1. Introduction

Formative or subtractive methods have been traditionally used to manufacture metal parts [

1]. Examples of formative manufacturing processes are metal casting, forging, rolling, and extrusion. During formative manufacturing, the part’s geometry is achieved by either molding molten metal or plastically deforming it from its solid state. By contrast, subtractive manufacturing involves gradually removing material from a workpiece until the final part is completed. Additive manufacturing (AM), also known as 3D printing, has evolved since the 1980s, when it was first introduced as a method for producing prototypes, to become a highly viable manufacturing method [

2]. During the AM process, materials are joined to make objects from computer models, usually layer by layer [

3]. AM has a distinct advantage over both formative and subtractive manufacturing, as it can create highly complex, custom geometries without waste. However, AM is not without challenges, including limited material selection, part size, final properties, and unit costs compared to more traditional, higher-volume production methods. Therefore, currently, AM is advancing niche applications that leverage the technology to meet customer requirements. For example, the aviation industry is advancing the use of metal AM to produce jet engine parts that are less expensive, lighter, and more intricate, while still maintaining the material properties and performance of parts made via formative manufacturing or subtractive manufacturing [

4].

In addition to the potential to reduce lead times, material waste, and inventory costs, AM opens design options for geometries that are difficult to produce by conventional means. Some authors indicate that AM can reduce material waste by up to 90% when compared to subtractive manufacturing processes [

5]. Reducing material use and waste also lowers the associated transportation costs. In some applications, AM requires less tooling and fixtures than metal casting and forging, further reducing material usage, inventory, and transportation costs while decreasing the amount of raw materials needed across the supply chain. As a process, AM uses less energy and emits fewer pollutants than formative manufacturing or subtractive manufacturing [

6].

To leverage the advantages that AM offers while also achieving advanced material properties, parts must have nearly, if not the same, characteristics as those manufactured by incumbent formative and subtractive manufacturing processes used for critical applications. Ultimately, this requires almost 100% density, consistent and controlled microstructures, repeatable dimensional accuracy, and smooth surface finishes in the final products. Powder bed fusion, binder jetting, material jetting, and directed energy deposition are the primary powder-based AM processes used to produce metal parts [

7].

One specific area of growth within AM is the development of high-conductivity components to support the future demand of next-generation power electronics, electric vehicles, renewable energy, high-frequency radio frequency, and quantum computing [

8]. AM is well-suited for these thermal management applications due to its ability to meet increasingly more demanding geometrical and dimensional tolerance requirements [

9]. Among other materials, high-purity copper is required as a raw material in these applications due to its excellent chemical, thermal, and electrical properties. By reducing the presence of trace elements and impurities (e.g., oxygen, sulfur, iron, zinc, lead), the stability of mechanical, thermal, and chemical properties is enhanced [

10].

Table 1 illustrates representative applications for high-purity copper, the material’s advantages, and the benefits of additive manufacturing for these products.

Oxygen-free high-conductivity (OFHC) copper is defined as having a maximum of 10 ppm oxygen, compared to high-purity copper, which typically allows for up to 400 ppm [

11]. Lower oxygen levels in OFHC copper result in an electrical conductivity ≥ 101% IACS (International Annealed Copper Standard), compared with high-purity copper, which has an electrical conductivity of 99–100% IACS. The enhanced electrical conductivity of OFHC copper makes it an ideal candidate for critical applications that demand high electrical performance. However, maintaining low oxygen levels poses challenges for manufacturing the metal powder (see

Section 2) and for AM. Laser powder bed fusion (LPBF) is considered the most promising AM method for producing complex parts from OFHC copper due to its high precision, localized melting capability, and compatibility with fine metal powders [

12]. However, copper, particularly OFHC copper, poses unique challenges for LPBF due to its high reflectivity and thermal conductivity.

In addition to the inherent material property challenges posed by OFHC copper in LPBF, the physical characteristics of the powder particles also play a vital role [

13]. In general, metal powders are characterized by particle microstructure, particle size distribution (PSD), surface morphology, and purity. Traditionally, metal powders are made using various methods to tailor their properties for end applications. Examples of metal powder manufacturing methods suited for AM include gas atomization, plasma atomization, plasma rotating electrode process, water atomization, and centrifugal atomization [

14]. While plasma atomization and the plasma rotating electrode process offer the highest purity and near-perfect spheres required for high-end applications, their yields are comparatively low, and operating costs are high [

15]. Similarly, centrifugal atomization produces high-purity spherical particles; however, achieving high throughput and controlling particle size remain challenges [

16]. Water atomization is more cost-effective but produces powders with higher levels of oxidation and irregular shapes, making it less suitable for applications that require higher purity and the processing characteristics of LPBF [

17]. Powders produced via gas atomization have an optimal balance of purity, spheroidal particle shape, and industrial scalability, making the process an ideal candidate for OFHC copper AM applications, particularly LPBF [

18]. According to publicly available market research reports, gas-atomized powders account for more than 40% of the overall metal powder market, which includes products made via hot isostatic pressing, metal injection molding, cold spray deposition, press-and-sinter, and AM [

19,

20].

Gas atomization of high-purity metals such as OFHC copper can be performed using either vacuum induction melting gas atomization (VIGA) or electrode induction melting gas atomization (EIGA). In the VIGA process, a solid metal feedstock is melted in a crucible under vacuum and an inert gas, and then atomized using high-velocity inert-gas jets. While VIGA is versatile and widely used, it involves direct contact between the molten metal and the crucible, which introduces a risk of contamination, which can be particularly problematic for materials that require high levels of purity, such as OFHC copper [

21]. Alternatively, EIGA is a crucible-free process in which a consumable electrode is induction-melted in a controlled inert atmosphere, and the molten stream is directly atomized. Producing powders via EIGA eliminates the potential for contamination from crucible materials. It produces highly spherical powders with superior chemical purity and surface cleanliness [

22,

23]. As a result, EIGA is preferred over vacuum induction melting gas atomization for OFHC copper applications that require high levels of material purity, conductivity, and oxidation resistance [

24]. Thus, EIGA is the gas atomization method used in this comparative study.

While EIGA is widely accepted for metal powder manufacturing, it poses challenges and potential risks when assessing the compatibility of the resulting powders with LPBF [

12]. Even when ultra-high-purity gases (e.g., argon) are used during post-processing, some oxygen may remain, leading to surface oxidation, reduced conductivity, and reduced fusion quality during LPBF. Furthermore, during atomization, molten metal droplets can attach themselves to larger droplets and form satellites, which affect particle flow and, in turn, lead to asymmetrical layers in the powder bed, thereby increasing surface roughness. EIGA also results in a broad PSD (typically from <10 to 500 μm [

14]), which necessitates post-atomization screening and classification processes to achieve the preferred range of uniform particle size (nominally in the ranges of 10 to 45 μm, 15 to 53 μm, or 20 to 60 μm), ensuring more efficient laser absorption and melt pool stability for LPBF, thereby leading to lower powder yields (20 to 50%) and further increasing costs [

25].

AM offers several sustainability advantages over formative and subtractive manufacturing. Its near-net-shape production significantly reduces scrap and material loss compared to traditional manufacturing [

26]. This advantage is particularly impactful for applications that utilize expensive materials, such as OFHC copper. Moreover, AM and LPBF offer a lower risk of contamination, thereby enabling greater powder reuse and recycling. Thus, it lowers the demand for feedstock materials. Both EIGA and LPBF are energy-intensive applications. However, more sustainable alternatives to EIGA may further reduce overall energy use throughout the AM lifecycle. One such alternative is the Metal Powder Works (MPW) DirectPowder

TM process.

The DirectPowderTM System offers several advantages over EIGA. Because it is a room-temperature, solid-state process, it consumes less energy and yields fully dense particles. Further, particles do not contain satellites or fine particles, which promotes consistent particle flow during LPBF, resulting in smoother surface finishes and reduced energy consumption. The highly controllable process enables designers to tune to a desired PSD, yielding as much as 99% usable powder product and requiring far less, if any, post-processing, such as screening or sieving, unlike EIGA. All these advantages make the DirectPowderTM method a viable candidate for substantially reducing the environmental impact of the OFHC copper AM supply chain while also providing material processing and property improvements.

This study presents an energy-based, limited-scope global warming potential (GWP) life cycle assessment (LCA) that compares two powder production routes for OFHC copper, gas atomization, and the DirectPowder

TM process, and their downstream use in LPBF. The analysis quantifies emissions in terms of CO

2 Equivalents (CO

2-eq) resulting solely from energy consumption during powder manufacturing and part production, which account for the combined climate impacts of CO

2, CH

4, and N

2O based on their GWPs over a 100-year time horizon. This narrower focus was adopted to enable streamlined comparison where data availability and industrial relevance are most robust. The approach aligns with established ISO 14040/14044 [

27,

28] LCA principles and provides actionable insights into CO

2-eq emissions of emerging manufacturing pathways for OFHC copper components. This energy-based LCA did not include a detailed cost analysis, which is recommended as an area of future research, as evaluating cost-sustainability tradeoffs will be essential for industrial adoption and for better contextualizing the results for supply chain stakeholders. The limitations of this scope are acknowledged and discussed, and the study aims to serve as a foundational step toward more comprehensive sustainability assessments.

The decision to focus solely on energy-derived greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions reflects both the availability of robust inventory data and the primary environmental concern in metal powder production: its high energy intensity and associated impacts. This limited-scope approach is commonly used in early-stage comparative assessments to identify carbon hotspots, support process selection, and screen emerging technologies such as MPW’s DirectPowder

TM System. To account for uncertainty in input data, a Monte Carlo simulation was used to provide a more robust understanding of the LCA results. This approach enables manufacturers, policymakers, and designers to make better-informed decisions regarding process selection. Moreover, it serves as a foundation for future research. The processes that are the focus of this study—EIGA, DirectPowder

TM, and LPBF—are discussed in greater detail in

Section 2. The LCA methodology used is outlined in

Section 3, and the results are presented and discussed in

Section 4. Finally,

Section 5 outlines the conclusions, limitations, and opportunities for future research.

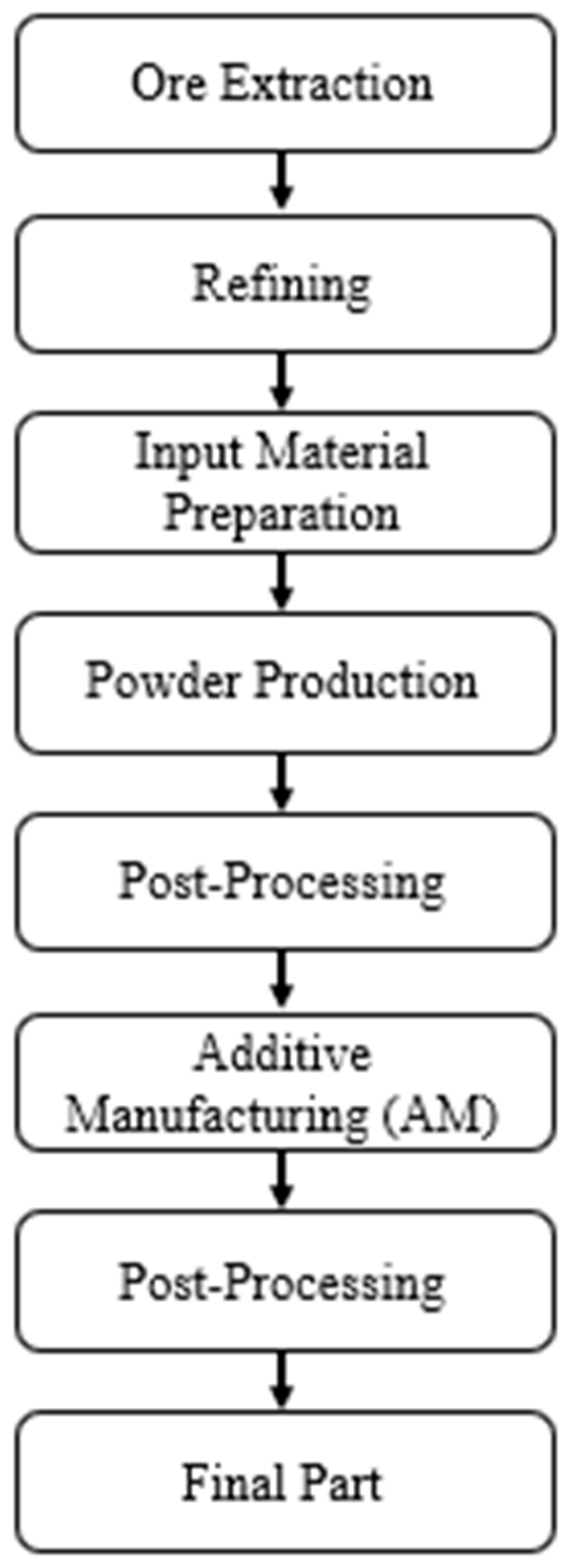

2. Metal Powder Additive Manufacturing Processes

The process of manufacturing components via metal powder AM begins by extracting natural ore deposits from the earth. Next, metallurgical refining processes (e.g., smelting, electrorefining, crushing, grinding, and flotation) are used in combination to obtain the desired base metals (e.g., iron, nickel, copper, and chromium) from the mined ore. Subsequently, the base metal is refined to achieve the desired purity. Depending on the intended powder production process (e.g., VIGA, water atomization, EIGA), the base metal will be formed into ingots, bar stock, metal rods, wire, or other forms. During powder production, base metals are melted and converted into metal powder via atomization, melt spinning, rotating electrode, mechanical, or chemical methods. Depending on the powder production process used, the resulting metal powders will exhibit a range of particle sizes, shapes, surface chemistries, and surface morphologies. As a result, for most processes, the metal powder will require post-processing steps to achieve the desired characteristics necessary for the intended AM process. Metal powder post-processing may include deoxidation, drying, particle-size classification (e.g., sieving/screening), and blending (e.g., homogenization). After packaging to maintain surface chemistries and prevent contamination, parts are formed from inventoried powders via AM. Once the parts are completed, post-processing and finishing operations (e.g., heat treatment, final machining, surface treatments) are needed to remove any necessary support structures and meet the functional specifications.

