Lost Fishing Gear Generated by Artisanal Fishing Along the Moroccan Mediterranean Coast: Quantities and Causes of Loss

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- (i)

- The first part covered fishing activity, including the number of trips (fishing effort) and the types of gear used, as well as their periods of use.

- (ii)

- The second part concerned the annual quantities of gear loss per boat.

- (iii)

- The final section focused on the primary causes of gear loss associated with each specific gear type used.

2.1. Data Collection

- (i)

- Strict anonymity was guaranteed to the fishermen to dissociate the data from any regulatory enforcement.

- (ii)

- Technical characteristics of fishing gear were validated through direct field measurements, including the weighing of gear components, allowing standardization of reported losses.

- (iii)

- Collaboration with local fishermen’s associations facilitated trust and contextual verification of respondents’ active fishing status.

- (iv)

- The completed questionnaires were checked for completeness and consistency, and any responses that were ambiguous were clarified with the respondents wherever possible.

- (v)

- After the interviews were completed, a comparison and cross-check of the responses provided by fishers at the same fishing site was necessary in order to identify any potential discrepancies.

- (vi)

- Quantification relied on average values and cautious estimates to quantify lost fishing gear, given the self-reported nature of part of the data.

Fishing Gear Used, Types of Lost Fishing Gear, and Main Causes of Loss

2.2. Statistical Analysis

2.3. Study Limitations

3. Results and Discussion

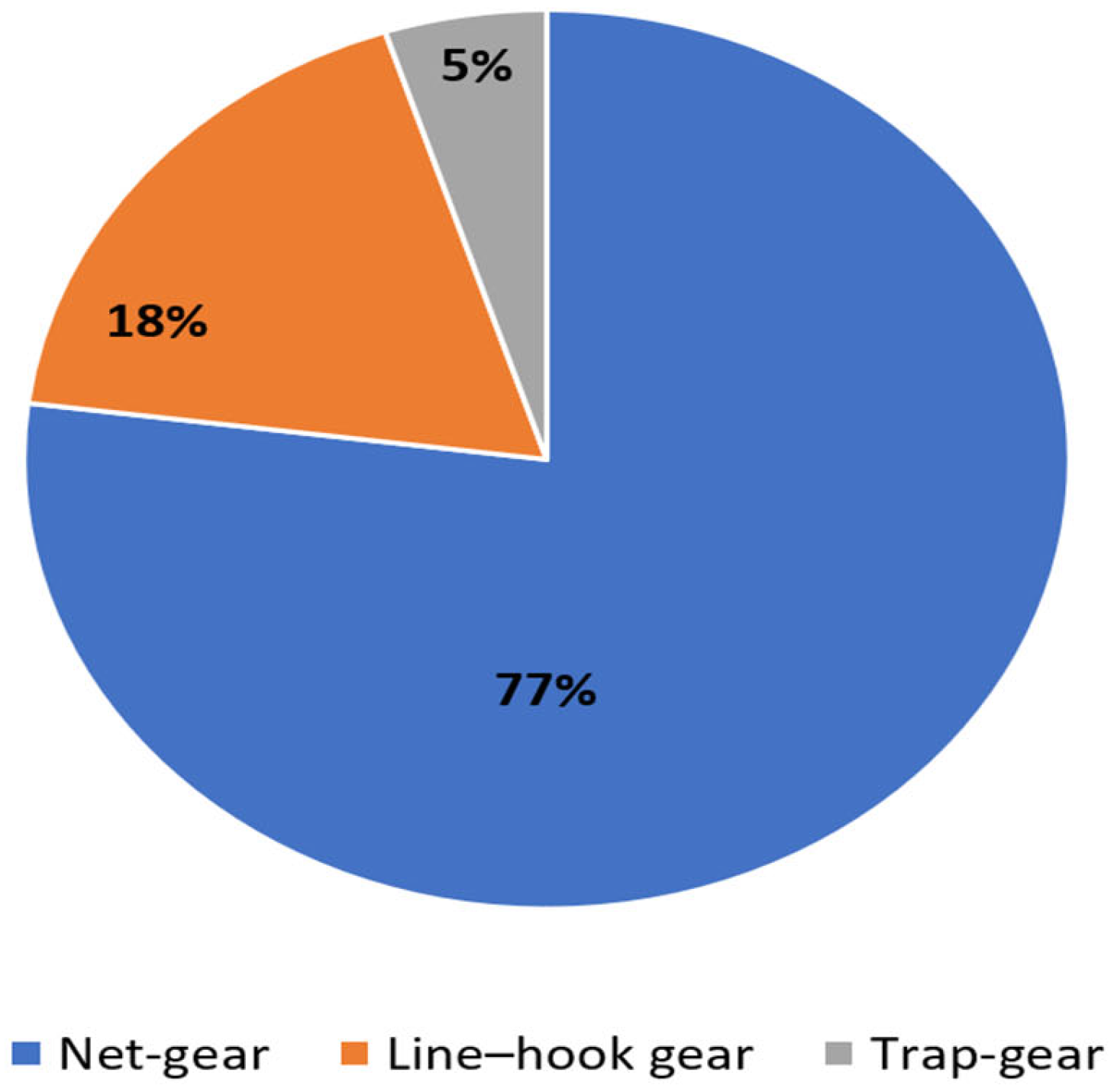

3.1. Types of Fishing Gear

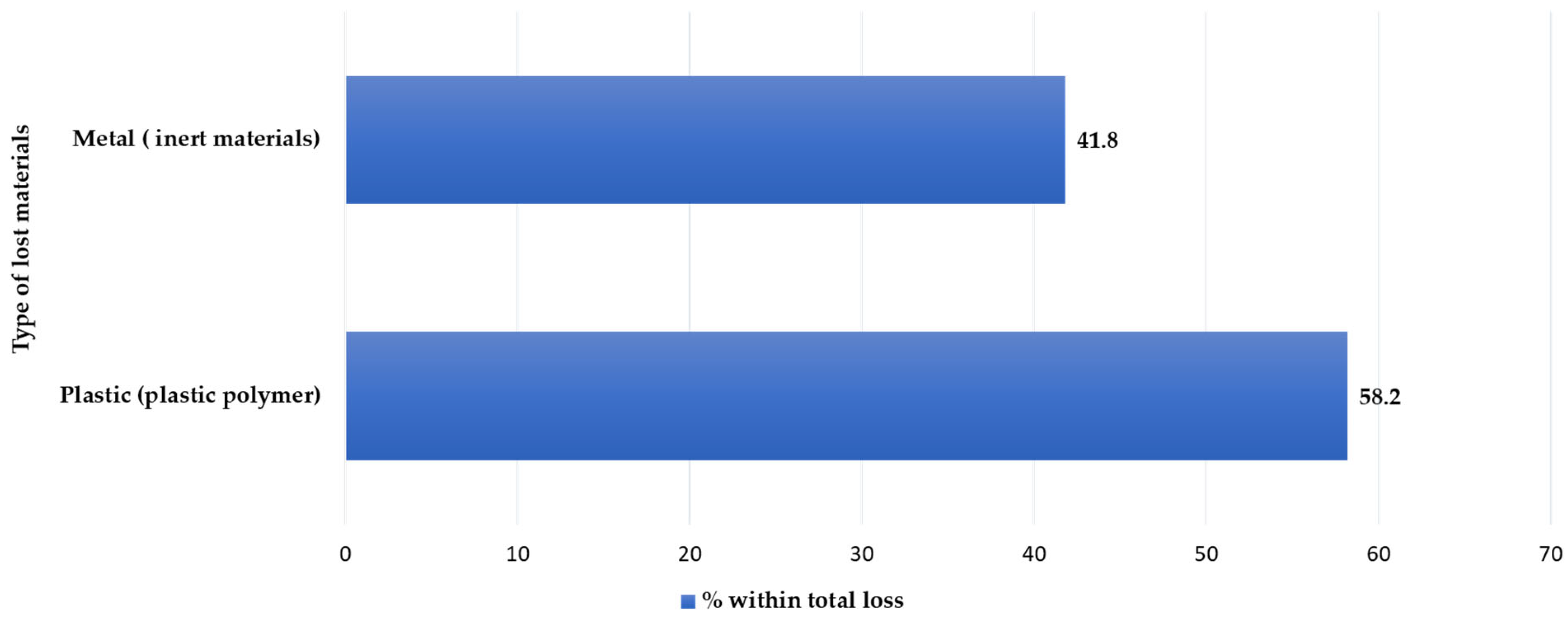

3.2. Estimates of Fishing Gear Loss

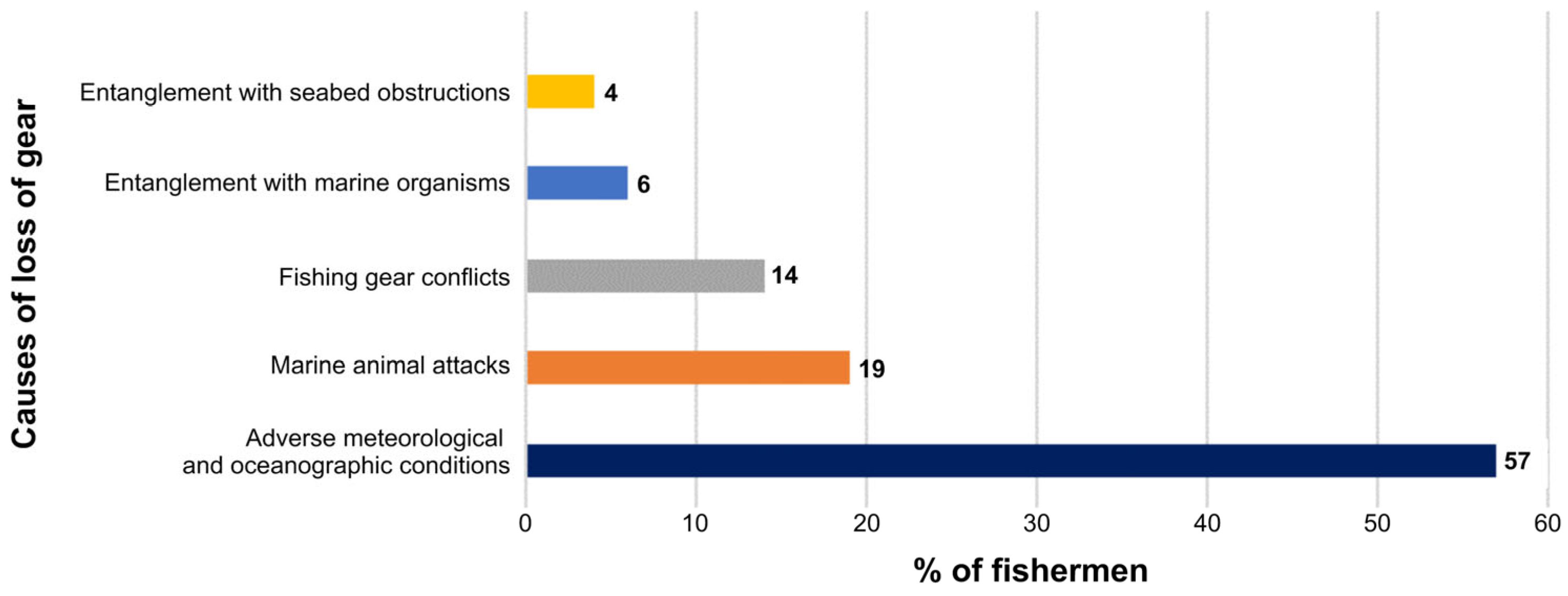

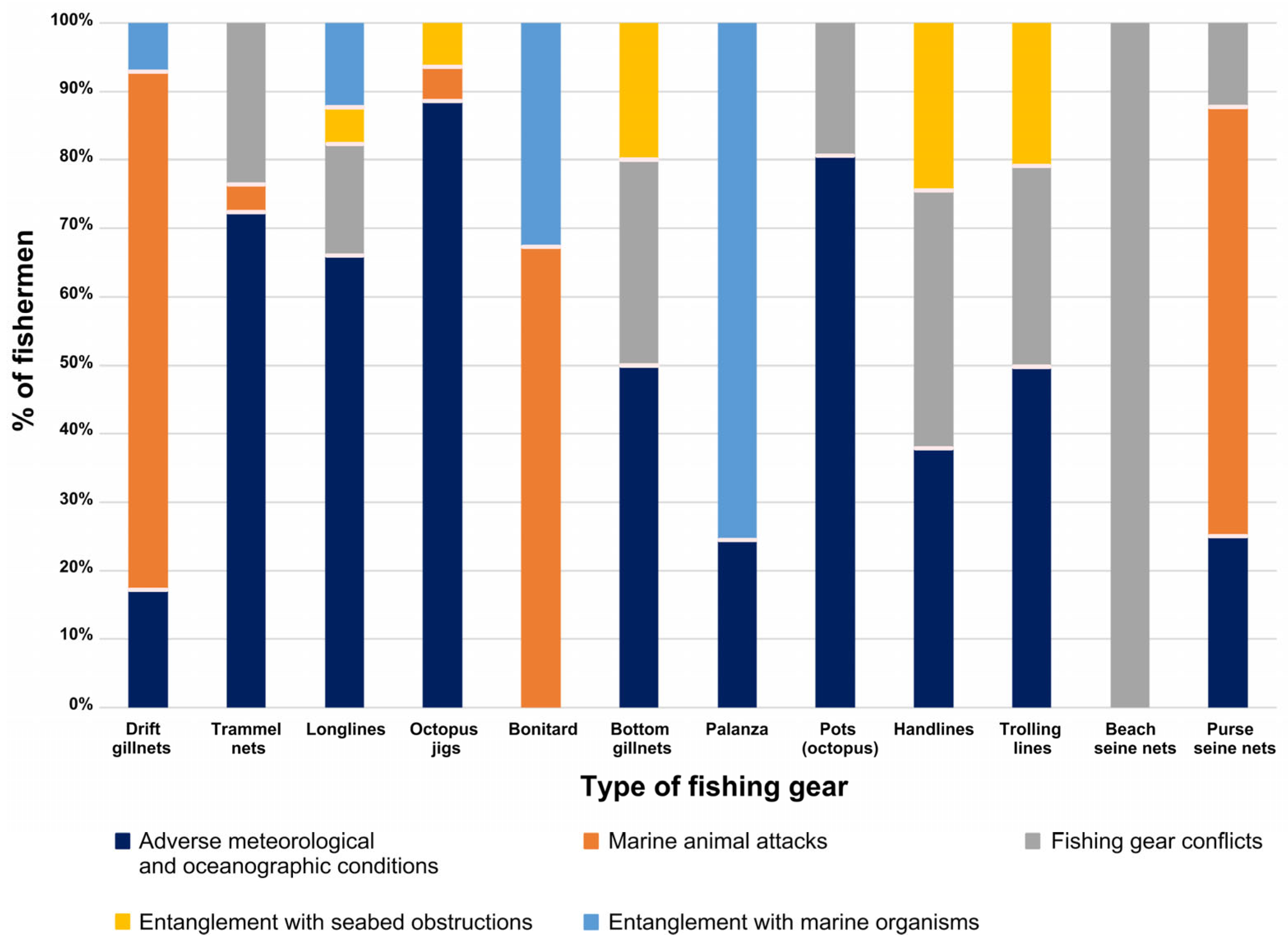

3.3. Causes of Fishing Gear Losses

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ALDFG | Abandoned, Lost, and Discarded Fishing Gear |

