The Influence of Green Shared Vision on Employee Pro-Environmental Behaviour: The Mediating Role of Green Intrinsic Motivation and Green Mindfulness

Abstract

1. Introduction

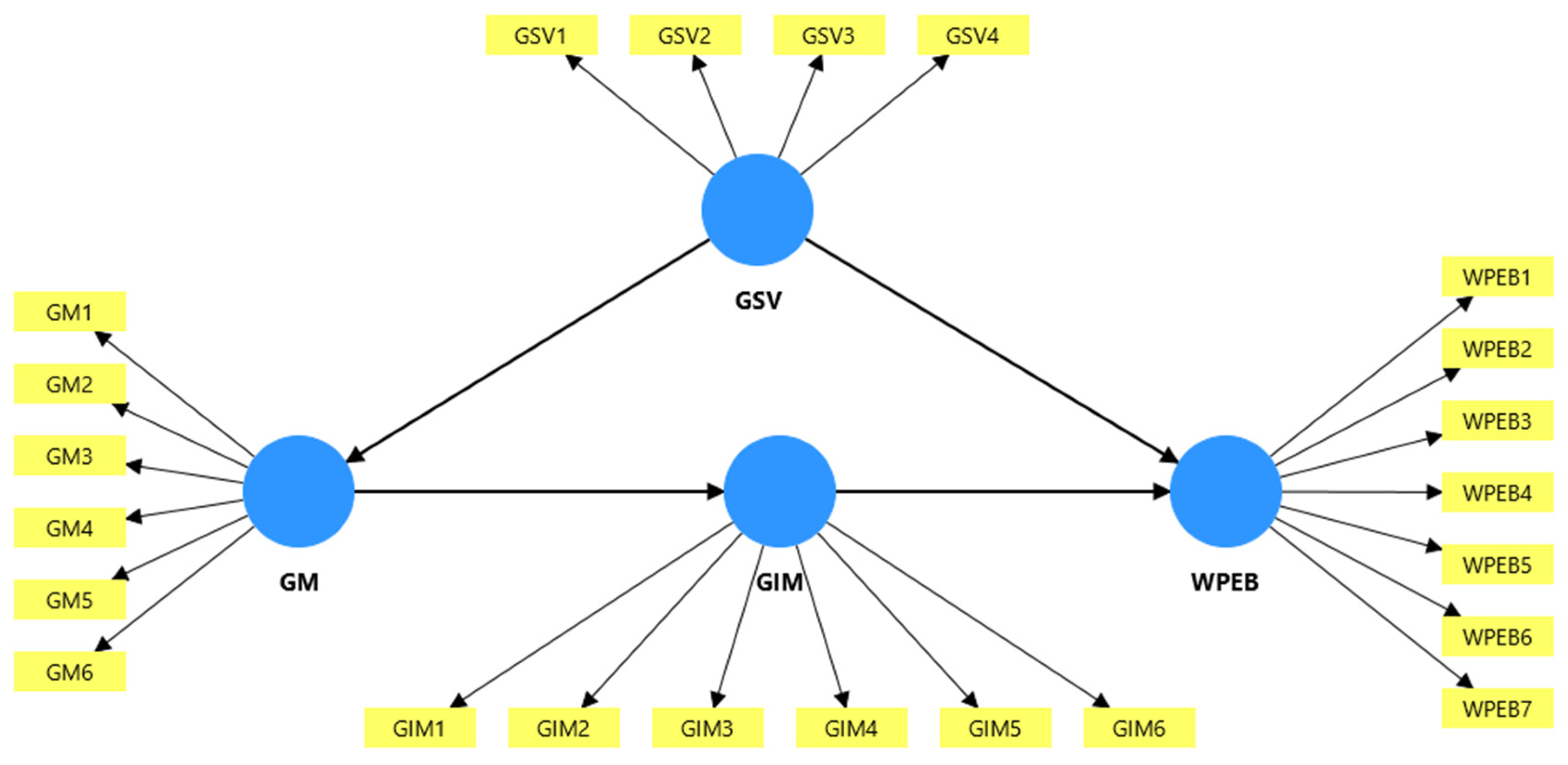

2. Literature Review

2.1. Green Shared Vision and Workplace Pro-Environmental Behaviour

2.2. Green Shared Vision, Green Mindfulness, and Green Intrinsic Motivation

2.3. Green Intrinsic Motivation and Workplace Pro-Environmental Behaviour

2.4. Green Mindfulness and Green Intrinsic Motivation

2.5. Mediating Effects

3. Method

3.1. Participants and Procedure

3.2. Measurement Variables

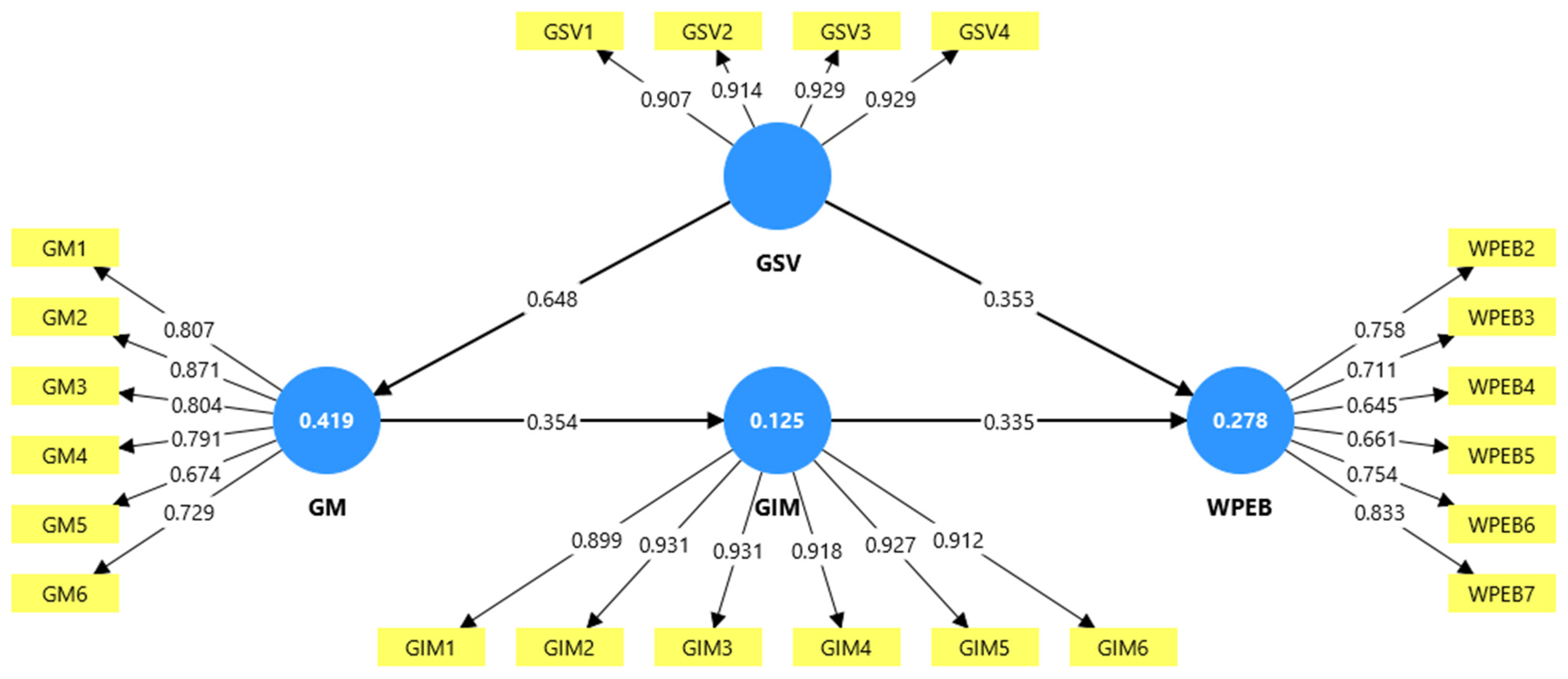

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

6.1. Theoretical Implications

6.2. Practical Implications

6.3. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ones, D.S.; Dilchert, S. Environmental sustainability at work: A call to action. Ind. Organ. Psychol. 2012, 5, 444–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dangelico, R.M.; Pujari, D. Mainstreaming green product innovation: Why and how companies integrate environmental sustainability. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 95, 471–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, G.; Ren, S.; Wang, M.; Li, Y.; Zhang, S. Employee green behaviour: A review and recommendations for future research. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2023, 25, 297–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.S.; Chang, C.H.; Yeh, S.L.; Cheng, H.I. Green shared vision and green creativity: The mediation roles of green mindfulness and green self-efficacy. Qual. Quant. 2015, 49, 1169–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afsar, B.; Maqsoom, A.; Shahjehan, A.; Afridi, S.A.; Nawaz, A.; Fazliani, H. Responsible leadership and employee’s proenvironmental behavior: The role of organizational commitment, green shared vision, and internal environmental locus of control. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 297–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghaei, M.; Aghaee, S.; Shahriari, M. The effect of green vision and green training on voluntary employee green behaviour: The mediating role of green mindfulness. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: Classic definitions and new directions. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2000, 25, 54–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faraz, N.A.; Ahmed, F.; Ying, M.; Mehmood, S.A. The interplay of green servant leadership, self-efficacy, and intrinsic motivation in predicting employees’ pro-environmental behavior. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2021, 28, 1171–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wamsler, C.; Brink, E. Mindsets for sustainability: Exploring the link between mindfulness and sustainable climate adaptation. Ecol. Econ. 2018, 151, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychol. Inq. 2000, 11, 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latif, B.; Gunarathne, N.; Gaskin, J.; San Ong, T.; Ali, M. Environmental corporate social responsibility and pro-environmental behavior: The effect of green shared vision and personal ties. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 186, 106572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.-W.; Chen, F.-F.; Luan, H.-D.; Chen, Y.-S. Effect of Green Organizational Identity, Green Shared Vision, and Organizational Citizenship Behavior for the Environment on Green Product Development Performance. Sustainability 2019, 11, 617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Yao, L.; Ma, R.; Sarmad, M.; Orangzab; Ayub, A.; Jun, Z. How green mindfulness and green shared vision interact to influence green creative behavior. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2023, 16, 1707–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.S.; Chang, C.H.; Lin, Y.H. The determinants of green radical and incremental innovation performance: Green shared vision, green absorptive capacity, and green organizational ambidexterity. Sustainability 2014, 6, 7787–7806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Graves, L.M.; Sarkis, J.; Zhu, Q. How transformational leadership and employee motivation combine to predict employee proenvironmental behaviors in China. J. Environ. Psychol. 2013, 35, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, J.L.; Barling, J. Greening organizations through leaders’ influence on employees’ pro-environmental behaviors. J. Organ. Behav. 2013, 34, 176–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coccia, M. Comparative incentive systems. In Global Encyclopedia of Public Administration, Public Policy, and Governance; Farazmand, A., Ed.