Spatiotemporal Evolution and Driving Mechanisms of Production–Living–Ecological Space Coupling Coordination in Foshan’s Traditional Villages: A Perspective of New Quality Productive Forces

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- How do different dimensions of new-quality productive forces differentially drive the spatiotemporal evolution of the coupling coordination degree of traditional villages’ PLE spaces?

- (2)

- What are the driving mechanisms and pathways? Do interactive effects exist among factors?

- (3)

- What insights do these findings offer for expanding the spatial governance implications of new-quality productive forces and guiding sustainable rural development at the micro-scale?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Framework and Methods

2.1.1. Research Framework

2.1.2. Research Methods

- (1).

- Land Use Transformation

- (2).

- Spatial Functional Evaluation Method for the PLE System.

- (3).

- Spatial Coupling Coordination Model for “Three Functions” in Traditional Villages

- Coupling Degree (Formula (2)):

| Coupling Degree | Coupling Type | Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| [0, 0.3] | Low-Level Coupling | The three functions develop independently with weak interconnections and insufficient synergy, potentially leading to dominance by one function |

| (0.3, 0.5] | Antagonistic Coupling | The three functions have minimal connections, with prominent conflicts between them and a lack of coordination. |

| (0.5, 0.8] | Adjustment Phase | The three functions are relatively well-connected, with interaction between them. They are in an adjustment phase and not very stable. |

| (0.8, 1] | High-level coupling | The three functions work in close coordination, with stable communication and collaborative development. |

- 2.

- Coordination Degree (Formula (3)):

| Value Range | Classification Type | Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| (0, 0.2] | On the verge of imbalance | Only one of the PLE spatial functions dominates, while other functional land spaces are squeezed, leading to dysfunction in the PLE spatial functions |

| (0.2, 0.4] | Mild imbalance | One PLE spatial function holds a dominant position, with the PLE spatial functions being uncoordinated. |

| (0.4–0.6] | Borderline dysfunction | Addressing issues arising from the imbalance of production, living, and ecological functions through transforming production methods, enhancing living space quality, or improving the ecological environment |

| 0.6–0.8] | Moderately coordinated | Predominantly intensive production with significantly enhanced livability and ecological environment, featuring strong coordination and interaction among the PLE spatial functions |

| (0.9–1.0] | Highly Coordinated | The functions of the PLE spaces mutually reinforce each other, achieving symbiotic integration and orderly development of multifunctional spaces. |

- (4).

- Statistical Analysis Methods

- Entropy Method

- 2.

- Geodetector

2.2. Indicator System Construction

- (1)

- Innovation-Driven Development and Digitalization Level: Reflecting technology’s penetration into “production-living” spaces. Computer and mobile phone penetration rates indicate digital infrastructure coverage, while R&D expenditure intensity measures investment in industrial upgrading and spatial intelligent governance through technological advancement.

- (2)

- Human Capital and Factor Quality Upgrading: Demonstrates how labor force quality enhancement supports the optimization of the “production-living” spatial structure. Comprehensive assessment of indicators such as average years of education and labor productivity evaluates the impact of human capital improvement and income growth on spatial quality.

- (3)

- Factor Allocation and Output Efficiency: Focuses on the intensive and efficient utilization of “production space”, encompassing indicators such as per capita output value and land productivity to measure how optimized resource allocation enhances spatial economic benefits.

- (4)

- Green Sustainability and Ecological Support: Represents the degree of “ecological space” protection and green transformation, employing indicators like pesticide use per unit area (negative) and forest coverage to reflect ecological sustainability’s role in safeguarding spatial system coordination.

| Objective Layer | Criterion Layer | Indicator Layer | Symbol | Calculation Method or Data Source | Attribute |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| New Quality Productivity | Innovation- driven and digitalization level | Average Number of Computers Owned per 100 Rural Households at Year-End | X1 | Total number of computers owned/Total number of households | + |

| Average number of mobile phones owned per 100 rural households at year-end | X2 | Total mobile phones/total households | + | ||

| Level of technological innovation | X3 | Internal expenditure on research and experimental development (R&D) × (Total output value of agriculture, forestry, animal husbandry, and fishery/Regional GDP) | + | ||

| Upgrading Human Capital and Knowledge Factors | Average Years of Education for Rural Population | X4 | (Number of illiterate individuals × 1 + Number of primary school graduates × 6 + Number of junior high school graduates × 9 + Number of senior high school graduates × 12 + Number of college graduates and above × 16)/Total population aged 6 and above | + | |

| Labor productivity | X5 | Primary industry value added/Primary industry employment | + | ||

| Per capita disposable income of rural residents | X6 | Total Rural Residents’ Disposable Income/Rural Permanent Population | + | ||

| Factor Allocation and Output Efficiency | Agricultural Output Value per Capita | X7 | Total Output Value of Agriculture, Forestry, Animal Husbandry, and Fisheries/Rural Population | + | |

| Land output efficiency | X8 | Total agricultural output value/Total crop planted area | + | ||

| Grain Yield per Unit Area | X9 | Total Grain Output/Grain Sown Area | + | ||

| Agricultural electricity efficiency | X10 | Rural electricity consumption/Total output value of agriculture, forestry, animal husbandry, and fisheries | + | ||

| Green Sustainability and Policy Support | Pesticide Use per Unit Area | X11 | Total Pesticide Use (Converted to Pure Pesticide Equivalent)/Total Cultivated Land Area | − | |

| Forest coverage rate | X12 | Forest area/Total land area | + | ||

| Share of fiscal expenditure on agriculture, forestry, and water affairs | X13 | Local fiscal expenditure on agriculture, forestry, and water affairs/Local fiscal general budget expenditure | + |

2.3. Research Subjects and Data Sources

2.3.1. Research Subjects

2.3.2. Data Sources

2.3.3. Spatial Analysis Units and Data Processing Notes

- (1)

- Vector Boundary Extraction: Precise administrative boundary vector polygon data for each traditional village was digitally acquired based on high-resolution remote sensing imagery and field surveys.

- (2)

- Data Spatialization and Assignment: For spatially continuous data (e.g., forest coverage, grain yield per unit area), the “Zonal Statistics” tool in ArcGIS was used to calculate average values within each village boundary. For socioeconomic statistics (e.g., per capita disposable income of rural residents, average years of education for rural population), township-level or village-level statistical reports were prioritized for direct matching within data availability constraints. If only county-level data is available, assume relative homogeneity within the area and assign the county average to each village as an approximation, explicitly noting its reliability and limitations for trend analysis in discussions. For point or line feature data (e.g., computers per 100 households, agricultural electricity efficiency), convert to continuous surfaces via kernel density analysis or service radius analysis before extracting village averages.

- (3)

- Geographic Detector Application: Using the village-indicator panel data processed above as input, the Factor Detector module of the Geographic Detector quantitatively identifies the explanatory power (q-value) of each driving factor in spatial differentiation of the PLE spatial coupling coordination degree.

