1. Introduction

Sustainability has become a central concern for higher education institutions (HEIs), as universities are increasingly expected to contribute not only to knowledge generation but also to sustainable social transformation. Beyond their traditional roles in teaching and research, HEIs are now recognized as strategic actors in advancing sustainable development through extension and social outreach activities that generate measurable impacts on society, the economy, public governance, and the natural environment.

Within this sustainability agenda, social innovation has emerged as a critical mechanism for addressing complex societal challenges that cannot be solved through conventional approaches. Recent literature highlights that social innovation oriented toward sustainability enables inclusive and resilient solutions with lasting effects by fostering collaboration among multiple stakeholders and aligning institutional actions with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). In this regard, universities play a pivotal role as integrators of knowledge, territorial actors, and catalysts of sustainable change [

1].

The Quintuple Helix (QH) model provides a comprehensive sustainability framework for analyzing these dynamics, as it explicitly incorporates the natural environment alongside academia, industry, government, and civil society. By integrating environmental considerations into innovation processes, the QH model aligns social innovation with sustainability outcomes, making it particularly suitable for evaluating the impact of university extension projects. However, despite its conceptual relevance, empirically validated instruments capable of measuring social innovation impacts linked to sustainability within higher education institutions (HEIs) remain limited.

Currently, university extension has gained increasing relevance and is recognized as one of the three core functions of higher education, alongside teaching and research. In Colombia, its importance is particularly evident, as both the Ministry of National Education (MEN) and the National Accreditation Council (CNA) require the execution of social outreach activities for program approval and quality accreditation, including projects that generate impact on external sectors. However, this requirement goes beyond regulatory compliance: it reflects the essential and mission driven role of academia in fostering social innovation. Since their origins, universities have been key agents of social innovation, and their participation has evolved within the helix-based innovation models: from the triple helix (university–industry–government), to the quadruple helix (which incorporates society), and ultimately to the quintuple helix, which also integrates the natural environment. In this context, it becomes essential to reflect on the influence of this model on social innovation processes driven by university extension and social outreach, particularly through the variable “impact”, within “the new paradigm known as Society 5.0, where human beings are at the center of innovation [

2].” This perspective is particularly valuable because Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) participate in extension dynamics shaped by their institutional mission, educational projects, social needs, public policies, and development plans. They also contribute actively to the Sustainable Development Goals, especially SDG 4 (Quality Education), SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities), and SDG 17 (Partnerships for the Goals).

Added to this are the lessons learned after the COVID-19 pandemic, population aging, and climate change, which have reshaped the way projects and activities are carried out. As Cabrera notes, “the actions implemented in an improvised manner have allowed extension activities to continue developing through alternative pathways, without the need for habitual face to face contact with the community [

3].” It is precisely in this context that social innovation has emerged over the past decade as a key approach to addressing complex socioeconomic and environmental challenges that traditional strategies have failed to solve. Numerous studies have demonstrated that social innovations contribute to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals by promoting inclusive, sustainable, and resilient solutions capable of generating long term systemic change [

4,

5,

6,

7]. These initiatives rely on collaborative processes integrating multiple disciplines, including economics, sociology, environmental sciences, and technology, allowing for a more holistic understanding of social problems and the design of effective solutions [

8]. In some cases, they go beyond interdisciplinarity and give rise to more enduring social innovations through transdisciplinarity [

9,

10], which is essential for addressing complex sustainability challenges but requires deep disciplinary integration, cocreation, ethical and political management of tensions among stakeholders [

11].

From this perspective of social commitment, the concept of University Social Responsibility (USR) gains strength. Universities “were conceived as promoters of development and social wellbeing and, in relation to the concept of social responsibility, should participate primarily in extension, research, management, and social outreach activities, with their essential role being the professional training of individuals, as well as other functions that strengthen this mission [

12,

13,

14,

15].” This is closely linked to the variable “impact”, understood as “the transformations generated by the components of extension policy through university projects in individuals, collectives, organizations, and regions; thus, this variable includes subcomponents such as peace, equity, regional development, Sustainable Development Goals, and sustainability” [

16].

