4.1. Descriptive Statistics

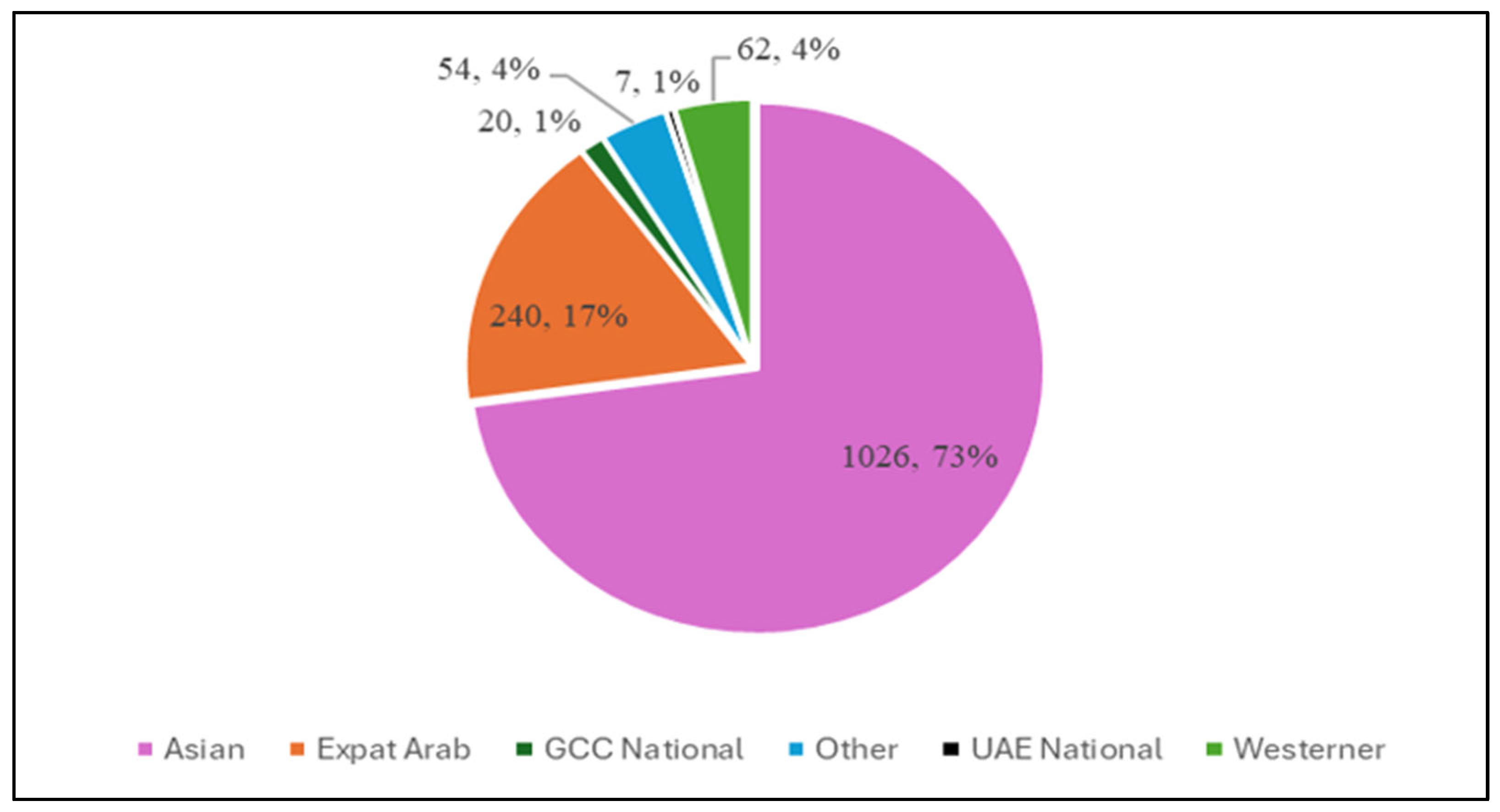

The demographic analysis using IBM SPSS Statistics (Version 29.0.2.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA), reveals that the metro ridership is predominantly composed of Asian nationals (72.8%), followed by Expat Arabs (17.0%), Westerners (4.4%), and other nationalities (3.8%), with UAE nationals representing only 0.5% of the sample as shown in

Figure 3. This distribution reflects Dubai’s diverse expatriate population and suggests that public transportation, particularly the metro, is heavily utilized by the expatriate workforce.

