This section profiles seven alternative ESD communications that challenge prevailing thoughts about the normative concept of sustainability, and its association with development. These initiatives were chosen for their well-reasoned arguments in favor of potentialities and possibilities provided by stretching and expanding one’s thinking about the unsustainability of the current tract of humanity. They individually and collectively tried to address how this untenable situation is aggravated by communications around the normative concept of sustainability (and development), each paying sharp attention to the significant role of educators. Their power and influence is paramount relative to a sustainable future. Communications about sustainability will profoundly shape future educational initiatives about sustaining life on the planet.

2.1. Sustainable Contraction: David Selby

“Recognizing there are alternative autopoetic (self-organizing, communitarian) renditions of ‘development’ against the dominant allopoetic (externally imposed or neocolonial) understandings of the term” ([

8], p. 41), Selby pushes back against several key ESD communication messages. First, he believes the ESD “agenda is built upon the idea that the path to sustainability lies with a combination of better management, more technological efficiency, and responsible citizenship (usually inferring citizenship that does not overly rock the boat of ‘business as usual’ production and consumption” ([

8], p. 37). He maintains that people embracing this approach, despite their best intentions, are actually “deeply complicit in a growth paradigm that is destroying both ecosphere and ethnosphere” ([

8], p. 36). Ethnosphere is defined as “the sum total of all thoughts and intuitions, myths and beliefs, ideas and inspirations brought into being by human imagination since the dawn of consciousness” ([

9], p. 2).

Second, Selby [

10] claims that sustainable development calls for the conservation of development and not the conservation of nature. Sustainable development fails to advocate for reduction in material standards of living (consumerism) or a slow down of the accumulation dynamics. He claims that the result of this message is that people call for alternatives

within development instead of alternatives

to development.

Third, Selby [

11] takes issue with the term global warming, suggesting instead, global heating. To warm up means to give off heat that is discernible by human senses (still touchable), while to heat up means something gets hot (becomes untouchable). In a counter argument, he claims the term

global heating helps avoid the palliative effect of the euphemism of getting warm. The notion of

global warming is too weak because it conveys the impression of relieving or lessening the warmth (palliative), but not curing, mitigating or alleviating the hot pain.

Fourth, and most powerfully, Selby [

8,

11] faults the mainstream approach to ESD (shaped by UNESCO’s [

3] conceptualization) as inadequately dealing with fear, denial and uncertainty. The main thrust of his argument is that humans have “a sleepwalked attachment to a distorted [materialistic and growth-oriented] value system,” ([

8], p. 38) and are consequently walking around with an

eyes wide shut syndrome, a blind pattern of living. Quoting McIntosh [

12], Selby [

8] describes our current times as a “ubiquitous quasi-hypnotic condition ... a near universal state of denial, close to collective amnesia [the inability or refusal to experience pain]” ([

12], p. 85). Coupling this sleepwalking with that fact that humanity is living in a dark age, Selby asserts that ESD’s “failure to engage with the disorientation of darkness” ([

8], p. 41) exempts people from

knowing in the darkness, which in turn compounds their denial and exacerbates their fears. Both can result in inertia, avoidance of truth and uncritical acceptance of sustainable development.

Fifth, in an eye-opening (pun intended) push-back communication, Selby [

11] advocates focusing on strong notions of sustainable in concert with taking development right out of the equation, replacing it with

contraction (and attendant concepts of moderation, restitution and restoration) [

8,

11]. Selby [

11] pioneers the idea of

sustainable contraction, believing this is a more realistic educational response to the global heating crisis manifested through unsustainable development. The word

contraction has two meanings. It can mean to become narrower or it can mean to draw together, to come to an agreement [

13]. Presuming both, Selby [

11] views sustainable contraction as a softer and more ecological concept than development. He envisions the sustainable contraction approach as a “sustainable retreat” ([

8], p. 41) leading to a future state of “sustainable moderation” ([

8], p. 41). In effect, a retreat would lead to contraction, which would lead to moderation and, ultimately, to restitution and restoration.

In order to develop his argument for movement through retreat-contraction-moderation- restitution-restoration, Selby [

8] draws on several other ideas that warrant discussion. First, arguing that people can respond to unsustainable development coming from nine types of fear, he [

11] advocates for

fearlessness [

14], gained by intentionally disruptive transformative learning experiences designed to disorient learners and make then face their hidden assumptions and beliefs. People can be afraid to feel the pain the world is experiencing. They can fear feeling despair and guilt and can fear being accused of not being patriotic. People can fear looking weak or of causing others distress by making them aware of the world’s angst and their complicity. They can fear feeling powerless and ineffectual and can even fear others viewing them as morbid. Conversely, education for contraction fosters fearlessness and places people in a position of power and agency; leading to renewal, resolve and awakened consciousness.

