Legume–Durum Wheat Cropping Systems for Sustainable Agriculture: A Life Cycle Assessment Systematic Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

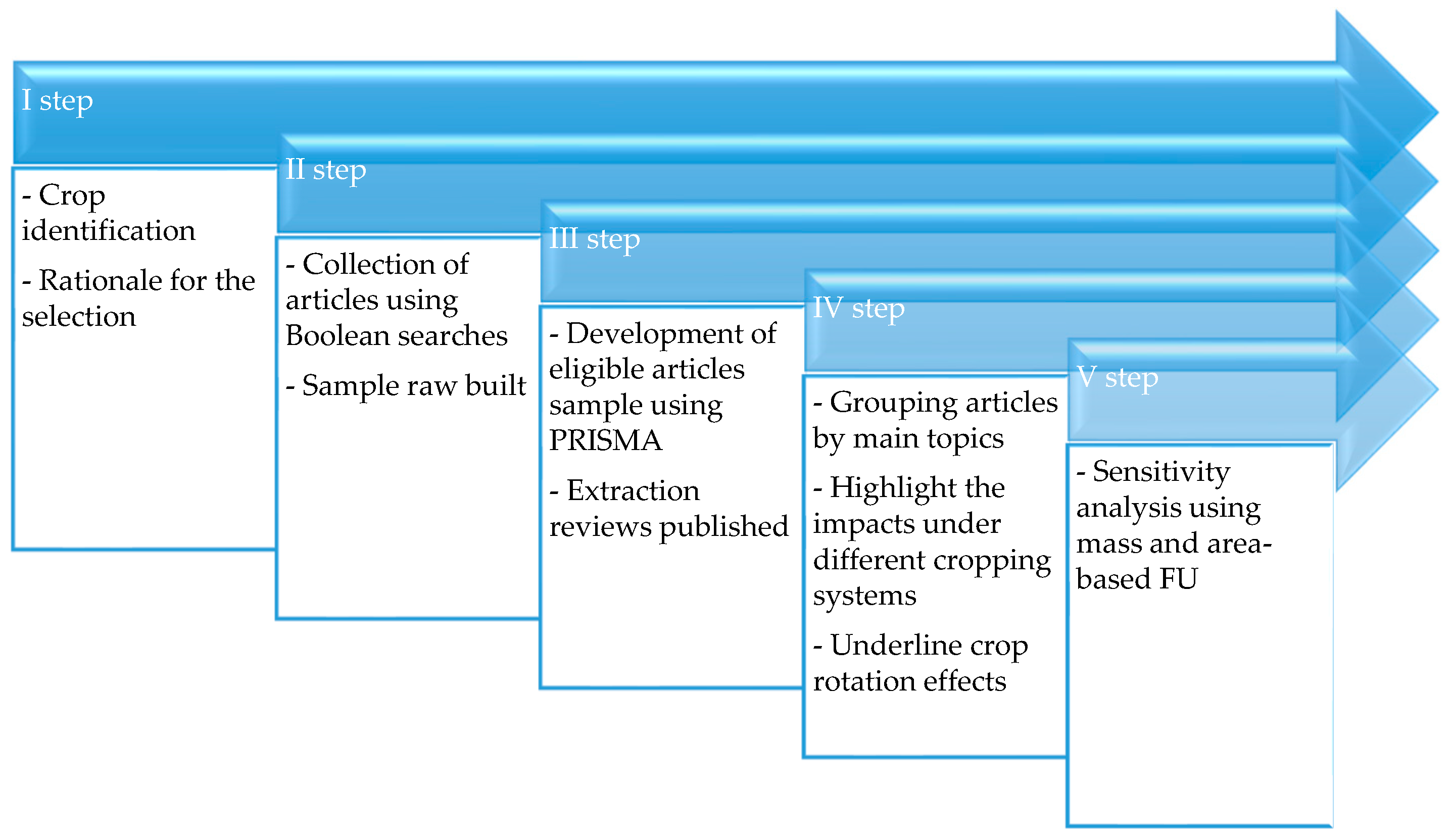

2. Research Methodology

2.1. Systematic Literature Review

- -

- life cycle assessment AND durum wheat AND conventional,

- -

- life cycle assessment AND durum wheat AND organic,

- -

- life cycle assessment AND agriculture AND durum wheat,

- -

- life cycle assessment AND raw material AND durum wheat,

- -

- life cycle assessment AND legumes AND conventional,

- -

- life cycle assessment AND legumes AND organic,

- -

- life cycle assessment AND legumes AND agriculture,

- -

- life cycle assessment and agri-food and organic agriculture,

- -

- life cycle assessment and raw materials and legumes,

- -

- life cycle assessment AND durum wheat AND legumes.

