1. Introduction

In recent years, energy production and distribution systems have been undergoing deep changes due to the effects of climate change. Several studies have highlighted the importance of accelerating the transition from fossil-fuel-based to renewable-energy-based systems to avoid the dramatic effects of global warming [

1].

In particular, the structure of traditional centralized energy systems is shifting towards distributed systems based on smart grids, where various assets, such as households with photovoltaic systems, are no longer only loads that receive energy from the distribution network, but become active elements that can inject energy into the power grid. Moreover, many companies and local communities, driven by the development of renewable energy technologies, are increasingly looking for solutions to become more independent from conventional energy systems; by producing their own energy, they can contribute to environmental sustainability while achieving economic benefits [

2].

However, to reach this objective, the development of advanced and efficient technical solutions along with energy policies oriented to the improvement of the adoption of renewable energy technologies is straightforward and governments are adapting their laws to push this transition. In particular, the European Union has taken several actions during recent years, establishing environmental targets for its members and introducing legal frameworks to encourage a change in the energy production and consumption paradigm [

3]. One of these is the introduction of energy communities.

The concept of energy communities has been introduced into European legislation to push for the creation of citizen-driven energy actions that contribute to the clean energy transition, advancing energy efficiency within local communities. Recent review work has mapped the global diffusion and key features of energy communities, with a particular focus on building-load modelling and management strategies [

4]. The main goal of energy communities is to change the paradigm of energy production and consumption by restructuring energy systems. Within energy communities, citizens become active actors that are allowed to actively participate in the energy transition, are locally empowered and directly benefit from better energy efficiency, lower bills, reduced energy poverty, and more local, green job opportunities; therefore, the subjects of energy communities are the so-called prosumers, that is, producers and consumers [

5]. To support their adoption, EU legislation introduced energy communities in 2019 through the Clean Energy for All Europeans Package [

6] and the Directive on common rules for the internal electricity market [

7].

Energy communities will thus contribute to the transformation from centralized and fossil fuel-based energy systems to decentralised systems based on renewable energy technologies with the direct engagement of different components of the society [

8].

Nonetheless, this transformation is not straightforward. The introduction of decentralized assets like photovoltaic systems and electric vehicles may cause problems to the power grid related to the synchronisation of loads and demands, voltage, frequency, and stability issues among the others [

9].

Considering the literature concerning the development of hybrid renewable energy systems (HRES), concerning their optimal sizing and operation optimisation, many research studies have been realized. Extensive reviews can be found in [

10,

11,

12]. Some authors of this paper also addressed the problem of the optimal sizing and management of HRES, proposing optimisation algorithms based on Mixed Integer Linear Programming (MILP) techniques to solve these issues [

13,

14]. Building on these works, the advancement and optimisation of smart grid technology to enhance the integration of renewable energy sources into energy systems, coupled with the development of corresponding flexibility business models, have been recognized as crucial factors for the proliferation of energy communities [

15].

In this context, energy communities constitute a step forward and thus have to be conceptualized and designed to provide a solution to these issues instead of contributing to the problems.

Within this framework, it is necessary to consider different factors and community purposes related to novel technological solutions based on distributed energy networks and new business models that have to encourage the active participation of the prosumers in a decentralized energy system [

16].

Considering energy communities, the technological challenges, and their complex regulatory frameworks, studies have addressed these challenges and proposed several solutions. For example, considering technological issues, the study of [

17] aims to evaluate the off-grid operation of a local energy community in central Italy, powered by a 220 kW small-scale hydropower plant. The analysis employs the Calliope framework to compare the performance of two energy storage systems: A battery energy storage system and a hydrogen storage system. The findings indicate that the hydrogen storage system requires a 137 kW electrolyser, a 41 kW fuel cell, and a storage capacity of 5247

of hydrogen. In contrast, the battery energy storage system would necessitate a storage capacity of 280 MWh. The authors of [

18] analysed an energy community in the Netherlands constituted by 47 households equipped with either a PV system or battery storage and connected to the distribution grid with a single point. The energy community and the assets have been modelled with the open-source Decentralized Energy Management toolkit (DEMKit) [

19] applying novel pricing mechanisms so that the overall stress on the grid network is reduced. The authors demonstrated the fundamental role of batteries storage, the benefits related with the reduction of the peak at the transformer, and potential costs savings for the members.

In [

20], a novel day-ahead scheduling model for prosumers integrated in energy communities has been developed to address the challenge of the multiple uncertainties related with energy transactions with the power grid and among the community members involved in these energy systems. The model has been applied to a case study with a six-prosumers community in Spain, demonstrating a benefit of about an 86% in the electricity bill.

In [

21], the authors propose a cascade model designed to accomplish two main objectives: first, to compute an energy schedule that meets the requirements of individual prosumers, and second, to enhance energy sharing at the community level to minimize overall costs. This model organizes prosumers into groups, and at each step, an optimisation problem is solved for all users within a group. The resulting solution allows for the creation of a “super-user,” which encapsulates the collective energy needs of the previously considered groups.

Despite the growing literature on REC governance and on techno-economic optimisation of hybrid renewable energy systems, a practical gap remains between (i) stakeholder-driven preference elicitation and (ii) transparent, constraint-explicit optimisation models that are readily configurable to national REC frameworks (e.g., the Italian virtual-sharing scheme). Existing approaches often emphasise either qualitative governance aspects or sizing/dispatch optimisation without making preference integration and modelling assumptions easily reproducible.

This paper addresses this gap through the following contributions: (1) a two-level decision workflow that links stakeholder preference elicitation to optimisation inputs; (2) a modular, constraint-explicit multi-objective optimisation formulation combining cost, operational emissions, and reliability; (3) an implementation architecture designed for extensibility towards digital-twin-enabled studies; and (4) an Italy-aligned configuration that can be adapted to other policy contexts.

This paper presents a decision-making tool for the development of energy communities. The tool is based on a two-level multi-objective optimisation algorithm that provides, as output, the optimal sizing of the assets of the energy community considering different KPIs. The tool is tested on a set of prototype residential scenarios located in the Autonomous Province of Bozen-Bolzano, which serve as building blocks for future REC scale applications. The paper is organized as follows: in

Section 2, the decision-making tool is described along with the models implemented in the optimisation problem and the case study analysed to test the tool; in

Section 3, results of the simulation applied to the case study are analysed and described;

Section 4 concludes the paper.

