1. Introduction

Three decades of forest co-management approaches have largely failed to deliver promised conservation and socio-economic benefits in many developing countries. Like participatory forest management (PFM) or community-based natural resources management approaches, co-management approaches have reached “a crisis of identity and purpose, with even the most positive examples experiencing only fleeting success due to major deficiencies” according to Dressler

et al. [

1]. The initial excitement and rhetoric have given way to a more critical consolidation phase focused on resolving theoretical and practical limitations [

2,

3,

4,

5]. Yet these participatory approaches retain strong discursive appeal, including on arguments of subsidiarity and efficiency, community empowerment, equity/inclusiveness, and productivity (ecosystem services, incomes and livelihood support), especially relative to widely failed command-and-control approaches [

2,

6,

7]. Of Africa’s 675 million hectares of forest (23% of Africa’s area) 14% is designated primarily for biodiversity conservation [

8]. Mounting anthropogenic pressures causing forest degradation and deforestation threaten forest ecosystem services and the livelihoods of 1.2 billion forest-dependent people globally. These pressures make remaining natural forest stocks in protected forests stand out and become the (relatively) new frontier for unsustainable extraction or forest conversion to other land uses, and co-management an attractive potential solution [

9,

10]. Over 25% of forested land in developing countries is under some community control [

11], a significant proportion in protected areas.

Definitions and theoretical perceptions of co-management vary, but generally involve shared rights and responsibilities over a particular resource between governments and private users/actors, including communities. Relative levels of power between government and private actors also vary from predominantly private to predominantly government run [

3,

12]. In developing countries, co-management is predominantly government driven and pre-designed, and the devolution of authority and resource rights to users is often partial [

1,

13]. Traditional definitions of co-management have been relatively static and structuralist, “emphasizing legal aspects and formal structures/institutions,” and have failed to capture “the complexity, variation and dynamic nature of contemporary systems of governance” [

3]. This article adopts a conceptualization which is less structuralist, more nuanced, function or process based, holistic and dynamic, reflecting “the assumption that co-management is a continuous problem-solving process, rather than a fixed state, involving extensive deliberation, negotiation and joint learning” [

3] (p. 65).

However, co-management is no panacea. Performance is context dependent, and it shares broader limitations of participatory approaches including community-based forest management, CBFM (in this article referring to community-driven PFM on non-reserve, common-pool forests). Critiques include homogenization of “community” and neglect of unequal power relations that fuel elite capture [

14,

15]; narrow focus on static, formal institutions while neglecting informal and adaptive ones and leadership [

5,

16]; its romanticization, bureaucratization and co-option as a tool for neoliberal reforms [

2,

17]; the “local-trap” assumption that local or single-scale interventions are innately superior to action at broader or multiple scales [

18,

19]; and ignoring the commonly low exchange value of forest resources [

5,

17,

20]. Still, protected forests have unique properties, challenges and opportunities. Land tenure is considered more secure under government control and co-management often assumed less risky than village-based CBFM. Forest reserves (FRs) tend to be extensive and therefore traverse multiple users and interests and institutional boundaries, potentially undermining holistic management. A history of dispossession of land and forest rights generally associated with FRs reduces much co-management to communication and outreach interventions (for jobs, infrastructure, and income-generating activities) meant to mend community/state relations, right previous wrongs, and engender positive attitudes towards conservation [

21]. Many governments and donor agencies use co-management to externalize conservation costs to communities, but some local communities and individuals also use co-management as a Trojan horse to reclaim historical land rights [

2,

19]. Annual expenditures for protected area management in developing countries in the mid 1990s ($695 million or $93/km

2 versus $929/km

2 for developed countries) covered only 34% of conservation needs [

22]. Ultimately, co-management challenges and potential solutions are generally known, e.g., [

6,

23,

24,

25]. Challenges increasingly lie in how to use this knowledge, including determining configurations that work in particular contexts [

3,

5,

9].

The purpose of this study is to examine challenges of bringing people back into protected forests in developing countries as a means to promote sustainable management through co-management approaches. It uses insights emerging from co-management of forest reserves in Malawi under a European Union (EU)-funded project, the Improved Forest Management for Sustainable Livelihoods Program (IFMSLP, 2006–2009, 2011–2015). The study uses multiple social science research methods, including a household survey, key informant interviews, focus groups, village discussions, field observations and secondary data collected 2009–2012 to examine how socio-ecological dynamics among diverse actors operating at multiple levels shape local co-management performance. The article focuses less on assessing co-management “success” or “failure” and more on processes and early trajectories for institutions, property rights, motivations and power relations juxtaposed against project objectives and broader social and ecological goals of co-management based on a holistic analytical framework proposed by Plummer and FitzGibbon [

