Wild Food, Prices, Diets and Development: Sustainability and Food Security in Urban Cameroon

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature, Concepts and Themes

2.1. Getting Wild: The Continuum of Human-Plant Interaction

2.2. Urbanization and the Availability, Accessibility and Adequacy of Wild Food

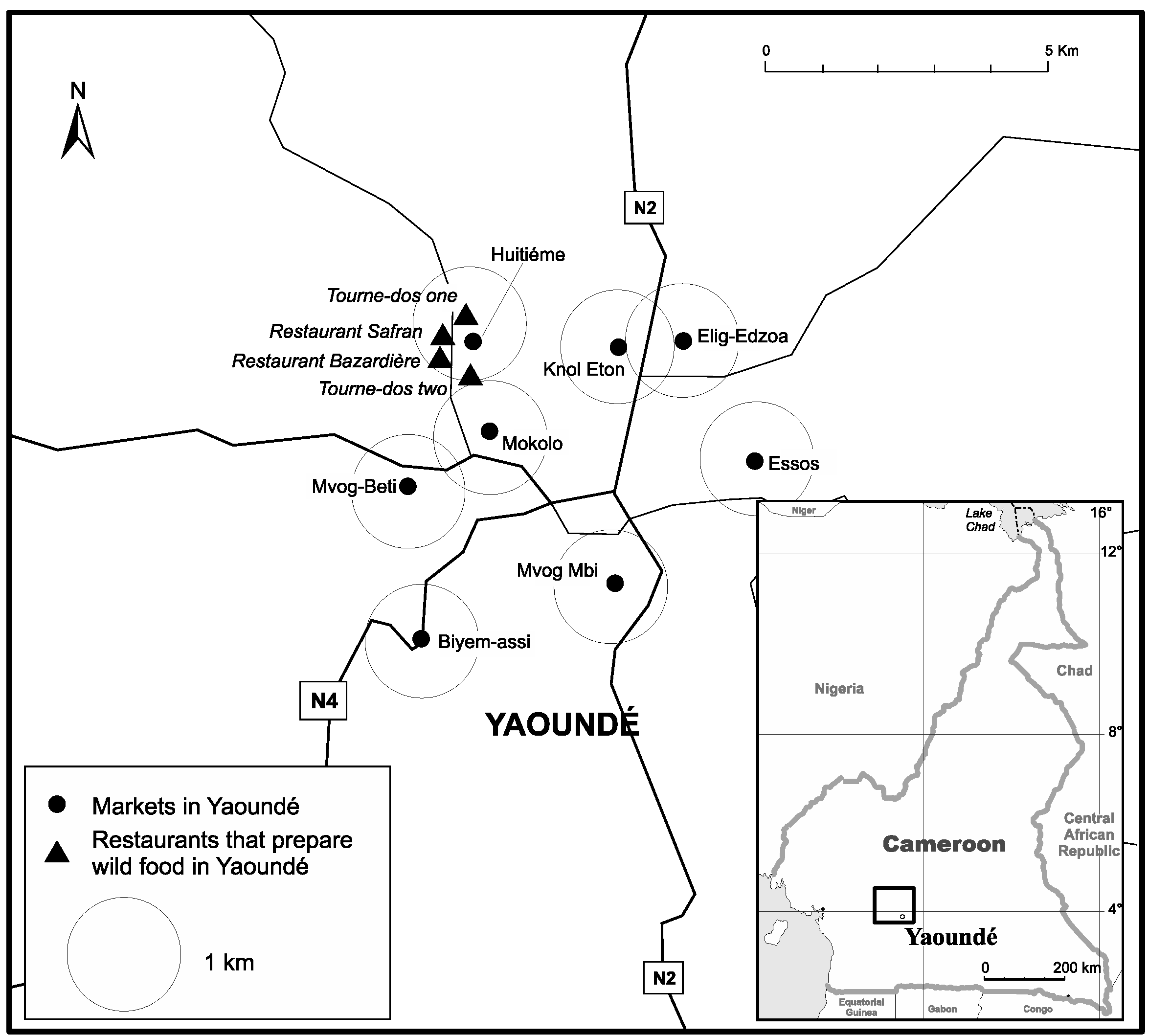

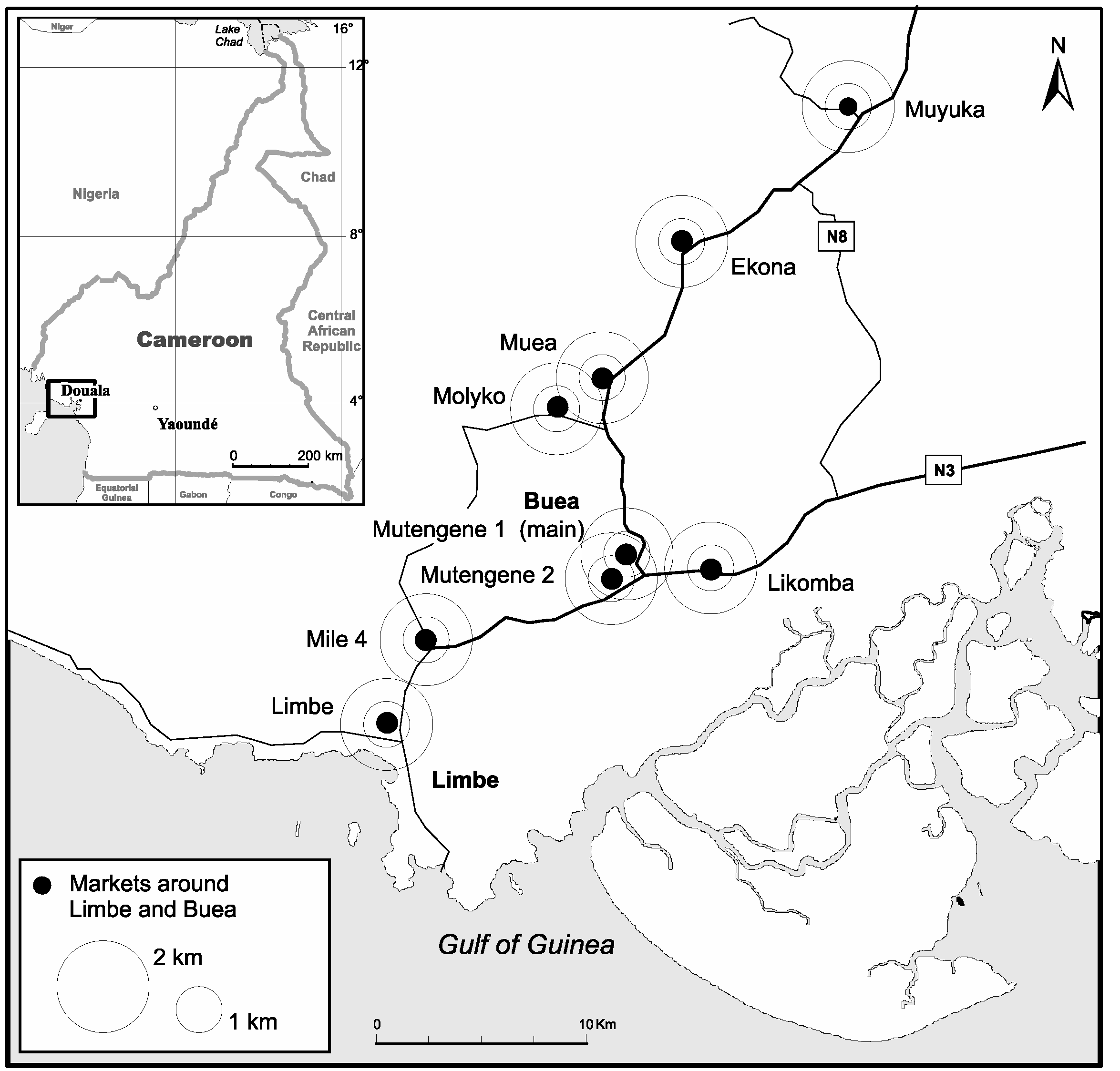

3. Methodology

| Interviews (n = 367) | Total # | % | Interviews (n = 371) | Total # | % | Households (n = 197) | Total # | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age < 20 | 3 | 0.8 | Male | 54 | 14.5 | Poor | 44 | 22.6 |

| Age 20–40 | 197 | 53.7 | Female | 317 | 85.5 | Middle | 126 | 64.6 |

| Age 40+ | 135 | 36.8 | Rich | 16 | 8.2 | |||

| No answer | 32 | 8.7 | No answer | 9 | 4.6 |

4. Results

4.1. Availability

| Wild food | Peak periods of abundance | Use and Preparation |

|---|---|---|

| Eru/okok (Gnetum africanum) | All year, but more in the rainy season | Sliced thinly and cooked in a stew with waterleaf, cow skin, dried fish and crayfish and palm oil and eaten with cassava fufu |

| Bush mango (Irvingia spp.) | July and August and September and October | Fruit is popular for children; stone is dried and ground down and used as a soup thickener |

| African plums, safou (Dacryodes edulis) | April–October | Fruit is boiled or roasted before it is consumed |

| Kola (Cola acuminata; Cola pachycarpa K.; Cola nitida) | August–September | Chewed when drinking palm wine; stimulant |

| Njansang (Ricinodendron heudoletii) | May–September | Dried and prepared in a soup; can be substituted for groundnut in soups and stews |

| Bush onion or country onion (Afrostyrax kamerunensis/ Afrostyrax lepidophyllus) | July–August | Used in soups and stews as a condiment or spice, especially in ekwang. |

| Mbongo (Aframomum citratum) | May–September | Roasted until charred then ground and mixed with other spices usually for a fish soup (mbongo tchobi) |

| Rondelle (Scorodophloeus zenkeri Olom) | All year | Seeds and bark from the tree are eaten after simple drying. Pulped or ground, they have a flavor similar to garlic and are used as a spice in cooking |