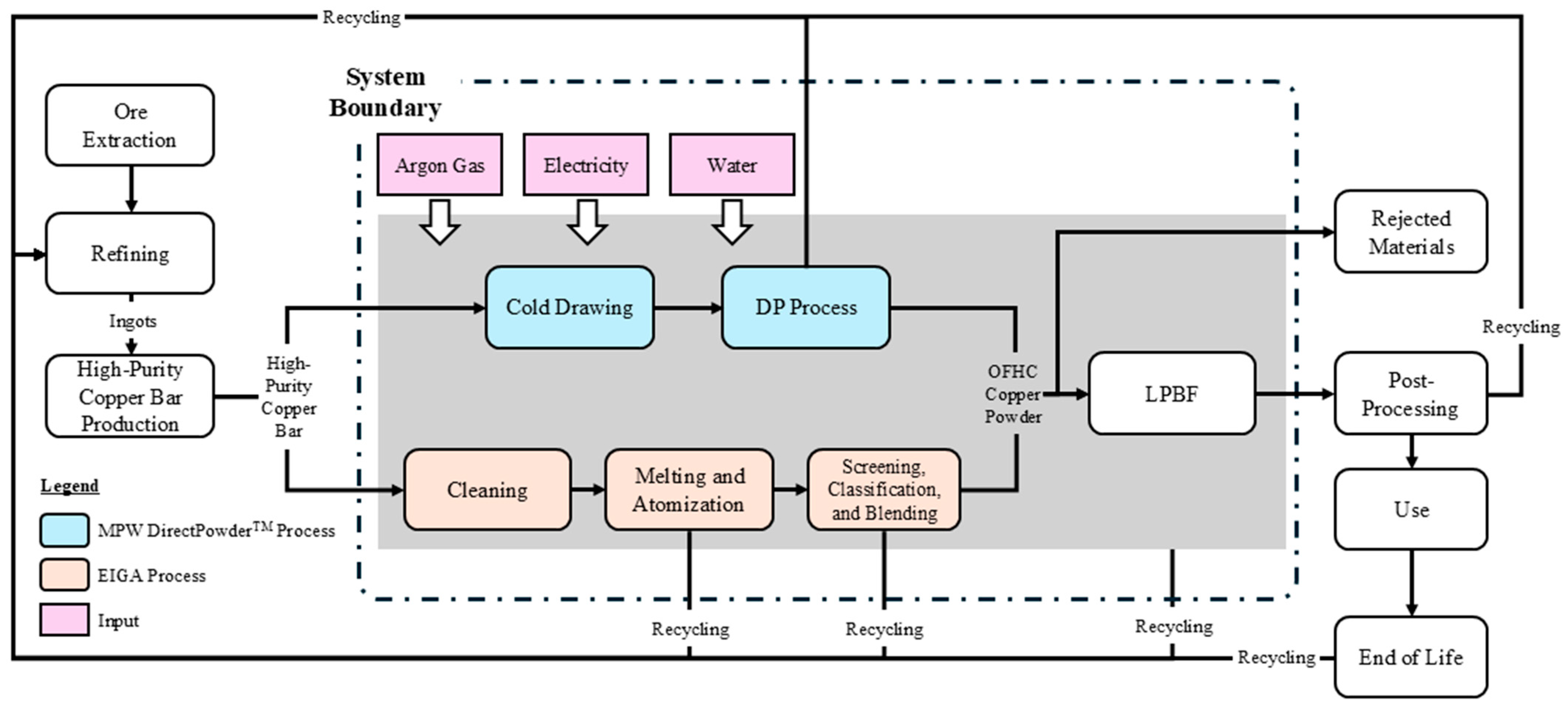

Figure 1 summarizes the overall process to convert metal ore into finished AM parts.

The supply chain used to accomplish the processes outlined in

Figure 1 can be quite complex. Few, if any, AM firms are fully vertically integrated; therefore, significant transportation and material storage occur between processing steps. In addition, substantial amounts of processed gases, chemical agents, and energy are used, which can significantly impact the environment.

The following subsections outline details related to the processes that are the subject of this research: EIGA, DirectPowderTM, and LPBF. In general, ore extraction, refining, and input material preparation are the same for each of the powder production processes. However, the input material for the DirectPowderTM method requires some preparation via cold-working, and post-processing steps are necessary for EIGA in preparing OFHC copper powders for LPBF.

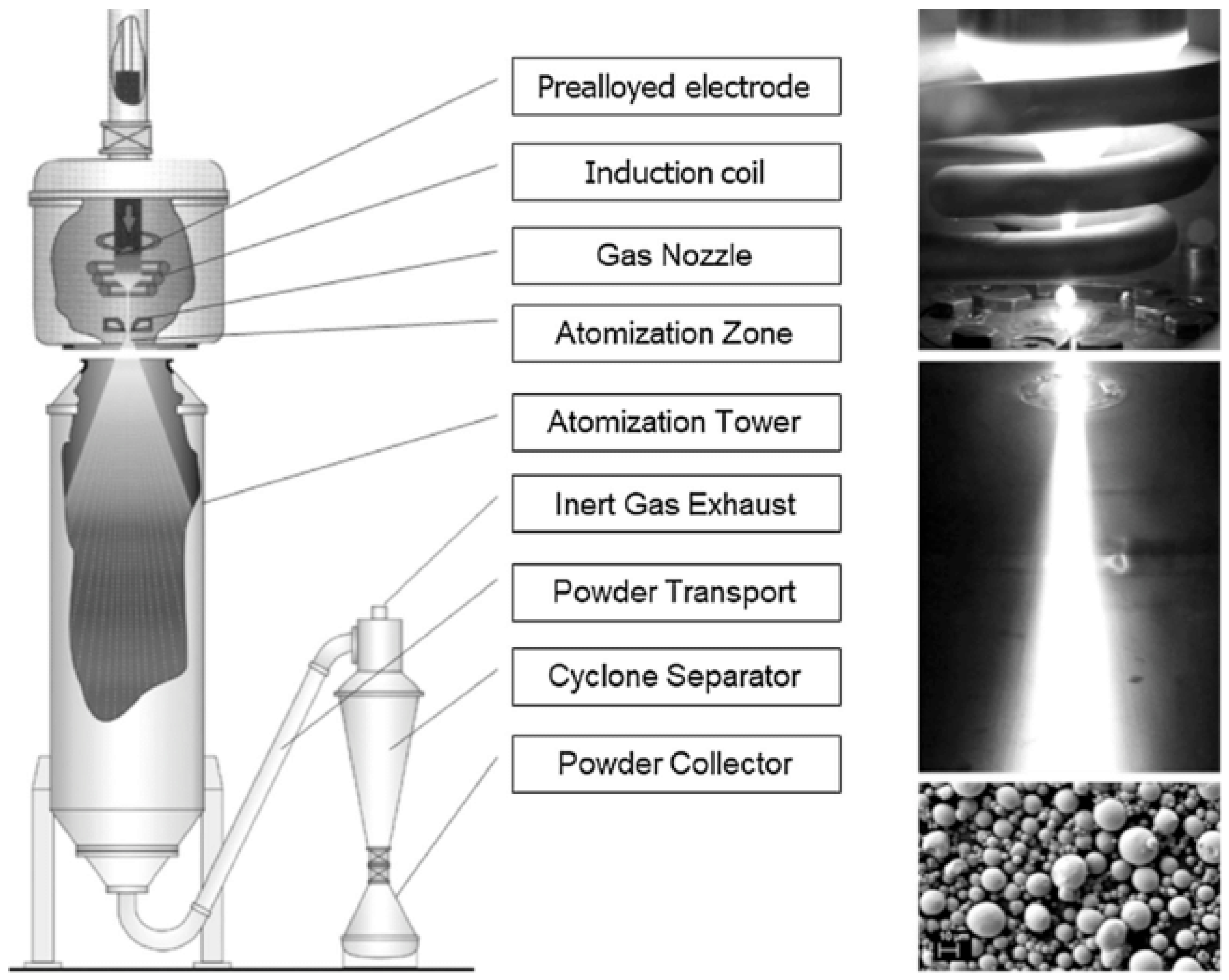

2.1. Electrode Induction Melting Gas Atomization

The EIGA process begins with a pure elemental metal or alloyed metal bar, the electrode. The electrode is a solid, consumable, cylindrical rod made from OFHC copper. After the electrode is cleaned to remove surface impurities, it is fed vertically into an induction coil, where localized heating melts the electrode tip. During the melting stage, the induction coil heats the electrode, creating a continuous, controlled molten flow at its lower end [

29]. Heating is achieved by the electrical eddy current induced in the high-frequency coil.

Figure 2 illustrates the EIGA process.

The molten metal is subjected to high-pressure gas jets, which fragment it into fine droplets [

22,

24]. The droplets rapidly cool and solidify as they fall within a controlled atomization chamber or tower. At the bottom of the atomization chamber, the solidified particles accumulate. Once all the feedstock has been converted to metal powder, the cooled metal particles are sieved (i.e., screened) or air-classified to separate the desired particle size ranges from the undesired ones. The EIGA process operates in a fully inert atmosphere, most commonly high-purity argon (>99.999%), to minimize oxygen content, improve particle surface cleanliness, and control chemistry. Additional post-processing is also performed to improve the powders’ stability, which may include passivation, deoxidation, or blending. Finally, powders meeting the applicable specifications are stored in inventory to prevent oxidation and contamination until they are ready for their intended applications. Powders that fall outside the desired PSD may be recycled and used as input materials for future melt campaigns, if specifications permit.

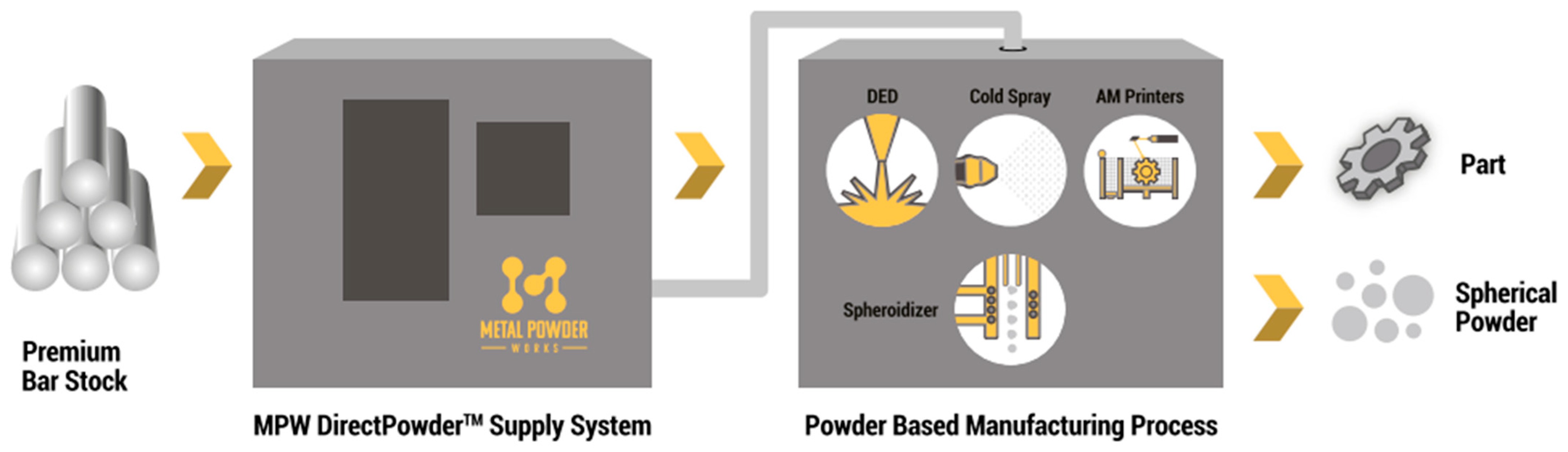

2.2. DirectPowderTM System

The DirectPowder

TM System, developed by MPW, is a patented process for converting ductile materials, such as copper, from bar stock materials into custom PSD [

31]. To initiate the process, an operator enters parameters for the manufactured powder, including the desired PSD. The bar stock material is then inserted into the DirectPowder

TM Supply System and converted into metal powder at room temperature via a cutter mechanism, without the need for melting [

32]. During the process, the feedstock is advanced and cut until the desired quantity of powder is produced. Parameters are adjusted to produce metal particles with a narrow size range, typically 20 to 63 μm, meeting the requirements of many powder metallurgy applications. Throughout the process, powder is collected via a powder collection system and packaged directly from the unit. Overall, the conversion yield from bar stock material to final metal powder exceeds 75%, with greater than 95% of the powder manufactured being usable. After the powder is manufactured, it can be transferred directly to secondary processing, such as LPBF, using the MPW Sidecar concept (see

Figure 3). Thus, eliminating the need for additional handling. Using the Sidecar, additional improvements can be achieved beyond AM part production, including enhanced safety, reduced energy consumption, and improved overall supply chain management [

33]. With this option, firms can manufacture high-quality, custom powders on demand, onsite, and convert them directly into finished AM products, thus reducing the additional transportation and storage that impact the environment and costs, and subject powders, such as OFHC copper, to contamination and oxygen absorption risks.

