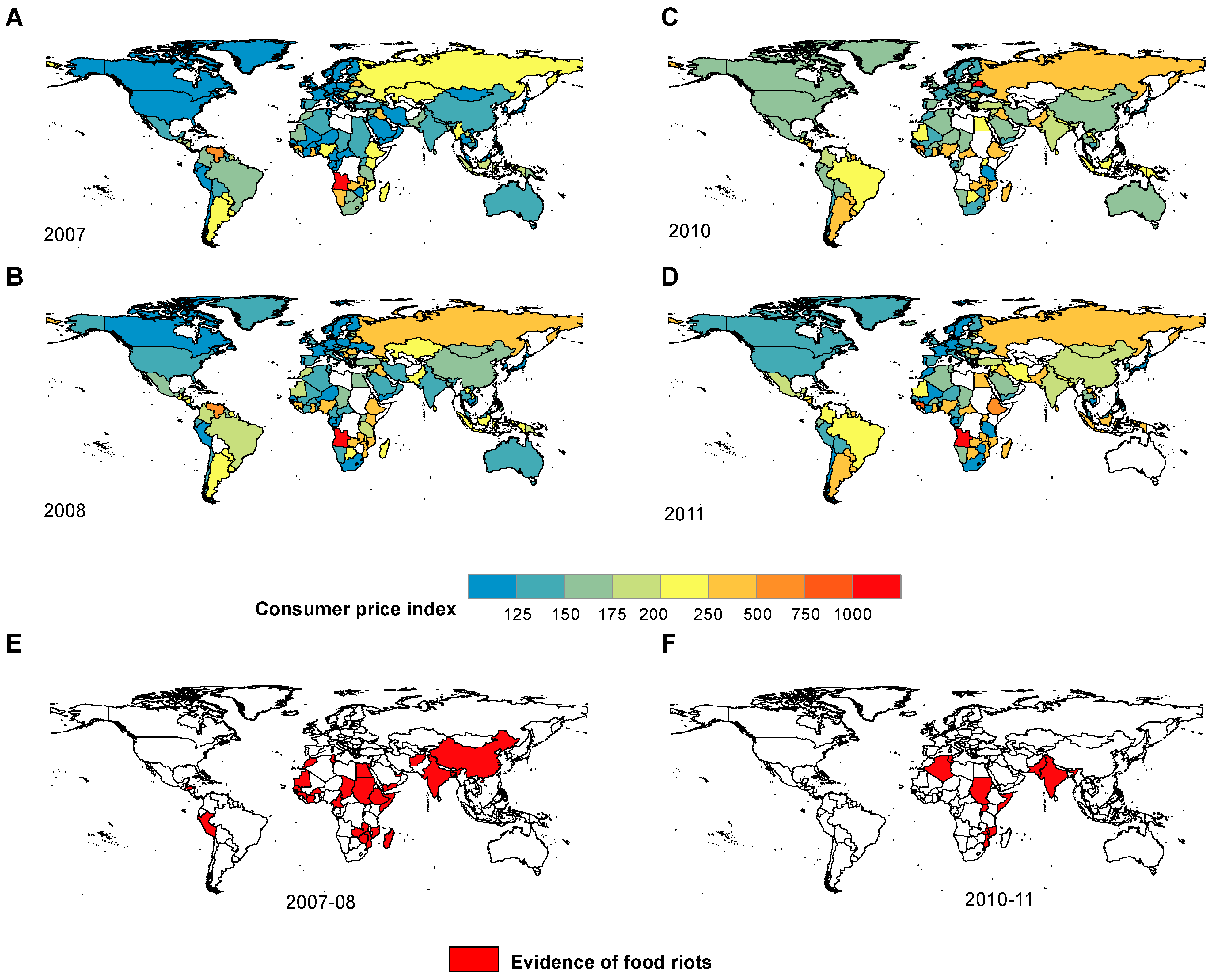

:1. Introduction

- (1)

- the relationship between household demographic characteristics and reported intent to riot due to future food price rises;

- (2)

- the relationships between diets/dietary changes and reported intent to riot due to future food price rises.