| Alegata pepper (Afromomum melegueta) | n/a | Used in soups and stews and holds cultural significance to ward off evil spirits |

| Pebe (Monodora myristica (Graertm.) Dunal African nutmeg | n/a | Seeds from the tree are dried and sold whole or ground to be used in stews, soups, cakes and desserts |

| Quatre cote (Tetrapleura tetraptera) | n/a | Spice for stews |

| Caterpillars (Rhynchophorus phoenicis) | June–July | Roasted and or dried for soups and stews |

| Termites | March–September | Protein, dried and roasted |

| Mushrooms (several species) | Rainy season | Protein, prepared in a stew |

| Forest snails (several species) | Rainy Season | Protein, prepared in stews and also boiled and roasted |

| Honey | All year | Medicine, food, gift |

| Bushmeat (various, including antelope, snake, cane rat (Thryonomys) and pangolin (Manis tricuspis) | All year | Protein, prepared from fresh, roasted or dried to be used in stews |

4.2. Over-Exploitation

4.3. Accessibility

| Wet season price Yaoundé | Dry season price Yaoundé | Wet season price Buea and Limbe | Dry season price Buea and Limbe |

|---|---|---|---|

| njansang/50–100 cup | njansang/50 smallest cup | njansang/250–400 cup | njangsang/350 glass |

| bush mango/50 a cup | bush mango/100 a cup | bush mango/200–800 cup | bush mango/500 glass |

| okok/100 cup | okok/50 smallest cup | eru/1200 2 kg | eru/1200 3 kg bundle |

| rondelle/50–100 cup | rondelles/25 for two cloves (gousses) | n/a | n/a |

| mushrooms/100–200 cup | mushrooms/150 a head | mushroom/250 glass | n/a |

| termites/100 cup | termites/25 the smallest box | n/a | n/a |

| mbongo 50–100/cup | mbongo/25 for 1–2 cloves | n/a | n/a |

| bushmeat/5000 | bush meat/7000 | wild game/3000 2kg | wild game/3000 1kg antelope |

| snails/100–200 cup | snails/75 for one | snails/500 for 1/4 kg | snails/700 1/4kg |

4.4. Strategies to Cope with Increasing Prices

- I manage with the little I have

- I am stricter about how much food I serve and other than the children we only eat one meal a day