26]. The study also uses the theory of reciprocal altruism in sociobiology [

4,

27] to illuminate major findings relating to individual user motivations to participation in co-management. It contributes to a nuanced understanding of co-management and recent debates on how to address the persistent gap between co-management theory/policy and practice, e.g., [

1,

4,

10]. The primary argument is that a narrow emphasis on cash incentives as the motivation for “self-interested” users to participate in co-management overlooks locally significant non-cash motivations, inflates local expectations beyond ability to deliver, and often creates perverse incentives that undermine socio-ecological goals. Findings showed modest early gains in institutions and capacity building and forest condition, but low and generally disappointing cash benefits which burdened poor communities with conservation costs and created perverse incentives to overharvest, be dependent on the project/government, and to marginalize the local poor.

Protected forests are particularly important for Malawi, a small (~120,000 km

2 of land), densely populated and rapidly growing (2.4-fold from 1987–2008) African country with 13.1 million (2008 census), predominantly rural (86%), agrarian and largely poor people [

28]. Over half (52.4%) lived under the national poverty line of $0.50/day in 2004 [

29]. Annual GNI per capita was $330 in 2010 [

30]. Nearly half of the rapidly dwindling forest stock (2.8% annual deforestation rate, 1972–1990) are in protected forests (88 forest reserves, four wildlife reserves, and five national parks covering 21% of Malawi’s land) [

31]. These protected forests are threatened by conversion to agricultural land, over-dependence (96.8% of the population) on firewood and charcoal as the primary energy source for cooking, and poverty [

32,

33]. However, Malawi’s forest co-management challenges have less to do with policy content than its implementation. The IFMSLP is Malawi’s first major forest co-management project. It expands co-management from 1,382 hectares in the 1990s [

34] to over 140,000 hectares in 12 FRs covering 15% of total FR area, starting in 2006 (

Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Improved Forest Management for Sustainable Livelihoods Program Sites.

Figure 1.

Improved Forest Management for Sustainable Livelihoods Program Sites.