Within this context, universities are called to play a strategic role in promoting social innovation, not only as producers of knowledge but also as active agents in the trans-formation of their territories and their sustainability. Several authors highlight that integrating social innovation into the university’s core functions: teaching, research, and extension (also referred to as social outreach) strengthens the connection with society, fosters innovation ecosystems, and contributes to building more sustainable and inclusive communities [

17]. It is here that the first substantive function (teaching) becomes evident through service learning as a mechanism for social integration [

18], the curricular and pedagogical dimension as components of the university social responsibility model [

19], and, of course, through the SDGs, particularly in relation to education with a social and sustainable focus [

20,

21]. Regarding the link between university research and social innovation, research serves as the collaborative axis of the substantive functions, from which social problems are identified and addressed [

22,

23]. This requires interdisciplinarity [

8] and transdisciplinarity [

9] to strengthen and create social innovation ecosystems [

24,

25].

To complete the substantive functions, extension, also referred to as social outreach or engagement with the environment, acts as the articulating bridge between the other university functions and civil society, the natural environment, the business sector, and the state. Within this framework, higher education institutions are understood as agents of social development [

26], capable of fostering community engagement and cocreation between academia and society [

27,

28] and enabling extension activities to function as processes of social innovation [

29,

30].

Given that this study is framed within university extension projects, it is essential to recognize that “social innovation has become vital for addressing societal problems and strengthening community wellbeing. Universities play a key role in fostering social innovation through collaborative partnerships with communities, which in turn offer valuable insights into local challenges [

31]”. Furthermore, “universities have traditionally been regarded as key actors in regional innovation systems and in innovation driven regional development [

32]”.

For Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) to generate social innovation, it is crucial to consider their three substantive functions: teaching, research, and extension or social outreach. While some universities place greater emphasis on one of these functions, they all contribute according to their institutional strengths. Regarding extension, terms such as “civic universities” [

32] or “Community–University Engagement (CUE)” [

33] are often used. In the educational domain, the concept of “educational innovation” stands out [

34], while in research, recurring terms include “innovation,” “technology,” and “development” [

35].

It has also been demonstrated that university productivity increases when the substantive functions are interconnected, particularly in collaborative projects between universities, government, and industry [

36]. The literature additionally includes concepts related to social innovation such as sustainability, development, and social responsibility [

37,

38,

39,

40]. Nonetheless, it is also recognized that the success of HEIs in these areas depends on external factors, as “Higher Education Institutions are being called upon to integrate sustainable development within their organizations, driven by national and international events, policies, and environmental goals [

32].”

Several studies indicate that regulatory frameworks and public policies directly affect the conditions for generating social innovation: “the results show that collaborations that lead the development of relationships among universities, industry, and government and their scope change in response to regulatory reforms [

41].” This requires academic leaders and policymakers to “derive guidelines that strengthen the university system and promote the design of policies that facilitate the adoption of Education for Sustainable Development by HEIs [

39].” In projects coordinated between government and universities, four key success factors have been identified: “outcomes, institutional capacities, quality of relationships, and adequate regulatory frameworks [

42].” Furthermore, aligning extension projects with the SDGs [

43] is emphasized as evidence of social innovation and as a foundation for strengthening the action of the actors in the Quintuple Helix.

In addition, there is a growing research trend toward models and systems supported by the Quintuple Helix, because it facilitates the agile exchange of knowledge and re-sources essential for addressing challenges and represents a strategic imperative for promoting coordinated actions aimed at eco-efficiency and eco-effectiveness [

44].” The validity of this model has also been highlighted “for its capacity to represent a complex and articulated community of actors, as well as for demonstrating its scalability through dynamic and forward-looking approaches [

45].” Other researchers propose it as an analytical framework in which multiple actors exchange knowledge to foster eco-innovations oriented toward the circular economy and climate change mitigation [

46], and models such as the “Eco-Quintuple Helix Model (eco-5HM)” have been developed to guide strategies and decisions toward sustainability [

47].

The evolution of the social innovation model through helix frameworks reflects a transition from the traditional university, industry and government approach [

48] to the incorporation of civil society [

49], and ultimately to the integration of the natural environment [

50].