The residency status data indicates that 90.4% of respondents are Dubai residents, with smaller proportions from other emirates (3.3% from Sharjah) and visitors (5.0%). This concentration of Dubai residents aligns with the metro’s primary role as an urban transit system serving local commuting needs rather than tourism or inter-emirate travel.

Gender distribution shows a significant male majority (87.2%) compared to female riders (12.8%). This pronounced gender imbalance may reflect broader workforce demographics in Dubai, cultural factors affecting transportation choices, or potential barriers to female ridership that merit further investigation.

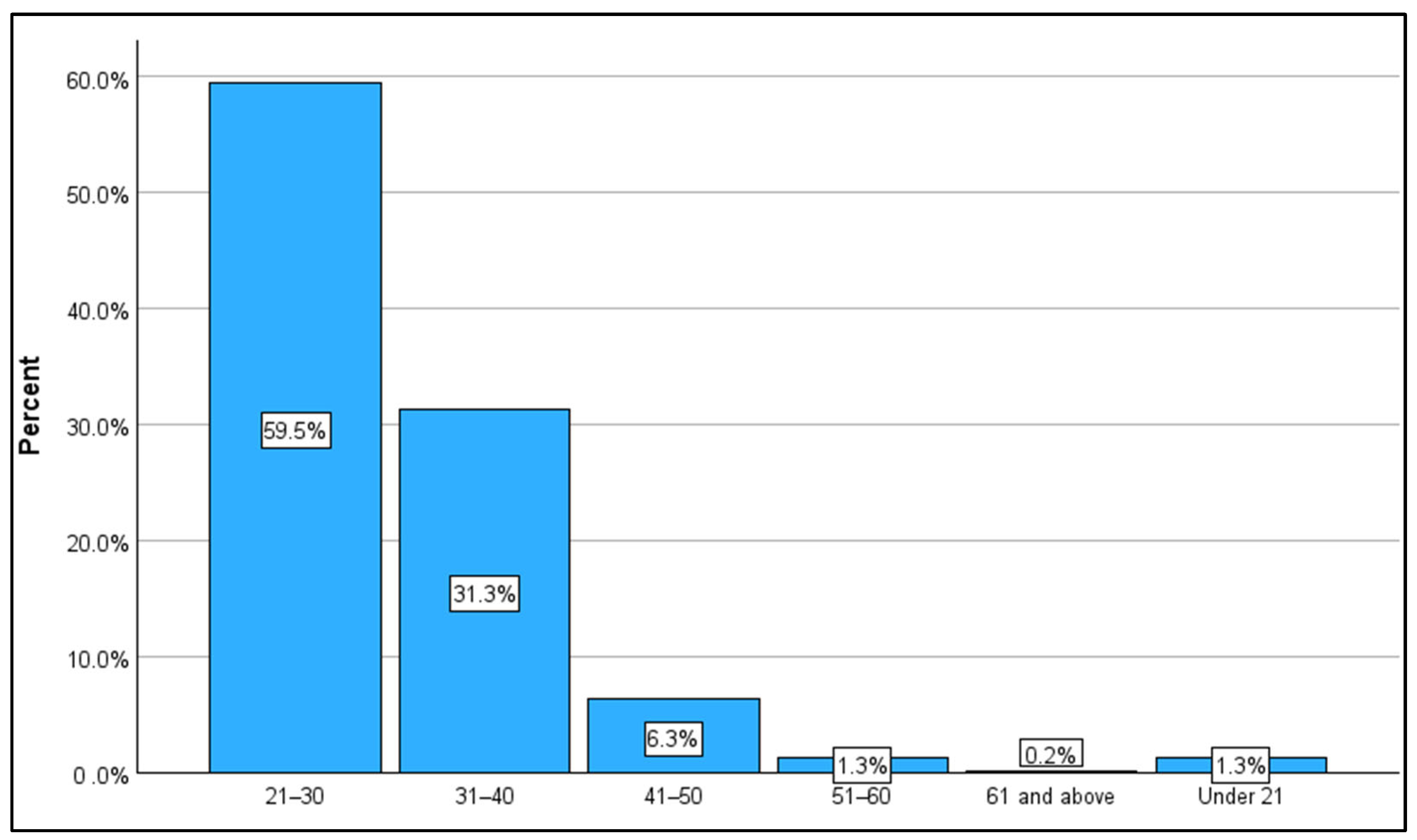

Age distribution data shown in

Figure 4 indicates that young adults dominate metro ridership, with 59.5% of respondents aged 21–30 and 31.3% aged 31–40. Only 8.3% of riders were over 40 years old, suggesting the metro particularly appeals to younger commuters, possibly due to its modernity, technological integration, or alignment with the commuting patterns of younger workers.