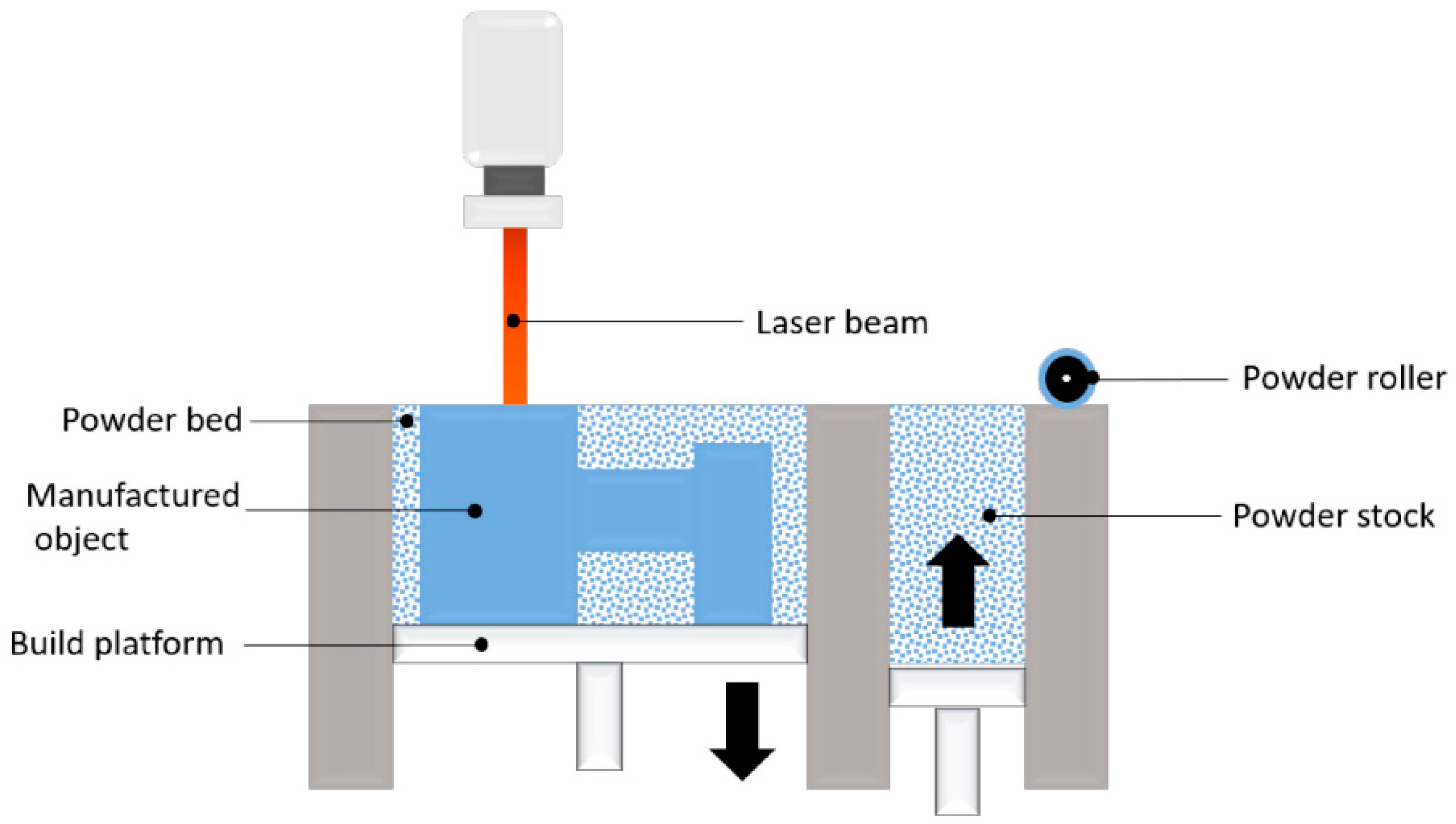

2.3. Laser Powder Bed Fusion

During LPBF, a high-energy laser selectively melts metal powder layer by layer to create solid metal parts. A broad range of metals can be processed using LPBF, provided the materials are in powder form and can be laser-welded. To initiate the process, material feedstock is loaded into the LPBF system [

34]. A build platform, often made of the same or a similar material as the powder being formed, is placed within the build chamber of the equipment during setup. After sealing the chamber, an inert gas (e.g., argon) is introduced and circulated throughout the production process to prevent oxidation and contamination. Next, the build platform is preheated to minimize thermal gradients and ultimately distortion. The part is then built layer by layer using a roller device that spreads a thin layer of powder on the build platform, followed by the scanning phase, where a laser beam fuses the layers of metal powder. The process continues until the desired part geometry is achieved.

Figure 4 illustrates a schematic of the LPBF manufacturing process.

LPBF has been demonstrated to produce pure copper parts using infrared (λ ≈ 1000 nm) and green (λ ≈ 515 nm) lasers [

25]. At lower wavelengths, laser absorption increases, thereby enhancing melting and being especially relevant for high-reflectivity materials, such as OFHC copper [

36]. Additionally, due to its high thermal conductivity, pure copper typically requires laser power between 400 and 1000 W [

37].

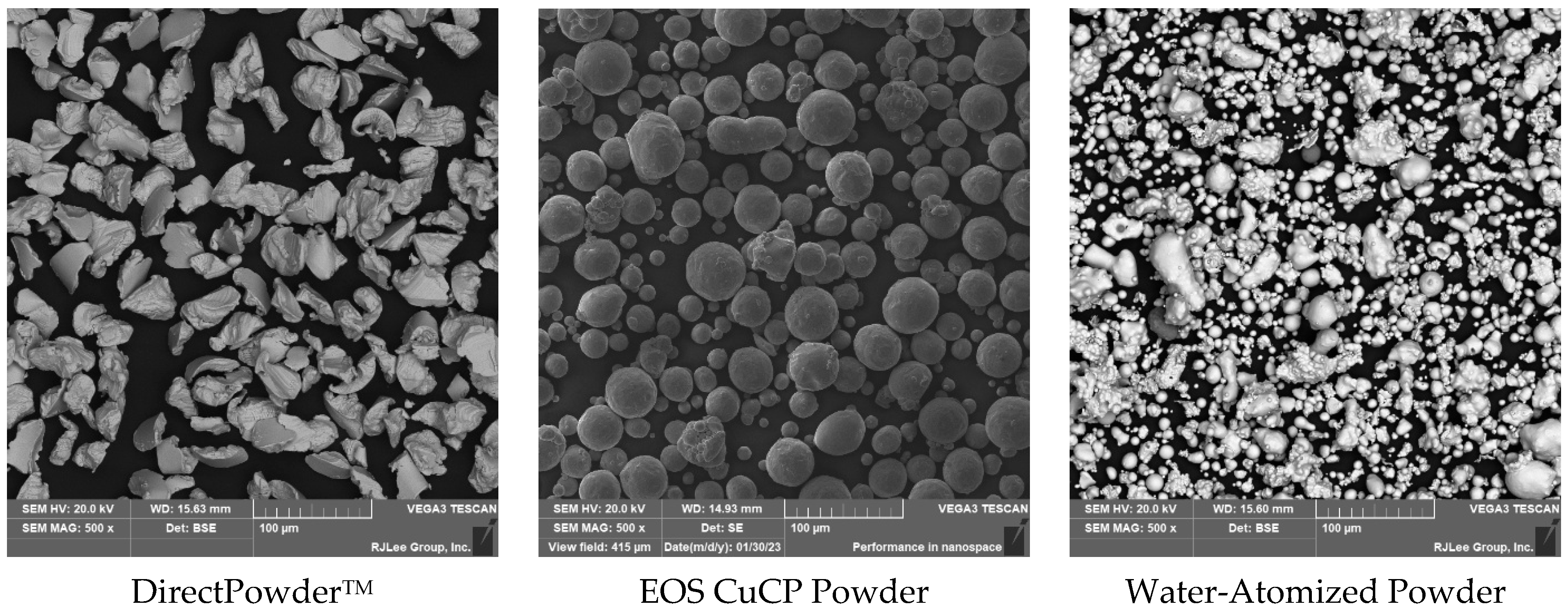

Although powders produced via EIGA exhibit better laser absorption than other techniques, such as plasma atomization, challenges remain in controlling PSD, satellite formation, and shape [

35]. These characteristics result in reduced flow and ultimately poor surface finishes in the final parts, necessitating post-processing to improve the surface finishes. DirectPowder

TM offers a distinct advantage in controlling particle size fractions, surface morphology, and particle shape more effectively than EIGA overall. Thus, DirectPowder

TM is a viable technical alternative to EIGA, eliminating the need for additional operations to meet the surface finish requirements of the manufactured product. Moreover, the use of DirectPowder

TM powders has improved LPBF build times by enabling higher laser absorption and more efficient melting, resulting in thicker layers per pass and ultimately reducing recoat time and increasing energy savings. By further streamlining process steps, DirectPowder

TM can improve energy usage and reduce the environmental impact of the OFHC copper AM supply chain.

3. Life Cycle Assessment

This section outlines the methodology used to assess the environmental implications of two powder production manufacturing methods, EIGA and the DirectPowder

TM process, for OFHC copper, followed by part production via LPBF. The LCA framework follows the ISO 14040 [

27] and 14044 [

28] standards. It is organized into three subsections: Goal and Scope definition, which establishes system boundaries, functional unit, and methodological focus; Lifecycle Inventory, which details the data sources and energy inputs collected or modeled for each process; and Life Cycle Impact Assessment, which quantifies CO

2-eq emissions arising from energy consumption across all modeled lifecycle stages. Given the focus on energy-derived emissions, this LCA represents a limited-scope assessment that emphasizes the GHG emissions of each production route rather than a full multi-factor impact category analysis.

Although AM has a lower environmental impact than traditional and subtractive manufacturing methods, it may still strain the environment. Previous LCA studies on powder metallurgy processes indicate that the atomization stage has the greatest overall impact, accounting for 49% of energy consumption, 55% of GWP, and 64% of waste [

38,

39,

40]. To assess the potential environmental impact of DirectPowder

TM, a system boundary is established to compare the process with EIGA.

3.1. Goal and Scope Definition

The primary goal of this study is to compare the energy-based CO2-eq emissions of two production processes used to manufacture OFHC copper—EIGA and the DirectPowderTM process. Subsequently, the two processes to manufacture parts via LPBF are compared. The assessment aims to quantify and contrast the CO2-eq emissions associated with energy consumption across each manufacturing pathway to inform sustainable materials processing and supply chain decision-making for OFHC copper components.

This study employs a limited-scope, attributional life cycle assessment aligned with ISO 14040 [

27] and 14044 [

28]. The functional unit is defined as 1 kg of OFHC copper final part produced via LPBF from powder generated by either EIGA or the DirectPowder

TM process. System boundaries (see

Figure 5) are set from the point of raw material input through powder production, LPBF part manufacturing, and argon shielding gas use. The upstream mining, downstream finishing, and use phases are excluded. The analysis focuses solely on energy-related emissions and does not account for additional impact categories such as water use, ecotoxicity, or land use. Although not formally incorporated into the system boundary, CO

2-eq transportation emissions are computed to understand the advantages of the DirectPowder

TM process’s Sidecar feature.

Only foreground system processes directly involved in powder and part production are modeled in detail. Background processes, such as electricity generation, are represented using secondary data and standardized emission factors. Recycled materials and byproducts are assumed to fall outside the system boundary, and recycling loops (e.g., reused powder or material remnants) are not credited to the system.

The scope of this LCA is therefore best characterized as a limited, energy-based GWP impact assessment, enabling a targeted evaluation of the CO2-eq emissions of competing powder production technologies and their implications for additive manufacturing supply chains.