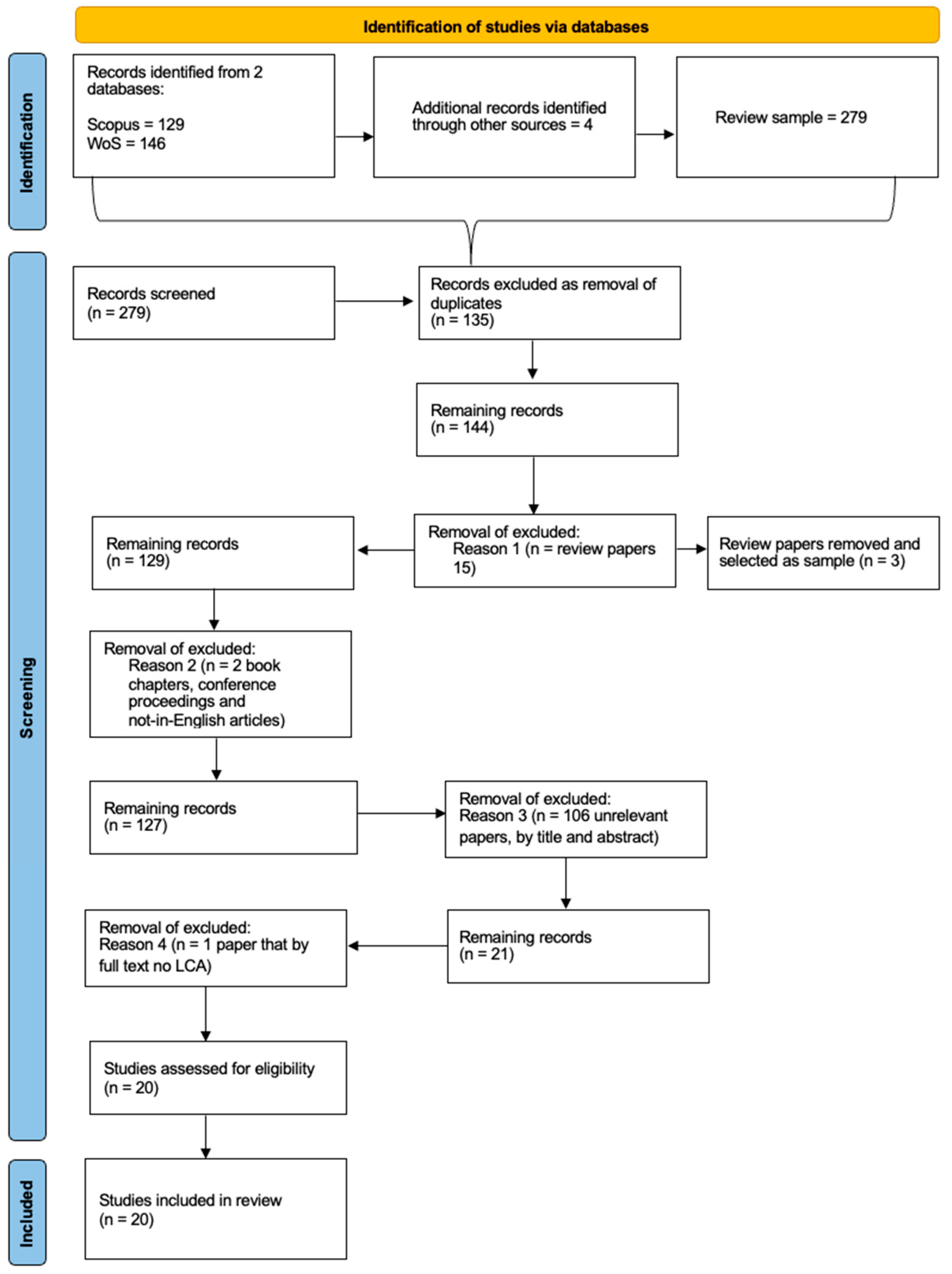

- The results of Zingale et al. [4] were found following the SLR methodology and the PRISMA model but only with regard to the DW sector. The same review has been adopted as a reference point for the topic of DW in this paper. Therefore, 14 articles, analyzed by Zingale et al. [4] (see Table S1 in Supplementary Materials), were excluded from the sample to avoid duplication of previously conducted analyses. Nevertheless, their review served as a starting point and reference for the present study.

- (a)

- From 2022 to 2025 for DW: the review by Zingale et al. [4] published in June 2022, that analyzed 14 articles (see Table S1 in Supplementary Materials), serves as a basis for DW sector analysis and covers the years of publication from 2006 to 2022;

- (b)

- From 2016 to 2025: the authors considered this range for legume and crop rotation.

- -

- Publication type: 17 (review articles or conference abstracts/papers).

- -

- Papers not published in English: 0.

- -

- Not relevant to durum wheat (DW) or DW-derived food products: 106.

- -

- No application of Life Cycle Assessment (LCA), insufficient methodological details, or incomplete inventory data: 1.

- -

- Duplicate records: 135.

2.2. Comparative and Sensitivity Analysis on Functional Unit Change

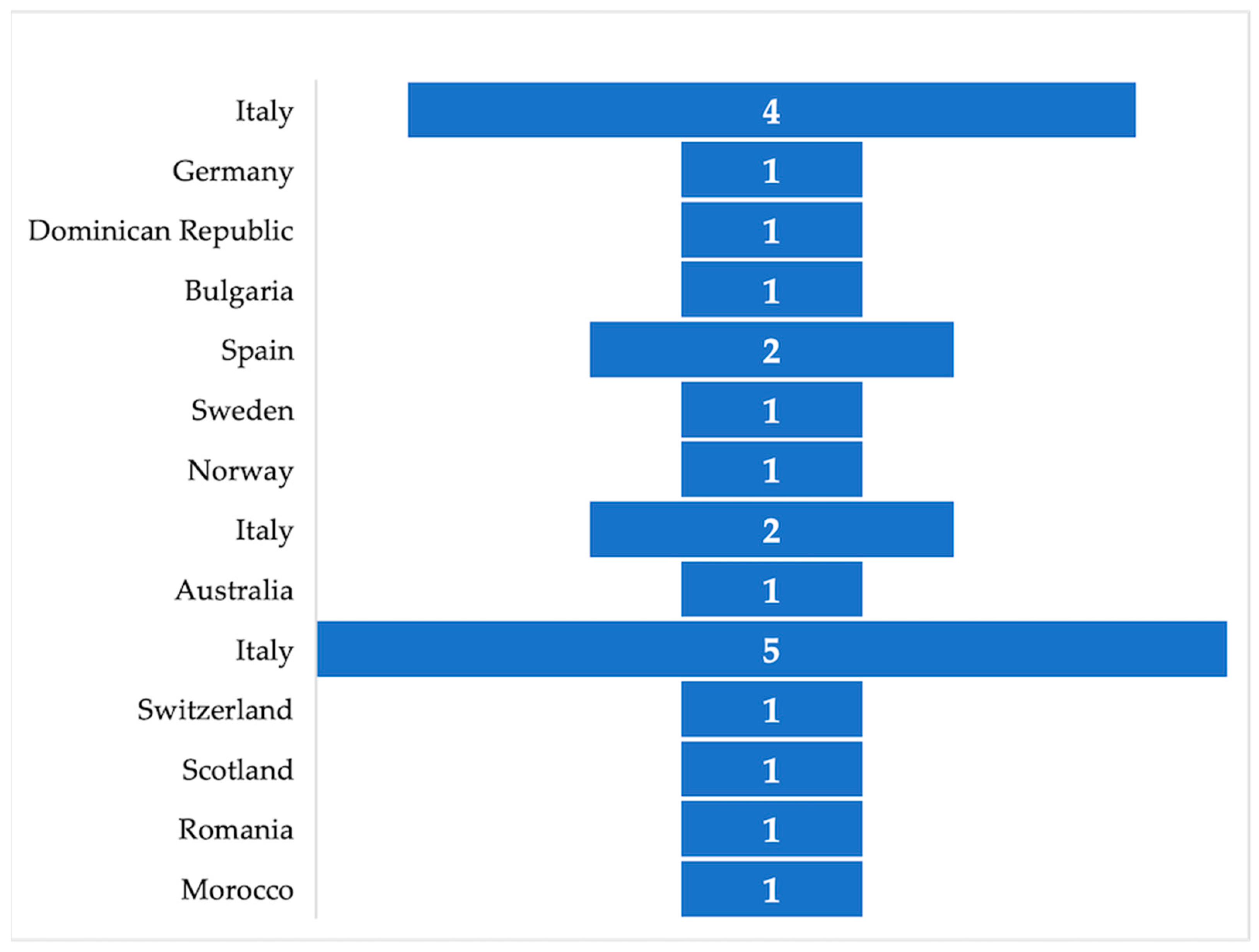

3. Review of the LCA Literature

- (1)

- LCA, durum wheat;

- (2)

- LCA, legumes;

- (3)

- LCA, crop rotation.

| Main Topics | Number of Articles | Authors |

|---|---|---|

| Life cycle assessment of DW | 4 | [30,31,32,33] |

| Life cycle assessment of legumes | 8 | [9,10,34,35,36,37,38,39] |

| Life cycle assessment of crop rotation | 8 | [40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47] |

3.1. LCAs of DW

| Authors | Main Findings |

|---|---|

| [30] |

|

| [32] |

|

| [33] |

|

| [31] |

|

3.2. LCA of Legumes

- The GHG values fell within the range of 0.18–0.44 kg CO2eq. in the conventional system;