The age categories were created using regularly used demographic reporting brackets, which are comparable with how official data and large-sample transportation surveys normally divide populations into interpretable life-stage groupings. The brackets differentiate between early adulthood, mid-career working ages, and older cohorts, which is analytically important because perceptions of service quality, risk, comfort, and information utilization might vary significantly by life stage. Using these standard age bands increases interpretability, allows for comparison with official demographic summaries, and ensures appropriate counts within each category for consistent descriptive reporting and subgroup checks.

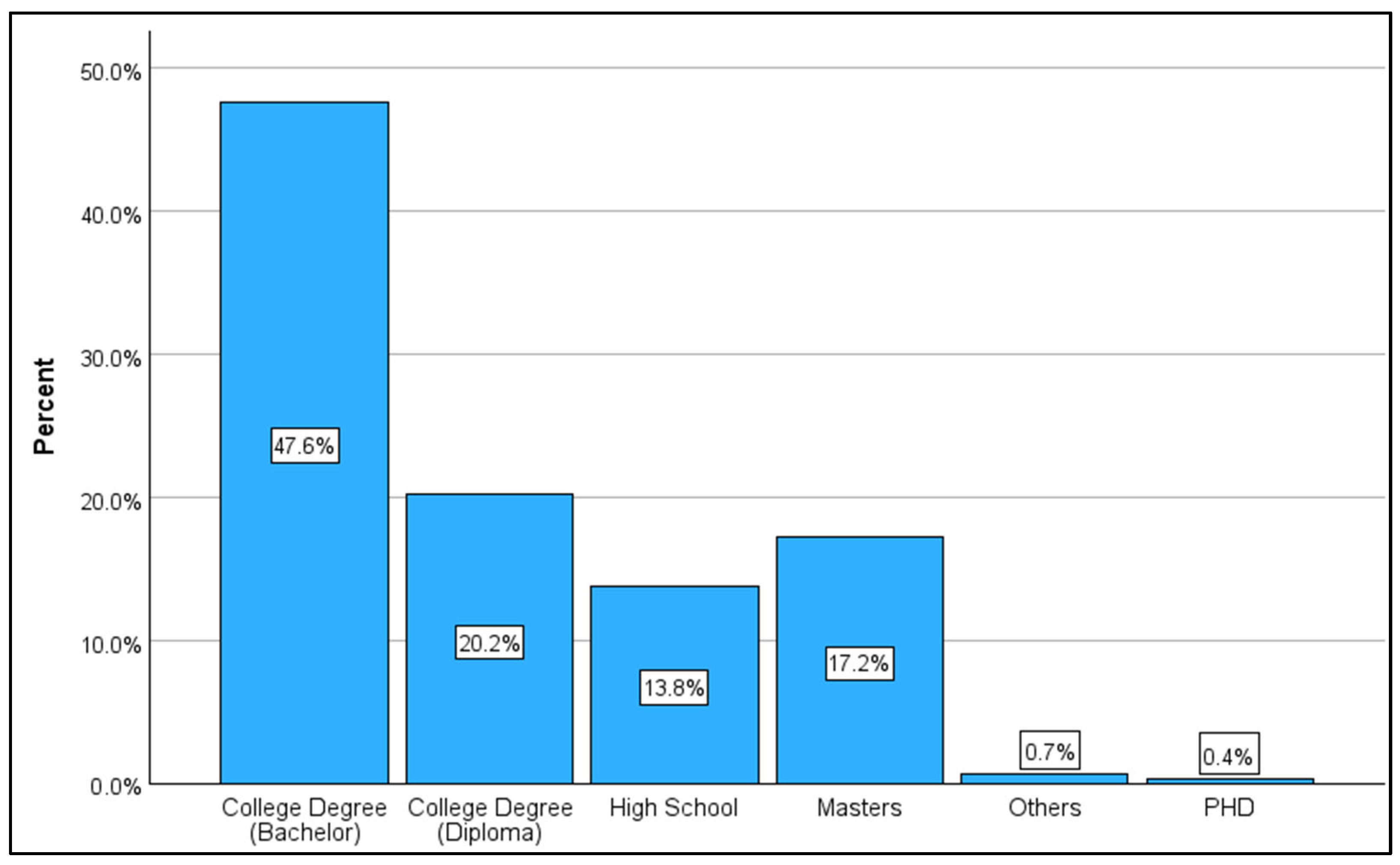

The educational background of metro riders in

Figure 5 reveals a highly educated user base, with 47.6% holding bachelor’s degrees and 17.2% holding master’s degrees. This educational profile suggests that the metro serves a significant proportion of professional and skilled workers in Dubai. Usage frequency data demonstrates that metro ridership is characterized by regular commuters, with 74.3% using it more than once per day and 17.5% using it once daily. This high frequency of use underscores the metro’s importance as a daily transportation solution rather than an occasional option.