The Triple Helix model presented by Etzkowitz [

48] interprets innovation as a collaborative dynamic among universities, industry, and government, moving beyond linear knowledge transfer and toward reciprocal interaction. In this framework, universities adopt an entrepreneurial role linked to regional development, industry contributes not only capital but also research capabilities, and government acts as an enabler through regulation and strategic policy. Rather than functioning as autonomous sectors, these actors interact through communication networks, shared expectations, and institutional adaptation, which collectively reorganize the innovation system. This perspective positions the Triple Helix as a response to the limitations of national innovation systems and as an analytical lens for understanding the transition toward economies driven by knowledge.

The Quadruple Helix [

49] extends this architecture by acknowledging civil society as a fourth actor whose participation influences legitimacy, social relevance, and democratic accountability within innovation processes. Carayannis highlights that innovation does not emerge exclusively from institutional agreements but also from the cultural context, social values, collective learning, and communicative flows within communities. Civil society contributes experiential knowledge, demands transparency in public decision making, and influences the social acceptance of technological or organizational change. The model emphasizes that contemporary innovation ecosystems require forms of participation that move beyond expert driven configurations and incorporate citizens, media, and cultural environments as active cocreators of knowledge.

The Quintuple Helix [

50] introduces the natural environment as a fifth dimension and reframes innovation as a process inseparable from ecological sustainability. In this model, universities, industry, government, and civil society interact with the natural environment as both a condition and a stakeholder of development. Carayannis argues that societies driven by knowledge must evolve toward models that integrate knowledge and sustainability, where innovation strengthens ecological resilience rather than generating externalities [

50]. The Quintuple Helix links governance, production, learning, and social participation with environmental protection, positioning sustainability criteria as a central mechanism for evaluating the effectiveness of innovation systems and their enduring societal value.

In line with this conceptual evolution, the Quintuple Helix framework requires clear identification of the actors involved and the roles they assume within sustainability-oriented innovation ecosystems. Since the effectiveness of this model depends on how each sphere contributes resources, knowledge, and decision-making capacity, it is necessary to specify the institutional, economic, governmental, social, and environmental dimensions that compose the structure of the helix.

Table 1 presents the five core variables of the Quintuple Helix as applied in this study, offering a theoretical reference that supports later stages of measurement and empirical analysis.

This theoretical evolution also shows that, although the Quintuple Helix offers a systemic foundation for understanding collaboration among multiple actors, there is no clear consensus on how social innovation should be measured at the institutional level, particularly within higher education extension projects focused on sustainability. Several international models and indexes have been developed to evaluate innovation or social progress; however, most operate at national or macro scales, emphasize technological or economic performance, or depend on broad indicator structures that are difficult to apply within universities and their community outreach ecosystems.

To contextualize the gap that motivates the present study,

Table 2 summarizes the main characteristics and limitations of the most frequently referenced models.

In summary, while these models offer significant conceptual contributions, none provides an institutional level mechanism to measure sustainability oriented social innovation arising from university extension projects. The gap lies between macro frameworks that capture national innovation dynamics and micro approaches that describe local practices without offering an operational evaluation tool. The present study responds to this gap by proposing a model that integrates Quintuple Helix configurations with sustainability criteria and validates institutional impact trajectories through PCA and SEM.

In this regard, the measurement model proposed in this study is primarily framed within the sociopolitical governance current, as it focuses on the articulation among university, industry, government, society, and the natural environment as actors of Quintuple Helix. It also incorporates elements from the strategic management current by developing a statistical instrument to evaluate institutional performance in social innovation and intersects transversally with the sustainability current by considering the environmental component and its alignment with the Sustainable Development Goals. This positioning allows the model to be situated within a recognized theoretical framework and compared with consolidated international approaches.

However, social innovation is related to new products, services, and models whose purpose is to improve human wellbeing and promote social relationships and forms of collaboration [

50] and does not necessarily require the simultaneous participation of all actors in the Quintuple Helix. Rather, it depends on the extent to which those involved share a clearly defined social mission: “the fundamental element of a social oriented business model is having a clearly established mission, which enables strategic progress, the definition of a value proposition, and the adoption of good practices in business development [

52].” Thus, it is not always essential for all actors to be present, but rather that they align around the two essential characteristics of the social innovation process: social action and social change. Social innovations represent a form of social transformation because they affect the future development of society and balance temporal trends [

53].

