NutriRadar: A Mobile Application for the Digital Automation of Childhood Nutritional Classification Based on WHO Standards in the Peruvian Amazon

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Ecosocial Theory

2.2. Social Determinants of Health

2.3. Digital Divide

2.4. One Health

3. Materials and Methods

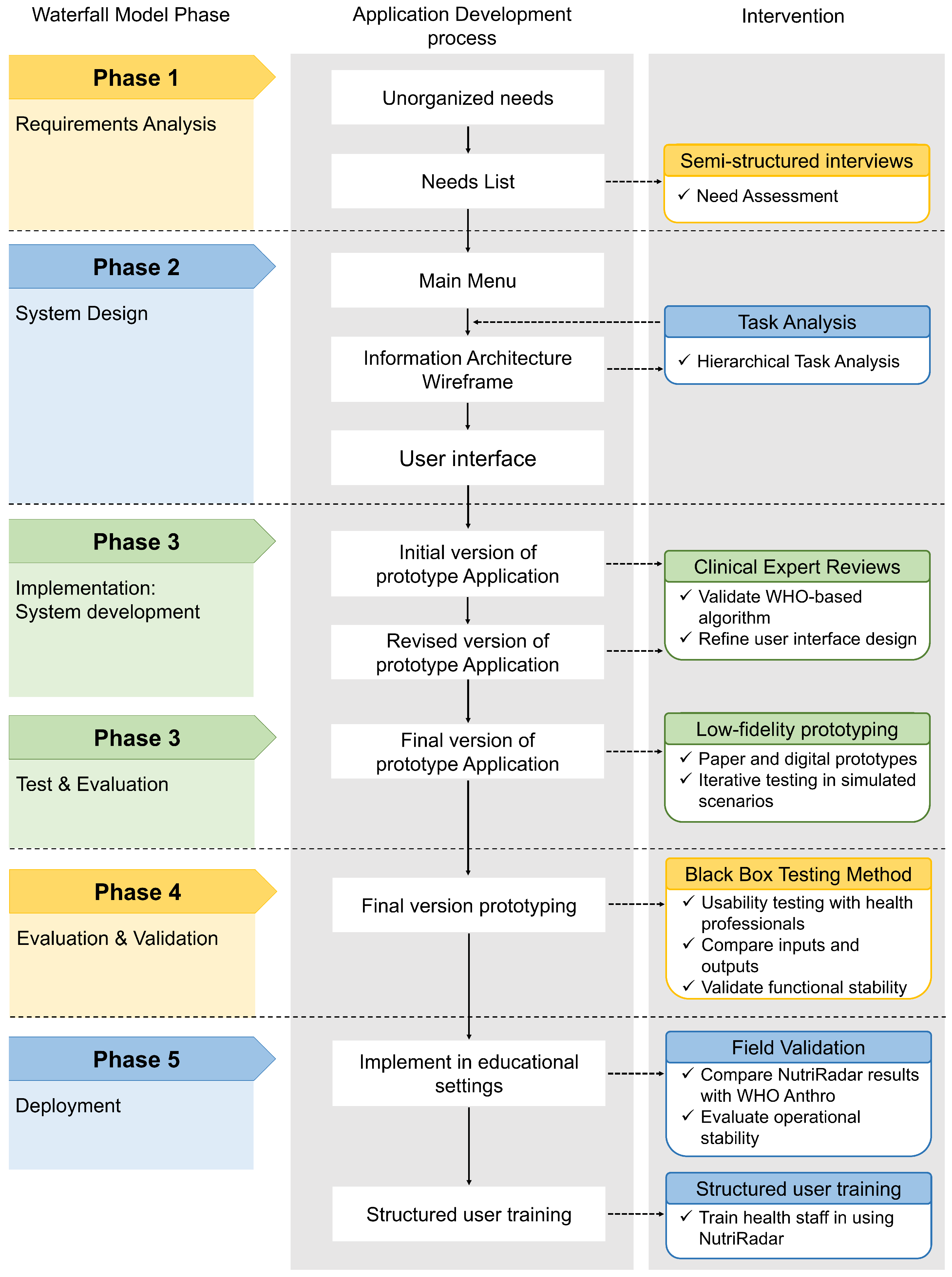

3.1. Methodological Design of the Study

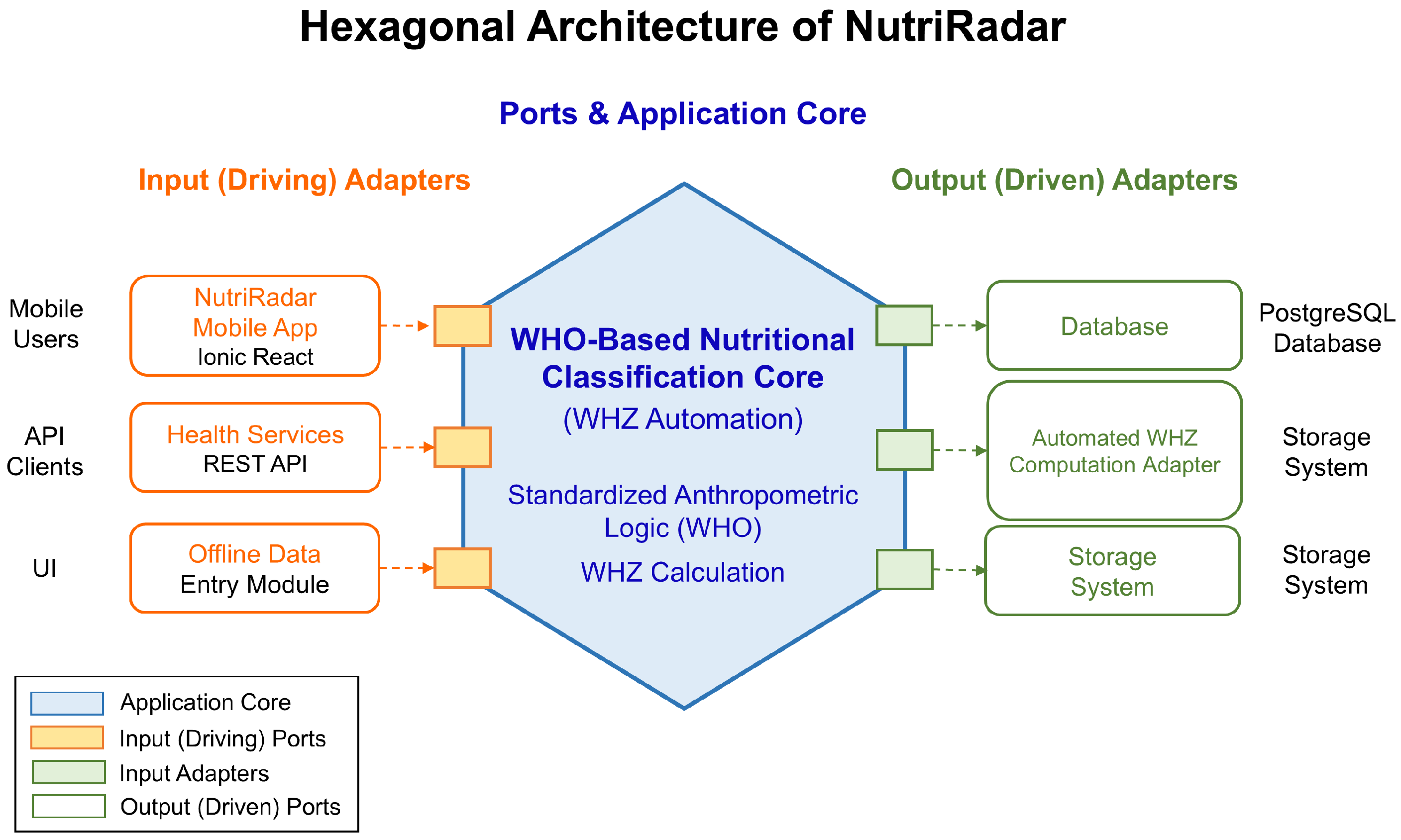

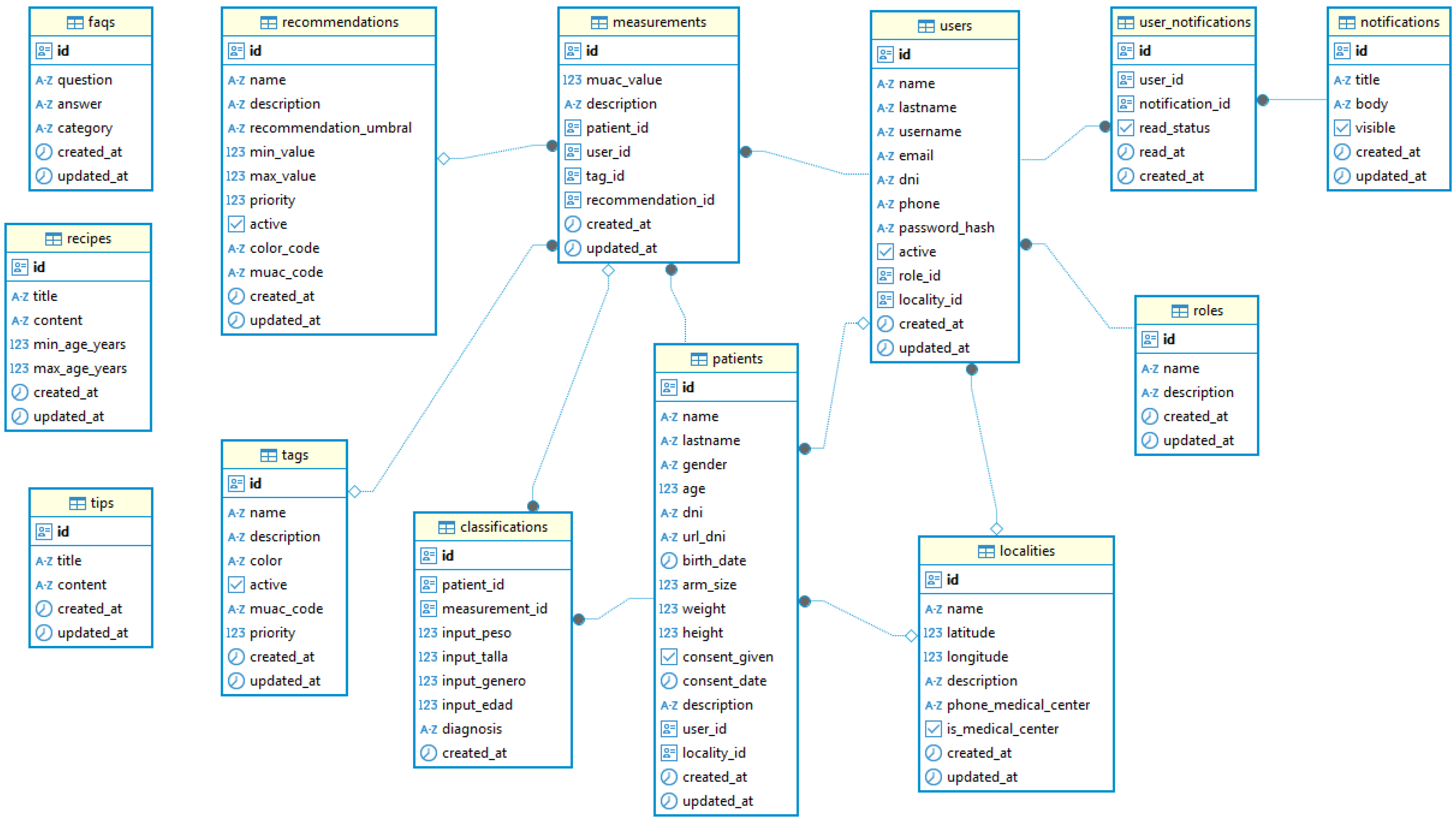

3.2. Development of the NutriRadar Mobile Application

3.2.1. Phase 1: Requirements Analysis

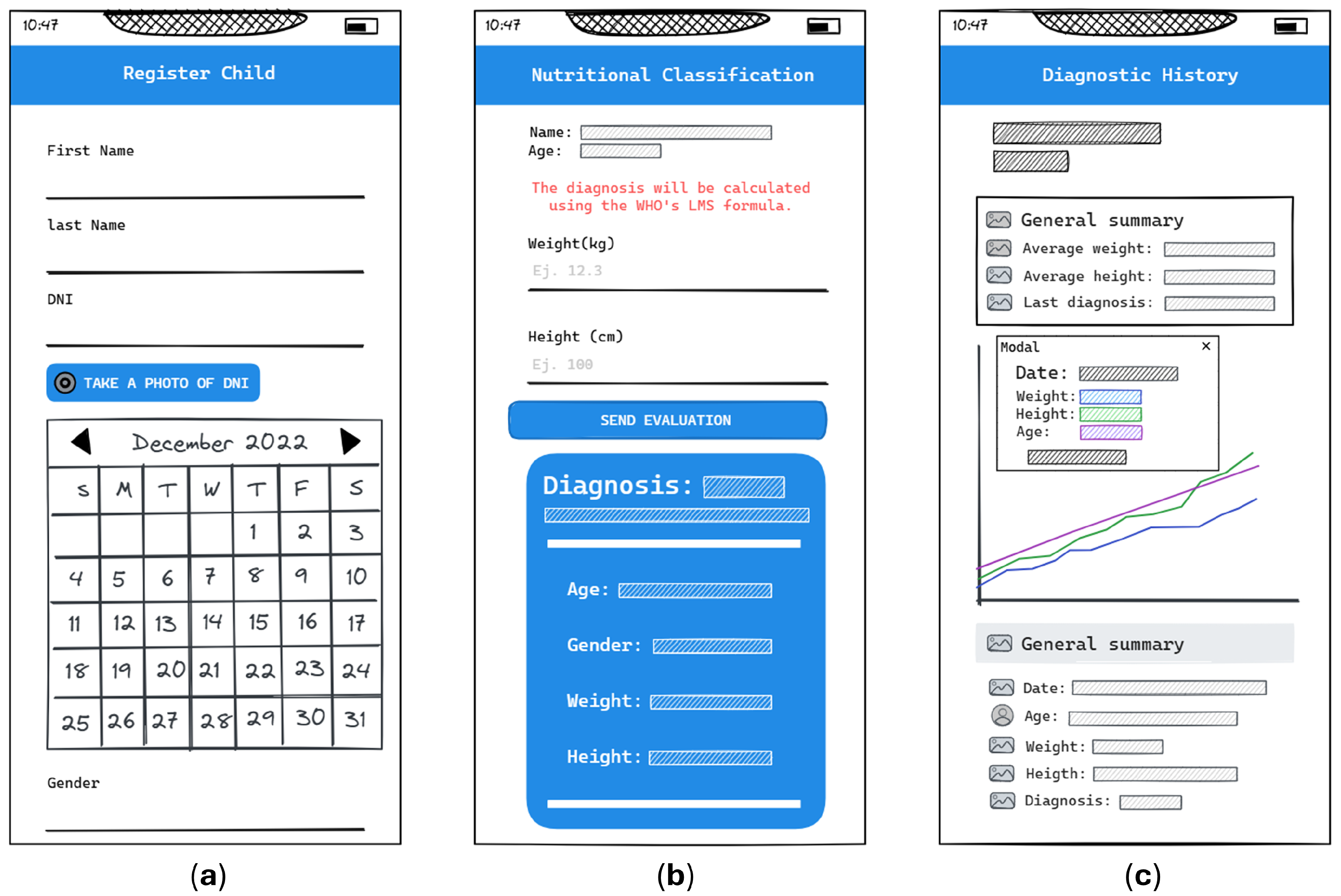

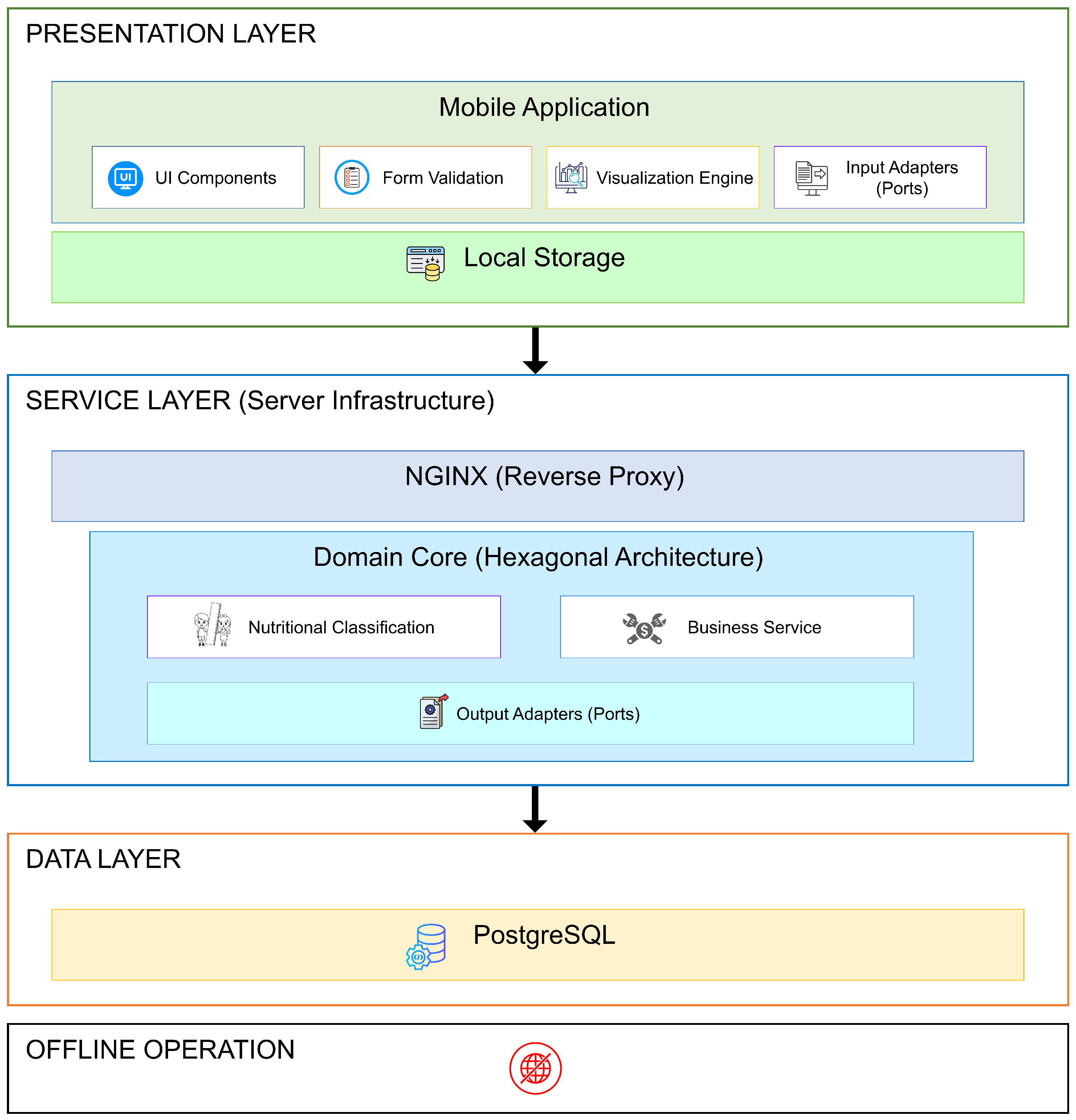

3.2.2. Phase 2: System Design

3.2.3. Phase 3: System Implementation

3.2.4. Implementation of the WHO Deterministic Nutritional Classification Module

| Algorithm 1: Classification of nutritional status based on WHZ |

|

3.2.5. Phase 4: Evaluation and Validation

3.2.6. Phase 5: Deployment and Field Validation

4. Results

4.1. Phase 1: Requirements Analysis

4.2. Phase 2: System Design

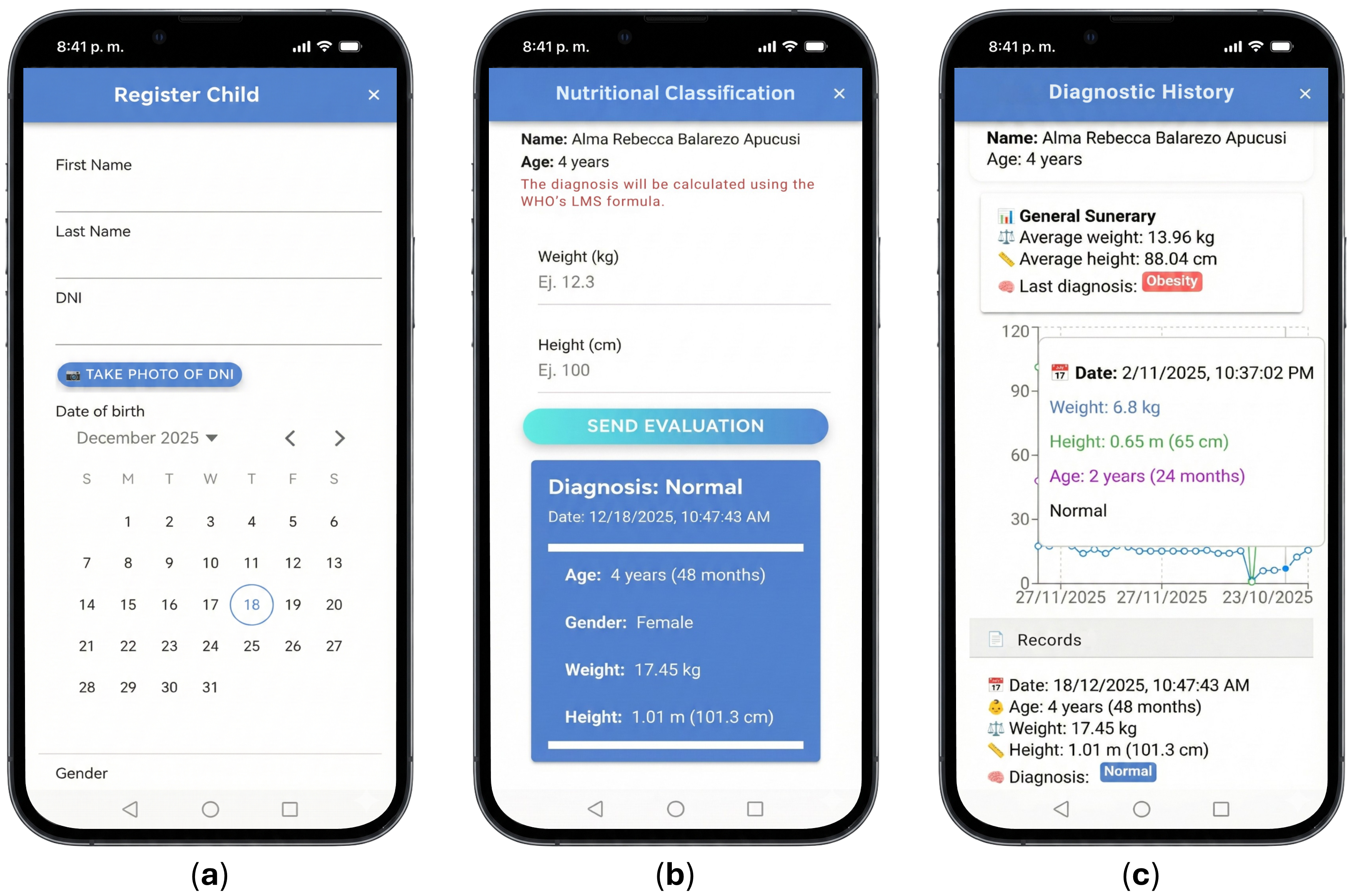

4.3. Phase 3: System Implementation

4.4. Phase 4: Evaluation and Validation

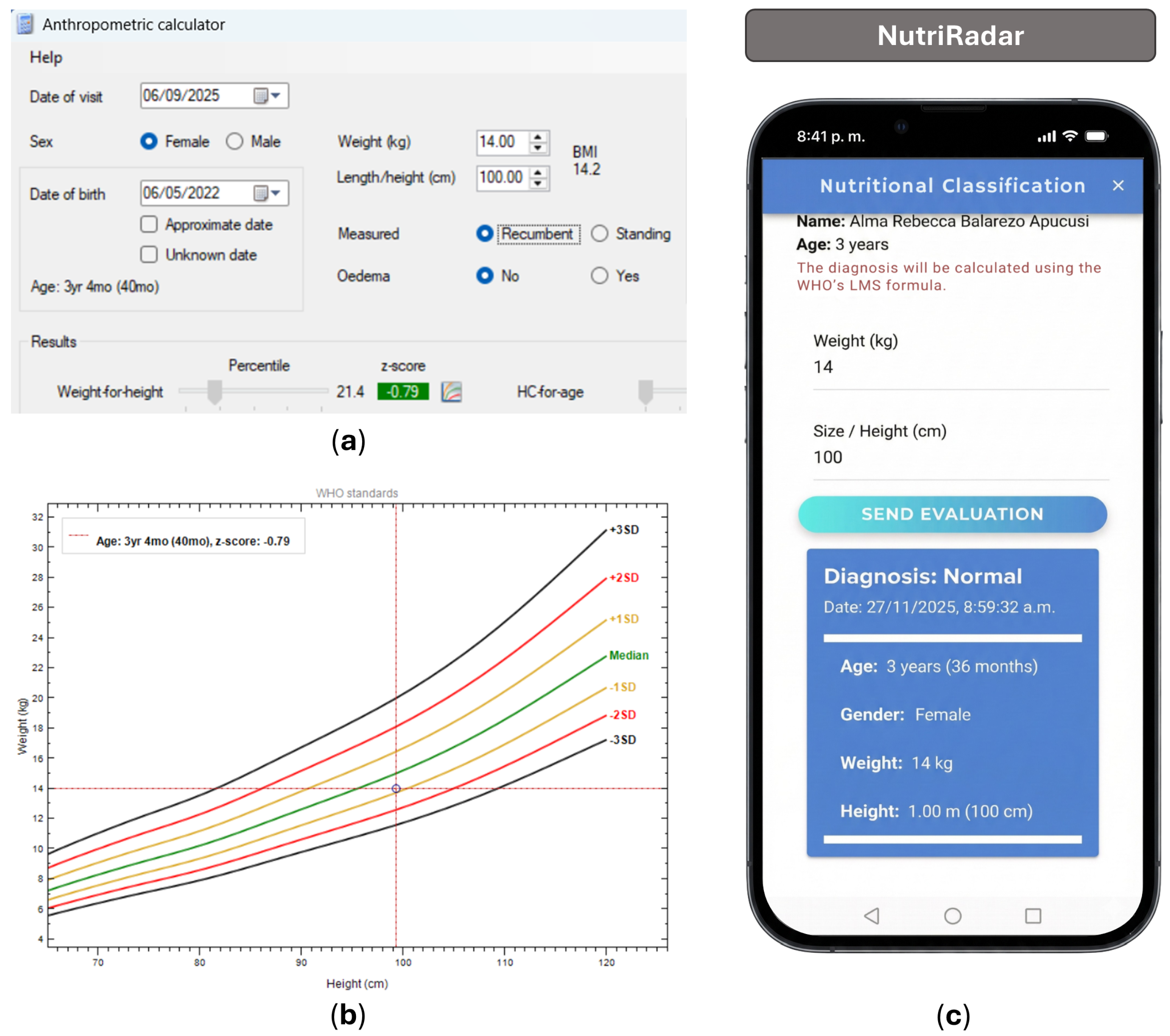

4.5. Phase 5: Deployment and Field Validation

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- OMS. Levels and Trends in Child Malnutrition; Technical Report; Organización Mundial de la Salud: Geneva, Switzerland, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF. La Infancia en Peligro: Emaciación Grave; Technical Report; Fondo de las Naciones Unidas para la Infancia: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. América