Second, Selby [

8] balances the notion of citizen with that of denizen, someone who occupies or dwells in a

particular place or

locale. He defines denizenship as “learning for conscious occupancy and participation in a place” ([

8], p. 49). Related to this idea, Selby calls for both localization, a connection to a place, and for place attachment, an approach that assumes learning can be rooted in what is local. Connecting to a place, and learning to live and learn within that locale, are inherent in sustainable contraction (see next).

Third, Selby [

8] poignantly recognizes that humans may not be able to flourish in the event of climate change so adverse that zones of inhabitable earth are created, forcing people to split apart and gravitate to southern or northern livable zones. In response to the real possibility of the human civilization retracting to Northern and Southern “zones of habitability” ([

8], p. 51), replete with “intergenerational alienation... and the demise of what was familiar to earlier generations” ([

8], p. 50), Selby proposes a long-term educational project of restitution and restoration, totally dependent upon the pedagogy of contraction (see McGregor [

14]). In more detail, Selby [

8] calls for both

earth restitution and restoration and

soul restitution and restoration if humanity hopes to survive. Reconciliation of earth and soul is required if humanity is to heal against a very plausible dystopian backdrop. Dystopia is a real or imagined society where the conditions of life and everything else are very bad. Those concerned with dystopian scenarios strive to explore the concept of humans individually and collectively coping, or not, with life conditions that have progressed in a downward spiral far more rapidly than they were prepared to handle.

As a final push back, Selby [

10] challenges educating

for anything, calling instead for other forms of education, perhaps sustainable education. He notes that if we should be educating

for anything, it should be

for ephemerality (lasting for a short time),

for elusiveness (escaping notice) and

for ineffability (too great to be described in words). Educating for these aspects of living in a consumer society mitigates people’s propensity to consume in unsustainable ways. Respectively, people would appreciate that things do not last forever, and that many of the power nuances of the current global context do escape their notice and never appear on their radar. Because of the absence of these layers of consuming, people remain unable to clearly articulate their roles and accountability to themselves, others and the Earth. The import of not acting responsibly is simply too great to put into words. Sustainable contraction requires that people be taught to deal with ephemerality, elusiveness and ineffability.

2.2. Unlearn Unsustainability: Arjen Wals

Wals’ [

15] most intriguing counter-communication is that people have to “unlearn unsustainability” instead of being educated

for sustainability. Learning our way out of unsustainability would entail an emancipatory approach to learning rather than the conventional instrumental approach. Emancipatory learning respects (a) hybridity (fusion and crisscrossing); (b) synergy; (c) blurring of boundaries; and, (d) permeable boundaries in the form of openness between generations, cultures, institutions, sectors and so on. Educators are encouraged to (e) help students reach tipping points wherein their thinking is pushed over the edge to make sure their mind is unfrozen. This necessitates (f) creating internal doubt and push back to ensure mind shifts (akin to Selby’s [

8] education for ephemerality, elusiveness and ineffability).

Even more challenging, Wals [

15] argues that in order to unlearn unsustainability, educators have to ensure students experience

gestaltswitching. Gestalt means mind set, with Wals calling for integrative switching back and forth between five different mindsets (gestalts): trans-cultural, trans-spatial, trans-discipline, trans-temporal and trans-human (imagine the world from the perspective of non-humans). He claims that with social cohesion (group chemistry amongst diverse learners), students are better able to gestaltswitch. The plurality and heterogeneity of a collection of diverse learners enables “transformative disruptions to emerge” ([

15], p. 23), meaning people are able to gestaltshift to a new way of seeing things or of being (akin to Kelly’s [

16] envisioned paradigm shift). If one has unlearned unsustainability, one has gained “

sustainability competence [which] refers to one’s ability to respond to a sustainability challenge with all these Gestalts in mind and to consider the challenge from a range of vantage points” ([

15], p. 24).

Finally, drawing on Siemens’ [

17] learning ecology concept, Wals [

15] explains that unlearning unsustainability depends upon the concept of

connectivism, meaning knowledge exists in the world and in networks rather than in the heads of individuals. While a network is largely a structured process, with nodes and connectors comprising the structure, an ecology is a living organism. It influences the formation of the network itself. The health of the living ecology determines the ability of the network to emerge, flourish and grow [

17]. Hence, in order for people to unlearn unsustainability, educators have to create a learning ecology that helps people make connections, create networks and gestalt switch [

15]. Not surprisingly, the learning ecology approach integrates principles from chaos theory, network theory and complexity theory leading to a

learning configuration that ensures people see links and become connected. The learning ecology approach is concerned with “the flow and dynamics of connection creation” such that learning is viewed as a “connection-forming (network-creation) process” ([

17], p. 1).

2.3. 3D-Heuristic: Bob Jickling and Arjen Wals

Finding fault with the static nature of “frameworks for education for sustainable development”, especially that from UNESCO [

3], Jickling and Wals [

18] tender a 3D-heuristic for questioning sustainability, to better convey generation and discovery. They intend educators and other practitioners to use the heuristic to place themselves within the contemporary ESD discourse. From this positioning, people would be better able to critique their own pedagogy and educational assumptions and more critically engage with the concept of education for sustainable development. Indeed, Jickling and Wals posit that sustainable development (SD) is just one social construct of our times. They are many, many other ways to help “engage people in existential questions about the way human beings and other species live on this earth” ([

18], p. 18).