Theory/Literature

2. Methodology

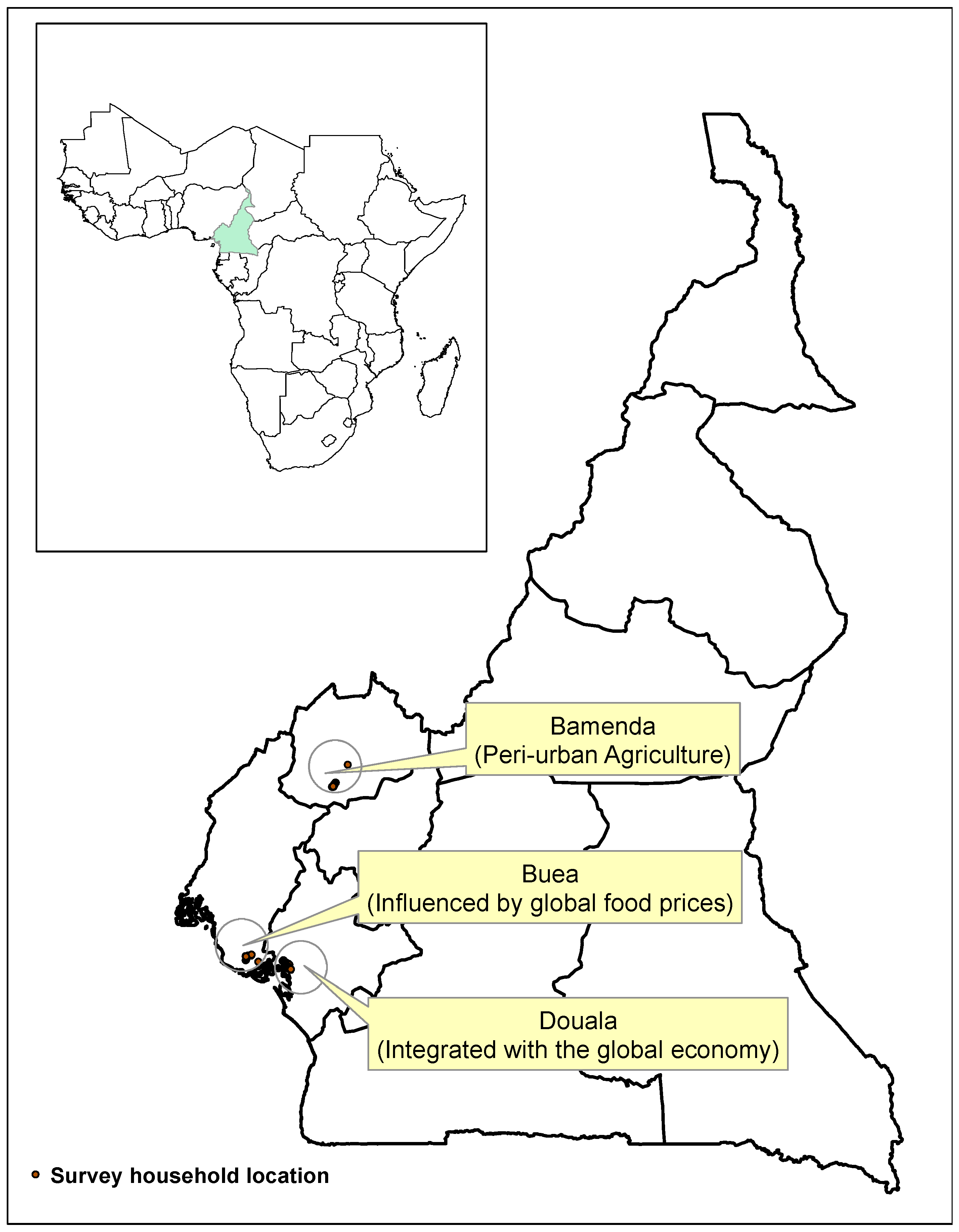

2.1. Selection of Cities

2.2. Sampling

2.3. Survey Design

- Household demographics including age, education levels, indicators of relative wealth, and levels of social, economic, and political satisfaction.

- Household food preference (this was done without any predetermined list of food allowing us to collect qualitative data on the range of food preferences amongst respondents.)