The transition to low-carbon energy systems calls for robust decision-making tools that can plan and operate hybrid renewable energy systems under multiple, often conflicting goals, such as cost, emissions, reliability and self-sufficiency. Adapters addresses this need through a two-level decision architecture and optimisation model that combines detailed component representations (photovoltaic, wind, and battery storage), with conceptual extensions to other flexible resources. The framework is explicitly aligned with the sustainability objectives of the 2030 Agenda and EU energy policies by enabling transparent trade-offs between economic and environmental criteria and by promoting reproducible research through open models and explicit constraints. Recent contributions by some of the present authors have, on the one hand, reviewed the global diffusion and key features of energy communities with a specific focus on building-load modelling and management [

4], and, on the other hand, analysed the role of battery energy storage systems in providing ancillary services within Renewable Energy Communities [

22] and proposed a freeware digital platform to support REC design in the Italian virtual-sharing framework [

23]. Methodologically, our work builds on the extensive literature on hybrid renewable energy systems optimisation and microgrid planning and control, and connects it with digital-twin-enabled decision-making for energy systems [

24,

25,

26,

27].

Energy communities in Italy are defined by the legislative decree D.Lgs 199/2021 [

28], the CACER Ministerial Decree published on 23 January [

29], and the implementation rules released by the Italian Energy Service Manager GSE on 23 February 2024 [

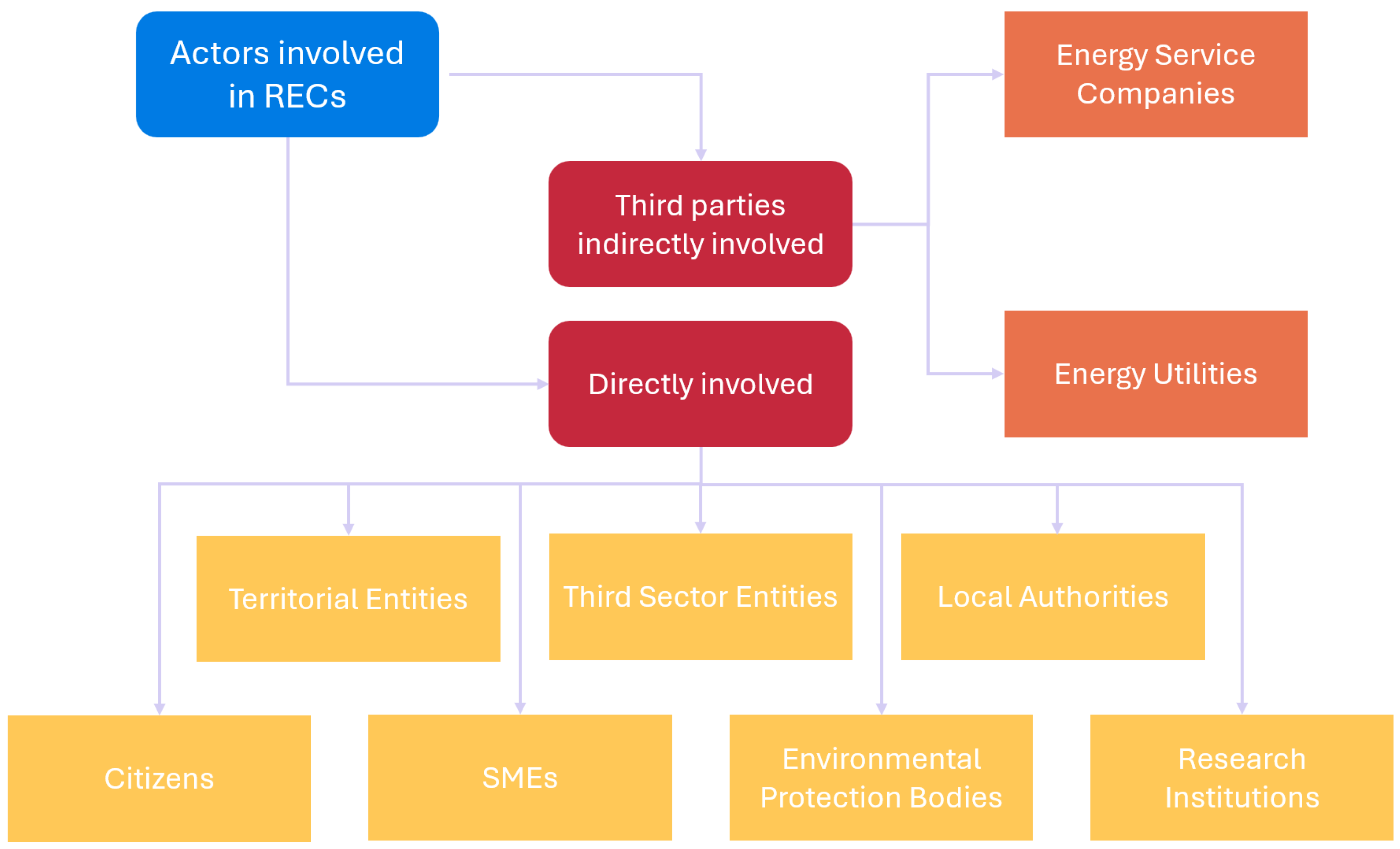

30]. In Italy, a Renewable Energy Community (REC) is defined as a legal entity formed by various stakeholders to produce, share, and consume renewable energy from installations not exceeding 1 MW. RECs aim to deliver environmental, economic, and social benefits to their members and the local territory. The REC operates within the geographical boundary of the local electricity market area, with self-consumed shared energy calculated based on the primary substation (HV/MV). Only the renewable energy production from plants under the community’s control is considered. Energy sharing within an REC is facilitated through a Virtual Model utilizing the public grid. Individuals and legal entities holding one electricity meter can participate in a REC; however, participation in the REC cannot constitute the primary commercial and industrial activity. Large businesses and energy utilities cannot join a REC. However, they can act as ’third-party’ entities and provide financial, technical, or management services to the community. A scheme is shown in

Figure 1.