3. Results and Analysis

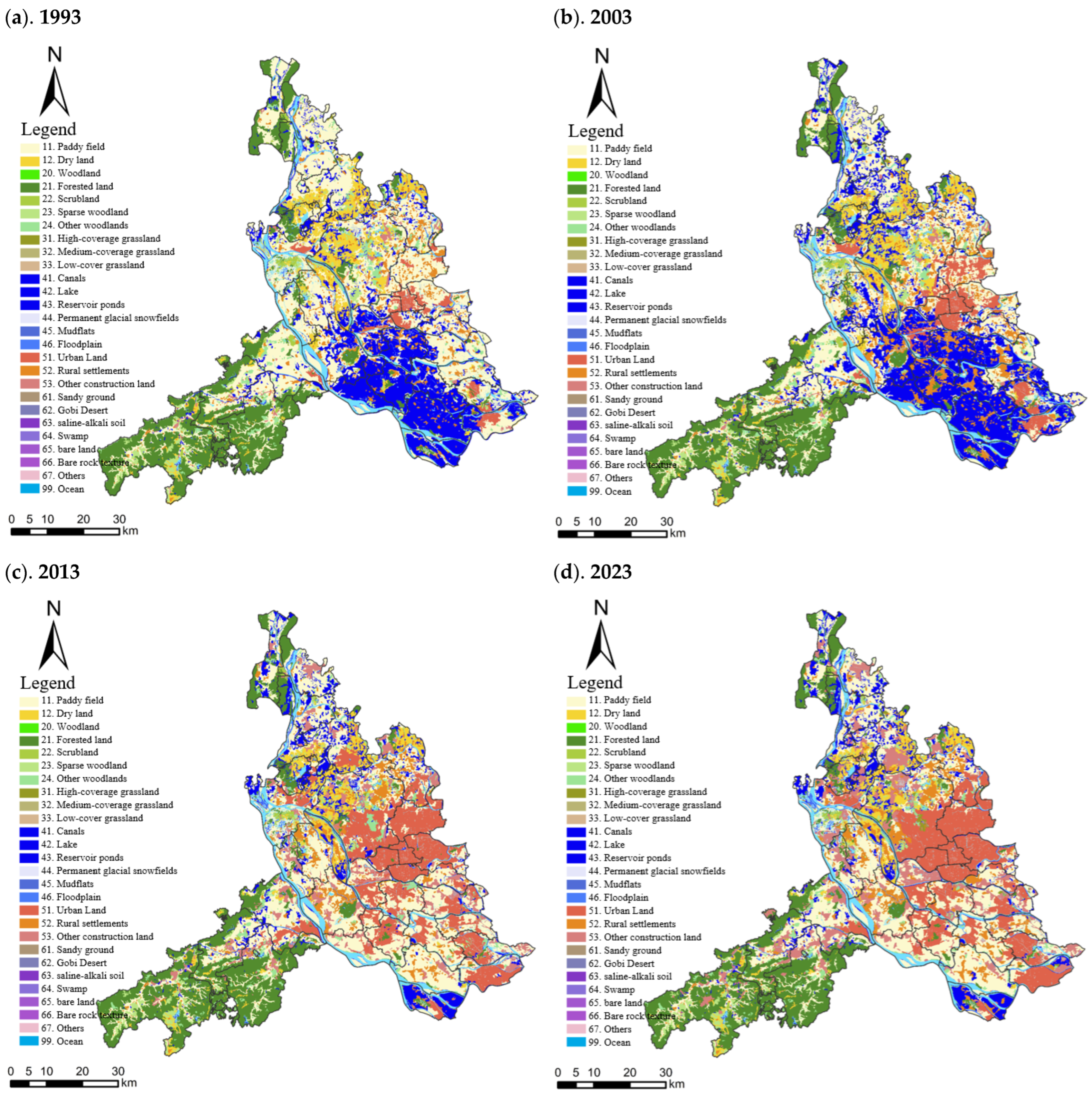

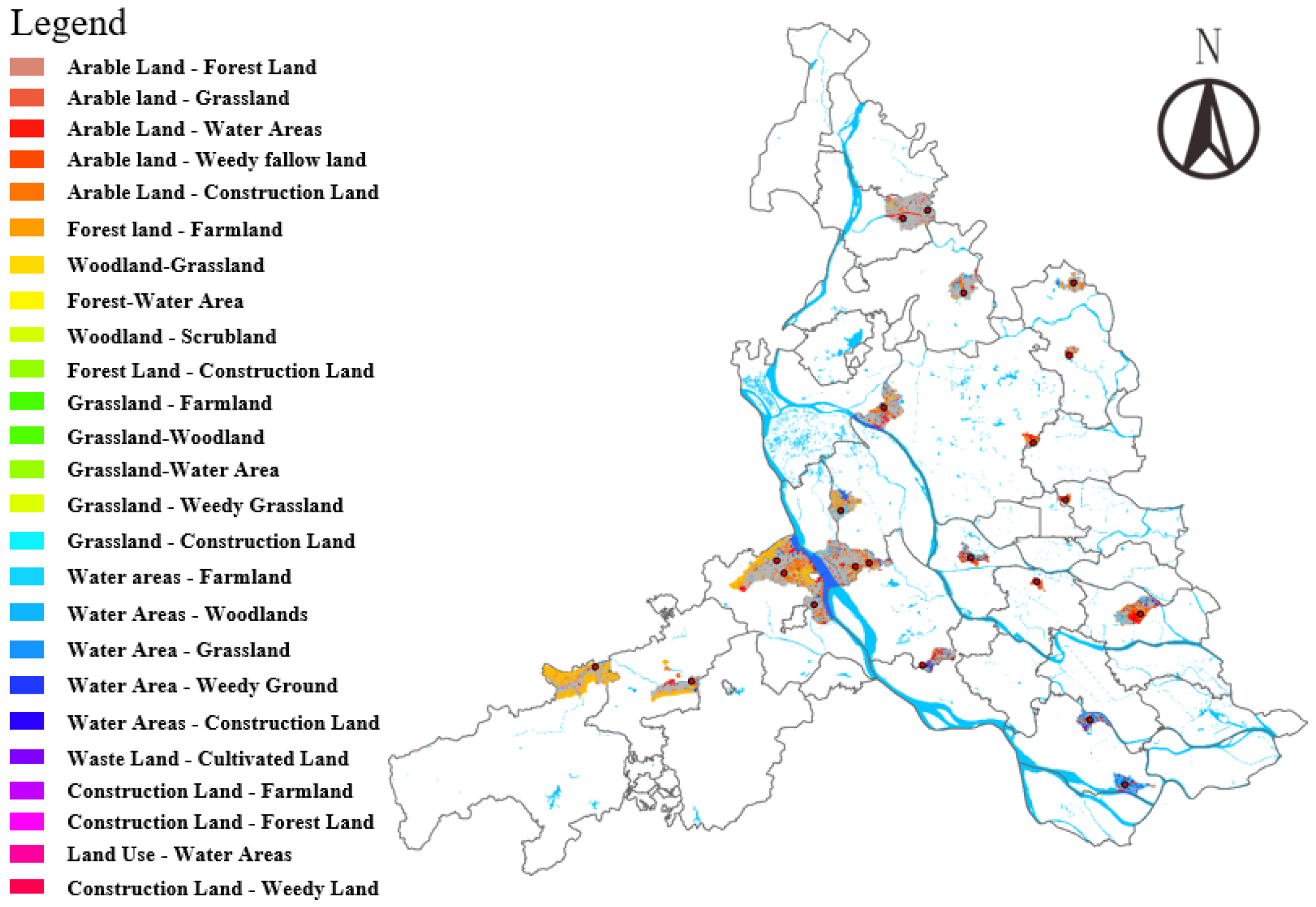

3.1. Spatial Distribution and Structural Changes of the PLE Spaces

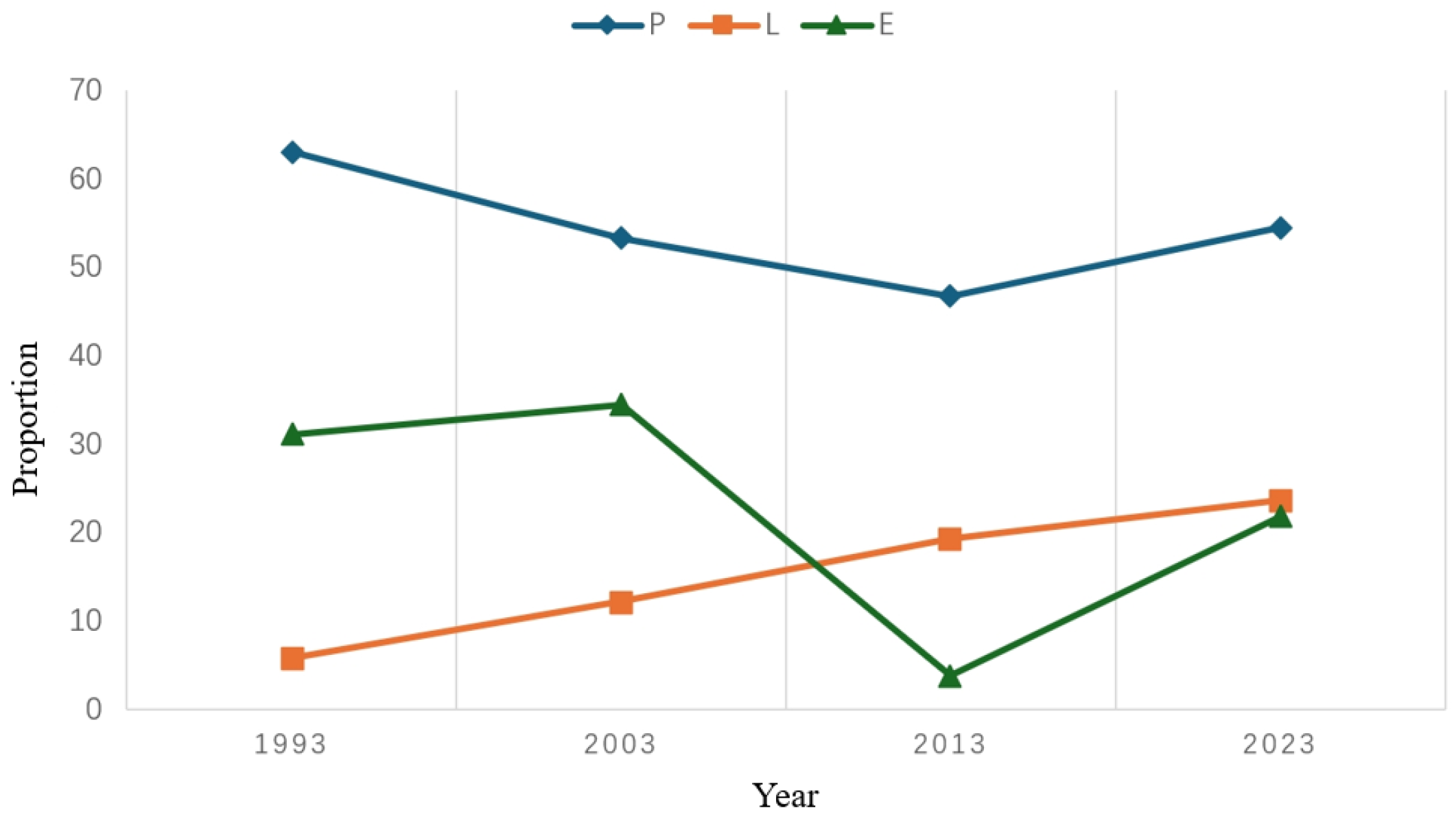

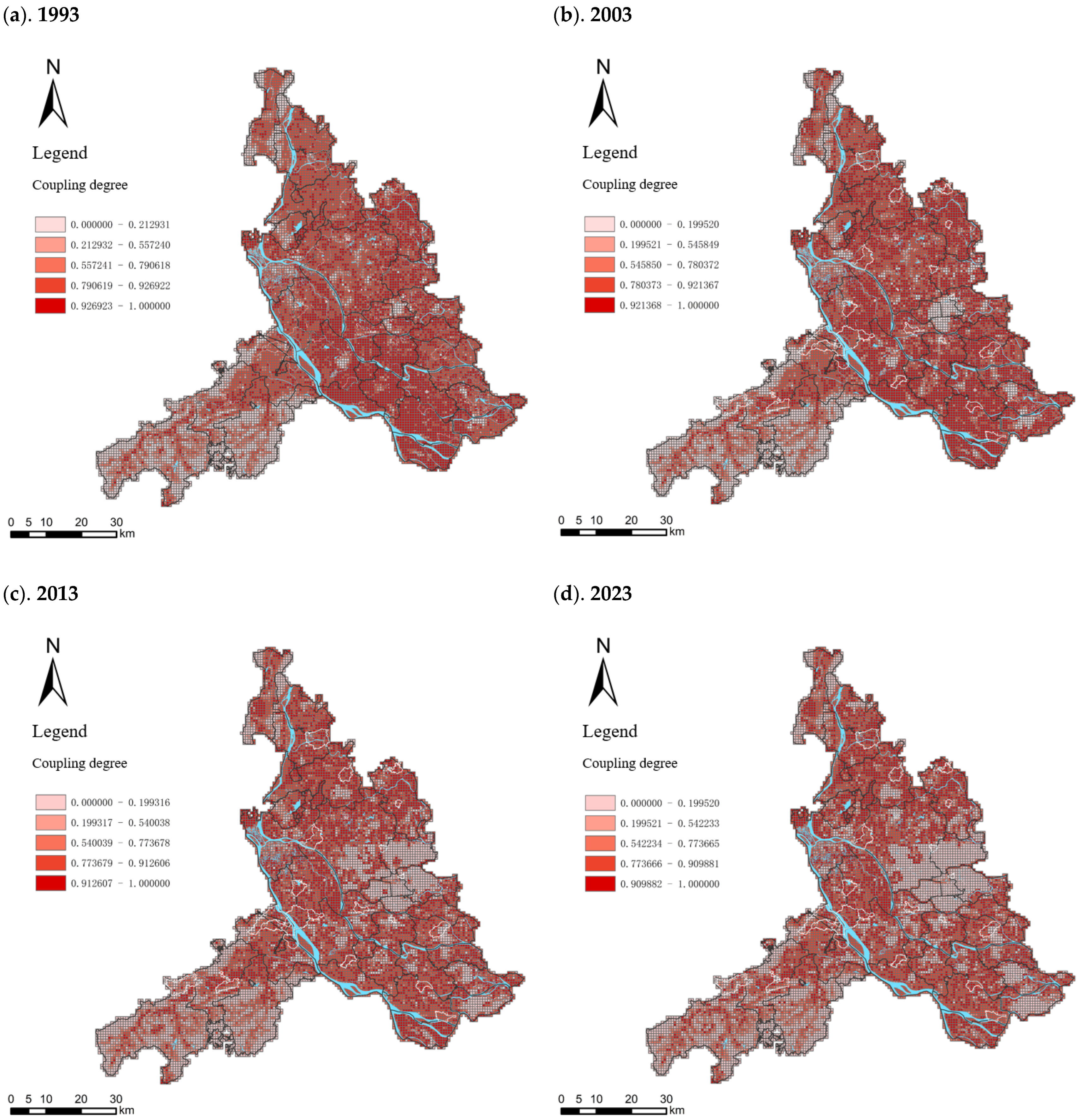

3.2. Spatiotemporal Evolution of PLE Spatial Coupling

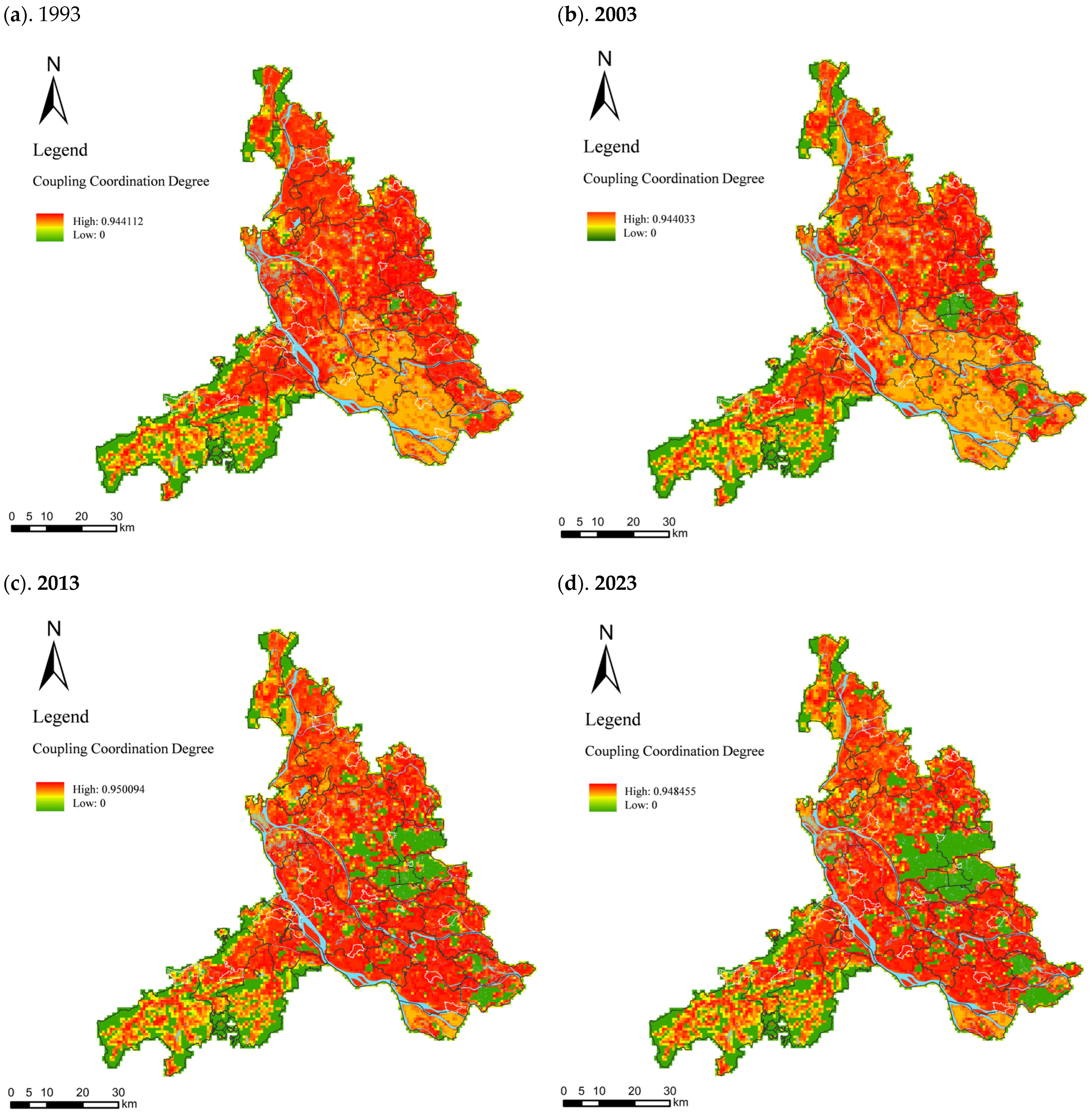

3.3. Spatial Coupling Coordination Degree and Evolutionary Characteristics of the PLE Spaces in Traditional Villages

3.4. Spatiotemporal Analysis of Functional Coupling Coordination Among Production–Living, Living–Ecological, and Production–Ecological Spaces

3.5. Analysis of Driving Factors for Functional Coupling Coordination Degree in PLE

4. Discussion

4.1. Dialogue and Extension of Existing Research

4.2. Mechanisms and Bottlenecks of New Quality Productivity Factors

- (1)

- Mismatch between technology supply and operational scale: Many green technologies and smart equipment (e.g., large-scale smart irrigation systems, centralized wastewater treatment facilities) are designed for scaled, continuous production scenarios, making them ill-suited for traditional villages characterized by fragmented land, dispersed property rights, and small-scale operators. For instance, promoting precision irrigation technologies in villages with scattered farmland often faces “diseconomies of scale” due to small unit areas and high infrastructure investment costs [61].

- (2)