This philosophical and paradigmatic reflective tool is aptly named. Heuristic is Greek Εὑρίσκω, for to find or to discover [

13]. A heuristic is a tool that helps people learn something

by themselves. Heuristics are information-processing rules used by the brain to make decisions or reach judgments (remember, normative concepts like sustainability shape people’s reasoning processes [

2]). Heuristics reduce the complexity of judgments, leading to better decisions because people are less inclined to reproduce their biases. In an attempt to prevent people from uncritically embracing ESD, Jickling and Wals [

18] created this heuristic to help people avoid ESD cognitive biases.

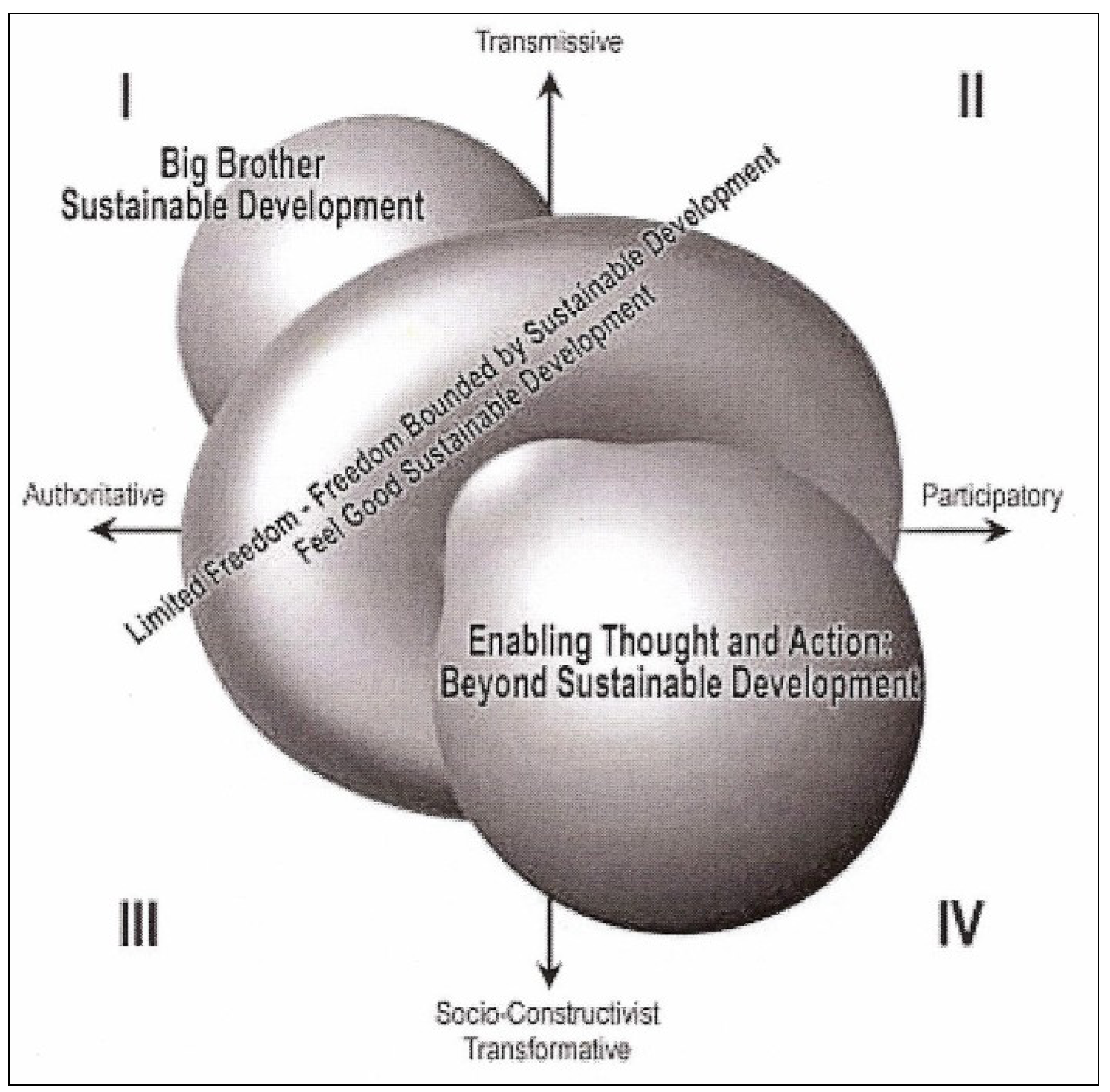

They [

18] call it a 3D-heuristic because it comprises three dimensions: (a) two conceptions of education, (b) two views of what constitutes an educated person, and at their interface on a four quadrant axis, (c) three realms of possibilities to help people focus their discussions and reflections on the relationship between SD and education (see

