Sustainable Tourist Satisfaction in Art Museums: Identifying Attributes That Enhance Visitor Experience for Sustainable Cultural Management

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Empirical Overview

4. Study 1

4.1. Data Collection and Preprocessing

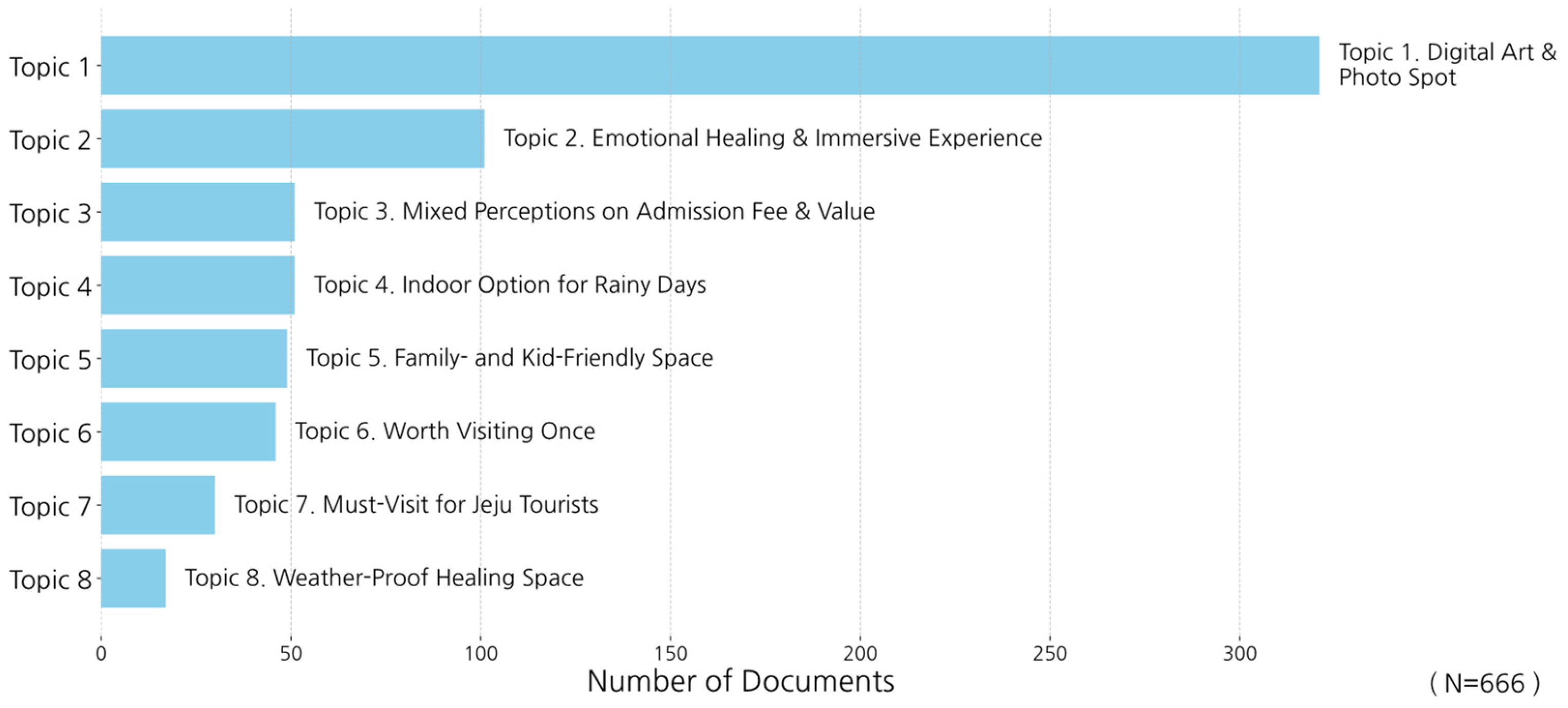

4.2. Topic Modeling

4.3. Result of Topic Modeling

4.3.1. Topic Distribution and Thematic Structure

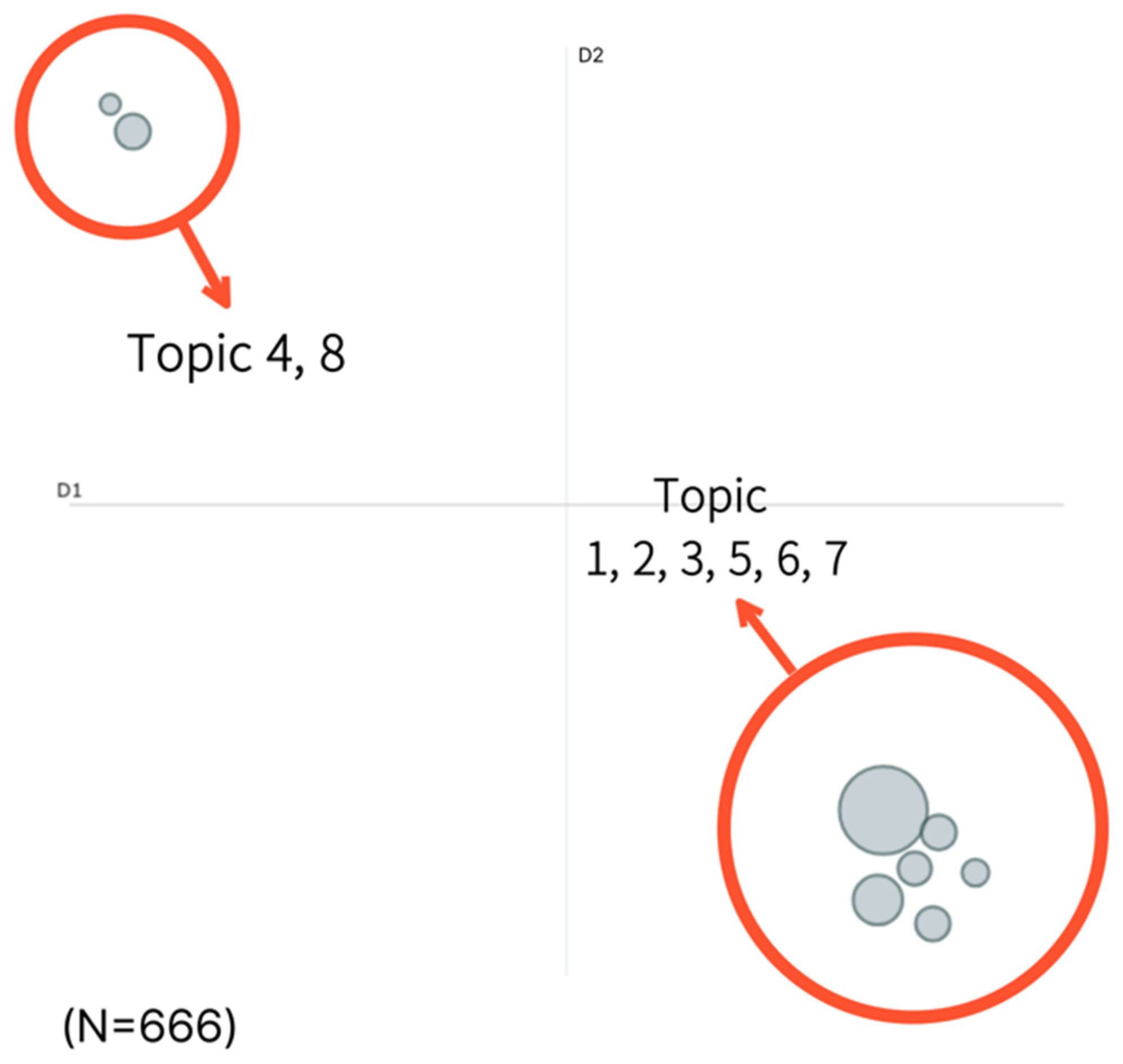

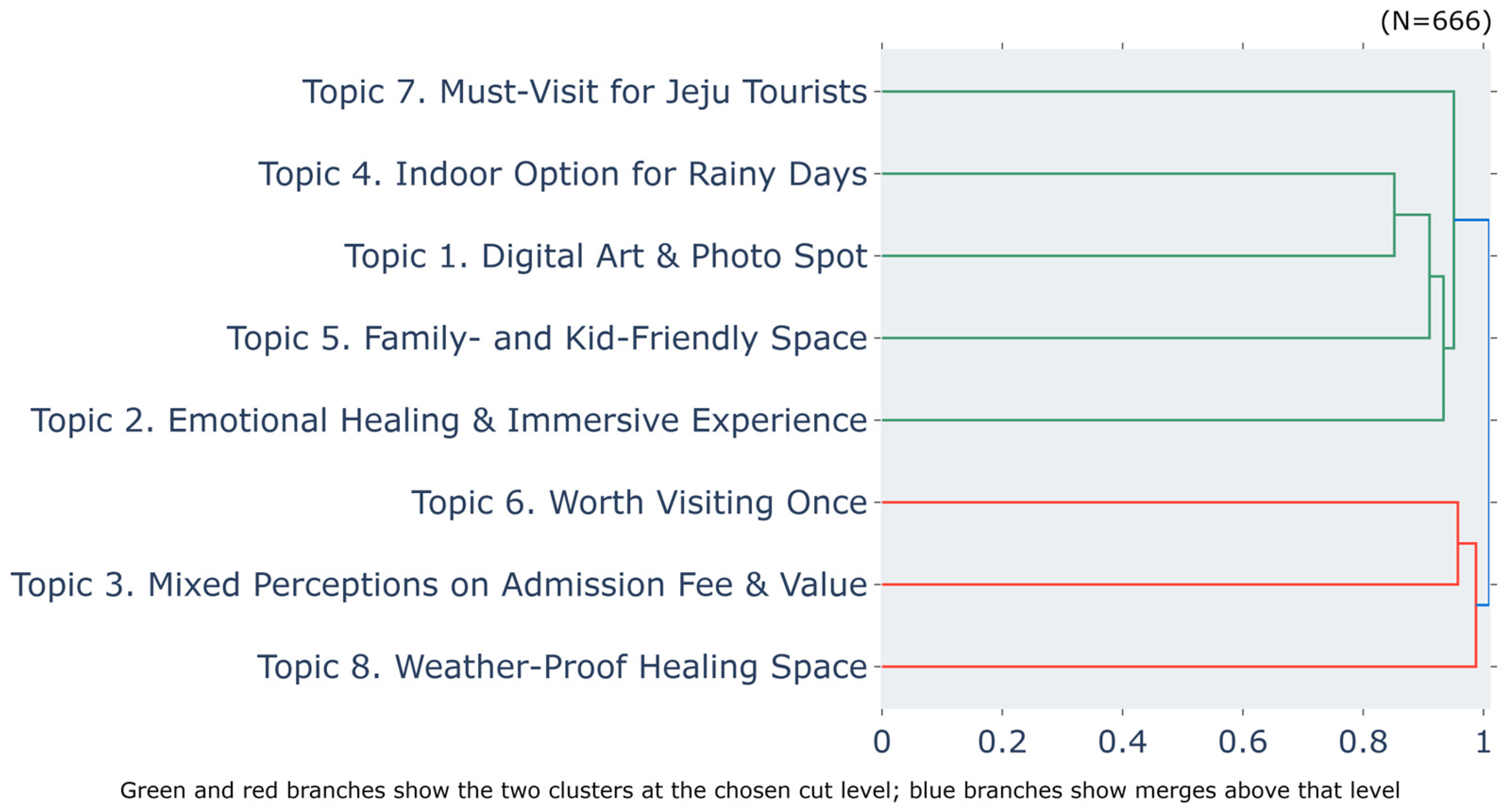

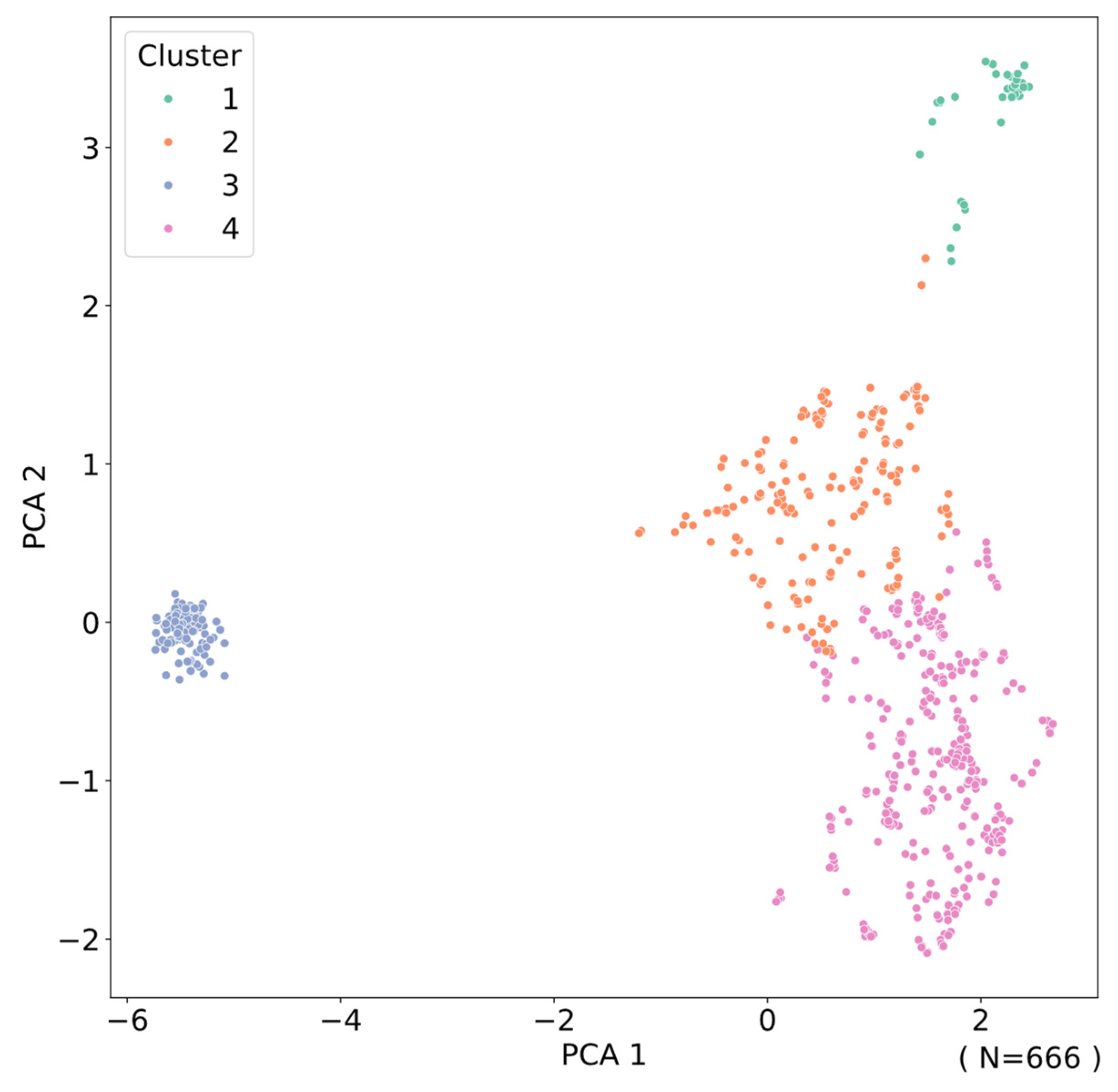

4.3.2. Analysis of Semantic Relationships Between Topics

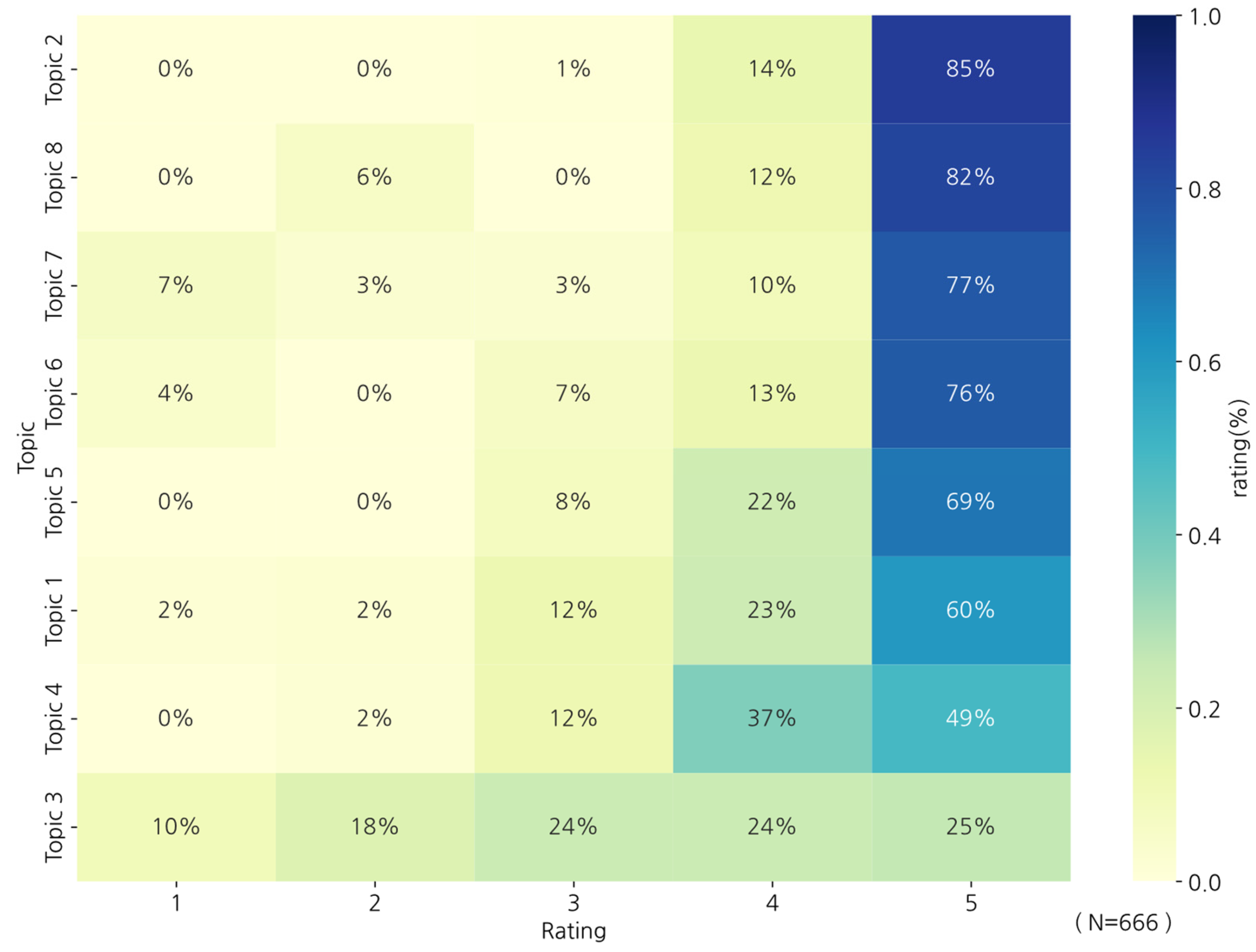

4.3.3. Analysis of Topic-Wise Rating Pattern

5. Study 2

5.1. Measurement Development

5.2. Model Development