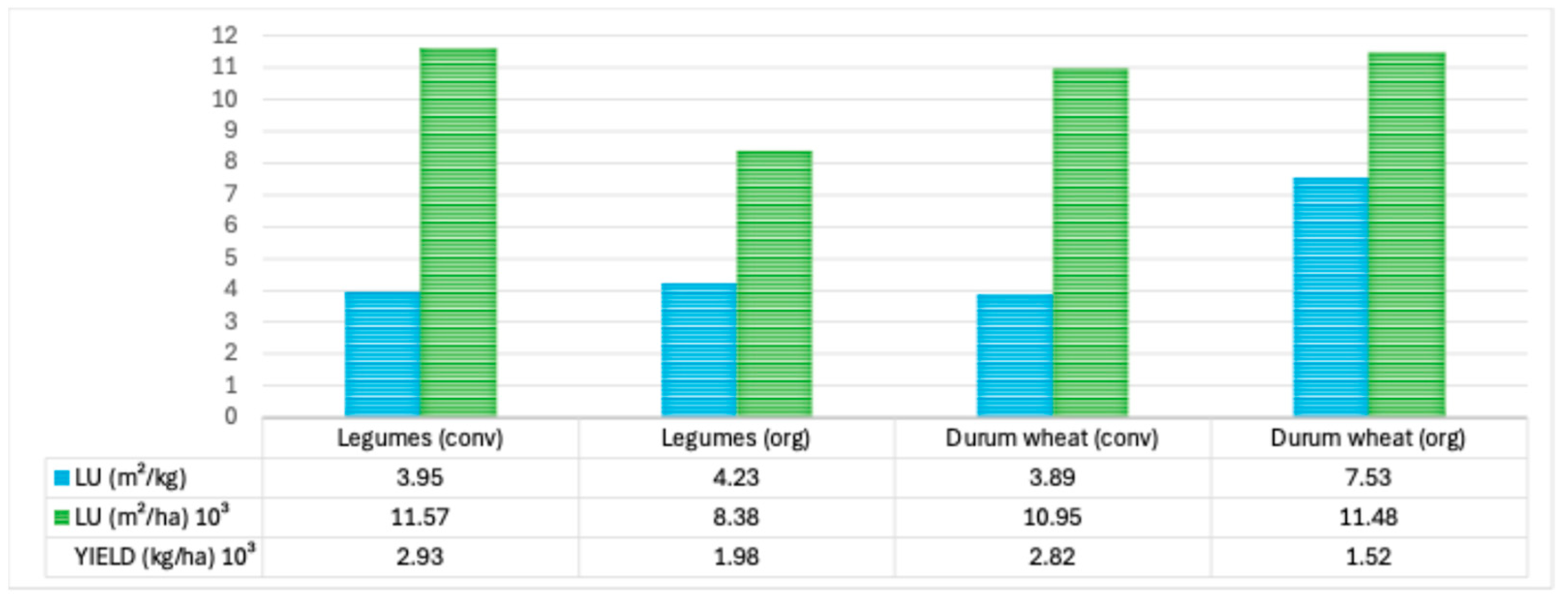

- The LU value for conventional cultivation was 3.1–5.9 m2;

- The GHG values fell within the range of 0.18–0.26 kg CO2eq. in the organic system;

- The LU for an organic cultivation system covered the range from 3.2 to 4.9 m2;

- No pesticides were used in organic agriculture, but 0.28–0.65 g of pesticides was used in conventional agriculture.

| Authors | Main Findings |

|---|---|

| [35] |

|

| [37] |

|

| [10] |

|

| [9] |

|

| [34] |

|

| [36] |

|

| [38] |

|

| [39] |

|

3.3. LCAs of Crop Rotation

- Peas generated 529 kg CO2eq./ha;

- DW produced 676 kg CO2eq./ha;

- Rapeseeds had the highest emissions at 841 kg CO2eq./ha.

- In Scotland, GWP decreased from 4.99 to 2.87 kg CO2eq.;

- In Italy, 9 out of 16 impact categories improved;

- In Romania, 14 out of 16 impact categories improved, with GWP decreasing from 6.81 to 4.78 kg CO2eq.

- Better nitrogen management;

- Optimized crop rotations;

- Reduced tillage;

- Adoption of renewable energy sources.

| Authors | Main Findings |

|---|---|

| [40] |

|

| [41] |

|

| [42] |

|

| [43] |

|

| [44] |

|

| [45] |

|

| [46] |

|

| [47] |

|

| Main Topic | Reference | Country | Methodology | FU | System Boundaries | Allocation Criteria | IAM | Impact Categories | Data Quality | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Data | Secondary Data | |||||||||

| LCA of DW | Verdi et al. (2022) [30] | Italy | LCA (SimaPro v.8.5) | 1 kg of DW | From cradle to grave | No allocation | CML vs 3,06 (2016) and CED vs. 1.11 (2018) | GWP, EP, HCT, TA, MET, FET, TET, POF, WC, LU, NCR, RRC | Checklist developed ad hoc for wheat cultivation analyzed | Ecoinvent v.3.4 database |

| Paolotti et al. (2023) [32] | Italy | LCA (SimaPro 9.0) | 1 kg of DW pasta | From cradle to gate | Economic allocation | IMPACT 2002+ | GWP | “Pastificio Mancini”, located in Marche region | Ecoinvent database | |

| di Cristofaro et al. (2024) [33] | Italy | LCA (SimaPro 9.4.0.2) | 1 Mg of DW | From cradle to gate | No allocation | Endpoint (H) 1.07 ReCiPe 2008 | GWP, HCT, ODL, POF, HCT, PM, TA, FET, TE, FE, ME, HnCT, LU, WC, HCT, IR, MRS, FRS, OFTE | Questionnaires to biodynamic and organic farms | Ecoinvent 3.3 | |

| 1 ha | ||||||||||

| 1 K € | ||||||||||

| Vinci et al. (2025) [31] | Italy | LCA (SimaPro 9.5) | 1 ha | From cradle to gate | Mass allocation | ILCD 2011+; V1.11 and ReCiPe 2016 | GWP, SOD, PM, HCT, POF, TA, HnCT, HCT, FE, TET, FET, MET, LU, WS, IR | Farmer company in Tuscany region with questionnaires and interviews | Ecoinvent v3.8 and World Food LCA Database (WFLDB) database | |

| LCA of legumes | Treu et al. (2017) [35] | Germany | LCA | 1 kg of legumes | From cradle to gate | No allocation | N.A. | GWP and LU | NVS II (German National Nutrition Survey) | No secondary data |

| Araujo et al. (2020) [37] | Dominican Republic | LCA | 1 t of legumes | From cradle to gate | No allocation | CML-IA | GWP, HCT, FE, TE, POF, TA, MET, FET, TET, ODL, AD | No primary data | Ecoinvent v. 3.2 database | |

| 1 ha | ||||||||||

| Saget et al. (2020) [10] | Bulgaria, Spain | LCA and nutritional LCA (OpenLCA 1.10.2) | 80 g of pasta | From cradle to grave | Economic allocation | PEF | TA, HCT, GWP, FE, MET, FET TET, LU, HnCT, ODL, WS, IR, FRS, MRS, PM | Bulgarian manufacturer of chickpea pasta Variva | Agrifootprint 3.0 and Ecoinvent 3.6 | |

| NDU | ||||||||||

| Tidåker et al. (2021) [9] | Sweden | LCA | 1 kg of dried legumes | Not defined | Mass allocation (yield) | IPCC | GWP, MET, EP, LU | No primary data | GaBi database, national agricultural statistics for 2012–2018, Ecoinvent 3.4 | |

| Svanes et al. (2022) [34] | Norway | LCA (SimaPro 9.3.0.) | 1 kg dried legume | From agricultural production to finished product | Economic allocation | ILCD 2011 Midpoint ReCiPe 2016 Endpoint ReCiPe 2016 Midpoint | GWP, TA, TET, FET, MET AD, TE, TE, ME, HCT, HnCT, LU, WC, FR | Farmers based on a questionnaire | Ecoinvent (v. 3.8), AgriBalyse (v. 1.3) and AgriFootprint (v. 5.0) | |