3.2. Life Cycle Inventory

The life cycle inventory phase of this study quantifies energy and material inputs. It is based on a combination of primary data from industrial partners, peer-reviewed literature, and secondary data from government and technical databases. Energy values for EIGA and LPBF were adapted from prior studies on comparable metal powders, such as stainless steel and Ti-6Al-4V, and adjusted using material-specific parameters (e.g., absorptivity) where applicable. Due to limited published data on the manufacturing of OFHC copper powder, conservative assumptions and estimates were made and noted. For the DirectPowderTM process, primary data were collected and, where necessary, subsequently modeled. Equipment was not considered because of data availability and long lifespans.

Given the variability and uncertainty in reported energy consumption values, a Monte Carlo simulation was implemented in Analytica (Version 6.6.4.288) to assess variation in the results [

41]. The simulation enabled modeling input parameter uncertainty using defined probability distributions for critical variables and is appropriate in such cases when conducting LCAs [

42]. This approach strengthens the robustness of the LCA results by quantifying how variability in input assumptions propagates through the model. Input parameters were modeled using 10,000 random samples drawn from triangular distributions, which are appropriate for cases with limited data availability and allow reasonable estimates of minimum, midpoint, and maximum values. Where available, data from the cited literature were used for the minimum and maximum input values. When only midpoint values were available, the minimum and maximum values were calculated as midpoint ± 10%.

The foreground data used for the processes within the scope of this study, along with the respective input parameters for the Monte Carlo simulation, are presented in

Table 2 and serve as a basis for subsequent calculations.

Section 3.2.1,

Section 3.2.2 and

Section 3.2.3 explain in greater detail the basis for midpoint values, and

Section 3.3 outlines the use of the Monte Carlo simulation to calculate CO

2-eq emissions using the foreground data. Electricity consumption was converted into CO

2-eq emissions using emission factors from the United States Environmental Protection Agency’s Greenhouse Gas Equivalencies Calculator, assuming an average electricity grid mix [

43]. Energy was reported in kWh per kg of the final part.

Although this limited-scope study focused on energy consumption, the methods were consistent with the foundational ISO standards for LCA. They include ISO 14040:2006 [

27], which describes the principles and framework of LCA, and ISO 14044:2006 [

28], which provides guidelines for conducting LCA assessments. The American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM) has developed globally recognized AM standards for terminology (ISO/ASTM 52900 [

52]) and file formats (ISO/ASTM 52915 [

53]). ISO/ASTM 52910:2018 [

54] provides guidance on incorporating AM into product design to ensure efficient workflows and high-quality products. Moreover, by accounting for AM capabilities in the design phase, the sustainable advantages of the powder manufacturing method can be considered at the early stages of product development. ASTM has also published standards related to process qualification (ISO/ASTM 52949 [

55]) and material data (ISO/ASTM 52929 [

56]). Other local, national, and industry organizations have developed standards in recent years associated with facility safety and measurement science. Examples include Underwriters Laboratories (UL 3400 [

57]) and the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), respectively. The Federal Aviation Administration has issued advisory circulars (AC 33.15-3 [

58]) and handbooks for the use of AM in the aviation industry. ASTM has published several material standards on powder metals, many of which are cited in this paper either directly or by reference.

3.2.1. Electrode Induction Melting Gas Atomization

A high-purity copper bar is assumed to be used as input to both the EIGA and the DirectPowderTM process streams. In both cases, the primary copper feedstock contains ≥99.99% copper and ≤10 ppm oxygen content, with minimal impurities (e.g., sulfur, lead, phosphorus). Therefore, equivalence of the starting materials is assumed, and they are excluded from the system boundary and analysis.

Several manufacturing processes can produce metal powders. These processes include water atomization, gas atomization, and mechanical processes such as ball milling. However, gas atomization is the most widely used method for AM because it produces spherical powders. Furthermore, to control impurities and maintain low oxygen levels during the manufacture of OFHC copper powder, EIGA using argon is the most suitable method.

While several authors have conducted LCA studies on metal powder atomization or incorporated it into larger studies, energy quantification data on EIGA and downstream processes are lacking [

44]. Many studies do not specifically state the scope or system boundaries of the atomization process or disaggregate it into its subprocesses (e.g., melting, atomization, screening, blending), and the reported values vary considerably. Zhang et al. [

59] reported a power consumption of 2.00 kWh·kg

−1 for the manufacture of copper powder via gas atomization. However, they did not specify the gas atomization technique (e.g., VIGA or EIGA). Xiao [

44] reported distinct energy consumption values for cleaning the electrode (EIGA) as well as electricity and argon consumption of downstream processes for both vacuum induction melting gas atomization and EIGA (sieving, air classification, and blending). With respect to EIGA, Xiao [

44] reported 8.25 kWh·kg

−1 of electrical energy consumption and an additional 2.75 kg of argon used during melting to atomize Ti-6Al-4V powder. In total, Spreafico [

46] and Landi et al. [

47] reported energy consumption for EIGA to be 2.12 and 5 kWh·kg

−1, respectively. Both authors cited argon as the process gas and Ti-6Al-4V as the alloy being atomized. While the authors did not specify the processes that the reported values represent, it can be inferred that only the electrode induction melting is included. A sample of atomization energy consumption data from prior studies on various metals produced via different gas and water atomization methods is included in

Appendix A Table A1. In this study, a midpoint estimate of 6.47 kWh·kg

−1 for the electrical power component of the specific energy consumption (

) is used for electrode induction melting based on the closest available data for EIGA of Ti-6Al-4V [

44,

46,

47]. This value is a reasonable best estimate of copper, compared with values reported for other materials and atomization methods, given their similar oxygen affinities, which require similar process controls to maintain low oxygen levels. Prior to melting and atomization, the electrode requires 0.220 kWh·kg

−1 (

) [

44].

Using Equation (1) and the data provided by Xiao [

44], the amount of argon gas used at each stage of the process is converted to the specific energy consumed in generating compressed gas per kg of material produced (

), where the molar mass (

) of argon is 39.95 g·mol

−1,

= mass of argon,

= 8.31 J·(mol·K)

−1, the initial pressure of the gas (

) is 0.1 MPa, the final pressure of the gas (

) is 6.1 MPa,

= 298.15 K, and the adiabatic index (

) is 1.67 [

44,

48]. For the melting and atomization portion of the EIGA processes,

.

Material properties can influence atomization efficiency. One of the primary energy drivers of energy consumption in EIGA is a material’s enthalpy of fusion and melt temperature (

). To account for the differences in using Ti-6Al-4V as a proxy for OFHC copper, Equation (2) was used to estimate the specific energy consumption of OFHC copper, where

.

Once the powder has been atomized, it must be screened and blended to obtain the preferred particle-size fraction for LPBF, yielding

(

) by mass of usable powder [

49]. Xiao [

44] estimates 3.30 kWh·kg

−1 (

) of electrical energy is consumed in air classification, 0.160 3.30 kWh·kg

−1 (

) during screening, and 0.083 kWh·kg

−1 (

) during blending. To maintain the required oxygen levels, 1.65 kg of argon is used as a protective blanket during air classification, 0.400 kg during screening, and 0.280 kg during blending, which, using Equation (1), results in midpoint values of

0.178 kWh·kg

−1,

= 0.043 kWh·kg

−1, and

= 0.030 kWh·kg

−1. The differences between Ti6Al4V and OFHC are assumed to be negligible during power post-processing. Therefore, no further adjustments are made to these values prior to the Monte Carlo simulation that is implemented as part of the life cycle impact assessment.

3.2.2. DirectPowderTM System

The DirectPowder

TM process begins with hard-tempered, oxygen-free copper bar stock (C10100-H04, ASTM B187) having a minimum purity of

. The material has been cold-drawn to increase its hardness and improve machinability. The theoretical drawing power and ultimately the energy consumption of the cold drawing process are functions of both process parameters (drawing speed, friction coefficient of the die, and die compression angle) and material properties (material strength and the initial and final diameters of the material). Due to the lack of publicly available empirical data on the energy consumption of cold drawing OFHC copper, the drawing energy is estimated using publicly available data for steel as a proxy. Suliga et al. [

50] reported that cold drawing low-alloy steel requires approximately 0.35 to 0.60 kWh·kg

−1, depending on die geometry, reduction ratio, and drawing speed. Compared with low-alloy steels, wrought copper exhibits reduced resistance to deformation during cold working due to its lower yield strength (69 to 365 MPa vs. 250 to 1000 MPa) and higher ductility. Based on the material strength differences, engineering judgment, and the published literature on cold drawing low-alloy steels, a conservative estimate of

= 0.20 kWh·kg

−1 is used to cold draw OFHC copper prior to the DirectPowder

TM process.

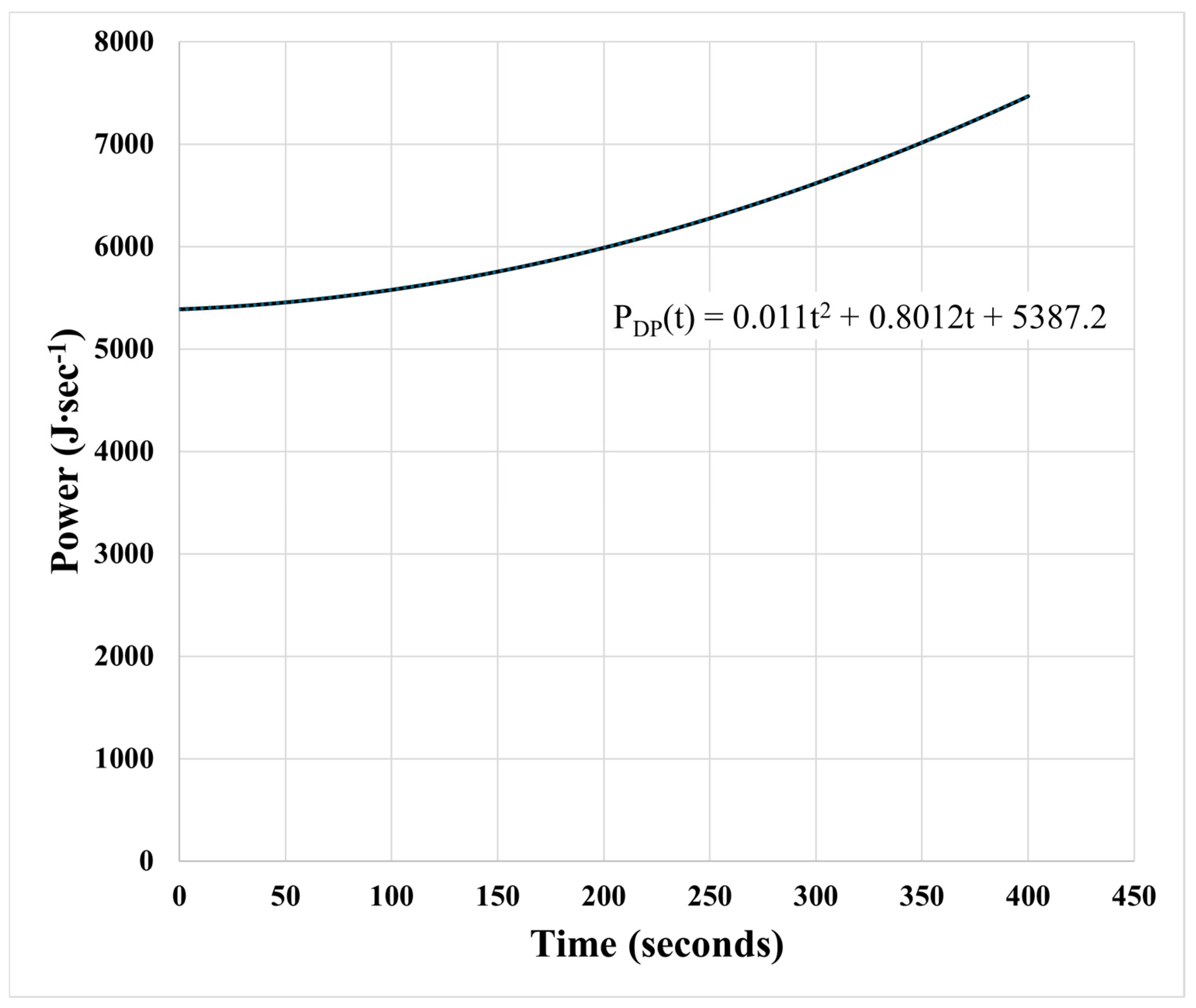

The power consumption for the DirectPowder

TM System (

), vacuum unit (

), and generator (

) was directly captured (see

Figure 6) and converted to energy consumption via curve fitting (see Equation (3)) and integration of the resulting curve over the timespan of 374 s (see Equation (4)). The power consumption for the vacuum unit (

= 1067 J) and generator (

= 142 J) was effectively constant over the duration of the cycle. After normalizing for the size of the test workpiece (0.413 kg), the resulting specific energy consumption midpoints for the components of the DirectPowder

TM process are

= 0.761 kWh·kg

−1,

= 0.134 kWh·kg

−1, and

= 0.018 kWh·kg

−1.

Approximately () by mass of the OFHC copper bar is converted to powder during the DirectPowderTM process. The remnant is an artifact of the fixture used to hold the bar during processing and to initially machine chips to clean the bar surface. Because the DirectPowderTM process can manufacture powders to a customized particle size range, 99% () of the usable bar is converted to usable powder.