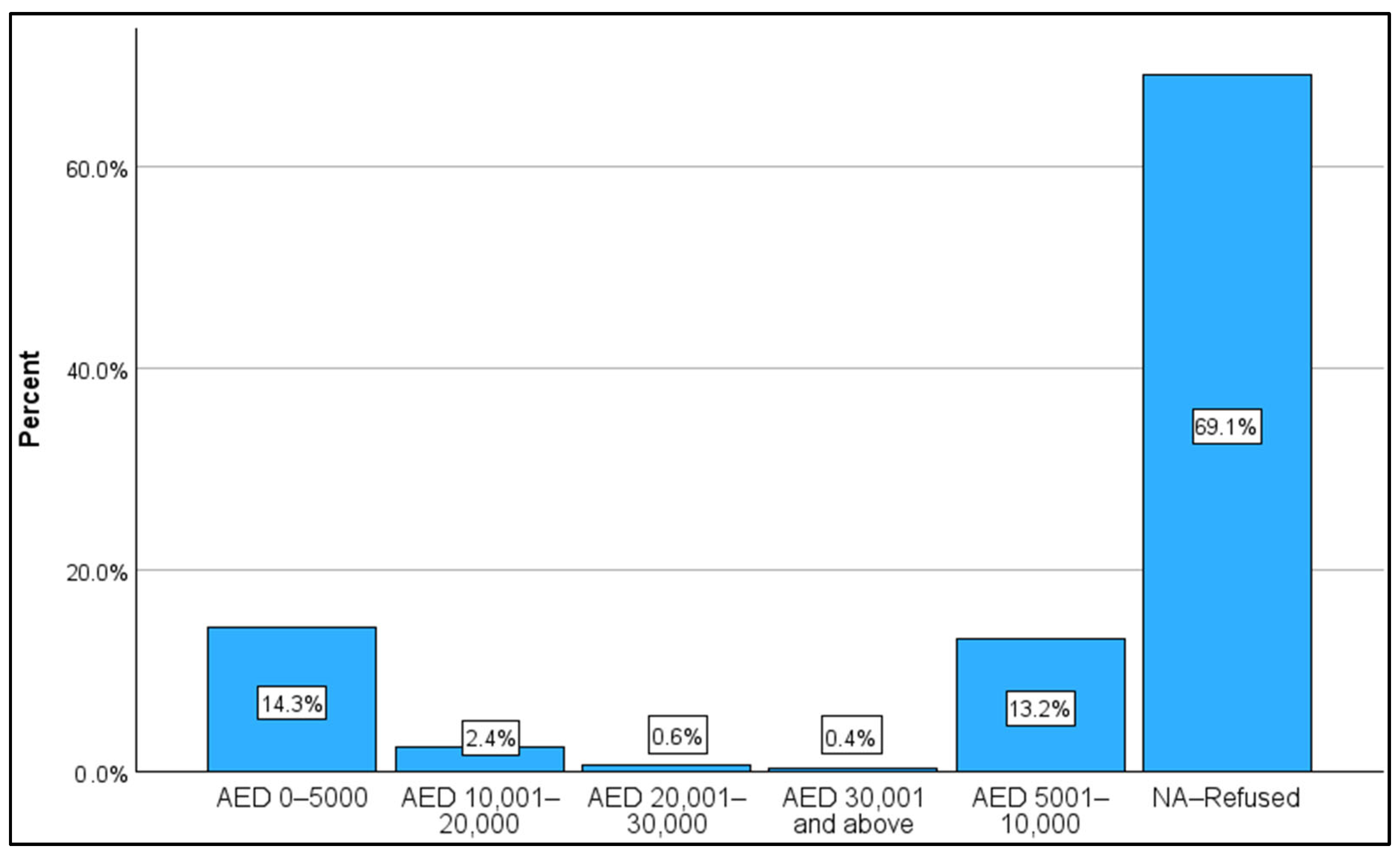

Further analysis of metro riders’ income was conducted as part of the study; the majority (69.1%) felt that this was sensitive information and preferred not to reveal it, while riders with salaries under AED 10,000 represented 27.5%, as seen in