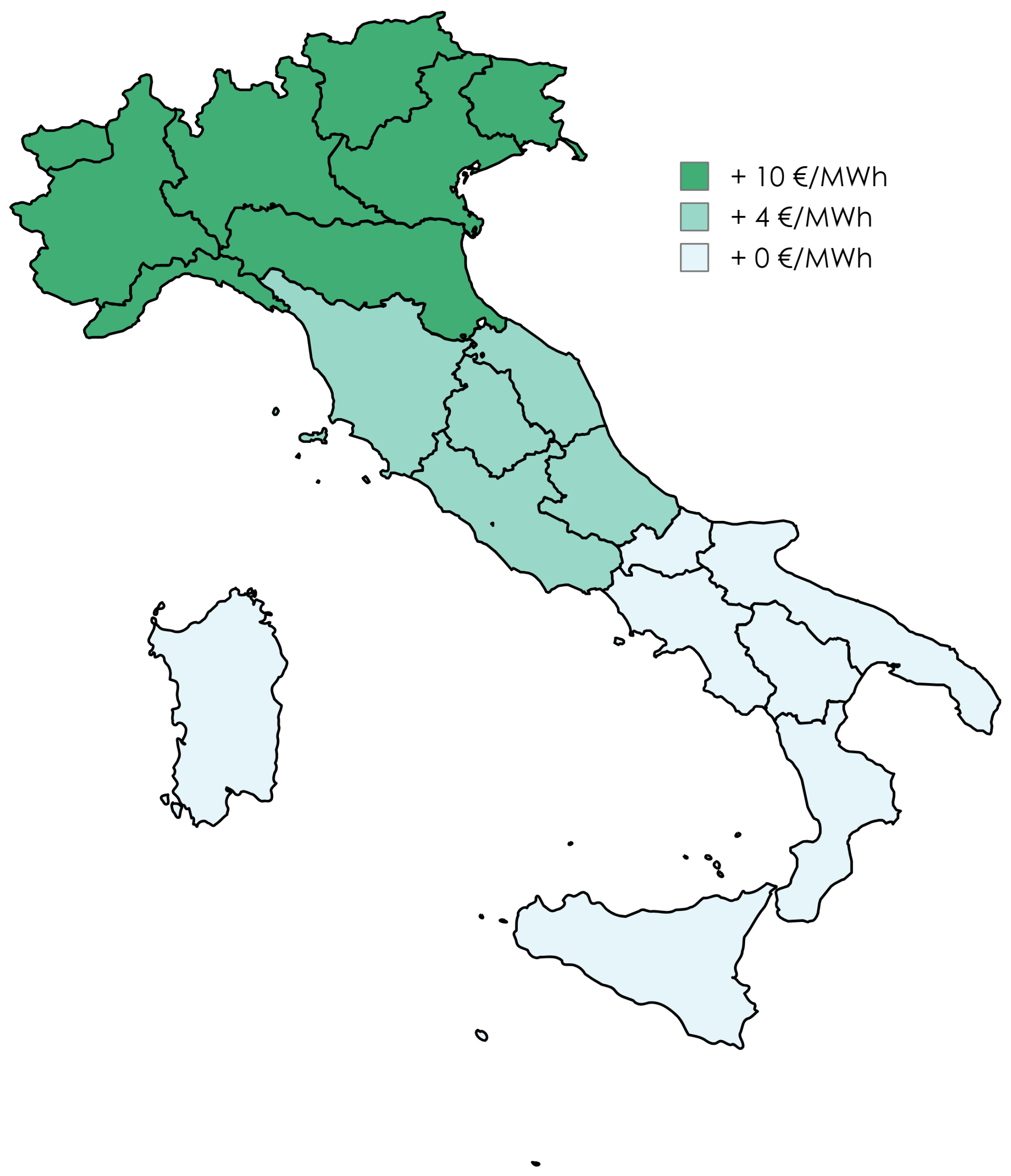

RECs are also eligible for an incentive comprising a fixed component, dependent on the plant size, and a variable component, linked to the zonal energy price as shown in

Table 1 and

Figure 2. This incentive is provided as a premium tariff, recognized for a period of 20 years, and is applicable to the shared self-consumed energy from eligible plants [

31].

Considering the definition of RECs and their possible structures, the objectives when constituting an energy community can vary significantly depending on the promoting legal entity. For instance, if public or local actors promote the REC, they are likely to opt for a top-down approach, emphasizing environmental and social benefits and their impact on the territory. On the other hand, external promoters will probably follow a bottom-up approach, facilitating horizontal community models and prioritizing actions aimed at energy and economic savings, directly benefiting individual consumers.

In this work, we present Adapters, a two-level decision-making tool for the design and operation of RECs. The framework is illustrated through prototype single-household case studies that are representative of typical European distribution networks, rather than of a specific geographical location.

The tool presented in this paper has been designed to be suitable with the novelty related to the definition of the RECs. The tool is flexible and aims at meeting the requirements of the various actors that may promote the creation of a REC. Computing the optimal design of the REC considering and assigning a weight to the various KPIs, the tool allows us to define the optimal size of the energy community both when following the top-down and bottom-up approach.