Recent international literature has identified at least four major currents that structure the field of social innovation: (i) social entrepreneurship and the third sector, (ii) strategic management and organizational innovation, (iii) sociopolitical aspects and urban governance, and (iv) sustainability-oriented innovation [

54]. This classification helps situate various social innovation experiences within a broader theoretical landscape and underscores the need for inter and transdisciplinary approaches to address complex social issues from multiple angles.

For this study, to clarify the conceptual scope of the construct “impact on social innovation,” the following operational distinction is presented to specify what is being measured and at which analytical level it is situated. The approach adopted does not assess direct social outcomes in communities, but rather the institutional perceived impact resulting from the articulation of Quintuple Helix actors within university extension projects. Four analytical levels are therefore distinguished among: inputs, processes, outputs, and impacts, which delineate the transition from enabling conditions to interaction dynamics and institutional effects.

Table 3 presents this conceptual structure and illustrates how each dimension is integrated into the applied statistical model.

The reviewed literature comes from diverse contexts (Europe, Asia, and Latin Ameri-ca), providing a more comprehensive understanding of the role of universities in generating social innovation. In Europe, for example, the role of civic universities is highlighted, whose impact depends on both internal and external factors [

32]. In Asia and Latin America, it is emphasized that “the university must assume a more active role in territorial development, based on proposals for creating sustainable spaces [

40],” and that “social responsibility and sustainable development are still far from being fully integrated into the core activities of HEIs [

38].”

2. Materials and Methods

A systematic literature review was initially conducted to identify how authors conceptualize the generation of social innovation and its relationship with the Quintuple Helix model. Subsequently, and following a sequential process, a data collection instrument was designed and validated by a panel of 10 experts with experience in university extension and social outreach. Assuming an expected proportion of 50% (p = 0.5), the margin of error adjusted for a finite population was calculated. Using the finite population correction formula, a margin of error of 9.65% was obtained at a 95% confidence level, ensuring that the results are statistically reliable and representative for the proposed analysis, given the sample size and the characteristics of the population frame. The total population was 301 Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) in Colombia. A sample of 77 universities was selected, including only the main campus of each institution. The sampling process was random to avoid bias related to voluntary participation. Once the sample was defined, the data collection instrument was sent to each university to apply it internally. A formal invitation was sent to the Academic Vice Rectory or the Office of Extension of each selected institution, requesting the completion of the instrument at the institutional level. The information collected corresponds to a single consolidated response per university, reflecting an internal institutional assessment rather than individual opinions. All selected universities agreed to participate.

Respondents were asked to rate, on a scale from 0 to 10, the impact of their social extension projects on the generation of social innovation, based on their articulation with academia, industry, government, society, and the environment.

To process the data, multivariate segmentation techniques and machine learning methods were used, employing the statistical software R (version 4.3.3).

The results were divided into two phases. In the first phase, referred to as exploratory dimensional structuring, Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was conducted to classify the universities into three groups. These groups were analyzed independently and compared with each other to determine their level of impact on the generation of social innovation. This phase revealed that, in Colombia, HEIs generate different levels of social innovation impact (low, medium, and high), depending on how the actors of the Quintuple Helix are articulated within their extension and social outreach projects.