- Disconnect between policy standards and local practices: Some top-down ecological conservation or technology promotion policies adopt uniform standards and assessment metrics without adequately considering differences in resource endowments, development stages, and community capacities across villages. This leads to “institutional incompatibility” during local implementation. For instance, while strictly restricting all development activities in ecologically sensitive areas, failing to provide differentiated alternative livelihood or ecological compensation schemes may instead dampen community enthusiasm for conservation, exacerbating the “disembedding” of conservation from development.

- (3)

- Mismatch between technology application and social organization forms: Digital platforms and networked services typically rely on a certain user density and activity level. However, in villages experiencing population outflow and pronounced aging, it is difficult to achieve the user scale and social interaction foundation required for sustainable operation, leading to difficulties in the “implementation and sustainability” of digital projects.

4.3. The Phenomenon of “Idleness” in Spatial Reconfiguration and Systemic Disembedding

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- Significant spatial restructuring has been observed, with the continuous expansion of living space accompanied by the contraction of production and ecological spaces. These changes correlate with a decline in the overall spatial coupling coordination and an intensification of spatial differentiation patterns.

- (2)

- Spatial evolution appears to be influenced by a combination of internal and external factors. Internal drivers are linked to villagers’ demand for improved living quality, while external drivers include transformative forces such as tourism market development and policy guidance.