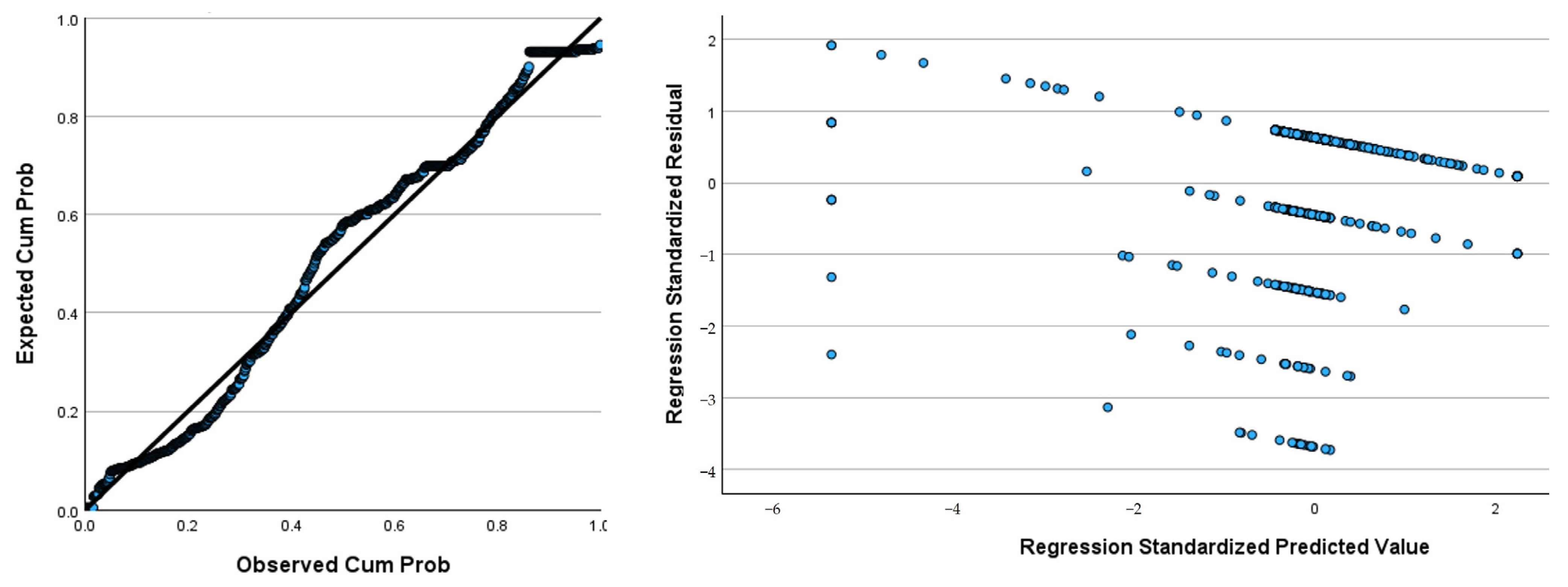

5.3. Results

6. Discussion

6.1. Theoretical Implications

6.2. Practical Implications

6.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhao, X.; Mao, R. Are visitors’ satisfaction reliable? A perspective from museum visitor behavior. Mus. Manag. Curatorship 2025, 40, 96–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanibellato, F.; Rosin, U.; Casarin, F. How the attributes of a museum experience influence electronic word-of-mouth valence: An analysis of online museum reviews. Int. J. Arts Manag. 2018, 21, 76–90. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C.; Elena, G. The World’s Most-Visited Museums 2024: Normality Returns—For Some. The Art Newspaper, 1 April 2025. Available