- I make a cheap meal with rice and palm oil or garri (cassava) and water

- I reduce the quantity of food I eat

- I eat one or two meals a day

- I harvest from my farm

- I borrow from family, savings group, or merchant

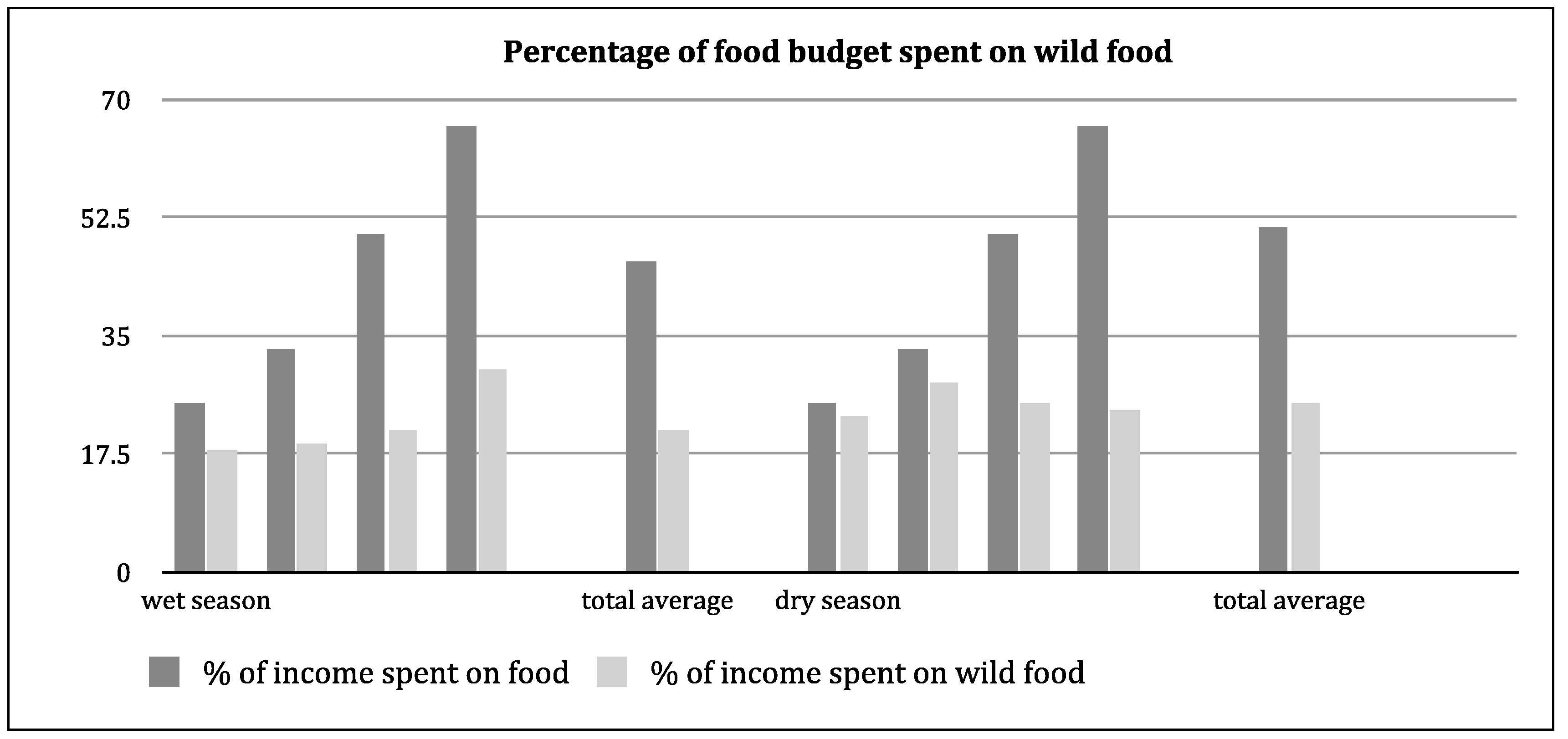

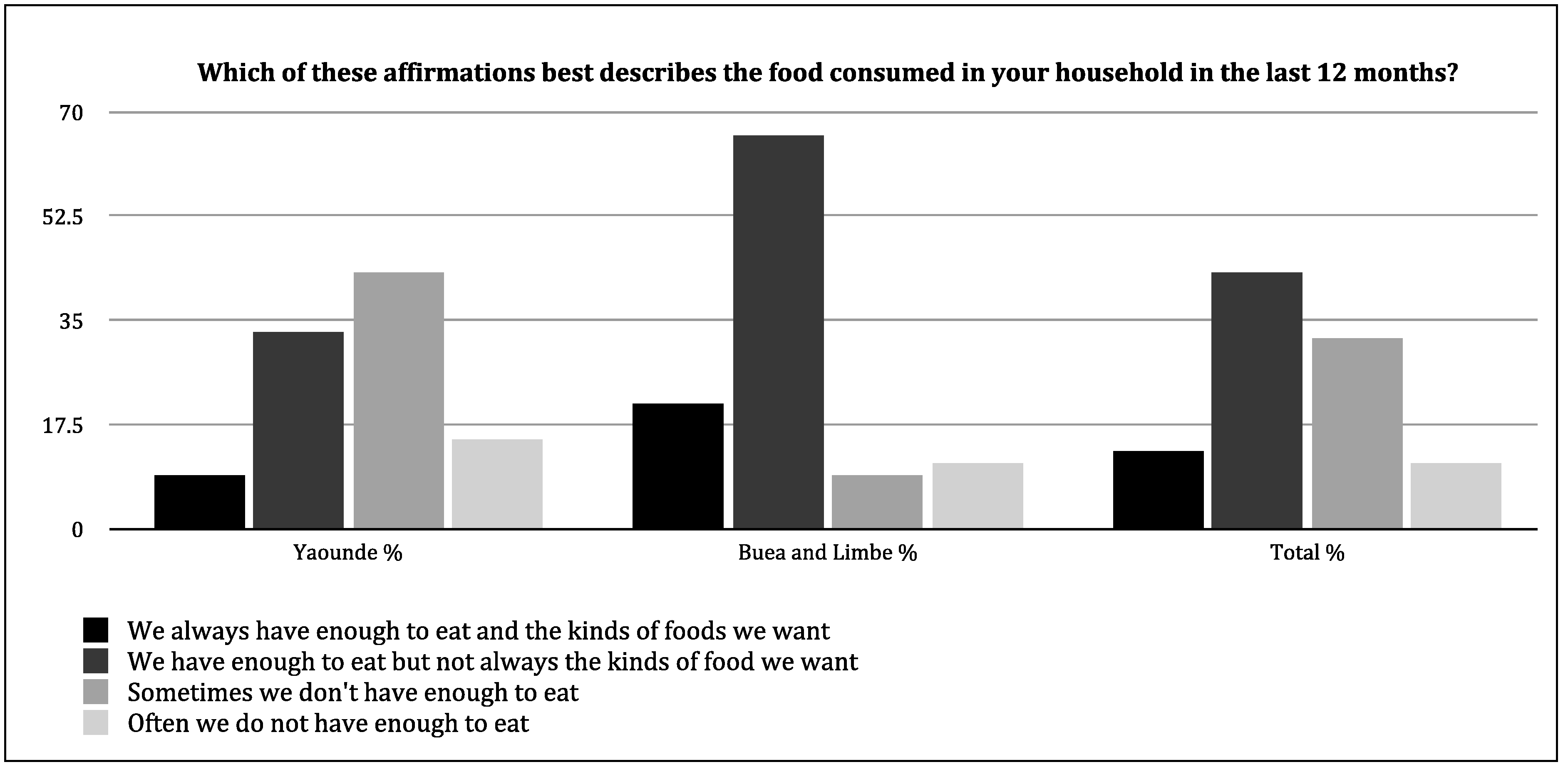

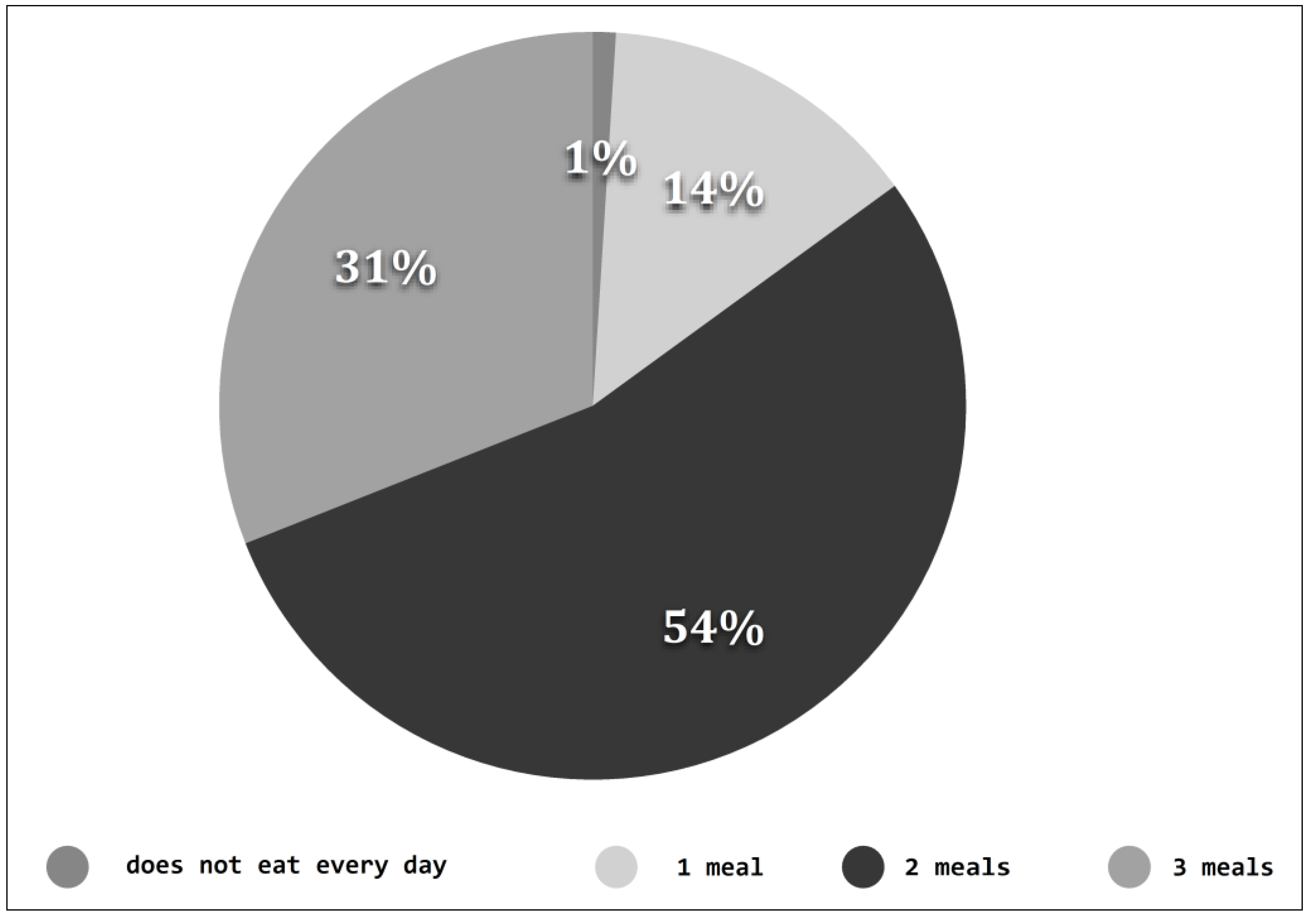

4.5. Adequacy

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Acknowledgements

References

- Pimentel, D.; McNair, M.; Black, L.; Pimentel, M.; Kamil, J. Value of forests to world food security. Hum. Ecol. 1997, 25, 91–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grivetti, E.L. Nutritional Geography, History and Trends. Nutr. Anthropol. 2000, 23, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herforth, A. Nutrition and the Environment: Fundamental to Food Security in Africa. In The African Food System and Its Interaction with Human Health and Nutrition; Pinstrup-Andersen, P., Ed.; Cornell University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 128–160. [Google Scholar]

- Pinstrup-Andersen, P. The African Food System and Its Interaction with Human Health and Nutrition: A Conceptual and Empirical Overview. In The African Food System and its Interaction with Human Health and Nutrition; Pinstrup-Andersen, P., Ed.; Cornell