2. Materials and Methods

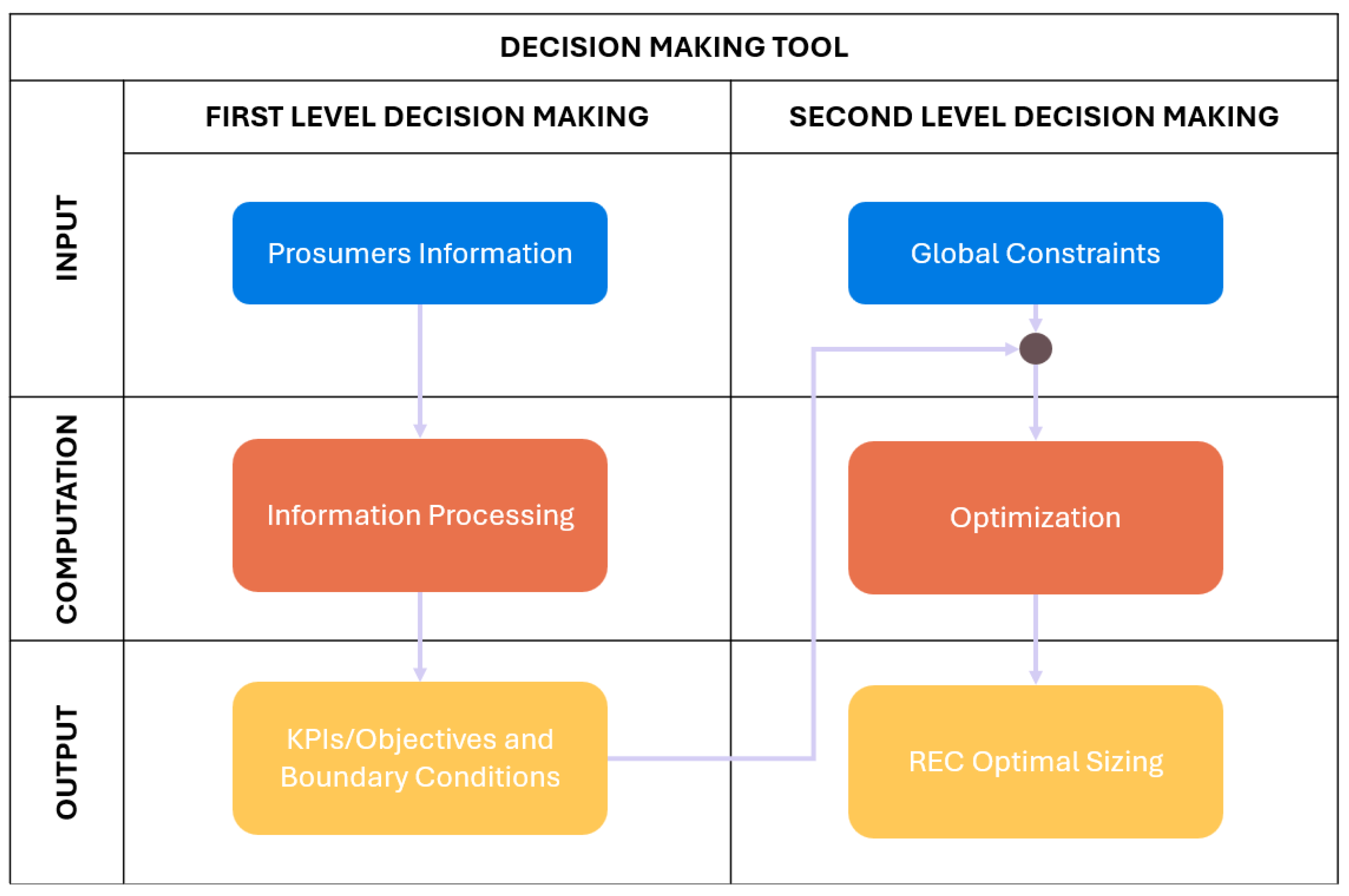

The decision-making tool has been developed to provide a software solution for the development of energy communities considering the Italian case. The tool provides possible configurations for potential energy communities considering some KPIs prior established by the potential prosumer of the energy community. The solution is therefore not unique; it depends on the KPIs that community members assign a higher weight to. The objective of the tool is to be a flexible instrument able to meet the various needs of the prosumers during the complex phase of the energy community design and development. The decision-making tool has been developed considering multiple levels. The first level analyses the potential energy community; it involves directly the future prosumers in terms of techno-economic potentials and individual objectives that will contribute to the definition of the KPIs. The second level regards the computation of the solution that will be proposed at the end of the process. In this case, considering the inputs provided by the first level, the optimisation algorithm will establish the boundaries conditions and assign the value to the problem variables.