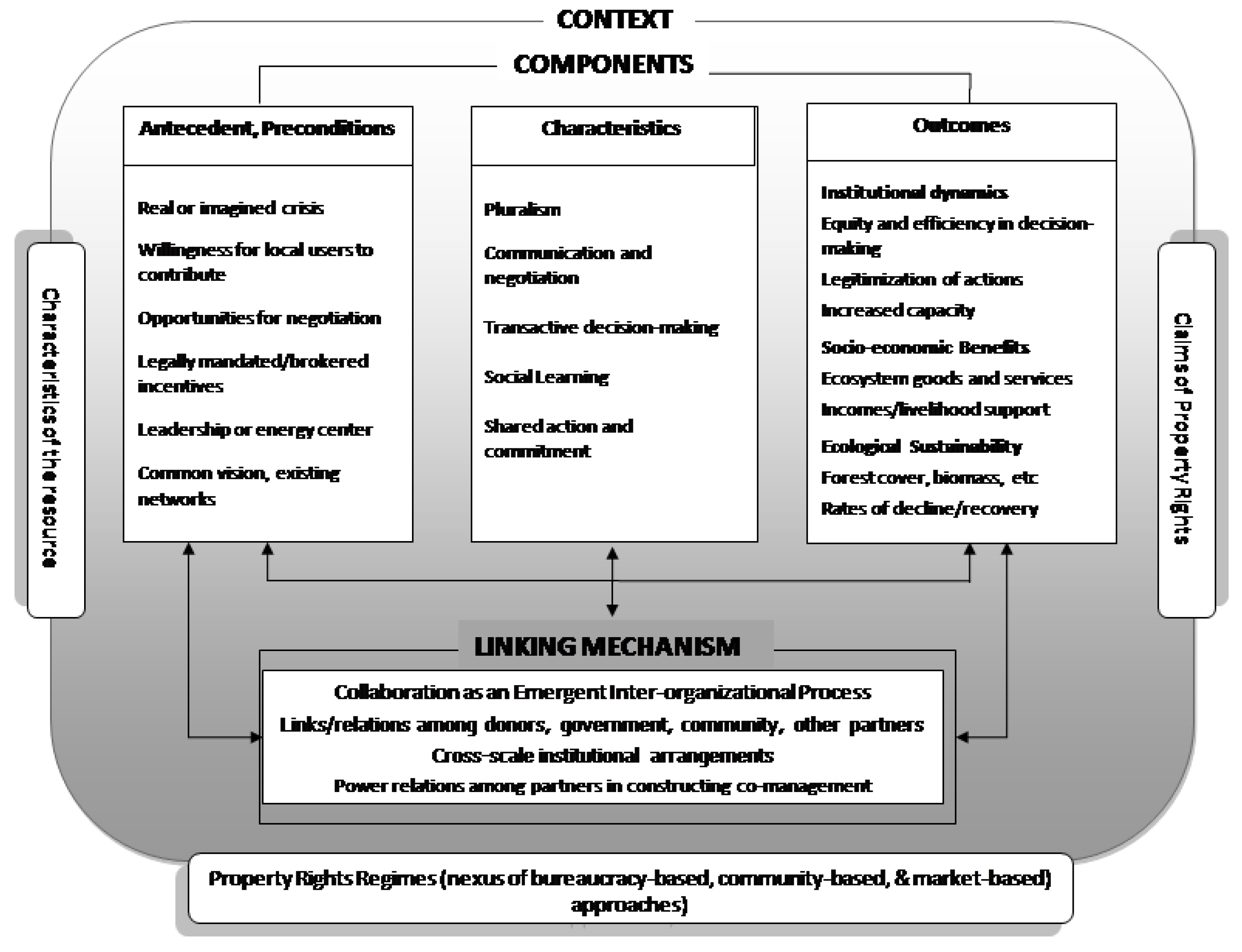

After describing the methods, this article examines nuanced conceptualizations of co-management, and explains the analytical framework and theory of reciprocal altruism. Next it frames the IFMSLP within the policy, legal and historical context. Attention next turns to functions, processes, and early trends organized under three categories: socio-ecological context, co-management components (pre-conditions, characteristics and outcomes), and inter-organization linking mechanisms (

Figure 2). Major results surrounding the main argument are discussed through the lens of reciprocal altruism and insights on opportunities and pitfalls highlighted, before concluding the article.

2. Methods

This study uses multiple research methods and analytical scales: a household survey, key informant interviews, focus groups, observation, and secondary data collected 2009–2012. The questionnaire-based household survey was conducted in July 2009 in seven villages located adjacent to Nyanja Block, the only formally approved co-management block within Ntchisi Forest Reserve, central Malawi (

Figure 1). The survey focused on the demographic, ecological and socio-economic context, participation levels, impetus and commitment for co-management, and local perceptions of co-management institutions, processes, initial outcomes and trends. Motivation for participation in co-management was captured as the respondents’ biggest initial expectation for their participation, and actual values and uses assigned to forests. Households were selected through combined random and systematic sampling, starting with seven villages selected randomly from nine participating ones, then interviewing 6–11 household heads per village (depending on size) selected systematically across a prominent transect through the village. The sample size (65 HHs, 45 male, 20 female) represented 36.1% of the population (180 households). Semi-structured interviews captured similar information, focusing on social relations among diverse co-management actors at village, block, FR (Ntchisi), district and national levels. Informants and focus groups included Department of Forestry (DoF) staff at multiple levels, project technical advisors/experts, local government officials, traditional leaders, and various local forest organization members at user-group (for firewood, timber, poles), village, FR-block, and forest reserve levels [

35]. The study also drew on secondary information, including policy documents, project and DoF reports, studies, reviews, guides and other documents, and records kept by communities. Data analysis was mostly qualitative, including descriptive contextualization. However, it also included basic descriptive statistics and limited Chi-square tests for the survey data. Use of multiple methods allowed triangulation and cross-validation of information and findings.

3. Co-Management Conceptualization, Theoretical Foundation, and Analytical Framework

The multiplicity of co-management definitions—and therefore forms—warrants choice of broad definitions that can accommodate nuance [

26]. One such definition is Yandle’s [

36] which refers to co-management as “a spectrum of institutional arrangements in which co-management responsibilities are shared between the users (who may or may not be community-based) and government” (p.180). Traditional conceptualizations tend to be structuralist, static, and formal, and narrowly focus on property-rights distribution, institutions and government/community collaboration. Recent nuances emphasize process and function, integrate co-management within specific contexts, and interrogate the role of power relations among, and linkages across, diverse actors/organizations in tasks and processes that construct collaborative action at the confluence of government-bureaucracy, community, and market systems. They also embrace social and ecological complexity, including internally differentiated government and community partners, uncertainty and change, by integrating social learning processes [

3,

16,

18,

26,

36]. Plummer and FitzGibbon’s [

26] analytical framework approaches co-management in such a holistic manner, based on characteristics of co-management commonly found in the literature, classified into three categories: co-management context, components (pre-conditions, characteristics of practices, and outcomes), and linking mechanisms or relations across organizations and actors. This article adapts their framework to developing-country contexts, making more explicit the importance of power relations that place co-management within the realm of human behavior, and making livelihoods-driven social and ecological goals anticipated outcomes (

Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Conceptual Model for Analyzing Co-Management (Adapted from Plummer and FitzGibbon [

26])

.