| 1kg legume protein | ||||||||||

| Boakye-Yiadom et al. (2023) [36] | Italy | LCA-EASETECH v.3.4. | 1 kg of legumes | From cradle to farm gate | No allocation | Environmental Footprint (EF) 3.0 midpoint life cycle impact assessment (LCIA) | TA, GWP, MET, FET, TET, ODL, WC, HCT | Agricultural joint-stock consortium in central Italy with 177 conventional and 10 organic peas fields | Ecoinvent database version 3.8 | |

| Pérez at al. (2024a) [29] | Spain | LCA (Simapro 9.5.0) | 1 kg of beans | From cradle to gate | No allocation | ReciPe midpoint V1.08 | GWP, SOD, TA, FET, MET, TE, FE, ME, HCT, HnCT, PM, LU, WC, IR, OFHH, OFTE, FPMF, FRS, MRS | Farmer surveys | Ecoivent database and OECD iLibrary | |

| Narote et al. (2025) [39] | Italy | LCA (SimaPro 9.4.0.2) | 100 kcal of energy | From cradle to gate | No allocation | CML-IA baseline (V3.09) | AD, GWP, ODL, HCT, FE, ME, TE, POF, TA, MET, TET, FET | Direct interviews with R&D team of the local company “Matarrese” | Ecoinvent 3.8 | |

| 100 g of a burger patty | ||||||||||

| LCA of crop rotation | Brock et al. (2016) [40] | Australia | LCA (SimaPro 8.0.4.30) | 1 ha | From cradle to farm gate | No allocation | IPCC | GWP | No primary data | Australian LCI database (Life Cycle Strategies Pty Ltd. 2013) and from the Swiss Ecoinvent Database (v3) |

| 1 t of legumes | ||||||||||

| Ali et al. (2017) [41] | Italy | LCA | 1 kg of grain | From cradle to gate | No allocation | IPCC Tier 1 | GWP | DW field experiments conducted in Policoro (Southern Italy) | No secondary data | |

| 1 ha | ||||||||||

| Prechsl et al. (2017) [42] | Switzerland | SALCA | 1 kg of legumes | By the borders of a field | No allocation | SALCA | GWP, MET, TET, ME | Farming System and Tillage Experiment (FAST) | Secondary data from Ecoinvent database (v2.2), SALCA Database | |

| 1 ha | ||||||||||

| 1 CHF | ||||||||||

| Falcone et al. (2019) [43] | Italy | LCA (SimaPro 8.1) | 1 ha | From cradle to farm gate | No allocation | ReCiPe Midpoint | ODL, HCT, GWP, TE, TA, ME, FE, MET, FET, WC | from experiment conducted in Foggia (Southern Italy) in collaboration with the Agricultural Research Council | No secondary data | |

| Costa et al. (2021) [44] | Scotland, Italy, Romania | Open LCA v1.9 | NDU | From cradle to farm gate | Economic allocation | PEF | GWP, TET, MET, LU, TE, FE, HCT, WC, ODL, POF, HnCT, IR, TA, FR | No primary data | Ecoinvent v.3.5 database | |

| CU | ||||||||||

| DP | ||||||||||

| Lago-Olveira et al. (2023) [45] | Italy | LCA | 1 ha | From cradle to farm gate | No allocation | ReCiPe Midpoint | GWP, SOD, TA, FET, MET, TE, FE, ME, FR | Questionnaire submitted to the main agricultural cooperatives in Puglia (Southern Italy) | Ecoinvent database 3.9v | |

| 1 € | ||||||||||

| Lago-Olveira et al. (2024) [46] | Morocco | Attributional LCA SimaPro v.9.3 Excel-MSO 365 | 1 ha | From cradle to farm gate | No allocation between products and co-products | ReCiPe 2016 V1.06 Hierarchist Midpoint method World (2010) | GWP, SOD, TA, FET, MET, TE, FE, ME, FR | Targeted interaction with farmers and supplemented by an agronomic report from the Moroccan Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development (2000) ICARDA field studies on the agrochemical inputs applied in Morocco | Ecoinvent v3.9 database | |

| 1 kg of grain | ||||||||||

| Zingale et al. (2024) [47] | Italy | LCA (Simapro 9.1.0.11) | 1 kg of grain | From cradle to farm gate | Economic allocation | ReCiPe 2016 v. 1.04 | LU, PM, GWP, HnCT | Interviews and questionnaires submitted to farmers | Ecoivent v. 3.6 database | |