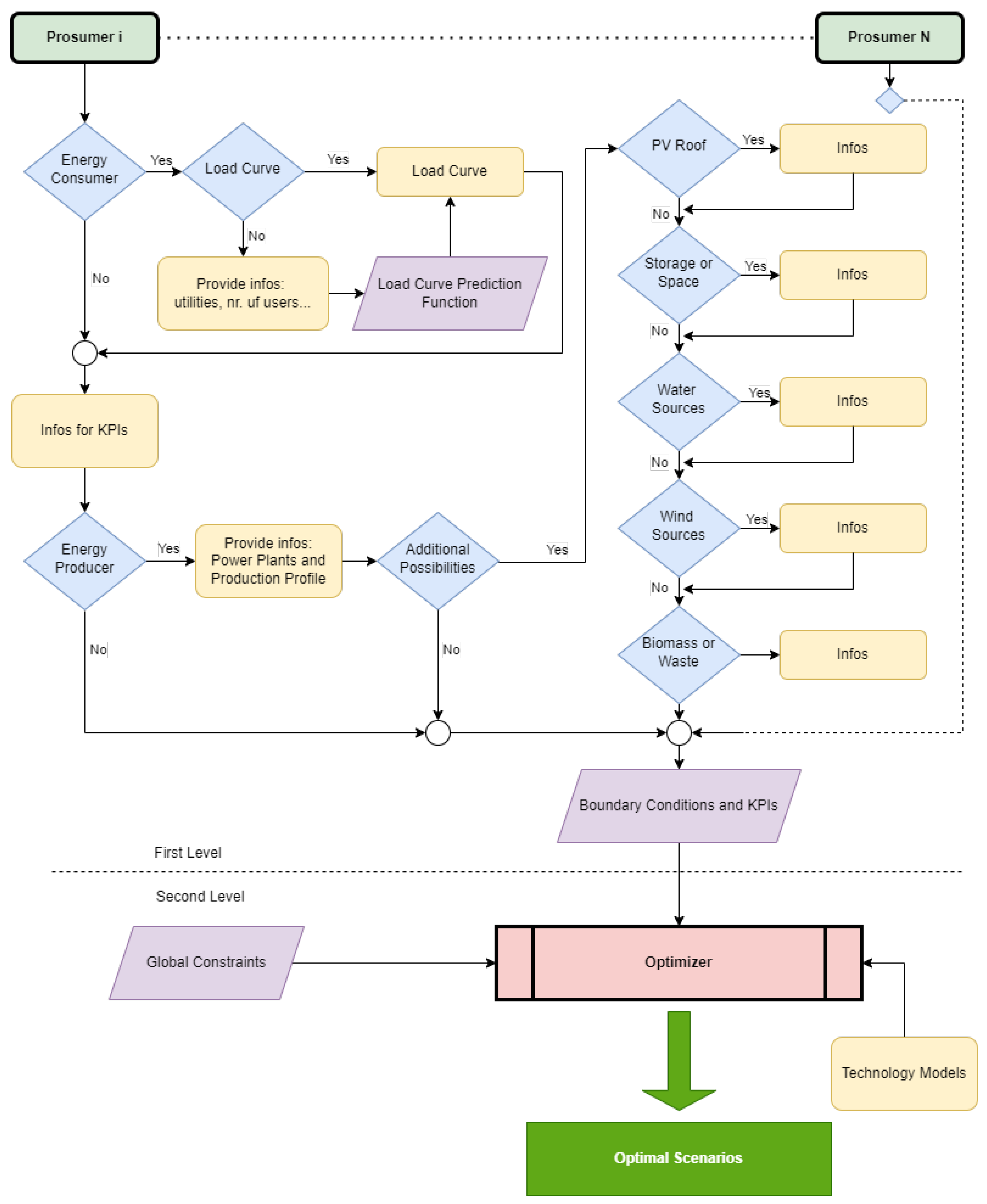

2.1. Decision-Making Tool

The decision-making tool has been developed as a software solution to support the development of energy communities in the Italian context. It provides possible configurations for potential energy communities based on a set of KPIs defined in advance by the prospective prosumers. The resulting solution is therefore not unique; it depends on how the community members weight the different KPIs. The objective of the tool is to be flexible enough to accommodate the diverse needs of prosumers during the complex design and development phase. A scheme is depicted in

Figure 3, while a flowchart of the process is shown in

Figure 4. The information gathered during the first decision-making aim at profiling the various prosumers. They are asked to provide information regarding their use of energy in order to understand whether they are industrial prosumers, households, or only energy providers. They are asked to provide information about the target of the REC and what they want to achieve in order to define the KPIs and the boundary conditions. Finally, they also have to provide information regarding the renewable energy technology that they eventually own or that they are keen to install in order to define the renewable energy technology potential if the future REC. In

Section 2.2, the details of this process will be fully described.

2.2. First- and Second-Level Decision-Making

As described in

Section 2.1, the tool has been designed considering two decision-making levels. The first level involves directly the actors of the REC defining the KPIs and the objectives of the REC, the second level computes the optimal sizing of the REC considering the inputs of the first decision-making level.

The second level thus embeds the models of the renewable energy technologies involved in the process and the optimisation algorithm.

Figure 4 depicts a flowchart of the two levels.

The first level aims at gathering various information considering each potential actor of the REC. The information requested from each potential actor is the following:

Energy Consumer: Identification of Prosumer Type. The first step involves identifying the prosumer typology, specifically determining whether the prosumer is an energy consumer. If so, the prosumer will need to provide the load curve to define the load profile. Alternatively, they must supply sufficient information to compute the load profile.

Information to set the KPIs: the second step is related with the definition of the KPIs. The prosumer will have to provide information about its personal targets and the targets of the energy community. This information will then be used to define the objectives for the optimisation algorithm of the second level.

Energy Producer Identification: in this step, energy producers or potential energy producers among the prosumers are identified. Current energy producers are asked to provide detailed information about their power plants. This includes specific data on their production profiles, such as capacity, production patterns, and efficiency metrics. Prosumers who do not yet produce energy are requested to supply information that will help assess their potential to install a power plant. This information may include the site characteristics (e.g., location and available space) and the interest in specific types of energy production (e.g., solar, wind, and biomass). By gathering this information, the aim is to better understand the current and potential energy production landscape, facilitating informed decisions on energy production and consumption within the community.

The conceptual scheme in

Figure 3 summarizes the two-level architecture, while the detailed flowchart in

Figure 4 shows how individual prosumer data are processed into boundary conditions and KPIs.

2.3. Multi-Objective Optimisation Problem

The system-level optimisation problem solved by Adapters combines the contributions of all energy components and prosumers into a single multi-objective formulation. Let denote the set of time steps and the set of energy sources and technologies included in the problem (grid connection, photovoltaic plants, wind plants, battery storage systems, dispatchable units, etc.). For each component , the corresponding model provides (i) a vector of power injections or withdrawals for all , (ii) an investment cost , (iii) an operating cost , and (iv) an annual CO2 emission term .

In addition to these component-level quantities, the formulation includes variables for the net power exchange with the upstream grid and, where required, for unserved energy. Grid imports and exports are represented within the grid component model, while a non-negative variable can be used to capture any residual mismatch between demand and supply at time t that cannot be covered by the available technologies. In the ideal case, the optimisation drives to zero, but keeping this variable explicit allows one to quantify infeasibilities or deliberately undersized systems.

The total annual cost

is given by the sum of investment and operating costs over all components and time steps:

where

denotes the non-negative part of the net power imported from the grid at time

t,

is the time-dependent energy tariff and

is the time-step duration. Investment and operating costs for each technology are computed by the corresponding component models, as detailed in

Section 2.4. In the current formulation, possible revenues from incentive schemes (such as the REC premium for shared energy) are not subtracted from

and are instead discussed qualitatively.

Total annual CO

2 emissions are obtained by summing the contributions of all emitting components:

where

is typically computed as the product of energy consumption and a technology-specific emission factor (for example, for grid electricity or diesel fuel), while renewable generation and storage are assumed to have zero operational emissions.

The total amount of unserved energy is defined as

which represents the energy demand not served by available resources over the optimisation horizon.

These three quantities are combined in a weighted-sum multi-objective function:

The weights

are provided by the first decision-making level (stakeholder preference elicitation) and then applied in the optimisation level. Because the three objective terms are expressed in different units (EUR, kgCO

2, and kWh), we minimise a dimensionless weighted sum obtained through normalisation:

where

,

, and

. The reference values are computed from the grid-only baseline configuration over the same horizon, ensuring interpretability of weights and preventing numerical-scale dominance.

The objective Equation (

4) is minimised subject to (i) a system-level power balance constraint that enforces equality between the total demand and the sum of all component power contributions and unserved energy at each time step; and (ii) the side constraints associated with each technology model (capacity limits, state-of-charge dynamics for storage, minimum and maximum power, logical activation constraints, cyclicity conditions, etc.). All these constraints are generated automatically from the component models and passed to the underlying optimisation engine, as summarised in

Section 2.6.

