The Contribution of Multilateral Nuclear Approaches (MNAs) to the Sustainability of Nuclear Energy

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Past and Present Efforts for MNA

2.1. Efforts from 1940s to 1980s

| Proposals | Description and features of proposals | Results and reasons which prevented further implementation |

|---|---|---|

| Acheson-Lilienthal Report(1946) [2] |

| This concept of international control of nuclear material was succeeded by the Baruch Plan and the Eisenhower’s “Atoms for Peace” address. |

| Baruch Plan(1946) [3] | Followed but modified the Acheson-Lilienthal Report by adding prohibition of the development of nuclear-weapons capability by new states and punishment for violations. | Failed to gain support from the Soviet Union, since the U.S. intended to maintain its nuclear weapons monopoly. |

| Eisenhower’s “Atoms for Peace” Address (1953) [4] |

| Led to the establishment of the IAEA which acts as an “intermediary” of nuclear material and services supply. |

| Regional Nuclear Fuel Cycle Centers (RNFC)1975–1977 [6] |

| No follow-up action was taken, since fears of a plutonium economy had eased. |

| INFCE 1977–1980 [6] | Regarding MNA,

| Due to the disinclination of some countries to give up national control over nuclear fuel cycle, and the general lack of political will, INFCE studies resulted in no further pursuit of multilateral approaches. |

| IPS 1978–1982 [6] |

| No consensus was reached as states were unwilling to renounce sovereign control over nuclear technology and fuel. |

| ISFM 1979–1982 [6] | Discussed key elements about the international agreements which would need to be drawn up for an international SNF venture. They include technology, cost, and legal aspects related to spent fuel storage and transportation. | Could not proceed since specific storage locations could not be identified. |

| CAS 1980–1987 [6] | Discussed measures to ensure the reliable supply of nuclear material, equipment and technology, principles for international co-operation in the field of nuclear energy, emergency back-up mechanisms and an IAEA role | Unable to reach a consensus on principles for international co-operation on nuclear energy and for nuclear nonproliferation, as states were unwilling to renounce sovereign control over nuclear technology and fuel. |

2.2. Efforts from1990s to beginning to 2000s

| Proposals | Description and features of proposals | Results and reasons which prevented further implementation |

|---|---|---|

| International Monitored Storage System (IMRSS) Mid-1990s [7] | A concept of international storage of SNF and plutonium under international supervision. SNF could be retrieved at any time for peaceful use or disposal. | No actual negotiations took place. |

| Proposal by Marshall Islands 1994–1999 [7] | A proposal initiated by the Marshall Islands for disposing SNF and High Level Waste (HLW) in its territory. Revenue was to be used for nuclear test site remediation. | The initiative was terminated by strong opposition from the U.S. and other Pacific states. |

| Wake Island/Palmyra Island 1990s [7] |

|

|

| Non-Proliferation Trust1998 [7] |

|

|

| Pangea Project 1990–2000 [7] | A proposal led by Pangea Resources, a U.K.-based joint venture of British Nuclear Fuels Limited, Golder Associates and Swiss radioactive waste management entity Nagra, for disposing SNF and HLW in Western Australia | Pangea Resources abandoned the Project in 2000, due to opposition from the State of Western Australia and federal parliament. The Western Australian parliament passed a Bill to make it illegal to dispose of foreign high-level radioactive waste in the state without specific parliamentary approval. |

| A Russian technical storage or reprocessing facility 2001 [8] |

|

|

- • Due to a fact that the U.S.’s ability to control more than 80% of the world’s SNF, as in the case of MNA providing reprocessing and/or storage services, including U.S.-origin SNF, and transfer for such services, an authorization from the U.S. would be required, even if the U.S. itself is not be involved in the MNA.

- • The U.S. must negotiate a Section 123 agreement for nuclear cooperation with MNA members in order to give such permission.

2.3. Efforts from 2003 to the Present

| Proposals/initiatives | Description and features of proposals |

|---|---|

| “Multilateral Approaches to the Nuclear Fuel Cycle: an expert group’s report on MNA submitted to the Director General of the International Atomic Energy Agency” (INFCIRC/640, so called “Pellaud Report”) [ 10] |

|

| Reserve of nuclear fuel [ 11] (renamed as American Assured Fuel Supply (AFS) [12]) |

|

| Russia global nuclear power infrastructure (GNPI) [ 13] | The Russian Federation’s proposal, including a creation a system of international centers, providing uranium enrichment services, on a non discriminatory basis and under the control of the IAEA |