3.2.3. Laser Powder Bed Fusion

The LPBF process for manufacturing OFHC copper components is energy-intensive and requires inert gas shielding. While several studies have been conducted on LPBF, reliable and detailed energy consumption data on LPBF of OFHC copper powders are scarce. In a parametric investigation using 316L powder, Kota et al. [

60] reported total energy consumption of 28.94 kWh·kg

−1. In yet another study, Cozzolino et al. [

61] estimated 49.55 kWh·kg

−1 where AlSi10Mg parts were printed. More generally, Kellens et al. [

62] suggested a range of 80 to 140 kWh·kg

−1 as a typical benchmark. These values encompass not only the laser operation but also ancillary systems such as powder handling, thermal management, and platform motion. Moreover, the reported energy consumption during LPBF is sensitive to material type, machine efficiency, build parameters, material absorptivity, and other factors. The continuous argon atmosphere used to prevent oxidation and ensure high surface quality during melting and solidification can require between 0.892 and 5.35 kg of compressed gas, equivalent to between 0.096 and 2.08 kWh·kg

−1 of energy to generate [

51]. Since LPBF systems may vary, 1.09 kWh·kg

−1 (

) will be used as a midpoint estimate.

In the absence of energy consumption data for the total energy consumption during LPBF for OFHC copper, the measure volumetric energy density (

) as described in Equation (5) [

63] is used as a proxy. In prior work, Caiazzo et al. [

64], Buhairi et al. [

63], de Leon Nope et al. [

65], and Stoll et al. [

66] have used

as a proxy metric for processing windows, quality, part density, performance, and energy use.

is a function of the laser power (

), scan speed (

), hatch spacing (

), and layer thickness (

).

To apply the

as a proxy, LPBF processing and total energy consumption data published by Kota et al. [

60] in their parametric study of 316L are used as midpoints for

and

(28.94 kWh·kg

−1) respectively. The parameters recommended by the manufacturer to process OFHC copper on the EOS M290 1 kW were used to calculate

(see

Table 3).

While VED does not directly account for material properties, it is adjusted in practice to account for them. Absorptivity (

) is an important property in LPBF because it determines how effectively the material absorbs laser energy, directly influencing melt pool formation, process stability, and overall energy efficiency during fabrication. 316L and OFHC copper have large differences in absorptivity (

= 35%,

= 5%). To reflect these differences and the inverse relationship between absorptivity and specific energy consumption, absorptivity was included (see Equation (6)) in the midpoint approximation of

. The resulting value of 240.43 kWh·kg

−1 is a reasonable estimate given copper’s low absorptivity and high conductivity.

Beyond the yield improvement in manufacturing OFHC copper powders via the DirectPowder

TM System, the process results in particles free of satellites and higher densities (see

Figure 7). The combination of these properties results in greater energy absorption than their EIGA-produced counterparts. In turn, less energy density is required during LPBF. These improvements translate into the ability to use thicker build layers, which ultimately results in shorter build times and additional energy savings, all while maintaining the same surface finish, or better, than EIGA powders in the final product.

To illustrate the improved efficiency during LPBF, a direct comparison of OFHC copper powders produced via EIGA and the DirectPowder

TM process was conducted using a full-height qualification build profile on the EOS M290 (1 kW), resulting in parts with a total mass of 10.24 kg.

EOS CuCP and

MPW OFHC Cu powders were used in the study. Parameters and results of the comparison are summarized in

Table 4. The

MPW OFHC Cu powder resulted in a 32.2% reduction (

) in build time compared to the

EOS CuCP powder, which has the potential to translate to a corresponding improvement in the total specific energy of LPBF,

, when the DirectPowder

TM process is used to manufacture powder. This improvement is applied in the Monte Carlo simulation implemented during the lifecycle impact assessment (

Section 3.3).

The preceding section established the quantitative foundation for evaluating the specific energy consumption of the two powder production routes, EIGA and DirectPowder

TM, along with subsequent LPBF manufacturing. By systematically compiling energy requirements, material inputs, and inert gas usage at each stage, the inventory provides a transparent, reproducible dataset for impact assessment. With these primary and secondary data sources in place, the next section applies this inventory to assess the GWP for each scenario. Using the energy inventory data (summarized in

Table 2), this limited-scope assessment estimates CO

2-eq emissions, enabling a climate-focused comparison of the powder production and additive manufacturing stages of the OFHC copper supply chain.

3.3. Life Cycle Impact Assessment

This section presents the life cycle impact assessment results for the powder production and additive manufacturing stages evaluated in this study. The analysis is intentionally limited in scope, focusing on CO

2-eq emissions resulting from electrical energy consumption. These emissions are reported in kg CO

2-eq and were calculated using the United States Environmental Protection Agency’s Greenhouse Gas Equivalencies Calculator, which uses CO

2, CH

4, and N

2O using GWP

100 values. United States national electricity data for 2002 was applied, with a constant midpoint emission factor (

) of 0.394 kg CO

2-eq per kWh [

67] (see

Appendix A.2 for emission factor calculation). Conversions from kg CO

2-eq per kWh were calculated using Equation (7).

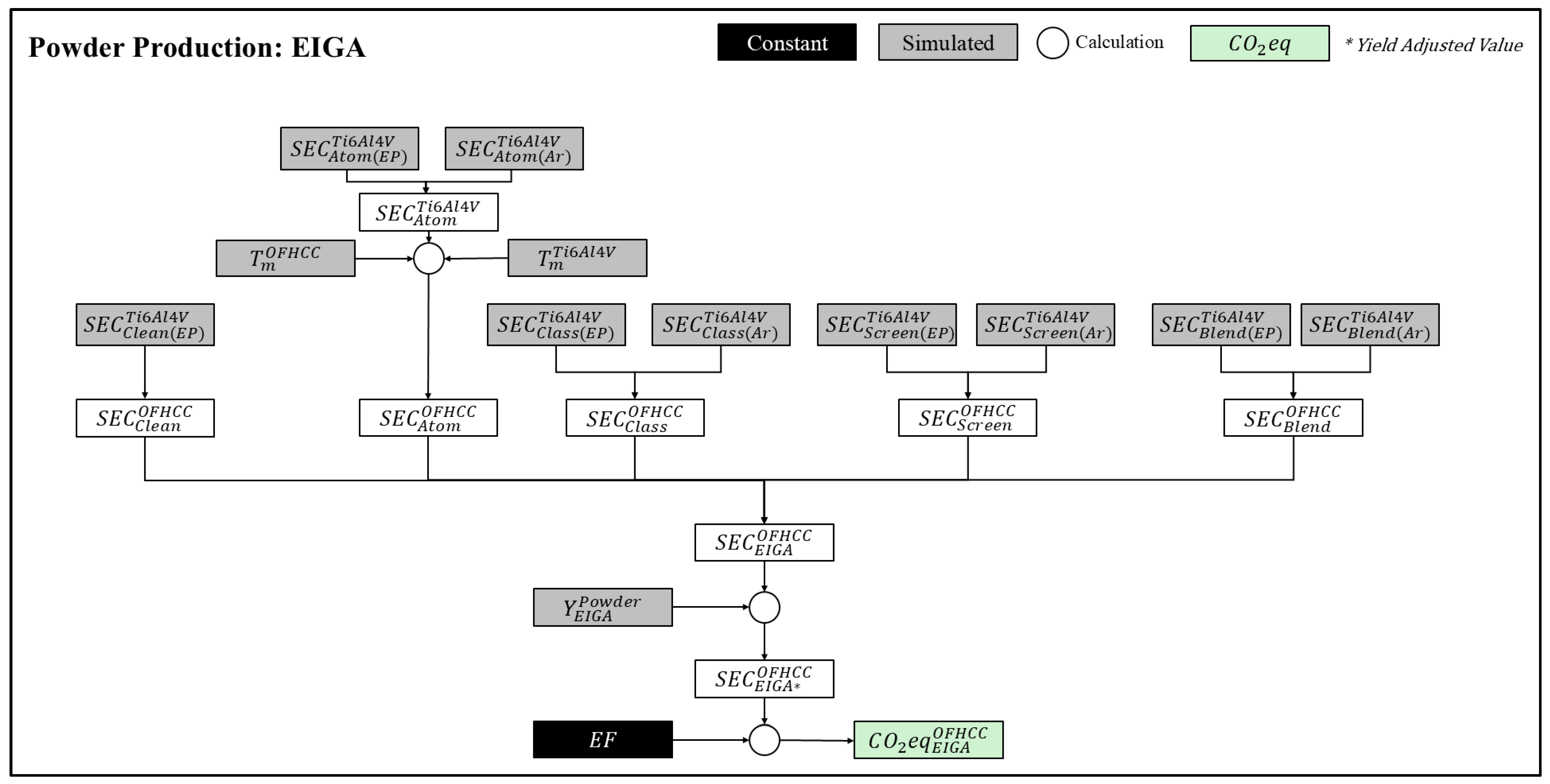

To calculate and compare the CO

2-eq emissions of the production pathways assessed in this study, a Monte Carlo simulation was implemented using Equation (7) and the values summarized in

Table 2.