2.4. Technology Models

Adapters include explicit models for a set of core technologies that are particularly relevant for RECs: photovoltaic generation, wind generation, battery energy storage, grid exchange, and generic dispatchable units modelled as internal combustion engines (ICEs).

Photovoltaic (PV) systems can be either existing or potential. Existing PV installations are represented by exogenous production curves, while potential PV systems are characterised by location, available area, orientation, and technology. For potential PV, the model selects the number of panels (subject to area constraints) and computes hourly power output by combining pre-computed irradiance profiles with panel efficiency and balance-of-system factors. Investment costs are modelled as a linear or piecewise-linear function of installed capacity, while operating costs are proportional to installed power; operational CO2 emissions are assumed to be zero.

Wind power plants follow a similar structure. Existing plants are described through fixed production curves, whereas potential plants are defined by an available land area and geographical coordinates. Hourly wind speed data are mapped to a turbine power curve to obtain power output per turbine; the model then chooses the number of turbines, subject to spacing constraints derived from rotor diameter and available area. Cost and operational emission assumptions mirror those used for PV, with zero operational CO2.

Battery energy storage systems (BESS) are represented with explicit charging and discharging variables and a state-of-charge (SoC) trajectory. For potential batteries, the model decides the installed capacity and the initial SoC, subject to upper and lower bounds and a daily cyclicity constraint. Separate charge and discharge efficiencies are used to model round-trip efficiency. Investment costs are proportional to installed capacity (EUR/kWh), while operating costs and operational emissions are neglected in the present work.

The grid connection is modelled as a bidirectional interface that can import and export power. For each time step, a real decision variable represents net grid exchange, which is decomposed into imports and exports. Imports contribute to the cost through the tariff and to CO2 emissions through an emission factor; exports can be tracked but are not remunerated in the current formulation. Aggregate indicators such as total energy consumption from the grid, net energy balance, and total energy throughput can be computed from the grid variables.

Dispatchable fossil-fuelled generation is represented through an ICE model. For each ICE unit, a Boolean variable indicates whether the unit is on or off at each time step, and the power output is bounded by the nominal power. Fuel consumption is computed from power, efficiency, and fuel heating value; emissions are obtained by multiplying fuel use by a specific emission factor. Existing ICE units are treated as sunk investments, with no additional capital cost.

In the current version of Adapters, the optimisation problem explicitly includes photovoltaic generation, wind generation, battery energy storage systems (BESS), grid exchange, and generic dispatchable units (modelled as ICEs). Other technologies that are relevant for RECs, such as pumped-hydro storage, hydrogen production and storage chains, and electric vehicles with vehicle-to-grid (V2G) capability, are already foreseen at the conceptual level in the architecture and in the input data structures, but are not yet represented by detailed component models. These technologies are therefore not activated in the case studies discussed in this paper and are left as extensions for future work.

Photovoltaic systems, wind turbines, and internal combustion engines are modelled as single-bus generators whose hourly power outputs

are either taken from pre-computed production curves (for existing systems) or obtained by multiplying technology-dependent specific production profiles by sizing variables (number of PV panels, number of wind turbines, and ICE on/off status). These power profiles are then directly plugged into the power balance Equation (

6). Technology-specific side constraints (such as limits on the number of panels fitting a given roof area or the maximum number of turbines allowed on a plot of land) are handled through additional linear constraints on the sizing variables and all key parameters are reported in

Table 2.

2.5. Constraints

The optimisation is formulated over a discrete time horizon with an hourly resolution ( h). In the prototype experiments reported in this paper, we consider a single representative day () to validate the modelling and optimisation pipeline with compact instances; whenever “annual” indicators are reported, they are annualised by scaling representative-day results by 365 (i.e., assuming 365 identical days). This annualisation is used only to express KPIs on a familiar yearly basis and does not aim to capture seasonal variability. For full REC design studies, Adapters can be run on longer horizons (e.g., 8760 h time series) or on sets of typical days with frequency weights; this extension is discussed as a limitation and future work.

For each time step , we denote by the electricity demand of the prosumer, by the power output of DER (PV, battery, wind turbine, and internal combustion engine), and by the net power exchange with the grid. Positive values of represent imports from the grid, and negative values exports to the grid, consistently with the implementation.

At each time step, the nodal power balance at the prosumer (or aggregated prosumer) node is written as

The demand profile is exogenous and derived from the measured (or synthetic) hourly load curve, while the DER outputs and the grid exchange are decision variables determined by the solver.

In order to correctly model costs, emissions, and grid independence, the net grid exchange

is conceptually split into non-negative import and export components.

so that

and

. In the implementation, this is realised using piecewise-linear expressions based on conditional (

ite) operators on the signed variable

.

The annual energy imported from the grid, the total net energy balance, and the total energy transmission at the grid connection point are then

These quantities are used, respectively, to compute the operational expenditure, the net energy balance, and the grid independence indicator in the objective function and performance indicators.

The battery is modelled using a standard state-of-charge (SoC) formulation, with separate charge and discharge powers and round-trip efficiency. Let

denote the state of charge at the beginning of time step

t,

the charging power,

the discharging power, and

the battery energy capacity. The evolution of the state of charge is given by

where

and

are the charge and discharge efficiencies, respectively. In the implementation, the product

is set to

(with

and

).

The state of charge and battery power are bounded as

where

is an optional bound on the (dis)charge power. A cycle-consistency constraint is imposed between the first and last time step of the representative day,

so that the battery ends the day with the same state of charge with which it starts. For existing batteries, the capacity

is fixed, whereas for potential new batteries, it is a decision variable constrained by the available volume,

, where

V is the volume (m

3) made available for the installation. To avoid simultaneous charging and discharging of the battery, we enforce

which is implemented via additional auxiliary variables and logical constraints in the solver.

The net power contribution of the battery to the power balance Equation (

6) is then

and enters the sum over

.

2.6. Software Implementation

The Adapters framework is implemented in Python and organised in modular components. Each energy technology is represented by a dedicated module. Input data and configuration parameters are provided through JSON files, which specify the prosumers, the available and existing energy technologies, the time series for demand and resource availability, and the chosen objective weights.

The current implementation uses Python 3.11, the Z3 solver 4.15, and standard scientific libraries NumPy 2.3.4, which are documented in the repository to support exact reproducibility.