- (3)

- Elements of new-quality productive forces show notable statistical association with spatial coordination. Among these, technological innovation level exhibits a strengthening correlation, whereas the contribution from hardware proliferation has shown fluctuation, suggesting the importance of synergistic “technology-institution-application” support in the diffusion process.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Primary Category | Secondary Category | Production Function /Points | Living Function /Points | Ecological Function /Points | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category Code | Category Name | Category Code | Category Name | |||

| 1 | Arable Land | 11 | Paddy Fields | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| 13 | Dryland | 3 | 0 | 3 | ||

| 2 | Garden Plot | 21 | Orchard | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| 3 | Woodland | 31 | Forested land | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| 4 | Grassland | 43 | Other Grass | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| 5 | Commercial and service land | 51 | Wholesale and Retail Land | 5 | 1 | 0 |

| 52 | Accommodation and Food Service Land | 5 | 1 | 0 | ||

| 54 | Other Commercial Land | 5 | 1 | 0 | ||

| 6 | Industrial, Mining, and Storage Land | 61 | Industrial Land | 5 | 1 | 0 |

| 63 | Warehouse Land | 5 | 1 | 0 | ||

| 7 | Residential Land | 72 | Rural Homestead Land | 3 | 5 | 0 |

| 8 | Public Administration and Public Service Land | 81 | Land for Government Agencies and Organizations | 3 | 3 | 0 |