Figure 6. The remaining 3.4% reported ≥AED 10,000 monthly. The income ranges were divided into broad bands to represent significantly distinct socioeconomic strata in a fashion that is easy to plan and broadly consistent with census-style reporting processes. This method avoids over-fragmenting respondents into narrow income intervals, which can result in sparse categories and unstable comparisons, while also capturing significant differences in affordability sensitivity and perceived value of service qualities. The chosen bands thus allow for a clearer interpretation of the sample profile and facilitate policy-relevant discussion (e.g., how rider experience and wellbeing may differ between lower- and higher-income segments), with the intention that future studies can compare these groupings to published national or city-level demographic distributions when available.

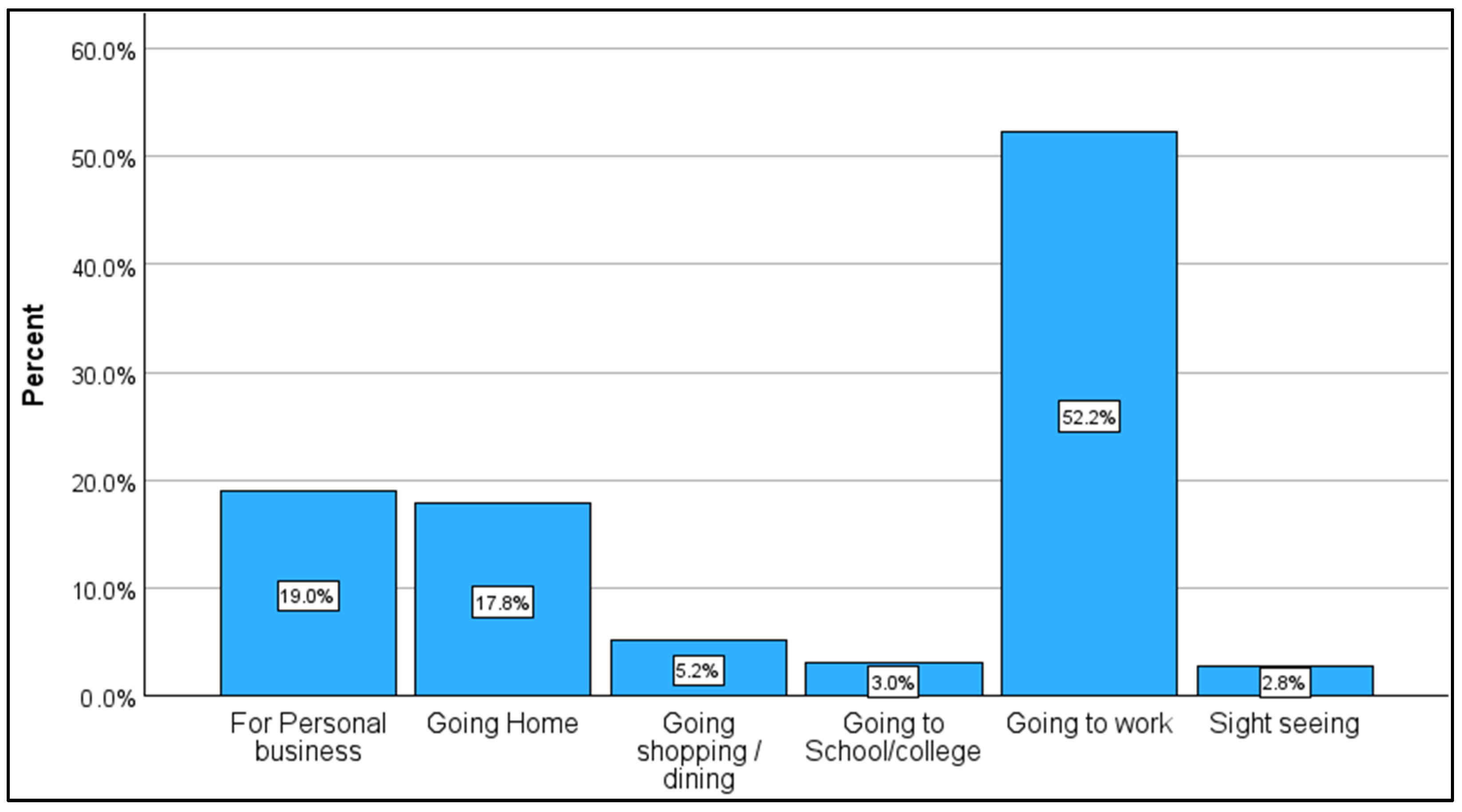

According to a trip purpose analysis shown in

Figure 7, over 50% of riders go to work, demonstrating the metro’s vital significance as a means of transportation for Dubai’s citizens. At the same time, 20% of all journeys are for commercial purposes, another ~20% were home-related trips. This adds up to 40%, suggesting that metro is a significant mode of transportation outside of the typical work trip. The remaining 10% fluctuates depending on other activities including dining, shopping, attending school, and tourism.

4.2. Statistical Analysis for Satisfaction Factors

The analysis began with data cleaning and validation, followed by descriptive statistics to understand the central tendencies, distributions, and variability of responses across all survey items. This included computing means, standard deviations, skewness, and kurtosis values to assess the normality of distributions. Frequency analyses were conducted to examine the demographic characteristics of respondents and their patterns of transit use. The reliability of the measurement scales was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha, with values of 0.908 for the metro survey, indicating excellent internal consistency in the dataset.

The results begin with descriptive statistics for each individual service attribute. Overall, the Dubai Metro received high scores across most indicators, with the average self-reported wellbeing score reaching 4.52 out of 5. The highest rated attributes were connectivity (mean = 4.54), staff professionalism (mean = 4.42), and privacy (mean = 4.35). On the other hand, speed of service (mean = 3.61), ease of service (mean = 3.71), and information availability (mean = 3.84) were rated comparatively lower, suggesting specific areas that could be targeted for improvement. The demographic profile of the participants. The survey captured a wide cross-section of Dubai’s mobile population, i.e., students, professionals, and tourists.