Figure 2.

Conceptual Model for Analyzing Co-Management (Adapted from Plummer and FitzGibbon [

26])

.

Equally, there are many theories of co-management, including modeling, propositional, and analytical versions, but no coherent meta-theory that provides an overarching explanatory basis for the foundational question of why non-kin individuals decide to cooperate and participate in co-management activities [

4]. Benefits are the primary driving motivation, and individuals generally weigh costs against benefits and cooperate when benefits exceed costs [

37]. However, the nature of benefits and how individuals approach this cost/benefit calculation varies. The (still) dominant approach is based on rational-choice theory positing resource users as inherently self-interested individuals who collaborate only for personal benefit, and often cheat or free-ride to get ahead at the expense of the group, hence tragedy

à la Hardin [

38]. However, second-generation commons theory shows that humans have the need and ability to cooperate for broader social benefits or altruistic motivations under certain conditions, and focuses on understanding how groups can curb such temptations of self-serving, quick-fix and free-riding behavior in order to generate higher, long-term benefits for all parties [

37,

39]. Plummer and Fennell [

4] extend Trivers’s [

27] theory of reciprocal altruism from sociobiology which explains why kin co-operate, to cooperation among non-kin as “an important meta-theoretical perspective that helps to better understand co-management as a problem solving system” (p. 952). Trivers [

27] defines altruism as “a cost to one so that others benefit” (p. 948) and reciprocal altruism as “the trading of altruistic acts in which benefit is larger than cost so that over a period of time both enjoy a net gain” (p. 361). Trivers posits that cooperation of kin, and socio-evolutionary pressures selecting individual survival traits, serve the same purpose: to improve chances that their collective gene pool is passed on to next generations, even at the individual members’ expense. Plummer and Fennell [

4] adapt Trivers’ [

27] four pillars of reciprocal altruism and the behavioral system that regulates it, to explaining co-management. The pillars or expectations are (a) an interdependency based on partners helping each other while helping themselves, (b) a time lag between the altruistic action and the return benefit which should not be overly long, (c) a need for benefits to exceed costs for individual partners to ensure net positive gains for both parties long-term, and (d) the necessity of frequent interaction among parties which allows parties to punish non-reciprocating cheaters by withholding future acts of altruism from them, thereby suppressing cheating or free-riding behavior.

This study adapts Plummer and FitzGibbon’s [

26] framework (

Figure 2) to an analysis of co-management experiences from Malawi. The heavy dependence among contemporary co-management projects on cash incentives despite generally poor results, and the genuine need to enhance rural livelihoods and reduce poverty through sustainable forest management justifies examining alternative meta-theoretical explanations including the theory of reciprocal altruism.

4. Forest Co-Management Context in Malawi

4.1. Forest Co-Management Policy and Forest Right

Forest management policy in Malawi, like many developing countries, has come full circle from pre-colonial community “management” through cultural norms, practices and livelihood activities under traditional leadership, to colonial and post-colonial bureaucracy-based, “fences and fines” approaches that excluded local people and expropriated their land and forest-use rights through forest-reservation programs (late 19th to late 20th centuries), and to foresters reaching out of their “fortress” forests onto customary lands via outreach and extension programs culminating in co-management policies that allowed people back into forests (1990s). For Malawi, the 1996 Forest Policy and the Forest Act (1997) marked the paradigm shift that allowed the legal “return” of people back into FRs. The National Forestry Program (2001), forest policy supplement for PFM (2003), and various regulations and guides further articulated implementation strategies for co-management.

Malawi’s forestry policy and laws are progressive and can accommodate nearly any form of PFM. Implementation, however, lags behind. The forest policy (Section 2.3.1) seeks “to provide an enabling framework for promoting participation of local communities and the private sector in forest conservation and management, eliminating restrictions on sustainable harvesting of forest products by local communities through the development of joint forest management plans and management agreements with Village Natural Resource Management Committees (VNRMC)” [

40]. The 1997 Forest Act gives individuals or groups the right to license forest produce from unallocated customary lands and FRs [

41] (Section 83.3), although some vaguely defined sustainability requirements significantly restricted commercial charcoal production and industrial wood processing—convenient for an overcautious and protectionist DoF [

2,

33,

41,

42]. The Forest Act places co-management at the interface of bureaucracy-based property systems (FRs on public lands), community-based systems (mostly on unallocated/common-access customary lands), and market-based ones, united under a sustainable livelihoods approach. It further puts the onus for co-management on the DoF, while granting communities primary responsibility for CBFM on customary lands [

41] (Sections 24 and 25).