online: https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2025/04/01/the-worlds-most-visited-museums-2024- (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- MarketUS. Global Museums Tourism Market Size, Share, Growth Analysis by Museum Type, by Tourist Type, by Tour Type, by Consumer Orientation, by Region and Companies—Industry Segment Outlook, Market Assessment, Competition Scenario, Statistics, Trends and Forecast 2025–2034. 2025. Available online: https://market.us/report/museums-tourism-market/#:~:text=Key%20Takeaways,often%20showcase%20internationally%20recognized%20masterpieces (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Stylianou-Lambert, T. Gazing from home: Cultural tourism and art museums. Ann. Tour. Res. 2011, 38, 403–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slak Valek, N.; Mura, P. Art and tourism—A systematic review of the literature. Tour. Rev. 2023, 78, 273–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kano, N.; Seraku, N.; Takahashi, F.; Tsuji, S. Attractive quality and must-be quality. Hinshitsu J. Jpn. Soc. Qual. Control 1984, 14, 39–48. [Google Scholar]

- McKercher, B.; du Cros, H. Cultural Tourism: The Partnership Between Tourism and Cultural Heritage Management; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, G. Cultural tourism: A review of recent research and trends. J. Tour. Futures 2018, 4, 203–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, G. Rethinking Cultural Tourism; Edward Elgar: Worcester, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Carrozzino, M.; Bergamasco, M. Beyond virtual museums: Experiencing immersive virtual reality in real museums. J. Cult. Herit. 2010, 11, 452–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tussyadiah, I.; Wang, D.; Jia, C. Virtual reality and tourism experience. Tour. Manag. 2018, 67, 540–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sylaiou, S.; Mania, K.; Karoulis, A.; White, M. Exploring the relationship between presence and enjoyment in virtual museums. Int. J. Hum.–Comput. Stud. 2010, 68, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höllerer, T.; Feiner, S. Mobile augmented reality. Found. Trends Hum.–Comput. Interact. 2016, 2, 1–112. [Google Scholar]

