Effects of Returning Mushroom Residues to the Field on Soil Properties and Rice Growth at Different Stages

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Material Collection

2.2. Experimental Design

2.3. Sample Collection and Analysis Methods

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

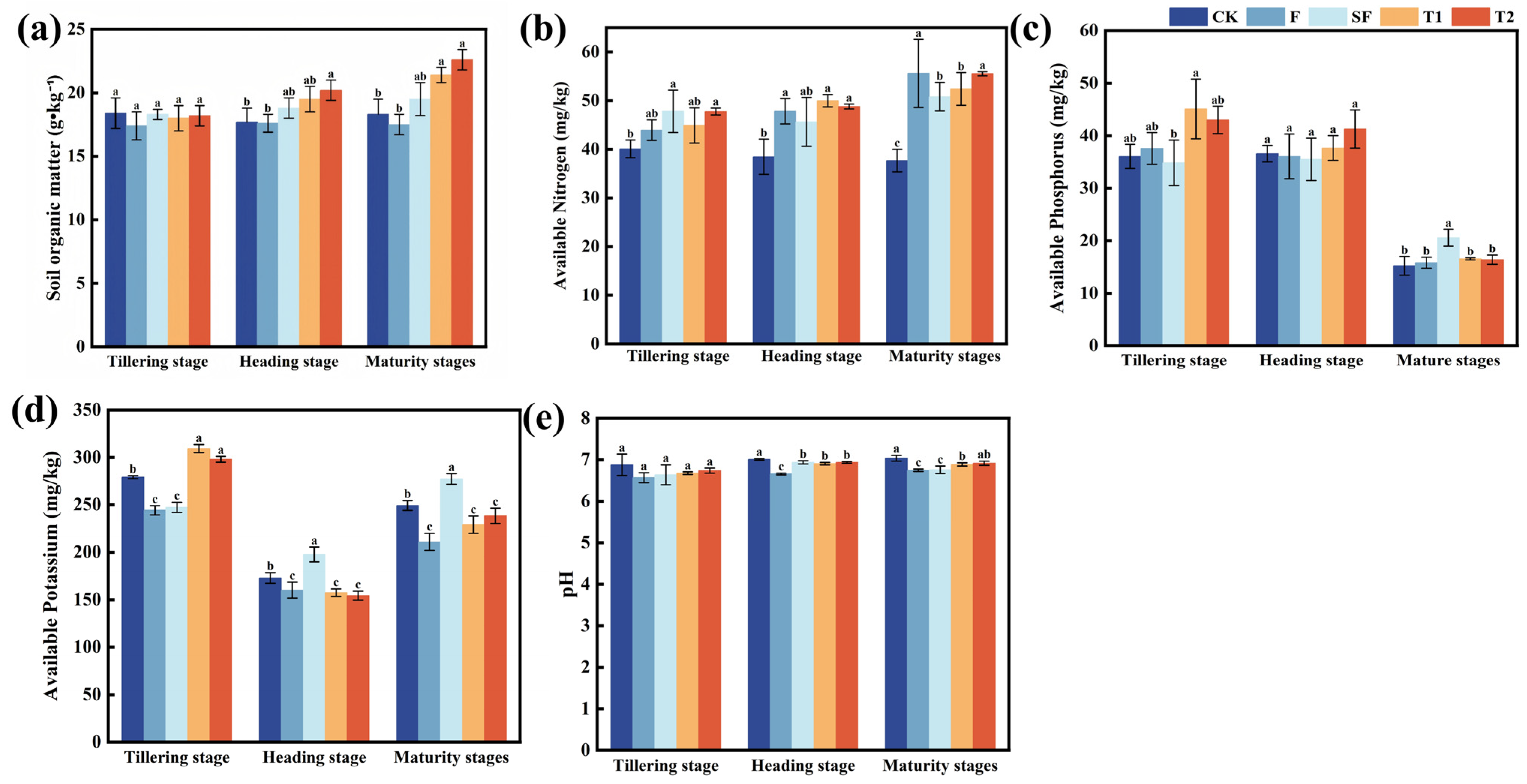

3.1. Various in Soil Nutrients

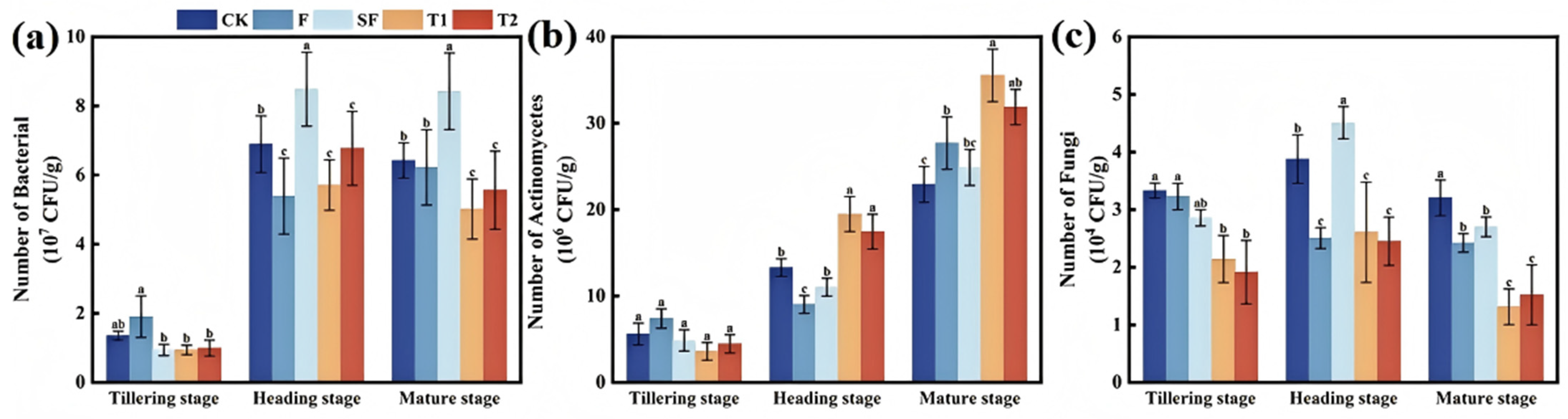

3.2. Number of Soil Microbial Species

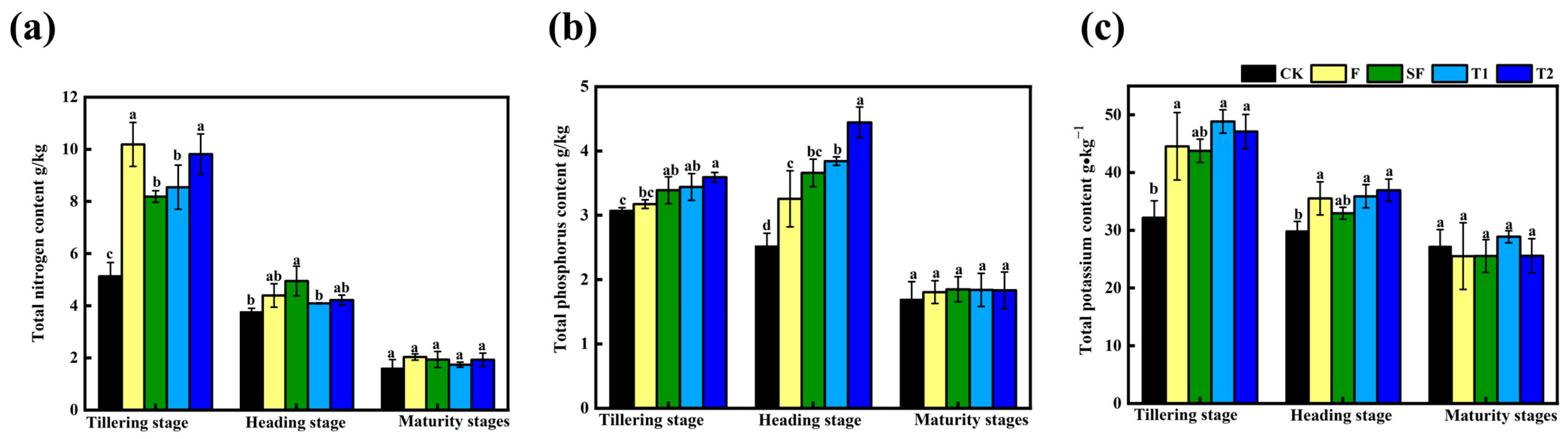

3.3. Nutrient Content of Plants in Rice

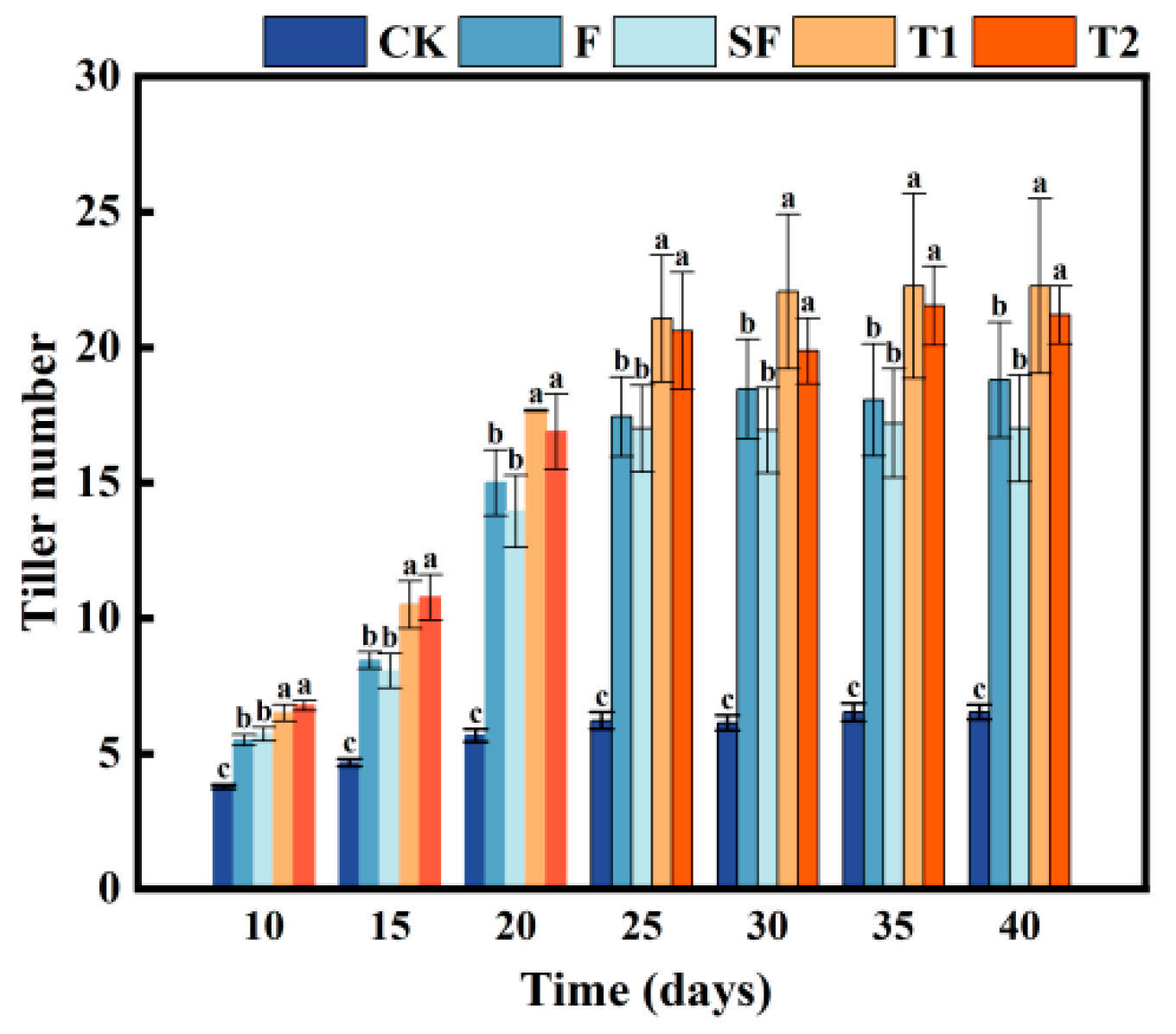

3.4. Rice Tiller Number

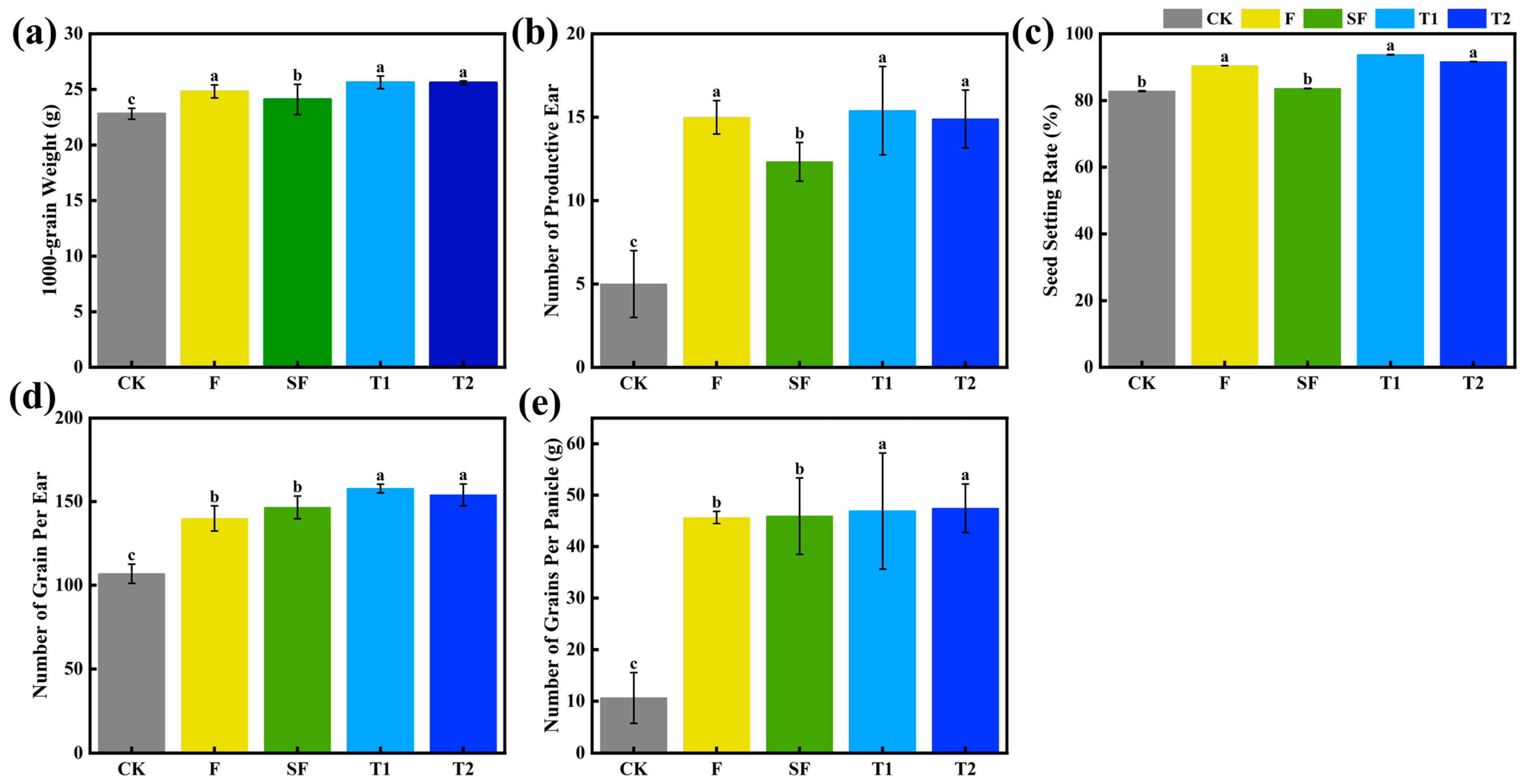

3.5. Rice Yield Traits

4. Discussion

4.1. Improvement of Soil Fertility by Mushroom Residues

4.2. Improvement of Soil Microbial Structure by Straw Returning

4.3. Promoting Plant Growth by Mushroom Residue Returning

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sun, M.; Xu, X.; Wang, C.; Bai, Y.; Fu, C.; Zhang, L.; Fu, R.; Wang, Y. Environmental burdens of the comprehensive utilization of straw: Wheat straw utilization from a life-cycle perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 259, 120702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Yu, P.; Xu, X. Straw utilization in china—Status and recommendations. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smil, V. Crop Residues: Agriculture’s Largest Harvest: Crop residues incorporate more than half of the world’s agricultural phytomass. Bioscience 1999, 49, 299–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Dong, F.; Chen, M.; Zhu, J.; Tan, J.; Fu, X.; Wang, Y.; Chen, S. Advances in recycling and utilization of agricultural wastes in China: Based on environmental risk, crucial pathways, influencing factors, policy mechanism. Procedia Environ. Sci. 2016, 31, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Ma, Y.; Ma, L. Utilization of straw in biomass energy in China. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2007, 11, 976–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, J.; Zhao, Z.; Li, X.; Zhao, H.; Lin, C. Comprehensive benefit of crop straw return volume under sustainable development management concept in Heilongjiang, China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.; Zhao, W.; Li, T.; Cheng, X.; Liu, Q. Balancing straw returning and chemical fertilizers in China: Role of straw nutrient resources. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 81, 2695–2702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, M.; Zhang, J.; Kong, Z.; Fleming, R.M.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, Z. Potential environmental benefits of substituting nitrogen and phosphorus fertilizer with usable crop straw in China during 2000–2017. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 267, 122125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Wu, Q.; Wang, F.; Zhang, B. Is straw return-to-field always beneficial? Evidence from an integrated cost-benefit analysis. Energy 2019, 171, 393–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, X.K.; Wei, L.; Turner, N.C.; Ma, S.C.; Yang, M.D.; Wang, T.C. Improved straw management practices promote in situ straw decomposition and nutrient release, and increase crop production. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 250, 119514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z.; Shah, T.; Zhang, L.; Liu, H.; Peng, S.; Nie, L. Effect of straw returning on soil organic carbon in rice–wheat rotation system: A review. Food Energy Secur. 2020, 9, e200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Shen, Y.; Liu, Y. State of the art of straw treatment technology: Challenges and solutions forward. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 313, 123656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Sun, S.; Yao, B.; Peng, Y.; Gao, C.; Qin, T.; Zhou, Y.; Sun, C.; Quan, W. Effects of straw return and straw biochar on soil properties and crop growth: A review. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 986763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Lin, B.-J.; Chen, J.-S.; Duan, H.-X.; Sun, Y.-F.; Zhao, X.; Dang, Y.P.; Xu, Z.-Y.; Zhang, H.-L. Strategies for crop straw management in China’s major grain regions: Yield-driven conditions and factors influencing the effectiveness of straw return. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2025, 212, 107941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Shu, L.; Li, Y.; Zhou, S.; Zhang, G.; Wu, Y.; Yang, Z. Pretreatment and composting technology of agricultural organic waste for sustainable agricultural development. Heliyon 2023, 9, e16311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, S.Q.; Zhao, R.Y.; Chen, Z.C. Review of the pretreatment and bioconversion of lignocellulosic biomass from wheat straw materials. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 91, 483–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, L.; Wei, Z.; Song, C.; Pang, C.; Pang, X. Strategies for efficient degradation of lignocellulose from straw: Synergistic effects of acid-base pretreatment and functional microbial agents in composting. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 508, 161048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Li, X.; Fadel, J.G. Oyster mushroom cultivation with rice and wheat straw. Bioresour. Technol. 2002, 82, 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, T.; Zhang, K.; Shi, X.; Liu, W.; Yu, F.; Liu, D. Crop–Mushroom Rotation: A Comprehensive Review of Its Multifaceted Impacts on Soil Quality, Agricultural Sustainability, and Ecosystem Health. Agronomy 2025, 15, 563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Wu, Z.; Li, W.; Sun, H.; Chai, Y.; Li, T.; Qin, P. Expanding the valorization of waste mushroom substrates in agricultural production: Progress and challenges. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 2355–2373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pilz, D.; Molina, R. Commercial harvests of edible mushrooms from the forests of the Pacific Northwest United States: Issues, management, and monitoring for sustainability. For. Ecol. Manag. 2002, 155, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Q.; Liu, W.; Huang, H.; Peng, Z.; Deng, L. Responses of crop yield, soil fertility, and heavy metals to spent mushroom residues application. Plants 2024, 13, 663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C. Integrated nutrient management significantly improves pomelo (Citrus grandis) root growth and nutrients uptake under acidic soil of southern China. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, G.; Liu, Z.; Guo, Z.; He, J.; Ye, Y.; Xu, H.; Hu, T. Compost with spent mushroom substrate and chicken manure enhances rice seedling quality and reduces soil-borne pathogens. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 77743–77756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anantrao, M.B.P. Influence of Enriched Spent Mushroom Substrate on. Doctoral Dissertation, Mahatma Phule Krishi Vidyapeeth, Ahilyanagar, India, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Castelo-Gutiérrez, A.A.; García-Mendívil, H.A.; Castro-Espinoza, L.; Lares-Villa, F.; Arellano-Gil, M.; Figueroa-López, P.; Gutiérrez-Coronado, M.A. Residual mushroom compost as soil conditioner and bio-fertilizer in tomato production. Rev. Chapingo Ser. Hortic. 2016, 22, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Zeng, G.; Liu, Z.; Guo, Z.; Zhang, W.; Li, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Xu, H. Replacing traditional nursery soil with spent mushroom substrate improves rice seedling quality and soil substrate properties. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 39625–39636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Juan, J.; Xiao, T.; Zhang, J.; Chen, H.; Song, X.; Chen, M.; Huang, J. The physical structure of compost and C and N utilization during composting and mushroom growth in Agaricus bisporus cultivation with rice, wheat, and reed straw-based composts. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2021, 105, 3811–3823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.; Rao, W.; Zheng, F.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Li, T. Distribution and Transformation of Soil Phosphorus Forms under Different Land Use Patterns in an Urban Area of the Lower Yangtze River Basin, South China. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.H.; Wu, J.F.; Pan, X.H.; Shi, Q.H.; Zhu, D.F. Effects of straw incorporation method on double cropping rice yield and the top-three leaf characteristics. Chin. J. Eco-Agric. 2013, 21, 1459–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.-B.; Chen, J.; Mao, S.-C.; Han, Y.-C.; Chen, F.; Zhang, L.