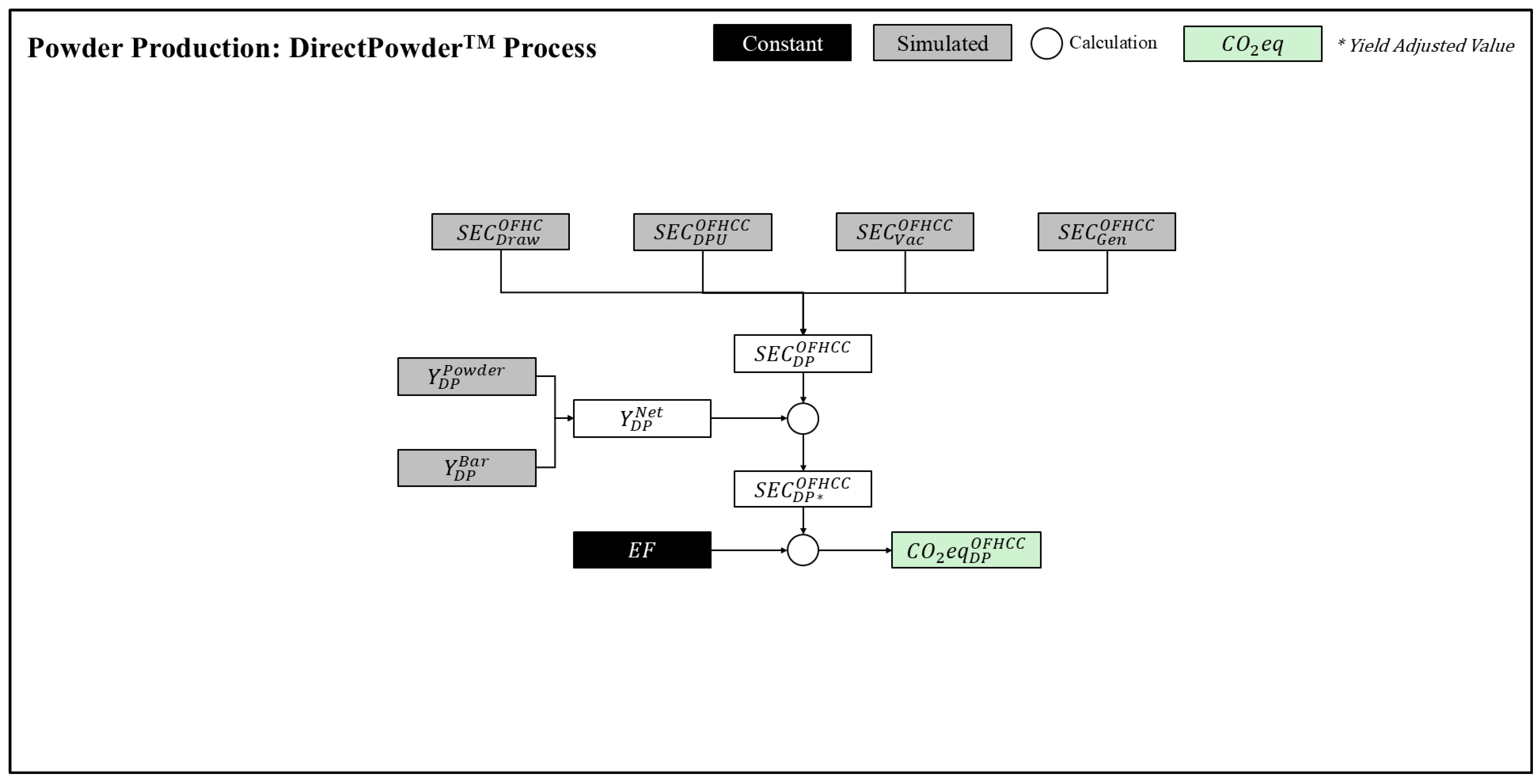

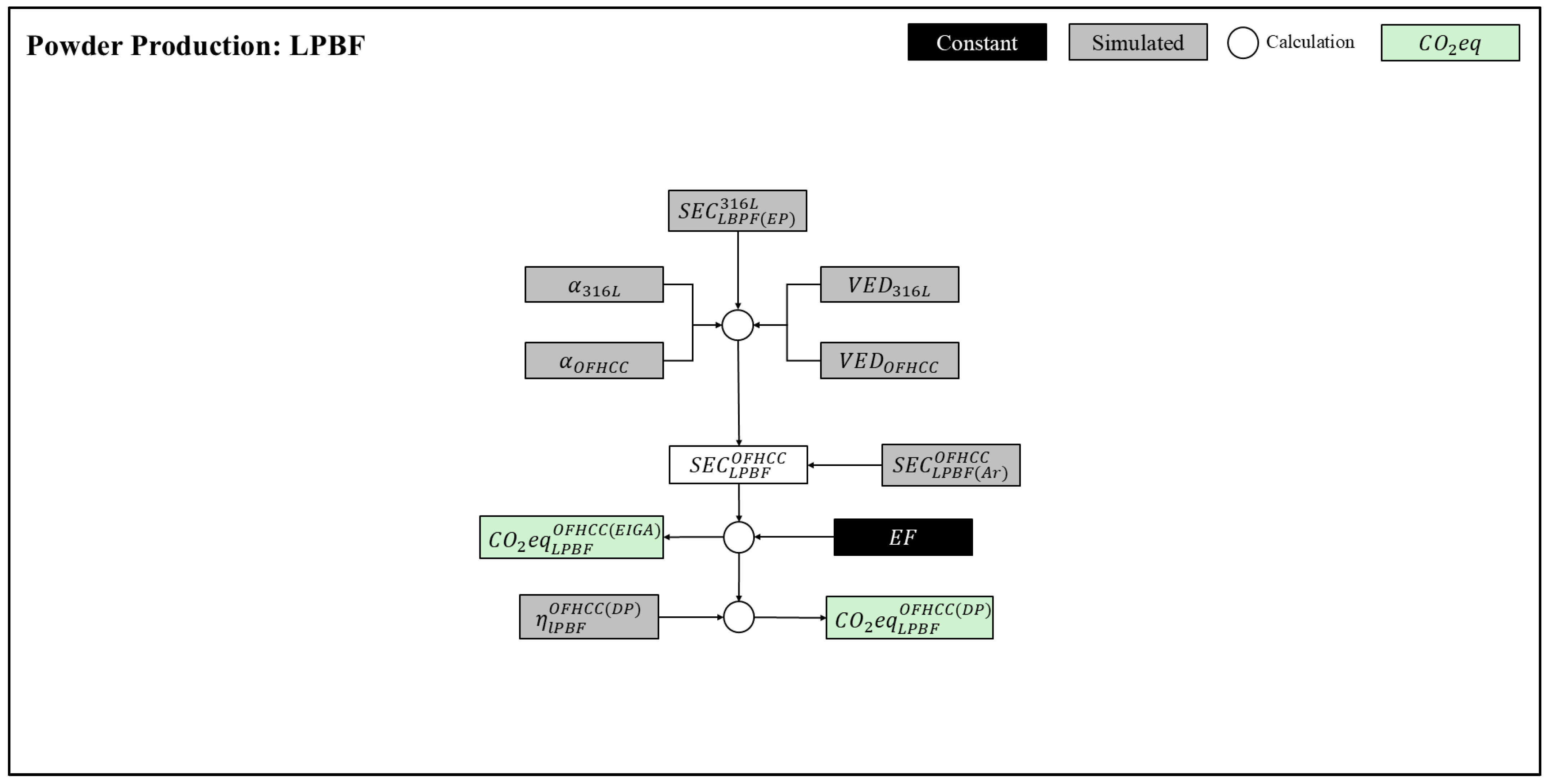

Figure 8,

Figure 9 and

Figure 10 illustrate the calculation flows of the Monte Carlo Simulation models for each phase of the processes being compared.

One distinct advantage that the DirectPowder

TM System has over other methods is the MPW Sidecar Concept. To evaluate the advantages, this study incorporated a scenario-based transportation analysis. Within the analysis, three realistic powder sourcing pathways were developed (see

Table 5). In the first scenario, OFHC copper powder is assumed to be manufactured via EIGA in Europe or Asia and shipped to North America via ocean freight, followed by truck. The second scenario involves production in the United States and truck transportation to its final destination. Only minimal trucking is assumed in the third scenario, where EIGA powder production is local to the parts manufacturer. The use of the Sidecar would result in effectively zero transportation impact and is indicated as the baseline. Mid-point emission factors were used for each transportation mode. The emission factor used for ocean freight was 5.70 × 10

−6 kg CO

2-eq·kg

−1·km

−1, and diesel truck transportation was 8.10 × 10

−5 kg CO

2-eq·kg

−1·km

−1 [

68]. To provide a direct comparison across the two production pathways outlined in this study, the specific stages are grouped into common categories as outlined in

Table 6.