- Pine, B.J.; Gilmore, J.H. The Experience Economy; Harvard Business School Press: Brighton, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Benford, S.; Giannachi, G.; Kolly, J.; Rodden, T. Uncomfortable interactions. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems; ACM Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 2005–2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunkoo, R.; Sharma, A.; So, K.K.F.; Hu, H.; Alrasheedi, A.F. Two decades of research on customer satisfaction: Future research agenda and questions. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2025, 37, 1465–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Bosque, I.A.R.; San Martín, H.; Collado, J. The role of expectations in the consumer satisfaction formation process: Empirical evidence in the travel agency sector. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 410–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Su, X.; Li, L. The indirect effects of destination image on destination loyalty intention through tourist satisfaction and perceived value: The bootstrap approach. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2013, 30, 386–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, D.; Cho, H.; Woosnam, K.M. Exploring tourists’ perceptions of tourism impacts. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2019, 31, 231–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilgihan, A.; Smith, S.; Ricci, P.; Bujisic, M. Hotel guest preferences of in-room technology amenities. J. Hosp. Tour. Technol. 2016, 7, 118–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Qiu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, Q. Impact of comprehensive distance on inbound tourist satisfaction. Tour. Rev. 2022, 77, 1418–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasci, A.D.; Boylu, Y. Cultural comparison of tourists’ safety perception in relation to trip satisfaction. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2010, 12, 179–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladeira, W.J.; Santini, F.D.O.; Araujo, C.F.; Sampaio, C.H. A meta-analysis of the antecedents and consequences of satisfaction in tourism and hospitality. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2016, 25, 975–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.B. Perceptions of tourism products. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 607–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, A.M.; Parsa, H.G. Kano’s model: An integrative review of theory and applications to the field of hospitality and tourism. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2013, 22, 25–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, A.; Sahu, R.; Joshi, Y. Kano model application in the tourism industry: A systematic literature review. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2022, 23, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, K.C.; Chen, M.C. Applying the Kano model and QFD to explore customers’ brand contacts in the hotel business: A study of a hot spring hotel. Total Qual. Manag. 2011, 22, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Bitaab, M.; Lee, M.; Back, K.J. The two sides of hotel green practices in customer experience: An integrated approach of the Kano model and business analytics. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2024, 41, 659–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Lee, M.; Back, K.J. Exploring the roles of hotel wellness attributes in customer satisfaction and dissatisfaction: Application of Kano model through mixed methods. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 33, 263–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.T.; Chen, B.T. Integrating Kano model and SIPA grid to identify key service attributes of fast food restaurants. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2015, 16, 141–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pai, F.Y.; Yeh, T.M.; Tang, C.Y. Classifying restaurant service quality attributes by using Kano model and IPA approach. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 2018, 29, 301–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.H.; Weng, S.J.; Lin, Y.T.; Kim, S.H.; Gotcher, D. Investigating the importance and cognitive satisfaction attributes of service quality in restaurant business—A case study of TASTy steakhouse in Taiwan. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2020, 23, 263–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, B.L.; Goh, B.; Huffman, L.; Jai, C.; Karim, S. Cruise passengers’ perception of key quality attributes of cruise lines in North America. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2016, 25, 346–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.S.; Choi, Y.; Chiang, C.H. Exploring the dynamic effect of multi-quality attributes on overall satisfaction: The case of incentive events. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 64, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meeprom, S.; Fakfare, P. Blended learning: Examining must-have, hybrid, and value-added quality attributes of hospitality and tourism education. J. Hosp. Tour. Educ. 2024, 36, 281–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golmohammadi, A.; Shams Ghareneh, N.; Keramati, A.; Jahandideh, B. Importance analysis of travel attributes using a rough set-based neural network: The case of Iranian tourism industry. J. Hosp. Tour. Technol. 2011, 2, 155–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominici, G.; Palumbo, F. The drivers of customer satisfaction in the hospitality industry: Applying the Kano model to Sicilian hotels. Int. J. Leis. Tour. Mark. 2013, 3, 215–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, W.; Lee, M.; Bowen, J.T. Exploring customers’ luxury consumption in restaurants: A combined method of topic modeling and three-factor theory. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2022, 63, 66–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velikova, N.; Slevitch, L.; Mathe-Soulek, K. Application of Kano model to identification of wine festival satisfaction drivers. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 29, 2708–2726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotiadis, A.K.; Vassiliadis, C.A. Service quality at theme parks. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2016, 17, 178–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Lee, J.S.; Nicolau, J.L. Understanding the dynamics of the quality of airline service attributes: Satisfiers and dissatisfiers. Tour. Manag. 2020, 81, 104163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikulić, J.; Prebežac, D. A critical review of techniques for classifying quality attributes in the Kano model. Manag. Serv. Qual. Int. J. 2011, 21, 46–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artetxe, M.; Schwenk, H. Massively multilingual sentence embeddings for zero-shot cross-lingual transfer and beyond. Trans. Assoc. Comput. Linguist. 2019, 7, 597–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blei, D.M.; Ng, A.Y.; Jordan, M.I. Latent dirichlet allocation. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2003, 3, 993–1022. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, M.E.; Stewart, B.M.; Tingley, D. Stm: An R package for structural topic models. J. Stat. Softw. 2019, 91, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, H. Clustering and topic modeling of phishing texts: A multi-visualization approach. TechRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egger, R.; Yu, J. A topic modeling comparison between lda, nmf, top2vec, and bertopic to demystify twitter posts. Front. Sociol. 2022, 7, 886498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egger, R. Topic modelling: Modelling hidden semantic structures in textual data. In Applied Data Science in Tourism: Interdisciplinary Approaches, Methodologies, and Applications; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 375–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, P.; Mandal, S.; Nedungadi, P.; Raman, R. Unveiling sustainable tourism themes with machine learning based topic modeling. Discov. Sustain. 2025, 6, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirilenko, A.P.; Stepchenkova, S. Facilitating Topic Modeling in Tourism Research: Comprehensive Comparison of New AI Technologies. Tour. Manag. 2025, 106, 105007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Moon, J.; Kim, S.; Cho, W.I.; Han, J.; Park, J.; Song, C.; Kim, J.; Song, Y.; Oh, T.; et al. Klue: Korean language understanding evaluation. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2105.09680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grootendorst, M. BERTopic: Neural topic modeling with a class-based TF-IDF procedure. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2203.05794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, A.K. Data clustering: 50 years beyond K-means. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2010, 31, 651–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Wunsch, D. Survey of clustering algorithms. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. 2005, 16, 645–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, W.; Cho, K. Deep Learning and NLP-Based Trend Analysis in Actuators and Power Electronics. Actuators 2025, 14, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikotun, A.M.; Habyarimana, F.; Ezugwu, A.E. Cluster validity indices for automatic clustering: A comprehensive review. Heliyon 2025, 11, e41953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, B.; Ryu, S.; Kim, Y.; Kim, D. Analysis on review data of restaurants in Google Maps through text mining: Focusing on sentiment analysis. J. Multimed. Inf. Syst. 2022, 9, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schützenmeister, A.; Jensen, U.; Piepho, H.P. Checking normality and homoscedasticity in the general linear model using diagnostic plots. Commun. Stat.-Simul. Comput. 2012, 41, 141–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slevitch, L. Kano model categorization methods: Typology and systematic critical overview for hospitality and tourism academics and practitioners. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2025, 49, 449–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, S.; Hwang, Y.; Kim, T. Attributes of satisfaction and dissatisfaction with online travel experiences in peer-to-peer platforms. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2025, 124, 103972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brida, J.G.; Pulina, M.; Riaño, E.M.M. Measuring visitor experiences at a modern art museum and linkages to the destination community. J. Herit. Tour. 2012, 7, 285–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, D.; Doucé, L.; Nys, K. Immersive Art Exhibitions: Sensory Intensity Effects on Visitor Satisfaction via Visitor Attention and Visitor Experience. Visit. Stud. 2025, 28, 272–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotter, K.N.; Crone, D.L.; Rodriguez-Boerwinkle, R.M.; Boerwinkle, M.; Silvia, P.J.; Pawelski, J.O. Examining the flourishing impacts of repeated visits to a virtual art museum and the role of immersion. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortensen, M.F. Designing immersion exhibits as border-crossing environments. Museum Manag. Curatorship 2010, 25, 323–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annechini, C.; Menardo, E.; Hall, R.; Pasini, M. Aesthetic attributes of museum environmental experience: A pilot study with children as visitors. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 508300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Ito, H. Visitor’s experience evaluation of applied projection mapping technology at cultural heritage and tourism sites: The case of China Tangcheng. Herit. Sci. 2023, 11, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Sutunyarak, C. The impact of immersive technology in museums on visitors’ behavioral intention. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Topic | Count | Topic Title | Description | Representative Keywords |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 321 | Digital Art & Photo Spot | Immersive visual space ideal for appreciation and photo-taking experiences | beauty, art, immersive, photo, view |