-F.; Li, Y.-B.; Li, C.-D. Comparison of greenhouse gas emissions of chemical fertilizer types in China’s crop production. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 141, 1267–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banik, S.; Nandi, R. Effect of supplementation of rice straw with biogas residual slurry manure on the yield, protein and mineral contents of oyster mushroom. Ind. Crops Prod. 2004, 20, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasuquin, E.; Lafarge, T.; Tubana, B. Transplanting young seedlings in irrigated rice fields: Early and high tiller production enhanced grain yield. Field Crops Res. 2008, 105, 141–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bremner, J.M.; Jenkinson, D.S. Determination of organic carbon in soil: I. Oxidation by dichromate of organic matter in soil and plant materials. J. Soil Sci. 1960, 11, 394–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulvaney, R.L.; Khan, S.A. Diffusion methods to determine different forms of nitrogen in soil hydrolysates. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2001, 65, 1284–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crouch, S.R.; Malmstadt, H.V. Mechanistic investigation of molybdenum blue method for determination of phosphate. Anal. Chem. 1967, 39, 1084–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanford, G.; English, L. Use of the flame photometer in rapid soil tests for K and Ca. Agron. J. 1949, 41, 446–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warcup, J.H. Studies on the occurrence and activity of fungi in a wheat-field soil. Trans. Br. Mycol. Soc. 1957, 40, 237-IN3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Górecka, H.; Chojnacka, K.; Górecki, H. The application of ICP-MS and ICP-OES in determination of micronutrients in wood ashes used as soil conditioners. Talanta 2006, 70, 950–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansson, J.K.; Hofmockel, K.S. Soil microbiomes and climate change. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2020, 18, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, D.; Song, R.; Yan, B.; Dai, J.-F.; Fang, H.; Zheng, Q.-Q.; Gu, Y.; Shao, X.