| LFG | Lost Fishing Gear |

| NGOs | Non-Governmental Organizations |

References

- Bergmann, M.; Gutow, L.; Klages, M. Marine Anthropogenic Litter; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 18–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cózar, A.; Sanz-Martín, M.; Martí, E.; González-Gordillo, J.I.; Ubeda, B.; Gálvez, J.Á.; Irigoien, X.; Duarte, C.M. Plastic Accumulation in the Mediterranean Sea. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0121762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jambeck, J.R.; Geyer, R.; Wilcox, C.; Siegler, T.R.; Perryman, M.; Andrady, A.; Narayan, R.; Law, K.L. Plastic waste inputs from land into the ocean. Science 2015, 347, 768–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thushari, G.G.N.; Senevirathna, J.D.M. Plastic pollution in the marine environment. Heliyon 2020, 6, e04709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FAO. Voluntary Guidelines for Securing Sustainable Small-Scale Fisheries in the Context of Food Security and Poverty Eradication; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2015; 39p. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Report of the Technical Consultation on Marking of Fishing Gear; Fisheries and Aquaculture Report No. 1236; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2018; 39p. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2022: Towards Blue Transformation; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2022; 32p. [Google Scholar]

- UNEP. From Pollution to Solution: A Global Assessment of Marine Litter and Plastic Pollution; United Nations Environment Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2021; Available online: https://www.unep.org/beatpollution/forms-pollution/marine-and-coastal (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- MacFadyen, G.; Huntington, T.; Cappell, R. Abandoned, Lost or Otherwise Discarded Fishing Gear; Technical Paper No. 523; UNEP/FAO: Rome, Italy, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Duhec, A.; Jeanne, R.; Maximenko, N.; Hafner, J. Composition and potential origin of marine debris stranded in the Western Indian Ocean on remote Alphonse Island, Seychelles. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2015, 58, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilman, E. Status of international monitoring and management of abandoned, lost and discarded fishing gear and ghost fishing. Mar. Policy 2015, 60, 225–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NOAA Marine Debris Program. Report on the Impacts of “Ghost Fishing” via Derelict Fishing Gear; NOAA Marine Debris Program: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2015; p. 25. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, K.; Hardesty, B.D.; Wilcox, C. Estimates of fishing gear loss rates at a global scale: A literature review and meta-analysis. Fish Fish. 2019, 20, 1218–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suka, R.; Huntington, B.; Morioka, J.; O’Brien, K.; Acoba, T. Successful application of a novel technique to quantify negative impacts of derelict fishing nets on Northwestern Hawaiian Island reefs. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2020, 157, 111312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuczenski, B.; Vargas Poulsen, C.; Gilman, E.L.; Musyl, M.; Geyer, R.; Wilson, J. Plastic gear loss estimates from remote observation of industrial fishing activity. Fish Fish. 2022, 23, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebreton, L.; Slat, B.; Ferrari, F.; Sainte-Rose, B.; Aitken, J.; Marthouse, R.; Hajbane, S.; Cunsolo, S.; Schwarz, A.; Levivier, A.; et al. Evidence that the Great Pacific Garbage Patch is rapidly accumulating plastic. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 4666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, S.N.; Edwin, L.; Chinnadurai, S.; Harsha, K.; Salagrama, V.; Prakash, R.; Prajith, K.K.; Diei-Ouadi, Y.; He, P.; Ward, A. Food and Gear Loss from Selected Gillnet and Trammel Net Fisheries of India; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Masroori, H.; Al-Oufi, H.; McShane, P. Causes and Mitigations on Trap Ghost Fishing in Oman: Scientific Approach to Local Fishers’ Perception. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2009, 4, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, K.; Hardesty, B.D.; Vince, J.Z.; Wilcox, C. Global Causes, Drivers, and Prevention Measures for Lost Fishing Gear. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8, 690447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephen, H. Legal Aspects of Abandoned, Lost or Otherwise Discarded Fishing Gear; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Ed.; Food & Agriculture Org: Rome, Italy, 2022; Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=fr&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=Legal+aspects+of+abandoned%2C+lost+or+otherwise+discarded+fishing+gear&btnG= (accessed on 6 August 2025).

- Daniel, D.B.; Thomas, S.N. Derelict fishing gear abundance, its causes and debris management practices—Insights from the fishing sector of Kerala, India. Mar. Policy 2023, 148, 105429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stelfox, M.; Hudgins, J.; Sweet, M. A review of ghost gear entanglement amongst marine mammals, reptiles and elasmobranchs. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2016, 111, 6–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nama, S.; Prusty, S. Ghost gear: The most dangerous marine litter endangering our ocean. Food Sci. Rep. 2021, 2, 34–38. [Google Scholar]

- Ayaz, A.; Acarli, D.; Altinagac, U.; Ozekinci, U.; Kara, A.; Ozen, O. Ghost fishing by monofilament and multifilament gillnets in Izmir Bay, Turkey. Fish. Res. 2006, 79, 267–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Good, T.; June, J.; Etnier, M.; Broadhurst, G. Derelict fishing nets in Puget Sound and the Northwest Straits: Patterns and threats to marine fauna. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2010, 60, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abid, S.; Abdul Razzaque, S.; Ahmed, S. Improving Monitoring and Conservation Strategies in Pakistani Waters: Addressing Impacts of NonBiodegradable Fishing Gear on Marine Turtle Health. 2023. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=fr&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=Improving+Monitoring+and+Conservation+Strategies+in+Pakistani+Waters%3A+Addressing+Impacts+of+NonBiodegradable+Fishing+Gear+on+Marine+Turtle+Health&btnG= (accessed on 9 August 2025).