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, Y.H.; Wang, C.K.; Lin, C.Y. Antecedents and consequences of green mindfulness: A conceptual model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, K.W.; Ryan, R.M. The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 84, 822–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Research on intrinsic and extrinsic motivation is alive, well, and reshaping 21st-century management approaches: Brief reply to Locke and Schattke. Motiv. Sci. 2019, 5, 291–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Olafsen, A.H.; Ryan, R.M. Self-determination theory in work organizations: The state of a science. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2017, 4, 19–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khamdamov, A.; Tang, Z.; Hussain, M.A. Unpacking parallel mediation processes between green HRM practices and sustainable environmental performance: Evidence from Uzbekistan. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbaro, N.; Pickett, S.M. Mindfully green: Examining the effect of connectedness to nature on the relationship between mindfulness and engagement in pro-environmental behavior. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2016, 93, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afsar, B.; Badir, Y.; Kiani, U.S. Linking spiritual leadership and employee pro-environmental behavior: The influence of workplace spirituality, intrinsic motivation, and environmental passion. J. Environ. Psychol. 2016, 45, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Bhutto, T.A.; Xuhui, W.; Maitlo, Q.; Zafar, A.U.; Bhutto, N.A. Unlocking employees’ green creativity: The effects of green transformational leadership, green intrinsic, and extrinsic motivation. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 255, 120229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Gagné, M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and work motivation. J. Organ. Behav. 2005, 26, 331–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Rasheed, A.; Ayub, A. Does green mindfulness promote green organizational citizenship behavior: A moderated mediation model. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C.M.; Wende, S.; Becker, J.-M. SmartPLS 4. Bönningstedt: SmartPLS. 2024. Available online: https://www.smartpls.com (accessed on 26 July 2025).