Figure 1). They intend their 3D-heuristic to be generative, to get people to intentionally engage with the tensions related to the sustainable development (SD) agenda and how that agenda determines what kind of education results (transmission or transformative), which in turn determines what kind of educated person is formed (compliant or participatory). They use the concept of force fields to convey the tensions inherent in the SD agenda. When these force fields collide, three possible approaches for discussing the relationship between SD and education are generated: (a) state controlled, business as usual (Big Brother SD), (b) false sense of consensus about SD, and (c) enabling people to think and act beyond SD (called three realms of possibility). Jickling and Wals [

18] want people to use their 3D-heuristic to challenge their own perspectives and questions and then reframe their approach to education, rather than blindly accept the conventional approach to ESD.

Figure 1.

Jickling and Wals’ [

18] 3D-Heuristic for Questioning Sustainability Education (used with permission).

Figure 1.

Jickling and Wals’ [

18] 3D-Heuristic for Questioning Sustainability Education (used with permission).

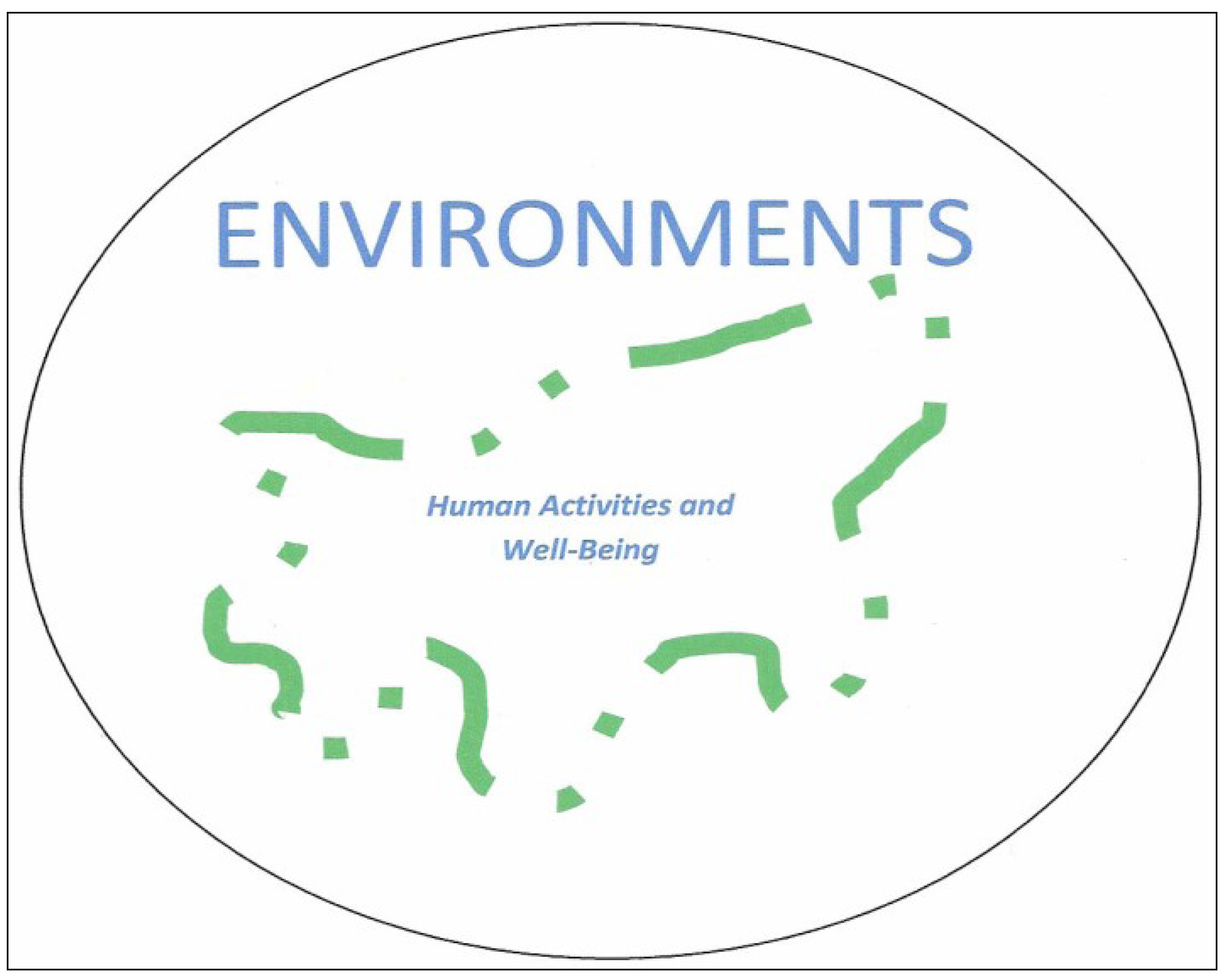

2.4. Non-Sectoral: Giddings, Hopwood, and O’Brien

Also commenting on the UNESCO [

3] conceptualization of ESD, specifically its use of the interface of three sectors, economic, social and environmental, Giddings, Hopwood, and O’Brien [

19] tender a sectorless approach, focused on the well-being of humanity. They observe that when people focus on the

sustainable part of sustainable development, they tend to use a Venn diagram and focus on political reality, separating the economy from social and environment. When people focus on the development part, they tend to use a nested cup diagram focused on material reality, positioning the economy as a subset of society and environment, dependent upon them.