- A 24 h dietary diversity survey commonly used in food security measurement [32,33].

- ○

- The survey asks if people have eaten (yes/no) from the 12 food groups listed below. The resultant household dietary diversity score (HDDS) were values between 0 and 12, which represented the total number of food groups consumed by members of the household within the last 24 h. The food categories are:

- Cereals (bread, rice noodles, biscuits or foods made from millet, sorghum, maize, rice, wheat)

- Tuber or roots (potatoes, yams, manioc, cassava)

- Vegetables

- Fruits

- Meat (beef, pork, lamb, goat, rabbit, game, chicken, duck, other birds, offal)

- Eggs

- Fish/shellfish

- Pulses/legumes/nuts (beans, peas, lentils, or other nuts)

- Milk (and milk products)

- Oil/fat (foods made with oil, fat, or butter)

- Sugar/ honey

- Condiments, coffee and tea

- Using 24 h recall as the basis, we asked if the consumption of each of the 12 food groups had increased, stayed the same or decreased since childhood (henceforth referred to as “over time”).

- Building on the same food groups identified above, we asked how households reacted to food prices changes in the past. In particular, we asked whether households decreased, maintain the same quantity or increased the quantities of these specific foods during the 2008 price shock. We also followed up with an open-ended request for more specific examples of dietary change and the reasons behind the changes.

- We asked the participants to tell us whether or not they would engage in some kind of political protest in the event of another food price rise in Cameroon. We then went further to ask the type of political action they would take including: signing a petition, join a boycott, attending a peaceful manifestation or join a strike action. Finally, to explore which places (cities/towns) in Cameroon were thought to be more prone to riots and why, we asked the participants to tell us where they thought people would most likely engage in a food riot/protest and why they believed those people/places would be most reactive.

2.4. Preparation of Variables

| Survey Questions | Wealth Ranking | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| On a scale from 1 to 10, where would you place the current living standards of your household? Where 1 is “very poor” and 10 is “very wealthy” | How do you think your living standard compares with that found in the average home in your city? | ||||

| Actual score | Adjusted score | Actual score | Adjusted score | Total score (sum of two adjusted scores) | Income level |

| 1–3 | 1 | Far below average & below average | 1 | 2 & 3 | Low income |

| 4–6 | 2 | Average | 2 | 4 & 5 | Middle income |

| 7–10 | 3 | Above average and far above average | 3 | 6 | Upper middle income |

2.5. Data Analysis through Descriptive Statistics and Logistic Regression Model

| City | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bamenda (Low Global Integration) | Buea (Medium Global Integration) | Douala (High Global Integration) | |||||

| % | Mean | % | Mean | % | Mean | ||

| Wealth Ranking | Low Income | 34.0 | 13.0 | 38.0 | |||

| Middle Income | 59.0 | 53.0 | 54.0 | ||||

| Upper Middle Income | 7.0 | 34.0 | 8.0 | ||||

| Weighted Educational Index | 0.47 | 0.54 | 0.47 | ||||

| Total Household Expenditure (US$) | 508.99 | 1140.23 | 514.55 | ||||

| Household Dietary Diversity Score Ranking | Low HDDS 1–4 | 30.0 | 9.0 | 11.0 | |||

| Medium HDDS 5–8 | 51.0 | 50.0 | 61.0 | ||||

| High HDDS 9–12 | 19.0 | 41.0 | 28.0 | ||||

| Gender of Respondent | Female | 30.0 | 53.0 | 50.0 | |||

| Male | 70.0 | 47.0 | 50.0 | ||||

| Age Range of Respondent | Under 18 years old | 9.2 | 5.2 | 8.2 | |||

| 18–24 years old | 16.3 | 8.2 | 17.3 | ||||

| 25–34 years old | 27.6 | 34.0 | 33.7 | ||||

| 35–44 years old | 23.5 | 28.9 | 26.5 | ||||

| 45–54 years old | 12.2 | 18.6 | 9.2 | ||||

| 55–64 years old | 5.1 | 3.1 | 4.1 | ||||

| 65 years or older | 6.1 | 2.1 | 1.0 | ||||

| Work Status of Respondent | Working full-time | 68.8 | 68.6 | 66.7 | |||

| Working part-time or casual | 6.3 | 17.6 | 13.6 | ||||

| Not working and looking | 8.3 | 3.9 | 8.6 | ||||

| Not working and not looking | 16.7 | 9.8 | 9.9 | ||||

| Other | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.2 | ||||

3. Results

3.1. Household Demographic Characteristics and Reported Intent to Riot Due to Future Food Price Rises

| Variables | Subgroup | Percentage (number) of respondent who answered “yes” to question “would you riot in the case of a food price rise?” |