University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhnlein, H.; Erasmus, B.; Creed-Kanashiro, H.; Englberger, L.; Okeke, C.; Turner, N.; Allen, L.; Bhattacharjee, L. Indigenous peoples’ food systems for health: finding interventions that work. Publ. Health Nutr. 2007, 9, 1013. [Google Scholar]

- Tieguhong, J.C.; Ndoye, O.; Vantomme, P.; Grouwels, S.; Zwolinski, J.; Masuch, J. Coping with Crisis in Central Africa: enhanced role for non-wood forest products. Unasylva 2009, 223, 49–54. [Google Scholar]

- Malleson, R.; Asaha, S.; Sunderland, T.; Burnham, P.; Egot, M.; Obeng-okrah, K.; Ukpe, I.; Miles, W. A Methodology for Assessing Rural Livelihood Strategies in West/Central Africa: Lessons from the Field. Ecol. Environ. Anthropol. 2008, 4, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Oyono, R.; Blaise, M.; Kombo, S. Beyond the Decade of Policy and Community Euphoria: The State of Livelihoods Under New Local Rights to Forest in Rural Cameroon. Conservat. Soc. 2012, 10, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scoones, I.; Melnyk, M.; Pretty, J.N. The Hidden Harvest: Wild Foods and Agricultural Systems. A Literature Review and Annotated Bibliography; International Institute for Environment and Development: London, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Food Balance Sheets: A Handbook. Available online: ftp://ftp.fao.org/docrep/fao/011/x9892e/x9892e00.pdf (accessed on 30 October 2013).