- Pandey, A.; Kawade, S.; Sedyaaw, P.; Aitwar, V.; Chopra, P.; Raj Keer, D.; Nalwade, P. Ghost Fishing Gear: An Overlooked Threat in Marine Debris Management. J. Ecol. Environ. Sci. 2025, 51, 351–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilcox, C.; Mallos, N.J.; Leonard, G.H.; Rodriguez, A.; Hardesty, B.D. Using expert elicitation to estimate the impacts of plastic pollution on marine wildlife. Mar. Policy 2016, 65, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilman, E.; Humberstone, J.; Wilson, J.R.; Chassot, E.; Jackson, A.; Suuronen, P. Matching fishery-specific drivers of abandoned, lost and discarded fishing gear to relevant interventions. Mar. Policy 2022, 141, 105097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilman, E.; Chopin, F.; Suuronen, P.; Kuemlangan, B. Abandoned, Lost and Discarded Gillnets and Trammel Nets: Methods to Estimate Ghost Fishing Mortality, and Status of Regional Monitoring and Management; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2016; p. 96. [Google Scholar]

- Gilman, E.; Musyl, M.; Suuronen, P.; Chaloupka, M.; Gorgin, S.; Wilson, J.; Kuczenski, B. Highest risk abandoned, lost and discarded fishing gear. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 7195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNEP; MAP. Regional Survey on Abandoned, Lost or Discarded Fishing Gear & Ghost Nets in the Mediterranean Sea—A Contribution to the Implementation of the UNEP/MAP Regional Plan on Marine Litter Management in the Mediterranean; United Nations Environment Programme: Athens, Greece, 2015; p. 23. Available online: https://wedocs.unep.org/handle/20.500.11822/9920 (accessed on 8 November 2025).

- Iburahim, A.; Ramteke, K.; Kumar, R.; Mano, A.M.R.; Bhole, P. Abandoned, Lost, and Discarded Fishing Gear (ALDFG): A Metanalysis of Global Trends, Environmental Impact, and Scientific Advancements. In Proceedings of the 2nd Indian Fisheries Outlook 2025 on “Envisaging Blue Transformation in Indian Fisheries and Aquaculture”, Berhampur, India, 12–14 July 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Ayaz, A.; Ünal, V.; Acarli, D.; Altınağaç, U. Fishing gear losses in the Gökova Special Environmental Protection Area (SEPA), eastern Mediterranean, Turkey. J. Appl. Ichthyol. 2010, 26, 416–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez, C.; Resaikos, V. Chasing Ghosts: Evidence-Based Management of Abandoned Fishing Gear in the Eastern Mediterranean. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boussellaa, W.; Bradai, M.N.; Mallat, H.; Enajjar, S.; Saidi, B.; Jribi, I. Ghost Gear in the Gulf of Gabès (Tunisia): An Urgent Need for a Conservation Code of Conduct. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaouar, H.; Boussellaa, W.; Jribi, I. Ghost Gears in the Gulf of Gabès: Alarming Situation and Sustainable Solution Perspectives. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idrissi, M.M.; Houssa, R.; Slimani, A.; Essekelli, D. Situation Actuelle de la Pêche Artisanale en Méditerranée Marocaine; FAO: Rome, Italy, 1999; 25p. [Google Scholar]

- Idrissi, M.M.; Zahri, Y.; Houssa, R.; Abdelaoui, B.; Ouamari, N.E. Pêche Artisanale dans la Lagune de Nador, Maroc: Exploitation et Aspects Socio-Économiques; Institut National de Recherche Halieutique—Centre Régional de Nador: Nador, Morocco, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Najih, M.; Berday, N.; Abdeljaouad, L.; Nachite, D.; Zahri, Y. Situation de la pêche aux petits métiers après l’ouverture du nouveau chenal dans la lagune de Nador. Rev. Mar. Sci. Agron. Vét. 2015, 3, 19–30. [Google Scholar]

- Darasi, F.; Awadh, H.; Aksissou, M. Des engins de pêche artisanale utilisés en partie ouest Méditerranée marocaine. Int. J. Innov. Sci. Res. 2019, 40, 276–286. [Google Scholar]