Latina y el Caribe. Panorama Regional de la Seguridad Alimentaria y la Nutrición 2024; FAO: Rome, Italy; FIDA: Rome, Italy; OPS: Washington, DC, USA; PMA: Rome, Italy; UNICEF: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2025; pp. 1–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNICEF. Más de 420.000 Niños y Niñas Padecen una Sequía sin Precedentes en la Región Amazónica; UNICEF: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. El Estado de la Seguridad Alimentaria y la Nutrición en el Mundo 2024; FAO: Rome, Italy; FIDA: Rome, Italy; OMS: Geneva, Switzerland; PMA: Rome, Italy; UNICEF: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2024; pp. 1–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, L.; Eden, R.; Macklin, S.; Krivit, J.; Duncan, R.; Murray, H.; Donovan, R.; Sullivan, C. Strengthening rural healthcare outcomes through digital health: Qualitative multi-site case study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2024, 24, 1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, S.; Yam, E.L.Y.; Cheruvettolil, K.; Linos, E.; Gupta, A.; Palaniappan, L.; Rajeshuni, N.; Vaska, K.G.; Schulman, K.; Eggleston, K.N. Perspectives of Digital Health Innovations in Low- and Middle-Income Health Care Systems From South and Southeast Asia. J. Med. Internet Res. 2024, 26, e57612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivera, A.; Marín, V.; Romaní, F. Concurrence of anemia and stunting and associated factors among children aged 6 to 59 months in Peru. PLoS Glob. Public Health 2024, 4, e0002914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- del Carmen