|---|---|---|

| City * | Bamenda | 65.0% (65) |

| Buea | 61.0% (61) | |

| Douala | 86.0% (86) | |

| Wealth Ranking | Low Income | 76.5% (65) |

| Middle income | 68.1% (113) | |

| Upper Middle Income | 69.4% (34) | |

| Gender of Participant | Female | 74.4% (99) |

| Male | 67.7% (113) | |

| Age range of Participant | Under 18 years old | 59.1% (13) |

| 18–24 years old | 75.6% (31) | |

| 25–34 years old | 68.8% (64) | |

| 35–44 years old | 76.6% (59) | |

| 45–54 years old | 74.4% (29) | |

| 55–64 years old | 50.0% (6) | |

| 65 years or older | 66.7% (6) | |

| Work status of Participant | Working full-time | 78.7% (96) |

| Working part-time or casual | 65.2% (15) | |

| Not working and looking | 92.3% (12) | |

| Not working and not looking | 66.7% (14) | |

| Other | 0.0 | |

| Highest level of education of Participant | No formal schooling | 50.0% (3) |

| Some Primary | 63.6% (7) | |

| Primary completed Junior or Senior | 68.2% (30) | |

| Some high school | 78.9% (45) | |

| High school completed | 75.4% (43) | |

| Post secondary qualifications not university diploma, or degree from college | 85.2% (23) | |

| Some university | 76.5% (13) | |

| University completed | 54.0% (27) | |

| Post-graduate MA or MSc or PhD | 73.7% (14) | |

| How happy are you about the current political situation is in the country? * | Very happy | 100.0% (9) |

| Happy | 84.1% (37) | |

| Neither happy nor unhappy | 56.6% (30) | |

| Unhappy | 69.4% (84) | |

| Very unhappy | 75.9% (44) |

“Yaounde (national capital), Douala, Bamenda because these cities are witnessing an increase in population yet there are no job opportunities and (there has been) a very rapid increase in foodstuff prices.”

“Douala, Yaounde, Bafoussam because most of their food items are being imported.”

“Douala because it is the economic capital and Bamenda because it is the opposition party capital.”

“(The) Cameroonian government hate(s) peace so if you don’t use the hard way (protest), you don’t get what you want.”

“The government does not take care of farmers (or) farm to market road networks, and there are heavy taxes on farm produce.”

3.2. Relationships between Diets/Dietary Changes and Reported Intent to Riot Due to Future Food Price Rises

| M1: Propensity to Riot Due to Increased Consumption Levels | M2: Propensity to Riot Due to Decreased Consumption Levels | M3: Propensity to Riot without Changing Consumption Levels | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Coefficient & Standard Error | Variables | Coefficient & Standard Error | Variables | Coefficient & Standard Error |

| Weighted Education Index | −1.914 * (1.002) | Total Expenditure (US$) | −0.000148 * (8.89 × 10−5) | Weighted Education Index | −3.239 ** (1.419) |

| Increase in consumption of roots due to price increase (1 = yes, 0 = no) | 0.854 * (0.461) | Weighted Education Index | −2.791 * (1.460) | No change in consumption of meat due to price increase (1 = yes, 0 = no) | −0.934 * (0.558) |

| Increase in consumption of vegetables due to price increase (1 = yes, 0 = no) | −0.898 * (0.500) | Decrease in consumption of pulses due to price increase (1 = yes, 0 = no) | −1.493 ** (0.651) | No change in consumption of eggs due to price increase (1 = yes, 0 = no) | 1.408 *** (0.537) |