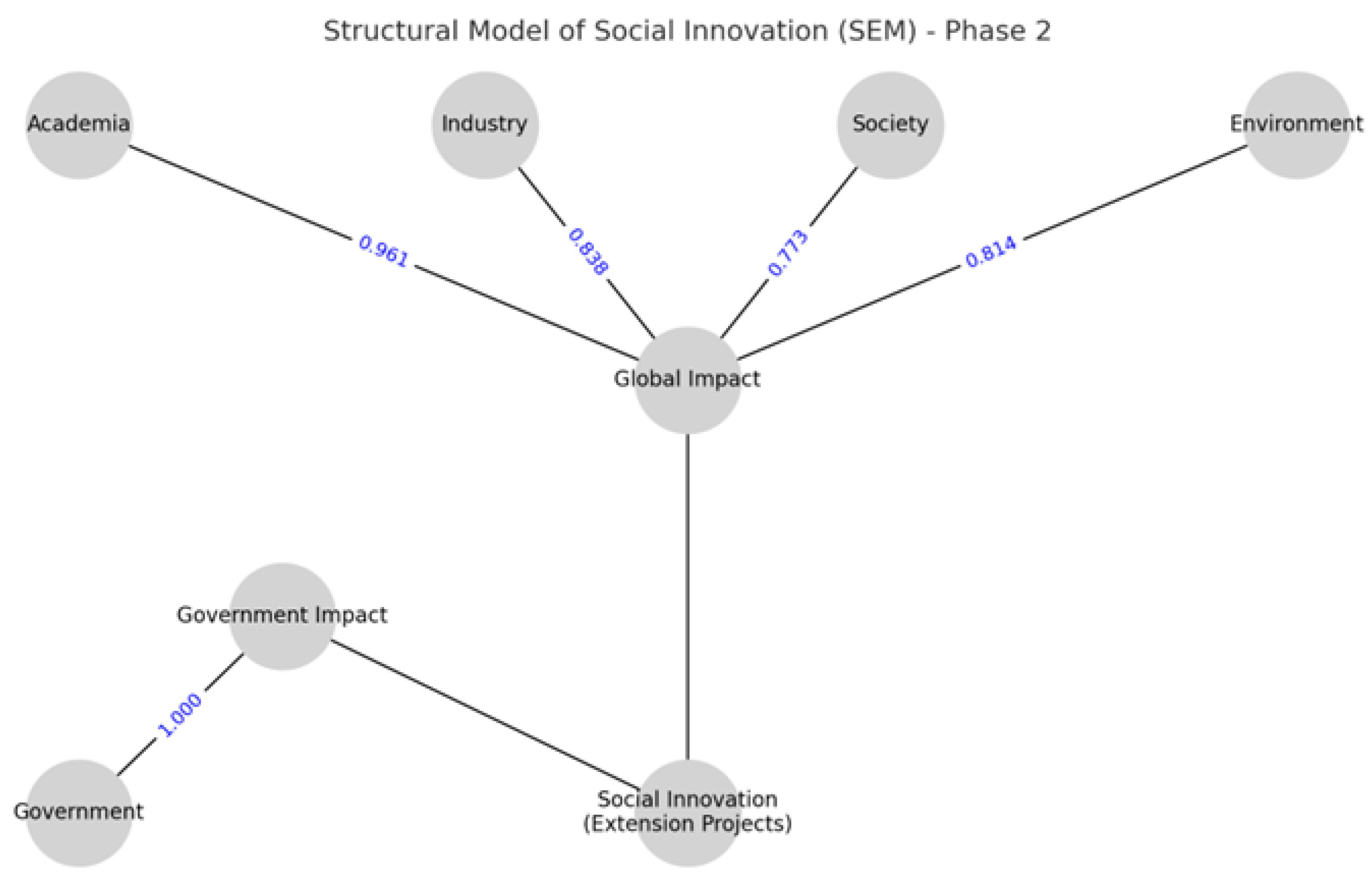

The second phase, referred to as confirmatory structural modeling, involved the formulation and validation of a theoretical model using latent variables through Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) as a confirmatory technique. Based on the overall PCA results (not the grouped results), factor loadings, composite reliability, convergent validity, and model fit were estimated. This phase allowed for the statistical verification of the construct “impact on social innovation,” resulting in a structural equation that can be applied to any HEI to measure the impact of its extension projects on the generation of social innovation. This impact is measured through its global impact (GI), composed of the variables academia, industry, civil society, and environment, as well as its governmental impact (GIv), composed of the government variable.

This study therefore seeks to answer the following question: How can the impacts of university social extension projects be measured through the QH model to assess the generation of social innovation?