4.2. Characteristics of Ntchisi Forest Reserve

Ntchisi FR (9,710 hectares) was established in 1924 after the British colonial government moved villages out of the area. The reserve is relatively intact, and located in a mountainous rural setting. It is the source of three locally important perennial streams and has one of few remaining sub-montane evergreen forests in Malawi. The reserve is mostly

Brachystegia-dominated

miombo woodland with 150 hectares of degraded pine plantation. Regular threats are bush fires, encroachment for agriculture, illegal timber harvesting, and limited wildlife poaching. Infestation of emperor moths (explained later) was a recent major threat to the reserve. Poverty was an underlying problem. A project-wide baseline survey highlighted the local importance of FRs as a safety net. Two-thirds of households in participating areas were locally classified as poor or very poor, food insecure, and dependent on forest resources to supplement their livelihoods [

43]. Seventeen of 27 local livelihoods identified—and 75% of all non-agriculture livelihoods—were highly dependent on forests.

4.3. The IFMSLP and Forest Co-Management Processes

The purpose of the Indigenous Forest Management for Sustainable Livelihoods Program (IFMSLP) is “to improve the livelihoods of forest-dependent communities (men, women, boys and girls) through improved sustainable collaborative management of forests both in forest reserves and customary land” [

43,

44]. It has four results areas: (1) sustainable livelihood strategies promoted within impact areas; (2) equitable access to forest resources secured by increasing the area under sustainable forest management arrangements (focusing on 12 FRs in 13 of Malawi’s 28 districts and half of adjacent customary-land forests); (3) strengthened governance of key forest resources within the forest sector; and (4) communication and advocacy enhanced among stakeholder groups along with administrative and technical support. The project is well funded through two EU grants and implemented by the DoF, assisted by an international technical implementing agency and experts. Phase 1 (2006–2009, €19.68 million) focused on community mobilization, institution building and forest management planning. Phase 2 (April 2011–2015, €9.80 million), following a disruptive 20-month funding break, refocuses the objectives around fewer strategies and includes approximately €2 million in competitive grants for non-state actors to enhance their role in, and to accelerate, project implementation. The EU imposed four special conditions for project funding to ensure Malawi government commitment to co-management: (a) developing licensing and benefit sharing systems for commercial utilization of forest produce as per the 1997 Forest Act; (b) reactivating the legally constituted Forestry Development and Management Fund to enable the DoF to retain much of its revenues for reinvesting in forestry development; (c) filling key staff positions and restructuring the DoF to better facilitate co-management/PFM; and (d) granting greater financial autonomy and funding to the Malawi College of Forestry and Wildlife to enhance its training capacity for PFM.