This sample shows a high level of rider wellbeing (mean ≈ 4.5/5). The main factors influencing wellbeing are identified by an analysis of answers across important service dimensions, which also reveals areas where focused improvements are most likely to have the biggest impact. These findings translate city-level policy into specific, doable priorities for planning and investment throughout the metro network, in line with the Dubai Urban Plan 2040, which places a high priority on wellbeing and people-centered transportation.

The correlation matrix reveals significant relationships between service attributes and rider wellbeing. All 13 service attributes show statistically significant positive correlations with rider wellbeing (p < 0.01). The strongest correlations with rider wellbeing are observed for connectivity (r = 0.816), staff professionalism (r = 0.757), and punctuality (r = 0.700). These strong associations suggest that a well-connected network, professional staff interactions, and reliable service are particularly important determinants of rider wellbeing in the metro system.

Moderate correlations are observed for cleanliness (r = 0.694), comfort (r = 0.670), and facilities (r = 0.630), highlighting the importance of physical environment factors in shaping the overall transit experience. The correlation patterns also reveal interesting interrelationships among service attributes. For instance, affordability shows strong correlations with speed of service (r = 0.789) and ease of service (r = 0.710), suggesting that perceptions of value for money are closely tied to service efficiency. Similarly, staff professionalism strongly correlates with connectivity (r = 0.839), indicating that human factors and network functionality may be perceived as interrelated aspects of service quality.

Bartlett’s test of sphericity and the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) index were used to evaluate the factorability of the variables. The KMO calculation yielded a respectable overall result of 0.886, showing a good fit for latent construct modeling. However, Bartlett’s test was significant, as shown by the results (x2 = 13,372, p < 0.001), which indicates the variables are sufficiently intercorrelated to confirm the use of the GSCA latent construct in this research.

The results showed a high condition index of 82.4 with a substantial variance in proportion for both privacy (0.57) and Ticketing clarity (0.91), supporting the analysis for multicollinearity and possibly suggesting some dependency of these parameters. All constructs, however, indicate outcomes that fall under the standard criteria. Additionally, the GSCA’s latent construct will tackle any multicollinearity issues.

Because wellbeing is measured on an ordinal Likert scale, a Mann–Whitney U test (two-tailed) was utilized to compare ratings between male and female riders. The findings revealed a minor but statistically significant difference (U = 127,170.5, Z = 2.23, p = 0.025), with males having a higher mean rank (731.01) than females (664.59), indicating a slightly larger tendency for males to report higher wellbeing categories. However, the practical significance of this difference was negligible (r = 0.059), and both groups had the same median rating of “Happy”.