-L.; Chen, H.; Li, M.-L.; et al. Reductive soil disinfestation by mixing carbon nanotubes and mushroom residues to mitigate the continuous cropping obstacles for Lilium Brownii. Crop Health 2024, 2, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramanathan, K.M.; Krishnamoorthy, K.K. Nutrient uptake by paddy during the main three stages of growth. Plant Soil 1973, 39, 29–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, Y.; Xu, M.; Wang, W.; Sun, X.; Zhao, K. Return rate of straw residue affects soil organic C sequestration by chemical fertilization. Soil Tillage Res. 2011, 113, 70–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berhane, M.; Xu, M.; Liang, Z.; Shi, J.; Wei, G.; Tian, X. Effects of long-term straw return on soil organic carbon storage and sequestration rate in North China upland crops: A meta-analysis. Glob. Change Biol. 2020, 26, 2686–2701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pintarič, M.; Štuhec, A.; Tratnik, E.; Langerholc, T. Spent mushroom substrate improves microbial quantities and enzymatic activity in soils of different farming systems. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Wang, M.; Zhao, L.; Fan, B.; Sun, N.; Liu, J.; Sun, X.; Dong, Z. The role of cattle manure-driven polysaccharide precursors in humus formation during composting of spent mushroom substrate. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1375808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, G.; Ma, Y.; Ma, X.; Wang, X.; Lu, C.; Xu, W.; Luo, J.; Guo, D. Changes in soil organic carbon components and microbial community following spent mushroom substrate application. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1351921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, D.P.C.; Cameron, K.C.; Cornforth, I.S.; Main, B.E. Release of sulphate, potassium, calcium and magnesium from spent mushroom compost under laboratory conditions. Biol. Fertil. Soils 1997, 26, 146–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, Y.H.; Zhuge, Y.P.; Wei, M.; Chao, Y.; Liu, A.H. Effect of extraneous organic materials on the mineralization of nitrogen in soil. Chin. J. Soil Sci. 2009, 40, 315–320. [Google Scholar]