Segoviano-Lorenzo, M.; Trigo-Esteban, E.; Gyorkos, T.W.; St-Denis, K.; Guzmán, F.M.D.; Casapía-Morales, M. Prevalence of malnutrition, anemia, and soil-transmitted helminthiasis in preschool-age children living in peri-urban populations in the Peruvian Amazon. Cad. Saude Publica 2022, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INEI. Encuesta Demográfica y de Salud Familiar 2023; Technical Report; Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática: Lima, Peru, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- INS. Informe Gerencial SIEN-HIS Niños Anual 2023; Technical Report; Instituto Nacional de Salud: Bogotá, Colombia, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez, J.C.; Fernández, T.F.G.; Ríos, A.S.V.; Palacios, M.R.P.; García, G.M.G.; Carrasco, C.G.; Requena, J.M.R.; Recio, J.M.F.; López-Alegría, L.N.; Amador, A.P.; et al. Malnutrition and sarcopenia worsen short- and long-term outcomes in internal medicine inpatients. Postgrad. Med. J. 2023, 99, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gizaw, G.; Wells, J.C.; Argaw, A.; Olsen, M.F.; Abdissa, A.; Asres, Y.; Challa, F.; Berhane, M.; Abera, M.; Sadler, K.; et al. Associations of early childhood exposure to severe acute malnutrition and recovery with cardiometabolic risk markers in later childhood: 5-year prospective matched cohort study in Ethiopia. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2025, 121, 343–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Victora, C.G.; Christian, P.; Vidaletti, L.P.; Gatica-Domínguez, G.; Menon, P.; Black, R.E. Revisiting maternal and child undernutrition in low-income and middle-income countries: Variable progress towards an unfinished agenda. Lancet 2021, 397, 1388–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dipasquale, V.; Cucinotta, U.; Romano, C. Acute Malnutrition in Children: Pathophysiology, Clinical Effects and Treatment. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirolos, A.; Goyheneix, M.; Eliasz, M.K.; Chisala, M.; Lissauer, S.; Gladstone, M.; Kerac, M. Neurodevelopmental, cognitive, behavioural and mental health impairments following childhood malnutrition: A systematic review. BMJ Glob. Health 2022, 7, 9330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, J.J.; Guo, Y.J.; Li, Z.; Chen, Y.; He, H.; Li, W.M. Prevalence and prognostic significance of malnutrition risk in patients with pulmonary tuberculosis: A hospital-based cohort study. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 1039661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, H.A.; Correia, L.L.; Leite, Á.J.M.; Rocha, S.G.; Machado, M.M.; Campos, J.S.; Cunha, A.J.; e Silva, A.C.; Sudfeld, C.R. Undernutrition and short duration of breastfeeding association with child development: A population-based study. J. Pediatr. 2022, 98, 316–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sideropoulos, V.; Draper, A.; Munoz-Chereau, B.; Ang, L.; Dockrell, J.E. Childhood stunting and cognitive development: A meta-analysis. J. Glob. Health 2025, 15, 04257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suryawan, A.; Jalaludin, M.Y.; Poh, B.K.; Sanusi, R.; Tan, V.M.; Geurts, J.M.; Muhardi, L. Malnutrition in early life and its neurodevelopmental and cognitive consequences: A scoping review. Nutr. Res. Rev. 2022, 35, 