- DPM. Rapport d’Activité du Département de la Pêche Maritime; Ministère de l’agriculture, de la Pêche Maritime, du Développement Rural et des Eaux et Forêts: Rabat, Morocco, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Bouzekry, A.; Mghili, B.; Aksissou, M. Addressing the challenge of marine plastic litter in the Moroccan Mediterranean: A citizen science project with schoolchildren. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2022, 184, 114167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mghili, B.; Keznine, M.; Aksissou, M. The impacts of abandoned, discarded and lost fishing gear on marine biodiversity in Morocco. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2023, 239, 106593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mghili, B.; Keznine, M.; Hasni, S.; Aksissou, M. Abundance, composition and sources of benthic marine litter trawled-up in the fishing grounds on the Moroccan Mediterranean coast. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 2023, 63, 103002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, P.; Chopin, F.; Suuronen, P.; Ferro, R.D.T.; Lansley, J. Classification and Illustrated Definition of Fishing Gears; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Kim, P.; Jeong, S.; Lee, K.; Oh, W. Physical Properties of Biodegradable Fishing Net in Accordance with Heat-Treatment Conditions for Reducing Ghost Fishing. Turk. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2019, 20, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelms, S.E.; Duncan, E.M.; Patel, S.; Badola, R.; Bhola, S.; Chakma, S.; Chowdhury, G.W.; Godley, B.J.; Haque, A.B.; Johnson, J.A.; et al. Riverine plastic pollution from fisheries: Insights from the Ganges River system. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 756, 143305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loulad, S.; Houssa, R.; Rhinane, H.; Boumaaz, A.; Benazzouz, A. Spatial distribution of marine debris on the seafloor of Moroccan waters. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2017, 124, 303–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Par Bazairi, H.; Mellouli, M.; Aghnaj, A.; El Khalidi, K.; Limam, A. (Eds.) Rapport Synthétique de la Liste «Prioritaire» des Sites Méritant une Protection au Niveau des Côtes Méditerranéennes au Maroc; CAR/ASP-Projet MedMPAnet: Tunis, Tunisia, 2012; 60p. [Google Scholar]

- SECPM. La Mer en Chiffre 2024; SECPM: Rabat, Morocco, 2024; Available online: http://www.abhatoo.net.ma/maalama-textuelle/developpement-economique-et-social/developpement-economique/peche/peche-generalites/la-mer-en-chiffres-annee-2024 (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Battaglia, P.; Romeo, T.; Consoli, P.; Scotti, G.; Andaloro, F. Characterization of the artisanal fishery and its socio-economic aspects in the central Mediterranean Sea (Aeolian Islands, Italy). Fish. Res. 2010, 102, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falautano, M.; Castriota, L.; Cillari, T.; Vivona, P.; Finoia, M.G.; Andaloro, F. Characterization of artisanal fishery in a coastal area of the Strait of Sicily (Mediterranean Sea): Evaluation of legal and IUU fishing. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2018, 151, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, K.; Hardesty, B.D.; Vince, J.; Wilcox, C. Global estimates of fishing gear lost to the ocean each year. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabq0135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, A.; Randall, P.; Sivyer, D.; Binetti, U.; Lokuge, G.; Munas, M. Abandoned, lost or otherwise discarded fishing gear (ALDFG) in Sri Lanka—A pilot study collecting baseline data. Mar. Policy 2023, 148, 105386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mengo, E.; Randall, P.; Larsonneur, S.; Burton, A.; Hegron, L.; Grilli, G.; Russell, J.; Bakir, A. Fishers’ views and experiences on abandoned, lost or otherwise discarded fishing gear and end-of-life gear in England and France. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2023, 194, 115372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Masroori, H. Trap Ghost Fishing Problem in the Area Between Muscat and Barka (Sultanate of Oman): An Evaluation Study; Sultan Qaboos University: Muscat, Oman, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- WWF. Stop the Flood of Plastic—A Guide for Policy-Makers in Morocco; Report: 199; World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF): Gland, Switzerland, 2019; Available online: https://wwfeu.awsassets.panda.org/downloads/05062019_wwf_marocco_guidebook.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Vlachogianni, T.; Fortibuoni, T.; Ronchi, F.; Zeri, C.; Mazziotti, C.; Tutman, P.; Varezić, D.B.; Palatinus, A.; Trdan, Š.; Peterlin, M.; et al. Marine litter on the beaches of the Adriatic and Ionian Seas: An assessment of their abundance, composition and sources. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2018, 131, 745–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GESAMP. Sea-Based Sources of Marine Litter; Gilardi, K., Ed.; International Maritime Organization. Rep. Stud. GESAMP: London, UK, 2021; 112p, Available online: http://www.gesamp.org/site/assets/files/2213/rs108e.pdf (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Matthews, T. Assessing Opinions on Abandoned, Lost, or Discarded Fishing Gear in the Caribbean. In Proceedings of the Gulf and Caribbean Fisheries Institute; Gulf and Caribbean Fisheries Institute: Marathon, FL, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Haghighatjou, N.; Gorgin, S.; Ghorbani, R.; Gilman, E.; Naderi, R.A.; Raeisi, H.; Farrukhbin, S. Rate and amount of abandoned, lost and discarded gear from the Iranian Persian Gulf Gargoor pot fishery. Mar. Policy 2022, 141, 105100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNFCCC. 4éme Communication Nationale du Maroc à la Convention Cadre des Nations Unies sur le Changement Climatique; UNFCCC: Rabat, Morocco, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Britannica. Climat of Morocco—Morocco Land. 2026. Available online: https://www.britannica.com/place/Morocco/Climate (accessed on 12 January 2026).