Generative Artificial Intelligence through ChatGPT version 5.2 tools was used to improve the clarity and visual quality of the figures. The authors reviewed and validated all content, and the use of these tools did not influence the study design, data analysis, or interpretation of results.

4. Discussion

4.1. Theoretical Interpretation of Findings

From a sustainability perspective, the results demonstrate that HEIs contribute directly to several Sustainable Development Goals. Rather than functioning as isolated outreach activities, extension projects operate as strategic mechanisms that articulate local knowledge, institutional capabilities, and territorial collaboration. Their alignment with SDG 4, SDG 10, and SDG 17 reflects not only programmatic intentions but the concrete capacity of universities to configure multi actor governance structures that enable social transformation.

The model proposed represents a significant contribution to the literature on social innovation (SI) and its empirical evaluation within the context of Higher Education Institutions (HEIs). The findings of this research demonstrate that it is possible to structure a statistical instrument, validated through structural equation modeling, that enables the categorization and differentiated measurement of the impact generated by universities, recognizing their level of articulation with the five QH actors: academia, industry, government, civil society, and the environment.

The incorporation of the environmental dimension within the Global Impact construct reinforces the relevance of the Quintuple Helix as a sustainability framework rather than solely an innovation model. Consequently, the proposed structure provides HEIs and policymakers with a tool capable of evaluating and improving social innovation trajectories while recognizing institutional heterogeneity. This departs from traditional evaluation approaches by demonstrating that sustainability outcomes depend on how each university configures relationships among helix actors, rather than on the presence of all of them simultaneously Carayannis and Campbell [

50].

This result is consistent with the literature suggesting that social innovations become consolidated when a “triad” is formed by a core group of committed local actors, the hierarchical support of the state, and the presence of intermediary structures that facilitate coordination between both levels [

55]. This perspective reinforces the importance of incorporating participatory governance dynamics into university extension projects to ensure their sustainability and scalability over time.

4.2. Practical and Policy Implications

Moreover, the novelty of the proposed model does not lie solely in its conceptual grounding, but in its operational applicability. Unlike TEPSIE (Theoretical, Empirical and Policy Foundations for Social Innovation in Europe), which introduces dimensions such as empowerment, systemic change and social outcomes without providing a mechanism capable of translating them into measurable institutional results [

52], or the SIM (Social Innovation Measurement) model promoted by the European Commission, whose applicability is limited due to its dependence on European policy frameworks and contextual specificities (European Commission, SIM Framework), the model presented here establishes a measurable pathway that links Quintuple Helix actor configurations with sustainability outcomes through PCA and SEM validation.

Compared to macro level indices such as the Social Progress Index (SPI), the Summary Innovation Index (SII) or the Global Innovation Index (GII), which assess performance on the national scale and do not measure social innovation within universities, the proposed approach operates at the institutional level and captures the dynamics of university extension ecosystems. Likewise, while the Technology Achievement Index (TAI) prioritizes technological performance and excludes social mission or community value, and RESINDEX remains exploratory and non-scalable beyond regional pilots [

51], the present model responds to these limitations by integrating social, environmental and organizational indicators aligned with the mission of Higher Education Institutions.

In this regard, the present research helps address one of the most frequently noted gaps in literature: the lack of tools for evaluating the impact of social innovation, particularly in rural and educational contexts. Previous studies have highlighted that the absence of specific instruments limits the capacity to demonstrate the social, economic, environmental, and institutional value generated by social innovation initiatives [

54,

56]. In this sense, the model developed here represents a methodological contribution toward achieving more comprehensive and comparable evaluations.

Thus, rather than replacing existing approaches, the contribution of this study lies in bridging the gap between macro innovation metrics and the operational needs of universities. By offering an evaluation structure applicable to HEIs with different governance models, resource asymmetries and territorial mandates, the model complements previous frameworks and provides a consistent mechanism for assessing sustainability-oriented social innovation in extension projects, particularly where traditional indicators fail to reflect institutional impact trajectories.

At a macro level, this tool can support entities such as ministries, university networks, or accreditation agencies in the comparative evaluation of social impacts across universities. Therefore, the study aligns with the global trend in social innovation research, which highlights an increasing convergence between theoretical advancements and practical implementations [

4].