| 1 ha | ||||||||||

| 1 € | ||||||||||

| Quality-corrected | ||||||||||

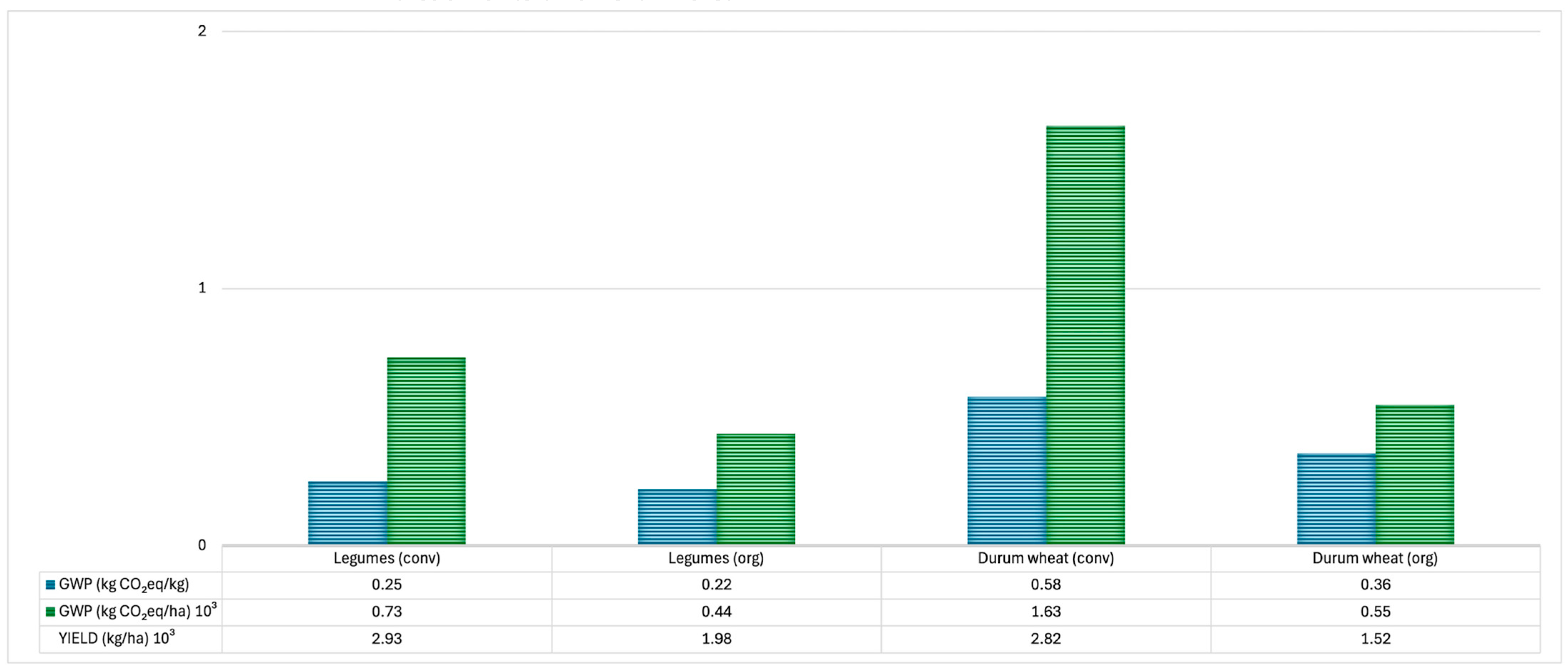

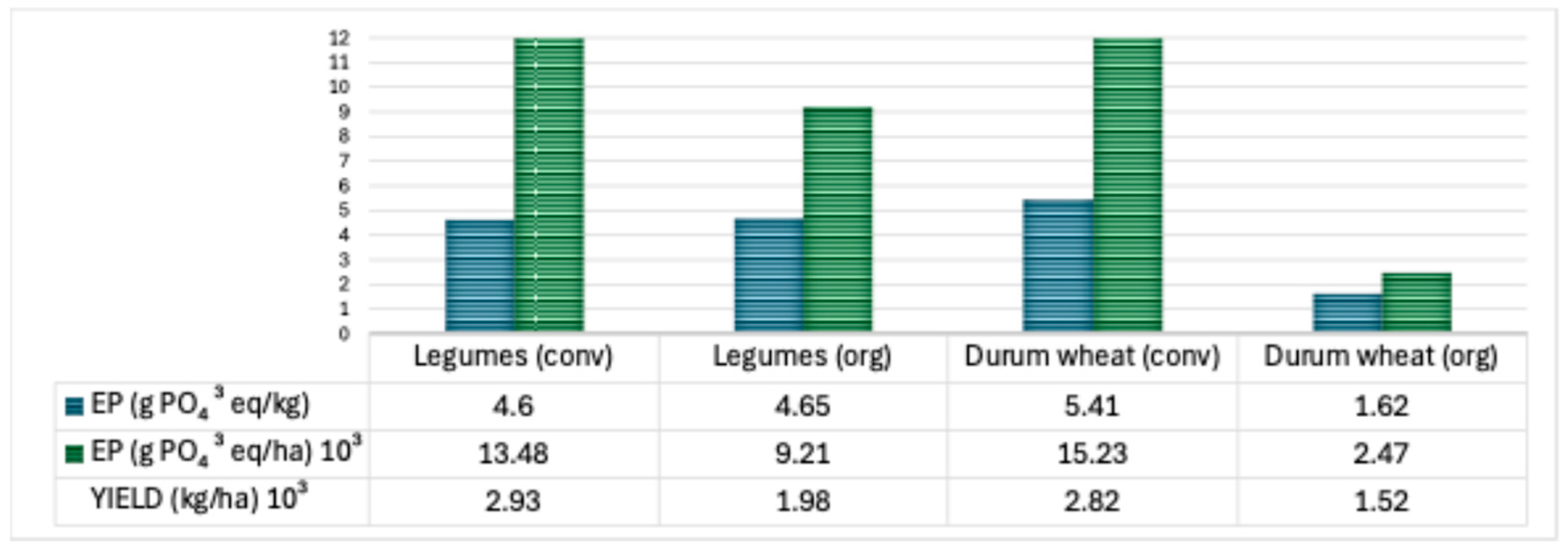

| Reference | Crop | Agricultural System | FU | GWP (kg CO2 Eq.) | TA (kg SO2 Eq.) | EP (kg PO4-3 Eq.) | CED (MJ) | TE (kg 1.4-DCB) | FE (kg 1.4-DCB) | ME (kg 1.4-DCB) | HCT (kg 1.4-DCB) | LU (m2 crop eq) | WC (m3/liter) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Verdi et al. (2022) [30] | DW | Conventional | 1 kg of DW | 0.580 | 3.90 | 5.41 × 10−3 | N.A. | 5.80 × 10−4 | 5.00 × 10−2 | N.A. | 1.10 × 10−1 | 3.89 | 6.06 × 10−1 liters |

| DW | Organic | 1 kg of DW | 0.360 | 3.08 | 1.62 × 10−3 | 2.79 × 10−4 | 1.00 × 10−2 | 4.00 × 10−2 | 7.53 | 5.26 × 10−1 liters | |||

| Paolotti et al. (2023) [32] | DW | Conventional | 1 kg of DW of pasta * | 1.042 | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. |

| Vinci et al. (2025) [31] | DW | Organic | 1 ha | −1.42 × 102 | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. |

| Treu et al. (2017) [35] | Legumes | Conventional | 1 kg of legumes | 0.32 | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | 0.36 | N.A. |

| Organic | 1 kg of legumes | 0.35 | 0.40 | ||||||||||

| Araujo et al. (2020) [37] | Legumes | Conventional | 1 ha of common bean 1 ha of pigeon pea | 1.44 × 103 7.15 × 102 | 7.13 3.55 | 2.28 1.14 | 2.09 × 104 1.04 × 104 | 1.80 0.893 | 1.98 × 102 9.83 × 101 | N.A. | 2.70 × 102 1.34 × 102 | N.A. | N.A. |

| 1 t of common bean 1 t of pigeon pea | 1.38 × 103 1.46 × 103 | 6.61 7.01 | 2.08E 2.20 | 2.08 × 104 2.20 × 104 | 1.70 × 100 1.80 × 100 | 2.25 × 102 2.38 × 102 | 2.65 × 102 2.80 × 102 | ||||||

| Saget et al. (2020) [10] | DW | Conventional | 80 g of pasta * | DW80%: 0.05 | N.A. | N.A. | DW80%: 0.316 | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | DW80%: 0.031 |

| Chickpea | Conventional | Chickpea: Bulgaria 0.082 | Chickpea: Bulgaria 0.475 | Chickpea: Bulgaria 0.0518 | |||||||||

| Tidåker et al. (2021) [9] | Legumes | Conventional | 1 kg of legumes | Faba bean: 0.18 | N.A. | Faba bean: 2.5 | Faba bean: 1.8 | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | Faba bean: 3.1 | N.A. |

| Yellow pea: 0.18 | Yellow pea: 3.8 | Yellow pea: 1.7 | Yellow pea: 3.2 | ||||||||||

| Gray pea: 0.20 | Gray pea: 4.3 | Gray pea: 4.3 | Gray pea: 3.6 | ||||||||||

| Common bean: 0.44 | Common bean: 7.8 | Common bean: 1.9 | Common bean: 5.9 | ||||||||||

| Organic | 1 kg of legumes | Faba bean: 0.20 | N.A. | Faba bean: 3.3 | Faba bean: 2.0 | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | Faba bean: 4.1 | N.A. | ||

| Yellow pea: 0.24 | Yellow pea: 5.7 | Yellow pea: 2.2 | Yellow pea: 4.9 | ||||||||||

| Gray pea: 0.18 | Gray pea: 3.8 | Gray pea: 1.6 | Gray pea: 3.2 | ||||||||||

| Lentils: 0.26 | Lentils: 5.8 | Lentils: 2.3 | Lentils: 4.7 | ||||||||||

| Svanes et al. (2022) [34] | Legumes | N.A. | 1 kg of dried legumes | Pea 0.57 | Pea 0.0027 | Pea 0.005 | Pea 4.8 | Pea 0.77 | Pea 0.02 | Pea 0.02 | Pea 0.03 | Pea 2.9 | Pea 0.006, faba beans 0.003 |

| Faba peans 0.62 | Faba beans 0.0022 | Faba beans 0.005 | Faba beans 5.2 | Faba beans 0.7 | Faba beans 0.02 | Faba beans 0.02 | Faba beans 0.03 | Faba beans 3 | |||||