Giddings

et al. [

19] advocate for an approach that places economies and societies

within environments (note the use of plural words instead of articles: a, the, an). In more detail, they push back against UNESCO’s [

3] sector approach, claiming it assumes there is

an environment,

a society and

an economy. In reality, there are multiple environments, societies and economies. And, these exist along multiple layers (micro (local), meso (regional), macro (continent) and mega (global)), all shaped by complex interactions, changing over time. This approach respects integrated, holistic, emergent, complex, and trans perspectives. With this integral logic, people can no longer assume there are dominant parts, because multiplicity and complexity presume diversity and difference (plurality). Hence, people need a new way to conceptualize and visually represent this multi-layered reality, which is different from the political reality (overlapping circles) and material reality (nested circles) [

19].

To that end, Giddings

et al. [

19] create a rudimentary representation of their idea of not separating economy from the other two sectors. Separation inflates the importance of the market, neglects human needs and reinforces the notion that the environment is

there for the taking. Instead, they focus on the activities of humans to achieve well-being, drawing a fuzzy line around this concept, and they position human well-being within environments - humans live

within environments (see

Figure 2, adapted from Giddings

et al. [

19], p. 193).

Figure 2.

Non-Sectoral Approach to Education for Sustainable Development.

Figure 2.

Non-Sectoral Approach to Education for Sustainable Development.

“The boundary between the environment and human activity is itself not neat and sharp; rather it is fuzzy. There is a constant flow of materials and energy between human activities and the environment and both constantly interact with each other” ([

19], p.193). Giddings

et al. [

19] feel this dynamic relationship is not adequately conveyed in static Venn diagrams or nested cup configurations. The fuzzy line represents the blurring of boundaries between societies and economies, merging them and opening them up to environments. The new human activity component within the fuzzy line includes material (economics), culture (society) and technology (political realities), which exist within social and cultural relationships. Human activities and well-being are surrounded with a permeable boundary, open to environments. They accept the term sustainable development, but believe achieving “it will need a shift in how humans see the world. Humans are part of a web of connections... To have long term meaning, sustainable development will require an integrated... outlook on human life and the world” ([

19], p. 195).

2.5. Frame of Mind: John Huckle

Like Selby [

10,

11], Huckle [

20] also takes issue with the over reliance on a weak model of sustainable, calling for a strong model, supported with several counter sentiments. First of all he identifies two sustainable development discourses, reformist and radical, asserting a continua of political beliefs that link and stretch between these two approaches to messaging ESD. The reformist discourse holds that we need to reform the existing industrial complex and global economy, seeking balance between economic growth and social welfare and environmental considerations. In this discourse, fostered by linear and reductionist thinking, sustainability is viewed within the growth mode. In contrast, the radical discourse calls for the democratization of the global system (social justice), supported by holistic and systemic thinking. The intent is to reshape and generate social and economic welfare within ecological limits. Dolter and Arbuthnott [

21] respectively label these approaches as green market views (reformist) and deep ecology views (radical).

Second, Huckle [

20] believes educators should view sustainability as a frame of mind rather than a state of affairs. He maintains that conventional approaches to ESD opt for a state of affairs wherein students are expected to develop positive attitudes and behaviors (scientific values), achieve specific learning outcomes and measurable sustainability indicators, and learn predetermined knowledge and skills. The state of affairs approach is grounded in the reformist discourse. Helping students live life from a

frame of mind means ESD would focus on ecological aesthetics, existential issues, spiritual values, ethics, principles, and a sense of attachment to place, all learned thorough poetic and non-manipulative arts and humanities. A frame of mind influences people’s attitudes and actions and their outlook on life. A frame of mind approach is entrenched in the radical discourse.

Third, Huckle [

20] further explains that ESD can be shaped by one of two philosophies of knowledge, that of normal science and post-normal science. From the perspective of normal science, knowledge is informed by neoliberal, neoclassical economic theory. Amongst other things, knowledge is value neutral, linear, reductionist, and rational. People learn to value individualism, equilibrium, optimization and homogeneity. Post-normal science draws on complexity economics, predicated on complexity theory (see also Wals [

15] and Ireland [

22]). Amongst other things, knowledge through this perspective is emergent, dynamic and self-organizing. Learners come to appreciate chaos and tensions, the importance of change and evolution, and they gain a deep respect for uncertainty and discontinuity. Respecting holism and synergy, they learn to search for patterns, connections and networks, and problem-solve using a plurality of perspectives and points of view. This distinction is similar to Wals’ [

15] aforementioned instrumental and emancipatory approaches to unlearning unsustainability.