Moreover, this model is replicable in other national and international contexts. Coun-tries in Latin America, Eastern Europe, or Southeast Asia where university extension is an expanding yet still weakly standardized function, could adopt and adapt this approach according to their own political, social, and environmental realities. In this regard, studies on collaboration between universities and communities support the need for structured tools that allow for the evaluation of such partnerships from a transformative innovation perspective [

31,

33].

The governmental impact included in the structural equation highlights the fundamental role that political support and governmental initiatives play in the generation of social innovation, specifically, in this case, through university extension and social outreach projects carried out by HEIs but also as evidenced in broader studies on social innovation across different contexts [

4].

4.3. Context Dependence and Generalizability

In the Latin American context, authors have emphasized the need for social innovation (SI) evaluation models that are adapted to local conditions, integrate multiple forms of knowledge, and prioritize community impact [

57]. This study responds to that need by incorporating direct perceptions from Colombian HEIs and structuring a model that is sensitive to their institutional heterogeneity, as demonstrated by the cluster analysis, which groups universities according to their level of impact.

The results also allow for questioning the traditional notion that social innovation necessarily requires the simultaneous participation of all actors in the helix. While such participation may be ideal, the study shows that there are effective combinations of helix actors that generate significant impacts depending on the institutional context. This flexibility within the model is consistent with the perspective of Carayannis et al. [

53], who argue that innovation configurations must be dynamic and adaptable to territorial conditions.

An additional contribution of the model is its practical applicability. By generating equations with standardized and statistically validated loadings, HEIs can use this instrument not only for institutional diagnostics but also for monitoring processes, accountability, and continuous improvement of their extension activities. In this sense the PCA grouping presented in the Results

Section 3 offers more than a statistical clustering of institutions, and evidence how systemic differences between types of universities, condition the emergence of sustainability oriented social innovation. Thus, the model recognizes that universities do not operate under homogeneous conditions and that impact varies according to governance structures, resources, and territorial mandates.

Furthermore, the results underscore the importance of promoting the inclusion of historically marginalized groups, an aspect also emphasized by recent studies on social innovation in vulnerable urban contexts. These studies show that social innovation can become a tool to give visibility to overlooked communities, strengthen their capacities, generate social capital, and empower them as active agents of change [

58]. This approach aligns with the purpose of the “society” helix in the proposed model, which seeks to ensure that university extension projects respond to the real needs of communities.

4.4. Normative Assumptions and Structural Challenges of the Quintuple Helix

Despite its growing academic adoption, the Quintuple Helix model has been criticized for its markedly normative orientation. It assumes that collaboration among academia, industry, government, civil society, and the environment should occur in a coordinated and mutually reinforcing manner to support sustainability outcomes. However, this expectation does not always align with real institutional dynamics. In practice, collaboration is conditioned by divergent interests, hierarchical structures, differences in access to knowledge, and institutional barriers that restrict shared decision making.

As a result, the Quintuple Helix model can risk presenting an aspirational ideal of governance rather than a configuration that consistently materializes in social innovation ecosystems.

A second recurrent critique concerns the unrealistic expectation of symmetric participation among the five helices. Existing literature shows that the power and influence of actors are structurally uneven: governments centralize regulatory authority and resources; industry tends to prioritize profitability; academia operates under scientific and accreditation incentives; civil society often faces representational and financial constraints; and the environmental helix typically lacks institutional agency of its own. Consequently, the assumption that all actors contribute at comparable levels does not reflect scenarios where one or two helices dominate strategic direction and impact generation.

The empirical evidence of this study aligns with these critiques. The configurations observed in university extension projects indicate that collaboration is not grounded in symmetry, but rather in the strategic complementarity of roles and capacities. The proposed model acknowledges these structural asymmetries by evaluating configurations without penalizing the absence or limited participation of one actor, and by identifying which combinations are most effective for generating social innovation oriented toward sustainability in specific institutional and territorial contexts. In doing so, this research contributes to a more pragmatic understanding of the Quintuple Helix, situated between its normative aspirations and the complex reality of intersectoral relationships.