4. Results and Discussion

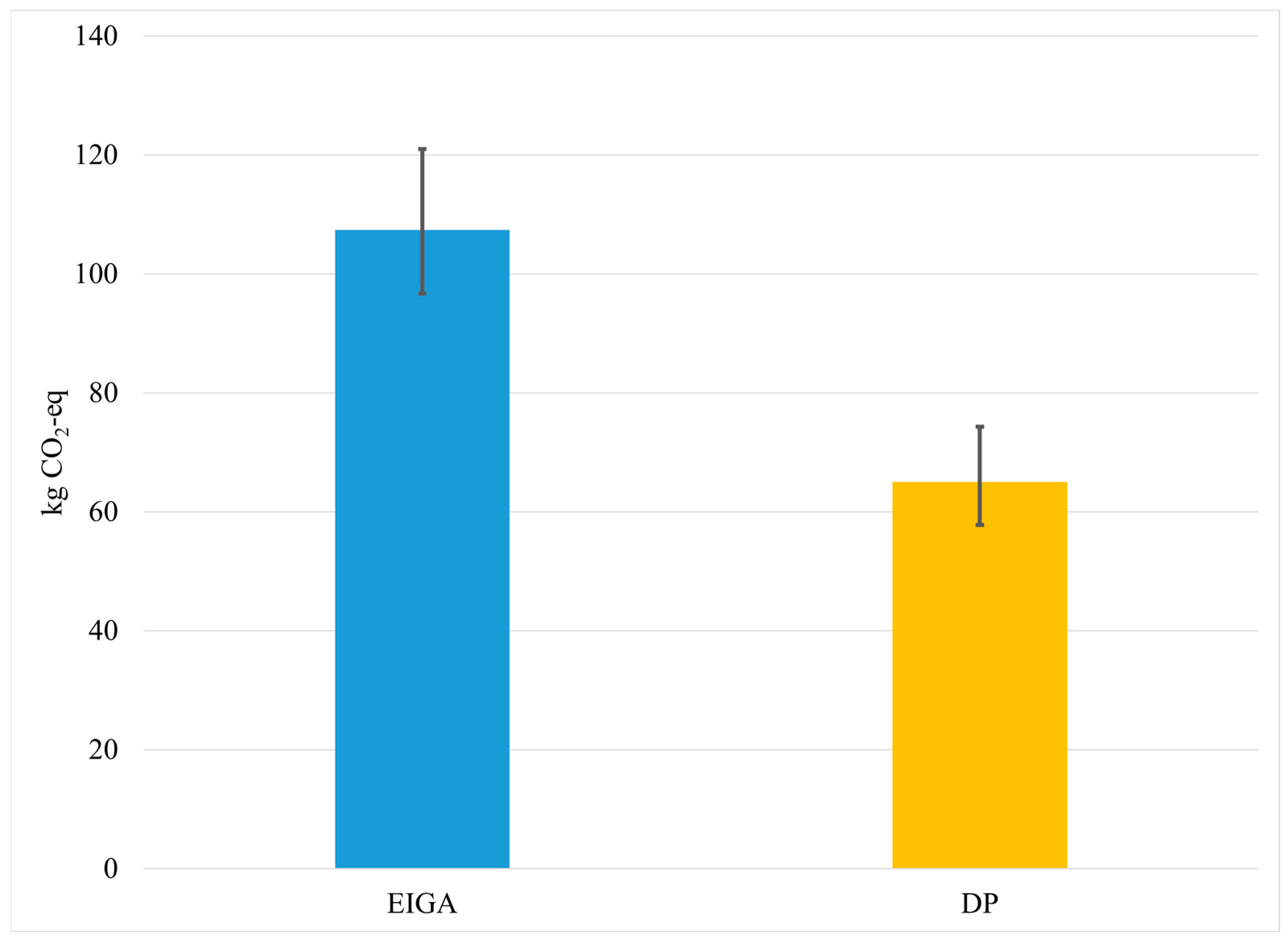

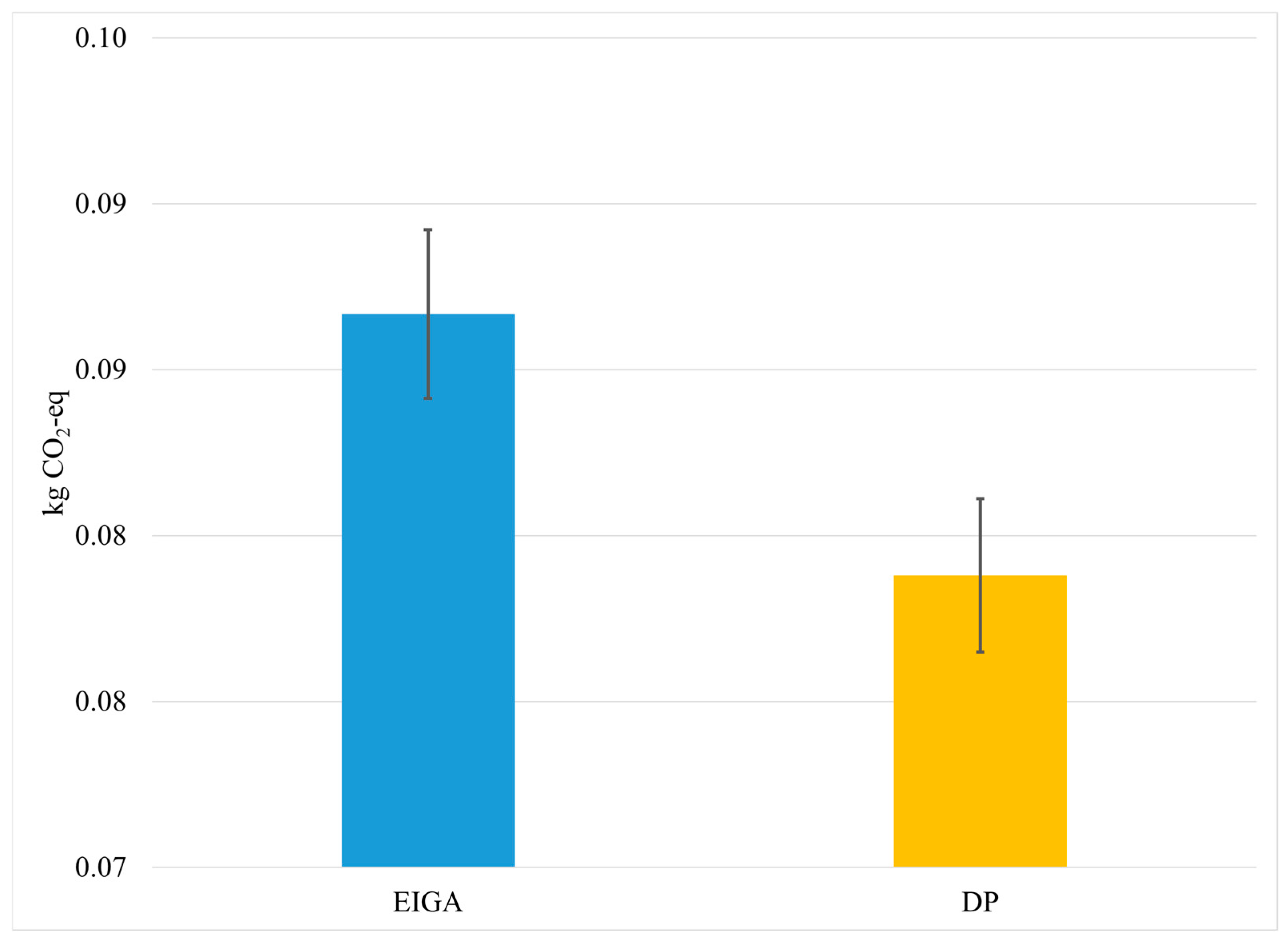

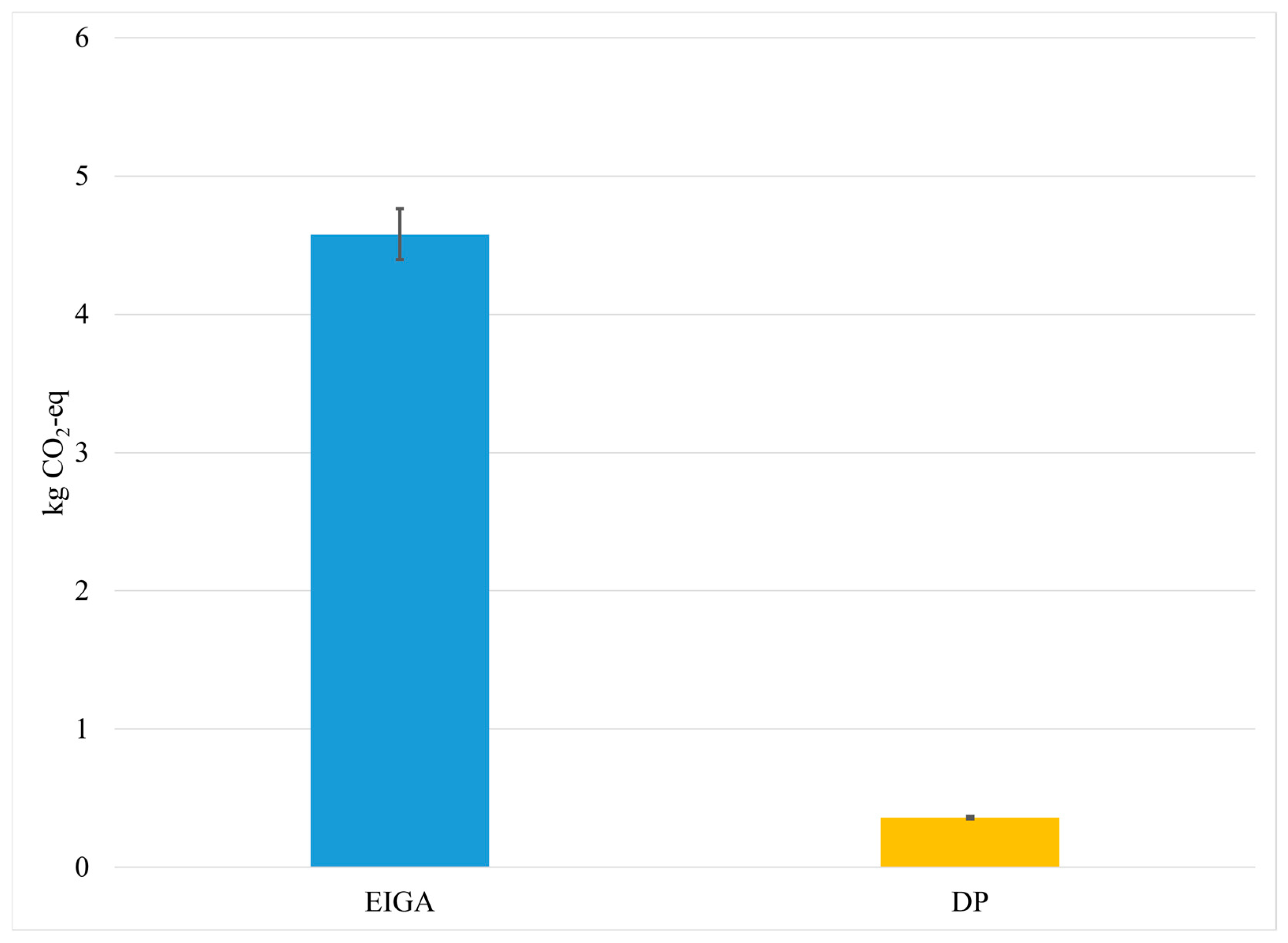

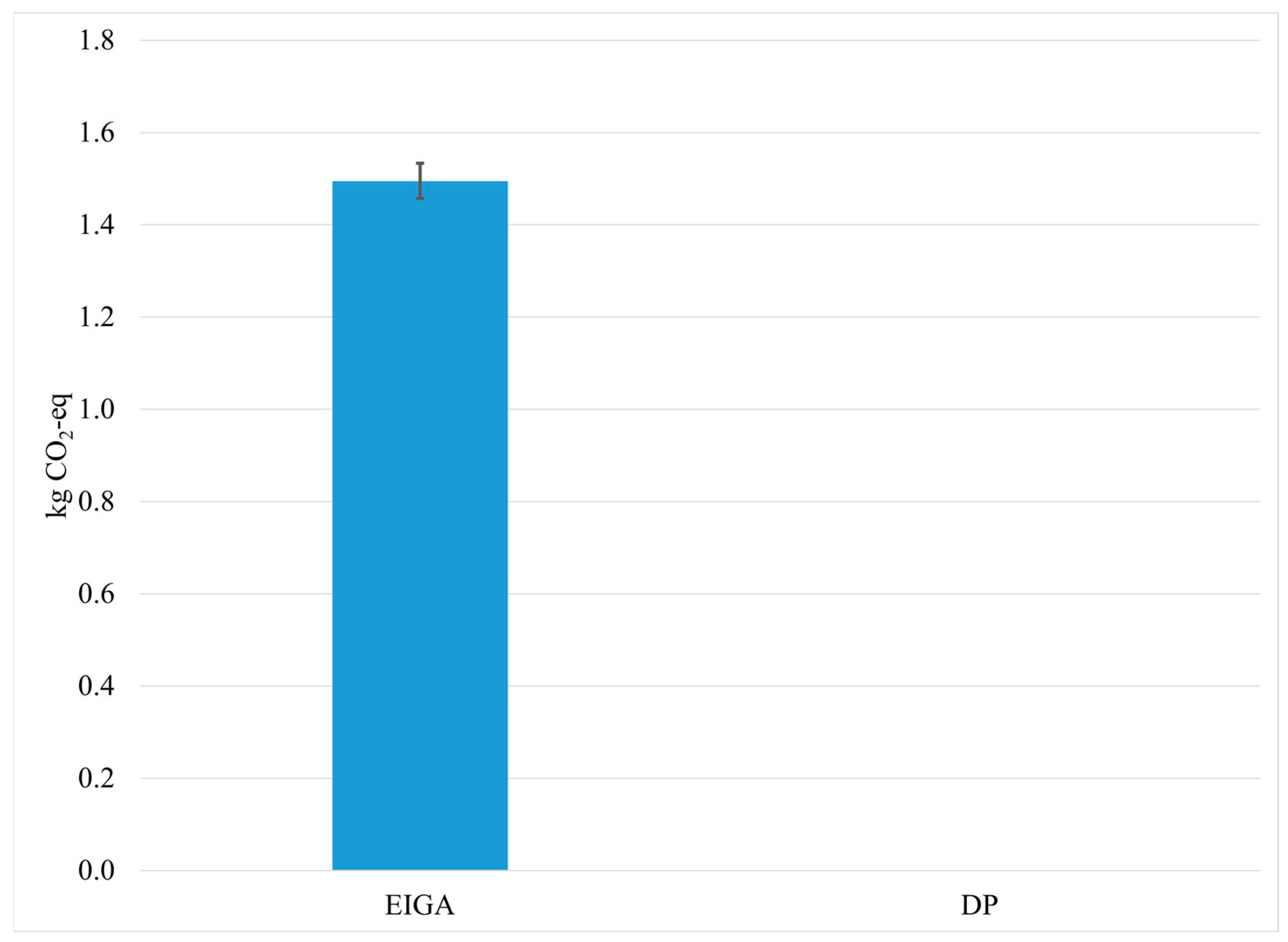

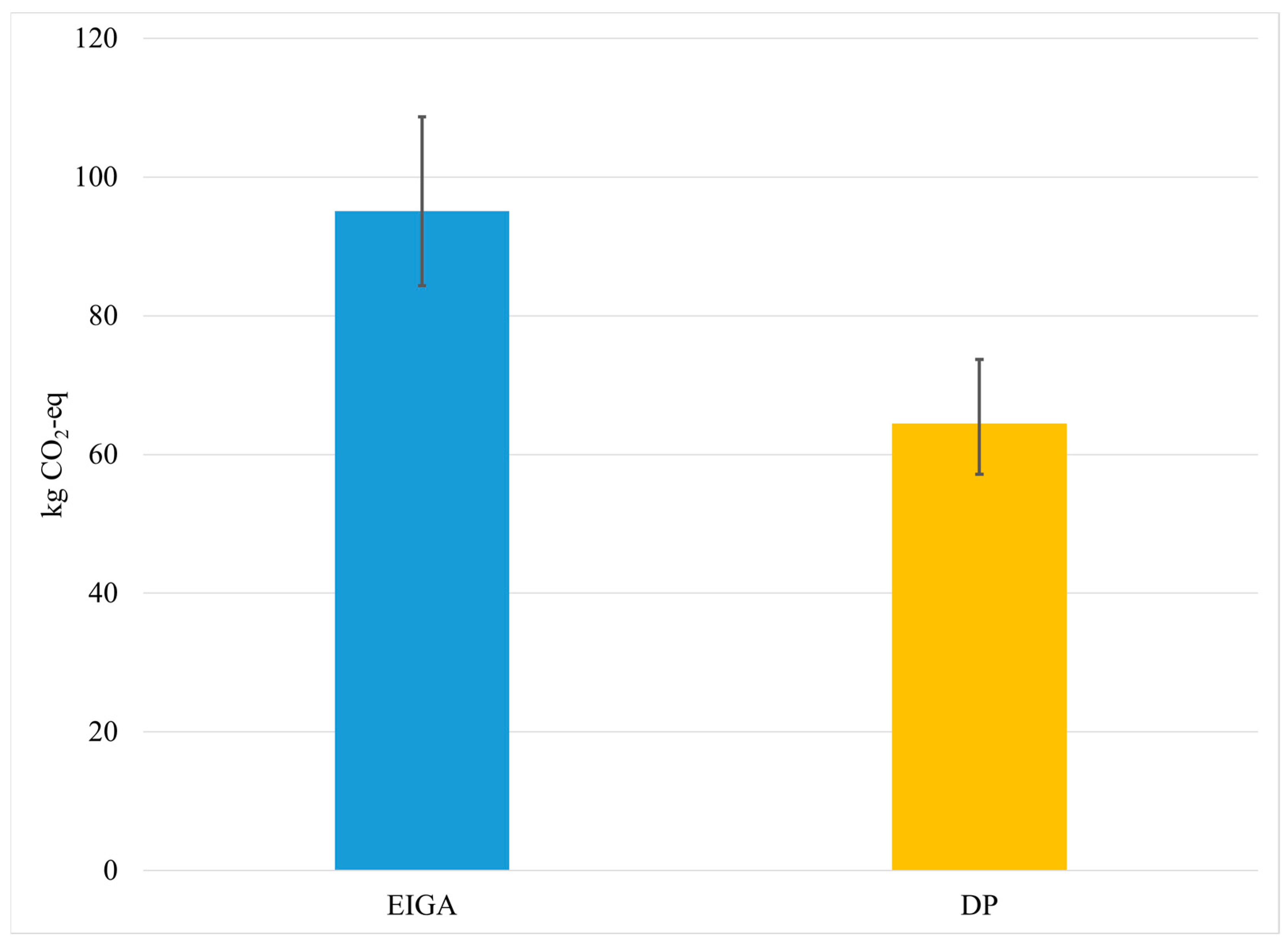

The results of the life cycle impact assessment are presented as CO2-eq emissions per 1 kg of usable OFHC copper powder, reflecting the GWP of each process.

Table 7 presents the overall results and results by life cycle stage group for each pathway. Overall, excluding transportation, the Monte Carlo analysis yielded median values of 107.40 kg CO

2-eq per kg for OFHC copper powder via the EIGA powder production pathway and 65.07 kg CO

2-eq per kg via the DirectPowder

TM process, demonstrating a 39.4% advantage for the DirectPowder

TM process when LPBF is considered and a 92.9% improvement over EIGA when LPBF is excluded from the comparison.

Figure 11,

Figure 12,

Figure 13,

Figure 14 and

Figure 15 illustrate the median simulated results with error bars, which represent the interquartile range (25th to 75th percentile). Each figure presents a paired comparison between the EIGA and DirectPowder

TM pathways for overall kg CO

2-eq emissions and for each life cycle stage group. Even with consideration for variation, the DirectPowder

TM pathway outperformed the EIGA pathway. A Mann–Whitney U test resulted in

p < 0.001 for each comparison, indicating a statistically significant difference in the simulated results between the pathways.