| Boakye-Yiadom et al. (2023) [36] | Legumes (peas) | Conventional | 1 kg of legumes | 0.98 | N.A. | N.A. | 3.44 | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | 0.26 |

| Organic | 1 kg of legumes | 0.88 | 2.70 | 0.22 | |||||||||

| Pérez et al. (2024b) [38] | Legumes (bean) | Organic | 1 kg of legumes | 1.2 | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. |

| Narote et al. (2025) [39] | Black chickpeas | Conventional | 100 g of a burger patty * | 4.77 × 10−2 | 4.52 × 10−4 | 2.67 × 10−4 | 2.91 × 10−1 | 1.43 × 10−3 | 1.55 × 10−2 | 2.11 × 10−1 | 2.39 × 10−2 | N.A. | N.A. |

| Brock et al. (2016) [40] | DW–DW | Not defined | 1 ha | 676 | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. |

| DW–field peas | 1 ha | 586 | |||||||||||

| Field peas | 1 ha | 529 | |||||||||||

| Ali et al. (2017) [41] | DW–DW | Conventional | 1 ha | 1614.54 | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. |

| DW–faba beans | 1 ha | 1510.14 | |||||||||||

| DW–DW | 1 kg of grain | 0.322 | |||||||||||

| DW–faba beans | 1 kg of grain | 0.395 | |||||||||||

| Prechsl et al. (2017) [42] | Cover crop, wheat, cover crop, maize, faba beans, wheat, and two years of grass–clover ley | Conventional | 1 ha | 2507.6 | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | 797.4 | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. |

| Organic | 1 ha | 1366.4 | 142.4 | ||||||||||

| Falcone et al. (2019) [43] | DW–DW | Conventional | 1 ha | 4.54 × 103 | 7.94 × 101 | 2.80 × 101 | N.A. | 3.53 × 100 | 2.02 × 101 | 3.08 × 101 | 1.23 × 103 | 1.48 × 100 | 6.51 × 101 |

| DW–vetch | Conventional | 1 ha | 3.44 × 103 | 5.58 × 101 | 2.49 × 101 | 3.03 × 100 | 1.30 × 101 | 3.06 × 101 | 1.06 × 103 | 1.07 × 100 | 8.55 × 101 | ||

| Lago-Olveira et al. (2023) [45] | DW–DW–DW | Conventional | 1 ha | 5370 | 81.43 | N.A. | N.A. | 23,410 | 353.92 | 240.26 | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. |

| Chickpea–DW–DW | Conventional | 1 ha | 4420 | 82.90 | 21,010 | 283.92 | 223.15 | ||||||

| Lago-Olveira et al. (2024) [46] | In 3 crop rotations: R1: chickpea–wheat R2: lentil–wheat R3: wheat–wheat | Conventional | Land management FU (1 ha/ year) | R1: 1.41 × 103 R2: 1.42 × 103 R3: 2.02 × 103 | R1: 12.96 R2: 12.92 R3: 17.52 | N.A. | N.A. | R1: 3.78 × 103 R2: 3.67 × 103 R3: 4.94 × 103 | R1: 46.16 R2: 46.03 R3: 53.84 | R1: 50.97 R2: 50.39 R3: 70.02 | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. |

| Productive FU (1 kg of harvested wheat) | R1: 1.05 R2: 0.95 R3: 1.30 | R1: 9.60 × 10−3 R2: 8.62 × 10−3 R3: 11.30 × 10−3 | N.A. | N.A. | R1: 2.80 R2: 2.45 R3: 3.19 | R1:34.19 × 10−3 R2: 30.68 × 10−3 R3: 34.73 × 10−3 | R1: 37.75 × 10−3 R2: 33.59 × 10−3 R3: 45.19 × 10−3 | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | |||

| Zingale et al. (2024) [47] | Faba beans–DW | Organic | 1 kg | 0.33 | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | 0.371 | 5.87 | N.A. |

| Bare fallow–DW | Conventional | 0.55 | 0.255 | 5.11 | |||||||||

| Faba beans–DW | Organic | 1 ha | 7.80 × 1020 | 8.77 × 102 | 1.39 × 104 | ||||||||

| Bare fallow–DW | Conventional | 2.26 × 103 | 1.12 × 103 | 2.08 × 104 |

3.4. Final Remarks and Research Gaps

3.5. Comparative and Sensitivity Analysis on Functional Unit

4. Limitations and Practical Implications

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AD | Abiotic Depletion |

| CED | Cumulative Energy Demand |

| CF | Carbon footprint |

| CML-IA | CML database with characterization factors for Life Cycle Impact Assessment (LCIA) |

| CU | Cereal Unit |

| DP | Total Digestive Protein |

| DW | Durum wheat |

| EP | Eutrophication potential |

| eq. | Equivalent |

| FAST | Farming System and Tillage Experiment |

| FE | Freshwater ecotoxicity |

| FET | Freshwater Eutrophication |

| FPMF | Fine particulate matter formation |

| FR | Fossil Resources |

| FRS | Fossil resource scarcity |

| FU | Functional unit |

| GHG | Greenhouse gases |

| GWP | Global Warming Potential |

| HA | Hectare |

| HCT | Human Carcinogenic Toxicity |

| HnCT | Human non-carcinogenic toxicity |

| IAM | Impact assessment method |

| ILCD 2011 | International reference life cycle data system |

| ILUC | Indicator of indirect land use change |

| IPCC | Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change |

| IR | Ionizing radiation |

| LCA | Life Cycle Assessment |

| LU | Land use |

| ME | Marine Ecotoxicity |

| MET | Marine Eutrophication |

| MRS | Mineral resource scarcity |

| N.A. | Not Available |

| NRC | Non-Renewable Energy Resources Consumption |

| NDU | Nutrient Density Unit |

| ODL | Ozone Depletion Layer |

| OFHH | Ozone formation human health |

| OFTE | Ozone formation terrestrial ecosystems |

| PAS | Publicly Available Specification |

| Global Potential Species Loss | |

| PEF | Product Environmental Footprint |

| POF | Photochemical Oxidant Formation |

| PM | Particulate Matter |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| RRC | Renewable Energy Resources Consumption |

| SALCA | Swiss Agriculture Life Cycle Assessment |

| SDGs | Sustainable Development Goals |

| SLR | Systematic literature review |

| SOM | Soil Organic Matter |

| SOD | Stratospheric ozone depletion |

| TA | Terrestrial Acidification |

| TDP | Total Digestible Protein |

| TE | Terrestrial Ecotoxicity |

| TET | Terrestrial Eutrophication |

| WC | Water Consumption |

| WS | Water scarcity |

References

- UN. World Population Prospects 2024—Summary of Results. 2024. Available online: https://population.un.org/wpp/assets/Files/WPP2024_Key-Messages.pdf (accessed on 4 September 2025).

- Crovella, T.; Paiano, A.; Lagioia, G. A meso-level water use assessment in the Mediterranean agriculture. Multiple applications of water footprint for some traditional crops. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 330, 129886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista. Agriculture Emissions Worldwide—Statistics & Facts. 2024. Available online: https://www.statista.com/topics/10348/agriculture-emissions-worldwide/#topicOverview (accessed on 30 April 2024).