- Hulland, J. Use of partial least squares (PLS) in strategic management research: A review of four recent studies. Strateg. Manag. J. 1999, 20, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memon, A.H.; Rahman, I.A. SEM-PLS analysis of inhibiting factors of cost performance for large construction projects in Malaysia: Perspective of clients and consultants. Sci. World J. 2014, 2014, 165158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ab Hamid, M.R.; Sami, W.; Sidek, M.M. Discriminant validity assessment: Use of Fornell & Larcker criterion versus HTMT criterion. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2017, 890, 012163. [Google Scholar]

- Yana, A.G.A.; Rusdhi, H.A.; Wibowo, M.A. Analysis of factors affecting design changes in construction project with Partial Least Square (PLS). Procedia Eng. 2015, 125, 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Pearson Education: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- JASP. Version 0.19.3, Computer Software. 2024. Available online: https://jasp-stats.org/ (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 2nd ed.; Sage: Riverside County, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: Sensitivity to underparameterized model misspecification. Psychol. Methods 1998, 3, 424–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taber, K.S. The use of Cronbach’s alpha when developing and reporting research instruments in science education. Res. Sci. Educ. 2018, 48, 1273–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Sarstedt, M.; Hopkins, L.; Kuppelwieser, V.G. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): An emerging tool in business research. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2014, 26, 106–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantabutra, S. Toward an organizational theory of sustainability vision. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vongariyajit, N.; Kantabutra, S. A Test of the Sustainability Vision Theory: Is It Practical? Sustainability 2021, 13, 7534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew, I.K.H.; Chong, P. Effects of strategic human resource management on strategic vision. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 1999, 10, 1031–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, R.D.; Akdere, M. Effective organizational vision: Implications for human resource development. Eur. J. Ind. Train. 2007, 31, 100–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laser, J. The importance of vision statements for human resource management–functions of human resource management in creating and leveraging vision statements. SHR Rev. 2021, 20, 145–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Kim, E.J. Organizational culture, leaders’ vision of talent, and HR functions on career changers’ commitment: The moderating effect of training in South Korea. Asia Pac. J. Hum. Resour. 2019, 57, 345–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slåtten, T.; Mutonyi, B.R.; Lien, G. Does organizational vision really matter? An empirical examination of factors related to organizational vision integration among hospital employees. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Constructs | Items | Codes | Source of the Scale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Green shared vision (GSV) | “A commonality of environmental goals exists in the company.” | GSV1 | [4] |

| “A total agreement on the strategic environmental direction of the organisation.” | GSV2 | ||

| “All members in the organisation are committed to the environmental strategies.” | GSV3 | ||

| “Employees of the organisation are enthusiastic about the collective environmental mission of the organisation.” | GSV4 | ||

| Green mindfulness (GM) | “The members of the green innovation project feel free to discuss environmental issues and problems.” | GM1 | [4] |

| “The members of the green innovation project are encouraged to express different views with respect | GM2 | ||

| to environmental issues and problems.” | GM3 | ||

| “The members of the green innovation project pay attention to what is happening if unexpected environmental issues and problems arise.” | GM4 | ||

| “The members of the green innovation project are inclined to report environmental information and knowledge that have significant consequences.” | GM5 | ||

| “The members of the green innovation project are rewarded if they share and announce new environmental information and knowledge.” | GM6 | ||

| Green intrinsic motivation (GIM) | I enjoy “coming up with new green ideas.” | GIM1 | [27] |

| I enjoy “trying to solve environmental tasks on the job.” | GIM2 | ||

| I enjoy “tackling with environmental tasks that are completely new.” | GIM3 | ||