136–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trujillo-Rondan, M.; Roldan-Arbieto, L.; Talavera, J.E.; Perez, M.A.; Correa-Lopez, L.E.; de la Cruz-Vargas, J.A.; Trujillo-Rondan, M.; Roldan-Arbieto, L.; Talavera, J.E.; Perez, M.A.; et al. Factors Associated with Chronic Child Malnutrition in Peru. Horiz. Sanit. 2022, 21, 158–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alao, R.; Nur, H.; Fivian, E.; Shankar, B.; Kadiyala, S.; Harris-Fry, H. Economic inequality in malnutrition: A global systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Glob. Health 2021, 6, 6906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, S.M.; Ahmed, N.A.; Abedin, M.M.; Ahammed, B.; Ali, M.; Rahman, M.J.; Maniruzzaman, M. Investigate the risk factors of stunting, wasting, and underweight among under-five Bangladeshi children and its prediction based on machine learning approach. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0253172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seenivasan, S.; Talukdar, D.; Nagpal, A. National income and macro-economic correlates of the double burden of malnutrition: An ecological study of adult populations in 188 countries over 42 years. Lancet Planet. Health 2023, 7, e469–e477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, F.; Salam, R.A.; Lassi, Z.S.; Das, J.K. The Intertwined Relationship Between Malnutrition and Poverty. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 525026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OMS. Primary Health Care Measurement Framework and Indicators: Monitoring Health Systems Through a Primary Health Care Lens; Organización Mundial de la Salud: Washington, DC, USA, 2022; pp. 1–48. [Google Scholar]