| U.S. Global Nuclear Energy Partnership (GNEP) [14] |

|

| Ensuring Security of Supply in the International Nuclear Fuel Cycle [15] |

|

| Concept of Multilateral Mechanism for Reliable Access to Nuclear Fuel [ 16] | The proposal by six enrichment services supplier States (the U.S., U.K., Russia, France, Germany and Netherlands) for two levels of enrichment assurance for customer states that have chosen to obtain suppliers on the international market and not to pursue sensitive fuel cycle activities |

| IAEA Fuel Bank [17] |

|

| Enrichment Bonds [20] (renamed as Nuclear Fuel Assurance (NFA) [21]) |

|

| International Uranium Enrichment Center (IUEC) at Angarsk and its LEU Reserve [22] |

|

| Multilateral Enrichment Sanctuary Project (MESP) [24] |

|

| Nuclear Fuel Cycle (EU-Non-paper) [25] |

|

| Japan’s Initiative for Mutual Assured Dependence [26] |

|

| Nuclear Islands: International Leasing of Nuclear Fuel Cycle Sites [27] |

|

3. Discussion on MNA Features

| Description of Features | |

|---|---|

| A | Nuclear nonproliferation: MNA members would need to follow the following norms;

|

| B | Assurance of supply:MNA would provide both front-end and back-end nuclear fuel cycle services, including;

|

| C | Access to technology:

|

| D | Multilateral involvement:

|

| E | Siting—choice of host state: Host states would;

|

| F | Legal aspects:

|

| G | Political and public acceptance:

|

| H | Economics: MNA facilities need to be

|

| I | Nuclear safety: MNA members would need to comply with the following international nuclear safety norms;

|

| J | Nuclear liability: In particular, host states of MNA facilities are requested to;

|

| K | Transportation:

|

| L | Geopolitics:

|

3.1. (A) Nuclear Nonproliferation and (B) Assurance of Supply

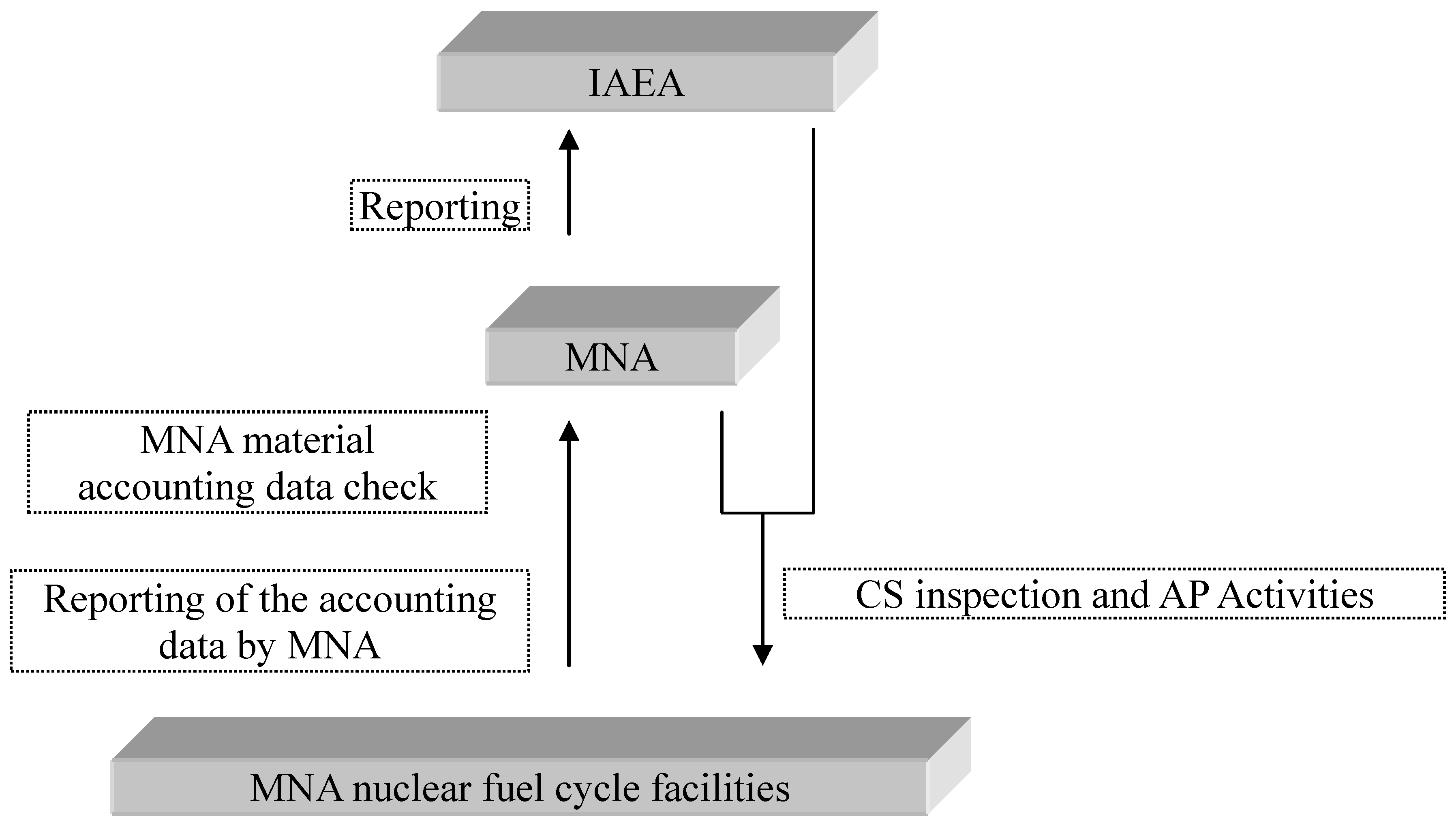

3.1.1. (A) Nuclear Nonproliferation

3.1.2. (B) Assurance of Supply of Nuclear Materials and Fuel Cycle Services

3.2. (C) Siting-Choice of Host States

3.3. (D) Access to Technologies and (E) Multilateral Involvement

3.4. (F) Legal Aspects

3.5. (G) Political and Public Acceptance

3.6. (H) Economics

3.7. (I) Nuclear Safety

3.8. (J) Nuclear Liability

3.9. (K) Transportation

3.10. (L) Geopolitics

4. Conclusion

Acknowledgments

References and Notes

- Declaration on Atomic Bomb. Washington, DC, USA, 15 November, 1945. Available online: http://www.nuclearfiles.org/menu/key-issues/nuclear-energy/history/dec-truma-atlee-king_1945-11-15.htm (accessed on 26 June 2012).

- A Report on the International Control of Atomic Energy; U.S. Government Printing Office: Washington, DC, USA, 16 March 1946. Available online: http://www.learnworld.com/ZNW/LWText.Acheson-Lilienthal.html (accessed on 26 June 2012). Prepared for the Secretary of State’s Committee on Atomic Energy.

- The Baruch Plan. New York, NY, USA, 14 June 1946. Available online: http://www.atomicarchive.com/Docs/Deterrence/BaruchPlan.shtml (accessed on 26 June 2012).

- Dwight D. Eisenhower. Address by Mr. Dwight D. Eisenhower, President of the United States of America, to the 470th Plenary Meeting of the United Nations General Assembly. New York, NY, USA, 8 December 1953. Available online: http://www.iaea.org/About/history_speech.html (accessed on 26 June 2012).

- Yudin, Y. Multilateralization of the Nuclear Fuel Cycle: Assessing the Existing Proposals; UNIDIR/2009/4; United Nations Institute for Disarmament Research (UNIDIR): Geneva, Switzerland, 2009; p. 6. Available online: http://unidir.org/pdf/activites/pdf2-act439.pdf (accessed on 26 June 2012).

- IAEA. Developing Multinational Radioactive Waste Repositories: Infrastructural Framework and Scenarios of Cooperation; IAEA-TECDOC-1413; IAEA: Vienna, Austria, October 2004; pp. 8–11. Available online: http://www-pub.iaea.org/MTCD/publications/PDF/te_1413_web.pdf (accessed on 26 June 2012).

- IAEA. Developing Multinational Radioactive Waste Repositories: Infrastructural Framework and Scenarios of Cooperation; IAEA-TECDOC-1413; IAEA: Vienna, Austria, October 2004; pp. 9–10. Available online: http://www-pub.iaea.org/MTCD/publications/PDF/te_1413_web.pdf (accessed on 26 June 2012).

- Chuen, C. Russian Spent Nuclear Fuel. Nuclear Threat Initiative, 1 February 2003. Available online: http://www.nti.org/analysis/articles/russian-spent-nuclear-fuel/ (accessed on 26 June 2012).

- ElBaradei, M. Towards a safer world. The Economist. 16 October 2003. Available online: http://www.economist.com/node/2137602 (accessed on 26 June 2012).

- IAEA, Multilateral Approaches to the Nuclear Fuel Cycle: Expert Group Report submitted to the Director General of the IAEA; INFCIRC/640; IAEA: Vienna, Austria, 22 February 2005.

- IAEA, Communication Dated 28 September 2005 from the Permanent Mission of the United States of America to the Agency; INFCIRC/659; IAEA: Vienna, Austria, 29 September 2005.