- Bharucha, Z.; Pretty, J. The roles and values of wild foods in agricultural systems. Phil. Trans. Biol. Sci. 2010, 365, 2913–2926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modi, M.; Modi, A.T.; Hendriks, S. Potential Role for Wild Vegetables in Household food Security: A Preliminary Case Study in Kwazulu-Natal, South Africa. AJFAND 2006, 6, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Etkin, N.L. Eating on the Wild Side: The Pharacologic, Ecologic, and Social Implications of Using Noncultigens; Etkin, N.L., Ed.; The University of Arizona Press: Tuscon, AZ, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhnlein, H.V.; Erasmus, B.; Spigelski, D. Indigenous Peoples’ Food Systems: the Many Dimensions of Culture, Diversity and Environment for Nutrition and Health; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Compton, J.; Wiggins, S.; Keats, S. Impact of the Global Food Crisis on the Poor: What Is the Evidence? UKAID: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Development Studies. Accounts of Crisis: Poor People’s Experiences of the Food, Fuel and Financial Crises in Five Countries; Hossain, N., Ebyen, R., Eds.; Institute of Development Studies: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Corbett, J. Famine and Household Coping Strategies. World Dev. 1988, 16, 1099–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilgrim, S.; Cullen, L.; Smith, D. Hidden Harvest or Hidden Revenue? Local resource use in a remote region of Southeast Sulawesi, Indonesia. IJTK 2007, 6, 150–159. [Google Scholar]

- Gbetnkom, D. Forest Depletion and Food Security of Poor Rural Populations in Africa: Evidence from Cameroon. J. Afr. Econ. 2008, 18, 261–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadjichambis, A.C.; Paraskeva-Hadjichambi, D.; Della, A.; Elena Giusti, M.; de Pasquale, C.; Lenzarini, C.; Censorii, E.; Gonzales-Tejero, M.R.; Sanchez-Rojas, C.P.; Ramiro-Gutierrez, J.M.; et al. Wild and semi-domesticated food plant consumption in seven circum-Mediterranean areas. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2008, 59, 383–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crush, J.S.; Frayne, G.B. Urban food insecurity and the new international food security agenda. Dev. South. Af. 2011, 28, 527–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moseley, W.G.; Carney, J.; Becker, L. Neoliberal policy, rural livelihoods, and urban food security in West Africa: A comparative study of The Gambia, Cote d’Ivoire, and Mali. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 5774–5779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, L.; Legwegoh, A. Comparative urban food geographies in Blantyre and Gaborone. Afr. Geogr. Rev. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Schutter, O. Report submitted by the Special Rapporteur on the right to food. Available online: http://www2.ohchr.org/english/issues/food/docs/A-HRC-16-49.pdf (accessed on 30 October 2013).

- De Schutter, O. Report of the Special Rapporteur on the right to food: Mission to Cameroon. Available online: http://www.ohchr.org/Documents/HRBodies/HRCouncil/RegularSession/Session22/A-HRC-22-50-Add2_en.pdf (accessed on 30 October 2013).

- FAO. Rome Declaration on World Food Security. In Proceedings of World Food Summit, Rome, Italy, 13–17 November 1996; FAO: Rome, Italy.

- Brundtland, H. Our Common Future: Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- No more chicken, please: How a strong grassroots movement in Cameroon is successfully resisting damaging chicken imports from Europe, which are ruining small farmers all over West Africa. Available online: http://aprodev.eu/files/Trade/071203_chicken_e_final.pdf (accessed on 30 October 2013).

- Comprehensive Food Security and Vulnerability Analysis: Guidelines. Available online: http://home.wfp.org/stellent/groups/public/documents/manual_guide_proced/wfp203202.pdf (accessed on 4 November 2013).

- Carolan, M.S. The Wild Side of Agro-food Studies: On Co-experimentation, Politics, Change, and Hope. Sociol. Rural. 2013, 53, 413–431. [Google Scholar]

- Tsing, A.L. Friction: An Ethnography of Global Connection; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kliskey, A.D.; Kearsley, G.W. Mapping multiple perceptions of wilderness in southern New Zealand. Appl. Geogr. 1993, 13, 203–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoreau, H.D. Walden, Or, Life in the Woods; Dover Publications: Mineola, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Stankey, G.H.; Schreyer, R. Attitudes toward Wilderness and Factors Affecting Visitor Behavior: A State-of-Knowledge Review. In Proceedings of National Wilderness Research Conference: Issues, State-of-Knowledge, Future Directions, Fort Collins, CO, USA, 23–26 July 1985; Intermountain Research Station: Ogden, UT, USA, 1985; pp. 246–293. [Google Scholar]