- Zingale, S.; Guarnaccia, P.; Matarazzo, A.; Lagioia, G.; Ingrao, C. A systematic literature review of life cycle assessments in the durum wheat sector. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 844, 157230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IGC. International Grain Council—Grain Market Report. 2025. Available online: https://www.igc.int/en/gmr_summary.aspx (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- USDA. Foreign Agricultural Services U.S. Department of Agriculture—Perform a Custom Query. 2025. Available online: https://apps.fas.usda.gov/psdonline/app/index.html#/app/home (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Badagliacca, G.; Messina, G.; Presti, E.L.; Preiti, G.; Di Fazio, S.; Monti, M.; Modica, G.; Praticò, S. Durum Wheat (Triticum durum Desf.) Grain Yield and Protein Estimation by Multispectral UAV Monitoring and Machine Learning Under Mediterranean Conditions. AgriEngineering 2025, 7, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Report Linker Research. Forecast: Pulses Production in the World. 2025. Available online: https://www.reportlinker.com/dataset/c42ec97aa777d224e8d5c5eb64891df6f1dbdf90 (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Tidåker, P.; Karlsson Potter, H.; Carlsson, G.; Röös, E. Towards sustainable consumption of legumes: How origin, processing and transport affect the environmental impact of pulses. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 27, 496–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saget, S.; Costa, M.; Barilli, E.; Wilton de Vasconcelos, M.; Santos, C.S.; Styles, D.; Williams, M. Substituting wheat with chickpea flour in pasta production delivers more nutrition at a lower environmental cost. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2020, 24, 26–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Shen, A.; Zhang, T.; Jiang, L.; El-Seedi, H.; Zhang, G.; Sui, X. Legumes as an alternative protein source in plant-based foods: Applications, challenges, and strategies. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2024, 9, 100876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SDGs—The 17 Goals. 2024. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 15 April 2024).

- Denora, M.; Mehmeti, A.; Casiello, D.; Casiero, P.; Melon, D.M.; Cardone, L.; Mazzei, P.; Ronga, D.; De Falco, E.; Perniola, M. Durum wheat-vetch intercropping in Mediterranean agroecological systems: Effects on yield, nitrogen balance, and farm profitability. Ital. J. Agron. 2025, 20, 100045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, S.C.; Venkatesh, K.; Meena, R.P.; Chander, S.; Singh, G.P. Sustainable intensification of maize and wheat cropping system through pulse intercropping. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 18805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huss, C.P.; Holmes, K.D.; Blubaugh, C.K. Benefits and risks of intercropping for crop resilience and pest management. J. Econ. Entomol. 2022, 115, 1350–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SETAC. Society of Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry—Guidelines for Life-Cycle Assessment: A “Code of Practice”. 1933. Available online: https://www.setac.org/resource/guidelines-lca-code-practice-1993.html (accessed on 15 April 2024).

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 371, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.; Green, S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Review on Interventions; The Cochrane Collaboration; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011; Available online: https://training.cochrane.org/handbook#how-to-access (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Nguyen, T.T.B.; Li, D. A systematic literature review of food, safety management system implementation in global supply chains. Br. Food J. 2021, 124, 3014–3031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denyer, D.; Tranfield, D. Producing a systematic review. In The Sage Handbook of Organizational Research Methods; Buchanan, D., Bryman, A., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 2009; pp. 665–671. [Google Scholar]

- Ferdous, J.; Bensebaa, F.; Hewage, K.; Bhowmik, P.; Pelletier, N. Use of process simulation to obtain life cycle inventory data for LCA: A systematic review. Clean. Environ. Syst. 2024, 14, 100215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.Y.; Natter, M.; Spann, M. Pay What You Want: A new participative pricing mechanism. J. Mark. 2009, 73, 44–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paschou, T.; Rapaccini, M.; Adrodegari, F.; Saccani, N. Digital servitization in manufacturing: A systematic literature review and research agenda. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2020, 89, 278–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güzel, O.; Vizuete-Luciano, E.; Merigó-Lindahl, J.M. A systematic literature review of the Pay-What-You-Want pricing under PRISMA protocol. Eur. Res. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2025, 31, 100266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedoussac, L.; Journet, E.P.; Hauggaard-Nielsen, H.; Naudin, C.; Corre-Hellou, G.; Jensen, E.S.; Prieur, L.; Justes, E. Ecological principles underlying the increase of productivity achieved by cereal-grain legume intercrops in organic farming. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2015, 35, 911–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, M.P.; Chadwick, D.; Saget, S.; Rees, R.M.; Williams, M.; Styles, D. Representing crop rotations in life cycle assessment: A review of legume LCA studies. Intern. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2020, 25, 1942–1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiting, P.; Savović, J.; Higgins, J.P.T.; Caldwell, D.M.; Reeves, B.C.; Shea, B.; Davies, P.; Kleijnen, J.; Churchill, R.; the ROBIS Group. ROBIS: A new tool to assess risk of bias in systematic reviews was developed. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2016, 69, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salou, T.; Le Mouël, C.; van der Werf, H.M.G. Environmental impacts of dairy system intensification: The functional unit matters! J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 140, 445–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, R.; Argüelles, F.; Laca, A.; Laca, A. Evidencing the importance of the functional unit in comparative life cycle assessment of organic berry crops. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 22055–22072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdi, L.; Marta, A.D.; Falconi, F.; Orlandini, S.; Mancini, M. Comparison between organic and conventional farming systems using Life Cycle Assessment (LCA): A case study with an ancient wheat variety. Eur. J. Agron. 2022, 141, 126638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinci, G.; Prencipe, S.A.; Ruggeri, M.; Gobbi, L.; Arcese, G. Sustainability performance evaluation in the organic durum wheat production: Evidence from Italy. Intern. J. Life Cycle Assess 2025, 30, 1115–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paolotti, L.; Corridoni, F.; Rocchi, L.; Boggia, A. Evaluating Environmental Sustainability of Pasta Production through the Method LCA. Environ. Clim. Technol. 2023, 27, 593–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- di Cristofaro, M.; Marino, S.; Lima, G.; Mastronardi, L. Evaluating the impacts of different durum wheat farming system through Life Cycle Assessment. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 436, 140696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svanes, E.; Waalen, W.; Uhlen, A.K. Environmental impacts of field peas and faba beans grown in Norway and derived products, compared to other food protein sources. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2022, 33, 756–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treu, H.; Nordborg, M.; Cederberg, C.; Hoffmann, H.; Berndes, G. Carbon footprints and land use of conventional and organic diets in Germany. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 61, 127–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boakye-Yiadom, K.A.; Ilari, A.; Bisinella, V.; Foppa Pedretti, E.; Duca, D. Environmental Impact Assessment of Frozen Peas Production from Conventional and Organic Farming in Italy. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araujo, J.; Urbano, B.; Gonzalez-Andres, F. Comparative environmental life cycle and agronomic performance assessments of nitrogen fixing rhizobia and mineral nitrogen fertiliser applications for pulses in the Caribbean region. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 267, 122065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, R.; Fernández, C.; Laca, A.; Laca, A. Evaluation of environmental impacts in legume crops: A case study of PGI white bean production in southern Europe. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narote, A.D.; Casson, A.; Giovenzana, V.; Pampuri, A.; Tugnolo, A.; Beghi, R.; Guidetti, R. Integrating environmental, nutritional, and economic dimensions in Food choices: A case study on legume vs. meat-based burger patties. J. Agric. Food Res. 2025, 21, 101820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brock, P.M.; Muir, S.; Herridge, D.F.; Simmons, A. Cradle-to-farmgate greenhouse gas emissions for 2-year wheat monoculture and break crop-wheat sequences in south-eastern Australia. Crop Pasture Sci. 2016, 67, 812–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.A.; Tedone, L.; Verdini, L.; De Mastro, G. Effect of different crop management systems on rainfed durum wheat greenhouse gas emissions and carbon footprint under Mediterranean conditions. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 140, 608–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prechsl, U.E.; Wittwer, R.; van der Heijden, M.G.A.; Lüscher, G.; Jeanneret, P.; Nemecek, T. Assessing the environmental impacts of cropping systems and cover crops: Life cycle assessment of FAST, a long-term arable farming field experiment. Agric. Syst. 2017, 157, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcone, G.; Stilitano, T.; Montemurro, F.; Gulisano, G.; Strano, A. Environmental and economic assessment of sustainability in mediterranean wheat production. Agron. Res. 2019, 17, 60–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, M.P.; Reckling, M.; Chadwick, D.; Williams, M.; Styles, D. Legume Modified Rotations Deliver Nutrition with Lower Environmental Impact. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2021, 5, 656005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lago-Olveira, S.; Rebolledo-Leiva, R.; Garofalo, P.; Moreira, M.T.; González-García, S. Environmental and economic benefits of wheat and chickpea crop rotation in the Mediterranean region of Apulia (Italy). Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 896, 165124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lago-Olveira, S.; Ouhemi, H.; Idrissi, O.; Moreira, M.T.; González-García, S. Promoting more sustainable agriculture in the Moroccon drylands by shifting from conventional wheat monoculture to a rotation with chickpea and lentils. Clean. Environ. Syst. 2024, 12, 100169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zingale, S.; Ingrao, C.; Reguant-Closa, A.; Guarnaccia, P.; Nemecek, T. A multifunctional life cycle assessment of durum wheat cropping systems. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2024, 44, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, N.; Reifen, R. The potential of legume-derived proteins in the food industry. Grain Oil Sci. Technol. 2022, 5, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loges, R.; Wachendorf, L.; Taube, E. Scaling up of milk production data from field plot to regional farm level. In Proceedings of the 2nd European Invitational Expert Seminar on Life Cycle Assessments of Food Products 2000, The Hague, The Netherlands, 25–26 January 1999; Agricultural Economics Research Institute (LEI-DLO): The Hague, Netherlands, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Foerster, F.C.; Döring, J.; Koch, M.; Kauer, R.; Stoll, M.; Wohlfahrt, Y.; Wagner, M. Comparative life cycle assessment of integrated and organic viticulture based on a long-term field trial in Germany. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2024, 52, 487–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crovella, T.; Paiano, A.; Lagioia, G.; Cilardi, A.M.; Trotta, L. Modelling Digital Circular Economy framework in the Agricultural Sector. An Application in Southern Italy. Eng. Proc. 2021, 9, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandekar, P.A.; Putman, B.; Thoma, G.; Matlock, M. Cradle-to-grave life cycle assessment of production and consumption of pulses in the United States. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 302, 114062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, O.M.; Cohen, A.L.; Rieser, C.J.; Davis, A.G.; Taylor, J.M.; Adesanya, A.W.; Jones, M.S.; Meier, A.R.; Reganold, J.P.; Orpet, R.J.; et al. Organic farming provides reliable environmental benefits but increases variability in crop yields: A global meta-analysis. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2019, 3, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 14040:2006; 14040-Environmental Management e Life Cycle Assessment and Principles and Framework. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006.