- US Federal Register. 18 August 2011, US Federal Register: Washington, DC, USA, 1360; 76, 51359–51360(accessed on 26 June 2012). Available online: http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2011-08-18/pdf/2011-21069.pdfNo. 160.

- IAEA, Communication received from the Resident Representative of the Russian Federation to the Agency transmitting the text of the Statement of the President of the Russian Federation on the Peaceful Use of Nuclear Energy; INFCIRC/667; IAEA: Vienna, Austria, 8 February 2006.

- Department of Energy Announces New Nuclear Initiative. 6 February 2006. Available online: http://energy.gov/articles/department-energy-announces-new-nuclear-initiative (accessed on 26 June 2012).

- World Nuclear Association (WNA). Ensuring Security of Supply in the International Nuclear Fuel Cycle. 12 May 2006. Available online: http://www.world-nuclear.org/reference/pdf/security.pdf (accessed on 26 June 2012).

- Timbie, J. Six-Country Concept for a Multilateral Mechanism for Reliable Access to Nuclear Fuel. Available online: http://media.hoover.org/sites/default/files/documents/0817948429_147.pdf (accessed on 26 June 2012). Presented 21 September 2006 by James Timbie on behalf of France, Germany, Russia, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, and the United States..

- Nuclear Threat Initiative. NTI Commits $50 Million to create IAEA Nuclear Fuel Bank. 19 September 2006. Available online: http://www.nti.org/newsroom/news/nti-commits-50-million-iaea-nuclear-fuel-bank/ (accessed on 26 June 2012).

- IAEA, GOV/2010/67. Assurance of Supply; IAEA: Vienna, Austria, 26 November 2010; p. 3.

- WNA. IAEA approves global nuclear fuel bank. 6 December 2010. Available online: http://www.world-nuclear-news.org/ENF-IAEA_approves_global_nuclear_fuel_bank-0612105.html (accessed on 26 June 2012).

- IAEA, Communication Dated 30 May 2007 from the Permanent Mission of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland to the IAEA concerning Enrichment Bonds—A Voluntary Scheme for Reliable Access to Nuclear Fuel; INFCIRC/707; IAEA: Vienna, Austria, 4 June 2007.

- IAEA, Communication Dated 19 May 2011 received from the Resident Representative of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland to the Agency regarding Assurance of Supply of Enrichment Services and Low Enriched Uranium for Use in Nuclear Power Plants; INFCIRC/818; IAEA: Vienna, Austria, 27 May 2011.

- IAEA, Communication Received from the Resident. Representative of the Russian Federation to the IAEA on the Establishment, Structure and Operation of the International Uranium Enrichment Centre; INFCIRC/708; IAEA: Vienna, Austria, 8 June 2007.

- IAEA. Russia Inaugurates World’s First Low Enriched Uranium Reserve. 17 December 2010. Available online: http://www.iaea.org/newscenter/news/2010/leureserve.html (accessed on 26 June 2012).

- IAEA, Communication dated 30 May 2008 received from the Permanent Mission of the Federal Republic of Germany to the Agency with regard to the German proposal for a Multilateral Enrichment Sanctuary Project; INFCIRC/727; IAEA: Vienna, Austria, 30 May 2008.

- Rauf, T.; Vovchok, Z. Fuel for Thought; IAEA Bulletin 49-2; IAEA: Vienna, Austria, March 2008; p. 63. Available online: http://www.iaea.org/Publications/Magazines/Bulletin/Bull492/49204845963.pdf (accessed on 26 June 2012).

- Japan’s Initiative for Mutual Assured Dependence. Towards Nuclear Disarmament and Non-proliferation: 10 Proposals from Japan; Center for Global Partnership of Japan Foundation, Toshiba International Foundation, Pugwash USA, Pugwash Japan Tokyo: Japan, December 2009; p. 16. Available online: http://a-mad.org/download/A-MAD_EN-JPN.pdf (accessed on 26 June 2012).

- Paine, C.E.; Cochran, T.B. Nuclear islands: International leasing of nuclear fuel cycle sites to provide enduring assurance of peaceful use. Nonproliferation Review. 2010, 17, pp. 441–474. Available online: http://cns.miis.edu/npr/pdfs/npr_17-3_paine_cochran.pdf (accessed on 26 June 2012).

- NTI. NTI commits $50 million to create IAEA nuclear fuel bank. 19 September 2006. Available online: http://www.nti.org/newsroom/news/nti-commits-50-million-iaea-nuclear-fuel-bank/ (accessed on 26 June 2012).