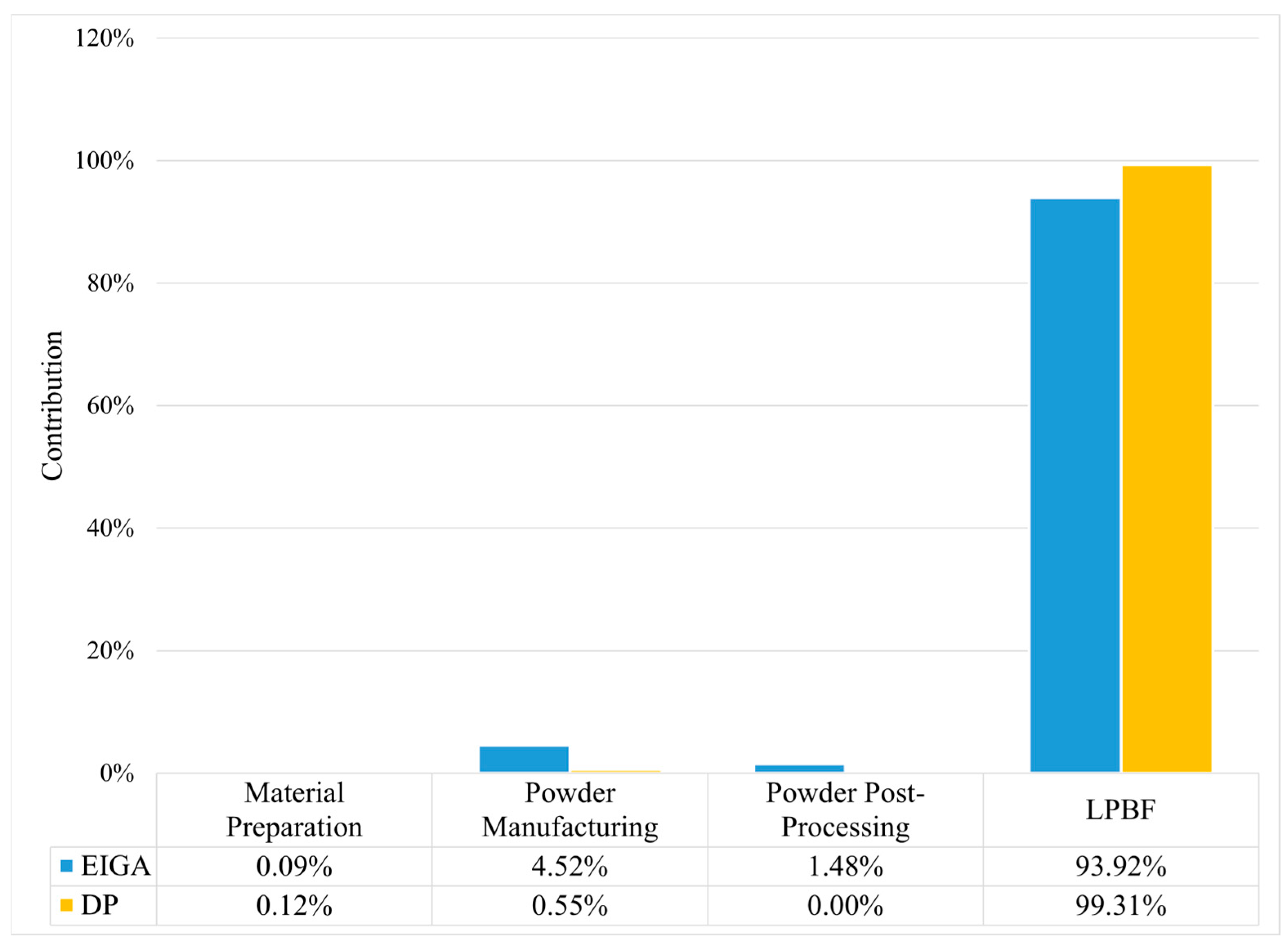

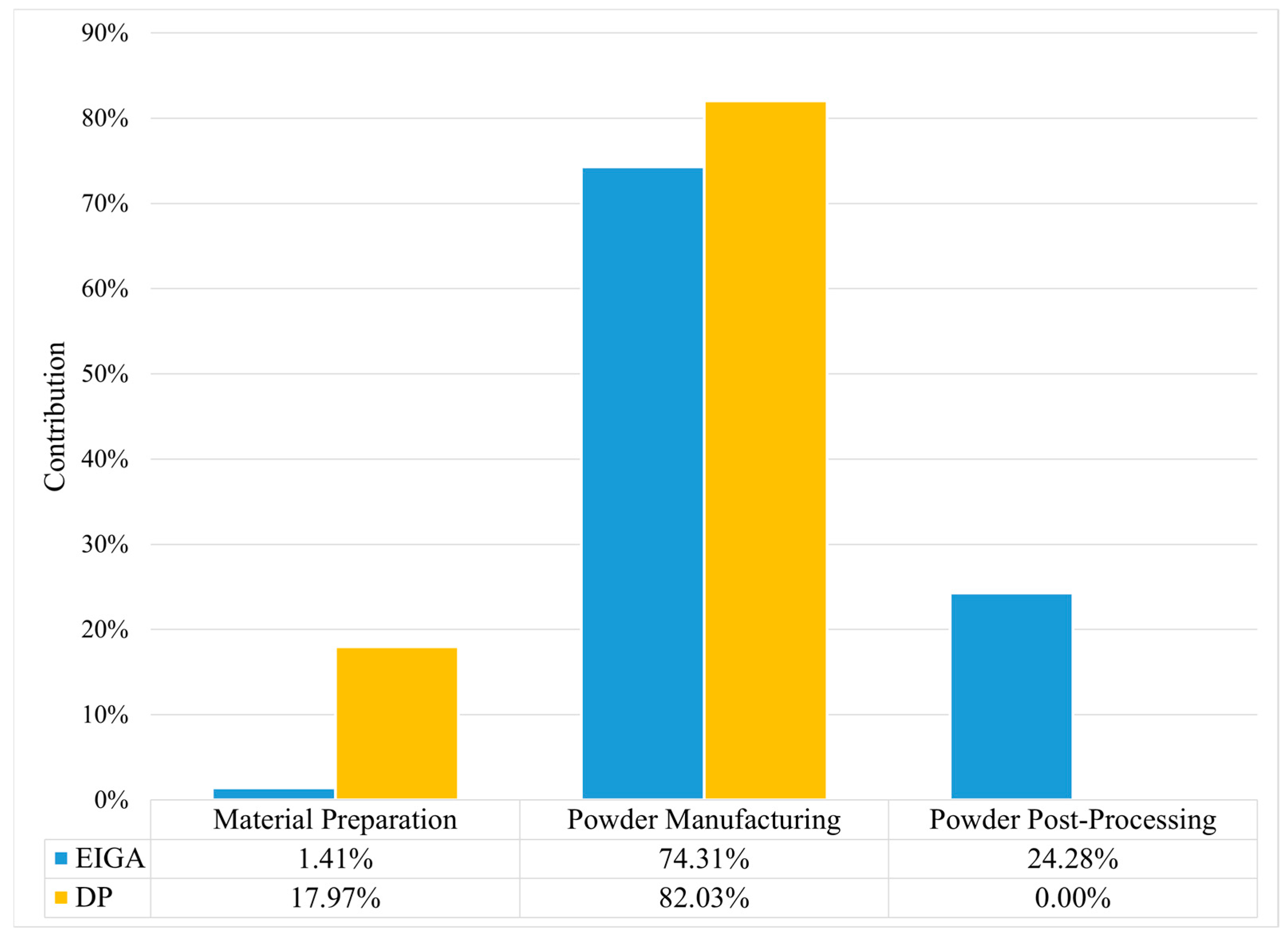

When considering the percent contribution of each lifecycle stage for each pathway, LPBF for both EIGA (93.92%) and DirectPowder

TM (99.31%) accounts for the greatest contribution to GHG emissions (see

Figure 16). Powder manufacturing (4.52%), powder post-processing (1.48%), and material preparation (0.09%) also contribute to production via the EIGA pathway, but are relatively negligible, as are all stages when the DirectPowder

TM process is used. When the LPBF contribution is removed from the total, powder manufacturing makes the greatest contribution with the DirectPowder

TM process contributing 82.03%, and EIGA contributing 74.31% (see

Figure 17). Material preparation contributes 17.97% to the DirectPowder

TM process and 1.41% when EIGA is used. Powder post-processing (24.28%) is the second-highest contributor to the EIGA pathway. There is no need for powder post-processing when the DirectPowder

TM process is implemented.

Overall, the DirectPowderTM pathway demonstrated a 39.4% reduction in kg CO2-eq compared to EIGA when LPBF was included, and a 92.9% reduction (6.156 to 0.439 kg CO2-eq) when LPBF was excluded from the analysis. Based on the median values, choosing the DirectPowderTM process results in a 92% reduction (4.576 to 0.3597 kg CO2-eq) in powder manufacturing, a 32% reduction (95.11 to 64.48 kg CO2-eq) in LPBF, and a 9% reduction (0.0867 to 0.0788 kg CO2-eq) in GHG emissions. Furthermore, when the DirectPowderTM process is used, post-processing of powder is no longer needed. In total, 11.438 kg CO2-eq per kg of OFHC copper produced is saved when using the DirectPowderTM process.

5. Conclusions

This limited-scope LCA aimed to evaluate and compare the CO

2-eq emissions from energy and process gas use across alternative OFHC copper powder production routes within AM supply chains. Compared to previous life cycle assessments of metal AM, such as Ti-6Al-4V and IN718, the GWP associated with OFHC copper production is shaped by distinct factors. While gas atomization remains a shared high-energy input across alloy types, the LPBF stage for OFHC copper exhibits greater energy intensity due to its low absorptivity and high thermal conductivity, both of which demand higher volumetric energy densities. For example, prior studies have reported LPBF energy demands ranging from 20 to 60 kWh·kg

−1 for alloys such as 316L and Ti-6Al-4V [

69]. In contrast, our midpoint estimate (

= 240.43 kWh·kg

−1) for copper exceeds those values even under conservative assumptions, highlighting the need for material-specific energy modeling in AM sustainability assessments and supporting efforts to develop lower-energy powder production techniques for challenging and critical materials such as copper.

The results underscore the advantage of the DirectPowderTM metal powder production pathway over EIGA in the production of OFHC copper products formed by the AM method, LPBF. Specifically, the EIGA manufacturing path exhibited a 39.4% higher kg CO2-eq per kg of usable powder when LPBF energy usage was included in the analysis. It was 92.9% higher than the DirectPowderTM route. The larger carbon footprint is primarily due to energy-intensive melting and atomization stages, low process yields, and suboptimal powders for the LPBF process. On the other hand, the DirectPowderTM method for producing OFHC copper via AM leverages a powder manufacturing process that uses less energy, produces powders that require no additional post-processing (e.g., screening, air classification, or blending), and is optimized for LPBF, resulting in shorter build times.

Although publicly available data on the production of OFHC copper powders via AM is limited, these findings align with trends observed in prior studies on aluminum and nickel-based metal AM powders, where atomization consistently ranks as a hotspot [

70]. Because of the high energy intensity of the LPBF process, upstream powder-processing steps are critical for reducing the AM process’s carbon footprint. Even so, the DirectPowder

TM method minimizes the impact of LPBF by improving powder absorptivity compared to traditional atomization methods. Future system-level improvements to LPBF equipment efficiency, including inert gas recycling, will yield additional gains. Overall, the results suggest that sustainable supply chain design extends much further beyond the selection of the printing method and includes powder production technologies as well.

5.1. Limitations

It is important to acknowledge that this study focused on a limited scope, rather than the full spectrum of environmental impacts. Data on energy consumption and process yields were directly measured, acquired from secondary sources, or derived using models based on these sources. Therefore, the results should be interpreted as indicative, relative, and directional rather than definitive. However, by applying consistent assumptions across both powder production scenarios, the study provides a valid comparative scenario analysis that can inform decision-makers in AM supply chains. While this study contributes meaningfully to the existing literature and lays the groundwork for future research, it is not appropriate to make broad claims about sustainability without a multi-impact category analysis.

A detailed cost analysis was beyond the scope of this energy-based LCA. However, a cost analysis that accounts for the tradeoffs between cost and sustainability will be critical for full industrial adoption. In addition, such an analysis would also better help contextualize the findings for supply chain stakeholders. For example, the DirectPowderTM processes were designed with sustainability in mind, whereas improving existing EIGA processes and lowering environmental impact may require significant investment (e.g., argon recycling).

5.2. Future Research

Future research should expand the assessment scope to include multi-impact categories (e.g., human toxicity, resource depletion, water use). Further, a full cradle-to-gate, cradle-to-grave, or cradle-to-cradle analysis, inclusive of raw material processing (e.g., mining, smelting, refining) and recycling energy streams, is recommended to capture a full view of the AM supply chain sustainability for OFHC copper powder products. Although this study provides a foundation, a collection of direct primary data across all the processes analyzed will improve the fidelity of the results and validate those presented herein. Exploring other opportunities to improve AM’s impact would also be worthwhile. More specifically, including renewable energy sources, process gas recovery systems, and recycling would be interesting. Adding detailed cost analyses that evaluate cost-sustainability tradeoffs, such as the impact of the DirectPowderTM process on transportation and inventory or the costs required to upgrade EIGA processes to reduce environmental impact, would be beneficial as well. The DirectPowderTM Sidecar concept provides an additional advantage by reducing the need to transport powders. However, this advantage is only realized when large quantities are shipped over long distances. Including the Sidecar concept in a future cost analysis would further clarify its benefits. Future work should explore the use of mathematical modeling to optimize parameter settings for atomizing OFHC copper powder and manufacturing parts via LPBF, aiming to minimize both cost and energy use. Such analysis could yield additional insights and offer valuable decision support for practitioners. Lastly, the inclusion of additional AM printing technologies, powder manufacturing methods, and material systems would enhance the technical and commercial feasibility of AM, as well as support sustainability goals and decision-making.