- Rusyn, I.; Malovanyy, M.; Tymchuk, I. Serhiy Synelnikov Effect of mineral fertilizer encapsulated with zeolite and polyethylene terephthalate on the soil microbiota, pH and plant germination. Ecol. Quest. 2020, 32, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrencia, D.; Wong, S.K.; Low, D.Y.S.; Goh, B.H.; Goh, J.K.; Ruktanonchai, U.R.; Soottitantawat, A.; Lee, L.H.; Tang, S.Y. Controlled Release Fertilizers: A Review on Coating Materials and Mechanism of Release. Plants 2021, 10, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regulation (EU) 2021/2115 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 2 December 2021 Establishing Rules on Support for Strategic Plans to be Drawn Up by Member States Under the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP Strategic Plans) and Financed by the European Agricultural Guarantee Fund (EAGF) and by the European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development (EAFRD) and Repealing Regulations (EU) No 1305/2013 and (EU) No 1307/2013. 2021. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2021/2115/oj/eng (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Atik, M.; Isikly, R.C.; Ortacesme, V.; Yildirim, E. Definition of landscape character areas and types in Side region, Antalya-Turkey with regard to land use planning. Land Use Policy 2015, 44, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Keywords 1 | Boolean Operator | Keywords 2 | Boolean Operator | Keywords 3 | Boolean Operator | Keywords 4 | Covered Period | Number of Articles Found on Scopus | Number of Articles Found on WoS | Additional Records Identified Through Other Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Life Cycle Assessment | AND | durum wheat | AND | conventional | - | - | 2022–2025 | 8 | 8 | 4 |

| durum wheat | organic | - | 2022–2025 | 10 | 15 | |||||

| agriculture | durum wheat | - | 2022–2025 | 19 | 32 | |||||

| raw material | durum wheat | - | 2022–2025 | 1 | 0 | |||||

| legumes | AND | conventional | AND | - | 2016–2026 | 21 | 17 | |||

| legumes | organic | - | 2016–2026 | 18 | 20 | |||||

| legumes | agriculture | - | 2016–2026 | 42 | 43 | |||||

| agri-food | organic agriculture | - | 2016–2026 | 5 | 5 | |||||

| raw material | legumes | - | 2016–2026 | 4 | 5 | |||||

| durum wheat | AND | legumes | AND | crop rotation | 2016–2026 | 1 | 1 | |||

| TOTAL | 129 | 146 | 4 |

| Authors | Title | Journal | Keywords | Topics Analyzed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [25] | Ecological principles underlying the increase of productivity achieved by cereal-grain legume intercrops in organic farming. A review | Agronomy for Sustainable Development | Environmental resource use Eco-functional intensification Cereal–grain legume intercrop Protein concentration Weed Yield |

|

| [26] | Representing crop rotations in life cycle assessment: a review of legume LCA studies | International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment | Legumes Crop rotations Functional units Allocation Multifunctionality Nitrogen cycling |

|

| [4] | A systematic literature review of Life Cycle Assessment in the durum wheat sector | Science of the Total Environment | Agriculture Food production Durum wheat cultivation Life Cycle Assessment Climate change Environmental impact |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Minafra, N.; Paiano, A.; Lagioia, G.; Crovella, T. Legume–Durum Wheat Cropping Systems for Sustainable Agriculture: A Life Cycle Assessment Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2026, 18, 1206. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18031206

Minafra N, Paiano A, Lagioia G, Crovella T. Legume–Durum Wheat Cropping Systems for Sustainable Agriculture: A Life Cycle Assessment Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability. 2026; 18(3):1206. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18031206

Chicago/Turabian StyleMinafra, Nicola, Annarita Paiano, Giovanni Lagioia, and Tiziana Crovella. 2026. "Legume–Durum Wheat Cropping Systems for Sustainable Agriculture: A Life Cycle Assessment Systematic Literature Review" Sustainability 18, no. 3: 1206. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18031206

APA StyleMinafra, N., Paiano, A., Lagioia, G., & Crovella, T. (2026). Legume–Durum Wheat Cropping Systems for Sustainable Agriculture: A Life Cycle Assessment Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability, 18(3), 1206. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18031206