| 83 | Educational and Scientific Land | 3 | 3 | 0 | ||

| 84 | Medical and Health Charitable Land | 3 | 3 | 0 | ||

| 85 | Cultural, Sports, and Entertainment Land | 3 | 3 | 0 | ||

| 86 | Public Facility Land | 3 | 3 | 0 | ||

| 87 | Parks and Green Spaces | 1 | 3 | 1 | ||

| 88 | Scenic and Historic Site Facilities | 3 | 3 | 0 | ||

| 9 | Special Land Use | 94 | Religious Land | 3 | 3 | 0 |

| 95 | Cemetery Land | 3 | 3 | 0 | ||

| 10 | Transportation Land | 102 | Highway Land | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| 103 | Street and Alley Roads | 5 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 104 | Rural roads | 5 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 11 | Water Areas and Water Conservancy Facilities Land | 111 | River Water Surface | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| 114 | Pond water surface | 1 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 112 | Lake surface | 0 | 0 | 5 | ||

| 117 | Ditch | 1 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 12 | Other Land | 121 | Vacant land | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| 122 | Facility Agricultural Land | 1 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 123 | Field Ridges | 3 | 0 | 3 | ||

| Functions of PLE Spaces | Indicator Layer | Symbol | Calculation Method or Data Source | Attribute | Weight |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Production | Level of technological innovation | X3 | Internal expenditure on research and experimental development (R&D) × (Total output value of agriculture, forestry, animal husbandry, and fishery/Regional GDP) | + | 0.0732 |

| Labor productivity | X5 | Primary industry value added/Primary industry employment | + | 0.0443 | |

| Agricultural Output Value per Capita | X7 | Total Output Value of Agriculture, Forestry, Animal Husbandry, and Fisheries/Rural Population | + | 0.0733 | |

| Land output efficiency | X8 | Total agricultural output value/Total crop planted area | + | 0.0743 | |

| Grain Yield per Unit Area | X9 | Total Grain Output/Grain Sown Area | + | 0.0930 | |

| Agricultural electricity efficiency | X10 | Rural electricity consumption/Total output value of agriculture, forestry, animal husbandry, and fisheries | + | 0.0560 | |

| Living | Average Number of Computers Owned per 100 Rural Households at Year-End | X1 | Total number of computers owned/Total number of households | + | 0.0572 |

| Average number of mobile phones owned per 100 rural households at year-end | X2 | Total mobile phones/total households | + | 0.1052 | |

| Average Years of Education for Rural Population | X4 | (Number of illiterate individuals × 1 + Number of primary school graduates × 6 + Number of junior high school graduates × 9 + Number of senior high school graduates × 12 + Number of college graduates and above × 16)/Total population aged 6 and above | + | 0.0956 | |

| Per capita disposable income of rural residents | X6 | Total Rural Residents’ Disposable Income/Rural Permanent Population | + | 0.0474 | |

| Ecological | Pesticide Use per Unit Area | X11 | Total Pesticide Use (Converted to Pure Pesticide Equivalent)/Total Cultivated Land Area | − | 0.0420 |

| Forest coverage rate | X12 | Forest area/Total land area | + | 0.1722 | |

| Share of fiscal expenditure on agriculture, forestry, and water affairs | X13 | Local fiscal expenditure on agriculture, forestry, and water affairs/Local fiscal general budget expenditure | + | 0.0663 |

References

- Propaganda Department of the CPC Guangdong Provincial Committee. Vigorously Inherit and Promote Lingnan Culture. Available online: https://www.qstheory.cn/20250830/06e58e1c15a34ba9a54b2e45db8a9fa8/c.html (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Feng, J. The Dilemma and Path Forward for Traditional Villages—With a Discussion on Traditional Villages as Another Category of Cultural Heritage. Folk Cult. Forum 2013, 1, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, W.; Xiao, S.; Li, Q. AHP–Entropy Method for Sustainable Development Potential Evaluation and Rural Revitalization: Evidence from 80 Traditional Villages in Cantonese Cultural Region, China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Xu, E.; Zhu, H. An ecological-living-industrial land classification system and its spatial distribution in China. Resour. Sci. 2015, 37, 1332–1338. Available online: https://d.wanfangdata.com.cn/periodical/CiBQZXJpb2RpY2FsQ0hJU29scjkyMDI1MTIyNDE1NDU1NRINenlreDIwMTUwNzAwNBoIeWR1eXYzN2w%3D (accessed on 10 December 2025). (In Chinese)

- Joint Research Team of the Publicity Department of the CPC Guangdong Provincial Committee and the Comprehensive Editorial Department of Qiushi Journal. “The Hundred-Thousand-Ten-Thousand Project”: Addressing Imbalances in Urban-Rural and Regional Development. Available online: https://www.qstheory.cn/20251129/9e2074be853d49bb8cd6e5ed54670cdc/c.html (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Sun, P.; Zhou, L.; Ge, D.; Lu, X.; Sun, D.; Lu, M.; Qiao, W. How does spatial governance drive rural development in China’s farming areas? Habitat Int. 2021, 109, 102320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, D.; Qiao, J.; Zhu, Q. Rural-spatial restructuring promoted by land-use transitions: A case study of Zhulin Town in central China. Land 2021, 10, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Fang, C. Quantitative function identification and analysis of urban ecological-production-living spaces. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2016, 71, 49–65. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y. Classification evaluation and spatial-temporal analysis of “production living-ecological” spaces in China. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2017, 72, 1290–1304. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, A.; Xu, Y.; Lu, L.; Liu, C.; Zhang, Y.; Hao, J.; Wang, H. Research progress of the identification and optimization of production-living-ecological spaces. Adv. Geogr. Sci. 2020, 39, 503–518. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, K.S.; Nguyen, T.D.; Francois, J.R.; Ojha, S. Rural sustainability methods, drivers, and outcomes: A systematic review. Sustain. Dev. 2023, 31, 1226–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Tang, N. Spatio-temporal characteristics and evolution of rural production-living-ecological space function coupling coordination in Chongqing Municipality. Geogr. Res. 2018, 37, 1100–1114. Available online: https://d.wanfangdata.com.cn/periodical/CiBQZXJpb2RpY2FsQ0hJU29scjkyMDI1MTIyNDE1NDU1NRINZGx5ajIwMTgwNjAwNBoIcHo3YWg4dDI%3D (accessed on 12 December 2025). (In Chinese)

- Cui, J.; Gu, J.; Sun, J.; Luo, J. The Spatial Pattern and Evolution Characteristics of the Production, Living and Ecological Space in Hubei Provence. Chin. J. Land Sci. 2018, 32, 67–73. Available online: https://d.wanfangdata.com.cn/periodical/CiBQZXJpb2RpY2FsQ0hJU29scjkyMDI1MTIyNDE1NDU1NRITemhvbmdndGRreDIwMTgwODAxMBoIY21oMzh1YnY%3D (accessed on 12 December 2025). (In Chinese)

- Dong, Z.; Zhang, J.; Si, A.; Tong, Z.; Na, L. Multidimensional analysis of the spatiotemporal variations in ecological, production and living spaces of Inner Mongolia and an identification of driving forces. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gai, Z.; Chen, X.; Du, G.; Wang, H. Analysis on Eco-environmental Effects and Driving Factors of Ecological-production-living Spatial Evolution in Harbin Section of Songhua River Basin. J. Soil Water Conserv. 2022, 36, 116–123. Available online: https://d.wanfangdata.com.cn/periodical/CiBQZXJpb2RpY2FsQ0hJU29scjkyMDI1MTIyNDE1NDU1NRIUdHJxc3lzdGJjeGIyMDIyMDEwMTcaCGZ3dG90aTVh (accessed on 25 December 2025). (In Chinese)