- Neumann, R.P. Imposing Wilderness: Struggles Over Livelihood and Nature Preservation in Africa; University of California Press: Berkley, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Ndenecho, E.N. Ethnobotanic Resources of Tropical Mountane Forests: Indigenous Uses of Plants in the Cameroon Highland Ecoregion; Langaa Research and Publishing Cameroon Initiative Group: Bamenda, Cameroon, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Voeks, R.A. Are women reservoirs of traditional plant knowledge? Gender, ethnobotany and globalization in northeast Brazil. Singapore J. Trop. Geogr. 2007, 28, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, D.R.; Hillman, G.C. Foraging and Farming: The Evolution of Plant Exploitation; Unwin Hymen: London, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Logan, M.H.; Dixon, A.R. Agriculture and the Acquisition of Medicinal Plant Knowledge. In Eating on the Wild Side: The Pharacologic, Ecologic, and Social Implications of Using Noncultigens; Etkin, N., Ed.; The University of Arizona Press: Tuscon, AZ, USA, 1994; pp. 24–45. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, N.F. The Origins of Plant Cultivation in the Near East. In The Origins of Agriculture: An International Perspective; Smithsonian Institution Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1992; pp. 39–58. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham, A.B. Applied Ethnobotany: People, Wild Plant. Use and Conservation; Earthscan: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Vansina, J. Paths in the Rainforests: Toward a History of Political Tradition in Equatorial Africa; University of Wisconsin Press: Madison, WI, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Posey, D.A.; Balick, M. Human impacts on Amazonia: the role of Traditional Ecological Knowledge in Conservation and Development; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Posey, D.A. Indigenous management of tropical forest ecosystems: the case of the Kayapo indians of the Brazilian Amazon. Agrofor. Systems 1985, 3, 139–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johns, T.; Sthapit, B.R. Biocultural diversity in the sustainability of developing country food systems. Food Nutr. Bull. 2004, 25, 143–155. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, N.J.; Łuczaj, Ł.J.; Migliorini, P.; Pieroni, A.; Dreon, A.L.; Sacchetti, L.E.; Paoletti, M.G. Edible and Tended Wild Plants, Traditional Ecological Knowledge and Agroecology. Crit. Rev. Plant. Sci. 2011, 30, 198–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, J.C. The Moral Economy of the Peasant: Rebellion and Subsistence in Southeast. Asia; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal, A. Dismantling the Divide Between Indigenous and Scientific Knowledge. Dev. Change 1995, 26, 413–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IAASTD. Agriculture at A CrossroadsInternational Assessment of Agricultural Knowledge, Science and Technology for Development; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Thrupp, L.A. Linking Agricultural Biodiversity and food security: The valuable role of agrobiodiversity for sustainable agriculture. Int. Aff. 2000, 76, 265–281. [Google Scholar]

- Pieroni, A.; Nebel, S.; Santoro, R.F.; Heinrich, M. Food for two seasons: culinary uses of non-cultivatedlocal vegetables and mushrooms in a south Italian village. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2005, 56, 245–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frison, E.A.; Cherfas, J.; Hodgkin, T. Agricultural Biodiversity Is Essential for a Sustainable Improvement in Food and Nutrition Security. Sustainability 2011, 3, 238–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doughty, J. Decreasing variety of plant foods used in developing countries. Qualitas Plant. 1979, 29, 163–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turnbull, C.M. The Forest People: A study of the Pygmies of the Congo; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Sunderlin, W.D.; Angelsen, A.; Belcher, B.; Burgers, P.; Nasi, R.; Santoso, L.; Wunder, S. Livelihoods, forests, and conservation in developing countries: An Overview. World Dev. 2005, 33, 1383–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerutti, P.O.; Tacconi, L. Forests, Illegality, and Livelihoods: The Case of Cameroon. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2008, 21, 845–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aberoumand, A. Nutritional Evaluation of Edible Portulaca oleracia as Plant Food. Food Anal. Method. 2009, 2, 204–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belcher, B.M. What isn’t an NTFP? Int. Forest. Rev. 2003, 5, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shackelton, S.; Shanley, P.; Ndoye, O. Invisible but Vaible: recognizing local markets for non-timber forest products. Int. Forest. Rev. 2007, 9, 697–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tieguhong, J.C.; Ndoye, O. The Impact of Timber Harvesting on the Availability of Non-Wood Forest Products in the Congo Basin; Food and Agriculture Organization: Rome, Italy, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Ndoye, O.; Perez, M.R.; Eyebe, A. The Markets of Non-timber Forest Products in the Humid Forest Zone of Cameroon; Overseas Development Institute: London, UK, 1997; pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Ingram, V.; Ndoye, O.; Iponga, D.M.; Tieguhong, J.C.; Nasi, R. Les produits forestiers non ligneux: contribution aux economies nationales et strategies pour une gestion durable. Available online: http://dare.uva.nl/document/358169 (accessed on 30 October 2013).

- Perez, M.R.; Ndoye, O.; Eyebe, A.; Puntodewo, A. Spatial characteristics of non-timber forest product markets in the humid forest zone of Cameroon. Int. Forest. Rev. 2000, 2, 71–83. [Google Scholar]

- Nkem, J.; Kalame, F.B.; Idinoba, M.; Somorin, O.A.; Ndoye, O.; Awono, A. Shaping forest safety nets with markets: Adaptation to climate change under changing roles of tropical forests in Congo Basin. Environ. Sci. Pol. 2010, 13, 498–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awono, A.; Ndoye, O.; Preece, L. Empowering Women’s Capacity for Improved Livelihoods in Non-Timber Forest Product Trade in Cameroon. IJSF 2010, 3, 151–163. [Google Scholar]

- Perez, M.R.; Ndoye, O.; Eyebe, A.; Ngono, D.L.; Pérez, M.R. A Gender Analysis of Forest Product Markets in Cameroon. Af. Today 2002, 49, 97–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, K.; Lapuyade, S. A Livelihood from the Forest: Gendered Visions of Social, Economic and Environmental change in Southern Cameroon. J. Int. Dev. 2001, 13, 1131–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, J. Just Famine Foods? What Contributions Can Underutilized Plants Make to Food Security? ISHS: Arusha, Tanzania, 2009; pp. 39–48. [Google Scholar]

- Van Huis, A.; van Itterbeeck, J.; Klunder, H.; Mertens, E.; Halloran, A.; Muir, G.; Vantomme, P. Edible Insects: Future Prospects for Food and Feed Security; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Vinceti, B.; Ickowitz, A.; Powell, B.; Kehlenbeck, K.; Termote, C.; Cogill, B.; Hunter, D. The Contribution of Forests to Sustainable Diets: Background paper for the International Conference on Forests for Food Security and Nutrition. Available online: http://www.fao.org/forestry/37132-051da8e87e54f379de4d7411aa3a3c32a.pdf (accessed on 30 October 2013).