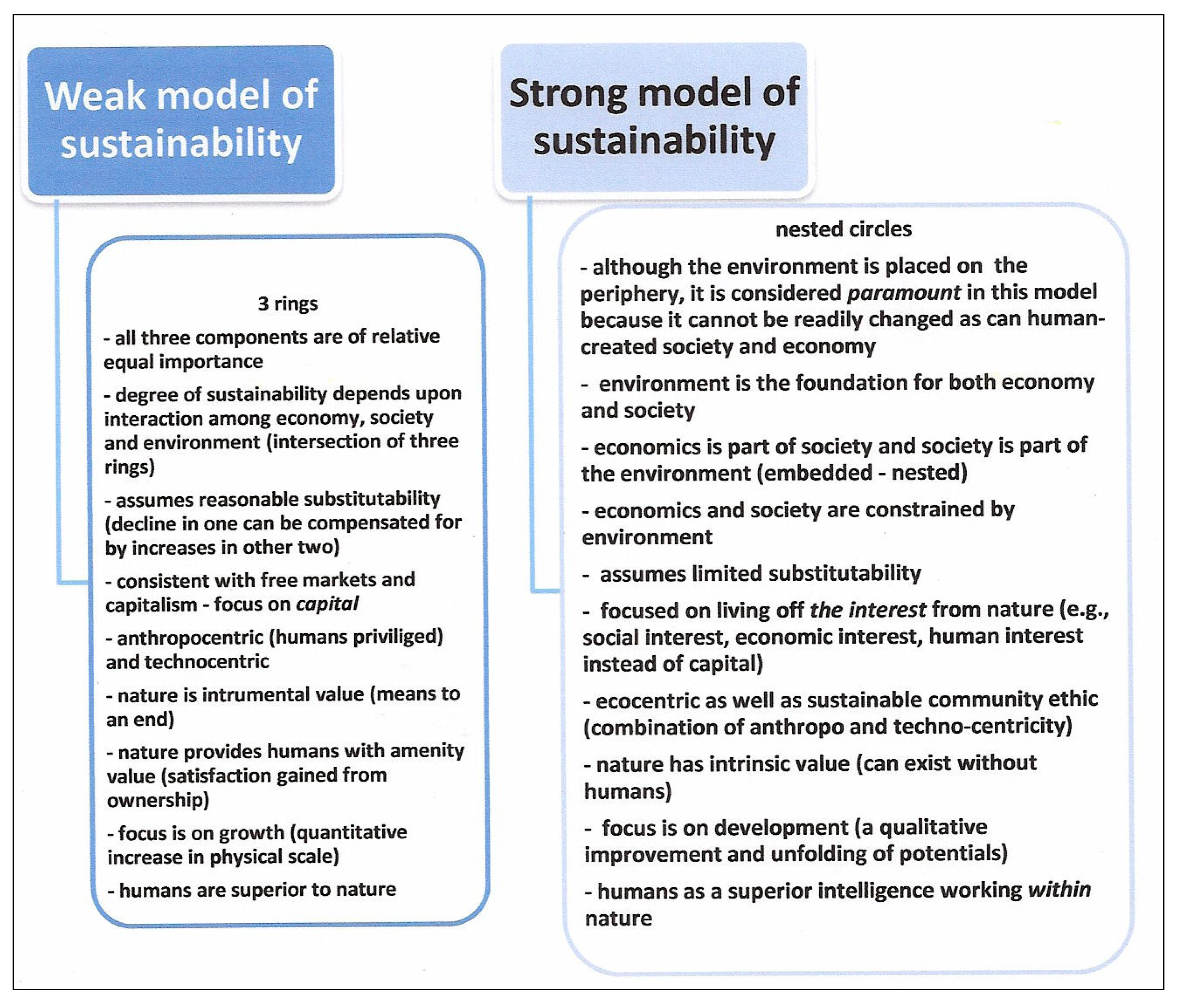

2.6. Integrative, Place-Based Paradigm Shift: Terry Kelly

Also worthy of mention is Kelly’s [

16] challenge to the notion of weak and strong models of sustainability. Unlike Selby [

10] and Huckle [

20], who challenge the concept of sustainable development, Kelly has no qualms with the notion of development, per se. His concern is with the irresponsible use of

weak notions of sustainable. Citing Morgan and Peters [

23], Kelly maintains ESD is a “long-term project of worldview transition” ([

23], p. 72) and that the requisite paradigm shift will not hold, or even take place, unless a

strong model of sustainable is employed. Kelly’s [

16] notion of weak and strong models of sustainability is set out in

Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Kelly’s [

16] Overview of Weak and Strong Models of Sustainability.

Figure 3.

Kelly’s [

16] Overview of Weak and Strong Models of Sustainability.