- Hulst, J.M.; Huysentruyt, K.; Gerasimidis, K.; Shamir, R.; Koletzko, B.; Chourdakis, M.; Fewtrell, M.; Joosten, K.F. A Practical Approach to Identifying Pediatric Disease-Associated Undernutrition: A Position Statement from the ESPGHAN Special Interest Group on Clinical Malnutrition. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2022, 74, 693–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, R.D.; Shaaban, S.Y.; Amrani, M.A.; Aldekhail, W.; Alhaffaf, F.A.; Alharbi, A.O.; Almehaidib, A.; Al-Suyufi, Y.; Al-Turaiki, M.; Amin, A.; et al. Protecting optimal childhood growth: Systematic nutritional screening, assessment, and intervention for children at risk of malnutrition in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1483234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aanjankumar, S.; Sathyamoorthy, M.; Dhanaraj, R.K.; Kumar, S.R.S.; Poonkuntran, S.; Khadidos, A.O.; Selvarajan, S. Prediction of malnutrition in kids by integrating ResNet-50-based deep learning technique using facial images. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 7871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de van der Schueren, M.A.; Keller, H.; Cederholm, T.; Barazzoni, R.; Compher, C.; Correia, M.I.; Gonzalez, M.C.; Jager-Wittenaar, H.; Pirlich, M.; Steiber, A.; et al. Global Leadership Initiative on Malnutrition (GLIM): Guidance on validation of the operational criteria for the diagnosis of protein-energy malnutrition in adults. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 39, 2872–2880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serón-Arbeloa, C.; Labarta-Monzón, L.; Puzo-Foncillas, J.; Mallor-Bonet, T.; Lafita-López, A.; Bueno-Vidales, N.; Montoro-Huguet, M. Malnutrition Screening and Assessment. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Onis, M.; Onyango, A.W.; Borghi, E.; Siyam, A.; Nishida, C.; Siekmann, J. Development of a WHO growth reference for school-aged children and adolescents. Bull. World Health Organ. 2007, 85, 660–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OMS. WHO Anthro Survey Analyser and Other Tools; OMS: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Alowais, S.A.; Alghamdi, S.S.; Alsuhebany, N.; Alqahtani, T.; Alshaya, A.I.; Almohareb, S.N.; Aldairem, A.; Alrashed, M.; Saleh, K.B.; Badreldin, H.A.; et al. Revolutionizing healthcare: The role of artificial intelligence in clinical practice. BMC Med. Educ. 2023, 23, 689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqurashi, M.A.; Alshagrawi, S. Assessing the Impact of Artificial Intelligence Applications on Diagnostic Accuracy in Saudi Arabian Healthcare: A Systematic Review. Open Public Health J. 2025, 18, e18749445369173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahim, Y.A.; Hasani, I.W.; Kabba, S.; Ragab, W.M. Artificial intelligence in healthcare and medicine: Clinical applications, therapeutic advances, and future perspectives. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2025, 30, 848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Javaid, M.; Haleem, A.; Singh, R.P.; Suman, R.; Rab, S. Significance of machine learning in healthcare: Features, pillars and applications. Int. J. Intell. Netw. 2022, 3, 58–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.; Kumar, P.; Deb, D.; Unguresan, M.L.; Muresan, V. Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning Based Intervention in Medical Infrastructure: A Review and Future Trends. Healthcare 2023, 11, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weissler, E.H.; Naumann, T.; Andersson, T.; Ranganath, R.; Elemento, O.; Luo, Y.; Freitag, D.F.; Benoit, J.; Hughes, M.C.; Khan, F.; et al. The role of machine learning in clinical research: Transforming the future of evidence generation. Trials 2021, 22, 537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carayon, P.; Wooldridge, A.; Hose, B.Z.; Salwei, M.; Benneyan, J. Challenges And Opportunities For Improving Patient Safety Through Human Factors And Systems Engineering. Health Aff. 2018, 37, 1862–1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OMS. WHO Guideline on the Prevention and Management of Wasting and Nutritional Oedema (Acute Malnutrition) in Infants and Children Under 5 Years; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; p. 208. [Google Scholar]