| Increase in consumption of eggs due to price increase (1 = yes, 0 = no) | −1.427 *** (0.480) | Decrease in consumption of other food due to price increase (1 = yes, 0 = no) | 2.069 *** (0.704) | No change in consumption of other food due to price increase (1 = yes, 0 = no) | −0.941 * (0.525) |

| Increase in consumption of oil due to price increase (1 = yes, 0 = no) | 0.986 * (0.578) | Decrease in consumption of fruits over time (1 = yes, 0 = no) | −2.024 ** (0.867) | No change in consumption of sugar over time (1 = yes, 0 = no) | −1.278 ** (0.519) |

| Increase in consumption of sugar due to price increase (1 = yes, 0 = no) | 1.226 ** (0.606) | Decrease in consumption of meat over time (1 = yes, 0 = no) | 1.847 ** (0.739) | No change in consumption of other foods over time (1 = yes, 0 = no) | 0.969 * (0.587) |

| Increase in consumption of other food due to price increase (1 = yes, 0 = no) | −1.297 ** (0.536) | Constant | 2.317 ** (1.096) | Constant | 3.590 *** (1.063) |

| Increase in consumption of roots over time (1 = yes, 0 = no) | −0.899 ** (0.433) | Number of observations | 202 | Number of observations | 202 |

| Constant | 1.934 ** (0.817) | Pseudo R2 | 0.2211 | Pseudo R2 | 0.1840 |

| Number of observations | 270 | ||||

| Pseudo R2 | 0.1684 | ||||

- Based on the 12 food groups that we used to capture dietary trends, the logit model shows that those who had increased their consumption of roots had a higher propensity to riot than those who had not increased their consumption of roots.

- The model also indicates that those who eat more egg even when prices are high had a lower propensity to riot while those who reported no change in consumption of eggs due to price rise had a higher propensity to riot.

- Those who increased oil consumption had a significantly higher propensity to riot.

- Those who increased their consumption of sugar had a significantly greater propensity to riot, while those who did not change their consumption of sugar had significantly lower propensity to riot.

- Those who decreased their consumption of pulses had lower propensity to riot.

- Households who reported a decrease in the consumption of meat were more likely to indicate a willingness to riot.

- The model also highlights that those who decreased their fruit intake had a lower propensity to riot.

- Finally, the model indicates that there is a relationship between consumption changes in tea, coffee and condiments and riots. Specifically, model results show that those who can afford to increase their consumption of other items such as tea, coffee and condiments are less likely to be dissatisfied and less likely to state that they intend to engage in riots as opposed to those who decreased or maintained their consumption of these items.

“What do you expect of someone who eats only rice, rice, rice? Let prices drop for us to start eating at least different forms of food my diet is poor.”

“I am constipated because the balanced diet I used to have before is not more there. Bread every day is too much. I want to eat my normal food so I need that prices should drop.”

“When things are difficult, I look for different types of food like rice as food to fill the food gaps.”

“Even though where I am from (ethnicity) we eat mostly fufu (pounded cocoyams) now in my house we eat mostly rice or corn. You can grind them and eat with ngama-ngama (vegetable relish). Corn can be cooked with beans to make cornchaff or you can make pap (warm porridge of fresh corn), while rice you can make jelloff or even njanga rice (fried rice with crayfish).”

4. Discussion

- (1)

- A huge proportion (70.7%) of our participants said they would riot if prices rose again, representing people from all cities, age groups, gender, marital status, socio-economic class, and educational levels.

- (2)

- When confronted with a food price increase we noted that households in Cameroon’s major cities are more likely to riot than the citizens of cities where people were less reliant on markets for food provisioning.

- (3)

- The impact of diets on people’s propensity to riots varies from one food group to the other when we look at the quantitative data, although the qualitative data from surveys and focus groups suggest a prevalent cereal based diet, which could shape propensity to riot.

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Berazneva, J.; Lee, D.R. Explaining the African food riots of 2007–2008: An empirical analysis. Food Policy 2013, 39, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bush, R. Food riots: Poverty, power and protest. J. Agrar. Chang. 2010, 10, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagi, M.; Bertrand, K.Z.; Bar-Yam, Y. The food crises and political instability in North Africa and the Middle East, 2011. Available online: http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1910031 (accessed on 17 October 2015).