- Smith, I.F.; Longvah, T. Mainstreaming the Use of Nutrient-Rich Underutilized Plant Food Resources in Diets Can Positively Impact Family Food and Nutrition Security–Data from Northeast India and West Africa. In Proceedings of International Symposium on Underutilized Plants for Food Security, Nutrition, Income and Sustainable Development; Jaenicke, H., Ganry, J., Hoeschle-Zeledon, I., Kahane, R., Eds.; ISHS: Arusha, Tanzania, 2009; pp. 375–384. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, M.P.; Sanyang, A. Underutilized Plants for Well-Being and Sustainable Development. In Proceedings of International Symposium on Underutilized Plants for Food Security, Nutrition, Income and Sustainable Development, Arusha, Tanzania, 3–6 March 2008; Jaenicke, H., Ganry, J.H.Z., Kahane, R., Eds.; ISHS: Arusha, Tanzania, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Tadele, Z. African Technology Development Forum Journal Special Issue: African Orphan Crops: Their Significance and Prospects for Improvement. Af. Technol. Dev. J. 2009, 6, 1–82. [Google Scholar]

- Afari-Sefa, V.; Tenkouano, A.; Ojiewo, C.O.; Keatinge, J.D.H.; Hughes, J.A. Vegetable breeding in Africa: constraints, complexity and contributions toward achieving food and nutritional security. Food Secur. 2011, 4, 115–127. [Google Scholar]

- Burchi, F.; Fanzo, J.; Frison, E. The Role of Food and Nutrition System Approaches in Tackling Hidden Hunger. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health. 2011, 8, 358–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grivetti, E.L.; Ogle, B.M. Value of traditional foods in meeting macro- and micronutrient needs: The wild plant connection. Nutr. Res. Rev. 2000, 13, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johns, T. Plant Biodiversity and Malnutrition: Simple Solutions to Complex Problems. AJFAND 2003, 3, 45–52. [Google Scholar]

- Cameroon: Comprehensive Food Security and Vulnerability Analysis. Available online: http://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/wfp250166.pdf (accessed on 4 November 2013).

- Roger, D.D.; Justin, E.J.; Francois-xavier, E. Nutritional properties of “Bush Meals” from North Cameroon’s Biodiversity. Adv. Appl. Sci. Res. 2012, 3, 1482–1493. [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell, D. The Political Economy of Urban Food Security in Sub-Saharan Africa. World Dev. 1999, 27, 1939–1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, M.J.; Garrett, J.L. The food price crisis and urban food (in)security. Environ. Urban. 2010, 22, 467–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The State of Food Insecurity in the World; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2012.

- United Nations World Urbanization Prospects: Cameroon; United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs: New York, NY, USA, 2011.

- IMF. Cameroon: Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper IMF Country; Report No. 10/257; International Monetary Fund: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Toye, J. Development with dearer food: Can the invisible hand guide us? J. Int. Dev. 2009, 21, 757–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appel, H.C. Walls and white elephants: Oil extraction, responsibility, and infrastructural violence in Equatorial Guinea. Ethnography 2012, 13, 439–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, N.M.; Jayne, T.S.; Chapoto, A.; Donovan, C. Putting the 2007/2008 global food crisis in longer-term perspective: Trends in staple food affordability in urban Zambia and Kenya. Food Pol. 2011, 36, 350–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmer, C.P. Reflections on food crises past. Food Pol. 2010, 35, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sneyd, L.Q.; Legwegoh, A.; Fraser, E.D.G. Food riots: Media perspectives on the causes of food protest in Africa. Food Secur. 2013, 5, 485–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, J.A. Understanding the Protest of February 2008 in Cameroon. Af. Today 2012, 58, 20–43. [Google Scholar]

- Cooksey, B. Marketing Reform? The Rise and Fall of Agricultural Liberalisation in Tanzania. Dev. Pol. Rev. 2011, 29, S57–S81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swan, S.H.; Hadley, S.; Cichon, B. Crisis Behind Closed Doors: Global Food Crisis and Local Hunger. J. Agrarian Change 2010, 10, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimova, R.; Gbakou, M. The Global Food Crisis: Disaster, Opportunity or Non-event? Household Level Evidence from Côte d’Ivoire. World Dev. 2013, 46, 185–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popkin, B.M. The Nutrition Transition and its Health Implications in Lower-Income Countries. Publ. Health Nutr. 1998, 5, 205–214. [Google Scholar]

- Popkin, B.M.; Gordon-Larsen, P. The nutrition transition: worldwide obesity dynamics and their determinants. Int. J. Obes. 2004, 28, S2–S9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blouin, C.; Hawkes, C.; Henson, S.; Drager, N.; Dube, L. Trade, Food, Diet. and Health: Perspectives and Policy Options; Wiley-Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Lang, T. Crisis? What Crisis? The Normality of the Current Food Crisis. J. Agrarian Change 2010, 10, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mennen, L.I.; Mbanya, J.C.C.; Cade, J.; Balkau, B.; Sharma, S.; Chungong, S.; Cruickshank, J.K. The habitual diet in rural and urban Cameroon. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2000, 54, 150–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Mbanya, J.C.; Cruickshank, K.; Cade, J.; Tanya, A.K.N.; Cao, X.; Hurbos, M.; Wong, M.R.K.M. Nutritional composition of commonly consumed composite dishes from the Central Province of Cameroon. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2007, 58, 475–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satia, J.A. Dietary acculturation and the nutrition transition: an overview. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metabol. 2010, 35, 219–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Environment Programme. Republic of Cameroon: Biodiversity Status Strategy and Action Plan; Convention on Biological Diversity: Yaounde, Cameroon, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- The Forests of the Congo Basin: State of the Forest 2006. Available online: http://carpe.umd.edu/Documents/2006/THE_FORESTS_OF_THE_CONGO_BASIN_State_of_the_Forest_2006.pdf (accessed on 30 October 2013).

- Guyer, J.I. The Food Economy and French Colonial Rule in Central Cameroun. J. Afr. Hist. 1978, 19, 577–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngoumou, T. Urban Food Provisioning in Cameroon: Regional Banana Plantain Network Linking Yaounde and the Villages of Koumou and Oban. In Economic Action in Theory and Practice: Anthropological Investigations; Wood, D.C., Ed.; Emerald: Bingley, UK, 2010; pp. 187–207. [Google Scholar]

- Analyse Globale de la Sécurité Alimentaire et de la Vulnérabilité au Cameroun 2011. Available online: http://documents.wfp.org/stellent/groups/public/documents/ena/wfp250164.pdf (accessed on 4 November 2013), in French.