- Zhu, Y.; Yu, B.; Zeng, J.; Han, Y. Spatial Optimization from Three Spaces of Production, Living and Ecologyin National Restricted Zones—A Case Study of Wufeng County in Hubei Province. Econ. Geogr. 2015, 35, 26–32. Available online: https://d.wanfangdata.com.cn/periodical/https://d.wanfangdata.com.cn/periodical/CiBQZXJpb2RpY2FsQ0hJU29scjkyMDI1MTIyNDE1NDU1NRINampkbDIwMTUwNDAwNBoIbXpycDl6dWs%3D (accessed on 15 December 2025). (In Chinese)

- Wu, L.; Yu, K.; Yu, X.; Jing, W. Research on the Revitalization Path of Production-Living-Ecologial Space of Typical Villages in Qin-Ba Mountainous Area:A Case Study of Rural Revitalization Planning of Huayuan Village in Shangluo City. Planners 2019, 35, 45–51. Available online: https://d.wanfangdata.com.cn/periodical/CiBQZXJpb2RpY2FsQ0hJU29scjkyMDI1MTIyNDE1NDU1NRIMZ2hzMjAxOTIxMDA3Ggh0N2o2emZwcw%253D%253D (accessed on 15 December 2025). (In Chinese)

- Nong, X.; Wu, B.; Chen, T.; Cheng, L. Evaluation of national land use and space for functions of “Production, Life, Ecology”. Planners 2020, 6, 26–32. Available online: https://d.wanfangdata.com.cn/periodical/ghs202006004 (accessed on 15 December 2025). (In Chinese)

- Ma, S.; Huang, H.; Cai, Y.; Nian, P. Theoretical Framework with Regard to Comprehensive Sub-Areas of China’s Land Spaces Based on the Functional Optimization of Production, Life and Ecology. China Land Resour. Econ. 2014, 27, 31–34. Available online: https://d.wanfangdata.com.cn/periodical/CiBQZXJpb2RpY2FsQ0hJU29scjkyMDI1MTIyNDE1NDU1NRIRemdkemtjamoyMDE0MTEwMDgaCG5kcWpobHVn (accessed on 15 December 2025). (In Chinese)

- Su, X.; Zhou, H.; Guo, Y.; Zhu, Y. Multi-Dimensional Influencing Factors of Spatial Evolution of Traditional Villages in Guizhou Province of China and Their Conservation Significance. Buildings 2024, 14, 3088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Zhao, Y.; Li, X.; Wei, Z.; Xia, S. Characteristics and Optimization of Geographical Space in Urban Agglomeration in the Upper Reaches of the Yangtze River Based on the Function of “Production-Living-Ecological”. Resour. Environ. Yangtze River Basin 2019, 28, 1070–1079. Available online: https://d.wanfangdata.com.cn/periodical/CiBQZXJpb2RpY2FsQ0hJU29scjkyMDI1MTIyNDE1NDU1NRISY2pseXp5eWhqMjAxOTA1MDA3GghzcmNqY29zdQ%3D%3D (accessed on 15 December 2025). (In Chinese)

- Liu, D.Q.; Ma, X.C.; Gong, J.; Li, H.Y. Functional identification and spatiotemporal pattern analysis of production living ecological space in watershed scale: A case study of Bailongjiang Watershed in Gansu. Chin. J. Ecol. 2018, 37, 1490. Available online: https://d.wanfangdata.com.cn/periodical/CiBQZXJpb2RpY2FsQ0hJU29scjkyMDI1MTIyNDE1NDU1NRIOc3R4enoyMDE4MDUwMjcaCGFmaWtvaXJ1 (accessed on 15 December 2025). (In Chinese)

- Zhang, Z.; Hou, Y.; Sun, H.; Guo, S. Study on the evaluation of the spatial function and coordination relationship of the territorial “production-living-ecological” spaces at the township-street scale. Acta Nat.-Resour. Sci. China 2022, 37, 2898–2914. Available online: https://webvpn.neu.edu.cn/https/62304135386136393339346365373340bbefb77189cb4dd4bc166e67/kcms2/article/abstract?v=yqBhao7Q9gw4KtYox427Mu6zEO_fIW54XmtYSjRByYSSZmEP5U8rrGsCz-nHmBiMT5ynh3iQ0ZkHTT31YMp_CQXZWiVdCGRYNxUCJqZk0HWe9StzTK6Ak9R4ZX638QVgw1aA5sr8sNQyV0 (accessed on 1 December 2025). (In Chinese) [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Zeng, C.; Dou, Y.; Liu, P.; Chen, C. Change of human settlement environment and driving mechanism in traditional villages based on living-production-ecological space: A case study of Lanxi Village, Jiangyong County, Hunan Province. Adv. Geogr. Sci. 2018, 37, 677–687. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, Q. Analysis of Temporal and Spatial Evolution Characteristics of Coupling Coordination of Cultivated Land “Production-living-ecological” Space in Upper Reaches of Yellow River—A Case Study of Gansu Province. J. Agric. Sci. Technol. 2025, 27, 205–215. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Yigitcanlar, T.; Li, F.; Deng, S.; Yang, Y. Sustainable Development of Production–Living–Ecological Spaces: Insights from a 30-Year Remote Sensing Analysis. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.F.; Xu, C.D. Geodetector: Principle and prospective. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2017, 72, 116–134. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=SQKXI91EiTpqAPidv-BJRJ7isdWUFcv47tvmc3rJMTdTqKt5ZXpR1sQSI1c9sFigjclUn7-SG0e_uWD84bO0hE7hbr5xM3Y-8aesgaOU6jWRO2Sgo-bqRCAu0bHHOR2CRmzEpvUcva-7anOO9hhFcCLyvbYoveffFCRdGOMMRtE=&uniplatform=NZKPT (accessed on 10 November 2025). (In Chinese)

- Liu, Z. Three Spaces and Three Lines Delimitation in the Context of New Spatial Plan System. Planners 2019, 35, 27–31. Available online: https://d.wanfangdata.com.cn/periodical/CiBQZXJpb2RpY2FsQ0hJU29scjkyMDI1MTIyNDE1NDU1NRIMZ2hzMjAxOTA1MDA0GghzaWpicjIyaw%253D%253D (accessed on 10 November 2025). (In Chinese)

- Pathak, V.; Deshkar, S. Transitions towards sustainable and resilient rural areas in revitalising India: A framework for localising SDGs at Gram panchayat level. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opinions of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China and the State Council on Implementing the Rural Revitalization Strategy. People’s Daily, 5 February 2018. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=SQKXI91EiTqWEF5ZYI7exY6_TXeYYi0UMO-5oCs-mP3BWRqgggl__Vw5p96Zx3bVyXG2KCp2Zfsqo6rKC71o-0ZyDfr3VwIjyNQZjro68jRBUvJR_oJ3cpvhyB1XQ-ou7P6ojmoVv9KnPP3HBkphpoKI0pnDECBwL33uUTQt1IXIHIzzMkR30A==&uniplatform=NZKPT (accessed on 1 November 2025). (In Chinese)