- Sneyd, L.Q.; Legwegoh, A.; Fraser, E.D. Food riots: Media perspectives on the causes of food protest in Africa. Food Secur. 2013, 5, 485–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrix, C.S.; Haggard, S. Global food prices, regime type, and urban unrest in the developing world. J. Peace Res. 2015, 52, 143–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, T.G. Feeding unrest disentangling the causal relationship between food price shocks and sociopolitical conflict in urban Africa. J. Peace Res. 2014, 51, 679–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natalini, D.; Jones, A.W.; Bravo, G. Quantitative assessment of political fragility indices and food prices as indicators of food riots in countries. Sustainability 2015, 7, 4360–4385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinkman, H.; de Pee, S.; Sanogo, I.; Subran, L.; Bloem, M. High food prices and the global financial crisis have reduced access to nutritious food and worsened nutritional status and health. J. Nutr. 2010, 140, 1535–1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hillocks, R. Addressing the yield gap in sub-saharan Africa. Outlook Agric. 2014, 43, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakotoarisoa, M.; Iafrate, M.; Paschali, M. Why Has Africa Become A Net Food Importer Explaining Africa Agricultural and Food Trade Deficits; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- FAOSTAT. Consumer prices, food indices. In FAOSTAT; Food And Agriculture Organization of The United Nations Statistics Division: Rome, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- The World Bank Group. Food riot radar. Available online: http://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/poverty/food-price-crisis-observatory-4 (accessed on 13 July 2014).

- Grote, U. Can we improve global food security? A socio-economic and political perspective. Food Secur. 2014, 6, 187–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstone, J.A. The comparative and historical study of revolutions. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1982, 8, 187–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstone, J.A. Revolution and Rebellion in the Early Modern World; University of Carlifornia Press: Oakland, CA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstone, J.A. Toward a fourth generation of revolutionary theory. Annu. Rev. Political Sci. 2001, 4, 139–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstone, J.A. Comparative historical analysis and knowledge accumulation in the study of revolutions. In Comparative Historical Analysis in the Social; Mahoney, J., Rueschemeyer, D., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2003; pp. 41–90. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstone, J.A. Understanding the revolutions of 2011: Weakness and resilience in Middle Eastern autocracies. Foreign Aff. 2011, 90, 8–16. [Google Scholar]

- Padmanabhan, S.Y. The great bengal famine. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 1973, 11, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, P.; Braun, J.V.; Yohannes, Y. Famine in Ethiopia: Policy Implications of Coping Failure at National and Household Levels; International Food Policy Research Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 1992; Volume 29. [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien, T. Food riots as representations of insecurity: Examining the relationship between contentious politics and human security. Confl. Secur. Dev. 2012, 12, 31–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bentley, A. Eating for Victory: Food Rationing and the Politics; University of Illinois Press: Champain, IL, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Frank, D. Housewives, socialists, and the politics of food: The 1917 new york cost-of-living protests. Fem. Stud. 1985, 11, 255–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinmore, G. Italians Spurn Pasta in Price Protest. Financial Times. 14 September 2007. Available online: http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/3167ab08–625a-11dc-bdf6–0000779fd2ac.html?from=food_multimedia (accessed on 17 October 2015).

- García-Salazar, J.A.; Skaggs, R.; Crawford, T.L. Procampo, the Mexican corn market, and mexican food security. Food Secur. 2011, 3, 383–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, R. Food riots. Int. Encycl. Revolut. Protest. 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lévi-Strauss, C. The culinary triangle. In Food Culture: A Reader; Routledge: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Howe, K.R. Mixed methods, triangulation, and causal explanation. J. Mixed Methods Res. 2012, 6, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrance, H. Triangulation, respondent validation, and democratic participation in mixed methods research. J. Mixed Methods Res. 2012, 6, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN-Habitat. Cameroon un-habitat data. In Download UN-Habitat Data Collections; UN Habitat: Nairobi, Kenya, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bopda, A.P.; Awono, L. Institutional development of urban agriculture—An ongoing history of yaoundé. In African Urban Harvest; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, G.; Berardo, A. Proxy measures of household food consumption for food security assessment and surveillance: Comparison of the household dietary diversity and food consumption. Public Health Nutr. 2010, 13, 2010–2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swindale, A.; Bilinsky, P. Household Dietary Diversity Score (hdds) for Measurement of Household Food Access: Indicator Guide; Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance III Project (FANTA): Washington, DC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- KC, K.B. Combining Socio-Economic and Spatial Methodologies in Rural Resources and Livelihood Development: A Case from Mountains of Nepal; Margraf: Chiampo, Italy, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows; IBM Corp.: Armonk, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software, StataCorp LP: College Station, TX, USA, 2013.