| 2 | 101 | Emotional Healing & Immersive Experience | Perceived as a space for emotional healing through immersive art | fantastic, experience, healing, mood, immersive |

| 3 | 51 | Mixed Perceptions on Admission Fee & Value | Opinions divided on cost-effectiveness and price satisfaction | admission, price, worth, souvenir, recommend |

| 4 | 51 | Indoor Option for Rainy Days | Recognized as a good indoor option during inclement weather | rain, indoor, weather, visit, queue |

| 5 | 49 | Family- and Kid-Friendly Space | Highly suitable for families and children, often praised for enjoyment | child, family, visit, trip, pretty |

| 6 | 46 | Worth Visiting Once | Generally positive with mixed opinions about repeat visits | worth visiting, once, visual, recommend, meh |

| 7 | 30 | Must-Visit for Jeju Tourists | Evaluated as a must-see tourist spot in Jeju, with some disagreement | Jeju, must-go, travel, tourist, recommend |

| 8 | 17 | Weather-Proof Healing Space | Comfortable indoor environment regardless of weather | coolness, healing, indoor, weather, cozy |

| −1, 9 | 113 | Noise Topics | Noises and insufficient thematic coherence topics | good, nice, recommended |

| Cluster | Count | Topic Title | Description | Representative Keywords |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 320 | Emotional Immersion & Healing | Deep emotional connection, calm atmosphere, and sensory immersion | healing, calm, immersive, waterfall, wave |

| 2 | 179 | Mixed Sentiments | Emotionally mixed or underwhelmed reactions | so-so, not impressed, expected more |

| 3 | 126 | Practical Visits & Unexpected Delight | Visits driven by weather or practicality, but surprisingly satisfying | rain, cool air, photos, escape weather |

| 4 | 41 | General Positivity | Brief positive reactions with little detail | good, nice, liked, famous paintings |

| Variable | Mean | Standard Deviation | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rating | 4.4185 | 0.9483 | 1 | 5 |

| Topic mention (Group 1) | 0.3050 | 0.3424 | 0 | 1 |

| Topic mention (Group 2) | 0.1499 | 0.2430 | 0 | 1 |

| Topic mention (Group 3) | 0.0493 | 0.1437 | 0 | 1 |

| Topic mention (Group 4) | 0.0583 | 0.1806 | 0 | 1 |

| Topic mention (Group 5) | 0.0507 | 0.1454 | 0 | 1 |

| Topic mention (Group 6) | 0.0456 | 0.1301 | 0 | 1 |

| Topic mention (Group 7) | 0.0473 | 0.1566 | 0 | 1 |

| Topic mention (Group 8) | 0.0434 | 0.1241 | 0 | 1 |

| DV | Topic 1 | DV | Topic 2 | DV | Topic 3 | DV | Topic 4 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IVs | IVs | IVs | IVs | ||||||||

| Rating | 0.007 (0.055) | Rating | 0.023 b (0.007) | Rating | −0.022 c (0.005) | Rating | −0.001 (0.006) | ||||