- Slee, B. Collaborative Action, Policy Support and Rural Sustainability Transitions in Advanced Western Economies: The Case of Scotland. Sustainability 2024, 16, 870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Developing New Quality Productivity Based on Local Conditions. People’s Daily, 6 March 2024; (In Chinese). [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, H.; Sun, R. Measurement and Spatio-temporal Pattern of the New Quality Productive Forces at the Municipal Level in China. Econ. Geogr. 2025, 45, 67–78. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.; Jian, J.; Yu, H.; Zeng, Y.; Lin, M. Research on the spatial pattern and influence mechanism of industrial transformation and development of traditional villages. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, J.; Xie, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhong, T.; Lin, Y.; Wang, M. The Transformation of Peri-Urban Agriculture and Its Implications for Urban–Rural Integration Under the Influence of Digital Technology. Land 2025, 14, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, B. The Logic of Productive Forces Modernization Transforming into New Quality Productive Forces. Econ. Res. J. 2024, 59, 12–19. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=SQKXI91EiTqTjHY9lcNBna2DhLXACU-NMGrX7AUMbOvRsPolMk2gMsamPZrzfYfA7L4E4cRKjV5VtBK_Nf2w6jpxMxsvIR2epa--Hk9VQgghr_Khsv-s0t5q6ea_WI4ltwEHPWSRq4X2_11vz99yV0IIw-FXqZxoUU5Q_zItvps=&uniplatform=NZKPT (accessed on 20 November 2025). (In Chinese)

- Qi, M.; Yin, J.; Pan, W. New Quality Productive Forces Empowers Rural Revitalization: Value Implication, Coupling Mechanism and Practical Path. Anhui Agric. Sci. 2025, 1–5. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=SQKXI91EiTosOD7sigckyBifk2Vq2HNtvOlRrmfnEsn1k0pOjDlB82Td0V8uduny_1WmC10RvcZeUuv4T2ETRWBSqqBBycAgckH9PfnXsLAKYTOvR5lvEDM2tFoSo9smmEBk8LN3BPbzOgN9zPzIE4YzwxPOx0WvEawtGYs1CUY=&uniplatform=NZKPT (accessed on 10 November 2025). (In Chinese)

- Zhang, R.; Zhang, X. Empowering the Spatial Construction of Rural Communities through New Quality Productive Forces: Lnternal Mechanisms, Realistic Reflections, and Developmental Pathways. Seek. Truth 2025, 3, 95–108+12. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=SQKXI91EiToJxzdQICjx5FLfiPAZOArPPLcm422B-Ei2F2peqp09SAao1dcRof6qaUTCpj01izNm5HqSilEfgVCTsDsizhPUOQXPKpYtR0UfhKPoO_wMso9RhnyRPhgZMOd6ORzc6p1BNvizOkMSUqWiyij0TG5XazCY8lSOtck=&uniplatform=NZKPT (accessed on 10 November 2025). (In Chinese)

- Zhang, J.; Wu, Y.; Zhu, Y. Spatial correlation network and its driving mechanism of collaborative agglomeration between manufacturing and producer services in China. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2025, 80, 396–414. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=SQKXI91EiTqkWCeU7XZ6TduCoyuht1Jhod0WSB-FRn6fkFfhXAbcaZvOgLDEUe0mODHjs63COdIxiQamgUewlu2Ar0mh-jpcm85ExHues1IihjBiuwHxKYDj07QHWMJRt4U-LvCsXQ7AEFeqkp_rxL3aZW3b7WDtTIZWrq-eVsU=&uniplatform=NZKPT (accessed on 16 November 2025). (In Chinese)

- Luo, B. On the New Quality Productivity Forces in Agriculture. Reform 2024, 4, 19–30. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=SQKXI91EiTq6bOj6N1GH7UGUAk0gCdlBBh-XQSoPfBPIY7rVnlQdwwJnPwOerrzH0bAMd2vr_qjPhza_rRbt7FgyH0EneuOvbzUFMSJHk5ZI9uYZyyblc8aj6aMh-NzG6kAtppT0LhJWvrR8FXa87QLKlVswf6N_Fb2U357ivnQ=&uniplatform=NZKPT (accessed on 21 November 2025). (In Chinese)

- Jiang, Y.; Du, C. New-Quality Agricultural Productive Force Boosts the Realization of the Value of Rural Ecological Products. Rural Econ. 2024, 6, 1–10. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, G.; Zhang, C. Empowering Comprehensive Rural Revitalization with New Quality Productive Forces. J. Technol. Econ. Manag. 2024, 6, 9–14. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=SQKXI91EiTpW68AWdZYk4_-UprhE4Pm6KmYq9hC_YizqbGHIVSCrl88XNSud6Z-kGinj5ApurnxSo5yQUtmq_zo5Jov5lZgb4api-FbwbViZF3DUwstoCv4HaDbLYbaJxOPBxFuERrGe5zrkKtmUz8Kt7K0GCbtQ0Q6-UieYntA=&uniplatform=NZKPT (accessed on 12 November 2025). (In Chinese)

- Wu, C. On the Core Research Focus of Geography: Human-Land Relationship Regional Systems. Econ. Geogr. 1991, 3, 1–6. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Duan, X.; Wang, L.; Jin, Z. Land Use Transformation Based on Ecological-production-living Spaces and Associated Eco-environment Effects: A Case Study in the Yangtze River Delta. Sci. Geogr. Sin. 2018, 38, 97–106. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yao, S.; Yan, F.; Chen, L.; Qi, Y. Improved Cellular Automata-Markov model-based simulation and prediction on evolution of land use pattern: A case of Xinyu City. Water Resour. Hydropower Eng. 2022, 53, 71–83. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Liu, Z.; Li, C.; Cha, L.; Song, Z.; Zhang, X. Land use function transformation in the Xiong’an New Area based on ecological-production-living spaces and associated eco-environment effects. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2020, 40, 7113–7122. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=SQKXI91EiTod_-GN-qMqRELt59yRY8uzYSbnjB7-D-BFov0bozQgBGgFf7sHPWYkewo6Xt1MiviW84ze0e6sWpocl2bgKkDGxiSUVbWfOU46lexMP-MfF4Q1iX50xu4CNQcGuwqpQq51RwFX4k9242rnq-czzDPq6oIWNOyrawc=&uniplatform=NZKPT (accessed on 10 November 2025). (In Chinese)

- Zhao, T.; Cheng, Y.; Fan, Y.; Fan, X. Functional Tradeoffs and Feature Recognition of Rural Production–Living–Ecological Spaces. Land 2022, 11, 1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T21010-2017; Current land Use Classification. General Administration Of Quality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine of the People’s Republic of China and National Technical Committee on Standardization of Land and Resources: Beijing, China, 2017.

- Lü, D.; Gao, G.; Lü, Y.; Xiao, F.; Fu, B. Detailed land use transition quantification matters for smart land management in drylands: An in-depth analysis in Northwest China. Land Use Policy 2020, 90, 104356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Lu, X.; Guo, Q.; Zhang, Y. Spatiotemporal Measurement of Coordinated Resource-Environment-Economy Development Based on Empirical Analysis from China’s 30 Provinces. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, S.; Li, S.; Feng, K. Coupling analysis of urbanization and energy-environment efficiency: Evidence from Guangdong province. Applied Energy 2019, 254, 113650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Shi, Y.; Zhu, X. Investigation of a coupling model of coordination between urbanization and the environment. J. Environ. Manag. 2012, 98, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.-N.; Nguyen, V.T.; Duong, D.H.; Thai, H.T.N. A Hybrid Fuzzy Analysis Network Process (FANP) and the Technique for Order of Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution (TOPSIS) Approaches for Solid Waste to Energy Plant Location Selection in Vietnam. Applied Sciences 2018, 8, 1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Zhang, X.; Teng, L.; Ma, W.; Tan, L.; Li, H. Distribution Characteristics and Influencing Factors of Traditional Villages in the Lingnan Region of China. Buildings 2025, 15, 978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, M.; Wang, K. Evaluation index system and empirical analysis of rural revitalization level. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2020, 36, 236–243. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=SQKXI91EiTpFCLipr5CjixuFVHjB4K1clQP3sfd95CW-jb6g61ZVFRkbgfxt1Dr21hfb7Yq4oaN0OWJmZuFwm3ivHDprxUYaWgnpqqeP1zrIZhxDTGlPfyaa6jaXwy16amxtBrP9ouQJSPzrWWOfuXELq_oeJ720Cwbl9yKPyUw=&uniplatform=NZKPT (accessed on 26 November 2025). (In Chinese)