| I enjoy “improving existing green ideas at my job.” | GIM4 | ||

| I feel “excited when I have new green ideas.” | GIM5 | ||

| I feel “like becoming further engaged in the development of green ideas.” | GIM6 | ||

| Workplace pro-environmental behaviour (WPEB) | “I print double-sided whenever possible.” | WPEB1 | [18] |

| “I put compostable items in the compost bin.” | WPEB2 | ||

| “I put recyclable material (e.g., cans, paper, bottles, batteries) in the recycling bins.” | WPEB3 | ||

| “I bring reusable eating utensils to work (e.g., travel coffee mug, water bottle, reusable containers, reusable cutlery).” | WPEB4 | ||

| “I turn lights off when not in use.” | WPEB5 | ||

| “I take part in environmentally friendly programmes (e.g., bike/walk to work day, bring your own local lunch day).” | WPEB6 | ||

| “I make suggestions about environmentally friendly practices to managers and/or environmental committees, in an effort to increase my organization’s environmental performance.” | WPEB7 |

| Frequency | Percent | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 109 | 70.8 |

| Male | 45 | 29.2 | |

| Age | 18–24 | 16 | 10.4 |

| 25–34 | 30 | 19.5 | |

| 35–44 | 37 | 24 | |

| 45–54 | 49 | 31.8 | |

| 55–64 | 20 | 13 | |

| 65 and over | 2 | 1.3 | |

| Work experience (years) | Less than a year | 15 | 9.7 |

| 1–5 | 36 | 23.4 | |

| 6–10 | 35 | 22.7 | |

| 11–15 | 14 | 9.1 | |

| 16–20 | 16 | 10.4 | |

| 21 and more | 38 | 24.7 |

| CODES | Outer Loadings | VIF |

|---|---|---|

| GIM1 | 0.899 | 3.847 |

| GIM2 | 0.931 | 5.484 |

| GIM3 | 0.930 | 5.305 |

| GIM4 | 0.918 | 4.176 |

| GIM5 | 0.928 | 6.133 |

| GIM6 | 0.913 | 5.058 |

| GM1 | 0.807 | 2.966 |

| GM2 | 0.871 | 3.262 |

| GM3 | 0.804 | 2.367 |

| GM4 | 0.791 | 2.382 |

| GM5 | 0.674 | 1.623 |

| GM6 | 0.729 | 1.801 |

| GSV1 | 0.907 | 4.198 |

| GSV2 | 0.914 | 4.361 |

| GSV3 | 0.929 | 6.639 |

| GSV4 | 0.929 | 6.587 |

| WPEB1 | 0.514 | 1.230 |

| WPEB2 | 0.756 | 1.769 |

| WPEB3 | 0.707 | 2.125 |

| WPEB4 | 0.643 | 1.537 |

| WPEB5 | 0.673 | 1.932 |

| WPEB6 | 0.736 | 2.104 |

| WPEB7 | 0.818 | 2.595 |

| Unrotated Solution | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eigenvalues | SumSq. Loadings | Proportion Var. | Cumulative | |

| Factor 1 | 8.757 | 8.138 | 0.354 | 0.354 |

| Codes | Mean | Standard Deviation | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GIM1 | 4.240 | 0.929 | −1.637 | 3.152 |