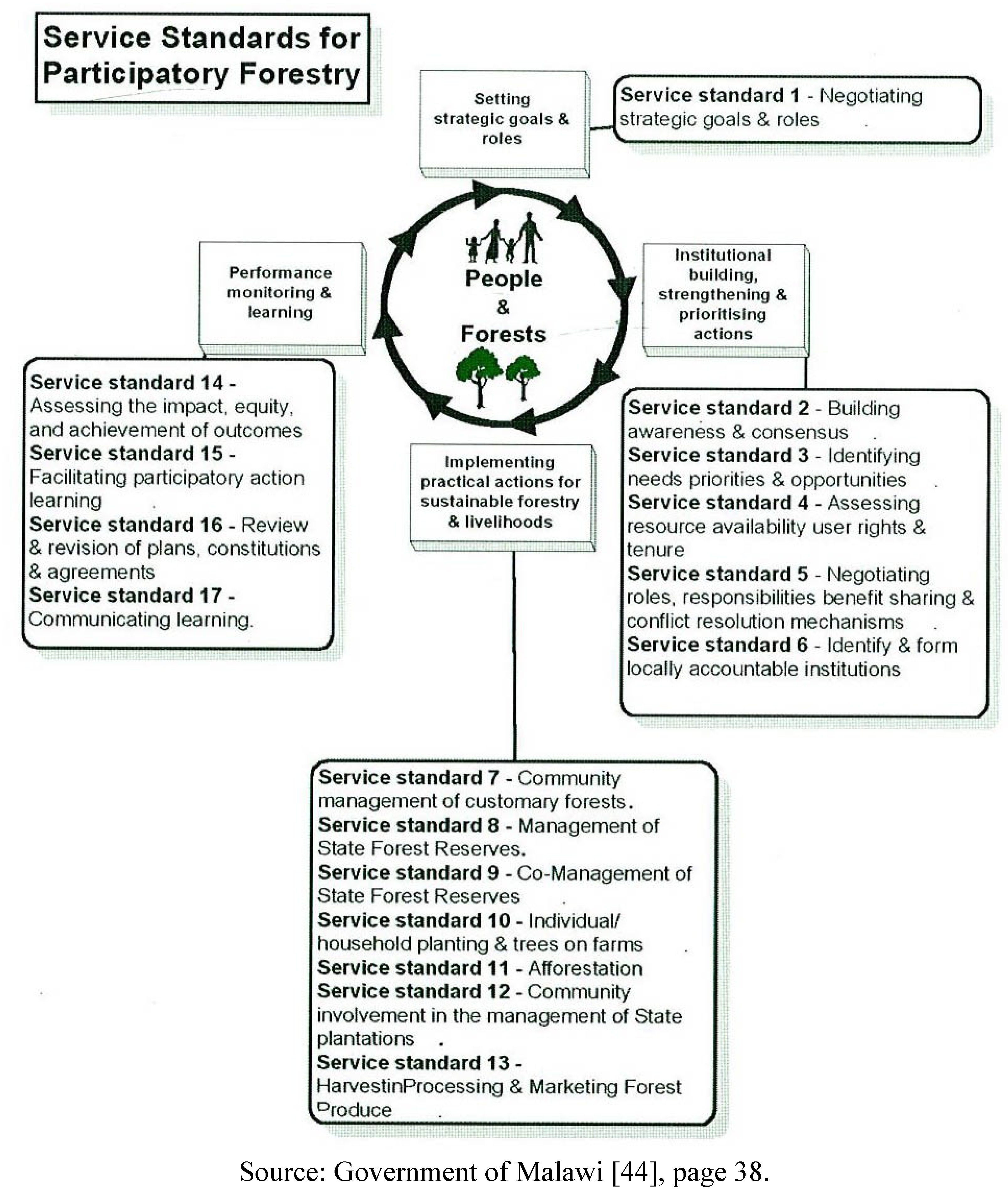

The IFMSLP led the development of, and adopted, the

Standards and Guidelines for Participatory Forestry in Malawi. The guidebook is a best-practice tool for PFM facilitation, implementation and monitoring based on current forestry and decentralization policies and laws. It has 17 service standards organized into four stages: (1) setting strategic goals and roles, (2) institutional building, strengthening, and prioritizing actions, (3) implementing practical PFM actions, and (4) performance monitoring and learning/lesson sharing. The co-management sub-model consisted mainly of service standards 1–6, 8–9, and 13–17 (

Figure 3). Adding service standard 7 accommodates CBFM on adjacent customary lands. Baseline analysis and institutional building processes (stage 2) included sophisticated analysis such as sustainable livelihoods analysis, appreciative inquiry, stakeholder analysis, institutional mapping, and participatory forest resource assessment and management planning. Enterprise-plan development emphasized business viability and ecological sustainability. It included market analysis, value-chain analysis to cut out middlemen and maximize profits, and financial flows.

Figure 3.

Models for Participatory Forest Management and Co-management in Malawi.

Figure 3.

Models for Participatory Forest Management and Co-management in Malawi.

6. Discussion—Co-Management, Economic Incentives and Reciprocal Altruism

Is cash the definitive motivation for resource users to decide to participate in forest co-management? What are implications of a singular emphasis on cash incentives? Among the insights gained from co-management experiences in Malawi, findings associated with these foundational questions emerged particularly important in gaining a nuanced understanding of co-management given the need for and prominence accorded to cash incentives. The theory of reciprocal altruism [

4,

27] was useful in explaining the paradoxical finding that, despite six years of disappointingly low financial benefits for poor communities burdened with conservation costs, a high proportion of them remained committed and willing to start or continue participating in co-management. Findings showed that not only was the near-singular emphasis on cash incentives inadequate to capture the range of local motivations for co-management, the underlying rational choice theory of self-interested resource users participating only for personal gain was also insufficient to explain co-management outcomes. Moreover, it undermined socio-ecological sustainability goals by providing perverse incentives to take “short-cuts” in forest-management planning (e.g., rushed wholesale allocation of reserves instead of a measured pilot approach and “upside-down” forest-management planning), to unintentionally marginalize the poor (user-group member fee requirements), and promote dependency on short-term project inputs rather than long-term co-management outcomes.

The finding that the non-cash forest-ecosystem service of rainfall regulation and rights-based, issues of equitable access to forest resources including inter-generational equity topped the list of motivations for co-management even as financial incentives remained important, speaks almost directly to the sociobiological basis of reciprocal altruism. As in Plummer and Funnel’s [

4] adaptation of the theory to explain why non-related individuals cooperate, individual resource users helped each other so that they could all benefit, despite poor/no personal financial benefit in the short term. The moralistic force behind the inter-generational equity motive was strong and frequently invoked in interviews and focus groups. The DoF also had taken a risk in allowing people back into reserves without sufficient precedence assuring mutual benefits and success. While suspicion of community abilities persisted at senior levels [

57], frontline and district extension staff had built significant mutual trust and positive relations with resource users. The collective guarding of forests against

matondo harvesters suggests emergence of altruistic partnerships that form a foundation for further cooperation.