4.5. Methodological Limitations and Subjectivity Considerations

In this study, the construct “impact on social innovation” refers to the institutional perceived impact generated by university extension projects, based on the level of articulation with the five actors of the Quintuple Helix. Therefore, the model does not measure social innovation outcomes directly, but rather the internal institutional assessment of their contribution to sustainability-oriented social innovation.

While the model reduces subjectivity through validation based on PCA and SEM, the indicators used in this study rely on an internal institutional rating scale ranging from 0 to 10. This reliance on internal scoring may introduce elements of subjective bias, social desirability in responses, and variation in evaluation criteria across universities. In local community contexts, impact is often interpreted through narratives of change, social recognition, and perceived benefits, which can vary according to local expectations, power relations, historical trajectories, or institutional agendas. While this does not invalidate the analytical contribution of the model, it establishes a methodological boundary that should be considered when interpreting the results and their generalizability. Future research could strengthen the robustness and external validity of the model by triangulating the 0 to 10 scale with administrative records, documented project outputs, community partner perspectives, and longitudinal indicators that track changes over time.

This subjectivity does not invalidate the evaluation; instead, it highlights the limitations of assuming neutral or fully objective measurement processes in social innovation. Recognizing these constraints opens space for future refinements that incorporate qualitative evidence, participatory assessment, and triangulation between institutional reports and community voices.

In this study, the distinction between Global Impact (GI) and Governmental Impact with variability (GIv) reflects conditions specific to the Colombian higher education system, including the regulatory role of the State, the uneven distribution of institutional resources, and the territorial nature of university extension. These factors depend on the local context and may differ in countries with alternative governance structures. However, the underlying evaluation logic that links actor configuration, sustainability criteria, and measurable impact trajectories is generalizable and can be applied in other territories, provided that the GI and GIv dimensions are adapted to the political, institutional, and regulatory characteristics of each context.

In consequence, to clarify the scope and applicability of the model, it is necessary to acknowledge several methodological considerations. (1) The indicators used are based on institutional perception and reported information, which may introduce elements of subjective bias, variation in internal evaluation criteria, and social desirability effects. (2) The model is rooted in the Colombian higher education context, where university extension has a specific regulatory trajectory and historical development, and therefore some constructs are influenced by contextual characteristics. (3) Although the use of Principal Component Analysis and Structural Equation Modeling reduces the risk of overlapping between variables, the presence of conceptual proximity among institutional, social, and environmental dimensions may generate potential multicollinearity, which should be monitored in future applications. (4) Regarding transferability, the model can be applied in other countries; however, its generalization depends on the compatibility of governance structures, the presence of formal extension systems, and the degree of articulation between universities, government, industry, civil society, and the environment. In this sense, the model is not restricted to Colombia, but its effective use outside this context requires adaptation according to regulatory, institutional, and territorial characteristics.

4.6. Additional Considerations and Future Directions

The results of this research open multiple avenues for future studies: longitudinal analyses to observe the evolution of impacts; multigroup comparisons between public and private universities or across regions; integration of qualitative indicators such as change narratives or community testimonies; and the expansion of the model to incorporate emerging dimensions such as digital transformation, artificial intelligence for the common good, or climate sustainability. In this regard, the integration of digital technologies, including artificial intelligence and blockchain, is enhancing efficiency, transparency, and participation in social innovation processes [

4]. This underscores the need to strengthen collaboration among universities, companies, and governments key components of the industry helix, to incorporate technological tools that amplify the reach and impact of such initiatives.

In summary, this research not only responds to the need to measure the impact of social innovation within HEIs but also proposes a validated, adaptive, and replicable theoretical and methodological model with strong potential to influence public policies and transform higher education from a social value perspective.

Finally, it is important to note that, as highlighted in the literature, there remains a shortage of longitudinal studies that enable the evaluation of sustainability and enduring impacts of social innovations [

54]. Likewise, international research has emphasized that the effectiveness of such initiatives depends largely on their capacity to adapt to local contexts, leveraging the capacities and specific characteristics of each territory [

59]. Therefore, future studies should apply the model developed here across diverse institutional and territorial settings to validate its relevance and generalizability.