- Niu, Y.F.; Chai, R.S.; Jin, G.L.; Wang, H.; Tang, C.X.; Zhang, Y.S. Responses of root architecture development to low phosphorus availability: A review. Ann. Bot. 2013, 112, 391–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, G.; Huan, W.; Song, H.; Lu, D.; Chen, X.; Wang, H.; Zhou, J. Effects of straw incorporation and potassium fertilizer on crop yields, soil organic carbon, and active carbon in the rice–wheat system. Soil Tillage Res. 2021, 209, 104958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Wang, D.Z. Long-term effects of returning wheat straw to croplands on soil compaction and nutrient availability under conventional tillage. Plant Soil Environ. 2018, 59, 280–286. [Google Scholar]

- Shang, L.; Liqiang, W.; Zhou, X.; Li, S.; Li, X. Effects of organic fertilizer on soil nutrient status, enzyme activity, and bacterial community diversity in leymus chinensis steppe in inner mongolia, China. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0240559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Wang, H.; Wang, J. Synthesis and application of a compound microbial inoculant for effective soil remediation. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 120915–120929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Chang, J.; Wu, W.X.; Xu, M.H.; Qiu, L.Y. Effects of returning field of mushroom residue on soil properties and fruit quality in pear orchard. J. Nucl. Agric. Sci. 2012, 26, 821–827. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatti, A.A.; Haq, S.; Bhat, R.A. Actinomycetes benefaction role in soil and plant health. Microb. Pathog. 2017, 111, 458–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanafi, F.H.M.; Rezania, S.; Taib, S.M.; Din, M.F.M.; Yamauchi, M.; Sakamoto, M.; Hara, H.; Park, J.; Ebrahimi, S.S. Envi-ronmentally sustainable applications of agro-based spent mushroom substrate (sms): An overview. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 2018, 20, 1383–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumura, Y.; Minowa, T.; Yamamoto, H. Amount, availability, and potential use of rice straw (Agricultural residue) biomass as an energy resource in Japan. Biomass Bioenergy 2005, 29, 347–354. [Google Scholar]

| Treatment | Organic Material (g/pot) | Urea (g/pot) | Calcium-Magnesium Phosphate (g/pot) | KCl (g/pot) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CK | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| F | 0.00 | 9.78 | 25.00 | 7.50 |

| SF | 180.00 | 6.33 | 18.95 | 0.46 |

| T1 | 164.88 | 6.33 | 18.36 | 1.40 |

| T2 | 49.51 | 6.33 | 9.21 | 6.05 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Sun, C.; Song, K.; Hu, R.; Wang, F.; Yin, X.; Zhou, C.; Ni, G. Effects of Returning Mushroom Residues to the Field on Soil Properties and Rice Growth at Different Stages. Sustainability 2026, 18, 1266. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18031266

Sun C, Song K, Hu R, Wang F, Yin X, Zhou C, Ni G. Effects of Returning Mushroom Residues to the Field on Soil Properties and Rice Growth at Different Stages. Sustainability. 2026; 18(3):1266. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18031266

Chicago/Turabian StyleSun, Chulan, Kailun Song, Rong Hu, Fei Wang, Xin Yin, Chunhuo Zhou, and Guorong Ni. 2026. "Effects of Returning Mushroom Residues to the Field on Soil Properties and Rice Growth at Different Stages" Sustainability 18, no. 3: 1266. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18031266

APA StyleSun, C., Song, K., Hu, R., Wang, F., Yin, X., Zhou, C., & Ni, G. (2026). Effects of Returning Mushroom Residues to the Field on Soil Properties and Rice Growth at Different Stages. Sustainability, 18(3), 1266. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18031266