| Topic 2 | −0.764 c (0.038) | Topic 1 | −0.449 c (0.022) | Topic 1 | −0.198 c (0.018) | Topic 1 | −0.291 c (0.021) | ||||

| Topic 3 | −0.706 c (0.063) | Topic 3 | −0.457 c (0.050) | Topic 2 | −0.218 c (0.024) | Topic 2 | −0.333 c (0.028) | ||||

| Topic 4 | −0.700 c (0.050) | Topic 4 | −0.470 c (0.040) | Topic 4 | −0.213 c (0.029) | Topic 3 | −0.316 c (0.042) | ||||

| Topic 5 | −0.749 c (0.061) | Topic 5 | −0.490 c (0.048) | Topic 5 | −0.224 c (0.035) | Topic 5 | −0.324 c (0.041) | ||||

| Topic 6 | −0.774 c (0.068) | Topic 6 | −0.471 c (0.054) | Topic 6 | −0.227 c (0.038) | Topic 6 | −0.342 c (0.046) | ||||

| Topic 7 | −0.691 c (0.057) | Topic 7 | −0.478 c (0.045) | Topic 7 | −0.213 c (0.032) | Topic 7 | −0.302 c (0.039) | ||||

| Topic 8 | −0.746 c (0.072) | Topic 8 | −0.508 c (0.056) | Topic 8 | −0.219 c (0.040) | Topic 8 | −0.313 c (0.048) | ||||

| Constant | 0.602 c (0.044) | Constant | 0.324 c (0.036) | Constant | 0.249 c (0.050) | Constant | 0.275 c (0.030) | ||||

| R2 (Adjusted) | 0.499 (0.494) | R2 (Adjusted) | 0.416 (0.410) | R2 (Adjusted) | 0.292 (0.024) | R2 (Adjusted) | 0.251 (0.243) | ||||

| F | 95.936 c (9, 769) | F | 68.479 c (9, 769) | F | 24.465 c (9, 769) | F | 32.191 c (9, 769) | ||||

| DV | Topic 5 | DV | Topic 6 | DV | Topic 7 | DV | Topic 8 | ||||

| IVs | IVs | IVs | IVs | ||||||||

| Rating | 0.002 (0.005) | Rating | 0.000 (0.005) | Rating | 0.001 (0.005) | Rating | 0.003 (0.004) | ||||

| Topic 1 | −0.217 c (0.018) | Topic 1 | −0.185 c (0.016) | Topic 1 | −0.230 c (0.019) | Topic 1 | −0.166 c (0.016) | ||||

| Topic 2 | −0.241 c (0.024) | Topic 2 | −0.192 c (0.022) | Topic 2 | −0.271 c (0.025) | Topic 2 | −0.192 c (0.021) | ||||

| Topic 3 | −0.231 c (0.036) | Topic 3 | −0.194 c (0.033) | Topic 3 | −0.253 c (0.038) | Topic 3 | −0.174 c (0.031) | ||||

| Topic 4 | −0.225 c (0.029) | Topic 4 | −0.196 c (0.027) | Topic 4 | −0.242 c (0.031) | Topic 4 | −0.167 c (0.026) | ||||

| Topic 6 | −0.241 c (0.039) | Topic 5 | −0.199 c (0.032) | Topic 5 | −0.267 c (0.038) | Topic 5 | −0.174 c (0.031) | ||||

| Topic 7 | −0.232 c (0.033) | Topic 7 | −0.199 c (0.030) | Topic 6 | −0.277 c (0.041) | Topic 6 | −0.191 c (0.034) | ||||

| Topic 8 | −0.227 c (0.040) | Topic 8 | −0.205 c (0.037) | Topic 8 | −0.268 c (0.043) | Topic 7 | −0.179 c (0.029) | ||||

| Constant | 0.199 a (0.026) | Constant | 0.181 c (0.023) | Constant | 0.216 c (0.027) | Constant | 0.156 c (0.023) | ||||

| R2 (Adjusted) | 0.196 (0.188) | R2 (Adjusted) | 0.171 (0.162) | R2 (Adjusted) | 0.203 (0.195) | R2 (Adjusted) | 0.153 (0.144) | ||||

| F | 23.496 c (9, 769) | F | 17.798 c (9, 769) | F | 24.553 c (9, 769) | F | 17.328 c (9, 769) | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Shin, S.; Ko, S.-B.; Kang, J. Sustainable Tourist Satisfaction in Art Museums: Identifying Attributes That Enhance Visitor Experience for Sustainable Cultural Management. Sustainability 2026, 18, 1367. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18031367

Shin S, Ko S-B, Kang J. Sustainable Tourist Satisfaction in Art Museums: Identifying Attributes That Enhance Visitor Experience for Sustainable Cultural Management. Sustainability. 2026; 18(3):1367. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18031367

Chicago/Turabian StyleShin, Seunghun, Seong-Bin Ko, and Juhyun Kang. 2026. "Sustainable Tourist Satisfaction in Art Museums: Identifying Attributes That Enhance Visitor Experience for Sustainable Cultural Management" Sustainability 18, no. 3: 1367. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18031367

APA StyleShin, S., Ko, S.-B., & Kang, J. (2026). Sustainable Tourist Satisfaction in Art Museums: Identifying Attributes That Enhance Visitor Experience for Sustainable Cultural Management. Sustainability, 18(3), 1367. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18031367