- Labrique, A.; Agarwal, S.; Tamrat, T.; Mehl, G. WHO Digital Health Guidelines: A milestone for global health. npj Digit. Med. 2020, 3, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myatt, M.; Khara, T.; Collins, S. A review of methods to detect cases of severely malnourished children in the community for their admission into community-based therapeutic care programs. Food Nutr. Bull. 2006, 27, S7–S23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ONU. La Asamblea General Adopta la Agenda 2030 para el Desarrollo Sostenible; ONU: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- MINSA. Plan Nacional para la Reducción y Control de la Anemia Materno Infantil y la Desnutrición cróNica Infantil en el Perú: 2017–2021; Technical Report; Ministerio de Salud: Lima, Peru, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- PCM. Política Nacional de Transformación Digital al 2030; Technical Report; Presidencia del Consejo de Ministros: Lima, Peru, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Krieger, N. Measures of racism, sexism, heterosexism, and gender binarism for health equity research: From structural injustice to embodied harm-an ecosocial analysis. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2019, 41, 37–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomson, L.J.; Critten, A.; Hume, V.; Chatterjee, H.J. Common features of environmentally and socially engaged community programs addressing the intersecting challenges of planetary and human health: Mixed methods analysis of survey and interview evidence from creative health practitioners. Front. Public Health 2025, 13, 1449317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellwanger, J.H.; Kulmann-Leal, B.; Kaminski, V.L.; Valverde-Villegas, J.M.; Veiga, A.B.G.D.; Spilki, F.R.; Fearnside, P.M.; Caesar, L.; Giatti, L.L.; Wallau, G.L.; et al. Beyond diversity loss and climate change: Impacts of Amazon deforestation on infectious diseases and public health. An. Acad. Bras. Ciências 2020, 92, e20191375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mastel, M.; Bussalleu, A.; Paz-Soldán, V.A.; Salmón-Mulanovich, G.; Valdés-Velásquez, A.; Hartinger, S.M. Critical linkages between land use change and human health in the Amazon region: A scoping review. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0196414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ansah, E.W.; Amoadu, M.; Obeng, P.; Sarfo, J.O. Health systems response to climate change adaptation: A scoping review of global evidence. BMC Public Health 2024, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myhre, S.L.; Frønsdal, K.B.; Ames, H.M.; Papadopoulou, E. A scoping review of climate resilient health system strategies in low-resource settings. Public Health 2025, 249, 106026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvear-Vega, S.; Vargas-Garrido, H. Social determinants of malnutrition in Chilean children aged up to five. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayati, M.; Arkia, E.; Emadi, M. Socio-economic inequality in the nutritional deficiencies among the world countries: Evidence from global burden of disease study 2019. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 2025, 44, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- König, L.M.; Krukowski, R.A.; Kuntsche, E.; Busse, H.; Gumbert, L.; Gemesi, K.; Neter, E.; Mohamed, N.F.; Ross, K.M.; John-Akinola, Y.O.; et al. Reducing intervention- and research-induced inequalities to tackle the digital divide in health promotion. Int. J. Equity Health 2023, 22, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal-Alaball, J.; Belmonte, I.A.; Zafra, R.P.; Escalé-Besa, A.; Oliva, J.A.; Perez, C.S. Abordaje de la transformación digital en salud para reducir la brecha digital. Atención Primaria 2023, 55, 102626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basheer, A.; Tran, M.; Khan, B.; Jentner, W.; Wendelboe, A.; Vogel, J.; Kuhn, K.; Wimberly, M.C.; Ebert, D. Comprehensive review of One Health systems for emerging infectious disease detection and management. One Health 2025, 21, 101253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Destoumieux-Garzón, D.; Mavingui, P.; Boetsch, G.; Boissier, J.; Darriet, F.; Duboz, P.; Fritsch, C.; Giraudoux, P.; Roux, F.L.; Morand, S.; et al. The one health concept: 10 years old and a long road ahead. Front. Vet. Sci. 2018, 5, 306018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muluneh, M.G. Impact of climate change on biodiversity and food security: A global perspective—A review article. Agric. Food Secur. 2021, 10, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, M.; Ehlers, J.P.; Nitsche, J. Aligning With the Goals of the Planetary Health Concept Regarding Ecological Sustainability and Digital Health: Scoping Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2025, 27, e71795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDermid, J.A. Software Safety: Where’s the Evidence? Australian Computer Society, Inc.: Brisbane, Australia, 2001; Volume 3, pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Kallio, H.; Pietilä, A.M.; Johnson, M.; Kangasniemi, M. Systematic methodological review: Developing a framework for a qualitative semi-structured interview guide. J. Adv. Nurs. 2016, 72, 2954–2965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, A.; Taylor, L.K.; Lemke, M.R. Task analysis. In Applied Human Factors in Medical Device Design; Privitera, M.B., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019; pp. 63–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshamaa, Z.M.; Saleem, N.N. Black box software testing techniques: A literature review. Passer J. Basic Appl. Sci. 2025, 7, 1001–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayuningtyas, P.; Ayuningtyas, P.K.; WP, D.A.; Rachmadi, P. Performance And Functional Testing with The Black Box Testing Method. Int. J. Progress. Sci. Technol. 2023, 39, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topol, E.J. High-performance medicine: The convergence of human and artificial intelligence. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, J. Hexagonal-Driven Development. In Domain-Driven Laravel; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 521–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunkesser, R. Using Hexagonal Architecture for Mobile Applications. In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Software Technologies (ICSOFT 2022), Lisbon, Portugal, 11–13 July 2022; pp. 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, V.; Niu, N.; Alves, C.; Valença, G. Requirements engineering for software product lines: A systematic literature review. Inf. Softw. Technol. 2010, 52, 806–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buschmann, F.; Henney, K.; Schmidt, D.C. Pattern-Oriented Software Architecture: On Patterns and Pattern Languages; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kushniruk, A.W.; Patel, V.L. Cognitive and usability engineering methods for the evaluation of clinical information systems. J. Biomed. Inform. 2004, 37, 56–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanton, N.A.; Salmon, P.M.; Rafferty, L.A.; Walker, G.H.; Baber, C.; Jenkins, D.P. Human Factors Methods: A Practical Guide for Engineering and Design; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017; pp. 1–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OMS. WHO Child Growth Standards based on length/height, weight and age. Acta Paediatr. 2006, 450, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OMS. Guideline: Assessing and Managing Children at Primary Health-Care Facilities to Prevent Overweight and Obesity in the Context of the Double Burden of Malnutrition; Organización Mundial de la Salud: Ginebra, Suiza, 2017; pp. 1–88. [Google Scholar]