At run time, the JSON description of a problem instance is parsed and mapped to a set of energy source objects, each exposing a common interface for power output, costs, emissions and side constraints. These objects are then encoded as decision variables and constraints for a Satisfiability Modulo Theories (SMT) solver based on Z3 [

32]. The solver class instantiates the backend, collects all component-level constraints, adds the system-level power balance and the multi-objective function, and finally retrieves and post-processes the solution for reporting and visualisation.

This separation between high-level JSON problem descriptions, technology-specific modules, and the core solver facilitates reproducibility and extensibility: new components can be added by implementing the same interface, without modifying the rest of the optimisation pipeline. The mathematical models presented in

Section 2.4 are therefore directly reflected in the software implementation.

2.7. Case Study

We adapt the general formulation in

Section 2 and instantiate it for a set of prototype single-household scenarios. Five distinct residential configurations are considered, encoded as six JSON problem instances that differ in terms of available RES and primary optimisation objective. In all cases, the household is simulated in the Province of Bozen–Bolzano (latitude 47.16

∘ N, longitude 11.24

∘ E) and is connected to the low-voltage distribution grid. All prototype cases share the same grid tariff of 0.10 €/kWh and a grid emission factor of 0.02 tCO

2/kWh.

The electricity demand of each household is represented by an hourly load curve over a single representative day with a total daily demand of 10 kWh. In the case studies below, the optimisation is carried out over this 24 h representative day only, and yearly energy and cost indicators are obtained by scaling the representative-day results to one year (assuming 365 identical days). This common load profile allows us to isolate the effect of different DER portfolios and optimisation objectives.

In the first prototype case, the household Case study 1 has no existing distributed generation or storage and no additional DER options. The only available supply option is the connection to the distribution grid. Although the JSON specification uses “grid independence” as a placeholder optimisation objective, this case is used in the paper as a pure baseline where all demand is supplied from the grid at the exogenous tariff, providing a reference cost and emission level against which the other cases can be compared.

In the second case, the household Case study 2 is equipped with an existing ICE generator fuelled by diesel (nominal power 5 kW, nominal efficiency 0.5), and is also connected to the grid. No additional DERs can be installed. The optimisation objective is the minimization of operational CO2 emissions. Given the relatively low emission factor of the grid and the high specific emissions associated with diesel generation, this prototype case is designed to show that the optimal strategy is to rely exclusively on the grid and avoid operating the ICE, despite its sunk capital cost.

The third prototype configuration (Case study 3) considers a household that currently has no DERs installed but can host a small PV system on the balcony (south-oriented, 5 m by 1.5 m, technology “H-A”) and a battery system in the cellar. This configuration is instantiated in two separate optimisation runs, using identical input data but different primary objectives: (i) minimisation of operating expenditures (OPEX), and (ii) maximisation of grid independence. In both runs, the tool selects the PV and battery sizes and their hourly operation schedule. These two variants illustrate how different stakeholder preferences for cost versus self-sufficiency lead to different optimal DER configurations and operating strategies for the same household.

In the fourth case, the household Case study 4 already owns a rooftop PV system, represented by an exogenous hourly production curve over the same representative day. The prosumer can additionally install a battery in the cellar (volume 2) to increase self-consumption and reduce dependence on the grid. The optimisation objective is grid independence, and the problem is framed as “given PV, find the battery size and operation that maximizes grid independence”, subject to the standard energy balance and storage dynamics constraints. This case showcases how Adapters can support sizing of storage assets when generation is already fixed.

The fifth prototype case represents Case study 5, a household located at slightly higher altitude (789 m a.s.l.) with access to a nearby field where a small wind park can be installed (area 10 m by 5 m). As in previous cases, a battery in the cellar (volume 2) is also a candidate technology. There are no existing DERs. The optimisation objective is again grid independence, so that the tool jointly decides on the capacity of the wind turbines and the battery, as well as their operation, to reduce grid imports while satisfying hourly demand. This case highlights the flexibility of the modelling framework in handling non-solar renewable sources.

Taken together, these five prototype household configurations, instantiated through six JSON problem instances, cover different combinations of existing and candidate technologies (none, dispatchable diesel generation, PV, wind, and battery storage) and different stakeholder objectives (cost, emissions, and grid independence). They provide a compact yet diverse test set to validate the correct implementation of the optimisation model and to demonstrate how Adapters can be used as a decision-making tool at the single-prosumer level before scaling up to full RECs.

Constraints and objectives are encoded in an optimisation backend and solved from JSON inputs; forecasts for demand/RES are integrated and can be improved via data-driven models [

33,

34].

3. Results and Discussions

The optimisation framework is first evaluated on the single-household prototype scenarios described in

Section 2.7. Each scenario is encoded as a JSON problem instance and corresponds to one of the five prototype configurations listed in

Table 3. All runs refer to a residential prosumer located in the Autonomous Province of Bozen–Bolzano, connected to the low-voltage distribution grid and characterised by a common reference daily load profile with a total demand of 10 kWh. The focus is on how different DER portfolios and objective functions affect grid imports, operational costs, and operational CO

2 emissions.

For each case, the optimisation problem is formulated over a 24 h representative day with hourly resolution, and yearly KPIs are reported only when explicitly annualised by scaling the representative-day results by 365 (

Section 2). The objective weights

in Equation (

4) are selected to reflect the primary objective listed in

Table 3, while keeping small but non-zero weights on the remaining terms to avoid degenerate solutions. In the current implementation, we focus on

a pure grid-supplied baseline,

an emissions-oriented configuration with a diesel ICE,

a cost-oriented configuration with balcony PV and battery storage.

The corresponding optimisation runs are encoded as JSON files in the Adapters repository and can be reproduced from the open-source code base.

Table 4 summarises the six JSON problem instances used in the numerical experiments. They cover the five prototype household configurations of

Section 2.7: a grid-only baseline (Case study 1), a configuration with an existing diesel internal combustion engine (ICE) (Case study 2), two variants of the balcony PV and battery case (Case study 3, cost-oriented and grid-independence-oriented), a household with existing rooftop PV and candidate battery (Case study 4), and a configuration with candidate wind park and battery (Case study 5).

denote the daily net energy imported from the grid, while

denotes the total daily energy exchanged at the point of connection (imports plus exports).