- Ozyurt, C.; Mavruk, S.; Kiyağa, V. The rate and causes of the loss of gill and trammel nets in Iskenderun Bay (north-eastern Mediterranean). J. Appl. Ichthyol. 2012, 28, 612–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category of Gear | Type of Gear | Period of Use/Year | Main Gear Components | Size of Component | Weight of Component (kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Net-gear | Trammel nets | 12 months | Net | 100 m/40 mm | 2.482 |

| Drift gillnet | 4 months | Net Ropes | 100 m/35 mm 100 m | 2.196 1.76–3.24 | |

| Bonitard | 4 months | Buoy | 1 item | 0.11–1.8 | |

| Bottom gillnets | 12 months | Floats | 1 item | 0.026–0.038 | |

| Beach seine nets | 4 months | Sinkers | 1item | 0.007–0.012 | |

| Purse seine nets | 12 months | ||||

| Trap-gear | Palanza | 10 months | Net | 100 m/15 mm | 3.45 |

| Pots (octopus) | 3 months | Pots | 1 item | 1 | |

| Ropes | 100 m | 1.76–3.24 | |||

| Line–hook gear | Octopus jigs | 5 months | Line | 500 m | 0.254 |

| Hook | 1 item | 0.003 | |||

| Buoy | 1 item | 0.106 | |||

| Sinkers | 1 item | 0.12 | |||

| Trolling lines | 12 months | Line | 500 m | 0.254 | |

| Hook | 1 item | 0.002–0.003 | |||

| Handlines | 12 months | Line | 500 m | 0.254 | |

| Hook | 1 item | 0.003 | |||

| Sinkers | 1 item | 0.5 | |||

| Longines | 12 months | Line | 500 m | 1.082 | |

| Ropes | 500 m | 4.36 | |||

| Hook | 1 item | 0.003 | |||

| Buoy | 1 item | 0.106 |

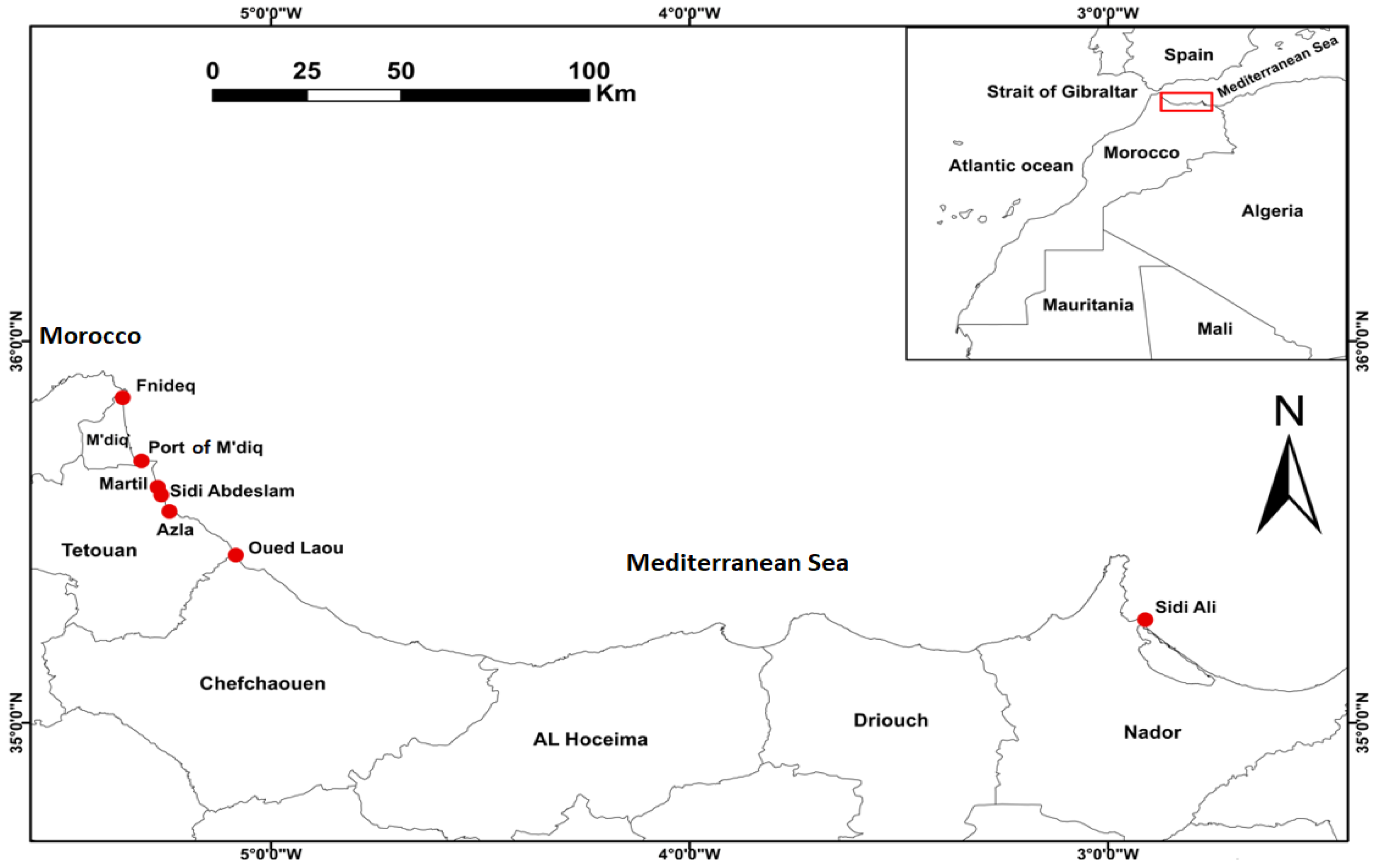

| Sites | Geographic Coordinates | Fishing Gear Used |

|---|---|---|

| Martil | 35.6166° N, −5.2752° W | Trammel nets, drift gillnets, bottom gillnets, pots (octopus), octopus jigs, longlines, handlines, trolling lines. |