- Researchware Inc. Hyperresearch 3.7.2, Software; ResearchWare, Inc.: Randolph, MA, USA, 2015. Available online: http://www.researchware.com/products/hyperresearch.html (accessed on 17 October 2015).

- Amin, J.A. Understanding the protest of February 2008 in Cameroon. Africa Today 2012, 58, 20–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngwane, G. Opposition politics and electoral democracy in Cameroon, 1992–2007. Afr. Dev. 2015, 39, 103–116. [Google Scholar]

- Nyamnjoh, F.B. Cameroon: Over twelve years of cosmetic democracy. News Nord. Afr. Inst. 2002, 3, 5–8. [Google Scholar]

- Demarest, L. Food price rises and political instability: Problematizing a complex relationship. Eur. J. Dev. Res. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, N.; Kalita, D. Moral economy in a global era: The politics of provisions during contemporary food price spikes. J. Peasant Stud. 2014, 41, 815–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, E.D. Travelling in antique lands: Using past famines to develop an adaptability/resilience framework to identify food systems vulnerable to climate change. Clim. Chang. 2007, 83, 495–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homer-Dixon, T. Strategies for studying causation in complex ecological-political systems. J. Environ. Dev. 1996, 5, 132–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raleigh, C.; Choi, H.J.; Kniveton, D. The devil is in the details: An investigation of the relationships between conflict, food price and climate across Africa. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2015, 32, 187–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moseley, W.G.; Carney, J.; Becker, L. Neoliberal policy, rural livelihoods, and urban food security in West Africa: A comparative study of the Gambia, côte d’ivoire, and mali. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 5774–5779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naseem, A.; Mhlanga, S.; Diagne, A.; Adegbola, P.Y.; Midingoyi, G.S.-K. Economic analysis of consumer choices based on rice attributes in the food markets of West Africa—The case of benin. Food Secur. 2013, 5, 575–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, K.; Dieng, I.; Toure, A.A.; Somado, E.A.; Wopereis, M.C. Rice yield growth analysis for 24 African countries over 1960–2012. Glob. Food Secur. 2015, 5, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2015 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Legwegoh, A.F.; Fraser, E.D.G.; KC, K.B.; Antwi-Agyei, P. Do Dietary Changes Increase the Propensity of Food Riots? An Exploratory Study of Changing Consumption Patterns and the Inclination to Engage in Food-Related Protests. Sustainability 2015, 7, 14112-14132. https://doi.org/10.3390/su71014112

Legwegoh AF, Fraser EDG, KC KB, Antwi-Agyei P. Do Dietary Changes Increase the Propensity of Food Riots? An Exploratory Study of Changing Consumption Patterns and the Inclination to Engage in Food-Related Protests. Sustainability. 2015; 7(10):14112-14132. https://doi.org/10.3390/su71014112

Chicago/Turabian StyleLegwegoh, Alexander F., Evan D. G. Fraser, Krishna Bahadur KC, and Philip Antwi-Agyei. 2015. "Do Dietary Changes Increase the Propensity of Food Riots? An Exploratory Study of Changing Consumption Patterns and the Inclination to Engage in Food-Related Protests" Sustainability 7, no. 10: 14112-14132. https://doi.org/10.3390/su71014112

APA StyleLegwegoh, A. F., Fraser, E. D. G., KC, K. B., & Antwi-Agyei, P. (2015). Do Dietary Changes Increase the Propensity of Food Riots? An Exploratory Study of Changing Consumption Patterns and the Inclination to Engage in Food-Related Protests. Sustainability, 7(10), 14112-14132. https://doi.org/10.3390/su71014112