For many users, six years appeared to be within the tolerable time lag between individual users’ first performing of the altruistic act of participating in co-management and receiving expected returns for the act, although there were early signs of impatience or defection. Given the context of rampant poverty, even the low initial benefits from the reserve and supplemental ones from village forests appeared to give users (88% of Nyanja residents) hope that they would ultimately benefit, and to stretch tolerable lag times out. It remained to be seen whether individual benefits of partners would exceed costs and yield a net positive result in the long term. The intricate institutional arrangements and processes developed could constitute a regulating system for altruism as a basis for co-management motivations. However, as the pillars of reciprocal altruism indicate, there is a time limit for users to wait before they get anticipated benefits (cash or non-cash) beyond which the regulating system is expected to collapse.

A regulatory mechanism for reciprocal altruism must also detect and purge cheating or free-riding behavior, just as rational-choice explanations and cash-driven incentives approaches have attempted to do. The Nyanja community had done well so far in keeping elite capture down and achieving reasonable participation levels through various institutional and practical accountability measures. This illustrated, as other studies have, that elite capture is not inevitable [

21,

58]. In addition, the regulatory system must stop parasitization on a few exceptionally selfless individuals [

4]. Forest committee (BMCs, VNRMCs) members bore a disproportionately high share of the co-management burden. Nyanja BMC members spent up to eight hours per day, two to three times per week on regular forest patrols and 12 hours nearly daily during the

matondo season, in addition to time spent on other functions, without separate compensation. As with co-management approaches in many developing countries, the project focused equity considerations on sharing benefits (mostly cash) while paying inadequate attention to equally important issues of

cost sharing among users. Dismissing the extraordinary sacrifice of co-management leaders as expected voluntarism reinforces the erroneous assumption that “rural people have abundant ‘free’ labor/time” [

57]. Committee members often have to choose between meeting the disproportionate time and physical burdens to be effective co-management leaders, and spending time on personal livelihood activities to support their families. Further, uncompensated committee members often feel entitled to, and are tempted to fraudulently obtain, financial compensation, increasing risks of elite capture [

5]. This cost-sharing disparity is arguably one of “the elephants in the co-management or PFM room”. It is self-defeating, even in cash-driven interventions targeting poverty reduction, for governments and donors to expect business-sound forest-based enterprises from volunteer, uncompensated community leadership. Without confronting this problem by at least allowing open discussions and a search for locally appropriate compensation solutions, it will remain a source of risk of elite capture by committees, and undermine leadership and benefits including poverty-reduction potential of co-management. It also undercuts sustenance of reciprocal altruism as a basis for co-management.

Findings point to the need to broaden co-management incentives mechanisms beyond cash-driven motivations to include locally relevant non-cash ecological and social benefits in order to better capture reality, temper inflated expectations, and balance goals of material wellbeing, environmental stewardship and social justice [

1]. The generally low exchange value of miombo woodlands and other forest ecosystems in many developing countries [

5,

20,

59] and inefficiencies in generating cash benefits accentuate the importance of broadening incentives and benefits. This also minimizes perverse incentives associated with cash-driven approaches, including marginalization of the poor [

34,

60], temptations to overharvest valuable species, take forest-management short cuts, and to free-ride on the project/government. In contrast, to base incentives mechanisms solely or overwhelmingly on such low potential financial returns is to build co-management on a shaky foundation. According to Nelson and Agrawal [

17], balancing real cash needs and incentives and interests of the poor can come down to a choice between the “most effective” PFM which is dependent for incentives on high resource value but also attracts elite interests and capture, and “politically possible” PFM with lower resource values providing fewer but accessible benefits for the poor. For Ntchisi, this translates not only into balancing the promotion of simple, low-cost, low-technology (e.g., firewood, bamboos, poles, hoe-handles, pottery) products in relatively localized markets in order to target the poor, with higher-end products (e.g., timber, honey, and mushrooms) requiring more inputs, processing or technology, and sophisticated understanding of markets which are often dominated by wealthier users, but also to incorporate non-cash benefits. The nested

cross-level/scale institutional mechanisms also offer a mechanism to facilitate the broadening of incentives mechanisms in various ways discussed earlier (e.g., expanding the resource base, uses and benefits into village forests, and the range and levels of opportunities to participate). The enterprise and forest-management start-up grants (in kind) also reduced entry investment costs into higher-value enterprises and helped level the playing field for the poor and ensure them more equitable access to expanded forest-resource rights in the project generally. However, such measures should have safeguards against creating or reinforcing project or government dependency. Further, inefficiencies in revenue generation need to be minimized, including bureaucratic delays and skill gaps in enterprise development and marketing.