In addition to the gender-based subgroup analysis, Mann–Whitney U test was used to determine whether overall wellbeing ratings varied by age. To ensure acceptable sample sizes, the survey age variable was divided into two categories: ≤30 years (Under 21 and 21–30) and >30 years (31–40 and above). The test found a statistically significant but small difference in overall wellbeing between the two age groups (U = 217,030.5, Z = −4.53, p < 0.001). Riders over 30 had a higher mean rank (778.40) than riders under 30 (686.25). However, the impact size was minor (r = 0.119), and the median assessment was “Happy” in both groups. While age-related changes can be seen in the distribution of responses, central wellbeing evaluations are generally consistent across age groups.

4.6. Composite Structural Equation for Metro Rider Wellbeing

Based on the GSCA modeling, the final structural equation for rider wellbeing is expressed as:

This equation indicates that while all three constructs matter, the greatest returns on enhancing overall wellbeing may come from improvements in operations and assurance, followed by investments in environmental comfort.

Also, it quantifies the direct effects of each latent construct on Rider Wellbeing. Service Operations & Assurance has the strongest direct effect (coefficient = 0.513), followed by Physical Environment & Passenger Comfort (coefficient = 0.318) and Service Efficiency & Accessibility (coefficient = 0.216). The term ε3 represents the residual variance in Rider Wellbeing not explained by the three latent constructs.

By substituting the measurement equations into the structural equation for Rider Wellbeing, a composite equation can be derived that expresses Rider Wellbeing directly in terms of all observed variables:

This expanded equation can be simplified to express the total effect of each observed variable on Rider Wellbeing:

This final equation reveals that Comfort (total effect = 0.136) and Cleanliness (total effect = 0.133) have the strongest total effects on Rider Wellbeing in the metro context, followed by Connectivity (total effect = 0.127) and Staff Professionalism (total effect = 0.114).

For multicollinearity, The inter-construct correlations show that some latent dimensions move together (e.g., the high SEA-SOA association, r ≈ 0.773), as expected in an integrated metro system where efficient access and operational assurance are jointly experienced (for example, affordability is strongly correlated with speed of service, r = 0.789, and staff professionalism is strongly correlated with connectivity, r = 0.839). Rather than treating this overlap as a fault, it was evaluated whether the shared variance was significant enough to jeopardize the structural results’ stability or interpretability. Collinearity diagnostics revealed a high condition index (82.4), with the highest concentration of shared variation found at the indicator level for privacy (variance proportion = 0.57) and ticketing clarity (variance proportion = 0.91). These specific operational factors appeared to be dependent on one another, but the remaining indicators and constructs met acceptable interpretation criteria. In this context, the GSCA component-based estimation is appropriate because it models constructs as latent composites and estimates their effects concurrently, which helps to accommodate correlated predictors and allows path coefficients to be interpreted as incremental (unique) contributions of each service dimension to wellbeing after accounting for overlap with the other dimensions. As a result, even with a strong SEA-SOA correlation, the model remains useful for prioritization since it distinguishes what is common among service evaluations from what each dimension uniquely explains in rider wellbeing [

28,

29].

4.8. Metro Model Hypothesis Testing

The correlation and GSCA analysis for the metro model generated statistical evidence to test 19 hypotheses concerning the relationships between individual service attributes, latent constructs, and rider wellbeing. Based on the path coefficients, standard errors, and 95% confidence intervals provided in the analysis output, each hypothesis can be systematically evaluated as shown in

Table 6 for hypotheses 1–13. It is noteworthy that several attributes exhibited limited support for the wellbeing model while also demonstrating statistically significant correlation results when examined with riders’ wellbeing. Despite this outcome, it is advised to keep these characteristics in the proposed model since they conceptually explain how the model measures different aspects of the riders’ psychology.

The analysis mostly used GSCA weights to test hypotheses H1–H13, which evaluate the impact of specific service qualities on bus rider wellbeing. Together with standard errors, confidence intervals, and significance values, weights show how much each observed variable contributed to the development of its latent construct. As a result, weights offer the statistical foundation for assessing whether an attribute’s construct significantly enhances rider wellbeing. In order to ensure that attributes accurately reflect their constructs, factor loadings are utilized as well to demonstrate measurement validity. Thus, loadings enhance construct validity, while weights validate significance.