- Cogill, B. Anthropometric Indicators Measurement Guide; Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance Project, Academy for Educational Development: Washington, DC, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hurt, K.; Walker, R.J.; Campbell, J.A.; Egede, L.E. mHealth Interventions in Low and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review. Glob. J. Health Sci. 2016, 8, p183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OMS. WHO Guideline Recommendations on Digital Interventions for Health System Strengthening; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; Volume WHO/RHR/19, p. p. 13. [Google Scholar]

- Alami, H.; Rivard, L.; Lehoux, P.; Ahmed, M.A.A.; Fortin, J.P.; Fleet, R. Integrating environmental considerations in digital health technology assessment and procurement: Stakeholders’ perspectives. Digit. Health 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belkhir, L.; Elmeligi, A. Assessing ICT global emissions footprint: Trends to 2040 & recommendations. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 177, 448–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhutta, Z.A.; Das, J.K.; Rizvi, A.; Gaffey, M.F.; Walker, N.; Horton, S.; Webb, P.; Lartey, A.; Black, R.E. Evidence-based interventions for improvement of maternal and child nutrition: What can be done and at what cost? Lancet 2013, 382, 452–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Black, R.E.; Victora, C.G.; Walker, S.P.; Bhutta, Z.A.; Christian, P.; Onis, M.D.; Ezzati, M.; Grantham-Mcgregor, S.; Katz, J.; Martorell, R.; et al. Maternal and child undernutrition and overweight in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet 2013, 382, 427–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krieger, N. Epidemiology and the People’s Health: Theory and Context. In Epidemiology and the People’s Health: Theory and Context; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011; pp. 1–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Specific Requirements |

|---|---|

| Clinical functionality | Automated WHZ calculation according to WHO methodology; immediate nutritional classification; anthropometric plausibility validation; evaluation traceability. |

| Operational constraints | Offline operation; data synchronization; compatibility with low-end devices. |

| Usability | Minimalist interface with simplified workflow (up to five steps); response time of up to 30 s; clear visual feedback of classification. |

| Security and privacy | User authentication; compliance with health data protection regulations. |

| Interoperability | Data export in standard format. |

| ID | Functional Requirement | Input | Action | Expected Result | Obtained Result | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RF-FC-01 | Automated WHZ calculation according to WHO methodology | Valid anthropometric data | Press “Submit evaluation” | Automatic WHZ calculation | WHZ calculated correctly | Approved |

| RF-FC-02 | Immediate nutritional classification | Weight-for-height index | View result | Nutritional status classification | Classification displayed correctly | Approved |

| RF-FC-03 | Anthropometric plausibility validation | Anthropometric data out of range | Press “Submit evaluation” | Warning message displayed indicating implausible data | Warning message displayed correctly | Approved |

| RF-FC-04 | Assessment Traceability | Nutritional assessment completed | Press “Save” | Assessment recorded and available in user history | Assessment successfully recorded in history | Approved |

| RF-INT-05 | Exporting Results | Selected Assessment | Press “Export” | File Generated | File Exported Successfully | Approved |

| No. | Date of Birth | Sex | Weight (kg) | Height (cm) | NutriRadar Classification | WHO Anthro Classification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5 May 2021 | M | 15.2 | 95 | Normal | Normal |

| 2 | 6 May 2021 | F | 14.0 | 100 | Normal | Normal |

| 3 | 29 June 2021 | M | 15.5 | 99.5 | Normal | Normal |

| … | … | … | … | … | … | … |

| 73 | 6 May 2022 | M | 14.0 | 100 | Normal | Normal |

| 74 | 17 July 2021 | F | 17.5 | 102.8 | Normal | Normal |

| 75 | 16 March 2021 | M | 21.0 | 108 | Normal | Normal |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Prieto-Luna, J.C.; Holgado-Apaza, L.A.; Ccolque-Quispe, D.; Gallegos Ramos, N.A.; Jaramillo-Peralta, D.A.; Madueño-Portilla, R.; Herrera Quispe, J.A.; Alarcon-Sucasaca, A.; Arpita-Salcedo, F.; Castellon-Apaza, D.D. NutriRadar: A Mobile Application for the Digital Automation of Childhood Nutritional Classification Based on WHO Standards in the Peruvian Amazon. Sustainability 2026, 18, 1639. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18031639

Prieto-Luna JC, Holgado-Apaza LA, Ccolque-Quispe D, Gallegos Ramos NA, Jaramillo-Peralta DA, Madueño-Portilla R, Herrera Quispe JA, Alarcon-Sucasaca A, Arpita-Salcedo F, Castellon-Apaza DD. NutriRadar: A Mobile Application for the Digital Automation of Childhood Nutritional Classification Based on WHO Standards in the Peruvian Amazon. Sustainability. 2026; 18(3):1639. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18031639

Chicago/Turabian StylePrieto-Luna, Jaime Cesar, Luis Alberto Holgado-Apaza, David Ccolque-Quispe, Nestor Antonio Gallegos Ramos, Denys Alberto Jaramillo-Peralta, Roxana Madueño-Portilla, José Alfredo Herrera Quispe, Aldo Alarcon-Sucasaca, Frank Arpita-Salcedo, and Danger David Castellon-Apaza. 2026. "NutriRadar: A Mobile Application for the Digital Automation of Childhood Nutritional Classification Based on WHO Standards in the Peruvian Amazon" Sustainability 18, no. 3: 1639. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18031639

APA StylePrieto-Luna, J. C., Holgado-Apaza, L. A., Ccolque-Quispe, D., Gallegos Ramos, N. A., Jaramillo-Peralta, D. A., Madueño-Portilla, R., Herrera Quispe, J. A., Alarcon-Sucasaca, A., Arpita-Salcedo, F., & Castellon-Apaza, D. D. (2026). NutriRadar: A Mobile Application for the Digital Automation of Childhood Nutritional Classification Based on WHO Standards in the Peruvian Amazon. Sustainability, 18(3), 1639. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18031639