7. Conclusions

This study has examined experiences in bringing people back into protected forests in developing countries through co-management approaches using early insights from an EU-funded co-management project in Malawi. It used mixed social science research methods, a nuanced, process-based conceptualization of co-management operationalized through a holistic analytical framework. The theory of reciprocal altruism from sociobiology [

4,

27] was used as a meta-theoretical explanation for continued local user participation in co-management even with disappointing financial returns.

Results were mixed, but early institutional and ecological outcomes showed generally positive trends. Systematic and concerted institution building processes laid a promising foundation for co-management. This included empowered local organizations, resource-use rules and accountability measures, enhanced relations of trust and cooperation within communities and between them and DoF staff, and generally increased capacity to conduct both technical and organizational tasks within co-management. Instituting practical accountability measures and ensuring broad community empowerment minimized elite capture and affirmed that it is not inevitable. The extraordinarily generous forest-use rights devolved to communities under the Forest Act (1997) and project-instituted community licensing and benefit-sharing systems also contributed to the trust-building and observed improvements in forest condition within and outside the reserve. However, community failure to fully implement forest-management plans, weak management-planning processes, and the brief implementation timescale made assessment of long-term forest sustainability premature.

The major downside was disappointing financial benefits, which informed the primary argument that a narrow emphasis on cash incentives as the motivation for “self-interested” users to participate in co-management overlooks locally significant non-cash motivations, inflates local expectations beyond ability to deliver, and often creates perverse incentives that undermine socio-ecological goals. The theory of reciprocal altruism provided a balanced meta-theoretical explanation for why many resource users continued collaborating in co-management despite six years of conservation burdens for minimal financial returns. Locally dominant non-cash motivations involving rain regulation and forest-rights based equity issues including inter-generational equity helped to explain the seeming paradoxical finding, along with inefficiencies deriving from poor enterprise planning and choice, wood-extraction challenges, and extraordinary (donor) bureaucratic delays. Findings suggest that co-management interventions should adopt a pluralistic approach to incentives mechanisms (including non-cash ones). This allows the harnessing of possible synergies among diverse motivations that produces tempered and potentially enduring co-management. Cheating and parasitization on a few dedicated individuals undermines both cash-driven approaches and regulating mechanisms for reciprocal altruism. While effective accountability measures minimized committee cheating, the study highlights the need to pay more attention to equitable cost sharing by encouraging open discussion to find transparent, negotiated and locally appropriate compensation measures (even if they agree on providing no compensation) for co-management leaders. Along with enhancing efficiency and reducing risks of corruption and elite capture, this move would also address the widespread contradiction among well-meaning co-management projects of expecting efficient and money-spinning forest-based enterprises from relatively casual, voluntary, and uncompensated community leadership.

Adoption of the nested multi-scalar institutional approach built on user groups, and formal funding (10% of license fees) cross-level institutional arrangements under LFMB coordination improved chances of holistic cross-block management, but LFMB roles and legitimacy need further clarity. Integrating adjacent village forests into co-management processes eased benefit and extraction pressures on the reserve, enhancing forest condition and holistic management while also buying some time for benefit generation from the reserve. The nested scalar system and coupling of reserve/village forests was therefore an important mechanism in broadening resource rights and incentives mechanisms. Findings supported forestry agencies producing (negotiated) reserve-wide management plans that reconcile local and wider interests and guide community management through suitability zoning, and using a pilot approach could avoid overextending efforts, undermining quality, and poor/late benefit delivery.

This article contributes to policy and academic debates on how to bridge the persistent gap between co-management theory/policy and reality in developing countries using a nuanced, process-based conceptualization of co-management. It extended socio-ecological analysis of co-management with insights from the sociobiological theory of reciprocal altruism at least as an alternative explanation for motivational elements of co-management. While co-management generally showed some early promise for protected-forest management, institutions take considerable effort and time to build, forest benefits and cash incentives are often limited, and outcomes are context specific and unpredictable. Future research should focus on finding ways for embracing this inherent socio-ecological complexity, uncertainty and change, including through integration of social learning into co-management processes to enhance the adaptive capacity of institutions. Finding minimum skills sets and procedures needed for participatory forest management assessment and planning, and enterprise development planning which balance technical effectiveness with the need for meaningful community participation, needs more immediate research.