| GIM2 | 4.221 | 0.850 | −1.671 | 4.057 |

| GIM3 | 4.156 | 0.879 | −1.421 | 2.852 |

| GIM4 | 4.234 | 0.854 | −1.491 | 3.050 |

| GIM5 | 4.266 | 0.893 | −1.723 | 3.621 |

| GIM6 | 4.227 | 0.939 | −1.620 | 2.988 |

| WPEB2 | 4.071 | 1.150 | −1.266 | 0.784 |

| WPEB3 | 4.565 | 0.749 | −1.926 | 3.486 |

| WPEB4 | 4.299 | 0.894 | −1.183 | 0.835 |

| WPEB5 | 4.610 | 0.761 | −2.363 | 5.907 |

| WPEB6 | 3.545 | 1.172 | −0.580 | −0.442 |

| WPEB7 | 3.675 | 1.125 | −0.641 | −0.252 |

| GSV1 | 3.935 | 0.919 | −0.892 | 0.854 |

| GSV2 | 3.896 | 0.985 | −0.830 | 0.460 |

| GSV3 | 3.760 | 0.984 | −0.710 | 0.386 |

| GSV4 | 3.805 | 0.964 | −0.797 | 0.684 |

| GM1 | 4.325 | 0.808 | −1.339 | 2.079 |

| GM2 | 4.195 | 0.886 | −1.250 | 1.930 |

| GM3 | 4.351 | 0.632 | −0.601 | 0.214 |

| GM4 | 4.331 | 0.696 | −1.262 | 3.356 |

| GM5 | 3.370 | 1.199 | −0.380 | −0.572 |

| GM6 | 3.994 | 0.925 | −1.090 | 1.462 |

| Codes | Cronbach’s Alpha | Composite Reliability (rho_a) | Composite Reliability (rho_c) | Average Variance Extracted (AVE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GIM | 0.964 | 0.968 | 0.971 | 0.846 |

| GM | 0.871 | 0.882 | 0.904 | 0.611 |

| GSV | 0.939 | 0.940 | 0.956 | 0.846 |

| WPEB | 0.828 | 0.857 | 0.872 | 0.533 |

| Codes | GIM | GM | GSV | WPEB |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GIM | 0.920 | |||

| GM | 0.354 | 0.782 | ||

| GSV | 0.176 | 0.648 | 0.920 | |

| WPEB | 0.397 | 0.604 | 0.412 | 0.730 |

| Mean | Standard Deviation | T Statistics | p-Values | 2.5% | 97.5% | Hypotheses Validation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GSV -> WPEB | 0.438 | 0.068 | 6.328 | 0.000 | 0.279 | 0.549 | H1 validated |

| GSV -> GM | 0.651 | 0.051 | 12.740 | 0.000 | 0.535 | 0.739 | H2a validated |

| GSV -> GM -> GIM | 0.234 | 0.076 | 3.026 | 0.002 | 0.080 | 0.379 | H2b validated |

| GIM -> WPEB | 0.342 | 0.091 | 3.669 | 0.000 | 0.143 | 0.495 | H3 validated |

| GM -> GIM | 0.360 | 0.114 | 3.100 | 0.002 | 0.122 | 0.568 | H4 validated |

| GM -> GIM -> WPEB | 0.124 | 0.056 | 2.128 | 0.033 | 0.038 | 0.253 | H5 validated |

| GSV -> GM -> GIM -> WPEB | 0.081 | 0.037 | 2.094 | 0.036 | 0.025 | 0.166 | H6 validated |

| GIM | GM | GSV | WPEB | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GIM | 0.167 | |||

| GM | 0.143 | |||

| GSV | 0.722 | 0.154 | ||

| WPEB |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Puiu, S.; Yılmaz, S.E.; Udristioiu, M.T. The Influence of Green Shared Vision on Employee Pro-Environmental Behaviour: The Mediating Role of Green Intrinsic Motivation and Green Mindfulness. Sustainability 2026, 18, 1368. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18031368

Puiu S, Yılmaz SE, Udristioiu MT. The Influence of Green Shared Vision on Employee Pro-Environmental Behaviour: The Mediating Role of Green Intrinsic Motivation and Green Mindfulness. Sustainability. 2026; 18(3):1368. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18031368

Chicago/Turabian StylePuiu, Silvia, Sıdıka Ece Yılmaz, and Mihaela Tinca Udristioiu. 2026. "The Influence of Green Shared Vision on Employee Pro-Environmental Behaviour: The Mediating Role of Green Intrinsic Motivation and Green Mindfulness" Sustainability 18, no. 3: 1368. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18031368

APA StylePuiu, S., Yılmaz, S. E., & Udristioiu, M. T. (2026). The Influence of Green Shared Vision on Employee Pro-Environmental Behaviour: The Mediating Role of Green Intrinsic Motivation and Green Mindfulness. Sustainability, 18(3), 1368. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18031368