- Dogan, Y. Traditionally used wild edible greens in the Aegean Region of Turkey. Acta Soc. Bot. Pol. 2012, 81, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somnasanc, P.; Kaell, K.; Moreno-black, G. Knowing, Gathering and Eating: knowledge and attitudes about wild food in an Isan village in Northeastern Thailand. J. Ethnobiol. 2000, 20, 197–216. [Google Scholar]

- Ogle, B.M.; Grivetti, E.L. Legacy of the cameleon edible wild plants of the Kingdom of Swaziland, South Africa. A Cultural, ecological and nutritional study. Part I. Introduction, objectives, methods, culture, landscape and diet. Ecol. Food Nutr. 1985, 16, 193–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, S.; Nebel, S.; Heinrich, M. Questionnaire surveys: methodological and epistemological problems for field-based ethnopharmacologists. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2005, 100, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J.; Deutsch, J. Food Studies: An Introduction to Research Methods; Berg: Oxford, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Legwegoh, A.F.; Hovorka, A.J. Assessing food insecurity in Botswana: the case of Gaborone. Dev. Pract. 2013, 23, 346–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robben, A.C.G.M.; Sluka, J.A. Ethnographic Fieldwork: An Anthropological Reader; Blackwell Publishing: Oxford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Scheyvens, R.; Storey, D. Development Fieldwork: A Practical Guide; Sage: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Baxter, J.; Eyles, J. Evaluating Qualitative Research in Social Geography: Establishing “Rigour” in Interview Analysis. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 1997, 22, 505–525. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, G. Onions are my Husband: Survival and Accumulation by West African Market Women; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Flynn, K.C. Food, Culture and Survival in an African City; Palgrave MacMillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Sultana, F. Reflexivity, Positionality and Participatory Ethics: Negotiating Fieldwork Dilemmas in International Research. Available online: http://www.acme-journal.org/vol6/FS.pdf (accessed on 30 October 2013).

- Hayes-Conroy, A. Feeling Slow Food: Visceral fieldwork and empathetic research relations in the alternative food movement. Geoforum 2010, 41, 734–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verpoorten, M.; Arora, A.; Stoop, N.; Swinnen, J. Self-reported food insecurity in Africa during the food price crisis. Food Pol. 2013, 39, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, D.; Caldwell, R. The Coping Strategies Index: Fields Methods Manual. Available online: http://home.wfp.org/stellent/groups/public/documents/manual_guide_proced/wfp211058.pdf (accessed on 4 November 2013).

- Koppert, G.J.A.; Dounias, E.; Froment, A.; Pasquet, P. Food Consumption in three forest populations of the Southern coastal area of Cameroon: Yassa, Mvae, Bakola. In Tropical Forests, People and Food: Biocultural interactions and applications to development; Hladik, C.M., Hladik, A., Linares, O.F., Pagezy, H., Semple, A., Hadley, S., Eds.; The Parthenon Publishing Group: Paris, France, 1993; pp. 295–310. [Google Scholar]

- Yengoh, G.; Tchuinte, A.; Armah, F.; Odoi, J. Impact of prolonged rainy seasons on food crop production in Cameroon. Mitig. Adap. Strateg. Glob. Chang. 2010, 15, 825–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCann, J. Stirring the Pot: A History of African Cuisine; Ohio University Press: Athens, Greece, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ancho-Chi, C. The Mobile Street Food Service Practice in the Urban Economy of Kumba, Cameroon. Singapore J. Trop. Geogr. 2002, 23, 131–148. [Google Scholar]

- Mbaku, J.M. Culture and Customs of Cameroon; Greenwood Press: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Tchoundjeu, Z.; Asaah, E.K.; Anegbeh, P.; Degrande, A.; Mbile, P.; Facheux, C.; Tsobeng, A.; Atangana, A.R.; Ngo-Mpeck, M.L.; Simons, A.J. Putting Participatory Domestication into Practice in West and Central Africa. For. Trees Livelihoods 2006, 16, 53–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngenge, T.S. The Institutional Roots of the “Anglophone Problem” in Cameroon. In Cameroon: Politics and Society in Critical Perspectives; University Press of America: Lanham, Maryland, 2003; pp. 61–86. [Google Scholar]

- Takougang, J.; Krieger, M. African State and Soceity in the 1990s: Cameroon’s Political Crossroads; Westview Press: Boulder, Colorado, CO, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Konings, P. Crisis and Neoliberal Reforms in AFRICA: Civil Society and Agro-Industry in Anglophone Cameroon’s Plantation Economy; Langaa RPCIG: Bamenda, Cameroon, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell, S.; Smith, M. Household Food Security: A Concpetual Review. In Household Food Security: Concepts, Indicators, Measurements: A Technical Review; UNICEF: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Isichei, E. A History of African Societies to 1870; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Sneyd, A. Cameroon: Let them eat local rice. Available online: http://www.africaportal.org/articles/2012/08/27/cameroon-let-them-eat-local-rice (accessed on 30 October 2013).

- Gockowski, J.; Mbazo’o, J.; Mbah, G.; Moulende, T.F. African traditional leafy vegetables and the urban and peri-urban poor. Food Pol. 2003, 28, 221–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abia, W.A.; Numfor, F.A.; Wanji, S.; Tcheuntue, F. Energy and nutrient contents of “ waterfufu and eru”. Available online: http://akobatglobalmedia.typepad.com/files/energy-and-nutrient-contents-of-waterfufu-and-eru.pdf (accessed on 4 November 2013).

- Ali, F.; Assanta, M.A.; Robert, C. Gnetum africanum: A Wild Food Plant from the African Forest with Many Nutritional and Medicinal Propertied. J. Med. Food 2011, 14, 1289–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamga, R.; Kouame, C.; Akyeampong, E. Vegetable consumption patterns in Yaoundé, Cameroon. Afr. J. Food Nutr. Sci. 2013, 13, 7399–7414. [Google Scholar]

- Gotor, E.; Irungu, C. The impact of Bioversity International’s African Leafy Vegetables programme in Kenya. Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2010, 28, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, F.; Eyzaguirre, P. African Leafy Vegetables: Their Role in the World Health Organization’s Global Fruit and Vegetables Initiative. Available online: http://www.bioline.org.br/request?nd07019 (accessed on 4 November 2013).

© 2013 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Sneyd, L.Q. Wild Food, Prices, Diets and Development: Sustainability and Food Security in Urban Cameroon. Sustainability 2013, 5, 4728-4759. https://doi.org/10.3390/su5114728

Sneyd LQ. Wild Food, Prices, Diets and Development: Sustainability and Food Security in Urban Cameroon. Sustainability. 2013; 5(11):4728-4759. https://doi.org/10.3390/su5114728

Chicago/Turabian StyleSneyd, Lauren Q. 2013. "Wild Food, Prices, Diets and Development: Sustainability and Food Security in Urban Cameroon" Sustainability 5, no. 11: 4728-4759. https://doi.org/10.3390/su5114728

APA StyleSneyd, L. Q. (2013). Wild Food, Prices, Diets and Development: Sustainability and Food Security in Urban Cameroon. Sustainability, 5(11), 4728-4759. https://doi.org/10.3390/su5114728