- Traditional Village Network. Available online: http://www.chuantongcunluo.com/index.php/Home/Gjml/gjml/id/24.html (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Loc, H.H.; Park, E.; Thu, T.N.; Diep, N.T.H.; Can, N.T. An enhanced analytical framework of participatory GIS for ecosystem services assessment applied to a Ramsar wetland site in the Vietnam Mekong Delta. Ecosyst. Serv. 2021, 48, 101245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Jiang, G.; Li, W.; Zhou, T. Multifunctionality assessment of the land use system in rural residential areas: Confronting land use supply with rural sustainability demand. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 231, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Jia, L.; Wu, W.; Yan, J.; Liu, Y. Urbanization for rural sustainability–Rethinking China’s urbanization strategy. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 178, 580–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, L.; An, Z. Digital transformation in agricultural circulation: Enhancing rural modernization and sustainability through technological innovation. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2025, 9, 1538024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Shan, Y.; Xia, S.; Cao, J. Traditional village morphological characteristics and driving mechanism from a rural sustainability perspective: Evidence from Jiangsu Province. Buildings 2024, 14, 1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, P.; Ge, D.; Yuan, Z.; Lu, Y. Rural revitalization mechanism based on spatial governance in China: A perspective on development rights. Habitat Int. 2024, 147, 103068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Land Type | 1993 | 2003 | 2013 | 2023 | Net Gain/Loss /% | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Area/ (km2) | Percent/% | Area/ (km2) | Percent/% | Area/ (km2) | Percent/% | Area/ (km2) | Percent/% | ||

| Arable Land | 123.2478 | 63.04 | 104.3802 | 53.3 | 91.3977 | 46.74 | 106.668 | 54.57 | −8.47 |

| Forest land | 28.5993 | 14.64 | 24.4314 | 12.50 | 26.7156 | 13.66 | 23.4387 | 12 | −2.64 |

| Grassland | 0.1116 | 0.02 | 0.1116 | 0.02 | 0.1881 | 0.03 | 0.0774 | 0.02 | 0 |

| Water area | 32.1264 | 16.43 | 42.9498 | 21.97 | 39.3255 | 20.21 | 19.0215 | 9.76 | −6.67 |

| Unutilized land | 0.0018 | 0.01 | 0.0135 | 0.01 | 0.1044 | 0.02 | 0.1728 | 0.03 | +0.02 |

| Construction Land | 11.4615 | 5.86 | 23.6619 | 12.2 | 37.8171 | 19.34 | 46.17 | 23.62 | +17.76 |

| Year | Low-Level Coupling 0–0.3 | Antagonistic Stage 0.3–0.5 | Break-in Stage 0.5–0.8 | High-Level Coupling 0.8–1.0 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1993 | 13.5 | 3.9 | 14.5 | 68.1 |

| 2003 | 15.3 | 4.2 | 15.7 | 64.8 |

| 2013 | 21.2 | 4.7 | 17.2 | 56.9 |

| 2023 | 24.2 | 4.8 | 17.8 | 53.2 |

| Year | Mean | Standard Deviation | Proportion of Coupling Coordination Degree (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Severe Imbalance | Moderate Imbalance | Basic Coordination | Moderate Coordination | Highly Coordinated | |||

| 1993 | 0.6680 | 0.2806 | 12.5 | 2.0 | 11.2 | 29.5 | 44.8 |

| 2003 | 0.6413 | 0.2879 | 14.2 | 2.1 | 11.6 | 35.5 | 39.6 |

| 2013 | 0.6318 | 0.3352 | 19.7 | 2.0 | 7.1 | 23.2 | 48.0 |

| 2023 | 0.6053 | 0.3498 | 22.9 | 1.9 | 6.8 | 22.9 | 45.5 |

| Driving Factor | 1993 | 2003 | 2013 | 2023 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| q | p | q | p | q | p | q | p | |

| Computer Ownership Among Rural Residents (X1) | 0.198 | 0.062 | 0.287 | 0.018 * | 0.352 | 0.008 * | 0.312 | 0.016 * |

| Mobile phone ownership among rural residents (X2) | 0.287 | 0.025 * | 0.412 | 0.002 * | 0.498 | 0.000 * | 0.385 | 0.007 * |

| Level of Technological Innovation (X3) | 0.423 | 0.005 * | 0.487 | 0.001 * | 0.532 | 0.000 * | 0.603 | 0.000 * |

| Average Years of Education for Rural Population (X4) | 0.498 | 0.002 * | 0.521 | 0.000 * | 0.503 | 0.000 * | 0.562 | 0.000 * |

| Labor Productivity (X5) | 0.587 | 0.000 * | 0.648 | 0.000 * | 0.632 | 0.000 * | 0.703 | 0.000 * |

| Per capita disposable income of rural residents (X6) | 0.623 | 0.000 * | 0.702 | 0.000 * | 0.685 | 0.000 * | 0.721 | 0.000 * |

| Agricultural Output Per Capita (X7) | 0.518 | 0.001 * | 0.563 | 0.000 * | 0.538 | 0.000 * | 0.487 | 0.002 * |

| Land Output Efficiency (X8) | 0.532 | 0.001 * | 0.601 | 0.000 * | 0.623 | 0.000 * | 0.659 | 0.000 * |

| Grain yield per unit area (X9) | 0.352 | 0.012 * | 0.378 | 0.006 * | 0.402 | 0.003 * | 0.432 | 0.001 * |

| Agricultural Electricity Efficiency (X10) | 0.265 | 0.031 * | 0.243 | 0.038 * | 0.218 | 0.057 | 0.203 | 0.072 |

| Pesticide Application Rate per Unit Area (X11) | 0.187 | 0.071 | 0.203 | 0.054 | 0.231 | 0.041 * | 0.265 | 0.028 * |

| Forest Cover Rate (X12) | 0.385 | 0.008 * | 0.412 | 0.003 * | 0.431 | 0.002 * | 0.523 | 0.000 * |

| Share of Fiscal Expenditures on Agriculture, Forestry, and Water Affairs (X13) | 0.328 | 0.017 * | 0.352 | 0.009 * | 0.312 | 0.015 * | 0.287 | 0.021 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Mo, W.; Bao, J.; Li, Q. Spatiotemporal Evolution and Driving Mechanisms of Production–Living–Ecological Space Coupling Coordination in Foshan’s Traditional Villages: A Perspective of New Quality Productive Forces. Sustainability 2026, 18, 1494. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18031494

Mo W, Bao J, Li Q. Spatiotemporal Evolution and Driving Mechanisms of Production–Living–Ecological Space Coupling Coordination in Foshan’s Traditional Villages: A Perspective of New Quality Productive Forces. Sustainability. 2026; 18(3):1494. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18031494

Chicago/Turabian StyleMo, Wei, Jie Bao, and Qi Li. 2026. "Spatiotemporal Evolution and Driving Mechanisms of Production–Living–Ecological Space Coupling Coordination in Foshan’s Traditional Villages: A Perspective of New Quality Productive Forces" Sustainability 18, no. 3: 1494. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18031494

APA StyleMo, W., Bao, J., & Li, Q. (2026). Spatiotemporal Evolution and Driving Mechanisms of Production–Living–Ecological Space Coupling Coordination in Foshan’s Traditional Villages: A Perspective of New Quality Productive Forces. Sustainability, 18(3), 1494. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18031494