- IAEA. Multinational fuel bank proposal reaches key milestone. IAEA Top Stories & Features. 6 March 2009. Available online: http://www.iaea.org/newscenter/news/2009/fbankmilestone.html (accessed on 26 June 2012).

- Yudin, Y. Multilateralization of the Nuclear Fuel Cycle: The Need to Build Trust; UNIDIR/2010/1; United Nations Institute for Disarmament Research (UNIDIR): Geneva, Switzerland, 2010; pp. 7–11. Available online: http://www.unidir.org/pdf/ouvrages/pdf-1-978-92-9045-197-6-en.pdf (accessed on 24 July 2012).

- IAEA, Communication Received from the Permanent Mission of the Netherlands regarding Certain Member States’ Guidelines for the Export of Nuclear Material, Equipment and Technology; INFCIRC/254/Rev.10/Part 1; IAEA: Vienna, Austria, 26 July 2011; Paragraph 7 (b).

- U.S. Committee on the Internationalization of the Civilian Nuclear Fuel CycleCommittee on International Security and Arms Control, Policy and Global AffairsNational Academy of Sciences and National Research CouncilInternationalization of the Nuclear Fuel Cycle; Goals, Strategies, and Challenges; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2008; p. 4.

- Treaty on a Nuclear Weapon Free Zone in Central Asia; Semipalatinsk, Kazakhstan, 8 September 2006. Available online: http://cns.miis.edu/stories/pdf_support/060905_canwfz.pdf (accessed on 9 August 2012). Paragraph 2 of Article 3.

- Law of Mongolia on its Nuclear-Weapon-Free Status. 3 February 2000. Available online: http://www.opanal.org/NWFZ/Mongolia/Mlaw_en.html (accessed on 9 August 2012). Article 4.1.4..

- Joint Declaration on the Denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula. Available online: http://www.fas.org/news/dprk/1992/920219-D4129.htm (accessed on 9 August 2012). Entry into force on 19 February 1992.

- 123 Agreements for Peaceful Cooperation. NNSA/USA. Available online: http://nnsa.energy.gov/aboutus/ourprograms/nonproliferation/treatiesagreements/123agreementsforpeacefulcooperation (accessed on 29 June 2012). Pursuant to Section 6 of the Taiwan Relations Act, P.L. 96-8, 93 Stat. 14, and Executive Order 12143, 44 F.R. 37191, all agreements concluded with the Taiwan authorities prior to January 1, 1979 are administered on a nongovernmental basis by the American Institute in Taiwan, a non-profit District of Columbia corporation, and constitute neither recognition of Taiwan authorities nor the continuation of any official relationship with Taiwan.

- Mainichi scoop on Mongolia’s nuclear plans highlights problems in dealing with waste. The Mainichi. 13 March 2012. Available online: http://mainichi.jp/english/english/perspectives/news/20120313p2a00m0na003000c.html (accessed on 26 June 2012).

- IAEA. IAEA Action Plan on Nuclear Safety; IAEA: Vienna, Austria, 13 September 2011; p. 5. Available online: http://www.iaea.org/newscenter/news/2011/actionplan.html (accessed on 26 June 2012).

- WNA. Uranium and Nuclear Power in Kazakhstan. Available online: http://www.world-nuclear.org/info/inf89.html (accessed on 26 June 2012).

- WNA. Uranium in Mongolia. Available online: http://www.world-nuclear.org/info/inf125-mongolia.html (accessed on 26 June 2012).

- WNA. Russia’s Nuclear Fuel Cycle. Available online: http://www.world-nuclear.org/info/inf45a_Russia_nuclear_fuel_cycle.html (accessed on 26 June 2012).

© 2012 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open-access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Tazaki, M.; Kuno, Y. The Contribution of Multilateral Nuclear Approaches (MNAs) to the Sustainability of Nuclear Energy. Sustainability 2012, 4, 1755-1775. https://doi.org/10.3390/su4081755

Tazaki M, Kuno Y. The Contribution of Multilateral Nuclear Approaches (MNAs) to the Sustainability of Nuclear Energy. Sustainability. 2012; 4(8):1755-1775. https://doi.org/10.3390/su4081755

Chicago/Turabian StyleTazaki, Makiko, and Yusuke Kuno. 2012. "The Contribution of Multilateral Nuclear Approaches (MNAs) to the Sustainability of Nuclear Energy" Sustainability 4, no. 8: 1755-1775. https://doi.org/10.3390/su4081755

APA StyleTazaki, M., & Kuno, Y. (2012). The Contribution of Multilateral Nuclear Approaches (MNAs) to the Sustainability of Nuclear Energy. Sustainability, 4(8), 1755-1775. https://doi.org/10.3390/su4081755