Kelly [

16] questions educators’ ability to get the strong model of sustainability to really take hold if people do not shift paradigms to view sustainability as focused on (a) development (a qualitative improvement and unfolding of potentials) rather than on (b) growth (a quantitative increase in physical size or scale). Otherwise, he argues, educators are only shifting deck chairs while the ship goes down instead of shifting people’s view of their place in the world, through an integrative worldview. Achieving the latter involves a different pedagogical approach, one focused on an integrative philosophy and place-based education. An integrative philosophy entails transformative, participatory and active learning. Educators would focus on whole systems thinking, the importance of context and on moral norms. They would also respect empowerment, enablement and self-organizing complex systems as major foci of curricula [

16].

Place-based education sits comfortably with Kelly’s [

16] envisioned paradigm shift. It is predicated on the worldview that humans, who are part of the interconnected earth, live in harmony with the natural world. They are a superior intelligence working

within nature (rather than dominating it); they assume that nature has intrinsic value in that it can exist without humans (see also Ireland [

22]). This intrinsicality must be respected if people are to change paradigms. Kelly maintains that bringing place into learning, and bringing learning into place, facilitates the integration required for a shift in worldviews [

16].

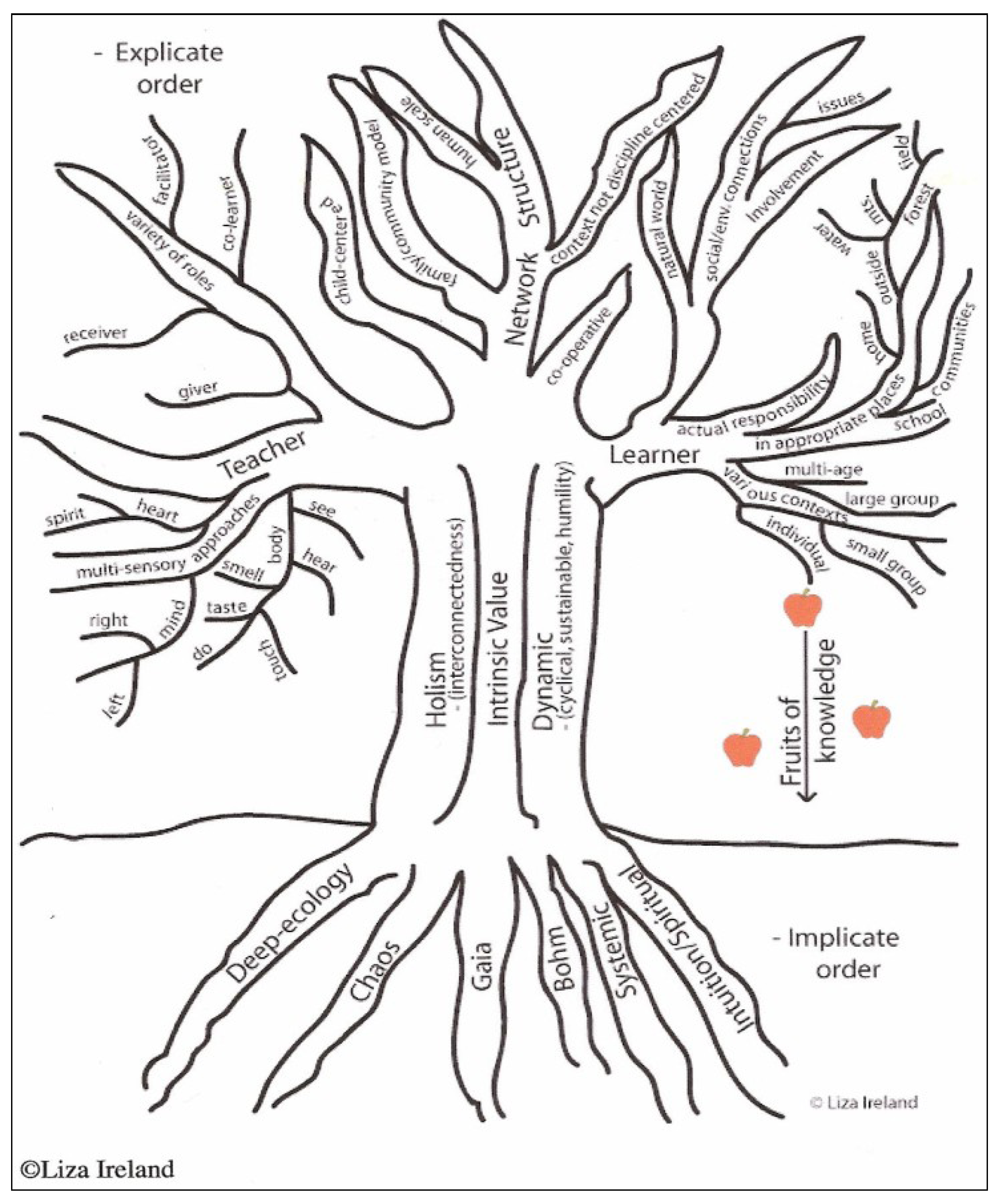

2.7. Gaia-Informed, Ecological: Liza Ireland

Wals [

15] and Selby [

24] call for quantum learning, ecological learning and endogenous learning from within. In the same spirit, Ireland [