SEM path coefficients (β values) were used in the study for hypotheses H14–H19, which investigate the links between latent factors and how they affect rider wellbeing. Path coefficients illustrate the structural linkages in the model by quantifying the strength and direction of effect between constructs. Path coefficients function at the construct level and directly test the theoretical paths outlined in the model, in contrast to weights, which function at the attribute level. The hierarchical structure of the framework is reflected in hypothesis testing in response to this methodological distinction: individual attributes are used to form constructs through statistically significant weights, and these constructs then have statistically significant paths that impact wellbeing. Thus, the application of path coefficients for construct-level hypotheses and weights for attribute-level hypotheses offers a rigorous and theoretically consistent approach.

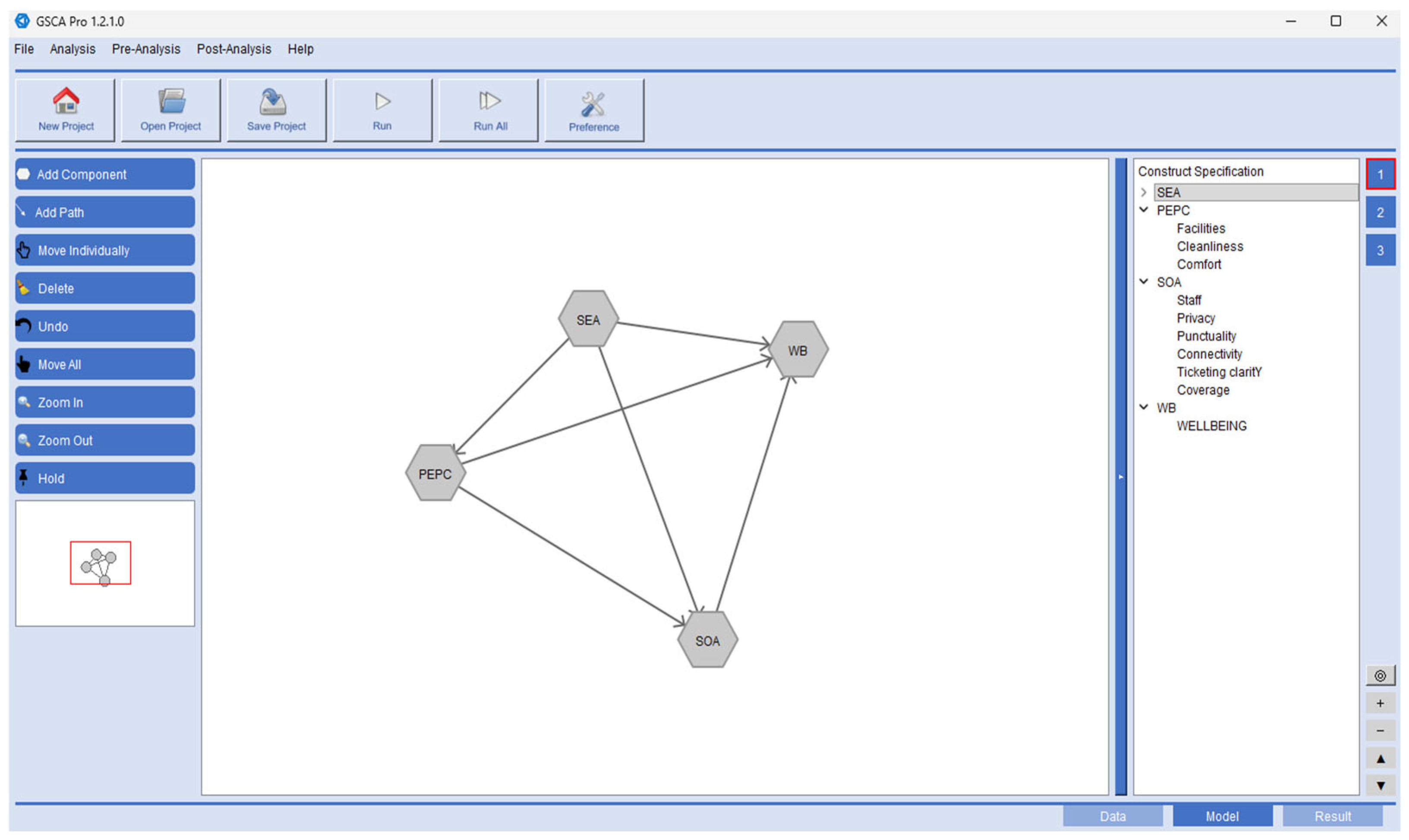

Table 7 shows the SEM Construct Significance and Hypothesis Results for each of the three constructs—SEA, SOA, and PEPC—which indicate that they are strongly connected with wellbeing on one side and with each other on the other side.