| Port of M’diq | 35.67917° N, −5.30139° O | Bonitard, trammel nets, drift gillnets, octopus jigs, longlines, handlines, trolling lines. |

| Fnideq | 35.8525° N, −5.3556° O | Trammel nets, drift gillnets, octopus jigs, longlines, purse seine nets, trolling lines. |

| Azla | 35.5564° N, −5.24528° O | Trammel nets, drift gillnets, octopus jigs, longlines, purse seine nets, handlines. |

| Plage Sidi Abdeslam | 35.548° N, −5.229° O | Trammel nets, drift gillnets, longlines, octopus jigs. |

| Oued laou | 35.4484° N, −5.0963° O | Trammel nets, drift gillnets, bottom gillnets, purse seine nets, beach seine nets, octopus jigs, longlines. |

| Sidi Ali (Nador) | 35°10′ N, 2°45′ W | Palanza, trammel nets, octopus jigs, longlines, bottom gillnets. |

| N | Type of Gear | Average Use ± SDV | Average Loss ± SDV | Total Quantity of Use | Total Quantity of Loss | % of Loss per Type of Fishing Gear | % of Fishing Gear Lost in the Total Loss |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (kg·Boat−1·Year−1) | (kg·Boat−1·Year−1) | (kg·Year−1) | (kg·year−1) | ||||

| 82 | Drift gillnets | 217.93 ± 102.98 | 45.14 ± 72.96 | 17,870.00 | 3701.59 | 20.71% | 18.40% |

| 80 | Trammel nets | 329.55 ± 140.85 | 92.86 ± 104.58 | 26,364.33 | 7429.40 | 28.18% | 36.93% |

| 80 | Longlines | 47.91 ± 35.37 | 21.3 ± 23.33 | 3832.83 | 1704.06 | 44.46% | 8.47% |

| 79 | Octopus jigs | 108.84 ± 48.91 | 59.6 ± 42.23 | 8598.12 | 4708.14 | 54.76% | 23.41% |

| 17 | Trolling lines | 6.32 ± 4.47 | 3.95 ± 3.4 | 107.47 | 67.10 | 62.44% | 0.33% |

| 11 | Pots (octopus) | 55.54 ± 35.13 | 8.73 ± 8.27 | 610.96 | 95.98 | 15.71% | 0.48% |

| 10 | Handlines | 15.42 ± 11.53 | 7.58 ± 5.67 | 154.22 | 75.79 | 49.14% | 0.38% |

| 8 | Bottom gillnets | 337.58 ± 138.10 | 157.19 ± 149.82 | 2700.6 | 1257.5 | 46.56% | 6.25% |

| 8 | Purse seine nets | 646.92 ± 183.99 | 94.34 ± 78.14 | 5175.38 | 754.68 | 14.58% | 3.75% |

| 8 | Palanza | 321.07 ± 200.13 | 25.86 ± 17.8 | 2568.59 | 206.85 | 8.05% | 1.03% |

| 3 | Bonitard | 427.51 ± 121.6 | 34.68 ± 24.53 | 1282.53 | 104.03 | 8.11% | 0.52% |

| 1 | Beach seine nets | 171 | 9.92 | 5.80% | 0.05% | ||

| All gear types | 502.37 ± 274.61 | 138.29 ± 120.69 | 69,436.02 | 20,115.04 | 28.97% | 100% |

| Fishing Gear Categories | Total Quantity of Loss (kg·Year−1) | % of Category Lost in the Total Loss |

|---|---|---|

| Net-gear (Trammel nets, drift gillnets, bonitard, bottom gillnets, beach seine nets, and purse seine nets). | 13,257.62 | 65.91 |

| Line–hook gear (Octopus jigs, trolling lines, handlines, and longlines). | 6555.08 | 32.59 |

| Trap-gear (Pots (octopus) and palanza). | 302.83 | 1.51 |

| Total | 20,115.04 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Jellal, N.; Azaaouaj, S.; Touaf, M.; Rizzo, A.; Anfuso, G.; Nachite, D.; Aksissou, M. Lost Fishing Gear Generated by Artisanal Fishing Along the Moroccan Mediterranean Coast: Quantities and Causes of Loss. Sustainability 2026, 18, 1641. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18031641

Jellal N, Azaaouaj S, Touaf M, Rizzo A, Anfuso G, Nachite D, Aksissou M. Lost Fishing Gear Generated by Artisanal Fishing Along the Moroccan Mediterranean Coast: Quantities and Causes of Loss. Sustainability. 2026; 18(3):1641. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18031641

Chicago/Turabian StyleJellal, Nadia, Soria Azaaouaj, Mounia Touaf, Angela Rizzo, Giorgio Anfuso, Driss Nachite, and Mustapha Aksissou. 2026. "Lost Fishing Gear Generated by Artisanal Fishing Along the Moroccan Mediterranean Coast: Quantities and Causes of Loss" Sustainability 18, no. 3: 1641. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18031641

APA StyleJellal, N., Azaaouaj, S., Touaf, M., Rizzo, A., Anfuso, G., Nachite, D., & Aksissou, M. (2026). Lost Fishing Gear Generated by Artisanal Fishing Along the Moroccan Mediterranean Coast: Quantities and Causes of Loss. Sustainability, 18(3), 1641. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18031641