22] created a Gaia-informed, ecological approach to

educating around sustainability (not educat

ion for sustainable development), based on notions from quantum physics, chaos theory and living systems theory (much like Selby’s [

8,

24] counter message). Ireland’s [

22] communication around the normative concept of sustainability is truly integral. Driven by the “need [for] a profoundly deeper, all-encompassing approach to education for a sustainable society” ([

22], p.71), Ireland focuses on

education for sustainability (EfS) rather than ESD. Eschewing development in favor of sustainability, she develops an ecological curriculum model using the tree as a metaphor (see

Figure 4). The crux of her counter message to conventional ESD is the necessity of an integral, holistic, ecological philosophy based in the concept of Gaia (see also Selby [

8,

24]).

Figure 4.

Liza Ireland’s [

22] Ecological and Gaia Model of Education Around Sustainability (used with permission).

Figure 4.

Liza Ireland’s [

22] Ecological and Gaia Model of Education Around Sustainability (used with permission).

As explained by Lovelock [

25,

26], the concept of Gaia presumes Earth is a living entity with a memory and a conscience. All organisms and their inorganic surroundings on Earth are closely interrelated to form a single and self-regulating (self-organizing) complex system, maintaining the conditions of life on the planet. Ireland [

22] explains that from the Gaia perspective, people are not

living off of the earth, they are part

of life. A key exemplar of this idea is the 2009 movie

Avatar, directed by James Cameron.

Regarding the ecological tree metaphor in

Figure 4, Ireland [

22] envisions the roots as the holistic, ecological paradigm and worldview underpinning her approach to educating around and for sustainability. The core of the trunk represents the intrinsic value of nature. The perimeter of the trunk (the bark) provides stability, representing the holistic and dynamic concepts of sustainability, humility, interconnectedness and iterative change. The branches and leaves stand for the pedagogical approach Ireland recommends to teach education for sustainability (EfS): mutually responsible place- and context-based learning of teacher and learners, scaffolded with a learning network structure. The fruits of knowledge fall back to the earth to nurture the roots (the worldview and paradigm), leading to implicate wisdom (called “slow knowledge” ([

22], p. 361).

To illustrate the power of this counter-message to conventional ESD, the following text will focus mainly on the root system because it provides support for the entire educational enterprise. Ireland [

22] posits that EfS requires grounding in deep-ecology, chaos, Gaia, Bohm’s intricate and explicate order, and intuition and spirituality. The concept of Gaia was explained above. Deep ecology is a current philosophy that rejects the idea of relative value (

i.e., some things are more important/superior than others) and embraces inherent and intrinsic value (the core of the tree). If something is intrinsic, it is valued for its internal essence regardless of whether it can be used for gain by others (e.g., nature) [

22].

Deep ecology assumes that humanity and all other beings are aspects of a single, unfolding, continually emerging, reality, thorough implicate (fold in) and explicate (unfold) order. At the explicate level, people tend to see things as relatively separate, but quantum physics teaches us to look for the implicate as well. At the implicate level, things are folded into a whole, and the whole is an integral (inseparable) part of everything (imagine a helical spring slinky toy). Ireland [

22] calls the hidden root system the implicate order and the visible branches and leaves (

i.e., pedagogy) the explicate order. She believes that with the right pedagogy, and with the fruits of knowledge slowly continuing to nurture the roots (the learning paradigm), learners have the chance to gain implicate wisdom. Citing Bohm [

27], Ireland explains that the future is carried as yet unfolded within the implicate order, meaning the future is ever-present (although invisible), rather than far off, in the distance.

Chaos is another concept in the root system of her ecological metaphor for EfS. Chaos means order is emerging, just not predictably. The energy play within emergent order is ripe with tensions, which hold things together as they evolve. From this perspective, Ireland [

22] explains that learning can be stable yet have constant flows of energy (causing points of instability). At these points of instability in learning, new structures and forms of order can emerge; that is, new learning can occur. Chaos theory lets educators assume that a radical shift in perceptions (perhaps entire worldviews) is happening from stability to instability, from order to disorder (order emerging), from balance to imbalance, and from beginning to becoming. This learning, which is focused on an ever present future, must teach humility (the bark of the tree). The stability and strength of learning depends upon students rejecting the idea that they are superior and more important than nature, meaning they are humble.

Finally, holism is the other key component of learning stability (the trunk); everything is connected and cannot be understood in isolation. Each individual element does its part but it does so within the context of the whole (imagine a jazz quartet). Wholes have properties that their parts do not. Holism is a celebration of the complex and a way to ensure that learners engage with as many people and perspectives as possible. They create something greater by working together than they would by working alone [

22].