Table 4 reports, for each JSON instance, the daily energy imported from the grid, the total energy exchanged at the point of connection, and a simple grid independence index. The latter is defined as

where

is the daily energy imported from the grid and

is the daily household demand. A value of GI close to 100% indicates a nearly self-sufficient configuration (low imports), while GI close to 0% corresponds to full reliance on the grid. Grid exports do not increase GI; export-dominated solutions are therefore characterised using complementary indicators (e.g., exports and grid transmission). The table also reports the optimised daily OPEX and operational CO

2 emissions. For simplicity, OPEX is computed here as the energy purchased from the grid at the flat tariff of 0.10 €/kWh, neglecting fixed charges and possible remuneration for exported energy, and CO

2 emissions are obtained by multiplying grid imports by the emission factor of 0.02 tCO

2/kWh.

The grid-only baseline unsurprisingly exhibits full dependence on the grid, with daily imports of 10 kWh, zero grid independence (GI = 0%), and a daily OPEX of 1.00 €. The emissions-oriented configuration with an existing diesel ICE yields exactly the same energy and cost figures: the optimiser never dispatches the ICE, so that all demand is still covered from the grid and operational CO2 emissions remain equal to those of the baseline (about 200 kg/y in this toy example). This confirms that legacy dispatchable units with high specific emissions are not necessarily used in an optimal low-carbon configuration, even when they are already installed.

In the balcony PV and battery case (Case study 3), the optimiser can, in principle, select both the PV size and the battery capacity. However, under the assumed tariff and cost parameters, neither the grid-independence-oriented run nor the OPEX-oriented run installs additional DER capacity. Both runs therefore rely entirely on the grid, with daily imports of 9.8 kWh, a modest increase in grid independence (GI ≈ 2%), and a slightly lower OPEX of 0.98 units due to the slightly lower demand encoded in these instances. This illustrates how Adapters can return “no-investment” solutions when local generation and storage are not yet economically or environmentally justified for a single prosumer.

The rooftop PV and battery configuration is the only case in which battery storage is actually deployed. Given the exogenous PV production profile and the grid-independence objective, the optimiser installs a battery with a capacity of 5.52 kWh and uses it to shift surplus PV generation to evening hours. As a result, net grid imports over the year are reduced to zero, and the remaining energy exchange with the grid (0.34 kWh/y) is due to small residual exports at the point of connection. The grid independence index reaches 100%, and, under the simplifying assumptions adopted here, both OPEX and operational CO2 emissions are effectively zero.

Finally, the configuration with candidate wind park and battery also yields a no-investment solution. The optimiser does not install either wind capacity or storage, and the resulting performance indicators are very similar to those of the balcony PV runs: daily grid imports of 9.8 kWh, GI ≈ 2%, OPEX of 0.98 units, and emissions of about 196 kg/y. In this setting, the assumed wind resource and cost data are not sufficient to make small-scale wind economically attractive at the single-household level, but the same modelling framework can be reused to explore different tariff or incentive schemes.

In the Italian context, these trade-offs can be further interpreted in terms of the premium tariff for shared energy: solutions with higher renewable shares and lower grid imports tend to maximise the amount of energy eligible for the GSE incentive, potentially compensating part of the additional investment and operating costs associated with larger PV or storage capacities.

4. Conclusions

This paper has presented Adapters, a modular decision-making framework for the design and operation of hybrid renewable energy systems in the context of RECs. Rather than focusing on a single detailed case study, the work aims to position Adapters as a contextual tool that links multi-objective planning, component-level modelling, and online, data-driven adaptation within a coherent architecture. The formulation explicitly combines three objectives: total cost, CO2 emissions, and unserved energy. It allows users to explore trade-offs between economic performance, environmental impact, and reliability by tuning the corresponding weights.

On the methodological side, the framework builds on well-established models for key technologies such as PV, wind generation, battery energy storage, grid exchange, and dispatchable units, and embeds them in a common optimisation layer based on a SMT solver. Input data are provided through JSON descriptions of prosumers, technologies, and time series, which are translated into component-level variables and constraints and assembled into a system-level energy balance. This design supports transparency and reproducibility: all assumptions are expressed as explicit constraints, and the mapping from the problem description to the optimisation model is fully documented and open.

Beyond the specific prototype runs, the main methodological contribution is the formalisation of a two-level REC decision process into a transparent, constraint-explicit multi-objective optimisation workflow that supports reproducibility and modular extension towards community-scale and digital-twin-enabled analyses.

This work presents prototype single-household building blocks rather than a full multi-member REC instance. In addition, the numerical experiments use a representative-day horizon with annualised KPIs, which does not capture seasonal variability. Export remuneration and incentive revenues are not yet integrated into the cost objective, and the technology library is currently limited to a core set of components. These limitations motivate the next development steps, including 8760 h simulations (or weighted typical days), explicit modelling of incentive revenues, and scaling to heterogeneous multi-prosumer REC configurations.

From the application perspective, the prototype single-household case studies illustrate how Adapters can be used to test different stakeholder preferences (for example, prioritising cost versus grid independence) and to reason about the role of distributed energy resources in emerging RECs under realistic tariff and emission assumptions. In the small numerical examples considered here, the optimiser correctly identifies that new balcony PV, wind, and battery investments are not yet justified for a single prosumer under the assumed flat tariff, while adding storage to an existing rooftop PV system can almost eliminate annual grid imports and operational CO2 emissions. Although the present work has focused on a limited set of technologies and simplified operating scenarios, the architecture is general enough to be adapted to different national frameworks and to more detailed community configurations.

Future work will concentrate on four main directions. First, extending the library of component models to include pumped-hydro storage, hydrogen-based energy chains, and electric vehicles with vehicle-to-grid capabilities, in order to capture a broader range of flexibility options. Second, improving the treatment of uncertainty in demand, renewable generation, and prices, for instance through scenario-based or chance-constrained formulations. Third, addressing scalability issues when moving from prototype case studies to larger communities with many heterogeneous prosumers, possibly through decomposition or hierarchical control. Finally, strengthening the linkage with evolving REC regulations and incentive schemes, so that Adapters can support not only technology choices but also the co-design of business models and policy instruments in line with national and EU energy and climate goals.